COM MON I NG SOHO SQUARE

BOOK 1

BOOK 2

BOOK 3

BOOK 4

BOOK 5

SHARI NG IS NOT CARING SATURATED SOHO SQUARE OBSERVI NG TH E URBAN COM MONS

CONSTRUCTI NG OBSERVATIONS TRANSLATIONS AN D REFLECTIONS

Marnie Slotover MA Architecture

RCA ADS 2022/2023

BOOK 1

BOOK 2

BOOK 3

BOOK 4

BOOK 5

SHARI NG IS NOT CARING SATURATED SOHO SQUARE OBSERVI NG TH E URBAN COM MONS

CONSTRUCTI NG OBSERVATIONS TRANSLATIONS AN D REFLECTIONS

Marnie Slotover MA Architecture

RCA ADS 2022/2023

This book charts the rise of the sharing economy and argues that the capitalisation of sharing has led to a fall in public caring.

The commons have been capitalised through the introduction of the sharing economy. The sharing economy is a socio-economic system that has been growing in popularity since 2013 and is built around the sharing of resources; it includes household name companies such as airBnB, WeWork, Lime and ZipCar.

The image of the fallen e-bike has become a symbol of London under late capitalism, but this is just the tip of the iceberg. This book unpacks the conditions that have led to this lack of care and alienation items and spaces in common use, and presents novel ways to intervene.

The sharing economy is a socio-economic system built around the sharing of resources that has emerged on the back of radical changes in consumer habits (Le Jeune, 2016). Resources with excess capacity are shared by businesses or individuals for a fee through the use of online platform, differing to the hierarchical model of buying and selling.

Sharing economy businesses share 5 main characteristics: they employ casual labour, are market based, the lines between personal and professional are often blurred, they employ crowd based networks and involve high impact capital. In the UK, the top four sectors by GDP are ride sharing, accommodation, workspace and vehicle sharing. Many of the companies within these sectors have become household names, such as Uber and AirBnB. The sharing economy has been growing exponentially and this growth is projected to continue: global GDP was only 15bn in 2013 and is set to rise to 335bn in 2025.

The sharing economy has been written about from varying perspectives, in ‘What’s Mine is Yours’ Botsman and Rogers (2011) argue for the potential of collaborative consumption as an alternative to consumerism, whilst Sundararajan (2016) warns of the socio-economic impacts of sharing platforms on the workforce.

By partaking businesses, the sharing economy is promoted as an environmentally friendly way to ‘have it all’ without the burden of ownership. The promotional material is fun and light-hearted, with the use of bright colours and simple, catchy slogans, appealing to younger generations. However, this marketing is dubious when interrogating the circumstances that led to the rise of the sharing economy. Companies are wrapping commodity exchanges in a vocabulary of sharing, to promote an alternative worldview (Hern, 2015).

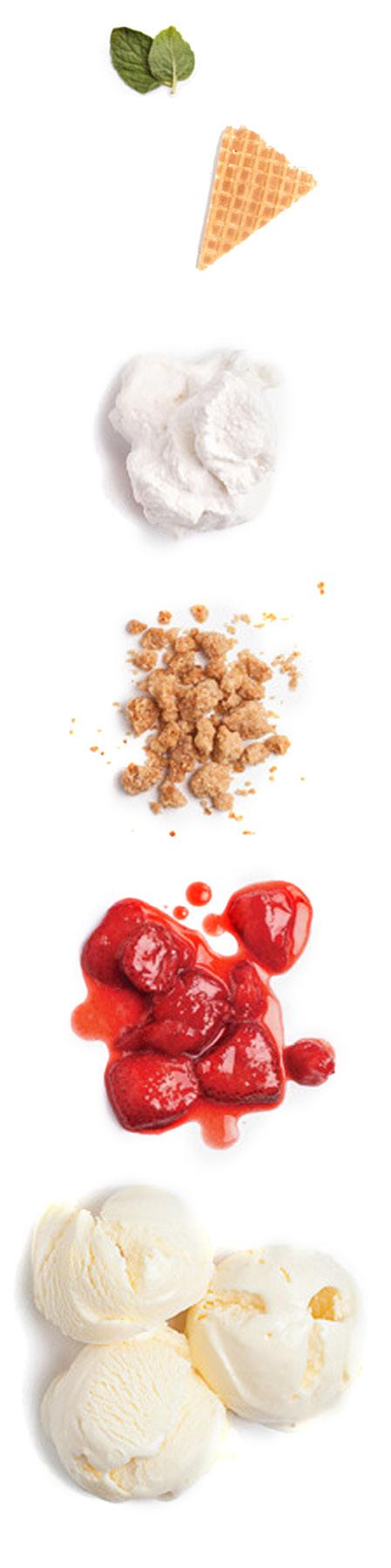

The New Spirit of Capitalism (Boltanski et al, 2005) charts the transformation of capitalism from Fordist hierarchical work structures to a new network-based form of organization founded on autonomy. This can be characterised through ‘fun’ capitalists like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates. The book explains how this form of capitalism uses playful tactics as a more subtle and successful form of exploitation. Although written in 2005 – this form of playful, pernicious capitalism is at the heart of the sharing economy. Considering this, these graphs use quantitative data explain the ingredients of the sharing economy, but are presented alongside a sickly sweet image of an ice cream sundae. These aesthetics reflect the sentiment of the study.

When considering the socio-economic ingredients that encouraged the sharing economy to flourish, arguably the most significant is the digital boom, without which the proliferation of ‘sharing’ never could have happened. Over the last 40 years the number of people with internet access has grown exponentially whilst the cost of bandwidth, storage and computers has relatively plummeted meaning the creation of and access to sharing economy platforms has become easier and easier.

Secondly, models of work that appear more autonomous have also grown in the last 30 years as shown by the increase in freelance workers in the UK, meaning more people are able to carry out sharing economy work in spare time. The other of the same coin of autonomy is a rise in workforce precarity. Zero-hours contracts that offer workers no rights are almost always used by sharing economy employers, here overlapping with the ‘gig economy’, and workers

on these contracts have risen exponentially since the millennium.

The current cost of living crisis also appears fuelling the sharing economy. As people can’t afford things outright, sharing resources becomes necessary. This year, as petrol prices reached unprecedent highs, a rise in downloads of shared mobility apps was recorded suggesting that rather than representing a change in consumer behaviour driven out of choice, people are being forced to share vehicles as they become unable to afford to own them outright.

Idling capacity is the term used to describe the untapped social, economic and environmental value of underused assets. Here although home ownership in the UK has been on a decline since 2002, those with multiple properties is on the rise.

The cherry on top is the impending environmental disaster. As temperatures rise consumers are affecting their behaviour and there is a perception of the sharing economy as ‘eco-friendly’.

excludable subtractable P2P B2C

the degree to which users can be excluded the degree to which consumption by one reduces consumption by others peer to peer business to consumer

Elinor Ostrom (1990), a leading economist in commons theory, argued that the nature of goods is institutionally contingent. In other words, whether a good is public, private or otherwise is not an intrinsic feature of a good but is contestable. This is not to say that the biophysical characteristics of the resource system or the attributes of the good are irrelevant, but rather that they interact with existing institutions. The sharing economy has taken goods and resources that are traditionally privately owned and contested their nature.

This graph shows Ostrom’s original definition of the characteristics a good must hold in order to be a common pool resource, a private good, a public good or a toll good. Subtractability means the degree to which consumption by one user reduces possibility for consumption by others, whilst excludability means the degree to which a user can be excluded. Traditionally, goods and resources that are seen in the sharing economy would have sat in the upper right quadrant, as private goods. To elaborate using the car as an example, when the vehicle is privately owned by an individual, one person using the car prevents another from using it, and whilst the owner holds the keys it is easy to prevent anyone else from using it.

However, Sharing Economy businesses have contested the nature of traditionally private goods by challenging their levels of excludability and excludability. The graph shows a subjective assessment of the standings of different resources in use in Sharing Economy businesses.

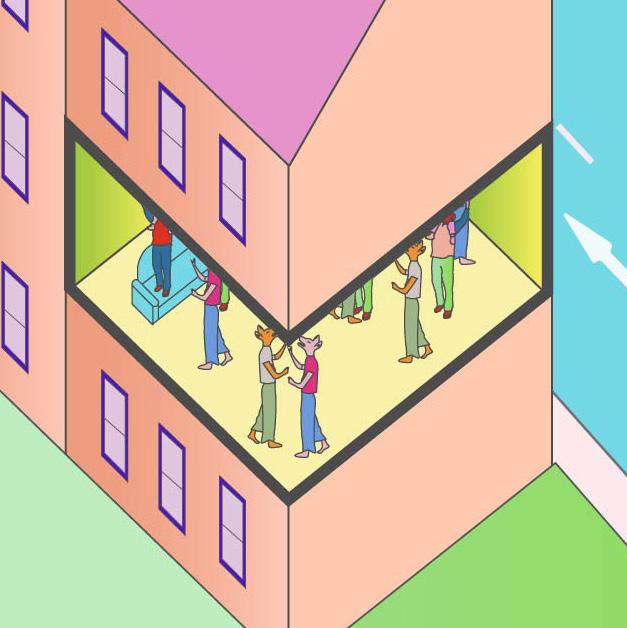

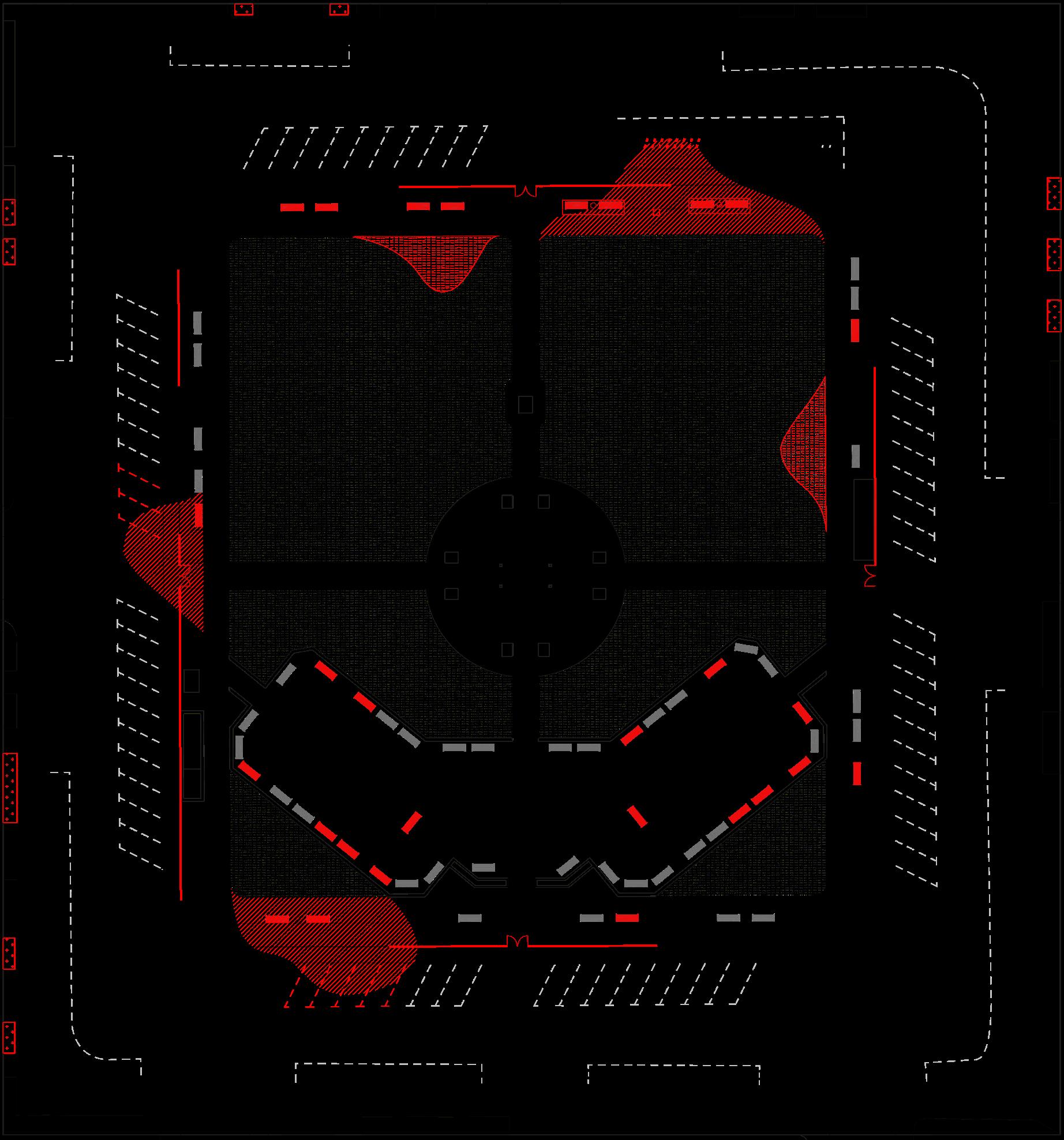

SHARING IS NOT CARING AXONOMETRIC

SHARING IS NOT CARING SCENARIOS

The sharing economy and the move of goods from private to public under contemporary capitalism encourages the view of people as consumers over carers. The philosopher Zygmunt Bauman (2000) introduced a concept he called ‘liquid modernity’, which describes the transition of society from a ‘heavy’ and ‘solid’ hardware focussed modernity to a ‘light’ and ‘liquid’ software-based modernity. Although written 13 years before the appearance of the sharing economy, Bauman forecasted the societal drift away from private, personal ownership of hardware. Bauman goes on to discuss the problems with the freedoms afforded by liquid modernity, positing that ‘having’ has been replaced by ‘being’.

Eula Biss’s new book Having and Being Had (2020), starts with the author buying a house, but the purchase is a reality she struggles to grasp. ‘The house isn’t mine’, she states. ‘I don’t so much own it as take care of it.’ In a following section titled ‘Husbandry’, Biss goes on to discuss how she takes care of the roses in the front garden even though she doesn’t like them. It is a condition of her ownership of the house. When something is owned, you become it’s custodian. Ownership essentially means you are taking care of something, you perform acts of husbandry to prolong the life of your possession.

For customers, one of the key offerings of the sharing economy is a relief from care –you are not responsible for the longevity of a Zipcar in the way you are with your own vehicle. More broadly, care for things has little place in an economy based on brief or provisional ownership and fast replacement (Rogers, 2021). Caring for things is not an imperative in an economy bent on growth; in fact, it’s often tacitly discouraged. After all, caring for things makes them last.

If owning is caring, then the current state of sharing is consuming. Consumption suggests using something up or absorbing it completely. Whilst humans do need to consume food and fuel to survive, we are now encouraged to consume electronics, furniture and even homes too. As seen in figures 20-23, sharing under contemporary capitalism encourages the view of objects as consumable as destructive and

careless behaviour prevails.

‘In the history of the world, nobody has ever washed a rented car.’ Although the definite origin of this quote is impossible to locate, this is a witticism most commonly attributed to Lawrence Summers, the ex-president of Harvard. The claim that Summers is making is that people don’t invest in things that they don’t own. By implication, it’s also a pitch for an ownership society, one where people own their homes and all of their belongings, and are thus incentivised to care for all of the above.

But are traditional models of private ownership really necessary to encourage care? So far, this section has shown that the current dominant model of sharing, the sharing economy, is eliminating care; but what are the alternatives?

These interventions use the practice of care as a methodology to combat consumption. The IKEA effect (Norton et al, 2011) refers to the increased attachment people feel for products they have had to invest time into building. What if this is extended to the practice of caring, would there be an increased attachment to objects if people were incentivised to care for them, thereby reducing a need for consumption?

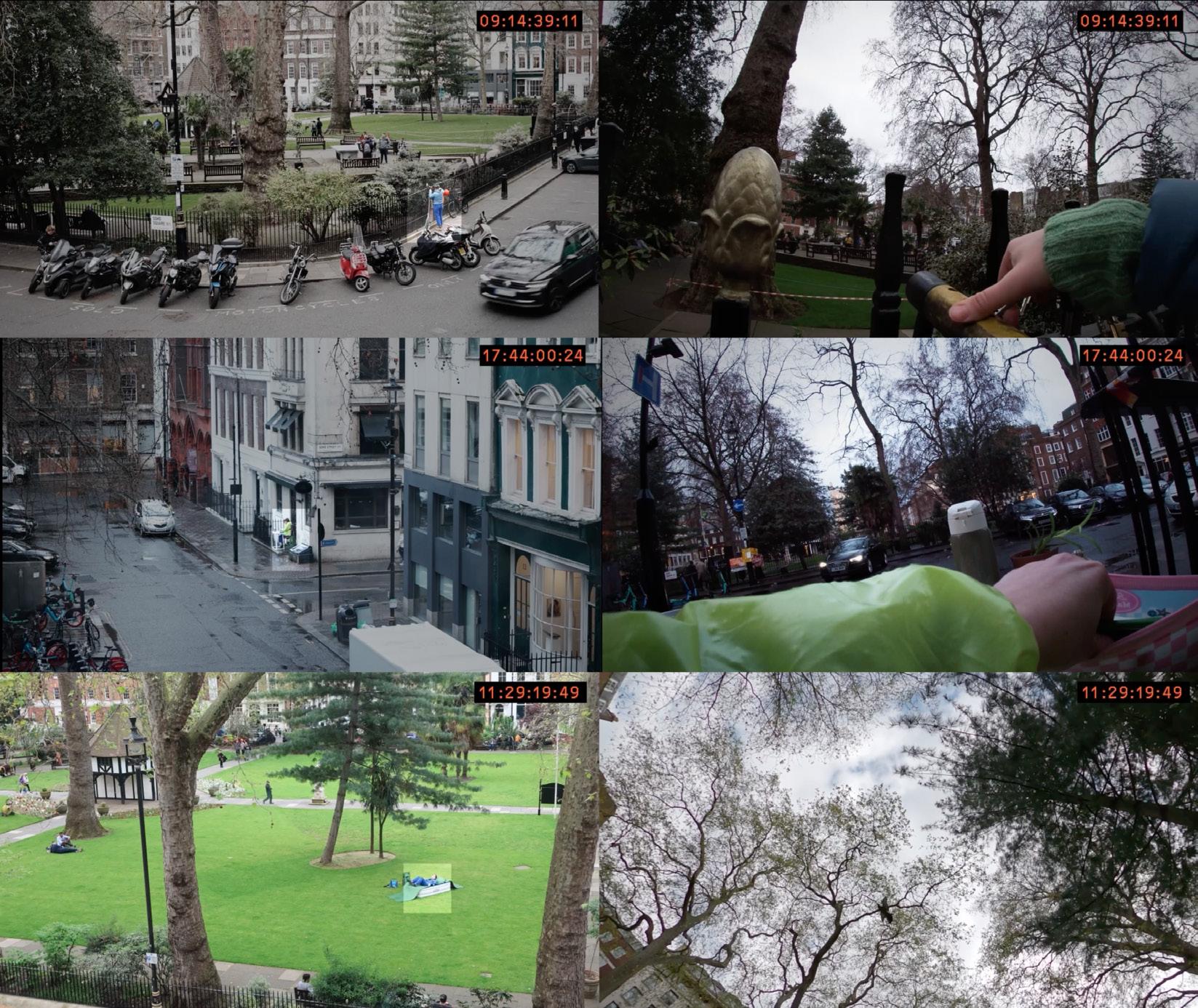

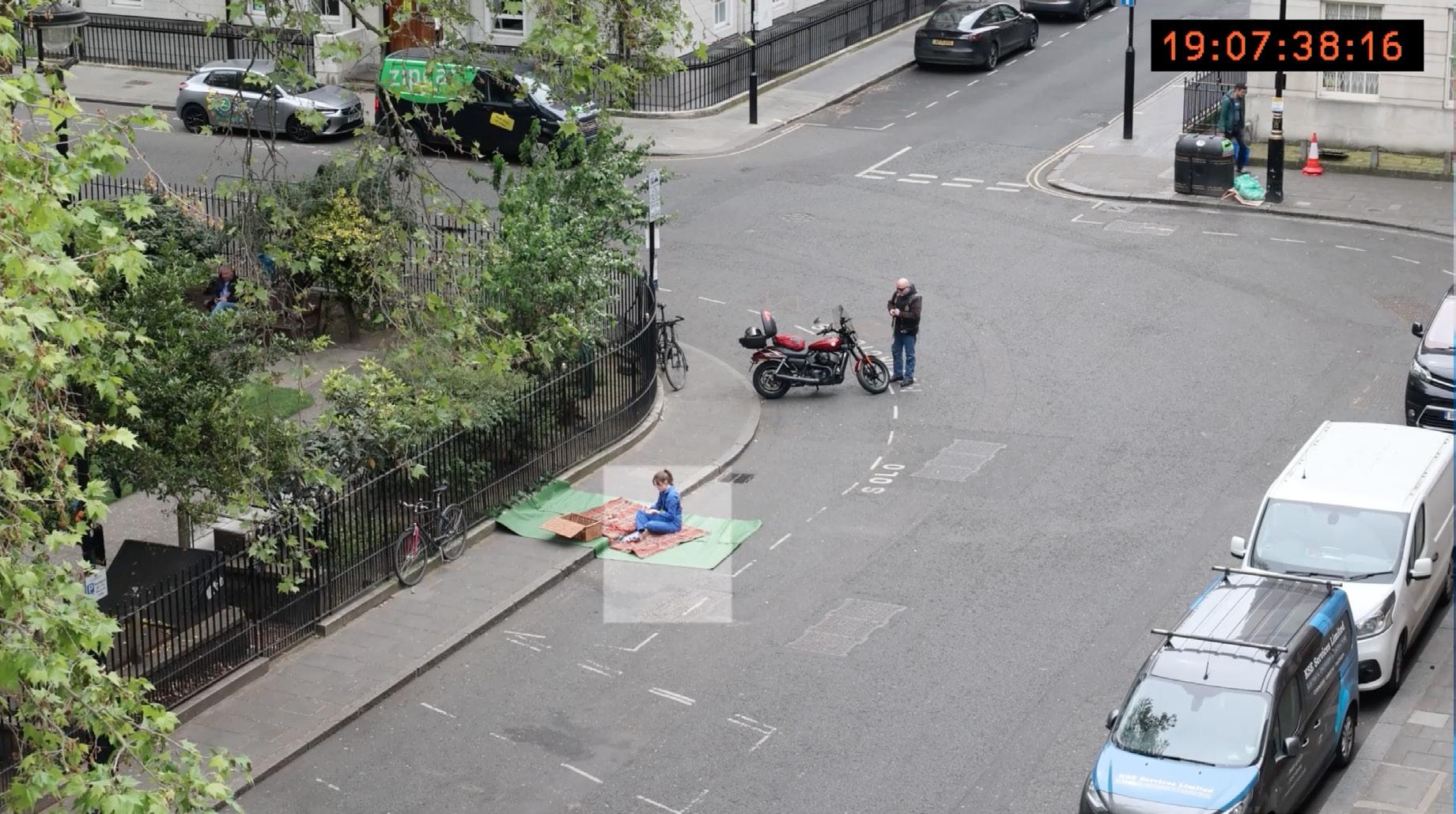

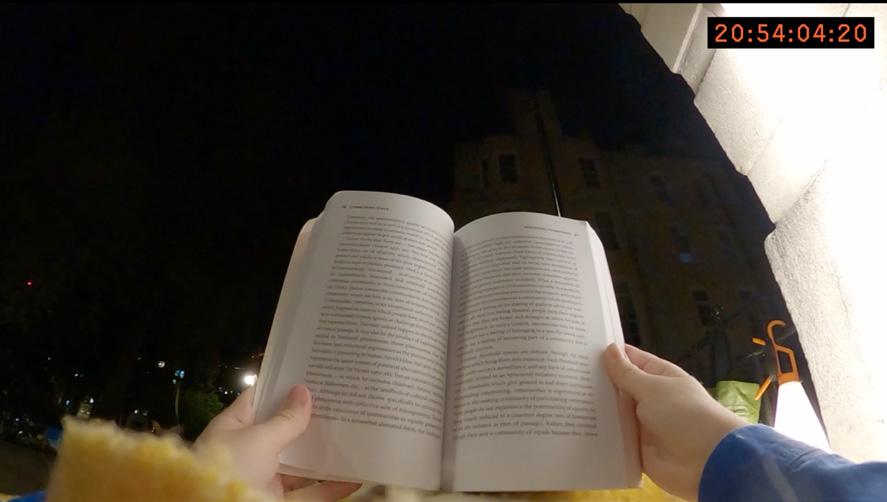

A series of performances at a 1:1 scale have been performed to insert subtle acts of care into uncaring Sharing Economy networks and to raise awareness that sharing is not caring. Three different acts of husbandry took place in the form of washing a Zipcar, servicing a Lime bike, and mending a rented dress from ByRotation. These acts of care were filmed from two perspectives: firstly using a camera at distance from the activity representing the effect on the urban scale, and secondly through wearing a GoPro to zoom into the action. The films are then showed on iPhones and iPads side by side so both perspectives are understood at once. These public performances are used to question public perceptions of contemporary sharing and caring.

Bauman, Z. (2000) Liquid modernity. Cambridge: Polity.

Biss, E. (2020) Having and Being Had. S.l.: Faber and Faber.

Boltanski, L., Chiapello, E. and Elliott, G. (2018) The new spirit of capitalism. London: Verso.

Botsman, R. and Rogers, R. (2011) What’s mine is yours: The rise of collaborative consumption. London: Collins.

Hern, A. (2015) Why the term ‘sharing economy’ needs to die, The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Available at: https://www.theguardian. com/technology/2015/oct/05/why-the-termsharing-economy-needs-to-die (Accessed: December 19, 2022).

Le Jeune, S. (2016) “The Sharing Economy.” London: Schroders.

Norton, M.I., Mochon, D. and Ariely, D. (2011) “The ‘ikea effect’: When labor leads to Love,” SSRN Electronic Journal [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1777100.

Ostrom, E. (1990) Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rogers, L. (2021) The sharing not caring economy, Architectural Review. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/ books/the-sharing-not-caring-economy (Accessed: December 19, 2022).

Spiliakos, A. (2019) Tragedy of the commons: Examples & solutions: HBS Online, Business Insights Blog. Available at: https://online.hbs. edu/blog/post/tragedy-of-the-commonsimpact-on-sustainability-issues (Accessed: December 19, 2022).

Sundararajan, A. (2017) The sharing economy: The end of employment and the rise of crowdbased capitalism. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

RCA ADS7

Book 2 Commoning Soho Square Marnie Slotover

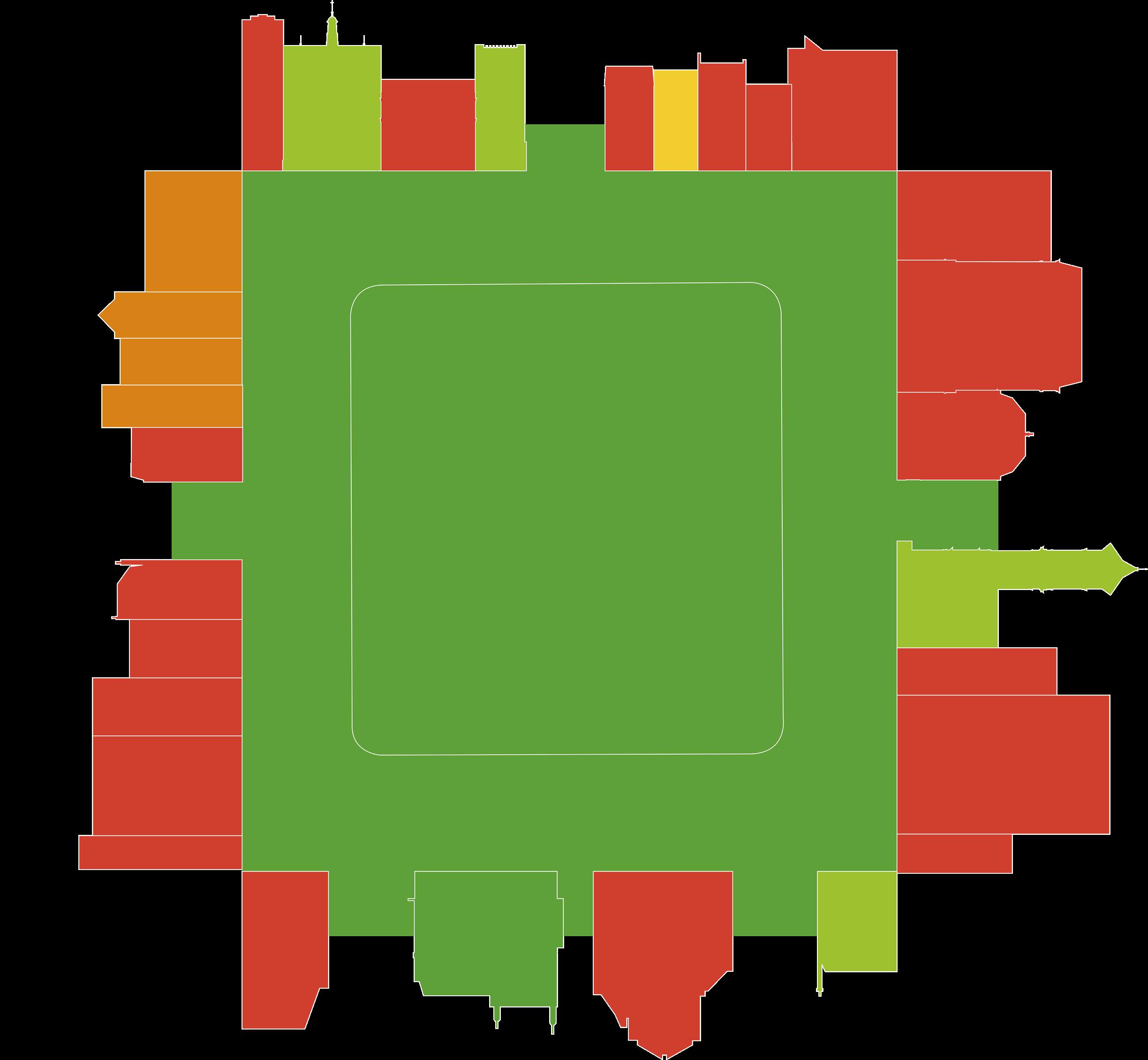

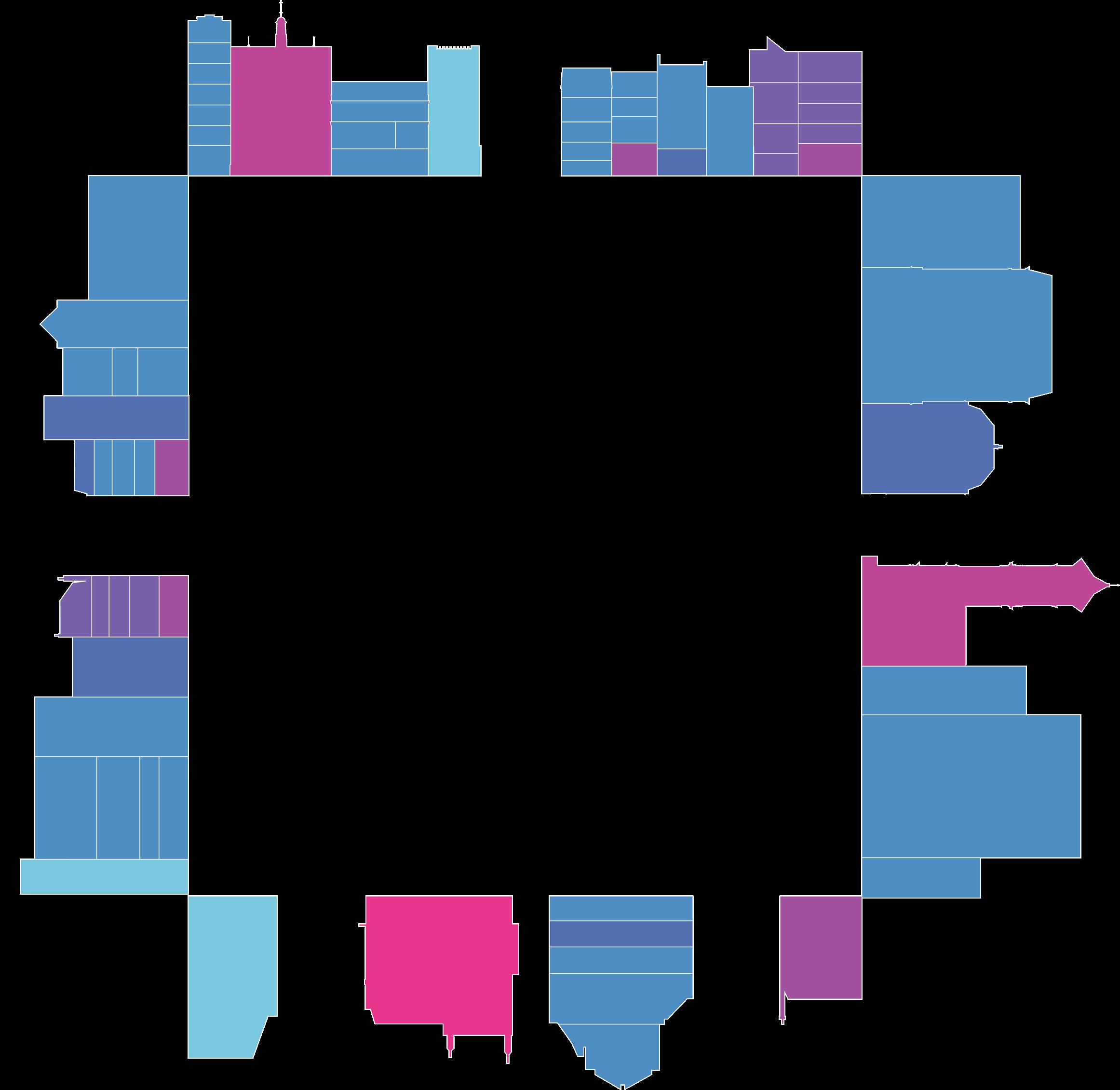

RESIDENTIAL COMMERCIAL HEALTH

Book 3

Commoning Soho Square Marnie Slotover

RCA ADS7

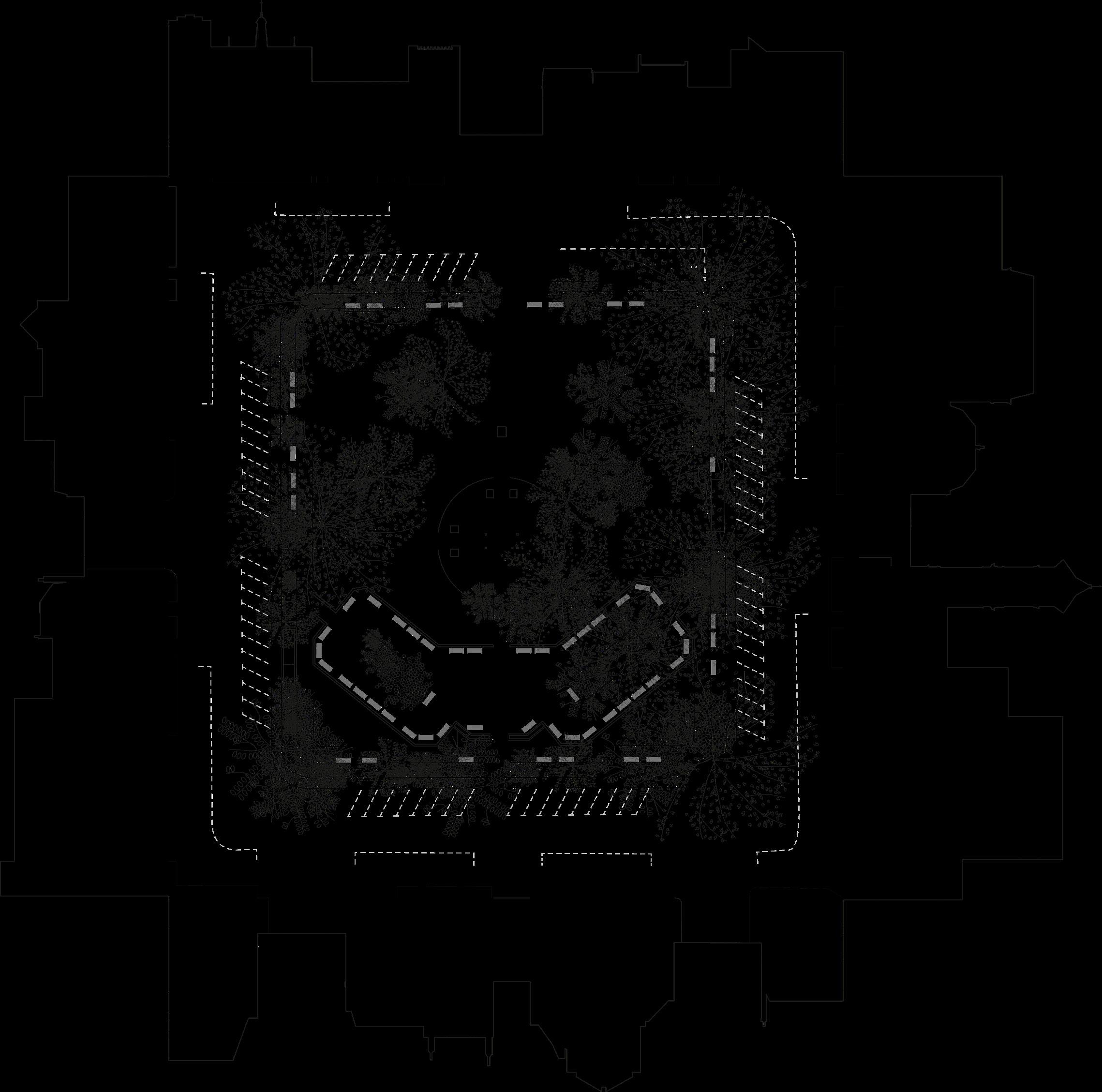

Soho Square has been located as a site of saturation (see book 2, Huron 2016), meaning it is a site where urban commons should already be appearing. Before proposing any changes to the space, it is imperative to understand how, if and when practices of commoning are appearing in the square.

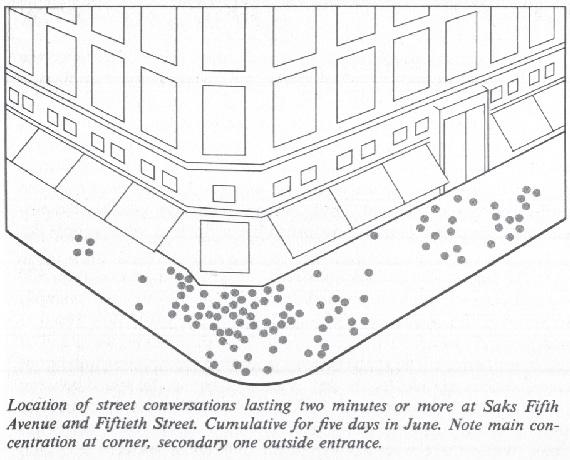

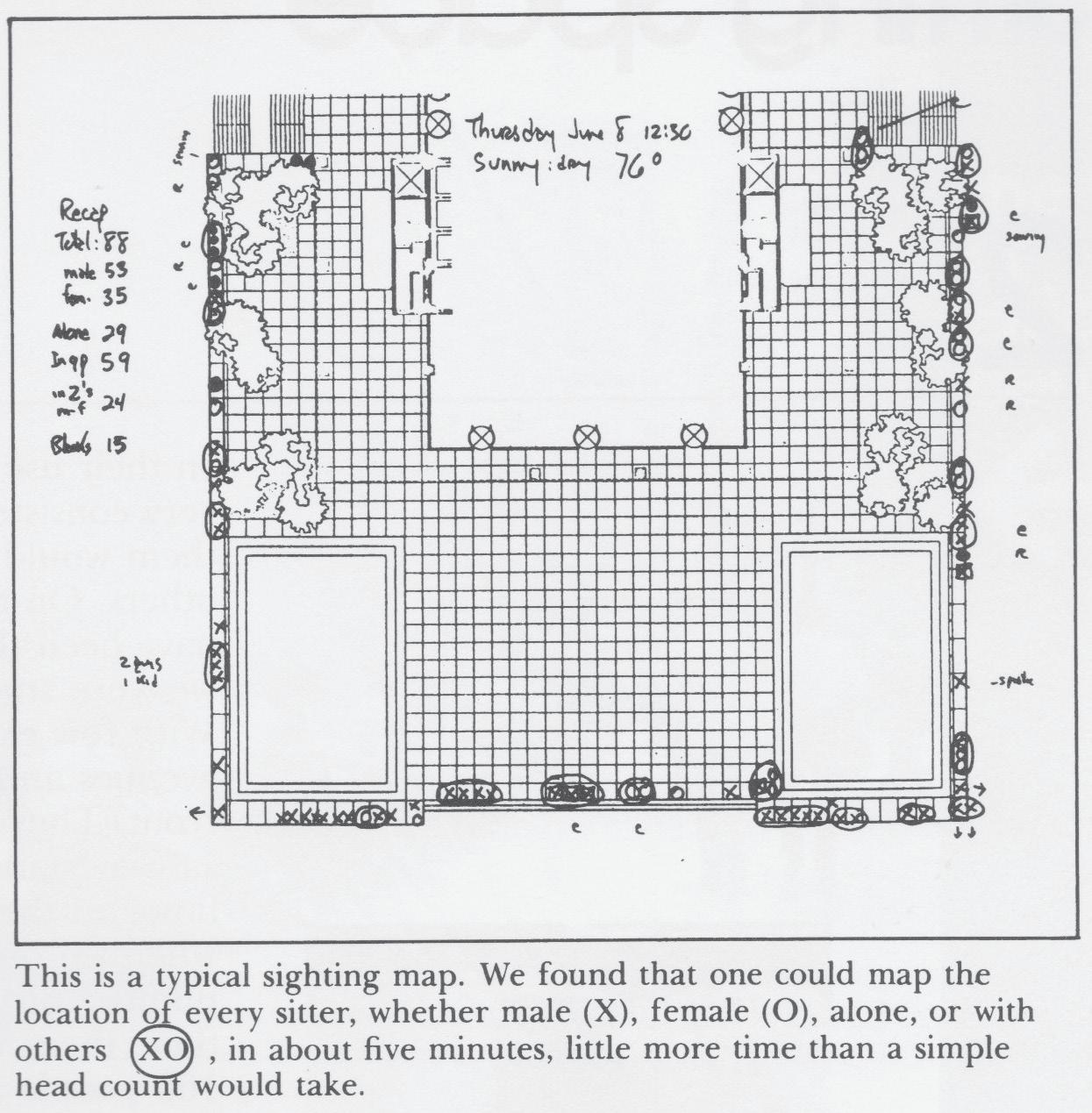

In 1980, William H Whyte published ‘The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces’ as a manual for creating successful and interesting public spaces that people want to use. His findings were based on observational research - getting out there and looking at people - as well as on the

ground-breaking use of time-lapse photography in New York. Although the research took place 40 years ago, this methodology is still relevant as tensions in the public realm are present - just look at the fallen e-bike.

Taking inspiration from Whyte, a 24 hour site visit took place over 4 months in 2-4 hour slots. By witnessing the square over the full spectrum of the day and night recording through photography and notation of activity, a profile of how and when people are actually using the space is created.

Inventory of Visits to Soho Square

Studies from William H Whyte’s ‘The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces’

Inventory of Visits to Soho Square

Studies from William H Whyte’s ‘The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces’

Soho Square sits at the centre of the capitalisation of sharing. How can people share space and resources successfully under these conditions? Here the theory of the urban commons becomes relevant.

Historically, the term ‘commons’ referred to natural resources that are collectively owned or owned by no one, such as the ocean or forests (Eizenberg, 2011). Conversely, the term urban commons has only gained popularity over the past 20 years, with the majority of literature available being from 2000s and 2010s. The notion of ‘urban commons’, which is associated with the work of David Harvey (2012), focusses more closely on public, civic spaces and their design.

The urban commons are not understood as static spaces, but rather processes and practices that are ‘created, maintained and defended’ (Gillespie et al, 2018) through the everyday activities of citizens. Spaces and goods in the public domain become urban commons when citizens appropriate them through collective action (Harvey, 2012). As

explained by Williams (2017), ‘urban commons are characterised in the literature as collectively shared property in the city shaped by a context of scarce resources, population density, and the interaction of strangers.’

Stavros Stavrides (2016), introduces the concept of ‘practices of commoning’ in his book ‘Common Space’. Stavrides defines common space as ‘a set of spatial relations produced by commoning practices’ that ‘create forms of social life, forms of life-in-common’. He therefore positions common spaces as distinct from public and private spaces, in that they emerge as sites open to public use and have rules and forms that are not dependent upon a prevailing authority.

The 24 hour study seeks for evidence of practices of commoning, practices that do not follow the dominant rules and forms of use of the space. Gibson Graham et al (2013) created an identi-kit to help identify commons. This is used through the site study to help identify practices of commoning.

COMMONS IDENTI-KIT ACCESS USE

SHARED AND WIDE

NEGOTIATED BY A COMMUNITY

BENEFIT

WIDELY DISTRIBUTED TO COMMUNITY MEMBERS (AND BEYOND)

CARE AND RESPONSIBILITY

PERFORMED BY AND ASSUMED BY COMMUNITY MEMBERS

PROPERTY

ANY FORM OF OWNERSHIP (PRIVATE, STATE OR OPEN ACCESS)

The practices of commoning were recorded primarily using photography. A small, pocketsized digital camera was used with the flash on to capture the traces of commoned spots. Direct pictures of people inhabiting the space were avoided as not to interfere or cause any discomfort, some activities are sensitive so looking for traces felt more appropriate.

Upon early visits to the square before the method was established, the reseach focussed on finding out who is taking care of the square.

Whilst taking these photos with the digital camera (flash on), the reflective material present

on both the clothing of the maintainers and their tools lit up.

In order to identify and highlight the practices of commoning present in the photos, three reflective markers were made to point to, sit atop or sit amongst the photos.

The markers, in the style of forensics, point out those who are maintaining the square as a common space, as opposed to a public space.

The style of forensics is appropriate as the behaviour of the commoners sits outside of what is considered desirable, or ‘allowed’ in public space.

Reflective moments from the maintainers

Commoning markers

Reflective moments from the maintainers

Commoning markers

EATING DRINKING

SITTING

LOCKING

WORKING

CHATTING

LISTENING TO MUSIC

PLAYING

EXERCISING

STANDING

LITTERING

WAITING

FEEDING

SLEEPING

VANDALISING

CLEANING

SMOKING

KISSING

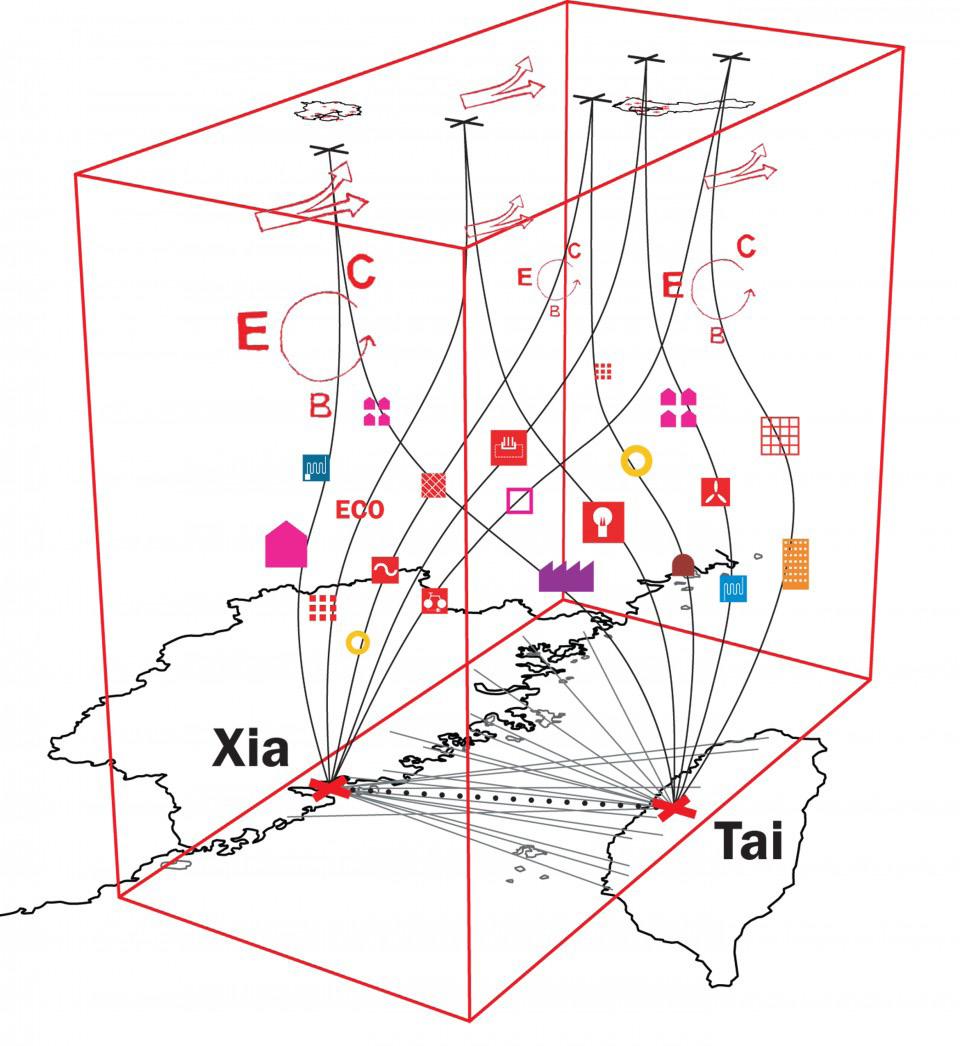

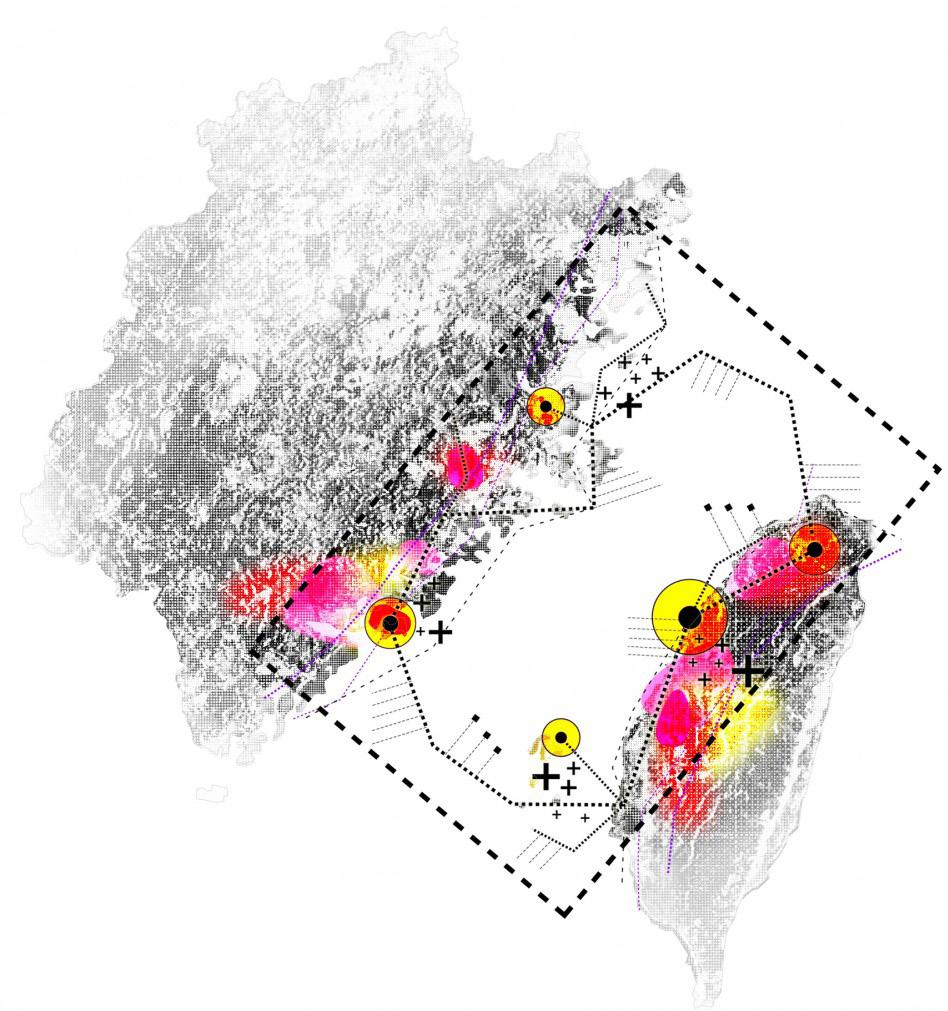

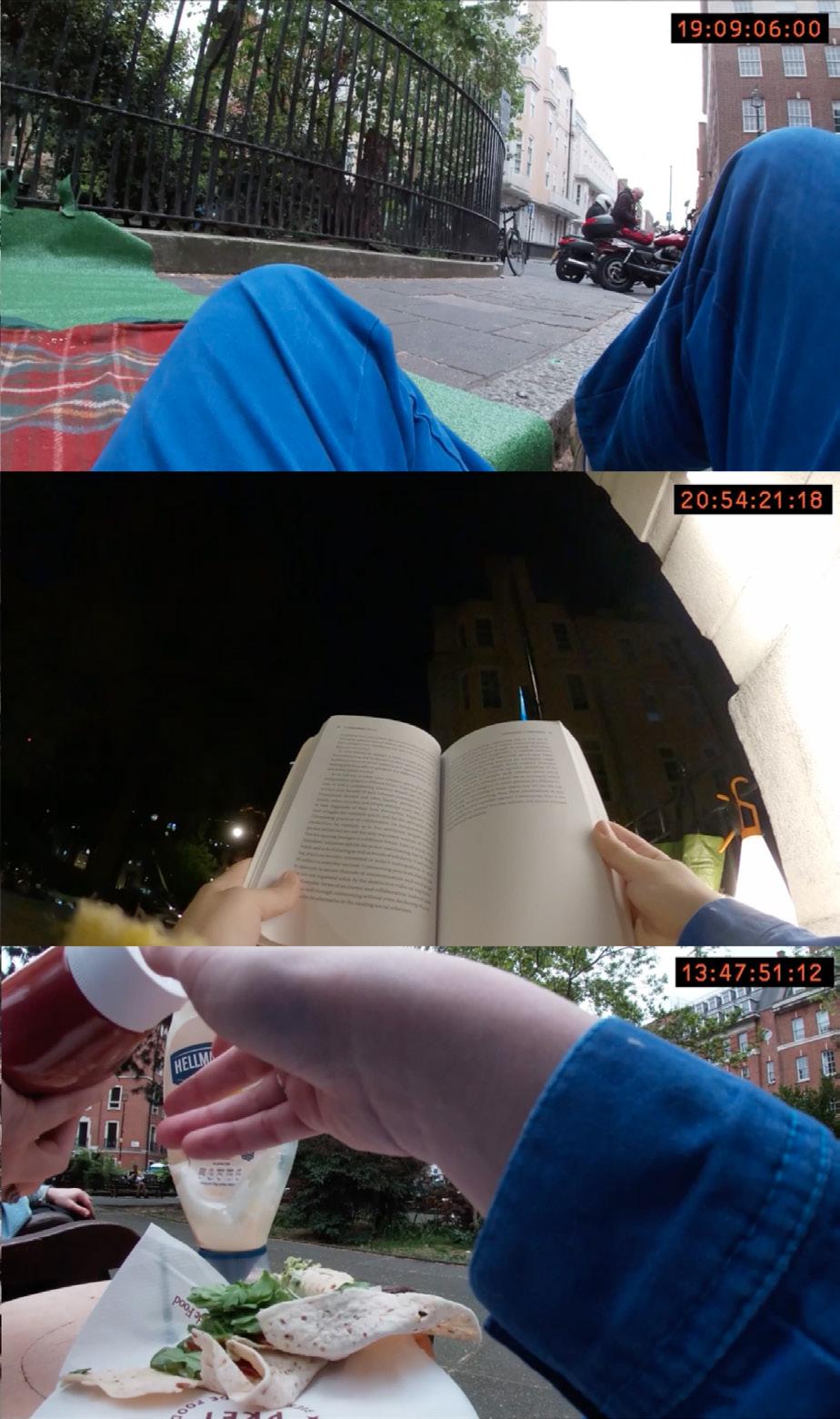

Chora is the name of a research office founded in London by Raoul Bunschoten in 1993 and also of a parallel architectural office established in 1994. Their methodology is grounded in research, consisting of a four step process that comprises of: a database, prototypes, scenario games, and action plans.

Chora have developed a complex language of diagrams and symbols that takes the large amounts of specific information gathered for each project and makes abstract notations that allow comparison and manipulation of the material.

This method allows Chora to work at a number of different scales, drawing out

unexpected and hidden links between the smallest of local details and transnational or global forces, highlighting how these may impact on each other.

Rather than designing objects and buildings, Chora’s urban curator designs processes, interactions and organisational structures, a way of working that allows the architect to engage a wide variety of people and to create urban strategies that can address the dynamic nature of cities.

When choosing how to notate the observed acts of commoning, the work of Chora helped to inform how complex layers of information can be shown together.

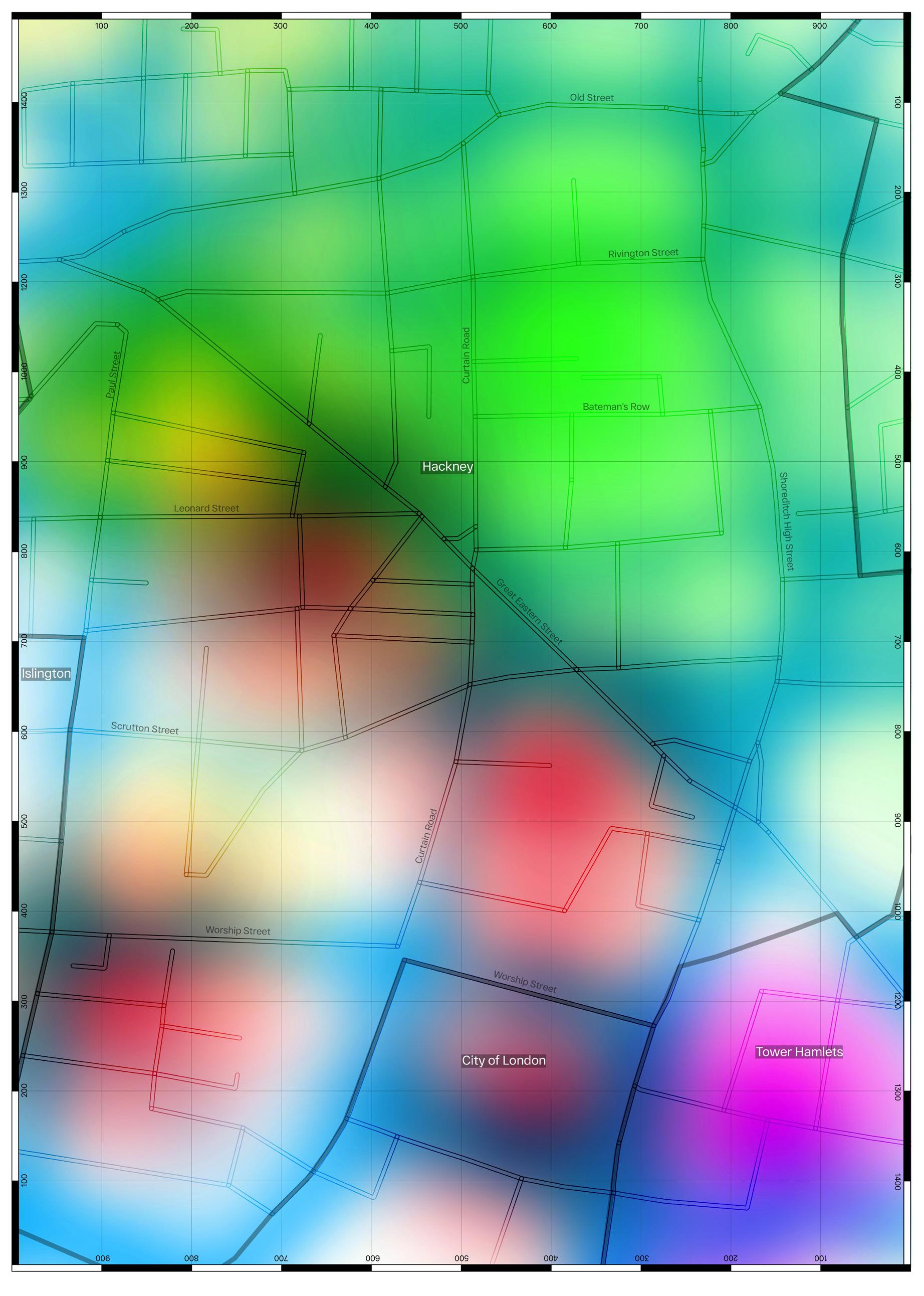

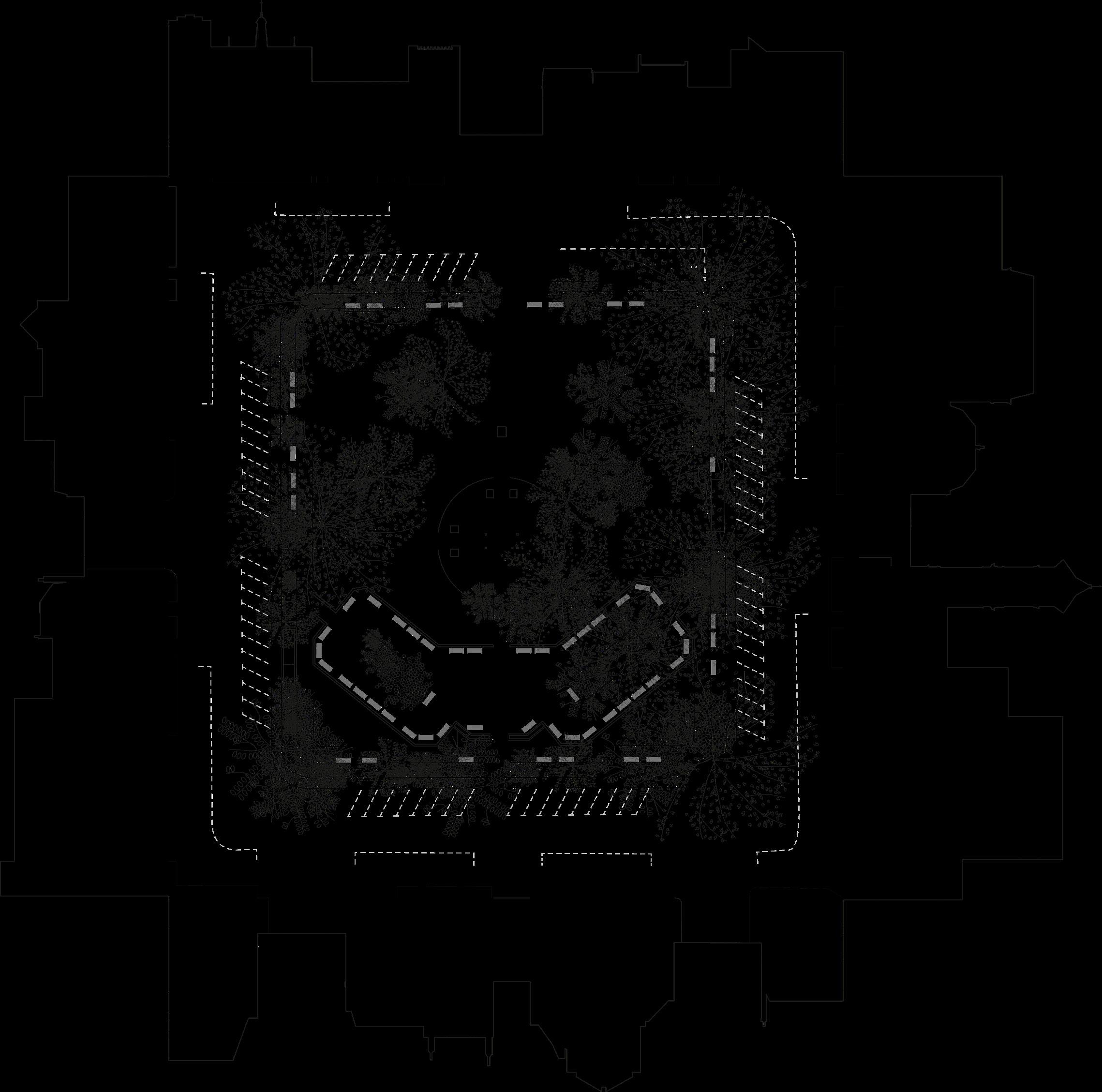

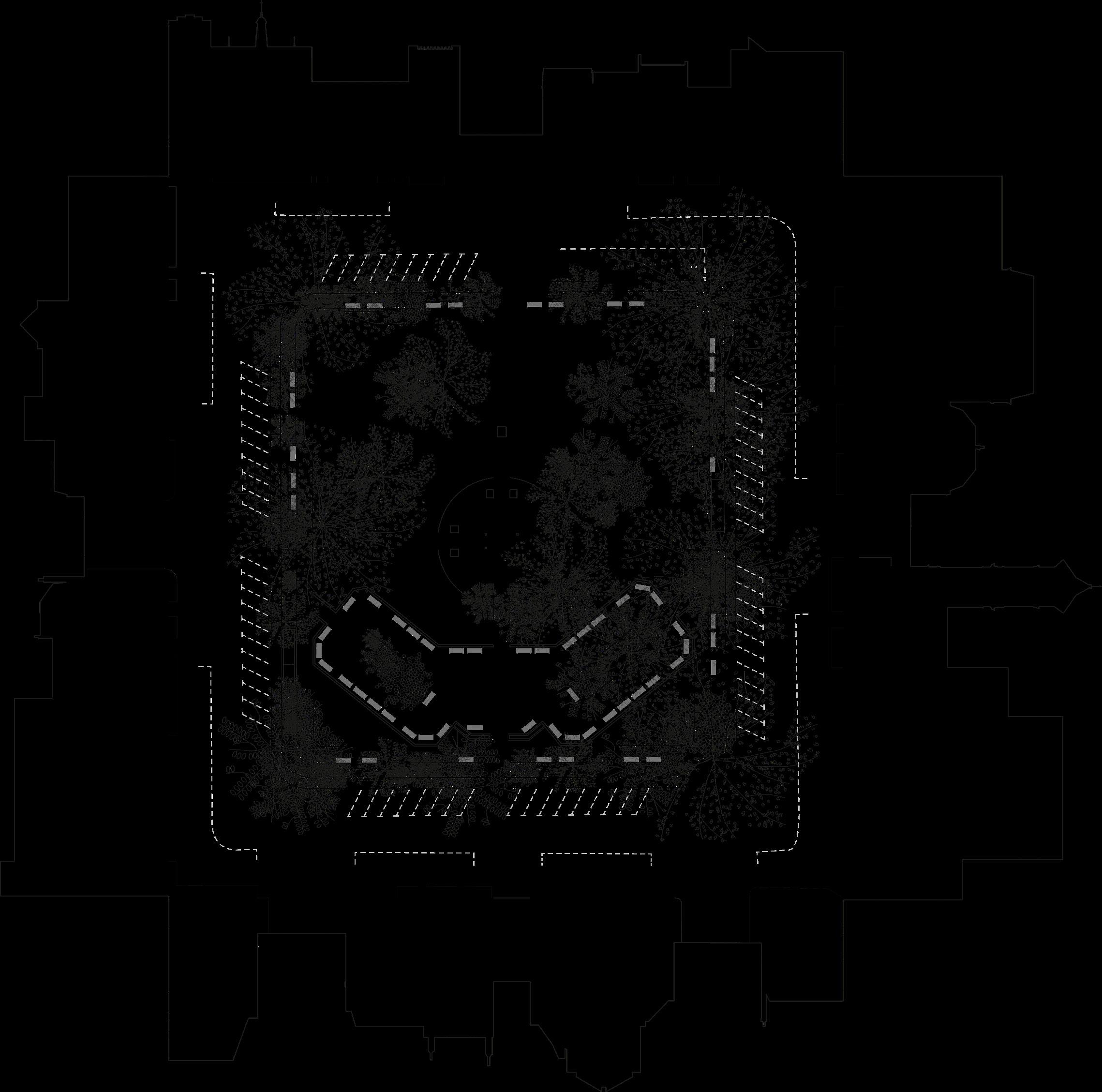

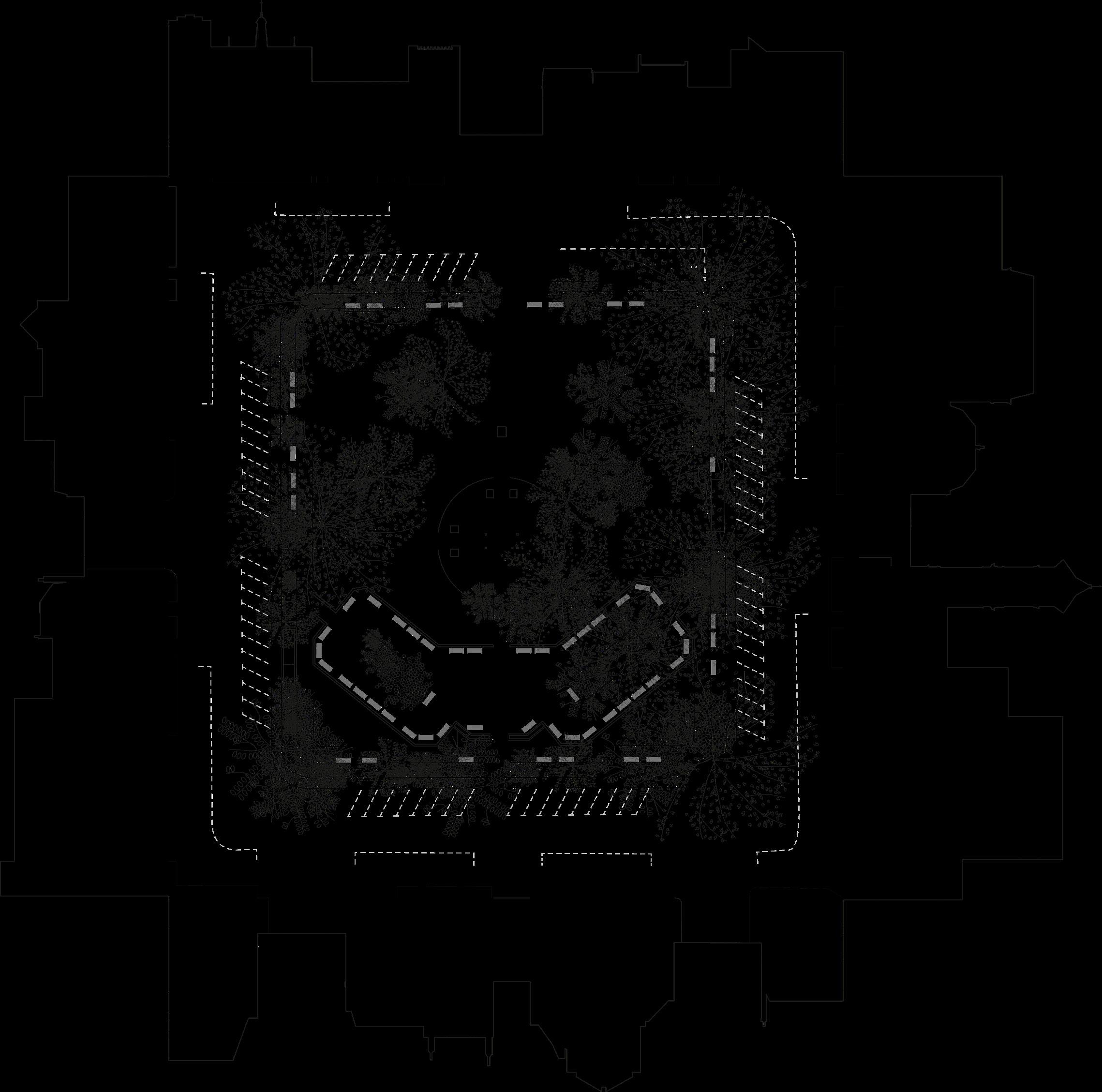

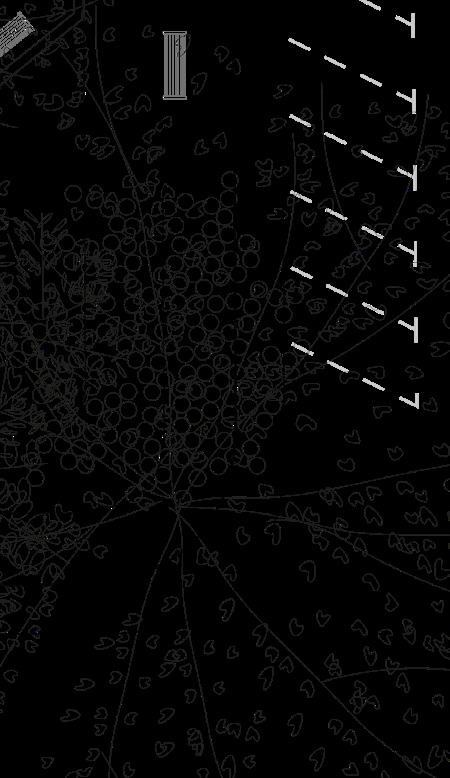

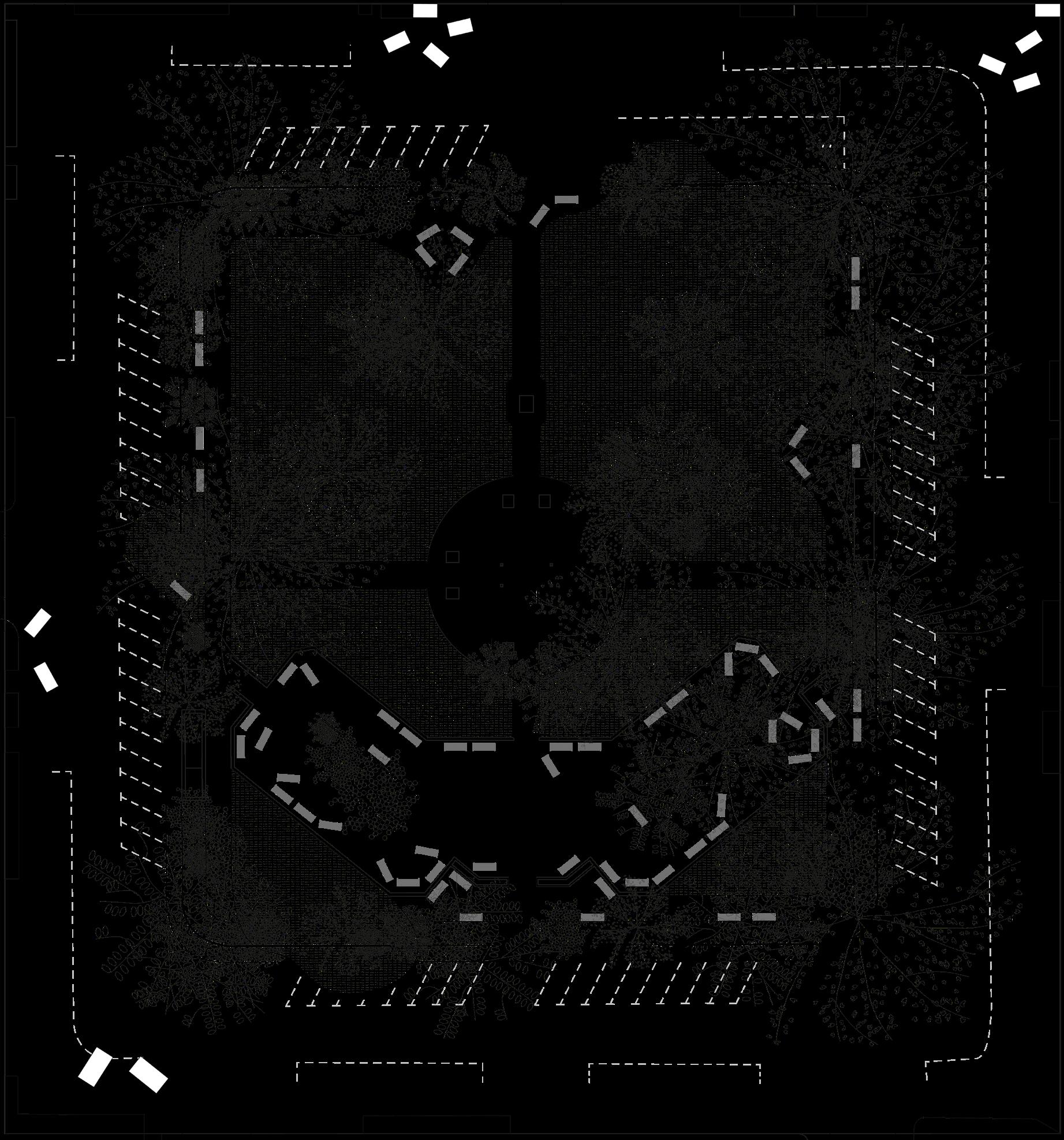

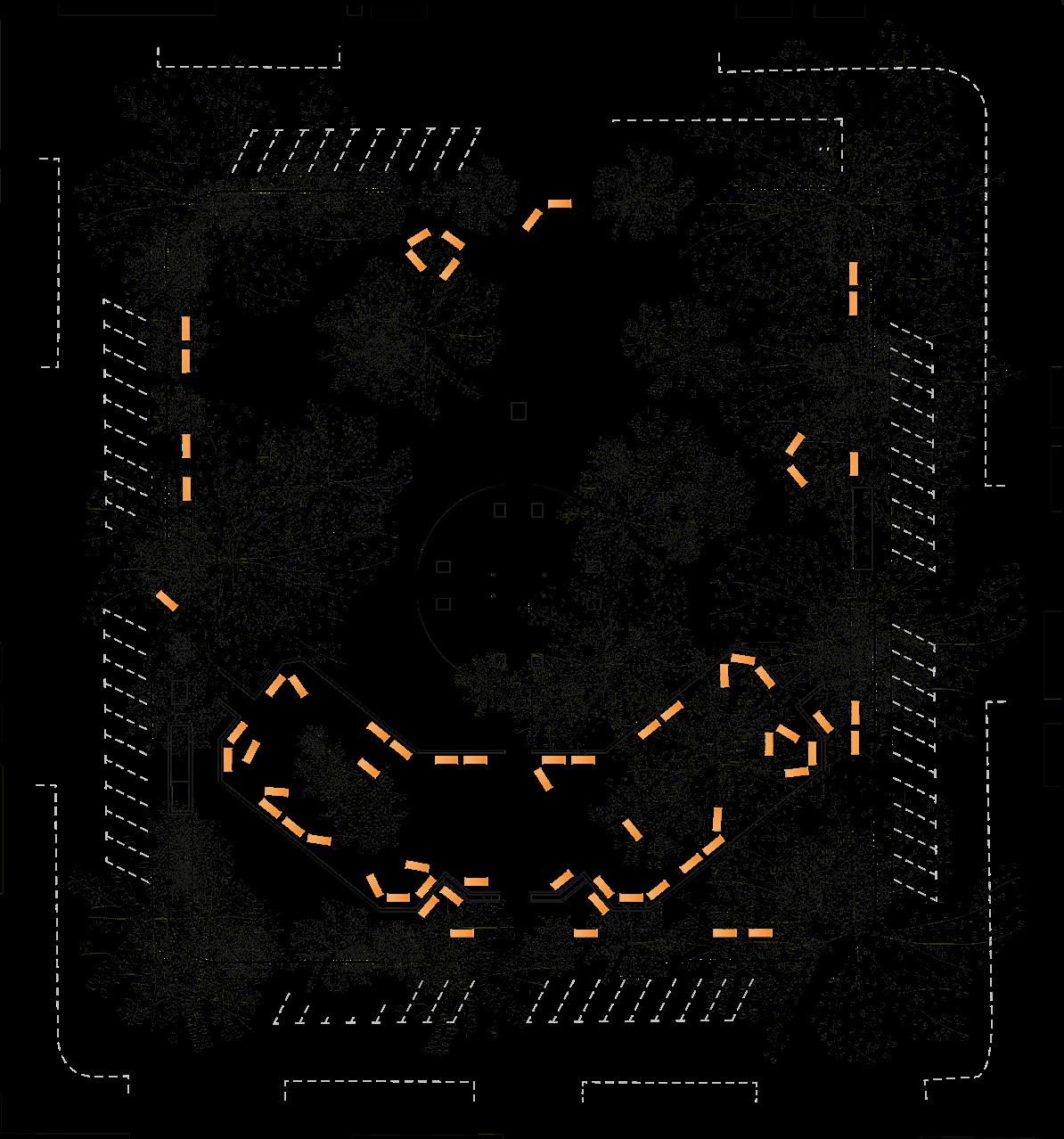

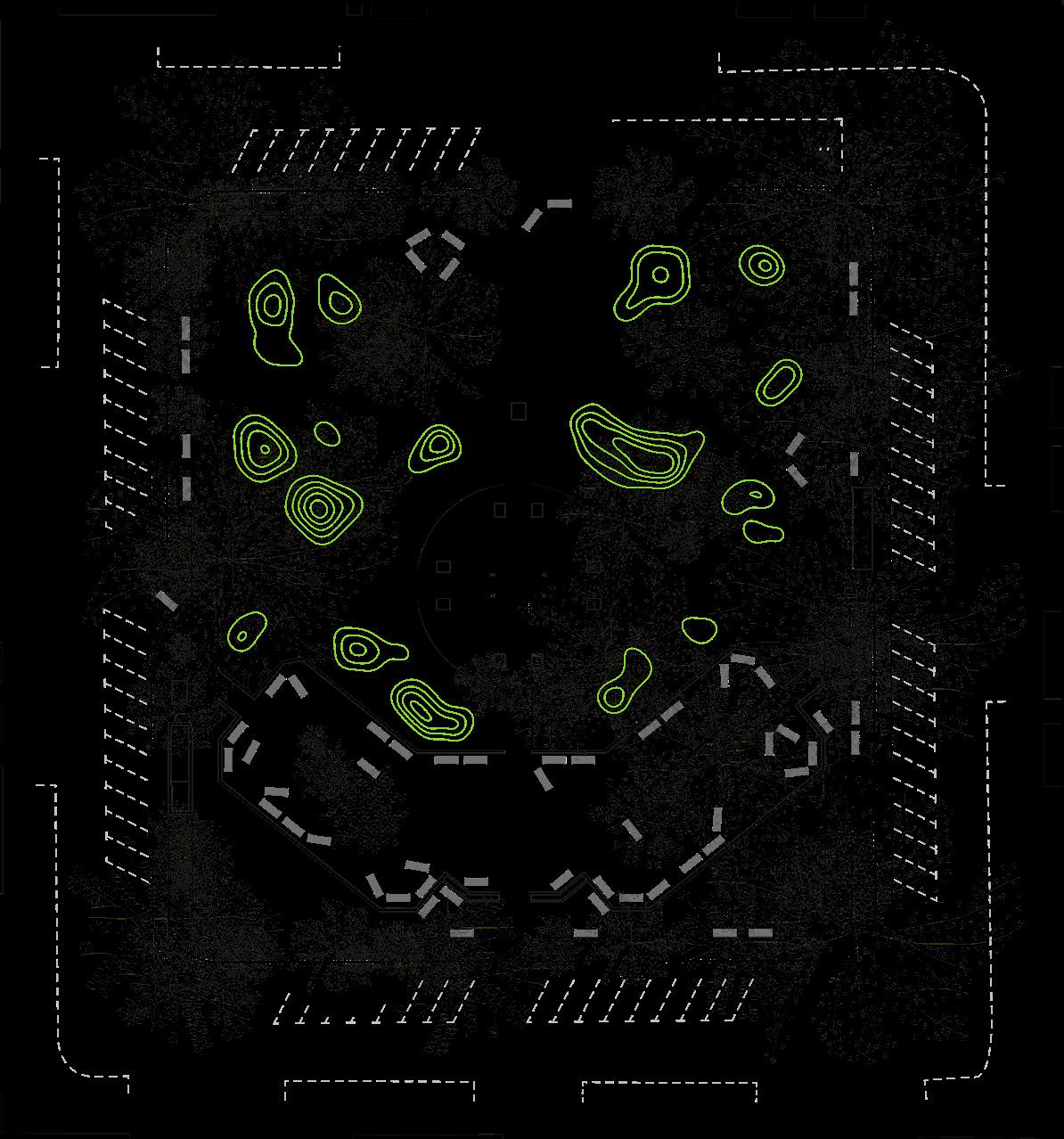

The activities were then plotted into GIS and, through the use of the heatmap function, certain areas appear as hotspots of commoning. The areas which show as clear on the overlay of this page highlight a density of points on the map.

Many hundreds of photographs were taken during the study, but over the next pages they have been categorised not by time, but by area.

Each photograph has a timestamp and is located on a plan of the site. Locating these moments with specificity - to the minute and to the paving stone - is key to the methodology.

In the project installation, the photographs are projected in a 2 minute montage onto a

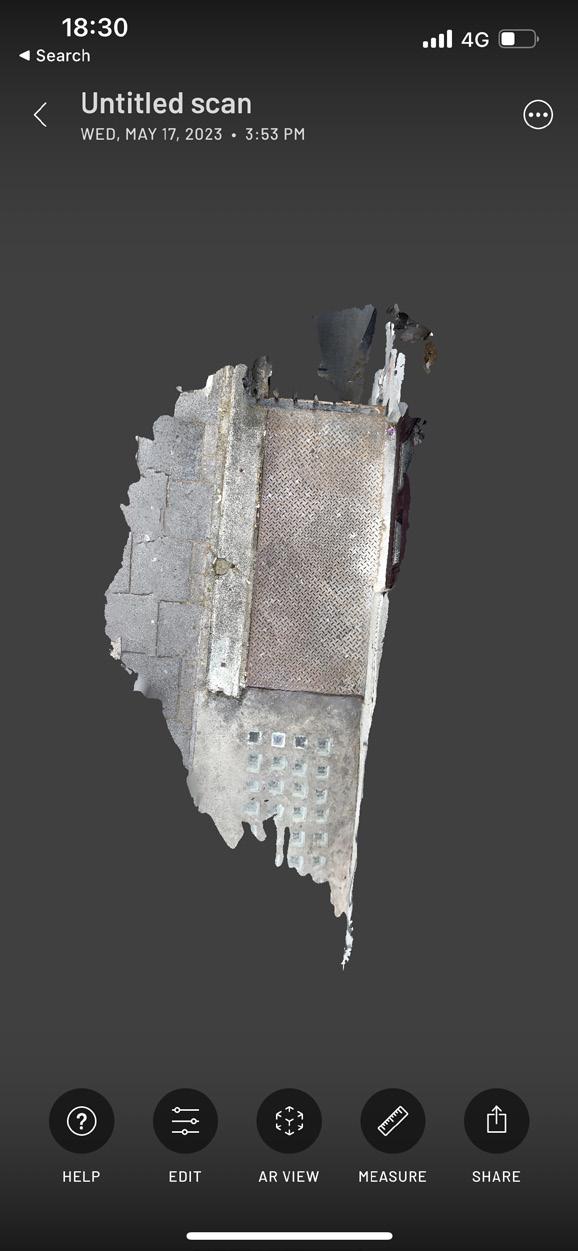

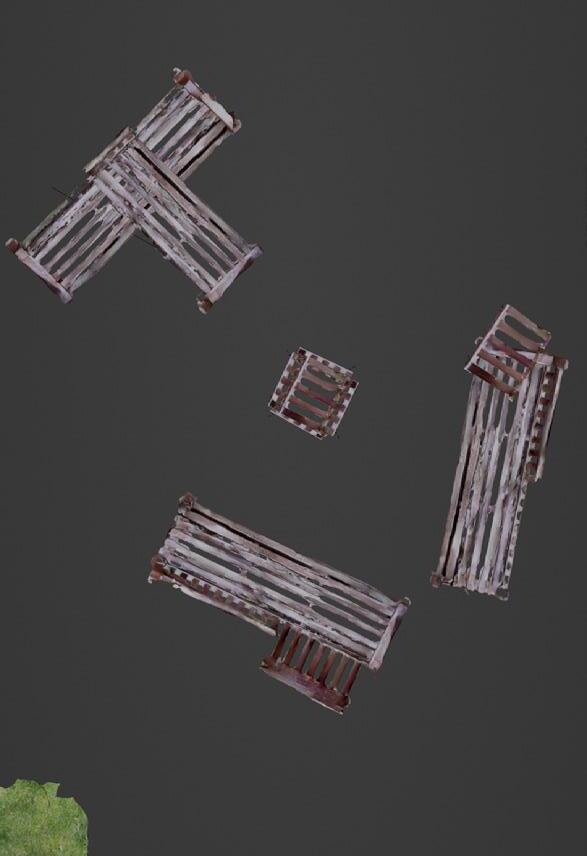

highly detailed model at a 1:100 scale, which shows every part of the square, down to the 3D scanned and printed tree trunks to each manhole cover. Below are some of the laser files used to engrave the model.

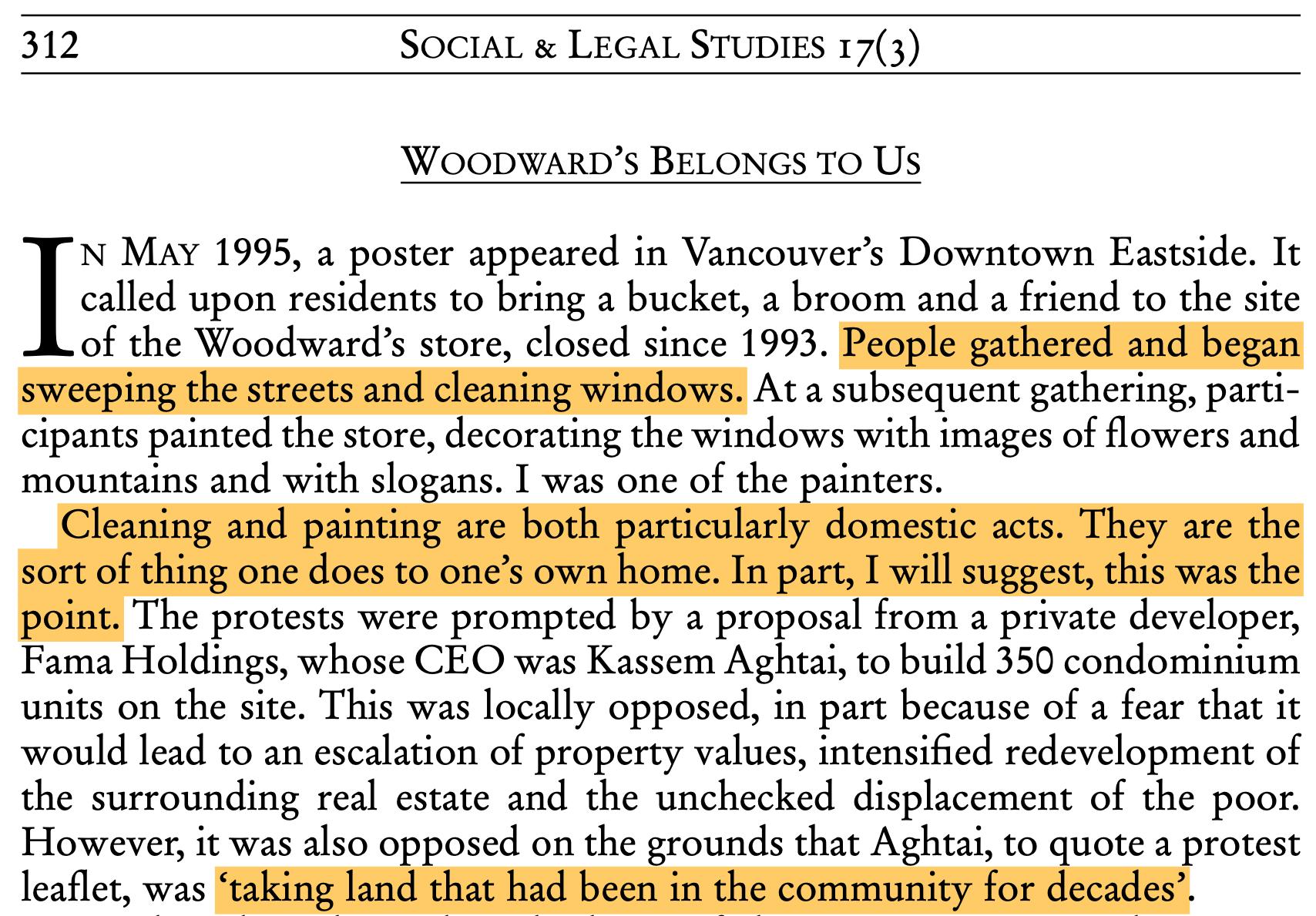

Nicholas Blomley’s paper ‘Enclosure, Common Right and the Property of the Poor’ investigates the common property rights of city inhabitants. In the opening paragraph, he outlines a protest in Vancouver, where people cleaned a property as a way of proving that is

is theirs. Similarly to the care interventions in Book 1, the photographs in this book see acts of commoning as a form of care. If you treat something as if it is yours, it becomes yours if only for the moment of use.

Richard Wentworth’s ongoing series, ‘Making do and Getting By’, documents the everyday, paying attention to objects, occasional and involuntary geometries as well as uncanny situations that often go unnoticed. The style of the photographs are zoomed in, and often focus

on the trace of human activity rather than the human itself. Wentworth’s style of photography informed the site study. He documents unexpected moments in the city, and people appropriating elements for which they were not initially intended.

Photographs from Wentworth’s ‘Making Do and Getting By’

Photographs from Wentworth’s ‘Making Do and Getting By’

Tomiya Suhayahisa documents a table tennis table through the seasons in his book. The photographs illustrate the many uses for one item.

The appropriation of the object for whatever the users see fit can be described as acts of

commoning - the spatial qualities of the table tennis table are useful for many different activities. In the site photographs, the same element, for example the fence, is appropriated by different actors for different uses time and time again.

The s econd p art of the design m ethodology advocates for the designer to t ake action a t a 1:1 scale on s ite. The constructed observations take t he s patial qualities of s ix commoned spots in Soho Square and a mplify them using designed p rops during site a ctivations. This tests how the acts o f commoning h ave occurred and l ooks f orward t o how the practices can be facilitated.

Each o f the six site a ctivations p resent an agenda f or h ow common space should be designed, all rooted in real life observations.

Book 4

Commoning Soho Square

Marnie Slotover

RCA ADS7

This book outlines the next stage of the methodology, titled constructing observations. Once identified, the spatial qualities of the hotspots of commoning are analysed to understand what it is about this exact location that encourages users to create the common space.

After this, 1:1 site activations take place in the exact spot, re-enacting and amplifying the original activity aided by props that enhance the identified spatial qualities.

The constructed observations take cues from forensic reenactments. Additionally, historic reenactments date back to Roman times when ancient battles were performed in ampitheatres, and were used to promote public engagement.

By practicing the act of commoning myself, as the designer, I am able to get into the mind of the commoner and understand the spatial dimensions of the activity in more depth.

Engaging with the spots at a 1:1 scale promotes a deep engagement with the site and commons the space in a more visible way to the original observed activity.

Each constructed observation is filmed from two perspectives. The first uses a cheststrapped gopro, focussing in on the action. The second is filmed from a spot hidden to other users of the space, for example from the window of a building that faces the square. This perspective focusses on the perception of the action.

Historic battle reenactment Reenactment - as defined by Forensic ArchitectureAccessing the guarded buildings in order to film the interventions became a key part of the project. Gaining the trust of those working around the square presented an opportunity to engage with more than just the users of the public space.

I contacted most of the tenants of the square, and recieved access from 4 people. Palantir and Fedro Gaudenzi responded to emails, whilst Sunrider Europe and the House of St Barnabas granted access upon me visiting in person.

Each constructed observation began with an spatial analysis of the exact spot and the activities taking place within it. At spot a, the stoop becomes a place of work. In the afternoon, delivery drivers were often seen sitting on the step awaiting an order. The stoop was an appropriate place to sit due to it’s proximity to

LISTENING TO MUSIC DRINKING SITTING SMOKING WORKING WAITING

Oxford Street, the comfort of it being raised, and the vacant building behind it meaning that the user would be undisturbed.

Also, the stoop both has views out but is also visually protected by the fence that sits alongside it.

To amplify the conditions decribed on the previous page, I set up a desk and office chair and worked on the stoop for an hour. This was both to understand what conditions would be needed to improve the environment for work and to illustrate that the stoop is no longer just the stoop of an empty building, but a valuable place of work to the users of Soho Square.

The films can be seen in full on the project’s website at RCA2023.com, but stills are inserted below.

Sou Foujimoto placed a toilet in a garden seemingly foregrounding an activity that is usually in a confined space. Similarly, intervention a brings the desk and chair into an open rather than confined space.

The Stroker sees Pilvi Takala gently stroke fellow employees in an office during a two

week residency and in doing so unnerves them. The nuances of movement demonstrate how people negotiate the dilemma of being mediated bodies under social pressure, and how such responses are controlled by the tacit conventions governing what is deemed to be ‘acceptable behaviour’.

Right: Toilet by Sou Foujimoto Below: The Stroker by Pilvi Takala

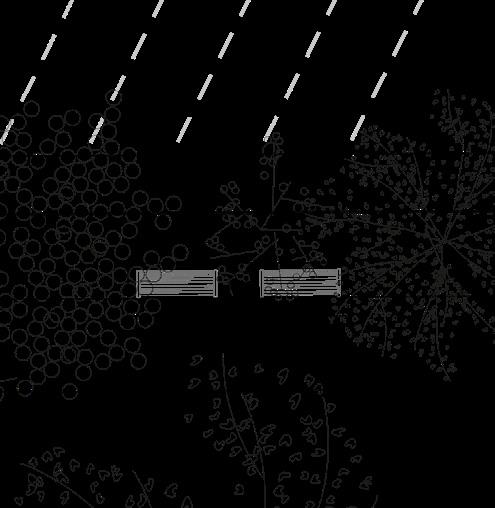

Between 11:30 and 13:30, the benches become a place for eating. During February and March, the benches were almost exclusively occupied by construction workers, working on the adjacent Crossrail station at Tottenham court road. Office dwellers seemingly stayed inside during these colder months.

The construction workers eat lunch together on the benches, and although the food they ate

was different, the users often brought sauces to share with one another. Ketchup, mayonnaise and brown sauce were often seen resting on the arms of the bench and used communally amongst themselves.

The greenery of the square offers a respite from the construction site, and benches offer a comfortable place to sit with space to rest and share their sauces.

To test how the activity can be facilitated, I fastened two wooden discs to each bench arm and brought sauces to use with my lunch. The wooden discs increased the amount of size available to rest the items atop.

These benches are a vital space for people to eat an uncommodified lunch in the open air, though their functionality is currently limited. The wooden discs facilitate the lunch ritual through a simple move.

+ WOODEN DISCS

+ CABLE TIE

PROPS USED: TIME FILMED: 17.05.23 13:12:31-13:48.41

+ KETCHUP

+ MAYONNAISE

+ PRET WRAP

Stills from Sauce Bench film

Once the grass in the square was relaid, and the weather got warmer, many users of the square could be seen napping on the grass. The square is the largest open space is Soho and one of the only outdoor places you can sleep undisturbed.

The grass is soft and allows views up to the trees during a nap, as well as the sun shining down dappled light through the leaves on the trees.

In this site activation, I inflated a bed covered with artificial grass and took a nap in the park. This intervention tests how the grass can become a more comfortable place to sleep and highlights the use of the grass as a bed.

The bed almost appears from out of the grass as it inflates, and all of the props are carried in and out of the film in one go, creating a DIY bedroom in the middle of the green space.

+ INFLATABLE BED

+ 12V BATTERY

PROPS USED: TIME FILMED: 07.05.23 11:19:31-13:57.31

+ INVERTER

+ 4X1 ROLL OF ARTICIAL GRASS

+ PILLOW WITH CASE MADE FROM ARTIFICIAL GRASS

Stills from Grass Bed filmTracy Emin’s ‘My Bed’ sees her bed and the objects left around it brought to a gallery and declared art. The idea for My Bed was inspired by a sexual yet depressive phase in the artist’s life when she had remained in bed for four days without eating or drinking anything but alcohol.

These private moments were foregrounded through their exhibition in the gallery. In a somewhat similar vein, when users of the square nap on the grass, a usually private moment is made public. The softness of the grass replicates the intimacy of a bedroom.

Image of Tracy Emin’s ‘My Bed’

Image of Tracy Emin’s ‘My Bed’

On certain parts of the fence surrounding the garden in Soho Square, bikes and motorbikes are locked to the fence. In the absence of sufficient bike stands, users appropriate the fence as a form of personal storage.

This primarily occurs on the south-eastern side of the square, where there are no bike locks seen in any direction and a high concentration of offices.

Often, the bike locks can be seen to be left overnight as regular users leave them there ready for use the next day, meaning the use of the fence as storage becomes a permanent fixture.

To test the limits of how the fence can function as a mode of domestic storage, I cycled up to the fence, and proceeded to lock everything I had one me to the fence using bike locks. The objects included my bike, my helmet, 3 bags, 2 coats, a jumper and a hair scrunchie.

By locking all of these items one by one the fence was no longer a form of enclosure and exclusion, but my personal storage facility. This intervention argues for the provision of places to leave objects whilst they are not in use.

+ BIKE

+ BIKE HELMET

PROPS USED: TIME FILMED: 03.03.23 09:05:31-09:20.08

+ GLOVES

+ 3 BAGS

+ COAT

+ UNDERCOAT

+ JUMPER

+ SCRUNCHIE

+ 9 BIKE LOCKS

Stills from Grass Bed filmIn Paris, another appropriation of railings has taken place on a large scale. The ‘love lock bridge’ is a a ritual that is practiced on the Pont Des Arts bridge in Paris. Couples inscribe their names on padlocks, lock it on the bridge and throw the keys into the river. The ritual is meant to symbolise love locked forever.

As of 2015, over a million locks has been placed since 2018, weighing approximately 45 tons. In 2015, the locks were cut off as there were structural concerns for the bridge, and the railing was replaced with thick bars through which a lock can not fit.

Image of Pont Des Arts, Paris

Image of Pont Des Arts, Paris

In this corner, users of Soho Square sit on this raised forecourt. The forecourt belongs to the now vacant 20th Century Fox building, and is adjacent to Frith Street which leads to central Soho. Not only is the building vacant, encouraging people to sit on the forecourt as they won’t be disturbed, but the spot is also located directly under a streetlight.

As it is well-lit, people gather at this spot after dark, and particularly in the darker months people can be seen using the raised step to look at their phones or read a book.

The main qualities attracting people to this spot are that it is well lit and raised creating a more comfortable place to sit.

To amplify these qualities, I brought 4 additional lights to create a bright spot and a foldable chair to rest on top of the raised forecourt with a warm woolen blanket to make the sittable area more comfortable and enhance it’s domestic qualities. I read in this spot for 40 minutes to test the appropriateness of these items in the public realm.

After the square closes, the perimeter fence takes on a peculiar social life. The park closes at 16:00, 17:00, 19:30 or 20:00 depending on the time of year and consistently, once the gates shut, people can be found spending time hanging out at it’s perimeter. Soho doesn’t have many open spaces, only

EATING DRINKING SITTING STANDING LITTERING WAITING CLEANING SMOKING

2 garden squares (this one and Golden Square) which are both shut at night. This means people who don’t or can’t access the bars but still want to be in Soho stand around the fence. This also is more a pleasant environment as there is a visual connection to the inaccessible nature behind the gates.

ledgetoholddrinks view

fenceprovidesspacetolean

raisedpavement

Through using the space around the perimeter of the park after closing, the narrow pavement and the parking bays essentially become an extension of the park during it’s inaccessible hours.

This intervention amplifies this phenomenon through the placement of an artificial grass blanket, which is attached to the fence using velcro grass loops. A picnic is staged in the space between the fence and the active road to understand the unexpected use of this space.

+ 2M X 4M

PROPS USED: TIME FILMED: 19.05.23

ARTIFICIAL ROLL OF GRASS WITH VELCRO LOOPS

+ PICNIC BLANKET

+ PICNIC BASKET

+ CRISPS

+ STRAWBERRIES

+ TANGERINE

+ FIZZY DRINK

+ CUP

19:00:11-19:42.08

Stills from Living Forecourt filmPortable Parks I-III was a series of performances and installations in the public space, where the artist created natural environments into unexpected urban locations like elevated freeways and by the sides of major roads in San Francisco.

The artist brought sod, palm trees, picnic tables, bales of straw, farm and domestic animals to create a new understanding and relationship with the space people share and inhabit.

The goal was to create temporary green environments for the public to use within the city.

Each site activation presents an agenda for public space as set by the commoners of Soho Square. A demands for places to work especially for casual workers, B argues for easy places to eat, C demands comfort in the public realm, D asks for well-lit spots after dark, E argues for public storage and F campaigns for more publically accessible spaces to stay open late. Through these interventions the parameters for how these agendas can be met are tested as well as drawing attention through the work

to the importance of common space to cater for varied needs. Soho Square is a key resource for it’s users, as shown through the plethora of acts of commoning present on the site.

By performing these interventions at a 1:1 scale, the unexpected scenarios provoke a conversation about who the city is currently being designed for.

The next book examines how these activations can be translated into provocative design proposals.

Book 5

Commoning Soho Square

Marnie Slotover

RCA ADS7

EATING

DRINKING

SITTING

LOCKING

WORKING

CHATTING

LISTENING TO MUSIC

PLAYING

EXERCISING

STANDING

LITTERING

WAITING

FEEDING

SLEEPING

VANDALISING

CLEANING

SMOKING

KISSING

Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation (1969) describes how empowered public institutions and officials deny power to citizens, and how levels of citizen agency, control, and power can be increased.

Commoning Soho Square can be read as a critique of the public consultation processes that currently dominate the engagement strategies within the architecture industry.

Arnstein places consultation within the ‘tokenism’ section of the ladder, whilst citizen

control’ sits at the top of the ladder.

This project, through the observation of urban commoning practices, intends to redistribute the power within the public realm, to those who actually use, and appropriate, its elements.

The provocative designs in book 5 are a nod towards what the city might look like if we designed around users rather than for order and profit.

“Citizen participation is a categorical term for citizen power. It is the redistribution of power that enables the have-not citizens, presently excluded from the political and economic processes, to be deliberately included in the future. It is the strategy by which the have-nots join in determining how information is shared, goals and policies are set, tax resources are allocated, programs are operated, and benefits like contracts and patronage are parceled out. In short, it is the means by which they can induce significant social reform which enables them to share in the benefits of the affluent society…. participation without redistribution of power is an empty and frustrating process for the powerless.”

CITIZEN POWER

CITIZEN CONTROL

DELEGATED POWER

PARTNERSHIP PLACATION

Stakeholders have the idea and set up the project

Goal created by a facilitator but resources and responsiblity given to citizens

Stakeholders have direct involvement in decision making

Stakeholders shape ideas, but final decision sits with facilitators

TOKENISM

CONSULTATION INFORMING EDUCATING MANIPULATING

Stakeholder views are sought but decisions are made by facilitators

Stakeholders are informed on decisions but no opportunity to contribute

Assumption that the stakeholders are passive recipients

The illusion of participations when actually power is denied

The stoop office constructed observation highlights the use of the northern stoop outside of 7 Soho Square as an office for casual workers. This speculative intervention proposes relocating the lesser used stoops from around the square (see demo plan for locations) to the

places that are most useful as informal work spaces. The new locations are on corners near different entry points to surrounding areas. The stoops are reconfigured in their geometries to create different heights of seating and places to rest objects.

This walkthrough animation shows a hybrid of a film where the stoop office constructed observation took place with the relocated stoops. The stoops surrounding the square were scanned then the meshes were edited

and placed into the film using motion tracking on Blender. The next two pages show a series of stills from the 15 second film. This format presents an immersive way to experience a space built around from of commoning.

view 1 from walkthrough animation

view 2 from walkthrough animation

view 1 from walkthrough animation

view 2 from walkthrough animation

view 3 from walkthrough animation

view 4 from walkthrough animation

view 3 from walkthrough animation

view 4 from walkthrough animation

The sauce bench constructed observation shows that workers local to Soho Square need places to eat and share food comfortable. This speculative intervention proposes reconfiguring the benches within Soho Square (and relocating those that interfere with the grass

reconfigurations) to have more raised platforms and to be more sociable. This facilitates the office lunch commoning that happens in Soho Square, presenting more places to share sauces and other lunch items.

Reconfigured bench locations

Reconfigured benches to aid commoning

Sauce bench constructed observation

Reconfigured bench locations

Reconfigured benches to aid commoning

Sauce bench constructed observation

view 1 from walkthrough animation

view 2 from walkthrough animation

view 1 from walkthrough animation

view 2 from walkthrough animation

view 3 from walkthrough animation

view 3 from walkthrough animation

The grass bed constructed observation demands for comfortable spaces to take naps outside in nature. This speculative intervention proposes adding a new topography to the existing grass to create comfortable bed like nooks especially designed for people to nap

with a view up to the canopy of the trees. The grass mounds are located beneath the biggest, tallest trees and also offer views up to the unobstructed sky.

Grass mound locations Grass mounds to aid commoning Grass bed constructed observation

view 1 from walkthrough animation

view 2 from walkthrough animation

view 1 from walkthrough animation

view 2 from walkthrough animation

view 3 from walkthrough animation

view 3 from walkthrough animation

The storage fence constructed observation presents the case for retaining parts of the fence. Although seen as a form of exclusion, the fence is useful to the users of Soho Square as it becomes a place of storage in the form of locked bikes. When doing a project about commoning, the assumption would be to remove the fence.

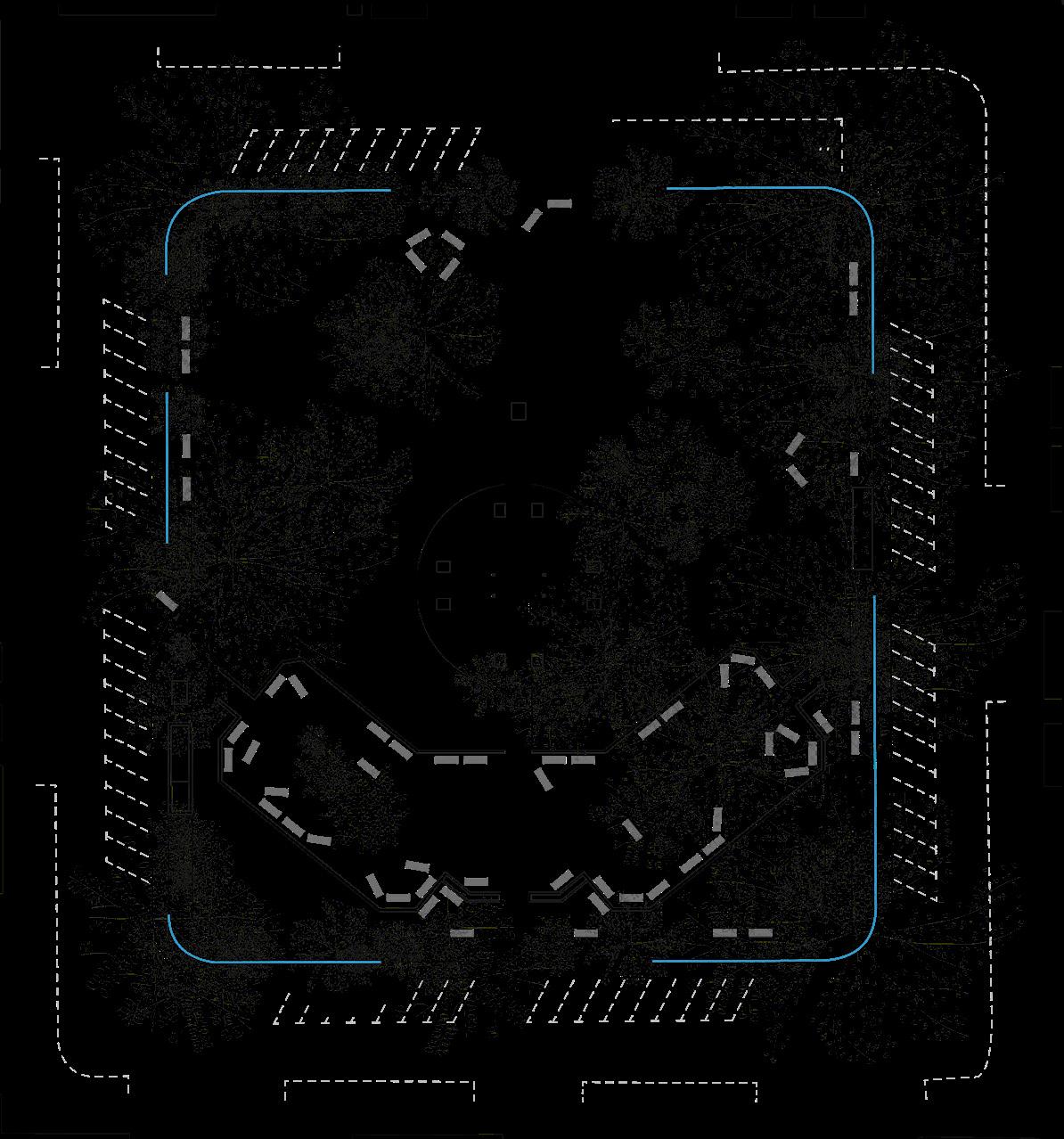

However, through observing acts of commoning, this counter logic becomes evident. Certain parts of the fence will be removed where there is sufficient bike storage, whilst the spots that are used as storage will be retained. The perforations in the fence will also allow for unobstructed access to the square at night.

Retained fence locations

Storage fence constructed observation Storage fence in use

Storage fence constructed observation Storage fence in use

The living forecourt constructed observation asks for well-lit spots to sit in after dark. This speculative intervention proposes adding spotlights to the existing street lights which point to the existing and proposed stoops. The stoop offices will double at the well-lit nooks that other users of the square can sit at after dark and feel safe and seen.

New spotlight locations

Living forecourt constructed observation

New spotlight locations

Living forecourt constructed observation

The park extension constructed observation campaigns for later opening hours for the park and also asks for park spaces in unconventional spaces. The speculative proposal shows the grass extending from the existing beds out of the park over the pavement and into the

road. Learning from the park extension, the park space takes over the road redistributing the power from the car to the pedestrian. This intervention presents new places for people to spend time after the park opening hours are finished.

view 1 from walkthrough animation

view 2 from walkthrough animation

view 1 from walkthrough animation

view 2 from walkthrough animation

view 3 from walkthrough animation

view 3 from walkthrough animation

Each proposed intervention uses the existing elements of Soho Square and subtly transforms them into something new, to facilitate the acts of commoning observed. This keeps the overarching appearance of the square the same but disrupts the order.

Upon looking initially, the animations don’t

appear out of sorts, but when investigating them closer the placements of the elements are unnerving. Currently, consultation leads to standardised results. How would the city look if we designed around the needs of its users, rather than for order?

In this book, a culmination of the Commoning Soho Square methodology is presented in the form of design proposals. The interventions are provocative and look to a speculative future where citizens have more agency over shared space. However, in order to reach a consensus,

the methodology would need to be scaled up. The observation stage should take place over a whole year, not just 24 hours and built interventions should zoom in to the scale of a paving stone.