adls.org.nz NEWS Dec 9, 2022 Issue 44 Inside ■ PROPERTY How negative equity impacts purchasers P10 ■ CONSTITUTION Attorney-General talks tough on ‘line calls’ P15 How Rob Harrison got a win for PETER ELLIS

LawNews is an official publication of Auckland District Law Society Inc. (ADLS).

Editor: Jenni McManus Publisher: ADLS

Editorial and contributor enquiries to: Jenni McManus 021 971 598

Jenni.Mcmanus@adls.org.nz

Reweti Kohere 022 882 2499 Reweti.Kohere@adls.org.nz

Advertising enquiries to: Darrell Denney 021 936 858 Darrell.Denney@adls.org.nz

All mail to: ADLS, Level 4, Chancery Chambers, 2 Chancery Street, Auckland 1010

PO Box 58, Shortland Street DX CP24001, Auckland 1140, adls.org.nz

LawNews is published weekly (with the exception of a small period over the Christmas holiday break) and is available free of charge to members of ADLS, and available by subscription to non-members for $140 (plus GST) per year. To subscribe, please email reception@adls.org.nz.

©COPYRIGHT and DISCLAIMER Material from this publication must not be reproduced in whole or part without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and, unless stated, may not reflect the opinions or views of ADLS or its members. Responsibility for such views and for the correctness of the information within their articles lies with the authors.

02 Contents

How the Peter Ellis case was won TIKANGA EVIDENCE JURISDICTION 03-05 Trust law: why the settlor’s objectives matter DEED SETTLOR TRUSTEES 06 Why smaller law firms struggle with AML/CFT compliance COMPLIANCE TRANSACTIONS COST 07-09

Grizelj / Getty Images Merry Christmas from LawNews This is our final issue of LawNews for 2022. ADLS and LawNews would like to thank all our members, readers, contributors and advertisers for their support during what has, for many, been an exceptionally challenging year. We wish you all a happy festive season and a relaxing holiday break. The first issue of LawNews for 2023 will be published on Friday 3 February. Photo: lisegagne / Getty Images FEATURED CPD 22-23 EVENTS 18-20

Cover: Daniel

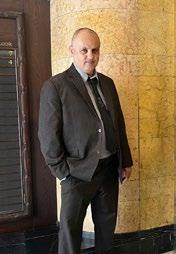

Rob Harrison: how the Peter Ellis case was won

Reweti Kohere

The ice caps melt, the planet heats up, living costs rise, and real wages stagnate. The middle class struggles, the poor barely survive, economies shrink and labour shortages hit businesses. Conspiracies flourish, tyrants wage war, democracy declines and a global pandemic persists. The list drags on. Hopelessness runs rife.

Except Rob Harrison doesn’t think so. His grandchildren are texting him about the Ukraine war, climate change and other worldwide catastrophes, he tells LawNews before offering some sage advice: “Don’t fall down into that despair. Look for the positives in things.”

The Blenheim-based barrister makes a good point, although it’s hard not to look at one of New Zealand’s most defining miscarriages of justice – a case Harrison has been involved in – and feel some sense of hopelessness. In life and in death, directly and from a distance, fate has linked Harrison and the late Peter Ellis, the former Christchurch crèche worker wrongfully convicted 30 years ago of sexual offences.

Right up until his death in September 2019, Ellis never wavered in maintaining his innocence. The Supreme Court two months ago ultimately upheld his third appeal. Evidence put before the jury in 1993 was incorrect or misleading, the court has ruled, and in some instances it shouldn’t have been admitted at all. Stepping back, the court found a miscarriage of justice had occurred. Ellis’ convictions were quashed.

The fight for justice was long. Were there ever any moments of despair? No, there weren’t, Harrison responds. “It’s an unusual question that you ask me. Why is that?”

Thirty years of history

In the lead-up to that question, we had traversed 30 years of history.

Admitted to the Bar in 1987, Harrison was well into his career when Ellis’ case came across his desk in late 1991 as a watching brief. Ellis had been suspended from his job at Christchurch Civic Childcare Centre. Harrison says it wasn’t clear why, although a suggestion of sexual offending lingered.

He kept an eye on developments.

By Christmas, the police had indicated there were no concerns. However, their investigation continued into early 1992, after which an allegation of sexual abuse was made for the first time.

Subsequent interviews were held with more than 100 crèche children. As the interviews progressed, some of the children who disclosed abuse by Ellis, implicated other people. And bizarre allegations started to surface, including being hurt with needles and burning paper, hung from the crèche roof in cages and taken through trapdoors.

Ellis was arrested on 30 March 1992, at which point Harrison, a category four lawyer qualified for the most serious offences, became formally involved as counsel. Given the number of complainants and the bare allegations contained in the interview transcripts, he recalls Ellis’ prospects initially looked bleak.

But the case turned around once discovery started painting a fuller picture of the background to the claims and once four of Ellis’ female co-workers were arrested in October 1992. “It started looking very, very positive because it was surreal to a certain extent, once you start seeing the entirety of the case,” Harrison says.

Eleven weeks of depositions were the high point of the defence’s optimism: every interview tape was played and parents and most of the main players were cross-examined, he says.

Getting the charges thrown out was starting to look

03 Dec 9, 2022 Issue 44 Continued on page 04

CRIMINAL LAW

It was one of those cases that had all the hallmarks of everything that could possibly go wrong and ultimately ended up with a decision of all things that could possibly go right

Despair is crawling off into the corner, rolling yourself into a ball, and sucking your thumb or whatever. I’ve never felt that

promising when the hearing ended in February 1993. However, the case got tougher as the trial neared. Charges against the four women were dismissed by Justice Neil Williamson on the grounds that their association with Ellis would prejudice their fair trial rights. And days before the trial, the judge ruled not all the interview tapes had to be presented to the jury – a ground that later formed part of Ellis’ 2019 appeal to the Supreme Court.

Still, Harrison didn’t walk into the trial thinking Ellis was doomed. “The case was more difficult but we still had some very powerful witnesses before us,” he says.

‘Despair just throws me’

Standing trial alone on 28 charges relating to 13 children, Ellis was convicted on 16 counts against seven complainants, acquitted on all charges relating to four complainants and discharged on three counts relating to the remaining two complainants. On 22 June 1993, he was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment. He was released from prison in February 1999.

Two appeals to the Court of Appeal, in 1994 and 1999, were largely unsuccessful (the 1994 appeal did result in three of Ellis’ convictions being set aside after one complainant recanted their evidence). Petitions to the Governor-General were submitted, one of which led to the second appeal, and another that led to a ministerial inquiry in 2000.

Former Chief Justice Sir Thomas Eichelbaum conducted that inquiry, eventually concluding the convictions were not unsafe. Two petitions to Parliament were also submitted and in 2005, the Justice and Electoral Select Committee declined to establish a royal commission of inquiry.

I had looked at Ellis’ case with a sense of despair. Had it ever seeped in, I ask Harrison? His puzzled, curious response – “It’s an unusual question that you ask me. Why is that?” – is so off-putting it takes me a moment to notice the upward inflection in his voice. Feebly, and perhaps too honestly, I fess up to my glass-half-empty outlook on life. A hearty chuckle travels down the phone line, followed by that quintessential antipodean turn of phrase, “Yeah, no.” It’s clear despair isn’t in Harrison’s vocabulary.

“We walked into trial thinking we had a really good chance, that we had good evidence. What we didn’t have was an appropriate expert. But, as events have subsequently shown, the Crown had an expert but not an appropriate one either,” he says. “So sorry, mate, despair just throws me. I like to think I never thought I was wandering around with despair written across my face.”

Much has happened in the past 30 years. The former Soviet Union was on the brink of formally breaking up when Christchurch police advised no allegations against Ellis had been made in December 1991. By the first appeal in 1994, South Africa had held its first election post-apartheid. Five years later, the Euro was the EU’s new common currency. The noughties had 9/11, the iPhone, the Great Recession and the first Black president of the United States. In the 2010s, the

first reality TV star commander-in-chief succeeded Barack Obama, Brexit happened and superhero movies surged at the box office. By the end of 2019, the first known human case of covid-19 was documented.

Having appeared in the 1994 appeal as second counsel behind first Nigel Hampton KC, then Graham Pankhurst KC, Harrison ceased being involved when the retainer was passed on to Judith Ablett-Kerr KC. Other than filing affidavits in support of the petitions, his contact with Ellis dwindled over the intervening years although he kept in touch with Ellis’ supporters, including Lynley Hood, whose book A City Possessed analysed his case. Harrison came back onboard in 2019 to lead the Supreme Court appeal.

In that time, the wheels of justice have turned ever-soslowly. Surely that has been dispiriting, but Harrison disagrees again. Despair has never taken root. Rather, he’s felt “extreme disappointment and extreme mistrust or anger” that what was “blindingly obvious” to most of the country could be “dismissed by legalese”, he says. Of course, difficult cases always arise in the criminal justice system. “My point about Peter’s case was that it shouldn’t have been difficult.”

Tikanga

Ellis knew he was on borrowed time as he attempted his third appeal; his advanced bladder cancer had become terminal in 2019. By mid-year, the Supreme Court granted him leave to appeal on the question of whether a miscarriage of justice had occurred. In September, as Harrison described it, Ellis “slipped away peacefully”

At common law, an appeal typically ends upon the appellant’s death if no application for continuance has been made. After it became clear Ellis would likely die before the November hearing date, he asked the court to keep his proceedings on foot. Ellis’ brother, as the executor of his estate, made a similar request, either in his own name as Ellis’ representative or in his late brother’s name.

As Justice Susan Glazebrook acknowledged in the continuance judgment, successful applications are rare because finality is a prized principle in the criminal justice system. Nonetheless, in November 2019, two months after Ellis’ death, the court heard argument on whether allowing the appeal was “in the interests of justice”, as per the test set down by the Supreme Court of Canada in R v Smith

The continuance decision might have ended on that narrow point of law but for the court asking whether tikanga Māori might govern the issue. A second continuance hearing was held in June 2020.

Harrison admits he hadn’t thought about the relevance of tikanga – something the Crown hadn’t contemplated either, based on the November 2019 hearing transcript.

But through the subsequent involvement of Kahui Legal’s Natalie Coates and Bankside Chambers barrister Kingi Snelgar,

04 Continued from page 03 Continued on page 05

He’s someone who deserves rich praise for his fortitude and resilience and the quiet and dignified way in which he did it

Peter Ellis

Continued from page 04 who drafted the bulk of the defence’s tikanga submissions, Harrison learned how much the “first law of Aotearoa and its values” can offer New Zealand’s Anglo common law.

While the Crown and the defence shared common ground in recognising tikanga is a source of New Zealand’s common law, the parties differed on how it applied to Ellis’ case.

The defence argued that everyone – Māori and non-Māori – has mana, and that death doesn’t close the door on a court redressing a “hara”, or wrong, especially one which judges have already “probed” by granting leave.

The Crown argued the court should “close the door” and revoke the grant of leave. Revocation would restore ea, or bring finality, to the case, which the grant of leave had disturbed. Te Hunga Rōia Māori, as intervener, argued “cautiously” that tikanga supported continuance.

An evolution

Having seen and worked with Ellis’ family over the past three years, Harrison has seen the wider impact of that hara. According to the panel of experts the parties relied on to determine what tikanga said about Ellis’ case, Māori custom dictates that disputes are not affected by the death of an accused or a complainant. Rather, the alleged wrong – either the sexual offending or the conviction of an innocent man, both of which have an impact on all parties’ mana – still lives.

The existence of a hara signifies an imbalanced world, the panel said. As far as it’s possible, reaching a state of “ea” is necessary to restore equilibrium for Ellis and the complainants, their whānau and loved ones. That responsibility is passed onto those still living; sometimes it’s inherited by each successive generation until it’s fulfilled.

The burden carries on, Harrison says. “I think everyone in New Zealand would understand that. But tikanga says ‘resolve it, it’s important’ and that, to my way of thinking, is a hugely significant point. If nothing else, that one issue just tells us how much there is possibly available to us with tikanga as we move forward.”

All five judges were unanimous in their jurisdiction to decide continuance applications in the event of an appellant’s death and where leave has already been granted. The court was unanimous that the interests of justice is the governing test and that tikanga has been and will continue to be a key thread in the weaving of New Zealand’s common law in relevant cases.

However, the court split on the result and the general place of tikanga in the law. The majority of Chief Justice Helen Winkelmann, Justice Glazebrook and Justice Joe Williams allowed the appeal to continue. While they were conscious of the high level of stress and public scrutiny the complainants and their whānau had already suffered for so long, the appeal grounds were strong and raised systemic issues, including that convictions should follow only from fair trials. Tikanga principles helped strengthen their view that the appeal should continue.

Justices Mark O’Regan and Terence Arnold wouldn’t have

allowed continuance as the interests of the complainants and their whānau outweighed all other factors. While they accepted death didn’t necessarily close the door, the proceeding should have been brought to an end by prohibiting continuance.

Harrison sees the decision as an overdue evolution of New Zealand’s legal system. “Believe me, I come from the gentle south. Many a person has raised the issue with me and I haven’t yet found any coherent argument that would dissuade me from the fact that the evolution of our law, and us as a people, is enhanced by this decision.”

Hallmarks

Three years ago, when Harrison returned to Ellis’ case, someone asked if it felt like a full-circle moment. The barrister, who describes himself as the man who lost Ellis’ case the first time, hoped history wouldn’t repeat “because full circle would be losing it again”.

He adds: “It was one of those cases that had all the hallmarks of everything that could possibly go wrong and ultimately ended up with a decision of all things that could possibly go right.”

Even while waiting for the Supreme Court’s judgment, Harrison never let himself hope for the outcome the defence had sought all along – history, after all, had repeatedly told him the system had failed. But he did let himself hope in one respect: the Supreme Court appeal was the first time he felt all matters had been fully aired before a judicial body. That was a fantastic result, he says.

I cheekily attempt my hypothesis again: not letting himself hope sounds like either giving into hopelessness or simply preparing yourself for all outcomes. His laugh may be a relief, but he doesn’t budge. “Despair is crawling off into the corner, rolling yourself into a ball and sucking your thumb or whatever. I’ve never felt that – you couldn’t do three years on the appeal from a position of despair,” he says. “Seriously, I’m starting to get worried about you, mate. This despair issue is concerning me. What’s been happening?”

I realise that very question typifies Harrison – a barrister who cares, who believes in the inherent good of people and who never gives in. And a colleague, Nick Chisnall KC, is grateful the profession has someone like Harrison among its ranks, an advocate who can stay the course.

“He’s someone who deserves rich praise for his fortitude and resilience and the quiet and dignified way in which he did it. He’s a leader of the Bar – there’s no doubt about it,” Chisnall says.

In the face of upheaval, people with fortitude and resilience come to the fore. People in the 20th century, like Harrison’s grandparents, lived through two world wars, an influenza epidemic and an economic depression. They hung in there, he says.

“If you’re starting to despair, then sit back and think about what exactly happened at Eden Park when those Black Ferns walked on to the pitch?” ■

05 Dec 9, 2022 Issue 44

In life and in death, directly and from a distance, fate has linked Harrison and the late Peter Ellis

subjective intentions change

It would seem heretical in New Zealand to allow a deed of trust to be amended by reference to a clear and unequivocal statement of a settlor’s objectives but this scenario will arise and the courts will need to resolve it

Anthony Grant

One of the surprises hidden in the Trusts Act 2019 was the requirement in ss 4(a) and 21 that a trust must be “administered in a way that is consistent with its … objectives”.

The Act does not say how trustees and the courts are to learn what a trust’s objectives are but a good starting place will be what the settlor says they are. This might be recorded in a memorandum of wishes or a letter or in an oral conversation.

The prominence that is given in the Act to the settlor’s objectives is a significant move away from the traditional understanding of how a trust is to be administered. For example, in Thomas & Hudson’s The Law of Trusts 2nd ed, the authors say: “The role of the settlor is simply that of creator. Once creation has taken place, then there is no evident role for the settlor in the operation of the trust… The settlor … drops from the picture absolutely and has no rights… to direct the trustees how to deal with the trust property…”

I regard this as a rather extreme assessment of the law on this topic which does not accord with other assessments but the law of trusts in New Zealand is now set to diverge from that path.

Where did ss 4(a) and 21 come from? So far as I can recall, they were not the subject of any specific discussion in the papers the Law Commission produced in the lead-up to the enactment of the Trusts Act 2019.

I approve of the focus the Act gives to a settlor’s objectives for a trust since trusts are not created in a vacuum. A trust is created by a person for a specific purpose or purposes and in general it seems appropriate that the trustees should try to fulfil the settlor’s reasonable expectations for the trust.

If the objectives of a trust are to be learnt by reference to the subjective intentions of a settlor, there will be difficulties for lawyers when they are asked to advise on the meaning and purposes of the trust as they will not usually have access to documents that record the objectives.

In the past, this has been a good reason for saying that a settlor’s subjective objectives should be ignored. But our law has now changed, with Parliament saying both trustees and judges must administer a trust “in a way that is consistent with

its objectives”.

Lawyers who advise on trusts must now make inquiries about a settlor’s objectives. This may give rise to further difficulty. What happens if a settlor wants a memorandum of wishes to remain confidential?

The courts will be required to answer this question.

When considering a settlor’s objectives for a trust, it must be recognised that the objectives are likely to change over time. As children are born, raised and leave home and as relationships begin and end, a settlor will inevitably have different objectives for a trust over the course of time, some of which may conflict with the terms of the trust.

In these circumstances, is a clearly expressed objective to prevail? Or is it to be overwhelmed by an outdated provision in a deed of trust that the settlor has overlooked?

This situation arose in Mackie Law Independent Trustee v Chaplow (2017) where a settlor said in a memorandum of wishes that a person was to be allowed to occupy a trust property following the settlor’s death.

But the settlor had overlooked the fact that the person was not recorded as a beneficiary of the trust. The deed of trust did not reflect the relationship change that had taken place within the family grouping.

A major criticism of letters of wishes is that, drafted without sufficient care, they can have the effect of amending a deed of

06

TRUST LAW

Can a settlor’s

the terms of a trust?

Continued

page 21

on

Anthony Grant

If the objectives of a trust are to be learnt by reference to the subjective intentions of a settlor, there will be difficulties for lawyers when they are asked to advise on the meaning and purposes of the trust

AML/CFT REVIEW

AML/CFT review: tinkering at the edges or a blueprint for real change?

When the cost is spread over like 100 lawyers, then it’s not even a really big impact on their bottom line. With smaller firms the impact is grossly disproportionate

Diana Clement

Small and medium-sized law firms, along with many other reporting entities, have long complained about the onerous compliance burden of anti-money laundering (AML) and combating the financing of terrorism (CFT) legislation.

But while changes are in the wind following the release last month of the Ministry of Justice’s Report on the review of the Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism Act 2009, along with 200 recommendations, they are unlikely to alleviate law firms’ key concerns.

Immediate changes include:

■ relaxing the requirement on businesses to verify the addresses of most customers;

■ doubling the time allowed for businesses to submit prescribed transactions reports (PTRs) from 10 to 20 days; and

■ exempting registered charities from AML obligations when providing small loans.

The review followed a critical report on New Zealand’s AML/CFT regime by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in April 2021.

Lloyd Kavanagh, a partner at MinterEllisonRuddWatts, says the 256-page MoJ report should be read by all reporting entities under the AML/CFT Act. Even law firms that currently fall outside the regime should read it to understand whether they may be brought within its scope, Kavanagh says.

Sam Short, a solicitor at Minters, has highlighted some of the key findings

They include:

■ not changing the purpose of the AML/CFT Act to include the prevention of money laundering and terrorism financing;

■ not expanding the regime’s captured activities, for example, to criminal defence lawyers;

■ increasing available penalties with a non-exhaustive list of aggravating and mitigating factors to help it be risk-based;

■ introducing the ability to restrict, suspend or cancel registration or licensing and for directors, senior managers, employees and/or agents to sometimes be held responsible;

■ amending the Amended Identity Verification Code of Practice 2013 to reflect the Digital Identity Trust Services Framework once it is enacted;

07 Dec 9, 2022 Issue 44

Continued

page 08

There is a lot of angst in the legal sector around the fact that they’re all going to have to undergo audits

on

Lloyd Kavanagh

Photo: AlexSava / Getty Images

■ removing both the need for address verification other than for enhanced customer due diligence (CDD) and the blanket requirement for enhanced CDD for trusts;

■ providing further clarity around the beneficial owner concept;

■ expanding the politically exposed person (PEP) requirement to include domestic PEPs to a lesser extent;

■ considering whether the Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) regime should have a less-strict time frame and/or differentiate between initial suspicions and having reasonable grounds to suspect;

■ whether the obligation to submit SARs should be reduced or removed where there would be little intelligence value to be gained; and

Kavanagh welcomed the changes to address verification, in particular. “The requirement [to verify addresses] never made sense in the first place and has proven a major challenge for many of us,” he says.

Tinkering at the edges

But views on the review are mixed. Nick Kearney, special counsel at Davenports Law, one of those smaller-to-medium-sized firms that might be disproportionately affected by the regime, accepts that New Zealand backs the AML/CFT regime but says it’s applied inconsistently across reporting entities.

“It can be very onerous for a small rural law firm in the middle of Waikato, which has essentially the same requirements as a multinational bank,” Kearney says. Streamlining of the Act and regulations to help with this type of anomaly is needed.

Removing the requirement to obtain current addresses from clients will be helpful, as will some of the other small changes. But the review feels like it’s tinkering at the edges. “It will do a little bit here, a little bit there, that might make things a bit easier.”

Some of the changes, however, will make little difference. “Removing or relaxing the timeframe in which to furnish a Prescribed Transaction Report is just ambulance-at-the-bottomof-the-cliff stuff. Instead of doing it within five days, you can do it within 10. That doesn’t really make much difference,” Kearney says.

“What I’d like to see from the review is the law and the regulations made a lot clearer. What I have trouble with at the moment is that the DIA [Department of Internal Affairs] publishes a whole bunch of guidelines around what lawyers should be doing.

“If you [say] I’m not sure about this or that, they just refer you to the website. The website has 25 or 30 documents on it that they expect you to trawl through, which is far too much. The guidelines should be stripped back and condensed into a [single] document and included in the Act itself.”

He adds that guidelines should never be the law but are treated by the DIA as such.

Costly beast

The AML/CFT regime is a costly beast, especially for smaller

firms. Davenports Law, which has the equivalent of 15 full-time lawyers, can, like most firms, on-charge AML onboarding to clients. Additional costs that can’t be passed onto clients add up to around $25,000 per year, Kearney says.

“We need to have an AML supervisor, separate from a compliance officer. So, we have to find someone and employ them. We’ve just rewritten our compliance program and that [cost] $3,500. We spend hours and hours on [AML/CFT] that we could spend on billing clients.”

Dimension GRC, a company that offers outsourced AML/CFT compliance to lawyers and other reporting entities, surveyed 590 lawyers recently, asking them among other things: “Do you have transparency around the amount of money you spend on AML compliance over a three-year period?”

“We have been talking to four- to eight-partner firms that have identified their cost of compliance over a three-year period to be in the vicinity of $45,000-plus,” says Dimension founder Jenine Colmore-Williams. “That’s alarming compared to the size of the firm. Bear in mind [that] compliance doesn’t differentiate you from your competitor.”

The legislation as it stands is sector-agnostic, she says, and doesn’t differentiate between a large bank and a small law firm.

“If you were to take a big firm like Dentons Kensington Swan, they have a dedicated compliance officer, and [team]. They don’t really have a big problem in managing their obligations. When the cost is spread over like 100 lawyers, then it’s not even a really big impact on their bottom line. With smaller firms the impact is grossly disproportionate,” Colmore-Williams says.

Some of the changes will ease the burden for small-to-

08 Continued on page 09

Continued from page 07

It can be very onerous for a small rural law firm in the middle of Waikato, which has essentially the same requirements as a multinational bank

Nick Kearney

Photo: spxChrome / Getty Images

medium sized businesses. “They addressed some key areas that had to be addressed. They’re putting a lot of support in for small businesses, although what that support looks like remains to be seen. The devil will be in the detail.”

Colmore-Williams says in her opinion the review was wellconstructed, but lawyers won’t be sitting back, throwing their hands in the air and saying, ‘thank God, there’s not a huge amount of change’. It’s not going to change their life significantly.”

Each individual law firm will have to wade through the 256page document to determine how it affects them, what the changes will be, when they will take place, how they are going to implement them and how to get their people to understand them, she says.

“It’s not going to be easy. One of the biggest problems that they’re facing in managing [AML/CFT] is translating the Act into their business model, and then pulling it into a set of documents that addresses the issues that they have to address.

“Every single [firm] will now have to update its risk assessment and AML program. And next year is also the second wave of audit for phase two. So, there is a lot of angst in the legal sector around the fact that they’re all going to have to undergo audits. That results in cost, business disruption and

stress,” says Colmore-Williams.

Small improvements from the review, such as easing the address verification and ranking trusts from low-risk to high-risk, will slightly reduce the friction of onboarding clients, she says. On the other hand, increased compliance around the conveyancing process will impact lawyers.

Law firms will also face a range of fines for non-compliance, instead of simply being told they are non-compliant, as is the case now, says Dimension GRC’s global head of governance, risk and compliance, Phil Sarsfield.

Sarsfield and Colmore-Williams say out-sourcing takes the obligations off law firms’ hands and reduces costs by 50% to 75%. “We manage the risk assessment, and we manage all the program updates. We keep them up-to-date with training and the registers and all the little things that just take time,” she says.

Some of the changes are expected to be made quickly with changes to regulations over the coming months, says Short. However, the “progressing” of recommendations could go on for a long time, depending on whether they need legislative changes, regulatory changes, a code of practice or changes in supervisory guidance or operational practices, he says.

He expects the ministry to move in several different tranches. Further consultation and exploration of options will be needed before the ultimate shape of some of the changes becomes clear. ■

The high cost of AML compliance for smaller law firms

Jenni McManus

A survey of small-to-medium sized law firms about their AML/CFT compliance reveals that most respondents are struggling with the cost.

Among the 60 respondent firms, AML annual compliance costs (excluding audit fees) ranged from $36,000 for those in the one to three-partner category to more than $100,000 for some with between four and eight partners.

The survey, conducted by Dimension GRC – a firm that offers a onestop-shop AML/CFT compliance service for lawyers based around a limited partnership model and proprietary software – reveals respondents were also concerned about maintaining their risk assessment and AML programs. Other worries were subject-matter expertise, understanding the risk a customer might pose to their firms, and record-keeping.

Most pain is being felt by small (one to three partners) to medium-sized law firms (four to eight partners), says Dimension founder, Jenine ColmoreWilliams. Of the 60 respondents, none had returned a fully compliant audit and 75% have another audit due next year.

The average time spent onboarding was 30 minutes for low-risk clients and more than two hours for complex entities. Only 35% thought they had embedded a risk-based approach; 52% believed they needed to lift their game and 23% said they did not know what a risk-based approach meant.

Colmore-Williams says in some cases lawyers are charging AML-related services (cost and time) for non-captured activities while in others might be overcharging for their AML services in the form of inflated disbursements.

In one case, she says, a lawyer wanted to charge $600 to verify the identities and addresses of six individuals in a local community trust. But because the transaction was a simple building lease between the trust and a business and the lawyer wasn’t handling money or providing any captured services, there was no obligation within the AML/CFT legislation to certify the identities and addresses of the individuals involved in the trust.

“This is an issue we come across frequently,” Colmore-Williams says, “and though it is more pronounced in accountants, there are still lawyers out there who take a view and decide to AML-check every matter due to a misunderstanding of the application of the AML/CFT Act.

“The question to be asked is where the lawyer sits from an ethical perspective when they are charging disbursements and time costs to facilitate services that are not required. Where we have advisory clients who wish to take a blanket approach, we are respectfully suggesting that they include in their engagement letter advice about their individual policy of AML/CFT-checking everybody regardless of the matter-type.”

She says there is no argument that verification of clients and entities and ultimate beneficial ownership, including ID and address verification, is the cornerstone of the client due diligence process.

“However, with so many law firms not passing audits, it is clear there is a lack of focus when it comes to completing a risk assessment on the nature, size and complexity of the client or matter as a whole.”

Colmore-Williams says her firm’s managed service AML-compliance model is up to 80% cheaper than running the program internally. ■

09 Dec 9, 2022 Issue 44 Continued

page 08

from

Jenine Colmore-Williams

How to deal with vendor negative equity and the risk to purchasers’ deposits

Joanna Pidgeon

For some years the property market has been rising and the issue of vendor negative equity has not been a key concern. But with property prices falling and some vendors having purchased at the peak of the market, the sale price after paying the real estate agent’s commission may be less than the debt on the property.

A conscientious vendor in this situation would make the contract conditional upon obtaining mortgagee approval to the sale. Some vendors however are not so conscientious.

The rules

Deposits are typically 10% of the purchase price and are usually paid to the real estate agent. Under clause 2.4 of the ADLS/REINZ 11th Edition 2022(2) Agreement, the deposit is to be held by the recipient as stakeholder until:

■ the requisition procedure under clause 6 is completed without cancellation;

■ any conditions are fulfilled or waived;

■ pre-settlement and additional disclosure is completed for unit title properties;

■ the agreement is cancelled pursuant to clause 6.2(3)(c) (requisition clause) or avoided pursuant to clause 9.10(5) (return of deposit for cancellation due to non-fulfilment of condition or waiver of nonfulfilment); and

■ s 151(2) of the Unit Titles Act 2010 for unit title properties has been completed and the agreement has been cancelled by the purchaser or the purchaser has elected not to cancel by notice or

has completed settlement of the purchase.

Pursuant to s 123(1) of the Real Estate Agents Act 2008 (REA), when the deposit is received by a real estate agent it is to be held by the agent for 10 working days from the date of receipt unless under s 123(2) of the REA the court orders or the parties agree for the deposit to be released early.

This stems from a purchaser’s ability to requisition the title within 10 working days of the agreement signed under clause 6.2 of the agreement.

Purchasers are often chased to authorise the release of the deposit early to enable a vendor to use the net deposit balance to pay the deposit on their subsequent purchase.

Section 123(3) of the REA requires agents to continue to hold the deposit if they receive written notice from a party to the transaction of any requisitions or objections in respect of the title to any land affected by the transaction. The deposit may not be released except in accordance with a court order or an authority signed by all the parties to the transaction.

Losing the deposit

There has been a disturbing trend in some agreements with additional clauses inserted mandating agreement for the immediate release of the deposit on payment in some “unconditional” agreements and particularly in some auction

agreements.

Agents are keen to receive their commission and vendors want their deposits to be released so they may use the net balance to fund the deposit on their next purchase.

While the deposit is usually released on an agreement becoming unconditional, if the vendor does not fulfil its obligations on settlement –such as being able to convey title with a discharge of mortgage – the purchaser on cancellation of the agreement is entitled to a full refund of the deposit.

However, if the agent has taken their commission from the deposit and the balance released to a possibly insolvent vendor and the vendor is unable to discharge their mortgage, the purchaser is faced with issuing court action for the return of the full deposit.

This may be fruitless if the vendor is in a negative equity situation. If the vendor is pushed to bankruptcy, the mortgagee as a secured party on the land will receive the net sale proceeds of the property, with the real estate agent having no obligation to disgorge their commission.

With high levels of borrowing at increasing interest rates and property prices falling, there have been more situations where purchasers have lost their deposit as the deposit has been released, the agent has taken their commission and the vendor the balance, but the

10

PROPERTY LAW

If you are asked to authorise the early release of the deposit, get instructions from your client and explain the risk if the vendor can’t transfer title on settlement

Continued on page 11

A conscientious vendor in this situation would make the contract conditional upon obtaining mortgagee approval to the sale

vendor has been unable to transfer title to the purchaser due to negative equity and the purchaser has lost their deposit.

Rethinking the risk

Should there be a rethink of risk under sale and purchase agreements? And should the deposit be held by the agent/vendor’s solicitor in trust pending the vendor being able to transfer clear title?

As set out above in the agreement, the deposit is held by the stakeholder until the agreement is unconditional or cancelled, right to requisition has passed and disclosure obligations have been complied with for unit title properties.

If the sale is off the plan, agreements usually provide for the deposit to be held in the lawyer’s trust account as stakeholder pending issue of title, practical completion and the issue of the code compliance certificate, but sometimes until settlement.

This would protect purchasers until settlement. However, sales and purchases are often in a chain and vendors often want to use the balance of deposit to help fund their deposit on a purchase.

Protecting the purchaser

What should a purchaser’s lawyer do when considering the vulnerability of the purchaser’s deposit?

The purchaser should consider requiring the deposit to be held by a stakeholder until settlement in these situations: if the vendor is in financial difficulty; where a vendor is not yet the owner of the land; and if the vendor is building on the land.

However, purchasers’ lawyers don’t always have the opportunity to advise on conditions.

If you are asked to authorise the early release of the deposit, get instructions from your client and explain the risk if the vendor can’t transfer title on settlement.

Under clause 3.8(2) of the agreement, the purchaser has the right to the transfer of title.

Requisition of title is different from matters going to the process of conveying title to the purchaser. A mortgage is not a defect in title subject to requisition under clause 6 of the agreement. The purchaser may raise matters of conveyance up until the settlement date, and the vendor must comply or be in breach.

If you are acting for a purchaser and have a concern as to whether the vendor can convey clear title on settlement, you should consider raising an issue or objection as to conveyance (this is not a requisition as to title under clause 4) and ask for evidence as to the vendor’s ability to convey title on settlement.

The vendor’s lawyer should be able to satisfy this objection by providing bank evidence as to the amount required to be repaid on settlement and demonstrating that there will be sufficient funds to repay.

If this is not forthcoming, a purchaser’s lawyer might consider raising an objection with the real estate agent under s 123(3) of the REA so the deposit is held until settlement. ■

Joanna Pidgeon is a director of Pidgeon Judd and convenor of the ADLS Documents and Precedents Committee ■

HUMAN RIGHTS REVIEW TRIBUNAL

TARAIPIUNARA MANA TANGATA DEPUTY CHAIRPERSON (Auckland or Wellington)

Applications are invited from persons wishing to be considered for appointment as a full-time Deputy Chairperson of the Human Rights Review Tribunal based in Auckland or Wellington.

The Human Rights Review Tribunal hears and determines proceedings lodged pursuant to the Human Rights Act 1993 (the Act), the Privacy Act 2020 and the Health and Disability Commissioner Act 1994 after complaints have first been dealt with by the Human Rights Commission, the Privacy Commissioner and the Health and Disability Commissioner pursuant to their respective Acts. The principal matters considered by the Tribunal concern privacy issues, human rights, discrimination and health and disability issues. The Tribunal has jurisdiction to award damages of up to $350,000 and to declare an enactment inconsistent with the right to freedom from discrimination as affirmed by the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990.

The Act provides that for any particular case the Tribunal must comprise:

• the Chairperson and/or a Deputy Chairperson

• two other persons appointed by the Chairperson for the purposes of each hearing from the Panel maintained by the Minister of Justice under section 101 of the Act.

Further details and an application pack are available from the Ministry of Justice website here

The closing date for applications is 20 December 2022.

11 Dec 9, 2022 Issue 44 Continued from page 10

protections

The sixth Labour government’s vaccine mandates drove a wedge into the Prime Minister’s “team of five million”, breaking and splintering the extraordinary level of social cohesion engendered by the global pandemic

Chris Trotter

How far back should we go for the answers? To 1932? Or 1952? Too far? What about 1982? Closer? Very well, let us begin our investigation in 2019.

Let’s begin in the hours, days and weeks following the Christchurch terror attack because it was there, amidst all the shock and horror, that the idea began to grow that it was time for the Left to step up, that the moment had come for progressives to show they could take a hard line with as much determination as conservatives.

March 2019 was when Jacinda Ardern and her Labour-NZ First government made the momentous decision to harness the power of the New Zealand state to the righteous wrath of its leaders and to show the world how progressives can fight.

The first targets, obvious and with the overwhelming backing of the population, were the thousands of military-style semiautomatic rifles in the hands of New Zealanders who really could not supply their fellow citizens with a good reason for possessing them. Brenton Tarrant had shown New Zealand what MSSAs were made to do. They have no other purpose. Ban them.

And how the world applauded New Zealand’s young Prime Minister. Americans, in particular, cheered Jacinda Ardern to the echo: to live in a country where such things were possible; to have a leader willing to act and a legislature able to take the obvious, necessary steps to protect its people. How fortunate was New Zealand!

Protection: it’s a slippery concept, as wont to lead us into darkness as guide us to the light. Politicians who want to protect us can be a blessing but they can also be a curse, such as when it is proposed to extend the state’s protection beyond banning the all-too-real firearms that deal out death to include the spoken and written words of those whose ideas motivate the men in possession of these military-style weapons.

It is an age-old question: who is the more powerful? The man with the gun? Or the man who manufactures his bullets?

There is no shortage on the Left of those who would characterise ideas as a form of ammunition. There are plenty who will aver that words can cause as much harm as bullets. If you would ban MSSAs, Prime Minister Ardern, then you must also ban “hate speech”. When the call for this form of protection comes from the community against whom the Christchurch terror

attacks were directed, it is difficult to refuse.

Protection: it is hard enough keeping human beings from one another’s throats. So, what do you do when Mother Nature herself gate-crashes the party with a killer virus? Jacinda Ardern found herself, once again, without a rule-book to guide her. Pressed on every side by every conceivable interest, she reached out for the only hand without skin in the game – the hand of science. But, if science were to be of any practical assistance, then it also needed protection: the protection of the law.

Legal protection

There was a time when laws bestowing draconian powers upon the state waited on the statute books for such a year as 2020. The Public Safety Conservation Act of 1932. The Economic Stabilisation Act of 1952. Acts of Parliament passed in recognition of the fact that life isn’t always a bowl of cherries and that there are moments in history when action is an urgent necessity and debate an expensive luxury. But Jacinda Ardern faced her covid-19 moment without them.

Both Acts had been triumphantly repealed by the fourth Labour government which saw them only through the eyes of their historical victims – working people and their unions. Wasn’t it National’s Sid Holland who smashed the watersiders’ union with the Public Safety Conservation Act in 1951? Wasn’t it Rob Muldoon who used the Economic Stabilisation Act to tie the New Zealand economy up in regulatory knots between 1982 and 1984?

In the absence of these fearsome legal levers, the Prime Minister and her government were forced to improvise – not always coherently and not always successfully but needs must when the devil, and a potentially deadly virus, drives. Wasn’t it Cicero who declared Salus populi suprema lex! (The safety of the people shall be the highest law!) Two thousand years on, the people of New Zealand rewarded Jacinda’s conservation of public safety with 50% of the popular vote. Vox populi, vox Dei

Protection: when does it cease to be a good thing? The sixth Labour government is in the process of answering that question for us. As best as we can make out, less than a year from the next general election, a government’s protection ceases to be a good thing when it is offered to some, but withheld from others.

12 Continued on page 13

POLITICS/OPINION

Under Jacinda Ardern’s

Protection has been the making of Jacinda Ardern’s government but may yet prove to be the breaking of it

The sixth Labour government’s vaccine mandates drove a wedge into the Prime Minister’s “team of five million”, breaking and splintering the extraordinary level of social cohesion engendered by the global pandemic. It was the rancour arising from the vaccine mandates that led to the occupation of Parliament grounds – a protest culminating in the worst episode of political violence since the 1981 Springbok tour.

Protection for some, but not for others. Protection of some, at the expense of others. Neither the Prime Minister nor her party seemed able to grasp that her own, and Labour’s, political success was born out of events which drew the country together – as in the huge “they are us” rallies that followed the Christchurch attacks or in the generous camaraderie of the initial covid lockdowns.

Dividing the nation into the vaccinated and the unvaccinated proved inimical to unity. The legal mechanisms designed to share the governance of Aotearoa-New Zealand between Tangata Whenua and Tangata Tiriti (Māori and non-Māori) contain the seeds of enduring strife.

Labour, and that part of the Left which identifies with its ambitions, shows every sign of having drunk too deeply from the cup of political protection. The problem with the Left’s current obsession with protecting particular groups from the ravages of inequity is that in rescuing one group from victimisation, it risks making victims of another.

Collateral damage

Nowhere has this zero-sum gamesmanship been more in evidence than in the passage of the Three Waters legislation through Parliament. That Labour and the Greens were willing to traduce New Zealand’s unwritten constitution in the name of protecting the nation’s waters from privatisation offers alarming proof of just how blinkered they have become.

Progressives are indeed showing the world how they fight: without regard for the serious collateral damage inflicted by their heedless and unchallengeable rectitude.

Offering Māori and Pakeha the protection of equality – as in the Treaty of Waitangi – laid down a solid foundation for national unity. Promising equity, especially in a political atmosphere thick with recrimination and blame, is a recipe for division and conflict.

Protection: it has been the making of Jacinda Ardern’s government but may yet prove to be the breaking of it. In the face of tragedy and danger, the New Zealand Left was determined to act boldly in the defence of human safety. By doing so, the progressives in and around this Labour government earned the plaudits of the world, not only for protecting their citizens’ lives but also for throwing their arms around their most cherished values.

Banning MSSAs was a good thing, as were the laws protecting public safety during covid. Threatening New Zealanders’ freedom of expression, however, and offering special legal protections on the basis of vaccination status and ethnicity smacks alarmingly of authoritarianism and racism.

If these radical legal initiatives are intended to show how progressives can fight, then the protection Labour and the Left are most in need of is from themselves. ■

AssociateMcElroys is looking to recruit a talented associate with 4+ years’ PQE in insurance or civil litigation to join our close-knit team.

About us

McElroys are experts in insurance law, maritime litigation and legal representation helping the New Zealand business community navigate risk and resolve complex litigation.

We have been solving problems in insurance and maritime law for over 25 years. In that time we’ve been called upon by both global and national clients to help them navigate risk and resolve a broad range of litigation challenges from leaky buildings to employment and statutory prosecutions.

We are proud of our track record, but actually McElroys’ success lies in the values our founding partners established when the firm first opened its doors for business. Attention to detail, going beyond what is required, keeping astride of new approaches and setting new standards have all contributed to a purposeful culture that sets itself apart by consistently delivering results that count.

The role

You will work closely with our partners in our civil litigation team, with an opportunity to develop client relationships and hone your advocacy skills.

You will be managing civil and insurance disputes, including claims against professionals and directors, marine insurance and product and public liability claims.

Attributes we are looking for

• Collaborative – the ability to work as part of a team and value the contributions of each other

• Better – to continually strive to reach the highest standard and go beyond what is required

• Expertise – to constantly challenge your understanding and deepen your knowledge

• Straightforward – be clear, accurate and direct in ensuring the right course of action is taken

If you wish to apply for this position, please email paul.sullivan@mcelroys.co.nz

Applications should include a covering letter detailing relevant experience, CV and academic transcripts.

13 Dec 9, 2022 Issue 44

Continued from page 12

Chris Trotter is a political commentator of more than 30 years’ experience and is the author of the Bowalley Road blog ■

Meet Stephanie Grieve KC

Becoming a King’s Counsel has always been one of Stephanie Grieve’s aspirations. Yet upon hearing she had taken silk, Grieve says she was still “overwhelmed and honoured”.

The new KC got her start as a summer clerk for Russell McVeagh after graduating from Otago University in 1997. Later that year, she moved to Wellington where, after completing Profs, she worked as a junior barrister. Grieve was admitted to the Bar in 1997.

Overseas work experience included working at a French law firm in the defence team in a matter before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia; as part of a legal compliance team for an investment bank in London; and as legal counsel for a cable TV company in Amsterdam.

Grieve returned to Dunedin in 2002, joining Anderson Lloyd. She was made partner in 2005 and moved to Christchurch. In 2011, she joined Duncan Cotterill as a partner before moving to the independent Bar in 2018.

Grieve has represented a group of Canterbury homeowners as intervener in the Ross v Southern Response Earthquake Services class action. She has been appointed counsel assisting in coronial inquests and was engaged to conduct an independent inquiry into Gloriavale Christian community.

The interview has been edited for clarity.

LawNews: How did you react on hearing you had been appointed as King’s Counsel?

Grieve: It’s a huge privilege. Having been appointed, I’m fully aware of the shoes that I’ve got to fill in terms of the advocates that have come before. You hope to, I suppose, be able to make a contribution. I see it as a role I will be growing into and hopefully setting an example for others and making a contribution to the community and the courts.

LawNews: Should we retain the title of King’s Counsel or revert to “Senior Counsel”?

Grieve: I think we should retain it as there is something in the tradition. It reflects the English system which our system has derived from.

LawNews: Which significant matter that you’ve been involved in over the last three years stands out the most and why?

Grieve: Because I’m involved in quite a variety of work, there have been a number. I’ve been involved in trust and estate litigation, disciplinary matters and earthquakerelated class action, coronial matters and an inquiry as well. There are some criminal cases I am involved in. There’s probably not one that stands out for me. I suppose I have sought to undertake a variety of work since I’ve been at the Bar, with the goal of improving my advocacy rather than focusing on a particular area of practice.

I see [advocacy] almost like a methodology. Once you know how to run a case and apply that methodology, you can find out whatever you need to find out about the area of law. That’s not to say you shouldn’t specialise, but it’s almost how you approach the case in terms of understanding the human dynamics first because, as we know, that underlies a lot of litigation – what is the story that has to be told and how am I going to tell it in a way that’s going to be compelling for whoever is making the decision? That’s why I enjoy the variety because you learn something about a different area of the world each time. No case is the same.

LawNews: How can barristers continue to improve access to justice?

Grieve: We’re critical to that issue because we’ve had the privilege of being trained as lawyers, then understanding how the system works and everything that comes with that. I see that as really important to then apply it to assist those who might struggle to make their way through that labyrinthine system or lack the resources to do so. We have to be accessible, we have to be able to understand what it’s like at the coalface for people who don’t have the privileges we’ve had. We play an important role and should be giving back to the communities that have lifted us up. ■

14

Reweti Kohere

PEOPLE

Once you know how to run a case and apply that methodology, you can find out whatever you need to find out about the area of law

Stephanie Grieve KC

Attorney-General David Parker talks tough on the separation of powers

Covid wind-down

Since last Friday’s breakfast, the government has announced a royal commission of inquiry into its covid-19 response, set to start early February 2023 and concluding in mid-2024.

Reweti Kohere

Attorney-General David Parker has warned that Parliament will disregard senior court orders declaring legislation inconsistent with fundamental human rights legislation if judges were to go “mad” in deciding every margin-call error rather than focusing on the most serious of breaches.

The courts and Parliament show mutual respect for each other’s respective roles and are aware of the dangers of encroachment, Parker says. But, in addressing judges and lawyers at the annual ADLS breakfast in Auckland last week, he said Parliament would put declarations of inconsistency “in the dustbin very easily” if the courts found alleged inconsistencies everywhere.

Parliament recently amended the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 and the Human Rights Act 1993 to include a process by which the House of Representatives and the executive can respond to declarations of inconsistency.

The “halfway house” measure would help improve the “comity” that the courts and Parliament shared, while ensuring Parliament remained supreme, “because, in the end, it’s elected politicians that should be making some of these line calls…rather than unelected judges”, Parker said.

Parliament always ran the risk of running roughshod over fundamental human rights, especially in the absence of an upper house, a judiciary empowered to strike down legislation or other checks and balances. While it didn’t happen that often, Parker said the legislature did contravene the Bill of Rights Act in some circumstances.

The senior courts for some years had been conscious that declarations of inconsistency might cause friction as the orders would essentially serve as criticism, given they lacked remedial effect. That’s partly why the government, with cross-party support, passed the New Zealand Bill of Rights (Declarations of

Inconsistency) Amendment Act 2020, Parker said.

The utility of that statutory power, however, depended on how rare the issue was. The attorneygeneral cautioned there was a risk of erosion if the courts misused the remedy.

Overlay of democracy

Parker also spoke about the government’s “enormous” legislative work to reform the outdated Resource Management Act 1991.

Thirty years after it was first passed, the RMA was replete with core failures. “It takes too long, it costs too much, it has not adequately protected the environment and neither has it enabled development, including housing,” he said.

The government in February 2021 announced the RMA would be repealed and replaced with three new statutes: the Spatial Planning Act (SPA), the Natural and Built Environment Act (NBA), and the Climate Adaptation Act (CAA). The first two Acts are with the Environment Select Committee while the CA Bill’s introduction is expected in 2023.

Instead of a co-governance model, a “participatory” model has been proposed by the government for upholding and protecting Māori rights. It’s envisaged iwi will have at least two representatives on regional planning committees charged with developing spatial strategies for each region.

Parker said Te Tiriti issues were more complex under the RMA than in most other spheres of law. While central government was delegating its law-making powers over planning laws to local government bodies, as per article one of the treaty, Māori control of their interests, including in land, fisheries and forests, are protected under article two by the participatory model. “And then article three will be to move together as one people, [which] is relevant particularly given the overlay of democracy that has developed since the treaty was signed.”

It follows a recent paper on New Zealand’s legal framework for emergencies, written by Auckland University public law professor Janet McLean KC, which concluded the country should act on its recent experience “while it is still fresh”. One of McLean’s key recommendations is conferring on political officials, rather than public servants, powers to make orders over parts of or the whole country under the Health Act.

Parker said Parliament could theoretically legislate an Act containing all the emergency powers that the executive would need to respond to any given emergency. But he didn’t favour such an approach as it would require accounting for all eventualities. “That’s not to say we couldn’t have some principles enshrined, like the fact you should never override the Bill of Rights Act,” he said.

Parliament recently wound-down numerous extraordinary powers under the Covid-19 Public Health Response Act 2020, a statute that formed the legal basis for many of the restrictions New Zealanders lived under during the past three years. While the Act has been extended to enable continued management of covid-19, it has been significantly narrowed to safeguard the country against new waves or variants.

Three years ago, Parker was tasked with formulating a legislative response to the pandemic – a policy role the ministerial office usually lacks. A cross-agency team of lawyers helped write a Bill that contained “necessary” and “wise” protections, including an explicit commitment not to do anything that would override the Bill of Rights Act and to leave open the door for judicial review challenges “as we ought to have”, he said.

“We had good advice from the courts on the way through. By and large, the actions of the executive were upheld. We had the occasional loss at the margin, which was proper. And we obviously learned from that as we went through.” ■

See page 18 for photos from the event ■

15 Dec 9, 2022 Issue 44

ADLS EVENT/CONSTITUTIONAL LAW

It’s elected politicians that should be making some of these line calls rather than unelected judges

Andrew Lensen & Marcin Betkier

The rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) has led to its deployment in courtrooms overseas. In China, robot judges decide on small claim cases, while in some Malaysian courts AI has been used to recommend sentences for offences such as drug possession

Is it time New Zealand considers AI in its own judicial system?

Intuitively, we do not want to be judged by a computer. And there are good reasons for our reluctance, with valid concerns about the potential for bias and discrimination. But does this mean we should be afraid of any and all use of AI in the courts?

Intuitively, we do not want to be judged by a computer AI machines are already used to predict some criminal behaviour, such as financial fraud

In our current system, a judge sentences a defendant once he or she has been found guilty. Society trusts judges to hand down fair sentences based on their knowledge and experience.

But sentencing is a task AI may be able to perform instead. After all, AI machines are already used to predict some criminal behaviour, such as financial fraud. Before considering the role of AI in the court room, then, we need a clear understanding of what it actually is.

AI simply refers to a machine behaving in a way that humans identify as “intelligent”. Most modern AI is machine learning, where a computer algorithm learns the patterns within a set of data. For example, a machine-learning algorithm could learn the patterns in a database of houses on TradeMe in order to predict house prices.

So, could AI sentencing be a feasible option in New Zealand’s courts? What might it look like? Or could AI at least assist judges in the sentencing process?

Inconsistency in the courts

In New Zealand, judges must weigh several mitigating and aggravating variables before deciding on a sentence for a convicted criminal. Each judge uses their discretion in deciding the outcome of a case. At the same time, judges must strive for consistency across the judicial system.

Consistency means similar offences should receive similar penalties in different courts with different judges. To enhance consistency, the higher level courts have prepared guideline judgments that judges refer to during sentencing.

But discretion works the opposite way. In our current system, judges should be free to individualise the sentence after a complete evaluation of the case.

Judges need to factor in individual circumstances, societal norms, the human condition and the sense of justice. They can use their experience and sense of humanity, make moral decisions and even sometimes change the law.

In short, there is a “desirable inconsistency” that we cannot currently expect from a computer. But there may also be some “undesirable inconsistency”, such as bias or even extraneous factors like hunger. Research has shown that in some Israeli courts, the percentage of favourable decisions drops to nearly zero before lunch

AI’s potential role

This is where AI may have a role in sentencing decisions. We set up a machine learning algorithm and trained it using 302 New Zealand assault cases, with sentences between zero and 14.5 years of imprisonment.

Based on this data, the algorithm built a model that can take a new case and predict the length of a sentence.

The beauty of the algorithm we used is that the model can explain why it made certain predictions. Our algorithm quantifies the phrases the model weighs most heavily when calculating the sentence.

To evaluate our model, we fed it 50 new sentencing scenarios it had never seen before. We then compared the model’s predicted sentence length with the actual sentences.

The relatively simple model worked quite well. It predicted sentences with an average error of just under 12 months.

The model learned that words or phrases such as “sexual”, “young person”, “taxi” and “firearm” correlated with longer sentences, while words such as “professional”, “career”, “fire” and

16

TECHNOLOGY

We built an algorithm that predicts the length of court sentences – could AI play a role in the justice system?

Continued on page 21

Letter to the editor

In praise of the late Sir Ian Barker KC

Like many, I was saddened by the passing of Sir Ian and thank you for the article in LawNews

I was taken back many years to the 1960s when reading his reminiscences that you reprinted. I first encountered Sir Ian when he was our lecturer in civil procedure in 1966. Lectures were at the early hour of 8am and I always recall him saying to us, “if it’s good enough for me to get up early, then it’s good enough for you”.

His reminiscences of the Auckland legal scene in the ‘60s are absolutely as I recall. We worked part-time as law clerks in the latter stages of our studies and, as he says, we would often meet up when searching land titles in the then Land Transfer Office or filing documents

in the then Magistrates Court.

I later came to know him socially and then later, when I had moved down to the Bay of Plenty, I would sometimes appear before him as counsel on the ‘divorce days’ that we then had in the Rotorua High Court. My impression was that he enjoyed the circuit work.

He always had a great memory and was uniformly pleasant to appear before.

David Sparks Rotorua

Events

17 Dec 9, 2022 Issue 44

Sir Ian Barker KC

From left – Tina Hwang, Mark Colthart, Marie Dyhrberg KC, Brett Harris, Vicki Ammundsen, Tony Herring, Bill Patterson, Dr Robert Makgill, Catherine Stewart, Tim Jones, Joanna Pidgeon, Julian Hague, Emma Priest, Lloyd Gallagher and Julie-Anne Kincade KC

committees

Thursday 16 November, Park Hyatt, Auckland

ADLS

Christmas function

Events

ADLS annual breakfast

18

ADLS hosted its annual breakfast with Attorney-General David Parker on Friday 2 December at the Rydges in Auckland.

Marie Dyhrberg KC, David Parker and Tony Herring

David Bricklebank, Stephen Hunter KC and Bronwyn Carruthers KC

Kiri Harkess, Marie Dyhrberg KC and Linda Hui

Lucy Rong and Kelly Cocks

Attorney-General David Parker and Judge Kathryn Beck

ADLS Christmas party

19 Dec 9, 2022 Issue 44

ADLS’ Christmas party was held at The Maritime Room in Auckland on Thursday 1 December.

Robert Collis, Gary Gotlieb and Judge Gerard Winter

Brett Cunningham, Monique Pearson and John Hannan

Hermann Grobler, Marie Dyhrberg KC and Tony Herring

Richard Gardner and Vaheeni Naidoo

Chris Eggleston and Moira Macnab

Events

Hamilton Sundowner

20

Held at The Verandah Cafe & Function Centre on Wednesday 23 November.

Andrew Clements, Simone Dowling, Philip McHugh, Donna Gifford and Rodney Lewis

Conan Brolly, Emma O’Keeffe, Hannah Espin and Jesse Savage

Treasure McKinstry, Judy Leeson, Kyra Wells and Jo Douglas

Sasha Rietema, Marie Dyhrberg KC, Lythan Chapman and Jasmine Jackson

Jamie Lomas, Anna Jackman, Toby Braun and Sarah Rawcliffe

Continued from page 06

trust by an unauthorised method. A focus on a settlor’s objectives might achieve a de facto modification of a trust.

I understand that in the United States some trust statutes require amendments to be made in accordance with the terms of a deed of trust but several other states allow a trust to be amended “by any other method manifesting clear and convincing evidence of the settlor’s intent”.

It would seem heretical in New Zealand to allow a deed of trust to be amended by reference to a clear and unequivocal statement of a settlor’s objectives but this scenario will arise and the courts will need to resolve it.

Parliament appears to have given a kind of supremacy to the implementation of a settlor’s

Continued from page 16

“Facebook” correlated with shorter sentences.

Many of the phrases are easily explainable. “Sexual” or “firearm” may be linked with aggravated forms of assault. But why does “young person” weigh towards more time in prison and “Facebook” towards less? And how does an average error of 12 months compare to variations in human judges?

The answers to those questions are possible avenues for future research. But it is a useful tool to help us understand sentencing better. Clearly, we cannot test our model by employing it in the

objectives and this is bound to conflict in some cases with the express terms of a trust.

Another problem that may arise by focusing on a settlor’s objectives is the difficulty of identifying what these are when there are two or more settlors or where there is a nominal settlor.

In the case of a nominal settlor, I think there is a sufficient recent law that would cause judges to ignore the intentions of a nominal settlor and prefer the intentions of the substantive settlor.

So far as multiple settlors are concerned, there may be factual problems in identifying each settlor’s wishes but if, say, the objectives of most of settlors are the same, then in general the objectives of the majority would probably prevail.

These questions are all likely to arise for determination. In the meantime, I recommend that trust advisors try to ensure that settlors are recording up-to-date objectives for their trusts and ensuring the objectives can be implemented in accordance with the terms of the trust.

If, for example, the objectives will require a trust deed to be modified and if the deed has a provision authorising the modification, then the modification should be made. ■

courtroom to deliver sentences. But it gives us an insight into our sentencing process.

Judges could use this type of modelling to understand their sentencing decisions and perhaps remove extraneous factors. AI models could also be used by lawyers, providers of legal technology and researchers to analyse the sentencing and justice system.

Maybe the AI model could also help create some transparency around controversial decisions, such as showing the public that seemingly controversial sentences like a rapist receiving home detention may not be particularly unusual.

Most would argue that the final assessments and

decisions on justice and punishment should be made by human experts. But the lesson from our experiment is that we should not be afraid of the words “algorithm” or “AI” in the context of our judicial system. Instead, we should be discussing the real (and not imagined) implications of using those tools for the common good.

■

Andrew Lensen is a lecturer in artificial intelligence and Marcin Betkier is a law lecturer at Victoria University of Wellington ■

The above was first published by The Conversation and is republished with permission

NEW EDITION OUT NOW

Sale of Land 4th edition

Author DW McMorland

Author DW McMorland

The 4th edition of this essential text is now available.

The previous edition was published in July 2011. In the intervening 11 years, there have been changes in the relevant statute law along with land case law, including significant Court of Appeal and Supreme Court judgments.

A major change impacting conveyancing has been the relentless computerisation of banking. This has resulted in:

■ banks no longer issuing bank cheques or accepting other cheques;

■ the increased use of due diligence conditions, raising issues

of overlap with other terms of the agreement for sale; and

■ significant changes to the Agreement for Sale and Purchase form, resulting in the 11th ed 2022 on which this book is based.

The 4th edition states the law as at 31 December 2021.

Price for ADLS members $189 plus GST*

Price for non-member lawyers $210 plus GST*

To purchase this book please visit https://adls.org.nz or contact the ADLS bookstore by phone: 09 306 5740 or email: thestore@adls.org.nz

* + Postage and packaging

21 Dec 9, 2022 Issue 44

Anthony Grant is an Auckland barrister specialising in trusts and estates ■

When considering a settlor’s objectives for a trust, it must be recognised that the objectives are likely to change over time

Partnership law

Webinar 1 CPD hr

Tuesday 13 December

12pm – 1pm

Price from $80 +GST

Presenters Gerard Dale, partner, Dentons Kensington Swan and Sarah Gibbs, senior associate, Dentons Kensington Swan

Is the partnership structure still relevant in the 21st century? What is a partnership and how do you know if you’re in one? How do you establish a partnership and what are the common issues and pain points?

FIND OUT MORE

Personal effectiveness workshop

In Person 4 CPD hrs

Thursday 9 February

9am – 1.15pm Price from $400 +GST Facilitator Tony Gardner, managing director, Archetype Leadership + Teams

Do you have a clear vision for 2023?

Could you improve your work methods? Are you trying to get to grips with working effectively in a hybrid model?

Landonline update

Webinar 1 CPD hr

Monday 13 February

12pm – 1pm

Presenter Andrea Watson, consulting solicitor for the Modernising Landonline program, LINZ

This webinar offers tips on using the new Landonline functionality along with updates on what the system will look like in the future.

FIND OUT MORE FIND OUT MORE

22 FEATURED CPD ALL LEVELS IMPROVEMENT WORKSHOP

INTERMEDIATE COMMERCIAL WEBINAR

ALL

PROPERTY WEBINAR

LEVELS

FINAL NOTICE

adls.org.nz/cpd cpd@adls.org.nz 09 303 5278

Writing right – for family lawyers

Livestream | In Person

2 CPD hrs

Thursday 16 February 2023

4pm - 6.15pm

Price from $140 + GST

Presenters Judge Kevin Muir and Brian Carter, barrister