scheie vision

celebrating

150 years

Caring for Community and Country

Healthcare Heroes, Then and Now

The Role of UPenn Ophthalmology in the World Wars

Scheie and the British Royal Family Pioneering Advances in Science and Education

Looking Back: Early Inventions and Research

From my days as a medical student at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn), and throughout the ensuing two decades, the Scheie Eye Institute and the Department of Ophthalmology at UPenn have been synonymous to me with excellence in research, clinical practice, and education. As you all know, without question, this continues to be the case. It is therefore an incredible and humbling honor for me to return to Scheie as the new Chair of the Department of Ophthalmology.

In just the very short time that I have been here, I have witnessed firsthand the delivery of outstanding and compassionate clinical care, the promise of groundbreaking and innovative research with translational impact for our patients, and the focus on first-rate education for learners at all stages, including medical students, residents, and fellows. All of this is possible because of the people; the dedicated faculty, trainees, and staff are a cohesive community that set this Department apart from all others.

Without question, the history of the Department and of the Scheie Eye Institute tells the story of some of the nation’s greatest achievements in ophthalmology, which you can read about in this publication. Under the stewardship of the former Chairs and Directors, the Department rose to and

Managing Editor: Rebecca Salowe | Research and Writing: Isabel Di Rosa, Kristen Mulvihill, Rebecca Salowe, Marquis Vaughn, Selam Zenebe-Gete Faculty Leads: Joan O’Brien, MD, Charles Nichols, MD | Faculty Editor: Benjamin Kim, MD | Chairman: Bennie Jeng, MD Design: Caren Goldstein | Printing: Quaker Printing Cover images courtesy of University of Pennsylvania Archives, Brian Holmes, Rui Ochoa (Champalimaud Foundation), Peggy Peterson, and Scott Spitzer

has held its place amongst the upper echelon of ophthalmologic institutions across the country. So where do we go from here?

As we enter into the second 50 years of the Scheie Eye Institute and approach the 150th anniversary of the Department, I see an unparalleled opportunity to build upon the foundation that has been established to further our mission. My vision is to create a supportive and nurturing culture of inclusiveness and diversity that will foster the successes of each member in their chosen areas of interest. This will not only help each individual to achieve their personal goals, but will also elevate the stature of the entire department to one that is recognized as a top program in every domain. With the support of colleagues and friends such as yourself, I have no doubt that we will see this happen, and I am pleased that you will be able to see us through in this exciting journey!

With best regards,

Established in 1874, the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) proudly celebrates 150 years of excellence. The Scheie Eye Institute, opened in 1972, has remained at the forefront of innovation over the last 50 years, transforming the way that patient care, research, education, and community service are conducted. We are thrilled to present this special anniversary edition magazine, showcasing extraordinary moments from our past and remembering the inspiring individuals who made the last 150 years possible.

The Department of Ophthalmology has experienced immense change and growth over the last 150 years. Beginning with our original location in the basement of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, we now offer eye care in six clinical facilities across Philadelphia and Delaware County. Our faculty currently consists of 68 brilliant individuals, including five members of the Academy of Master Clinicians and four UPenn Advisory Deans, representing 20% of our clinical faculty. The Department now offers every subspecialty of ophthalmic care and sees more than 130,000 patient visits each year.

With respect to our research mission, the Department has become a top recipient of National Eye Institute funding nationwide for the past five years. Our faculty consistently conduct transformative research, publishing results in high-impact journals each year. The Department remains a leader in research impact, with our H-index steadily increasing each year. We have also developed strong partnerships with foundations, non-profits, and industry, and have raised over $43 million in philanthropy since 2010.

Similarly, our educational mission has progressed over the years, increasing from two residents in 1937 to 15 residents in 2022. Our residency program receives more than 600 applications for five positions each year, and consistently matches with diverse, talented, and compassionate individuals. Surgical volumes for residents have increased by 88% since 2010 and the number of grants/trials per alumnus ranks in the top 1% of programs across the country. Our third-year residents consistently secure top choice fellowships at outstanding institutions.

Over the years, our faculty, staff, and trainees remain committed to making an impact through service initiatives in the community. Programs such as Penn Sight Savers and Puentes de Salud, staffed by volunteer physicians, residents, and medical students, provide comprehensive ophthalmic care to patients who are often uninsured and undocumented. Several times a year, our faculty and staff organize screening events across Philadelphia, providing free health and eye screenings. In the past decade, our faculty have traveled to more than 30 countries to provide eye care to desperately at-risk and underserved populations internationally.

We hope you enjoy reading through these pages celebrating the milestones and individuals who have made the Department of Ophthalmology and the Scheie Eye Institute a truly remarkable place.

Sincerely,

Bennie H. Jeng, MD Harold G. Scheie Chair and Professor Chairman, Department of Ophthalmology Director, Scheie Eye InstituteJoan O’Brien, MD Director, Penn Medicine Center for Ophthalmic Genetics in Complex Diseases Harold G. Scheie-Nina C. Mackall Professor of Ophthalmology Inducted Member, National Academy of Medicine

Charles W. Nichols, MD Associate Professor of Ophthalmology Chief of Ophthalmology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

In 2024, the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) will celebrate the 150th Anniversary of its founding in 1874. This milestone is the culmination of numerous achievements and contributions, many of which are commemorated below.

1871

1765

The Trustees of the College of Philadelphia (later called the University of Pennsylvania) establish the first medical school in the American colonies.

1784

Benjamin Franklin invents bifocal glasses.

1805

Philip Syng Physick, MD, becomes Penn’s first professor of surgery, separating surgery from anatomy and midwifery. He develops a novel method to extract cataracts.

Construction begins for the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP), the first university-owned hospital in the United States built expressly for the purpose of teaching.

1787

The College of Physicians of Philadelphia is founded.

1874

The Department of Ophthalmology at HUP is founded. William F. Norris, MD is appointed the first Professor of Ophthalmology

1861-1865

The Civil War divides the medical school. Approximately 660 Penn medical alumni serve as Union army surgeons and 550 as Confederate army surgeons.

1751

Pennsylvania Hospital is founded by Benjamin Franklin and Dr. Thomas Bond.

Penn medical faculty and alumni support American troops fighting for independence during the Revolutionary War. John Morgan, founder of Penn’s medical school, serves as Director-General of the Continental Army’s hospital.

1855

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is founded by Francis West Lewis.

1897

The Agnew Wing of the University Hospital, which provides eye wards for men and women, is constructed.

More than 200 surgical procedures are performed in the eye clinic, which is more than any other department at the University Hospital.

Dr. de Schweinitz co-founds the American Board of Ophthalmology.

The Graduate School of Medicine is organized, which includes a program offering specialized training in ophthalmology.

The United States enters World War I. The Civilian Base Hospital No. 20 in France is staffed by Penn physicians and medical students, with a special ward for patients with ophthalmic injuries.

Dr. de Schweinitz is part of the medical care team that treats President Woodrow Wilson after a stroke.

Thomas B. Holloway, MD, becomes the third Chairman of Ophthalmology. A slit lamp microscope is installed in the eye dispensary and a laboratory of perimetry is established. Dr. Holloway advocates for greater endowment of ophthalmology departments and becomes one of the first ophthalmologists to use films for scientific and educational purposes.

The annual de Schweinitz Lecture and Dinner is founded as a memorial to Dr. de Schweinitz.

The influenza pandemic spreads through Philadelphia. The Ophthalmology Department, then located at HUP, refocuses effort on treating these patients.

George E. de Schweinitz, MD, becomes the second Chairman of the Department of Ophthalmology. He creates an operating room for eye surgery, renovates the eye dispensary and ophthalmic pathology laboratory, and forges important collaborations with other departments

Francis Heed Adler, MD, becomes the fourth Chairman of Ophthalmology. He moves and expands the clinic and eye ward, promotes innovative clinical research, and improves the training of eye specialists. Dr. Adler is later named the first William F. Norris and George E. de Schweinitz Professor of Ophthalmology.

The first residency program at Penn is established.

Harold G. Scheie, MD, becomes the first ophthalmology resident to complete the full three-year program.

The United States enters World War II. Penn physicians, including ophthalmologists, organize and run the US Army 20th General Hospital in Burma, India.

The Scheie Eye Institute is founded by Dr. Scheie at the Presbyterian Medical Center in Philadelphia.

Stuart Fine, MD, becomes the seventh Chairman of Ophthalmology. Dr. Fine expands the faculty threefold, increases the number of endowed chairs from three to eight, and sees considerable growth in the clinical practice and educational programs.

The Veterans Administration Hospital of Philadelphia opens, with the UPenn Ophthalmology Department designated as its sole ophthalmic provider.

The first female resident is appointed at Scheie.

Dr. Scheie becomes the fifth Chairman of Ophthalmology. He creates an elective five-year training program that includes two research years, pioneers glaucoma research and treatments, and develops affiliations with the new VA Hospital and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He begins to raise funds for a new eye hospital at UPenn.

The Penn Vision Research Center is established.

Maureen Maguire, PhD, establishes the Center for Preventive Ophthalmology and Biostatistics (CPOB). The F.M. Kirby Center for Molecular Ophthalmology is established with a generous gift from the F.M. Kirby Foundation.

Alexander Brucker, MD, founds the scientific journal RETINA, which has become the world’s leading journal for retinal and vitreous diseases.

Myron Yanoff, MD, becomes the sixth Chairman of Ophthalmology. Dr. Yanoff establishes prosperous retina, cornea, and glaucoma services and recruits many skilled ophthalmologists. James Katowitz, MD, establishes a plastic surgery service.

The Center for Hereditary Retinal Degenerations is established by Samuel Jacobson, MD, PhD.

Presbyterian Medical Center becomes part of the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

The Ruth and Raymond Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine opens.

A formal, reciprocal agreement is reached with the Aravind Eye Hospital in Southern India. Scheie residents may visit Aravind during their elective time in the third year for four weeks.

2022

Bennie H. Jeng, MD is named the ninth Chairman of Ophthalmology.

2022

The Penn Medicine Center for Ophthalmic Genetics in Complex Diseases opens, with Chairman Emeritus Joan O’Brien, MD, as the Inaugural Director.

Joan M. O’Brien, MD, becomes the eighth Chairman of Ophthalmology and first female Chair. She expands the number of subspecialities to 17, conducts groundbreaking research on the genetics of glaucoma in African Americans, and forges powerful industry collaborations. Under her direction, the Department consistently ranks as a top recipient of NEI funding nationwide.

The first gene therapy for an inherited eye condition (Luxturna) is approved by the FDA. For this achievement, Drs. Jean Bennett, Samuel Jacobson, and Albert Maguire are awarded the 1 million euro Champalimaud Vision Award.

UPenn announces the creation of the Penn Center for Advanced Retinal and Ocular Therapeutics (CAROT), with Jean Bennett, MD, PhD and Albert Maguire, MD as co-directors.

Extensive renovations of the Scheie Eye Institute are completed.

Images courtesy of University of Pennsylvania Archives and Library of Congress.The Ophthalmology Department at the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) was officially established in 1874, but its story began long before then. Below, we highlight the leaders, both before and after the founding of the Department, who pioneered advancements in clinical care, research, and education. The leadership of these remarkable individuals helped the Department grow into the renowned, internationally recognized institution it is today.

Key Contributors to the Birth of the Ophthalmology Department from 1700s-1874

Beginning in the early 1700s, innovations in ocular treatment and surgery, research, and teaching laid the groundwork for the founding of the Department. Below, we highlight several key individuals who pioneered these changes.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790)

Benjamin Franklin was a printer, inventor, and founding father of the United States. He is considered the primary founder and shaper of the University of Pennsylvania. Among his many inventions, he is credited with developing the first pair of bifocals in 1784.

Philip Syng Physick, MD (1768-1837)

Widely considered the “Father of American Ophthalmology,” Dr. Physick served as a Professor of Surgery (1805-1819) and Professor of Anatomy (1819-1831) at UPenn. He pioneered a number of surgical innovations, including the development of a novel method to extract cataracts. When the yellow fever epidemic struck Philadelphia in 1793, he was one of the few physicians to remain in the city and treat fever victims.

As the successor to Dr. Physick, Dr. Gibson served as the Professor of Surgery at UPenn for 36 years. He was considered the leading surgeon in Philadelphia in the earlyto mid-1800s. Dr. Gibson was uniquely skilled in eye surgery and became the first surgeon to operate for strabismus. He wrote the

Dr. Horner was a Professor of Anatomy at UPenn and the Dean of the Medical School from 1822 to 1852. He is credited with discovering and dissecting the tensor tarsi muscle (now called Horner’s Muscle), and was the first to explain how tears pass from the conjunctival sac to the nose.

popular medical textbook The Institutes and Practice of Surgery, which included several detailed sections on eye diseases and treatments.

popular medical textbook The Institutes and Practice of Surgery, which included several detailed sections on eye diseases and treatments.

A Professor of Surgery at UPenn, Dr. Agnew was well-known for his teaching ability and his ambidextrous surgical skill. He wrote several volumes of The Principles and Practice of Surgery, which included sections on the eye. Dr. Agnew is the subject of the famous painting The Agnew Clinic, which was commissioned by students upon his retirement. He is often considered the last of the great general surgeon-ophthalmologists in Pennsylvania, ending an era when general surgeons operated on the eye.

Over the last 150 years, nine Chairmen of the Department of Ophthalmology committed their careers to fostering the growth of faculty, staff, patients, trainees, and alumni. Below, we take you on a journey through the Department, beginning with the first appointed chair, William F. Norris, MD, all the way to the current chair of the Department, Bennie H. Jeng, MD.

In 1870, William F. Norris, MD and George C. Strawbridge, MD were appointed to establish an eye and ear clinic at UPenn. Located at Ninth and Chestnut Street, the Eye Dispensary opened on October 6, 1870. In 1874, Dr. Norris became the first Professor of Diseases of the Eye at UPenn—only the fourth such appointment in the United States. During his time as Chairman, Dr. Norris was committed to teaching and research. He gave weekly lectures on ophthalmology to interested students in an anatomical amphitheater, which became a formal part of the curriculum in 1879. Dr. Norris contributed vastly to various ophthalmology texts, authoring one of the first nationally recognized textbooks in ophthalmology. He also pioneered the usage of photography for medical and surgical cases. Dr. Norris played an instrumental role in the founding of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, one of the first university-owned hospitals that was dedicated to medical student education. During the Civil War, Dr. Norris served with distinction as a surgeon for the U.S. Army.

George E. de Schweinitz

succeeded Dr. Norris as Chairman in 1902. Under his leadership, the eye dispensary was remodeled and expanded, and both an ophthalmic pathology lab and an operating room for ophthalmological procedures were constructed. By 1924, the ophthalmology clinic was the third largest clinic at UPenn, behind only the medical and surgical clinics. Dr. de Schweinitz forged important collaborations with other departments for consultations and led lab projects in newly acquired lab space. His book Diseases of the Eye became the official handbook for the students in the clinic. To date, Dr. de Schweinitz is the first and only ophthalmologist to serve as President of the American Medical Association. Over the years, Dr. de Schweinitz sustained a large and impressive practice, with President Woodrow Wilson among his patients. His efforts helped to establish the nation’s first certifying board—the American Board of Ophthalmic Examination, now named the American Board of Ophthalmology. During World War I, Dr. de Schweinitz was appointed to the Council of Defense as Major and became Brigadier General in the Medical Reserve Corps in 1922.

The legacies of both Drs. Norris and de Schweinitz have been honored by the Department through the William F. Norris and George E. de Schweinitz Professorship of Ophthalmology.

William F. Norris, MD George E. de Schweinitz, MD David Hayes Agnew, MDThomas B. Holloway, MD followed Dr. de Schweinitz as Chairman of the Department in 1924. Dr. Holloway was sincerely committed to teaching, having previously led the development of an ophthalmology training program in the Graduate School of Medicine in 1916. He also contributed greatly to clinical studies in the field of ophthalmology and brought various clinical instruments and upgrades to the Department. He introduced a slit lamp in the eye dispensary, as well as a laboratory of perimetry, used for visual field testing. Dr. Holloway was also among the first ophthalmologists to use films for scientific and educational purposes.

Francis Heed Adler, MD succeeded Dr. Holloway as Chairman in 1937, a time when ophthalmology residency programs were emerging across the nation. In 1937, the Department introduced the first residency program at UPenn. Dr. Adler prided himself most on improving the training of eye specialists. Furthermore, he promoted innovative clinical research and advocated for expanding the ophthalmology clinic to provide necessary facilities for resident training. Dr. Adler received a generous gift to rebuild the eye wards and expand patient occupancy. Under his leadership, the eye clinic was moved to a more spacious area. In 1945, Dr. Adler was named the inaugural William F. Norris and George E. de Schweinitz Professor of Ophthalmology.

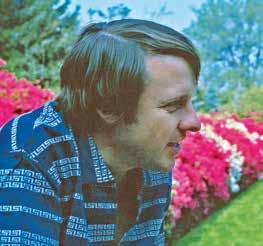

Among one of the first residents when the residency program was introduced, Harold G. Scheie, MD experienced a long history with the Department. Before becoming Chairman, he was the first resident to finish the full three-year program in ophthalmology at UPenn. During World War II, Dr. Scheie served active duty as a captain in the Army Medical Corps and was Chief of Ophthalmology at the 20th General Hospital in India. When Dr. Scheie became Chairman in 1960, the Department’s residency program excelled. He established an elective five-year training program to provide residents with research and basic science experience. Clinical research also flourished under his leadership, as Dr. Scheie pioneered novel glaucoma research and treatment methods. Dr. Scheie led the fundraising efforts to build a new $12.5 million eye hospital, opened in 1972 and named the Scheie Eye Institute. During his time as Chairman and beyond, Dr. Scheie maintained an international reputation and greatly contributed to literature. Even after he retired from active practice, Dr. Scheie remained involved in raising funds for the Institute’s endowments.

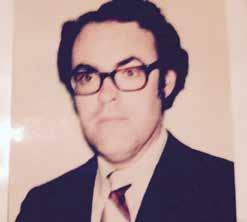

Myron Yanoff, MD succeeded Dr. Scheie and became the sixth Chairman in 1978. Among Dr. Yanoff’s many accomplishments as Chairman, he successfully promoted the growth of subspecialties within the Department. Dr. Yanoff established prosperous glaucoma, retina, corneal and external disease, oculoplastics, and comprehensive ophthalmology services. These subspecialties all aimed to provide innovative patient care and superior training to medical students and residents. Furthermore, Dr. Yanoff recruited many skilled ophthalmologists and promising trainees to Scheie during his time as Chairman.

Stuart L. Fine, MD

Stuart L. Fine, MD assumed the role of Chairman in 1991. Dr. Fine largely contributed to the fields of public health and epidemiology, namely establishing the Center for Preventive Ophthalmology, Biostatistics, and Epidemiology in 1994. Dr. Fine appointed Maureen Maguire, PhD, an internationally recognized researcher, as Director of the Center. The Center, now named the Center for Preventive Ophthalmology and Biostatistics, serves as the hub for coordinating multicenter studies. During his term as Chairman, Dr. Fine also established the F.M. Kirby Center for Molecular Ophthalmology. This Center aims to elucidate the mechanisms of blinding retinal diseases and to develop novel therapies for these diseases.

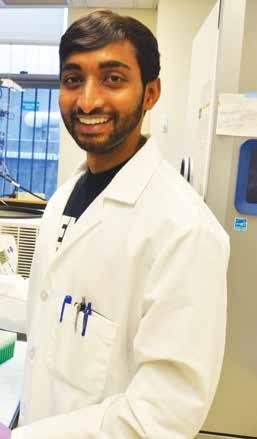

Joan M. O’Brien, MD

Joan M. O’Brien, MD joined the University of Pennsylvania in 2010 as the first female Chairman and Director of the Scheie Eye Institute. During her 12-year tenure, she led the expansion of the Department. The faculty grew from 24 to 68 individuals in all subspecialties, and the clinicians now see more than 130,000 patient visits per year. Under Dr. O’Brien’s leadership, the Department was continually a top five recipient of National Eye Institute funding, and the residency program consistently ranked in the top 5% nationwide for research output per alumnus. In 2014, Dr. O’Brien oversaw extensive renovations of the Scheie Eye Institute. In her 12 years as Chairman, she helped raise over $43M in philanthropy.

In addition to these contributions, Dr. O’Brien spearheaded the $17.9M Primary Open-Angle African American Glaucoma Genetics study. This study aims to find targeted treatments for glaucoma, which disproportionately affects the Black population, and has enrolled over 10,200 Black patients in Philadelphia. Dr. O’Brien has received numerous honors for her contributions to

ocular oncology and genetics, including induction into the National Academy of Medicine in 2013. Dr. O’Brien currently serves as the Inaugural Director of the Penn Medicine Center for Ophthalmic Genetics in Complex Diseases. This Center seeks to elucidate the genetics of diseases that overaffect African ancestry populations, with the long-term goal of developing personalized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to address this unmet need.

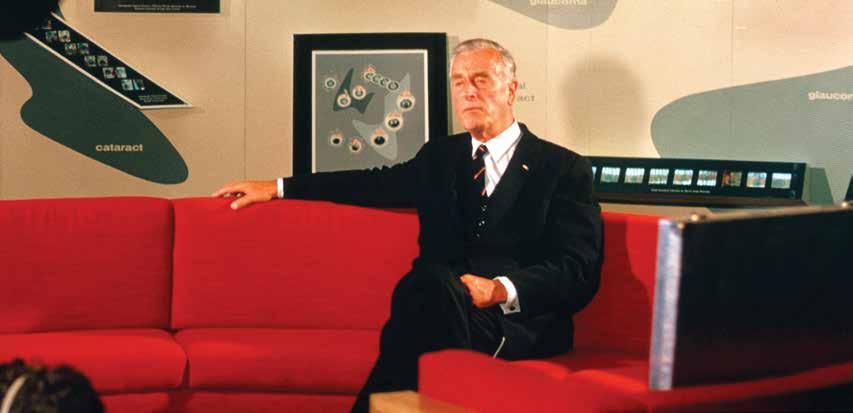

Bennie H. Jeng, MD, current Chairman of the Department of Ophthalmology and Director of the Scheie Eye Institute, is a nationally recognized clinicianscientist and surgeon who specializes in cornea and external diseases. Before holding this position, Dr. Jeng served for nine years as Chairman of the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. With a translational research interest in corneal wound healing and infectious keratitis, his more recent work in clinical trials includes serving as co-Chair of the NEI-funded Zoster Eye Disease Study. Dr. Jeng has a special interest in fostering the professional growth of young faculty members and trainees to become outstanding funded researchers and leaders in the field, and he has been very successful in this endeavor.

In his current role as Chairman, Dr. Jeng plans to continue his efforts in promoting the career development of the Scheie faculty and residents. He is also planning for a significant expansion of the basic and translational research enterprise, which will include increasing collaborative research with other groups on the UPenn campus. In addition, he is strategizing for a dramatic growth of the clinical enterprise, including further expansion into the suburbs to help provide better access for patients who live outside of the city. For the educational mission, Dr. Jeng looks forward to enhancing the existing outstanding programs in undergraduate and graduate medical education to provide the very best in ophthalmic education at UPenn. n

Albert, D. M., & Scheie, H. G. (1965). A history of ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas.

Frayer, W. C. (2002). An ophthalmic journey: 50 years at the University of Pennsylvania. William C. Frayer, M.D.

Note: Unless otherwise specified, headshots were retrieved from the University of Pennsylvania Archives.

Stuart L. Fine, MD Courtesy of Dan M. Albert, MD

Joan M. O’Brien, MD

Courtesy of Peggy Peterson

Bennie H. Jeng, MD

Stuart L. Fine, MD Courtesy of Dan M. Albert, MD

Joan M. O’Brien, MD

Courtesy of Peggy Peterson

Bennie H. Jeng, MD

In 1874, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania opened, becoming the first teaching hospital in the nation. That same year, the Department of Ophthalmology was established. On February 3, William F. Norris, MD was appointed the first Professor of Diseases of the Eye at the University—only the fourth such appointment in the country.

The eye clinic was located in the lower level of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP), which was the original location of the Department of Ophthalmology. The first clinical records of the Department were found in leatherbound journals.

As the first Chairman of the Department, Dr. Norris was committed to research, contributing to many ophthalmology texts and initiating the study of ocular pathology within the Department. Dr. Norris became an expert in medical photography and greatly contributed to the rise of the usage of

the ophthalmoscope, an instrument used to observe the retina. During his time as Chairman, he also recruited distinguished faculty members to join the Department.

In 1897, construction of the Agnew Wing of the University Hospital was completed, providing additional eye wards for men and women. By 1901, more than 200 surgical procedures were performed in the eye clinic—more than any other department at the University Hospital at the time.

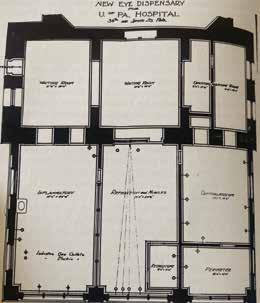

Following Dr. Norris’s unexpected death in 1901, George E. de Schweinitz, MD was selected as the second Chairman of the Department. Under Dr. de Schweinitz’s leadership, the ophthalmic pathology laboratory and the eye dispensary were renovated and expanded, tripling the number of patients seen. Additionally, an operating room for eye surgery was constructed in the Department.

At this time, no national standards existed for ophthalmic care. Dr. de Schweinitz, along with other leading ophthalmologists, set out to change this. In 1916, he helped to found the American Board of Ophthalmic Examination (later renamed the American Board of Ophthalmology), the nation’s first certifying board.

As the Department of Ophthalmology continued to advance, the

early 19th century brought global crises. In 1914, World War I began, a fatal conflict with lasting effects. In 1918, a deadly epidemic, known as “The Great Influenza,” spread rapidly across the globe. To read about how UPenn and the Department of Ophthalmology responded to these catastrophic events, turn to page 21, “Healthcare Heroes, Then and Now,” and page 25, “The Role of UPenn Ophthalmology in the World Wars.” n

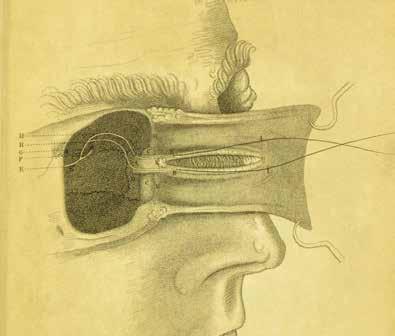

Cataract knives used by William F. Norris, MD.

Reference

Albert, D. M., & Scheie, H. G.

Note: All images included in this article were taken from this text.

(1965). A history of ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas.

Eye operating room (1907).

Plans for the new eye dispensary for the University of Pennsylvania Hospital (1903). Waiting room in remodeled clinic (1905).

(1965). A history of ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas.

Eye operating room (1907).

Plans for the new eye dispensary for the University of Pennsylvania Hospital (1903). Waiting room in remodeled clinic (1905).

Alongside the expansion of its clinical practice and research scope, the Department of Ophthalmology has undergone several changes in location over the past 150 years. Here, we walk through the history of physical spaces that have housed the Department over the years.

In 1874, architect Thomas Webb Richards designed the original building of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Richards was the University’s first professor of drawing and architecture. The plot of land on which the hospital was built was donated by the city of Philadelphia on the condition that 50 free beds were provided for low-income community members who were ill. Both State funds and private funds were used to finance the construction.

When the hospital opened in June of 1874, an eye clinic was nestled in the lower level of the building: the Department of Ophthalmology was born. William F. Norris, MD, the first Chairman of the Department, was one of 11 doctors on the medical staff of the hospital at the time of its opening.

Named for UPenn surgeon David Hayes Agnew, MD, the Agnew Wing of the Hospital was designed by Cope and Stewardson Architects and opened in 1897. The eye clinic moved to the Wing, which housed 160 beds and five wards, two of which were ophthalmic wards. Located on the second floor, one of the wards was for women and the other for men. Dr. Norris also opened an ocular pathology laboratory in the Agnew Wing. In 1902, George E. de Schweintz became the second Chairman of the Ophthalmology Department and advocated for an operating room for eye surgery. The eye dispensary and lab were also expanded and renovated in the Agnew Wing.

In 1937, a fire broke out, likely due to an electric short circuit. Engulfing much of the building, flames reportedly shot 20 feet in the air from the rooftop. In just 18 minutes, all 78 patients in the affected areas had been carried or led to safety. Thankfully, no one was seriously injured. Shortly after this fire, Francis

THE ORIGINAL BUILDING

Top image: The original building of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, 1888 Retrieved from University of Pennsylvania Archives.

Bottom left image: “The New University Hospital,” September 1874. Retrieved from the Philadelphia Inquirer Archives.

THE AGNEW BUILDING

Middle image: The Agnew Wing, November 1904. Retrieved from University of Pennsylvania Archives

Bottom right image: The Agnew Wing fire, February 1937. Retrieved from the Philadelphia Inquirer Archives

Heed Adler, MD, Chair of the Department at the time, moved the eye clinic to a different part of the hospital, where the Gates Pavillion was eventually erected. The new clinic was located on the third floor, where it remained until the opening of the Scheie Eye Institute.

In 1960, Harold G. Scheie, MD became the fifth Chairman of the Department and subsequently founded the Scheie Eye Institute. The multimillion-dollar construction of the building began in 1969 at the Presbyterian University of Pennsylvania Medical Center (now Penn Presbyterian Medical Center). The new institute was funded in part by a $3 million anonymous donation.

Ground was broken on December 8, 1969. In May of 1971, a “Topping Out” ceremony was held to celebrate the halfway point of construction. Cutting the ribbon were Dr. Scheie, his wife Mary Ann Scheie, and Mabel Pew Myrin, Honorary Chairman of the Friends of the Scheie Eye Institute.

The Scheie Eye Institute opened in 1972. Designed by architect Dick Colville of the Kling Partnership, the building’s exposed structural concrete and brick are characteristics of the brutalist architecture style. The interior design matched the circular exterior. The waiting room featured rounded seating areas, circular paneless windows, and an oval-like reception desk. The formal dedication of the building was led by Lord Mountbatten of the British royal family, who had been treated by Dr. Scheie for an eye injury.

Images from top to bottom: CONSTRUCTION OF SEI ca. 1972. Retrieved from University of Pennsylvania Archives.

TOPPING OUT CEREMONY

May 1971. From left to right: Mary Ann Scheie, Harold G. Scheie, MD, Mabel Pew Myrin. Retrieved from the Philadelphia Inquirer Archives.

THE SEI COMPLETION

Exterior of the original SEI building, c. 1970-1980. Courtesy of the Department of Ophthalmology Archives.

ROUNDED EXTERIOR OF THE SEI

Bottom left image: Courtesy of Ralph C. Eagle.

THE LOBBY OF THE ORIGINAL SEI Bottom right image: c. 1970-1980. Courtesy of the Department of Ophthalmology Archives.

Images from top to bottom: Renovated lobby with new lighting and seating.

Courtesy of BBLM Architects

New banquet seating in the lobby. Courtesy of BBLM Architects

Renovated exam room. Courtesy of BBLM Architects

In 2014, the interior of the Scheie Eye Institute underwent extensive renovations under the leadership of Joan O’Brien, MD, eighth Chairman of the Department. The project, led by Brandon Sargent of BBLM Architects, aimed to improve the outpatient experience by reconfiguring and modernizing the lobby and first and fifth floor clinical spaces. Throughout the renovation, efforts were made to feature the architectural details of the original building, such as the exposed brick and the circular cutouts of the large concrete walls, which had been covered up over the years.

In the lobby, noise issues were addressed. Sargent explains: “[We] looked at every surface in the lobby to figure out how we could add some sound absorption quality.” This included the carpeting, the wood-paneled lower walls with sound insulation, and the upper walls with sound absorption plaster finish. In addition, Sargent emphasized the “suspended cloud in the top of the lobby,” used to interrupt sound travel throughout the lobby.

Indirect lighting, such as light-colored surfaces and illuminated cylinders in the ceiling coffers, was utilized to protect patients with dilated eyes while still brightening the once dark space. As part of the renovation, the first floor was also reconfigured to become more accessible, with decentralized check-in desks to allow for more privacy, custom banquet seating, large bathrooms, and an updated optical shop. The designs included rounded elements to match the building’s architecture.

In addition to these updates, 30 exam rooms were entirely renovated and fit with new, state-of-the-art technology. To evaluate the exam room design, physicians and technicians saw patients in a working mock-up room and made constructive comments about how to improve the layout. Because of this collaboration, the exam rooms continue to function well today, nearly a decade later.

The Department of Ophthalmology has now expanded to six clinical facilities across Philadelphia and Delaware County: the Scheie Eye Institute at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, the Scheie Eye Satellite in Radnor, the Scheie Eye Satellite in Media, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and the Veterans Affairs Medical Center of Philadelphia of Philadelphia. The Department is dedicated to providing superb eye care across the Philadelphia area. n

Historical giving: 1883-1995. (n.d.). Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania - Donor Recognition. Retrieved from https://www.med.upenn.edu/donorrecognition/historical-giving. html#DullesAgnew19414

History of Ophthalmology at Penn. (n.d.). Penn Medicine Department of Ophthalmology. Retrieved from https://www.pennmedicine.org/ departments-and-centers/ophthalmology/about-us/history

Hospital Evacuated as Firemen Battle Flames. (1937, February 25). The Philadelphia Inquirer, p. 3. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/ image/176106409/

Hospital Memorial to Titanic Victim. (1931, April 19). The Philadelphia Inquirer, p. 75. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/ image/173334477/

Leong, J. (2011, February 3). D. Hayes Agnew Memorial Pavilion. Penn Today. Retrieved from https://penntoday.upenn.edu/node/151694

Rain Goes Away for Topping Out at Eye Institute. (1971, May 18). The Philadelphia Inquirer, p. 3. Retrieved from https://www.newspapers.com/ image/180063213/?terms=scheie%20eye%20institute&match=1

Salowe, R., Mulvihill, K., & Laberee, N. (2019). Department Milestones: Looking Back on 145 Years of Ophthalmology. Scheie Vision. Retrieved from https://www.pennmedicine.org/-/media/academic%20departments/ ophthalmology/summer%202019/summer%202019.ashx?la=en

Sapega, S. (2020, February 28). Another “Look Back” at HUP. Penn Medicine News. Retrieved from https://www.pennmedicine.org/news/ internal-newsletters/hupdate/2020/march/another-look-back-at-hup

Sargent, B. (n.d.). Scheie Eye Institute Renovation. Archinect. Retrieved from https://archinect.com/bsargent/project/scheie-eye-instituterenovation

Scheie Eye Institute. (2018, March 16). BBLM Architects. Retrieved from https://www.bblm.com/project/scheie-eye-institute/

SCHEIE TODAY Modern image of the SEI. Courtesy of Ralph C. EagleA mole on the eye spontaneously grows into a large tumor, a doctor sacrifices his vision, and an infection is squeezed out of the eye. In this article, we look back at a small sample of noteworthy historical medical cases and surgeries in the Ophthalmology Department prior to the 1940s.

April 26, 1939: With blood dripping down her face from her left eye, a 50-year-old woman walked into the outpatient eye clinic at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP). When she was a teenager, she had noticed a dark spot on the sclera of her eye, on the nasal side of the cornea. The spot, called a nevus (like a mole on the eye), remained unchanged for over 30 years. When it suddenly began to grow, and then bleed, she knew it was time to seek help.

When she reached the clinic, her bloody eye was first irrigated with boric acid. The rinse dislodged a piece of black, hardened tissue the size of “the nail of the little finger,” which dropped from the upper eyelid, according to the treating physician Dr. W. E. Fry’s account of the case. After this, the bleeding stopped temporarily.

Unfortunately, the nevus—now a tumor—continued to grow. After her eye hemorrhaged again, the patient was admitted to HUP and underwent surgery. In surgery, Dr. Fry discovered that the tumor occupied most of the nasal portion of the orbit, and he was forced to perform an exenteration. In addition to the eyeball, the surrounding muscles, fat, nerves, and eyelids were removed to increase the chances that the entire malignant tumor was excised.

Microscopic examination of the tumor revealed malignant melanoma. Thankfully, Dr. Fry was able to remove the whole tumor, and the patient’s melanoma did not metastasize.

June 30, 1936: Julius Comroe, MD was finishing up the last day of his internship at UPenn. He was assigned to an outpatient with an eye infection, and Dr. Comroe advised the patient to return for a followup if his condition worsened.

The next day, the patient returned to the eye clinic, where he was admitted as an inpatient and diagnosed with conjunctivitis. Unfortunately, antibiotics, which are used

today to treat bacterial conjunctivitis, were not readily available in the mid-1930s. As a result, the contagious condition was particularly dangerous. The patient was strictly isolated.

Two days after his internship ended, Dr. Comroe, who had left Philadelphia and was now in Chicago, began experiencing similar symptoms. He promptly returned to UPenn to be treated by then-Chairman Thomas B. Holloway, MD.

Without viable treatment options, Dr. Holloway prescribed frequent irrigations of the eyes with boric acid and daily application of one percent silver nitrate. According to Harold G. Scheie, MD, who recalled this event in an interview with science historian Sally Smith Hughes, “The silver nitrate hurt like the devil but it was thought to be effective by causing so much irritation that the epithelial cells would slough off carrying the [bacteria] with them.”

Without the aid of antibiotics, Dr. Comroe lost one of his eyes in a matter of days. However, his other badly infected eye eventually fully recovered. Though he could no longer pursue surgery as he had hoped, he became an expert in physiology, cardiology, and pulmonology. He served as Chairman of the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at UPenn from 1946 to 1957, then founded the Cardiovascular Research Institute at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Comroe passed away in 1984 after dedicating his life to his patients and research.

Late 1880s to early 1900s: Trachoma, a bacterial eye infection that causes blindness, was considered granular conjunctivitis in the mid to late 1800s. By 1897, the United States government had enacted a law that prohibited those with trachoma to enter the country.

Despite this law, the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) continued to see cases of trachoma in the early 1900s, the cause of which was still unknown. In its acute form, the infection was treated primarily with topical medications like boric acid. In its chronic form, more extreme measures were taken; the use of caustics, astringents, and surgery were not uncommon.

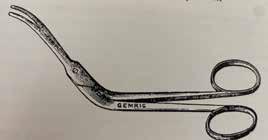

George E. de Schweinitz, MD, the second Chairman of Ophthalmology at UPenn, credited Jacob Hermann Knapp, MD for the invention of forceps that revolutionized surgery for chronic trachoma at the time. In the operating room, for one such case, Dr. de Schweinitz everted the eyelids and used the Knapp forceps to squeeze the conjunctiva “until all the morbid material … had been thoroughly milked.” The forceps allowed for quick expression with less damage to the eye than previous manual methods of treatment.

Today, trachoma is the leading cause of infectious vision loss in the world, though extremely rare in the United States. In its early stages, it is treatable with antibiotics. n

Adler, F. H., & Reese, W. S. (1941). College of Physicians of Philadelphia: Section on ophthalmology. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 26. https://doi. org/10.1016/s0002-9394(43)91863-x

Albert, D. M., & Scheie, H. G. (1965). A history of ophthalmology at the University of Pennsylvania. C.C. Thomas.

Scheie, H. G. Ophthalmology Oral History Series. A Link with Our Past. Sally Smith Hughes Foundation of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, 1988. “Julius H. Comroe.” A History of UCSF https://history. library.ucsf.edu/comroe.html

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Trachoma. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who. int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/trachoma

Over the years, the Department has seen many patients amaze with their incredible talents. Our care team provides high quality treatment to allow patients to continue to do what they love. In this article, we feature three patients who, despite the constraints of limited sight, found passion and success in musical and visual arts.

In 2013, just two weeks after receiving a novel gene therapy for Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis (LCA), Christian Guardino sang to a transfixed audience. That night, he saw the moon for the first time and gained the confidence to become a star.

As an infant, Christian was diagnosed with LCA, a rare retinal degeneration. When he was 11, his vision began to deteriorate rapidly. His concerned mother, Beth, attended an LCA conference in Philadelphia, where she learned the sobering prognosis of LCA: without intervention, Christian could lose all of his sight. The following year, at the age of 12, he did.

Then, Christian and his mom met Jean Bennett, MD, who is Co-Director of the Center for Advanced Retinal & Ocular Therapeutics at the University of Pennsylvania and an expert in gene

therapy for retinal degenerations. Dr. Bennett was conducting a clinical trial on patients with LCA using a gene therapy (now named Luxturna) targeting the RPE65 mutation. Christian was eligible for the trial, and soon found himself in treatment with great success. Just two weeks later, he was staring mesmerized at the giant rock in the sky, about to sing to a teary audience.

The following year, Christian won the Grand Prize at the Apollo Theater’s Amateur Night at the Apollo in the “Stars of Tomorrow” category. Two years later, in 2016, he welcomed ice hockey fans with the national anthem at a NY Islanders playoff game and performed a duet with Jordin Sparks for Michelle Obama’s “Fit 2 Celebrate” Gala.

In 2017, at the age of 16, Christian stood on the stage of a packed concert venue in front of the judges of America’s Got Talent. His performance of “Who’s Lovin’ You” by The Jackson Five brought the audience and judges to their feet, left Simon Cowell

speechless, and prompted Howie Mandel to press the Golden Buzzer, sending Christian immediately to the quarterfinals. Christian also performed in the semifinals, again receiving a standing ovation from all four judges.

Just this year, in 2022, Christian successfully auditioned for American Idol, a show he had followed his entire life. The judges were in awe of the range and depth of his voice, and of Christian himself. His performance of John Lennon’s “Imagine” brought Katy Perry to tears. “I didn’t hear anything but perfection,” raved Luke Bryan. The sheer power of Christian’s voice in his performance of “Circle of Life” from The Lion King was breathtaking.

Of over 100,000 auditioners, Christian was a Top 7 Contestant in Season 20 of American Idol.

Now, thanks to the research-scientists at the Scheie Eye Institute, Christian can see the gaping audience as he performs.

Christian Guardino performs on America’s Got Talent in 2017. Photo credit: Trae Patton/NBC/NBCU Photo Bank/Getty Images.98-year-old Hilda Friedman was born an artist. As a child, she gained practice drawing her favorite muse, her grandmother’s cat. Hilda grew up alongside her three sisters during the Great Depression, and she attended South Philly High School. After receiving a full scholarship, she earned her bachelor’s degree from William Smith College.

Despite initial doubts from her family,

Like Hilda Friedman, Bernice Paul was destined to be an artist. Born in Moscow in 1917, she immigrated to the United States in the 1930s. She settled in Philadelphia, where she studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the Philadelphia College of Art, the Barnes Foundation, and the Fleisher Art Memorial.

Bernice especially loved to paint flowers and landscapes in the summertime, and she enjoyed art as a social activity. “I rarely paint alone; I most enjoy painting with friends,” she told former medical writer Nora Laberee in an interview in 2020. She went with her daughter to art studios in Philadelphia to meet others

Hilda chose to pursue art after college, and studied drawing at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University in the 1950s. While at Temple, Hilda became interested in color and began working with watercolors and printmaking as media. Interested in furthering her education and honing her skills, Hilda studied lithography and printmaking at the Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, silkscreening at the Fabric Workshop, and art history at the Barnes Foundation. While educating herself, she taught her own students in classes at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Wayne Art Center, and St. Joseph’s University.

who liked to paint.

Do not be fooled: Bernice’s art was not simply a social pastime. She earned many awards, including a gold medal from the Philadelphia Sketch Club, gold and silver medals from the Plastic Club, first prizes at the Upper Merion Cultural Center, and Best in Show at the Main Line Center of the Arts.

As Bernice aged, she began to suffer from macular degeneration, the leading cause of vision loss in the United States in individuals over 65 years old. Bernice came to the Department as a patient under the care of Albert Maguire, MD and Ranjoo Prasad, MD.

Though she was losing her eyesight, Bernice’s passion for art was unfaltering.

Kikut, A. (July 2018). Like Watching a Miracle. Scheie Vision Laberee, N. (July 2019). Still Painting After 102 Years, Despite Vision Loss. Scheie Vision Salowe, R. (December 2020). 96-Year-Old Patient and Artist Donates Paintings to Scheie. Scheie Vision

Hilda became a patient of the Scheie Eye Institute in the 1970s when she suddenly lost half of her field of vision. She learned that she had melanoma in her right eye and came to Scheie for further evaluation under the care of Harold Scheie, MD and William Frayer, MD. The doctors advised surgery, as her eye had to be enucleated. After surgery, Hilda was persistent about continuing her art.

Hilda’s later work used metal, a symbol of grief in Mexico. She was drawn to this medium in response to the loss of her husband, whom she married young and loved deeply.

In 2020, she donated three tremendous watercolor paintings to Scheie, which are on exhibit today in the second floor waiting room. The abstract art is charged with emotion, and the enormous size of the paintings—particularly unusual for watercolors—makes the detail more visible to patients. In Hilda’s current phase of work, she uses wood as a medium.

Hilda’s work is available for sale or placement in galleries and museums. Her work can be viewed at hildafriedman.com

The late Bernice Paul sits next to one of her beautiful floral paintings, which she donated to UPenn.

“My eyes are going now, but I still paint,” she told Laberee in their interview.

“There is a joy in painting, I love it.”

Bernice Paul passed away in 2021 at the age of 103. She spent her entire life, even despite vision loss, painting. n

By Isabel Di Rosa

By Isabel Di Rosa

Left: Ali Haasz prior to surgery.

Right: Ali Haasz four weeks after surgery. before after

Alexandra “Ali” Haasz had almost given up on her vision before seeking help at the Scheie Eye Institute. She had previously undergone four surgeries at other eye institutes with little improvement.

When she was born, Ali was diagnosed with strabismus, commonly referred to as crossed eyes. She underwent her first operation prior to her first birthday, which was unsuccessful and resulted in exotropia in both eyes. Exotropia is an eye misalignment that causes the eye to deviate outward.

While Ali was extremely insecure due to her condition, her parents were incredibly supportive of her. Her father drew eyes on the patches that Ali sometimes wore when she was not donning her glasses with prisms. Her parents took her to vision therapy and countless doctors’ appointments. Ali had three surgeries prior to entering high school.

The surgeries, while not as life changing as she had hoped, allowed Ali to learn to control each eye independently or both if she concentrated. “To use both of my eyes together, it felt like I was holding a dumbbell and I was halfway through a bicep curl,” Ali explained. This tension caused severe headaches.

“Everything from my sleep to my selfesteem was adversely affected [by strabismus].” Through young adulthood, Ali wore sunglasses and heavy eye

makeup, and she avoided cameras and eye contact. Explained Ali, “I have always had tremendous insecurity and shame over my lazy eyes.”

When she turned 30, she decided she was ready to pursue treatment again. She had a fourth surgery that was not only unsuccessful, but also caused significant regression. She could no longer move both eyes at the same time. “I was in a place of total devastation,” Ali remembered. When she returned home, she prayed. “These are my eyes. This is important!” she cried.

Ali wanted another opinion. She started researching and discovered the Scheie Eye Institute and Madhura Tamhankar, MD. “During my initial consult with her, she literally said those words: ‘These are your eyes. This is important!’ I almost cried,” Ali recalled.

After considering the risks of a fifth surgery, without knowledge of what she would discover until the operation began, Dr. Tamhankar was still willing to take on the case. She recognized the limiting effect strabismus had on Ali’s life.

Ali was impressed by Dr. Tamhankar’s diligence in gaining as much background information as possible to prepare for the operation. In August 2022, Dr. Tamhankar performed Ali’s fifth eye surgery.

“All I saw for the first 40 minutes of surgery was scar tissue,” Dr. Tamhankar recalled.

“I have never seen so much scar tissue in an eye surgery—to the point where it was completely covering the muscle.” Because eye muscle and scar tissue are sometimes intertwined, Dr. Tamhankar had to dissect the scar tissue with extreme precision. She considered stopping the surgery; with the muscle nowhere in sight, it might be too weak or too entangled within the scar tissue to safely operate on. However, Dr. Tamhankar continued to work, aware that after a fifth surgery, it would be difficult for Ali to find another surgeon willing to operate. “If I don’t fight for her, who is going to?” Dr. Tamhankar remembered thinking.

After 40 minutes of dissecting scar tissue, Dr. Tamhankar finally found the muscle: “That was my first glimmer of hope.” She was then able to complete the surgery successfully using adjustable sutures, which allowed her to tweak the alignment of Ali’s eyes immediately after surgery. This ensured perfect alignment.

At the time of the interview, it had been two and a half weeks since the surgery and the results had already increased Ali’s confidence tremendously. “I can connect with people in deeper ways… just in the past two weeks [since surgery],” Ali remarked. Eye contact played a large role in this.

“My eyes are straight,” Ali laughed with joy. “They’re completely straight. It surprises me every time I look in the mirror.” n

These are my eyes. This is important.”

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak a global pandemic. Since then, the city of Philadelphia has experienced more than 350,000 cases and 5,200 deaths. Unfortunately, COVID-19 was not the first virus to wreak devastation on the city. Below, we examine the outbreaks of yellow fever in 1793 and influenza in 1918 in Philadelphia. Like COVID-19, both outbreaks led to swift and unprecedented responses from the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn)—including our ophthalmologists.

Called the “American Plague” at the time of its outbreak, yellow fever was an acute viral hemorrhagic disease caused by a virus in the family Flaviviridae. The virus caused symptoms such as high fever, internal bleeding, vomiting of blood, and jaundice (leading to the name “yellow” fever). Philadelphia, which was the nation’s capital at the time, had the highest death toll of all cities in the United States.

During the summer of 1793, yellow fever spread like wildfire throughout Philadelphia. The origins of the virus and its mode of transmission (mosquitoes) were unknown at the time, fueling fear and panic. More than 20,000 people fled the city and sought safety in the countryside, including Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and Alexander Hamilton.

A 19th-century image depicting the final stages of yellow fever. Courtesy of Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons.

Those left behind (often without the means to travel) described the city as being eerily quiet and desolate. Mass graves were scattered around the city, with families buried together. Carriages were driven through the streets, with shouts for families to bring out their dead—a practice not seen widely since the Black Death of medieval Europe.

The mass exodus from Philadelphia during the epidemic included many of the city’s physicians. The few who remained were mystified and increasingly desperate to find effective treatments. Even the 16-member College of Physicians was divided on how to treat the virus, with some advocating for more aggressive therapies that bled and purged patients, and others supporting milder remedies such as cold baths.

Like all hospitals at that time, Philadelphia Hospital closed its doors to yellow fever victims to protect its existing inpatients. A temporary hospital was opened by the Guardians of the Poor at Bush Hill, an estate outside the city, but was desperately understaffed. In The Story of Philadelphia, author Lillian Rhoades commented: “The hospitals were in a horrible condition; nurses could not be had at any price . . . nearly every bed contained a dead body, and the floors reeked with filth.”

Benjamin Rush (1746-1813). Retrieved from University of Pennsylvania Archives.

Philip Syng Physick (1768-1837). Retrieved from University of Pennsylvania Archives.

The care of thousands of sick patients thus fell to the few physicians who valiantly refused to flee the city. Among these physicians were two professors from UPenn: Benjamin Rush, MD and Philip Syng Physick, MD. Both worked tirelessly with yellow fever victims, attempting to save as many lives as possible.

The Arch Street Ferry is believed to be the entry point of yellow fever into Philadelphia in 1793. Courtesy of Independence National Historical Park via Wikimedia Commons.Dr. Rush, Professor of Medical Theory and Clinical Practice at UPenn, was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a founder of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. He was among the first to identify the disease affecting city residents that summer as yellow fever. He worked closely with Dr. Physick, who had just returned from medical school in Edinburgh. Dr. Physick later became a Professor of Surgery and Anatomy at UPenn who specialized in ophthalmic procedures. Though the Ophthalmology Department was not officially founded for another 80 years, he was undoubtably a leader in the field at that time, earning the name “Father of American Ophthalmology.”

Drs. Rush and Physick worked closely with yellow fever victims, taking careful notes and performing frequent autopsies in the hopes of understanding this deadly virus. Both supported a controversial approach to treating yellow fever, including blood leeching and purging patients, as well as administration of mercury. They reported that this treatment regimen was highly effective if administered early. When Dr. Rush fell ill with the virus on two separate occasions, he applied this treatment method to himself and recovered. Similarly, when Dr. Physick contracted yellow fever, he later credited his survival to Dr. Rush’s treatment of bleeding and purging.

However, some colleagues believed that these treatments were applied too excessively and without discrimination. Dr. Rush also came under fire for his theory that the virus was spread by putrid exhalations in the atmosphere from unsanitary conditions and rotting food at city ports, angering proud Philadelphians. He was correct, however, that the virus did not spread through human-tohuman contact. His accounts on the fever in books and lectures, as well as private letters, were widely read and cited.

Today, many regard both physicians as heroes for their utter devotion to patients at a time when most physicians fled the city to protect themselves.

In late October 1793, the frost finally killed the mosquitoes in Philadelphia, bringing an end to the deadly epidemic. It is now estimated that more than 5,000 people in Philadelphia died between August and November of 1793 from yellow fever, which was 10% of the city’s population at the time.

Though an effective vaccine was developed in 1938, yellow fever still kills approximately 30,000 people each year. Ninety percent of these individuals live in Africa.

Philadelphia

Retrieved

Philadelphia had a staggering death toll from influenza. Retrieved from National Museum of Health and Medicine.

In 1918 and 1919, a deadly influenza pandemic spread worldwide, ultimately resulting in more deaths than World War I. This outbreak was caused by a H1N1 influenza A virus with genes of avian origin. Many individuals experienced relatively mild flu symptoms, especially during the first wave of disease. Later waves of a more virulent strain of the virus were far more deadly, with many individuals developing complications such as bacterial pneumonia. Unlike yellow fever, the virus was transmitted person to person through airborne respiratory droplets.

The influenza pandemic broke out in 1918 near the end of World War I. Though the exact origin of the virus remains unknown, it is believed that American troops returning from Europe inadvertently brought a more virulent form of influenza back to ports in Philadelphia and Boston. Within a matter of days, 600 sailors caught the disease. The virus soon spread from these port cities across the country.

On September 28, 1918, Philadelphia hosted the Fourth Liberty Loan Campaign rally to raise funds for the war effort, bringing together more than 200,000 Philadelphians. It is now believed that this rally contributed to the deadliest period of illness in the city.

With an unnerving similarity to the yellow fever pandemic, bodies began to pile up in makeshift morgues and in the streets. The frantic public stripped medications from the shelves of pharmacies, or resorted to buying folk remedies in the streets. Unlike most influenza strains, this outbreak had an unusually high mortality rate for healthy adults between the ages of 20 and 40, rather than the very young and old.

Liberty Loan’s Parade on Broad Street gathered more than 200,000 Philadelphians, contributing to the rapid spread of the virus.

from U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command – Smithsonian.

Liberty Loan’s Parade on Broad Street gathered more than 200,000 Philadelphians, contributing to the rapid spread of the virus.

from U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command – Smithsonian.

The influenza epidemic overwhelmed city hospitals, with Philadelphia General Hospital and Hospital of University of Pennsylvania (HUP) receiving an unprecedented influx of patients. Beds were added to waiting rooms to accommodate the mounting number of patients. At this time, the Ophthalmology Department was located in HUP and thus was closely involved in treating patients.

Compounding the problem of hospital overcrowding was the severe shortage of health care professionals at HUP and throughout the city. More than 25% of physicians and nurses were called away to serve the war effort—and up to 75% of hospital medical and surgical staff were overseas. Among the physicians overseas was the then-Chairman of the Ophthalmology Department, George de Schweinitz, MD, who was serving in a field hospital in France.

This absence of vital medical personnel left the city unprepared to contain the virus and care for the sick. In addition to understaffing, there was also uncertainty about how to best treat the virus. There were no antiviral drugs or antibiotics for secondary bacterial infections, and the most common prescription filled for patients was whiskey.

The physicians who remained in Philadelphia were devoted to fighting the virus and saving lives. The Ophthalmology Department and other medical specialties at HUP re-focused all effort on treating influenza patients, with the exception of emergency surgeries. The entire hospital was put under strict quarantine with no visitors permitted. Even individuals without medical experience volunteered to clean facilities, dispose of dead bodies, or operate soup kitchens.

A significant portion of care also fell to medical students, nurses, and volunteers, who played a vital role in staffing hospitals. Penn medical students staffed 19 hospitals in Philadelphia, with only one lecture on influenza to guide them. The Student Army Training Corps, which had been established to provide trained officers for the war effort, also played a large role in curtailing the virus’s spread. They commandeered two fraternity houses at UPenn to use as emergency hospitals.

Nurses at HUP and other overflowing hospitals worked around the clock to care for patients. Many treated the thousands of sick who could not reach a hospital, describing horrors such as entering houses where every member of the family was dead. Many heralded the nurses and medical workforce as heroes and saviors, while others shunned them because they wore white gowns and masks.

Regardless of the public’s opinion, the medical workforce and volunteers risked their lives to care for influenza patients. Large numbers contracted the virus during their work. For example, first-year nursing students at UPenn were encouraged to return home rather than face the disease, but all chose to stay and work in hospitals. Six eventually died from the virus.

The

The severity of the influenza outbreak waned quickly in Philadelphia. By late October 1918, most quarantines at UPenn and in Philadelphia were lifted. A plaque was dedicated at HUP to all the nurses who died during the pandemic. However, the heroic efforts of the medical workforce and volunteers were largely overshadowed by the war.

Though estimates vary, it is believed that more than 50 million people died from the virus between 1918 and 1922, roughly half of whom were between the ages of 20 and 40. Philadelphia had approximately 500,000 cases and 16,000 deaths.

Influenza pandemics caused by novel influenza strains have occurred every 10 to 50 years since the late 1800s. Today, new versions of influenza vaccines are developed twice per year because the virus rapidly mutates. A universal flu vaccine that is effective against all influenza strains and does not require yearly modifications is currently the subject of much research. The first in-human trial with such a vaccine was launched in 2021.

Today, we know first-hand that pandemics remain a global threat. Almost three years have passed since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in March 2020. As in past pandemics, ophthalmologists and trainees at UPenn were quick to volunteer to help patients, working in triage tents and at testing sites throughout Philadelphia.

In 2022, an article was published in Clinical Ophthalmology outlining the successful recovery strategy of the UPenn Ophthalmology Department in response to the coronavirus pandemic. In this article, Joan O’Brien, MD, Benjamin Kim, MD, and Madhura Tamhankar, MD described the innovative metrics and initiatives developed by recovery ad hoc committees, allowing a safe recovery of patient and surgical volumes after seven months. The actions described in this article can help provide a blueprint for the response of academic departments and clinics to future pandemics.

Most of all, we must never forget to look to the self-sacrifice, courage, and innovation of ophthalmologists, physicians, and trainees during these pandemics. They serve as examples of the strong and compassionate approach needed in medicine in times of crisis. n

Armstrong, J. (2015). Philadelphia, nurses, and the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918. Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved from https:// www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-listalphabetically/i/influenza/philadelphia-nurses-and-the-spanish-influenzapandemic-of-1918.html

Barry, J.M. (2004). The Great Influenza: the story of the deadliest pandemic in history. New York, New York: Viking Press.

Brodin AC, Tamhankar MA, Whitehead G, MacKay D, Kim BJ, & O’Brien JM. (2022). Approach of an Academic Ophthalmology Department to Recovery During the Coronavirus Pandemic. Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ), 16, 695.

Crosby, M. C. (2006). The American plague: The untold story of yellow fever, the epidemic that shaped our history Berkley Books, New York: Berkley.

Gammon, K. (2018). Flu Forward 1918 | 2018. Penn Medicine Magazine.

Gum, S.A. (2010). Philadelphia under siege: the yellow fever of 1793. Retrieved from https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/ feature-articles/philadelphia-under-siege-yellow-fever-1793

Hingston, S. (2016). 11 Things You Might Not Know About Philly’s 1793 Yellow Fever Epidemic. Philadelphia Magazine.

Lynch, E.A. (1998). The Flu of 1918. The Pennsylvania Gazette.

Rhoades, L. (1900). The Story of Philadelphia. New York, Cincinnati, Chicago: American Book Company.

University Archives & Records Center. (n.d.). Benjamin Rush. Retrieved from https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/benjamin-rush

University Archives & Records Center. (n.d.). Penn and the 1918 Influenza Epidemic. Retrieved from https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/flu

University Archives & Records Center. (n.d.). Philip Syng Physick. Retrieved from https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/philip-syngphysick.

Since the Revolutionary War, physicians, nurses, and medical trainees from the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) have served in most major conflicts in our nation’s history. Because the U.S. Armed Forces lacked a strong medical infrastructure of their own until the second half of the 20th century, the medical community at UPenn—including ophthalmologists—played a major role in providing care during conflict. Physicians and nurses led field hospitals, treated the wounded on battlefields, and developed new technologies on the home front. Nowhere were these contributions more impactful than during World Wars I and II.

World War I broke out among European nations on July 28, 1914. Though the United States officially maintained a neutral position for three more years, physicians and nurses at UPenn began to volunteer for service on behalf of the Allies. In 1915, a group of these physicians and nurses travelled to Europe and took over leadership of the American Ambulance Hospital in Paris.

Back on campus, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) set aside 250 beds for special use by the Army and Navy. Medical students enrolled in courses that would prepare them to treat heavy combat injuries. They were also taught operative surgery on cadavers and neurological diagnostics to assess trauma and shock. Students and faculty formed battalions, and all male medical students were inducted into the Students’ Army Training Corps.

Medical faculty also pursued research projects to support the war effort during these years of neutrality. Eye surgeon Hunter Scarlett, MD (1911 Penn Medicine alumnus), along with Frenchman Dr. Georges des Jardins in the American Ambulance Service, discovered a microbe that caused gangrene to develop in bullet and shrapnel wounds. This discovery led to work at the Pasteur Institute to create a serum for injection of patients on the battlefield, which helped to prevent unnecessary amputations and death.

By the time the United States entered the war on April 6, 1917, approximately 40% of the medical faculty at UPenn had enlisted in the service. Their contributions were far-reaching and impactful. Over the course of the war, these physicians

Ambulance at Base Hospital No. 20.

Retrieved from University of Pennsylvania Archives.

and nurses led three Ambulance Units, several Red Cross units, and various detached units to support the war effort. Their largest contribution, however, was the organization and leadership of Civilian Base Hospital No. 20, which later became the largest field hospital in World War I.

UPenn began preparations to lead this field hospital back in 1916, working with the American Red Cross and War Department. In 1918, the members of Civilian Base Hospital No. 20 set sail for France when called into active service. All chief medical officers were from UPenn’s medical school and hospital, and many general staff members were Penn medical students.

The field hospital was operated out of hotels in France for a period of eight months, with patients continuously arriving from hospital trains. In total, they saw 75,000 patients, including 4,000 surgical cases and 3,500 medical and gas patients. Of note, only 65 patients died, which was an incredible feat for that time period.

When patients first arrived at the field hospital, they were classified by disease or injury and organized into separate wards, including a designated area for ophthalmic injuries. The majority of patients were American, but French soldiers and German prisoners were also seen. Though the field hospital mostly treated battle causalities and disease, they also became known as one of three observational hospitals for tuberculosis, and had unusual success dealing with the influenza pandemic.

There was a staggering number of eye injuries during World War I, necessitating the creation of an Eye Department at Civilian Base Hospital No. 20. It consisted of a ward of 40 beds, a dark room, an operating room, and an outpatient dispensary.

British soldiers temporarily blinded by mustard gas. Courtesy of Imperial War Museums (collection no. 1900-22).

The then-Chairman of the Ophthalmology Department at UPenn, George E. de Schweinitz, MD, served in this Eye Department. When the United States entered the war, he was appointed as lieutenant-colonel in the Medical Reserve Corps. Among his many contributions, Dr. de Schweinitz is credited with generously providing much of the ophthalmic equipment used in this field hospital. He also served on the Committee of the Office of the Surgeon General, which was responsible for introducing specialties into the Army Medical Corps, and founded the Army School of Ophthalmology at Fort Oglethorpe. He was the only ophthalmologist or otolaryngologist to attain the rank of colonel during World War I.

Dr. de Schweinitz and other ophthalmologists faced enormous challenges at the field hospitals. The quantity and severity of eye trauma was unlike anything seen in prior wars. New types of weapons such as grenades, shells, and shrapnel produced chips that often projected into the face and eyes, causing severe trauma. Combat eye protection was scarce during the war, leaving the eyes especially vulnerable. Treatment usually involved enucleation or palliative care, or plastics operations if patients did not require immediate transport back to the United States.

World War I was also marked by increased use of chemical agents, especially mustard gas. Affected soldiers suffered from photophobia, tearing, and kerato-conjunctivitis with temporary visual incapacity and blindness. Typically, only the most serious cases were sent to the eye ward, while the milder cases were treated in the general wards or outpatient dispensary.

As a result of his outstanding service during the war, Dr. de Schweintiz was appointed as Brigadier General in the Medical Reserve Corps in 1922. He was also part of the medical care team called to treat President Woodrow Wilson after a stroke.

The Allies signed an armistice with Germany on November 11, 1918. In total, it is estimated that over 116,000 American soldiers died during World War I. An additional 800,000 became blind in one or both of their eyes during the conflict.

As in World War I, faculty and students at UPenn were actively engaged in preparations for the war before the United States had officially entered the conflict. During this time of neutrality, the University created a number of training programs across schools and implemented extensive security and safety measures, including first aid stations across campus. The Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) on campus, which had added a medical unit after the First World War, was very active in these preparations.

The medical school accelerated its curriculum from four years to three years to aid the war effort. Medical students served in the ROTC and underwent regimented military training. The students began their military service as privates and were promoted to private first class the following year.

During this time, a number of medical faculty were asked by the government to carry out war-related research projects. For example, the then-Chairman of the Ophthalmology Department, Francis Heed Adler, MD, directed an investigation at UPenn on the mechanisms and treatment of mustard gas injuries to the eye. In later years, Alfred Newton Richards, PhD, Chairman of the Pharmacology Department, spearheaded the mass production and distribution of penicillin, which saved countless lives.

In December 1941, the United States officially entered World War II following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Several medical alumni from UPenn led the treatment of the wounded on the Hawaiian Islands in the aftermath of this attack. Over the following years, more than 17,000 faculty, staff, students, and alumni from UPenn joined the armed forces. A total of 362 individuals never returned home.