The City gives wild-looking native gardens the axe

Play program faces the challenge of street violence

OCTOBER

TOWARD A SUSTAINABLE PHILADELPHIA

Bernard Brown writes the book on Philly nature

AND CULTURE ISSUE

OCTOBER

TOWARD A SUSTAINABLE PHILADELPHIA

Bernard Brown writes the book on Philly nature

AND CULTURE ISSUE

People with disabilities sue the City for flagrant violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act

2022 / ISSUE 161 / GRIDPHILLY.COM

STREETS

OUT CUT

NOVEMBER 6, 2022 11AM – 4PM KIMBERTON FAIRGROUNDS Phoenixville EPIC FARMERS MARKET With over 100 local farmers & makers @goodfarmsgoodfood TICKETS & MORE www.goodfarmsgoodfood.com GROWING ROOTS BROUGHT TO YOU BY PREMIER SPONSOR

PLAN YOUR TRIP AT ISEPTAPHILLY.COM

publisher

Alex Mulcahy

director of operations

Nic Esposito

associate editor & distribution

Timothy Mulcahy tim@gridphilly.com

copy editor

Sophia D. Merow

art director

Michael Wohlberg

writers

Kiersten Adams Marilyn Anthony

Bernard Brown

Nic Esposito Constance Garcia-Barrio Lindsay Hargrave Dawn Kane Kait Moore

Logan Welde

photographers

Chris Baker Evens

Nic Esposito Kait Moore

Alex Mulcahy

illustrators

Malachy Egan

published by Red Flag Media 1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107 215.625.9850

GRIDPHILLY.COM

by alex mulcahy

Other Routes?

Hello Readers, Bernard Brown submitted this es say to Grid, and I thought it made for a perfect in troduction to the new issue. I’ll be back next month!

Iswim laps at the West Philadelphia branch of the YMCA, on Chestnut be tween 51st and 52nd. My walk there takes me across Walnut Street, often on the east side of the intersection with 51st Street. I can’t recall when exact ly I first noticed that the ADA-compliant sidewalk ramp facing Walnut Street at the northeast corner of the intersection was missing, but I reported it on the City’s 311 system in February 2018. In place of the ramp was dirt and gravel. The ramp had apparently been removed for utility work, but no one had come back to replace it.

The 311 system shifted the ticket to “In Progress,” notifying me that “this means that Philadelphia is actively working to solve the issue.” On March 12, 2018 I got another email saying that the Streets De partment had closed the case.

I got excited. I, an engaged citizen of Phil adelphia, had reported a problem, and then the government, funded by my tax dollars, had responded by solving it!

But of course that’s not what happened. This is Philadelphia.

The sidewalk ramp was just as missing as it had been before I submitted the complaint.

A few more months went by, and I resub mitted the complaint on 311: same result.

I cursed under my breath every morning I passed the place the ramp should be, and I winced each time I saw a wheelchair user cruise down the street, risking the traffic because they can’t use the sidewalks in our neighborhood.

As the years passed, I tried other routes. In May 2019 a 311 call center representative suggested I reach out to the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities. Someone from that office actually called me back to say that he was working on it, but that was the last I

heard from them.

I tried my then-district-councilmember Jannie Blackwell’s office, but they didn’t get it fixed either.

In 2020 Jamie Gauthier replaced Jannie Blackwell as my district councilmember. I quickly messaged her about the broken ramp. She replied that she’d have a constituent ser vices staffer get back to me, but they never did. In early 2022 I tried one of her staffers directly. He wrote back saying that he knew exactly the ramp I was talking about, and that he’d reach out to the Streets Department. I didn’t hear back from him after that.

This is how much the City cares about dis ability access: Enough to bury 311 requests, sometimes just enough for a staffer to call you back or say they’ll work on it, but not enough to actually fix a problem.

There might be good reasons why this ramp is difficult to fix. The ramp is sand wiched between a utility pole and a tree. Also I’m sure it’s a pain to just fix one ramp when the work crews would rather install several at a time, say as a road is resurfaced. But none of that relieves the City of its obligation under the ADA — or just basic civic decency — to provide disabled residents a safe way to get on and off the sidewalk.

This month I wrote our cover story about the poor state of Philadelphia’s sidewalks and how the broken concrete, illegally parked cars, thoughtless construction obstructions, and dangerous (or missing) ramps make it difficult for tens of thousands of disabled Philadelphians to get around the city. The City is violating the Americans with Disabil ities Act every day it fails to fix these wide spread problems, which has led to a lawsuit from a group of disabled Philadelphians and disability rights organizations. These failures cover every corner of the city, including the broken sidewalk ramp at the northeast cor ner of Walnut and 51st in the Walnut Hill neighborhood of West Philadelphia, and we must do better.

EDITOR’S NOTES

ILLUSTRATED PORTRAIT BY JAMES BOYLE 2 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022 COVER PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

keep that

to factories, swimmers to sewage, insects to instruments,

clean?

how

water in the past—and

protected

challenges

face tomorrow.

We all live downstream. So how do we

water

From fish

learn

we've

our

the

we

sciencehistory.org/downstream Museum of the *Intentionally integrated and developmentally appropriate curriculum *Creating foundations for a lifetime of learning *Graduates that make a difference *Locally sourced organic lunch program Limited spots available for the 2022 -2023 School Year in our Early Childhood through 12th grade programs! Schedule your tour today! admissions@kimberton.org 610.933.3635 ext. 108 In the race to net zero, there’s no second place. Voted Best Alternative Energy Company in Philadelphia and awarded the Pennsylvania Governor’s Award for Environmental Excellence. District energy steam is a low-carbon, reliable, clean solution for combating climate change and meeting commercial and institutional decarbonization goals. For more information about our Clean Energy Future Roadmap, visit www.vicinityenergy.us or email info@vicinityenergy.us.

Farm Party

Good Food Fest returns for a fun-filled day at the Kimberton Fairgrounds by nic esposito

After a two-year, covid induced hiatus, local food event Good Food Fest is set to return.

“We’re passionate about local food and supporting our growers and makers,” says Christy Campli, owner of event organizer Growing Roots Partners. “Good Food Fest is a way to celebrate, sup port and build awareness around the im portance of local agriculture.”

Campli explains that the Good Food Fest aims to attract people who may not go to the farmers market every week but who might be enticed to come out for a big food festi val. Since it is held in a rural setting, Campli feels that Good Food Fest brings the people to the farm, gives them what she calls “the real deal.”

In addition to the hundreds of farmers

selling their goods, this one-day event also includes a full schedule of activities such as culinary demonstrations; a Pouring Room featuring local brewers, cideries and dis tilleries; food trucks; live music by Berks County band Frog Holler; kids activities; and live farm animals.

Growing Roots Partners, which organiz es Good Food Fest, is a Pennsylvania-based farmers market coordinator that was found ed in 2011 by Lisa O’Neill to cultivate com munity through events that empower local businesses, farmers and artisans. In 2021, O’Neill retired and passed on the leadership of Growing Roots Partners to Campli, an alum of Wyebrook Farm in Honey Brook, Chester County.

Growing Roots Partners currently op erates three farmers markets in Malvern,

Downingtown and Eag leview, as well as one in West Reading, Berks County.

The event is sponsored by local food champions

Kimberton Whole Foods, a family owned and operated independent market that has grown to seven stores since opening in 1987.

“We currently work with over 200 producers in the Greater Philadelphia Area, and this event will serve as an opportunity to educate the community on the wide range of products that are avail able in our region,” says Terry Brett, found er and CEO of Kimberton Whole Foods.

Campli happily notes the many connec tions within the scene and, as a result, the event. For example, not only is Frog Holler one of her personal favorites, but one band member is married to a farmer who is part of the Growing Roots Partners network. And in the Pouring Room, Growing Roots partnered with Suburban Brewing Compa ny to exclusively use Pennsylvania-grown ingredients to produce a signature lager just for the fest. For Campli, it’s these con nections that make her work so fun and meaningful.

“I’m just excited for the opportunity to showcase our local growers and farmers and food producers in a way that’s fun and that there’s something for the whole family.”

Good Food Fest will be held on November 6 from 11 a.m. – 4 p.m. at the Kimberton Fairgrounds at 762 Pike Springs Road in Phoenixville.

Vendors from Pheonixville’s Sankanac CSA sell their produce at the 2019 Good Food Fest.

4 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022 GOOD FOOD FEST food

Actually Doing It

Weavers Way Co-op incubator shepherds diverse products onto shelves by dawn kane

Ask candy bermea-hasan to tell you about the diverse sellers program she’s building at Weav ers Way, a member-owned coop erative grocery, and her words spill out like water. For two years, Ber mea-Hasan has been recruiting fledgling producers and helping them find their way onto retail shelves. The work isn’t just about building a more diverse list of ven dors, she said. “I don’t want to just do it on paper. I actually want to do it.”

Weavers Way has always been open to diversity, but in recent years management decided that being open to it wasn’t enough; they wanted to provide opportunities to di verse producers. So they created a vendor diversity coordinator position, provided a budget and started interviewing. Ber mea-Hasan, who has worked in finance at the co-op since 2014, put in her application and found her passion.

After two years of doing this work, Bermea-Hasan is determined to do more — not just for sellers, but for customers as well. She identifies as a Native American Muslim, and she pushes for diverse custom ers to have options. She recalled a moment at a product fair when a vendor from India introduced a sauce-like condiment called lonsa. “People were so excited to find it. They said that they hadn’t been able to find any since they left India.”

Bermea-Hasan wants that kind of con nection to become the norm. While it’s one thing to get diverse products on the shelves from established sellers, like black hair-care products sold by Pattern Beauty, it’s quite another to help new sellers become retail ready. To do it, she created the incubator program and became a mentor.

Bermea-Hasan finds new sellers through a referral process, but she won’t put their products on the shelves unless they meet her standards for quality. She ensures all prod ucts have acceptable ingredients, packaging and pricing. Then she brings in the co-op’s financial and social media resources.

BY CHRIS BAKER

Weavers Way, which has locations in Mount Airy, Chestnut Hill, and Am bler, offers further services to new sell ers. These include providing commercial kitchen space, funding their insurance and product packaging, and organizing vendor fairs. They bring in consultants, such as inspectors from the Department of Agri culture. Even so, the path to success isn’t guaranteed.

One of the biggest challenges, Ber mea-Hasan explains, is getting a new seller to make changes to a product that they think is ready to go. They need a “wow” factor, a more competitive price and attractive packaging, she said. “Nobody has the perfect brand to start. You have to be prepared to tweak your brand.” Sometimes she will spend hours and

hours after work on the telephone with a new seller to help them understand.

Beginning in November Bermea-Hasan is planning a new push to make sure new sellers get noticed. She will feature these vendors using in-store advertising, em phasize local connections and offer product demonstrations. A new retail manager will make sure sellers get noticed in all of their locations. Finally, they will give vendors more time to gain traction.

As Weavers Way prepares for its 50th anniversary next year, a new location in Germantown is also in the works, and Bermea-Hasan has customer needs on her mind. She knows the musician playing an acoustic guitar outside of the Mount Airy location might not work in Germantown.

“We have to consider what will appeal to the diverse families that live in that com munity,” she said.

“It’s a great program,” Bermea-Hasan said. Sixty percent of our budget goes to vendors, so we know it goes into their pockets. Will it make people wealthy? No. But it’s a good way to give back to the com munity.” ◆

We have to consider what will appeal to the diverse families that live in that community.”

—candy bermea-hasan, Weavers Way vendor diversity coordinator

Weavers Way vendor diversity coordinator Candy BermeaHasan stands outside the Weavers Way Across the Way store in Mount Airy.

OCTOBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 5

PHOTOGRAPH

EVENS

Bottom of the Barrel

As i write this, the rain has been at it for six hours, and the National Weather Service has issued a flood watch. Behind my house, the rain barrel, connected to a downspout draining the back section of the roof, is overflowing, with the excess water joining the rest of the block’s runoff in our sewer system, where it will flush raw sewage into the Schuylkill River.

The official — euphemistic — term for this is a “combined sewer overflow,” which happens because, in much of Philadelphia, the sewer system uses the same under ground pipes as the stormwater drainage system. In heavy rains, the sudden surge of stormwater running off the hard roofs, sidewalks and streets of Philadelphia over whelms the treatment system.

Along with work to dig up and separate some sections of the now-combined system, the City has been working to slow the flow of stormwater off of Philadelphia’s imper meable surfaces. This has been the goal of the Green City, Clean Waters campaign , which involves the use of trees and other plants, along with drainage features that di rect stormwater to them, to soak up some of the runoff.

My rain barrel would seem to help, filling up when it rains, and then letting the water out later, to be soaked up by the plants in my garden. But the more time I’ve spent using it, the less I think it has much of an impact.

For starters, the barrel takes in water from only part of the roof, and then only until it fills up. After that, the extra flow from the roof goes into the combined storm water/sewage system of our West Philly neighborhood, doing its little part to pol lute the Schuylkill River. It would take in more water if we were more dedicated about emptying it between rains, but these days

Do the rain barrels we see on Philly’s streets actually reduce stormwater runoff?

by bernard brown

Grid writer Bernard Brown’s rain barrel.

6 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022 BERNARD BROWN water

the plants we grow in the garden, which oc cupy three raised beds in the tiny space be hind our house (at 8 by 20 feet it feels like a stretch to call it a “backyard”), don’t require much extra water, and the barrel heads into most rainstorms already full.

And this is only during the growing sea son. From late September to April we don’t water anything at all, leaving all the precip itation for more than half the year to run straight into the drain.

I am not the only person who has won dered about the efficacy of rain bar rels. A study by researchers at Case Western Reserve University modeled the impact of rain barrels in suburban Cleveland, Ohio, and found they don’t end up slowing much runoff. Even assuming that homeowners used their rain barrels to water their gar dens whenever needed, they would save only 1.4 to 3.1% of total roof runoff. The same researchers then modeled the impact of rain barrel use in cities across the coun try to see how much they would reduce roof runoff. They found that the strongest reduction would be in the Southwest, where there is relatively little rain. As they put it,

“unfortunately, it appears that the rain bar rel–garden strategy would be most effective at reducing stormwater runoff in areas that need it least.”

In spite of the evidence that rain barrels don’t make much of an impact on stormwa ter runoff, it’s a strategy that remains pop ular. The Philadelphia Water Department’s Rain Check program distributes free rain barrels, for example, and they are a main stay in watershed organization program ming, perhaps because they are cheaper and easier to implement than features that do a better job at slowing runoff, such as green roofs or rain gardens

Other gardeners are more enthusiastic about their rain barrels. Bryn Ashburn wrote

to Grid to say that she highly recommends the free rain barrel she got from the City. “With the summer being so dry, I’ve been emptying it within days of the last rain.”

Rain barrels might come in handy for watering our plants, but I’ve accepted that there is not much we can do as individu als to solve the problem of combined sewer overflows. Our backyard isn’t big enough to work in a proper rain garden, and I don’t see a green roof in our immediate future either. I might keep the rain barrel through anoth er summer in case it comes in handy for watering plants again, but the real work in improving our city’s water quality is beyond the means of the typical Philly homeowner. This is the work of the government. ◆

…the rain barrel–garden strategy would be most effective at reducing stormwater runoff in areas that need it least.”

— case western reserve university study

OCTOBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 7

Good Natured

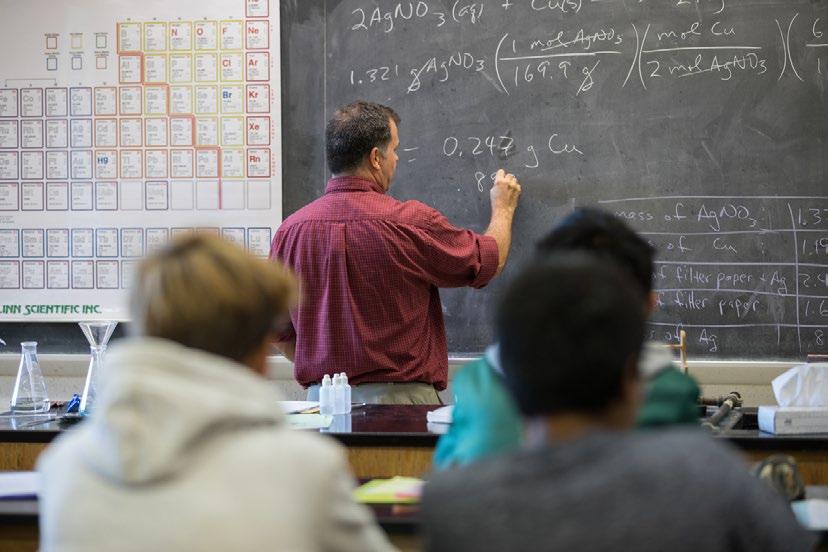

The new book from Grid ’s long-time naturalist aims to make your urban experience richer by alex mulcahy

Bernard brown wants to intro duce you to your neighbors. Not the human ones, but the flora and fau na that surrounds, or is accessible to, us city dwellers.

Brown, a longtime contributor to Grid, has been working the “Urban Naturalist” beat since 2009.

His first book, “Exploring Philly Nature: A Guide for All Four Seasons,” offers 52 invitations, one for each week of the year, to experience wildlife in familiar and un expected places. All chapters have an ac companying illustration by sustainability consultant and fellow Grid contributor Sa mantha Wittchen.

If you haven’t had the good fortune to read Brown’s illuminating and entertain ing contributions, it’s understandable if you ask: Hasn’t wildlife been essentially exterminated in major urban areas such as Philadelphia? Aren’t the squirrels, rats and cockroaches all that remain?

“You’re not entirely wrong,” Brown says, but though they are covered in concrete and asphalt, and roads prevent animal move ment, cities have a lot more biodiversity than, say, farmland devoted to soy or corn. “When you get down on your hands and knees, you see a decent variety of plants.”

Sometimes “Exploring Philly Nature” leads you to natural places you might know, like Bartram’s Garden, The Woodlands Cem etery, the John Heinz National Wildlife Ref uge at Tinicum or the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education. But sometimes there are discoveries to be made in your basement, or a crack in the sidewalk. “Every where is habitat, and habitat is everywhere,” Brown writes in the introduction, and that is the primary message of the book. Even when you are indoors, you are in nature.

“Exploring Philly” is a slim volume, de signed to be easily digestible, but there is a philosophical underpinning to the book, and it’s about attention. Where you direct your

attention is going to affect how you experi ence life. Brown is imploring us not to miss the opportunity to connect to the place where we live and the life forms we share it with.

you can hear a birdsong — or it can be a Baltimore oriole, or a wood thrush. You can see flowers — or you can see Philadel phia fleabane, or white snakeroot. “As you learn more about the components of those landscapes, it makes it so much deeper, and so much richer. Your brain can give them names, and figure out what they are.”

“Then you’ve got a story,” Brown contin ues. “You can learn about each one of these things. Every species, every plant, every an imal, every mushroom, has a natural history, and it has a story behind it. It’s kind of like looking at a bookshelf. Instead of just being like a bunch of vertical objects with writing on the spines, you’ve read these books.”

“And all of a sudden,” Brown says, “your walk down the sidewalk is that much more interesting every day.”

There’s a wide variety of plants and ani mals you can find using the book, including frogs, turtles, spiders and dog vomit slime mold (“one of the best names in all of na ture,” in the author’s opinion). Just as help ful, though, is the ecosystem of communities and clubs that meet to explore nature togeth er. For example, if dog vomit slime mold has piqued your interest, Brown recommends meeting up with the Philadelphia Mycology Club to go for a fungus-themed walk.

Through the years he says he has made some of his best friends in this circle of nat uralists, and he places a high value on the camaraderie of fellow explorers. “You can still always go out birding by yourself and avoid crowds if you want, but it can be a very social thing where you can go out and find other people birding and stop and ask them, ‘Hey, what are you looking at?’”

Brown’s evolution into an urban natural ist was not pre-ordained. Unlike his parents, Brown was always drawn to the outdoors, and he got his first pet snake when he was a seven-year-old living in Columbus, Ohio. He continued to collect reptiles and snakes until he went to college at Wesleyan University in Connecticut and decided to sell his collection.

Author and urban naturalist Bernard Brown admires a garter snake at Bartram’s Garden.

Author and urban naturalist Bernard Brown admires a garter snake at Bartram’s Garden.

8 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022 COURTESY OF BERNARD BROWN book review

After completing graduate school at Johns Hopkins University, he moved to Atlanta for a stint with AmeriCorps, and he resumed col lecting snakes. But things changed in 2004 when he moved to Philadelphia. Suddenly, discovering animals in their natural habitat seemed far more interesting.

“I think that the key shift was going from somebody who was really into keeping and breeding reptiles and amphibians as a hob by to someone who got much more interest ed in encountering them in the wild.”

Then, in 2009, he began writing for Grid and was tasked with documenting the nat ural world in the city.

“[My wife] talks about how she misses be ing in school. She loved college. And I kind of feel like I still am [in school]. Every month I have to research and produce a paper.”

After all these years, it seemed to Brown like it was time to gather all of that knowl edge in one place and write a book.

“‘Exploring Philly Nature’ was a lot of fun to write, because it’s all the recommenda tions I’ve been giving out informally over the years.”

Regular readers of Grid will also recognize Brown’s name from the investigative journal ism he’s been producing around open spaces, including the City-sanctioned deforestation of Cobbs Creek and the South Philly Mead ows. While Brown encourages us to have our radar raised so we can appreciate nature all around us, how does it feel for Brown to witness the whole sale destruction of larger ar eas of habitat?

“I’m going to quote Aldo Leopold, a famous ecologist, who wrote ‘A Sand County Almanac’: ‘One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds.’ You’re always recognizing what has been done and what’s being done to the stuff that you care about. I think it’s hard to be optimistic, sometimes, but I would say that the long view can help.”

Two things in particular help to keep Brown’s outlook positive, and the first is how quickly nature recovers.

“Cobbs Creek is a great example, or the Wissahickon. Mills used to be up and down the creeks everywhere. The trees would have been cut down, cleared multiple times for firewood or building. Yet you can walk in there now and feel like you’re in the for est primeval or something. But it’s really a

young landscape in the grand scheme of things, which means that eventually we can end up with something good again.”

The other comfort is how communities have rallied around when places they love have been taken from them.

“Cobbs Creek was an example. That golf course, it slipped through in a very secre tive way. And there are a lot of people who

would prefer not to see a golf course there. People who live in the neighborhoods, re gardless of their race and class, have gotten upset about these things and oppose them.

[The destruction] can be demoralizing, but there are reasons to moderate your disap pointment. We’ve got a community of folks that we can pull together to be more active in the future.”

◆

Cover design and illustration by Samantha Wittchen

Exploring Philly Nature was a lot of fun to write, because it’s all the recommendations I’ve been giving out informally over the years.”

— bernard brown

OCTOBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 9

Mow Problems

Sandi vincenti isn’t sure who called CLIP (the Community Life Im provement Program) on her native plant demonstration garden in Fish town, A Child’s Inspiration Wildlife Discovery Garden. She can think of two

possibilities. One is a developer interested in building on the plot. “The other assump tion is that we have two neighbors in some of the newer, more expensive houses in the neighborhood and maybe for them, it wasn’t what a garden is supposed to look like.”

“What a garden is supposed to look like,” however widely accepted, is an environ mental disaster. Nationally lawns suck up about 90 million pounds of fertilizer per year and 78 million pounds of pesticides. The EPA estimates that Americans use 9 billion gallons of water per day to irrigate lawns and gardens. Turf grass covers more than 63,000 square miles of the lower 48, about one and a half Pennsylvanias, which is three times more area than any irrigat ed crop. All this for something primarily grown to be looked at but not eaten.

And humans aren’t the only animals that don’t eat lawns. North American insects have generally not evolved to eat the Eurasian grass species that make up the lawn (even “Kentucky” bluegrass is originally from the Old World). The same is true of many of the other exotic (not from here) plants that gar deners favor. For our native critters, which didn’t evolve to eat the mostly Eurasian plants Americans garden with, the lawns and the trimmed privet hedges are pretty much blank spots on the landscape.

Native plant species, by contrast, fill in the landscape with a feast for the local bugs, which in turn feed birds, lizards, frogs and all the creatures that eat them. Plants that evolved to grow here can also do so without all the chemical support and irrigation that exotic plants rely on.

Above, hops grow in a lot across from Philadelphia Brewing Company. Left, PBC co-owner Nancy Barton in the same lot after CLIP razed their crops.

10 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022 INSET: PHILADELPHIA BREWING COMPANY urban naturalist

Lack of training in the City’s CLIP program leads to the destruction of gardens by bernard brown PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

These benefits have led increasing num bers of environmentally-minded gardeners to work with native plants. Certification programs have sprouted up as well, with the National Wildlife Federation, for exam ple, stamping its approval on Wildlife Habi tat gardens. The National Audubon Society promotes bird friendly yards, and the Penn State Extension certifies pollinator gardens The challenge is that a wilder-looking gar den might look untended to the uninitiated.

Neighbors fighting decades of disinvest ment can be legitimately concerned about neglect that invites trash dumping and crime, in some cases leading them to call the De partment of Licenses and Inspection’s code enforcement or CLIP on unconventional gardens. Code enforcement can issue fines, while CLIP teams respond to complaints by neighbors about vandalism, graffiti and unkempt vacant lots and clean up the mess.

In other cases hostile neighbors inten tionally weaponize these programs.

Derik Moore and his wife grow native plants such as black-eyed Susan, goldenrod, blazing star and pink muhly grass in their Roxborough garden. They were surprised to get a notice from code enforcement that their property was overgrown, and they would be subject to a $300 fine if they didn’t clean it up. “It was just a [bad] neighbor who we have had some conflicts with,” Moore says.

They invited an inspector to visit again. They gave him a personal tour of the gar den, which solved the problem. “He looked at it for two seconds, and he went, ‘Oh come on,’ and walked away,” Moore says.

The National Wildlife Federation offers several tips for native plant gardeners to avoid conflict with their unenlightene d neighbors, including framing garden ar eas with paths or fences, choosing species with showy flowers, and talking to neigh bors about the garden so that they know it is intentional.

The City would not make any CLIP staff available for an interview, but in an email Kevin Lessard, director of communica tions for the Office of the Mayor, wrote that “people can call the office and explain to the Vacant Lot Administrator at 215-686-4582 if they receive a violation notice or if they want to be proactive and let her know in advance.” Signage also helps to make clear that someone is tending the space.

Nonetheless, even vegetable or herb gar dens can fall victim to beautification efforts,

A tiny hops sprout emerges from a planter box.

Without the hops, the brewery can’t produce this year’s batch of Harvest from the Hood, costing it at least $25,000.

as when the Philadelphia Brewing Company found that its hop garden in Kensington had been mowed down by CLIP on September 13. The brewery uses the hops for its Harvest from the Hood beer and has been growing them at the lot next to their beer garden for at least seven years, according to co-owner Nancy Barton. She had spoken to an inspec tor from CLIP earlier in the summer after the New Kensington Community Develop ment Corporation, which owns the lot, had received a violation notice. The inspector then revisited the lot, which had a sign ex plaining the hop garden, and told Barton that the case would be closed without a violation.

“He cleared it, so we thought,” Barton says. “On Tuesday they were all chopped down.”

Without the hops, the brewery can’t produce this year’s batch of Harvest from the Hood, costing it at least $25,000.

Tyler Kruszewski, who gardens in Grays Ferry, has seen CLIP workers devastate the native plants he has tended on his property, in nearby vacant lots, and around street trees. “I’ve tried pollinator network signs … but due to vandalism in the neighborhood they con stantly get ripped down,” Kruszewski says.

He tried to enhance the curb appeal of his plantings, but that only encouraged more vandalism. “I have tried to put up little fenc es around trees, and those get kicked down

by the kids. In past years, I tried to make it look more manicured, planter boxes, and it makes it a target. I’ve found there’s less disturbance if it looks like weeds,” he says. The aesthetic also better fits his gardening philosophy. “You can garden with plants in a very controlled, manicured way, but I think nature knows best.”

Kruszewski spent three years building up the perennial plants around his house, but this summer they were mowed down by CLIP. “I knew CLIP was coming, and I heard them outside. I went and spoke to them. I asked them to please not touch these areas.” The message must not have made it to the rest of the crew. “I heard weed whacking and ran to the window … Long story short, they cut everything down to the ground.”

Kruszewski plans to continue gardening, but with seeds he has saved rather than plants he has to spend more money on. He also plans to reach out to the CLIP admin istrators to educate them about native plant gardening.

Vincenti’s run-in with CLIP had a happier ending. She reached out to the CLIP manag ers to brief them on the garden, which at the time had signs up as well as a fence (she has since moved). “I was so happy about how kind and thoughtful they were and how they didn’t give us any problems.”

OCTOBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 11

◆

Art and the Aging Mind

Nonprofit uses art to help dementia patients unlock language and emotion by constance garcia-barrio

Acertain group that visited Ursinus College’s Berman Muse um in the 2000s amazed Susan Shifrin, associate director for education at the time. During the visit, six patients living with dementia from a nearby Montgomery County care facili ty went from silence to talk to glints of joy while viewing paintings.

“I realized there was a need for programs like this, that no one else was offering these opportunities … to come together around shared experiences of the arts,” says Shifrin, 61, an art historian and the founding execu tive director of ARTZ Philadelphia, a non

profit that brightens the lives of people with dementia and their caregivers with oppor tunities to view and make art, free of charge.

Founded in 2013, ARTZ meets a pressing need.

Philadelphia has about 213,000 residents age 65 or older, according to a U.S. Census data . The National Institutes of Health (NIH) puts the prevalence of dementia among Philadelphians 65 and older at 11.9%. That number will nearly double by 2060, the Census Bureau predicts, and with it, surely, the need for dementia care.

“There are many different kinds of de mentia,” Shifrin notes, but most predom

inant is Alzheimer’s disease, named for German psychiatrist and neuropathologist Alois Alzheimer (1864-1915), who noticed changes in the brain of a woman who had died with an unusual mental illness. It ac counts for 60 to 80% of dementia, according to the American Association of Retired Per sons (AARP).

Alzheimer’s disease interferes with signals sent between the brain’s neurons, which transmit nerve impulses. It eats away at memory, language and thinking skills, explains Anjan Chatterjee, M.D., 63, professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, is the founding director of the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics, which studies how the brain responds to art. Dr. Chatterjee has expertise in the neuroscience of architecture and has an appointment in the Weitzman School of Design.

Early stage or mild dementia may in clude, among other signs, memory loss, poor judgment, repeating questions and wandering, according to the NIH. At the moderate stage, patients may show more memory loss and confusion, and difficulty in learning things, reading, writing and rec ognizing family members. Severe dementia

LINDA

ARTZ Philadelphia director Susan Shifrin shows program participant Fran A. a piece at the Woodmere Art Gallery.

12 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022

RUTH PASKELL city healing

may hamper movement, self-care and mak ing oneself understood.

ARTZ accepts participants at any stage of dementia.

“Some people join us right after their di agnosis of MCI [mild cognitive impairment] and others when they first find out about us, which may be years after the diagnosis,” Shifrin says. “Many of them stay with us through their final days.”

With the lack of near-term prospects for a cure for degenerative dementia, the focus should be on treatments to improve the quality of life for patients, says Dr. Chatter jee, whose mother had dementia. “We have no clear biologic cures for the foreseeable future. No medications can prevent symp toms or consistently improve them. How ever, making and viewing art can increase patients’ quality of life.”

The production side, or art making, “re lies on abilities that people with Alzheimer’s disease still possess, for example their vi sion or ability to move their hands,” Dr. Chatterjee says. “Also, there’s no right or wrong way to make art, and participants don’t need an intact short-term memory. They may even enter a ‘flow state’ where they become engrossed in the activity.”

Participants’ artwork may serve as a stepping-stone to continued connection.

“It can be hard to have a sustained con versation with someone living with demen tia,” says Dr. Chatterjee, “but their art not only encourages self-expression but can become a vehicle for conversation.”

ARTZ offers participants diverse media, including intensely-colored group weav ings, painted banners, paper-based collag es, tissue-paper ‘stained glass’ pieces and watercolor, according to Shifrin.

Museum visits—the art reception side— can also enlarge the lives of persons with dementia.

“In England, doctors prescribe muse um-based arts programs for people living with dementia,” Shifrin notes. ARTZ par ticipants visit the Woodmere Art Museum in Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia’s Magic Gar dens on South Street and the Fleisher Art Memorial in Bella Vista, among other sites.

“During museum visits, facilitators en courage conversations about two or three works,” says Shifrin, noting that bright colors, animal paintings and abstract works often spark conversation. “If people are struggling with words, you encourage

A piece of art created by participant Fran during the ARTZ Philadelphia “Making/ Opening Minds through Art” event.

mer ’s Association 2020 “ Race, Ethnicity, and Alz heimer ’s” factsheet. Aware of that situation, ARTZ tai lors some programs to reach those communities through neighborhood liaisons.

“I created a Facebook page called ‘Life After Dementia’ to tell peo ple, especially the Black community, about ARTZ and other resources,” says Toya Al garin, 60, the ARTZ community liaison for Northwest Philadelphia. “My mom is 92 and has dementia,” says Algarin, an ARTZ member for three years.

The programming has fostered a sense of community for her and others.

“I joined ARTZ in 2018,” says Madelyne Groves, 50, a Spanish-English bilingual ARTZ community liaison for Hunting Park. “My mom has dementia, and she doesn’t speak English. We would be isolat ed if ARTZ programs didn’t bring everyone together.”

susan shifrin, Executive Director of ARTZ Philadelphia

ARTZ took a hit due to the pandemic.

them to take their time and use gestures.”

At the same time, the executive function that edits comments seems to grow more relaxed as dementia progresses.

“People are willing to volunteer what they’re thinking, to take chances,” Shifrin says.

The choice of art discussed is often up to the guide.

“A skilled docent can make discerning choices about which pictures to present,” Dr. Chatterjee says. “They don’t all have to be pretty scenes. You probably wouldn’t choose to present a horrific one. On the other hand, if you showed the group, say, an Edward Hopper painting, the sadness in a scene could become a vehicle for them to articulate their own sadness. The art pro vides an opening, and their world becomes less constricted.”

ARTZ also addresses the needs of those caregivers through gatherings, called Cafés for Care Partners. The meetings feature ac tivities like learning Chinese brush painting with a teaching artist.

Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia disproportionately affect Blacks and Hispanics, according to the Alzhei

“We lost 50% of our fee-for-service in come,” Shifrin says, noting that individual donors, corporate sponsors and grants pro vide funding now. “However, we’ve expand ed our programs.”

ARTZ took the museum visits online, added six new monthly programs, supplied art-making kits for care facilities during lockdown and launched a concert series in Hunting Park and Northwest Philly as part of “ARTZ in the Neighborhood,” Shifrin points out.

Meanwhile, the Penn Center for Neu roaesthetics seems stuck in a funding catch-22.

“Funders want robust evidence of the value of the arts for persons living with de mentia, but you need studies to establish the efficacy of the arts,” Dr. Chatterjee explains.

“There are key questions: What kind of art is best at what stage? How do you maximize the therapeutic effect? How do you measure benefits?”

Shifrin remains optimistic as museums reopen. “I never feel more elated than I do after watching people blossom during a mu seum visit.”

◆

For more information about ARTZ, visit artzphilly org or call (610) 721-1606. For more about the Penn Center for Neuroaes thetics, visit neuroaesthetics med upenn edu

Many of them stay with us through their final days.”

OCTOBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 13 ARTZ PHILADELPHIA

Welcome to the Neighborhood

Mount Airy coffee house boasts quality, revels in community

After growing up around his un cle’s restaurant and later working as a barista, Will Maggs realized that he wanted to have his own coffee shop.

So, just a few months before the pandemic hit in 2020, Maggs realized his dream and opened Adelie Coffee House at 6610 Germantown Avenue in Mount Airy.

“I like seeing people enjoy what I’m serv ing them,” says Maggs. “People who are neighbors that have never met each other are meeting each other and forming friend ships inside of the coffee shop, which has been really great for me.”

What was so fun for Maggs about be ing a barista was the opportunity to serve people high-quality food and drinks while

also having fun and being social. When he started thinking about what to call his coffee shop, the Adélie penguin seemed the perfect namesake because they too are fun-loving and social creatures. But, as Maggs stresses, it’s the Mount Airy community that contrib

utes so much to the atmosphere of Adelie Coffee House.

“I just couldn’t be happier with the neigh borhood that I picked for the café,” Maggs says. “It’s been great.”

When asked what a visitor to Adelie can expect to find among the offerings, Maggs is not shy to say that he carries the best prod ucts he can find. Adelie offers woodfired sourdough from Germantown-based Dead King Bread, bagels delivered from Brook lyn’s Rockland Bakery every morning, and, perhaps most importantly, beans from Maiden Coffee Roasters in Asbury Park, New Jersey, for the blends Adelie serves dai ly. Co-founded by La Colombe alum Caleb Lewis, Maiden Coffee offers a flavor profile that Maggs describes as pleasing to the ev eryday person who likes a good strong cup of coffee, but also in keeping with the more modern fruity flavors that are currently in demand. For Maggs this was the perfect middle ground.

With community and quality central to the Adelie brand, a partnership with Weav ers Way to carry their coffee has been a per fect introduction to even more neighbors in the Mount Airy neighborhood and beyond.

“Weavers Way is legendary in the co-op world, so it was really exciting to be asked to work with them. It’s a nice welcome to the neighborhood.”

PHOTO

I just couldn’t be happier with the neighborhood that I picked for the café.”

— will maggs, owner of Adelie Coffee House

Adelie Coffee House owner Will Maggs at his Mount Airy café.

14 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022

COURTESY OF VICINITY ENERGY sponsored content

learning without limits

School Day and All

2121 Arch Street, Center City, Philadelphia

www.gtms.org info@gtms.org

Montessori

Founded in 2010, RAIR is an art + industry nonprofit that interrupts the waste stream in order to facilitate the production of high-quality creative content that uses waste and the waste industry as it means for artistic production. Situated within the Revolution Recovery waste recycling facility located in Philadelphia, RAIR offers artists access to over 500 tons of material per day.

TRASH

fundraiser

November 9th at Atelier FAS Gallery, 1301 N. 31st

OCTOBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 15 The Learning Never Stops FRIENDS SELECT The Only Pre-K to 12 Center City Quaker School JOIN US for an OPEN HOUSE! Sat., Oct. 8, 9:30 a.m., Grades Pre-K - 12 Tue., Nov. 8, 8:45 a.m., Grades Pre-K - 4 Fri., Nov. 11, 8:45 a.m., Grades 5 - 12 friends-select.org FRIENDS SELECT SCHOOL 17th & Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, PA 19103 IN THE CITY AND OF THE CITY Don’t throw away a perfectly good opportunity to come and get trashy withan evening of fun while supporting sustainability in the arts!

BASH RAIR’s annual

party & art auction Wednesday,

Street WWW.RAIRPHILLY.ORG

American

Society Accredited

Day Montessori Toddler, Pre-K and Kindergarten

Montessori Monday Open House Oct 17!

PUNK, LLC

The Worm’s Emporium vendor mall offers diversity and stability for makers and artists on South Street story by kait moore

Just off South Street, pink neon lights up the new sign outside Worm’s Emporium, a boutique-style vendor art mall. Inside the light, airy space, handcrafted fine art and craft pieces delicately line shelves constructed by co founder Sabrena Wishart. Vendor stalls showcase a variety of mediums includ ing ceramics, drawing, upcycled clothing, stickers and much more. Each vendor has been selected by Wishart and cofounder Rose Ghostly, life and business partners who came up with an idea for a vendor mall in 2021.

The pair met on the dating app Tinder three years ago, and they began selling their art at markets and antique malls, often traveling great distances for a day’s worth of sales. Ghostly started selling her art in high school, but after the pandemic, she found herself focusing solely on it. After setting up and breaking down at so many art markets, Wishart and Ghostly began to dream about a stable place to sell their art in Philadelphia.

Wishart, originally from Long Island, grew up near one of the biggest malls in the country. “Malls are a big part of my history and [Ghostly] and I are big fans of antique malls, so all those things came together to form Worm’s Emporium.”

Ghostly, born in Canada, has found a sense of home in Philadelphia.

“I’ve hopped around a lot in the quest for home,” Ghostly says. “Philly is definitely the place where I am like, ‘This is going to be the rest of my life now.’ The art scene here is so great. There’s so many creative people and a great queer scene.”

The stability of Worm’s Emporium is what they hope to share with other artists in the community.

“I feel like financial and business literacy is not super common in the arts scene we are a part of or the queer scene or the punk scene,” Ghostly says. Part of their business model is to share business knowledge and provide a brick-and-mortar for local art ists to sell their products without the full responsibility of their own space.

“Part of the space is just trying to demysti fy this stuff,” Wishart says. “It’s LLC punk.”

Both Wishart and Ghostly have their own stalls in the space. Wishart’s stall displays drawings and pillows, while Ghostly’s stall houses rugs, ceramics, upcycled clutch purses with hand drawings. Ghostly cen ters her art not around a medium but rather an aesthetic of “tough femme cutesy goth” that allows her to experiment with different materials.

Wishart enjoys creating with materials that are not typically used in art, such as concrete and plastic.

“I like making things that are typically cheap and overlooked and elevating them,” Wishart says. “I think that is what we are also trying to do with the store — like mar ginalized art craft, there is not inherent inferiority of these things but they have been perceived this way or have not been considered.”

Wishart and Ghostly have observed a marginalization of crafts in the art world. Mediums like tie-dye and knitting are of ten considered less worthwhile than the fine arts, Ghostly explains. The space aims to ac knowledge these forms and curate them as an art gallery would.

The space was designed and built by Wishart and Ghostly. Wishart built the shelves, walls, and banister and tiled the en tire mall. “I am really into designing space, especially commercial space because it is

for everyone.” Wishart explains that peo ple with marginalized identities are not al ways treated well in the boutique scene. “I wanted to create a space that is luxurious for people that don’t get that experience a lot of the time.”

They received an influx of applications with space capacity capped at 53 vendors.

“We choose artists we deeply believe in and want to represent,” Ghostly says. With the stability of the space, artists do not have to worry about constantly moving around to markets or pop-ups. Instead, they can focus their attention on artmaking and experi

16 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022

KAIT MOORE

— sabrena wishart, cofounder of Worm’s Emporium

menting with new forms.

Wishart says, “It’s been kind of a delicate dance of trying to figure out what goes to gether and what pieces will mesh.”

In the back part of the mall sits a room set up for future artmaking workshops and artist talks. Although vendor capacity has a limit, Wishart and Ghostly want the space to welcome the entire community.

“We don’t just want to be a retail shop. We also want to be an arts center where people can share their crafts and learn from each other,” Ghostly says. Workshops will be beginner-friendly and offer a variety of

art forms to learn.

The community focus goes beyond just art. Wishart wanted to create a space where marginalized individuals could feel safe, seen and supported.

“As queer people we haven’t necessarily fit into typical work culture or even gener al mainstream culture,” Wishart says. “It’s important to have people make you feel like you can foster parts of yourself that have been pushed aside and smothered. We know how important it is to have not only people but spaces that make you feel like you’re okay.”

I wanted to create a space that is luxurious for people that don’t get that experience a lot of the time.”

Worm’s Emporium cofounders Sabrena Wishart (left) and Rose Ghostly in their welcoming South Street store.

OCTOBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 17

◆

STREETS AL FRESCO

COVID-19 precautions inspired the “streatery,” but can these outdoor dining destinations exist in a post-pandemic world?

story by marilyn anthony

No matter if you spell it as “streat ery” or “streetery,” these impro vised outdoor dining areas began popping up around Philadelphia in 2020. At their peak, an estimated 800 restaurants in the city were operating streateries to keep their businesses open while COVID-19 health concerns restricted indoor dining.

Originally allowed as an emergency mea sure, Philly streateries face an uncertain

future. And opinions about whether they should stay or go often depend on one’s re lationship to them; as a neighbor, business owner, employee, city official, urban plan ner or customer.

COVID-19 crisis management gave rise to streateries in Philly, but their origins are rooted in prior urban planning innovation in San Francisco and Seattle. The Universi ty City District (UCD) began experimenting with “parklets” as far back as 2011.

The parklets UCD piloted differ from streateries in important ways. Parklets are designed to be 100% public space available to everyone for reading, relaxing, people watching — just about anything except so cially unacceptable behavior. Construction was minimal and temporary — a platform in the parking lane outfitted with a railing and planters, movable tables and chairs was all it took to create small pedestrian plazas. The furniture was taken in after business hours and during the winter months. Restaurants kept an eye on parklet activi ty, while UCD insured and maintained the public spaces.

As the program expanded to six parklets, UCD conducted an impact study. It found that businesses with thoughtfully placed parklets reported up to a 20% increase in revenues. Encouraged by these results, UCD asked restaurants to pay for con struction and furnishings and to continue to monitor parklet usage.

Over time the parklet program went stagnant. Then the pandemic hit. Accord ing to Nate Hommel, director of planning and design for UCD, the time seemed right to bring what they had learned about par klets to City officials and “push the City to do something and make an impact” when restaurants had to close. The immediate solution seemed to be creating a fast-track process enabling restaurants to build and operate streateries, a kind of parklet pro gram version 2.0.

Responding quickly in a crisis could risk making some missteps. Instead, Hommel finds much to praise about the City gov ernment’s measured reactions. By enacting temporary measures with simple guide lines, the City allowed restaurants to act creatively and inexpensively — carving out spaces with parking cones, folding chairs and rope to start. Over time the makeshift solutions got progressively nicer, with solid structures, heating and better seating. Hom mel cites the impressive speed with which the City inspected and approved these early streateries. “They promised that they would review structures for approval within three days, and the City really stepped up to get those approvals in.”

Fast action meant restaurants could re sume business, keep at least some staff em ployed, continue to serve as a resource for their communities, and safely activate the streets in a time of restricted social contact.

BY

University City District’s Nate Hommel in front of the Green Line Café’s streatery on Baltimore Avenue in West Philadelphia.

18 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022

PHOTOGRAPH

CHRIS BAKER EVENS

Public safety tops the concerns of deputy managing director Michael Carroll’s team in the Office of Transportation, Infrastruc ture and Sustainability (OTIS). Although he doesn’t feel the City has sufficient evidence to assess the impact of streateries and street closings on public safety, Carroll says streat eries and street closings offer “a real opportu nity to create more vitality in neighborhoods, give businesses a chance to activate streets and blocks, conduct more business and get back on their feet.” The challenge is trying to balance the needs of various stakeholders while designing a sustainable strategy.

The pilot street closure program expired in the spring of 2022, and its implications are still being evaluated. Carroll noted that while restaurants generally favored street closings, other storefront businesses thought they had diminished visibility. Neighbors felt the loss of parking spaces and experienced inconve nience accessing their properties. While traf fic calming on closed streets was net positive for pedestrian safety, residents on parallel streets raised concerns about increased traf fic on their blocks.

Streateries on open streets bring different complications. In some neighborhoods they ate up parking spaces. Noise was a concern, as were trash and overall cleanliness. Car roll looks to the City’s partners who manage the commercial corridors like UCD and the Center City District to represent the in terests of residents and businesses within their areas. Working in tandem with these groups, Carroll hopes their insights can help make street closings and streateries more permanent and mutually beneficial.

Within City Council, former at-large coun cilmember Allan Domb and current 3rd Dis

trict councilmember Jamie Gauthier have prominently taken up the fight for streateries.

Domb, in a written response, described his councilmanic contribution. “In the face of a global pandemic, we knew we needed to act — Philadelphia businesses and res idents needed support and they needed it immediately. So, we convened a working group of government, business and com munity leaders with the goal of achieving common sense, practical solutions to help businesses keep their doors open and offer a safe experience for patrons. And, together, we delivered legislation that enabled busi nesses to expand outdoor dining.”

Gauthier has cautioned City legislators to be fair-minded in establishing new reg ulations. Throughout the 3rd Councilmanic District she serves, Gauthier wants every business, regardless of whether it is located in a business or special service district, to be allowed to install a streatery once the Depart ment of Licenses and Inspections approves their application. UCD’s Hommel sums up the councilmember’s position. “Much to my delight, Jamie Gauthier says the only equita ble thing is if everyone can do this.”

OTIS and UCD both participate in fruit ful ongoing conversations with other urban groups. Carroll’s team has learned a lot from other cities about crash worthiness, fee structures, footprint and overall regu lation. And they’ve gotten insights on safe winterizing from northern U.S. and Cana dian cities.

UCD has been fostering information sharing among large and small business districts. Hommel says one key insight is that, as with parklets, the most successful streatery design is based on modularity—

being able to add and subtract “like Legos.” He also saw that the City’s approach of coming up with simple rules, being able to quickly give yes or no answers to business owners’ questions and streamlining the ap plication and approval process built trust in City government.

At the urging of UCD, the City has de layed releasing revised regulations for streateries. Hommel hopes that the new reg ulations, anticipated for release in early fall, will incorporate all that has been learned in the past two years.

Among those anxiously awaiting the City’s decision is Jezabel Careaga, owner/ operator of Jezabel’s Café, an Argentini an restaurant on S. 45th Street. Careaga jumped at the chance to create a streatery along the 54-foot frontage of her small café. “I know it makes a difference,” she says. Outdoor sales represent 15 to 20% of her business, show that she’s open, and make her block livelier and more attractive.

Still emerging from the devastating downturn brought on by the pandemic, Careaga urges the City to be more con cerned with how businesses are doing and less concerned about the street. “At least don’t make it more complicated. We know these [streateries] work, we know how to make them prettier and safer for everyone.”

OTIS’s Carroll sounds a positive note if business owners and City officials accept a healthy amount of accountability for streat eries. “My expectation is that this will start to hit a rhythm in the spring and summer of 2023, and we’ll see good quality in terms of the ones that are on the street,” Carroll says. “We’ll also [develop] the next version of a street closure program that works.” ◆

OCTOBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 19

PHOTOGRAPH BY NIC ESPOSITO

Mural Arts executive director Jane Golden stands at the “Tribute to Diego Rivera” mural at 619 N. 17th Street.

PHOTOGRAPH BY NIC ESPOSITO

Mural Arts executive director Jane Golden stands at the “Tribute to Diego Rivera” mural at 619 N. 17th Street.

20 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022

PAINT THE CITY

Mural Arts’ Jane Golden on public art, graffiti and creating art for change story by kiersten adams

Murals are so prevalent in Phil adelphia that you can almost take them for granted. Started over 35 years ago, Mural Arts Philadelo phia (previously the Mural Arts Program) is the largest public arts program in the country, with more than 2,500 mu rals completed. Jane Golden, the founding executive director, has been the one con stant as the organization has evolved.

Before Golden founded Mural Arts, she was an artist by night, an aspiring lawyer by day. As a double-major in political sci ence and fine art, Golden was on track to go to law school. “I really thought I would leave the city and go to law school. I applied to law school, got in, and then my brother, who’s a lawyer, encouraged me to go see Ed Rendell and really emphasize that I thought the city should have a community-based art program, that he should really keep the art component alive.”

Rendell heard her pitch and agreed. “So I deferred law school for two years before I decided I wouldn’t go.”

The roots of Mural Arts Philadelphia lie in the Philadelphia Anti Graffiti Network (PAGN), founded in 1984 by former may or Wilson Goode. PAGN was tasked with stopping the spread of graffiti throughout Philadelphia. Mayor Goode hired Tim Spencer as the executive director; he later hired Golden.

Golden credits the work of Spencer and the support of Goode for making PAGN so vital.

“It was grassroots in nature, but it had a decent sized budget [and] most of the money was invested in young people, so it was quite a robust jobs program. We had the support to work with community groups around the city and do artwork, and, eventually, create murals. So when I think about Mural Arts, I think we wouldn’t be here without [PAGN].”

With Golden working within the an

ti-graffiti initiative, the program became a staple in the Philadelphia community, and, by 1997, Mural Arts split from PAGN. Mural Arts was moved under the larger umbrella of the Recreation Department by then-May or Rendell. “It was really exciting because suddenly we were a pro-art program; we weren’t anti anything anymore. And we were like, ‘Okay, what’s the vision?’ The vision was: we want to make sure as many young people as possible have access to art. And we want to make sure that there are murals and public art pieces around Phil adelphia. So we were energized by this no tion that we could be a program that wasn’t punitive in any way, that was optimistic and energetic,” Golden says.

Golden has led programming that both educates and rehabilitates. For example, the Mural Arts initiative The Guild is a paid ap prenticeship that provides formerly incar cerated individuals an opportunity to devel op skills to thrive in the workforce. Workers participate in mural making, carpentry and other creative endeavors in order to recon nect to their communities.

“The Guild, for the last six months … has been transforming recreation centers in areas with the highest rate of violence. To see how young people through this program are transformed individually, and then how they take that knowledge and energy and transform the community is incredibly in spiring. Like we get to see people grow and change and evolve. And that to me is won derful,” says Golden.

While the work of Golden and her staff has largely been celebrated, a recent edito rial in The Philadelphia Inquirer by Uni versity of Pennsylvania doctoral student Razan Idris called into question the legacy of Mural Arts, citing its ties to PAGN, which criminalized graffiti artists, and flagging the hiring of international rather than local art ists as problematic.

While Golden admits she has little pa tience for tagging or graffiti artists defac ing already existing murals, she says she has long appreciated the artistry behind it.

“I have always liked graffiti art. I was quite taken by the work of our young partic ipants back in the day. When they showed me their sketchbooks I was stunned at the level of talent. I worked with Dietrich Adonis. He had been a teacher and was a terrific designer and illustrator; I was an artist and muralist. Dietrich and I built a home at [PAGN] that was welcoming in all ways, a division within a cleanup and jobs program that nurtured, developed and sup ported their talent. If you talk to anyone from back in the day at PAGN, they would tell you we were called ‘sympathizers’ be cause we saw the talent, wanted to support it and genuinely liked graffiti art. It remind ed me of abstract expressionism, and I think that is why so many of the writers loved the work of the abstract expressionists.”

Nearing the end of 2022, and another year under Mural Arts’ belt, Golden reflects on the robust programming and future of murals in Philadelphia. “I think … murals … connect us to the larger world. But I feel nervous. I feel this keen responsibility that our collection is maintained, and that the program should continue to grow and thrive,” Golden says. “We want to make sure what we’re doing always has rigor, and that we’re being responsible to the artist com munity and to the communities all over the city. So it’s a question of doing the work with great intentionality. And asking ourselves hard questions, and always being able to be reflective and course correct.” ◆

— jane golden, founding executive director of Mural Arts Philadelphia

It was really exciting because suddenly we were a pro-art program; we weren’t anti anything anymore.”

OCTOBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 21

WHOSE STREETS?

A summer Philly staple transforms through the pandemic and the city’s gun violence crisis

story by lindsay hargrave

For over 50 years, one-way streets across Philadelphia have applied to the Playstreets program, which closes streets to traffic on weekdays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. for five weeks during the summer so children can play on them. Meals and snacks are also provided through the program, which is run by Philadelphia Parks & Recreation.

While each street must have a supervi sor, many of them are also supported by a Play Captain — or several. The Play Cap tains program, a partnership effort by Fab Youth Philly, consists of teenagers engaging with the kids, bringing toys and games, and acting as positive adolescent role models.

While in previous years the number of closed-off Playstreets in the city had reached the mid-300s, in 2022 there were only 230. The residents of some of these streets reported to Grid that they felt it was no longer safe due to the past few years’ es calating gun violence crisis, and this led to them not applying this summer. Playstreets is a voluntary, application-based process, so the numbers dwindled.

“I’ve got a little bit more kids lately be cause they tell me the streets are shut down where they live because of the violence and stuff,” said four-year Playstreet supervisor and Kensington resident Debra Williams, who has lived on a Playstreet block for over 30 years.

Recent transformations

Though the numbers have been reduced, Playstreets is offering more to the partici pating streets.

Cooling kits containing personalized misting fans, super soakers, tents, patio um brellas and neck cooling rags were sent to 100 Playstreets in the most heat-vulnerable

areas, particularly in low-income commu nities. With these neighborhoods generally having fewer trees and therefore less shade, these kits are serving a critical need.

“The pandemic offered Philadelphia Parks & Recreation [a chance] to innovate its Playstreets program. In 2020 and 2021 Philadelphia Parks & Recreation expanded its Playstreets program in partnership with the YMCA of Greater Philadelphia, raising over $600,000 to bring enhanced recre

side. We could not be inside the summer of 2020,” noted Kensington resident and exec utive director of Fab Youth Philly Rebecca Fabiano, which facilitates the Play Captains.

Twelve locations were added to the William Penn Foundation-funded literacy enhanced Playstreets, which focuses on playful learning and literacy, and 50 “Su per Streets” received daily programming including arts and sports demonstrations; pop-up dance parties; visits from Mural Arts Philadelphia’s Mural on the Move Program; and portable play landscapes like water misters, seesaws and modular play islands. The City promised that every Playstreet would receive something from the new expansions.

While these additional services were wel come, many people involved said they had concerns about safety. Sakura Regusturs, 17, was a first-time Play Captain this past summer. She says she would return to the program next summer, but she has some reservations. “There was a lot of uncomfort able situations, and luckily our group lead ers were around with us making sure that we were safe.” Still, she said the thought of walking around those areas alone worried her. “It was complicated, to be honest.”

Williams confirmed. “Even [the Play Cap tains have] expressed [concern about] ... the violence on the streets. Because there were a couple times where they came here and they’re like, ‘Ah, well, we were at the other block and we had to leave because they were shooting or arguing or whatever,’ and I’m like, ‘Wow.’ It’s bad everywhere you go.”

Alternatives to the program

For children who are not a part of Play streets, Soukup points to other options available through out the city, including Parks & Recreation’s 130+ summer camps, the Out of School Time summer programs offered by City’s Office of Children and Families, and the network of summer feed ing options

ational opportunities to children on their block,” wrote Maita Soukup, communica tions director for Parks & Recreation. She added that they did this in partnership with recreation staff and seasonal employees at a time when there was limited opportunity for children to leave their homes due to the pandemic.

“There was a greater investment [in Play streets] in 2020 because we could be out

Still, not closing certain streets in violent parts of Kensington strands some of the most vulnerable children and families, as many are too afraid to leave their homes. By not shutting those streets down specifically for safe play in the summer, children may not be able to access many of the other pro grams and parks available to them.

“It’s just a shame that our kids don’t have nowhere to go no more. They can’t even be

Even though it’s a bad environment, you still wanna give them that hope.”

sakura regusturs, play captain

22 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022

outside on their own block,” Williams said.

Fabiano echoed this concern. “When we choose not to go on a street, it breaks my heart because there are other children on that block who would really benefit from seeing teens like themselves as role mod els, teens from their own neighborhoods, in leadership roles, playing games, having water balloon fights.”

Physical conditions

According to Parks & Recreation, side

ILLUSTRATION BY MALACHY EGAN

walk conditions are not one of the factors assessed when processing Playstreet ap plications.

Playstreets only serves small, one-way streets for the safety of the children. Howev er, these less-traveled streets tend to fall the furthest down on the City’s list for repairs, and the condition of those streets and side walks affects how children can use them.

This is compounded by the fact that, in Philadelphia, even though the City is supposed to cover 70% of sidewalk main

tenance, there is no City funding for this ex penditure and thus sidewalk maintenance defaults to the responsibility of the home owner. So if the City is not maintaining or assessing the sidewalks on Playstreets, it essentially becomes the discretion of the individual who lives there. And with each home’s sidewalk being maintained by a different person, it can be difficult to find consistency — or safety.

Regusturs noted that this only made her job as a Play Captain more difficult. “Includ

OCTOBER 2022 GRIDPHILLY.COM 23

ing the needles on the ground and all the dirt and everything like that, the sidewalks are extremely jacked up, and we happen to be having to push a cart full of toys and things to play with kids, activities, so us pushing the cart made it hard for us to walk on the sidewalk,” she said.

Helping young people

One of the major benefits of integrated com munity programs like Playstreets and Play Captains is the opportunity they provide for young people like Regusturs.

“Although there are some terrible sides of working in Kensington, I do recommend that other teens my age go and work with these kids, because even though it’s a bad environment, you still wanna give them that hope,” she said. “I feel like they need someone to give them the correct influence.”

Soukup noted that Playstreets are “an opportunity for the City to support com munities and the volunteers who look over their block and care for its young people.”

Williams raves about the volunteers who worked on her block.

debra williams, Playstreet supervisor in Kensington

“The teenagers who come out, especially the groups that I had here … they’re really good kids. Whoever hand-picked them kids this year did a good job, because those kids were wonderful, and they were wonderful with the kids,” she said, adding that nor mally it can be difficult to get the kids on her block to even come outside.

Community concerns

“In 2017, 2018, even 2019, we could still walk down Kensington Avenue with our shop ping cart full of supplies and toys and ma terials and get to just about any street we wanted to be on,” said Fabiano. But starting in 2020, she said, she would have to begin

being more selective about which streets she would bring her captains to and eliminate more and more of them. “The walkability was not there,” she said, as a direct result of the opioid epidemic’s recent explosion into neighboring areas.

Williams said she would like to see the program expanded and more people in volved, as well as the positive attributes of her community highlighted. “The news, the TV, everything you see is all the bad stuff,” she said. “They don’t highlight anything that’s good in the area. Maybe if you high lighted more good stuff in the area, it would make more people want to do it because they would want that for their area.”

PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

I’ve got a little bit more kids lately because they tell me the streets are shut down where they live because of the violence.”

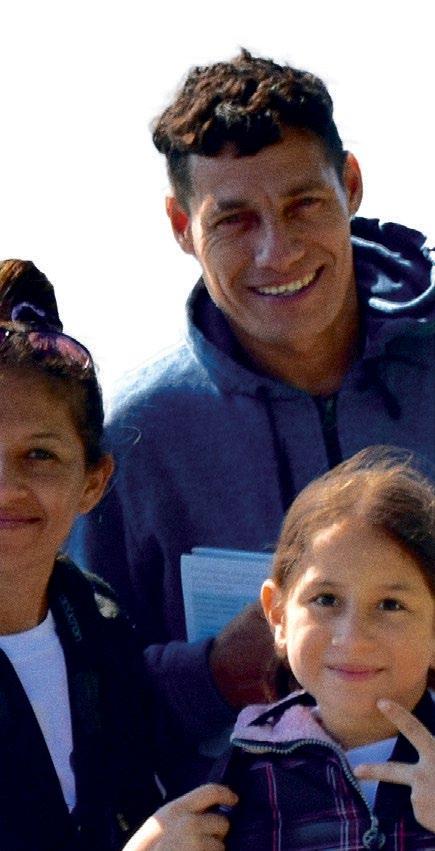

Playstreets supervisor Debra Williams stands on a Kensington street closed to traffic for children to play.

24 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022

◆

WE CONNECT PEOPLE TO THEIR CREEKS

We are TTF Watershed

Our mission is to improve the health and vitality of our watershed by collaborating with our municipalities and leading our communities in education, stewardship, restoration, and advocacy.

Hey, businesses!

Make a difference by joining our Partner Alliance. Enjoy year-round marketing & networking benefits.

“ Rodriguez Consulting is proud to be a Partner Alliance member because we understand that clean waterways and access to healthy green spaces are essential for improving the physical, mental, and social health of our communities. We are honored to be part of a network that demonstrates our dedication to sustainability by supporting the critical work of the Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed Partnership.

OCTOBER 2022 EDUCATION | STEWARDSHIP | RESTORATION ADVOCACY|

Stay In Touch! ttfwatershed.org @ttfwatershed

story by bernard borown

photography by chris baker evens

ACCESS FOR ALL

A class action lawsuit seeks to ensure that people with disabilities can fairly use sidewalks

Domonique howell doesn’t like to roll through the street in her wheelchair, but sometimes it’s better than the sidewalk, like when a tree heaves up the concrete so much that her wheelchair could tip over. “I try not to because I’m with my daughter, who is eight, and it’s a dangerous thing to teach her, but there are times you have to,” Howell says. The two split up, so that her daughter walks on the sidewalk and then waits for Howell at the corner.

Even where the City has installed acces sible ramps, getting around by wheelchair “sucks,” Howell says. Howell, who is active in the advocacy groups Disabled in Action of Pennsylvania and Philadelphia ADAPT, lives in West Philadelphia’s Wynnefield neighborhood, but her work as an indepen dent living specialist with Liberty Resourc

es takes her all over. “A lot of the sidewalks are broken up and/or disturbed by trees up under them, so they’re not flat, and for wheelchair users that kind of introduces a hard way to navigate throughout the city.”

ADAPT advocate and wheelchair user Domonique Howell tries to navigate an uneven and broken sidewalk at the corner of Belmont and Conshohocken avenues in Wynnefield Heights.

Mary Salisbury, who lives in the Callow hill neighborhood, agrees. “It can be chal lenging and tiring, honestly,” she says. “I love Philadelphia. There’s so much to offer, but there definitely need to be improve ments in sidewalks and roads…. There are a lot of cracks in the sidewalk that wheels get stuck in. Curb cutouts [ramps] can be steep or nonexistent.”

The design of those curb cutouts matters a lot, Salisbury says. If there is a lip between the ramp and the road surface, her wheels can get stuck at the bottom. An overly steep

ramp is a hazard as well. People who use a wheelchair due to paralysis might not have the core strength needed to hold their torso upright as their chair leans forward on the way down a ramp, Salisbury says. “With some curb cutouts that are extremely steep, I turn around and go backwards.”

Poorly-built ramps can also be disgust ing, with puddles forming at the bottom.

“Some have a bigger dip and always have a puddle in the middle,” says Samantha Twining, a registered advocate with the United Spinal Association. “Any time it rains it stays there for a while.”

26 GRIDPHILLY.COM OCTOBER 2022

The City has been replacing older ramps with newer ones that comply with the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), but at a rate, advocates say, that is far too slow. A 1993 court decision found that the City was out of compliance with the ADA and man dated that it replace ramps on any sections of street being resurfaced.