Saving

publisher Alex Mulcahy

director of operations Nic Esposito associate editor & distribution Timothy Mulcahy tim@gridphilly.com

copy editor Sophia D. Merow art director Michael Wohlberg writers Kiersten Adams Marilyn Anthony Bernard Brown Constance Garcia-Barrio Lindsay Hargrave Dawn Kane Sophia D. Merow Bryan Satalino Hannah Smith-Brubaker photographers Drew Dennis Chris Baker Evens Troy Bynum Rachael Warriner

illustrators Bryan Satalino published by Red Flag Media 1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107 215.625.9850

Yes, this is our food and farming issue, but it’s so much more. When we launched the 2030 Series in April, our goal was to focus each month on a single top ic through the lens of sustainability. The themed issue is a tried and true convention for editorial, but when it comes to sustain ability, the divisions between topics quick ly blur. Nowhere is that more evident than when we talk about food.

The intersections of food and waste are front and center in our cover story about Sharing Excess. Evan Ehlers and his or ganization scored a major public relations coup when they handed out millions of pounds of free avocados, but the real story is the infrastructure that Sharing Excess has built in just a few years. Every week, they are saving 100,000 pounds of food from going to the landfill.

The story has a climate change angle. Food that goes to the landfill decomposes anaerobically, which releases methane, which has more than 80 times the warm ing power of carbon dioxide over the first 20 years after it reaches the atmosphere.

It has a social equity dimension because Sharing Excess delivers food to organi zations that serve people who have been marginalized by our economy. It begs the question: Why are there so many people who cannot afford to buy food?

If we work backward a little further, this “food story” has an energy component (and climate change again!) due to the fact that the majority of our food is manufactured using fossil fuel-intensive pesticides and fertilizer.

This in turn becomes a water issue when excess fertilizer makes its way into streams, rivers and lakes causing toxic algal blooms that are harmful to aquatic life.

Because farming requires physically challenging work but the jobs are seasonal and don’t pay well, there’s a labor compo nent. (You can also file this under health care, as farm workers typically cannot af ford health insurance.)

Of course there is also an intersection with transportation , as those distributed avocados were grown thousands of miles away. Since transportation requires energy from fossil fuels, once again you are talking about climate change.

Finally, there is land use, because forests are often cleared for agriculture, which re sults in biodiversity loss. (Not to mention the land necessary for our extensive highway system.)

Agricultural businesses routinely choose what is most cost-efficient, and that results in waste, pollution and the pillaging of the natural world. Profits are prioritized over the health of our ecosystems, the dignity of our workers, and the livability of our planet — for humans and all other creatures.

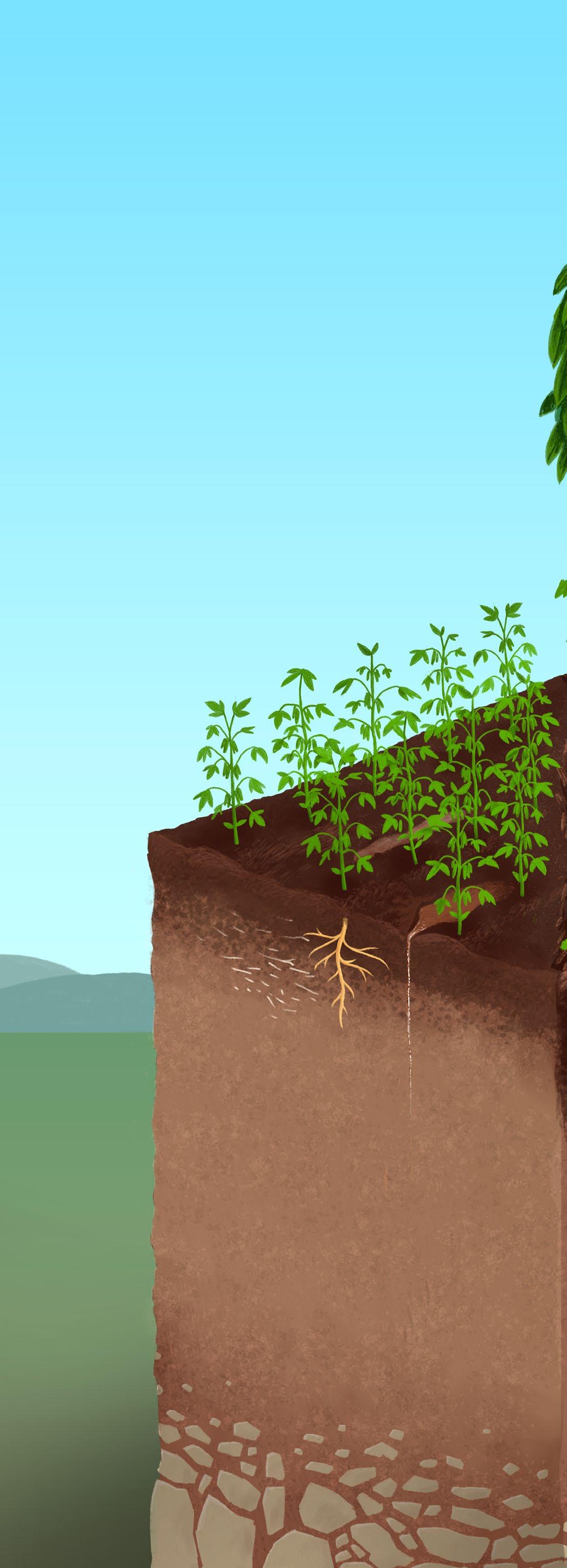

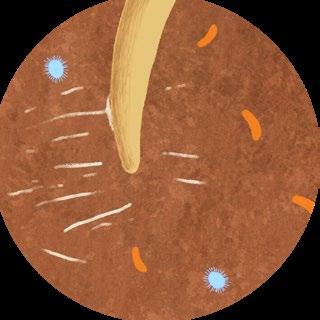

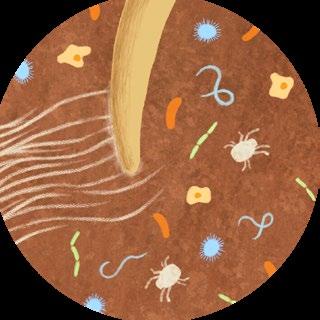

That’s why I find myself lingering over the illustration on page 58 about perma culture versus conventional farming. This is where it all begins: the health of our soil and the farm labor it requires. When we pri oritize our soil, it will immediately and pos itively affect our food and, in turn, prioritize the people doing the farming over the prof its that are produced. The negatives of our food system could be turned around and become forces for good. When we change our food system, we change the world.

BY JAMES BOYLE

When kiera thompson lost her job at a consignment store at the onset of the pandemic, she looked for something to occupy her time. She decided to invest in a candle making kit and try it out as a possible hobby.

“This was literally just a little tiny kit, and I just found it really fun,” Thompson explains. “But from there I started ordering more candle products, and then it became more than a hobby.”

As a longtime baker, Thompson also found commonalities between the art and science of making candles and the measure ments and precision it takes to make a great loaf of bread or a tasty treat.

Thompson is very intentional about the essential oils she uses to make scents for the right mood. Currently, her favorite blend is “vanilla rose,” which comes with herbs and flowers decorating the top of the wax. Thompson also incorporates jasmine, bergamot, pineapple, sandalwood, laven der and chamomile, which she says is a customer favorite.

“I feel like candles bring a little luxury to wherever you put them, whether that’s in your living room or your kitchen,” Thomp son explains. “It’s like a mood setter.”

Although Thompson was able to land a job as the economy opened back up, she still found time to make enough candles to stock an Etsy.com store. After creating a solid fol lowing, Thompson caught the attention of Weavers Way Co-op’s vendor diversity co ordinator Candy Bermea-Hasan.

As Thompson recounts, she didn’t know what was going to happen beyond the first order. So she was pleasantly surprised when Weavers Way placed a second order and then a third. In addition to the benefit of steady sales and exposure from having her product in a physical store with a large

clientele that is committed to buying local, Thompson explains that another perk of working with Weavers Way is how much she’s learning about the process of fulfilling orders, ensuring quality and expanding her marketing.

Thompson welcomes the constructive feedback Bermea-Hasan and the Weavers Way team have provided for her on new things she can try to grow her business or tips on what to avoid as a newbie. One example Thompson mentions is when she wanted to use gold tins for her can dles. Weavers Way knew from experience that their clientele preferred black tins, so

Thompson made the adjustment. “That’s just something I would have never known,” she admits. “So I’m learning a lot.”

Thompson is still looking to improve her presence on Etsy and Instagram. She’s look ing to get into more stores now and would one day like to be in larger chains like Tar get. But for now, what keeps Thompson going is the therapeutic nature of candle making, which was one of the major things that drew her in during the pandemic. For Thompson, it allows her to exercise her creative side, and it makes money. “If that wasn’t an aspect, I don’t know if I would still be doing this.”

I feel like candles bring a little luxury to wherever you put them.”

kiera thompson, owner of Luminous IntentionsLuminous Intentions owner Kiera Thompson credits Weavers Way Co-op with the opportunity to grow her candle business.

On a rainy day in early October, clear water flows from the down spout draining the roof of Peter Zettlemoyer’s livestock corral, bound for Manor Creek just down the hill. Two black and white Holstein heif ers that Zettlemoyer is raising for a nearby dairy farmer, amble over to the railing that pens them in to check out the visitors shar ing the shelter of the metal roof.

That roof, built with funding from Berks Nature and the USDA’s National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) in northern Berks County, now keeps the rainwater from falling onto the bedding and manure beneath. “What used to happen was when it would get heavy rain, the corral would fill up with water, and a little pipe that used to

come out right around this area,” Zettle moyer gestured at the base of a low concrete block rim. “I’ll be honest with you. All the manure would ooze out … And of course that all runs down to the creek there. That has all improved, obviously.”

Farming is a low-margin business, and farmers often don’t have money to spare to make improvements that will protect wa ter quality. “The nice thing about NRCS and Berks Nature, I wouldn’t have been able to afford this without them.”

Zettlemoyer rattled off a list of measures that now protect waterways from his farming activities, including better timing for spread ing manure on fields, planting cover crops, and putting up fences to keep cattle away from the water. “Years ago the cattle were all

in the creek, and the streambanks were all beat up. We got the cattle out of the creeks.”

A multi-faceted defense of the watershed About a quarter of the Schuylkill River basin is farmland, though that might be hard to believe from the vantage of urban Philadelphia, where two-thirds of the city drinks its water. The rain running off the roof of Zettlemoyer’s corral will end its journey flowing under the Girard Point Bridge, where the Schuylkill flows into the Delaware.

Zettlemoyer farms about 650 acres for a mix of crops including hay, rye, wheat, soy beans and corn. He owns 100 acres, and the rest he leases from other nearby landowners. A verdant mix of rye grass, sunflowers and

radishes greets the rain from a field Zettle moyer leases from Chris Schucker’s family, just uphill from a small unnamed stream, it self a tributary of Manor Creek, which runs along the road. The forested Blue Mountain ridge rises into the clouds behind the field. The deep green plants form a “cover crop,” sowed to buffer the soil of a harvested field from rain and snow until something else can be planted in the spring.

Along with agricultural practices such as sowing cover crops, the Schuckers have tak en other steps to protect their land and the water flowing from it. Their land backs up to Pennsylvania State Game Land 106 on the mountain. There they are working with the NRCS and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources to restore forest impacted by invasive plants like Japanese stiltgrass, which blankets the understory, and tree pests such as the emerald ash borer and the hemlock woolly adelgid, which infest and kill the trees they are named for. Working with the Stroud Water Research Center, Schucker has plant ed trees along the stream, hoping to fill in a section of forest along the waterway.

Planting trees might seem pretty straightforward, but, as Lamonte Garber, watershed restoration coordinator for Stroud, explains, Stroud and its partners have learned that planting trees isn’t as easy as it looks. “We killed a lot of trees 20 years ago. I say ‘killed’ because we planted them in ways that almost ensured they were go ing to get killed or outcompeted. Since then we’ve totally overhauled how we do these

tree plantings, with maintenance being so much more important,” Garber says.

Schucker has been tending his family’s new trees, but Stroud arranges tree main tenance for farmers who do not have the bandwidth to take on the extra task.

Deer are a constant threat to young trees. “Deer suck,” Schucker says. They browse any twigs and leaves within reach, and bucks will strip the bark off a tree and rip off protective cages as they rub the velvet off their antlers in the fall. Smaller mammals such as mice and voles kill young trees in less dramatic ways. They build their nests in the protective wire cages and plastic sleeves (called “tree shelters”) that protect saplings. As other food dies back, they dine on the bark around the base of the sapling, girdling the young trees. “We’re experi menting with gravel now, a small pile of gravel around the shelter to be a barrier so voles can’t get in there,” Garber says.

Down the road, and downstream from the Schuckers’ property, cattle graze in a field along Manor Creek. Although the meadow has a muddy patch around a hay bale feeder, a fence keeps the cattle from hanging out and dropping their manure right in the water. The fence also protects a strip of trees and other vegetation along the creek. “The animals are still there, but now they’re backed up away from the creek, and that muddy heavy animal concentration area is further away from the creek,” Garber says.

At another farm along the creek, a solar powered water sensor station installed by the Berks County Conservation District keeps track of water quality in Manor Creek. It spits out a constant stream of read ings for metrics including water tempera ture, turbidity (how cloudy the water is) and electrical conductivity, which indicates the amount of dissolved nutrients in the water.

The improvements upstream all should im prove water quality, but it is critical to know whether they are actually doing the job.

This question of what works best — and how to improve it — is a reason the Dela ware River Watershed Initiative, which includes Stroud, Berks Nature and other partners and is largely funded by the Wil liam Penn Foundation, has concentrated its efforts along specific subwatersheds such as Manor Creek.

“What we’re doing here is identifying small watersheds where we can concentrate a lot of implementation work,” Garber says, “enough so we’re hoping it will then show up in terms of change for the better in the water and the habitats along the water that we can monitor.”

Garber says Stroud Center entomologists also catch invertebrates that live in the wa ter. Different species can tolerate different levels of water pollution, so finding pollu tion-intolerant species can demonstrate improving water quality. “That combina tion of the science and the implementation. Manor Creek and some of these other focus watersheds are like laboratories where the farmers, the conservationists, the scien tists are working together not only to build good stuff to make the water cleaner and the streams healthier but also to evaluate what’s working and what isn’t,” he says.

A wood turtle crosses the farm’s driveway in the rain, pausing before sliding its way down to Manor Creek. It likely prowled the creek and its floodplain well before any trees were planted or any buffer fences went up, and it could continue to do so for decades to come. “These streams reflect change along a 400-year period,” Garber says. “We are not going to turn this stream around in a decade, but these aggregated projects stacked up … all the way up to the mountain, that’s a really im portant part of the change we’ve got to make on the land.” ◆

Years ago the cattle were all in the creek, and the streambanks were all beat up. We got the cattle out of the creeks.”

peter zettlemoyer, Pennsylvania farmer

As don shump, the owner of the Philadelphia Bee Company, pre pares to move a bald-faced hornet nest from the side of a large grave marker at Fernwood Cemetery in Lansdowne, he offers some advice. “These girls tend to run and gun. So when they’re mad, they tend to hit you and spin back off for another pass,” he says. “So if one gets on you and if you can crush it, that’s the way to deal with it: crush and chuck.”

I don’t entirely trust my crushing and chucking skills, so, along with Grid pho tographer Troy Bynum, I back up to about 25 yards from the nest. “Bees and wasps punish bravado and stupidity with equal fervor, so it’s best not to be brave and stu pid,” Shump says. Troy and I are content to be cowardly and smart.

Bald-faced hornets are black wasps with white on the end of their abdomens and —no surprise — their heads. More close ly related to yellowjackets than to the true hornets of Europe and Asia, they build in verted-tear-shaped nests out of wood that they chew up and then spit back out as pulp,

laying down rows of curves that, thanks to the variety of woods used as material, end up as varied stripes that camouflage the nest. They often build these nests high up in trees or stuck to the sides of buildings. The workers spend their days hunting insect prey that they then feed to the larvae growing in the cells of the nest. Bald-faced hornets are pretty mellow as far as wasps go, assuming you don’t get too close to the nest.

Left to right: Hornet nests can easily blend into the surrounding environment and startle people paying their respects at the Fernwood Cemetery in Lansdowne. Philadelphia Bee Company owner Don Shump carefully removes a hornet nest from a large grave marker. Shump has to use a range of tools, from vacuums to bee suits to smokers, to safely remove beehives and hornet nests.

Shump stands right next to the basket ball-sized nest and knocks on it with one gloved hand to get the workers excited. He is shielded by a padded beekeeper jacket with a hood and netting over his face and armed with a vacuum cleaner. Shump then sucks the wasps up with the vacuum’s wand at tachment as they emerge to do battle. A few workers zip past our heads, but Troy and I manage to avoid any stings.

Shump got into the wasp removal busi ness (he removes “anything that flies and stings”) as an addition to the Philadelphia Bee Company’s honeybee hive removal ser vice. “Originally I had started off doing the honeybee side, and we didn’t do the wasps,” Shump says. Property owners who called the company for help couldn’t always tell the difference between honeybees and oth er flying, stinging wasps. “I felt bad telling people, ‘Those are wasps — I can’t do any thing.’ So we started doing wasp removals.”

Shump’s passion for honeybees soon grew to encompass their relatives. In Philadelphia there are at least 150 species of wild bees, along with many times more species of other wasps (technically speaking, bees are wasps).

Shump’s face lights up as he talks about a

rare species of cuckoo bee, Nomada sphaero gaster (lots of insects don’t have common names and are known by their scientific names) reported in Riverton, New Jersey. While most bee species visit flowers to col lect pollen and nectar to feed their larvae, cuckoo bees instead lay eggs in other bees’ nests. Their offspring steal the other bees’ provisions. This means you can’t find them by sitting and watching flowers. “I’ve been looking for that one for seven years now,” Shump says.

Only honey-bees produce honey, though, and the Philadelphia Bee Company keeps more than 100 hives around the city. Shump originally got into beekeeping as a break from working as a web designer. The hob by grew into a profession, leading him to incorporate the Philadelphia Bee Company in 2012.

The company sells seasonal and varietal honeys through its website and at popup events like the Christmas Village near City Hall. Shump talks about honey like a som melier talks about wine, combining descrip tions of the honey batches with accounts of the plants and weather that yield their characteristics. “Fairmount Park spring

this year was almost certainly black locust: water-white, gorgeous!” Shump says. “You only get that every two years or so because the blooms are so sensitive.”

“Our Old City fall from 2016 was black as pitch. We got 12 pounds of the really dark stuff. I didn’t sell any of it,” Shump says. “I gave a few jars to the building owners [of the properties at which the hives were placed] and I took it to honey tastings. Peo ple said, ‘Where can we buy it?’ and I said, ‘You can’t! It’s all mine!’”

Not all honey comes from flowers. Insects that suck up plant sap need to vent sug ary liquid, called honeydew, as they feed. Bees sometimes gather the honeydew and make honey out of it. The company’s sum mer Doom Bloom varietal is produced by bees from spotted lanternfly honeydew. “I

walked into my honey house five years ago and I asked the guys, ‘Who’s eating maple bacon?’ because that’s what it smelled like,” Shump says.

With most of the workers inside the vacu um, Shump cuts the bald-faced hornet nest apart and puts the core of it, its cells packed with larvae, into a large Ziploc bag for dispos al. While feral bee hives that Shump removes can be converted to honey production, wasps can’t be relocated. Shump has mixed feelings about killing the creatures he loves, but he understands that most people, including cemetery managers concerned for the safety of visitors, might not want them around. “I recognize my feelings on stinging insects are not what one would consider normal,” he says. “There is nothing wrong with having a healthy respect for stinging insects.” ◆

Bees and wasps punish bravado and stupidity with equal fervor, so it’s best not to be brave and stupid.”

— don shump, owner of the Philadelphia Bee Company

Convicted of attempted murder at age 17, Philly performing artist and musician Andre Simms, or DayOneNotDayTwo, his stage name, spent eight years in an adult prison. Released in 2021, he’s now the lead youth organizer with the Youth Art & SelfEmpowerment Project (YASP), 924 Cherry Street, a group of young people working to reform the juvenile legal system in Penn sylvania.

“During the first four years, I spent half the time in solitary confinement,” DayOne, now 26, says. Post-traumatic stress still breaks through his life at times. “The other night, my partner dropped something on the floor, and I jumped up, ready to fight.”

DayOne’s case isn’t unique. As of Octo ber 2020, Pennsylvania youth prisons held 1,098 youths, according to No Kids In Pris on, a national campaign to end youth incar ceration and invest in community-based supports for young people. State Senator Anthony Williams, 65, co-sponsor with Camera Bartolotta, 58, of bills that revamp Pennsylvania’s juvenile legal system, cites a higher number.

“Some 3,612 young people under the age of 18 are in secure detention [including pris ons and jails] in Pennsylvania [as of August 2022],” says Williams, who represents parts of Philadelphia and Delaware Counties.

While YASP, founded in 2005, works in Philly’s prisons, courts and neighborhoods towards effective youth justice, Sen. Barto lotta, Sen. Williams, State Rep. Chris Rabb and other legislators hammer out bills in Harrisburg to change the current failed racist juvenile legal system.

Problems take root years before young people enter the system, DayOne stresses.

“At school, children often sit in over crowded classes,” he says. “They have lim ited arts programs, and often, no library. At home, children may face poverty and hunger. I was directly impacted by poverty

growing up as were the majority of young people we work with at YASP.”

Other pressures may come into play.

“Seventy percent of youth in the juvenile justice system have a diagnosable mental health condition,” writes Daniel H. Gillison Jr., CEO of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), headquartered in Washing ton, D.C., in the spring 2022 issue of “Voice,” NAMI’s newsletter. In many cases, young defendants have experienced abuse, accord ing to The Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy center based in D.C. that seeks to reduce incarceration in the United States and address racial disparities in the crimi nal legal system.

“You’re punishing youth for being trau matized,” DayOne says.

Race often dictates who goes to prison in Pennsylvania. Black youth in this state are “5.7 times more likely than white youth to be incarcerated,” No Kids In Prison says.

Money, or the lack of it, also helps to decide who lands behind bars. “Over whelmingly, youth of color who don’t have adequate defense end up incarcerated,” says Sen. Bartolotta, who represents Bea ver, Washington and Greene Counties in Western Pennsylvania. She co-founded the Pennsylvania Legislative Criminal Justice Reform Caucus, a bipartisan coalition, with Philly’s Senator Art Haywood. “[Youth of color] make up two-thirds of young people held in pretrial detention.”

YASP and legislators have targeted prob lematic practices in the state’s juvenile le gal system, including charging children as adults, incarcerating children with adults, removing children from their homes for low-level offenses and offering few alter natives to detention.

Reform bills SB1240 and SB1241, de

YASP organizer Andre “DayOne” Simms organizes on the local and state level to make sure legislators understand the many traumas that lead to youth crime.

veloped by Sen. Bartolotta, their primary sponsor, build on recommendations in the June 2021 report of the Pennsylvania Juve nile Justice Task Force.

“Task force findings show that most youths are not headed toward adult crime,” Sen. Bartolotta says. “The research shows that juvenile justice should focus on reha bilitation, not punishment.”

Charging children as adults is an area of concern for good reason, says the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychia try (AACAP) in Washington, D.C. Children and adults are different, AACAP stresses.

Youth tend to make less judicious splitsecond decisions and to have less impulse control than adults, according to AACAP. Pleasure-seeking and peer pressure also sway young people more, the organization says.

In the past, charging children as adults appealed to some authorities because it al lowed longer prison sentences. But more prison time doesn’t necessarily mean a safer citizenry, AACAP says. It hangs a millstone around the young person’s neck.

Youth tried as adults “are no longer eligi ble for federal or state loans for education or housing, … increasing the chance that they will remain involved in the criminal system,” says AACAP’s position statement, “Adjudi cation of Youth as Adults.” “Also, convict ed youth cannot vote in most jurisdictions which only serves to further marginalize these young people,” the statement adds.

One of Sen. Bartolotta’s bills raises the age for trying children as adults from 14 to 16.

“The bill also requires prosecutors to

show a need for treating young people as adults,” she says. “Prosecutors could no longer send the case to adult court directly.”

Treating young offenders as adults may backfire in another way.

“Research shows that adult prosecution can make kids more likely to continue com mitting crimes, which makes the whole com munity less safe,” says Sen. Bartolotta.

Incarcerating children with adults has also come under YASP’s and Sen. Barto lotta’s scrutiny.

“[Adult prisons] are dangerous for youth physically and emotionally,” DayOne says. “I had to fight all the time. And it’s un healthy for young people to be locked in a cell 23 hours a day.”

The Equal Justice Initiative of Montgom ery, Alabama, pulls no punches on this top ic. “Children under 18 held in adult jails and prisons are at great risk of sexual and physi cal violence,” the group says, noting that the majority of states still allow children to be confined with adults.

“Sometimes, kids as young as 13 are in jail with adults while waiting for trial,” Sen. Bartolotta says. “They haven’t been found guilty of anything. They’re missing school, [social] services and family while they wait for a court date. The situation increases the likelihood of recidivism. In other words, communities end up less safe.”

In addition, children in adult prisons may forego rehabilitative programs, such as vo cational training, often available in youth detention centers, The Sentencing Project says. Such opportunities can help young people find employment and succeed after leaving prison.

Young people in adult facilities may lack access to arts programs that can encourage rehabilitation through introspection.

“I developed and facilitate Ascensions, a series of creative writing, music and poetry classes for youth,” DayOne says, speaking of workshops he gives at the Riverside Cor rectional Facility [on State Road in Northeast Philadelphia] on Saturdays and on week days in the wider community. “It’s a chance for young people to express themselves. We compose socially responsible hip-hop to com bat the culture of violence. I found journaling and writing cathartic when I was incarcer ated. I wrote my debut album when I was in prison,” he says, adding that adult prisons may also lack the mentoring accessible at

some youth detention centers.

Separate detention facilities for young people can become a matter of life and death. Youth in adult prisons are nine times more likely to commit suicide than those in juvenile facilities, the Equal Justice Initia tive says.

YASP and Sen. Bartolotta also seek fewer placements in detention centers for misde meanors. The juvenile legal system slams young people of color in that respect too, The Sentencing Project points out.

“Some of the largest racial disparities ex ist for Black … youth, especially boys,” The Sentencing Project says. “[They get] the most punitive system response, including removal from the home and prosecution as adults.”

Sen. Bartolotta questions pulling young people away from their families and potential community support for low-level offenses.

“In 2018, two-thirds of children in youth facilities were there due to a first, nonvio lent offense,” she says. “It’s inefficient. It costs $211,000 per child per year. On the oth er hand, family therapy costs about $3,700 per year, and you have the possibility of strengthening the emotional health of the entire household.”

In addition, placement outside the home may not provide safety or rehabilitation. In the spring of 2019, the Pennsylvania De partment of Human Services revoked the license of Delaware County’s Glen Mills School, the nation’s oldest reform school, due to allegations of staff abuse of young residents. In 2017, The Philadelphia Inquir er reported “death, rapes and broken bones” at the Wordsworth Academy, which billed itself as a treatment center for troubled youth, on Ford Road in Wynnefield Heights. It was closed after the asphyxiation death of Black teen resident David Hess during a struggle with staff.

YASP and Sen. Bartolotta also zero in on offering alternatives, or diversion, from the court route that leaves youths with a crim inal record.

“Data show that diversion is a successful alternative, but most kids aren’t given the opportunity, even for a first offense,” says Sen. Bartolotta. SB1241 supports diversion from the court system.

Likewise, YASP has pioneered the Heal ing Futures Restorative Justice Diversion Program as a more reparative approach. Kempis “Ghani” Songster, 50, who entered

Juvenile Justice Center of Philadelphia (JJC) “helps prevent young people from entering the child welfare and juvenile justice systems through supportive services,” says Jeanine Glasgow, 53, executive director of the nonprofit founded in 1976.

Programs at JJC, with offices in Southwest Philly and Germantown, include intensive therapy, mentoring, in-home detention with support, truancy prevention and intervention, among other services.

To step up prevention, JJC recently launched a Community

prison at age 15 and served 30 years, heads the program. Begun in 2021, Healing Fu tures receives pre-charge cases from the district attorney’s office.

“Our program seeks to bring together the responsible youth and the person harmed for a restorative community conference,” says Songster. “Everyone who attends, in cluding both parties and their supporters, works toward a restorative plan for the young person to repair the harm. Once the youth completes the plan, no charges are filed. The young person has no record.”

It isn’t an easy path, according to Janelle Harvey, 33, a healthcare clinician.

“A group of youth assaulted me,” she says. “Staff from the D.A.’s office present ed the possibility of rehabilitation as an al ternative. The diversion was challenging. It took a bit of soul searching.” She credits her interest in behavioral health for swaying her toward the restorative-justice route.

“I kept in mind that it’s easier to rehabil itate a child than an adult,” says Harvey. “If they went to prison, they wouldn’t get the help they needed.” She also weighed the effect of peer pressure and other possible factors. “They could have been exposed to violence and pornography growing up. Yes, I was traumatized, but it could have been much worse. Most people look for money, community service, or both, as reparation, but above all, I wanted to see a change in their attitude. I saw that at the meeting.”

Songster believes that the meetings are hard but empowering for all concerned.

“The responsible youth gets a better ap preciation of the impact of their behavior on the person involved, on their family and the larger community because concerned community members attend the meetings,” Songster says. “The youth develops a great er sense of responsibility. The meetings also empower the person harmed because they

Evening Resource Center in Germantown. “It’s open from 7 p.m. to 2 a.m.,” Glasgow says. “Youth have structured activities and mentoring.”

For more information, see juvenilejustice.org or call (215) 849-2112, ext. 5506. JJC welcomes donations.

get a say in how the harm will be repaired.

Songster continues, “The most challeng ing part of the program is getting people to see that there’s a way to handle the situation besides putting young people behind bars. Sometimes, the youths are ready to partici pate [in restorative justice] but the parents object.”

Songster himself seems to find continued healing in leading the program. “Years ago, I did someone irreparable harm,” he says. “Now I can help young people succeed.”

While YASP staffers keep track of young people entering the juvenile legal system, they also take a preemptive stance. “We

have leadership-building workshops at schools and colleges to help youth avoid legal trouble,” DayOne says.

YASP also offers practical help for youths who face court dates.

“We have a Youth Participatory Defense Hub,” DayOne says. Begun in 2019, it helps show young people how to present them selves in court.

In addition, YASP helps young people who’ve left prison find employment, con tinue their education, take arts classes and rebuild their lives in other ways.

“What’s most challenging about this work is that so many institutions work against us,” DayOne says. “Fighting sys temic racism and conditioning from centu ries of oppression sometimes feels like an uphill battle.”

Yet, he finds satisfaction in furthering YASP’s goal of ending youth incarceration.

“We’re not just working to end inhu mane, ineffective and racist practices,” he says. “We’re working to build a new world where all young people have a chance.” ◆

For more information about YASP, contact info@yasproject.com or call (267) 571-YASP.

Nineteen university of Penn sylvania students were arrested for staging a protest at the Penn-Yale homecoming football game on Oc tober 22. The students, members of Fossil Free Penn (FFP), were charged with defiant trespass after storming the field at the end of the halftime show carrying ban ners and chanting, “Which side are you on?”

Prior to Saturday’s protest the students had camped in tents on Penn’s College Green, a park-like setting at the heart of

the main campus, for 39 days to pressure university administrators to make a public commitment to divest the endowment from all fossil fuel companies; establish a fund of $5-10 million to support residents of UC Townhomes, the last subsidized housing in University City, whose occupants face evic tion due to the pending sale of the site; and pay additional funds to the City through PILOTs (payments in lieu of taxes) to pro vide a greater level of support to all Phila delphia public schools.

According to an FFP spokesperson, after approximately 50 minutes of protest 13 stu dent activists were cuffed and escorted from the playing field; an additional six activists were taken into custody as they attempted to exit the area.

Following the arrests, the students staged a second protest Saturday evening in front of Penn’s Police Department on Chestnut Street to demand the release of the student activists.

Neighborhood supporters and residents of UC Townhomes joined the protest, and, with their encouragement, the students moved from the sidewalk to Chestnut Street — effectively blocking all traffic. One mem ber of the coalition spoke to the crowd about the students’ success in interrupting the live broadcast of the football game. “You guys sent them to commercials and they never came back.”

Also addressing the crowd, Kenny Chiu, a Penn sophomore from South Philadelphia, outlined the importance of their PILOTs de mand. “I’m at Penn, so it’s my responsibility now to speak of these things after seeing all of the resources given to us. It’s terrible that the University of Pennsylvania is the largest landowner in University City, but does not pay property taxes. It’s important to push PILOTs and to press Penn on its promise to serve the Philly community.”

In November 2020 the university pledged $10 million per year for 10 years to fund the removal of asbestos and improve the environ mental safety in Philadelphia schools. The university provides additional funds to two elementary schools within its boundaries: Penn Alexander and Henry C. Lea School, which serve as training grounds for Penn’s education program. Chiu and his fellow activists contend that these benefits should

be spread more equitably throughout the district. The “Penn for PILOTs” website estimates that if the university paid 40% of estimated property taxes, the contribution would be approximately $40 million per year.

On Saturday evening, as police began to discharge the students one by one, some protestors moved to the station’s back en trance to continue their chants and welcome the freed students as they emerged. After nearly five hours in custody, the last student was released.

On Sunday members of FFP announced on social media their decision to take down their tents from College Green. “Last night, we made the decision to end the encamp ment. Yesterday’s action made it clear that we will not stop fighting until we achieve our demands. We have fought for divest ment and climate justice for eight years. We slept outside and held space on College Green for 39 days. We took the field at the homecoming game. We will not stop until our demands are met.”

We will not stop until our demands are met.”

Sustainable business network of Greater Philadelphia executive director Devi Ramkissoon wit nessed the importance of local food systems firsthand in her former job with USAID in Bangladesh. While many Bangladeshi farmers are women, they are not usually the land or business owners, which had significant social, economic and environmental impacts that Ramkissoon worked to address.

“Without acknowledging the role that food plays in our social structures and in our local economies,” Ramkissoon explains, “we’re really not able to achieve equitable economic growth across the board.”

With the launch of SBN’s local food sys tems initiative, the organization is putting the focus on this critical issue right here in the Philadelphia area.

“We strongly believe that unless we’re able to address critical challenges in our local food community, we’re really not going to be able to achieve our mission of building a just, green and thriving economy,” Ramkissoon says about why this is a priority for SBN.

The initiative is broken up into three parts. The first is a comprehensive re source and network mapping of the Phila delphia region’s local food system in order to strengthen the local supply chain. This involves understanding who all of the play ers are, what their needs are, and then how SBN can act as a consolidator to help play matchmaker for all of them.

“By strengthening the local supply chain, we’re able to widen those financial margins a little bit for businesses in this sector and also improve environmental outcomes,” Ramkissoon says.

Secondly, SBN will help partners reduce waste at all points of the supply chain. For

Ramkissoon, this involves partnerships within Philadelphia City government and governments in surrounding counties to help businesses reduce waste and strength en the region’s composting sector. SBN is also looking to help businesses address their packaging waste as well by exploring partnerships with local sustainable pack aging companies.

Perrystead Dairy and LUHV Food are two immigrant-owned businesses and SBN members in the food sector whom Ramkis soon cites as examples of operations that have invested in sustainable supply chains and focus on waste reduction. Ramkissoon admires LUHV owner Sylvia Lucci’s com mitment to making plant-based options af fordable while being diligent about waste management. She similarly commends Perrystead’s commitment to localizing their supply chain by working with a near by large-scale dairy.

“Sustainability isn’t complicated, but it takes a village of people who are committed to changing the trajectory of their work to challenge this convention,” says Perrystead Dairy owner Yoav Perry.

The final component of the initiative is to support members committed to sustain able and regenerative agricultural practic

es, such as Kitchen Garden Textiles. Owner Heidi Barr not only grows the fibers that go into the textile products she makes, but also makes sure that her clientele know this sto ry, thus deepening the connection in their daily personal lives to what happens on the farm.

For Ramkissoon, a marker of the ini tiative’s success will be if they can achieve scale. Ramkissoon believes that they can reach a point where the initiative’s exam ple provides a model that other businesses, within SBN membership and beyond, can adopt to create change for the whole local ecosystem.

To make this vision a reality, SBN wel comes more members to join them — es pecially food-related businesses — to get involved with this initiative. But Ramkis soon is a big believer in multiplying impact through partnerships as well. She is looking for partners that can help SBN fulfill the ini tiative’s mission and speak with a collective voice to lawmakers on the local, state and national level to advocate for a more sus tainable and just food system.

“Our members are walking the walk, and we amplify their impact so our work in the food and agricultural sector can help spark larger systemic changes.” ◆

SBN’s local food systems initiative seeks to strengthen the relationship between sustainable farming and local foodSBN executive director Devi Ramkissoon and Perrystead Dairy owner Yoav Perry talk over cheese on how it takes a village to promote sustainable businesses.

The faces you see in this Gift Guide are part of our diverse membership community at NextFab.

F NextFab is a network of membership-based makerspaces, providing shared workshops and education in woodworking, metalworking, laser cutting, 3D printing, textiles, jewelry making, and digital manufacturing tools.

A membership unlocks access to classes, educational resources, and tools needed to build products, transform ideas into solutions, and a chance to explore making as a professional pathway.

There is hard work, handiwork, and humanity behind each thing we purchase and place in our lives. In this guide, we are peeling back a layer to the unseen stories fuel the making of beautiful products. These pieces are the culmination of the makers’ stories, experiences, skills, and passions.

You’ll meet Margaux of TWEE, mother of two who grew a sidewalk chalk business out of her kids’ classroom.

Khai Van’s engineering degrees brought to life a visual representation of the rich worlds found on your bookshelf with his company, MINI ALLEY.

You’ll see the singular moment when Jazpur gained their passion for bringing representation and joy to the world of skating through their strikingly-illustrated skateboards, HYLYTE Skateboards.

Their stories bring transparency to the heart behind the products, so you can feel proud of the gifts you give. Being a patron of their work makes you a part of their story.

Gift a NextFab membership by purchasing a gift card. Choose from one of our membership options or select a class package below (includes membership). *Gift cards can be applied to membership and class costs.*

Make your Own Picture Frame Showcase a work of art or family photo in this two-day printing and woodshop course. You’ll learn how to use our fine arts printer and matter cutter, and then build your own wooden frame in our woodshop. Open to the public, purchase this for yourself or your favorite maker. All materials included. $579.

Make your Own Custom Stool Make your own one-of-a-kind Scandinavian-inspired furniture piece, in this hands-on two-day course. Learn upholstery-making and advanced woodworking techniques through twoon-one instruction, where you’ll build your own stool to take home with you. Open to the public, purchase this for yourself or your favorite maker in the family. All materials included. $579.

Support local and national artists and The Clay Studio’s mission to make ceramic art accessible to all.

Our Shop offers handmade work by over 100 artists, perfect for your special holiday gifts.

Shop online 24/7, or visit us at 1425 N American Street to get a closer look.

Minimalist home products embedded with high-performance functionality achieved through smart design, quality materials, and artisan manufacturing.

@loma_living lomaliving.com

Handcrafted wooden diorama bookshelf inserts, “booknooks,” will tuck neatly between books on your bookcase. Imagine strolling through these alleys during a breezy summer night, checking out different restaurants for dinner, playing with a little sleepy cat on the street, or enjoying the scent of blooming flowers. Utilizing high-grade laser cutting and 3D printing technologies combines exacting accuracy, burnished with an artisan’s touch.

$150-$300 • @techarge_llc • minialley.com

Manhole covers from around the world are permanently etched into functional art, such as coasters, trivets, magnets, and wall art.

$30-$50 • @tombinoshop tombino.shop

Ever since I was little, I’ve always loved making things.

I am a tech enthusiast, crafter, and entrepreneur. I have a B.S in mechanical engineering and an M.S in electrical engineering. My business started as a hobby, and I saw the opportunity to take it to another level, so I went for it. Getting here today took a lot of hard work, creativity, dedication, and luck.”

Khai using the electronics soldering stations to create the mechanisms behind his book nooks.Creating one-of-a-kind furniture and home goods made from ethically sourced materials. This meticulous work is meant to enhance the home by offering long-lasting, heirloom-quality goods.

$100-$150 • @untitled_co_ untitledco.design

Minimalist and sculptural, ceramic wall planters are inspired by nature and derived from the junction on a tree where the branch extends out from the trunk, known as “the node.”

$100-$150 • @pandemicdesignstudio nodewallplanter.com

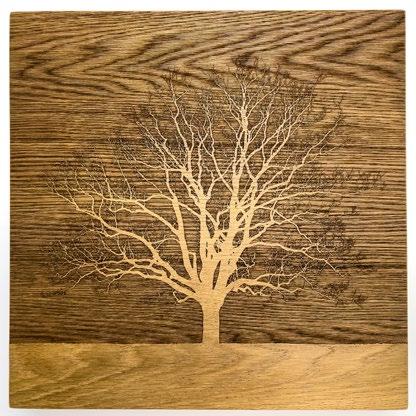

ERIC ZIPPE

Wilmington-based artist Eric Zippe Art crafts photographs transferred onto wood, laser engraved art, and fine art prints.

$10-$500 • @ezippe ezippe.art

Energy-enhancing jewelry made from up-cycled scientific glass that captures UV light and raises your vibration to create magic through jewelry.

$75-$300 • @idol.light idol-light.com

KADE BEATO

Nerdy or “witchy” in nature original art in various forms- most notably a line of unique eco-friendly wooden pins, as well as coins, tokens, and larger decorative pieces. Simple construction but endless design possibilities.

$10-$150 • @stonehoundstudios bit.ly/stonehoundstudios

Hand-crafted fish and maritime-related

to adorn your homes and boats.

customized chocolate, shaping the future of chocolate, including 3D-printed hot chocolate bombs in various flavors and colors. Pour hot milk over their geometric design to see the outer shell melt away and reveal the marshmallows and edible glitter inside.

My background is in mechanical engineering,[and] Cocoa Press started back in 2014 when I was a senior in high school. I was just interested in 3D printing, and I was interested in how you could make 3D printing into something new. So, I played around with chocolate, it was my hobby all throughout my time at Penn. And then when I graduated, I started working on it full-time. So it’s been a long journey from there to here, and it’s changed a lot, but it’s so exciting to be working on the same fundamental problems I was 8 years ago.”

Ellie Weinstein: she/her; Creator of Cocoa Press - 3D Printing Chocolate TechnologyEllie printing chocolate on her custom-built 3D-printed Cocoa Press 3D printer.

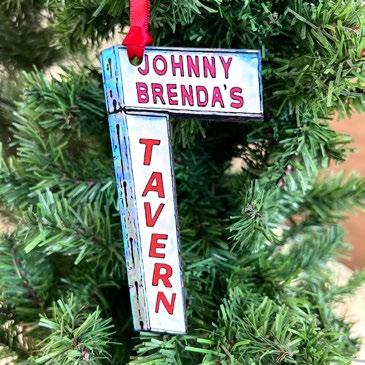

Fill your Christmas tree or Hanukkah bush with the local nostalgia of Jawnaments, offering hyper-local holiday ornaments for Philly, NJ, Delco, and beyond.

$10-$30 • @jawnaments jawnaments.com

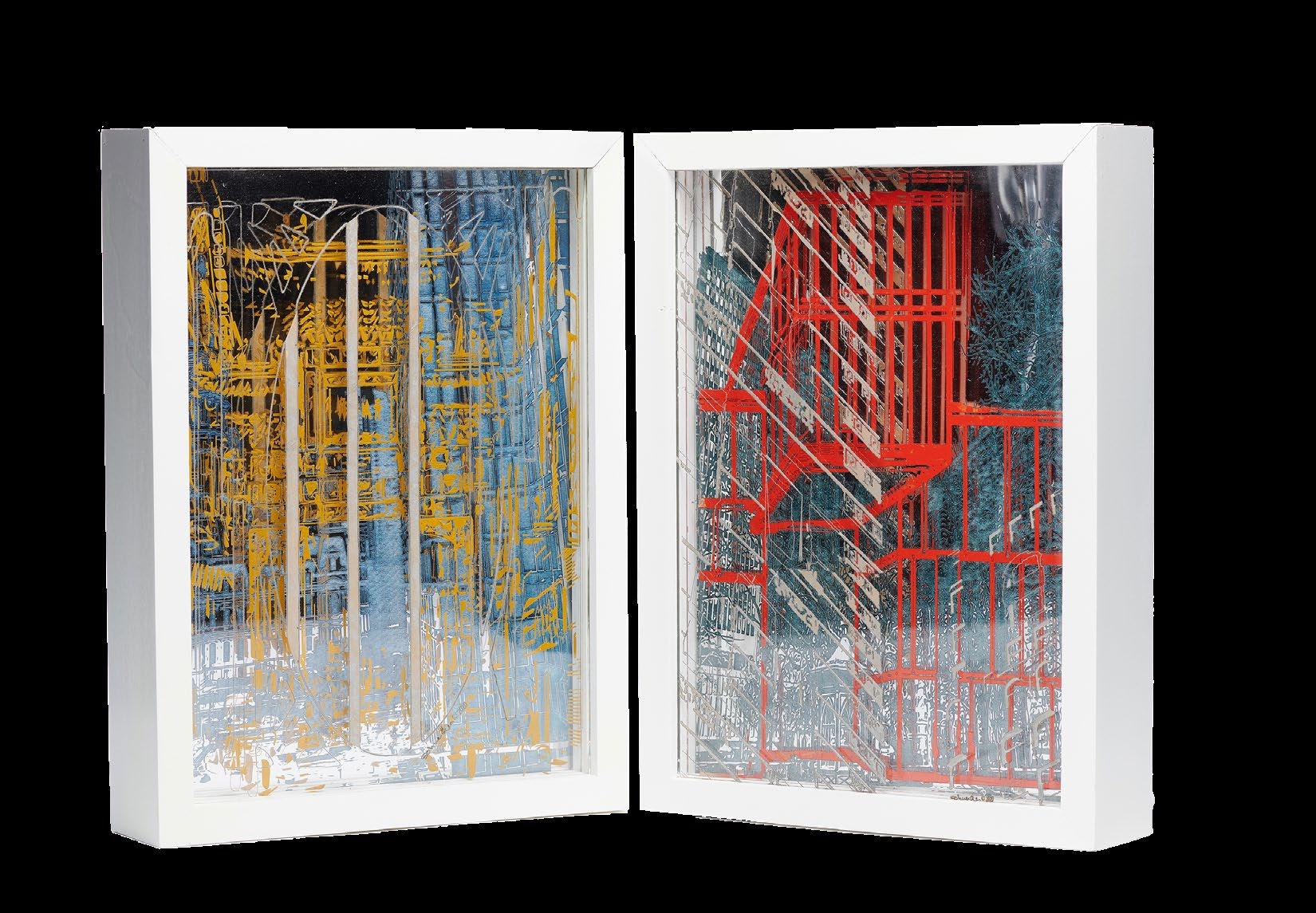

Compositional photography that portrays the past and present of place and urban landscape, created by manipulating drawings and photographs to create landscapes of the past and present of a place, building, or a person.

$300-$500 • @mariaschneiderarte mariarschneider.com

Made 100% of postconsumer recycled plastic, sourced and remade locally in Philadelphia, to create useful and practical flower pots, clocks, keychains, and more.

$10-$30 • @phillyplastico phillyplastico.com

LAUREN KELLEY

Calligraphy-based design studio that focuses on event needs, custom invitations, Christmas ornaments, and home decor.

$10-$150 • @girlholdingapen girlholdingapen.com

SARA MITCHELL-OLDS

Wooden jewelry that’s inspired by the inherent unique beauty of the material itself, by Philadelphia-based artist and RN Sara Mitchell-Olds.

$10-$30 • @hyphencrafts etsy.com/shop/hyphencrafts

Handcrafted jewelry with a vintage soul, incorporating vintage elements such as brooches, clip earrings, belt leather, and glass beads.

$10-$75 • @no27jewelry no27collection.com

CASEY LYNCH

Hand-cut paper and laser-cut wood frames, ornaments, and greeting cards to take the viewer on a journey through woodland stories and folktales.

$10-$500 • @squirreltacos squirreltacos.com

All of my art is made to be an escape from everything in the world. Whether it be traffic, stress, politics, or everything that gets you down. I want to create worlds that people can escape into. So I make shadowbox silhouettes, and they create shadows within the frame and they move throughout the day, with the sun. But, they also tell a story, whether it’s an old folklore story that you’re familiar with or a story I’ve made up that goes along with it. Everything Squirrel Tacos is for is all about escapism. It’s all about getting out of whatever’s got you down.”

Creating works of art that bring a smile to others, including stylish necklaces, earrings, tie tacks, and cuff links that are true conversation starters with universal appeal.

$150-$300 • @cartrageous cartrageous.com

PLAID (Philadelphia Laser & Industrial Design) “classic decor made fresh” products include atypically clever and beautiful cards, gifts, and goods.

$30-$50 • @laserphilly laserphilly.com

Handmade jewelry and accessory collections using new, deadstock, and upcycled vintage materials and featuring freshwater pearls and other organic elements connecting to the earth.

$75-$100 • @feast_jewelry feastjewelryshop.com

MARGAUX DELCOLLO

Woman-owned Philadelphia maker’s studio specializing in reimagined, eco-friendly, childhood classics — for playtime. Shop their “She Should Run Handmade Gingerbread Woman” Sidewalk Chalk Cut-Outs: A woman’s place is in all the houses — even a gingerbread house!

$10-$50 • @tweemade tweemade.com

ANDREW BRZOZOWSKI

Plexiglass-laser-etched ornaments, jewelry, and other household items catch and refract the sun, offering your spaces minimal flourish of generative art. These patterns are rooted in algorithmic aesthetics, mimicking movements and formations found in nature.

$10-$30 • @adhdloops adhdloops.com

My why is I truly believe that there is a market for this. I have two little boys, and there are so many things that talk down to kids. And what TWEE does, is it elevates an ordinary product (chalk) and makes it so they are able to use their imagination both in seeing it and using it. And I love that, I love that we’re promoting imagination. I love that we’re making something that is handmade. I think that is such a foreign concept to people - it’s hard for them to even understand what it means that someone is making it. My other why is that I want to see more women business owners. I want to make room for them, and I want to nurture the people, the makers here, to be their own businesses.”

Margaux using the Lultzbot 3D printer to create chalk molds.

Margaux using the Lultzbot 3D printer to create chalk molds.

Offering one-of-a-kind

pieces and custom work, ranging from simple but beautiful wood

boards to colorful furniture. If you can imagine it they can create it.

$30-$500 • @m.caseydesigns mcaseydesigns.com

One-stop shop creative agency at the crossroad of art, design, and technology, that’s passionate about bringing to life people’s ideas, solving problems, and building strategic value for brands, tech and culture.

$30-$50 • @wearemado wearemado.com

I started off as a stay-at-home mom and learned everything through YouTube University and a few classes. And my goals are simple. One, be profitable. Two, to have my art and my work in different people’s houses. Just thinking about my stuff hanging up, making someone’s house beautiful, makes me happy. Advice to aspiring makers is to do it scared. Don’t let anything stop you. You’re your only obstacle.”

Monique creating customized work on the ShopBot CNC router in the woodshop.

Monique creating customized work on the ShopBot CNC router in the woodshop.

Creating custom-shaped laser-cut and engraved imagery from your favorite photos for your graduating college grad to your beloved pets.

$50-$300 • @ema.engrave • emaengrave.com

The artistic practice of Emily Goodrum functions as an extended metaphor for the search for truth and meaning in life, using diverse methods, and materials, ranging from works on paper, wall-mounted wood, and LED sculptures, to large floor installations.

$30-$300 • @emilygoodrum emilygoodrum.com

YEMINA ISRAEL

Personal care products for men, women, babies, pets, and homes from seed using organic farming methods and hydroponics.

$10-$75 • @addinaturals addinaturals.com

LINDA CELESTIAN

Local artist Linda Celestian crafts nature crafts inspired, laser-cut wood and acrylic earrings and pendants.

$10-$30 • @lindacelestian lindacelestian.com

NIKI LEIST

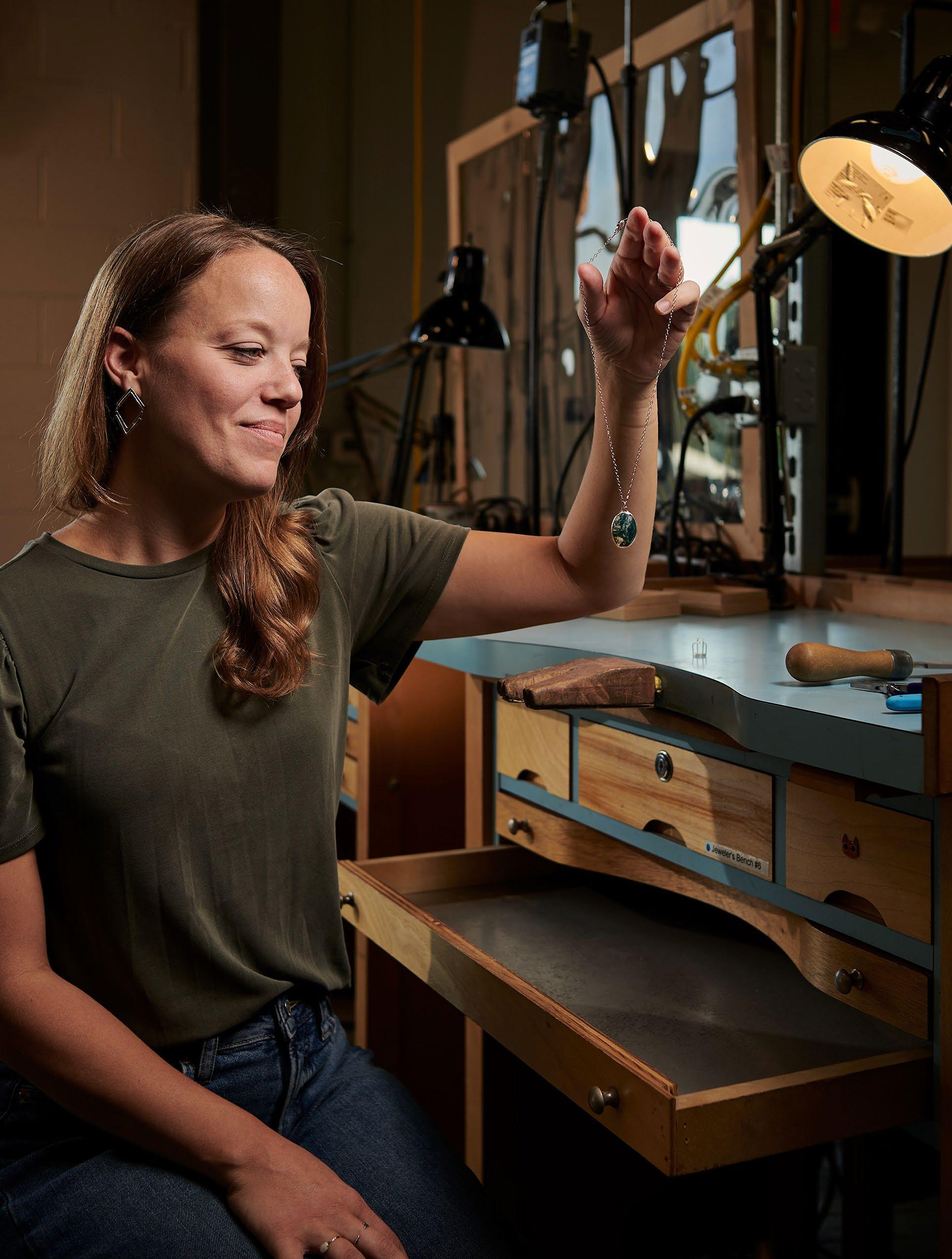

Collection of sterling silver jewelry handcrafted in Philadelphia, inspired by a connection to the earth and intentionally made to encompass organic shapes and an earthy feeling!

$30-$500 • @nikileistjewelry nikileist.com

There’s been a lot of little rewards along the way in my making journey…with my jewelry process, the textures that I can make with certain tools inspire me, certain gemstones that I use inspire me, and their shapes of them might inform the shape of the ring I’m making or the pendant I’m making. So I really just let the tools and gemstones inspire the creations.”

Niki at the shared jewelers benches with a finished jewelry design.

Niki at the shared jewelers benches with a finished jewelry design.

Handmade jewelry and accessories for the everyday fashion icon that has meaning, tells a story, and create lifelong memories.

$10-$300 • @chernealtovise chernealtovise.com

KEVIN HUANG

Fine crafts and home accessories made in glass, metal, wood, textiles, and mixed media. The artwork has been exhibited internationally and has appeared in publications in four languages.

$10-$500+ • @kevin.b.huang kevinbhuang.com

Hand-printed and hand-dyed fabrics for exquisite women’s clothing, home furnishing, and every woman’s essential accessories.

$30-$50 • @yemisi_art yemisiajayi.wixsite.com/website-9

I’ve been making and selling artwork since I was 12, and [currently] I’m making artwork with found and reclaimed objects. Part of my journey is, as I was finishing my formal education, I experienced a life-threatening illness, which took me many years to recover from. So, in the process of recovering, I started making artwork again and was able to meet people who were able to help me. During my illness, I realized it’s important to have moments of inspiration every day. My goal is to enrich people’s lives.”

Kevin B. Huang: he/him; Artist Behind Kevin B. Huang Studio ArtKevin working with the TIG welder in the metal shop to shape his sculptures.

BIPOC

brand,

creates unique

that

in small batches, along

$10-$300

@hylyteskate

I’m a 25-year-old queer, disabled skater, who got here today by working with the community to make changes where I could. One of my most rewarding memories is when I was skating in this skate park in Maryland, and this little girl looks at me straight in and says ‘I want to be a skater girl, can you help me?’ So I set her up with my smallest board, taught her the basic skills, and she took it and flew. It was so beautiful to see that. And that knowledge to hook her up with skateboards, and she can use skating — what more is there? I’m going to do this with the rest of my life.”

Jazper using the Trotec laser cutter to precisely cut her skateboards.

Jazper using the Trotec laser cutter to precisely cut her skateboards.

From the studio of artist, Bryce Bennet, these original, textured landscape oil paintings and prints, are inspired by the beauty of nature.

$30-$500+ • @BryceBennett.8 brycebennettart.com

An aerospace engineer by day, and a jeweler at night, LivetoDream plays with the intersection of science and art in three-dimensional organically flowing forms to create jewelry from precious metal wire and colorful stones, and leather and wood handbags using exotic woods and Italian leather.

$10-$500 • @livetodreamliz • etsy.com/shop/ekarasek

One behemoth of a building in Eastwick looms large, both literally and in discussions about food re covery in Philadelphia. At 700,000 square feet — about 12 football fields — the Philadelphia Wholesale Pro duce Market (PWPM) is the largest refrig erated structure in the world. Eighteen of the largest produce vendors in the MidAtlantic share warehouse space there. Busi ness as usual produces millions of pounds

of fruit and vegetable waste annually.

PWPM enters the food recovery conver sation because it exemplifies both the po tential and the precarity of our food system, and this juxtaposition suggests a strategy for addressing the twin challenges of hun ger and food waste. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service estimates that between 30 and 40% of the U.S. food supply is wasted while almost 34 million people in the United States live in

food insecure households.

“We’re wasting more than double — al most triple — the amount of food that’s needed to theoretically end food insecurity in our country,” says Evan Ehlers, founder of Sharing Excess Inc. Sharing Excess part ners with grocery stores, wholesalers and farmers to rescue and redistribute on the order of 100,000 pounds of food each week.

“There is enough food,” emphasizes Megha Kulshreshtha, executive director of Food Connect, which helps scale exist ing food recovery efforts via technology solutions, last-mile logistics support and program management. “It’s a matter of our society having the right tools, technologies, systems and people to support getting that food in a timely way to those who need it.”

For all their lofty goals, Philadelphia’s food rescue operations had humble beginnings.

Kulshreshtha, whose parents came to the United States from India with three kids and $40, launched Food Connect in 2014 as a weekend passion project while holding down a day job as a portfolio analyst.

Sharing Excess got its start in 2018 when Ehlers, studying entrepreneurship at Drex el University, converted the semester’s-end surplus in his student dining account into ready-to-eat meals and spent a lifechanging day distributing them in Center City. Before long he had commandeered his grandmother’s Hyundai to collect unspoiled but destined-for-the-dumpster foodstuffs from local grocery stores during downtime between classes.

Even Philabundance wasn’t always the multimillion-dollar force or household name it is today. Back in 1984, founder Pa mela Rainey Lawler ran the fledgling food rescue singlehandedly out of her Subaru.

But oh, how times have changed! The pandemic “highlighted many of the exist ing gaps and vulnerabilities within our food ecosystem,” as Kulshreshtha puts it, and food recovery operations have expanded in the COVID-19 era to better meet the endur ing need in what George Matysik, executive director of Share Food Program, calls “the hungriest big city in the country.”

Food Connect, for instance, has perma nently added home delivery and multi lingual technology options to the support services it offers. And Philabundance, serving nine counties in Pennsylvania and New Jersey as a member of Feed America’s nationwide network of food banks, current ly feeds 140,000 people per week, up from 90,000 pre-pandemic.

For Matysik, March 11, 2020 stands out as the day when supply chain upheaval ne cessitated a “pivot toward rescuing more re frigerated and frozen products than ever be fore.” Share Food Program has built out its refrigeration and freezing capacity over the past few years, and its staff has ballooned to more than 70 since Matysik took the helm in 2019. The amount of food diverted from the waste stream by Philly Food Rescue has grown five- or six-fold since Share Food Program acquired the nonprofit in July 2021 and leveraged its infrastructure to extend their reach.

March 2020 was even more transforma tional for Sharing Excess. A front page arti cle in The Philadelphia Inquirer on March 17 brought unprecedented visibility to the new

kid on the food recovery block, detailing ef forts by Ehlers and his team to prevent food from pandemic-shuttered eateries from going to waste. “This news piece got us 100 volun teers to sign up and become drivers,” Ehlers recalls. “We really started to grow basically in the span of 24 to 48 hours.” Soon Ehlers had rented a warehouse in West Philadelphia and converted it into a food distribution cen ter. As of September 2022, Sharing Excess had 29 employees, 11 of them full-time, and was deploying upwards of 400 volunteers to fulfill its mission of “using surplus to solve scarcity.”

Operations like Sharing Excess bring much-needed agility to food recovery efforts. “A lot of our logistics are set on systems or routines,” says Philabundance director of communications and marketing Chelsea Short, “so it’s not always easy for us to be able to jump to those immediate needs.”

Where perishable foods are concerned and viability windows are measured, as Kulshreshtha notes, in “minutes and hours, not days or weeks,” Sharing Excess’s ability to get a box of turkey sandwiches or a case of bananas from café to community center in 30 minutes or less is a game changer.

Unlike traditional 9-to-5, Monday-to-Fri day food banks, “the food industry is a 24/7 operation,” says Share Food Program’s Matysik. “So we as nonprofits in this space need to be able to respond to both our cli ents and our food donors.”

Technology enables all this prompt fer rying of food. Philly Food Rescue uses the Food Rescue Hero app to coordinate col lection and redistribution of surplus food, and Sharing Excess has developed its own open-source technology to similarly stream line logistics. It is possible in today’s smart phone age, says Kulshreshtha, to “schedule deliveries within a few seconds,” to “match thoughtfully,” and to “connect organizations and people in real time.”

The technology, of course, is just a tool,

and of little use without the network of peo ple it activates. “The most important things are our partnerships, our ability to actually go out and create these enduring relation ships, and to pick up food and deliver every day,” says Ehlers.

Ehlers stresses, too, that the people re ceiving the diverted food are also critical to the responsive, round-the-clock food res cue campaign his and allied nonprofits are conducting. While 80% of the food Sharing Excess collects is distributed by other orga nizations, it also stocks community fridges and hosts pop-ups. One especially massive giveaway made headlines in October. In a three-day event dubbed “Avogeddon,” Shar ing Excess handed out millions of surplus avocados — by the boxful — to Philadel phians thronging FDR Park. The messaging that accompanies these festive events, which often feature local musicians, is sometimes surprising to those partaking in the free food.

“Instead of charity this is more solidarity,” Ehlers explains. “This is thanking folks for be ing a part of a solution of helping us use food that would have otherwise gone to waste.”

Much less food is going to waste at the Philadelphia Wholesale Produce Market these days. Sharing Excess personnel go through every box of to-be-discarded food, glean anything edible, and get it to the likes of Philabundance and Share Food Program — pronto.

And while PWPM may be the big prize, the big headline in food rescue success, Ehlers now has his sights set on more mod est targets.

“We are really focused on this food busi ness piece,” he says of his organization’s current goals. “How can we be the best pos sible solution so that no food business ever is deciding to [send] millions of pounds of produce to the landfill? It’s like the dumbest thing ever. Not only does it not feed people, but it’s also costing them so much more mon ey than it would to just donate it.” ◆

We’re wasting more than double — almost triple — the amount of food that’s needed to theoretically end food insecurity in our country.”

— evan ehlers, founder of Sharing Excess Inc.

Christa barfield, the founder of FarmerJawn Agriculture, a mul ti-pronged organization that aims to feed wholesome food to margin alized communities while educating the next generation of Black and Brown farmers, will begin leasing the 123-acre farm at the Westtown School in Chester County.

“This land is not a gift, it’s an opportuni ty,” Barfield says of her five-year lease that she describes as market rate. “This land is a revenue stream for Westtown. FarmerJawn is scaling in order to put organic food in all Philadelphia-area communities starting with the inner city, where nutrient-dense food is needed most.”

Westtown’s previous resident farmer had been leasing the land for 30 years and is now retiring. Even though the farm consisted of diversified crops, conventional practices were used including pesticides and herbi cides. Barfield intends to use the same land to advance FarmerJawn’s mission.

“This is an expansion of FarmerJawn Agriculture, closing the loop of the Philly region food system,” Barfield told Grid. “It’s taking over 100 acres of land once farmed conventionally and doing my environmen tal duty to heal and transition to regenera tive organic.”

Inspired by her travels to the Caribbean island of Martinique, where she witnessed a community-centered food culture, Bar field set out in 2018 to start a business that reflected her new passion. She launched FarmerJawn’s initial operation — a CSA (community supported agriculture) pro gram based on a model with a century long history in the Black community — in Elkins Park, Montgomery County.

After making the current FarmerJawn CSA profitable, Barfield also recently es tablished the nonprofit FarmerJawn Foun

dation, which aims to bring urban farm ing education to schools and any Black or Brown person or group who wants to learn more about it.

“The farm is meant to be an agriculture

hub where rural training will take place as a step up from FarmerJawn at Elkins,” she says, “which will focus on being an urban ag training site through the nonprofit.”

With the lease at Westtown, Barfield is ready to expand those efforts and bring nutritious food and farming education to marginalized communities.

“I want to feed more people,” she said. “Specifically, I want to feed them regener ative organic food. That has to be the focus to really impact people and planet. Steward ing land the ‘right’ way as a Black woman is powerful.”

One major program she is looking for ward to is a food and farming incubator specifically designed to help Black and Brown people learn how they can succeed in agribusiness. In addition to expanding the CSA, she is also hoping to host cooking classes, festivals and farm-to-table meals and develop both a comprehensive agricul ture curriculum and partnerships with local universities, particularly with historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs).

christa barfield, founder of FarmerJawn Agriculture“The goal is to connect food systems around Philadelphia and to ensure organ ic food free from [herbicides] and heavy metals exists in that food system,” she said. “Having a consistent supply of nutri ent-dense food is something that is missing in our communities, and it shows.” ◆

DREW DENNIS; OPPOSITE: DAN KEMPERStewarding land the ‘right’ way as a Black woman is powerful.”

Christa Barfield is taking the FarmerJawn operation to a larger scale on 123 acres of land at the Westtown School in West Chester.

Christa Barfield is taking the FarmerJawn operation to a larger scale on 123 acres of land at the Westtown School in West Chester.

When COVID-19 suddenly disrupted supply chains, leav ing grocery shelves empty, local farmers joined the short list of essential workers. Yet, despite their critical importance, many farmers remain low-wage workers.

A report recently released by Pasa Sus tainable Agriculture revealed that farmers in our region earn about $10 per hour and family farm households struggle to reach

middle class incomes. Sarah Bay Nawa, Pasa’s research coordinator, described the findings as “a hard reality, but one that is important to share and talk about.”

Pasa’s report, “Financial Benchmarks for Direct Market Vegetable Farms,” collected financial data from 39 Mid-Atlantic farmers from 2017 through 2019. The study focus es on farms selling their produce through farmers markets, community supported ag riculture (CSA) programs, on-farm stores

and direct wholesale. This segment of the agricultural community has been growing regionally and nationally. The National Ag ricultural Statistics Service’s 2016 report tallied $439 million in sales from Pennsyl vania’s direct market farms, revenue gener ated mostly from vegetables.

Despite millions in sales, the Pasa study found that the median farm income for Pennsylvania vegetable farmers is $18,549, which barely exceeds the state’s poverty level of $17,420 for a two-person household.

Faced with such dismal economic oppor tunity, why would anyone choose to farm? And what, if anything, can be done by and for farmers to enable them to earn their way into the middle class?

Several farmers who took part in the Pasa study reflected on how the findings match their experience.

Bob Todd describes his one-acre Down to Earth farm in Downingtown, Chester Coun ty, now in its 13th season, as an oversize garden, human in scale and so intensively cultivated with hand labor that there’s no space for weeds. Todd grew up eating meat and potatoes in Kansas, surrounded by farms growing commodity crops, not food for people. He has a degree in economics but was drawn to farming for the quality of life. “I don’t know any family who doesn’t want to make a little bit more money, but I hope [the Pasa study] doesn’t discourage people from getting into farming. I think every body should have a small farm.”

Taproot Farm owner George Britten burg contributed his farm data to the Pasa report to help other farmers have access to information he could have used as a new farmer. Starting out he found no data about how much farming income he could expect. “It was almost terrifying in the beginning. It took faith that we would pull through,” he recalled. This fall, wrapping up Tap root’s 13th season in Shoemakersville, Berks County, Brittenburg is unequivocal about his career choice. “I love what I do, period. Sure, there are days when I wish I could just go to the beach for a week, but my day-to-day experience is rewarding in a lot of ways, including my contribution to my community.”

Unlike Brittenburg, Aimee Good and her husband, John, apprenticed on a number of small farms in Massachusetts that gen erously shared their financial information. The Goods knew enough to understand that farming was not a sure route to wealth. “But if you want a good life,” Aimee says, “then you go into farming.”

After earning degrees in biology and environmental science, Aimee and John decided to do “some fun work” on a farm before getting real jobs. That summer job hooked them, and they’ve been farming for 20 years. The Good Farm CSA in Germans ville, Lehigh County, raises certified organic produce on 10 acres for a 250-person CSA. Aimee believes the rewards of farming go well beyond the monetary. At the end of ev ery day, farmers see the tangible outcome of their work while enjoying the benefits of fresh air, exercise and feeling like they are making a positive impact in the world. Ai mee adds: “Our kids know we don’t have a lot of money, but they feel they are rich — we live in a beautiful place, we have great

food and we eat like kings.”

Bill Kitsch, senior executive vice presi dent for Ephrata National Bank and a re viewer for the Pasa study, has been making agricultural loans for over 20 years. He knows the role idealism often plays, espe cially among organic and sustainable farm ers. “They’ve chosen to farm because they want to make the world a better place. They might feel they should get paid for making the world a better place.” But as Kitsch and all successful farmers know, farming is a complex, extremely challenging business.

“I’m guessing 85% of the people from the study didn’t get into farming thinking of it that way,” Brittenburg says. But I realized [business] was my steepest learning curve, and I made it a point to figure it out.” “Farm ers are into plants, not finance, and learning the business side is not what brought you to farming,” Aimee acknowledges. “But you have to do it.” Todd shares that view: “You can be so idealistic as a farmer, but if you’re not practical you can’t be sustainable.” He hopes the study speaks to farmers and en courages them to find a way to make their farms profitable.

The Pasa report, aimed chiefly at farmers, offers several valuable business insights. The study found that no single directmarket channel delivers superior results. If access to land and other resources like labor

are available, farming on a larger scale often brings higher income. Farms specializing in vegetable production may have solid mar gins on vegetable sales but may be missing opportunities for additional revenue they could earn by reselling complementary products from other farms. And some good news: over time, farmers build income and equity, making their businesses more prof itable the longer they operate.

The study concludes, however, that the systemic economic challenges farm ers face cannot be solved by the farmers alone. Public programs are needed to help direct-market vegetable farmers provide fresh, nutritious food for their communities. The study advocates for new or expanded initiatives to specifically tackle “equitably increasing farmland access, improving mar ket opportunities, encouraging workforce development, reducing financial risk, and rewarding conservation best practices such as building soil health, protecting wildlife and improving water quality.”

Although Kitsch found no surprises in the report, he is already using the data to modify Ephrata’s lending practices. Moreover, he believes the study can and should have an impact beyond the banking community. U.S. farm policy, he feels, has always had a significant bias against sus tainable agriculture versus conventional,

I think everybody should have a small farm.”

bob todd, owner of Down to Earth farm

large-scale commodity farming, and it has always been an economic question. For Kitsch “the benchmark study was all about getting into specialty crop farming and looking at the economics, uncovering what are some of the general themes that increase the probability of success.” In his view, the study validates a sustainable approach to farming and should trigger a shift in public policy, starting with the PA Farm Bill.

Aimee has hopes for the study as well. “We need to figure out a way for major change to happen in the food system so farmers can make a living and so all people can afford good food. We knew this to be true, but the study provides the scientific research to prove it.”

Until such changes occur, the challenges facing beginning farmers remain signifi cant. Amirah Mitchell began working on farms as a teenager. With financial support from a successful GoFundMe campaign and a fellowship, she is finally realizing her dream of farming full-time. Mitchell aspires to build a farm business based on heirloom vegetable seed production with a focus on crops from the African diaspora.

Currently she is gaining hands-on farm ing and business experience through The Seed Farm’s Farm Business Incubator pro gram in Emmaus, Lehigh County. Mitchell describes her decision to farm, as “more of a calling than a choice,” though she admits her financial future is full of unknowns and requires some blind optimism. “Farming is something that we do for the love and the passion for the land. But there’s a lot of ex ploitation in this industry. We’re underpaid. A lot of that is systematic and part of the food system and the government structures we exist under. There are things that can

help. Buying direct from a farmer makes a huge difference for our profit.”

Bay Nawa, of Pasa, shared her vision for the study’s impact. She thinks it can further an understanding of what the farm commu nity faces and foster a willingness to inspire change and improvement. Customers can really see what their farmers are doing and

come to realize that we all need to eat, and we all wish to live in vibrant communities that include agriculture. Finally, the report urges “farm organizations and policy mak ers to create some structural changes we know would be helpful for the local food community. We hope this strong grounding data will make change happen.” ◆

written and illustrated by bryan satalino with research assistance by adam dusen