SEPTEMBER 2023 / ISSUE 172 / GRIDPHILLY.COM TOWARD A SUSTAINABLE PHILADELPHIA

and politicians disregard the risk, but the water will come page 14 A

captures the staggering devastation that befell the Apex Manayunk luxury apartments in September 2021.

PLAIN SITE

Developers

man

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 5 11AM – 4PM | KIMBERTON FAIRGROUNDS EPIC FARMERS MARKET LIVE MUSIC - FOOD TRUCKS - POURING ROOM CULINARY DEMOS - KIDS ACTIVITIES & MORE @goodfarmsgoodfood GROWING ROOTS BROUGHT TO YOU BY PREMIER SPONSOR TICKETS & MORE

THE BENEFITS OF PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION GO FARTHER THAN THE END OF THE LINE

Public transportation bene ts the environment by reducing the number of people driving single occupancy vehicles. Even if you ride the bus, train, or trolley just one time this month - you can help lower the world's greenhouse gas emissions - which slows climate change and improves air quality. Plan your trip at ISEPTAPHILLY.COM.

publisher

Alex Mulcahy

managing editor

Bernard Brown

associate editor & distribution

Timothy Mulcahy

tim@gridphilly.com

copy editor

Sophia D. Merow

art director

Michael Wohlberg

writers

Kiersten Adams

Kyle Bagenstose

Bernard Brown

Constance Garcia-Barrio

Adam Green

Dawn Kane

photographers

Chris Baker Evens

Troy Bynum

Chloe Elmer

Gene Smirnov

Rachael Warriner published

Do As I Say, Not As I Do

Anyone who has raised children knows the frustration of watching a kid imitate your worst habits. Maybe you hear them swearing, exactly how you do. Maybe you tell them to get off their phone, and then they catch you checking yours under the table at dinner. Maybe you tell them to eat better, and you see them spooning ice cream directly from the carton, just like you did the night before. The Partnership for a Drug-Free America got it right in 1987: they learned it by watching you.

It is critical that we educate our children on the best ways to reduce our negative impact on the planet: how to reduce air pollution, how to produce food sustainably and how to build creative solutions to their problems, today and in the future. But kids won’t value nature if you never take them outside. Lessons about food waste are as good as garbage if you end up pitching the leftovers. And it is probably pointless to talk about the importance of fighting global warming while cranking up the thermostat in a large house, driving everywhere you need to go and flying halfway around the world for vacations.

The importance of example rather than words applies in public policy as well. It is hypocritical for politicians to talk about climate change resilience while greenlighting development projects that place Philadelphians in the path of future disasters. But as we’ve seen from decades of mismanagement, jobs for construction unions and the profits of wealthy developers trump the safety of citizens who live and work in floodprone parts of the city.

Keep in mind that the same mayor, Michael Nutter, who started the Office of Sustainability in 2009, pushed hard to permit building on Venice Island 10 years earlier when he was on City Council. The City’s

All-Hazard Mitigation Plan has for years clearly stated the importance of integrating disaster risk information into how we plan where to build. Goal 2.4 of the 2022 version of the plan reads, quite directly, “integrate hazard and risk information into land use planning decisions.” But elected officials have continually overruled the advice of planners and disaster experts who have tried to put those words into action.

Anyone who has raised children knows we only have so much influence over how they’ll turn out. Their genes are locked in at conception. They spend most of their day away from us in school, hanging out with their peers or staring at screens. Our consumer economy reaches its tendrils into their brains through brand placements and advertising with the nearly irresistible message to buy first and think later. And at some point they will leave the house and keep developing as humans even further from our influence.

In some ways cities are easier to shape. Zoning regulations and processes offer the levers to control who builds where. There is technically nothing preventing councilmembers from actually listening to the experts and wielding their councilmanic prerogative to prevent the construction of dangerous housing. Unfortunately, after years of examples to the contrary, we know what to expect, no matter what they say.

bernard brown , Managing Editor

by Red Flag Media 1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107

215.625.9850 GRIDPHILLY.COM

EDITOR’S NOTES by bernard brown

COVER PHOTOGRAPH BY CHLOE ELMER 2 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 3 EDUCATION THAT MATTERS | KIMBERTON.ORG 610.933.3635 GET YOUR COURAGE UP! Waldorf kindergarten preserves the most important elements of childhood and allows imagination and confidence to bloom. Discover the warm and magical setting of our two-year program. The Learning Never Stops Discover new K-12 education opportunities waiting for you at the Pennsylvania Cyber Charter School! Call 724.643.1180 or visit pacyber.org to start your PA Cyber journey today. The Learning Never Stops To learn more ...

The Grape War

Grapevines, harmful to urban tree canopy, may be falling victim to spotted lanternflies by bernard brown

Ihave paused my war on grapevines. They just aren’t putting up much of a fight anymore.

“War” might be putting it strongly, but for nearly 20 years I have cut them down whenever I have had the opportunity and the tools in hand (loppers, or a pruning saw for the big ones). Lately pretty much all the Philly grapevines I find are already dead.

Now, anyone who is familiar with wild grapevines knows they can look kind of dead in the best of circumstances. The leaves are often high above the ground where they’re hard to spot, while below the

bark peels off their gnarled, saggy stems. But you can tell the difference as soon as you get past that bark. The live wood is soft and damp. Dead vines have a dry corky texture that catches at steel as you cut through.

“Cut on sight” is the standard order for vines draped from trees in urban parks. Oriental bittersweet, English ivy and even the native grapevines can weigh a tree down to the point that it becomes vulnerable to tipping over or losing branches.

It is not the vines’ fault. They have evolved to take advantage of forest edges or other breaks in the canopy. Without shading tree

leaves, the vines benefit from sunlight hitting them broadside. In a larger, intact forest, grapevines dragging down a few trees is just nature at work, but in narrow urban parks with lots of edges, they can add up to a problem. So park volunteers and professionals clear vines from trees as a matter of course.

Eurasian species of vines provide the grapes we eat and the juice we drink (fresh and fermented). We grow them in neat vineyard rows where they barely resemble their wild cousins. Those domesticated vines grow, however, from the roots of some of the same species we clear off of trees in our parks. In the late 1800s a tiny insect, grape phylloxera, devastated domesticated grapevines in Europe. The bugs, native to North America, killed grapevines by feeding on fluids from their roots, so the solution was to graft the vulnerable vines onto roots from American species of grapes, which had

4 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023 PHOTOGRAPHY BY RACHAEL WARRINER urban naturalist

evolved with the phylloxera and thus had natural resistance. The North American grape species saved viticulture, but in the woods where they grow wild, humans have largely forgotten them.

Nonhuman animals, however, remember.

Wild grapes feed bears, raccoons, turkeys and all sorts of other critters. They can also be yummy for humans to munch on. But since, unlike the trees they grow on, they produce no wood and are often regarded as tree-felling pests, state agencies that deal

with forests tend not to do much to protect them. And until now they haven’t seemed to need protection.

I don’t know what is killing off the grapevines, but I’ve got a guess: everyone’s favorite bug villain, the spotted lanternfly. Concern about cultivated grapes and other crops has driven the all-hands-on-deck reaction to the East Asian plant hoppers. Spotted lanternflies can be harmful to lots of plant species, but they are particularly lethal to grapevines. There has been little research on their effect on wild species of grapes, but I see no reason to assume that the lanternflies would hurt them any less than they do the cultivated grapes.

Insecticides have proven to be effective at killing spotted lanternflies in vineyards, which already have to spray for other insect pests — like Japanese beetles — that would otherwise devour the cultivated grapevines. But spraying millions of acres of forest with insecticides is both impractical and probably a bad idea for other reasons. The wild grapevines are on their own.

But even economically important plants can’t easily be saved from exotic pests. The emerald ash borer, a shiny beetle the size of a grain of rice, is ravaging North America’s ash trees, essentially wiping them off the continent. The best anyone can do for this ecologically and economically important tree in the short term is to treat a few larger ash trees in parks and gardens. Researchers are working on longer-term solutions such as distributing tiny wasps that afflict the ash borers, but those will take decades to make a dent on a continental scale.

I still have a lot of questions about the fate of the grapevines. On my own I have observed that grapevines in more remote areas, even within the lanternflies’ terrain, seem to be doing better than those in Philadelphia. Perhaps it matters how close they are to trees of heaven, the lanternflies’ favorite host plant, which are more abundant in urban settings.

Maybe someday the lanternflies will meet their match and we’ll know whether they were what won the war on grapevines. Until then, I will remain a neutral observer. ◆

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 5

Spotted lanternflies can be harmful to lots of plant species, but they are particularly lethal to grapevines.

Opposite: Bernard Brown cuts into a wild grapevine. Despite being native, grapevines should be “cut on sight” from urban trees, as they can weigh them down. This page: Spotted lanternflies are the author’s prime suspect for the collapse of urban grapevines.

Blazing Trails

Camden kids build a pathway to environmental careers through fellowships

by kyle bagenstose

by kyle bagenstose

It was a muggy morning, on a midsummer Wednesday, and the fish weren’t biting. A dozen or so preteens kept dropping their baited lines into the water from a dock and pulling them out empty. Or often, tangled, requiring repeated assistance of nearby camp counselors.

A tedious exercise? Perhaps. But just beneath the surface were incredible, bountiful fruits. Here in Camden, the poorest city in New Jersey, where many parents keep their children indoors and away from the dangers of the street, were kids acting like kids. Getting their hands dirty. Hooking worms. Looking out into the natural world and asking, “What’s that?”

Officially, the day was a medley of organizational collaboration in the city’s Cramer Hill Waterfront Park, situated along the confluence of the Cooper and Delaware rivers. The kids were campers of Ignite, a summer program hosted by the Rutgers University–Camden campus. Providing the equipment and know-how was the Camden-based nonprofit Center for Aquatic Sciences. And leading the activities were three fellows of the Alliance for Watershed Education, a collaboration among two dozen regional environmental organizations to foster love for the Delaware watershed.

If that’s too much to keep straight, no problem. The most important connection was between the fellows — former Camden kids now blazing trails into professional careers in the environmental sciences — and the young charges who might just follow in their footsteps.

“My mom was a very protective parent. Unfortunately, there were a lot of threats around my particular neighborhood. You’ll see people standing on the corner, you’ll hear the shootouts,” said Jackie Valerio, an Alliance fellow with Camden County Parks.

As a former student of Camden Academy Charter High School, Valerio, 19, had gravi-

tated toward forensic science. But after volunteering to help out former Alliance fellow Anthony Lara, who had an interest in native aquatic celery grass in the Delaware, Valerio became hooked on the outdoors. Now studying biology at Camden County College, Valerio has plans to transfer to a four-year college and ultimately become a marine biologist.

6 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023 PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

water

Jackie Valerio and Anthony Lara introduce Camden youth to fishing, and to the Delaware River, through the Alliance for Watershed Education.

“That’s where I became more environmental … just working with the program and being exposed to different interesting topics, like watersheds, like aquatic animal physiology,” Valerio said. “Especially working handson, that’s an aspect that really changed me. It’s really cool going home to my mom and being like, ‘I held a snake today, I held a python, I held a horseshoe crab.’”

Lara, 25, is at the front of the pipeline. Also a Camden Academy graduate, Lara went on to receive a degree in physics from Stockton University, near Atlantic City. But not knowing exactly where to go next, he became an Alliance fellow with Camden County Parks in 2021. He wanted to build an underwater rover to assess the health of the diminished celery grass, which serves as both an important habitat and a food source for native species. But after encountering difficulties, he instead focused on starting up a successful public kayaking program in the midst of the pandemic.

No matter: Valerio has taken up where he left off. Lara, now an experiential programs supervisor at the Center for Aquatic Sciences, oversaw Valerio and two other fellows for 12 weeks this summer. With scientists working to study the health of celery grass in the river and support its propagation, for her fellowship Valerio chipped in, conducting by-sight field surveys and working to finally build the video-capable underwater rover that Lara dreamed up.

For Lara, it’s seeing history repeat itself.

“When I was a kid, I didn’t have a lot. My first time on the water was because of the fellowship. The first time I kayaked, the first time I fished,” Lara said. “The significance of the program is to give those in the area … a chance to dive into the environmental field. These 12 weeks allow them to develop and grow.”

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 7

I feel like we have a responsibility to at least mitigate the damage we have done so that all organisms can continue living.”

— nyraysia robinson, Alliance for Watershed Education fellow

Black faces in white spaces

Growing up in Camden, Nyraysia Robinson, an Alliance fellow with the New Jersey Natural Lands Trust, found herself drawn to the natural world. But with nearby opportunities sparse and parents also concerned about her safety, most of Robinson’s education came through TV programming like Nat Geo Wild, Animal Planet and nature documentaries.

“Those shows got me into really wanting to help protect the animals that live here, and all around the world,” Robinson said. “I feel like we have a responsibility to at least mitigate the damage we have done so that all organisms can continue living.”

After high school, Robinson also found her way to Stockton, where she graduated last spring with a degree in environmental science and a concentration in wildlife management. She’s hoping to enter the field with the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, but in the meantime she spent her summer fellowship building a three-dimensional model of Petty’s Island. A 292-acre slice of land wedged between Camden and Philadelphia’s River Wards, the island is currently undergoing transformation from industrial site to nature preserve. Robinson’s model, which she learned to build via YouTube, will help educate the public on the changes.

But the fellowship has offered something else: connection to those who know what it’s like to walk in her shoes. As is the case for many Black people working in the sciences, Robinson is often the only non-white person in academic and professional spaces.

“I always felt it wasn’t really my place to get into [science]. Even at Stockton, I was still the only Black kid in class, which was a big transition from the urban environment,” Robinson said. “It was like, ‘Now that I’m in the real world, I am alone here.’”

But with the fellowship emphasizing selection of diverse candidates and building community as the years go on, Robinson suddenly found she wasn’t on her own.

“I was pretty surprised by how many Black environmentalists around my age were really into the environment,” Robinson said. “The diversity of people that I found was really exciting. I was like, ‘This is the group. This is what I’ve been looking for.’”

Giving back

Xianny Jimenez isn’t quite sure where it all started for her, but she knows that she loves animals and wants to protect them.

The 19-year-old Camden native is studying to become a veterinarian at Montclair State University in North Jersey, and on a whim she reached out to the Camden Aquarium for an internship. That landed her an Alliance fellowship with the Center for Aquatic Sciences, which is housed there.

For her fellowship capstone this summer, Jimenez made a model of Camden and its surroundings to help people understand how litter, sewage and other pollution in-

filtrate the area’s waterways when it rains. It should pay dividends as the torch passes down to the next generations: Camden kids who get hooked on the outdoors through the fishing and paddling programs, then come to understand how their actions affect the health of the rivers and creeks and what they can do to help.

“It’s a big thing for us in this program, because when we go kayaking after it rains … you don’t want to be kayaking in dirty water,” Jimenez said. “I found it really interesting because it was with Camden. That’s one of the things I loved about it, because I grew up here.” ◆

Bad Air

The clerk at the Dollar Tree is telling a story to the next clerk over. “And that’s how my godson died.” I ask if I can pay with debit. This Dollar Tree, which is located downwind of a factory that produces mystery meat and sewer gas, also deals in helium and remaindered copies of Zoolander. “Yes,” she says. As I’m leaving I hear the clerk say, “It was a hot, humid day.” She’s starting from the beginning again. I linger by the sticker machines, fishing around in my pockets for quarters, stalling for more time. “The boy always had really bad asthma. Do you need a bag?”

8 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023

water poetry

It’s really cool going home to my mom and being like, ‘I held a snake today, I held a python, I held a horseshoe crab.’”

— jackie valerio, Alliance for Watershed Education fellow

—Dan Shurley

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 9 www gtms org info@gtms org American Montessori Society Accredited Tuition Assistance Available School Day and All Day Montessori Toddler through Third Grade 55 N. 22nd Street, Center City, Philadelphia It all begins here. Join us for an Open House on OSaturday, ctober 14! Activists & Athletes & Artists. We prepare students for the whole of life. OPEN HOUSES Tuesday, Sept. 19 at 8:45 a.m. Grades PreK & K Saturday, Oct. 7 at 9:30 a.m. Grades PreK–12 The Only Pre-K to 12 Quaker School in Center City. NeedsYou! Support local journalism by subscribing or donating Pay what you can on PayPal or in our store STORE.GRIDPHILLY.COM PAYPAL

Showing the Way

Docent collective gives energizing presentations on local Black history by constance

The late autumn wind began to bite during the 1838 Black Metropolis walking tour last year, but historian Michiko Quinones warmed the 10 participants with stories of riches, a riot and secret dealings in Philly’s antebellum Black community.

“Some 20,000 Black people lived in Philadelphia in the late 1830s,” Quinones said. “The 1838 census showed that their property had an aggregate value of $40 million [in today’s dollars].”

garcia-barrio

Quinones and Morgan Lloyd, a historian and curator, first presented the new walking tour as members of the Black Docents Collective, a group that started in response to the isolation of the pandemic. The collective’s approach and the tour that threads through cobblestone alleyways have resulted in a look at little-known facets of Philadelphia’s Black history.

“Most of us were volunteer guides at the African American Museum in Philadelphia [AAMP],” says Richard White, president

of the collective, which currently has nine members. “When AAMP closed during the pandemic, we wanted to keep getting together to bring the city’s Black history to light. We’re historians, we’re griots,” says White, referring to African storytellers who preserve a people’s oral tradition. “We don’t necessarily have degrees in Black history, but it’s our passion. We’ve read books, traveled to Africa, done archival research, collaborated with scholars and listened to oral histories. We bring that knowledge to bear.”

The docents seek “to educate, empower and heal the Black community by celebrating its history, culture and African values,” the collective’s mission statement says.

“If Black Philadelphians learn about the accomplishments of our ancestors, we can

10 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023

healing city

PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

Michiko Quinones (left) and Morgan Lloyd take African American history to the streets of Philadelphia as members of the Black Docents Collective.

draw on that knowledge to face our struggles today,” White said.

The walking tour tells stories of Black residents who lived between 12th Street and the waterfront and from Locust Street to Catharine Street.

The tour began at 224 S. 12th Street, former home of brave free-born abolitionist and businessman William Still (1821–1902). An Underground Railroad agent, Still took a huge risk in keeping records of fugitives he helped in Philadelphia — an illegal activity — so that family members could find one another later. In the course of his work,

Still was reunited with his brother, Peter, kidnapped into slavery years earlier, when Peter’s flight to freedom took him through the city, Quinones explained. Quinones also mentioned that William Still was said to have hidden his records about fugitives in a graveyard so that the information wouldn’t fall into the wrong hands. Known for publishing “The Underground Railroad Records” in 1872, Still also published “A Brief Narrative of the Struggle for the Rights of Colored People of Philadelphia in the City Railway Cars” in 1867.

The 1838 Black Metropolis tour got its

name and focus from the 1838 census commissioned by the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and carried out by Charles Gardner, pastor of the First African Presbyterian Church, and society member Benjamin Bacon, Quinones said. In 1838, Black men in Pennsylvania found their right to vote threatened, she explained. The 1838 census aimed to prove that Black Philadelphians worked hard, held property and provided for their own poor folk and therefore should not be stripped of the right to vote. (Community leaders involved in trying to save the vote included sailmaker James Forten, his children and Robert Purvis, Forten’s sonin-law, all featured in “Black Founders: The Forten Family of Philadelphia,” an exhibit at the Museum of the American Revolution through November 26, 2023.)

richard white, president of the Black Docents Collective

The Philadelphia Transportation Company strike of 1944 was a turning point for the city’s Black community. When eight Black men were promoted to non-menial jobs, thousands of white workers went on strike. President Roosevelt sent in 5,000 troops, and the strike was called off within days, opening up great opportunity for hundreds of Black transit workers.

“The push to disenfranchise Black men came about because they voted in high numbers,” Richard White said. “Their votes made the difference in an election in Columbia County, Pennsylvania. Legislators in Harrisburg feared that power.”

The bid to save their vote failed, but it resulted in an invaluable fact-packed document that provides the foundation of the walking tour.

During the tour, Quinones tossed in juicy tidbits about whites living in the area. She pointed out the Pennsylvania State Historical Marker at 258 S. 9th Street, one-time home of Joseph Bonaparte (1766–1844), the older brother of Napoleon Bonaparte. “Frenchmen, including Stephen Girard, used to party here,” Quinones said. Girard reaped a fortune in the illegal opium trade with China, she added.

Quinones ended the tour where the home of Hester “Hetty” Reckless (1779–1881) once stood. Originally enslaved in Salem, New Jersey, Reckless fled with her daughter after the wife of her enslaver, Colonel Johnson, reportedly knocked out Reckless’s front teeth with a broomstick. Reckless slipped away in a stagecoach and eventually settled in Philadelphia. In 1844, she established the Moral Reform Retreat for Black Women at 7th and Lombard Streets.

“This was a shelter [run] by a Black woman for Black women,” Quinones said. Reckless wanted to protect the women from both slavery and sexual exploitation.

Quinones and Lloyd started a nonprofit, 1838 Black Metropolis, in April to hone in on people and events cited in the 1838 census.

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 11

If Black Philadelphians learn about the accomplishments of our ancestors, we can draw on that knowledge to face our struggles today.”

TEMPLE URBAN ARCHIVES

The black docents collective provides a treasure trove of Black history on its website, blackdocents com. For Juneteenth 2022, for example, members showcased seven Black micro-museums in individual YouTube sketches.

“Each museum shows a different aspect of Black history and culture,” White said.

The videos cover sites like the Richard Allen Museum, on the lower level of Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, 419 S. 6th Street, the nation’s oldest A.M.E. house of worship. The museum has artifacts like Allen’s Bible and houses the archives of “The Christian Recorder,” the oldest continuously published Black newspaper in the country.

The museum mini-series also has useful incidental details. For instance, the Peter Mott House, a two-story farmhouse in Lawnside, New Jersey, once sheltered fugitives from slavery. The 1844 building, now on the National Register of Historic Places, hosts an annual weeklong Underground Railroad day camp for children.

The website also features short presentations on turning points for Philly’s African Americans, like the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) strike of 1944. On August 1 of that year, during World War II, the PTC promoted eight Black men from menial jobs to trolley motormen, a position previously reserved for whites. Some 4,500 white workers went on strike, crippling the city’s buses and subways in addition to the production of war materials because people couldn’t get to work. When negotiations with the strikers failed, President Roosevelt sent in 5,000 troops armed to the teeth who set up camp in Fairmount Park. The soldiers rode the trolleys to protect passengers and PTC employees who’d returned to work. The strike ended when authorities threatened to revoke strikers’ draft deferment. By August 17, the soldiers left Philadelphia. Two months later, the number of Black motormen had doubled.

The collective’s website also offers indepth discussions of topics like Kwanzaa, a holiday observed from December 26 to January 1. Kwanzaa celebrates seven values of African culture: unity, self-determination, collective responsibility, cooperative eco-

Trying to Relax

A shirtless man is practicing cross-country skiing on the jogging path by the Art Museum. Up the hill he goes, down the hill he goes, in sweating long strides, as we endure the hottest summer ever recorded. A squirrel would like to utilize the tree whose trunk supports my back. “As soon as I finish reading this summary of the IPCC’s latest climate report,” I tell the squirrel. (It’s not good.) A column of dirt bikes snarls across the bridge, arresting the ivy in its climb. That’s another thing Krasner’s office stopped prosecuting. I’m resting after four hours of writing copy for a defense attorney who would like a bigger piece of the DUI pie. Sometimes my words work for the wrong side. Musk of the Schuylkill wafts up the steep bank. An ice cream truck hovers in the sky over the river, the freight train bearing Bakken crude sharpens its rusty wheels on our naked ears. A river rat stops to say hi to the squirrel, scurries off when it sees me, both of us equally spooked. Graffiti heads faster than the one CLIP guy tasked with removing the evidence of their existence. What else? A toddler strapped onto the back of his father’s electric bicycle enjoying a smooth ride, a barge ship blaring its horn. In personal locomotion, the law of minimal effort. In politics, the law of maximum inconvenience. In the animal world (that’s us!), the law of the squeaky wheel. In music, kick drum and high hat and sweet falsetto voices, please. I’m trying to relax.

—Dan Shurley

nomics, purpose, creativity and faith.

“In my talks I relate those principles to Philadelphia’s Black history,” White said. “For example, I relate cooperative economics to the 19th-century Black mutual aid societies and the savings and loan associations that some churches had,” said White, who gives presentations at churches and other community groups.

“We recognize that we have to create relationships with schools and other organizations,” White said. “Our partnerships with

the Center for Black Educator Development helps us reach young people. We’re also partnering with a group at [the University of Pennsylvania] and with Swarthmore College. Our ultimate goal is for Black Philadelphians to take control of our own historical narrative.”

To learn more or join the Black Docents Collective, visit blackdocents.com. To book a tour with 1838 Black Metropolis, which covers eight blocks and lasts about an hour, visit 1838blackmetropolis com

12 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023 poetry

healing city

◆

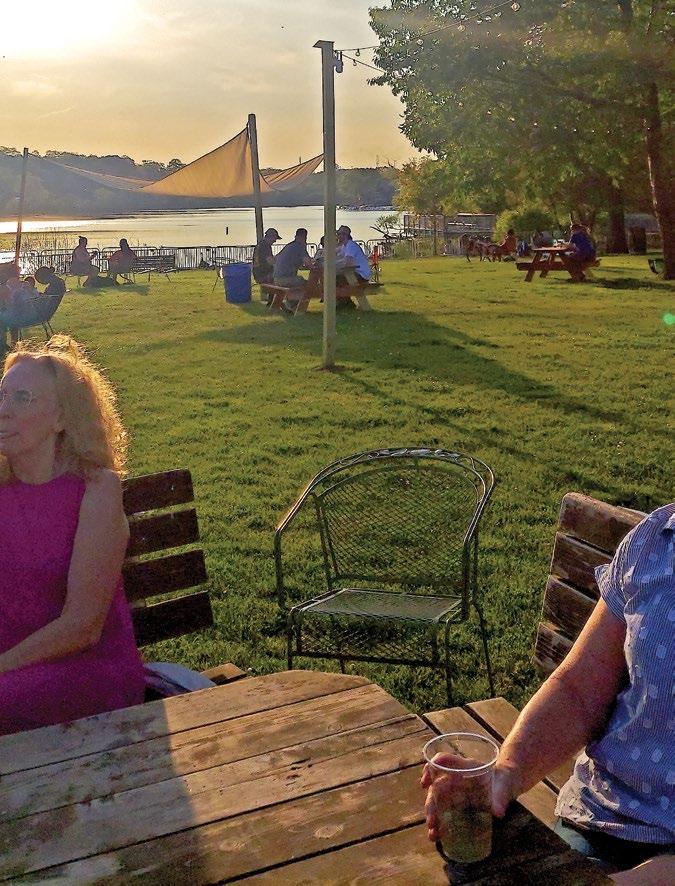

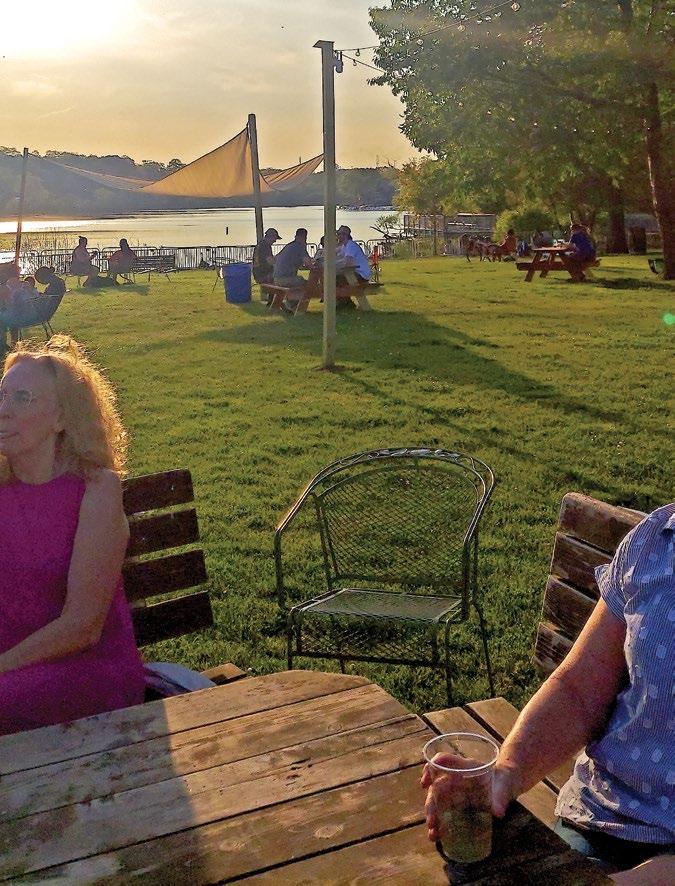

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 13 Come visit our New Beer Garden at our new location: 640 Waterworks Drive Philadelphia, PA 19130 Hours: Thursday & Friday 4pm to 10pm Saturday Noon to 10pm Sunday Noon to 9pm cosmicfoods.com

14 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023

HARM’S

IN WAY

Reckless developments put residents in floods’ path

by adam green and bernard brown

Chris deatrick’s girlfriend called him early in the morning on Thursday, September 2, 2021, pleading with him to leave his apartment at the Apex on Venice Island in Manayunk.

Deatrick didn’t think about safety issues when he first moved to the Apex, because on most days the Schuylkill River is slow, muddy and meandering, and the Manayunk Canal on the other side is still and shallow. “It’s a river,” he says. “You don’t think about it.”

In the first days of September 2021, however, the remnants of Hurricane Ida were just passing through Philadelphia, and the Schuylkill was rising rapidly. The day before, Deatrick and other Apex residents had received an email from JRK Property Holdings, the building’s management company, with a rather mild warning. “They just sent an email and told us it might be a good idea to move our cars,” he says.

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 15

The remnants of Hurricane Ida caused dangerous flooding on Venice Island that required emergency boat rescues from luxury residential development Apex Manayunk.

McKayla McLaughlin and Quinte Scott got the same email. In June they and their dog had moved into one of the town houses managed by the same company, just downstream from the apartment building. Two weeks before Ida hit, McLaughlin had given birth to their son. Scott moved their two cars up the island a bit. He says the email did not make clear the need to move cars to higher ground on the mainland. They didn’t realize how vulnerable their new home was to flooding.

Deatrick was reluctant to leave at first. “How could it be as bad as last time?” he recalls asking, alluding to Tropical Storm Isaias, which had flooded the apartments the year before. But his girlfriend kept calling until he had packed a bag and left for her place, nearby but on much higher ground.

The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June through November, and it peaks in early September. Hurricane Ida first made landfall in Louisiana as a dangerous Category 4 hurricane on August 29, 2021, on the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina’s catastrophic landfall 16 years prior. It continued its journey northeastward, eventually joining forces with another low-pressure system moving through the Ohio Valley and crippling parts of the Mid-Atlantic and New England with heavy rain and tornadoes. Over a foot of rain fell in under 12 hours in some parts of the Schuylkill watershed, and several river monitoring stations in and around Philadelphia recorded their highest ever measurements.

Apex residents reported that, aside from the message to move cars, building management issued no additional warnings as the Schuylkill rose. Unsuspecting residents went to sleep that Wednesday night with no inkling that they’d be trapped by the following morning.

Wesley Cherry, another former resident of the Apex, says that he could see the water rising by the minute on the night of September 1, quickly filling the parking garage and East Flat Rock Road before getting into and eventually fully submerging the complex’s first floor.

In the early hours of the morning, the residents woke up, either from car alarms, panicked phone calls from loved ones or a knock at their door from the fire department. Cherry describes looking out the window at submerged, short-circuiting cars, lights flashing and windshield wip-

ers churning as if they were being operated by ghosts.

Several people who could not get to the emergency exit were rescued by boat, as was the case after Isaias in 2020, after a heavy rainfall in May 2014 and after Tropical Storm Nicole in September 2010.

Scott said water had started seeping into the first floor by around 10 a.m. Three hours

later the water had reached the second floor. “We got rescued after the fourth hour. Water was still pouring in, up to our knees on the second floor,” Scott says. The family and their dog were rescued through a window on their second floor. “The baby was two weeks old … I had to hand my baby out through the second floor window. McKayla had had a C-section. This was a sensitive time.”

16 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023

Sooner or later somebody is going to die down there.”

stephen miller, swift water rescue expert

PREVIOUS SPREAD: MATT ROURKE/AP; FROM TOP: JAKE HEENEKE; KEVIN SMITH

The apex’s power went out in the middle of the night, and it didn’t come back on for over two weeks. Management provided no guidance or assistance for temporary housing. Once the power returned, management emailed residents to let them know that they could come back, but residents discovered a host of issues. Deatrick found that his apartment, along with around 15 others, had been broken into. No one had received any prior notice of the robberies, and Deatrick had no way to fully close or lock his door until the busted deadbolt was fixed.

The gas in the building wasn’t working either. When Deatrick reached out to management to complain about the break-ins and the non-functional gas, he was basically told that he’d returned to a disaster zone and shouldn’t have expected things to be back to normal after just a couple weeks.

At McLaughlin and Scott’s town house, the floodwater ruined everything that they had on the first floor. “We lost almost everything in this flood. All my work stuff,” says McLaughlin, who is an esthetician. “We hadn’t unpacked completely.”

They were able to salvage some clothes

but lost furniture, appliances, sneakers and much of their clothing. The floodwater also destroyed gifts from their recent baby shower. “Everything for the baby got ruined,” Scott says.

They also lost their two cars. After the flood a towing company notified them that it had their two cars and would only return them for $6,000. Figuring the cars were ruined by the floodwater, they chose not to pay to recover them.

Scott and McLaughlin reported that the building management offered no help in finding temporary housing immediately after the flood. Rather than stay at a local high school that had been converted into an emergency shelter, they decided to pay out of pocket for a hotel. “I have a newborn,” Scott says. “I’m not sleeping in a gymnasium.” He says ultimately the couple spent about $6,000 on the hotel and a rental car as they sorted out their next steps.

Manayunk is one of the most flood-prone neighborhoods in Philadelphia, and that flooding has been exacerbated by both climate change and local and upstream development.

Venice Island sits between the Schuylkill River and the Manayunk Canal, and residential development of the island was long prohibited due to its positioning in the floodway of the Schuylkill.

“No one should sleep in a floodway,” says Dr. Sally Willig, a geologist who was involved in the opposition to the initial residential development on Venice Island over 20 years ago. Willig is one of the experts who testified on behalf of the Manayunk Neighborhood Council and the Friends of the Manayunk Canal in the series of zoning cases and appeals. The floodway refers to the part of the flood zone with the deepest and fastest moving water. Experts feared that residents would have to rely on swift water rescue teams to transport them to the mainland in a severe flood. Pairing this with people’s inclination to shelter in place during a disaster can have catastrophic consequences.

“Sooner or later somebody is going to die down there,” swift water rescue expert Stephen Miller said in the initial zoning case. Miller was one of several experts who also raised grave concerns about emergency management and evacuation plans for the island. Nonetheless, development proposals

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 17

FROM TOP: KEVIN SMITH; CHRIS DEATRICK

Clockwise from top left: Living spaces were inundated by floodwaters when Ida passed through; floodwaters fully submerged the first floor of the Apex; the management company sent an email advising residents to move their cars—the garage was soon submerged; a SEPTA bus during a 2014 flood.

were ultimately allowed to move forward after a variance allowing construction in the floodway was granted by the Philadelphia Zoning Board of Adjustment (ZBA) in 1999 with support from then-Councilmember Michael Nutter. A lawsuit from the Manayunk Neighborhood Council to contest that variance went all the way to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, which ruled against the neighborhood group. In 2008 developers submitted data to convince FEMA to reclassify the island as a flood zone rather than a floodway, facilitating construction.

Apex Manayunk, then named Venice Lofts, was one of those first two developments on Venice Island at the site of the old Namico soap factory at 4601 East Flat Rock Road. The irony of one of the most floodprone apartment buildings in the city being named Apex is hard to ignore, and Kevin Smith, the president of the Manayunk Neighborhood Council, suspects that the name change was an effort to avoid the negative publicity associated with the old name. According to Smith, information from zoning hearings and flooding photos on the council’s website were at one point the second result that appeared in a Google search for “Venice Lofts.”

Geoff Goll, the president of Princeton Hydro, a Princeton-based engineering and design firm, imagined these scenarios when conducting hydrologic and hydraulic analyses of the island in 1999 on behalf of those opposing the development. The research predicted that floodwaters on Venice Island would rise extremely quickly, trapping residents on the island with little advance notice and potentially rendering swift water rescues unsafe in severe floods.

In Princeton Hydro’s analysis, they warned that Venice Island could be subject to currents over five miles per hour and flood waters 10 feet or higher in a severe flood, and that the river could rise to flood stage on Venice Island in the course of just a few hours, putting residents at extreme risk.

During Hurricane Floyd in September 1999, Venice Island was already underwater by the time the first official flood warning was issued by the National Weather Service.

Residential development plans on Ven-

ice Island were well underway when Floyd passed over the Philadelphia region, and the devastating flooding provided fleeting hope for Smith and the neighborhood council that those plans might be squashed or reconsidered. Instead, the recent reminder of flood risks to the island and its prospective residents were ignored just three months later when the ZBA allowed development to move forward.

Flooding on Venice Island is nothing new, with 21 severe floods reported since 1821, or about one flood every nine and a half years.

Princeton Hydro’s analysis suggests that flooding on Venice Island would be expected to recur about once every seven years. In different terms, there is about a 15% chance of a flood each year. Their report states: “In light of both Philadelphia and FEMA’s extensive regulatory efforts to protect people and property from flooding from even a 100-year flood (which has on average only

18 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023 PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

We lost almost everything in this flood.”

— mckayla mclaughlin, former Venice Island resident

McKayla McLaughlin, Quinte Scott and their son play in their new South Philly neighborhood.

a 1 percent chance of occurring each year), construction of residential developments that would face a 15 times greater risk of flooding must be considered contrary to sound floodplain management and public safety principles.”

Dranoff Properties is the development company that received the initial permit for what is now the Apex, but Smith explains that the developers generally don’t stick around for long. Their primary goal is to build and then sell the complex, and any flood precautions mentioned in the initial zoning case fall to future owners and property managers to implement.

When developers appealed the 2001 Courts of Common Pleas reversal of the ZBA ruling, they proposed several precautionary measures to mitigate impacts of housing people in a floodway, including “locat[ing] all apartment units 14 feet above the 100-year flood level, erect[ing] additions on columns constructed to resist lateral forces from flood waters, hav[ing] no first floor apartments in any building, erect[ing] a pedestrian footbridge at the second story level of the residential complex which would connect the apartment complex to the mainland and would only be used to evacuate residents in case of emergency, install[ing] an emergency alarm and speaker system, and enclos[ing] a copy of the emergency evacuation plan with each resident’s lease.”

“Our building has like half of one of those things,” said Deatrick, who recently left the building to live with his girlfriend. It’s true that there are no apartment units on the first floor of the building, which is now mostly rebuilt. However, most of the town houses at the Apex, including the one from which McLaughlin and Scott’s family had to be rescued, do include the ground floor and have no access to an emergency exit.

There is an emergency exit onto the Leverington Avenue Bridge from the second floor of the apartments that were added to the old Namico site in the early 2000s, and apartment residents used this exit to evacuate on the night of the flood. According to former resident Jake Heeneke, however, the exit was deadbolted shut and had to be cut open on the night of the flood. Heeneke had also identified another deadbolted emergency exit earlier in the day, but he says that when he asked the front desk to unlock it or cut it open in preparation for the storm,

they demurred. Residents report that there is apparently no emergency alarm and speaker system, and no emergency evacuation plan included in anyone’s lease.

McLaughlin and Scott said they did not receive information on flood preparedness when they rented their town house, and they did not get flood insurance on top of their basic renters insurance, which has not reimbursed them for their losses.

A representative from JRK management did not reply to Grid’s request for information about how the property managers prepare residents for flooding.

Residents report challenges dealing with Apex management after the floods.

“After the flood happened they went through four or five different managers. When they were hired they didn’t know what was going on,” Scott says.

Moath Elhady, another Apex resident, was promised a renovated unit when he moved back in, but discovered when he arrived that they had not followed through. He persisted and was ultimately moved to the next available renovated unit, and JRK allowed him to leave soon after Ida without penalties after they mistakenly switched his lease to month-to-month.

Other residents weren’t so lucky: JRK offered to charge Heeneke $10,000 as a buyout to break his lease, even though JRK had violated their own terms on several occasions. Those still living in the Apex in the months after the flood became more and more disillusioned with the place as seemingly simple repairs to things like door locks, stairwell lights and elevators went unaddressed. Apartment tours continued, and Heeneke and Elhady began interrupting those tours to ask probing questions about whether anything about the recent and other past floods had been disclosed. JRK threatened Heeneke with legal action for one of these interruptions. One tour guide explained that they were not allowed to mention flooding on tours, and many tour guides quit after just a week or two.

Heeneke, who had encountered the locked emergency exit doors during the flood, describes a series of interactions with management in which they refused to address fire safety and code violations and took several months to address an issue with damaged carpeting in his apartment. Heeneke says that

one staff member told him that the first thing she did each morning was delete any emails she’d received the day prior.

After the flood, residents scattered to nearby relatives, hotels and Airbnbs. They received no reimbursement for their temporary housing, and they reported few updates from management about next steps. They slowly returned to destruction, with ABC Action News and NBC Philadelphia reporting that one Apex town house resident, Natasha Martinez, was given five days’ notice to gather her belongings from her apartment where the floor and walls had been removed.

As many residents tried to find the easiest and cheapest way to leave, JRK slowly rebuilt. Residents report that staff members left and were replaced, the locks were eventually repaired and the gym reopened.

McLaughlin, Scott and their family settled in a house in South Philadelphia he inherited from his grandfather. “It needs a lot of work done,” he says. He also says they would like to pursue legal action against JRK, but they have not been able to find an attorney to take their case. “We are still looking for lawyers. I don’t want to let it go because I lost so much,” Scott says.

Storms capable of causing flooding are growing more frequent due to global warming. Warmer air holds more energy and moisture, which can be released via intense storms. In June 2023, the First Street Foundation released a report updating the precipitation model used to estimate how much rain will fall during storms. The currently used model is based on historic rain totals and does not consider the recent and future effects of climate change. The updated model found that what had been considered a 100-year storm is likely to take place every 29 years. In other words, a storm that previously had been estimated to have a 1% chance of happening every year actually has a 3.4% chance of happening every year. –

As other cities move away from development in floodplains, Philadelphia marches forward. New developments are planned for Venice Island at the old PaperWorks Industries mill site at 5000 East Flat Rock Road and at a site owned by Rock Urban Management at 4436–44 Main Street, a short distance south.

At a November 12, 2022 Civic Design

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 19

Review meeting of the City Planning Commission, Jerry K. Roller, founding principal of Rock’s architect firm JKRP Architects, presented the plans for 4436–44 Main Street. These include a bridge to connect the second floor of the building across the Manayunk Canal to the mainland. He said that that portion of Main Street did not flood during Ida, and that City floodplain management officials agree with relying on the bridge for evacuation.

That escape route sits in what is commonly referred to as FEMA’s 500-year floodplain (in any given year it has a one out of 500 chance of flooding), and members of the commission recommended connecting the building to the Manayunk Bridge trail that passes above the site and is reliably drier. Roller said he would look into connecting to that bridge.

“[It is] definitely worth looking into just because of the 500-year floodplain issue and even the 100-year floodplain issue,” said commission member Michael Johns. “We don’t know with climate change what’s going to happen particularly on these rivers.” The commission can only offer suggestions and has no power to force developers to change their plans. As of print date, the development was still going through the design review process with the Philadelphia Historical Commission.

Josh Lippert, former floodplain manager for the City of Philadelphia, says there is little appetite for change. He explains that there are multiple factors preventing meaningful change in how the City handles development in the floodplain. Floodplain maps are outdated and, when they have been updated, it has been at the behest of

developers. Proposed safety measures represent the bare minimum and are often not enforced. Most stakeholders either don’t understand or don’t care about good floodplain management.

Lippert argues that, in various projects across the city, disclosures from developers who construct these buildings to the companies that manage them through actual flood events are insufficient, as are the disclosures from building managers to renters. Kevin Smith, of the neighborhood council, refers to the planned site at 4436–44 Main Street as “more of the same,” and he mentions that while there are still several steps in the process before construction can begin, if the past is any indication of the future, it is unlikely that risky development on Venice Island will stop or that this or future buildings will be safely built or competently managed. And as climate change produces storms of increasing frequency and intensity, residents of the new building, along with those of the Apex, will face flooding again.

Grid reached out to the Philadelphia Fire Department to learn more about how past flooding at a site factors into their review of proposed construction. A fire department representative directed Grid to the City’s Department of Licenses and Inspections (L&I). A City representative replied that the permits required for building in a floodplain do

involve extra requirements on top of what is usually required for building outside of a floodplain: “The requirements are largely derived from federal FEMA regulations.” L&I inspects buildings during construction, but later code violations (such as the locked exits encountered by Heeneke) should be reported to Philly311 so that L&I can respond with an inspection. As for existing buildings like the Apex, “the City does not have a process in place that requires permanent evacuation of existing, occupied properties due to propensity to flood.”

With L&I not equipped to react, the onus for protecting residents in flood-prone areas (present or future) largely falls on elected officials. They have repeatedly failed in this task. In 1999 Councilmember Nutter pushed through the rezoning that permitted construction of the Venice Lofts. In 2018 the City Planning Commission voted to reject building additional town houses on another parcel of land on the island because they would put residents’ lives at risk during a flood. As an advisory body, however, they had no power to back up their recommendation. In spite of the experts’ safety concerns, City Council unanimously voted to change zoning to permit their construction.

Curtis Jones, the councilmember whose district includes the island, did not respond to Grid’s requests for comment. ◆

20 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023

I had to hand my baby out through the second floor window.”

— quinte scott, former Venice Island resident

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 21

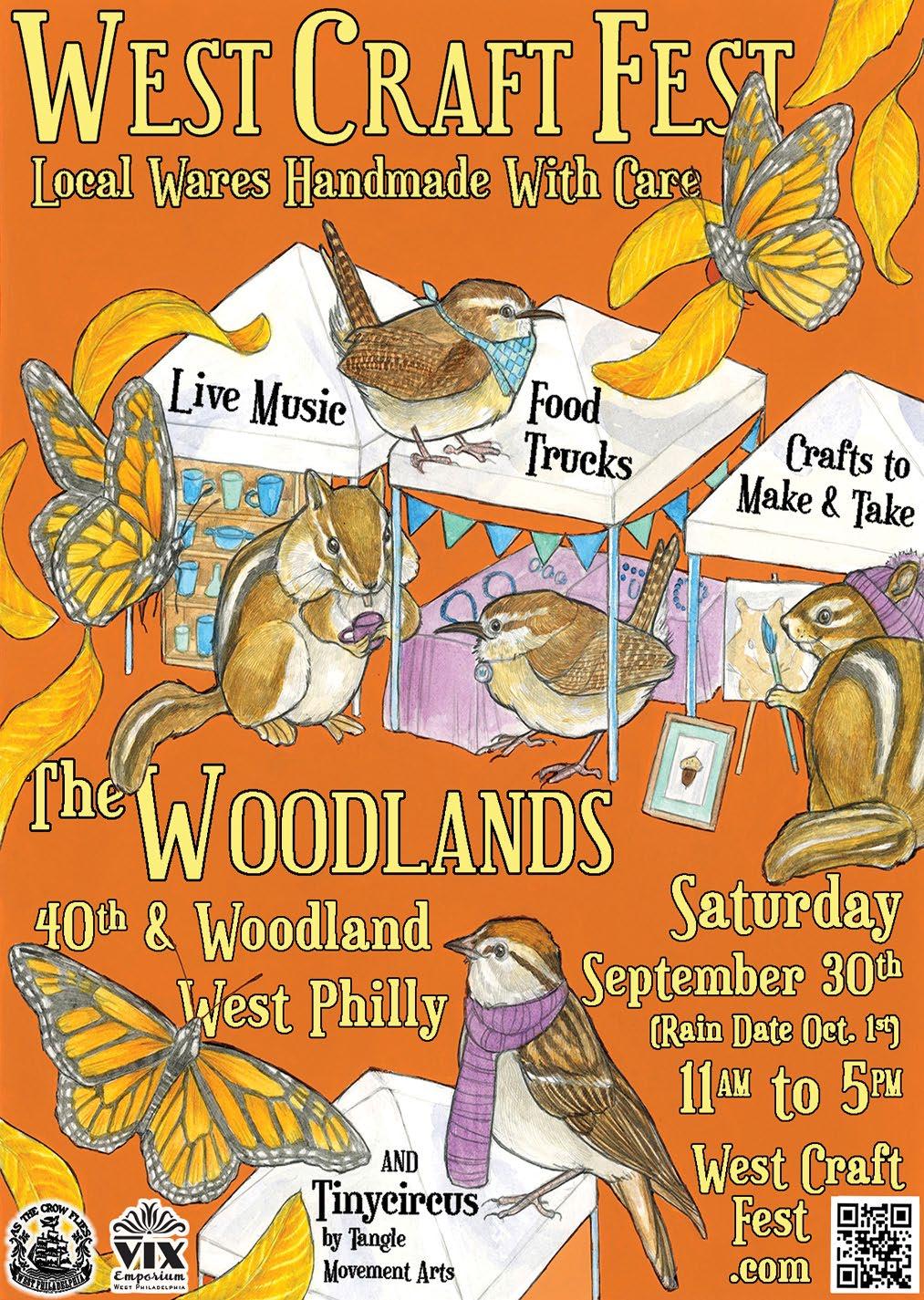

EDUCATION ISSUE 20 23

Welcome back to school! Beloved by parents and reviled by students, the month of September is when students find themselves back in classrooms after the long summer vacation. We figured it would be a good time to turn our attention back to education.

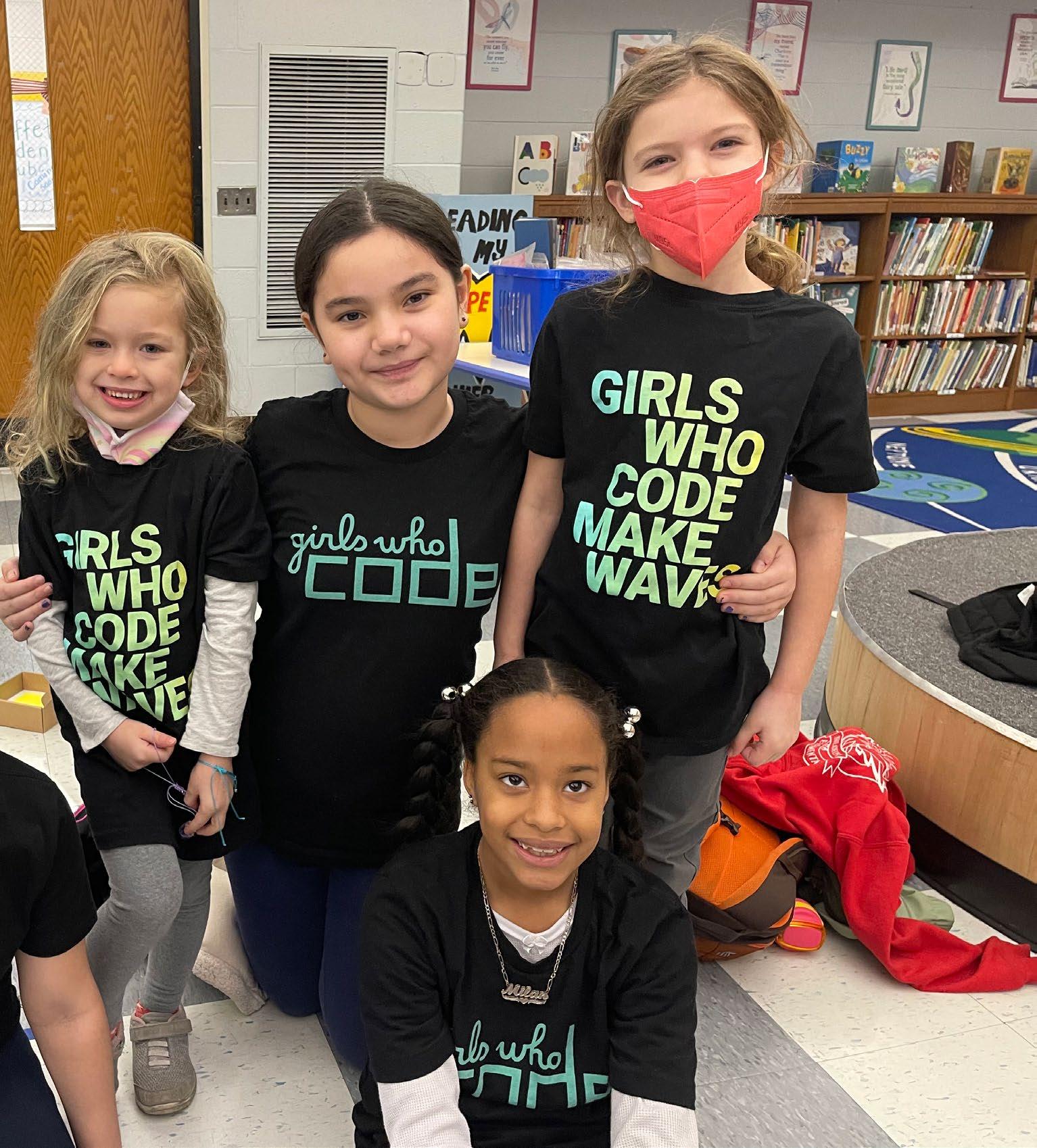

In this section we look at examples of how our schools are preparing students to be creative, environmentally-conscious problem solvers, whether as elementary students or as high schoolers preparing for careers.

Where our students learn also matters, and in Philadelphia that is often in ancient buildings built with materials we would never use today, including asbestos insulation and ceiling tiles. We turn our attention to efforts to ensure the buildings in which students learn are safe for them as well as for the staff and teachers.

Of course not all education happens in school. Environmental centers carry on the work, and plenty of after-school and summer programs keep our kids engaged and learning through the year. Perhaps most importantly, parents and other guardians teach by word and example from cradle to adulthood.

And as anyone who chooses to spend their time reading environmental magazines knows, we can keep learning well after we stop going to school. We can learn by reading articles, watching documentaries, listening to podcasts and by walking with guides and griots.

No matter where you are in your lifelong path of education, we hope you pick up something new in this issue. It’s never too late to learn.

22 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023 education 2023

Not only are they learning more, but they’re learning useful skills.”

MICHAEL DEMENO,

Moffet Digital Literacy

Teacher

•

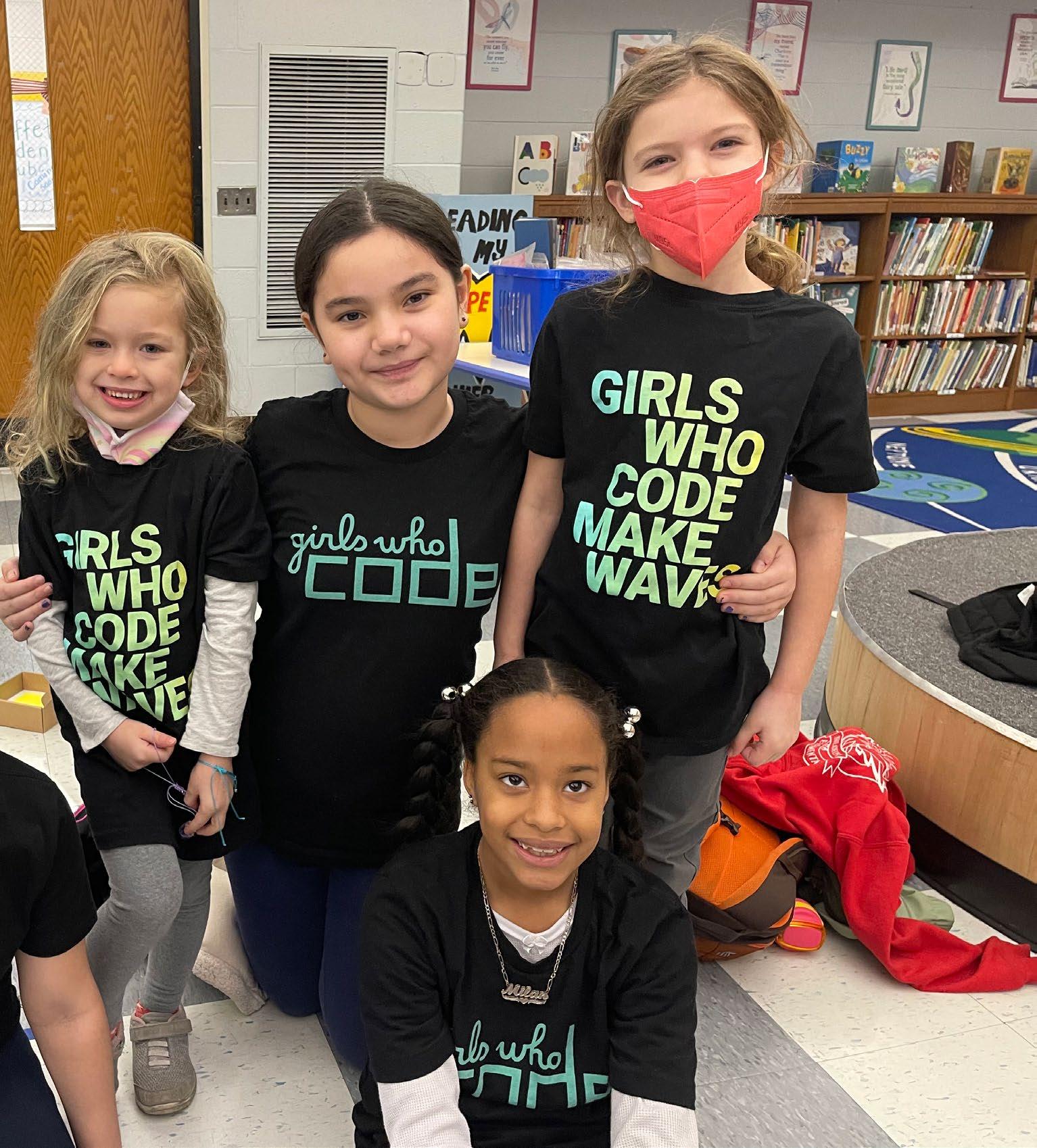

From left to right: Houda Ouldali, Frankie Zor, Ena Hannigan, Milan Tucker and Isabel Zor learn computer programming at the Moffet Elementary makerspace.

PUTTING IT TOGETHER

Elementary school makerspace helps students develop 21st-century skills

story by kiersten adams

Ena hannigan wants to be at school — a fact that her mom, Erike De Veyra, is overjoyed about. Ena, who will enter the fourth grade at John Moffet Elementary School in September, is already an active student in her school. She’s a member of one of Moffet’s STEM clubs, Girls Who Code, and is interested in joining the podcast club in the upcoming year. Ena enjoys learning to code and even playing with robotics, two things that might not be possible if not for Moffet’s innovative staff and beloved makerspace.

Run by Moffet’s digital literacy teacher, Michael DeMeno, the makerspace has provided nearly 300 students the opportunity to explore extracurricular learning in a uniquely creative way. DeMeno considers the space a necessity for the educational growth of his students. “It blends all subjects together, [and] our kids are learning better,” says DeMeno.

Unsure what a makerspace is? Consider it a multi-use station for people with common interests to collaborate on projects and share ideas, ordinarily operated for STEM

purposes. Moffet, located in East Kensington, opened its space in 2019 after DeMeno suggested it to the Friends of Moffet family school organization. After receiving their first grant to start the makerspace, DeMeno, fellow staff members and students started imagining uses beyond its typical functions. The space became the hub for clubs including Girls Who Code, the podcasting club, nature STEM, music STEM and the makerspace club.

In Moffet’s makerspace, students are able to participate in activities most public schools in the area can’t provide.

“Not only are they learning more, but they’re learning useful skills. They’re getting social skills and learning to work together in ways, traditionally, they wouldn’t be able to,” DeMeno says.

In a school district working to remedy a growing list of major concerns, Moffet is an example of how a small act can affect learning and keep students and their parents excited about school.

For De Veyra, choosing a school for her daughter was a daunting responsibility. Living close to North American Street, a hub for designers and makers, De Veyra was looking for schools that implement creativity into their curriculum. Once she found Moffet and learned of the proposed makerspace, her worries all but disappeared.

“We had been thinking about taking [Ena] to Moffet before she was even three years old,” says De Veyra. “Not very many schools around here, even the elementary school in Fishtown, necessarily have a makerspace, and coming from a design background, we were super excited that this was going to be accessible to the kids here.” De Veyra says she plans to send her youngest to Moffet for kindergarten in the fall.

While both Ena and her mom look forward to a new school year and new opportunities in the makerspace, teachers like DeMeno are prepping for the 2023–2024 year by thinking of new, green ways to engage their students.

“Half the things I do are with cardboard, paper and things that I just pulled from the recycling bins at school,” DeMeno says. “It doesn’t have to be a very expensive makerspace at the start, but it’s still introducing kids to the engineering design process, giving them 21st-century skills and letting them learn in a nontraditional way and still be happy.” ◆

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 23

MICHAEL DEMENO

COLLABORATIVE ECOSYSTEM

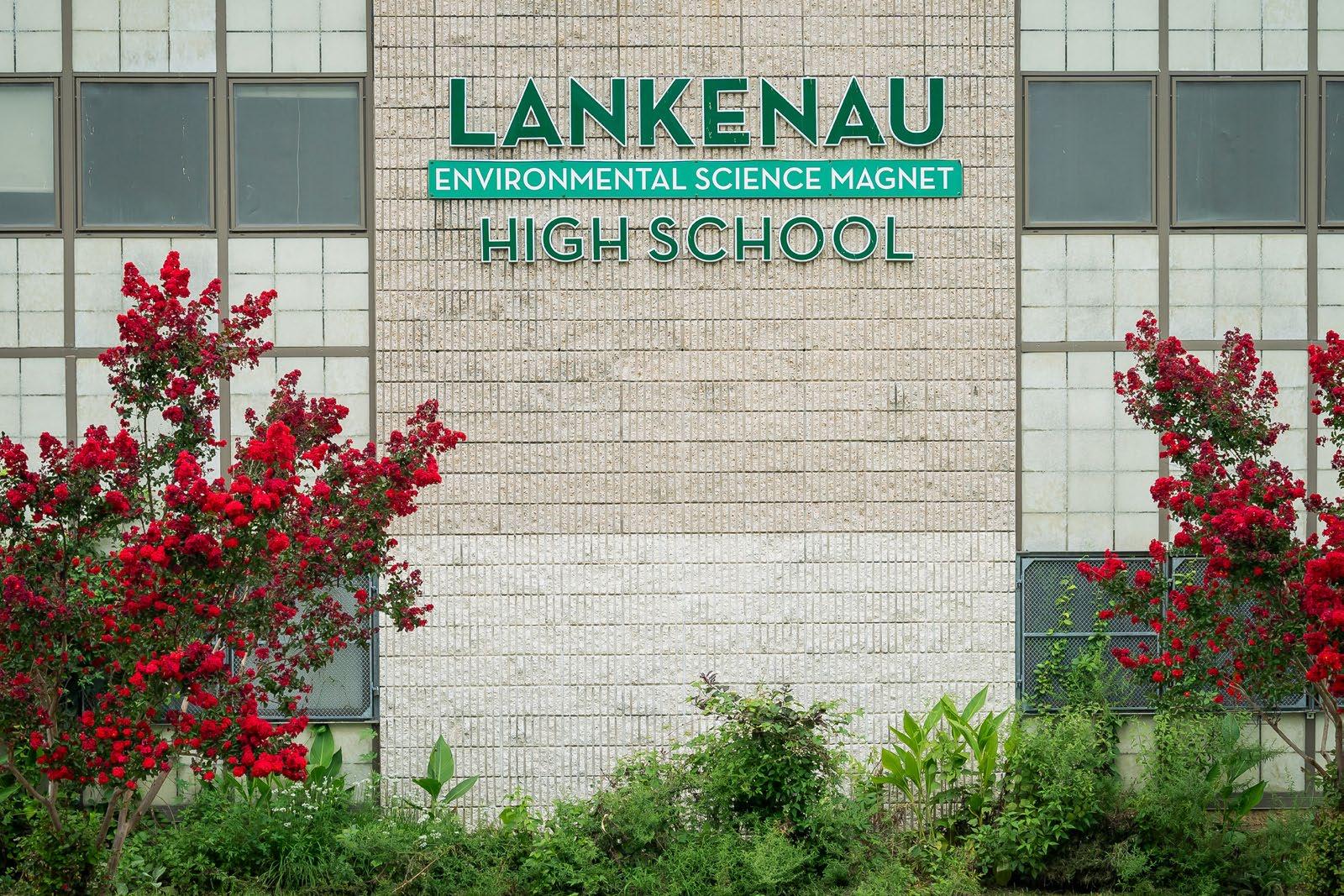

Roxborough magnet school gives students the opportunity to be environmental problem solvers

story by bernard brown

Michael cano hadn’t thought much about environmental issues or agriculture before attending Lankenau, the School District of Philadelphia’s environmental sciences magnet high school. “I found out about [Lankenau] because of family that went there before me and told me of a positive experience they had.” By his junior year he found himself in Washington, D.C., collaborating with a team of students from Indonesia to solve the problem of plastic waste in school lunches.

“Plastic in Lankenau is used in many ways, from the trays that are used for the food all the way to the utensils like spoons, forks and even sporks,” says Cano, now a senior. All that single-use plastic is an obvious target for student environmentalists. At the Green Actions for the Future competition, Cano joined a team of Philly students who were paired up with the students from Indonesia. The students were tasked with devising solutions to all the plastic that ends up in the trash can after lunch. The Indonesian students developed plant-based materials to contain their lunches, while the Philly students petitioned the school district to reduce plastic.

Lankenau was established as an environmental sciences magnet high school in 2005, although the building has been used by the district as a school since the late 1970s. Visitors to Lankenau might not think they are still in Philadelphia. The road on which the school sits looks more like a country lane than a city street. Fields and forest surround the school.

“The campus provides a unique perspective to study agroecology and ecology. It provides the landmass that students need to investigate the natural world,” says principal Jessica McAtamney. Now in her third school year at Lankenau, McAtamney has been working to expand the career development opportunities for students.

Lankenau sits next to the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education, where students have long taken part in internships and other activities, such as planting trees, removing invasive plants and maintaining trails. In the past two years the school has been adding options to the internship program to take students farther afield to organi-

24 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023 education 2023 PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

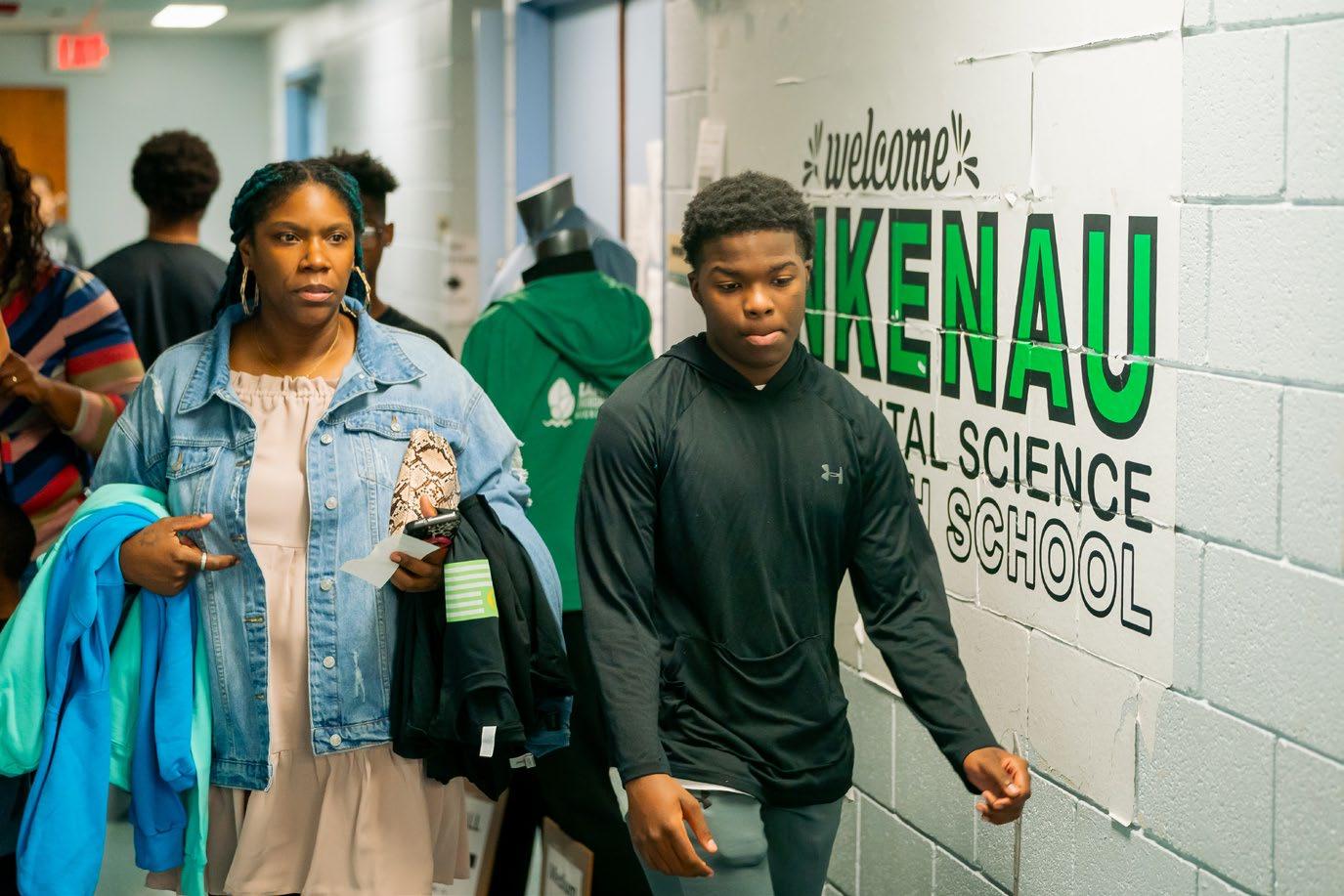

Left to right: Yusef Dumpson, Kristian Subhar, Alix Morris and Josephine Schirling are Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources (AFNR) seniors at Lankenau Environmental Science Magnet High School.

zations such as Morris Arboretum, the school district’s Office of Sustainability and Friends of the Wissahickon, where Cano is placed. “I will be starting an internship with Friends of the Wissahickon, about contributing to the Wissahickon Valley Park,” Cano says.

Josephine Schirling, who spends an hour and a half taking two SEPTA buses to get to the school from their home in Brewerytown, landed two internships in the 2022–2023 school year: one at the Schuylkill Center and the other at a biodesign training organization called Aula Future, based at the University City Science Center. There Schirling took part in a design challenge. “Basically me and two other of my peers from Lankenau, we had to come up with a project and we had to present that project in New York to a bunch of college students and judges,” they say. “We chose a system of manufacturing textiles from invasive species. We used garlic mustard, Japanese knotweed and phragmites, both fiber and

for dye, trying to be as circular as possible.”

Both Schirling and Cano have taken part in the high school level of Minorities in Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Related Sciences (MANRRS). “When I first attended, l had no idea, no knowledge about agriculture. But over the years at Lankenau I have learned more and more about agriculture, not just about farming,” Cano says.

Jonathan Hoffmeier, a math teacher at Lankenau who serves as athletic director in addition to the MANRRS sponsor, sees the program as a bridge to university programs in agriculture and natural resources via college-level MANRRS chapters. “With high school sports, there’s a pathway if you’re an athlete to go to college and get that funded. Junior MANRRS is a nice pathway to the college MANRRS partners,” Hoffmeier says. Lankenau students take part in Junior MANRRS along with students from The U School and W.B. Saul High School. “We took our kids this fall to the regional conference,

which had the college chapters and our kids there,” he says. “They got to see the college students go through their networking and companies hiring kids for agricultural fields … They collaborated with kids from Bali. They’re seeing a lot of different things kids normally aren’t exposed to.” This school year will be Lankenau’s second in MANRRS.

Cano, who aspires to study computer science at Penn State University after graduation, says that his MANRRS team’s attempt to make the cafeteria more sustainable ran into a wall of bureaucratic inertia. “The district did not respond, but it was good doing the project overall,” he says.

Even though the school can take a while to reach by bus, the students and staff say it is worth it. “I think my big message is don’t let the commuting time deter you,” Schirling says. “It’s a great community. Everyone knows each other. Everyone cares for you and advocates for you. I’ve gotten to do a lot of cool things.” ◆

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 25

When I first attended, l had no idea, no knowledge about agriculture.”

MICHAEL CANO, Lankenau student

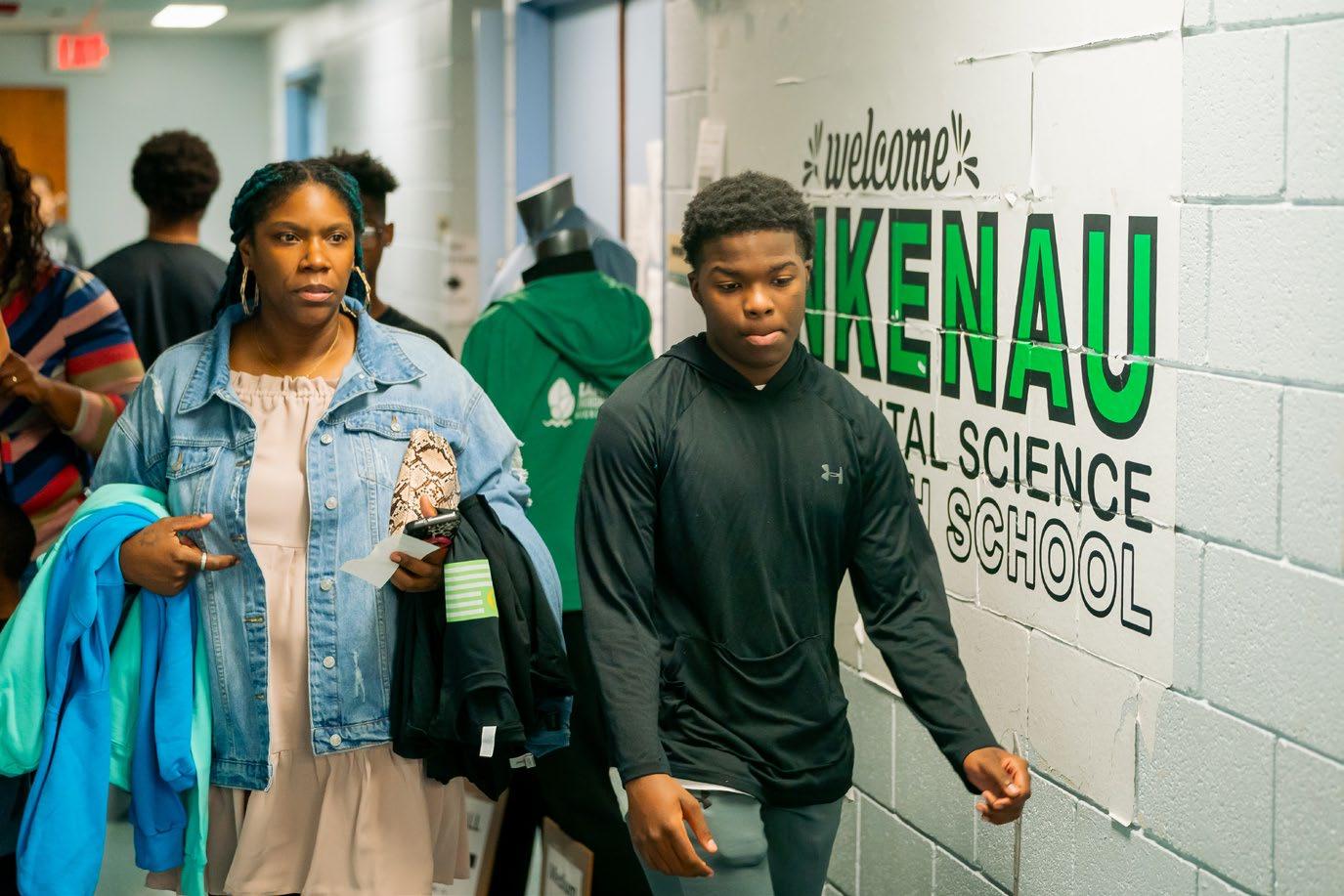

• Families tour the halls of Lankenau at an open house.

NATURE AS TEACHER

Wissahickon Environmental Center inspires children, adults and prospective environmental scientists

story by dawn kane

story by dawn kane

On a damp morning in July, children spill around the corner of the Tree House and flit through the woodland garden exploring the grounds surrounding the Wissahickon Environmental Center (WEC) in the northern end of Wissahickon Valley Park.

“Will we find bears?” one young girl asks.

Jeneen Helms, an assistant from the West Mill Creek Recreation Center, assures her that they will not.

A young boy runs up to any adult who will listen. “We found a frog!” he yells excitedly.

Sean Bradley, a seasonal instructor, casts an experienced eye over the garden area

where the boy points and offers a gentle correction. “Where was the toad?” he asks.

The youngster leads Bradley to a grassy thicket. “The frog was over here!”

The children exploring the natural areas surrounding the WEC are part of a program sponsored by Philadelphia Parks & Recreation (PPR). Throughout the summer season, recreation centers throughout the city bring children, chaperones, youth workers and camp counselors to the center, known locally as the Tree House. From 1890 to 1981 a large circular hole in the back porch roof accommodated a towering sycamore tree, according to the Friends of the Wissahickon website

According to Tony Croasdale, who manages the WEC program, the group of 10 children between six and 12 years old was smaller than usual. Groups typically number between 20 and 60, he says. Croasdale, an environmental education program specialist, sees himself as a naturalist.

Croasdale says the work isn’t solely about play. He wants to share the benefits and wonders of nature with as many Philadelphians as possible, especially with people of color and those who don’t have easy access to green spaces. He’s especially happy when the groups come with adults.

“They all get exposed to [nature]. Everybody gets this information. They’re all a unit [even if] they’re not engaged in the activity. They’re hearing it and they’re in there seeing it. To me, it’s really valuable to get to the staff. And … when they come with chaperones, you know, that’s a great thing,” he says. “It’s … the most effective outreach,” Croasdale says. “It’s people who aren’t choosing to come here [on their own].”

In addition to Croasdale, the WEC team

26 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023 education 2023

PHOTOGRAPH BY TROY BYNUM

Rec center summer campers try out binoculars for the first time.

includes fellow educator Susan Haidor, two PPR seasonal staff, a groundskeeper and volunteer trail ambassadors from the Friends of the Wissahickon. When a large group visits for a trail walk, it’s helpful to have knowledgeable people on hand, Croasdale says.

“You never know when you’re going to spot that toad, or when you’re going to see something in bloom,” Croasdale says. It’s all about showing them things they might have missed and telling them the story behind it, and there’s generally an intergenerational benefit, he says.

The visitors aren’t the only people learning at the center. Croasdale says he is proud of the young seasonal instructors from the

they’re indicator species that help scientists evaluate the health of a creek.

In addition to seasonal staff, the WEC provides work experiences for disabled youth through the Youth Advocacy Program (YAP). Funded through the Pennsylvania Office of Vocational Rehabilitation, YAP provides workforce training for youth and young adults with a wide range of disabilities, says Chanel Summers, program manager.

Collin Kuchar and Simon Koval-Bauer, YAP workers, were busy clearing logs from the trails. Koval-Bauer says he likes feeding the box turtles and was pleased to have just received his first paycheck.

“Last week we made sugar water for the hummingbirds,” says Kuchar. “I like the peace and quiet.”

In addition to the outdoor adventures, visitors find lessons in natural science inside the center. Aquatic turtles cruise a giant tank, and taxidermied predatory birds stare down from the walls. “The kids get excited to see things under the microscopes,” Croasdale says. “They realize there’s a whole diversity of life they [normally] don’t see.”

TOP MIND of

local businesses ready to serve

BOOK STORE

Books & Stuff

ENCOURAGING … Literacy, Knowledge, Creativity and Inquisitivity! at booksandstuff.info

COMPOSTING Back to Earth Compost Crew

PPR workforce development program. They bring an interest in environmental sciences, and the experience they get at WEC enables them to get that next full-time job in the field. Employers “want someone that has done this stuff, has had hard days in the field, in poison ivy … in 90 degrees and humidity and knows what it takes,” he says. “They know … the basic principles of identification of various taxonomic groups — plants, reptiles, amphibians and birds. You name it — insects — they already have a lot of experience.”

Maxine Antinucci, a first-year instructor, found out about the position through a teacher and loves the work. “Oh, it’s super fun. I always liked nature. I wanted to [be an] environmental high school teacher and also a game warden. So, this is a good foot in the door.”

Bradley, who found out about the program from his grandparents, is back for his second year. He likes taking the youth groups down to the creek and teaching them about things like aquatic macroinvertebrates, small organisms that lack a backbone. He explains

Susan Haidor, WEC educator, says that after the summer season, the center gears up for school groups. The WEC received a special grant from the Friends of the Wissahickon through the Let’s Go Outdoors program to reach more K–3 school groups, she says. But before school is back in session, Croasdale anticipates that 30 to 50 recreation center groups will visit.

On the day that the West Mill Creek group visits, a girl sidles up to trip leader Akeem Robinson, shaking her short braids and swatting at herself. After a brief inspection, Robinson, who has been working in his position for three years, tells her, “No bugs on you. You’re fine.”

Bradley and Antinucci pass out binoculars and prepare the group for the possibility of seeing animals — a snake, maybe? — on their walk. “It’s not going to attack you,” Bradley says. “Just don’t touch it … This is their house.” ◆

The WEC is open to the public Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. The building may be locked if staff is on the trails, and weekend hours are limited. Visitors may stroll the grounds. The road leading to the environmental center is accessible by public transit.

Residential curbside compost pick-up, commercial pickup, five collection sites & compost education workshops. Montgomery County & parts of Chester County. First month free trial. backtoearthcompost.com

DEATH DOULA The Death Designer

Compassionate end of life planning, including paperwork, funeral and memorial planning, legacy projects, and collecting passwords in a password manager. Find out more at thedeathdesigner.com

GROCERY Kimberton Whole Foods

A family-owned and operated natural grocery store with seven locations in Southeastern PA, selling local, organic and sustainablygrown food for over thirty years. kimbertonwholefoods.com

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 27

They all get exposed to [nature]. Everybody gets this information.”

TONY CROASDALE, Wissahickon Environmental Center

From to

HAZARD HOPE?

State funding could finally address the menace of asbestos that looms over Philadelphia schools

by kyle bagenstose • photography by gene smirnov

by kyle bagenstose • photography by gene smirnov

28 GRIDPHILLY.COM SEPTEMBER 2023 education 2023

FRANKFORD HIGH SCHOOL

Built in 1910, Frankford High School was abruptly closed in the middle of the spring 2023 semester when asbestos was found where students learn and eat. An entire floor of the building had been closed off for years for the same reason.

SEPTEMBER 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 29

In 2023, a new rash of school closures due to asbestos offered the latest gut punch to the Philadelphia education community. But advocates say changes in Harrisburg and Philly offer the best hope in their lifetimes for something better.

When marybeth reinhold started teaching English at Frankford High School, it marked an exciting return to the classroom. It was 2005, and Reinhold had just finished a seven-year hiatus raising two children at home. She looked forward to getting back into the profession — and back into the pages of “The Kite Runner,” “The Crucible” and other works with her students.

“When I first started, of course you’re just happy to have a job,” Reinhold says.

But ominous foreshadowing would arrive in Reinhold’s first year, when teachers told her about a mysterious fourth floor at Frankford and the dangers that lurked there.

“Nobody was allowed up there. The elevators didn’t even go to the fourth floor,” Reinhold says. “It was filled with asbestos.”

Over time, the menace hanging overhead receded to the back of Reinhold’s mind. Then slowly, more failings of a century-old building drip-dripped back in: weird stuff leaking from the ceiling of a ladies’ room, pipes covered in suspicious substances, rampant mold in a basement classroom.

After 18 years — the time it takes a child to go from cradle to graduation stage — the villain fully emerged from the shadows. During spring break last school year, Reinhold says, a maintenance team found some asbestos behind a third-floor radiator. They closed the building, first for just a few days, then weeks, then the rest of the year.

The future of Frankford and its proud community now remains in doubt, but even scarier is the past. When teachers went back into the high school to collect their belongings, they did so from a staged area declared safe: many weren’t allowed to access the hallways and classrooms they’d worked in for years. Nobody knows who may have been exposed to what, where exposure happened, or for how long.

“We were told it was in a lot of places, but the only specifics we’d gotten was that it was in the ceiling that was over the caf-

eteria,” Reinhold says. “Which is basically what prompted them to close the school, because they can’t have kids eating with asbestos over their heads.”

If this story sounds all too familiar, it’s because it is. Many Philadelphians were introduced to the systemic dangers lurking in their public schools in 2018 by The Philadelphia Inquirer’s “ Toxic City: Sick Schools” investigation, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize after it revealed rampant problems with asbestos, lead, mold and other hazards in numerous buildings.

But those closest to the action have known for much longer. In 1985, Jerry Roseman, director of environmental science and occupational safety and health for the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers (PFT), was first brought onto the job by the union. The environmental scientist and former New Jersey Department of Health inspector began plying his trade in the district’s buildings after a dozen had shut down the previous year due to asbestos, including Martin Luther King High School in Germantown and Abraham Lincoln High School in Mayfair.

“The problems resonate with what’s going on now,” Roseman says, noting that 10 schools closed in 2019 and 2020, and another six, including Frankford, in 2023. “We keep finding asbestos.”

Trying to point a finger at someone accountable for these intractable problems is futile. Shake a stick and you still won’t hit everyone. Staff and students will point at the School District of Philadelphia, the school district will point at politicians in Harrisburg and the politicians tend to point right back. And in the end, of course, it’s everyday citizens who vote to put these decision makers in power in the first place.

But Arthur Steinberg, treasurer of the PFT, president of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) Philadelphia and vice president of the national AFT, sees a chance, right now, to set things right. There is fresh leadership in the school district that seems to be taking the problem more seriously than ever before, he says. Democrats have won control of the State House of Representatives for the first time in 12 years.

A monumental Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania decision adds significant impetus to better fund schools, at the same

time state coffers are running multi-billion dollar surpluses. It all adds up to a chance to finally change the narrative.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get things on the right track,” Steinberg says. “We can’t afford the mismanagement that has occurred in the past, because then we’ll squander it.”

No money, more problems

Most advocates for safer school buildings can agree on one thing: it’s the money.

Matthew Kelly, assistant professor of education at Penn State University, is an education funding policy guru who has served as an expert witness during legislative hearings and court cases on the topic. The exact formula of how schools are funded in Pennsylvania is complicated, but Kelly says the key takeaway is that Pennsylvania’s reliance on local real estate taxes instead of state coffers to fund schools makes it an outlier nationally and results in wide disparities between districts.

“There is a very inequitable distribution of taxable wealth across school districts,” Kelly says. “And the money the state is providing is not sufficient for what districts need.”