Housing justice through free repairs in Grays Ferry p. 16

Scholar explains the roots of environmental racism p. 18

What you can do to improve air quality p. 26

Despite rising costs and implementation setbacks, Philadelphia’s gamble on green stormwater infrastructure continues. Is it time for the Water Department to change course?

■

■

■

JUNE 2024 / ISSUE 181 / GRIDPHILLY.COM TOWARD A SUSTAINABLE PHILADELPHIA

kimbertonwholefoods.com COLLEGEVILLE | DOUGLASSVILLE | DOWNINGTOWN KIMBERTON | MALVERN | OTTSVILLE | WYOMISSING A community market passionate about sustainable agriculture and supporting the next generation of farmers.

wooder.

No matter how you pronounce it, clean water starts with preserved land. Natural Lands has been saving our region’s open space since 1953... 135,000 acres and counting.

But we need your support to keep up the good work. To stand with the land and side with the outside, visit natlands.org/support . land for life. nature for all.

Wawa Preserve Media, PA | 75 acres

Photo by Mae Axelrod

EDITOR’S NOTES by

alex mulcahy

publisher

Alex Mulcahy

managing editor

Bernard Brown

associate editor & distribution

Timothy Mulcahy tim@gridphilly.com

deputy editor

Katherine Rapin

art director

Michael Wohlberg

writers

Kyle Bagenstose

Allison Beck

Bernard Brown

Amber X. Chen

Kristen Harrison

Jenny Roberts

Bryan Satalino

photographers

Chris Baker Evens

Jared Gruenwald

Kristen Harrison

illustrator

Bryan Satalino

published by

Red Flag Media 1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107 215.625.9850

GRIDPHILLY.COM

Doubting Nature

Iused to have a neighbor across our alley who worked for the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD). He was a friendly, likable guy, but there was evidence, like his big SUV, that he wasn’t in lockstep with the street’s green-minded residents. He grew tomatoes and peppers on his deck, like many of us do, but aided by a drip irrigation system he constructed and a container of Miracle-Gro. One day in the alley he showed me a Civil War-era map of our West Philly neighborhood when it was home to the Union’s largest hospital. When I asked him where he found the map, he said he bought it at a gun show.

So I was not surprised when he rolled his eyes dismissively at the mention of Philadelphia’s green stormwater management measures. I just wrote it off as someone stuck in the past, who was more likely to believe that the best plan is to conquer nature rather than work with it.

Grid was already pretty invested in the promise of green stormwater management that “Green City, Clean Waters” articulated. The idea that we can deal with water pollution while beautifying the city, creating more green space, planting more native plants in swales and rain gardens … well, it was incredibly appealing. And that it would cost less than the old-fashioned industrial way made it a true no-brainer.

So enamored with this plan were we that we even put PWD’s then-commissioner Howard Neukrug on the cover in December 2013 [Grid #56], and he gamely wore a superhero’s cape for the photo shoot.

We remained unquestioning until January 2022, when our long-time contributor and now managing editor Bernard Brown interviewed PWD officials and engineers on

the 10th anniversary of Green City, Clean Waters. He returned to the office with the sense that PWD officials were dodging his questions about the real-world effects of the new systems on waterways, as well as their expected performance as global warming brings more frequent and more intense precipitation.

It was one of those moments that should have prompted us to dig deeper, but we dismissed our doubts. Green City, Clean Waters was a smashing success; surely we were misunderstanding something.

If we had pursued our journalistic instincts, we might have discovered the dissenting voices at the EPA and the District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority. We might have found out that our wastewater treatment facilities were operating on long-expired federal permits. We might have turned up sources within our water department questioning the efficacy of the program.

It is easy to say that this is all only clear in hindsight, but there were skeptics — like my neighbor — from the very beginning. Perhaps they were too easily written off as oldguard traditionalists who couldn’t accept a different, greener way of managing water, but we should have listened to them.

When innovative new plans claim to solve our problems, it’s our job to entertain the possibility that the boosters are wrong, even when we want them to be right.

alex mulcahy , Editor-in-Chief 2 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 3 CEMETERIES · FUNERAL HOME · ARBORETUM CHOOSE GREEN Explore your greener options by contacting our care team today. 3 Green Burial Sections Eco-friendly Funerals & Products Pet Aquamation laurelhillphl.com Bala Cynwyd | Philadelphia 610.668.9900 www.gtms.org info@gtms.org American Montessori Society Accredited Tuition Assistance Available School Day and All Day Montessori Toddler through Third Grade Montessori & Me Parent/Infant classes 55 N. 22nd Street, Center City, Philadelphia It all begins here. Limited 3-year- old availablespacesfor September 2024! NeedsYou! Support local journalism by subscribing or donating Pay what you can on PayPal or in our store STORE.GRIDPHILLY.COM PAYPAL

Round and Round

Start-up launches pilot program to form an online circular toy economy by

jenny roberts

Nic esposito wants to reimagine the retail industry; he believes that people, profits and the planet would benefit from leaving business as usual behind. That’s where Circa Systems comes in.

Esposito founded the Philadelphia-based company in 2023 to create a more sustainable, local retail model, allowing paying members to purchase and swap mostly used products via online stores.

“Instead of making 10,000 things and hoping that you sell 10,000 of them, what if you were able to take 1,000 items and sell them 10,000 times?” says Esposito, Circa’s chief executive officer.

“You’re reducing emissions, you’re reducing extraction, you’re reducing waste and then you’re increasing profits,” he adds. “I think it’s a win-win for everybody.”

In May, Circa launched a six-month pilot for its first platform, Unless Kids. A cohort of 50 users are currently buying and trading discounted toys through unlesskids.com, providing feedback b efore the platform

opens to a larger audience.

The pilot uses a model rooted in the circular economy, in which products stay in circulation as long as possible through reuse or repair. In the purest form of a circular economy, when items are no longer usable, they are broken down into their component parts to be remade into new items. Greater efficiency and conservation of resources allows for lower product pricing; it’s the model future Circa platforms will also use.

“We can continue to have an economic system that works and is probably more just,” says co-founder and chief product officer Samantha Wittchen, noting that the circular economy isn’t reliant on exploiting communities through the extraction process and doesn’t cause environmental justice issues through waste disposal.

For a monthly fee of about $5, Unless Kids members can purchase new and used toys — which are discounted based on their wear and tear — through the online store. Users can choose to keep toys permanently or swap them for new ones at a later date. Orders are

Circa Systems co-founders

Samantha Wittchen, Nic Esposito and Blake Carroll want to start a robust used toy market to cut down on extraction and waste.

delivered by e-bike in a toy chest to the member’s home.

“We’re giving you the toys you bought, picking up the ones you don’t want anymore, spiffing them up, making sure that they’re ready for users again, and we sell them over and over,” Esposito says.

“It’s really about sharing these things across multiple families over a period of time,” adds Wittchen.

When inventory needs to be retired, items will be recycled through Philly’s Rabbit Recycling.

For the pilot, Circa gathered 1,500 toys through collection drives — everything from small action figures to a large Hot Wheels playset.

During the pilot, users don’t pay the membership fee and toys are all used, but in the future Esposito says there will be new toys on the site. “Well-loved” toys have a 70% discount and new toys will have a 20% discount off list price.

Esposito says Circa just closed its pre-seed funding round with $350,000 and will be looking for more investments to ramp up the scale of Unless Kids and eventually move into other markets, such as sporting equipment.

Blake Carroll, co-founder and chief operations officer, said Philly is the perfect place for Circa Systems and endeavors like Unless Kids — there’s already a “tight-knit” community of sustainability entrepreneurs willing to share ideas and challenge norms.

With the support of these local environmentalists, Carroll hopes Circa can push Philly to become a leader in the circular economy.

“We have this opportunity to help shape the future of what Philadelphia could look like,” Carroll says, “and not by necessarily using the same tools that have been applied over the course of history.” ◆

4 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024 circular economy PHOTO BY JARED GRUENWALD

Spreading Community

Aaji’s finds a growing market for lonsa, and gives back

Launched in 2021, Aaji’s is first and foremost, a family affair. Co-founders Rajus and Poorva Korde created the brand based on Rajus’s grandmother’s tomato lonsa recipe — a tomato-based dish that incorporates coastal Indian spices like asafoetida and turmeric. Aaji’s currently offers an original tomato lonsa, as well as garlic, spicy and spicy garlic flavors.

“We take these tomatoes and we cook it down for several hours until it turns into this really lovely consistency,” Poorva says. It makes a delicious topping and can also be used as a base or ingredient to add a punch of flavor to a variety of dishes, she adds. “The number one way people eat it is spreading it on bread and eating it with eggs.”

“Aaji” means “grandmother” in Marathi, a language from the midwest coast of India. Rajus’s aaji is still involved in the brand, along with Rajus’s brother as head of finance and operations and their dad as an advisor.

From the get-go, Aaji’s has been a com-

munity-forward project. The Korde family chose tomato lonsa after gathering close to 700 surveys from neighbors on what dishes they’d be interested in trying. Tomato lonsa came in the top 10. Then, it was on to Philly farmers markets. “We took 60 units of lonsa with us to the Fairmount Farmers Market, really unsure of what to expect, and within two hours we’d sold out of everything we brought,” Poorva says.

Customers at the farmers markets introduced the business owners to Weavers Way — one of the first retailers to take a chance on Aaji’s. Since then, Aaji’s has maintained a close and impactful relationship with the store.

“Weavers Way hasn’t just been a new chain of stores we’re in, but another community,” Rajus says. “We got to know everyone on a personal level and they were all so supportive of us in giving us feedback and meeting with us over coffee and supporting us in events and just celebrating. It really

The Weavers Way Vendor Diversity Initiative provides assistance, support and shelf space for makers and artisans who are people of color.

became this very endearing relationship that we’re still so grateful for.”

Aaji’s also credits its association with a respected community market like Weavers Way to the brand’s growing availability in other retailers, such as the Swarthmore and South Philly Co-ops, as well as Kimberton Whole Foods.

Looking to the future, Aaji’s plans to expand the reach of its tomato lonsa, building on the foundation that Weavers Way has given them. This summer, Aaji’s will sell at 16 farmers markets spanning Philadelphia and its surrounding counties, all the way to South Jersey and the shore. The brand also recently expanded to Di Bruno Brothers and, next month, Aaji’s will be available at MOM’s Organic Market locally in the Philadelphia region.

The team is also starting to revisit their product development list; Aaji is back in the kitchen working on a new recipe to bring forth in the coming years.

Aaji’s also looks to give back to the Philadelphia community beyond culinary contributions. The company’s cause is centered around grief: Rajus’s brother sits on the board of the Uplift Center for Grieving Children — which Aaji’s also donates proceeds to — a nonprofit that provides support for children and families that have experienced loss. One in five Philadelphians loses a parent or sibling by the age of 20, and Aaji’s is on an emotional journey to give back to the Philadelphia community as the brand’s platform grows.

“Philly has been an amazing place to start this business. We’re not Philly natives but our second son was born here. Starting a food business, you tap into the community very deeply and very quickly through the farmers markets, grocery stores and coops,” says Rajus. “There’s this sense of camaraderie and collegiality. We’re trying to make each other proud and make Philadelphia proud in a way that I think is part of every brand coming out of Philly.”

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 5

◆ sponsored content

MIKE PRINCE

From left: Poorva, Ashwin, Vijoo, Arvind and Rajus Korde have built the Aaji’s brand together from the ground up.

by kyle bagenstose

BUDGET OVERFLOW

Since 2012, Philadelphia has been installing green roofs and rain gardens to solve a massive sewage problem. With rising costs and implementation setbacks, it may be more aspirational than feasible

Ever since the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD) created a plan to fix its archaic sewer systems in 2011, proponents have held up the resulting program — Green City, Clean Waters — as a crown jewel of the department.

But more than a decade later, signs are emerging that the nationally-recognized plan might be serving as a drain on the utility’s coffers — by the billions.

The program was originally pitched as an innovative, cost-effective way to deal with the billions of gallons of raw sewage that overflow annually from the city’s vast expanse of aging sewer lines and spill into rivers and creeks. While an originally estimated $2.4 billion price tag for the 25-year program is no small amount, proponents who argued for its creation said that sum would provide a major discount compared to typical alternatives.

In cities like Milwaukee, Chicago and Washington, D.C., many billions of dollars have been spent solving sewer issues by drilling giant underground tunnels to store excess sewage until enough treatment capacity becomes available to treat it. But in Philadelphia, Green City, Clean Waters is instead designed to install thousands of diffuse pieces of “green infrastructure,” like rain gardens and tree-lined sidewalks, to capture rainwater and keep it from ever overwhelming sewer lines in the first place.

Supporters like Howard Neukrug, former commissioner of PWD who spearheaded the creation of Green City, Clean Waters, says its price tag paled in comparison to tunnel proposals.

“All the tunnels have nicknames. Ours was ‘the 100-year-tunnel,’” Neukrug said in an interview last year. “That’s how long it would take for us to be able to, in a city like Philadelphia, find the $10 billion dollars, put it in the rate structure and have people pay for this thing.”

But the costs of the green program have quietly ballooned to at least $4.5 billion at its

OUR WATER MATTERS is an ongoing series produced through an editorial collaboration of the Chestnut Hill Local, Delaware Currents and Grid Magazine

6 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024 water

halfway mark, according to both publiclyavailable financial documents and PWD employees, placing it at least $2 billion over original cost estimates. Costs are primarily borne by Philadelphians, who pay via a designated “stormwater charge” on their monthly water bills.

In a series of interviews, three PWD employees with direct knowledge of Green City, Clean Waters, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid professional reprisal, say they’re concerned about cost increases and whether green infrastructure works as well as envisioned. Meanwhile, recent internal estimates of the costs to install tunnels instead have come in significantly lower than originally predicted over a decade ago.

According to the employees, the cost of greening an acre of land in Philadelphia has jumped from an original estimate of about $175,000 to above $500,000, and a significant portion of such installations have also run into performance trouble.

Sometimes, plots of vegetated green infrastructure simply fail, either overwhelmed by

the stormwater they’re supposed to contain, or stricken by plant die-off due to poor soil conditions or pollution. In other cases, the installations only partially work, requiring expensive repairs or ongoing maintenance.

And, the employees said, there are internal conversations amongst PWD staff that they are running out of public space to install new green infrastructure, and that measures to spur adoption by private landowners are not meeting expectations. As previously reported, at current rates of installation, PWD is indeed on pace to miss the EPA’s mandate of greening 9,500 acres by 2036.

Saving green?

While it’s fairly common for major public infrastructure projects to run over budget and past deadlines, concerns with the City’s sewer program revolve around its experimental nature. Hailed nationally as innovative, the program was designed to spend the majority of its dollars on green infrastructure, making Philadelphia the only major U.S. city to take that approach.

When formalized in 2011, officials said about 70% of the money spent on Green City, Clean Waters would go toward green infrastructure, while 15% would go toward traditional “gray” infrastructure and another 15% would remain flexible. But with more than a decade of data now in hand, employees and clean water advocates question whether that ratio is still the right one.

In 2021, an internal working group was established within PWD to freshly assess cost differences between green infrastructure and more traditional options such as large tunnels. According to internal documents, a meeting was held on green infrastructure costs in May 2023. During that meeting, documents show, PWD employees presented information concluding that costs to install a single “greened acre” (a term used to refer to the volume of water green infrastructure can hold during a storm; it does not measure land area) had reached an average of $348,000.

That figure represented about a 100% increase over the $150,000-to-$200,000 cost, according to department documents and

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 7 PHOTO BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

Storm sewer outfalls, such as “T1” near Ogontz and Cheltenham avenues, disgorge a mix of rainwater and raw sewage after heavy rains.

BY THE NUMBERS

$2.4 BILLION

Original Cost Estimate

employees, that PWD originally estimated a decade ago. Two employees say even more recent calculations now place the cost to install a greened acre above $500,000.

PWD records show the utility still has some 6,700 acres left to green by 2036 under their agreement with the EPA. If the cost of each acre averaged $500,000, the total would reach $3.4 billion — on top of what has already been spent on the program.

PWD declined an interview request for this story, but a spokesperson provided detailed written responses to questions and said the most recent total cost estimate of $4.5 billion included future expenses.

At the May 2023 meeting, PWD employees also noted a steep rise in the costs of maintaining green infrastructure. The original 2011 plan, they said, estimated annual operations and maintenance costs for street trees, rain gardens and green roofs would cost a few thousand dollars a year per acre. But over a five-year period ending in 2022, actual field maintenance costs came in several fold higher. In responses to this story, PWD confirmed that such costs are now estimated at $10,000 to $12,000 a year per greened acre.

Exacerbating the problem, while employees at the meeting stated that administrative costs of the program should not increase linearly with the number of greened acres installed, that’s exactly what was happening. Over the prior five years, such program costs rose from about $1.1 million to $2.1 million a year, according to analysis relayed at the meeting.

A PWD employee familiar with the program says that when original financial esti-

$4.5

BILLION

Current Cost Estimate of Green City, Clean Waters

mates were made, planners and leadership assumed the costs of installing green infrastructure would decrease as efficiencies of the program progressed and designs and procurement became standardized. But that largely hasn’t come to pass, they say. Variables such as soil conditions have proven

finicky, prematurely ending the lifespan of some installations and requiring custom designs for many. These problems have in turn shifted the anticipated lifespan of a typical green installation from 25 to 40 years to less than 20, driving up maintenance costs and keeping design costs high, the employee said.

These twin problems create a catch-22: spend a lot of money upfront on custom designs that have better chances of working, or pay on the backend when more generic installations start to break down.

“Some designers are very frustrated because they don’t feel like they’re doing the best designs they can,” the employee says. “Because they’re just trying to hit an [installation] target — an insane target.”

PWD did not deny Green City, Clean Waters has seen significant cost increases, confirming it had calculated that costs to install a greened acre had risen to $348,000 as of 2020, due to labor and price disruptions following the COVID-19 pandemic. But,

8 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024

water

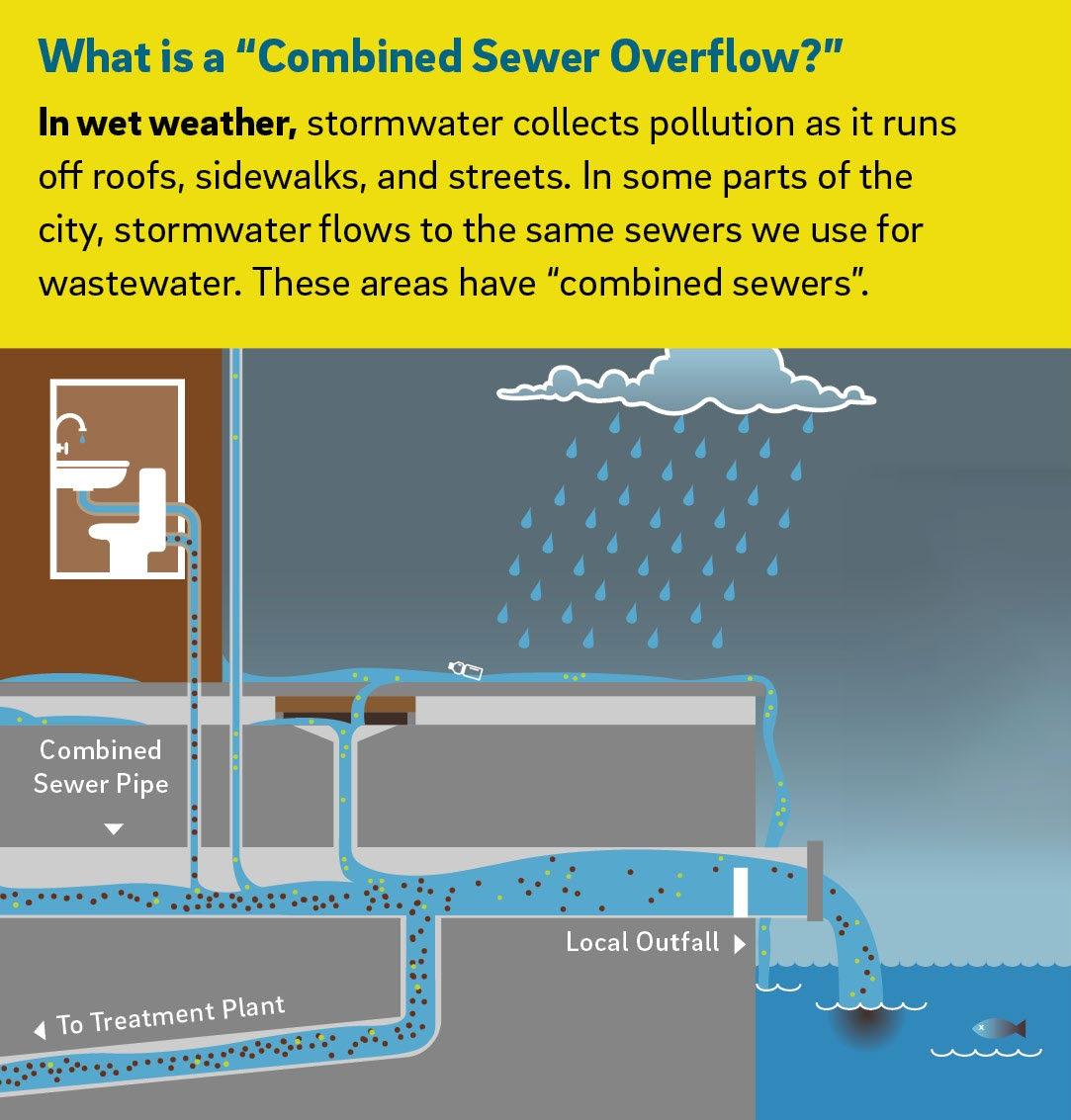

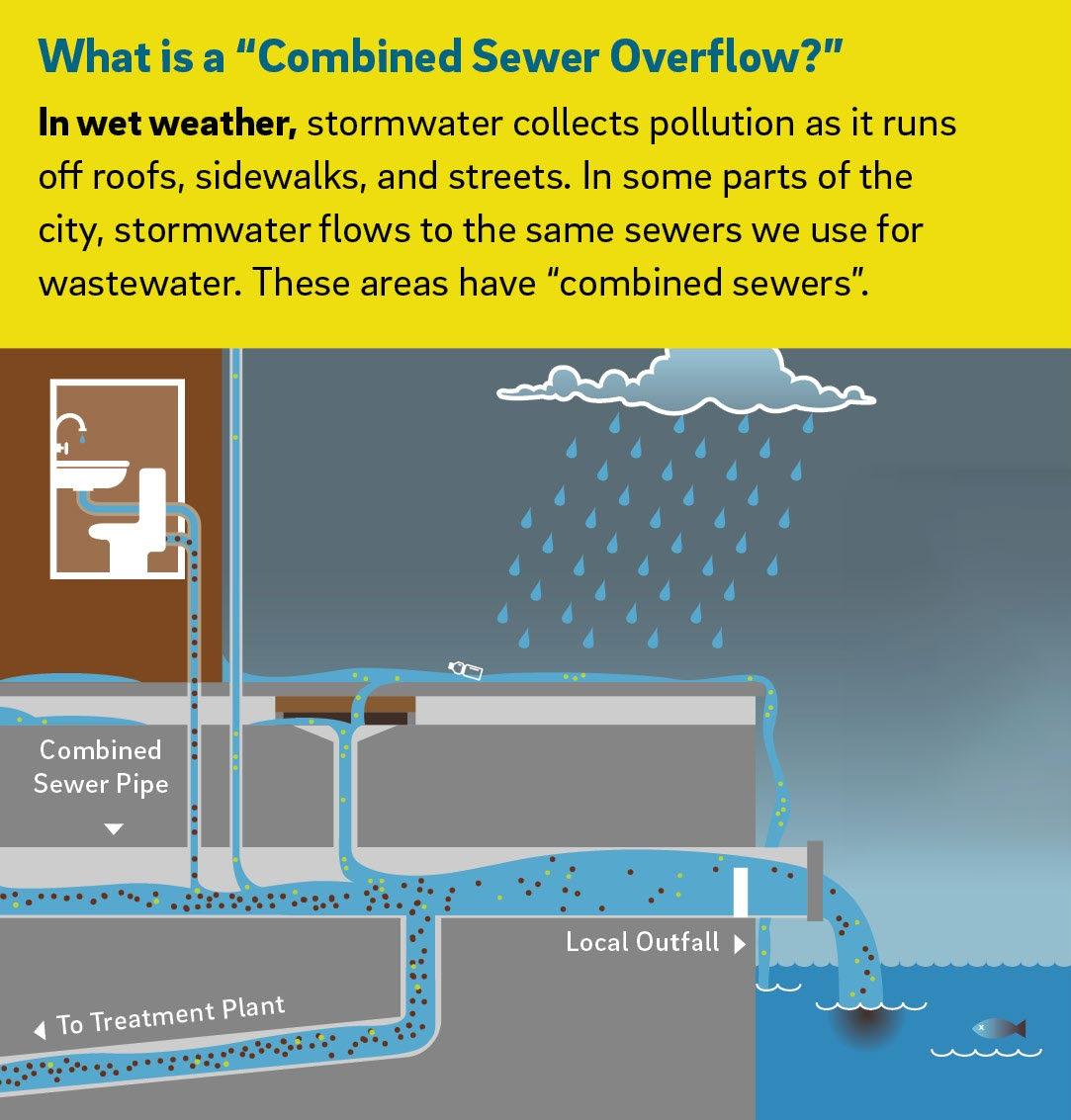

Wastewater combined with dirty water from streets can overflow into waterways.

They’ve never had a backup plan. So many people have their reputations wrapped up in this. Nobody wants to say anything.”

philadelphia water department employee

the utility pushed back on the idea that cost increases were due to major flaws with the program’s design.

Of 830 pieces of green infrastructure installed in the last 13 years, only 20 have been “retired or [are] pending retirement,” the department said. It also claimed that PWD “currently estimates the engineering service life” of green infrastructure to be at least 50 years, not less than 20.

“PWD disagrees with the notion that issues with [green] installations pose a sig-

nificant challenge for the program,” it said. “Our program is designed to learn from reallife conditions; when faced with real-life applications and lessons learned, we are able to update planning and design guidance to facilitate improvement of future projects.”

The utility’s response also touted the program’s successes, including an estimated reduction of 3 billion gallons of sewage overflows a year through the installation of more than 2,800 pieces of green infrastructure, while supporting “both jobs and green

economy creation.”

The utility also disputed that the program’s administrative costs had grown unwieldy.

“While it is accurate that the program management costs have increased, they have done so commensurate with increased responsibility,” PWD said. “This program management budget supports tasks including asset tracking, work order management, and materials management, among others.”

Green vs. Gray

Though there are no signs publicly that the Philadelphia Water Department has any doubts about its commitment to Green City, Clean Waters and the program’s prioritization of green infrastructure, internally, the picture looks different. Employees say the program has been polarizing from the outset, sorting people both inside and outside PWD into camps that “support” or “oppose” Green City, Clean Waters.

“I came in very excited and invested in green infrastructure, but over time I understood the limitations and challenges with implementation,” says one employee, who’s been with the utility for over a decade and has firsthand knowledge of aspects of Green City, Clean Waters. “The ‘non-green’ people stayed skeptical, but the ‘green people’ became skeptical just seeing these challenges.”

Some PWD employees also say they are concerned that leadership at the department is unresponsive and has yet to seriously consider changing course on the sewer program.

“They’ve never had a backup plan,” one employee says. “So many people have their reputations wrapped up in this. Nobody wants to say anything.”

Sources place particular blame on PWD commissioner Randy Hayman for a perceived failure of leadership. They say they were surprised to learn he’d been retained by Cherelle Parker’s administration after several employees explicitly made their concerns known to the mayor’s team during the transition period.

“All evidence to the contrary,” Hayman said in a written response to the accusations. “Our team has continually utilized data collection, analysis and planning processes to evaluate progress, make program enhancements, identify risks and opportunities, and

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 9

ensure we are making progress as needed.”

But some PWD employees insist that the department is uninterested in changing tack. For proof, they point to the Northwest neighborhood of Germantown.

A tale of two neighborhoods

Underneath Germantown lies the city’s most polluting combined sewer line, which dumps hundreds of millions of gallons of diluted sewage into the Frankford Creek each year. The undersized pipe is also the culprit of basement sewage backups and contributes to area flooding, causing up to $8.72 million in property damages each year, the PWD’s own estimates show.

Germantown is also the site of the only major tunnel proposal the Philadelphia Water Department currently has on the books. Early assessments estimate that placing a large tunnel there could reduce flood depths in Germantown by as much as 80% and eliminate up to two-thirds of basement backups.

But, some PWD employees say, any progress on the idea has languished as green infrastructure continues to take priority within the department.

“It’s just something that’s never going to advance,” says one employee with knowledge of capital projects.

They add that the project has been put into a sort of assessment purgatory. In 2019, engineering firm CH2M delivered a 17-page study to PWD identifying potential tradi-

water

BY THE NUMBERS

A “Greened Acre” is a term used to refer to the volume of water green infrastructure can hold during a storm

Greened Acre Construction Cost Estimate

tional infrastructure projects to help in Germantown, such as a large tunnel. The next year, PWD convened a community task force to discuss flooding in the area.

But then, employees say, a decision was made to further study the possibility of a tunnel and PWD opened a new contract for a preliminary assessment. While the department has selected the engineering firm Brown and Caldwell for the work, it is still seeking federal funding to pay for it. The proposal is now more than a year behind schedule with no apparent start date on the horizon, while the price tag for the study — $5 million — represents only a fraction of a percent of what PWD is spending on Green City, Clean Waters.

However, PWD pushed back on the notion that the new study is in any way superfluous, saying it is “necessary to confirm additional areas of feasibility and optimize our design.”

“PWD is very diligent at utilizing its funding and does not intentionally delay projects,” PWD added.

Internal PWD documents show that costs to construct such a storage tunnel are likely substantially lower than what original estimates predicted in 2009, when the push for a green-infrastructure-first approach was underway.

In 2022, the working group established within PWD to re-evaluate costs held a meeting on tunneling options. Information presented showed that in 2009, PWD had esti-

$500,000

$175,000 Greened Acre Current Construction Actual Cost

mated a large sewer tunnel, depending on its width and length, could cost anywhere from about $400 million to $1.7 billion to build.

But more recent cost estimates for a tunnel under Germantown came in significantly lower after examining real-world projects like the tunnels Washington, D.C. is digging. In one scenario, the new estimates showed a 20-foot diameter tunnel stretching more than five miles could be built for about $750 million, compared to a 2009 estimate that ran over $1 billion.

Josh Lippert, a professional floodplain manager and former chair of Philadelphia’s Flood Risk Management Task Force, says he believes the reluctance to push forward with a Germantown tunnel is largely due to a lack of political pressure. In trendy Northern Liberties, he notes, PWD is spending more than $93.5 million on traditional infrastructure to fix the buried Cohocksink Creek combined sewer line and cut down on flooding. But in Germantown, a predominantly Black and working class neighborhood where a 27-yearold mother drowned while driving in 2011, the status quo remains.

“We’ll continue to have fatalities because they did a million-dollar study that has now sat on the shelf because there is no political action to take that forward,” Lippert says.

PWD again pushed back on this notion, noting the Germantown project is about five times the scale of Northern Liberties.

“When completed, the cost of the [Germantown] flood relief project will dwarf expenditures in the Cohocksink flood relief project,” the department said. “It would [also] be inappropriate to draw a comparison of expenditures at two very different points in the process.”

D.C. asks: “To green or not to green?”

Philadelphia isn’t the only major city in the U.S. to weigh the merits of trees and tunnels to stop sewage overflows. In a case strikingly similar to Philadelphia’s, one utility — the District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority (DC Water) — took a different tack, and has seen significantly different results a decade later.

In the early 2010s, DC Water was renegotiating its own agreement with the EPA over its combined sewer overflows affecting the watershed of the Potomac River, a 405-mile waterway that originates in West

10 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024

water

No matter how much green infrastructure that we build and do, I still think there are going to be things that we need to do as far as old school infrastructure buildout that will put these protections in place.”

mark squilla, Philadelphia City Councilmember

Virginia before snaking through the district and emptying into the Chesapeake Bay. The utility pressed to create a green-centric plan similar to Philadelphia, says Dean Naujoks, Riverkeeper for the Lower Potomac River, which had been signed off on and even championed by EPA leadership just a few years earlier. But with the Potomac and its tributaries heavily choked by sewage and other pollution, he was among those skeptical of that approach.

Echoing some critics of PWD’s Green City, Clean Waters, Naujoks says he simply wasn’t convinced that spending billions of dollars on large-scale green infrastructure

plans was going to adequately clean up the Potomac and a primary tributary, the Anacostia River, to regulatory requirements. In his experience, the most successful green infrastructure projects were those newly built in large, open space settings. Where planners run into trouble, he says, is trying to retrofit them into dense urban areas like those found inside the Beltway.

“The amount of stormwater that can be picked up from these kinds of pocket parks and retrofits is inadequate,” Naujoks says, adding he believes EPA staff were also concerned the plan wouldn’t meet clean water standards.

As stakeholders began to weigh in both behind the scenes and in public comments for DC Water’s sewer plans, Naujoks says the Potomac Riverkeeper Network threw its support behind an approach that still invested heavily in traditional infrastructure like tunnels.

In the end, that philosophy largely won the day. In 2016, DC Water finalized a $3.3 billion plan called the Clean Rivers Project. John Lisle, spokesperson for DC Water, says that only about $98 million of that sum is directed toward green infrastructure — primarily used to clean the tributary Rock Creek, where DC Water had the most confidence it would serve as a suitable substitute for traditional methods.

“This approach is feasible in this sewershed because of its low [sewage] overflow volumes and because of the lower density of development in the sewershed,” the utility concluded, adding it would still closely monitor progress and change course if needed.

DC Water then plowed most of its funding into the construction of six underground sewage storage tunnels scattered across its coverage area. When fully complete, they will

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 11 ROBERT K. CHIN/ALAMY

Efforts to encourage adoption of green stormwater infrastructure by private landowners have been a disappointment.

stretch a combined 18 miles and store 249 million gallons of sewage during rain events.

Last year, workers completed a fourtunnel system along the Anacostia that they began drilling in 2011 — a year ahead of schedule and on budget, Lisle says. The utility calculates the system now captures about 98% of sewage overflows and the riverkeeper network is pushing for the first legal swimming event in the Anacostia in more than 50 years.

“The Anacostia is definitely improving,” Naujoks says. “In general we have a lot more swimmable days than we used to.”

What say the watchdogs?

While clean water advocates and utilities debate the best ways to reduce sewage overflows, there are three entities with actual power to decide the merits in Philadelphia: the City’s elected officials, the EPA and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

As previously reported, annual reports issued publicly by PWD for regulatory purposes maintain the program is on-track and even prospering, with the utility currently hitting every regulatory target it agreed to when the program was created in 2011. Chief among them is the greened acre, for which PWD has hit five- and ten-year installation targets. An analysis of annual reports shows that, when adjusted for annual rainfall, the City has achieved about a 21% improvement in sewage overflows from a decade ago.

However, the amount of new greened acres that need to be installed accelerates in each five-year period, and several PWD employees say there is internal skepticism that PWD will meet its next target in 2026. And from the very beginning, some experts have had their doubts about whether a greened acre is even an accurate metric to use to ensure water quality improvements.

According to David McGuigan, a former associate director at the EPA’s regional offices in Philadelphia who oversaw wastewater permitting, some program staff at the EPA lacked confidence early on that the plan would achieve necessary pollution reductions in each of Philadelphia’s three sewer districts.

“It was not an engineering solution. It was an aspirational solution,” McGuigan said. “I think that’s what caused the most

It was not an engineering solution. It was an aspirational solution.”

david mcguigan, former EPA associate director

concern. It did not propose verifiable targets and reasonable certainty.”

There is still indication that staff at the EPA hold some reservations about the program.

According to McGuigan, program staff there have withheld approval of permits for Philadelphia’s three wastewater treatment plants for more than a decade, in large part due to concerns over Green City, Clean Waters. McGuigan says that, as currently designed, the sewer program is ambivalent about where green infrastructure is installed within Philadelphia; EPA staff want it implemented strategically throughout the city to ensure that even smaller, vulnerable waterways like Frankford and Cobbs creeks are protected.

“That’s the underlying battle. The Clean Water Act requires that all cities attain water quality standards for all of their receiving waters,” McGuigan says. “For example, Cobbs Creek — people are there every day. Children play there. When there’s a [sewer overflow] event there, Cobbs Creek will have hazardous bacteria levels.”

McGuigan says Philadelphia has refused to accept requests to add such a watershedspecific approach, which he believes the Clean Water Act requires. In 2012, the DEP issued a draft permit for the treatment plants anyway, but the EPA didn’t sign off and responded with an objection that has left the plants operating on 2007 permits ever since, when they’re supposed to be renewed every five years.

A PWD employee familiar with the issue recalls a flurry of concern in 2016 when the department received a formal letter on the matter from the EPA. Staff performed analyses to determine whether they could comply, but ultimately decided against agreeing to do so. The issue remains unresolved, the employee says. “We haven’t been able to come to an agreement.”

In emails, neither communications staff

for the EPA nor DEP took significant issue with this framing. The EPA confirmed it had objected to language in a draft permit the DEP issued in 2013, and says it “continues to work closely with PA DEP to resolve this objection.”

PWD also confirmed it had received a letter from the EPA, but that discussions concluded when EPA “stayed” the letter in April 2017. The utility also hinted at its reasons for pushing back on the EPA’s requests, saying that “modification” of its plan at the halfway mark “would have significant schedule and cost implications.”

At the local level, EPA records obtained via open records requests show that in 2022 and 2023, Philadelphia City Councilmember Mark Squilla peppered Philadelphia Water Department officials with detailed inquiries about their efforts to reduce sewage overflows. He also helped orchestrate a City Council hearing on the topic in October 2022.

Of particular importance to Squilla were “dry weather overflows,” or sewage leaks that occur from the City’s pipes even when it isn’t raining, which are illegal under the Clean Water Act. An August 2023 email from Squilla to Hayman appeared to reflect a deeper frustration at failure to answer wider “outstanding requests” about the sewer program.

“To help respond to questions from Philadelphia residents about why their rivers are not clean enough for wading and recreating, please provide me this information by September 1,” Squilla wrote.

Asked about his communications with PWD in a March 2024 interview, Squilla said that he “whole-heartedly supports” Green City, Clean Waters and framed his interest in the topic as supportive. Squilla primarily wants to assist PWD in finding additional public funding from federal or state coffers to complement the program, he said.

But the councilmember also added that he thinks the City “should be doing more”

12 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024

water

Washington, D.C.’s Northeast Boundary Tunnel prior to its opening in September 2023. The five-mile-long, 23-foot diameter tunnel reduces about 98% of sewage overflows into the Anacostia River each year, according to DC Water, and can also reduce flooding 7 to 50% in a given year.

to address the sewage overflow problem and framed Green City, Clean Waters as “a part of the solution.” Asked if that meant he thinks more traditional infrastructure is needed, Squilla answered affirmatively.

“You know, no matter how much green infrastructure that we build and do, I still think there are going to be things that we need to do as far as old school infrastructure buildout that will put these protections in place,” Squilla said.

While PWD did provide detailed responses to Squilla following his August 2023 email to Hayman, the councilmember said he is still actively pursuing responses from the department on remaining questions.

Money is another matter. While both the EPA and DEP said costs are considered while creating sewer plans like Philadel -

phia’s, neither said there was any ongoing requirement for the City to ensure the program stays on budget or remains affordable for its ratepayers. The City’s annual reports thus do not include comprehensive financial accounting or analysis of cost effectiveness.

The big picture

Lost in this maze of challenges facing Green City, Clean Waters is the evidence that green infrastructure does work, at least at small scales.

When DC Water was performing its own green infrastructure experiment around Rock Creek, the utility found it captured about 20% of sewage flows into the waterway — on the low-end of a 19-to-41% range of expectations.

Philadelphia’s green gamble continues

with much higher stakes. The City appears to be making some progress, with its own accounting estimating an annual reduction of about 3 billion gallons of sewage overflows in a typical year. But that leaves it with another 5 billion gallons to go. And while clean water advocates point out that these figures are modeled and don’t account for climate change, no one can say with certainty exactly where PWD will wind up in 2036 if it stays the course.

There are also collateral benefits of Green City, Clean Waters that are hard to quantify. Regular installation and maintenance of green infrastructure provides local jobs. Greenery beautifies neighborhoods, with some studies showing it can reduce crime and improve mental health. It’s also more emissions-friendly than tunnels, which require copious energy to pump the water out after storms.

Robert Traver, an environmental engineer and director of Villanova University’s Center for Resilient Water Systems, says it’s taken hundreds of years to pave over the city, and that such benefits are worth the time it takes to unpave it.

“If I’m the mayor, and I’m spending money, I’m seeing [the benefits of] addressing the heat island effect, a little bit better air quality, a little prettier as you walk down the street, especially in those environmental justice neighborhoods that don’t have a lot of green,” Traver says. “All of those benefits should be brought into the equation.”

Just how much one prioritizes these attributes, compared to the primary goal of cleaning up waterways, colors their assessment of how well the program is working.

And even among those who believe there are major problems with Green City, Clean Waters, uncertainty exists over the alternatives. One such PWD employee estimates that the Germantown tunnel proposal might only get the City about 10% of the way to where it needs to be on reducing sewer overflows, and that there would need to be at least several more constructed.

Still, given all they know about how the program is faring, the employee can’t help but shake the feeling that things have gone awry.

“I often think about, how is this actually going to come to fruition?” they said. “Before you dump more costs into it, the biggest concern looming is, can you even do it?” ◆

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 13 COURTESY OF DC WATER

The Beer & Cider Garden

is back

Thursdays & Fridays 4pm to 10pm

Saturdays Noon to 10pm

Sundays

Noon to 9pm

Look for our tent next to Water Works

14 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024

the environmental justice issue the environmental justice issue the environmental justice issue

I I I

n this issue we take a closer look at how environmental problems disproportionately affect communities of color, and particularly low-income communities of color. ¶ More than those of whiter and more affluent communities, their residents breathe air poisoned by industrial facilities like refineries or by the tailpipes of unending lines of cars and trucks. Often homes are not even a refuge, presenting hazards from flaking lead paint and exhaust from cooking gas. And sometimes the very ground sinks beneath their feet, undermining foundations and severing gas lines. ¶ Our region is also rich with solutions that can help repair the inequities. Some require the reform of government and regulation of industry, but we all can take steps to clean our air by getting around by any means other than a personal gas guzzler. We can improve indoor environments through home repair programs and we can spark joy in youth by connecting them to our restored rivers and green spaces. ➤

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 15

KRISTEN

PHOTO BY

HARRISON

HOLISTIC Improvement

Free repair program makes homes more livable and sustainable, staves off gentrification and makes neighborhoods safer ➤

BY ALLISON BECK

Antonette Russell’s house, like many others in Grays Ferry and neighborhoods across the city, has been in her family for decades.

Her grandmother, community leader Irene Russell, was the first in the family to own the century-old, two-story brick row house on South Napa Street. The matriarch famously worked to improve nearby Stinger Square Park, leading a campaign that culminated in a $350,000 project

to install new playground equipment and a softer play surface.

“She was like a grandma to people that wasn’t even her grandkids, a mom to other people’s kids,” Russell says.

Before she died in 2021, her grandmother had started some much-needed repairs on her house, but many remained undone. The appliances in the kitchen were falling into disrepair and the bathroom was beginning to crumble. Russell believed it would take

years before she could afford to finish the job. Everything changed when she got a call from Philly Thrive; her home would be the first served by the environmental justice organization’s free home repairs program.

“I’m not a real emotional person, but I could’ve cried that day,” she says. “It was just like, yes, thank you. My grandmom, she’s a blessing, and she’s still blessing me even though she’s not here in the physical.”

At an unveiling event in March, Russell showed eager visitors her new bathroom, with its fresh coat of paint, new sink, toilet and redone shower.

“The environment plays a big role in your life. A lot of people are stressed, depressed, hungry, it goes on and on and on,” she says. “It’s just good to have something new that’s like putting on a fresh pair of sneakers or a new outfit. I feel like once this house is done, I’m probably gonna have a whole different attitude.”

According to a community survey con-

16 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024 the environmental justice issue PHOTOS BY KRISTEN HARRISON

Antonette Russell speaks on her porch in Grays Ferry at the unveiling of her home’s repairs, which were made possible by Philly Thrive.

The environment plays a big role in your life. I feel like once this house is done, I’m probably gonna have a whole different attitude.”

ANTONETTE RUSSELL

Grays Ferry resident

ducted by Philly Thrive, a community organization dedicated to environmental justice in Grays Ferry, 50% of the neighborhood’s residents need or would significantly benefit from a home repair program.

The organization hopes to solve these problems with its new program, which aims to provide free repairs, electrification and solarization to homeowners who cannot afford them.

Thrive representatives say that the group is working to fund the program through grants and community benefits agreements. Because the group is considered a Registered Community Organization (RCO) by the City, they often play a deciding role in new zoning and construction. During the zoning process, they can negotiate for benefits to offset the damage caused by developers.

The Russell family home was repaired using money from one of these agreements; Philly Thrive is waiting on additional funds from developers and grant programs to continue the work. In the meantime, they are collaborating with Habitat for Humanity.

Two problems arise for homeowners who are unable to shell out the thousands of dollars needed to fix worn down roofs,

plumbing and other common issues. First, the longer they delay repairs, the worse the problems become; second, aging appliances use more energy.

When they can no longer afford to maintain their homes, residents say they are forced to sell to eager developers. If they want to stay in their community, it often means renting from the same landlords that are gentrifying the area.

While programs exist to make retrofitting more affordable, most come in the form of tax credits — money that only reaches homeowners after they’ve paid for renovations. That doesn’t work for those living paycheck to paycheck.

Thrive’s program mirrors a citywide initiative called Built to Last, which pulls together the different programs available to low-income Philadelphians to create a more streamlined and accessible process.

Since its pilot in 2021, the Philadelphia Energy Authority program has served 125 homes and has about 180 more currently in the repair process. As funding and capacity are limited, about 1,300 are on a waitlist, which stands at a few months long, according to officials.

“It takes a long time for the repairs to happen and folks are rejected without a clear way to appeal,” says Ella Israeli, a public policy fellow at Philly Thrive. “In addition, it faces a challenge of many public programs: if people are even $1 over the income limit, they are ineligible.”

Thrive hopes to fill the gap in part by prioritizing homeowners who are unable to access other programs because of issues like tangled titles, income limits or types of repairs needed.

Despite their frustrations with the program’s barriers to entry, advocates continue to call on elected officials to fund Built to Last because of its environmental justice and climate change impacts.

“You have an organization that aims to turn the tide on global warming and greenhouse gas emissions by helping residents change over to clean energy sources,” Thrive co-director and policy coordinator Shawmar Pitts said at a screening of a documentary about the program. “We’ve got a surplus in our state budget right now, and they told me it was for a rainy day. It’s raining right now. We’ve got to put the pressure on.”

Developers are more likely to tear down old homes and replace them with new construction, which has a higher carbon footprint than making repairs to existing stock.

According to a nationwide study by a group of architects and green building advocates, building reuse almost always offers environmental savings over demolition and new construction over a 75-year lifespan. It also creates more jobs and promotes community resilience

Retrofitting also means more savings for homeowners in the long run. By improving insulation alone, Pennsylvania homeowners can save between $116 and $530 on utility bills every year.

Residents’ health is also impacted by homes falling into disrepair. According to a report by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, weatherization programs could reduce asthma, falls and exposure to extreme heat and cold.

This also extends to public health and gun violence. One study conducted by the University of Pennsylvania from 2006 to 2013 found a 21.9% reduction in total crime on blocks where low-income residents received grants to make basic repairs to their homes.

Grays Ferry and Passyunk saw 22 shootings in 2023, according to the Office of the Controller. The statistics became even more real for members of Philly Thrive when two of their own were murdered.

El-Amin Wilkins was a lifelong Grays Ferry resident who cared deeply about youth and housing justice. He was shot in December 2023, less than a block from where Thrive’s first home repairs took place. Edison “Big D” Frazier was passionate about food and dreamed of opening a food truck business and bringing jobs to neighborhood teens. He was shot in Strawberry Mansion in January 2024.

“We know gun violence affects us. It always comes close to home,” Pitts says. “So when we do whole home repairs, it decreases the gun violence. When you invest in a community, it decreases gun violence.”

Antonette Russell finds hope for her neighborhood through Thrive’s program.

“I’m hoping this brings the community back together and everybody tries to get involved in some way, shape or form,” Russell says. “I just want to see them be successful, the neighborhood come together, that’s it.”

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 17

◆

In my back yard

grid talks with professor and author Dorceta Taylor about how communities of color became ground zero for toxic industries ➤ INTERVIEW BY AMBER X. CHEN

Why is it that low-income and communities of color bear the brunt of industrial pollution?

And when environmentally hazardous facilities move into their neighborhoods, why don’t people leave?

These are some of the questions that guide the environmental justice movement, which seeks to address the disproportionate environmental harm marginalized communities face. Dorceta Taylor, professor of environmental justice at the Yale School of the Environment, is one of the movement’s preeminent scholars. In her 2014 book, “Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility,” Taylor takes a critical eye to the questions and theories which guide the modern-day environmental movement.

Through case studies of various neighborhoods that have been subjected to decades of industrial pollution — ‘Cancer Alley’ in Louisiana; uranium mining on the Navajo reservation across Utah, New Mexico and Arizona; a hazardous waste landfill in Emelle, Alabama — Taylor examines why low-income communities of color are disproportionately living near industrial pollution, how these environmental hazards affect their physical health and economies, and importantly, why people don’t move.

This interview was edited for clarity.

You write about famous examples of environmental injustice, such as Louisiana’s Cancer Alley and the polychlorinated biphenyl landfill in Warren County, North Carolina. How do people of color — in particular, Black Americans — end up living in these communities in the first place? In the early ’90s, an argument started to be floated by researchers, primarily white researchers,

who argued that it’s a chicken-or-egg problem: Black people and other people of color move to neighborhoods that are cheaper. Those neighborhoods are more affordable because they’re tainted, they have industrial facilities, they have waste dumps, et cetera. My first reaction to that was, show me which person on the planet deliberately gets up and moves their children and themselves into a neighborhood to live beside a waste dump or toxic facility?

I document extensively in “Toxic Communities” that the waste dump was moved into people of color’s neighborhood in many instances. People have been in Cancer Alley since slavery. They didn’t move to live beside those facilities. Those facilities came to be beside their neighborhoods.

Why is it that industries seek out these particular communities? Back in the 1980s, a document came out called the Cerrell Report. It was a report that was done in California as this waste company was looking for a place to put its new incinerator that was going to spew cancer-causing pollutants into the air. They don’t necessarily go and look for a Black neighborhood. What [the report] says is [they look] for communities that have low educational attainment, low-income, high unemployment, low engagement with community organizations that can organize them. They’re looking for people with very little ability to refuse the sites.

What we do see are those kinds of criteria mapping very closely to low-income communities of color; communities where most people speak a foreign language that hinders how you understand the social political structure, how you’re connected to it, how you’re able to organize, and can you fight effectively to stop these facilities from coming to your neighbor-

hood. We see this practice all the time. Robert Bullard in his work in Houston in the 1980s, he and his wife took some of these cases to court because there were six waste dumps in the city of Houston and five of the six were in low-income Black communities.

These facilities often say they’re going to bring in jobs, and they promise to fund schools and community programs. So what are some trade-offs that these industries typically involve community members in and how else are residents manipulated to invite these hazardous facilities in? And quite often the communities don’t invite them in. Quite often, the communities find out by sheer accident that they’re coming in or don’t find out until the facility’s built. In some cases, the facility that is built as a waste dump, eventually opens up an incinerator and the community did not ever sign off on an incinerator. When these organizations say, ‘We will sponsor the basketball league’ or ‘We will help to provide funding for kids to go on field trips,’ that’s a very small amount of money compared to what they make on the facilities.

Why is it important to examine historical processes of racial segregation — such as racial zoning covenants, urban renewal and blinding — with regards to contemporary environmental justice? The historical context matters, and it brings me to another reason why I wrote the book: Overtime, I noticed more and more scholars, students, activists — they weren’t embedding what was going on in places like Detroit with understanding how redlining and residential segregation forced people of color, primarily Blacks, into certain neighborhoods. And once they’re corralled in those neighborhoods, their garbage doesn’t get picked up, they don’t get sewer systems, the housing is terrible, and they cannot move out of these neighborhoods. Chicago, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, Atlanta — you name virtually any city of significant size in the U.S., and see racial zoning that forced people to live in some of the unhealthiest neighborhoods.

You mentioned in your research that many communities of color actually want to move out of these communities. So why don’t people just move away? It is not that

18 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024 the environmental justice issue

It is not that easy to just pick up and move. If you’re in Cancer Alley and you’re living beside the Shell facility, your house is worth virtually $0 on the market, because who’s gonna buy it from you?”

DORCETA E. TAYLOR

easy to just pick up and move. If you’re in Cancer Alley and you’re living beside the Shell facility, your house is worth virtually $0 on the market, because who’s gonna buy it from you? And so if your property value is at zero — if you’re a renter, and you cannot find any place else to live — then you tend to stay because some shelter is better than zero shelter at all. In Native American communities, there are ties to the land that go back generations, and it’s the foods that are religious and sacred that they gather. It’s the animals, it’s the plants, it’s the trees. And so it’s a lot more complicated than just thinking a noxious facility is coming into your neighborhood and you want to move.

A very common justification used by politicians is that it’s necessary for these communities to bear the burden of a landfill or an oil refinery for the “greater good of the nation.” What have you found to be the main flaws in this point of view? When you constantly ask the same one or two groups of people to bear all of the burden — and you excuse the same privileged group of people who never have to live beside these facilities and never have to work in them, but benefit from all of the money that these facilities generate — then something is fundamentally wrong. That argument becomes even more wrong when we look at a country like the U.S., that has been a racialized country

for centuries, and a country that punishes certain racial groups for simply existing. It also doesn’t encourage us to think about safe solutions: Do we need to do this process? How do we reduce our consumption footprint? Because as long as we have that convenient group of people to say, you take all the harm, you’re doing it for the good of the nation, a nation that you’re not benefiting from very much — we never get to the calculus of how we make things safe for everybody. ◆

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 19 IAN CHRISTMANN

Scholar Dorceta Taylor studies how communities of color bear the brunt of heavy industry and waste facilities.

Home Work Home Work Home Work

Environmental risks come from inside and outside the home, often from toxic building materials, localized industrial pollution or even a nearby highway. Across the country and in Philadelphia, low-income, largely Black and Brown communities experience the most severe impacts. Here are some of the environmental issues residents of our most affected neighborhoods are facing.

WRITTEN AND ILLUSTRATED BY BRYAN

Access to Green Spaces : During the COVID-19 lockdowns, a study found that people with access to green spaces were twice as likely to have a greater sense of well-being. In Philadelphia, lower-income neighborhoods have 44% less park space per capita than their higher-income counterparts. 2

Waste Management: Poorer neighborhoods suffer from the heaviest concentrations of clandestine dumping of household trash, construction waste and all manner of discarded items. 8

State of Disrepair: According to the US Census Bureau’s American Household Survey, Philadelphia ranks higher than the national average in housing with moderate to severe maintenance problems particularly in homes of low-income residents. 7

Flood Risk: Redlining, a practice of financial discrimination that forced Black and Brown Philadelphians into the least desirable and resource-poor areas, along with decades of disinvestment have left homes in these communities more vulnerable to flooding damage. 6

SATALINO

Industrial Pollution: Industrial sites, like Clearview Landfill in Eastwick and Philadelphia Coke in Bridesburg, are often located near low-income neighborhoods, putting residents at higher risk for health issues caused by toxic emissions and hazardous waste.

Lead Paint: While lead paint was banned in 1978, children tested in Philadelphia are still showing shocking levels of exposure — in some neighborhoods, five times the national average. 4 Aging water infrastructure and lead paint persistent in low-income housing are frequently the culprits.

Air Pollution: Urban air pollutants caused by traffic, industrial activities and construction disproportionately affect low-income communities of color; asthma-related hospitalizations are about four times greater among Black and Hispanic children than non-Hispanic white children in Philadelphia. 3

Indoor Air Quality: Cooking with “natural gas,” aka methane, can increase levels of benzene and nitrogen dioxide similar to those caused by second-hand smoke, increasing rates of childhood asthma and the odds of children developing respiratory illnesses.

Heat Vulnerability: Many Philly neighborhoods, including Harrowgate, Cobbs Creek and Grays Ferry have a lack of tree cover along with miles of asphalt, hardscaping and flat, dark rowhouse roofs. This causes temperatures to rise 10° F above surrounding non-urban areas. Residents in these areas are often more vulnerable due to a variety of factors including socioeconomics, age and health status. 5

20 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024 the environmental justice issue

1 SCIENCE DAILY; 2 TRUST FOR PUBLIC LAND; 3,4,5 PHILADELPHIA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH; 6 CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE; 7 US CENSUS BUREAU; 8 PHILADELPHIA OFFICE OF SUSTAINABILITY

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 21 Visit our website @ www.HopeHillLavenderFarm.com For hours and more information on our farm. Lavender Plant Sale Starting May 4th RESIDENTIAL AND COMMERCIAL COMPOST PICK-UP WOMAN OWNED MONTGOMERY COUNTY & NORTHERN CHESTER COUNTY FIRST MONTH FREE TRIAL! (610) 470-4680 // BACKTOEARTHCOMPOST.COM GIVE DAD A COOL GIFT WWW.TOMBINO.SHOP

STEP IN THE Same River

Cleanup efforts restored Camden’s waterways. These teens are bringing people back to them

22 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024 the environmental justice issue

STORY AND PHOTOS BY KRISTEN HARRISON

Last summer, on a small beach along the Cooper River, seventeen-year-olds Star Beauchamps and Mickey Carter-Lopes waited to pull canoes into shore. This was their typical summer weekday: paddling, teaching and comparing the polka dot tan lines on their feet thanks to Crocs and hours spent working in the sun.

The friends were two of last season’s eight “RiverGuides,” high school students working to connect Camden residents back to the water that surrounds them. The program is run by UrbanTrekkers, whose founders organize youth nature expeditions outside the city. It wasn’t until 2015 that they realized they didn’t have to go so far.

With Philadelphia sitting across the shoreline, most of Camden is a peninsula enveloped by the Cooper and Delaware Rivers. At the tip sits Pyne Poynt Park. Five times last summer, neighbors of all skill levels came to the park to learn how to paddle, headed by the RiverGuides and the Center for Aquatic Sciences.

There are over 200 contaminated sites in Camden today attributed to disinvestment, aging infrastructure, industrial pollution and lead seepage through the late 20th century. There’s a push to restore polluted areas, like Petty’s

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 23

Angie Garcia (far left) gives paddlers a safety demonstration as they prepare for a trek down the Cooper River.

Right: There is no shortage of wildlife on Petty's Island.

Island (known as “the place the trucks go” by Camden residents) which is being transformed from an industrial site to a nature preserve, and the former landfill that became Cramer Hill Waterfront Park, which opened to the public in 2021.

For residents, a third of whom are Black and Hispanic families living below the poverty line, interest in connecting with restored natural areas is small but growing.

Pablo Chavez, 15, knew the river pollu-

tion well. “I remember when I was little, it was just pure-on trash,” he says. His first outing on Camden’s waterways was at the start of RiverGuides training last summer. Same with Beauchamps. “I hated the water, it’s crazy. I was scared to death because I couldn’t swim,” she says. Now she’s the one consoling apprehensive Camden residents. “We had some kids that couldn’t even paddle because they were so terrified,” says RiverGuide Angie Garcia.

Below: Star Beauchamps and Mickey Carter-Lopes explore the Petty’s Island shore. Opposite, clockwise from top left: Beauchamps pulls in a boat returning to shore at the Cooper River Yacht Club; children attend an “I Paddle Camden” event; RiverGuide Naaim Presbery; an assortment of paddles.

The water is the cleanest it has been in over a century, but sewage in both the Cooper and Delaware rivers is still an issue. Combined sewer overflows pose a threat, especially when surges in rainfall cause stormwater to combine with sewage, discharging it into the water. The RiverGuides test the water regularly and paddling schedules are adjusted for spikes in bacteria levels.

On their last work day, the group visited Atsion Lake in the Pine Barrens to celebrate the summer. While swimming, there are no fears of contaminated waters from combined sewer overflows. As Beauchamps, Garcia and Carter-Lopes tackle each other in the water, they see what the Cooper and Delaware rivers could be one day. But for now, they go by boat. ◆

24 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024 the environmental justice issue

Clearing the air

Smog, VOCs and particulate matter are poisoning Philadelphian’s lungs. Experts say investment in public transit is key ➤

When many Philadelphians head out the door to traverse the city, they have an option in each pocket. In one are the keys to the car; in the other, a SEPTA card. And in their head, an often tortuous debate about which method of transportation would be safer, more affordable and more dependable.

But many may not realize that this decision is also the most crucial one they can make in helping to protect the lungs of city residents from harmful pollutants.

Air quality experts say this little-considered fact is the outcome of our particular moment in time in the battle against air pollution. Since the passage of the federal Clean Air Act in 1963, air quality has significantly improved by many measures across the country, including in Philadelphia. The law established standards on six common pollutants, including lead, smog and soot (also known as particulate matter) while spurring regulations to ratchet them down and creating public alert systems during unsafe conditions.

Yet, experts say, airborne threats persist. When a typical Philadelphian walks out the door, they’re still subject to inhaling harmful pollutants generated from as nearby as the factory next door, to as far away as wildfires on the other side of the continent. Given Philadelphia’s geographic location and big city status, its residents face more air pollution than many Americans: more than one in five children in the city has asthma, compared to only about one in 20 nationwide.

The solutions to the problem change depending on the pollutant. Philadelphia residents and local officials can do painfully little to curtail wildfires and coal-burning power plants thousands of miles upwind, which contribute to particulate matter pollution.

But among local sources, there’s an obvious place to focus, experts say.

BY KYLE BAGENSTOSE

“The single most important thing that every citizen can do to help alleviate air quality problems in our region is to get out of your car, to stop driving,” says Jane Clougherty, a professor of Environmental and Occupational Health at the Dornsife School of Public Health at Drexel University.

Where Past Meets Present

Philadelphia sits at a critical juncture in its battle with air pollution, says Russell Zerbo, an advocate for the environmental nonprofit Clean Air Council.

Under the Clean Air Act, regions like Philadelphia can be designed as “nonattainment” areas when their air quality fails to meet national standards. Zerbo says, historically, the program works like a tightening belt loop. Every five years, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is required to review the standards and often lowers the threshold considered safe for pollutants.

That sets off a cascading effect where regions like Philadelphia must submit plans to meet the new, lower standards.

The Delaware Valley is still on the treadmill of this perpetual game of catch-up. Currently, the region is in violation of the standard for smog, also called ozone, last established in 2015. Primarily a product of vehicles, industry and power plants, smog can burn the lungs and lead to a host of health issues such as asthma and emphysema.

But Philadelphia and some of its collar counties are also in danger of violating a new standard for particulate matter, sometimes called PM2.5, after the EPA announced this year its intentions to lower the safe limits by 25%. And Zerbo says particulate matter — tiny particles of harmful materials that typically come from combustion of fossil fuels and wood — are even more insidious than smog.

“PM2.5 eventually makes its way into

The single most important thing that every citizen can do to help alleviate air quality problems in our region is to get out of your car, to stop driving”

JANE CLOUGHERTY, Drexel University

26 GRIDPHILLY.COM JUNE 2024 the environmental justice issue

your bloodstream and brain, with all kinds of information correlating it to diseases and health outcomes,” Zerbo says. “It’s more broadly correlated to overall life expectancy.”

Zerbo is further concerned that the current regulatory safety net isn’t secure enough to protect Philadelphians from such threats. He notes the World Health Organization (WHO) already recommends a PM2.5 level nearly 50% lower than the EPA’s new proposed standard. Further, he worries that the plans that states and cities are required to submit to meet new air quality standards often aren’t robust enough to fully tackle the problem.

Clougherty sees gaps of her own. She’s particularly concerned about volatile organic compounds (VOCs), an entirely different class of air pollutants, several of which are “known carcinogens that are also associated with respiratory and cardiovascular illness,” Clougherty says.

“Because these pollutants — which primarily come from heavy industry but also tailpipe emissions — aren’t one of the EPA’s primary air pollutants, there’s not nearly the same level of monitoring,” Clougherty says. “That means they don’t trigger the orange and red air quality reports that would typically warn the public of danger.”

And, many VOCs emanate from local sources, which disproportionately impact local communities already susceptible to health harms.

“The other half of the risk equation is susceptibility. So neighborhoods where there are a lot of people with preexisting conditions due to other exposures — the elderly, children, lower-income communities — tend to be at higher risk,” Clougherty says. “One of the things that I look at a lot is chronic stress and how stress makes us more susceptible to all other exposures.”

Clearing The Air

James Garrow, communications director for the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, says the City is taking action to clean up the air. The department’s Air Management Services program has regularly updated its own local air management regulations (AMR) since the 1970s. Currently, they allow the City to regulate potential pollution sources such as construction dust, heavy fuel oil, paint spraying operations, leaky industrial pipes and harmful dry cleaning chemicals, Garrow says.

Such efforts have helped Philadelphia go from a city that, as recently as the 1990s, saw more than two months’ worth of days with “unhealthy” air quality each year, to one that now averages only a week or two. (The other 50 weeks of the year are split between about 30 weeks of “good” and 20 of “moderate” air quality.) And the City continues to create new regulations, he says.

“This past January, the City instituted a

new air management regulation, AMR-VI, that vastly expanded the number of toxic air pollutants that we track and measure and work towards limiting,” Garrow added. “This is one of, if not the most, stringent air toxic regulations in the country.”

Zerbo agrees AMR-VI is a good step forward in that it gives the City the authority to “aggregate the cancer risk from multiple air toxics coming from individual facilities.”

However, he cautions that air quality data also show troubling signs for the city. Between 2014 and 2022, Philadelphia made rapid strides in the number of “good” air quality days, from 132 to 281 a year. But those numbers have since fallen backwards to the low 200s, and the 2023 wildfires gave Philadelphia its highest number of unhealthy air quality days since 2008.

Garrow says that, while the City’s regulations are well-equipped to address “stationary” sources of pollution, they do not have legal authority to regulate mobile sources such as cars, trucks and construction vehicles. That falls to the EPA, which is indeed pursuing new regulations on tailpipe emissions.

But that position doesn’t satisfy Zerbo, who says the City and State can be doing more to invest in SEPTA and to address air pollution by cutting down the number of vehicles on the road.

“The easiest and clearest solution for me is more funding for public transit,” Zerbo says.

Clougherty agrees, and also encourages people to walk and bike for short trips, adding that cutting down on vehicle pollution will reduce the hidden dangers of VOCs in the city, as well as smog and PM2.5.

But with public transit funding decisions largely out of control of the public, Clougherty is also studying even more direct action. She is currently researching communities in New York State, whose public health appears to be faring better than expected given their air quality, to see if she can determine common variables helping to inoculate them from the danger. “There are a huge range of things we’re looking at … availability of green space, playgrounds where kids exercise, schoolsbased interventions,” Clougherty says.

The research could result in a recipe to apply here in Philadelphia, potentially improving city health at the neighborhood level.

As Clougherty says: “We’re trying to flip our model from thinking about just stressors to thinking about resilience strategies.”

JUNE 2024 GRIDPHILLY.COM 27 PHOTOS BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

◆

Public health scholar Jane Clougherty (opposite page) is concerned that some dangerous pollutants, such as volatile organic compounds, are not even sufficiently monitored to warn the public.

A sinking feeling

Logan Triangle’s past leaves neighbors skeptical of new development push ➤ BY

KYLE BAGENSTOSE

Last fall, after Philadelphia announced the release of a request for proposal to develop one of the most notoriously blighted areas of the city, the Logan Triangle, a bevy of reporters called up Charlene Samuels, chairperson for the Logan Civic Association, to get community perspective.

With more than a hint of exasperation in her voice, she told them all a version of the same thing: “Just sit and wait and see.”

And also: “Hope and pray.”

That’s what it’s come down to in Logan, where the wrongs of a century past and decades of unkept promises have left residents skeptical anything good will come of the 40ish-acre eyesore, which drags down the name of a neighborhood many are otherwise proud to live in.