‰

TIME AND PLACE

Prof. David Schiff’s musical journey winds through the vineyard with Susan Sokol-Blosser ’67 and around the track with Steve Prefontaine.

Prof. David Schiff’s musical journey winds through the vineyard with Susan Sokol-Blosser ’67 and around the track with Steve Prefontaine.

Your steadfast service to the college and the alumni community is a gift. Reed deeply appreciates your time and many talents, and it is an honor and a pleasure to work with you. Thank you.

Alumni Board

alea adigweme ’06 PAST PRESIDENT

Michael Axley ’89 ALUMNI TRUSTEE

David Baxter ’87 PRESIDENT

Carla Beam ’76 ALUMNI TRUSTEE

Sirius Bonner ’05

Grant Burgess ’13

Maya Campbell ’15

Jennifer Delfino ’05

Ian Fisher ’07

Carmen García Durazo ’11

Liz Gilkey ’01

Katie Halloran ’15

Ashlin Hatch ’17

Avigail Hurvitz-Prinz ’05

Valentina Jin-Trowbridge ’11

Gray Karpel ’08

Christine Lewis ’07 ALUMNI TRUSTEE

Eve Lyons ’95

Peter Miller ’06

Govind Nair ’83

Laura Nelson ’13

Haley Parra-Cain ’17

Dylan Rivera ’95 VICE PRESIDENT

Lisa Saldana ’94 ALUMNI TRUSTEE

Laramie Silber ’13

Marjorie Skinner ’01

Andrei Stephens ’08 SECRETARY

Alumni Fundraising for Reed Steering Committee

Keith Allen ’83

David Buckler ’85

Doug Fenner ’ 71

Jay Hubert ’66

Advait Jukar ’11

Kyndra Homuth Kennedy ’04 CO-CHAIR

Charli Krause ’09

Katherine Lefever ’07 CO-CHAIR

Christine Lewis ’07

Jan Liss ’ 74

Kathryn Mapps ’86

Dylan Rivera ’95

Andrew Schpak ’01

Lara Simonetti ’20

Anne Steele ’ 70

Andrei Stephens ’08

Carlie Stolz ’13

Ray Wells ’94

Marcia Yaross ’ 73

Janet Youngblood ’68

Lilia Raquel Rosas ’94

alumni.reed.edu/volunteer

Chapter Leadership Council

Emily Allen ’19

Wayne Clayton ’82

Johanna Colgrove ’92 CHAIR

Justin Corban ’04

Dietrich Dehlinger ’01

Gray Karpel ’08

Andrew Korson ’04

Eve Lyons ’95

Peter Miller ’06

James Quinn ’83

Julia Selker ’15

Andrei Stephens ’08

Carlie Stolz ’13

Foster-Scholz Club Committee Chair

Barbara West ’64

Reed Career Alliance Chairs

Matt Giger ’89

Liz Gilkey ’01

Govind Nair '83

Committee for Young Alumni Chair

Laramie Silber ’13

26 Class Notes

40 Object of Study

WHA T REED STUDENTS ARE LOOKING AT IN CLASS In the Zebrafish Tank

Reed is an extraordinary place, and as president, I want to make sure that everyone in the Reed community keeps an eye on the future as we tend and care for our college, so that it may remain strong for generations to come. I want to highlight what I see as the hopes and ambitions of a shared vision for Reed.

First and foremost, we will continue to honor Reed as the distinctive college it is—a haven for intellectual and creative exploration that prepares our students to address big and important problems that aren’t easily or quickly solved, including justice, peace, sustainability, and human welfare.

We believe in the value of a well-rounded liberal arts education and in relationships forged in classrooms, studios, laboratories, and serendipitous connections. We will continue to recruit and support talented students, faculty, and staff, who can thrive together on our campus.

In keeping with our commitment to anti-racism, I want to position Reed as the most multiracial, multicultural, intellectual college in the world. I want to ensure that a Reed education is accessible to students from a diversity of backgrounds, and that every student finds a sense of belonging on campus.

Most of all, I want to make sure our students come away from Reed with knowledge, skills, and abilities that will serve them throughout their lifetimes. That means offering a variety of experiences that keep students engaged, and finding new ways for Reedies to make an impact now and into the future. I also want our graduates to keep Reed in their hearts and find ways to stay engaged with the life of the college. Involved alumni make our community stronger and are vital to sustaining Reed’s mission.

As this issue makes abundantly clear, important work is taking place at Reed all the time, and that work extends beyond our campus. Whether running for Congress and succeeding against the odds, as Marie Gluesenkamp Perez ’12 has done, or developing a breakthrough cancer-fighting drug, as has Vollum Award recipient Kevan Shokat ’86, the stories of our alumni are inspirational.

For 115 years, Reed has persisted and risen to a multitude of challenges. That is because of the amazing people who have been drawn here and who hold the college to a high set of standards. Looking toward the next 115 years, I am confident that Reedies—and the world—will benefit from the bright lights of curiosity, inquiry, and love of learning that this college fosters. We are small, yet mighty. Long live Reed!

www.reed.edu/reed-magazine

3203 SE Woodstock Boulevard, Portland, Oregon 97202 503-777-7591

Volume 102, No. 2

REED MAGAZINE EDITOR

Katie Pelletier ’03 503-777-7727 pelletic@reed.edu

WRITER / IN MEMORIAM EDITOR

Randall S. Barton 503-517-5544 bartonr@reed.edu

WRITER/EDITOR

Rebecca Jacobson 503-517-7735 rjacobson@reed.edu

ART DIRECTOR Tom Humphrey tom.humphrey@reed.edu

CLASS NOTES EDITOR

Joanne Hossack ’82 joanne@reed.edu

REEDIANA EDITOR

Robin Tovey ’97 reed.magazine@reed.edu

GRAMMATICAL KAPELLMEISTER

Virginia O. Hancock ’62

REED COLLEGE RELATIONS

VICE PRESIDENT, COLLEGE RELATIONS AND PLANNING

Hugh Porter

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, COMMUNICATIONS & PUBLIC AFFAIRS

Sheena McFarland

Reed College is an institution of higher education in the liberal arts and sciences devoted to the intrinsic value of intellectual pursuit and governed by the highest standards of scholarly practice, critical thought, and creativity.

Reed Magazine provides news of interest to the Reed community. Views expressed in the magazine belong to their authors and do not necessarily represent officers, trustees, faculty, alumni, students, administrators, or anyone else at Reed, all of whom are eminently capable of articulating their own beliefs.

Reed Magazine (ISSN 0895-8564) is published quarterly by the Office of Public Affairs at Reed College. Periodicals postage paid at Portland, Oregon.

Postmaster: Send address changes to Reed Magazine 3203 SE Woodstock Blvd. Portland OR 97202-8138

Audrey Bilger President of Reed

We believe in the value of a well-rounded liberal arts education and in relationships forged in classrooms, studios, laboratories, and serendipitous connections.

We’re planning to give Reed Magazine a post-pandemic update. Will it be a redesign? Maybe. A refresh? We’re still planning. But, we want to hear from you before we touch anything. The magazine is a place we meet as a community, and it’s important to us that you are a part of this process.

In the coming weeks, you will receive a survey in your email inbox, and I hope you will take a moment to fill it out. As part of the survey you can indicate if you would like to be contacted with more questions or would like to be part of an alumni focus group. If you need a paper copy of the survey, please let us know.

We will take a brief hiatus in December while we’re under construction. You’ll receive a fall issue, and then we’ll be back in your mailboxes in spring 2024.

—KATIE PELLETIER ’03, EDITOR

The third floor of the library has been transformed into an academic space, thanks to a $1 million grant from the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust. Expanded by more than 4,000 feet to create a large classroom, group work spaces, and a suite of seven faculty offices, the renovation unites the mathematics and statistics department with the computer science department, which reflects the connections the programs share. Computer science became its own major in 2017 but maintains a strong emphasis on mathematics, and many students pursue an interdisciplinary computer science–mathematics major. Statistics, meanwhile, remains housed within the math department, but in recent years has seen faculty growth and a rise in student interest.

According to Prof . Angélica Osorno , chair of the mathematics and statistics department, the proximity offers a slew of benefits and opportunities. “This is important in terms of administration of the departments, but also in terms of collaboration, both in research and teaching,” Osorno says. “It’s very easy for me if I’m working on a research problem and there’s a question one of my colleagues might be able to answer, I just go down the hall. Or if I’m having a meeting with one of my thesis students and we’re dealing with something related to statistics, I just go to the office of my statistician colleague.”

Osorno emphasizes that the new common spaces also facilitate vital connection and collaboration among students. “We have math students talking to CS students, stats students talking to CS students, and so on,” she says. She adds that in the past, visiting faculty had to be placed elsewhere on campus because of space constraints, which impeded communication and led to a sense of isolation.

“We’re a pretty collegial group of people, and we like being together,” Osorno says. “We’re constantly having conversations, so it’s really valuable to all be on the same floor.”

A DESK OF ONE’S OWN: Reed’s thesis desk lottery returned in March, the first time the tradition had taken place since before the pandemic. (Here, Sofie Larsen-Teskey ’23 schleps her books to her new desk.) The event marked the completion of renovations to the library’s south wing, which received new and refurbished carrels—following architect Harry Weese’s original 1963 design—as well as a major seismic upgrade. Other improvements include new windows, new compact shelving, and new study spaces, as well as an accessible room for students with accommodation needs.

If it were up to Elizabeth Drumm, John and Elizabeth Yeon Professor of Spanish and Humanities, Spanish author Ramón del Valle-Inclán would be as widely read as T. S. Eliot, Virginia Woolf, and James Joyce. Like those giants, Valle-Inclán was a modernist innovator. He published across disparate genres—plays, poetry, novels, art criticism, essays—and even created his own, the esperpento, which distorts reality to emphasize the grotesque.

But outside Spain, Valle-Inclán is little known. He died in 1936, the year the Spanish Civil War began, and his work was censored under Francisco Franco, who ruled until 1975.

“[Franco] really shut down a lot of the literary flow in and out of Spain,” Drumm says. “But the issue of translation is also part of it. There are anthologies of modernism [that] don’t include Spanish authors at all.”

Drumm’s efforts to make ValleInclán part of the conversation have gotten a notable boost: this year she received a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities to support her work on a translation of and critical introduction to La media noche: Visión estelar de un momento de guerra (Midnight: Astral Vision of a Moment of War). The text, written during World War I after Valle-Inclán’s

trip to the western front on the invitation of the French government, is an attempt to express simultaneity. “How do you represent temporal experience in literature?” Drumm asks. “ValleInclán does it through this view, as he says, from the stars. He imagines himself above, looking down at the whole front and describing what happens simultaneously over the course of one night. It’s fascinating.”

For Valle-Inclán, this perspective isn’t mere formal innovation—it’s also a reflection of his occult fascinations. Around the same time as La media noche, Valle-Inclán published La lámpara maravillosa (The Lamp of Marvels), an aesthetic treatise that Drumm describes as “a compendium of occult thought.” Tied to the theosophical movement of the time, the dense tome synthesizes traditions that include gnosticism, kabbalah, alchemy, Spanish mysticism, and the hermetic tradition. If La lámpara maravillosa is theory, Drumm says, La media noche is an attempt to put ideas into practice.

Drumm adds that a former advisee of hers, Susana Mizrahi ’15 , wrote her thesis about La media noche: “Advising Susana’s thesis was instrumental in my thinking about the text and conceptualization of the translation project.” —REBECCA JACOBSON

For years, a protein mutation commonly found in cancer cells was thought to be “undruggable,” a term coined to describe a protein that will not interact with medications. Scientists have been trying to target the protein, known as KRAS, since the 1980s. But in 2013, researchers at UC San Francisco developed a way of flagging the mutated proteins for targeted attacks. Led by Kevan Shokat ’86, UCSF’s Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, the discovery paved the way for a new class of cancer drugs that could save lives and may one day even lead to a cure.

“It’s a really great experience to have so much information out there, but not seeing the exact path to the drug, and then just try things, shut it down, try another thing, shut it down, and then get lucky along the way,” says Shokat, this year’s recipient of the Vollum Award for Distinguished

The award, created by the college as a tribute to Howard Vollum ’36, recognizes the exceptional achievement of a member of the scientific and technical community of the Northwest. Endowed in 1975 by a grant from the Millicent Foundation, it is now part of the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust.

This has been a big year for Shokat. He was also awarded the Sjöberg Prize in cancer research by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which recognized him as “the first person to succeed in blocking one of the mutated proteins that cause most cancer cases.” They added, “This is a huge scientific breakthrough that is bringing hope to people who are critically ill with lung cancer.”

Two KRAS drugs have received FDA approval so far: sotorasib and adagrasib. After first-line therapies, the drugs are used to target a KRAS mutation that occurs in about a third of lung cancer patients. (Trials are currently underway to explore prescribing it earlier.) Because they work by targeting a single mutant protein and halting its communication, the new drugs are more precise than treatments like chemotherapy, which affects

noncancerous cells as well as the tumor. “In patients who respond well, it can make a huge difference. For the approximately 30 percent of patients who do,” Shokat says, “they experience rapid tumor shrinkage.”

As new therapies targeting KRAS mutations evolve, Shokat hopes response rates will improve. “What’s exciting is a lot of companies have made their own drugs like this, and they’re combining it with other drugs that they’ve made,” he says. “So I think this is just the beginning of the response and benefit we can see in patients.”

Shokat first fell in love with scientific research at Reed. He’d attended a high school without a robust science curriculum, so when he arrived at the college, he recalls, “most everything in my science classes was new to me.” His fascination was immediate. “I just loved the deep dive of it,” he says. “And I always tell people who are thinking about Reed, to me, an intro class there is just so different than anywhere else, because all the professors taught you as if you were going to be getting a PhD in that topic.”

One of these professors was Phyllis Kosen [chemistry 1981–83]. Shokat

remembers attending her office hours in the Reed coffee shop with excitement. “She was a biochemist, and so I got to start thinking— even though it was intro chemistry—about proteins, and that was really, really great,” he says. It was under the tutelage of beloved chemistry professor Thomas Dunne [1963–95] that Shokat came to appreciate the logic and clarity of chemistry.

Receiving the Vollum award for work in a field he first encountered at Reed was cause for celebration. For Shokat, it’s also a full-circle moment. Reed wasn’t just an academic home for him: it’s where he met his wife, Trustee Deborah Kamali ’85, and it’s where his three children—Kasra Shokat ’14, Mitra Shokat ’18, and Leila Shokat ’21—attended college. He draws a straight line from his time at Reed to his experiences in his lab at UCSF. “I tell my students now: I’ve been running a lab for 25, 28 years, and every day, coming in is basically the same as when I went into lab to do my Reed thesis, or when I went into lab to do my PhD, because little things change, but just getting to think about molecules all the time has been so, so fun,” he says. —MEGAN

BURBANK

BURBANK

Congratulations, graduates! As you leave the Reed campus and start on all life’s journeys, know that Reed never leaves you. You are and always will be a Reedie. And as such, you have a global network of alumni to connect with. We in the alumni relations office are here to help facilitate that. We work to keep you connected to your classmates and all who came before and will come after you. So feel free to reach out. Email alumni@reed.edu or visit alumni.reed.edu for more information.

As I considered what to share with you in this issue’s Advocates of the Griffin, I started thinking about all the alumni who engaged with Reed throughout the past school year; I was struck first by the passion each has for the college. The dedication to ensuring that a Reed education remains available to current and future students is foremost. A close second is a strong belief that Reedies should remain connected to the college and one another.

Alumni interactions happen every day, whether through the alumni relations office, through the Center for Life Beyond Reed, or under the radar, such as by responding to a LinkedIn message. Whether an alum is engaging for the first time or for more times than they can count, the effort makes a meaningful impact on our Reed community.

I am honored to thank all the volunteers who dedicate their time and talent to Reed. Your hard work is often silent, and your recognition may be limited within these pages,

but our gratitude is not. A huge thanks to all of the alumni volunteers: alumni board, Alumni Fundraising for Reed, alumni trustees, career coaches, alumni chapters, Committee for Young Alumni, Diversity and Inclusion Committee, Foster-Scholz Club, student mentors, Paideia, Pathfinders, Reed Career Alliance, Reunions, summer internship hosts, and the myriad others who serve the Reedie community officially and unofficially.

The Babson Society Outstanding Volunteer Award, established in honor of Jean McCall Babson ’42 , recognizes outstanding volunteer efforts by Reed alums. The alumni board nominating committee bestows the Babson Award each year. This year’s awardee is Govind Nair ’83. Govind is honored for his longstanding commitment to Reed and for being the driving force behind the Reed Career Alliance.

The Distinguished Service Award, established in 1975, recognizes a member of the Foster-Scholz Club who has made significant contributions to their community and/or the college. The Foster-Scholz Steering Committee presents the DSA during the Foster-Scholz Luncheon at Reunions each year. This year, the committee recognizes Mark McLean ’70 and Eduardo Ochoa ’73 for their decades of involvement in Reed College volunteer opportunities and service to their communities.

There are many ways to volunteer your time and expertise to serve the Reed alumni community. Which one is right for you? Email alumni@reed.edu, and a staff member will contact you to find the perfect fit.

While there are great resources if you know exactly what career you want, the Committee for Young Alumni’s Pathfinders Initiative is more your jam if you have a broad area of interest and want to learn about opportunities within it that you may not have even imagined!

Are you a new(er) graduate from Reed or just contemplating or starting in a new field and want to connect with an alumni Pathfinder volunteer? Are you interested in being a Pathfinder—offering recent experience and perspective in a constantly changing world? Email alumni@reed.edu or visit alumni.reed.edu. We’d love to connect with you!

OCTOBER 13–15, 2023

Join Reedies at Camp Westwind—a magical weekend on the Oregon coast filled with laughter, bonfires, lots of sand, and plenty of relaxing. Escape cell service (and your regularly scheduled plans) at this family-friendly weekend led by alumni volunteers.

Space is limited and will sell out! Registration is now open.

Far above, the hawk is circling.

All it takes is eight notes—eight notes from the solo violin—and we’re soaring high above the mountains, riding the waves of the wind.

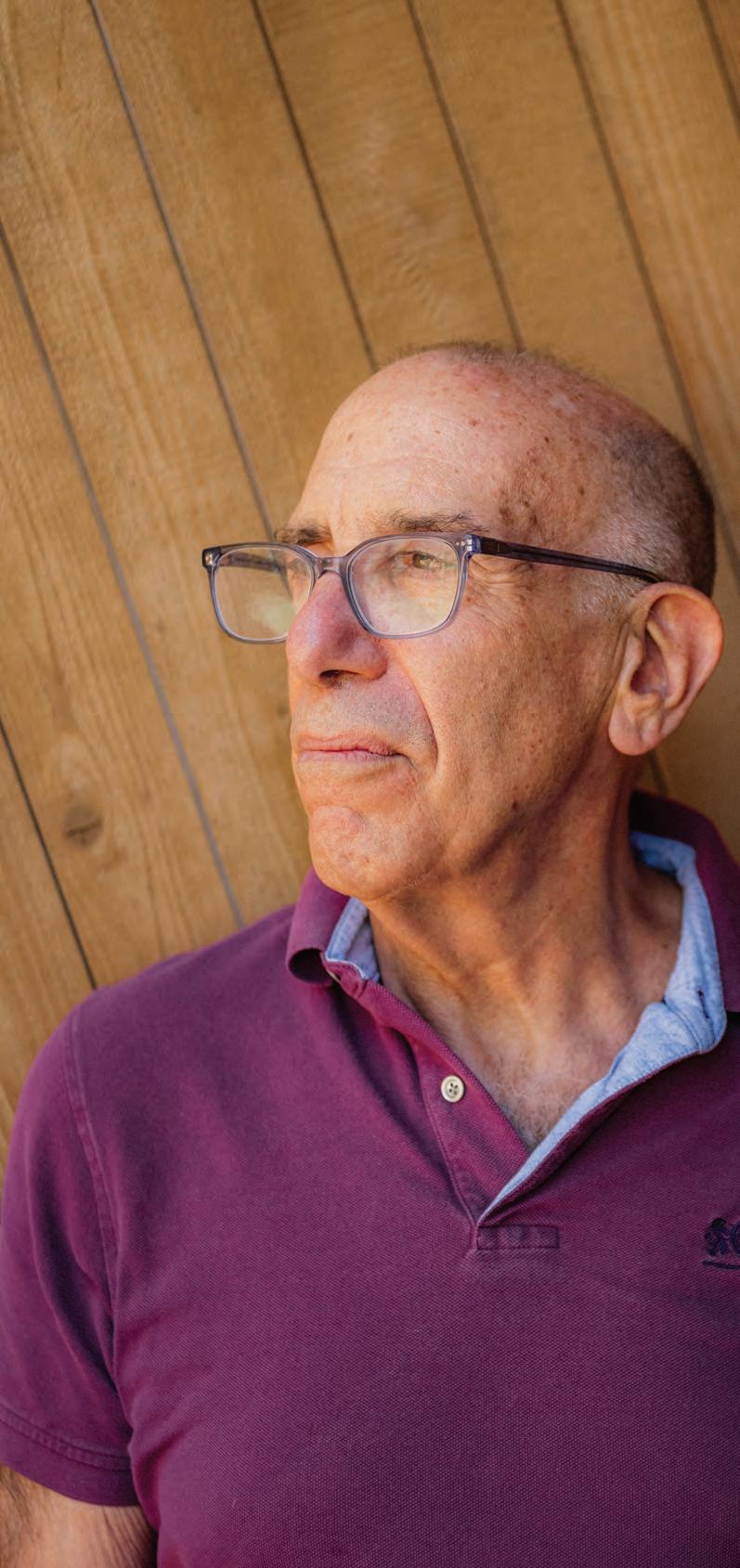

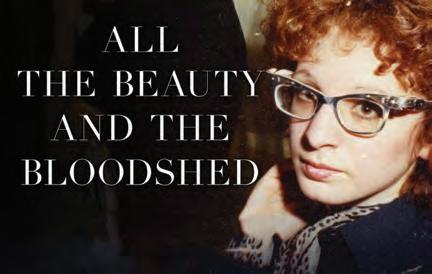

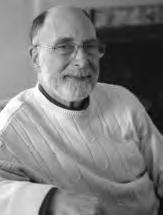

In Vineyard Rhythms, a violin concerto inspired by the lush landscape of Yamhill County, Professor Emeritus David Schiff [music 1980–2019] demonstrates his mastery of shifting perspective.

The piece begins by looking down at the land from the perspective of a hawk calling to its avian companions dancing in the sky. It then drops to the land, invoking the richness of the earth that feeds the vines as they ripen and burst with energy. It finishes with a joyous tribute to the bubbling transformation of harvest.

Just as the piece serves as a metaphor for the cycles of life, it also serves as a window into the ever-evolving career of David Schiff, a career forged by the liberal arts and tempered by the intellectual atmosphere of Reed. From Gustav Holst to George Gershwin, from Duke Ellington to Frank Zappa, Schiff’s influences run far and deep, surfacing in unexpected places.

Schiff retired from teaching a few years ago, but he’s as busy as ever. In addition to Vineyard Rhythms, commissioned by Oregon

With ever-evolving subjects and inspiration, Prof. David Schiff’s musical career plays on.

wine industry pioneer Susan Sokol-Blosser MAT ’67 in honor of her mother, he also recently composed Prefontaine, a symphony celebrating the enduring influence of Oregon running legend Steve Prefontaine, whose brilliant career was cut short by a fatal car accident in 1975.

Taken together, these pieces, which both premiered last summer, reveal how Schiff brings profound curiosity, a creative and inventive spirit, an appreciation of the gifts of others, and a drive to connect with the audience in a profound way.

And that he has a lot of fun.

David Schiff’s talents and accomplishments are nothing short of prodigious. Well-known for his compositions for chamber and symphonic music, he’s fluent in the languages of jazz, opera, klezmer, and more. He’s also written widely, including books on Duke Ellington, George Gershwin, and Elliott Carter.

Yet he didn’t come to a musical career readily. Born in 1945 and growing up in the New York City area, he played piano from a young age and listened to a diverse collection of music, taking in the sights and sounds of Broadway. He majored in English literature at Columbia University (where Susan Sontag and Edward Said taught his freshman year core course), studied on a fellowship at Cambridge, and intended to become an English professor.

In 1968, to avoid being drafted, he took a crash summer course at NYU and then spent a year teaching junior high in the South Bronx. “On several occasions at Reed faculty meetings, I’d make a statement that everything I ever needed to know about teaching I learned that year,” he laughs.

Back at Columbia, he was approaching 30 and well on his way toward a PhD in Victorian literature (intending to write his dissertation on William Thackeray), when a visit to an otherwise unmemorable therapist provided the lightbulb moment. “I asked, ‘Why is it that no one believes I’m a musician?’ and the therapist said, ‘Why should they?” Schiff immediately applied for summer school at the Manhattan School of Music and found his new path. To pay his tuition, he taught in the Manhattan School’s

humanities program, a combination he calls “good preparation for Reed.”

Always attracted to nature’s beauty, Schiff found Oregon’s coastlines, mountains, and high deserts significant draws when he came to Reed in 1980 to teach music theory and composition. He soon branched out to teach courses in the history of jazz, the music of Duke Ellington, American musical theatre, and a course called Music since 1960 that featured a range of genres from avant-garde to rap.

“David brought a deep knowledge of music—and new music—to Reed,” says his colleague Prof. Virginia Hancock [music 1990–2016], whose career paralleled Schiff’s at Reed. “He was a very devoted teacher who took enormous trouble over his students. He was tough. But they learned he cared for them.”

Schiff conducted the Reed orchestra for many years and was also instrumental in founding two long-standing Reed traditions: RAW and ROMP.

RAW (Reed Arts Weekend) was the brainchild of a group of young professors who were dismayed at the lack of visiting performers on campus in the 1980s and wanted to provide a venue. Eventually, RAW could no longer be contained in a single weekend and became Reed Arts Week, though it evolved away from the performing arts and focused more on studio arts.

Schiff came up with the idea of ROMP (Reediana Omnibus Musica Philosopha) after participating in the Bard College Music Festival, an annual event involving both performers and scholars. From 1999 to 2016, ROMP enlivened the campus with concerts and talks on a variety of subjects.

Schiff remains profoundly grateful for Reed’s support for his work as a composer. He also relished the opportunity to work with such a range of committed students. “I never had to motivate my students,” he says. “They arrived motivated. When you presented them with a challenge, they would do it.”

Many of his students would only discover their deep connection to music after matriculating, and he believes Reed was the perfect place for those students. “I could take a student like that and move them along,” he says, “I loved thinking about how to help students find their voice.”

An appreciation of the value of working with others is one of the key insights that has driven Schiff’s career. “When I think about life as a composer—I said this to students many times—aside from the pleasure of getting the notes on the page, you get to have your music played by these wonderful musicians who bring everything they have to your music and they elevate it.”

It’s no surprise that in addition to his work with students at Reed, Schiff never lost sight of his other vocation: composing.

Susan Sokol Blosser MAT ’67 is a powerhouse in her own right. After getting her bachelor’s degree in history at Stanford, she earned her MAT from Reed and went on to become a pioneer of the Oregon wine industry. She drove the tractor, pruned the vines, and built the vineyard into a leader in sustainable agriculture by limiting pesticides, installing solar power, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Along the way, she raised two kids and wrote four books.

“I think of the liberal arts as education for life,” she says. “I’m living proof of that.” She’s such a firm believer in the value of a Reed education that she recently joined the college’s board of trustees.

She’s long held a belief in the power of music to transform lives. In 2011, she founded the Yamhill Enrichment Society (YES), which focuses on literacy and music enrichment for youth in Yamhill County. As part of YES, Sokol Blosser launched the Junior Orchestra of Yamhill County (JOY) in 2017. Its audacious goal is to teach every elementary school student in the county to play the violin. She believes “playing the violin is like a full-body workout for the brain.”

Sokol Blosser had thought about setting her vineyard to music for years before asking Schiff to compose Vineyard Rhythms as a tribute to her late mother, Phyllis Feingold, who was an accomplished classical violinist and member of the Chicago Women’s Symphony in the 1920s. Feingold might have continued to work as a professional musician in a more enlightened era. But in her time, she was unable to balance the demands of a musical career with being a wife and a mother. (Sokol Blosser is currently working on a novel-like memoir of her mother with the working title The Choices We Make.)

In addition to her mother, Sokol Blosser wanted to honor the vineyard where she has lived and worked for over 50 years. “I wanted to capture in music its beauty, with its annual passage through growth, fruitfulness, dormancy, and rebirth,” she says. “In essence, I wanted to put the vineyard to music.”

Neither she nor Schiff was aware of their shared connection to Reed before the project began but found it a delightful coincidence. Schiff found another surprise in the commission. “Having the vineyard as a destination got us through COVID,” he says, remembering the many trips he and his wife, Judy, made throughout the changing seasons to experience the landscape and walk among the rows of vines that straggle across the hills like staves of music on a page.

On an early visit, as red-tailed hawks circled in the sky, Sokol Blosser pointed out their nest high in a tree. That inspired the first movement, “Hawk,” where a vivid eight-note theme on the violin loops and soars over the winter landscape like a raptor on the wing, circling its dormant domain, awaiting the arrival of spring.

In the second movement, “Gaia,” the music travels from the earth up, as Schiff weaves together ripening harmonies to conjure the growth of the vines, summoning forth their power in the stillness, as spring warms to summer and the sound grows stronger and more confident. The final movement, “Harvest,” pulses with jazzy, triumphant intensity as the vineyard workers hustle to gather the lush bounty into the vats.

Schiff says the piece benefitted from Sokol Blosser’s own writing about the vineyard, which she sent him during the process, but she wasn’t prescriptive, choosing to let him create his own musical reflection of the land. She didn’t hear the piece until it was finished. “I was thrilled with the final product,” Sokol Blosser says, especially the opening notes of Chamber Music Northwest co–artistic director Soovin Kim on solo violin.

Conducted by Francesco Lecce-Chong, the piece premiered in July 2022 with a performance at Chamber Music Northwest, with which Schiff has had a fruitful relationship, writing more than 20 pieces for them since 1982. A second performance occurred at the vineyard as part of a fundraising dinner. That day was beastly hot— Schiff remembers that the thermometer in his car read 114 degrees— so the performance had to be moved inside to the winery’s cellar. Characteristically, rather than being dismayed at the last-minute

change in setting, Schiff was delighted by the added resonance generated by the huge metal wine barrels.

It’s another example of a career that has embraced creativity, opportunity, and being in the right place at the right time. He remembers that when he was five years old, his family bought a recording of Debussy’s La Mer. “It quickly became my favorite piece of music, then and forever,” Schiff says. His family spent their summers at the beach, and it was then that he first realized “the idea that music could take you someplace.”

From the very first notes of Prefontaine, Schiff makes it clear that we’re not going to sit still.

It begins with a bolt from the blue, a burst of piccolos, violins, and timpani that explodes onstage like a starter’s pistol. Amid the eerie aftershock, a ricochet of percussion builds to another explosion. And another. Then,

wafting above the chaos, a lone flügelhorn takes up a lovely, lilting theme, soaring impossibly high, like an archer’s arrow flying into the night and disappearing among the stars.

Like Prefontaine, we are embarking on an odyssey.

The piece was commissioned by the Eugene Symphony for the 2022 World Athletics Championships (held in Eugene) to honor Oregon’s most famous runner. Steve Prefontaine, known as Pre, earned seven NCAA titles for the University of Oregon. His standout performance at the 1972 Olympic Trials 5K before a sold-out crowd at Hayward Field helped fuel the nation’s running craze and catapulted him to fame. Over the next few years, his scrappy, brash identity and will to win made him an international legend until he was killed in a car accident at the age of 24.

Scott Freck, executive director of the Eugene Symphony, says Schiff was top of his list to commemorate Prefontaine. “He has a

dynamism that brings a lot of energy to the orchestra,” Freck says. “He’s obviously a brilliant guy and was an absolute joy to work with.”

Schiff approached the piece with an open mind and a researcher’s zeal. He traveled to the working-class town of Coos Bay, met with sportswriter Curtis Anderson, and talked to people who had known Prefontaine. Under the tutelage of Linda Prefontaine, Steve’s sister and “the keeper of the flame,” Schiff says, he and a team from the Eugene Symphony explored the rugged coastal stomping ground where Prefontaine trained to push himself harder, faster, farther.

The first movement captures the dramatic landscape on the drive from Eugene, through the Cascade Mountains to the Oregon coast. Schiff wrote it as a passacaglia, a classical form that features a repeating bass line known as an ostinato. But he turned the pattern upside down and put the ostinato up high. At the same time, he reversed the arrow of time. He begins the musical journey at the site in Eugene known as Pre’s Rock, where people have never stopped leaving memorial tributes, then traces the way back to Coos Bay, where the runner was born and raised.

For the climactic third movement, named “5K,” Schiff traced each lap of Pre’s most famous race, matching his stride second by second with music that challenged the performers to keep up just as Pre’s effort challenged his competitors. Schiff organized the movement as a sequence of 12 fugues to represent the 12 laps in a 5,000-meter race. During the performance in Eugene, also conducted by LecceChong, a stopwatch on the screen kept time to match Prefontaine’s best timings. Each fugue was scored for a different group of players, beginning with small ensembles, and gradually building to include the entire orchestra.

As Schiff delved into the project, he found himself returning time and again to one of Prefontaine’s unforgettable quotes. “To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice your gift.”

“I feel that everyone has a gift and the challenge of being true to that gift is what shapes our lives,” Schiff says. “That’s what I wanted the piece to be about.”

Shape-shifter. Time traveler. As he settles into a remarkable phase of a remarkable career, Schiff and his many fans can only wonder, where will music take him next?

The Eugene Symphony brings back Prefontaine for an encore performance on October 19, 2023. It will be recorded and released in 2024.

Oregon’s most famous runner, Steve Prefontaine, in 1972. Susan Sokol Blosser ’67 with Prof. David Schiff at the Sokol Blosser vineyard in Yamhill County, Oregon. PHOTO BY TONY DUFFY /ALLSPORT

Marie Gluesenkamp Perez ’12 was on the verge of a very big decision.

It was February 2022. The year before, Republican Joe Kent had announced his campaign for Congress for Washington’s Third District over the incumbent, the more moderate, Jaime Herrera Beutler, who had voted to impeach Donald Trump. Trump had endorsed Kent in September. Gluesenkamp Perez was charged up by Kent’s extremist politics; she has called him a “fascist” and a “white nationalist, Nazi sympathizer” online. She was considering running against him.

Her interest in public office was not without precedent. In addition to co-owning an auto repair and machine shop with her husband, Dean Gluesenkamp, she had been involved in her community and active in local politics since 2016, when she ran for, and lost, a seat on the Skamania County Board of Commissioners. Undeterred by the loss, she started working on the Underwood Conservation District board in 2018.

When the idea of running for Congress began to bloom, she called Hannah Love ’12 , a political strategist and her former housemate, to ask her for advice. Love, wanting to be a true friend, tried to deter Gluesenkamp Perez at first. “I think you can do it, if anyone can do it,” Love remembers saying, but she cautioned against long hours and the potential of losing.

Perez ’12 led a grassroots congressional campaign and surprised the nation when she flipped a district.PHOTO BY MASON TRICA

Making the choice took serious consideration. Gluesenkamp Perez cared deeply for Washington, where her family has deep roots going back generations, and where she’d spent childhood summers playing in the forest. But the true inflection point for her came during a calm moment, while she was nursing her son, Ciro, in the home she and her husband built from the ground up.

“That was the point where I was like, oh, I think I need to do this,” she said.

And she did. In what pundits later called the biggest upset in the 2022 election, she flipped her district to defeat Joe Kent through a grassroots campaign, with no financing from the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee— despite a two percent predicted chance of winning. Being a political underdog came with a kind of freedom, said Gluesenkamp Perez: “There was not an alternative to being who I am.”

On a cool day in April 2023, the cherry blossom trees surrounding the Battle Ground Community Center in southern Washington State are out in full force: their flowering branches bob in the breeze, promising spring. There’s only half a second to admire them, though; I’m hurrying through the door behind Congresswoman Gluesenkamp Perez and her staffers.

Inside, more than 70 people from all over the state mill about before settling into seated rows. They’re aged young, old, and infant. They wear suits, suspenders, jeans, espadrilles, and baseball caps. And they bear titles as diverse as flower farmer, director of governmental affairs at the Washington State Potato Commission, representative from the Washington ATV Association, director of the Anti-Hunger & Nutrition Coalition, and scientific policy advisor for the Washington State Conservation Commission.

Yet all these people have something in common: they’ll each spend just two minutes talking to Glusenkamp Perez. In their allotted time, they’ll share their hopes and asks for the 2023 Farm Bill, a gigantic, complex piece of legislation that passes once every five years and encompasses such wideranging topics as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, crop insurance, land conservation, forestry

services, commodities pricing, federal loan programs, and rural development. It’s a big deal. A podium stands in the center of the room, waiting for people to approach.

Facing them at the center of a folding table, Gluesenkamp Perez sits flanked by staffers with computers out ready to take notes and stacks of business cards to hand out after the session.

Her bright green pin pops out to designate her as a member of Congress. Otherwise, she’s unadorned. Wearing a blue oxford shirt with the sleeves rolled up, jeans, and Blundstone boots, she looks casual enough that she could go from the district

that draws people in. Maybe it’s her sincerity, or the fact that she’s funny, or that her general approach to life is pretty punk. She doesn’t boast a massive Twitter following, and she hasn’t pulled flashy stunts like attending the Met Gala like some other representatives (at least not yet). But it feels like she’s a local celebrity. During my day with the congresswoman in mid-April, I felt like I was buzzing. At all of our stops, she was excited to see people. But they were really excited to see her.

She urged people not to use any of their precious two minutes at the listening session on niceties, but most couldn’t resist. Joe

office to a timber conference. Likely that’s because, sometimes, she does, in addition to petting cows at creameries and donning a hood to watch students learn to weld (all of which you can witness on her Twitter feed). When not in Washington, D.C., she spends her days in her home state visiting local facilities, meeting with constituents, and engaging in listening sessions like these. “Every day that I don’t have a vote in D.C., I’m in the district,” she told me over the phone prior to our day together. “I’m spending one-on-one time with community leaders, local electeds, and business owners. And I think that’s really critical. You have to know what’s going on in your district.”

Staying in the know, however, is a gargantuan effort, one that the congresswoman says other representatives in “safer” seats don’t have to worry about quite so much. We’re at stop number two of four, a light day according to Tim Gowen ’10, her deputy district director, and Gluesenkamp Perez looks a little wan. She’s recovering from a bout of the flu that left her, her husband, and their 19-month-old son sick with fevers earlier in the week. After one day off, she’s back on the road. Still, her gaze is steady as she smiles and waves hello to the people she knows in the crowd. She holds it trained on every speaker over the next two hours, nodding and taking notes and occasionally interjecting with excitement or concern, never once yawning or looking away.

Though she’s unassuming in appearance, Gluesenkamp Perez has a certain star power

Zimmerman, representing the Clark-Cowlitz Farm Bureau, ended his time by saying, “I’d like all of us to understand the historic situation we have where a Clark and Cowlitz County representative from southwest Washington is on the Ag commitee. I don’t think that’s ever happened.” Applause ensued.

Gluesenkamp Perez particularly related to several speakers. Rob Baur, who owns Baurs Corner Farm and identifies as the CTO, or “Chief Tractor Operator,” shared his ongoing problems with a new John Deere tractor to illustrate a need for federal right-to-repair legislation. Perez agreed emphatically. “You can’t wait three weeks [to fix the tractor] when you’ve got harvest coming,” she said.

Her connection was visibly strongest to Nicole Curtis, a community advocate at Northwest Harvest, a hunger relief agency, who took the podium to request permanent protection for SNAP. Wearing a low, tight ponytail, Curtis kept her head down as she read quickly from her script. She spoke of struggling to feed her two sons after a pandemic layoff and the end of SNAP emergency allotments in February after President Biden signed the Consolidated Appropriations Act. In closing remarks, Gluesenkamp Perez called her out specifically to thank her for making the time to be there. After the session, she rushed to speak to her first. I caught up with Curtis as folks were filing out from the community center. She is a huge fan of the congresswoman; she even donated to Gluesenkamp Perez’s campaign. “She’s got a different energy; it’s refreshing,” she said.

“ That was the point where I was like, oh, I think I need to do this.” —Marie Gluesenkamp Perez ’12

The hours added up as we stopped at a community clinic and a food bank. Gluesenkamp Perez kept up the energy, even as she paused to occasionally blow her nose. Some of her remarks, like one on how empowering it is to know how to cook beans and rice, felt rote. But when she opens up to tell her own stories, she gets through to people. At North County Community Food Bank in Battle Ground, she shared that her grandma had volunteered at a food bank, which resonated with the crew. She also made it a point to emphatically thank everyone for their work throughout our tour.

After, I chatted with lavender-haired volunteer Bev Jones (Battle Ground Citizen of the Year 2016) to talk about the visit. Jones stays away from conflict, which makes it tricky to talk politics with neighbors displaying Joe Kent signs in their yard. But she’s happy Gluesenkamp Perez won and hopes that she hangs on to the seat. “I

appreciate her being a woman in that position and a small business owner. Just her showing up with her questions today, I’m even more impressed,” she said. She paused and smiled, before doing a little wiggle. “She’s my girl.”

When Gluesenkamp Perez decided to run for office, the first order of business wasn’t brainstorming how to fundraise or hire consultants, but securing childcare (an issue she has spoken passionately about; she and Dean often brought Ciro with them to the auto shop because they couldn’t find affordable daycare). She called her mom and motherin-law to ask for extra support during the campaign. Then, she needed to get Dean on board; he was hesitant. “It’s a family decision to run for Congress,” Gluesenkamp Perez said. “He really believes in me, and his perspective was, I’m not just saying yes to a campaign. If

you run, you’re gonna win. And that’s going to change everything about our life.”

Dean ended up being right.

The odds were not in her favor. With a lack of support from the DCCC and even groups like EMILY’s List, which supports women candidates in favor of abortion rights, she embarked on an intensive grassroots campaign. (Emily’s List endorsed her in October 2022, less than a month before the election.)

“All the pundits said I had a two percent chance, and I get it, people try to make strategic decisions,” Gluesenkamp Perez said. “But it’s hard when they say they want people who work in the trades, and women, and moms, and Latinos. Like, where the hell are you?” Finding media coverage was also a challenge. She reached out to me a year ago to cover her story; the New York Times declined the pitch (now, the Times’s coverage of Gluesenkamp Perez includes an array

of reporting and opinion, with headlines like “A New Voice for Winning Back Lost Democratic Voters”).

When we finally got to have our interview, we lamented the paradox facing underdog candidates: you need a critical mass to get people to pay attention, but how do you gain that critical mass? Gluesenkamp Perez credits the support of her local community for believing in her at the beginning: “You just work your phone book, and go from there.”

One connection led to another, and once she had an audience, her message—of supporting working families, championing small business owners, ensuring abortion access, investing in clean energy, and increasing education in the trades—resonated. Her platform leaned centrist, which may have helped appeal to Republicans who weren’t sold on Kent’s extreme views. And surely, so did her earnestness as a regular, small business–owning mom. Without coaching or party pressure, she was able to talk about what was meaningful to her and people in her district. In interviews, she speaks candidly and passionately, often interjecting a curse or a quip into a serious remark. She’s shared personal stories during her campaign of her own economic hardships and a previous miscarriage before having her son.

After seeing Gluesenkamp Perez give her stump speech, Love was impressed by her authenticity. “That’s when I was like, if more people can see her do this, she could really win this thing,” Love said. Love worked on the campaign in a small role, helping organize several rallies and field events to harness a swelling of grassroots support. “The first event was unlike anything I’ve seen,” she said. There weren’t many traditional party activists; instead, attendees included firsttime volunteers, first-time voters, and people who just wanted to meet Gluesenkamp Perez after reading about her.

Gowen joined the campaign during the summer as one of two staff members, with no prior political experience (Gowen previously owned a prepared foods store in Portland, Oregon).

Other Reed alumni also pitched in for the campaign. David Azrael ’13 assisted with social media; Sandeep Kaushik ’89 was campaign spokesperson. Washington First District Congresswoman Suzan DelBene ’83 has been a “huge supporter,” according to

Gluesenkamp Perez. Notably, DelBene was the only member of Congress who endorsed Gluesenkamp Perez before the top-two primary election in summer 2022.

The campaign involved long, tough days. When she won, Gowen said, “We were all exhausted.” But in the face of the damning election predictions, the moment felt monumental to the tiny team. “It was one of the highlights of my life,” said Gowen. “It was a crazy thing that no one thought we were going to do.”

Gluesenkamp Perez was sworn into the 118th Congress on January 7, 2023. Now, six months into Congress, she’s been appointed to the Small Business and Agriculture committees. Having won, she said she doesn’t feel beholden to vote on party lines. “The things that feel small and unimportant to a lot of national players are the things that are really meaningful to everyday people in my district,” she said.

Instead, she wants to focus on serving her constituents—she doesn’t hide from them. She’s been holding town halls over recent months, something her predecessor, Jaime Herrera Beutler, failed to do. Some politicians are wary of hosting in-person meetings after former Arizona Representative Gabby Giffords was shot in 2011; Gluesenkamp Perez likes to remind people that she owns a gun (defense of the Second Amendment is part of her platform). The town halls have been going “shockingly well,” she said.

Gluesenkamp Perez has to balance national priorities with local ones, and some of her bipartisan votes so far have raised eyebrows—or backlash. She has joined as a co-chair of the moderate Blue Dog Coalition, and as we were sending this piece to press, she was one of two Democrats to vote in favor of a resolution to block President Biden’s student debt forgiveness plan. (At time of writing, the Senate had passed the bill and President Biden had vetoed it; the Supreme Court is expected to rule on the plan this summer.) Her statement via Twitter felt like a red herring: it demanded dollar-for-dollar investment in trades education before she would support debt forgiveness. The tweet was ratioed (which means it received more negative replies than likes), with replies criticizing her and expressing hope that she gets challenged in the 2024 primary.

I remarked to my editor that the longer we waited to publish the piece, the more time Gluesenkamp Perez had to take important or controversial actions that we would need to address. But of course, this is the point of being a politician—to take a stand— and the challenge of writing an early-career profile. Gluesenkamp Perez didn’t run a typical campaign. She is not your typical congressperson, and she won’t do typical things. She’s still a developing story.

It seems that Gluesenkamp Perez has never been one to ask for permission, or follow a conventional path. “She definitely gave our parents more gray hair than I did,” said Philip Perez, the congresswoman’s brother. The youngest of four, Gluesenkamp Perez grew up in Houston, Texas. Her father was a pastor in an evangelical church, and the family was involved in the church growing up. Her parents leaned politically and religiously conservative. Gluesenkamp Perez credits the exposure with helping her feel open around all kinds of people. She and her siblings were home-schooled by their mom for their early education, and their parents instilled an appreciation for intellectual curiosity and open-mindedness. “It was important to question things, think about things, and find out the answer for yourself,” said Philip Perez of their upbringing. The kids often spent summers in Bellingham, Washington, hanging out in their grandfather’s carpentry shop and gaining an appreciation for the woods around them. Gluesenkamp Perez comes from a long line of loggers on her mother’s side. “Even as a child the trajectory I saw for my life was living back home in Washington,” she told me. “So after graduating [from Reed] there was no real question that I’d remain up here.”

After graduating from high school, she spent a semester at Warren Wilson College, known for its focus on work and service, before discovering Reed. Her parents stopped paying for tuition when she stopped going to church. “Afterwards, I worked three jobs and paid for Reed by the credit hour; working as a nanny, barista, and in an iPhone case factory,” she told me over email.

At Reed, Gluesenkamp Perez was a thoughtful, creative student who was active in campus life, a member of Student

Senate—and who had a reputation for being down for anything, especially if it involved helping someone. One of her legacies at Reed is a memorial bench that sits in front of the Paradox, made from half of a fallen Doug fir tree on campus. When her boyfriend died before she graduated, she and his friends made the bench to commemorate him and other deceased Reedies. She rallied more than 40 students and faculty members to help haul and saw the 100-yearold tree during finals week in 2012. After 12 hours of pulling a two-man misery whip saw, they cut through. “What has shaded Reed for the past century will hopefully continue to serve its students for the next 100 years,” wrote Reed Magazine at the time. I stopped by the Paradox this spring and took a seat on the bench, stretching my legs all the way out across its width. It feels smooth and

I was the comanager of the bike co-op, and he was working as a mobile mechanic,” she said. “That was a place for us to bond and gave me a sense of freedom and agency that comes from being able to take care of your own shit.”

She looks back with some humor at trying to teach practical skills like bike repair to Reedies who embraced a life of the mind. “I will literally never forget trying to teach a physics major how to hold a wrench,” she said of working at the bike co-op. “That really throws into relief where this sort of liberal arts education begins and ends.”

Since her swearing in, she has made disparaging comments about higher education, including tweeting that “the system needs a total overhaul” before she would back student loan forgiveness. With her dogged support of working families, it sometimes seems

cool, a little worn. Sitting on it, you feel held.

It’s fitting that Gluesenkamp Perez left such a practical monument behind. Ten years into co-owning an auto shop, she champions the trades, and investment in technical education, over getting a college degree. Yet she appreciates her liberal arts education and certainly worked hard to get it. She was driven by a desire to prove herself. “I felt a four-year college degree would serve as some form of validation,” she said.

As an economics major, her thesis interrogated the effectiveness of Portland’s composting system. Advisor Prof. Noelwah Netusil [economics] was struck by Gluesenkamp Perez’s measured approach. “[It was] a very insightful, sophisticated question for someone to be asking, because you can imagine a lot of people being like, of course, it’s good,” Prof. Netusil said. As it turned out, when the program was getting started, Portland lacked the infrastructure to process the compost locally; instead, they were driving it to the Canadian border, leading to increased emissions.

A highlight of her time at Reed was managing the bike co-op; the experience helped spark an interest in right-to-repair legislation. “When I started dating my husband,

like she is pitting people who work in the trades against those with college degrees. Yet when asked for further comment on her statement, she provided an 850-word response with much more nuance. (The response was later sent to her campaign email list with the subject line “This is why I’m in Congress.”) She disagrees, essentially, with the classism higher education can perpetuate, and said changing perceptions of people without college degrees was a major motivator to run for Congress. “When I say the higher education system needs a total overhaul, I mean that we need one that costs less and provides more opportunities for different types of education in different types of fields,” she said.

Gluesenkamp Perez credits Reed with helping her learn to defend her ideas, and appreciates the value that students placed on hard work (even if it sometimes felt obsessive). “When I was at Reed you weren’t indoctrinated, you were given tools for analyzing what’s in front of you,” she said. She felt her background gave her a different perspective than many students, but she wasn’t afraid to engage with them. “I’m comfortable talking to people when we don’t agree about issues, or we don’t have the same worldview.”

“It’s really powerful to have a background in critical analysis and argument, but also, what’s the reality going on around you?” —Marie Gluesenkamp Perez ’12

It’s clear that Gluesenkamp Perez doesn’t believe a liberal arts education should be branded as superior to a trade education, but also that she has benefited from experiencing both. “There’s something to the stochastic art of being a mechanic,”she said. “I could write the best essay about the car being fixed. If it doesn’t run, it doesn’t run.” Still, she keeps books from classes with Prof. Netusil and Prof. Jan Mieszkowski [German], her Hum 110 professor, in her office. A marriage of intellectual curiosity with pragmatic, hands-on experience is ideal in Glusenkamp Perez’s view: “It’s really powerful to have a background in critical analysis and argument, but also, what’s the reality going on around you?” She is a rare politician that embodies that duality in Congress, keeping a foot—or a hand—in both worlds.

In the car between stops during our tour, Gowen passed back a press release on the mifepristone ruling for Gluesenkamp Perez to approve. (The drug, which is widely used for medical abortions, is the subject of a Supreme Court case about its continued availability after a preliminary overturning of FDA approval. At time of writing, the FDA still approves access for it.)

Gluesenkamp Perez had a 103-degree fever when news about the overturning broke. She simply quote-tweeted an announcement from Planned Parenthood with the word “Bastards.”

Now, she was polishing up a more formal response. The response included mention of her work to reintroduce the the Protecting Reproductive Freedom Act, which gives the FDA authority over abortion medications. She credits her “amazing team” for helping her prioritize what to focus on. Though her staffers were focused and professional, they had the conviviality of a band on tour: they chatted about roofing, the importance of oil changes, and rent prices throughout the ride, sharing chips and jokes in between briefings. It was a little jarring to swing from the silly to the serious so many times. When I asked Gluesenkamp Perez how she kept up with it all—keeping a pulse on both national and local issues while going through her daily life—she simply said, “It’s crazy.”

As dazzled as I was by watching Gluesenkamp Perez move with surety through a dizzying amount of interactions and decisions, I had to remind myself that

I was witnessing her on just one day—and it seemed like a good one. I asked if she had disappointed people yet. Had she made anybody mad? Yes, she said, and trailed off. She told me that she asks her advisors all the time if they are overpromising people. She shared an anecdote about a pair of Afghan pilots who visited her office to ask for help bringing over their families, who had been living in hiding from the Taliban for 18 months. The pilots looked “skeletal,” with bags under their eyes. She couldn’t do anything; the Afghan Adjustment Act, which would provide a path to residency for Afghans who helped the U.S., is stuck in the Senate. “We promised them,” she said. “That was really difficult.” She’s also spoken to a grief counselor for help on processing the emotional whiplash of being a congressperson, and “how to be with people on a human level, because it’s not just political.”

Beyond being a new politician, Gluesenkamp Perez is a relatively new mom. When I asked how she balanced family life with her new job, I appreciated her realistic answers to my questions, though they were hard to hear: there isn’t balance. There are choices. She prioritizes mornings with her son, and works at night after putting him to bed. On our tour day, she told me that her husband had asked her to stay home for the first time that week, when he and Ciro were sick. She had a scheduled meeting with veterans who would travel from all over the state to see her. She kept the meeting. “That was a low point for me in this whole thing,” she said, “that I couldn’t stay home.” Gowen interjected that Perez had been showered with praise for the meeting by commissioners and mayors who don’t typically support Democrats.

“So it was worth it,” Gowen said.

“I mean—” Gluesenkamp Perez paused. “You have to ask my husband if he thinks it’s worth it.” Sundays, at least, are for family.

Gluesenkamp Perez keeps moving forward: she’s already campaigning for 2024. Beyond making waves within the party, her win is inspiring people to consider how to get involved in their own neighborhoods, in their own ways. “My students were following her election very closely,” said Prof. Netusil. “I think she has inspired the current Reed students to pursue careers in public policy or to get involved in their communities, whether that’s the school board, volunteer

work, or running for elected office. They’re like, wow, she graduated 10 years ago, and she’s in Congress.”

Speaking to Gluesenkamp Perez a few months into her term, it’s hard to tell if she has enough distance from her own congressional win to advise others on how to pull off what she did. She still shared some thoughts for people looking to enter politics that were both simple and daunting. “Do what you’re good at, and do what you love, and be useful to your community,” she said. Most importantly, don’t wait for an approval or endorsement to act. “No one is going to give you permission to run,” she said, with a bit of an edge to her voice.

Gluesenkamp Perez’s story might help rewrite the larger narrative of who can win a federal election, and which campaigns deserve attention. “I do feel like we’ve sort of carved this new path and changed the conception of who can get elected and how elections can work,” she said. “And I’m very proud of those things.”

Prof. Netusil recalled a discussion in an econometrics class about the statistics of Gluesenkamp Perez’s predicted chances of winning after FiveThirtyEight, a prominent polling and political website, gave her that two percent chance. Forecasting, Prof. Netusil told her students, can be wrong. “They don’t know Marie like I know Marie,” she said. “And if anyone would have beaten those odds, it would have been Marie.”

Good poetry is meant to be disruptive. Subversive and indigestible, it enters the cultural bloodstream as a corrosive irritant. Resistant to containment and mass assimilation, it endures on its own terms like the timeless verses of Shakespeare.

So declared Kenneth Rexroth, leader of the San Francisco Renaissance literary movement. In the early 1950s, he welcomed into his North Beach circle three aspiring poets fresh out of Reed College— Lew Welch ’50, Philip Whalen ’51, and Gary Snyder ’51. Under Rexroth’s tutelage, the trio began waging their own poetic assaults on America’s post-war materialistic appetite.

Crossing paths with Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, they found themselves earmarked as the Beat movement’s West Coast wing. It was a pigeonhole Snyder, for one, sought to evade. By the time the movement morphed into the innocuous beatniks, he had embarked upon a 10-year sojourn to Japan, immersing himself in Zen Buddhism, haiku, and Chinese poetry.

Combining those Asian influences with his undergraduate studies in the classics, modern literature, anthropology, and Native American mythology, Snyder was able to forge a fresh and original way of looking at the world, one that fostered one of the most singular and distinctive voices in modern poetry.

Last year, the 93-year-old Snyder was honored by the Library of America, who published his collected poems in their preeminent book series of prominent poets and writers. In celebration, a tribute was held, featuring testimonies from various distinguished literati.

After expressing his gratitude for the accolades, Snyder pointed out that his social anarchism, which views liberty and social equality as interrelated, had been largely overlooked. Its influence on his work, he said, was “not quite unspoken but very subtle often, or simply assumed in directions and spirits.”

It was a gentle reminder that there is nothing safe about a Gary Snyder poem.

Beneath the common speech-patterns and close, intimate attention to natural imagery, his poems elicit a complex interaction, resonating with the reader, consciously or unconsciously, on multiple levels. That Coyote— the slippery, wily trickster who warily keeps his distance from civilization was a favorite Native American archetype during his studies at Reed should come as no surprise.

The allure of Snyder’s poetry begins with the language itself. He cites Ezra Pound, a strong lyricist with an ear for words, as the first poet to truly speak to him. Similarly, Snyder’s cadence is crisp and clear. He lays down familiar terms in unfamiliar juxtapositions with rhythms borrowed from hand work. The approach is spelled out in his poem “Riprap,” a term he defines as “a cobble of stone laid on steep, slick rock to make a trail.”

Before your mind like rocks. placed solid, by hands.

In choice of place, set

Before the body of the mind in space and time:

Solidity of bark, leaf, or wall riprap of things

The “things” in a Snyder poem are largely drawn from the physical landscape. Finely distilled, they radiate a translucency easily mistaken for simplicity. But beneath their surface simplicity lies a terrain of unsettling depths, as in the poem “Piute Creek,” where a panorama suddenly coalesces with deep time:

Hill beyond hill, folded and twisted

Tough trees crammed

In thin stone fractures

A huge moon on it all, is too much.

The mind wanders. A million

Summers, night air still and the rocks

Warm. Sky over endless mountains.

All the junk that goes with being human

Drops away, hard rock wavers

After returning from Japan in the mid-’60s, Snyder settled with his wife and two children among a community of backto-the-land Zen aficionados in the Sierra foothills. As his general focus shifted to being rooted in place, his poetry became stylistically more emotional, metaphoric, and lyrical. It also gained relevance among those increasingly concerned with the natural world.

Because Snyder’s views are often so nuanced, drawing from a wide range of references with a timescale extending back 10,000 years, it’s possible for various schools of thought to adopt him as their own. Hence, his popular designation as “poet laureate of deep ecology.” As an environmental movement, deep ecology seeks freedom from the dichotomy of human civilization and nature by viewing humans as equal and interconnected with all other forms of life.

But Snyder is not so easily packaged. The trail he lays out toward such freedom ultimately leads into the wilds of Zen impermanence and emptiness.

“To be truly free,” he writes, “one must take on the basic conditions as they are— painful, impermanent, open, imperfect— and then be grateful for impermanence and the freedom it grants us . . . The world is nature, and in the long run inevitably wild, because the wild, as the process and essence of nature, is also an ordering of impermanence.”

His poem “Ripples on the Surface” points to the trail’s end.

The vast wild the house, alone. The little house in the wild, the wild in the house.

Both forgotten. No nature

Both together, one big, empty house.

The latest book by William R. Ware ’53 covers chronic diseases that are typically viewed as incurable. Drawing on expertise gained over 14 years of writing newsletters for International Health News, he discusses heart disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, and more. He documents non-drug interventions that can aid prevention, delay progression, or even induce remission. (Lux & Associates, 2022)

David Coleman ’60 has written a book of memoirs about traveling the country the oldfashioned way, “riding the rails,” and the connection points among science, education, politics, and geo-relations. Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus at the Odum School of Ecology, University of Georgia, he has been exploring the upper layer of the ground on which we tread, quite literally, around the world. (Bilbo Books, 2022)

the Planet

The latest book by Bob Gottlieb ’65, professor emeritus at Occidental College, presents a framework for creating a more just and equitable carecentered world. He examines how a care economy and care politics can influence and remake health, climate, and environmental policy and the institutions and practices of daily life. (MIT Press, 2022)

A new book by John Daniel ’70 is a varied meditation made of 382 haiku-like three-line stanzas and 11 brief passages of prose. The work began as a loose haiku journal of a year spent in the sagebrush and juniper country of south-central Oregon. John says, “I found myself sketching a kind of cosmic creation story, based on my reading in science and philosophy as well as my own hunches and spiritual inclinations.” (Broadstone Books, 2023)

Marjorie Ingall and Susan McCarthy ’77 draw on research in psychology, sociology, law, and medicine to explain why a good apology is hard to find. Alongside their six (and-a-half)-step formula for apologizing, they delve into how to respond to a bad apology; why corporations, celebrities, and governments seldom apologize well; how to teach children to apologize; and how gender and race affect both apologies and forgiveness. (Galley Books, 2023)

Monica Wesolowska ’89 has published the tale of a mother who supports her son from the moment he floats into the air and doesn’t come down. This story for kids offers themes of difference, unconditional love, and transcending bigotry to find our place in the world. The New York Times said, “This effervescent parable of a floating boy, about rising above when others want to keep you down, is whimsical and relatable, thanks to Wesolowska’s warm anecdotal language and [illustrator Jerome] Pumphrey’s lighthearted art.” (Dial Books, 2023)

Ann Campbell ’94 upends a traditional trope— the model of hierarchical family—and in doing so offers refreshing analysis of canonical British novels. She explores the concept of surrogate family as a signal of cultural anxieties about young women’s changing relationship to matrimony at that time. A professor of English at Boise State University, Ann argues that female protagonists in these works assemble chosen families rather than families of origin as a means of exploring the world and themselves, preparing for idealized marriages, or sidestepping marriage altogether.

(Bucknell University Press, 2022)

In her first full collection of poetry, Sarah Barnsley ’95 explores manifestations of intrusive thoughts as part of obsessive-compulsive disorder before navigating through the twists and turns of recovery and love. A winner in the Poetry Society’s “Members’ Poems” competition in 2021 and 2018, she is senior lecturer in English and American literature at Goldsmiths, University of London. Her earlier work focused on modernist poet Mary Barnard ’32, and in Mary Barnard, American Imagist (2013), she examined Barnard’s poetry and poetics in the light of her correspondence with Ezra Pound. (Smith | Doorstop Books, 2022)

Heidi Duckler Dance: 2016-2021

Heidi Duckler ’74 has published a visual compilation book of her dance company’s works from 2016 to 2021. She is the founder and artistic director of Heidi Duckler Dance in Los Angeles and Heidi Duckler Dance/Northwest in Portland, Oregon. Deemed the “reigning queen of site-specific performance” by the LA Times, she is a pioneer of site-specific, place-based contemporary practice. (Independently published, 2022)

Bryson Hirai-Hadley ’04 has written a novel about the struggle for survival in the 23rd century. After runaway global warming has led to a climate apocalypse, technician Jacob Watz ventures outside to maintain cooling systems and oxygen generators in the toxic atmosphere. One day a mysterious explosion makes him question whether the Township really is the only remaining human settlement— and if it has any hope for survival.

(Independently published, 2022)

Beth Reddy ’05 takes readers on a journey into the world of Mexican earthquake-risk mitigation in her new book. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork and archival data, she conducts a qualitative analysis of controversial earlywarning technology and considers the requirements and uses of the alert system. Beth is assistant professor of engineering, design, & society at the Colorado School of Mines, with a joint appointment in geophysics. (MIT Press, 2023)

Amy Foote ’00 edited a feature-length documentary (her 14th!) that was nominated for an Oscar at the 2023 Academy Awards. The film won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival in 2022 and an Independent Spirit Award earlier this year. It chronicles the life of rebel photographer Nan Goldin and her fight against the billionaire Sackler family and their opioid business, Purdue Pharma. David Velasco ’00, now editor in chief of ArtForum magazine, is interviewed in the film. (HBO Max, 2022inf)

Don Berg MALS ’12 has received national recognition for a book combining a scientific model of motivation and engagement, self-determination theory (SDT), with an analysis of successful holistic education. A psychological researcher, Don is concerned with the primary human needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and he argues that the central problem in schools has less to do with academic instruction and more to do with the psychology of learning. (Publish Your Purpose, 2022)

Los Angeles Bungalow Architecture

Ethics and Time in the Philosophy of History: A Cross-Cultural Approach

Bennett Gilbert MALS ’12, assistant professor of history and philosophy at Portland State University, has two new publications to share. The first was cocreated with photographer Harry Zeitlin and shows how Los Angeles shaped the nation’s culture in the 20th century with its bungalow style of middle-class housing. (Arcadia Publishing, 2022) The second book is an interdisciplinary volume coedited with a colleague, Natan Elgabsi, and it connects the philosophy of history to moral philosophy with a unique focus on time. (Bloomsbury Academic, 2023)

(tr. Notices from The Paris Commune)

Composer John Andrew Wilhite-Hannisdal ’13 penned an opera written after a libretto by Norwegian dramatist Finn Iunker based on newspapers, letters, and other texts published by the Communards in the days leading to the bloody end of their revolution. It is a meditation on democracy, collective responsibility, and the place of the voice in all of this. The work premiered at the Norwegian National Opera in fall 2022.

Prof. Peter Steinberger [political science] has published Rationalism in Politics, in which he engages with major proponents of post-Kantian thought, analytic and continental alike, to show how political judgment and political action are grounded in considerations of human reason. Arguing against emergent and even dominant tendencies of recent political thought that emphasize the so-called primacy of affect, he challenges political theorists to take account of important themes in philosophy on the topic of human rationality. With a focus on influential arguments in the philosophy of mind and the philosophy of action, he seeks to reanimate the close connection between systematic philosophical speculation on the one hand and the theory and practice of politics on the other. (Cambridge University Press, 2022)

Adela Zamudio: Selected Poetry & Prose

Lynette Yetter MALS ’21 translated works from the Spanish and was a finalist for the 2023 PEN Award for Poetry in Translation. This is the first book in English showcasing the life and writings of Bolivia’s celebrated writer and educator Adela Zamudio (18541928). Lynette’s explorations grew out of her thesis for Reed’s master of arts in liberal studies (MALS) degree, “Domination and Justice in the Allegorical Story ‘La reunión de ayer’ by Adela Zamudio (1854–1928), Bolivia.” (Fuente Fountain Books, 2022)

And, in case you missed it, in 2018, Steinberger wrote a guide to the literature on political judgment as part of Polity’s Key Concepts in Political Theory series. What exactly is good judgment in politics? How is good judgment acquired, and how can we recognize it in others? This textbook, Political Judgment , addresses such questions by considering important developments in the history of political thought—ancient, modern, and contemporary—and introducing readers to ongoing debates about the idea of prudence or practical wisdom as it functions, or should function, in the realm of public affairs. (Polity, 2018)

These Class Notes reflect information we received by June 15. The Class Notes deadline for the next issue is September 15.

While a Reed education confers many special powers, omniscience is unfortunately not among them; your classmates rely on you to tell us what’s going on. So share your news! Tell us about births, deaths, weddings, voyages, adventures, transformations, astonishment, woe, delight, fellowship, discovery, and mischief.

Email us at reed.magazine@reed.edu. Post a note online at iris.reed.edu. Find us on Facebook via “ReediEnews.” Scribble something in the enclosed return envelope. Or mail us at Reed magazine, Reed College, 3203 SE Woodstock Blvd, Portland OR 97202. Photos are welcome, as are digital images at 300 dpi. And don’t forget the pertinent details: name, class year, and your current address!

EDITED BY JOANNE HOSSACK ’821951

Robert Richter is credited as coproducer and was the original director of the documentary film American Justice on Trial, about the Huey Newton trial and the constitutional guarantee of a jury of one’s peers, which was on the Oscar shortlist announced last December. Here’s one way to see it: https:// vimeo.com/694733653 (password: AJOT_1968).

1953 70TH REUNION

William R. Ware helps you beat the odds with his latest book. (See Reediana.)

1958