Reem S. Bukhamseen Portfolio | 2024

Contents Pediatric Opthalmology Hospital 04 NEXT Medical Office 10 Art Made Gallery 18 Al-Zahra, Kuwait | Interior Design Seattle, WA | Interior Design Ithaca, NY | Interior Design The Dust Up: Adapting Kuwait’s Civic Infrastructure to SDS 24 Kuwait City, Kuwait | Landscape Architecture Ashes to Ashes 46 Saugus, MA | Landscape Architecture Nestle Bentonville 56 Bentonville, Arkansas | Professional Practice Dominion Electric Showroom 59 Arlington, VA | Professional Practice Family Home 62 Rumaithiya, Kuwait | Professional Practice Writing Samples 64 Selected writing | Academia

Pediatric Opthalmology Hospital, Al-Zahra Kuwait

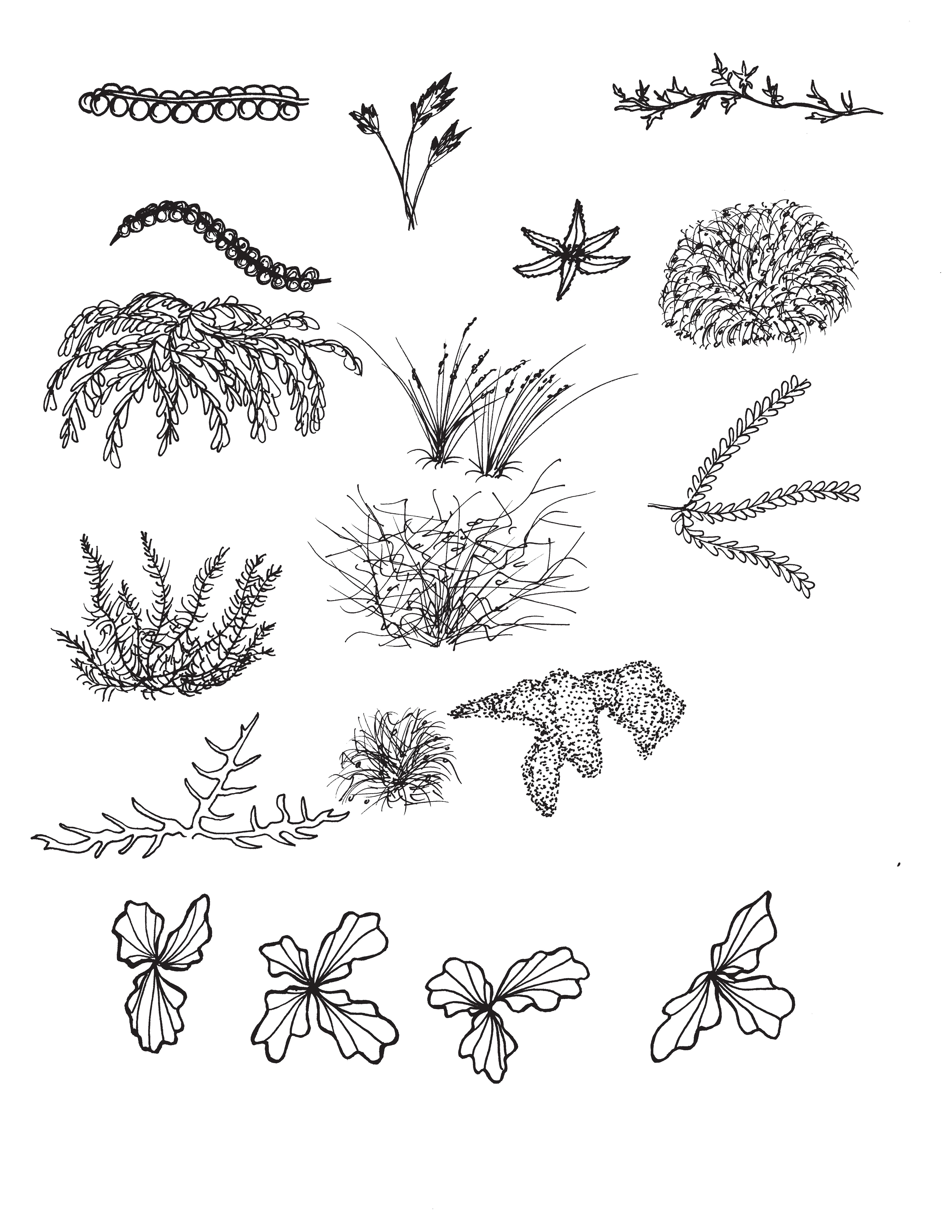

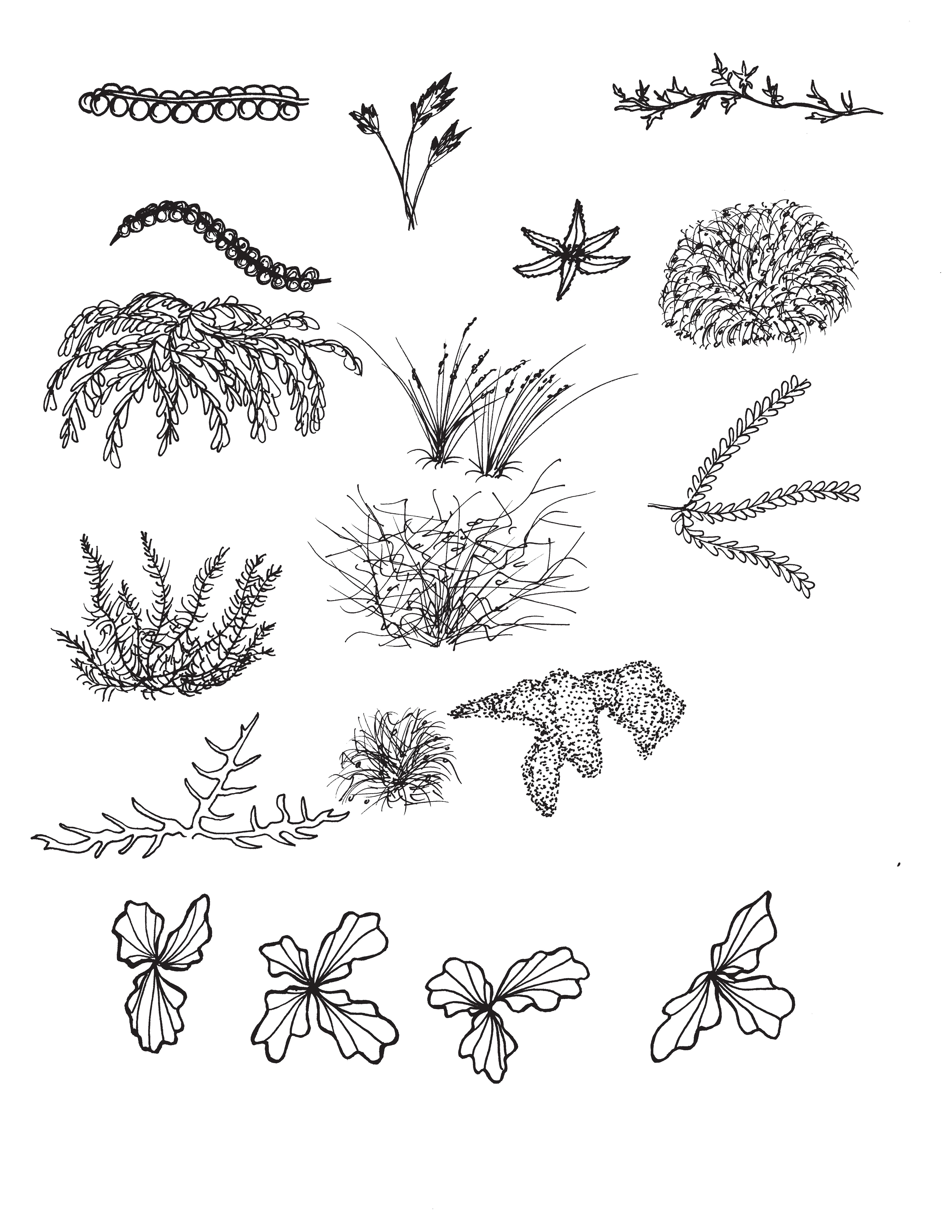

With Kuwait’s harsh arid climate, vegetation has adapted in order to survive in salty soils with limited water supply. Native plant species have developed different methods to not only withstand the climate, but also contain water. With roots deeper than the plant stems themselves, plant species are scattered throughout the landscape in order to reach unseen levels of ground water. On the surface level, the plants are seen to grow in almost a random pattern, but this in fact is an indication that the species have managed to reach ground water from that very spot.

Inspired by the sporadic growth of vegetation in select areas throughout the desert landscape of Kuwait, the Pediatric Opthalmology Center will implement multiple indoor

garden spaces that serve as self-sustaining ecosystems, working to harvest energy to maintain themselves and fuel the surrounding activities.

The Center will use these garden spaces as healing gardens, spaces for children to interact and play, as well as become focal points within the facility as the wellness services and activities will be located along it’s perimeter. Overall, the placement, function, and character of these gardens will allow users to easily navigate throughout the facility using the gardens as landmarks to distinguish different sections within the Center.

*Awarded first place for the ASID & IIDA Interior Design Excellence Award 2018.

4

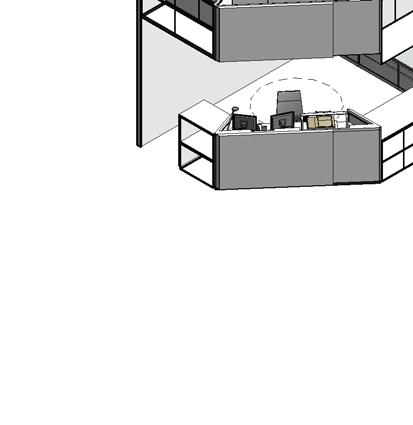

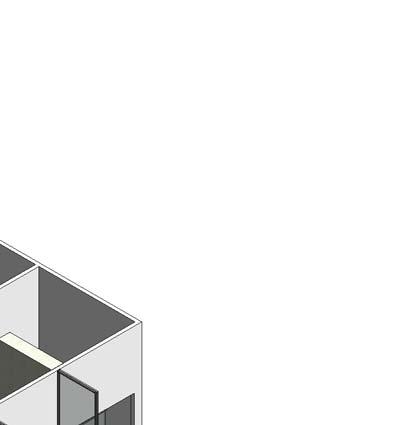

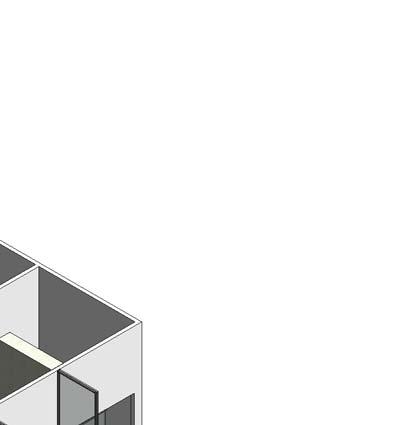

View of the Exam Room, Ground Floor

The gardens will experiment with the indoor/outdoor relationship between the plant species and the users as each garden will serve a different function. Using gray watering systems, native plant species and solar powered devices to harvest energy throughout the day, the gardens will act as an individual plant system surviving on it’s own mechanisms.

Integration of indoor garden spaces, both visually and physically accessible to all users of the facility, will increase staff productivity, progress healing, and enhance the patient’s experience.

The outdoor garden area connects all sections of the facility to one another by creating a shared focal space. Both wards connect allowing children, visitors, and staff members opportunities to interact while being exposed to natural light and fresh air. The garden acts as a self sustaining mechanism as it utilizes Kuwait’s natural landscape by specifying native plant species, covering the building’s roof with solar panels, using a gray watering system, and providing an overhead canopy to partially shield users from direct sunlight.

Main Circulation Study

Parti Diagram

Main Circulation Study

Parti Diagram

Ministries Zone Jaber Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah Hospital Housing District : Block 1 International Islamic Charitable Organization Housing District Block 7 SITE 5

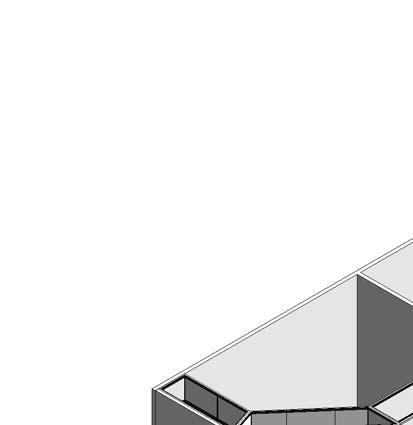

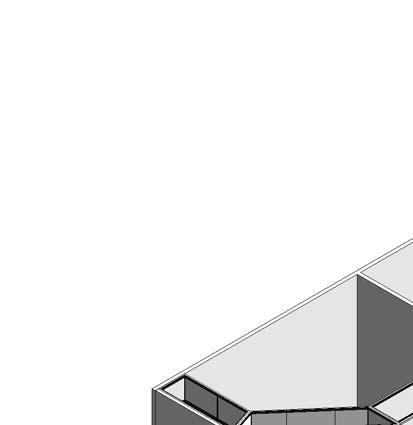

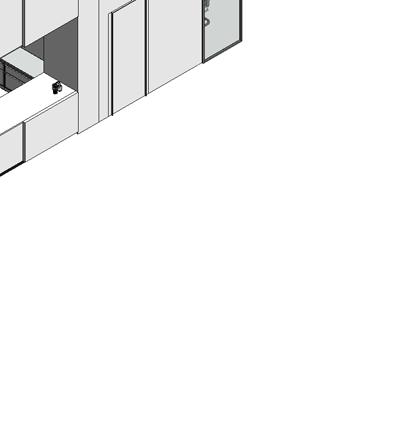

Massing Study

0 5 10 15 20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 1. Reception Area. 2. Check-In Desk. 3. Pharmacy. 4. Exam Room Waiting Area. 5. Exam Rooms. 6. Nursing Mother’s Room. 7. Storage Room. 8. Indoor Garden. 9. Prayer Rooms. 10. Procedure Room. 11. Dressing Room. 12. Doctor On Call Room. 13. Private Inpatient Suite. 14. Shared Inpatient Suite. 15. Nurse Station. 16. 0-9 Ward. 17. Medical Records Room. 18. Medicine Storage. 19. Children’s Play Room. 20. Head Nurse Office. 21. Storage Room. 22. Outdoor Garden Space. 23. Diagnostic Rooms. 24. Diagnostic Waiting Area. 25. Doctor On Call Room. 26. Indoor Garden Space. 27. Prayer Room. 28. Procedure Room. 29. Private Inpatient Suite. 30. Shared Inpatient Room. 31. Nurse Station. 32. 10-15 Ward. 33. Medicine Storage. 34. Medical Record Room. 35. Children’s Play Room/Lounge. 36. Emergency Department. Floor Plan: Ground Floor 37. Private Inpatient Suite. 38. Doctor On Call Room / Entrance. 39. Minor Surgery Room. 40. Emergency Reception / Entrance. 6

0 5 10 15 20 1. Prayer Room. 2. Kitchen. 3. Staff Cafe. 4. Open Work Space. 5. Shared Doctor Offices. 6. Outdoor Seating. 7. Auditorium. 8. Indoor Gym. 9. Outdoor Bridge. 10. Prayer Room. 11. Nursing Mother’s Room. 12. Medium Conference Room. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 13. Large Conference Room. 14. Booth Seating. 15. Storage Room. 16. Surgery Reception / Waiting Area. 17. Nursing Mother’s Room. 18. Storage Room. 19. Dressing Room. 20. Procedure Room. 21. Private Inpatient Suite. 22. Shared Inpatient Room. 23. Nurse Station. 24. Surgery Ward. 25. Medical Record Room. 26. Medicine Storage. 27. Head Nurse Office. 28. Storage. 29. Indoor Garden. 30. Sub Sterile Room. 31. Surgery Room. 32. Theatre. 33. Waste Closet. 34. Indoor Garden. OPEN TO BELOW OVERHEAD CANOPY Floor Plan: Level 01 7

8

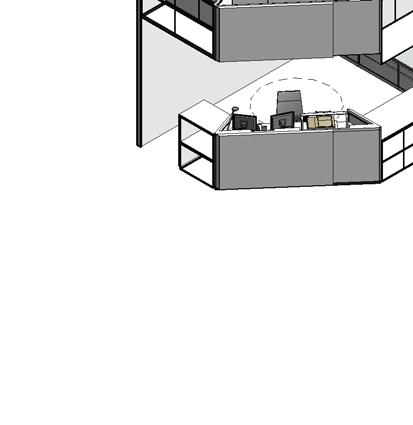

View of the Main Reception Entrance, Ground Floor

View of 0-9 Ward Nurse Station, Ground Floor 9

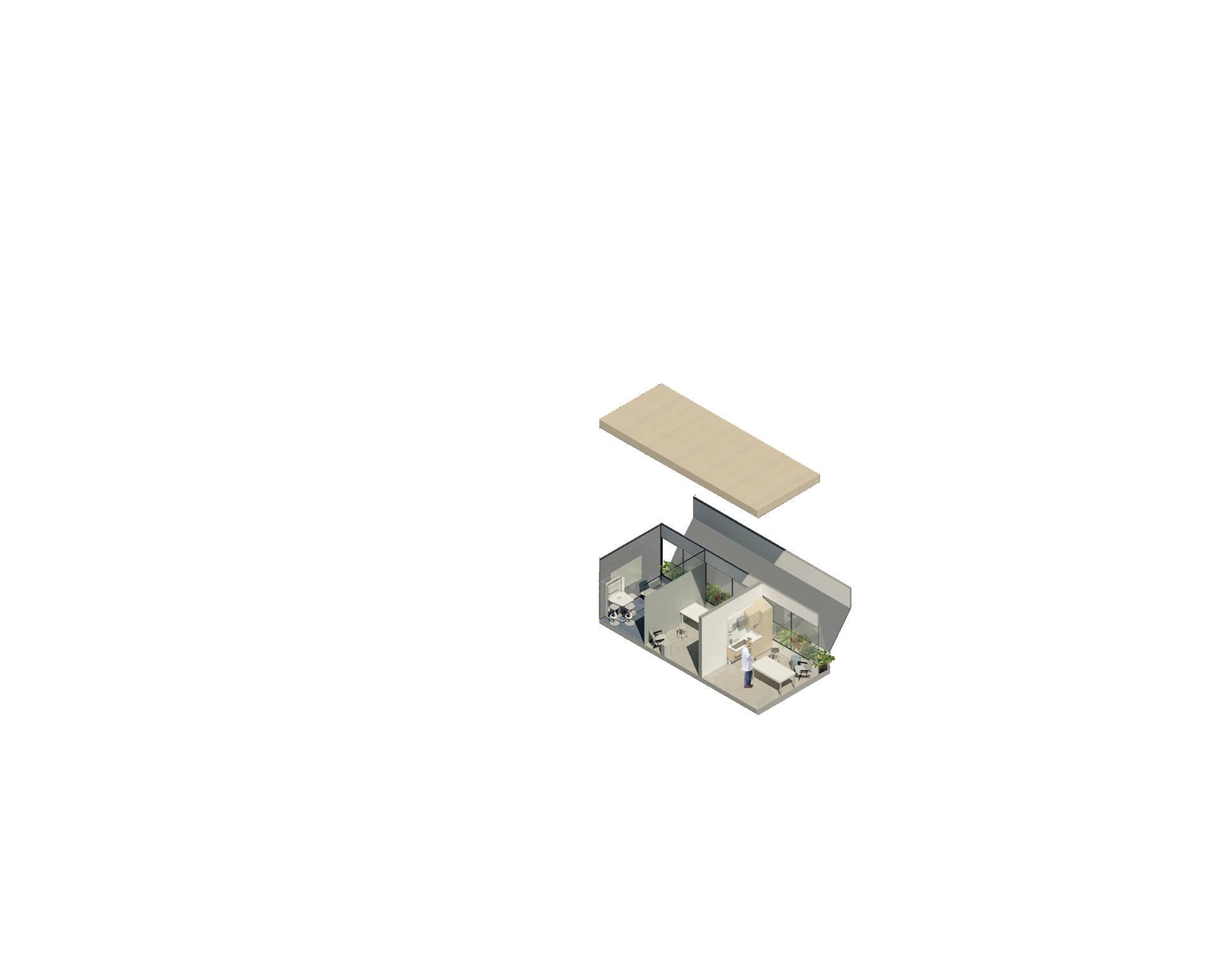

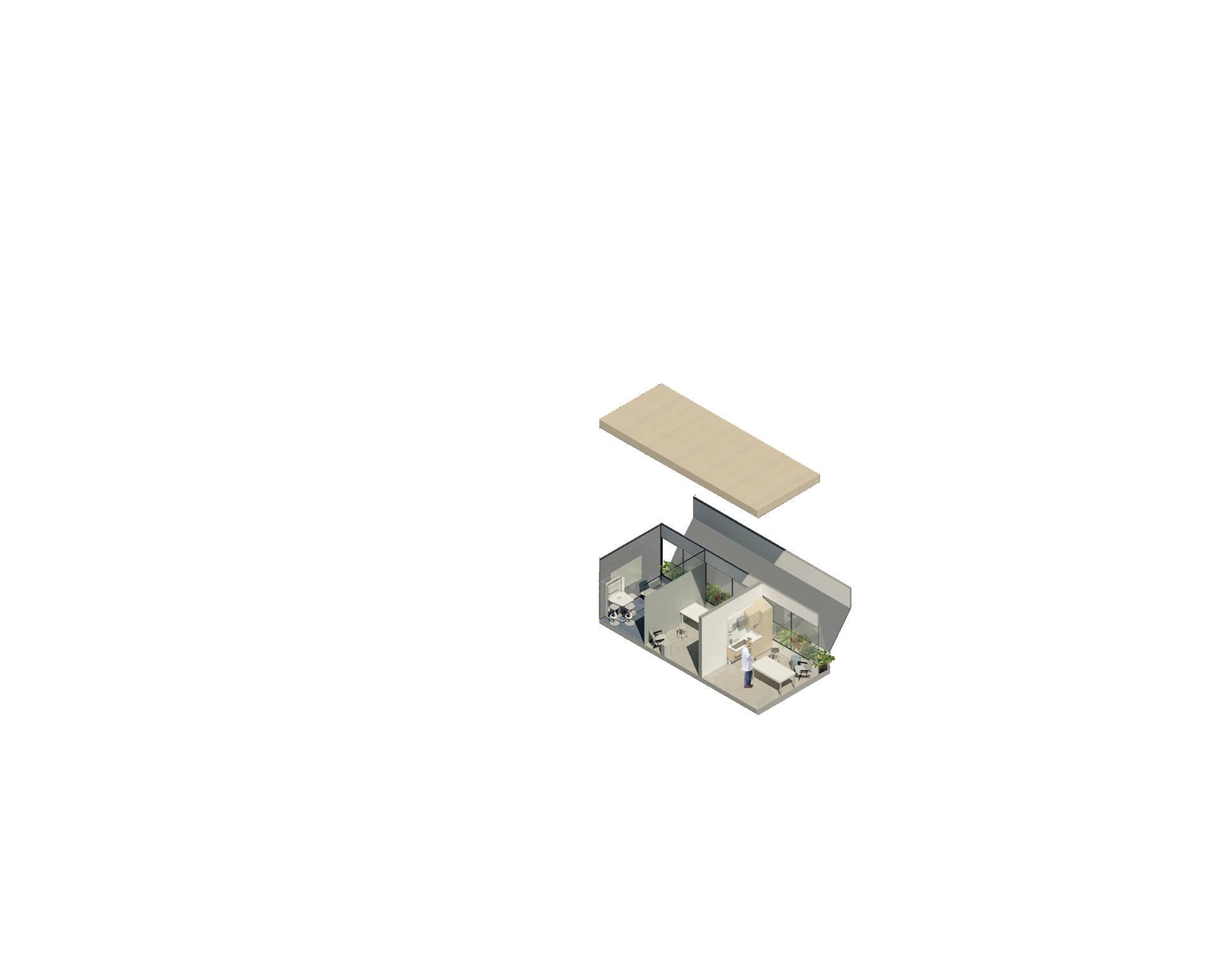

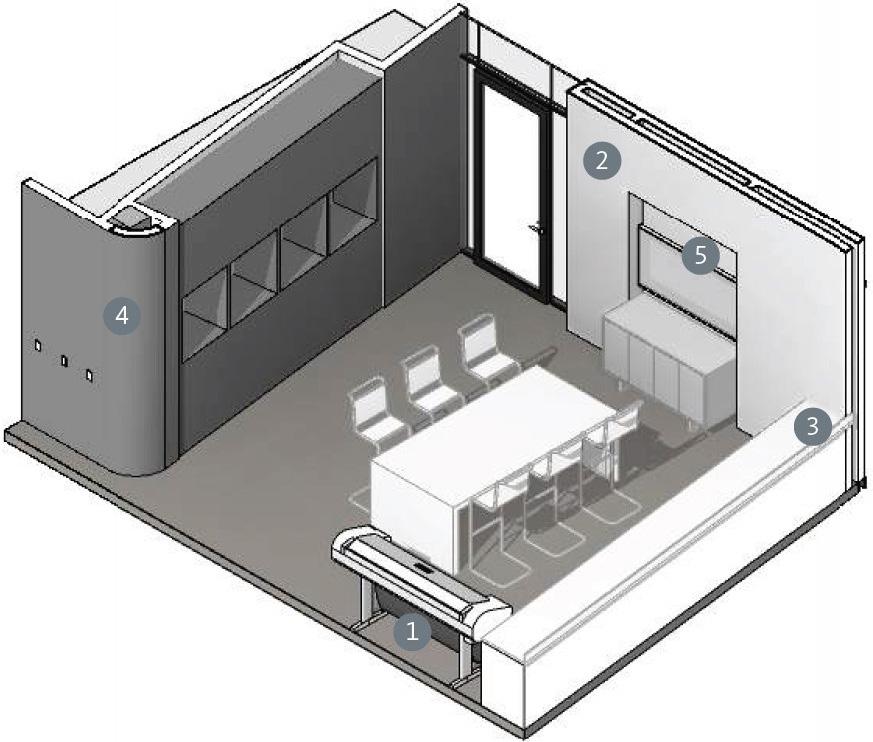

NEXT Medical Office, Seattle WA.

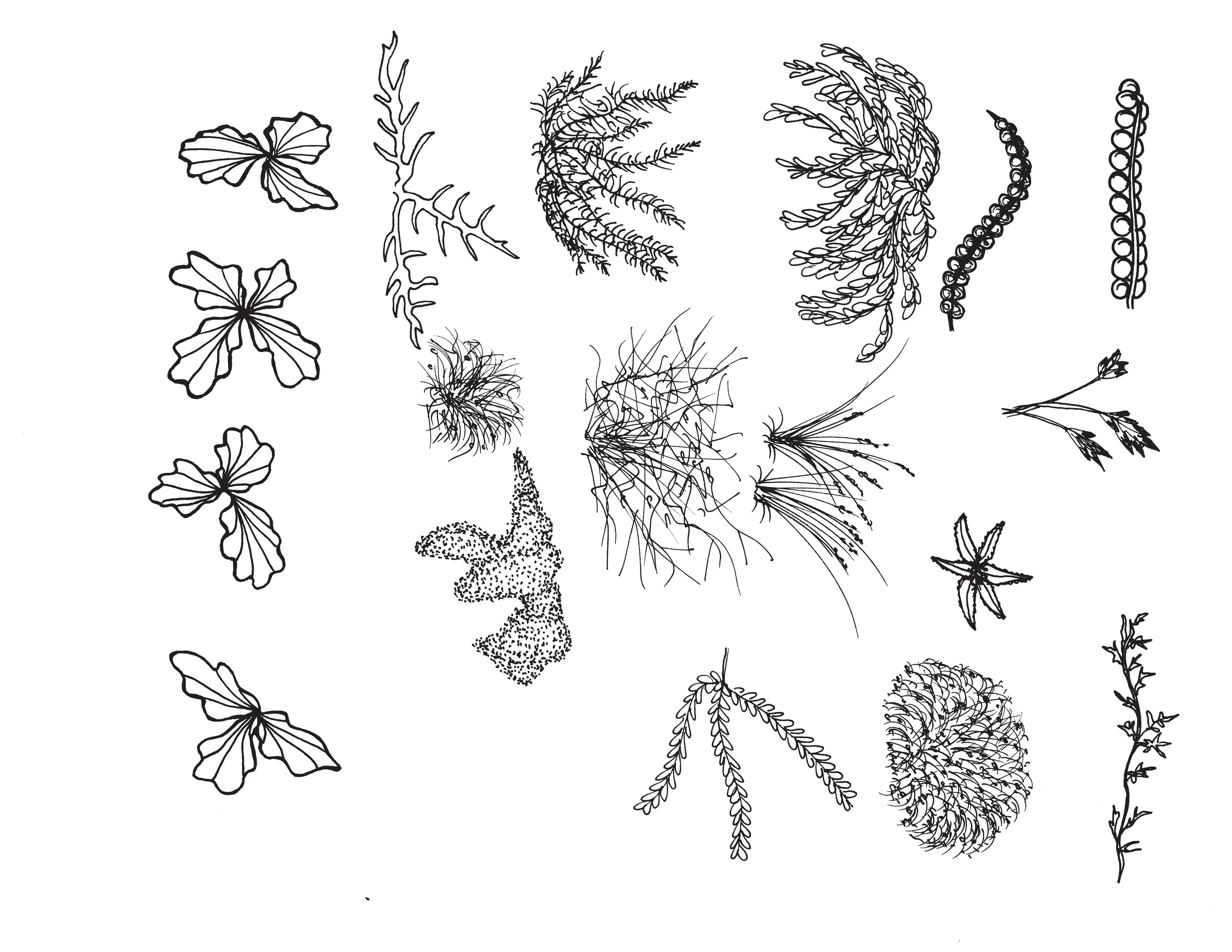

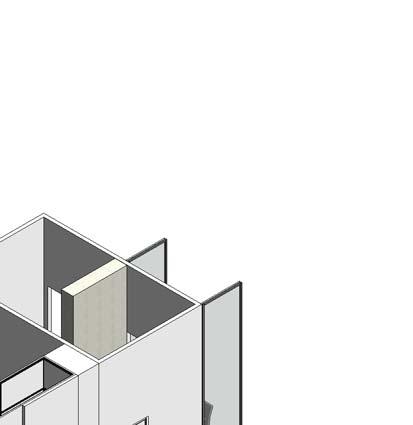

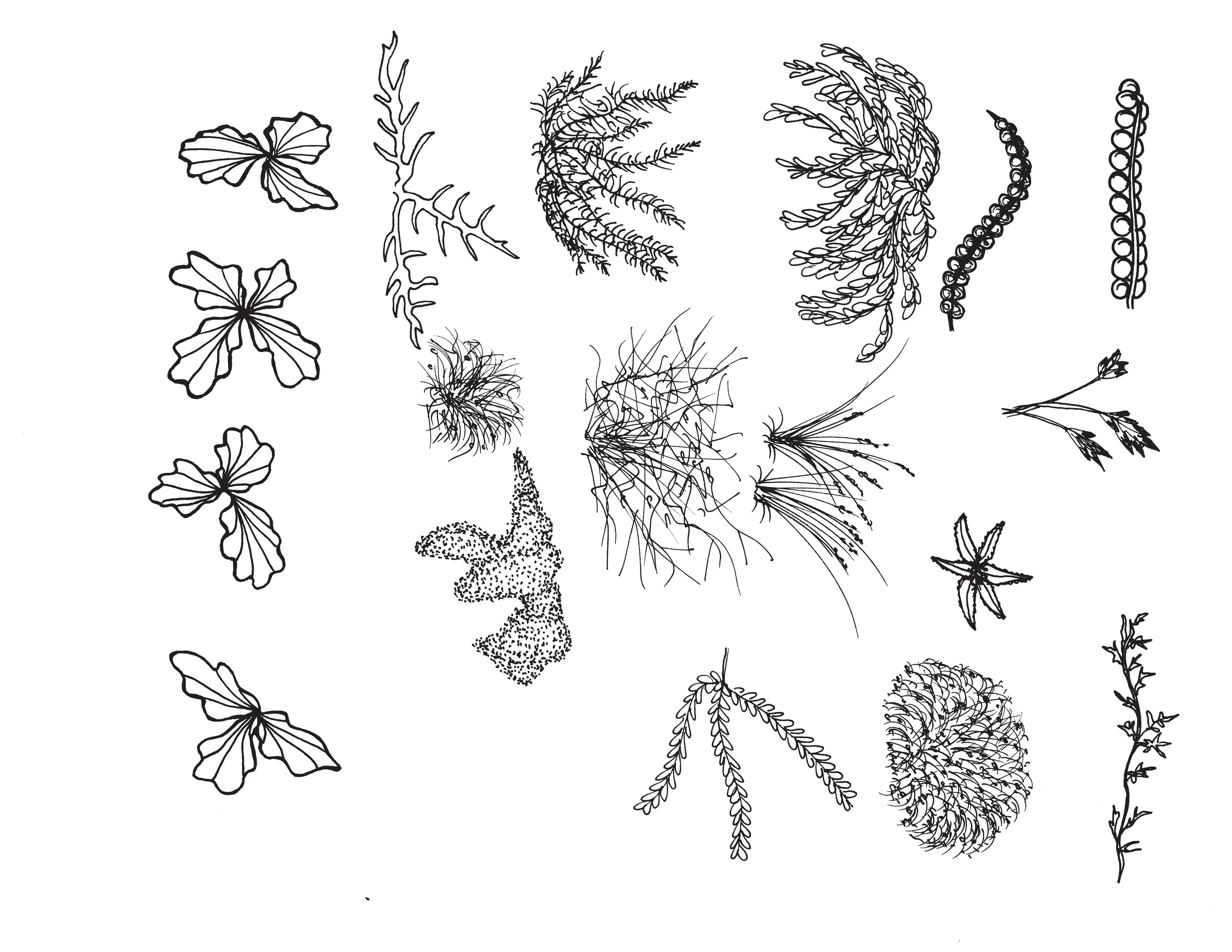

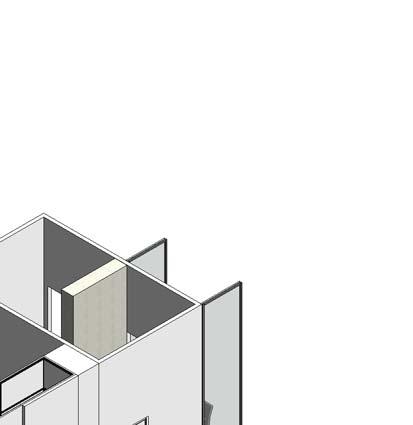

Inspired by Seattle’s urban layout in using the grid, the NEXT Medical Office uses an underlying grid framework to coordinate spaces within the program in a systematic way easily understood by all users. As a layout, the grid possesses familiarity with users, giving the patients the ease of being able to coordinate within an unknown space. By laying out spaces along a framed grid, users can easily navigate upon entering the medical office. The grid not only serves in way finding, but also allows spaces to be interchangeable due to their familiar sizes and shapes. It also serves to represent the NEXT Medical Office’s brand, showing the office’s bright and optimistic culture while still maintaining medical professionalism.

Given the program’s limitation of being unable to connect interior walls to the adjacent wall of windows due to the

unusual geometry, an opportunity arose. If this dead end corridor could be used for just circulation, it would also mean the doors would face the window and require more closure of spaces. But instead, if this space was used as a linear strip of indoor plants, that do not require much square-footage, this meant access to the windows was being taken advantage of fully. With this being said, because the linear strip is not accessible via a common pathway, almost full height operable windows are installed in the rooms adjacent to the exterior windows. This allows the user of the space to control the conditions in regards to accessing the plants or wanting more acoustic privacy.

*Awarded Steelcase NEXT Competition Honorable Mention, out of 800 competing students from 65 programs. View

10

of Education and Lifestyle Zone

The integration of the linear garden strip purifies the air and provides views to green spaces which boost focus and productivity.

To cater to the healthcare environment, the below recommendations were implemented:

1. Using sterilized soil-less growing media, which does not contain any material that could be used as a food source for mold, means optimum benefits.

Aloe Vera Indoor Purifying Plants

Showing Linear Garden Strip

Snake Plant Fecus Tree

Axon

View of Accupuncture Room

View of Exam Room

11

Macro Street Map of Seattle Micro Street Map of Seattle Program Zoning Axon

What makes NEXT the “Next” Medical Office?

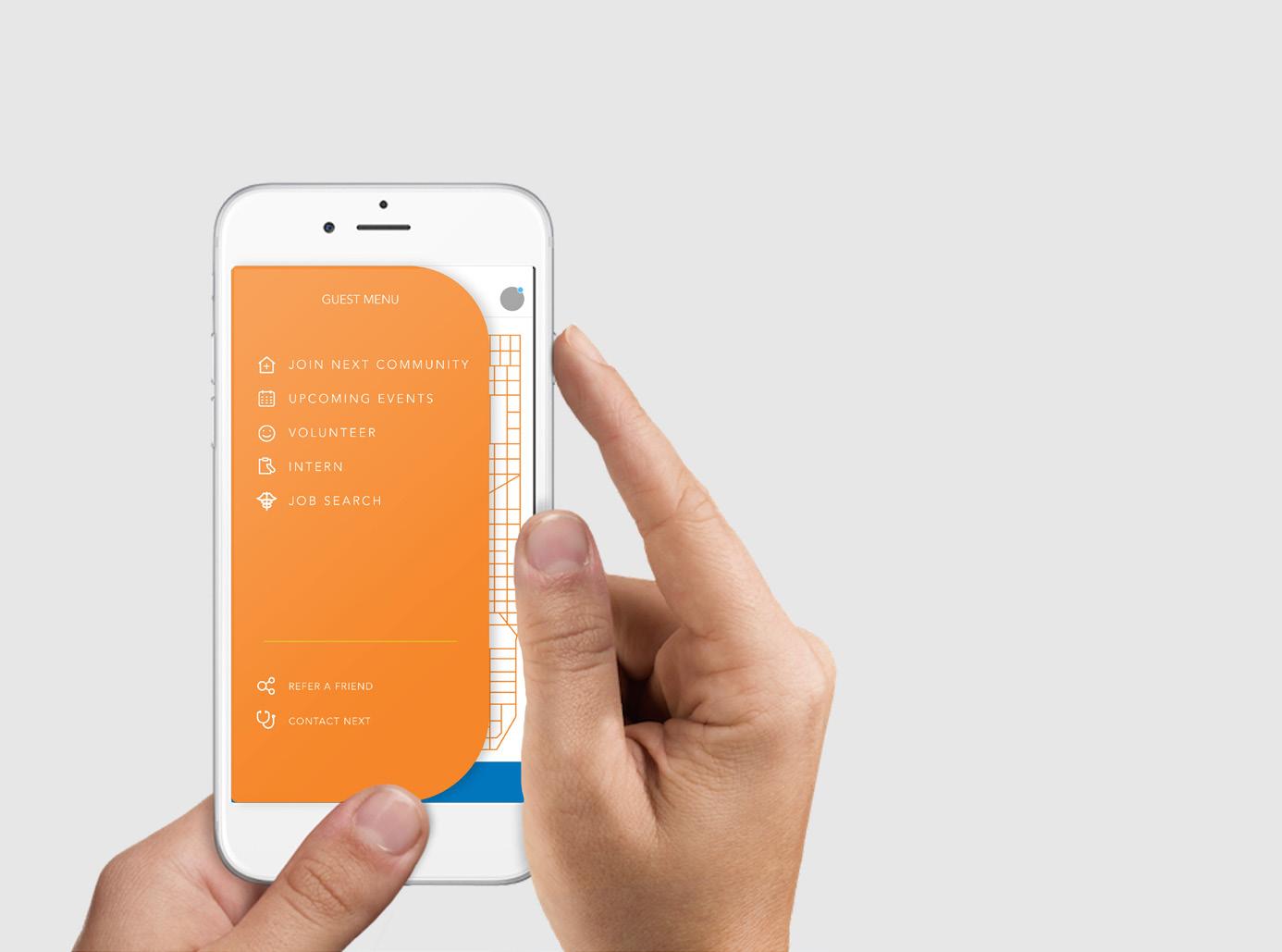

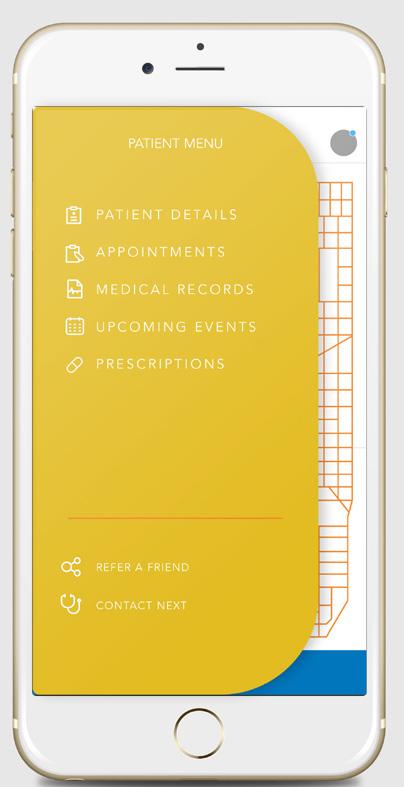

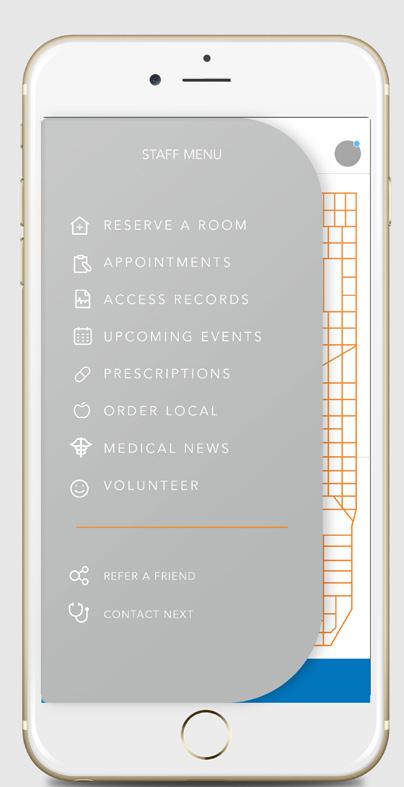

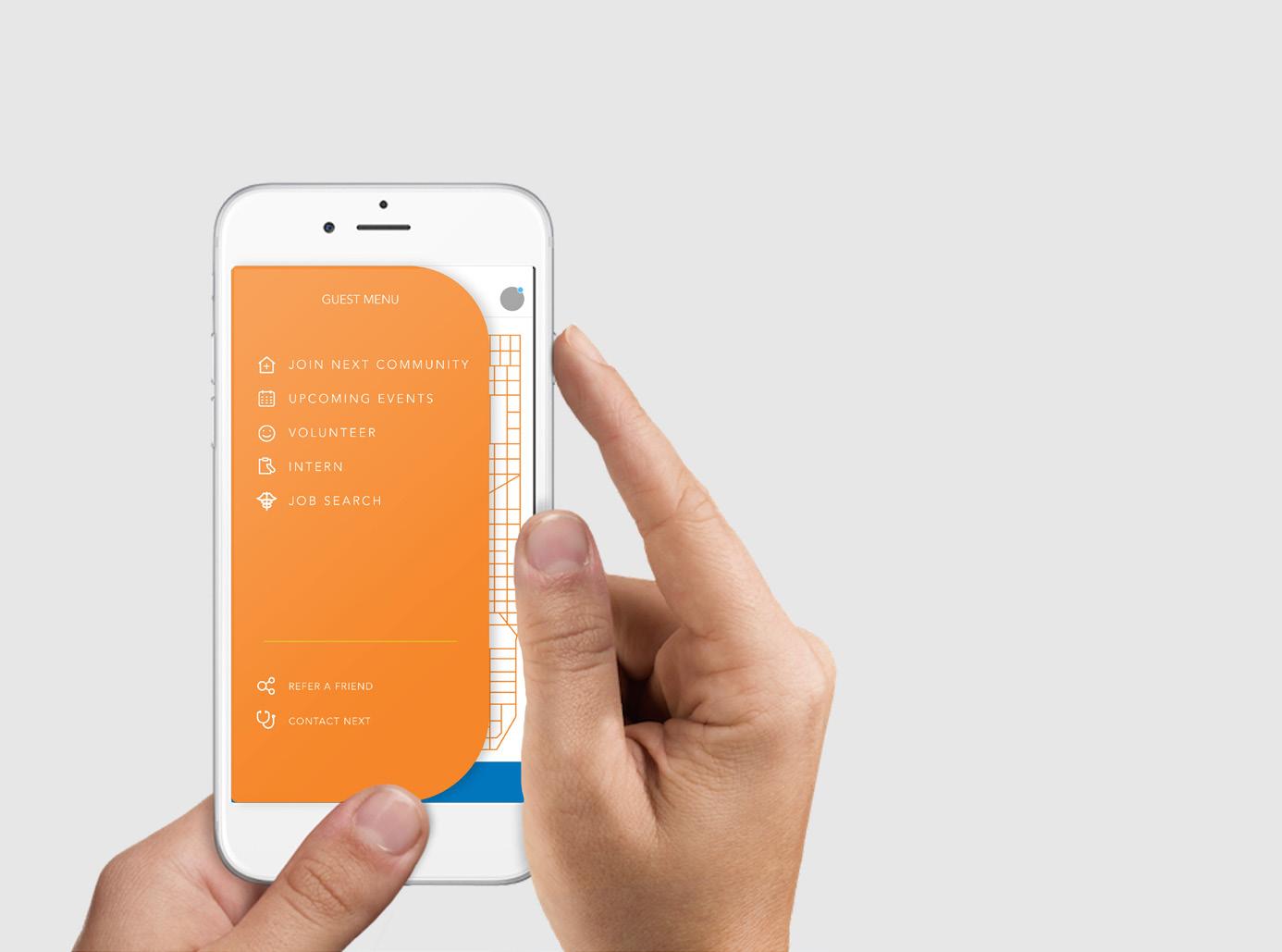

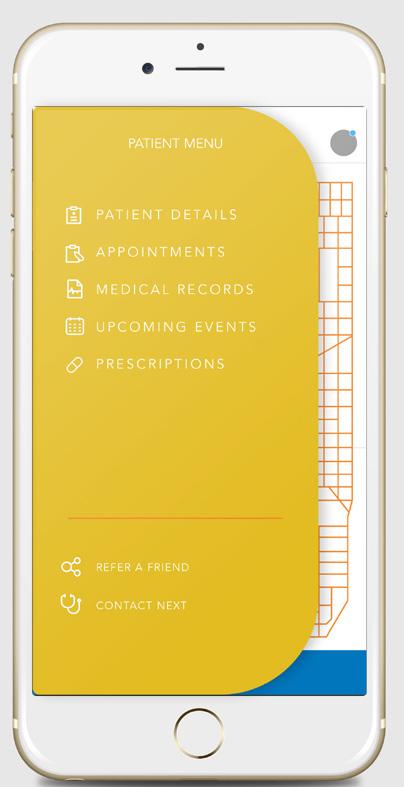

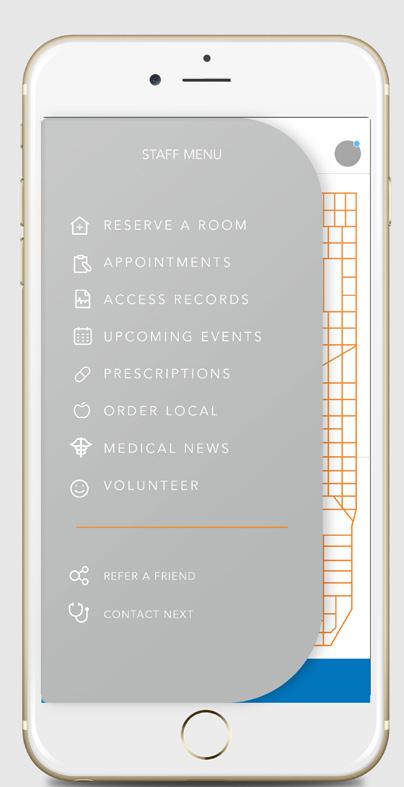

Presenting the NEXT Medical Application, accessible to patients, employees, and guests.

As Steelcase provides the pieces to the puzzle with their advanced furniture products and NEXT will provide the space and services, in order to create a conversation between patient, clinician, and community, there’s one missing component. How to connect them all back together. The application will seamlessly integrate with Steelcase’s technologies, with NEXT’s lively and advanced work culture, as well as the main patient demographic.

The patient would be able to book appointments through the application, and get reminders on upcoming visits.

The patient would also have access to medical records and prescriptions, which will be updated automatically after each visit. The patient can also attend events NEXT will be hosting such as cooking demonstrations.

The clinicians / staff are able to book conference rooms prior to meetings, and can share medical news and technologies through the application. The application will also allow the staff members better access to healthier local food options. It will allow for ordering / catering, listing local and organic vendors nearby. Volunteer opportunities will also be listed and updated weekly.

As a guest user, upcoming public events held in the office will be announced through the application and will allow for registration.

LOGO DEVELOPMENT:

The grid is incorporated within the brand logo, while also being a reinterpretation of the Red Cross, which is associated by many with healthcare. The cross is then used in the design of the reception desk.

Login

View of Reception

Menu, NEXT Application

12

Different User Menus, NEXT Application

1. Exam Rooms 2. Break Out / Collaboration Spaces 3. Acupuncture Room 4. Massage Rooms 5. ADA Unisex Washrooms 6. Water Fountains 7. Nursing Mother / Relaxation Room 8. Medium Conference Room 9. Large Conference Room 10. Laundry Environmental Space 11. Work Cafe 12. Lounge / Breakout Spaces 13. Medical Supply Room 14. Resource Center 15. Open Office FLOOR PLAN LEVEL 1 + MEZZANINE: N 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 1. 2. 3. 4. 4. 5. 5. 2. 7. 6. 2. 8. 9. 25. 24. 28. 27. 29. 30. 26. 22. 22. 20. 20. 21. 19. 18. 17. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 16. 16. 19. 18. 18. 17. 12. 5. 15. 16. Education and Lifestyle Zone 17. Collaboration Spaces 18. Shared Office 19. Exercise / Gym Room 20. Phone / Quiet Room 21. Staff Lockers and Waiting Area 22. Consultation Room 23. Reception Waiting Area 24. Reception Area 25. Reception Desk 26. Records and Transaction Space 27. Self Check-in 28. Main Entrance 29. Staff Entrance 30. Indoor Garden Strip 13

The WELL Building Standard Creating A Resilient Work Place

ideal indoor air quality in order to support the health and well-being of the building users. WATER

Advocate clean water through the integration of proper filtration and regular water testing in order to provide users with safe water.

MIND

Provide a physical environment that optimizes cognitive and emotional health.

LIGHTING

Provide adequate lighting systems that minimize the disruption of the circadian rhythm, while still enhancing productivity and visual acuity.

FITNESS

Integrate exercise and fitness into users’ lifestyles by providing the physical features within the design to promote active and healthy lifestyles.

COMFORT

Create distractionfree, productive and enjoyable indoor environments for occupants.

NOURISHMENT

Encourage healthy eating habits and make fresh, wholesome foods more available.

INNOVATION

Continue education in how interior spaces are contributing to health and wellness of occupants.

A103 1 Reception Desk Elevation 1a A103 2 Reception Desk Elevation 2a A103 3ElReceptionDesk evation3a A103 4 Reception Desk Elevation 4 - a 5 A103 8" 1" 2' 5" 1/2" 2' 1/2" 15' 4" 7' 1/2" 10" 10" 5' 0" 2' 11" 1' 7" 11' 11" 9' 0" 9 -1 Operable swinging door towards the back allows receptionist to enter behind the desk, without disrupting the overall reception desk design. The door is made out of plywood covered in Brite White Formica laminate in matte Kick space underneath reception desk allows protection of the exterior panels from damage. Made out of plywood covered in 909 Black Formica laminate in matte finish. Structural wall allows the top component of the reception desk extra structural support on one end. Will be used surface to display signage systems. Gypsum Wall boards are installed between the recepetion desk area and the medical record room and are painted in Bauwerk Colour Bleached Structural frame behind the recepetion desk is composed on stainless steel framing, where plywood. Counter tops and exterior faces of the reception desk are made out of plywood wrapped in Brite White Formica laminante. This laminate contributes to LEED points, FSC certified wood, Green Guard certified, and contains recycled content. The laminate covering suitable to be used in healthcare Steelcase height-adjustable Air touch desks are provided to the employees in the medical record room to ensure staff have the option of sitting or standing. Lowered part in reception desk is ADA complaint with counter height of 34". Top component of reception desk consists of a steel frame structure wrapped in gypsum board painted in structural frame is suspended from the ceiling and is latched on both ends to structural walls in order to reassure stuctural integrity. Second layer of plywood covered in Brite White Formica laminate is attached on certain panels in order to show integrated graphic symbol. Exposed edges of the second layer of plywood, have integrated LED linear strips that outline the graphic symbol represented in the reception desk design. Remaining counters are transaction height of 42". Bottom base of top component of reception desk contains integrated LED lighting covered with 3Form to create diffused lighting above the counter spaces. 3/16" = 1'-0" 1 Plan -Reception Desk 2 Axon View -Front 7 Cut Axon of Reception Panels 0' 1/2" 0' 2" 2" 5' 8" 3" 1' 7" 0' 2" 12' 0" 9" 10" 1/2" 12' 8" 6' 4" 10 1/2" 1" 1/2" 2' 10" 11' 10 1/2" 6" 12' 0" 10" 9" 1/2" 11 1/2" 2' 11" 7' 9" 1' 7" 4' 1/2" 7" 6' 7 1/2" 2' 1/2" 4' 0" 4' 11 1/2" 4' 10" 12' 0' 1/2" 0' 1/2" 0' 1/2" 6' 7 1/2" 1/2" 4' 4" 2' 11" 7' 7 1/2" 3/16" = 1'-0" 1 Reception Desk Elevation 1 -a 3/16" = 1'-0" 2 Reception Desk Elevation 2 -a 3/16" = 1'-0" 3 Reception Desk Elevation 3 -a 3/16" = 1'-0" 4 Reception Desk Elevation 4 -a 0' 1/2" 0' 2" 3' 6" 3' 6" 12' 0" 9" 4' 10" 1/2" 12' 8" 6' 4" 10 1/2" 1" 1/2" 0' 2' 10" 11' 10 1/2" 12' 0" 4' 10" 3' 6" 9" 1/2" 4' 11 1/2" 9' 1" 9' 1" 6' 7 1/2" 6' 7 1/2" 2' 1/2" 4' 0" 11 1/2" 10" 12' 3' 8" 0' 2" 6' 7 1/2" 1/2" 4' 4" 2' 11" 7' 7 1/2" 3/16" = 1'-0" 1 Reception Desk Elevation 1 -a 3/16" = 1'-0" 2 Reception Desk Elevation 2 -a 3/16" = 1'-0" 3 Reception Desk Elevation 3 -a 3/16" = 1'-0" 4 Reception Desk Elevation 4 -a 0' 1/2" 3' 6" 9" 1/2" 4' 10 1/2" 5' 1" 4' 9 1/2" 0' 1" 11' 10 1/2" 12' 0" 4' 10" 3' 6" 9" 1" 6' 1/2" 6' 1/2" 7 1/2" 4' 0" 2' 9" 11 1/2" 10" 12' 3' 8" 0' 2" 0' 1/2" 0' 1" 1/2" 0' 1" 0' 1" 1/2" 0' 1/2" 0' 1/2" 0' 1/2" 1/2" 0 1/2" 0' 1/2" 1/2" 6' 1/2" 6' 1/2" 2' 9" 2" 10" 6" 3' 3 1/2" 4' 4" 2' 11" 12' 0" 7' 1/2" 10' 1/2" 0' 11" 2' 10" 1' 10" 3/16" = 1'-0" Reception Desk Elevation 1 -a 3/16" = 1'-0" Reception Desk Elevation 2 -a 3/16" = 1'-0" 3 Reception Desk Elevation 3 -a 3/16" = 1'-0" 4 Reception Desk

4 -a 3/16" = 1'-0" 5

1 AIR

Elevation

Reception Desk Section

Create

14

The above ceiling element consists of square felt tiles installed within a steel grid structure, in order to control acoustics in more concentrated areas. The tiles are in bright colors that bring energy to the open office and work cafe areas.

View of Work Cafe

Axon of Open Office and Work Cafe

Elevation of Cafe Wall

View of Work Cafe

Axon of Open Office and Work Cafe

Elevation of Cafe Wall

15

16

View of Self-Check-In Stations

View of Open Office Space 17

Art Made Gallery, Ithaca NY

Art Made Gallery is a three storey building that encompasses a two storey exhibition space along with an apartment on the third floor. Located in downtown Ithaca, NY, the tenants are seeking to exhibit Ghadah Al Kandari’s work, a Kuwaiti based artist who uses a repeating subject in her works, whom she refers to as “Eve”. The gallery draws from her art by selecting bright contrasting colors and overlapping geometries to distinguish key spaces within the exhibit as well as aid in way finding. Her works are displayed in chronological order upon entering the space, starting by a display of her sketches and water colors, then paintings, and ending with her three

dimensional art, as though a visual narration of the phases in which Eve was created. Each display is distinguished by different colored linear strips placed to indicate to the user that he / she is entering a new phase of Eve’s creation. Placing this art gallery within a university district that has two strong programs in the Arts, will mean that the gallery will be constantly revisited by both university students, incoming students, professors, and local families. With both Ithaca College and Cornell University in close proximity, students are able to discover the changing exhibits within Art Made Gallery throughout their university careers.

18

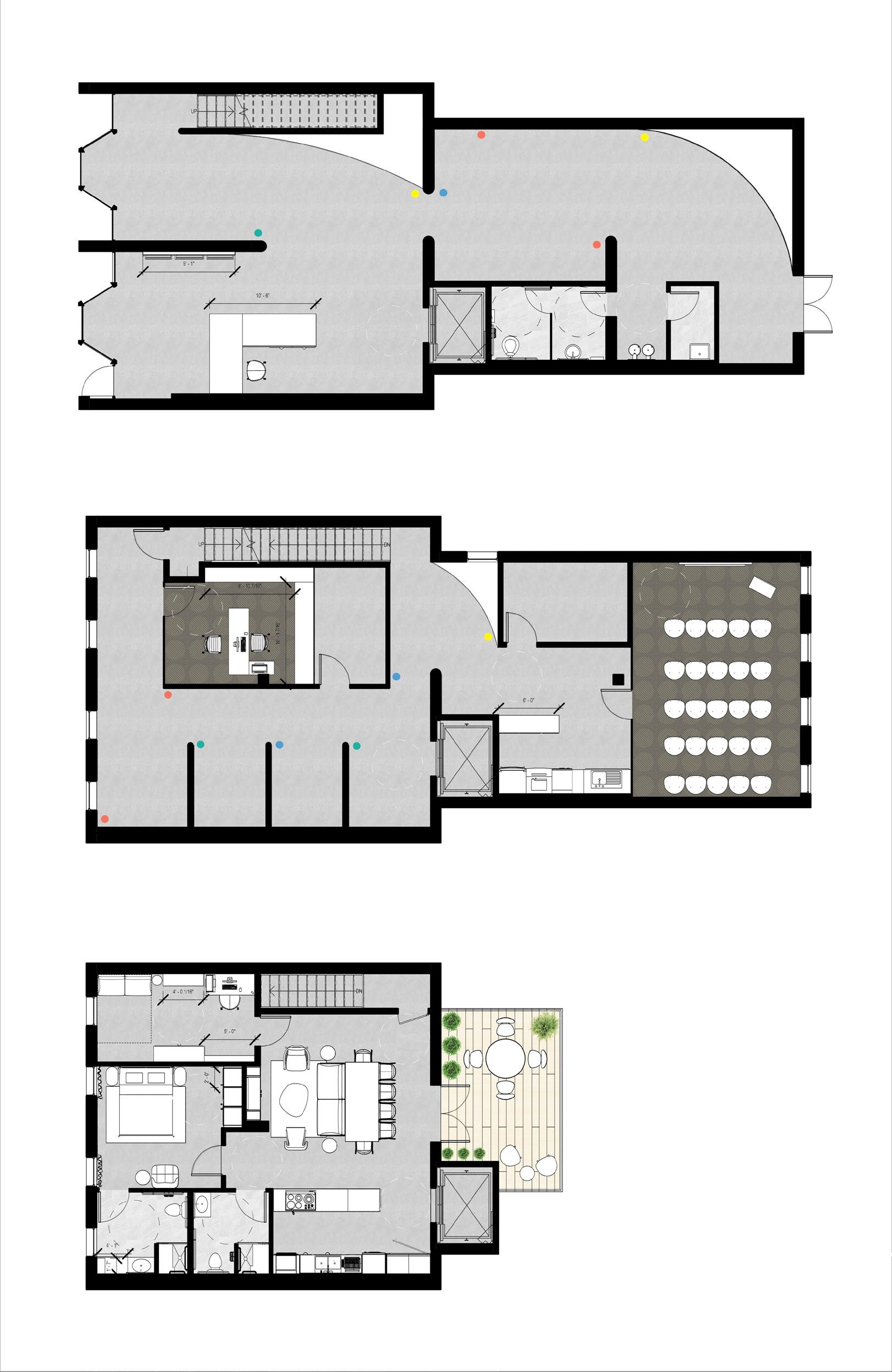

GROUND FLOOR FIRST FLOOR SECOND FLOOR Gallery Space Restroom + Utility Space Office Space Commercial Kitchen Lecture Space Bedroom Space Kitchen + Living Space DIAGRAM LEGEND N ART MADE GALLERY + = A M 19

Colorful linear strips are scattered amongst the gallery in order to allow a user to easily identify what he or she is looking at. Green strips indicate the artist’s first phase with sketching. Blue strips indicate the artist’s water color collection that began as sketches. The red strips indicate the artist’s canvas paintings. And lastly, the yellow strips indicate the artist’s take on Eve threedimensionally. The user is also aided by visual documentation as a brochure based on each color strip is provided at the reception area.

Main Entrance Literature Display Area Reception Desk Gallery Bathroom Service Sink Drinking Fountains Egress Exit Elevator Gallery Kitchen Executive Office Lecture Storage Lecture + Presentation Room Art Work Storage Living Room + Dining Room Kitchen 3/4 Bath Master Bedroom + Bath Guest Bedroom / Den Laundry Room Outdoor Deck / Patio

N 20

KITCHEN AXON : WITH UNIVERSAL DESIGN FEATURES

Counter edges are rounded to avoid user discomfort, while counter tops have varying stone patterns and colors to visually differentiate the working surface from the counter shell.

This 30” fridge from BOSCH comes with a built-in drawer freezer at the bottom. This allows easy access. It also has a low energy consumption rate and is Energy Star qualified.

The kitchen sink faucet is part of the Simplice Collection from Kohler. This lever style faucet is user friendly and meets the water saving requirements for the California Energy Commission, CALGreen, and Colorado SB 14-103.

Top cabinets are attached to an automated track system that allows the user to lower the shelves when needed. While LED strip lights are provided under the cabinets to provide task lighting.

The counter shell is made out of QuartzStone, in Alabaster White. 94% of QuartzStone contents come from crushed waste left over in quarries.

The counter base/toe-kick is made out of a Durat surface material. Durat is 100% recyclable, and is made from recycled post industrial plastics. The strong contrasting color allows the user to differentiate between the toe-kick and open space.

Along with raised appliances, the space under the sink is left open, to allow wheelchair users to roll up to the sink and perform tasks without facing obstructions.

The edge banding of the cabinet doors are both rounded and highlighted in a jade green, while the “D” style handles are painted red. This allows the user to easily locate the handles and distinguish the cabinet corners to limit user discomfort.

21

22

View of the Gallery Space, Ground Floor

View of the Apartment Bedroom, Second Floor 23

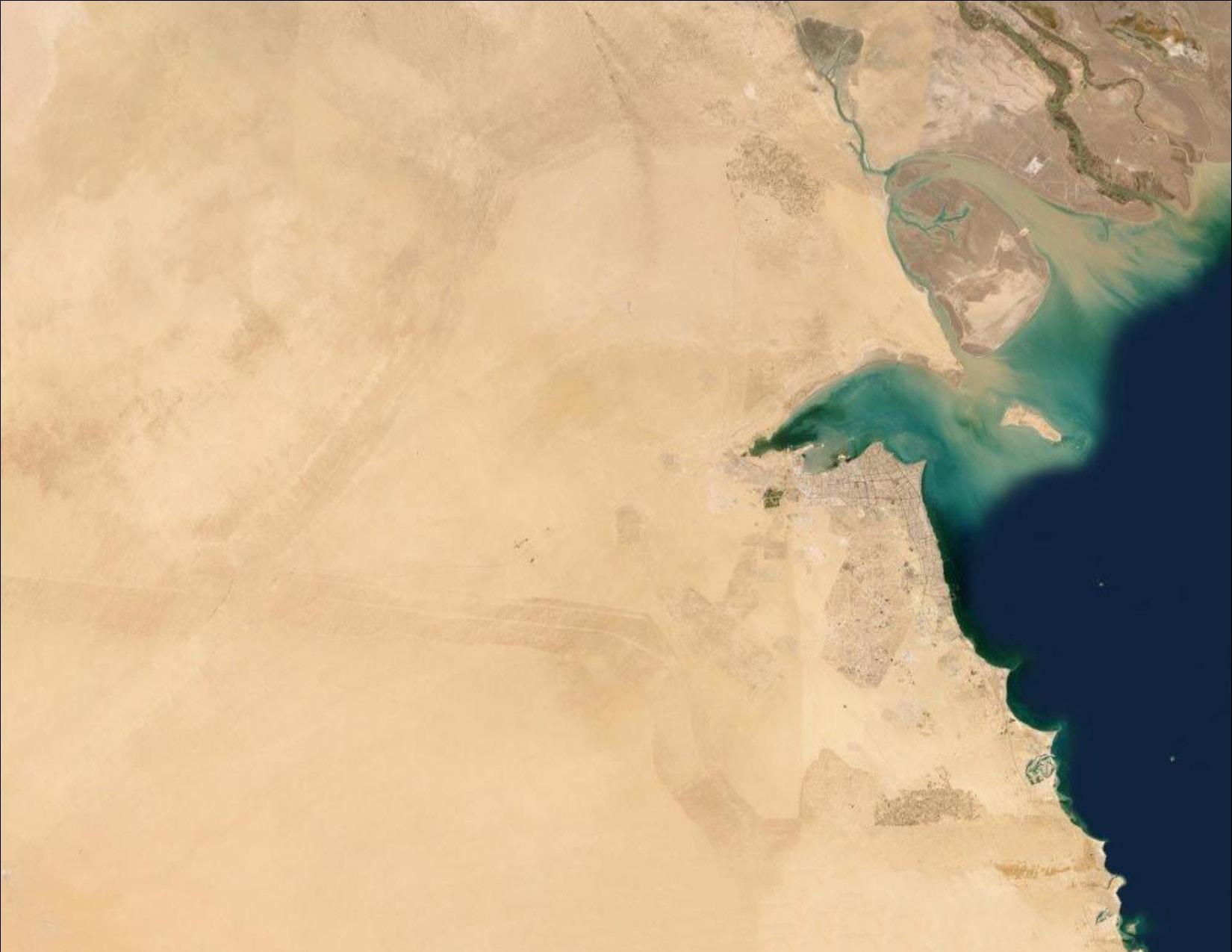

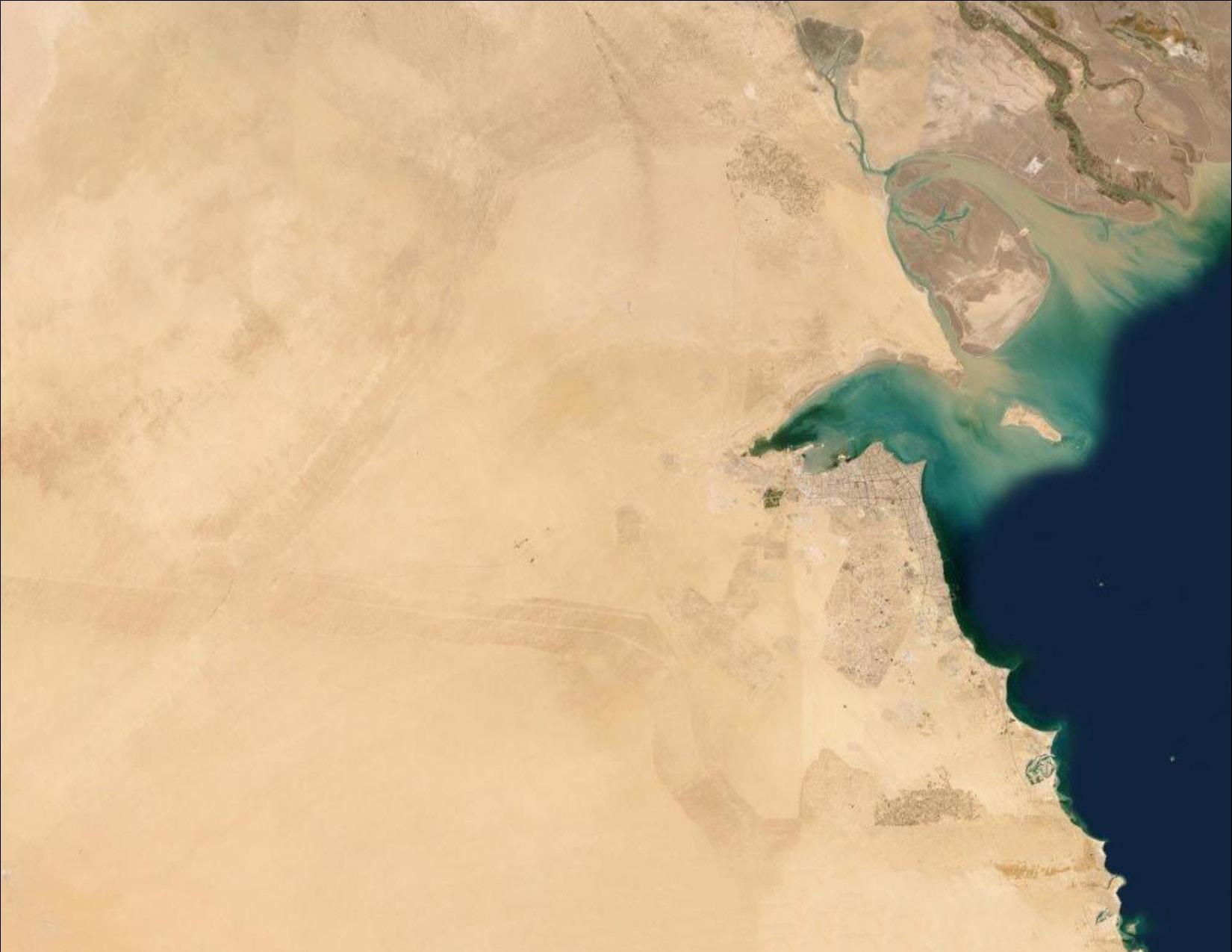

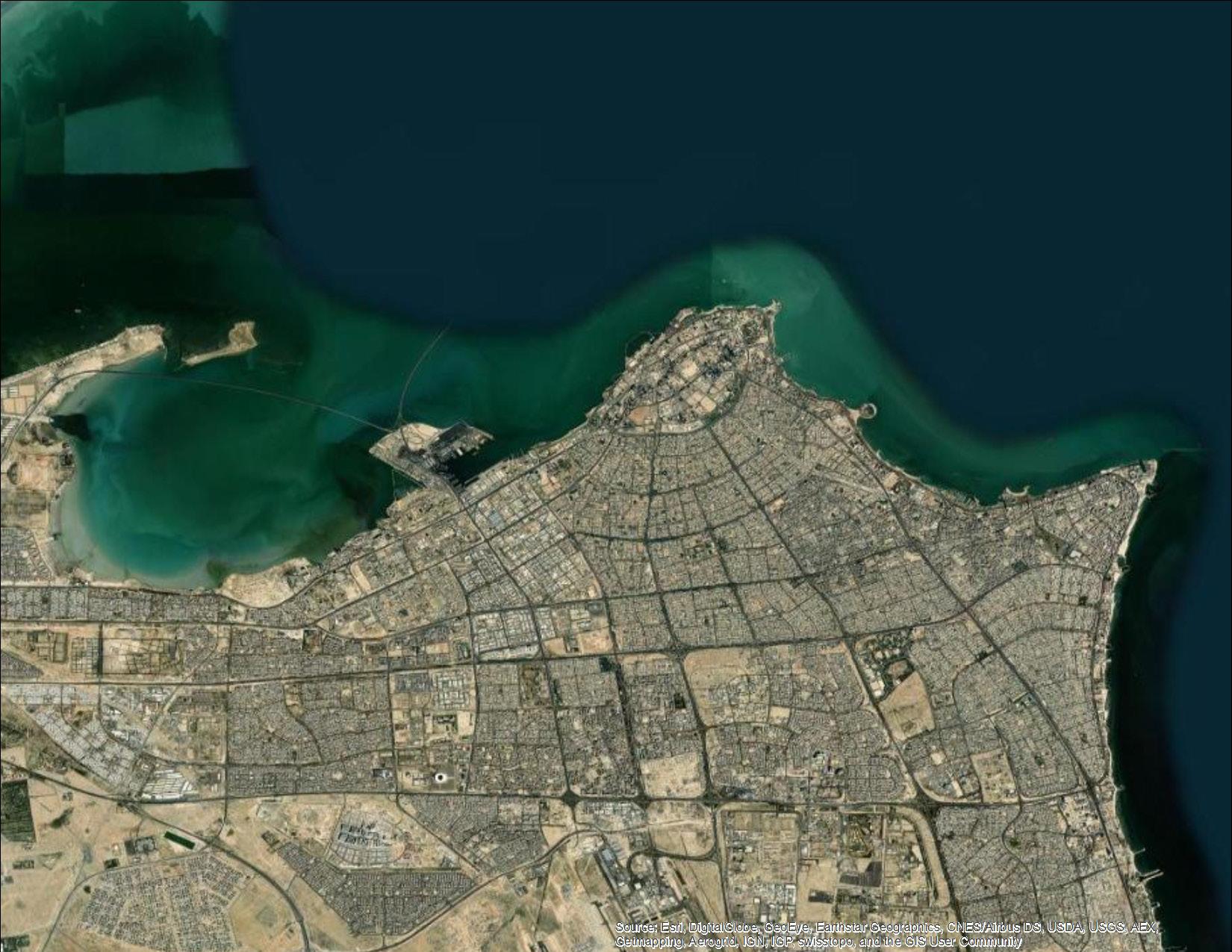

The Dust Up: Adapting Kuwait’s Civic Infrastructure to SDS

This thesis aspires to redevelop public infrastructural spaces in Kuwait to interact with the natural phenomena and challenges of local sand and dust storms (SDS) that disrupt the city, by embracing these processes to create unique social and ecological relationships for the city and its people.

The research challenges the existing ‘greening’ strategies that arose from Kuwait’s 1952 masterplan developed by the foreign practice of Minoprio Spencely and Macfarlane. The work specifically explores the neighborhood parks and highway

interchange networks. Today these exist as static landscapes that require excessive irrigation and resources to maintain their ‘green’ image, while disregarding the cultural and climatic context.

As they currently stand, these networks have proven to fail at the scale of the ecological process, neither designing for or against these storms, but instead completely ignoring them.

*Advised by Craig Douglas, Thesis 2021-2022

24

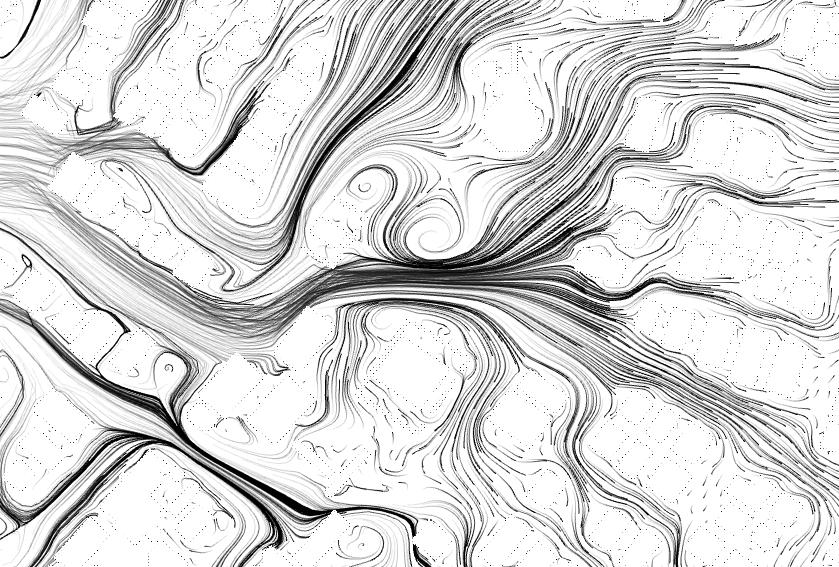

These storms are massive, traveling over multiple territories and seas, they can be seen as both a destructive and creative force, both unstoppable. The sand and dust storms are coming in from the mesopotamian flood plain, western desert of Iraq, Ahwar marshes, Nafud Desert, Ahwaz Iran, the Empty Quarter desert, Bandar Lenga, Iran, and Hurmuz, including local sand from Kuwait’s borders.

They’ve shaped Kuwait’s landscape over the years, and have always been a creative force in its topographic history, resulting in a shifting sand corridor leaving behind active sand sheets and dunes.

Kuwait / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا Saudi Arabia / ﺔﯾدﻮﻌﺴﻟا Iraq /قاﺮﻌﻟا Iran / ناﺮﯾا United Arab Emirates / تارﺎﻣﻹا Bahrain / ﻦﯾﺮﺤﺒﻟا Qatar / ﺮﻄﻗ Oman / نﺎﻤﻋ Riyadh / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا Baghdad / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا Shiraz / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا Esfahan / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا Al Manama / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا Doha / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا Sharjah / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا Ahvaz / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا Bandar Lengeh / ناﺮﯾا Hormuz / ناﺮﯾا Ahvar Marshes / ناﺮﯾا Western Desert of Iraq / ناﺮﯾا Al Nufud Al Kabir / ناﺮﯾا Empty Quarter / ﺔﯾدﻮﻌﺴﻟا Mesopotamian Flood Plain / ﺔﯾدﻮﻌﺴﻟا

¬ MILES 0 10 20 30 ACTIVE SAND SHEETS AND SAND DUNES SHIFTING SAND CORRIDOR KUWAIT MUHAFAZAT (DISTRICTS) Kuwait / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا Saudi Arabia / ﺔﯾدﻮﻌﺴﻟا Iraq /قاﺮﻌﻟا Iran / ناﺮﯾا Al - Ahmadi Al - Jahra Hawalli Al - Asimah Al - Farwaniya Mubarak al - Kabeer Al - Jahra

25

CLASSIFICATION OF BLOWING DUST IN KUWAIT

Total Amount of Sand Removal Total Cost of Sand Removal Cost for Sand Removal per m³ Settlements (m³) (USD) (USD) Oil Facilities 347,310 993,862 2.862 Main Highways 2,651,431 2,141,757 0.81 Power Stations 160,600 955,452 5.95 Military Bases 1,320 78,694 59.62 Average 790,165.13 1,042,441 1.32 Total 3,160,660.52 4,169,766 -

25m 50m 3m IF AN OLYMPIC SWIMMING POOL WAS FILLED WITH SAND VOLUME: 88,000 m³ COST FOR SAND REMOVAL: $ 116,160 TYPE 1 LIGHT 15-24 MPH

Table

1:

Annual amount and cost for removing encroached sand from main facilities and infrastructures in Kuwait during 2013. Source: KISR, Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research

TYPE 2 MILD 25-34 MPH TYPE 5 MODERATE 35-44 MPH TYPE 7 STRONG 45-54 MPH TYPE 9 SEVERE 55-65 MPH 0 10,000 20,000 30,000 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 11 12 13 22 23 24 25,000 15,000 5,000 MAX DUST HEIGHT (FEET) USUAL DURATION (HOURS) 26

Why does this matter? As of right now, Kuwait municipality known as the Baladiya contracts private companies to clear infrastructure from deposited sands, without monitoring where the sand is dumped. Although the majority admitted to dumping in the nearest open empty field. This is no cheap job.

While the parks too ignore this phenomena and after a SDS event need to be manicured back to their original state.

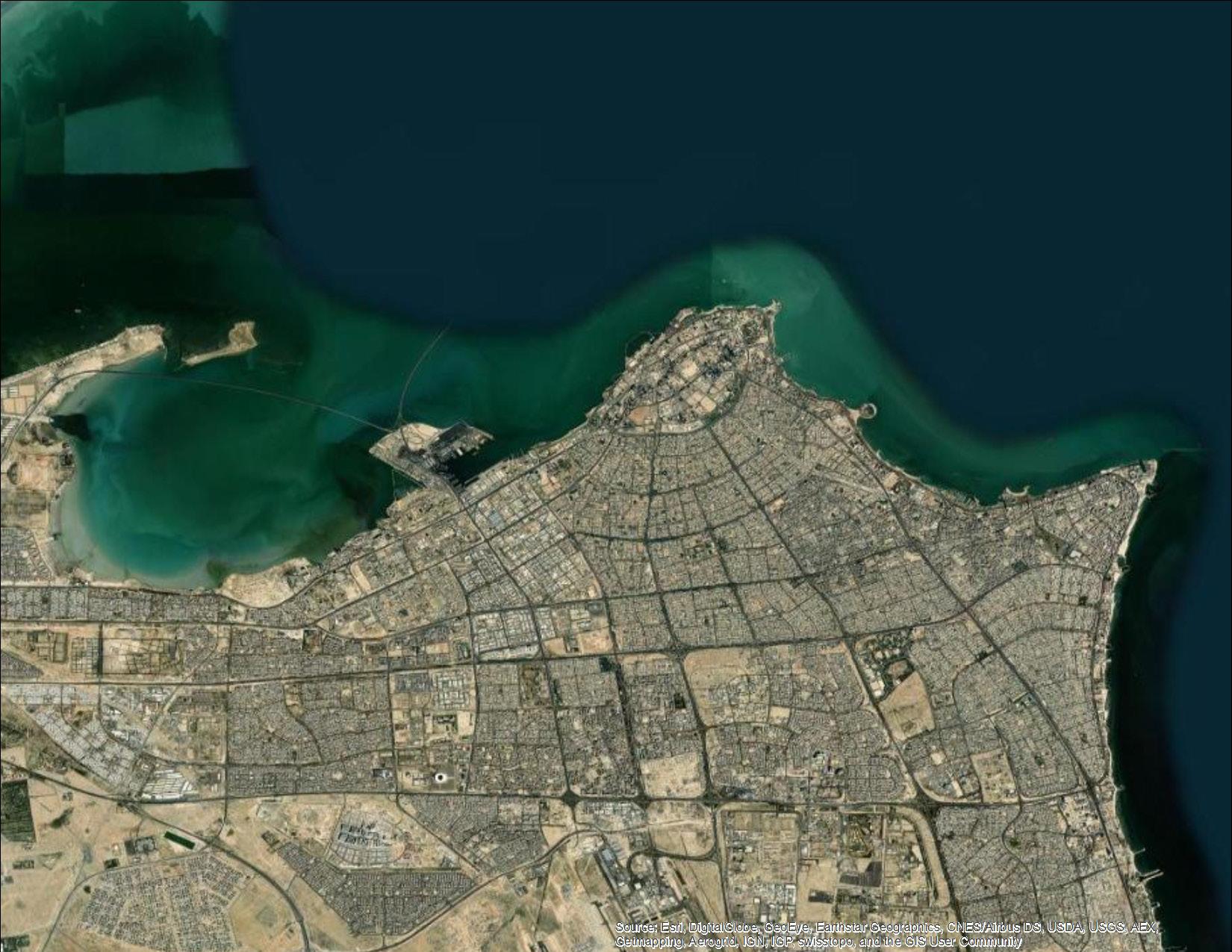

Zooming into the urbanized portion of Kuwait, these two greening networks are mapped; both the public parks that were introduced to green the neighborhoods and the highway interchange network that as a result of the introduction of highways also became a greening strategy for the city.

To tackle this topic, I am redesigning two sites within the green networks. Selecting individual units as prototypes that can be embedded back into the larger system.

Uploaded photo of Farwaniya Public Park, Kuwait. Source: Google Earth Uploaded Images

¬ HIGHWAY INTERCHANGES HIGHWAY BELTS ROADS PUBLIC PARKS NEIGHBORHOODS KUWAIT LAND MILES 0 1 2 3 Kuwait Bay / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا نﻮﺟ Kuwait / ﺖﯾﻮﻜﻟا Abdullah Al-Salem Public Park / ﻢﻟﺎﺴﻟا ﷲﺪﺒﻋ ﺔﻘﯾﺪﺣ Fifth Ring Road Interchange / ﺲﻣﺎﺨﻟا ﺮﺋاﺪﻟا ﻊﻃﺎﻘﺗ

Image of road closure due to sand deposit removal in highway road, Kuwait, April 2021. Source: Arab Times

27

JAN رياني FEB رياربف MAR سرام APR ليربا MAY ويام JUN وينوي JUL ويلوي AUG سطسغأ SEP ربمتبس OCT ربوتكأ NOV ربمفون DEC ربمسيد SUSPENDED DUST قلاع رابغ RISING DUST رياطتم رابغ DUST STORM ةيبارت ةفصاع TEMPERATURE °C ةرارحلا ةجرد 50°C 40°C 30°C 20°C 10°C 0°C JAN رياني FEB رياربف MAR سرام APR ليربا MAY ويام JUN وينوي JUL ويلوي AUG سطسغأ SEP ربمتبس OCT ربوتكأ NOV ربمفون DEC ربمسيد DUST STORM ةيبارت ةفصاع RISING DUST رياطتم رابغ SUSPENDED DUST قلاع رابغ 0°C 10°C 20°C 30°C 40°C 50°C 60°C AVERAGE ANNUAL HIGH AND LOW TEMPERATURES 28

10°C 20°C 30°C 40°C 50°C N لامشلا E قرشلا S بونجلا W برغلا 60°C 70°C 80°C 3PM 12PM 9AM 6AM 6PM 3PM 12PM 9AM 3PM 12PM 9AM 6AM JUNE SOLSTICE DECEMBER SOLSTICE TODAY N لامشلا NE لامشلا يقرشلا E قرشلا SE بونجلا يقرشلا S بونجلا SW بونجلا يبرغلا W برغلا NW لامشلا يبرغلا 10.0% 8.0% 6.0% 4.0% 2.0% 0.0% 15-20 mph 10-15 mph 7-10 mph 5-7 mph 2-5 mph 20+ mph WIND SPEED 29

FLOWERING & FRUIT SEASON OF SELECT NATIVE AND ORNAMENTAL PLANT SPECIES RHANTERUM EPAPPOSUM

M O R U S ALBA توتلا ةرجش CARDUUS PYCNOCEPHALUS ناسللا RHANTERUM EPAPPOSUM جف ر ع RUMEX VESICARIUS ضامح MELILOTUS INDICUS قرذلا GYNANDRIRIS SISYRINDIUM لصنع AEANUAL ATANORCUM اليعضيد OICENES G L A U C U S ر اجرج لا CONVOLUULUS CEPHALOPODUS ىماخرلا AIDROC AXYM بمبر XINEOHP AREFILYTCAD نخلة HORWODIA DICKSONIA يمازخ HELIOTROPIUM BACCIFERU M م را رم حيلس LLAC I G ONUM POLYGONOID E S ى أرط E R AIRACU JAN رياني FEB رياربف MAR سرام APR ليربا MAY ويام JUN وينوي JUL ويلوي AUG سطسغأ SEP ربمتبس OCT ربوتكأ NOV ربمفون DEC ربمسيد

جفرع

ضامح

قرذلا

SISYRINDIUM لصنع

MICRONATA ديضعيلا

PYCNOCEPHALUS ناسللا

CEPHALOPODUS ىماخرلا SENECIO GLAUCUS راجرجلا CORDIAMYXA ربمب Phoenix

ةلخن MORUS ALBA توتلا ةرجش HORWODIA DICKSONIA يمازخ

BACCIFERUM مارمر

POLYGONOIDES ىطرأ ERUCARIA حيلس 30

RUMEX VESICARIUS

MELILOTUS INDICUS

GYNANDRIRIS

LAUNAEA

CARDUUS

CONVOLUULUS

dactylifera

HELIOTROPIUM

CALLIGONUM

D N D N D N D N D N D N D N D N D N D N D N D N D N D N AFTERNOON TEA ىحضلا ياش DOG WALKING بلكلا يشم GRASS LOUNGING PICNIC ةهزنلا SOCCER مدق ةرك GRILLING يوش BIKING تاجاردلا بوكر VOLLEYBALL ةرئاط ةرك CRICKET BASKETBALL ةلس ةركDIWANIYA ةيناويد KASHTA هتشك WALKING PATH ةشمم PLAY GROUND باعلأ بع ل م JAN رياني FEB رياربف MAR سرام APR ليربا MAY ويام JUN وينوي JUL ويلوي AUG سطسغأ SEP ربمتبس OCT ربوتكأ NOV ربمفون DEC ربمسيد DAY AND NIGHT OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES IN KUWAIT GRASS LOUNGING PICNIC ةهزنلا SOCCER مدق ةرك GRILLING يوش BIKING تاجاردلا بوكر DOG WALKING بلكلا يشم CRICKET VOLLEYBALL ةرئاط ةرك BASKETBALL ةلس ةرك DIWANIYA ةيناويد AFTERNOON TEA ىحضلا ياش KASHTA هتشك WALKING PATH ىشمم PLAY GROUND باعلأ بعلم DAY TIME NIGHT TIME 31

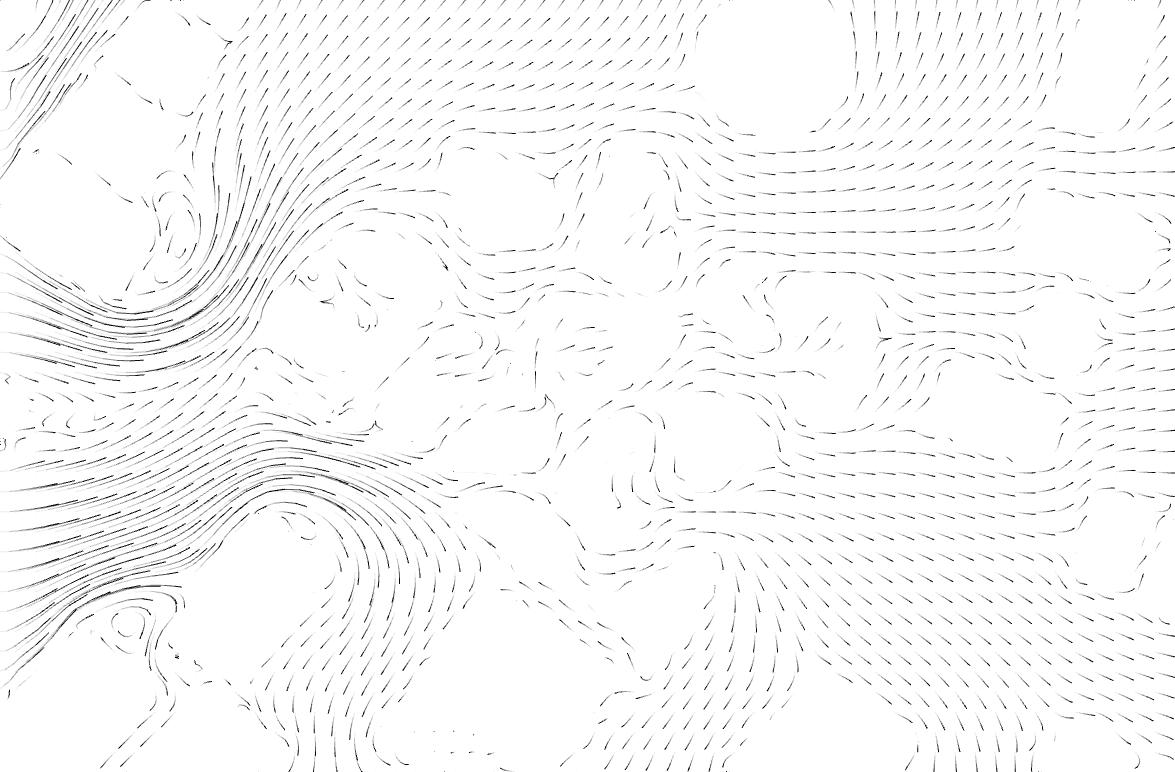

A loose mound of sand would continually fluctuate in shape throughout the months based on the seasonal winds in Kuwait.

MONTHLY NON STATIONARY DUNE MOVEMENT

N لامشلا NE لامشلا يقرشلا E قرشلا SE بونجلا يقرشلا S بونجلا SW بونجلا يبرغلا W برغلا NW لامشلا يبرغلا

JAN رياني FEB رياربف MAR سرام APR ليربا MAY ويام JUN وينوي JUL ويلوي AUG سطسغأ SEP ربمتبس OCT ربوتكأ NOV ربمفون DEC ربمسيد

32

But that same loose mound of sand anchored by a nabkha plant will maintain its overall shape as the plant stations the dune in one position.

MONTHLY STATIONARY NABKHA MOVEMENT

Nabkhas are the only dune type considered stationary as they are anchored by plants that are able to trap encroaching sand. They are extremely common in Kuwait’s deserts as the predominant winds are coming in from one direction, North-West. They are also referred to as coppice dunes, phytogenic mounds or hillocks. As the plant grows, it is able to capture more mobile sand. These micro-ecosytems act as seed banks, habitats for small insects, rodents, reptiles, all while providing shade for larger animals.

N لامشلا NE لامشلا يقرشلا E قرشلا SE بونجلا يقرشلا S بونجلا SW بونجلا يبرغلا W برغلا NW لامشلا يبرغلا

JAN رياني FEB رياربف MAR سرام APR ليربا MAY ويام JUN وينوي JUL ويلوي AUG سطسغأ SEP ربمتبس OCT ربوتكأ NOV ربمفون DEC ربمسيد

33

PLANT: SALICORNIA SINUS-PERSICA

HABITAT: SABKHA

NABKHA SIZE: SMALL

AVG. SAND TRAPPED: 0.06m³

PLANT: LYCIUM SHAWII

HABITAT: DESERT

NABKHA SIZE: LARGE

AVG. SAND TRAPPED: 1.18m³

PLANT: NITRARIA RETUSA

HABITAT: SABKHA

NABKHA SIZE: LARGE

AVG. SAND TRAPPED: 1.99m³

PLANT: HALOXYLON SALICORNICUM

HABITAT: DESERT

NABKHA SIZE: LARGE

AVG. SAND TRAPPED: 1.26m³

PLANT: TAMARIX APHYLLA

HABITAT: SABKHA

NABKHA SIZE: LARGE

AVG. SAND TRAPPED: 1.05m³

PLANT: PANICUM TURGIDUM

HABITAT: DESERT

NABKHA SIZE: LARGE

AVG. SAND TRAPPED: 0.95m³

PLANT: RHANTERIUM EPAPPOSUM

HABITAT: DESERT

NABKHA SIZE: MEDIUM

AVG. SAND TRAPPED: 0.19m³

PLANT: ASTRAGALUS SIEBERI

HABITAT: DESERT

NABKHA SIZE: MEDIUM

AVG. SAND TRAPPED: 0.19m³

PLANT: CITRULLUS COLOCYNTHIS

HABITAT: DESERT

NABKHA SIZE: LARGE

AVG. SAND TRAPPED: 1.12m³

PLANT: CYPERUS CONGLOMERATES

HABITAT: DESERT

NABKHA SIZE: MEDIUM

AVG. SAND TRAPPED: 0.19m³

PLANT: HALOCNEMUM STROBILACEUM

HABITAT: SABKHA

NABKHA SIZE: SMALL

AVG. SAND TRAPPED: 0.06m³

A large majority of Kuwait’s native species are excellent at trapping encroached sand. Diagrammed above are the most successful native species at trapping large volumes of sand.

34

TRAPPED ENCROACHED SAND BY NABKHA FORMING NATIVE SPECIES

141cm 60cm 290cm 350 296cm 444cm 305cm 84cm 20cm 89cm 259cm 188cm 32cm 41cm 170cm 369cm 159cm 223cm 303cm 180cm 330cm 440cm 261cm.62 80cm 42cm 52cm 116cm 146cm 78cm 250cm 161cm 126cm 247cm 230cm 110cm 170.00 276cm 328cm 230cm 16cm 27cm 65cm 66cm 53cm 70cm 135cm 96cm 85cm 105cm 150cm 23cm 33cm 37cm 131cm 408cm

35

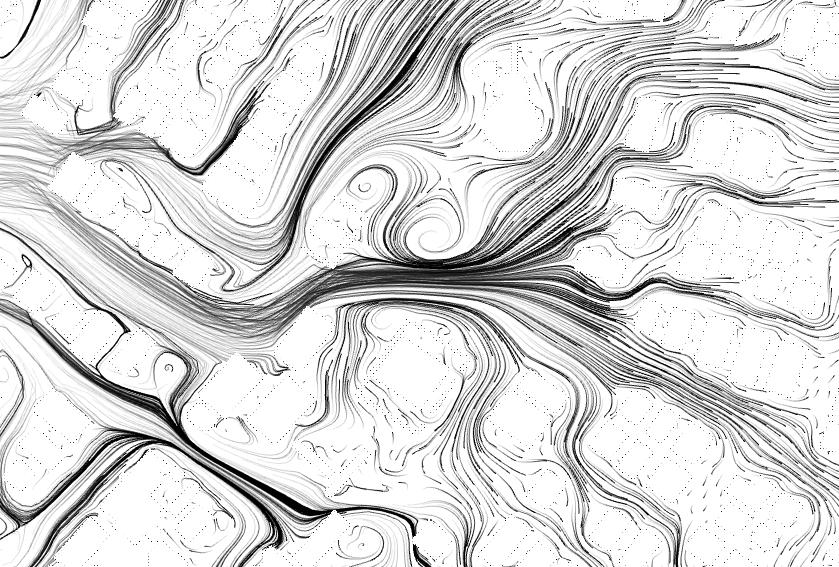

N لامشلا NE لامشلا يقرشلا E قرشلا SE بونجلا يقرشلا S بونجلا SW بونجلا يبرغلا W برغلا NW لامشلا يبرغلا AL HAJERY WEDDING HALL SHADED PLAYGROUND ELECTRICAL BUILDING SINGLE UNIT HOUSE SINGLE UNIT HOUSE ABDULLAH AL-SALEM PARK FATIMA MOSQUE SANA’A STREET 0’ 20’ 40’ 100’ KNPC GAS STATION ABDULLAH AL SALEM PARK FATIMA MOSQUE ABDULLAH AL SALEM DISTRICT SANA’A STREET لامشلا NE يقرشلا E قرشلا SE بونجلا يقرشلا S بونجلا SW بونجلا يبرغلا W برغلا AVERAGE YEARLY WIND FLOW IN SITE لامشلا يبرغلا 36

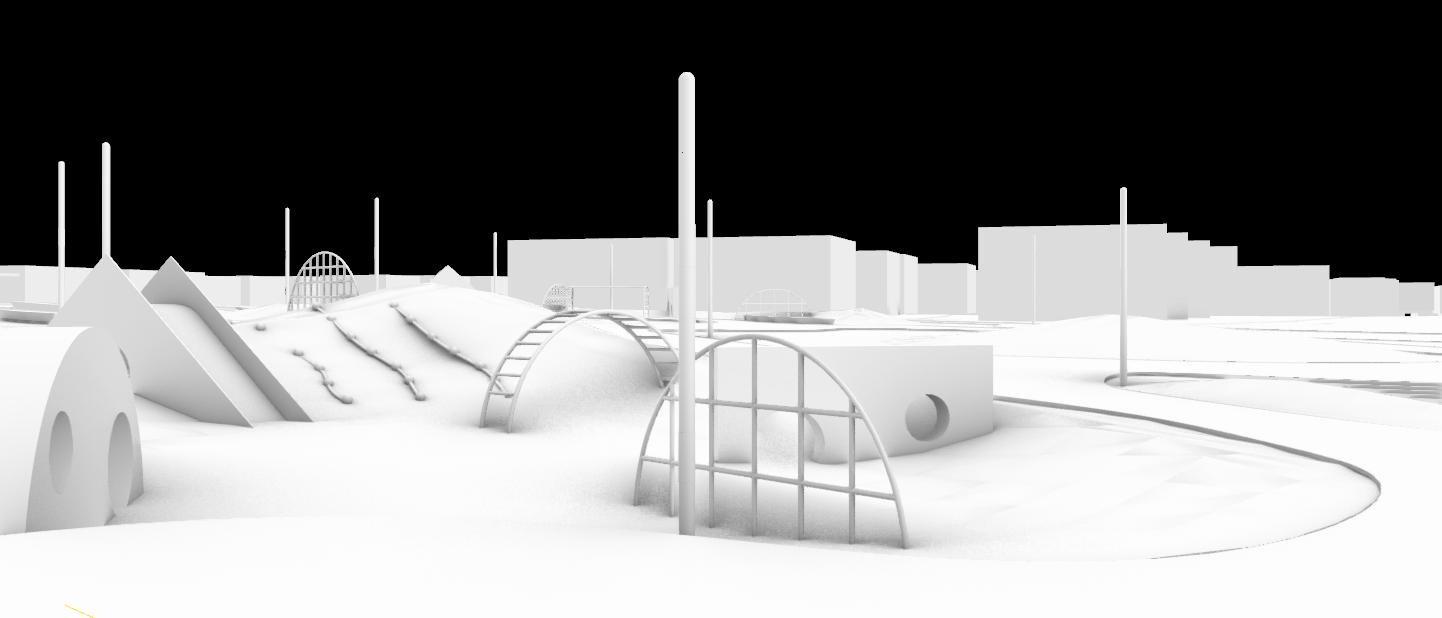

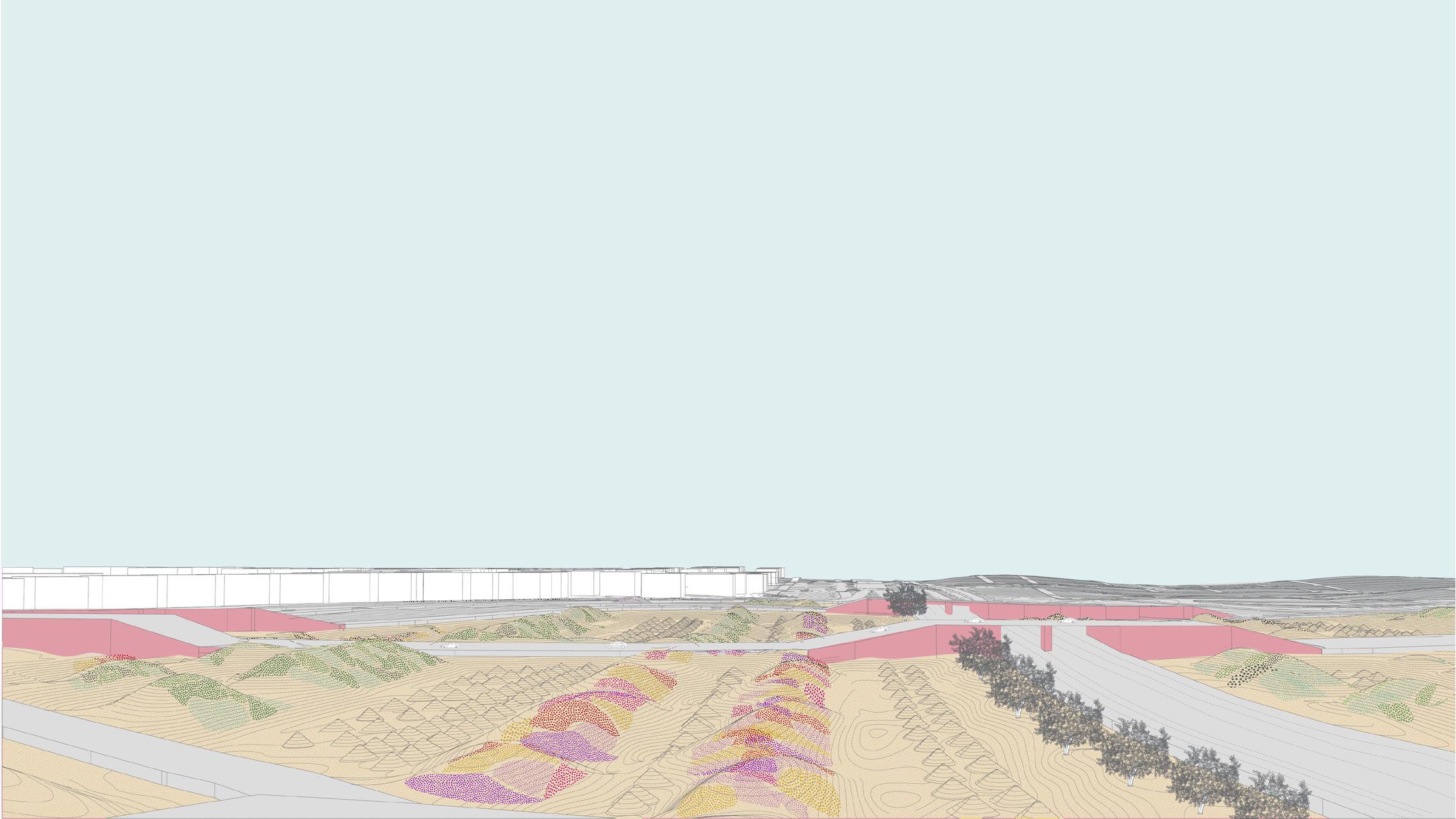

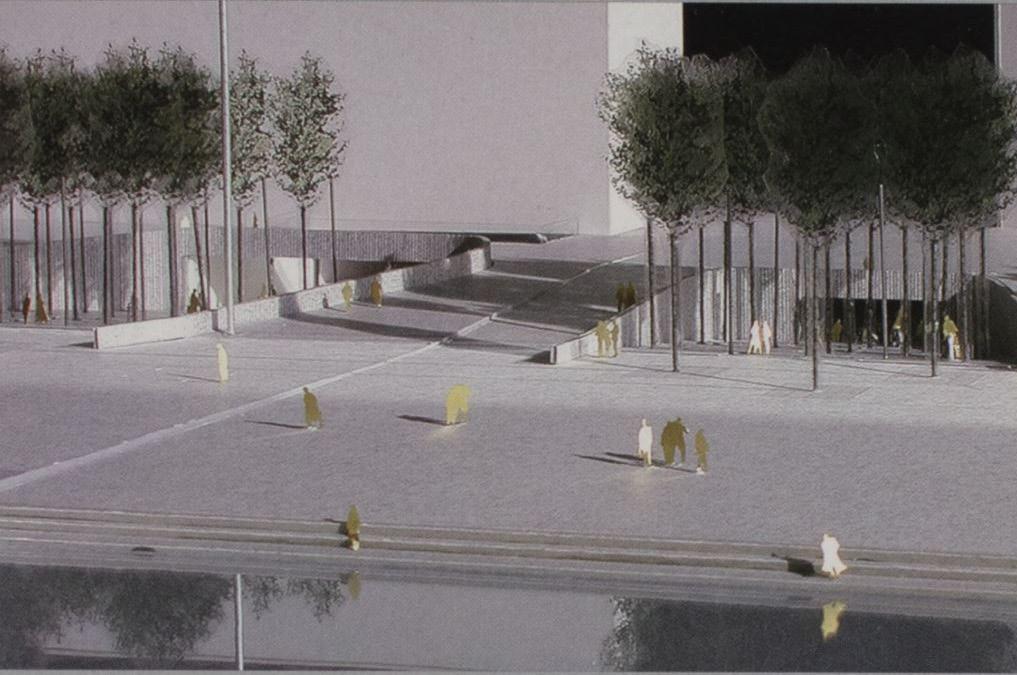

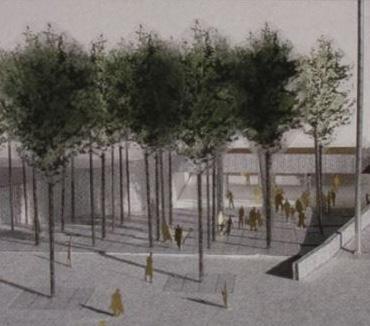

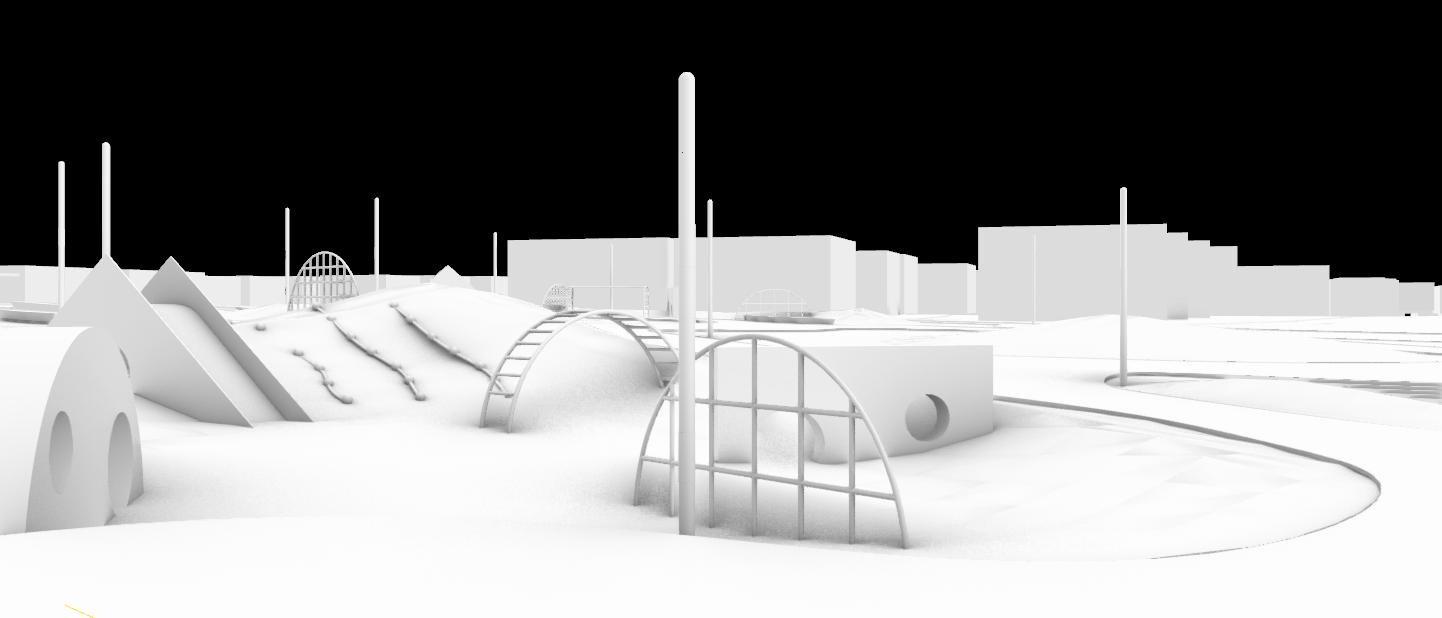

For the neighborhood park, I propose creating a series of mounds, some completely stationary, while others anchored by nabkha planting allowing the sand mounds to drift depending on the directionality of the seasonal winds. Mounds are followed by a depression in the ground, housing park programs in order to collect sinking cool air, while hot air rises and passes.

N لامشلا NE لامشلا يقرشلا E قرشلا SE بونجلا يقرشلا S بونجلا SW بونجلا يبرغلا W برغلا NW لامشلا يبرغلا GATHERING SPACE / GRILLING OPEN PLAYGROUND PICNIC / KASHTA MOUND PARK ENTRANCE 4 OPEN PLAYGROUND FATIMA MOSQUE ENTRANCE 0’ 20’ 40’ 100’ PARK ENTRANCE 1 PARK ENTRANCE 2 GATHERING SPACE ADA ACCESSIBLE PLAYGROUND WALKING / BIKING PATH PARK ENTRANCE 3 INTIMATE GATHERING SPACE EXISTING PARKING EXISTING PARKING EXISTING PARKING THE PARK CONCEPT 37

ABDULLAH AL-SALEM PARK : EXISTING PLAN ABDULLAH AL-SALEM PARK : PROPOSED PLAN WITH PLANTING 38

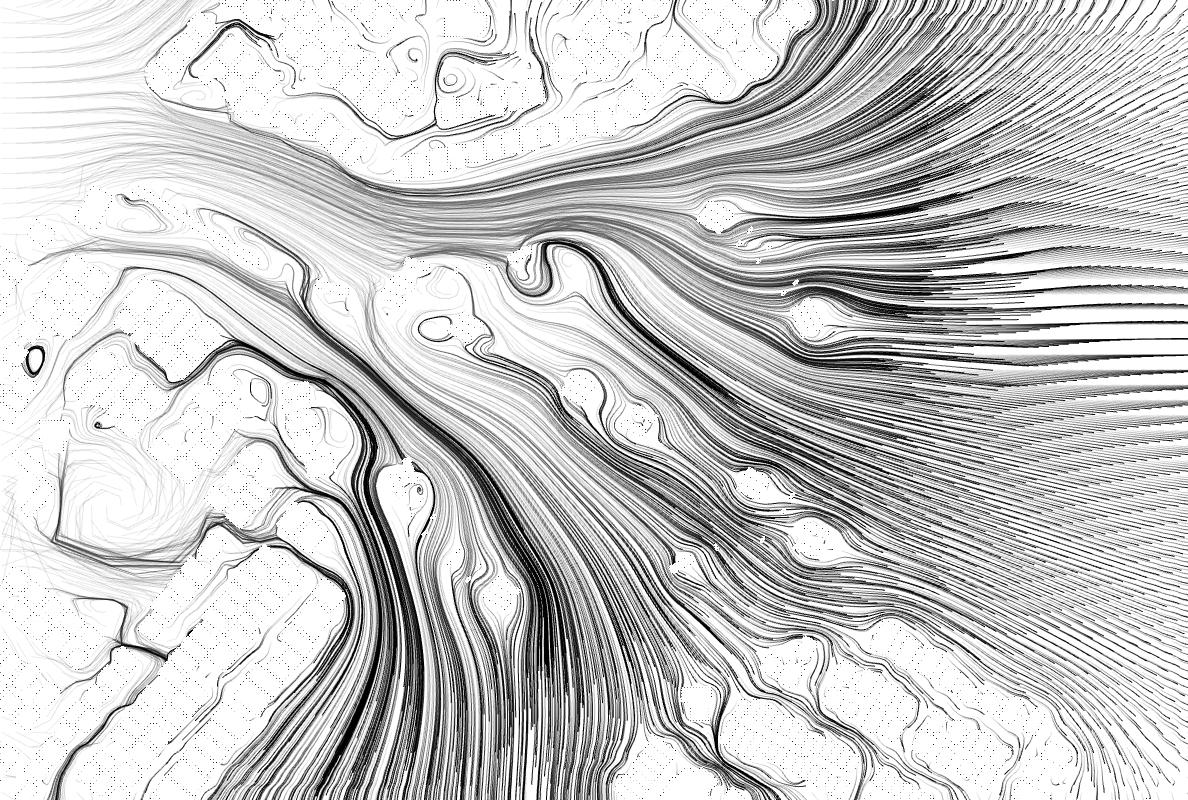

ABDULLAH AL-SALEM PARK : PLANTING PLAN COLOR PALETTE ABDULLAH AL-SALEM PARK : WIND FLOW PLAN 0m 5m 15m 30m ABDULLAH AL-SALEM PARK : PHASE 1 MOUND DRIFTING (JAN - FEB) ABDULLAH AL-SALEM PARK : PHASE 2 MOUND DRIFTING (MAR - MAY) 0m 5m 15m 30m ABDULLAH AL-SALEM PARK : PHASE 3 MOUND DRIFTING (JUN - SEPT) ABDULLAH AL-SALEM PARK : PHASE 4 MOUND DRIFTING (OCT - DEC) 39

12:00 p.m.

2:00 p.m.

4:00 p.m.

40

5:00 p.m.

6:00 p.m.

5:00 p.m.

6:00 p.m.

41

7:00 p.m.

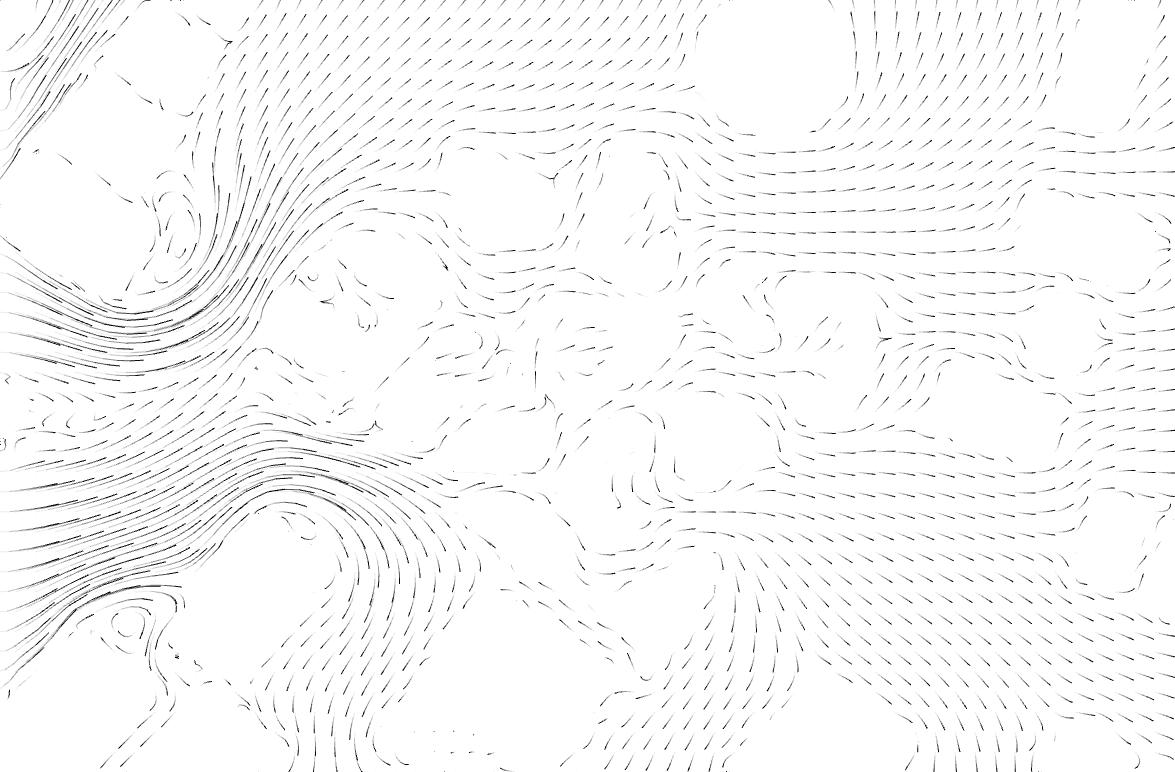

N لامشلا NE لامشلا يقرشلا E قرشلا SE بونجلا يقرشلا S بونجلا SW بونجلا يبرغلا W برغلا NW لامشلا يبرغلا YARMOUK HOUSING DISTRICT 5TH RING ROAD KHAITAN HOUSING DISTRICT AL-SIDDEEQ HOUSING DISTRICT ALSHEIKH ZAYID BIN SULTAN NIHYAN ROAD ALRIYADH STREET 0’ 20’ 40’ 100’ QORTUBA HOUSING DISTRICT لامشلا NE يقرشلا E قرشلا SE بونجلا يقرشلا S بونجلا SW بونجلا يبرغلا W برغلا AVERAGE YEARLY WIND FLOW IN SITE لامشلا يبرغلا FIFTH RING ROAD INTERCHANGE ALRIYADH ROAD ALSHEIKH ZAYID BIN SULTAN NIHYAN ROAD 42

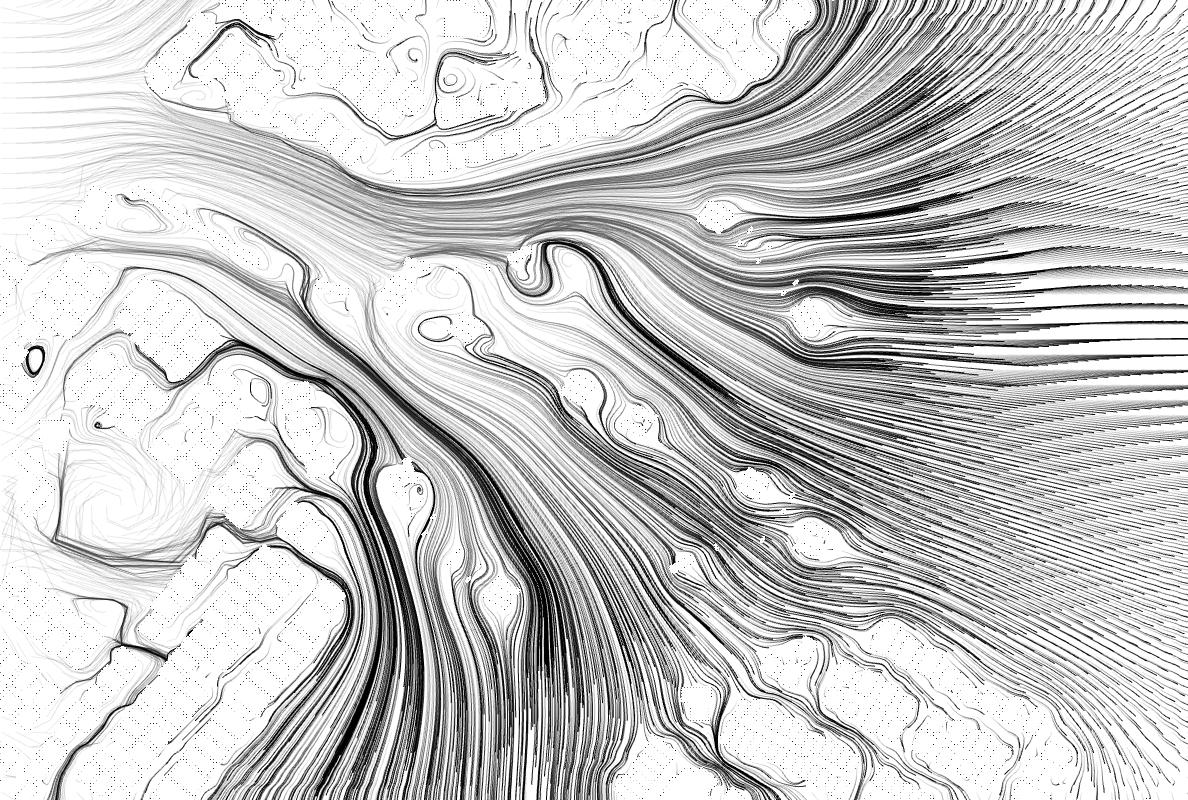

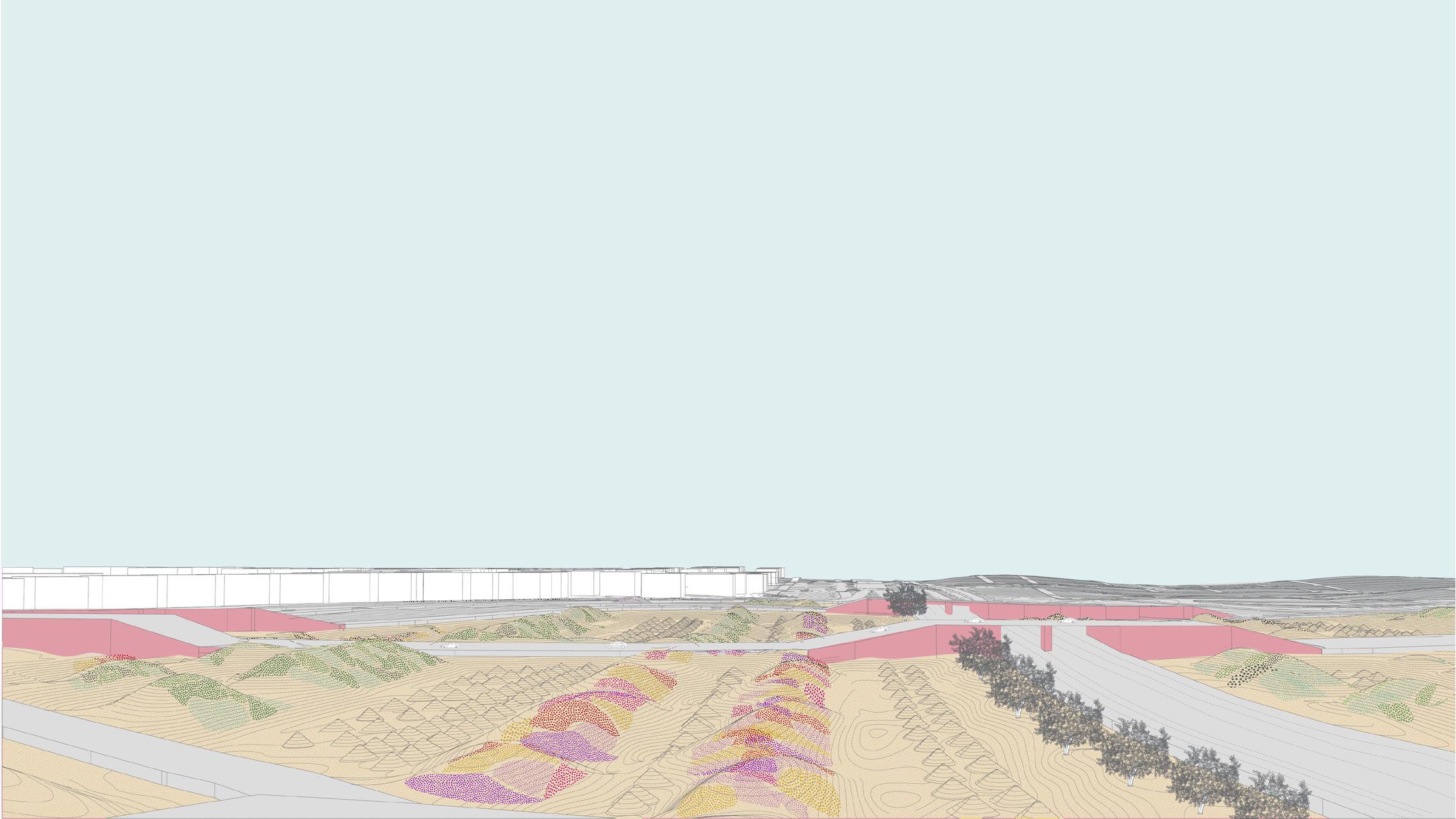

For the highway interchange, I propose creating a series of undulating mounds, completely stationary, that house in between them depressions to store collected sand from the highway networks. Given the different mound heights and widths, passing wind is either trapped, slowed down, or sped up allowing dust carrying winds to lose momentum when passing through the interchange leaving less deposited sand on the roads.

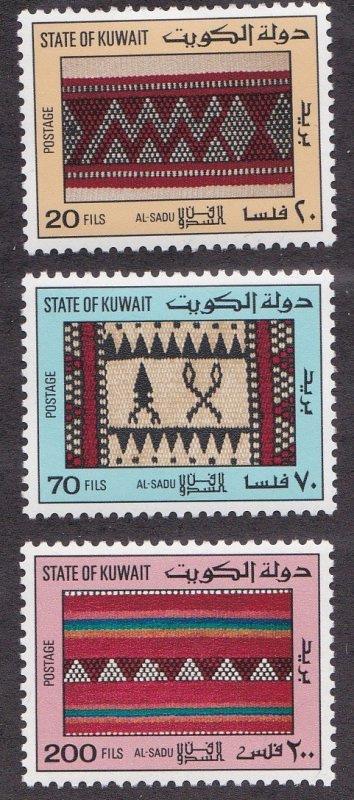

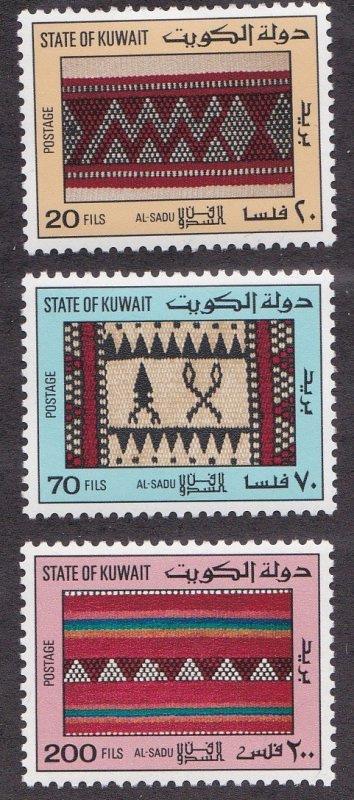

As a reference I look to Sadu weavings, cultural productions by Bedouin tribes in the Kuwait desert. The interchange is a series of interwoven systems, connecting traffic, people, vehicles, and locations to one another. The geometric icons used in the weaving abstract things found in the landscape, as I propose to read these weaves instead as patterns of geologic infrastructure. The lines carry height and volume, beginning to assemble a topographic plan.

THE INTERCHANGE CONCEPT 43

Image of Al-Sadu weavings on Kuwait postage stamps. Source: https://www.hipstamp.com/ display-feedback/greatbids1

30m 60m

FIFTH

0m 30m 60m

FIFTH

PLAN

44

0m

90m

RING ROAD INTERCHANGE : PHASE 2 (JAN - MAY) FIFTH RING ROAD INTERCHANGE : PHASE 3 (JUN - DEC)

90m

RING ROAD INTERCHANGE : PROPOSED PLAN AND PLANTING

FIFTH RING ROAD INTERCHANGE : PHASE 1 SITE AFTER SAND-FILLED TRUCKS DISCHARGE TRUCK BINS HUBUB PATTERN (SEEDS) ALEIN PATTERN (EYES) MITHKHAR PATTERN UWAIRJAN PATTERN (ZIG ZAGS)

45

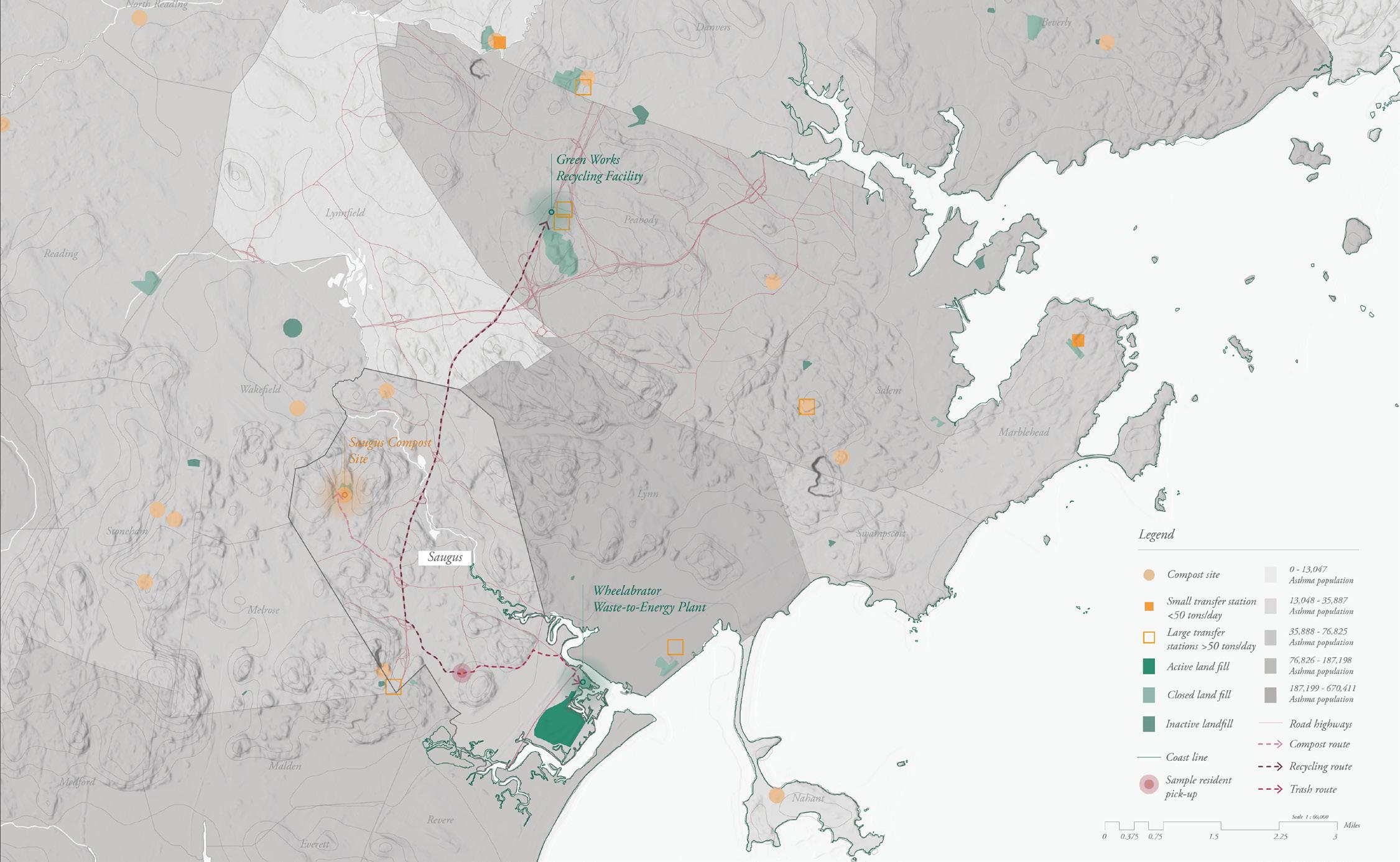

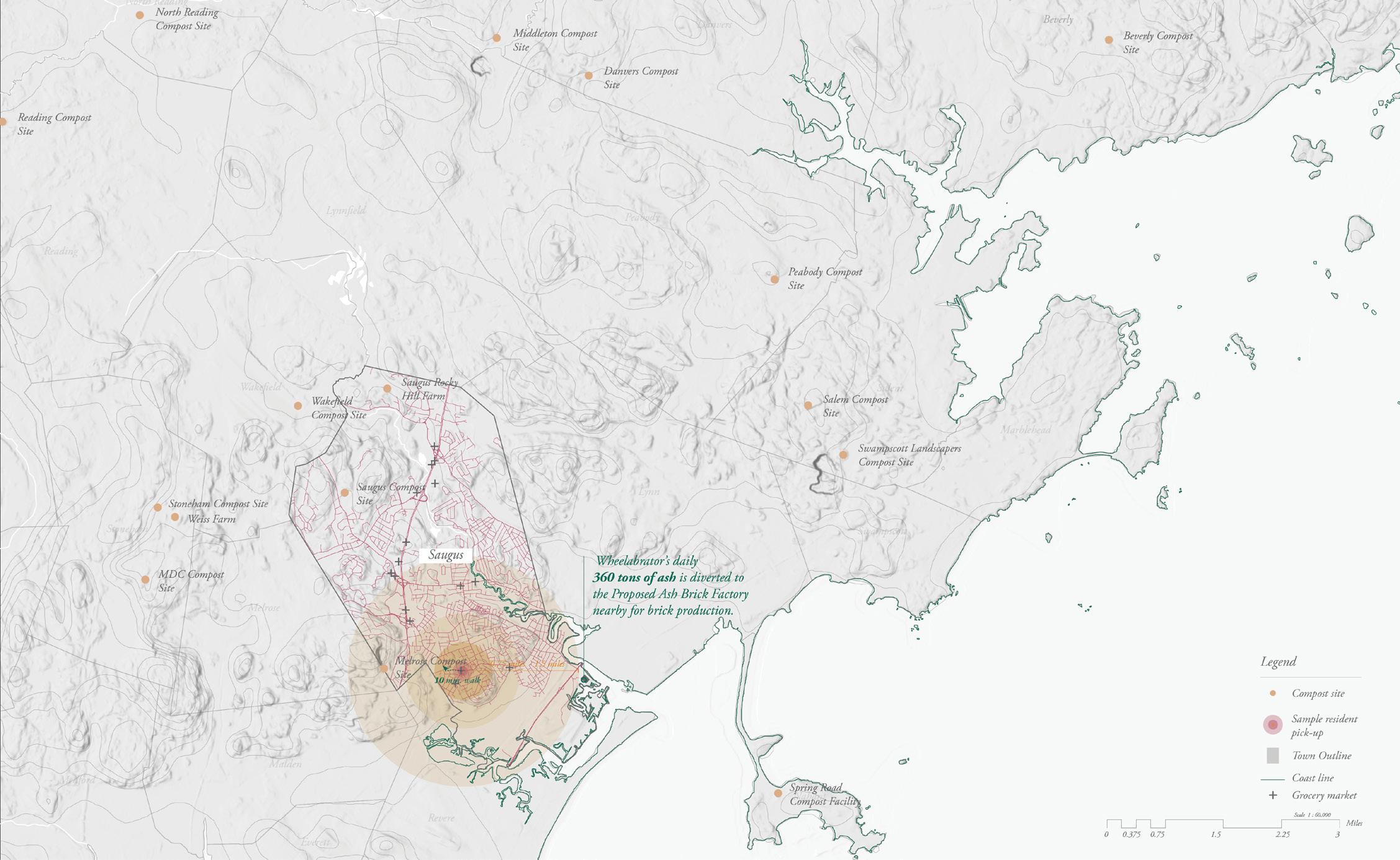

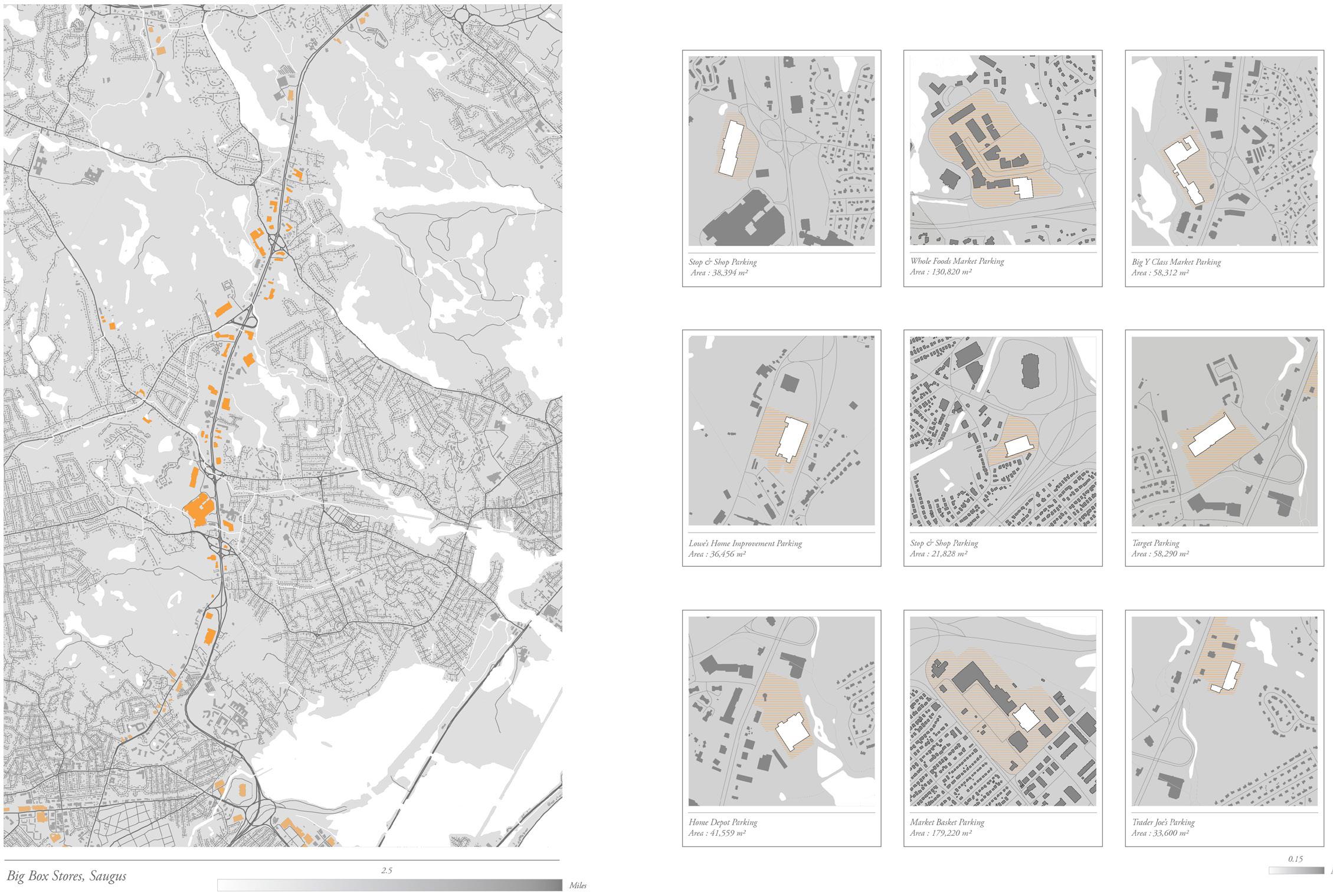

Ashes to Ashes, Saugus MA.

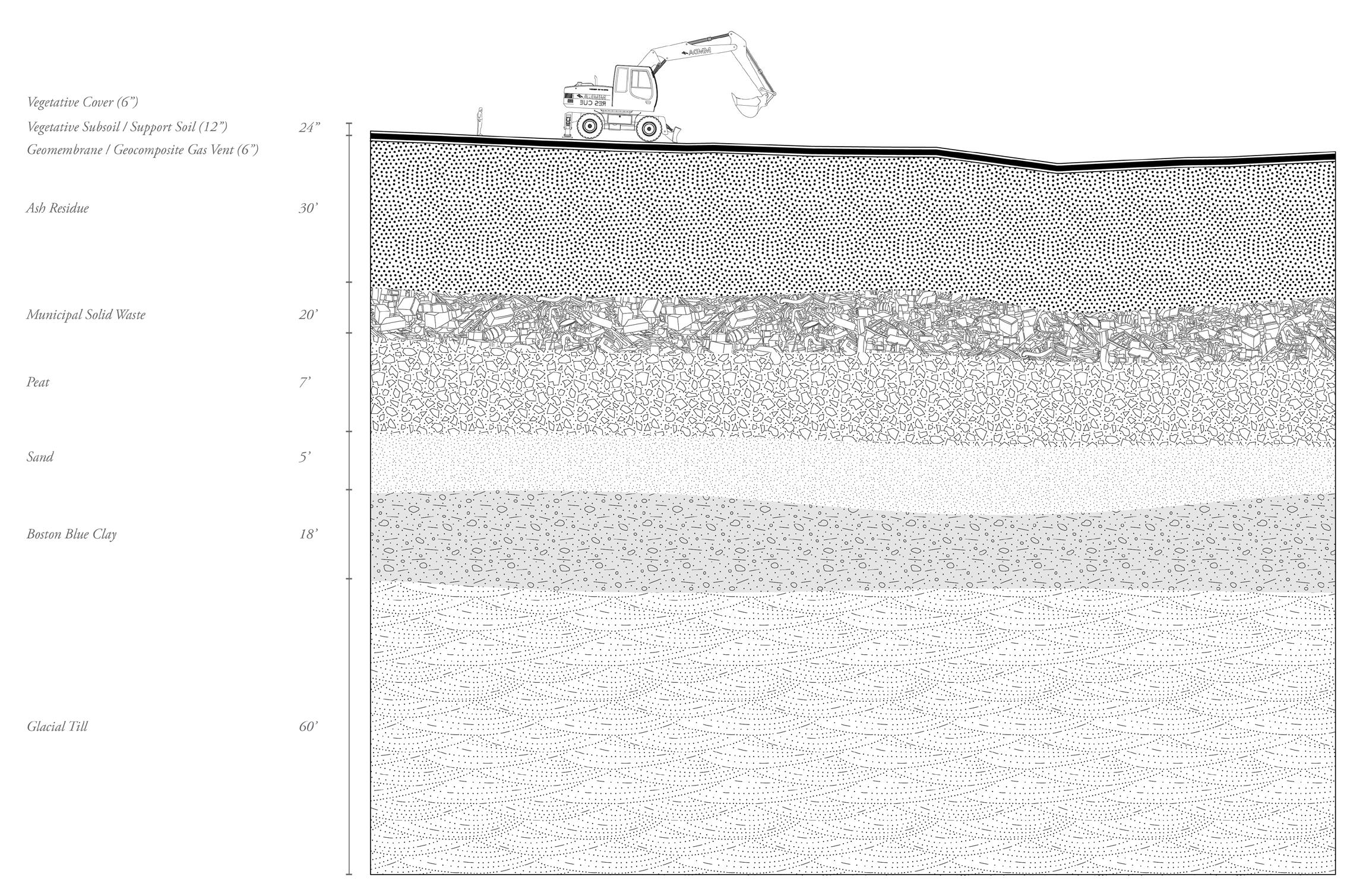

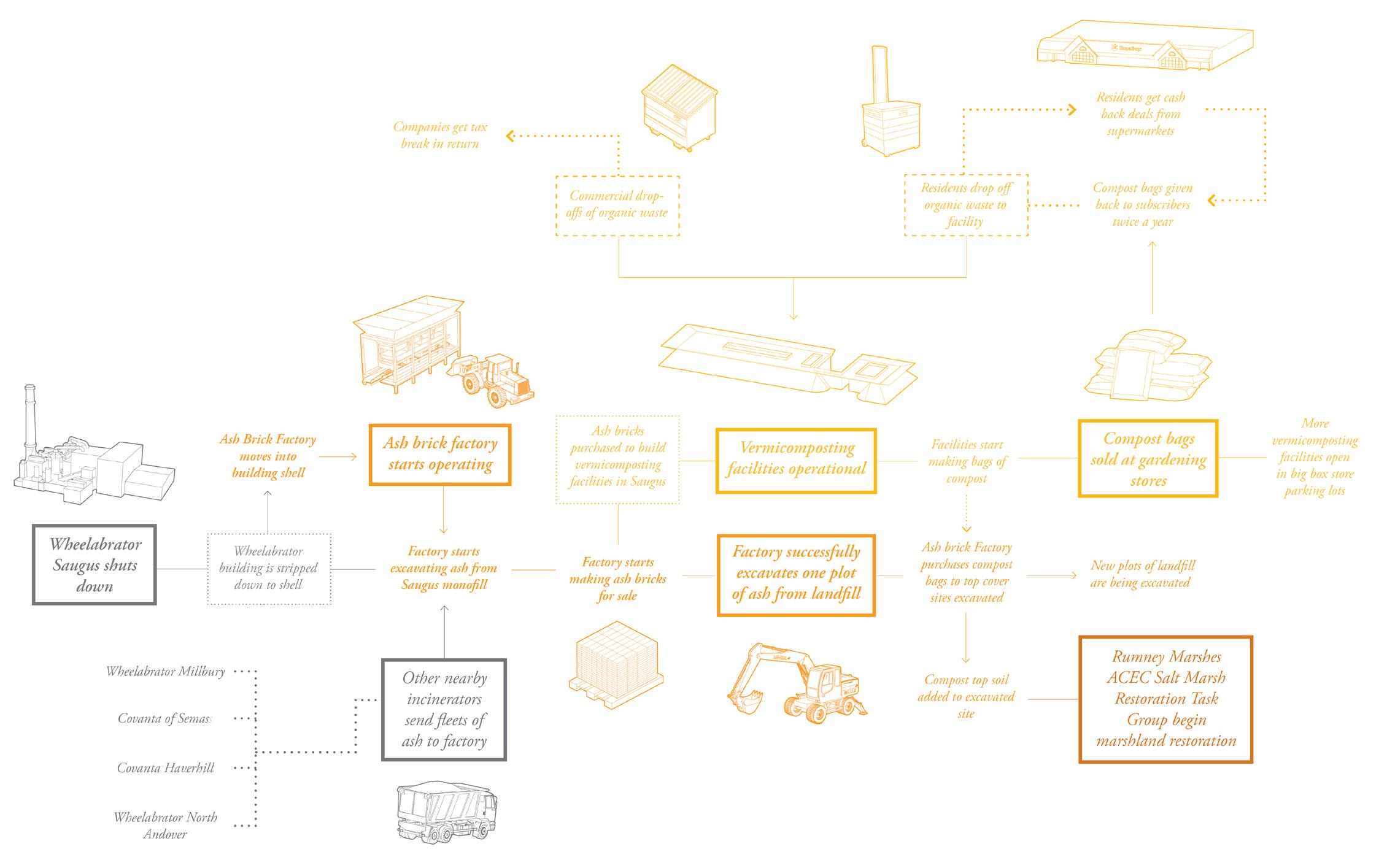

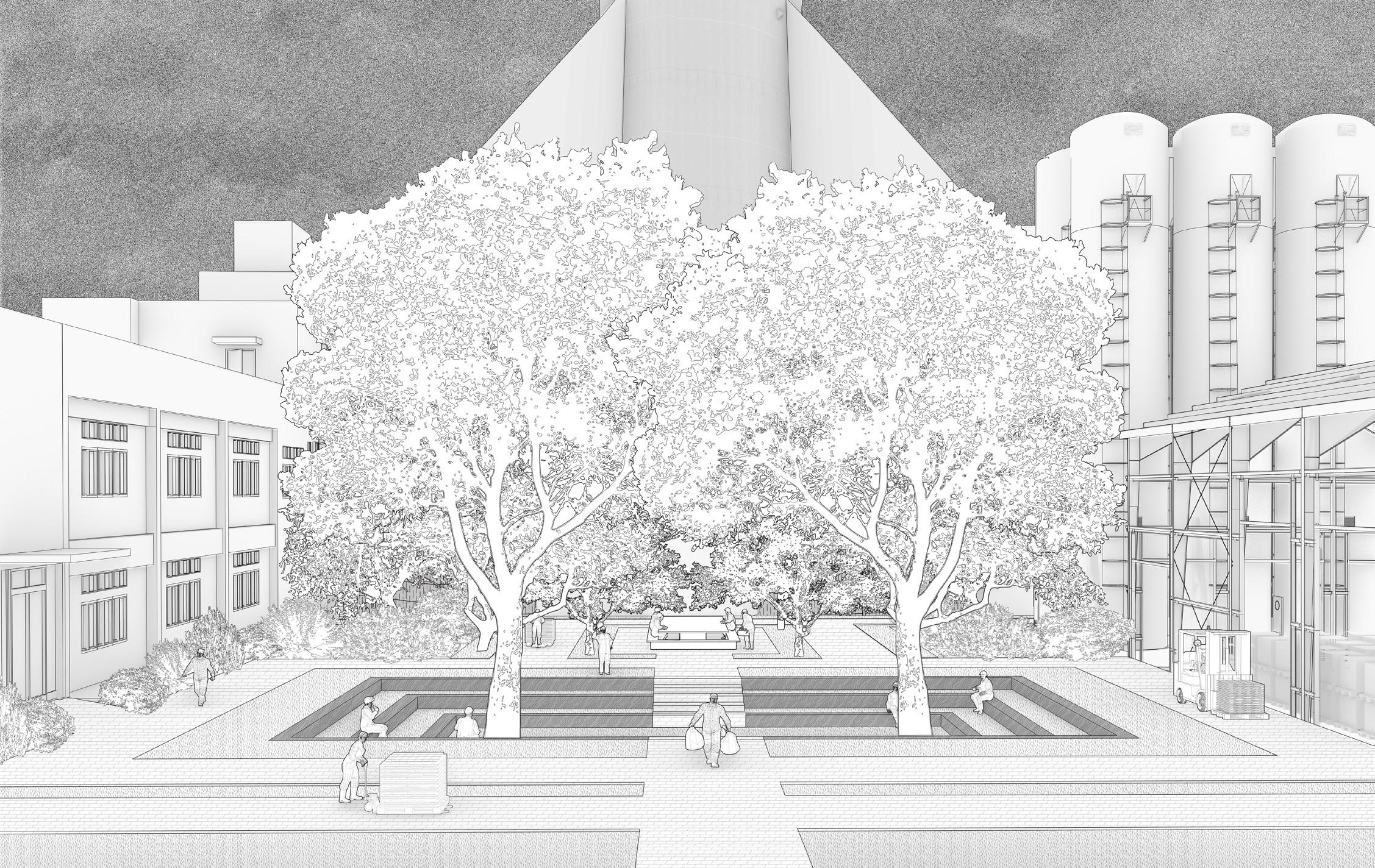

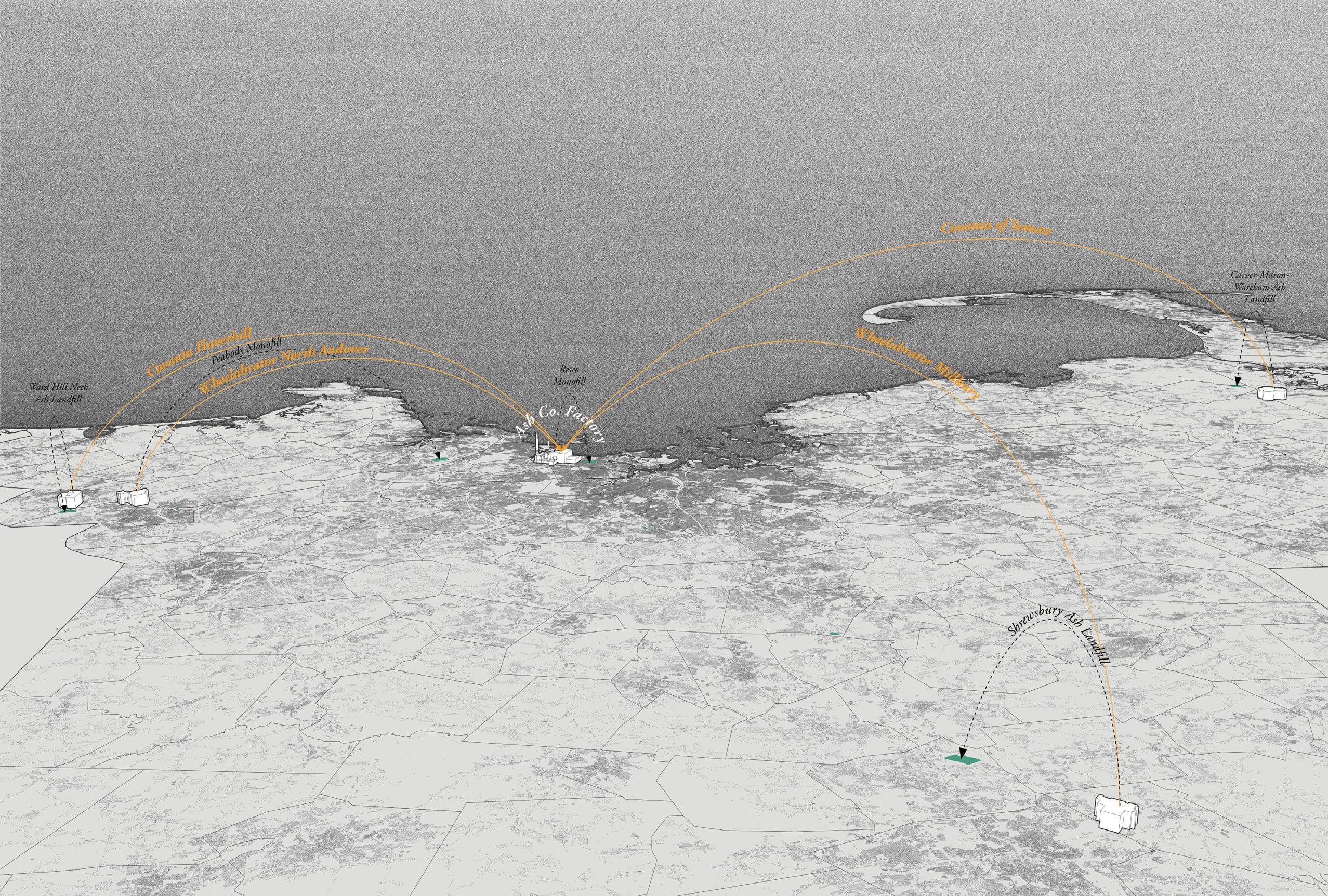

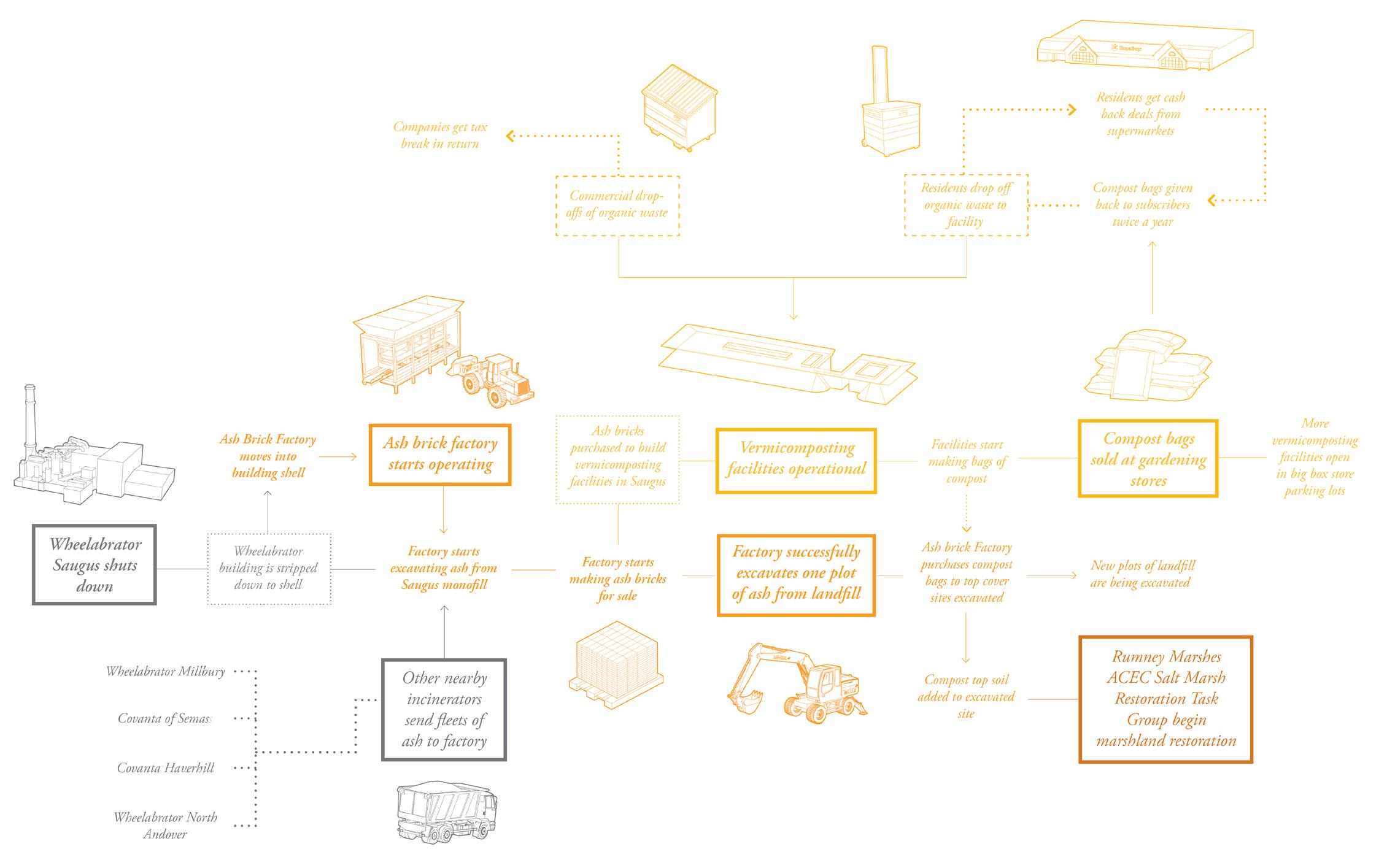

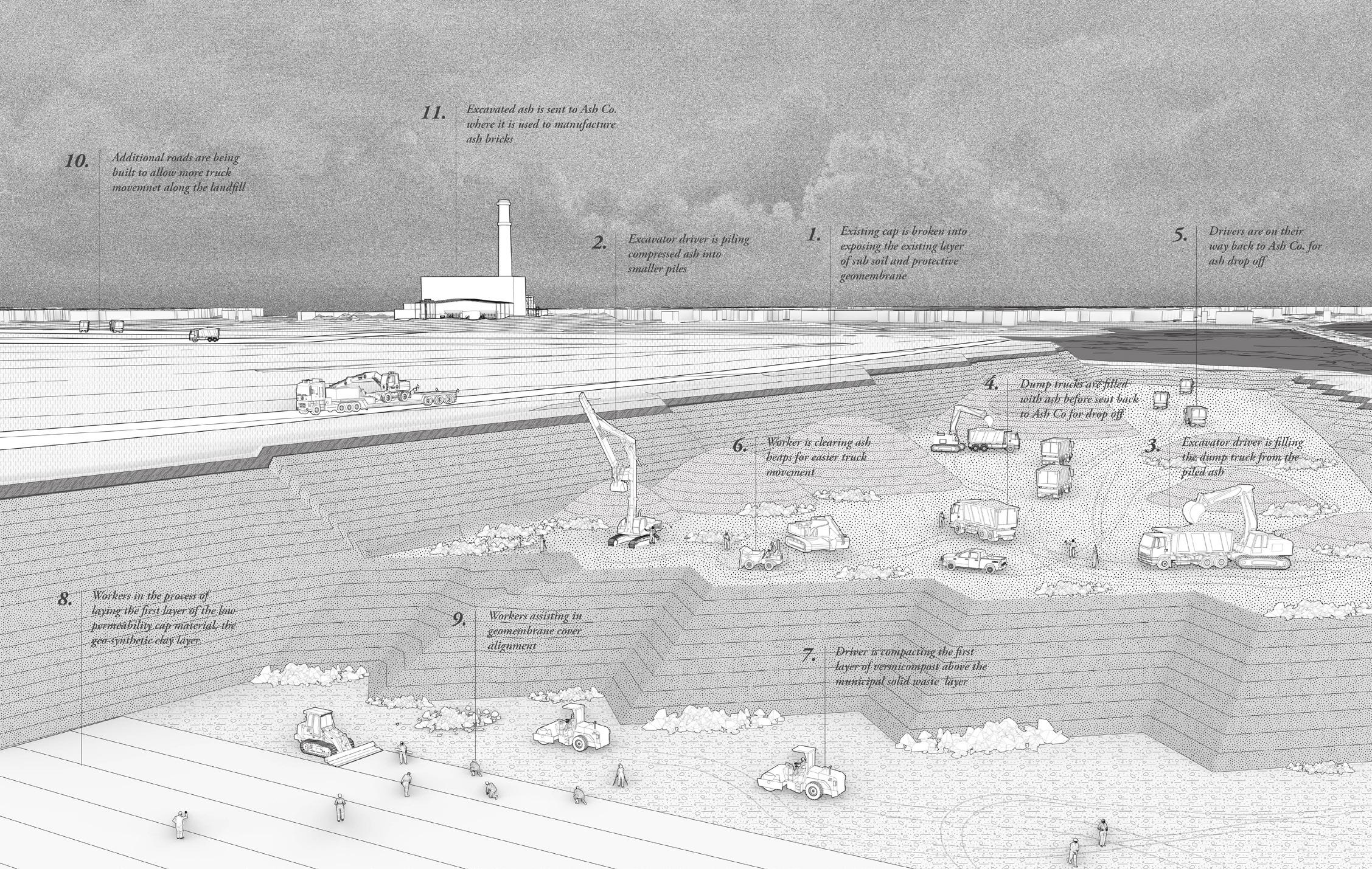

Waste-to-energy incinerators, scattered over Massachusetts, have been dumping ash into landfills for decades. Despite knowing the resulting environmental risks, this industry has only found new ways to improve the process of dumping. This proposal addresses both the inputs and outputs of the processes of waste incineration as valuable materials that can be put to good use rather than being burned or buried.

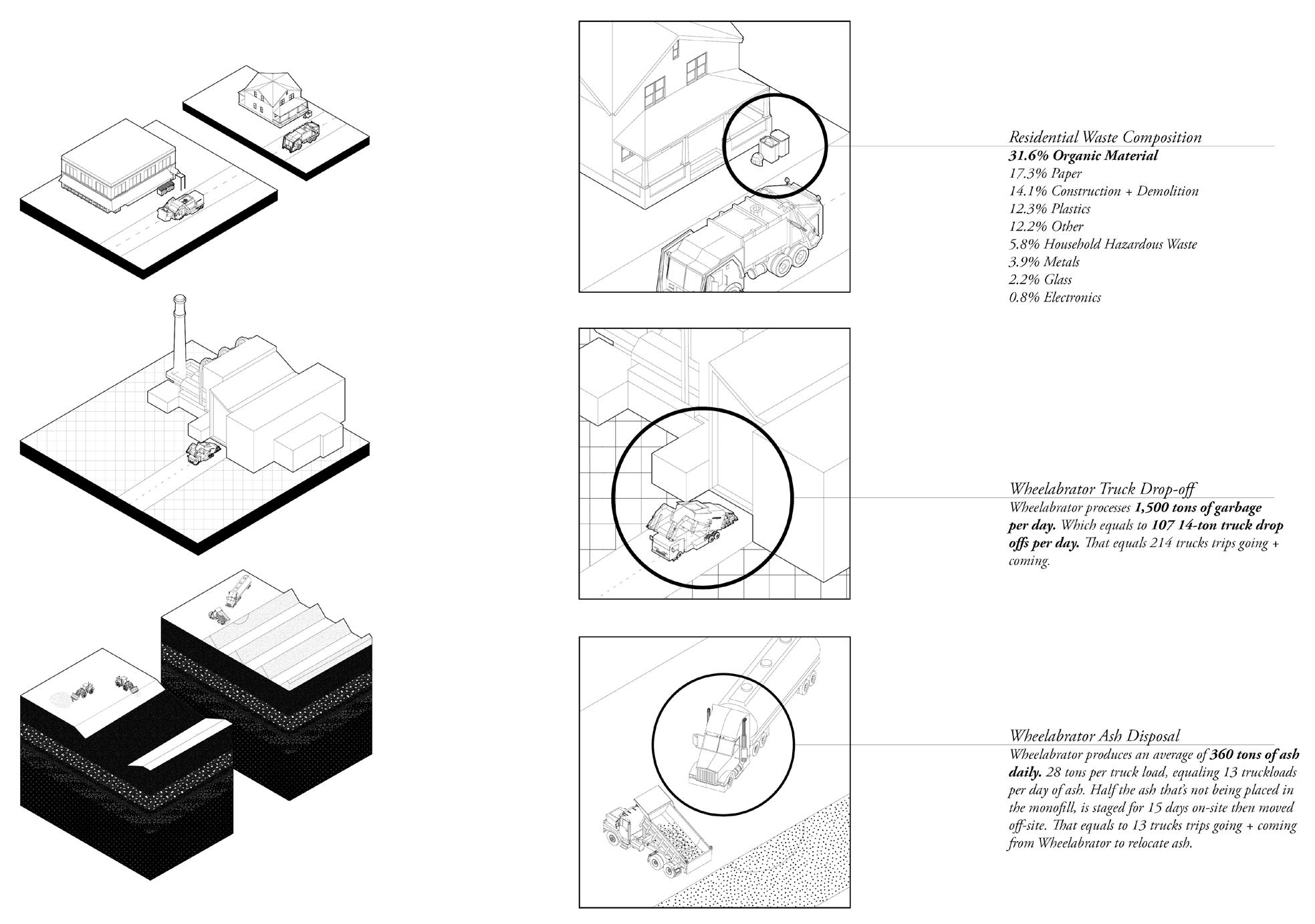

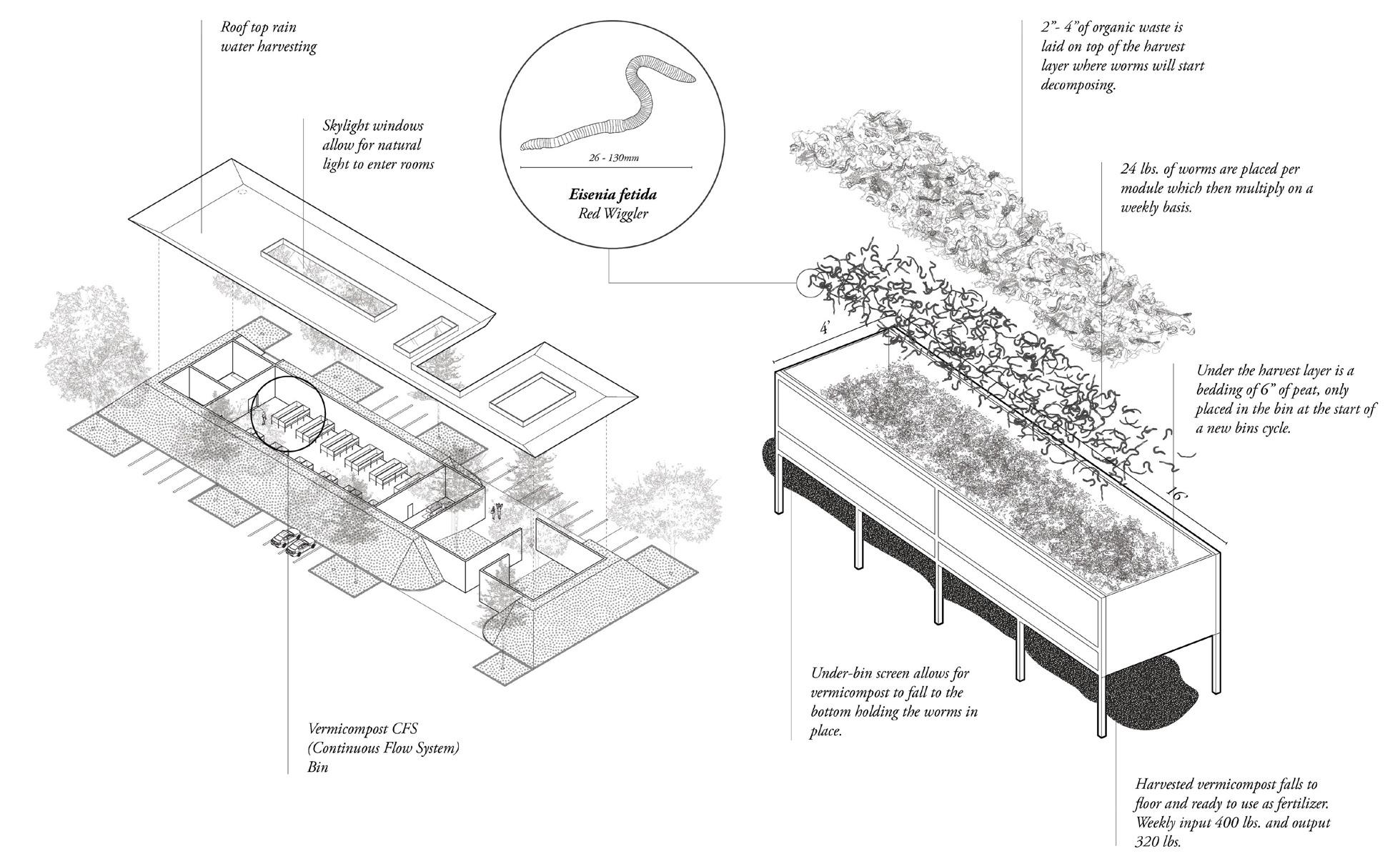

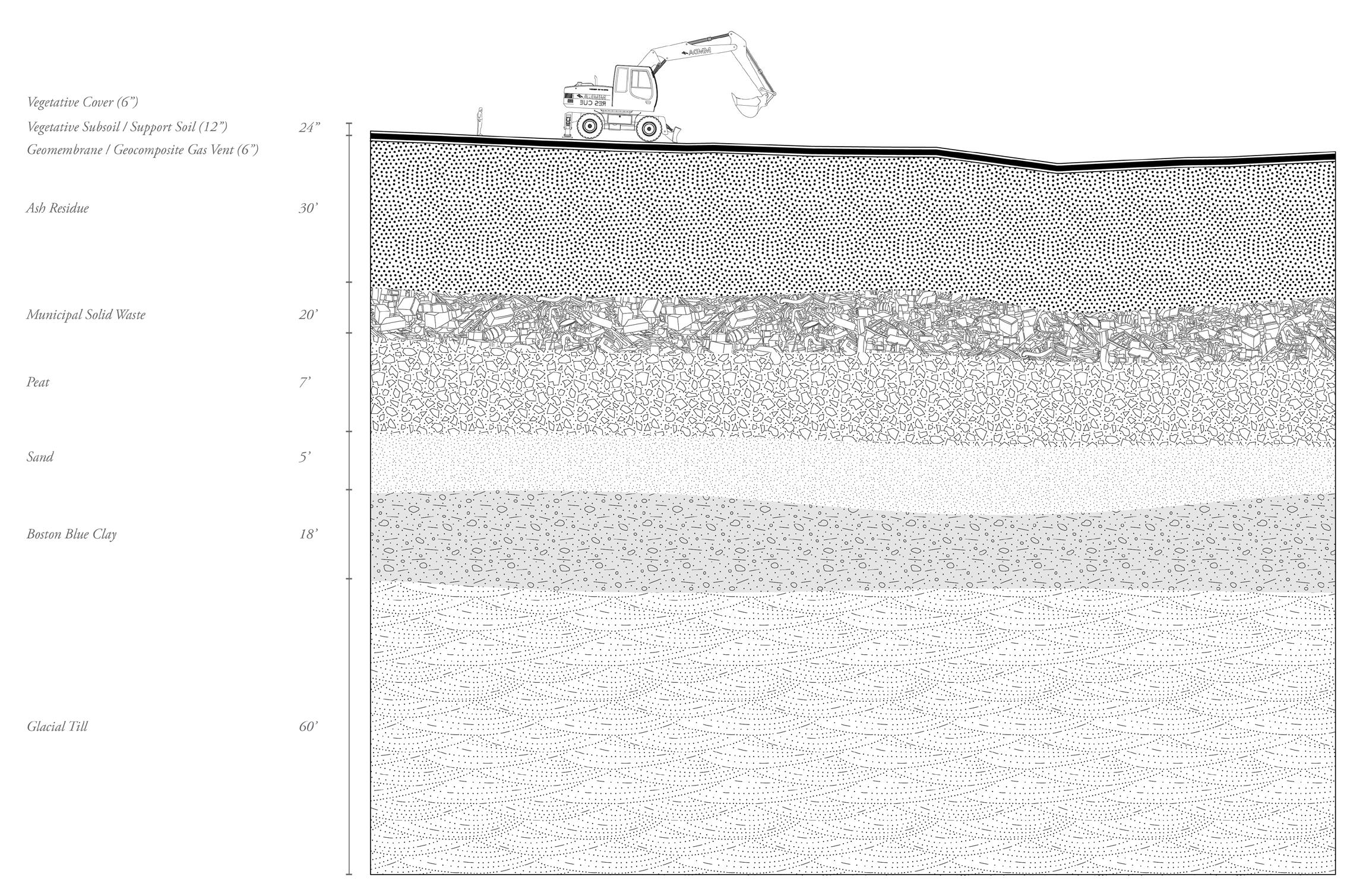

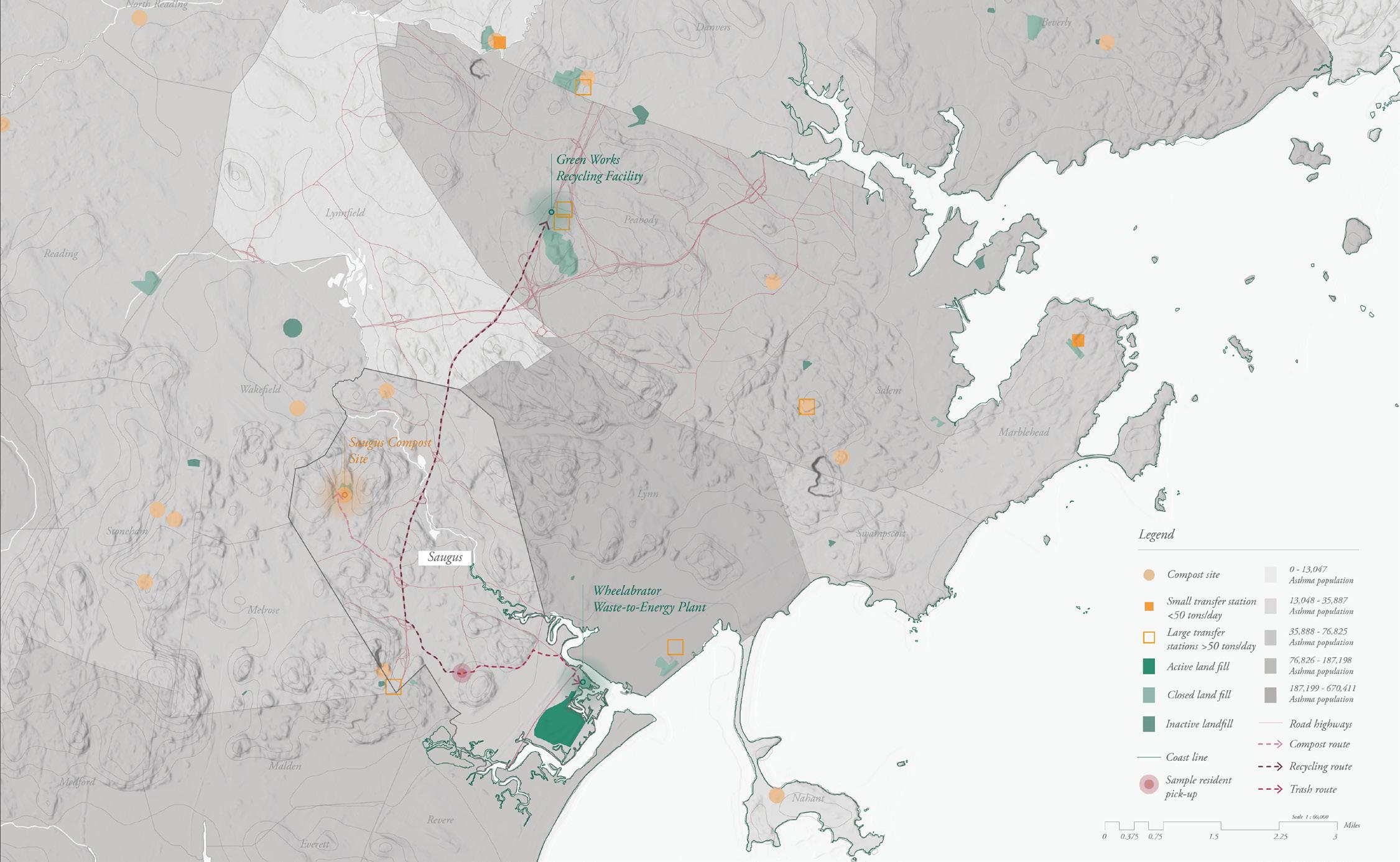

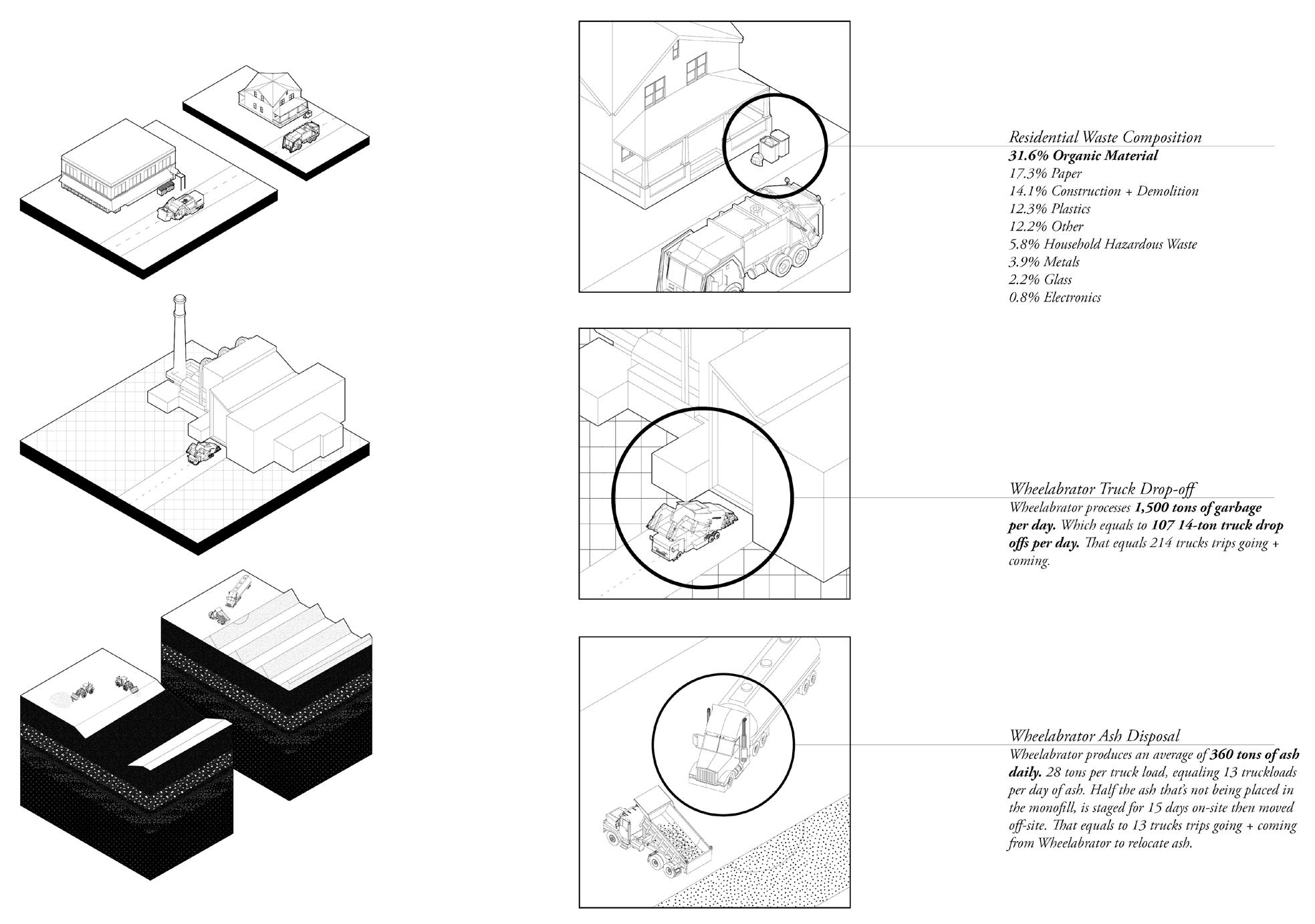

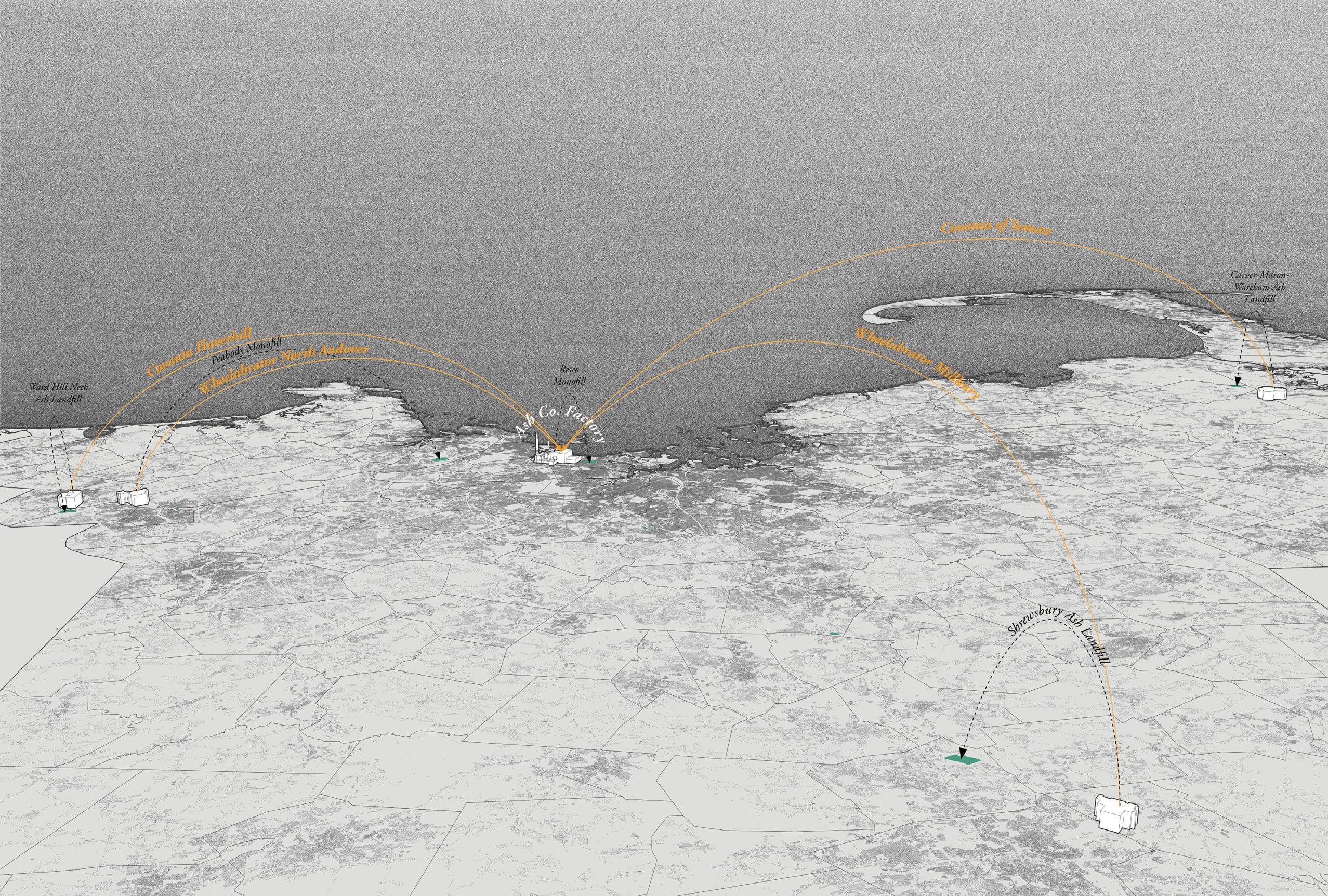

Ashes to Ashes takes a closer look into Wheelabrator’s Waste-toenergy plant and adjacent landfill situated in the Rumney Marshes in Saugus Massachusetts, addressing the 31% of organic waste that is being burned and the 360 tons of ash being produced on a daily basis.

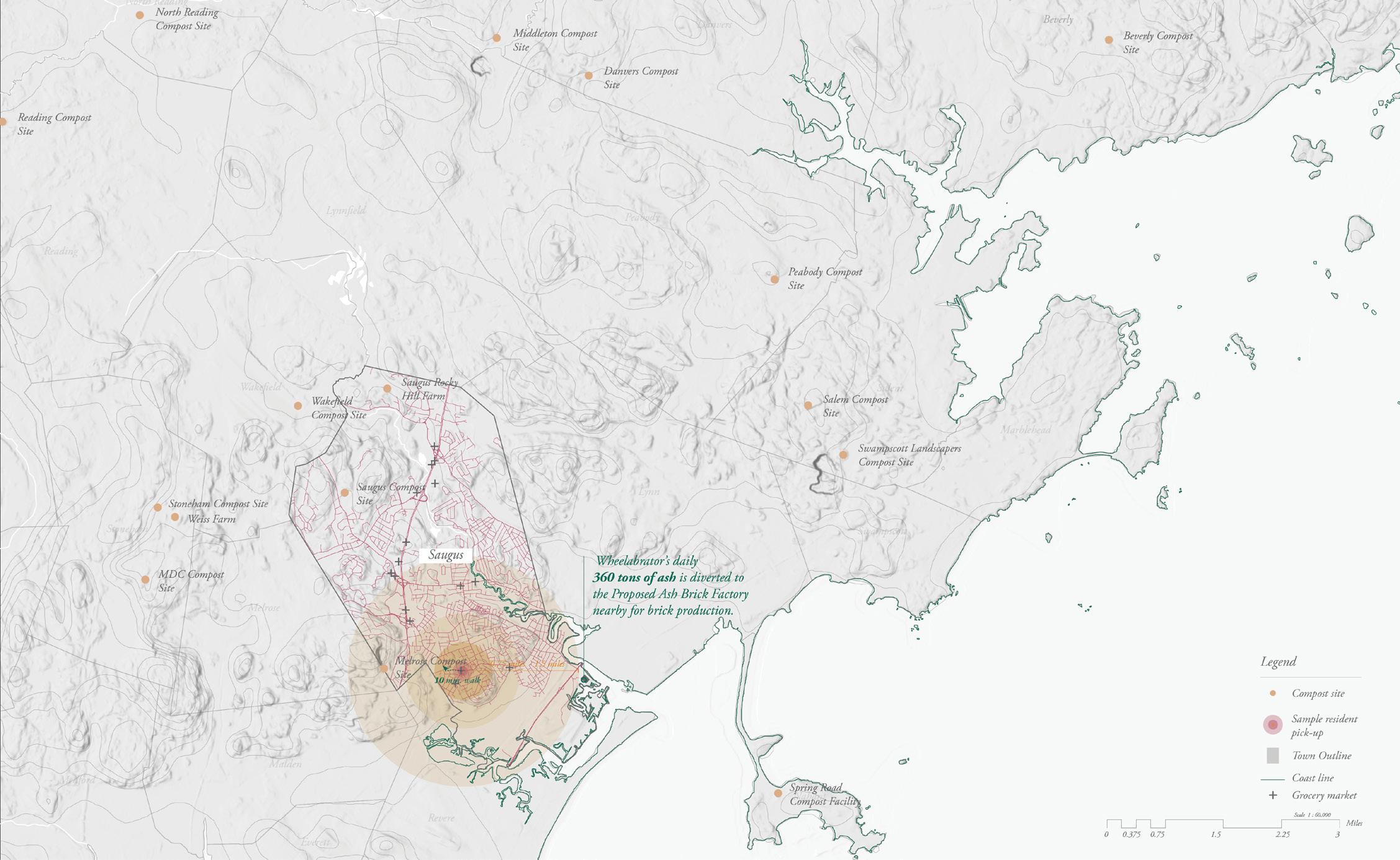

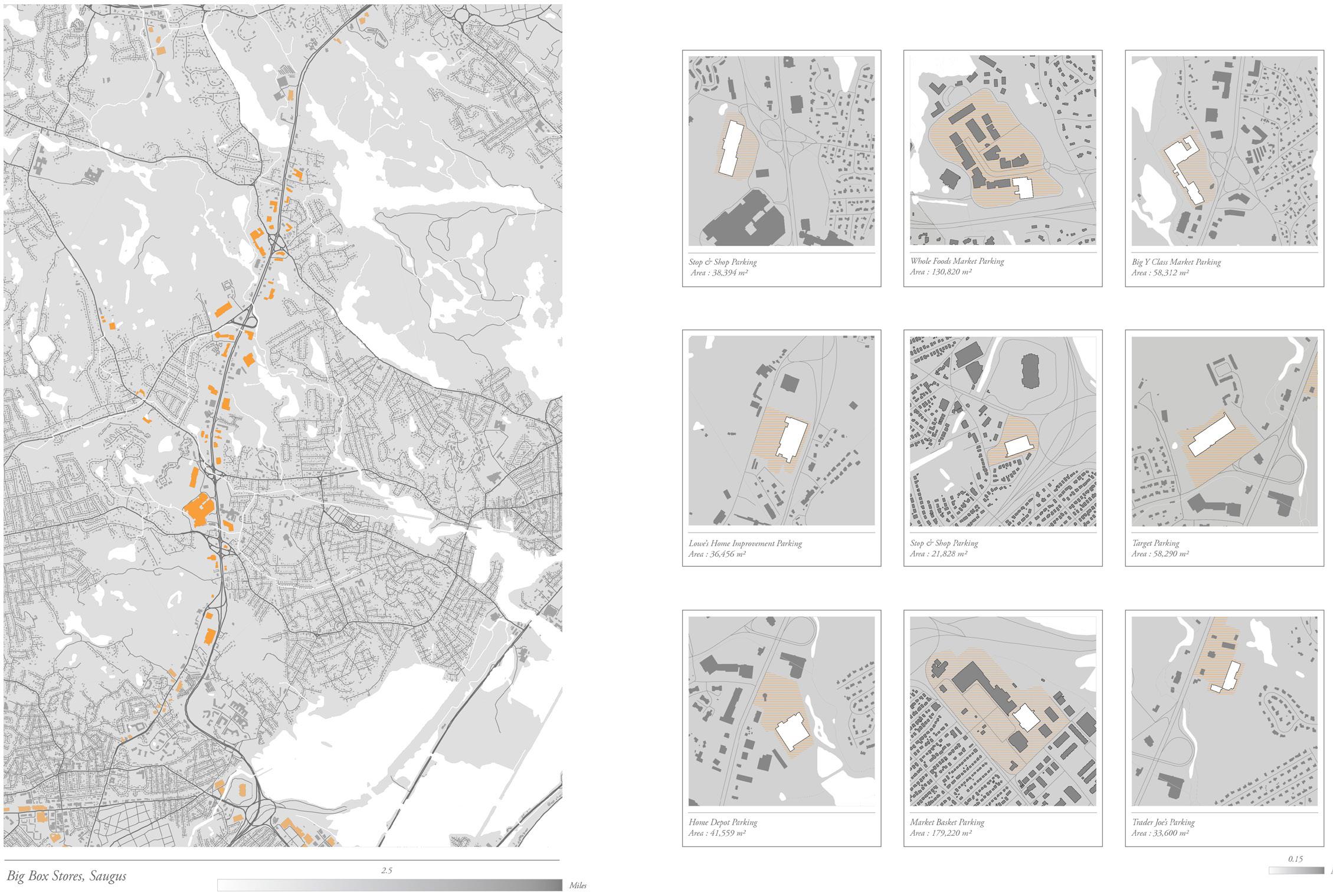

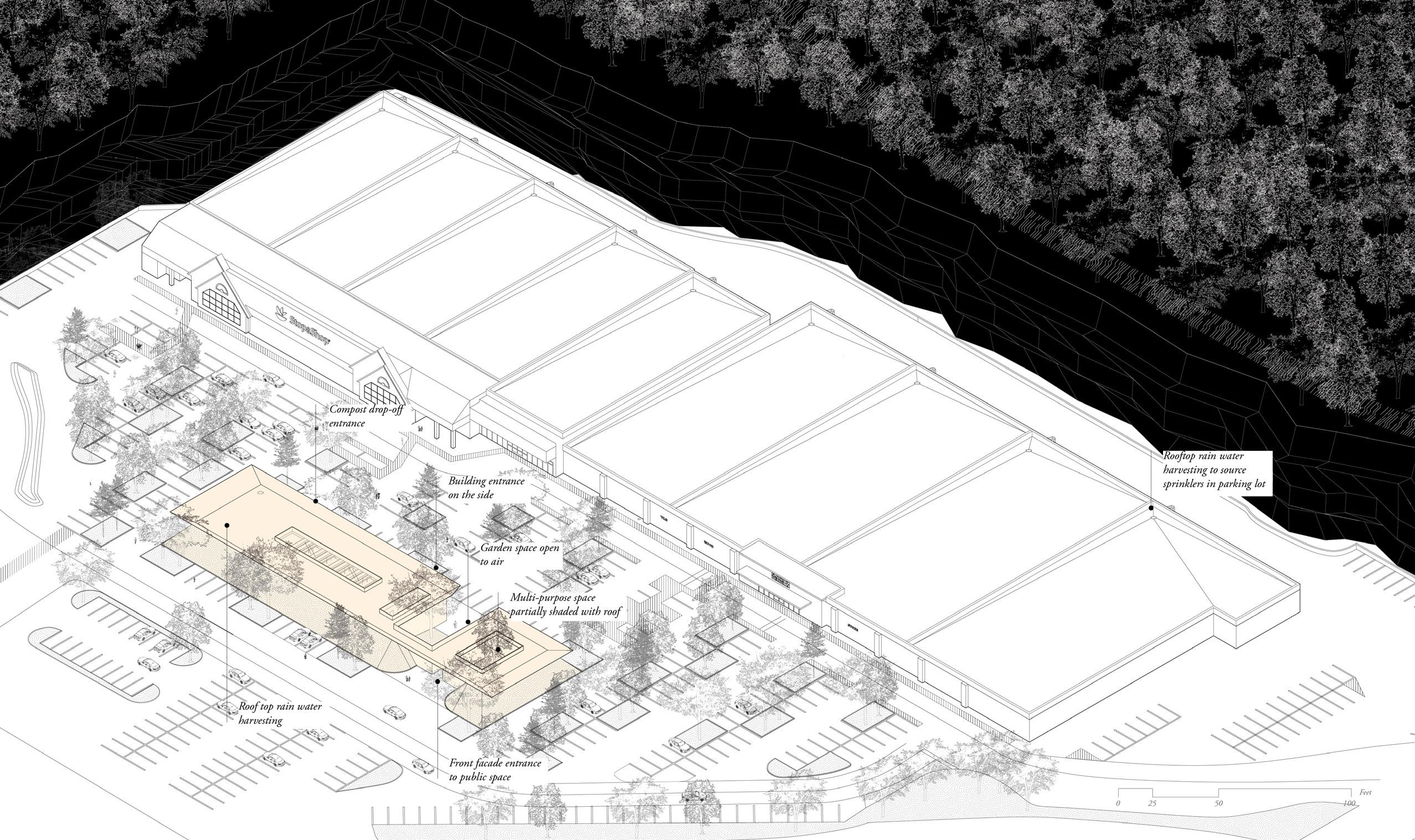

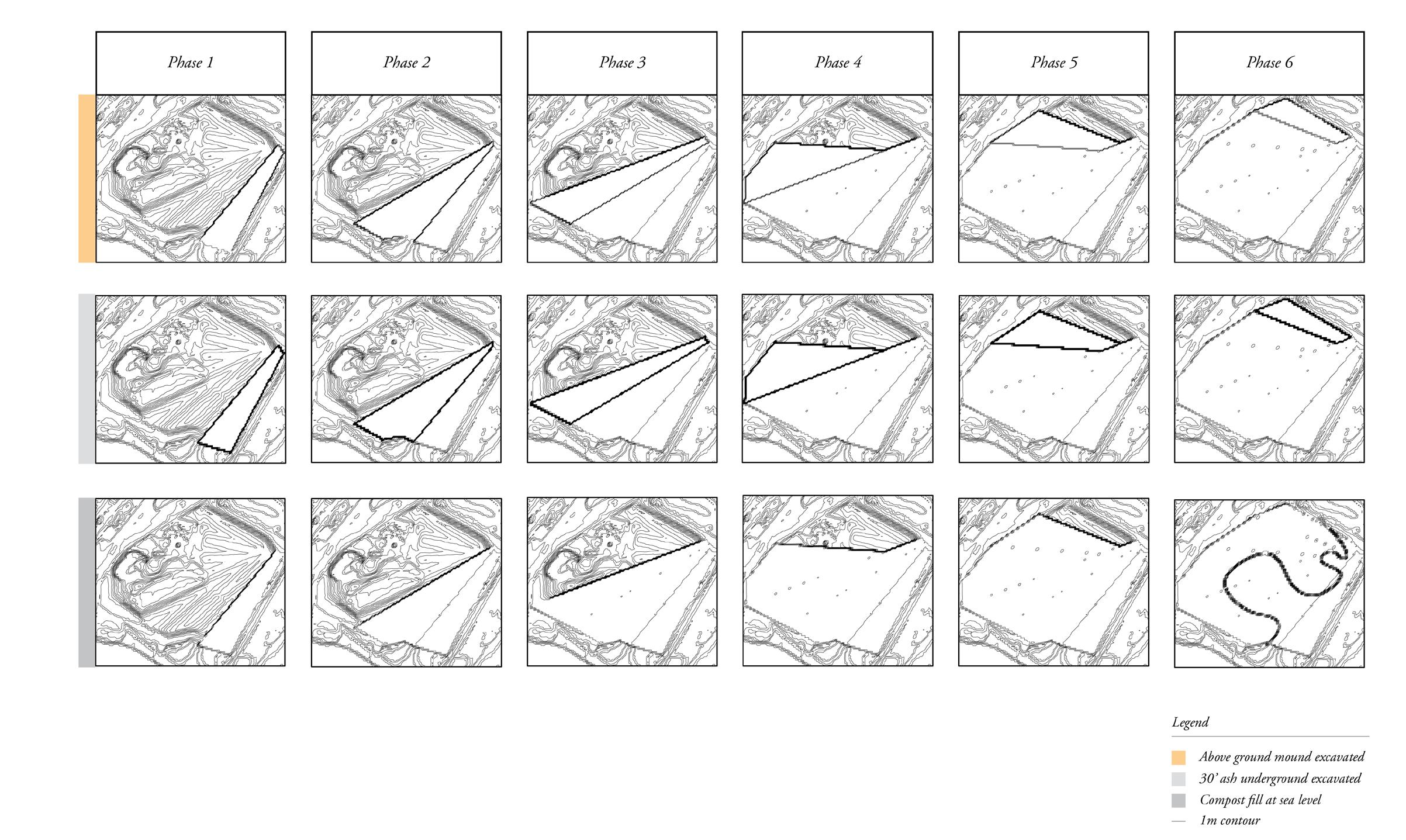

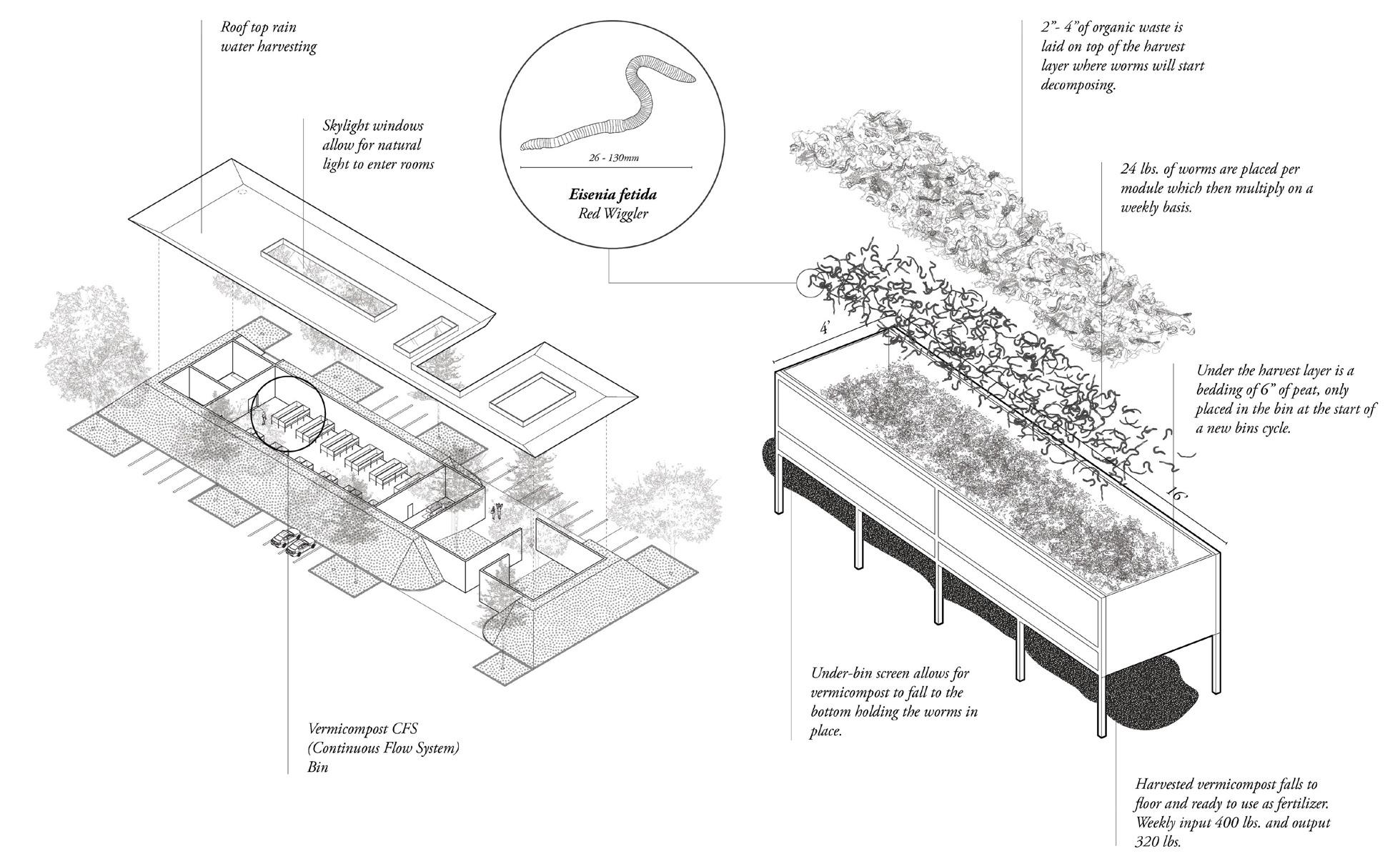

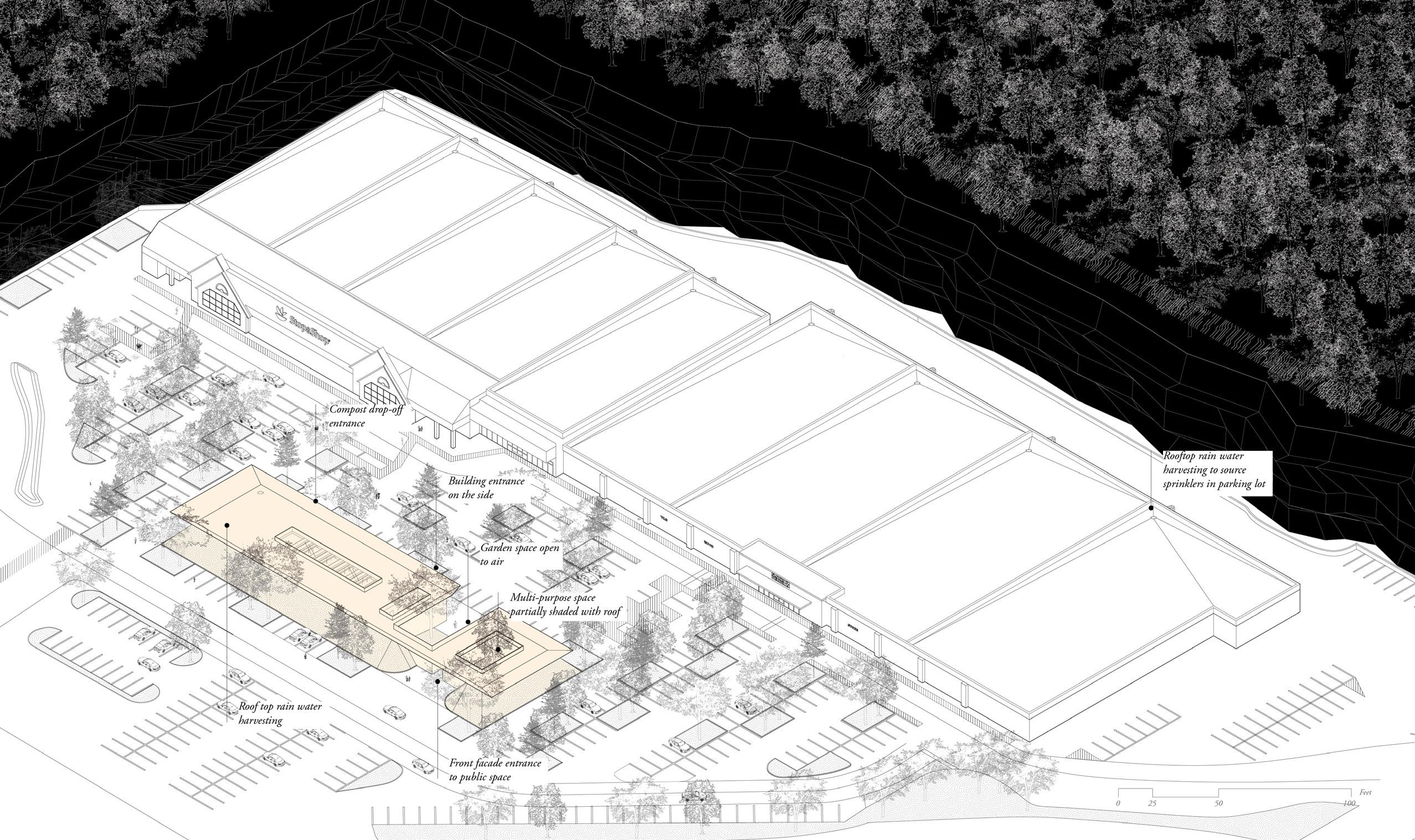

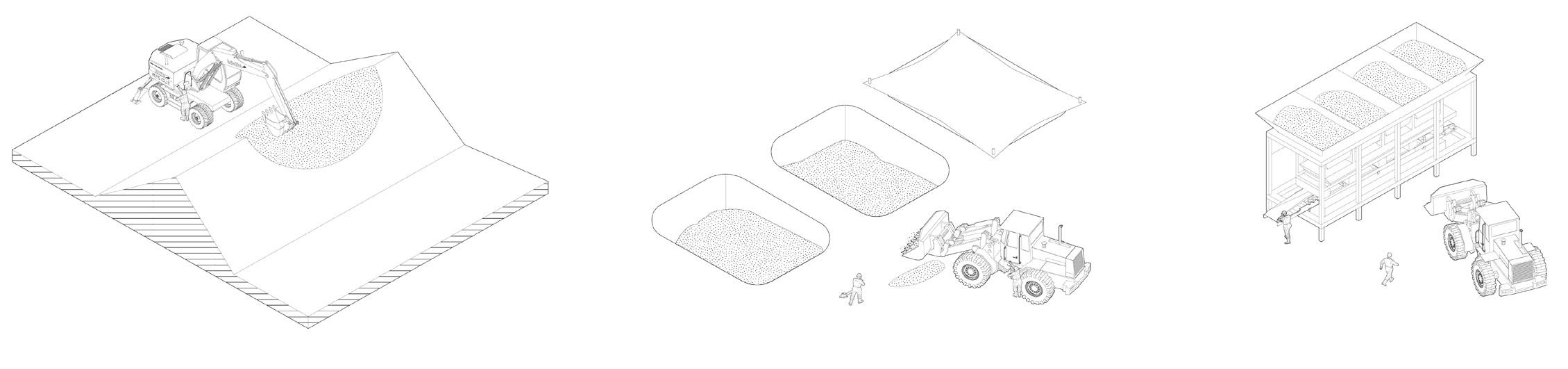

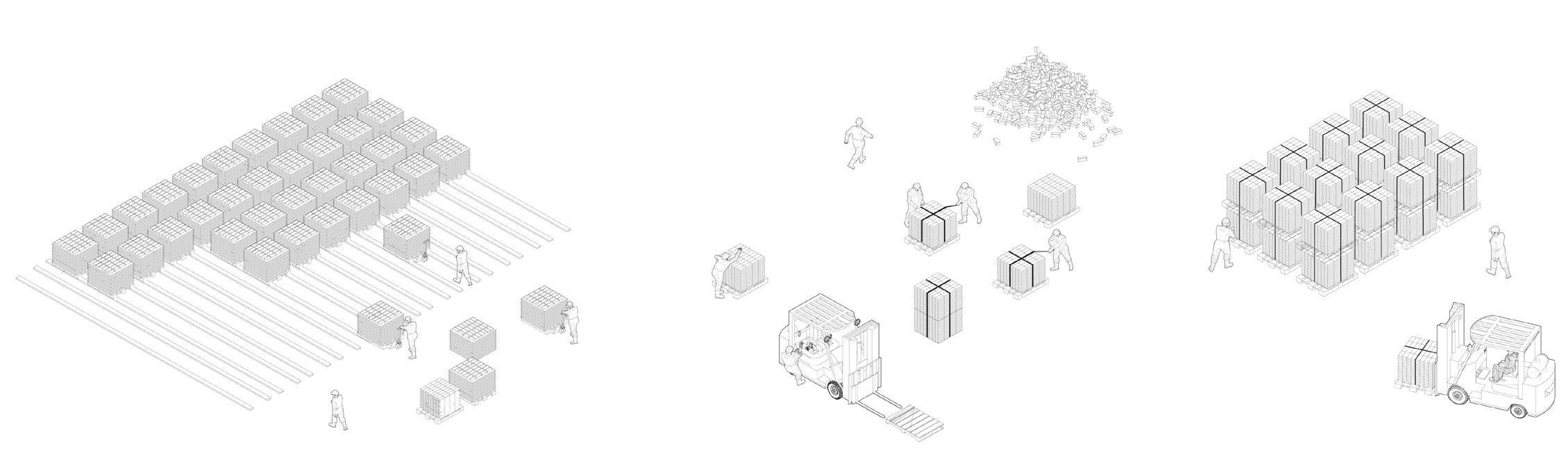

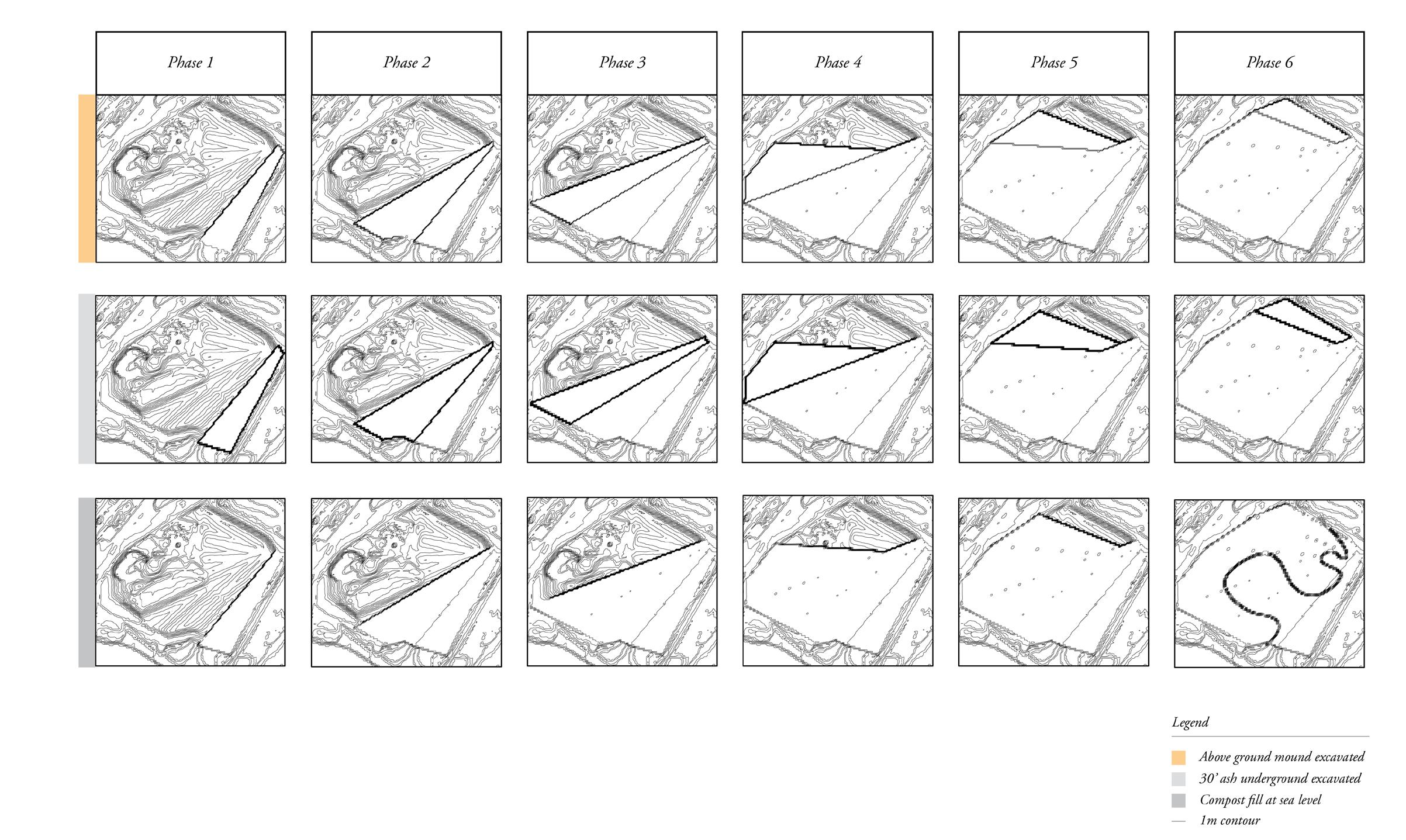

In an effort to divert 31% of Wheelabrator’s waste composition, localized vermicomposting facilities are built on underutilized big box store parking lots in the town using ash brick construction. In anticipation of Wheelabrator’s inevitable shutdown, the building is stripped and re-purposed to house an ash brick factory, while the neighboring landfill is excavated for ash material. As each phase of excavation is complete, compost produced from the vermicomposting facilities will be used to cover the landfill site as marshland restoration work takes place by the Rumney Marshes ACEC Salt Marsh Restoration Task Group.

46

47

Map of contract towns that send waste to Wheelabrator Saugus.

Map of current trash route from sample resident address. 48

Current trash cycle in Saugus, MA.

Proposed locations of vermicomposting facilities.

Proposed locations of vermicomposting facilities.

49

Map of proposed distances to vermicomposting facility based on sample resident address.

Components

part of the vermicomposting cycle.

part of the vermicomposting cycle.

50

Axon view of the vermicomposting facility in a Stop & Shop parking lot, Saugus.

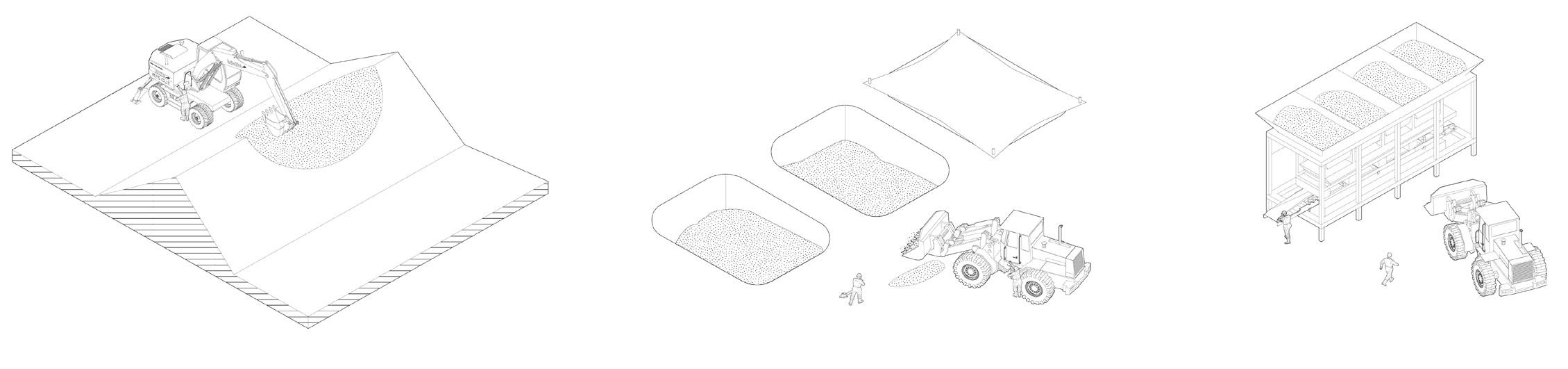

Ash Grinding

Excavating Ash Ash Staging

Brick Drying

Brick Packing

Ash Grinding

Excavating Ash Ash Staging

Brick Drying

Brick Packing

51

Shipment Sorting

52

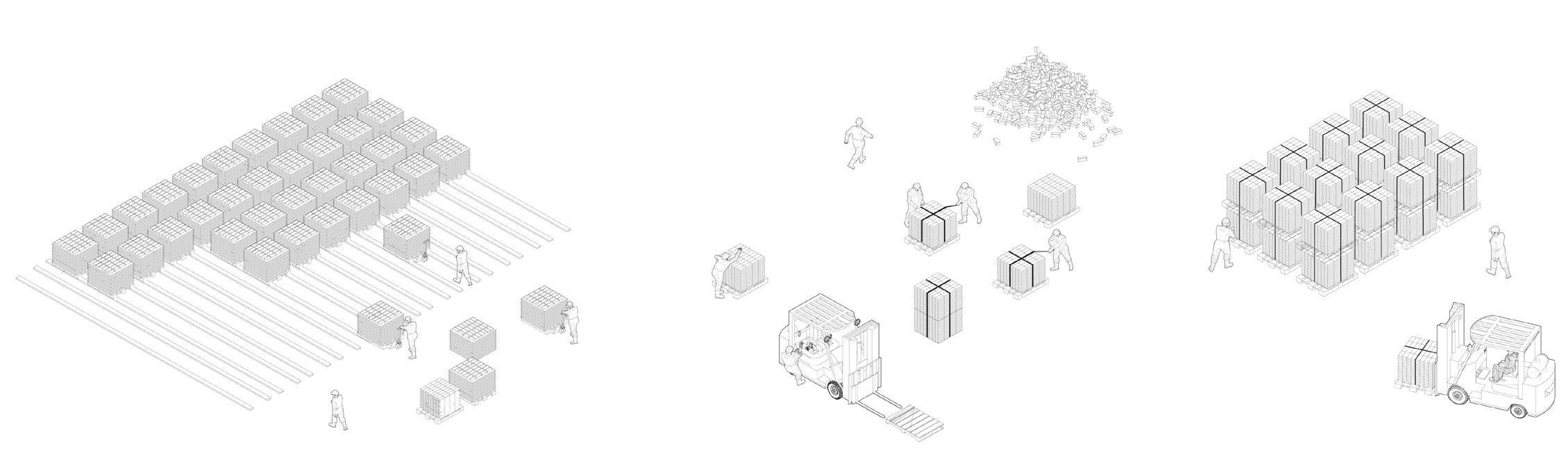

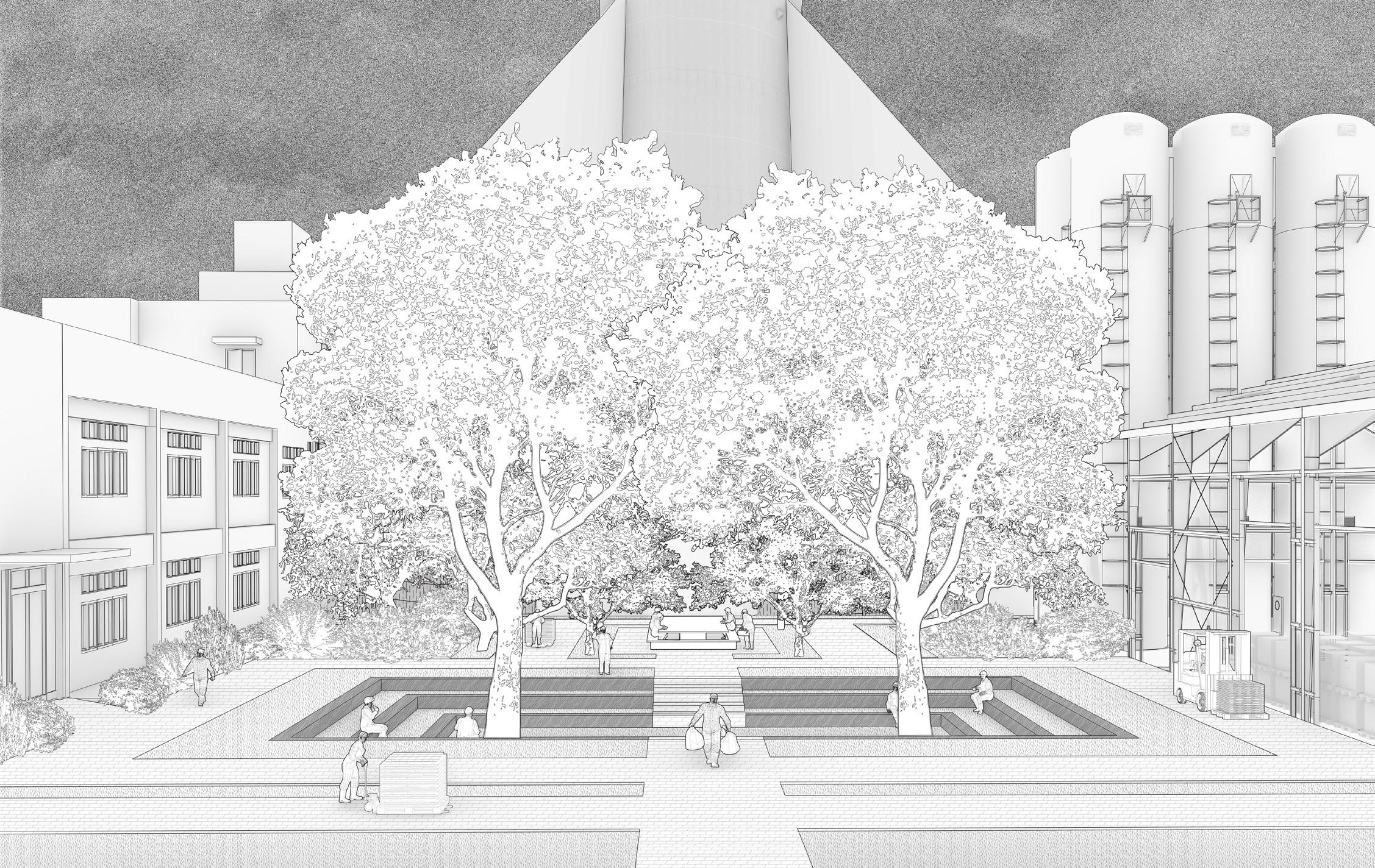

View of the central courtyard in the brick factory

53

View of ash extraction from landfill

54

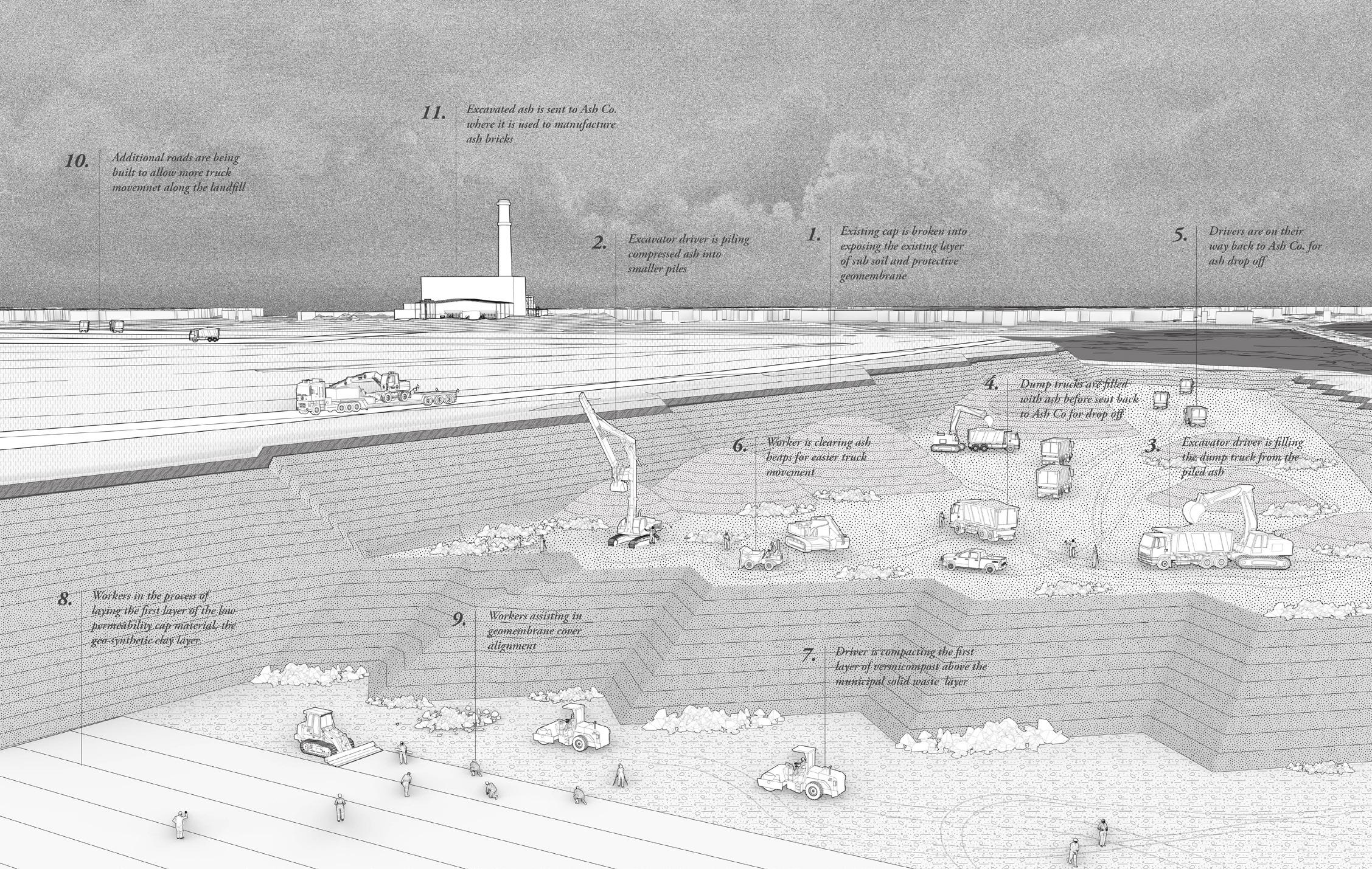

Potential restoration of Rumney Marshes original area.

Potential restoration of Rumney Marshes original area.

55

New proposed network: Wheelabrator starts to collect ash from neighboring ash monofills to produce ash bricks.

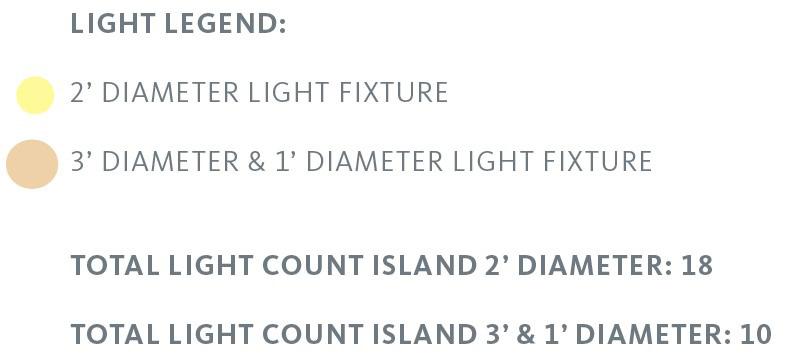

Nestle Bentonville, Arkansas

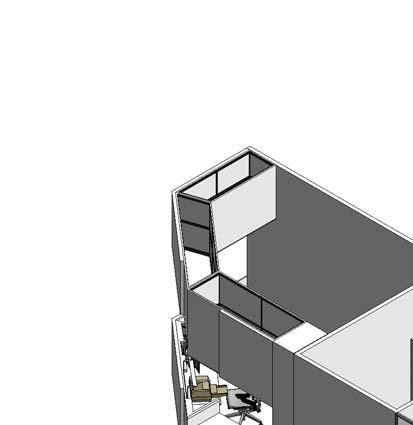

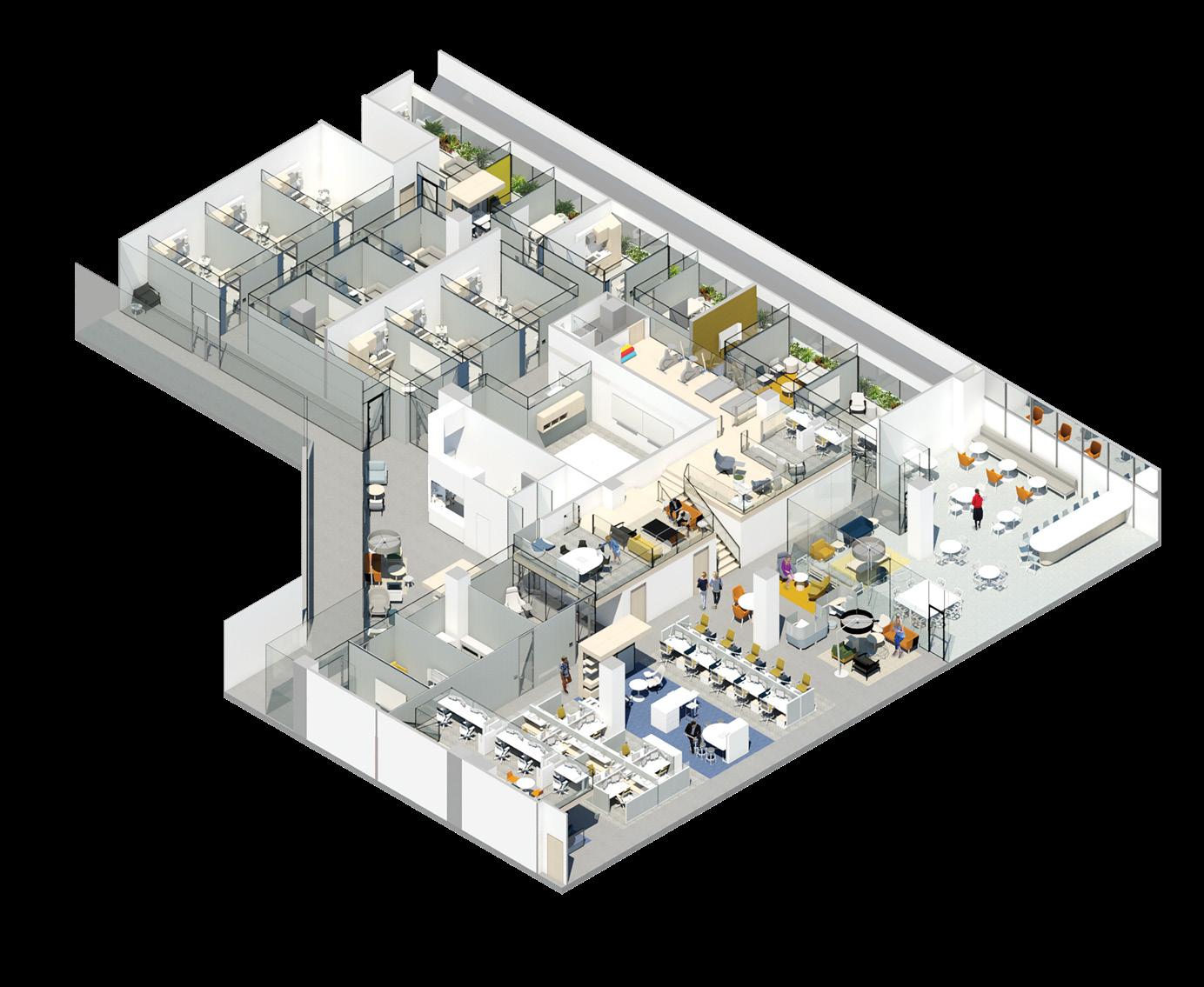

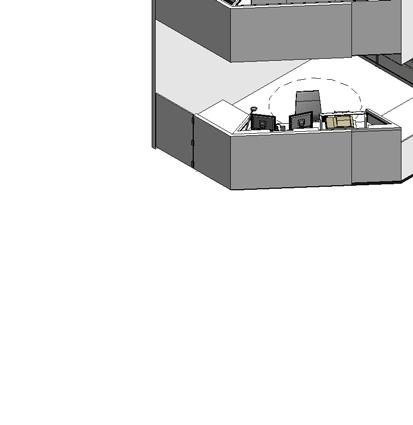

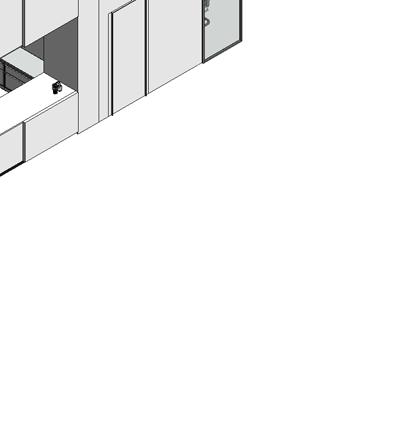

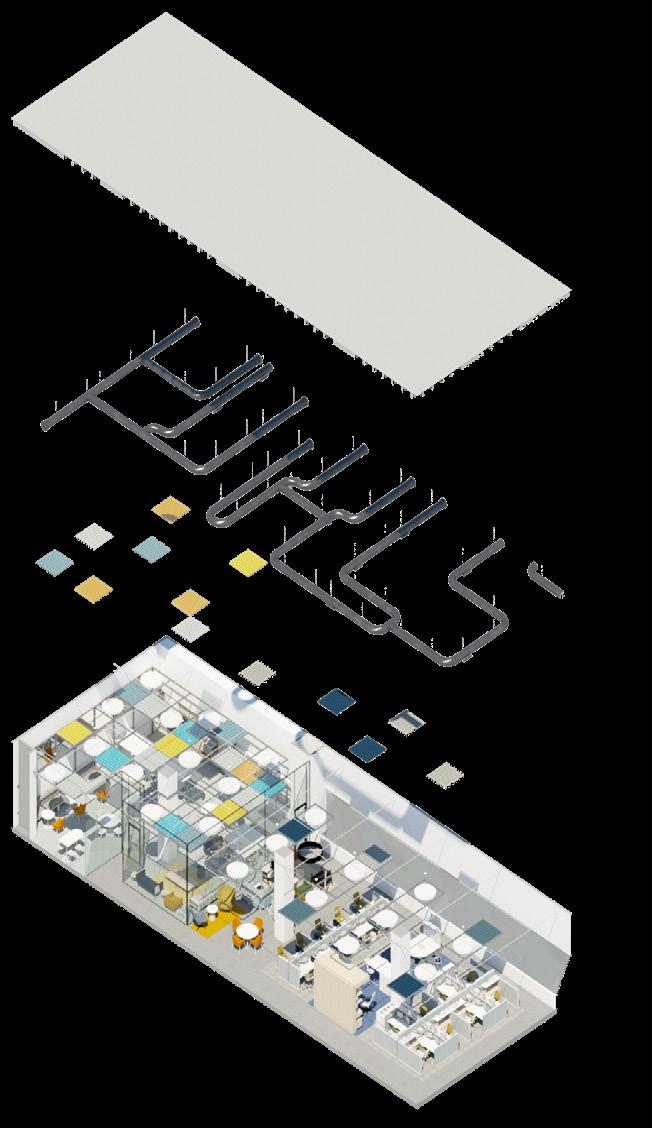

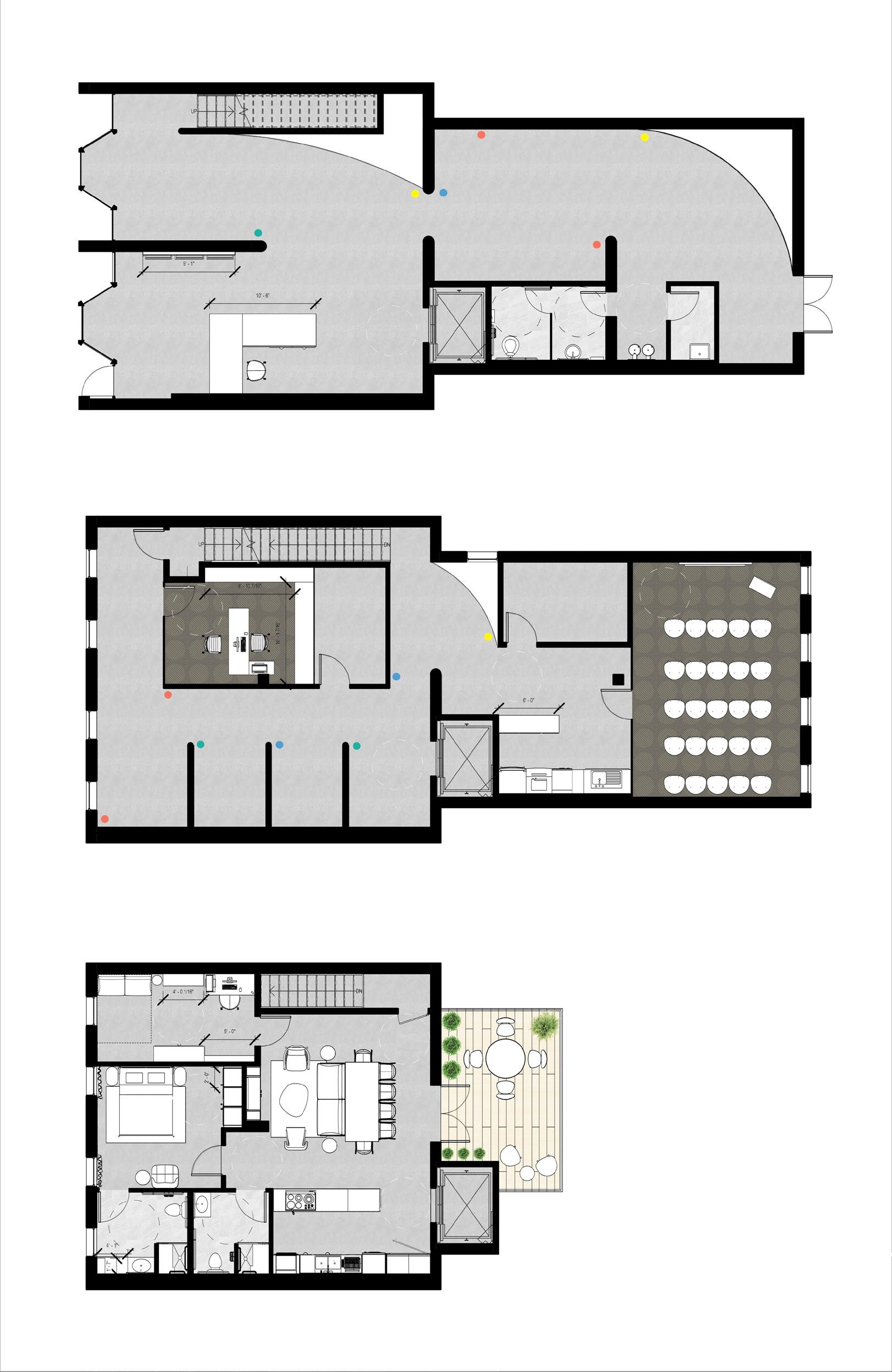

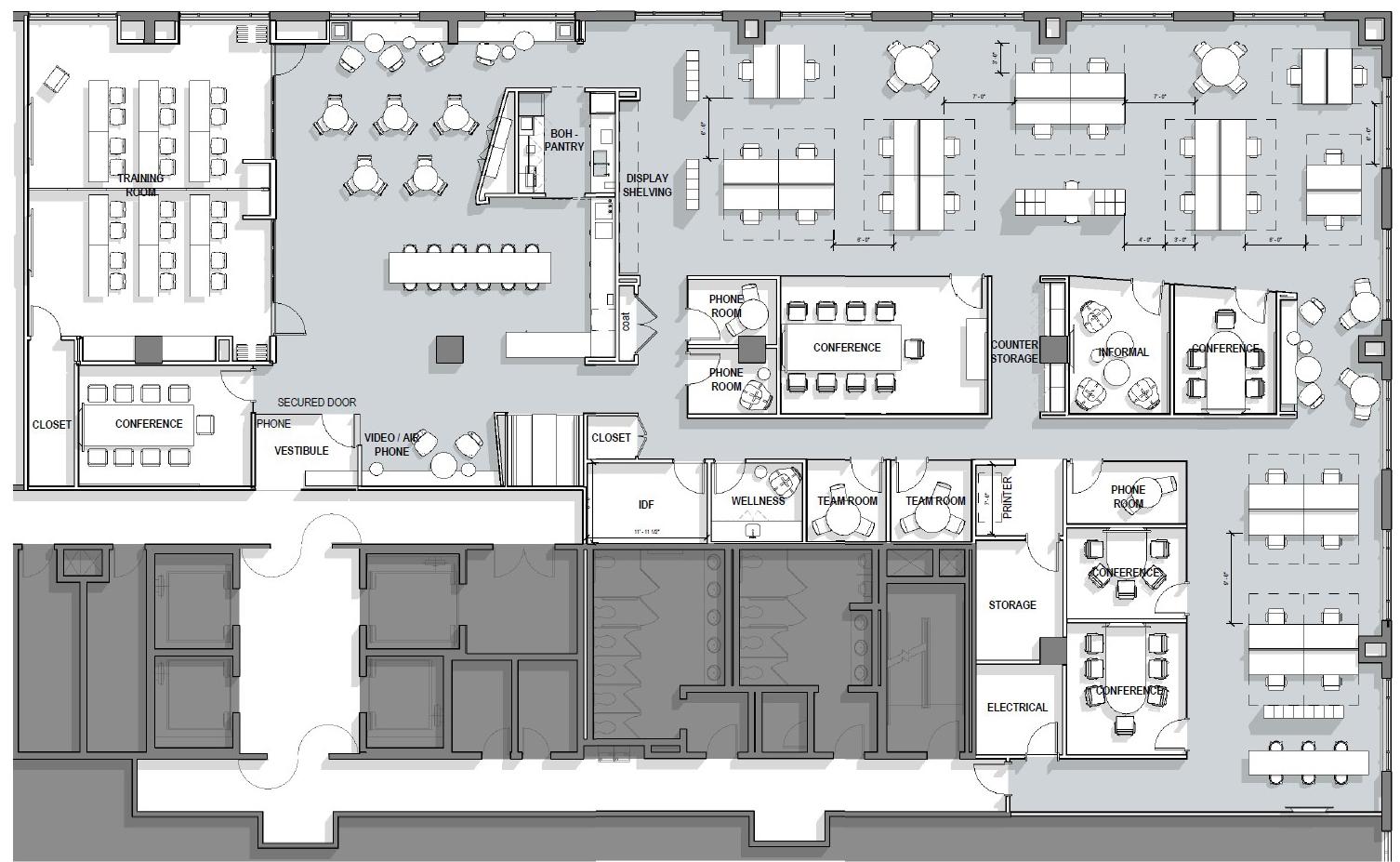

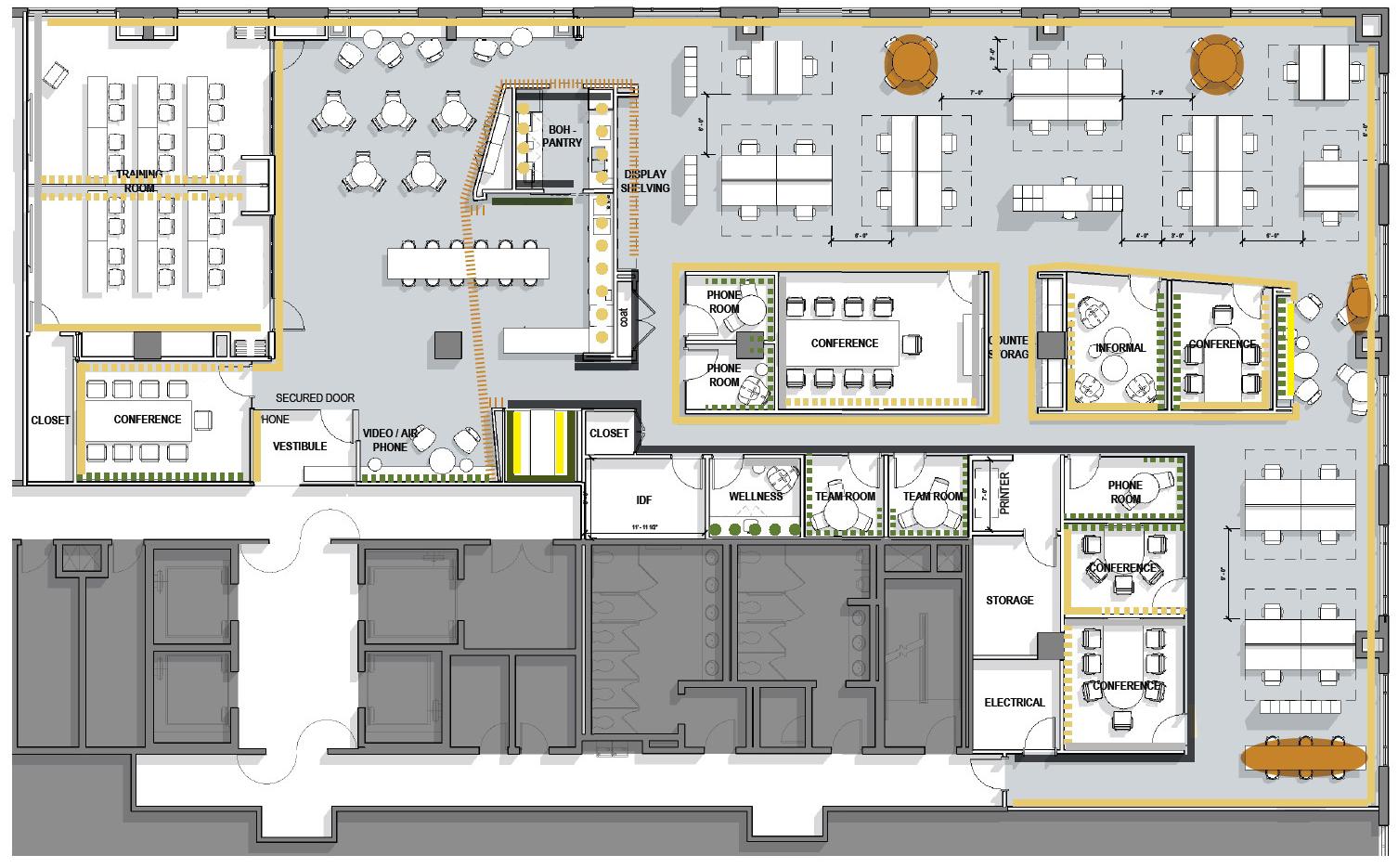

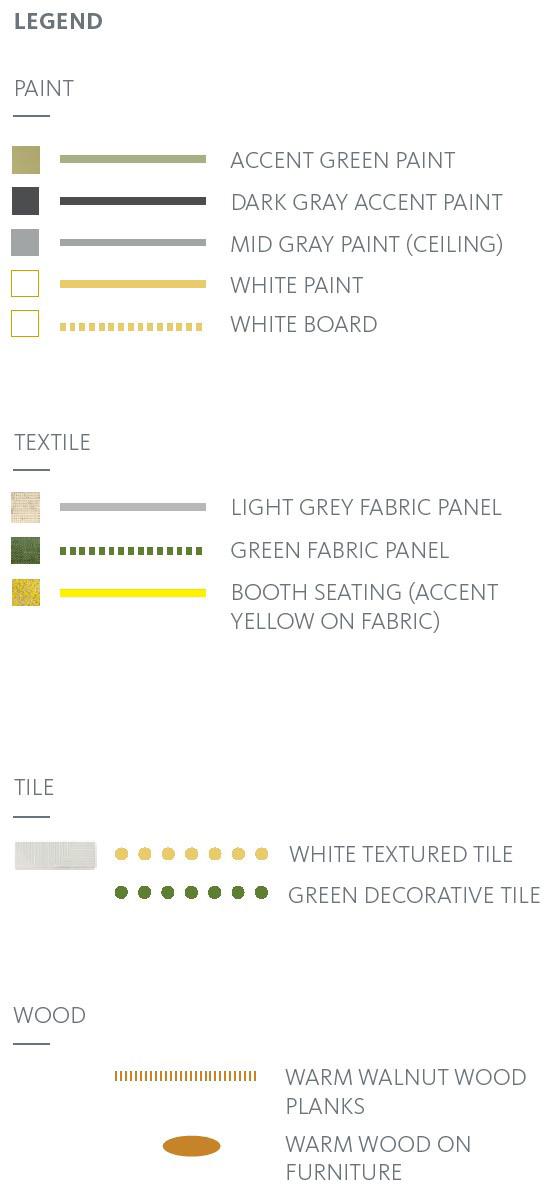

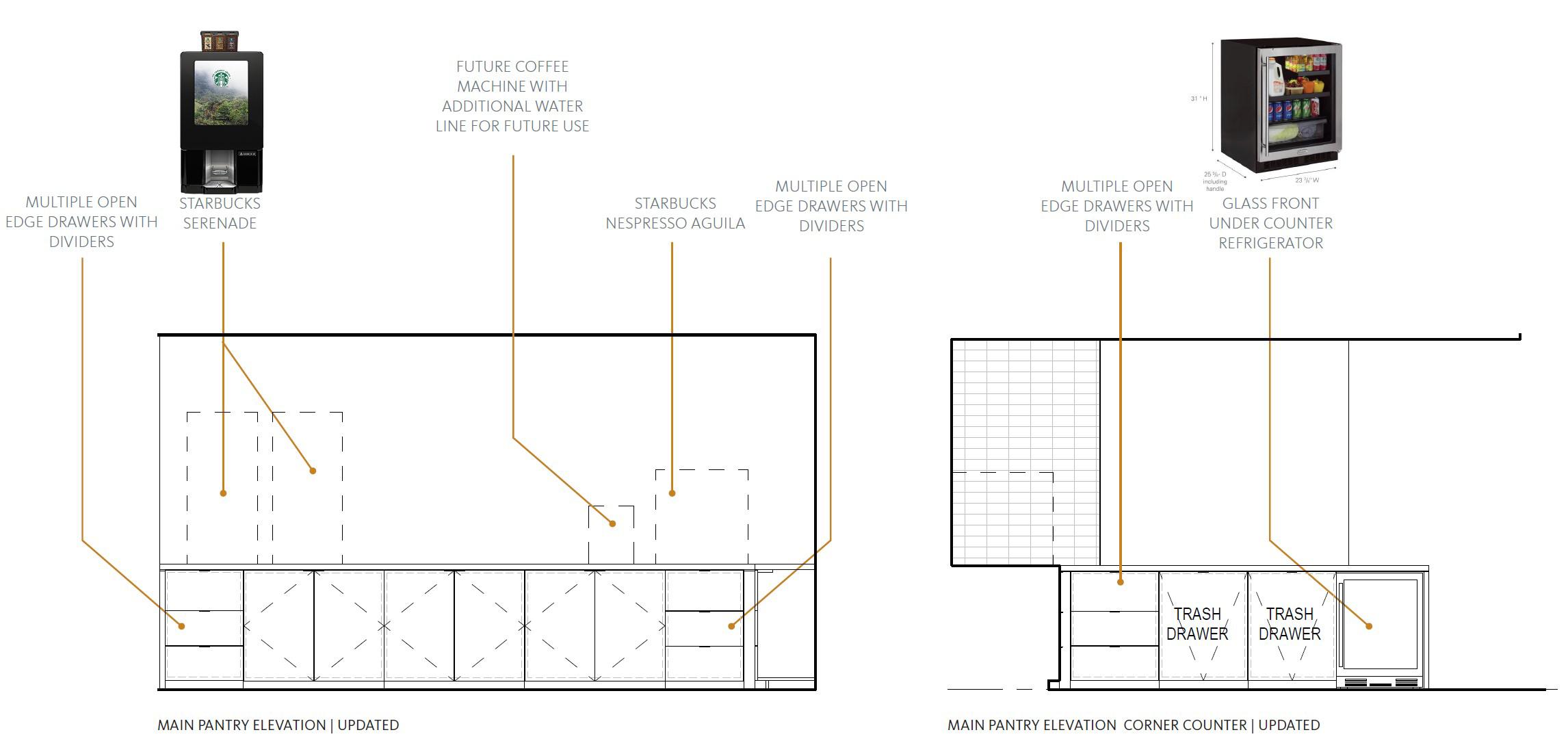

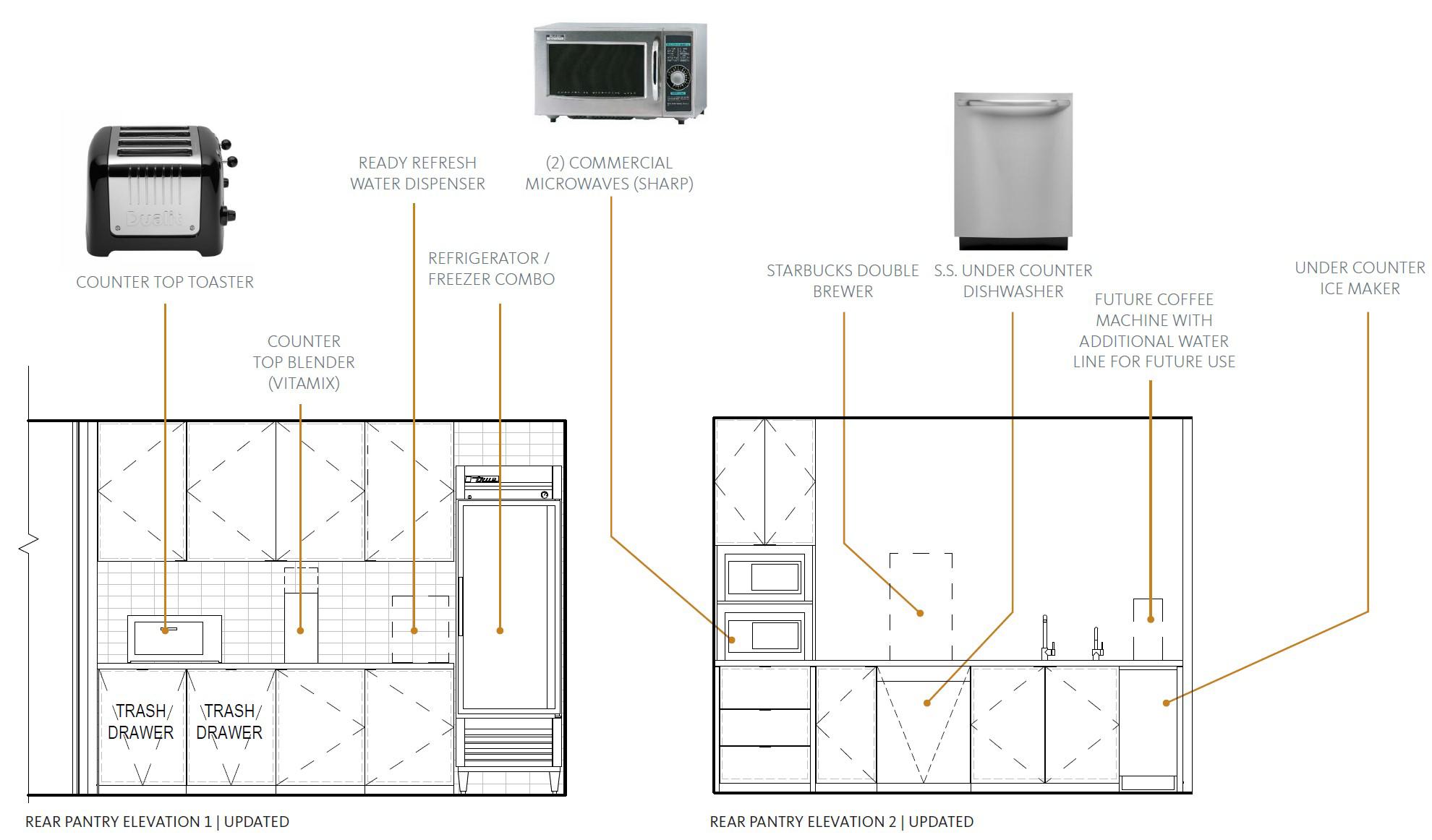

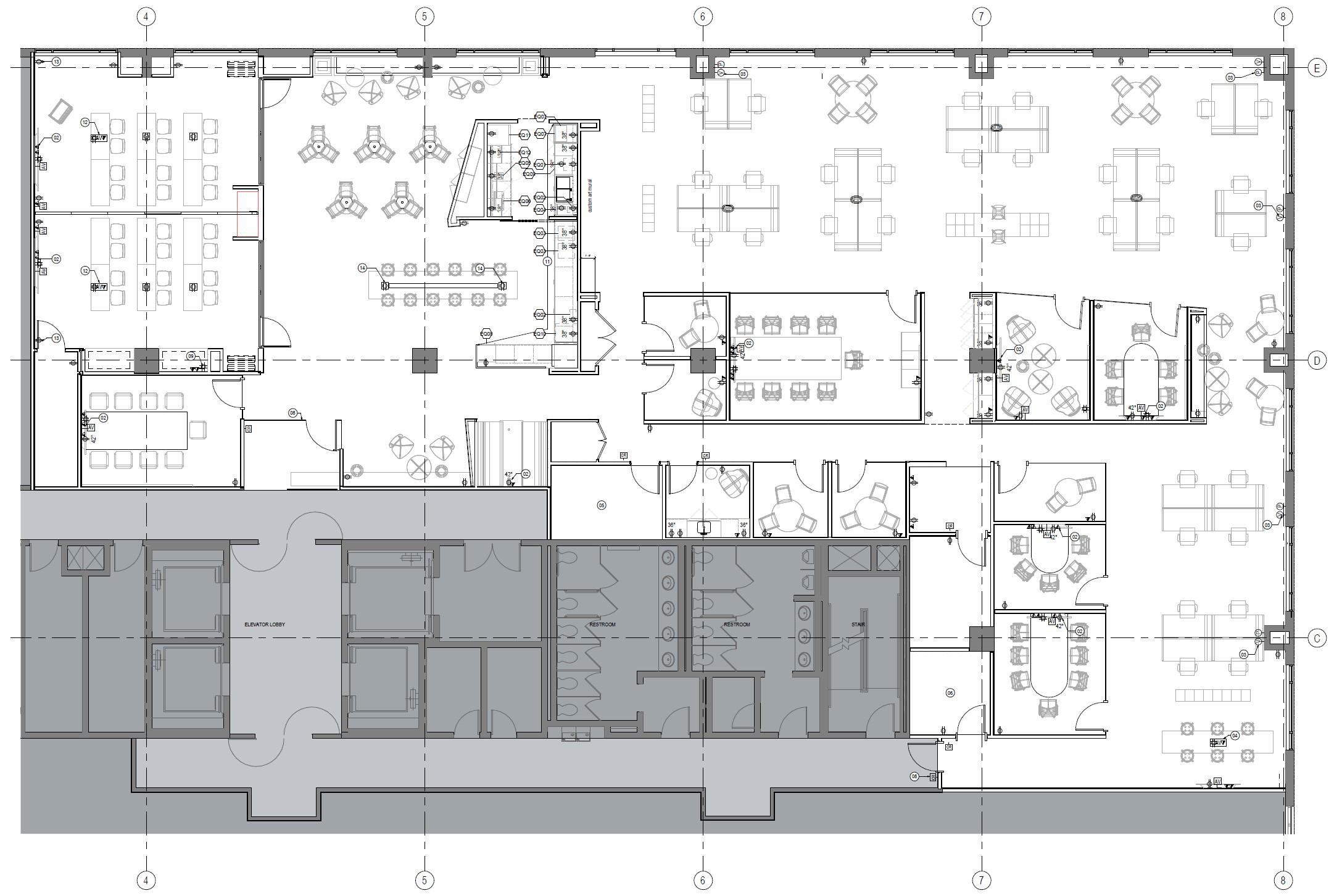

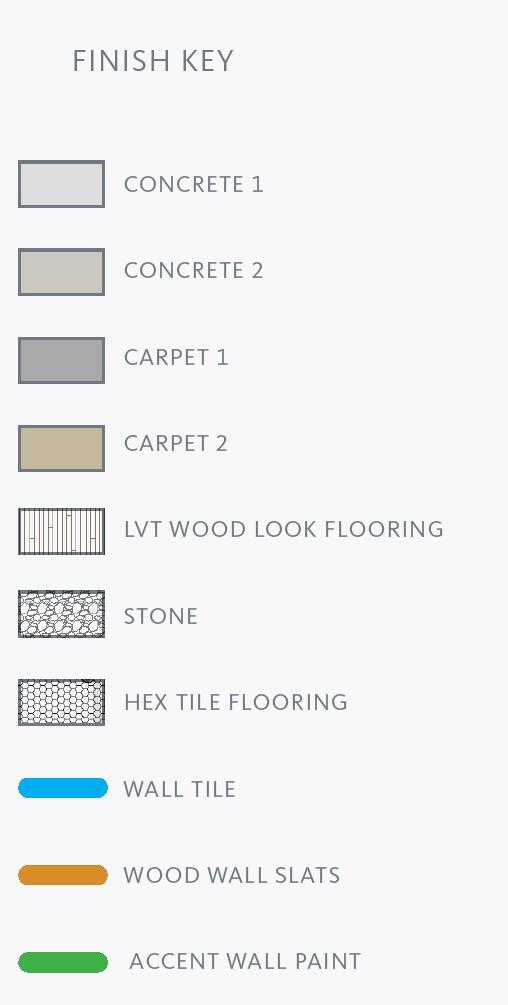

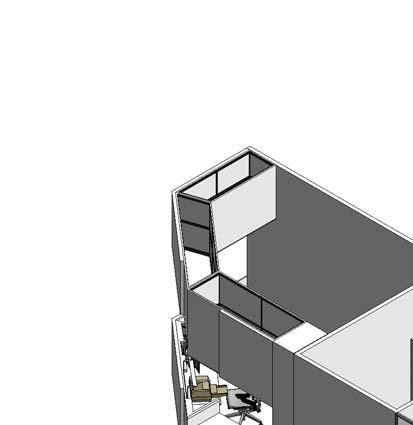

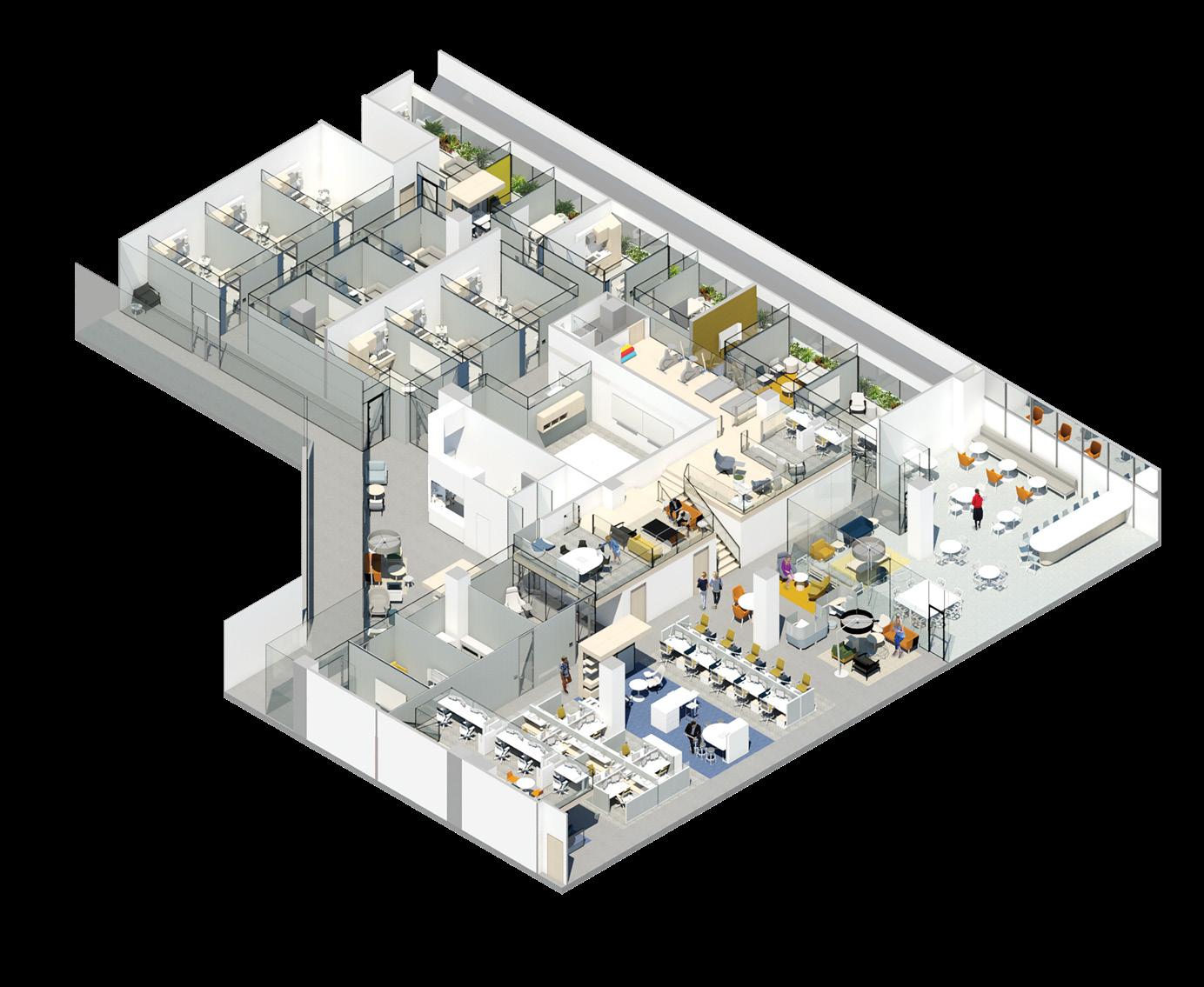

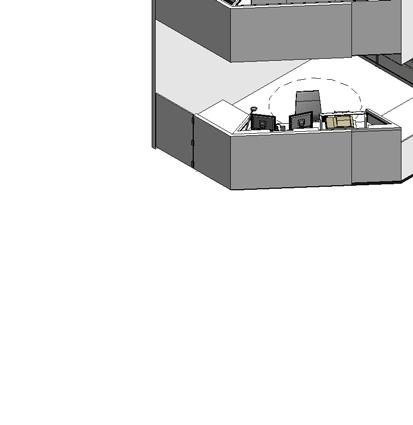

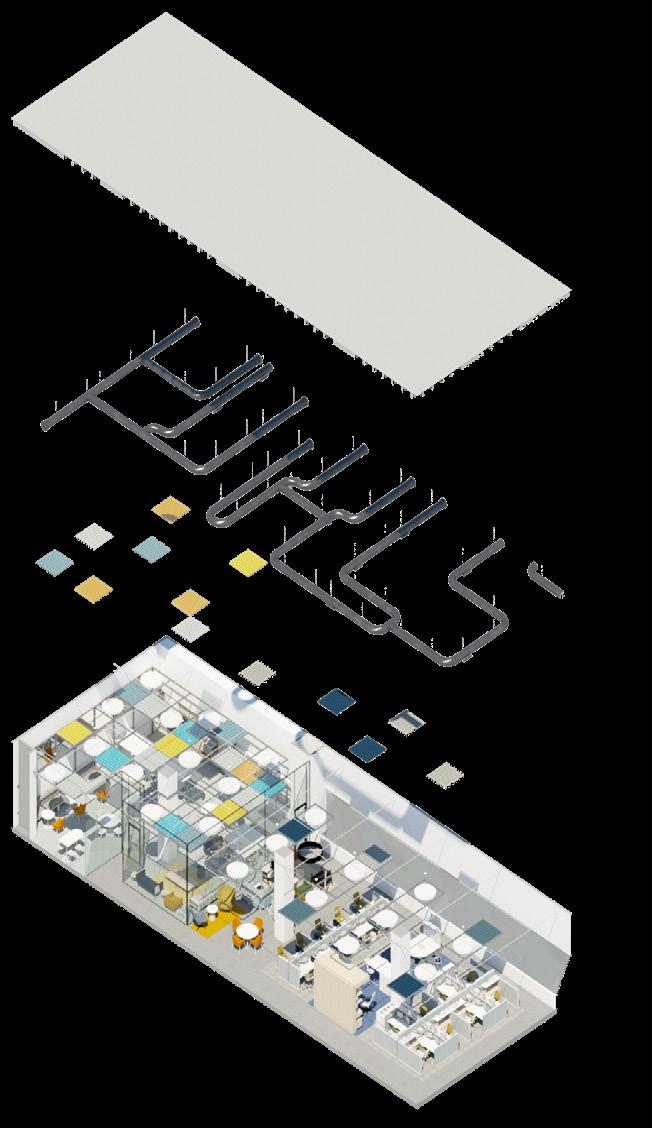

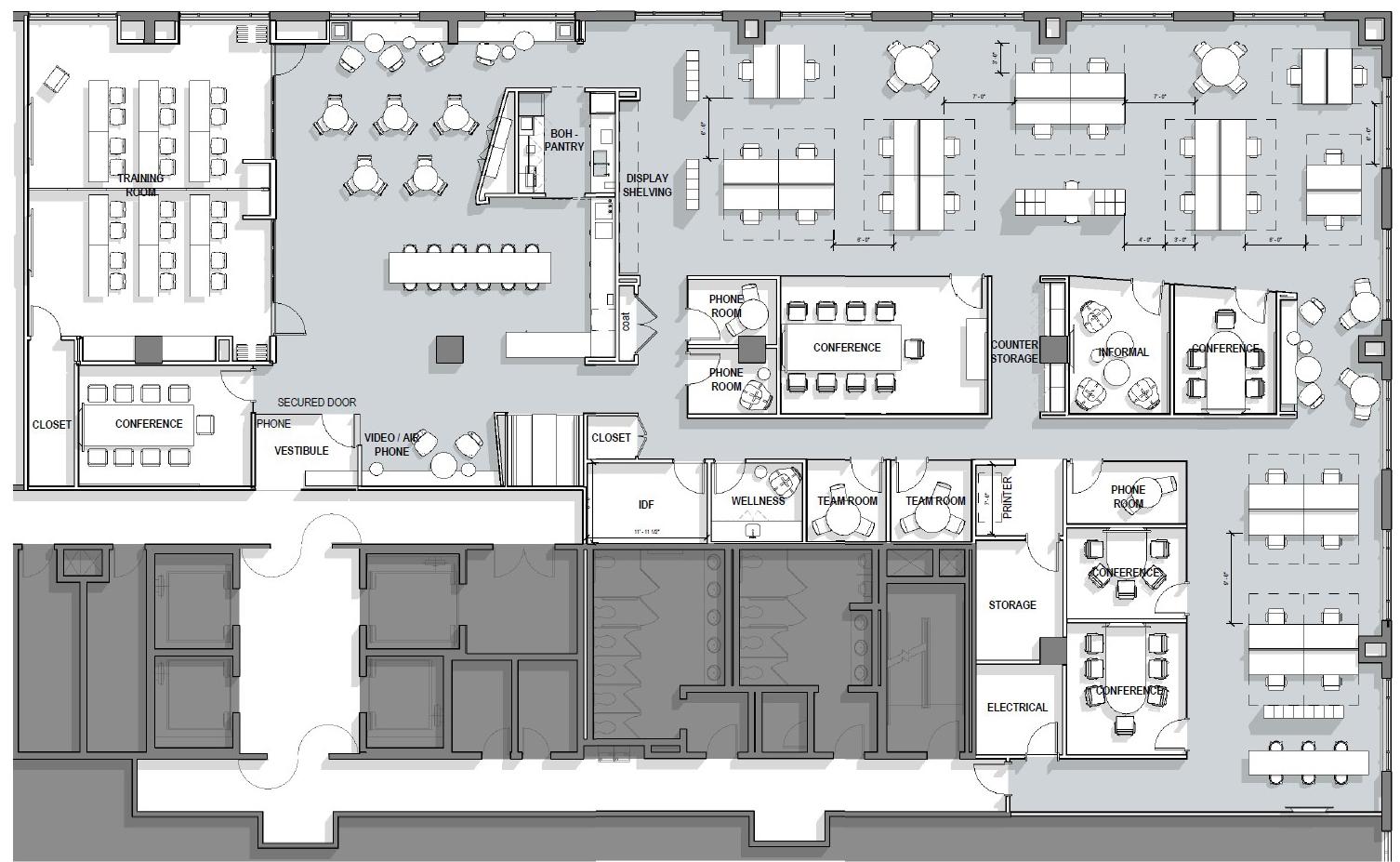

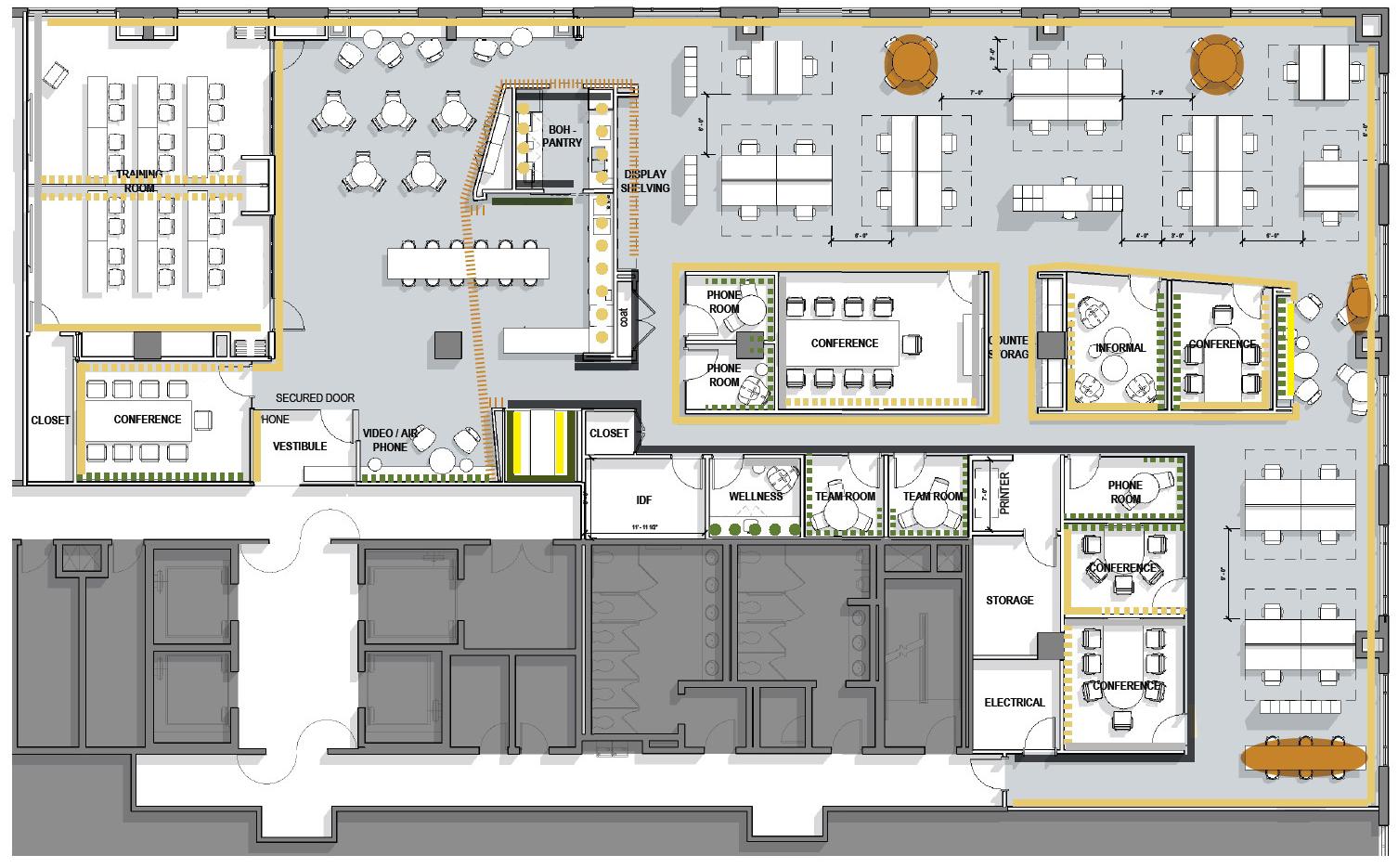

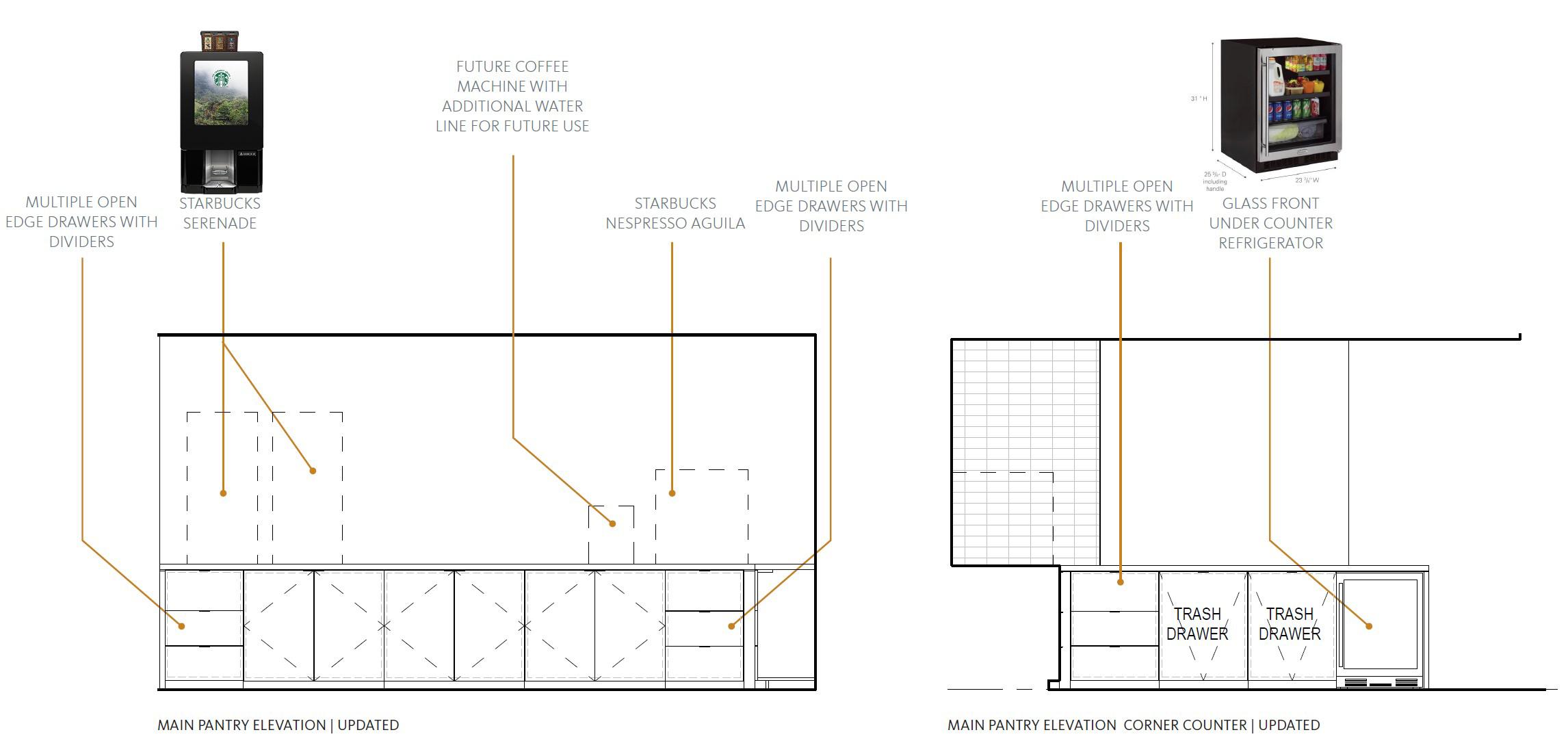

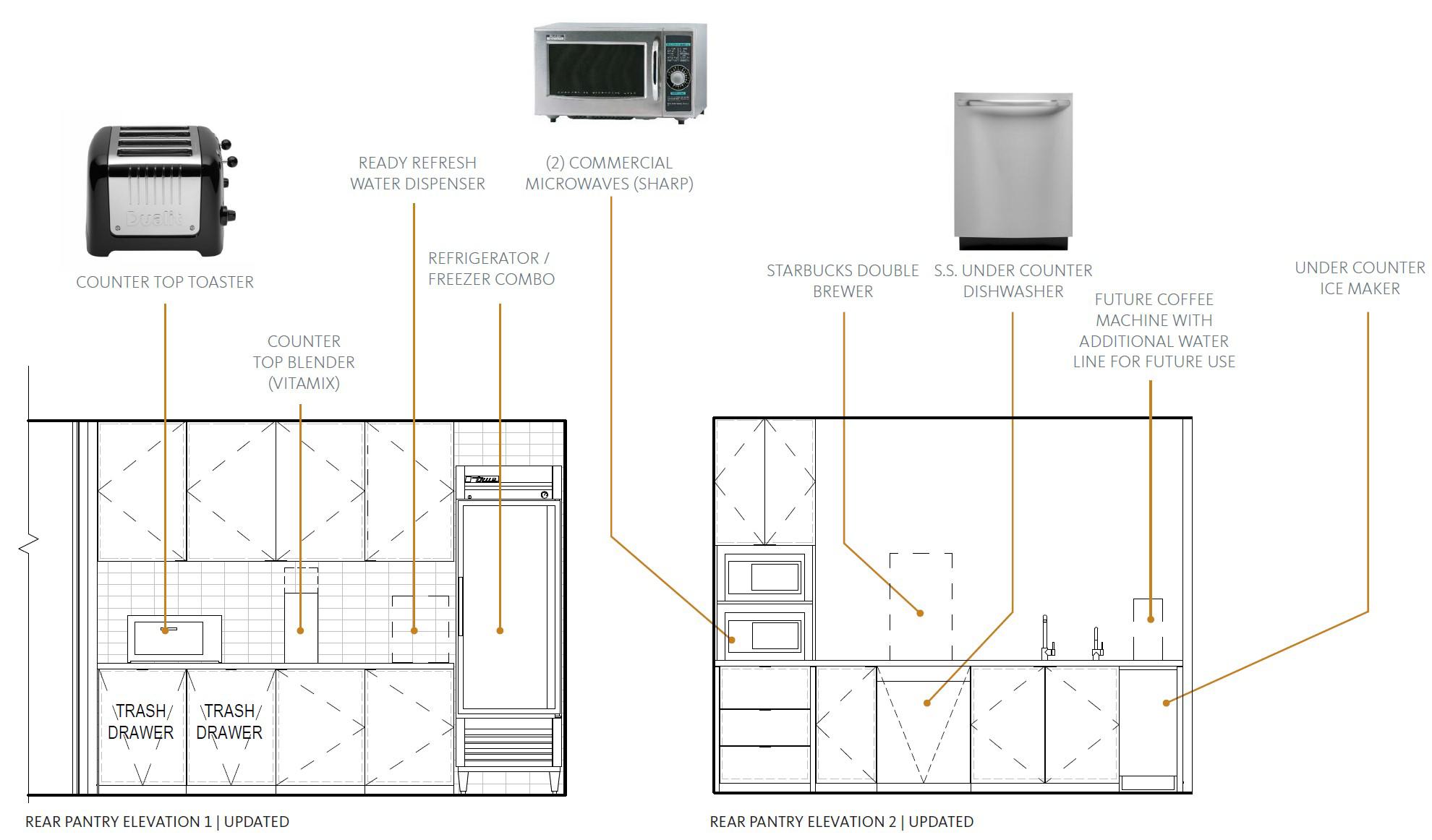

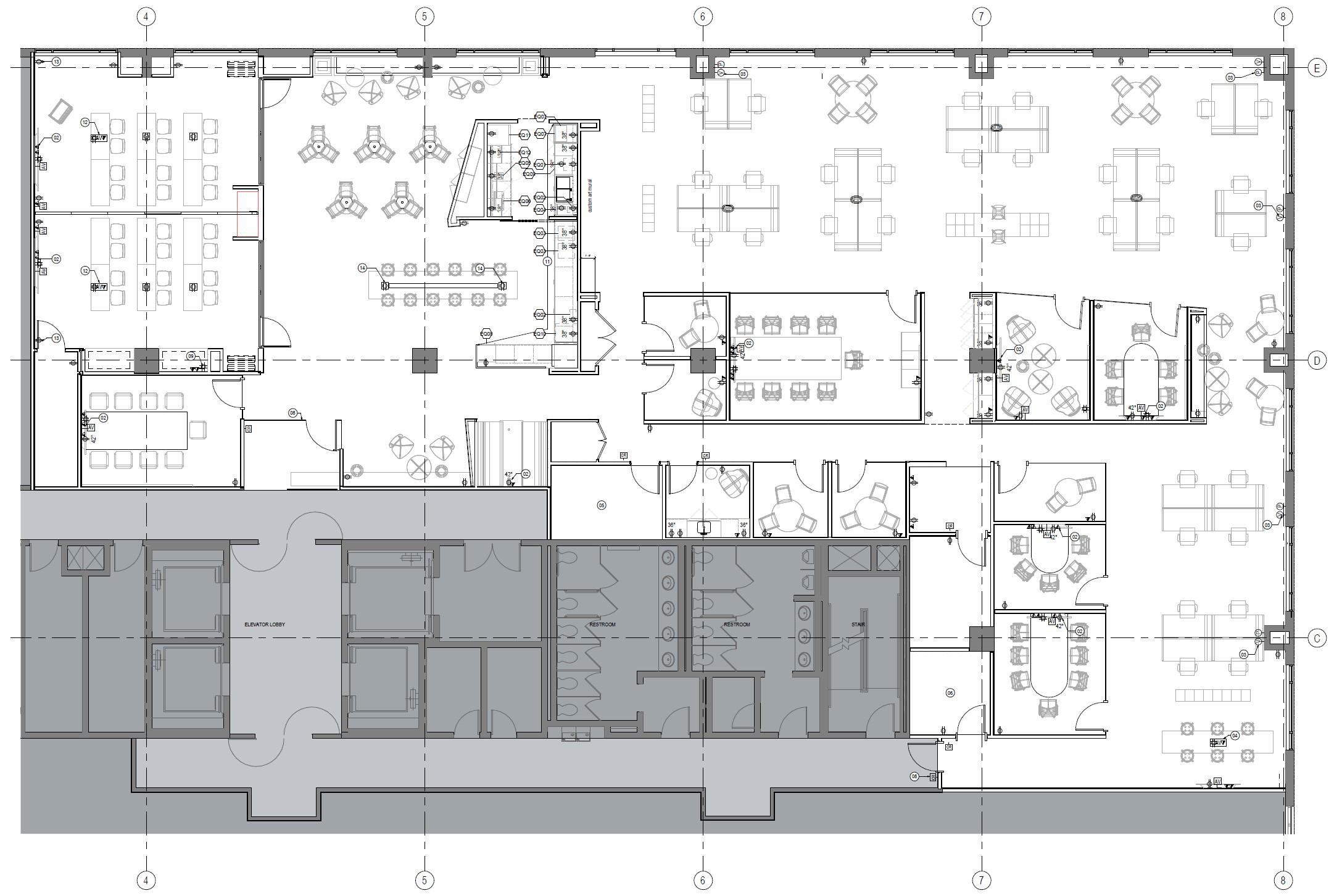

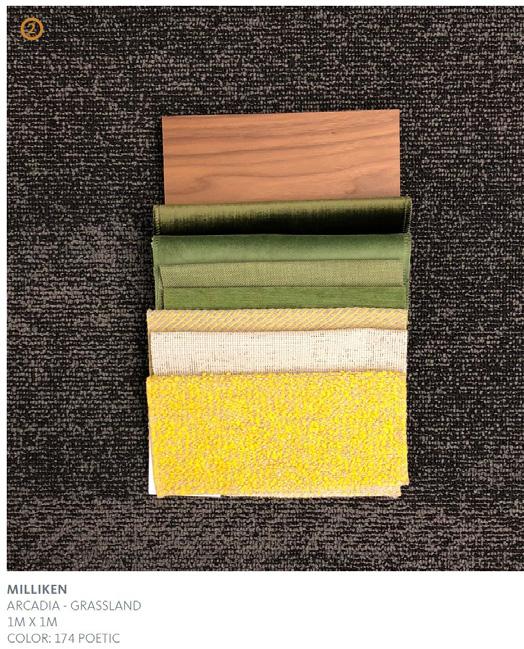

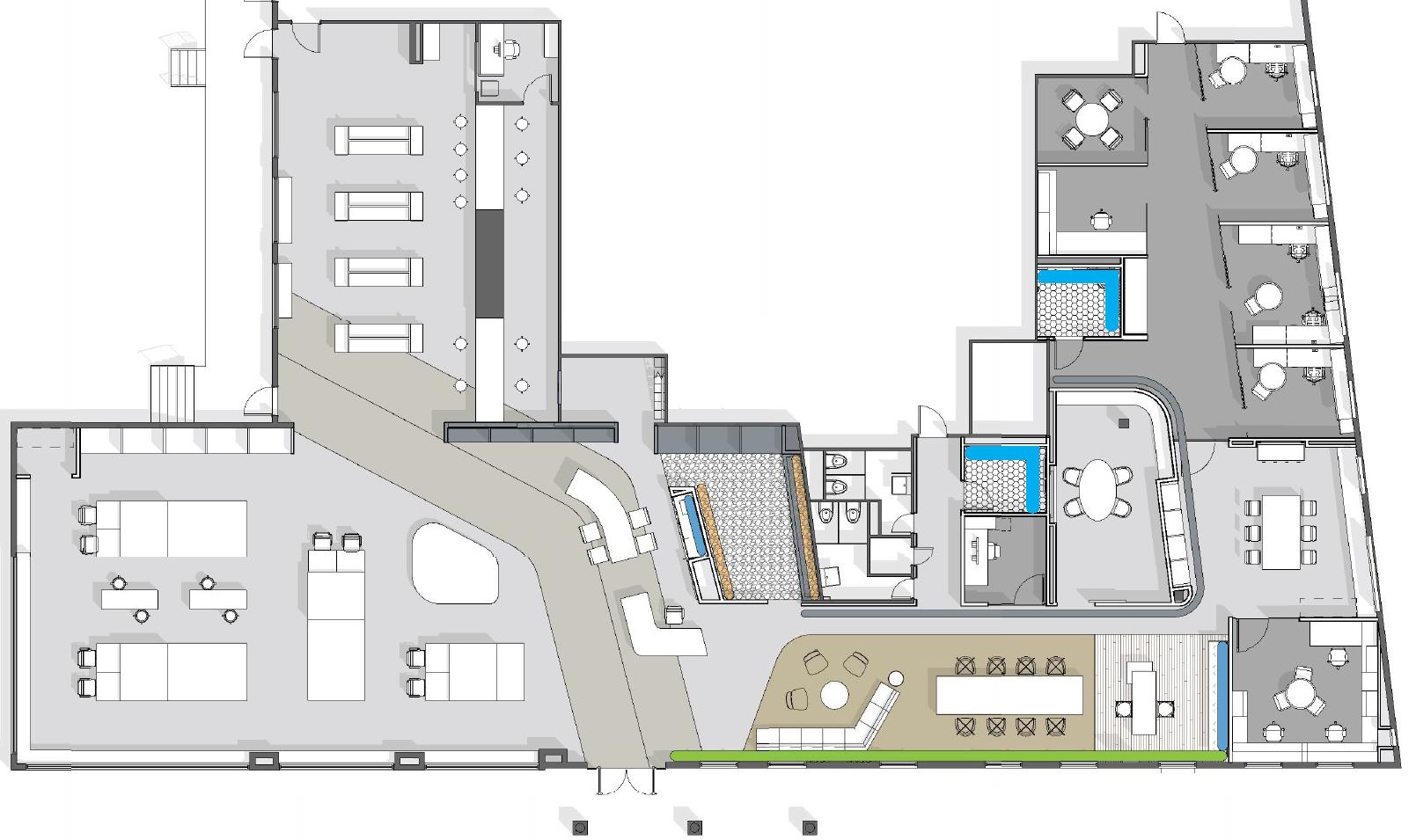

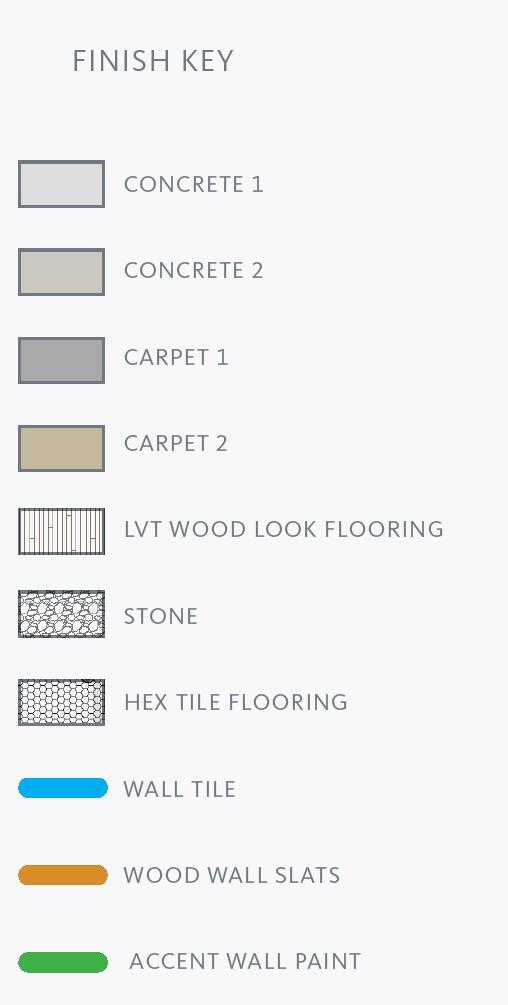

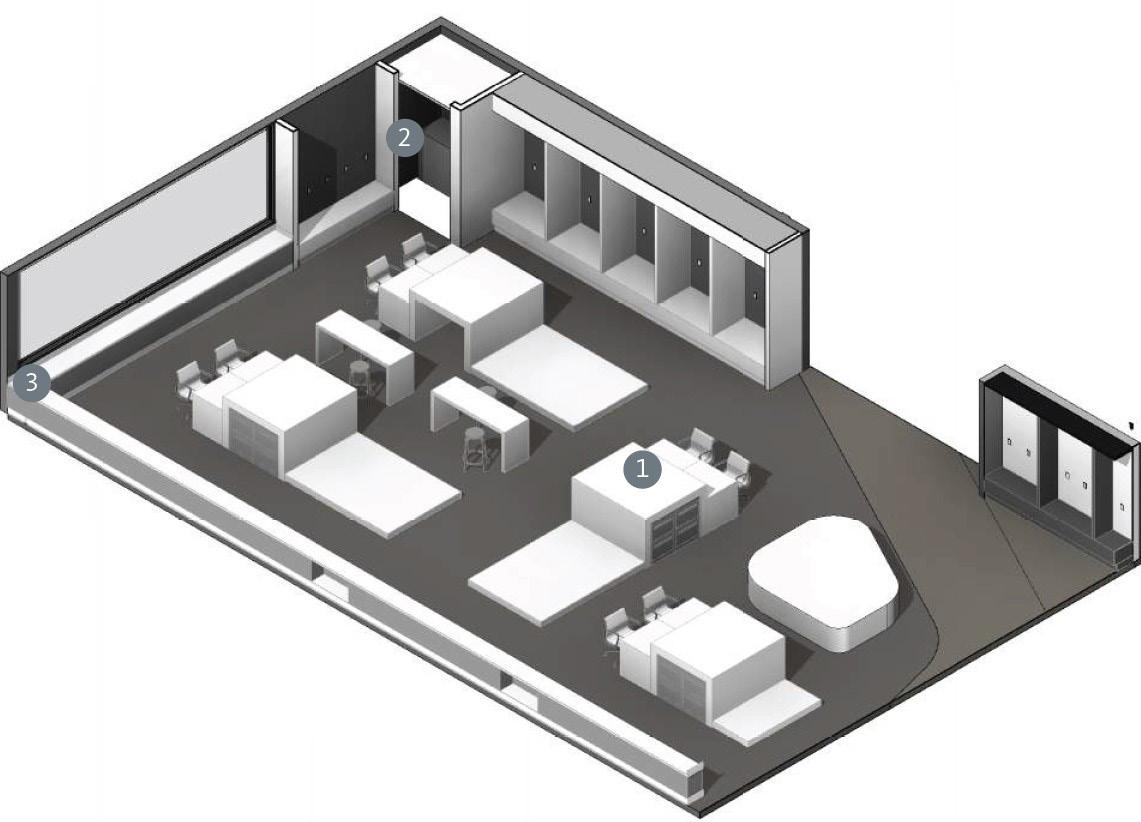

The Gensler design team was tasked to design Nestle’s newest satellite office in Bentonville, after the company bought the rights to distribute several Starbucks brands around the world in 2018. The goal was to include both Nestle and Starbucks employees in one satellite office, meaning the interior had to be branded neutrally. The clients had to meet a strict head count for the office, so the proposal was heavily influenced to fit as many employees in the space.

The design team included Jill Goebel, Tim Wright, Mayre Perez Velez, and myself. As technical designer, my duties included: preparing and being in-charge of the revit file, material selection, contacting corresponding material vendors, preparing client presentations, creating diagrammatic visualizations, working on the CD set, as well as detailing sections and elevations. All drawings included below were created by Reem Bukhamseen.

Floor Plan

Floor Plan

Plan 56

Wall Finish

Power and Communication Plan 57

Coffee Bar View

Coffee Bar View

58

Material Palette

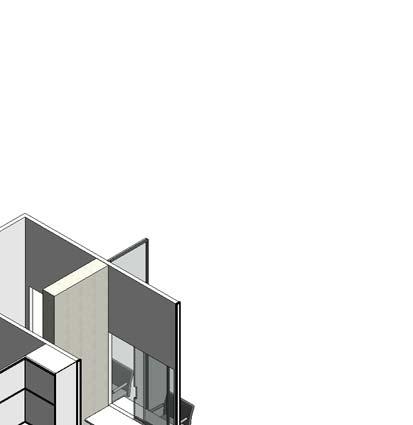

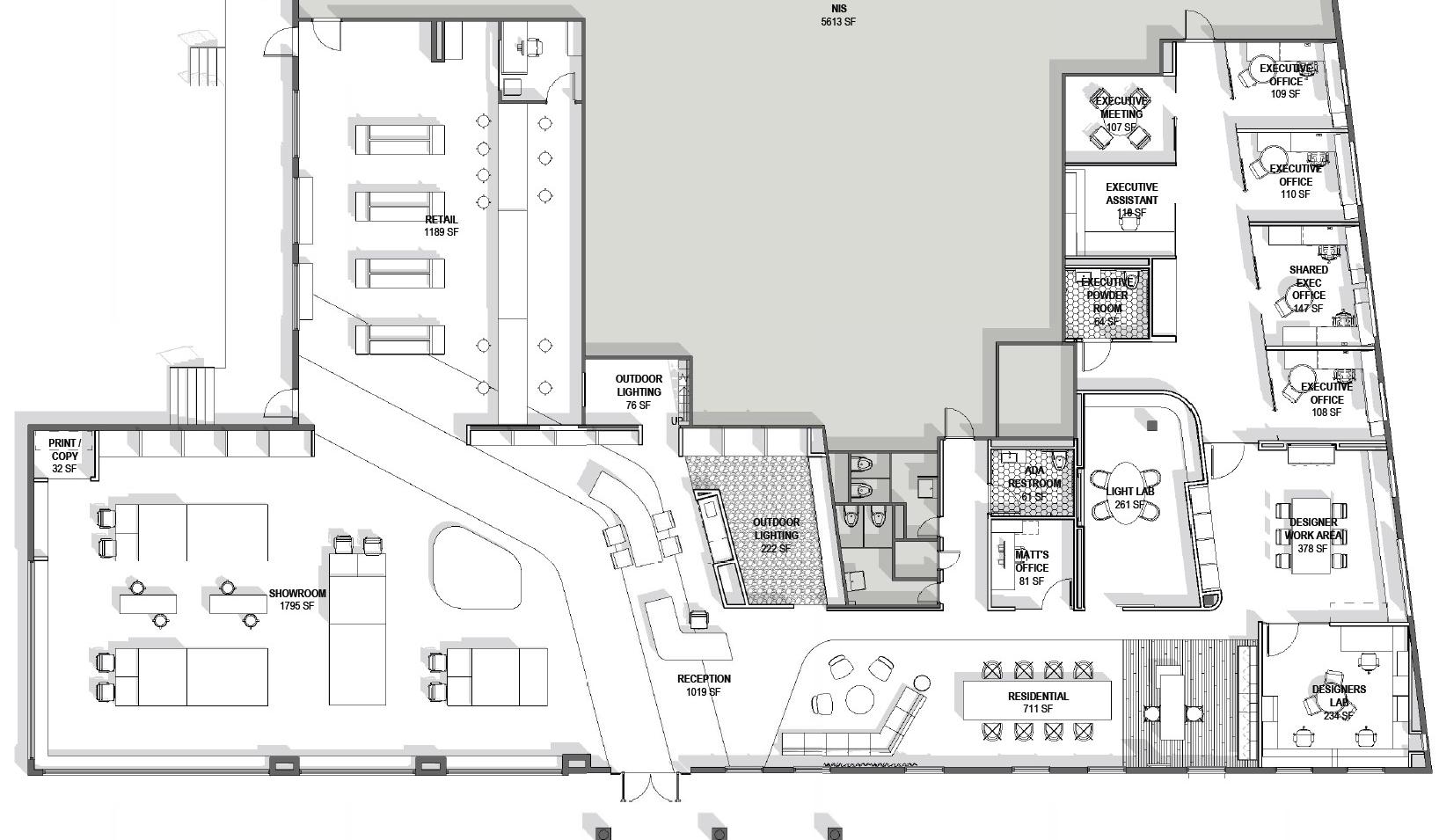

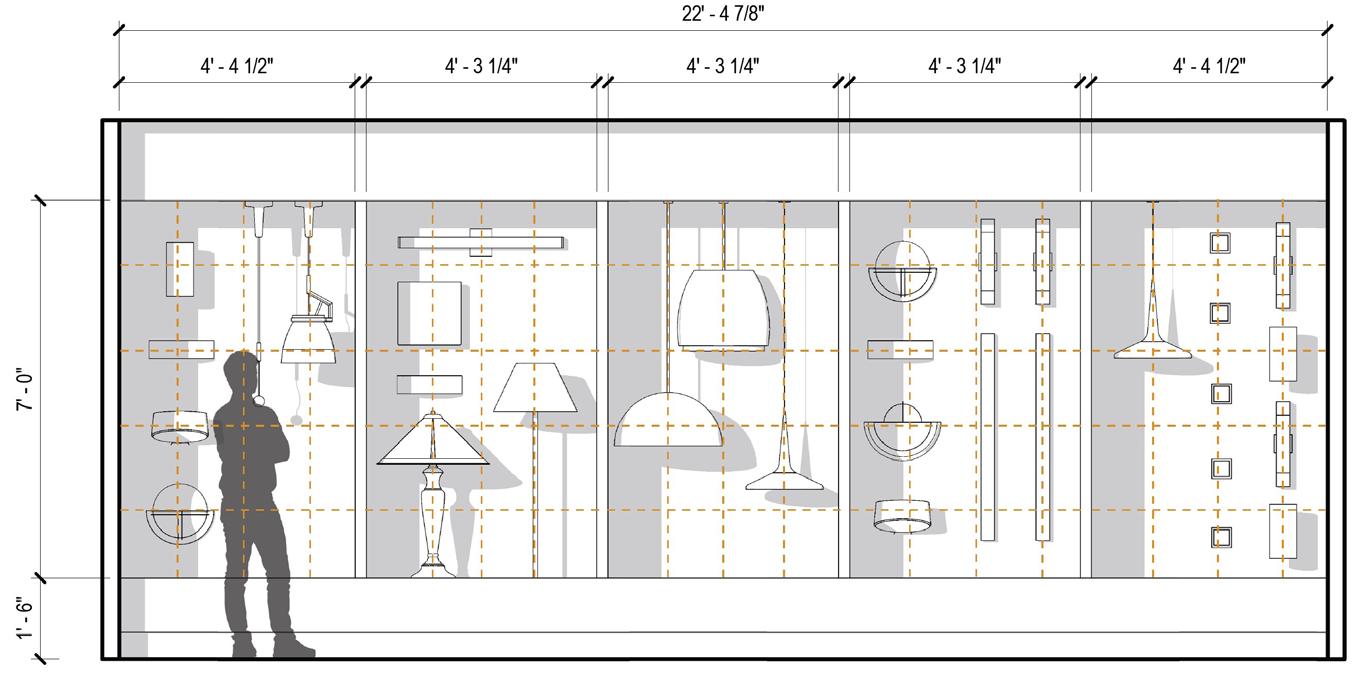

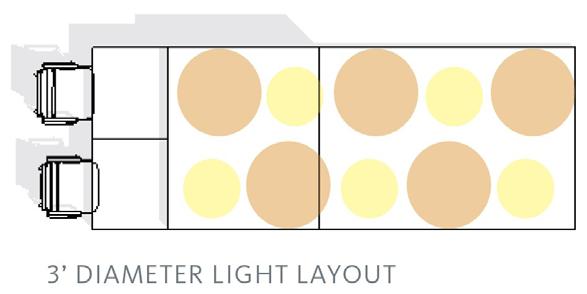

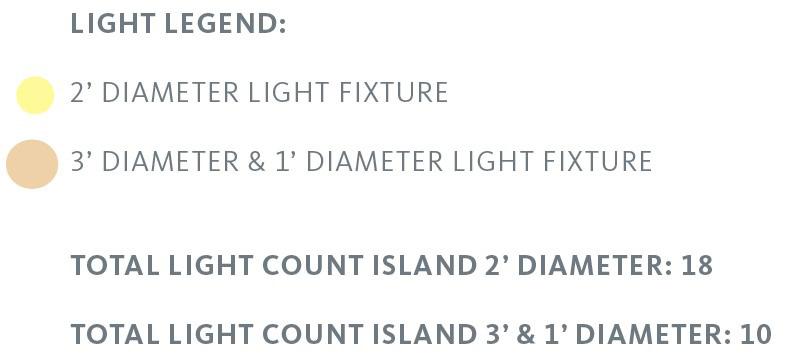

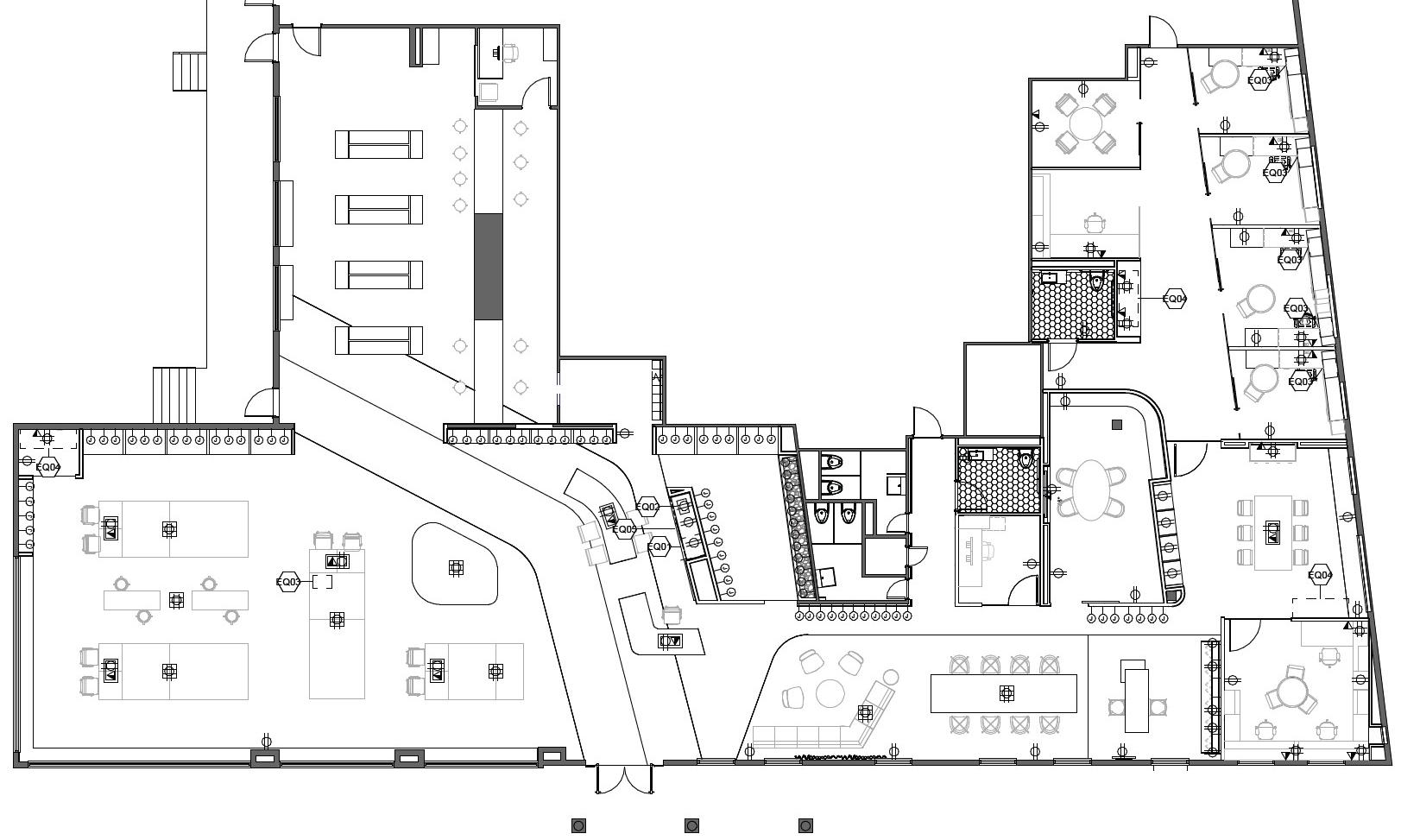

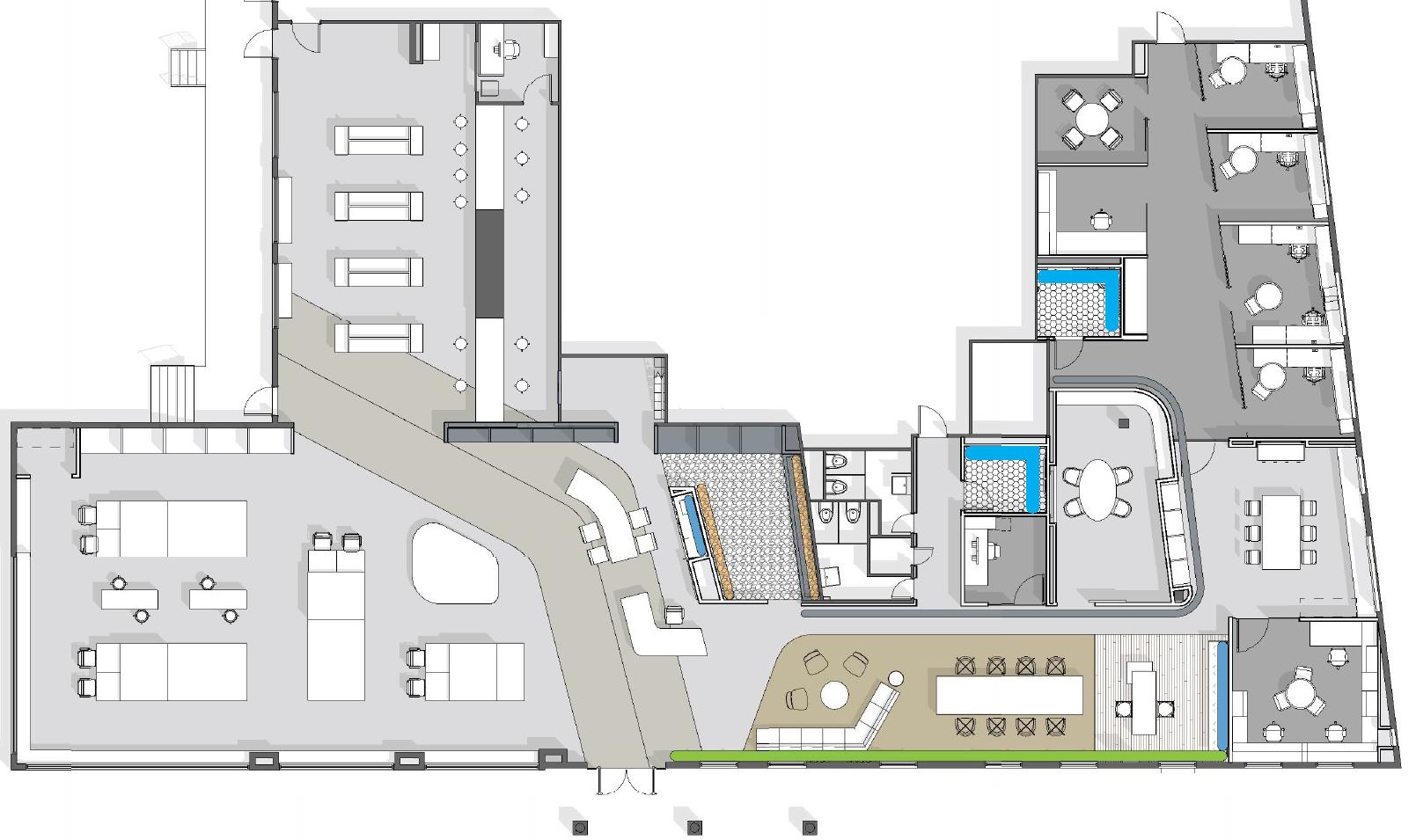

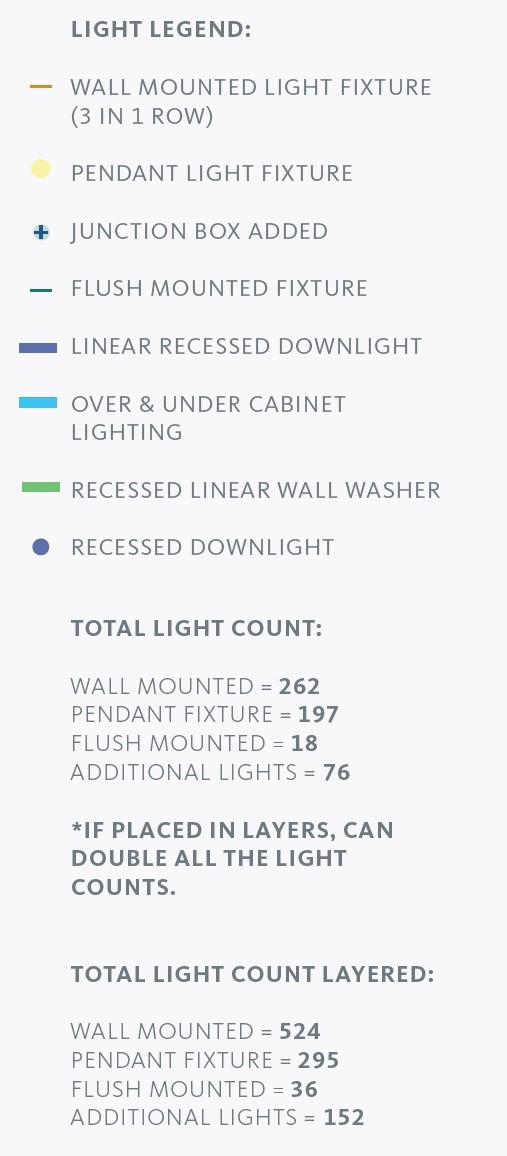

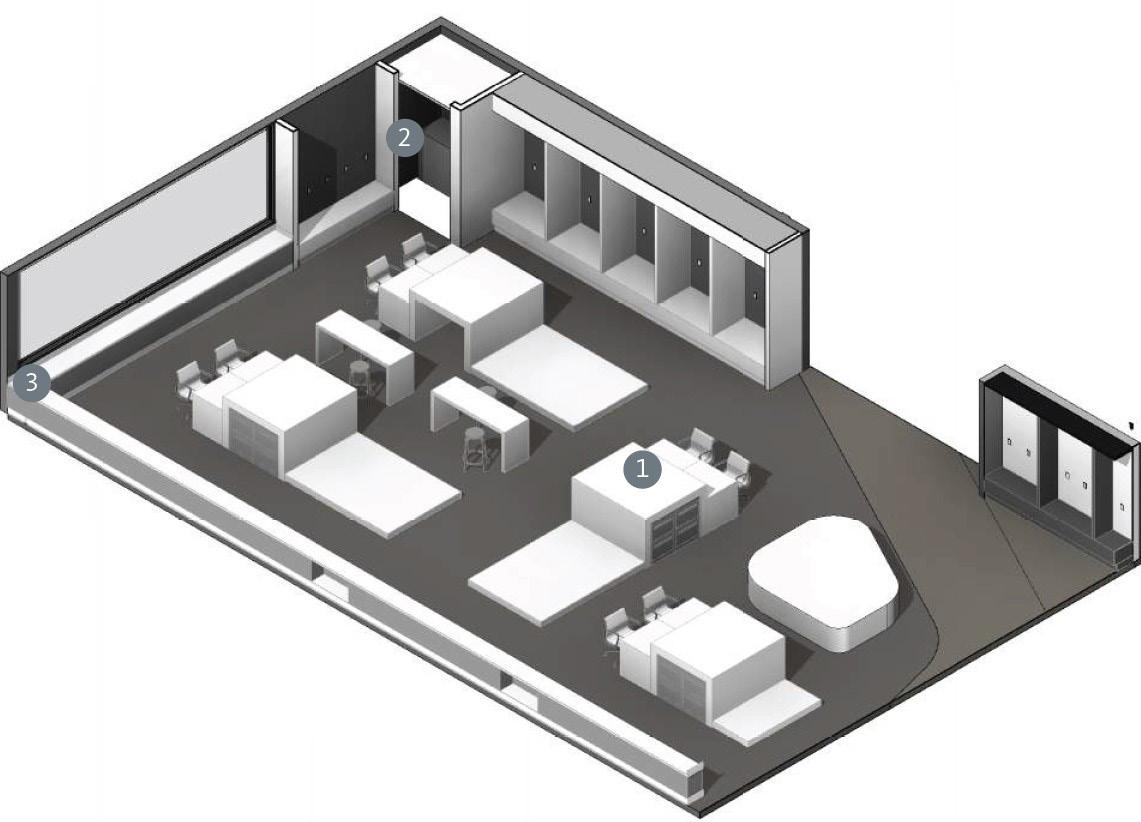

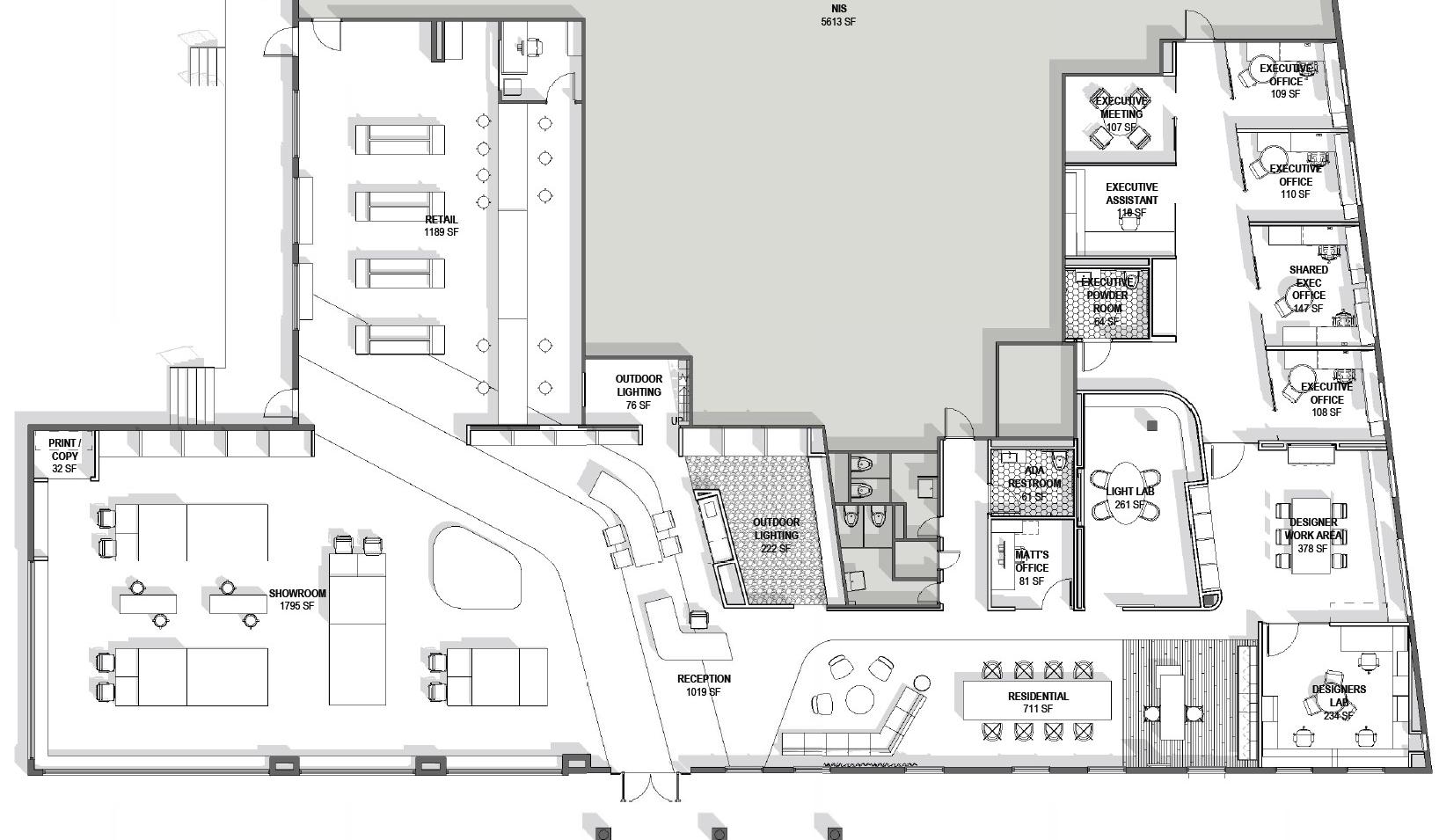

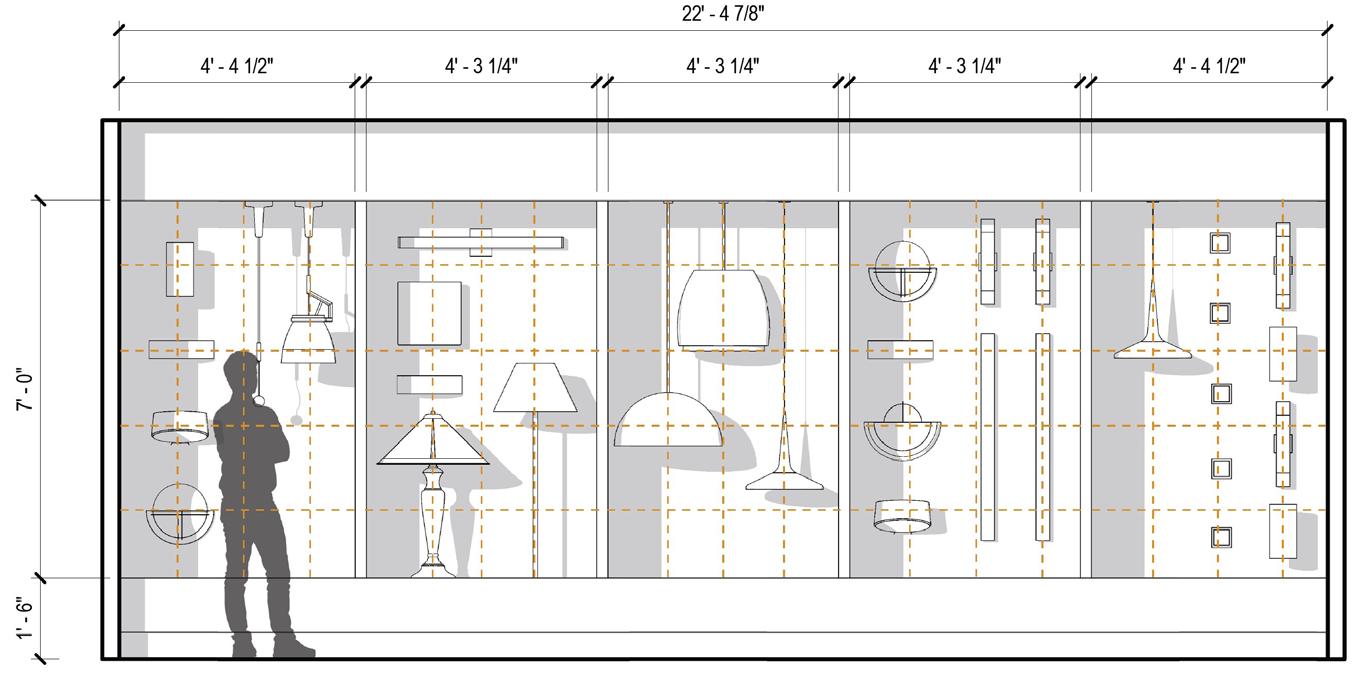

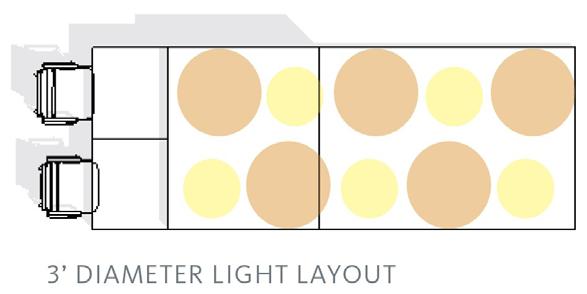

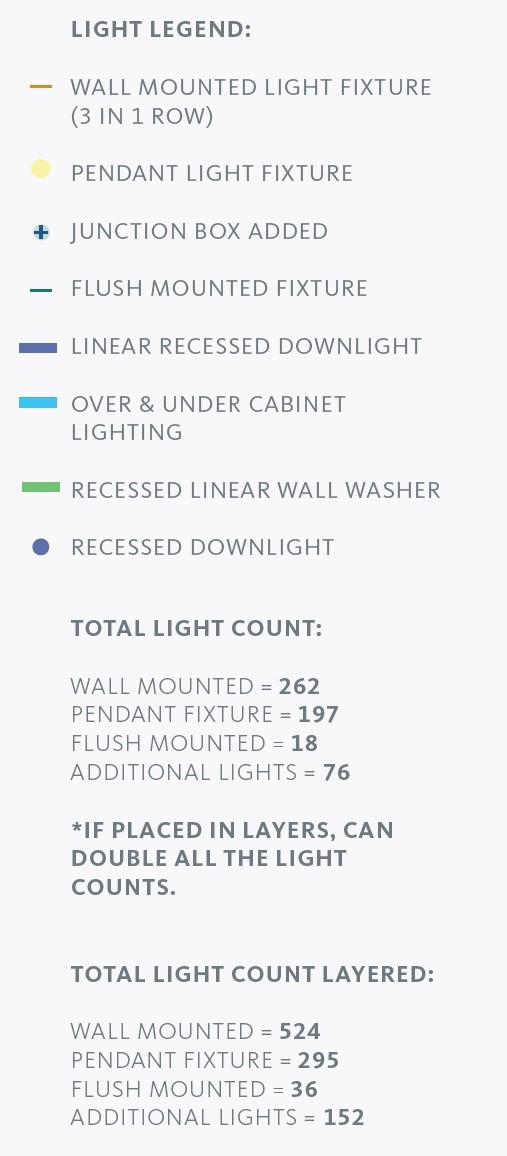

Dominion Electric Showroom, Arlington VA.

The Gensler design team was tasked to redesign the already existing Dominion Electric Showroom in Arlington, VA. The clients envisioned a more modernized showroom, that would showcase newer product lines, allow more fixtures to be displayed, and provide more functional workspaces. The interior was designed to maximize surface areas to display as many fixtures as possible at once, which included multipurpose custom buit funiture, as well as the integration of deconstructed residential rooms to act as backdrops to showcase fixtures to the every-day consumer.

The design team included John Mckinney, Marc Herndon, Jessica Alpert, Farrah Goal, Sarrah Stough, Patrick Foley, and myself. As technical designer, my duties included: surveying the existing interior, creating the revit file, material selection, preparing all design presentations, creating diagrammatic visualizations, working on the CD set, as well as detailing sections and elevations. All drawings included below were created by Reem Bukhamseen.

*Photographs of completed project are courtesy of Dominion Electric Interactive Website.

Plan Completed Lighting Display Proposed Lighting Display Organization 59

Floor

Reflected Ceiling Plan Power and Data Plan Finish Plan 60

ReceptionArea

MainLightingShowroom

ResidentialShowroom

Designer’sWorkArea

61

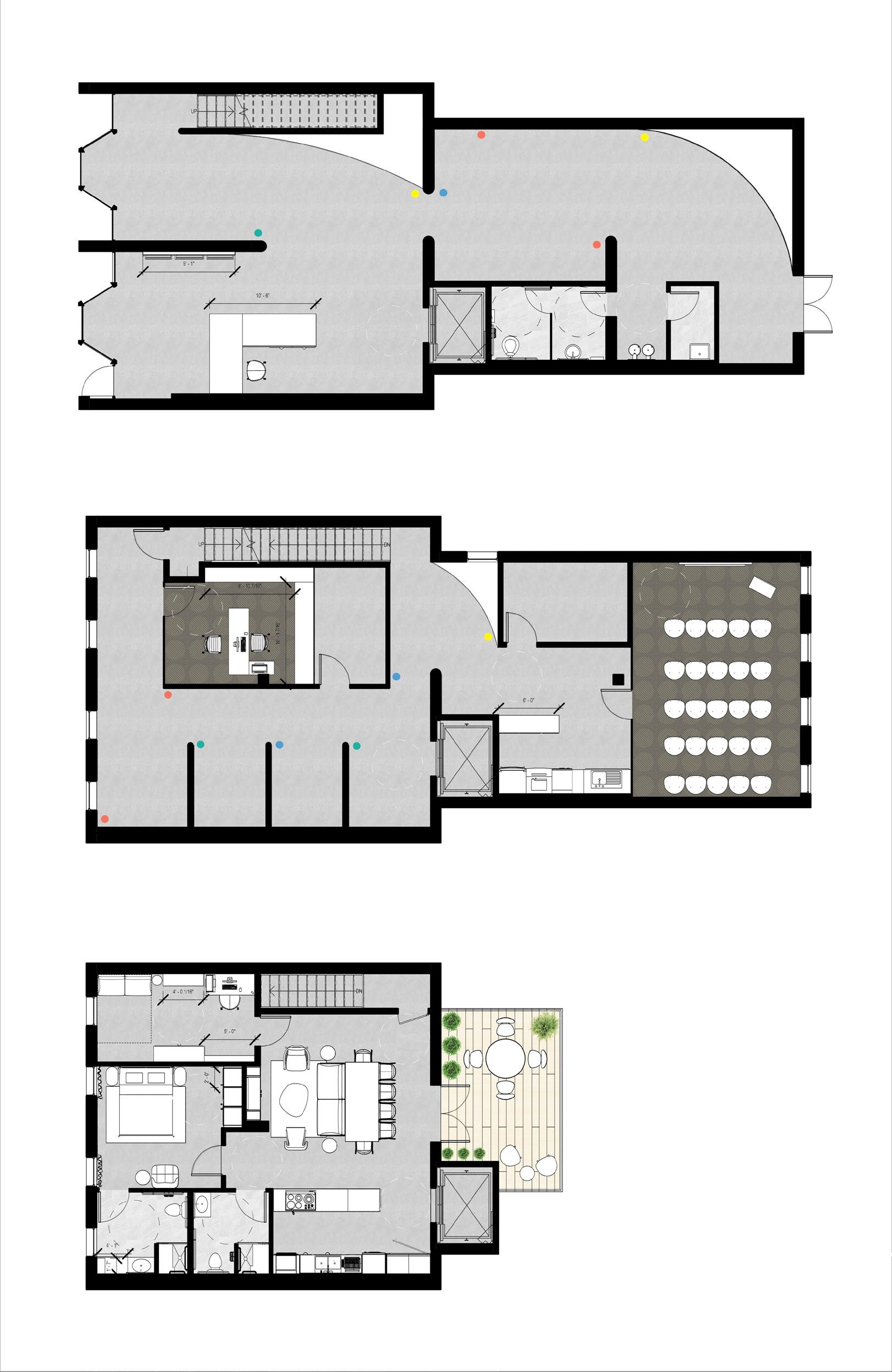

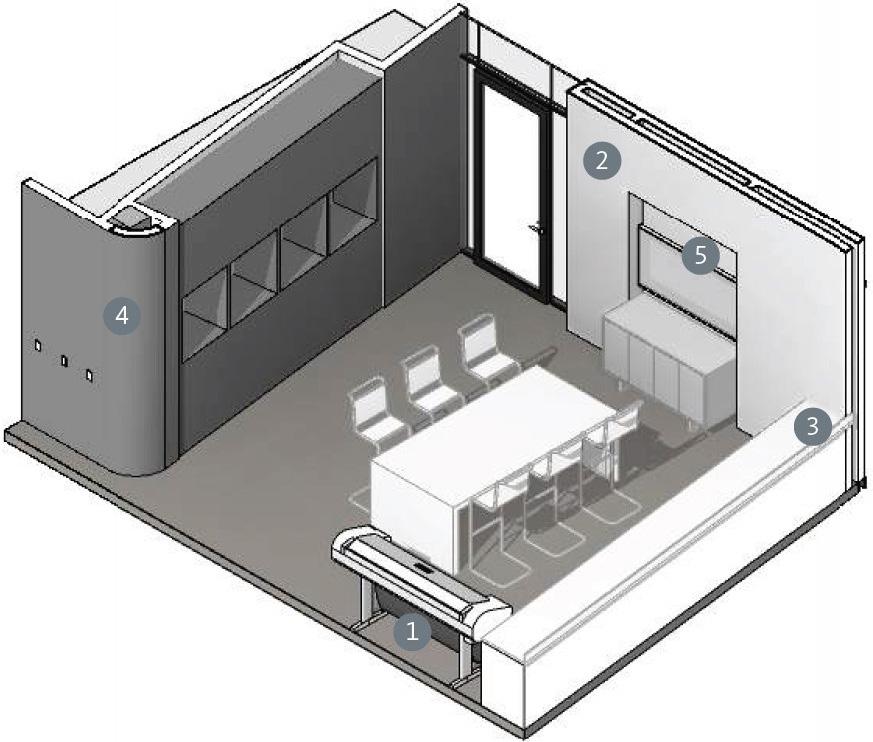

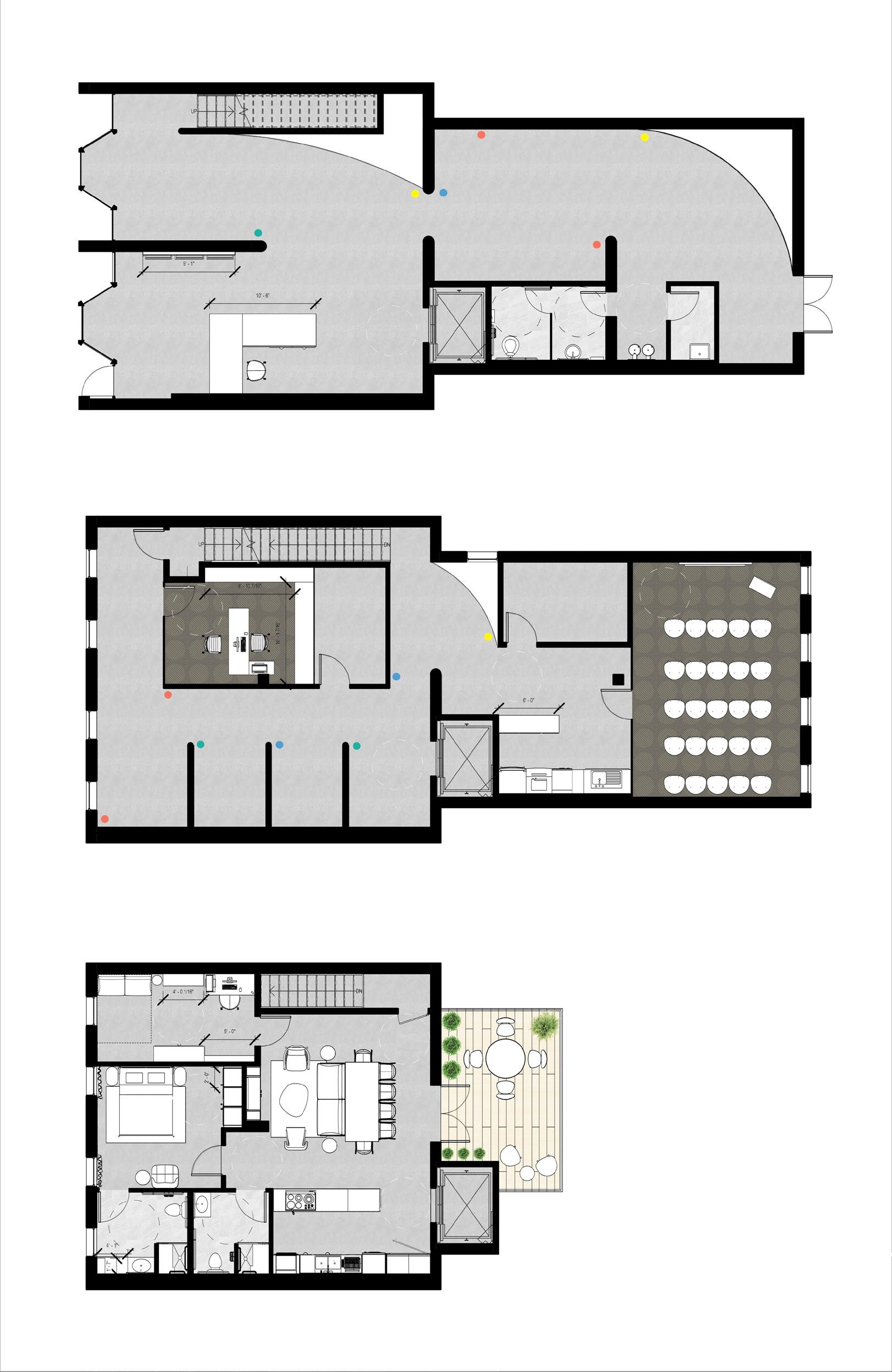

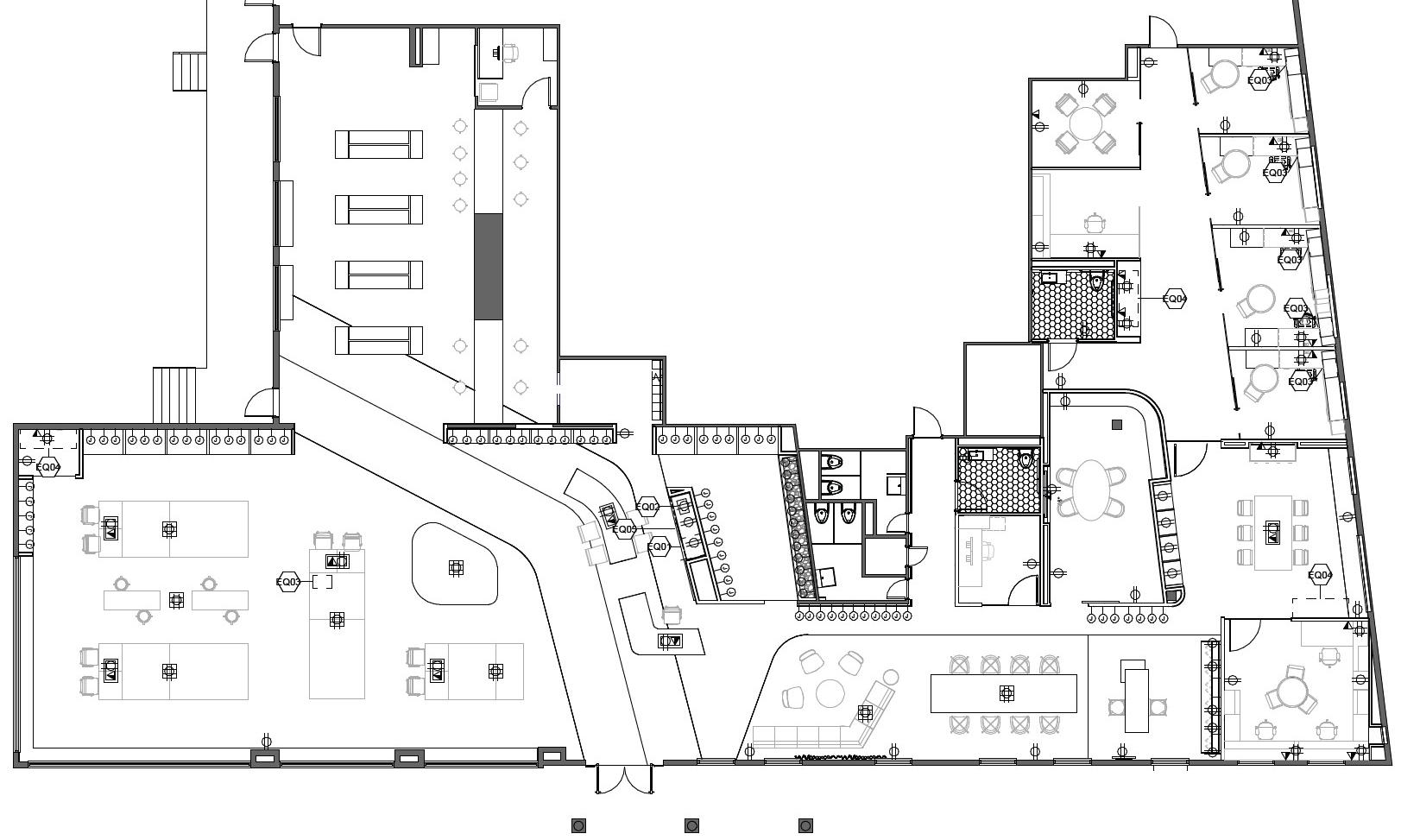

Family Home, Rumaithiya, Kuwait

This family home located in Rumaithiya, includes a basement, ground floor, first floor, and roof. Tasked by the clients to incorporate both Contemporary Classic and Country American styles as part of the interior direction, rooms were divided as either guest-centric or family-centric to be designed in the preferred style. The space planning was directed towards providing all the client’s required spaces while incorporating existing interior elements such as ceiling decors.This project sources all materials, finishes, fixtures, and

furniture locally. My scope of work included: full interior site survery, schematic design presentation, design development presentation, presentation of material boards, all custom cabinetry and furniture detail drawings, contacting corresponding vendors, working alongside project contractor, and providing a full interior construction document set.

*Renderings produced by FECRA visualization expert, Abdullah Bukamseen.

UP UP UP UP UP LIFT POOL AREA GUEST BATH OUTDOOR SEATING DINNING AREA 10 SEATER ISTIQBAL AREA UP LIFT DN DINNING AREA OPEN ROOM GUEST SINKS LIVING ROOM FOYER ISTIQBAL GUEST SINKS BATH ROOM MAIN ENTRANCE GUEST BEDROOM CLOSET ROOM MASTER CLOSET CLOSET ROOM CLOSET ROOM CLOSET ROOM BATHROOM BATHROOM BATH ROOM BATHROOM BATH ROOM BATH ROOM KITCHENETTE STORAGE ROOM UP DN LIFT MASTER BEDROOM BEDROOM #4 BALCONY LOUNGE BEDROOM #1 BEDROOM #2 BEDROOM #3 LIVING ROOM LIFT DN MAIDS BEDROOM IRONING ROOM LAUNDRY ROOF GARDEN Basement Level First Floor Roof Top Garden Ground Floor 62

Ground Floor Istiqbal Room

Ground Floor Istiqbal Room

First Floor Master Bedroom Suite 63

Ground Floor Dinning Room

In Representation We Trust

A Critical Assessment of Hyper-Realistic Landscape Representations

The landscape architecture field has explored a multitude of representation techniques and styles. But the techniques and styles used to convey landscape projects to the general public/to the targeted audience who will be experiencing the landscape, remains the typical hyper-realistic, polished and glamourous renderings. Both international and local firms choose to represent landscape projects in static states, previewing a landscape in pristine conditions, so realistic, it’s bound to fool its audience. This representation has bigger impacts than what meets the eye, quite literally. Picture perfect landscape representations miscommunicate the very nature of landscape projects. The very medium of the profession is living, growing, changing, and decaying. To choose to represent these proposed landscape projects, the same way architecture firms represent new buildings on the block is absurd. A landscape may never live up to meet that rendering, and if it does, it may do so for a short period of time, or not anytime in the near future. Merriam Webster defines false advertising as: the crime or tort of publishing, broadcasting, or otherwise publicly distributing an advertisement that contains an untrue, misleading, or deceptive representation or statement which was made knowingly or recklessly and with the intent to promote the sale of property, goods, or services to the public. These representations are therefore false advertising. So I put forth three key points in regards to landscape representation that should and need to be addressed by landscape architects: reject unrealistic, frozen-in-time, picture perfect landscape representation, embrace a landscape’s life cycles by choosing to represent its fluctuations through time, and lastly, accept that representation is meant to represent rather than duplicate.

To introduce my stance on landscape representation, I began looking through one of Diana Balmori’s texts, a book titled “Drawing and Reinventing Landscape”. Balmori was the founding principal of Balmori Associates Landscape and Urban Design founded in 1990, a design office based in New York that works on an international scale focusing on the interface of landscape and architecture (Balmori, About Page). As an urban historian and landscape architect, Balmori rejected the divide between architecture and landscape, calling for sustainable design and blurring the lines between landscape and built structure, and most notably was known for interpreting cities as living entities.

In her book, Balmori begins by taking the reader back to landscape architecture’s origin in the seventeenth century France and eighteenth century England when the notion of representing exterior space was first brought up. Throughout the chapters, she continues to explore the profession’s relationship to painting, cartography, plans, sections, perspectives, and even hand drawn sketches . In the final three chapters, Balmori looks at both historical and contemporary works of landscape representation and the struggles that rose with them. I should also mention the wealth of landscape visualization she shares in her book, both from her personal work and from other professionals that she uses to make her arguments. She comes to the conclusion that it is the innovative forms of representation that are experimental in technique that one can clearly see the emergence of the new: the new growth and decay, the new profession, and the new space.

Balmori begins her first chapter introducing the reader to the world of landscape representation, its evolution from landscape painting to its transformation after the introduction of ecology and our understanding of nature, and how ever since its representation has been somewhat problematic. The shift in landscape representation begins in the 19th century when a new understanding of nature emerged. Some turning points that resulted in this shift include when the term ecology was coined by German marine biologist Ernst Haeckel who also introduced the concept of ecosystems, or when Charles Darwin described the transformation of species over time. Before then, by the 17th century, nature was viewed as static and rational (Balmori, 2014, p. 019). With the turn of the 19th century and the change in the way nature was being understood, landscapes started to be seen as transformative and everchanging.

She then showcases how the discipline emerged from landscape painting, the first attempt at creating a unified picture of elements otherwise seen as separate entities: rivers, trees, roads, and forests which became known as the landscape (Balmori, 2014, p. 029). It was not until the mid 20th century in both Sweden and the United States that landscape began to play a different role than it had been

64

prior. Under the Social Democratic government in Sweden, landscape rendered the environment as public good, creating public parks in the city of Stockholm. In the case of the United States, landscape played a major role in the development of parkways after automobiles were introduced to the urban fabric (Balmori, 2014, p. 021). She argues that by the 20th century, landscape architecture started to adopt the concept of ecology and was sometimes mistaken for it.

She continues by sharing how her dissatisfaction with the static landscape representation she used at the time when rendering proposals for St. Louis and Memphis down the Mississippi.

“I became extremely dissatisfied with how such projects were represented. Rendering prepared for public activities and landscape furnishings set in the natural background, which communicates both a distance between people and nature and a sense of nature as a fixed entity. So, together with others in my office, I began to experiment with different ways of representing projects that instead embrace the reality that nature is constantly changing” (Balmori, 2014, p. 025).

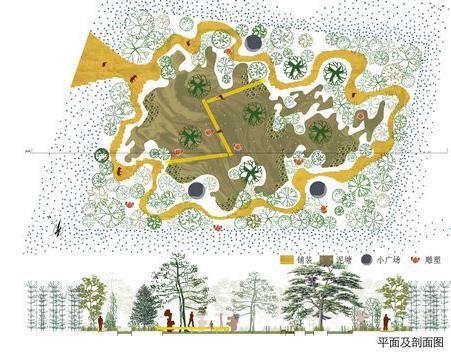

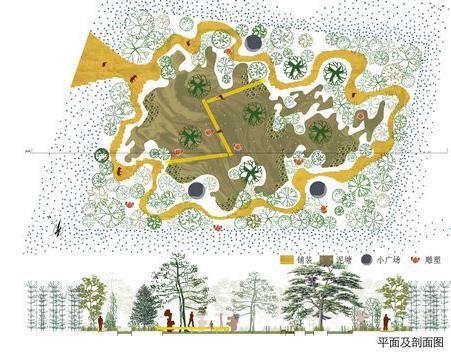

To this point, I reference representations produced by Stig L. Andersson’s (SLA) design office for their project Yellow Mud Garden, a public exhibition park that was part of the Xian International Horticultural Exposition in China that Balmori introduces in her text on page 103 (see figure 1).

Balmori speaks on behalf of Andersson’s genius and his ability to represent landscapes designed for touch more than for the eye. His representations for this project were a collage of traditional Chinese landscape drawings and photographs of real plants, playing with a range of colors, treating all the visuals as though they were paintings.

Though Balmori uses SLA’s representations to convey a connection back to landscape painting, I see the visuals as illustrative, experimental, expressive, and more importantly, being able to get the concept of the design across to the audience without having to produce a hyperrealistic perspective or plan. Looking at both the plan and section below, a viewer could differentiate between mud

pools, vegetation planted, and designated circulation. The representations are neither deceptive nor were an attempt to sell to an audience of an ‘unattainable’ landscape condition as we are starting to see in large scale landscape representations used to cover site construction walls today.

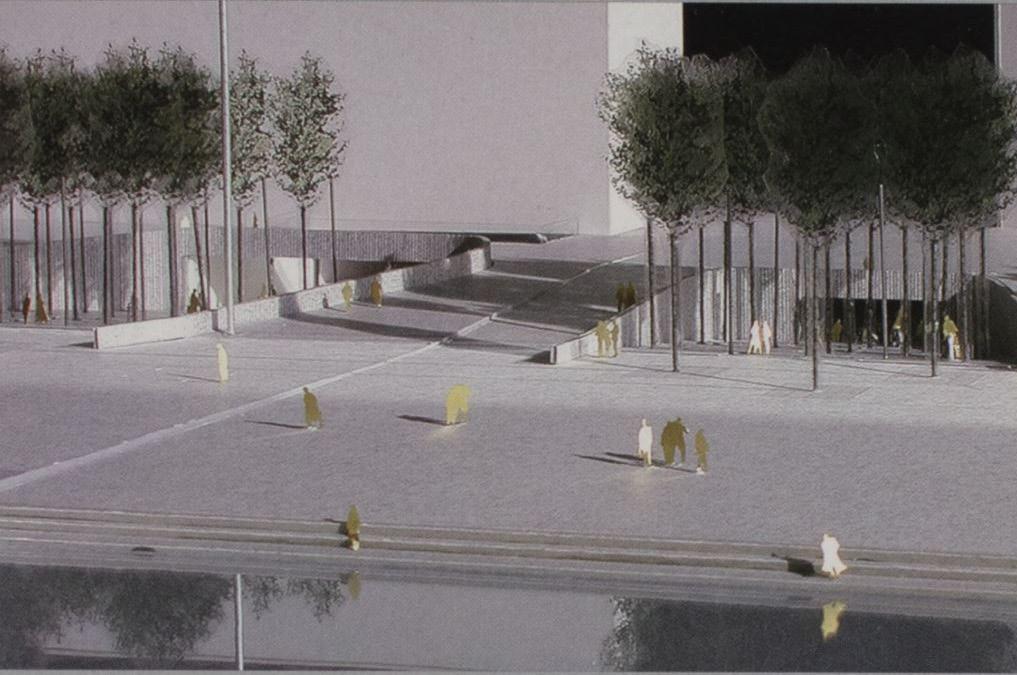

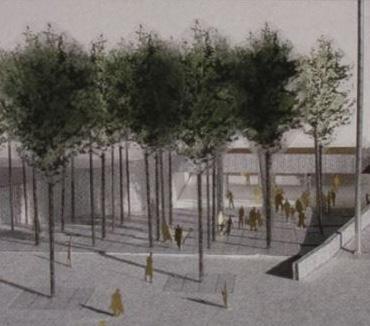

To counter this form of representation, I introduce more recent renderings produced for the Parco Romana 2021 competition won by a team composed of: CRACarlo Ratti Associati, OUTCOMIST, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, PLP Architecture, and Arup (see figure 2 and 3). This competition reimagines Parco Romana, an urban redevelopment project in Milan’s Porta Romana district. As a team, the proposal sought to seek reviving the site’s industrial history while livening it with contemporary programs centered around sustainability (Parco Romana, About Page). Putting aside the team’s proposal, what bothers me is the representations that ended up being shared with the general public. It was as though they were selling a dream, and the public could see it in hyper-realtime, meaning, it could very much be the reality once this park opens up. These renderings are very much attainable, but it is the fact that design offices are still choosing not to show alternatives to the public eye. How will this park look

Figure 1 Plan and section of Yellow Mud Garden, courtesy of SLA (https://www.sla.dk/en/projects/mudgarden/)

65

in winter when the leaves fall into the water or when it is raining in mid November and the wetland path is no longer accessible and the planting beds are flooded? How will the park look when the plants are still young and trees are still in trunk scaffolding once the park is open to the public? I believe the public deserves to see and know that this park will not be perfect 365 days a year, but instead will embrace all the seasons and fluxes, so people are aware that these changes are natural, expected, and should be embraced, not artificially controlled. These air-brushed final renderings are problematic to say the least. We must reject this pictureperfect, frozen-in-time style of representation. As Balmori clearly puts it:

“In the representation of landscape, one particular piece - the final rendering- plays a key role in the world of competitions through which most commissions are awarded today. This social document is an image of fixity, moreover, it is based on an ideal of permanence, intimating that landscape is eternal. The acceptance of change as a constant in nature has unravelled that implication, which is conveyed by the iconic rendering frozen in time; final renderings can no longer be viewed as images of an everlasting, paradisiacal landscape or Arcadia that speaks of an eternal equilibrium” (Balmori, 2014, p. 184).

In the fifth chapter, Balmori shares the five issues she believes landscape professionals need to tackle when it comes to landscape representation: continuing the importance of painting, representing representation, depicting larger spaces, using integrated drawings, and representing temporality and ever-changing landscapes using imperfect sequential panels (Balmori, 2014, p. 146).

In her final chapter, Balmori covers two important contemporary subjects in landscape representation that have been brought up by constant change. The first being that nature is in constant change, and the second being that human impact of nature is accelerating this constant change. In both situations, the profession needs to accept constant change and represent it. A new language of landscape representation awaits that involves computing and hybridizing different data from different fields in order to more accurately represent this change. She states, “The fixed Arcadian images that have dominated the representation of landscape up to now need to be left behind”(Balmori, 2014, p. 181).

Balmori concludes that landscape representation needs to strive for so much more than constructing an image of paradisiacal fixedness, it needs to strive for poetic images that capture change, that showcase proudly that these spaces can change and will change, but still bring joy (Balmori, 2014, p. 187).

Figure 2 and 3 Perspective views of Parca Romana courtesy of Carlo Ratti Associati. (https://carloratti.com/project/parcoromana/)

66

To add onto Balmorti’s critique of the fixed Arcadia landscape representation, which is still used today to convey landscape projects even well after this book was published in 2014, these beautiful hyper realistic landscape perspective shots do more than we think they do. What Balmori doesn’t cover or unpack, is that they feed back to the human population wanting things instantly, right here, right now. Paul Roberts’ social critique of our Impulse Society, in his book “The Impulse Society” tackles a world where instant gratification has become the norm, where fast rewards, short term fixes are chosen regardless of the long term detrimental social costs it leaves behind. These unattainable representations feed into the Impulse Society, as landscape architects feel the need to present these visuals to clients who do not want to see the messiness that comes with landscape projects. Clients want to see polished visuals, even though they are nothing near reality. Truth is, landscapes are not like interior or architecture projects, they are not projects that can be controlled to the very last screw or steel bar even though we think they do. To some extent, they are uncontrollable. We as landscape architects cannot guarantee that the Elm trees planted in the park will start to decay in a matter of months because they were infected by the Dutch elm disease spread by the elm bark beetles. We can predict, we can educate, we can speak up, and we should. I believe landscape architects are doing a disservice to the profession by selling landscape projects to clients by advertising hyper-realistic renderings that in fact, are far from real life. Realistically, all planting material cannot show up to the construction site full of foliage and already 15 years old. Although possible, it usually arrives premature, in a burlap covered root ball, ready to be planted and taken care of in order to grow to its expected mature height/spread over the years. This is perfectly normal. Instead I critique how this stage is concealed from the audience/the general public in representation. To quote Barbra Bender, ‘landscapes like time can never stand still” (p. S103). Show the general public/audience outside the field a park just planted with saplings. Show them a park with fall leaves left on the ground to decompose. Show them a landscape that is real, that is always in a state of flux. Show them that like us, landscapes are alive and their faultless representations are detrimental to their well being as overmaintenance has become the norm, and expectations of these spaces are exhausted. We as landscape architects must

embrace a landscape’s life cycles by choosing to represent its fluctuations through time.

Next, I will look at Michel Desvigne as a landscape architect noted for his landscape representation that embraced time, change and process. In the book Intermediate Natures: the Landscapes of Michel Desvigne, James Corner introduces Desvigne as a landscape architect that considered the discipline a living artform that centered around cultivation, process, and change over time rather than a focus on formal composition. Desvigne has a talent for being able to work at both large and small scale projects giving them both the detailed attention they deserve. After understanding his site, he then implements themes such as: site modification, improvement, planting, cultivation, and management over time (Gilles and Desvigne, 2009, p. 7). His agricultural emphasis allows for his landscapes to grow, change, adapt, and essentially become flexible spaces as he is less concerned with formal composition and instead techniques for caring/tending to the land. Desvignes approach to landscape is about representing process, seeking pragmatic land-based approaches to both design and representation, creating landscapes that immerse one in a sea of texture, in a space not clearly defined by geometric shapes nor hard boundaries, creating a more porous open matrix (p. 8). Desvigne is not afraid of unfinished work, he prefers it and is fascinated by it. These unfinished projects hold the excitement of what is to come next, as growth and change are anticipated and celebrated. He believes a landscape is never really finished, it is always in a state of change and flux, a work in progress, never attaining an ideal state (p. 9).

Desvigne then speaks on his own behalf how he sees and tackles landscape architecture. He notes that in his midpoint of his career he does not hold a set of seductive images, photogenic models or even computer generated drawings in his portfolio that circulate the disciple at the time. Instead he uses simple materials and methods to represent his work. He describes it as a sort of poverty, the lack of extravagance that also resulted from working with architects that would take over most of a project’s budget that in turn gave him the ability to design landscapes that can fluctuate, change, and embrace change. That same poverty is what pushed him to innovate, to reject a polished landscape and instead

67

embrace development, and a landscape’s youth. Most importantly, Desvige states, “Also, and above all, to refuse to show this work through stereotyped images” (Gilles and Desvigne, 2009, p. 11) The understanding and acceptance that landscapes are living organisms, both the vergation and the architecture and then directing and domesticating them, is what bring Desvigne joy. He speaks about intermediate nature and how he enjoys the long time frame of landscapes and cities, and being able to play with time through phases of vegetational development and its effects on spatial experience ( p. 12). “I think it is important to hold out against cliches, to play with the multitude, with the successions, There is no “beautiful” image, nor should there be, except by accident. Each of the images is taken in a larger series and a larger space”(Gilles and Desvigne, 2009, p. 13).

Throughout this book, Desvigne speaks on behalf of his landscape projects and the logic behind why he chose to tackle the project the way he did. Each project is accompanied by a rich selection of his representations that showcase his ethos in their production. Though this book is a series of detailed briefs and concepts that the landscape architect implemented, what interests me is Desvignes multitude of representations and the logics behind each one. After he shares with the reader how he views landscapes as active, always in process living entities, you start to read that definition in his visual works. I choose to separate the

visuals from the concept in this case as I try to see them through the lens of the general public, who are not aware of the project’s concept but are usually just fed visuals before a project is constructed in their block. To begin, I look at his project models for Almere, 2000-2005, the Netherlands and compare it to the site photos taken after completion, see figure 4-9 (p.134-135).

68

Figure 4-9 Images of models of Almere, the Netherlands, by Michel Desvigne and photographs of the site after completion (Gilles and Desvigne, 2009, 134-135)

He effortlessly captures and embodies the experience he is trying to achieve in the site models and photography. His use of transparency sheets with transferred color/pattern of foliage is able to mimic canopy densities, while showing a viewer how the space is organized. The second model uses a baby breath equivalent instead of the transparency to mimic how the trees will act in winter when the foliage has fallen. The images show a dappling effect on the ground almost perfectly mimicking a tree’s shadow in full winter sun. Comparing the model photos to the actual site is almost absurd, as they both successfully convey one another in form, structure, materiality, and placement.

Another set of representations I found that I think walk a fine line between representing process and capturing a paradisiacal static moment in time are the renderings produced for the Walker Arts Center in Minneapolis, USA, see figure 10-12 (pg. 170).

The images are almost dreamy in composition, achieved by altering the opacities of the trees in the foreground, middle ground, and background. People in the renderings are rendered to appear as though in motion, and the tree dappling shadows cast on the backs of the people in the final render is the winning shot. The sky is smoggy and filled in with a grey gradient with buildings almost disappearing in the distance. Everything besides the vegetation is muted out in saturation giving emphasis to the changing color of the trees. Instead of rendering these in summertime with foil foliage and bright greens, Desvigne chooses to represent time and process, choosing to represent fall, a transitional

Figure 10-12 Renders of Walker Arts Center in Minneapolis by Michel Desvigne. (Gilles and Desvigne, 2009, p. 170)

69

state in seasons where trees and atmosphere are in flux. If I were to compare these renderings to the hyper-realistic ones produced today, I would argue these carry more dimension, more character, and more expression. They show the viewer what to expect without overselling the landscape, this will allow the viewer to be more in awe once they experience the actual space after completion rather than compare the actual site to the realistic render shots, deeming the project more as a disappointment not being able to live up to rendered perfection.

To conclude, there is no one style that fits all. As shown through both professionals point of view, landscape is in process, it always will be and one of the biggest issues the profession is facing is how to represent something so dynamic and alive through traditional modes of representation. The modes of representation are almost endless, from computer modeling to coding, to sketching to collaging. I reject the hyper-realistic modes of representation as landscape architects can never represent nature in its full glory or predict how landscapes will look to a T. So why not use representation to do what it was meant to do, represent, not duplicate. Let the representations show character, motion, seasonality, activity, mood, and best of all, as Balmori recalls, bring joy.

References

Bender, Barbara. “Time and Landscape.” Current Anthropology, vol. 43, no. S4, 2002, pp. S103–S112. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/339561. Accessed 1 May 2021.

Balmori, Diana. Drawing and Reinventing Landscape. John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2014.

“Mudgarden - China.” SLA, 2010, www.sla.dk/en/projects/ mudgarden/.

Murray, Nick, and Diana Balmori. “The Landscape Architect on Living Cities, the Tyranny of Lawns, and How Mayors Will Soon Rule the World.” Breaking Down Walls, Guernica, 22 Apr. 2013, www.guernicamag.com/breaking-downwalls/.

“Parco Romana.” Carlo Ratti Associati, 2021, carloratti.com/ project/parco-romana/.

Roberts, Paul. The Impulse Society : America in the Age of Instant Gratification. First U.S. ed., Bloomsbury, 2014.

Tiberghien, Gilles A., and Michel Desvigne. Intermediate Natures : the Landscapes of Michel Desvigne. Birkhäuser, 2009.

70

71

72

From Cotton to Azbakiyya

A History of Westernization Through Cotton Wealth

*Note: The spelling of “Azbakiyya” will fluctuate throughout this paper as its name has been recorded with different spellings throughout its history and in multiple recorded documents. The most used will be Azbakiyya for the purposes of this paper.

Introduction

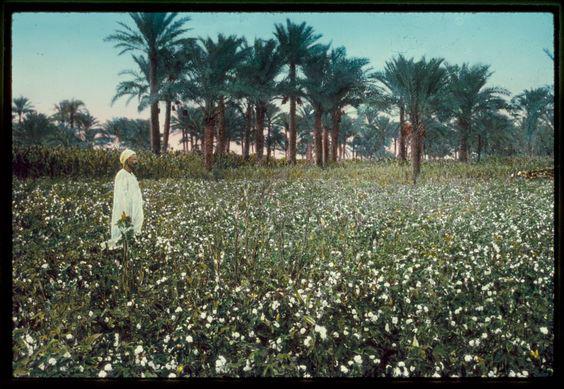

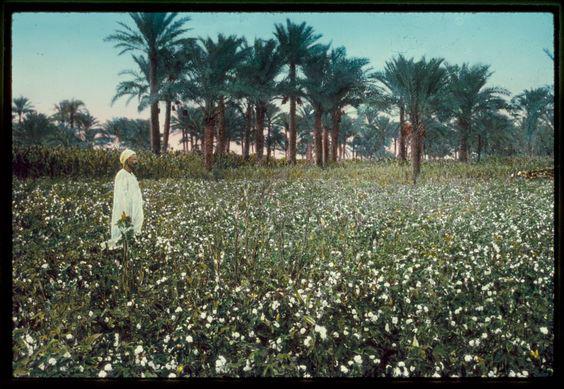

The growth of the Egyptian economy during the 19th century was the outcome of its increasing cultivation of long-staple cotton.1 This production is what lead to the outstanding government public works built throughout the 18th and 19th century. Its integral role can be seen through Egypt’s history in funding its growth, ginning it, and selling it to the Europeans where demands were high. Roger Owen notes, “that by 1909-14 it provided 93 per cent of Egypt’s export earnings.”2

Throughout this era, a notable ruler took the most advantage of the cotton industry’s boom in Egypt, Khedive Ismail. Upon Khedive Ismail’s accession to power in 1863, Egypt’s economy was thriving given cotton’s new demand created by the American Civil War.3 This mirage-like prosperity caused him to spend this new wealth abruptly, notably spending large sums on public works, a spending he continued even after the cotton market was in precarious condition during the second half of the 1860s.4 Though he attempted to redirect Egypt’s wealth source away from cotton by initiating

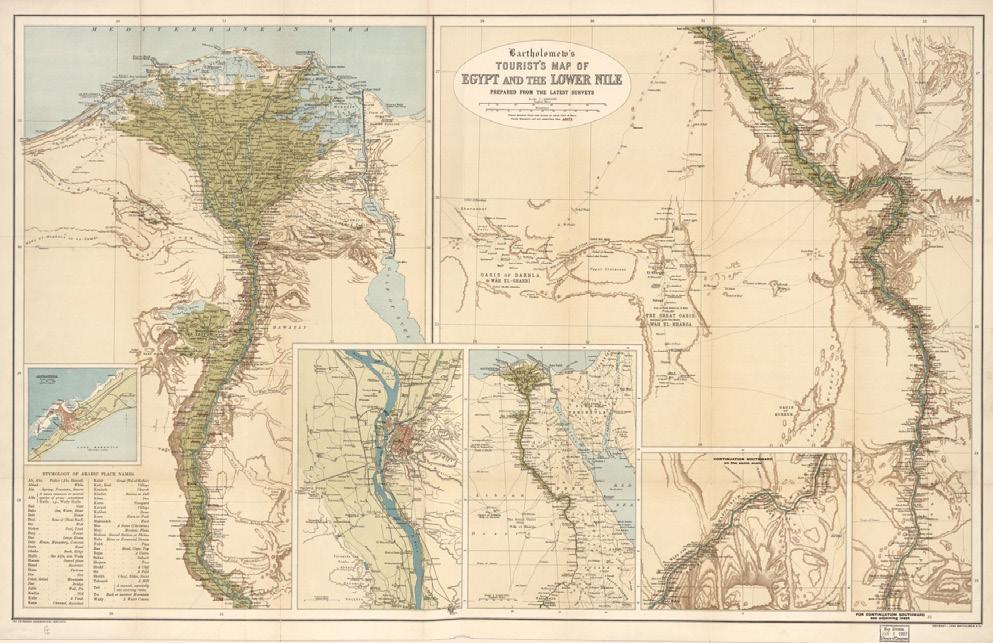

sugar refining industries, this scheme eventually failed as it was deemed unprofitable and collapsed.5 Cotton remained the cash crop of Egypt’s economy throughout both Ismail’s and his grandfather’s, Muhammad Ali’s reign.6 This paper will unravel the complexities behind the 1861-1866 cotton boom in Egypt, the introduction of long-staple cotton, its repercussions in the district of Azbakiyya, and its funding of extravagant public projects Khedive Ismail pushed forward, such as the redesign of his grandfather Muhammad Ali’s, Azbakiyya Garden.

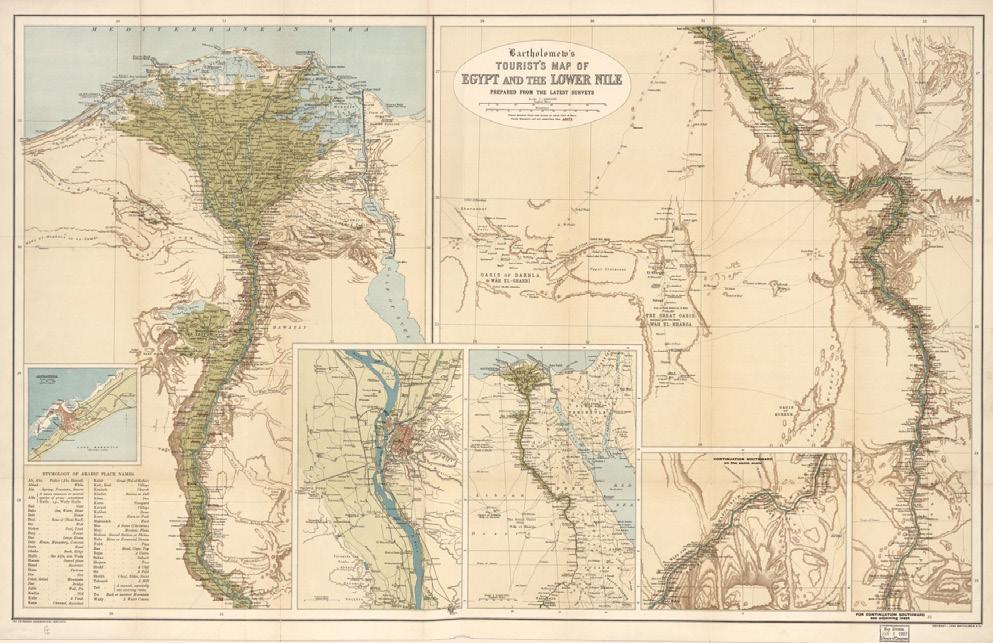

Figure 2.

Nile, 1897. (John Bartholomew & Co. Bartholomew’s tourists’ map of Egypt and the Lower Nile: prepared from the latest surveys. [Edinburgh: John Bartholomew & Co, 1897] Map. https://www.loc. gov/item/2009580103/.)

Material Economy

Cotton was never new to Egypt, given that ancient Egyptians knew of the crop as early as 2400 BC.7 But the story of longstaple cotton in Egypt begins with a French textile engineer, Louis Alexis Jumel, whom came to Egypt in 1817 as the new director of the in-development Bulaq spinning and weaving mill. During his first two years, he stumbled upon a different type of cotton growing on a bush in a garden in Cairo, that he identified superior in comparison to the other cottons being cultivated in the Middle East. Although this distinct type of cotton was not new to Egypt, it had historically only

Figure 1. Photo of a fellah in a cotton field, Egypt. (Photo by Matson Photo Service, created between 1950 and 1977. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.)

Bartholomew’s tourists’ map of Egypt and the Lower

73

been spun by a handful of women whom were unaware of its worth. By 1819, Jumel began to experiment with growing this long-staple cotton, first in his garden at Azbakiyya and then on an estate in Matariya.8 Fascinated by Jumel’s discovery and quickly identifying its worth, Muhammad Ali supported his research from the start, giving him time off from the factory, exempting him from land taxes where cotton was being grown, and even funding future research on the crop. Muhammad Ali saw an opportunity for monopoly of the product since not only was long-staple cotton inedible and not consumed locally, there was already a high demand for the article in the European market. In the European market, long-staple cotton was two and a half to four times the price of short-staple cotton, meaning cultivation of this staple would secure the revenue Egypt so desperately needed. After Jumel successfully harvested his 1821 crop harvest, Muhammad Ali radically expanded its cultivation. Lands easy to irrigate (usually along the eastern bank of the Damietta branch of the Nile) were now dedicated to cotton cultivation. Along with it, infrastructure was revitalized to support the new land needs, this included: the deepening and cleaning of existing canals, the erection of saqiyas (essentially a mechanical water-lifting device), and construction of dykes to control the yearly flood. In just a year, the decline in the quality of the crop harvest forced Muhammed Ali to import experts in the field from Syria and Asia Minor, to instruct the fellaheen (agricultural laborers) on how to properly cultivate the crop.9 With the imported expertise supervising every stage from selecting lands suitable for growth, to crop preparation for export, by 1823 the production of cotton increased tremendously and the quality was almost at the level of the superior American strain. The new long-staple cotton was now being referred to as, Jumel or Mako. 10 Under Muhammad Ali’s monopoly system, “cotton was far and away the most profitable of the crops”.11

It was not until the outbreak of the American Civil War that Egypt managed to reconstruct their economy to allow cotton to “become once and for all the crop which absorbed the major portion of Egyptian energies and produced an overwhelming share of its export earnings.”12 This cotton boom was fueled by the European textile industry’s enormous dependance on the American cotton supplies, therefore skyrocketing the price of cotton in the

international market once this dependence vanished.13

It is within the same time frame of the American Civil War that Khedive Ismail had been accessed to power, in 1863. Though Egypt flourished within the boom period under Ismail’s rule thanks to the cotton boom, it was after the boom that Ismail began to find different pools of income. “Isma’il was investing in agriculture [while] he was also multiplying the demands made on it. According to the few budgets published during his reign, the land-tax continued to supply over half of total revenue and alternative sources proved difficult to find.”14

“Increases in the land-tax began as soon as the boom was over, and by 1868 the British Consul in Alexandria was reporting that the fellaheen then paid, directly and indirectly, 70 per cent more than they had done in 1865.”15 Ismail continued to generate a source of wealth through not only exports, but also the land the exports were being grown on.

Although the Khedive’s reign was remembered as wasteful in his borrowed expenditures and overly ambitious developments historically, they left an everlasting mark on Egypt’s economy today, they strengthened the country’s export sector. The export sector consisted “of the area of the Delta where cotton was grown, and the two great towns, Alexandria and Cairo, which provided a European

style

74

Figure 3. Photo of fellaheen preparing land for cotton harvesting. (Pearse, Arno S. Cotton Growing in Egypt. Western Books, The Middle East from the Rise of Islam; Fiches 8,647-8,648. Manchester]: [Taylor, Garnett, Evans], 1912.)

of life for the landowners, foreign merchants, ginners, and others who made their profits from its activity.”16

The Site

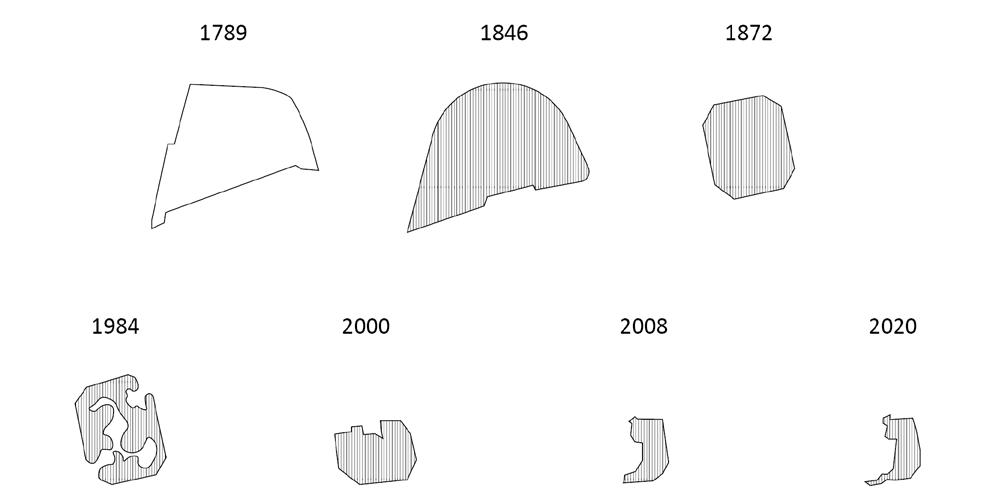

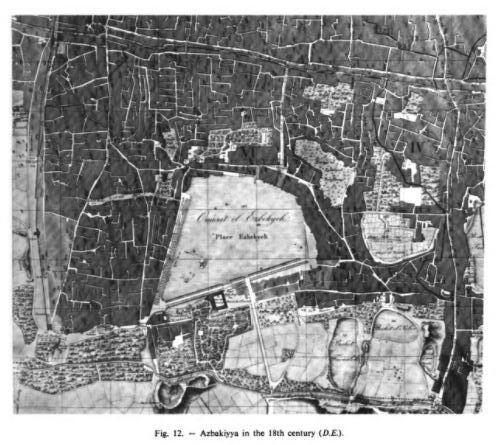

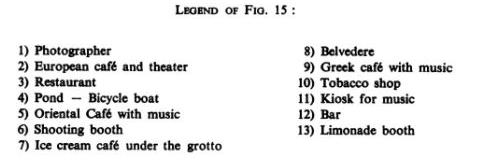

It is important to note that Azbakeya dates back to before the 15th century, named after Al Mue’z Al Atabiki Azbak, whom in 1459 began to construct halls and houses in the area. Post development, in 1475 Azbak ordered the excavation of Berkat El Azbakeya, that was being fed from Al-Nasir’s western Canal. These beautifications initiated the elite beginning to build their palaces in the area starting 1480, which gave Azbak more incentive to provide additional amenities to this new elite district. Of these amenities were the construction of a new great mosque, baths, and bakeries. Doomed after Azbak’s death, Al Azbakia went through multiple stages of deterioration, that continued even after the French Expedition of 1798-1801. But in 1805, after the departure of the French Expedition, it was Al Azbakia square that Egyptians gathered in to show their support for Muhammad Ali, an Albanian soldier, to become the new ruler of Egypt. By 1811, Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas’ud ibn Agha became the sole ruler of Egypt. For this very reason, Muhammad Ali made Al-Azbakiyya the center of authority, building a wall around the district that would control flooding, while also constructing a canal around the wall to provide the Azbakiyya Lake water supply during dry months.17 Al-Azbakiyya continued to evolve as

a central point of economic spending as will be discussed more in depth under the reign of both Muhammed Ali and his grandson, Khedive Ismail.

The Project

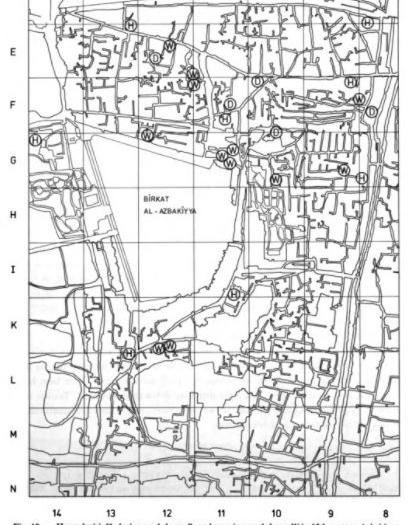

Egypt’s cash crop, cotton, funded new public projects under both Muhammad Ali’s rule and his grandson, Khedive Ismail’s reign. Specifically, cotton’s wealth funded the development of the Azbakkiya Garden in 1837 and its Parisian redesign in 1872. In an effort to westernize Egypt in 1837, Muhammed Ali sought to transform Azbakiyya Square into a large public park, offering Cairo’s public and the Europeans a promenade in addition to the existing avenue of Subra.18 At the time Azbakiyya Square was filled with ponds swarmed with disease-spreading insects, so Ali’s major concern was the site’s hygiene. After confiscating and compensating for 40 faddans (equal to 16.8 hectares) of land from the Bakris, Murton Bey was commissioned by the Ministry of Public Works to transform Azbakiyya to follow a European model when designing the garden. The project was completed in four years. The new plan was comprised of three paths lined with tropical trees (that both Muhammed Ali and his son Ibrahim Pasha imported) that intersected at a central decorative water fountain. The park was irrigated by a new canal built a few years earlier to replace the Nasiri Canal.

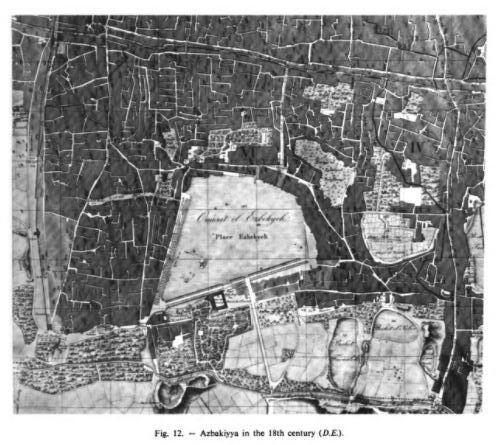

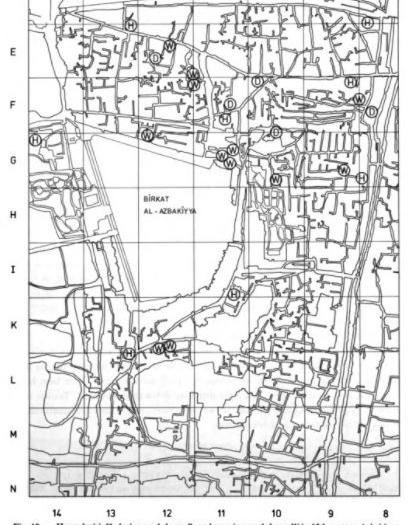

Figure 5. Map of Azbakiyya district in the 18th century. (BehrensAbouseif, Doris. Azbakiyya and Its Environs : From Azbak to Ismā’īl, 1476-1879. Supplément Aux Annales Islamologiques ; Cahier No 6. Le Caire: Institut Français D’archéologie Orientale, 1985.)

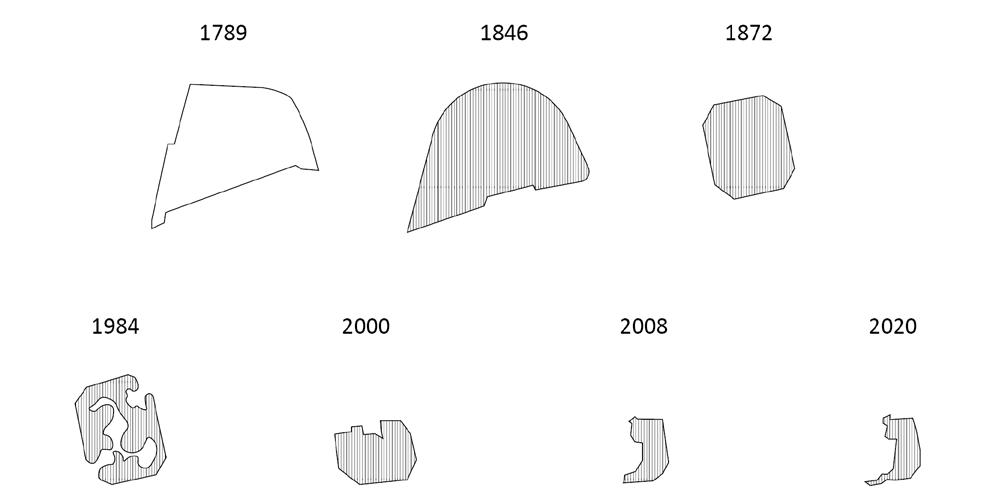

Figure 4. Diagram illustrating the many shapes Azbakiyya Garden has undergone, from its lifetime as a lake in 1789, to what is still left of its vegetated body today in 2020. (Created by Reem Bukhamseen)

75

Azbakiyya gardens. (Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Azbakiyya and Its Environs : From Azbak to Ismā’īl, 1476-1879. Supplément Aux Annales Islamologiques ; Cahier No 6. Le Caire: Institut Français D’archéologie Orientale, 1985.)

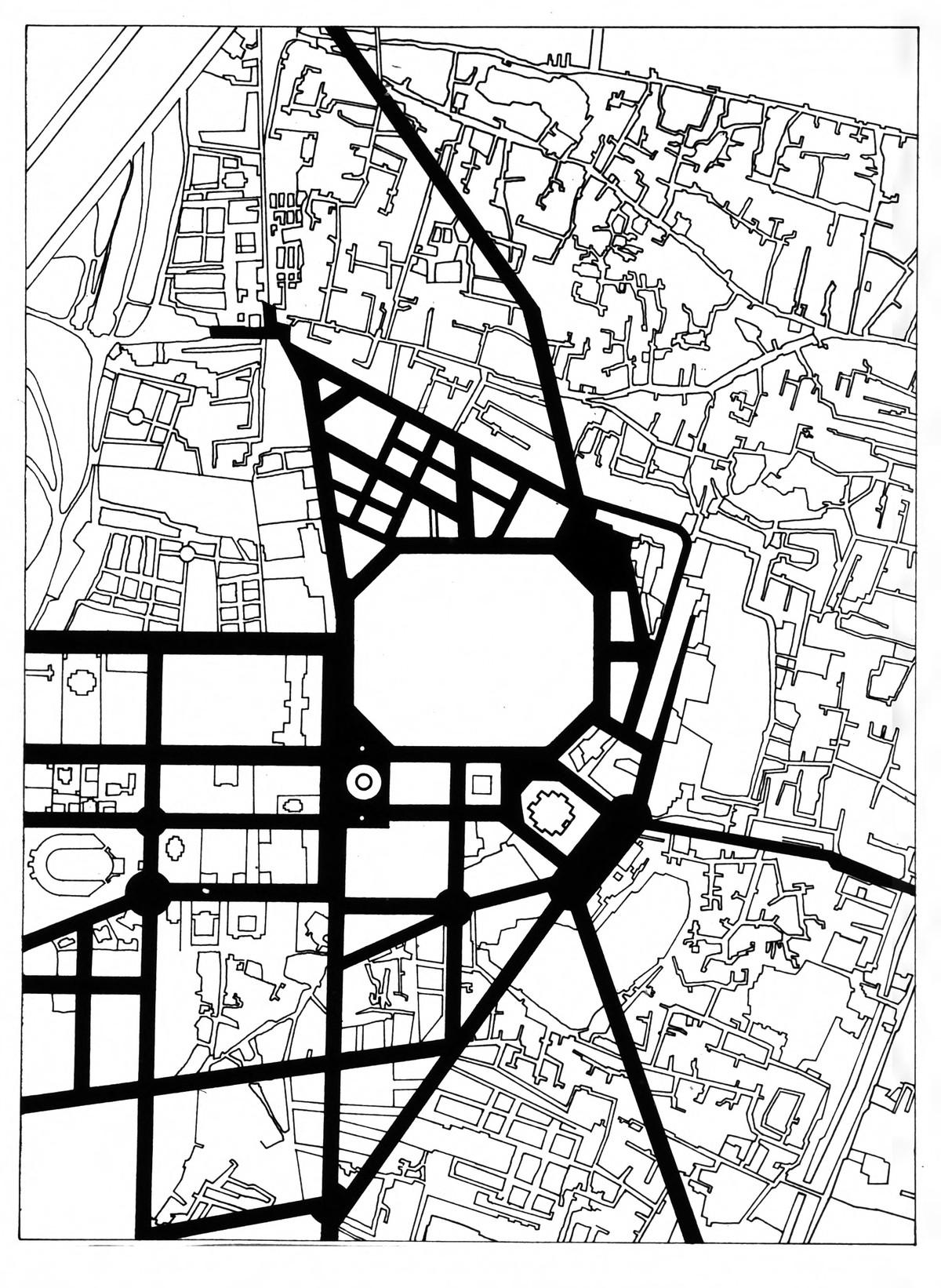

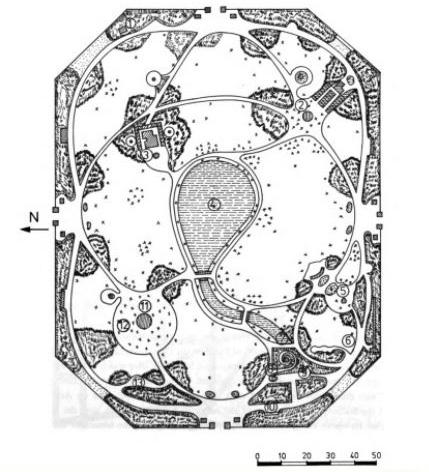

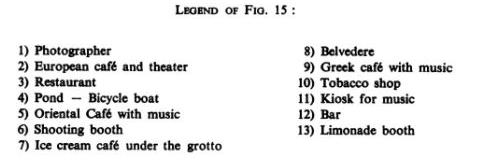

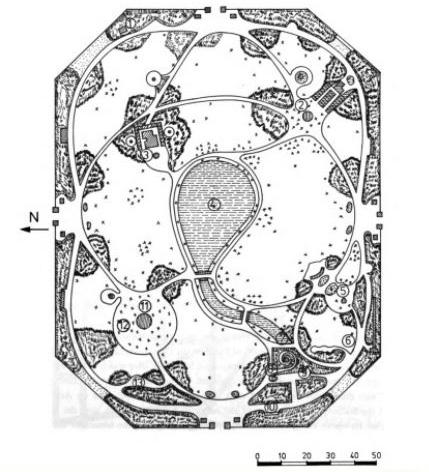

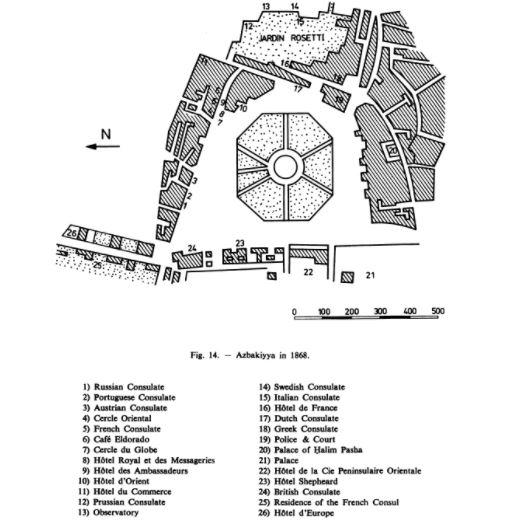

The park’s fluctuation continued under the rule of Khedive Ismail, Muhammad Ali’s grandson, who ruled from 1863-79. Under Ismail’s rule in 1867, he commissioned French architect, Barillet Deschamps, along with German botanist Schweinfurth to redesign Azbakiyya Garden in accordance to the French style. The Park was intended to reference Park Monceau in Paris, hence its octagonal shape. Ismail’s replanning of Azbakiyya garden was part of a much bigger scheme in which he intended to create a modern westernized quarter for the foreign community in Egypt. Under his rule, Azbakiyya Garden was reduced from forty feddans (16.8 hectares) to 10 feddans (4.2 hectares), this reduction allowed for more land to be allocated to new residences only foreigners or the elite of Egypt could afford.19

Environs

Azbak

Ismāīl,

Supplément Aux Annales Islamologiques ; Cahier No 6. Le Caire: Institut Français D’archéologie Orientale, 1985.)

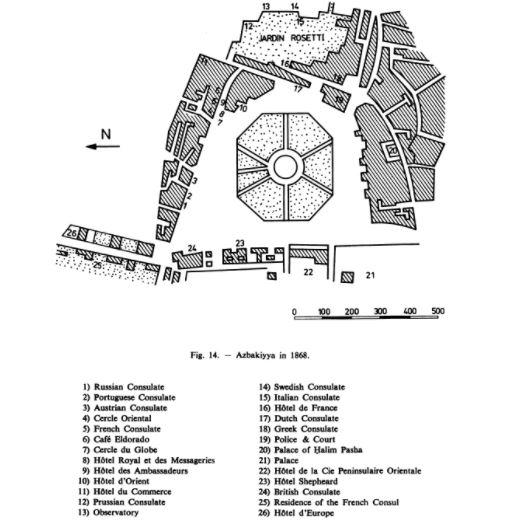

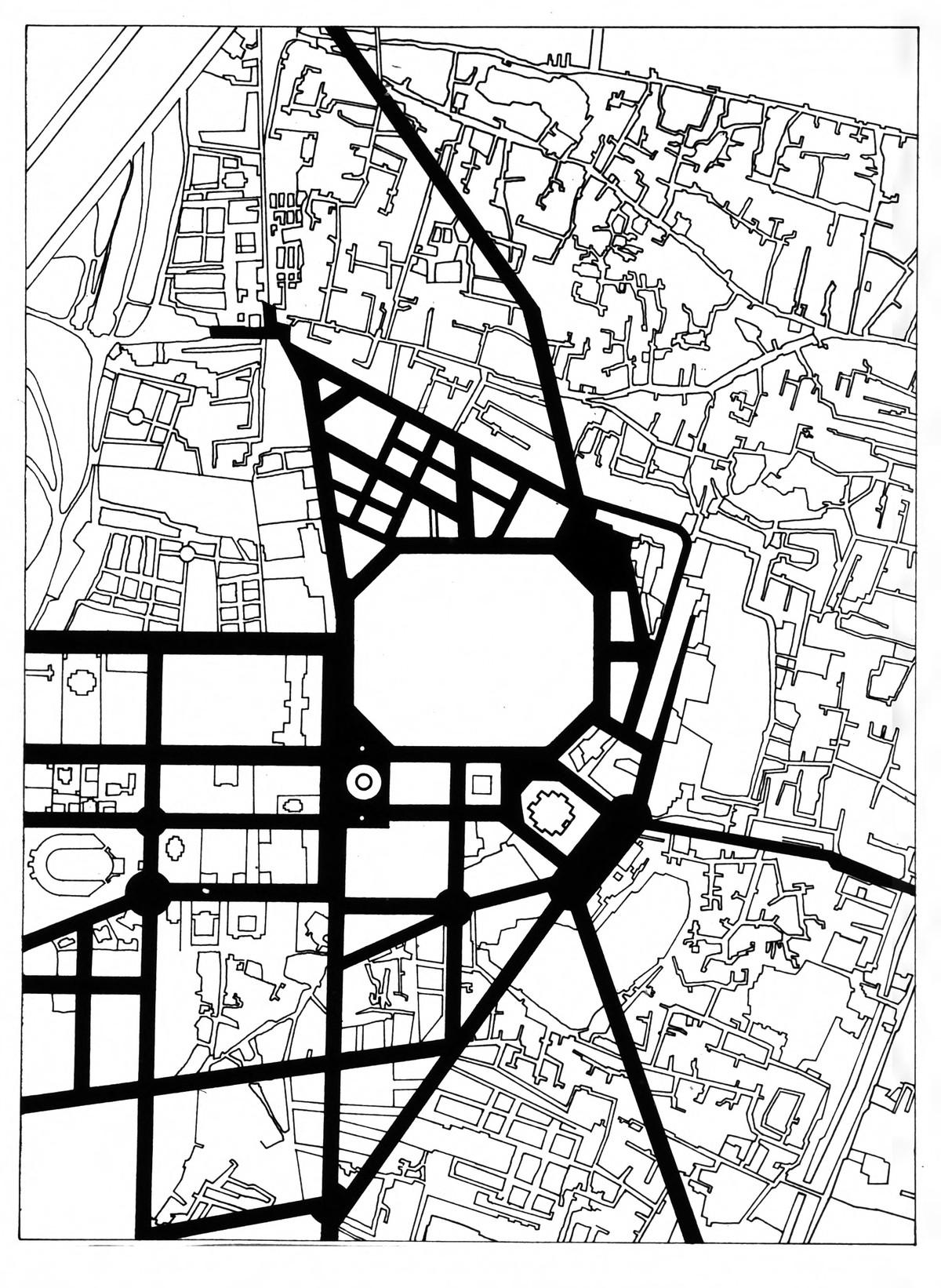

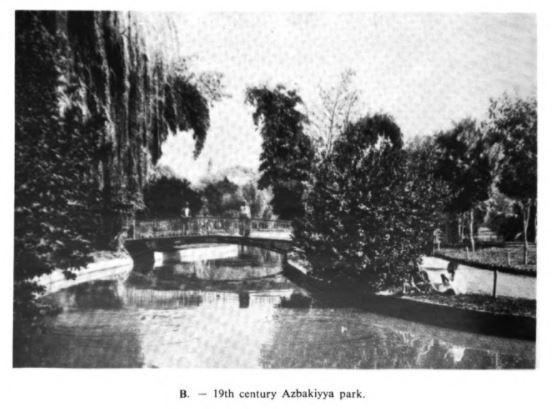

Ismail’s vision was to make Azbakiyya the new hub of Cairo, “the point from which the broad new streets radiated.”20 Existing structures and buildings were all demolished to make way for the new Europeanized quarter Ismail had envisioned. Azbakiyya was now home to new shops and cafes, along with a new comedy theater and Opera House. After the Azbakiyya park was opened in 1872, the park was equipped with a photographer, theater, both European, Greek and Oriental cafes, restaurants, bicycle boats in the pond, a shooting booth, ice-cream café, a bar, a belvedere, a kiosk for music, lemonade booth, and even a tobacco shop.21 Azbakiyya Park had a grotto where waterfalls would pour into a small pond, expansive lawns with pathways planted with flowers, belvederes that gave visitors a panoramic view of Cairo, a marble fountain, and an enclosed iron grille system that created 4 park entrances attended by Nubian doormen.22

Figure 6. Plan of Azbakiyya in the 18th century, illustrating location of Hammams (H), dyeing workshops (D), and weaving workshops (W) in relation to the soon-to-be

76

Figure 7. Plan of Azbakiyya park in 1846, designed by Murton Bey funder Muhammad Ali’s reign. (Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Azbakiyya and Its

: From

to

1476-1879.

Cahier No 6. Le Caire: Institut Français D’archéologie Orientale, 1985.)

Figure 8. Aerial imagery showing the history of continuous reduction of Azbakiyya Gardens square footage in the 21st century, even after Khedive Ismail’s initial reduction of the garden. (Created by Reem Bukhamseen, using Google Earth Pro Imagery)

Figure 9. Plan of the street network established during the reign of Khedive Ismail, radiating from the Azbakiyya gardens. (Azbak Min Tutukh, Azbak Min Tutukh. Azbakiyya, Cairo, Al-Qahirah, Egypt, 1476.)

77

Figure 10. Plan of the new Azbayikka Gardens designed by Barillet Deschamps, with new concessions, under Khedive Ismail. (Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Azbakiyya and Its Environs : From Azbak to Ismā’īl, 1476-1879. Supplément Aux Annales Islamologiques ;

Conclusion

“During the age of Ismail, intellectual, cultural, and scientific societies flourished.”23 Through his determined path of westernizing Egypt, Ismail dragged with him massive dept.24 For not only was long-staple cotton funding these public projects, but so too were the land taxes collected from the fellaheen whom grew the cotton, and European loans Ismail inevitably could not return from those he sold the cotton to. Cotton was always at the center of these complex interchanges. It was these lavish public developments, such as the Azbakiyya Garden redesign, in addition to his absurd personal expenditures that drove Egypt into a deep sea of depts and loans, that ultimately led to Anglo-French financial control, Ismail’s downfall, and British occupation of Egypt.25 The Azbakiyya Garden still stands today as a symbol of westernization the rulers under Muhammad Ali’s regime kept trying to weave into Egypt’s urban fabric.

Figure 11. Plan of buildings around the Azbakiyya in 1868. (Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Azbakiyya and Its Environs : From Azbak to Ismā’īl, 1476-1879. Supplément Aux Annales Islamologiques ; Cahier No 6. Le Caire: Institut Français D’archéologie Orientale, 1985.)

Figure 12. View of Azbakiyya Park with the music kiosk in the foreground. (Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Azbakiyya and Its Environs : From Azbak to Ismā’īl, 1476-1879. Supplément Aux Annales Islamologiques ; Cahier No 6. Le Caire: Institut Français D’archéologie Orientale, 1985.)