DEAN BLANDINO ON REPLAY

OUR TEACHER SHORTAGE

DEAN BLANDINO ON REPLAY

PRESSURE POINTS

LISTENING TO COACHES P.56 BOUNCE BACK YOU ARE THERE

Meet The Sergeant. This roll-top carry is your do-all, go-anywhere duffel. Its water repellent fabric makes The Sergeant a perfect choice for going to and from the dual meet, workout, or even a weekend getaway!

WATERPROOF SEALED ZIPPERS

INTERIOR SHOE COMPARTMENT

LARGE ROLL TOP OPENING HEAVY DUTY STRAPS

LARGE ROLL TOP OPENING HEAVY DUTY STRAPS

24 WHERE HAVE ALL THE TEACHERS GONE?

Once a mainstay of the officiating ranks, educators have become scarcer.

36 Q&A: DEAN BLANDINO

Fox Sports analyst discusses the current philosophies, rules and concepts governing instant replay in college football.

56 WORK THROUGH THE NOISE

Officiating veterans discuss techniques for improving our work in the pressure cooker.

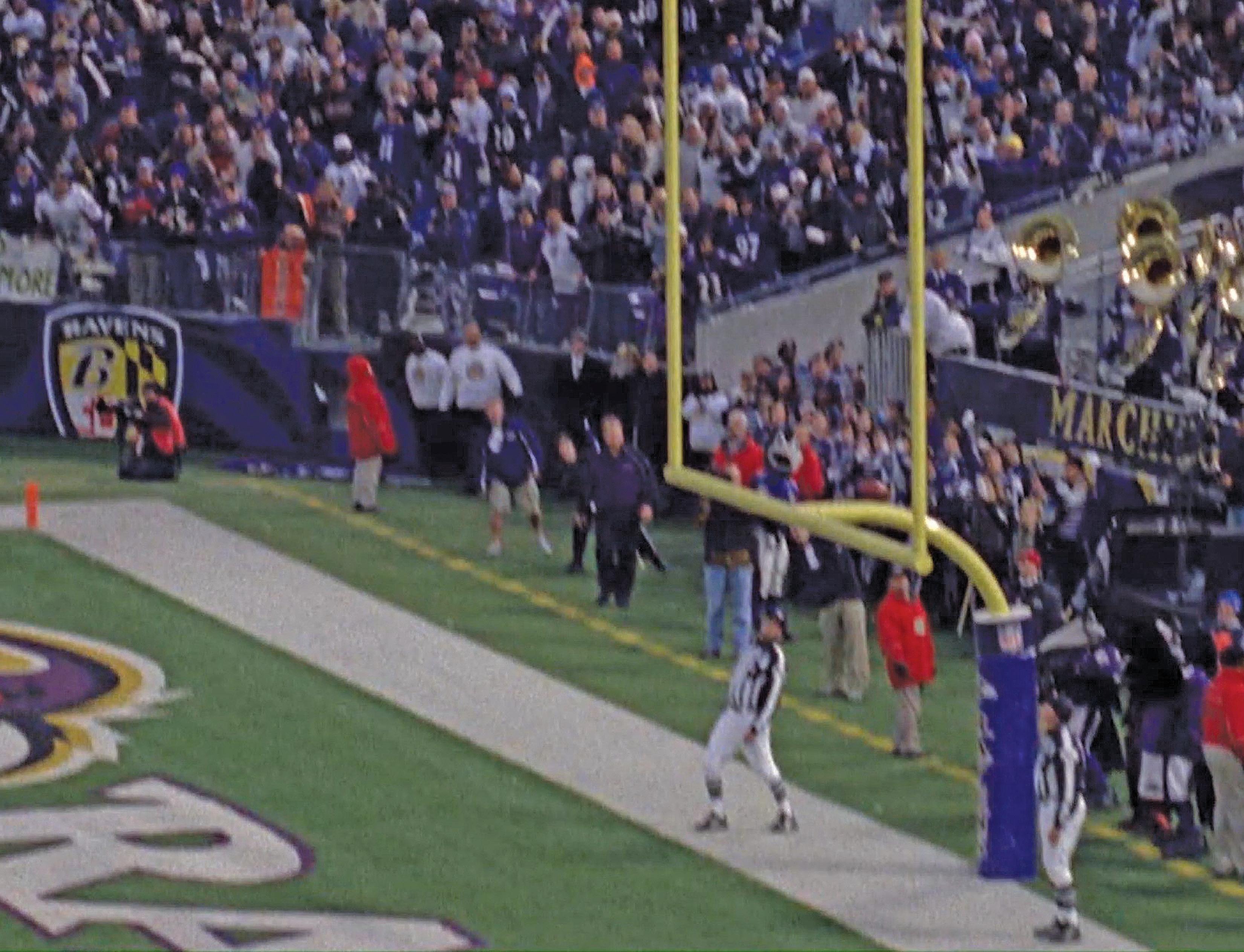

76 YOU ARE THERE: BOUNCE BACK

NFL crew correctly sorts out one-in-a-million field goal.

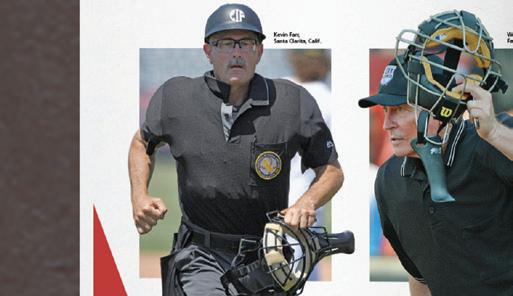

Age: 54

Occupation: Coordinator, Quality Compliance/Quality Assurance for major dietary supplement company

Officiating experience: High school basketball official for 16 years. Officiated two CIF Southern Section finals, six L.A. City Section finals, three regional finals and two state championships.

SPORTS

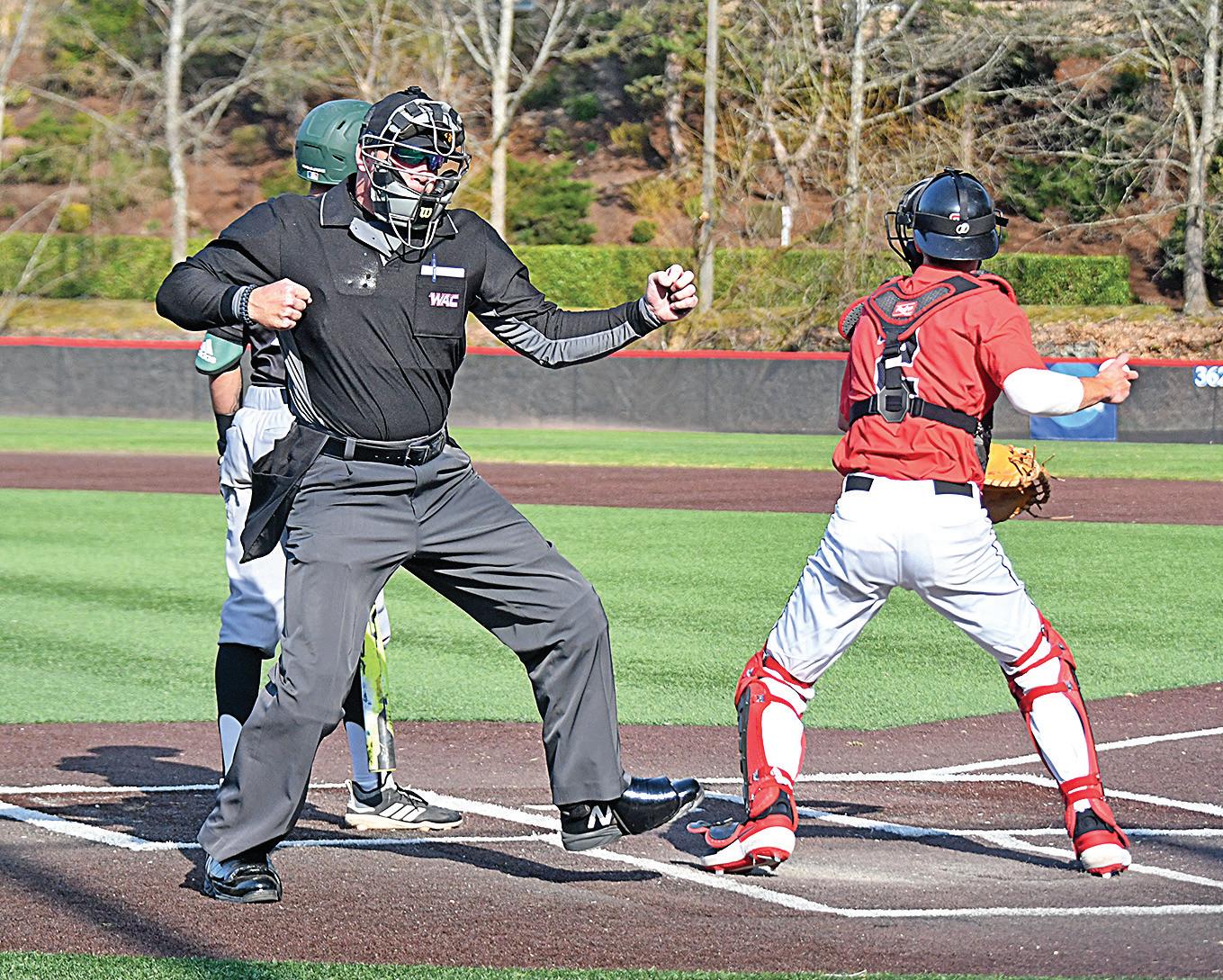

16 BASEBALL Stop It Right Now? Not Every Infraction Leads to an Immediate Dead Ball; Little Things, Big Consequences; Sell It as a Safe; Infield In ... And So Are U Too

40 BASKETBALL

Offensive Offenses: Don’t Let Ballhandlers Skate on Illegal Contact; Teammates Fightning ... Now What?; Develop Report Rapport

42 SOCCER

Lone Ranger: NFHS Rules Accord Special Attention to the Goalkeeper; Up for Grabs; When Good Is Not Good Enough

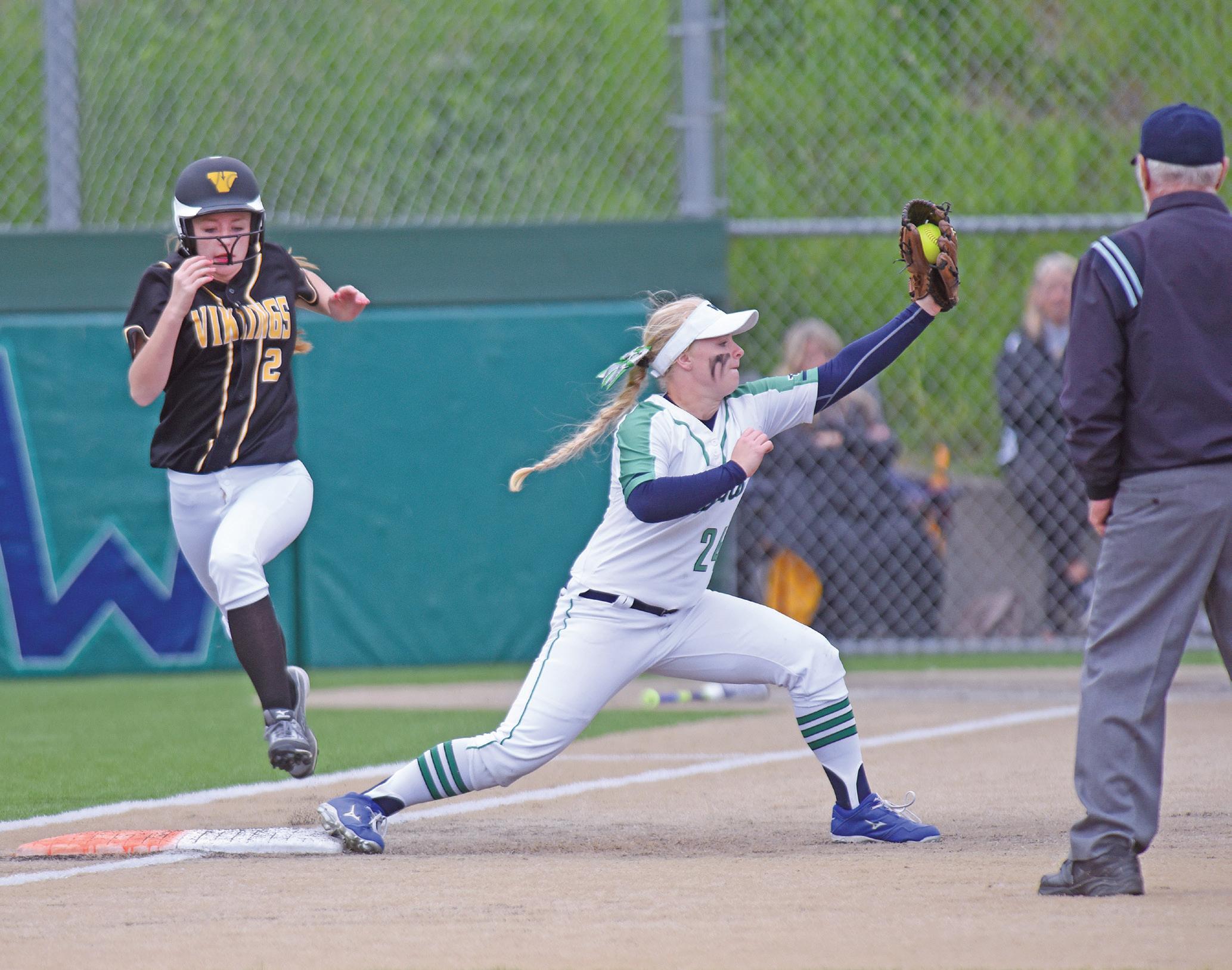

48 SOFTBALL

Two for One: Know How to Enforce Double Base Rules; USA Softball Tweaks Rules; Triple Duty; Wedge Work 60 FOOTBALL

Try Angle: When the Correct Position Isn’t the Best Position; Hold on There! We Ain’t Quite Done Just Yet; Pre-Snap Routine Is Habit Forming

68 VOLLEYBALL Know When to Hold ’Em: How to Properly Assess Sanction Cards; Out of Play?; Keep Your Eye on the Ball

78 ALL SPORTS

Lend Them Your Ears: The Art of Listening to Coaches; Tricks to Avoid Getting Sick; Feel the Joy of Officiating

4 PUBLISHER’S MEMO Taking Better Care of Us

10 THE GAG RULE

Letters: Technology Run Amok, Five More?; Give Us a Break; Say What?

12 THE NEWS

Pro Football Hall of Fame

Referee McNally Dies at 97; MLB Sees Wave of Umpire Retirements

40 GETTING IT RIGHT

Prong’s Passion; Brown’s Jersey Retired; For Love of the Game

74 PROFILES

Officiating Pair Cops Postseason Honor; Putting the Scholar in Scholar-

Athlete; Early Start Led to a Long Career

82 FOR THE RECORD 2023 FIFA World Cup final officials

84 LAW

Officiating the Game — and the Bleachers, Redux; Unruly Spectators Dealt With by Rule

85 CLASSIFIEDS Camps/Clinics/Schools; Equipment/Apparel;

Leadership Resources

86 LAST CALL

One-Game Umpire: One day, no umpire showed up. ... “How hard could this be?” I thought. “I referee soccer games.”

FOR MORE, GO TO

Watch the video at referee.com/pubmemo

Six years ago in this very space, I wrote a column giving a thumbnail rendering of our officiating environment. I had a tough time with that Memo. As I have now reread it, I felt a need to bring it forward this month. As it turns out, regrettably, very little editing was necessary.

As I rock back in my chair and ponder the past 47 years, it seems to me that on net, our working environment isn’t better than it was, and it would not be unreasonable to make the case it is worse. These words are still painful to write. In my role, certainly the expectation would be that I, more than most others, would be offering positive words here.

Yes, I have witnessed several positive changes in officiating. But I have also been forcibly immersed into the troubling waters of officiating today: the incessant questioning of our competency; the lack of incidentrelated visible support from governing authorities and assigning agencies; the personal attacks and physical violence, including death threats, by fanatics that reach far beyond the athletic milieu; the emphasis to turn sports into spectacle, with the attendant impact on us; the deification of technology; and finally, the crushing shortage of sports officials that has yet to abate.

I ask myself: What can I say to give us a vision to hope for, a strategy to strive for and a tactical plan to work at? Allow me the following.

First, I think we need to agree we will be unable to change the expectations of those who use our services. We need to accept what they expect. It ain’t fair, it ain’t especially reasonable and it ain’t going to change. Let’s get over it. With this as the down payment, we then need to invest in ourselves to manage those expectations and the inevitability of their scurrilous and patently unfair impacts. What should be the form of that investment? How do we take better care of us?

Let’s start with a six-word memoir from Jerry Markbreit: “All my best

friends are officials.” Yeah, we make close and long-lasting friends as officials. We count on each other during a contest, and often we come to rely on each other well beyond that field of battle. We build a sense of community. We have a sense of pride not really understood by non-practitioners. There is the huge online community of sites, message boards and posts for us to visit, to recharge our batteries and get uplift. It has never been easier to connect with each other.

Another way of taking care of us is to “circle of the wagons” when fate intrudes. This magazine publishes so many of those stories — of officials getting support from other officials during a tough time, be it officiatingrelated or just personal. And how about we make extra effort to support the local associations that mean so much to our industry?

Our investment portfolio needs to include a “mutual fund” made up of “stocks” that celebrate officiating. We do not do enough of this. We need to better enjoy each other’s successes. We know what that success smells and looks like. Others don’t. When we see it, we need to say it and say it loud: I am a referee, and I am proud.

Now, to a bit of battle-ready advice: If we intend to be effective and to also enjoy this business, as sports turns loud, unforgiving and vindictive, we need to double-down on a few things. Toughen up. Officiating isn’t for the faint of heart. We need mental toughness and an iron will. The assignments won’t get any easier later. We need to keep our heads down but our antennas up. We need to better understand when to talk and when to shut up. When in doubt, choose the latter.

What we are facing is daunting. Relying on others to make our world better is hope, but that isn’t a strategy. We can take care of most of our needs ourselves. Let’s get on with it.

Chief Strategy Of cer/Publisher

Barry Mano

Chief Operating Of cer/Executive Editor

Bill Topp

Chief Marketing Of cer

Jim Arehart

Chief Business Development Of cer

Ken Koester

Managing Editor

Brent Killackey

Assistant Managing Editor

Julie Sternberg

Senior Editor

Jeffrey Stern

Associate Editors

Brad Tittrington

Scott Tittrington

Assistant Editor

Joe Jarosz

Copy Editor

Jean Mano

Director of Design, Digital Media and Branding

Ross Bray

Publication Design Manager

Matt Bowen

Graphic Designer

Dustin Brown

Video Coordinator

Mike Dougherty

Comptroller

Marylou Clayton

Data Analyst/Ful llment Manager

Judy Ball

Marketing Manager

Michelle Murray

Director of Administration and Sales Support

Cory Ludwin

Of ce Administrator

Garrett Randall

Client Services Support Specialists

Lisa Burchell

Sierra Miramontes

Trina Cotton

Editorial Contributors

Jon Bible, Mark Bradley, George Demetriou, Alan Goldberger, Judson Howard, Peter Jackel, Luke Modrovsky, Tim Sloan, Steven L. Tietz

These organizations offer ongoing assistance to Referee: Collegiate Commissioners Association, MLB, MLS, NBA, NCAA, NFHS, NISOA, NFL, NHL, Minor League Baseball Umpire Development and U.S. Soccer. Their input is appreciated.

Contributing Photographers

Ralph Echtinaw, Dale Garvey, Carin Goodall-Gosnell, Bill Greenblatt, Jann Hendry, Jack Kapenstein, Ken Kassens, Bob Messina, Bill Nichols, Ted Oppegard, Heston Quan, Dean Reid, VIP

Editorial Board Mark Baltz, Jeff Cluff, Ben Glass, Reggie Greenwood, Tony Haire, John O’Neill, George Toliver, Ellen Townsend

Advertising 2017 Lathrop Ave., Racine, WI 53405 Phone: 262-632-8855

advertising@referee.com

REFEREE (ISSN 0733+1436) is published monthly, $46.95 per year in U.S., $81.95 in Canada, Mexico and foreign countries, by Referee Enterprises, Inc., 2017 Lathrop Ave., Racine, WI

At a referee development camp that I attended, the camp director began with a single question: “Who is your agent?”

After a period of silence that seemed to last forever, he answered his own question with one word: “You.”

As odd as it may seem, you are your own agent. You are not like professional athletes whose agent makes or negotiates many decisions for them. It is your responsibility to create your own schedule, be in demand and prove that you can do the job. You are responsible for the number and level of games you work. In fact, if you want to become successful as an official, it is crucial to understand that you are responsible for almost everything that happens to you.

However, as the late philosopher Jim Rohn once said, “When you’re playing the game, it’s hard to think of everything.” You need some help. Maybe you need a mentor, or maybe you just need someone in your corner to get your foot in the door. That is where the assigner comes into play. Two roles. One of the interesting things about sports officials is that we have the dual role of athlete and agent. On one hand, we are responsible for performing at our very best each and every game we

work. On the other hand, we must also make sure that we have games to work in the first place. Having a solid relationship with your assigner is perhaps one of the best things you can do to advance your officiating career. It can ensure that you are always in demand.

The main reason for having a great official-assigner relationship is simple and obvious: You want to work bigger, better games — and more of them. It won’t happen overnight. But with diligence, patience and hard work, you can get there.

Officials are considered to be “free agents.” You can only eat what you kill. In the entrepreneurial world, we say that increasing your rewards — in the case of officiating, that is your game count — starts with increasing your value. The more valuable you become as an official, the more games you work, the better games you work and the more satisfied you will be knowing that you are very good at what you do.

What are some ways you can make yourself more valuable to your assigner?

Hard, hard work. I know it’s cliché, but it’s true. Hard work will get you noticed not only by assigners, but by coaches and other officials. You make yourself desirable as

someone other officials want to work with and that assigners want to hire. Simply put, if you are not seen as a hard worker, it will be harder for you to convince your assigner that you are willing to work bigger and better games.

Assigners are not in the business of gambling. Their jobs depend on the quality of officials they send to games. They want to know that the crew they put out on the court or field will get the job done.

Coaches do take notice of hardworking officials, and they may actually tell assigners what a good job you did. That will definitely separate you from the officials who get little to no positive feedback at all.

Work with the rookie. Assigners are always looking for more experienced officials to work with new officials. You can make your assigner’s job so much easier — and enhance your schedule — by offering to work games with a rookie or a less experienced official. Veteran officials are accustomed to working with other veterans. We all like working with people we already know. But if you work with someone new to you, you may find you’ve found another official you trust and with whom you feel comfortable working.

Take the game nobody wants. That might mean doing the Sunday

(Sports Officials Security Program)

$6 million General Liability Coverage

Excess coverage for claims for bodily injury, property damage and personal and advertising injury (defined as slander or libel) up to $6 million per occurrence general liability limit with a personal aggregate of $14 million.

Assault-Related $15,500 Coverage

Provides coverage for certain legal fees and medical expenses and game fee losses resulting from injuries suffered when an official is the victim of an assault and/or battery by a spectator, fan or participant while officiating.

Up to $100,000 coverage for claims involving a challenged game call which resulted in a claimed financial loss or a suit against an assigner by a disgruntled official.

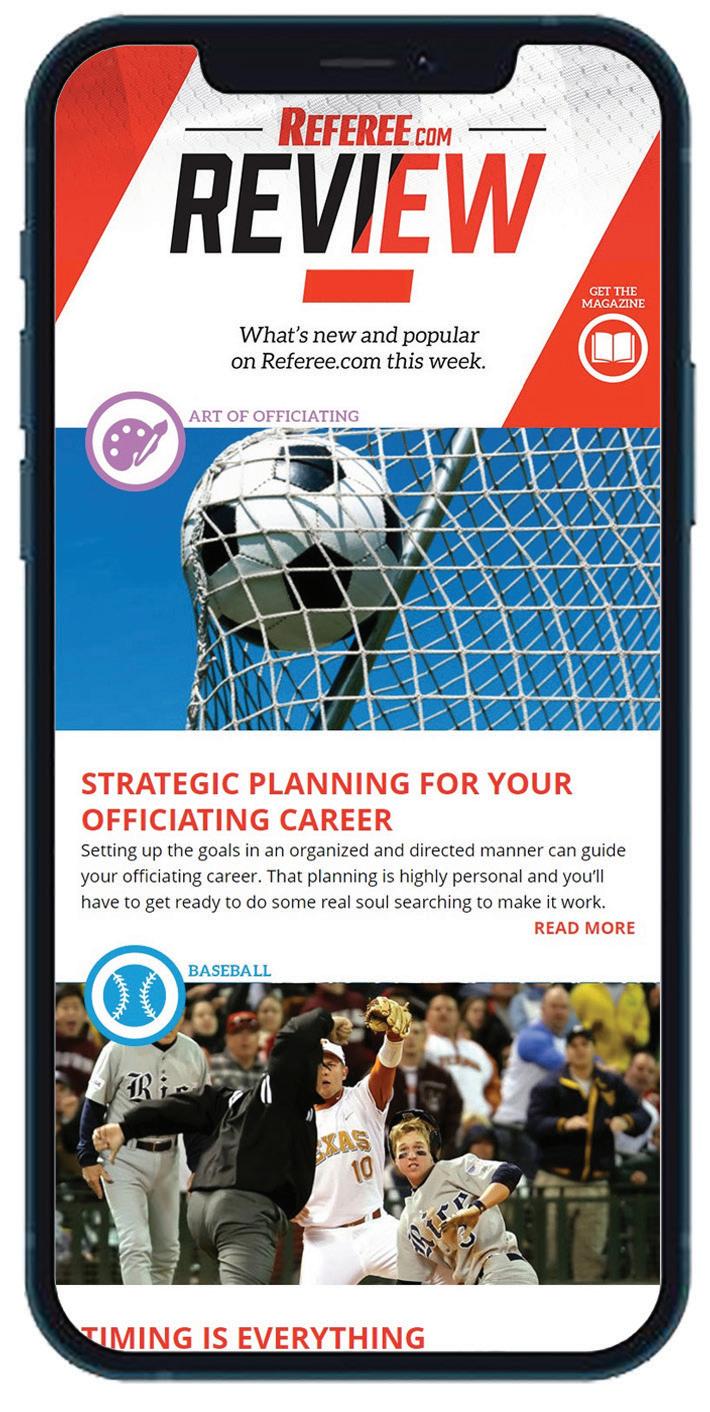

Referee Digital Magazine

Allows you access to a digital customized MHSAA-version of Referee magazine to read wherever you’re on the go. MHSAA NASO members will receive exclusive MHSAA content through the digital magazine. Referee is the number one source of information for sports officials, written by officials. Each issue includes news columns and journalof-record reports and deep-coverage sport-specific sections complete with rule interpretations and caseplays.

Referee Magazine (NASO Print Edition)

MHSAA members have the option to upgrade to the print version of the magazine, delivered to your mailbox every month. 84 pages of in-depth feature stories as only Referee can report them.

It’s Official Newsletter

Monthly 16-page newsletter providing association news, information, caseplays and educational product discounts.

Marriott VIP Card

Provides discounted rates at Marriott & Starwoodbranded hotels within the US and Canada, subject to availability.

With the VIP card, NASO members may receive a room rate of up to 25 percent off the regular price at participating hotels where space is available. The Athletic VIP card must be shown at check-in.

Registration Discount to The Sports Officiating Summit Members only registration discounts.

Ump-Attire.com

10% discounts

Member Information & Consultation Program (MICP)

LockerRoom

NASO LockerRoom

Online newsletter includes latest news on NASO, officiating techniques and philosophy.

Interactive Sport Quizzes

Online access to sport quizzes that will help you improve your knowledge of the rules.

Officiating Resources

Special Members-only buying discounts on Referee and NASO publications. Savings up to 20%.

Provides help when you need to sort out an officiating related issue, includes both free information and free consultation with a knowledgeable person.

Address:

Phone:

Web:

Email:

2017 Lathrop Ave Racine, WI 53405

262-632-5448

naso.org

naso@naso.org

NASO covers common gaps in other officiating insurances, protecting you when other officiating coverages come up short.

morning game, the game on what was supposed to be on your night off, or the one between cellardwellers that won’t show up on the 10 p.m. news.

Our local association has the “Fireman Award” for the official who accepts the most lastminute game turnbacks. Making your assigner’s job easier will increase your value as an official tremendously.

Keep up your availability. Keep your schedule up to date on a regular basis. Turn in all your paperwork on time. When you accept a game, keep it. One of the easiest ways to annoy your assigner is to constantly decline games they offer you because you fail to block your schedule. If you are constantly wondering why you aren’t getting games, that may be the reason why.

One of the logistics coordinators for our development program loves to use the term “low maintenance.” That means keeping things simple: Review your schedule regularly, accept games that are offered and move on. Be low maintenance, and the rest will seem to take care of itself.

Network at local meetings. Introduce yourself to the assigners. Talk to the officials who work at the level you want to work. Demonstrate to them that you are willing to work hard and are open to learning from each game you officiate. Don’t be pushy with them, but show them you are ambitious and ready for whatever game you accept.

And finally, remember that the bridge between you and your games is your assigner. Treat him or her with the same courtesy you would treat your family members. According to Dale Carnegie’s book How to Win Friends and Influence People, 85 percent of success or failure in any field comes from communication and dealing with other people.

Understanding that one principle will propel you forward more than you can imagine, no matter what you do in life — because you are your own agent in officiating and in life.

Officials must be decisionmakers versus reactors. Officials are trained to make decisions based on plays and not just be reactors to the action. Rely and lean on your experiences and training to execute proper judgment on plays. Rules knowledge and familiarity to having seen a play or situation before helps to make good quality decisions. In football, there are many times officials must decide whether or not to throw a flag on a particular play. Knowing what effect the potential flag has on the play is part of that decision-making process. For example, an official must determine if a player is holding his opponent or if the blocked player can fight through the contact, as well as whether the action has a material effect on the play. Is an advantage being gained?

In soccer, the striker has the ball along the wing, beats a defender, is turning the corner to the goal and is inside the penalty area when a defender comes in to make a tackle on the ball. The tackler is very close to committing a foul. Everyone looks to the referee to make a decision on the play. Is the tackle legal and a no-call correct? Or is the tackle a foul resulting in a penalty kick giving the attacking team a chance to tie the game, forcing the overtime shootout?

In that situation it is easy to react — to empathize with the team that has worked to tie the game. A reactor may just go with a penalty kick because he or she is caught up in the emotion of the game. However, an official is there to make a ruling on the play. Officials have the training and ability to put aside the emotion and bias of the moment to make an accurate decision. Volleyball officials have many different decision-making processes to go through in each rally. They must determine if the play at the net is legal and whether the net is contacted, for example. Is there prolonged contact with a ball or is it legal? Officials should not react to a play that looks unusual, but instead use their training and rules knowledge to determine a fault.

Like volleyball, basketball officials have decisions to make on every play. Foul? Violation? Some of the best decisions officials make are no-calls. Is that spin move traveling or not? Did the established pivot foot return to the floor before the shot attempt or pass?

If so, it’s traveling. Be an accurate decision-maker and don’t let crowd or coach reaction sway you.

Decision-making involves more than just the plays in the game. Many game management situations involve decision-making. Players and coaches howling from a dugout present issues for umpiring crews. A decision-maker deals with the issue before it becomes an actual problem. A reactor lets the chattering continue, does nothing about it and before long has seen the issue build to an unmanageable level. Use your training and experience to make adequate decisions about the events that occur in your games and matches. Do not be influenced or judge a play by a reaction, whether anticipating a play or being influenced by the external noise.

quick tipOfficiating education starts with the rules. Missed judgment calls can sometimes be excused, however there is no excuse for misapplication of the rules. Reading the rulebook can be daunting, but there are additional ways to tackle it. Immediately after reading each rule and subsection, imagine a related play and visualize applying the rule. Then write down quiz questions related to the rule and the play. That will re-enforce the rule in your head and you will have a handy quiz for later review. You should have your casebook handy when studying as well. After you have jotted down your quiz questions, look up that same rule application in your casebook and read through it, making adjustments as needed.

Privacy is a hot issue in today’s world and officials need to be especially vigilant in protecting theirs. What personal information should you give, if any? To whom?

Nothing like that friendly coach strolling over before a contest and just wanting “to get to know you.” In most cases, it’s no big deal to answer some routine questions before the game. Keep it short and professional. Don’t volunteer anything and don’t fudge about your experience because a coach can verify information you give.

Certainly it depends on the questions, but there is going to be enough going on once the game starts, so you don’t want to start off on the wrong foot by telling a coach you would prefer not to talk to him or her. If you encounter a chatty coach, the conversation likely won’t involve any requests for your phone number. The best action is to move to another spot and find something to do.

Appearances won’t be good if you are talking to any coach for an extended period of time. And how about the friendly, caring fan that stops by your location before a contest and says hi and wants to know your name? At the most, just tell what association or conferences you are from. Hopefully that will make the fan go away.

In the heat of the contest, all of a sudden the coach has forgotten your name and wants you to remind him or her of it — right now! You are trapped in that sense and you can either pretend, “I can’t hear you,” or provide your name. If the coach has you a little upset, you can always spell it out, nice and slowly with just a touch of sarcasm. Of course, you might kick yourself in the morning if you get overly dramatic with the spelling of your name.

In that situation, providing your name is probably what you need to do. Remember that the coaches will likely have your name anyway, either through the scorebook or a rating card you present before the game. Refusing to identify yourself, or making it difficult for them to do so, makes you look petty.

A situation could also arise when you’re standing near an injured player who is receiving medical attention.

All of a sudden the coach takes that opportunity to let you know he or she has some serious concerns about your work. The coach wants to know your name and where you’re from. In such a situation, it’s best to advise the coach to please take care of the player. Then move away and not get into give out information at that time.

After the game is when the interest in who you are may peak. It’s the rare official who has left every assignment without some verbal shots from someone. If you

have someone following you to your car and asking your name, a short professional response could be, “My name is (your name here). I’m sorry you’re upset.” All the while you are heading to a safe harbor. However, there is no responsibility to provide any personal information outside of who you are. If you feel you need, tell them to contact the school, the league or assigner, whichever is appropriate. There is a formal means to obtain that information and that’s through the assigning entity or governing body.

Barry Mano’s Publisher’s Memo (12/22) correctly points out the hard skills have quickly become recipe for success in of ciating. Of cials are often now judged on how quickly they submit game reports online, how quickly they accept assignments “on the platform” and so on as much as they are on their on eld performance. Their administrative skills mean the difference in a playoff assignment.

One area he did not address is the technology and the skills needed to operate these technologies has changed who is attracted to and who is recruited to of ciate at all levels. And in some cases, I believe this shift to “hard skills” has become a barrier to entry for some aspiring of cials. This focus on the use of technology of all types is probably adding to the shortage of of cials as well.

Technology is transforming both off- eld and on eld duties of all of cials. It is also shaping how fans watch and consume games. And one result is the increase of controversial calls (as seen through the fans’ and commentators’ eyes) because video technology is used to make a ruling.

The unfortunate fact of the matter is that everyone involved in a game — including fans — are using rudimentary communication skills that contribute to the decline of the quality of sports at all levels. I was involved in a game recently where members of the crew spoke about penalties in acronyms — DPI, IBL, etc. That shorthand is not helping any of cial communicate clearly.

Technology is a tool of game management, it is not a game management system. Mano is correct — it is the soft, human, communication skills that make the true difference in game management.

Peter Shafer Lutherville, Md.I enjoyed the article “Give Me Five” in the 12/22 edition which quoted ve rules identi ed by Marcus Aurelius. Those ancient rules are all stated in the negative, e.g. “Do not do this, etc.” Stated in the af rmative, the ve rules are: Be diligent, Be neutral, Be articulate, Concentrate and, last but not least, Party!

The professional cornhole world has been rocked by a cheating scandal. Top-ranked doubles team Mark Richards and Philip Lopez were accused of using illegal beanbags during the 2022 American Cornhole League World Championships. Devon Harbaugh led a formal complaint, claiming the opponents were using beanbags that were too thin. Of cials inspected all of the beanbags being used and it turned out all of them — even the ones Harbaugh was using — were illegal. Competition continued with the inspected bags.

SOURCE: FOX NEWS

Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones dressed up as a blind referee — striped shirt, dark glasses and cane — for Halloween. The costume drew the attention (and the ire) of of cials as well as an advocacy group for the visually impaired. “He does have blind Cowboys fans,” said Chris Danielsen, director of the National Federation of the Blind. “They show up at games and put on headsets or listen on the radio. It may be something for him to think about.”

SOURCE: FOX NEWS

When Jeff Sill, Ventura, Calif., gets thirsty, he won’t settle for a 12-ounce bottle of water. He goes for the extralarge economy size. Actually, it’s just a stadium worker lugging a bottle for a water cooler to one of the dugouts during a playoff game.

Does it help or harm officiating when TV commercials feature elements of officiating, often poking fun at the situations for comedic effect?

SOURCE: REFEREE SURVEY OF 49 OFFICIALS

NEWTOWN, Pa. —

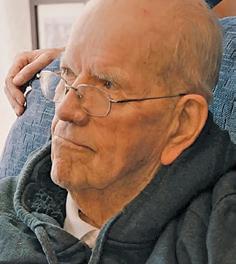

Art McNally, often referred to as “The Father of Modern Officiating,” died Jan. 1 at a hospital near his home in Pennsylvania. He was 97. On Aug 6, 2022, McNally became the first on-field official inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

“Art McNally was an extraordinary man, the epitome of integrity and class,” NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell said in a written statement. “Throughout his distinguished officiating career, he earned the eternal respect of the entire football community. Fittingly, he was the first game official enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. But more importantly, he was a Hall of Fame person in absolutely every way. Our thoughts go out to his wife, Sharon; his children, Marybeth, Tom and Michael; and his grandchildren.”

McNally joined the NFL in 1959 as a field judge before moving to the referee position in 1960. He worked on the field until he was hired as the NFL’s supervisor of officials in 1968. He is credited with bringing technology to NFL officiating, including introducing film study and instant replay. The development of his department eventually led to his directing five people who coordinated a staff of 112 game officials and

A 16-year-old student from Excel High School in Boston is facing a misdemeanor charge of assault and battery after police say he punched a referee in the face during a Dec. 28, 2022, game at Cohasset High School. In the wake of the attack, the gym was cleared and the game was canceled. News reports said the referee did not require medical

were responsible for the scouting, screening, hiring and grading of crews for each NFL game.

In speaking to the Associated Press about McNally’s induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, retired NFL referee Ed Hochuli said, “There have been some incredible officials along the way who can make a great argument they ought to be in the Hall of Fame. But none of the officials would disagree that if there’s only one or if there is a first, Art McNally should be the guy.”

McNally retired from the NFL in 1991 and became supervisor of officials for the World League of American Football in 1992. He remained a consultant to the NFL through 1994, and in 1995 returned to the league office as an assistant supervisor of officiating until 2007. He remained an observer of NFL games through 2015, working with officials on a weekly basis.

McNally was the inaugural recipient of the officiating industry’s highest honor, the Gold Whistle Award, which was presented to him by NASO in 1988.

Since 2002, the NFL annually has given an award bearing McNally’s name to an NFL game official who exhibits “exemplary professionalism, leadership and commitment to sportsmanship” on and off the field. The officiating command center at NFL headquarters also bears his name.

attention. One witness told Fox News the player punched the referee after thinking he was charged with another foul, but the referee had called the opposing team for traveling. Because the student is a minor, his name was not released. He was scheduled to appear in Quincy Juvenile Court. In a statement, the Massachusetts Interscholastic Athletic Association condemned violence and physical anger in

NEW YORK — There will be 10 new MLB umpires joining the staff in 2023 after a slew of veterans turned in their retirement papers at the end of this past season.

The departing umpires include seven crew chiefs: Ted Barrett (25 years of MLB service time), Greg Gibson (23 years), Tom Hallion (29 years), Sam Holbrook (21.5 years), Jerry Meals (24 years), Jim Reynolds (22.5 years) and Bill Welke (22.5 years). Also retiring are Marty Foster (23 years), Paul Nauert (21.5 years) and Tim Timmons (22.5 years).

Collectively, the group of retiring umpires worked 18 World Series. Barrett worked the most World Series — five — during his years on the major league staff. Holbrook worked three World Series; Hallion, Meals and Reynolds each worked two. Gibson, Nauert, Timmons and Welke each worked one.

“I’m so grateful to have the career that I did and to be a part of baseball history,” Barrett told ESPN. “I’m incredibly proud of the crews that I worked with and everything baseball provided for me. For all of us.”

During a mid-October See “MLB Retirements” p.14

sports, stating such behaviors “have no place on our athletic elds, courts or hockey rinks.”

The North Carolina High School Athletic Association’s board of directors approved a 10 percent increase in per-game fees for all sports, rounded to the nearest dollar. The raise, which took effect Jan. 1., came

after an ad hoc subcommittee took an in-depth look at the state of high school of ciating. The board also eliminated the policy of paying less per game for a doubleheader than a single game. Administrators also pledged to review compensation every other year. Subcommittee Chairperson Steve Schwartz, who is an of cial, told the board that as many as 800 high school basketball of cials could have

07/30-08/01

The 2023 Sports Officiating Summit will be in Southern California this year and theme is all about sportsmanship. You won’t want to miss the cutting edge discussion focused on real solutions. What is the officials role? How does poor sporting behavior impact our games? How does it impact our industry? Survey after survey confirms that sportsmanship issues are at the heart of the critical officiating shortage in our nation.

More than 500 officiating industry leaders from all sports and all levels of competition will be on hand. If you care about the future of sports officiating, then you should be in Riverside this summer. Let’s gather – let’s talk.

LUBBOCK, Texas — In late December, the College Baseball Hall of Fame announced its Class of 2022. Among the 10 inductees selected was longtime umpire Jim Garman, who made eight appearances in the NCAA Division I College World Series.

“I am humbled and honored to be a part of it,” Garman said.

Garman joins Bill Almon, Roger Cador, Casey Close, Ken Dugan, Condredge Halloway, Andy Lopez, Art Mazmanian, Ken Ritter and Rickie Weeks in the 2022 class.

Garman said he knew there was a chance he’d be inducted after he was nominated, and that chance became a reality when Craig Ramsey, the College Baseball Foundation board chairman, called to congratulate him on his induction.

Garman was a postseason regular during his 40-year career as an umpire in the Pac-12, Big 12, Big West and Western Athletic conferences. He made it to Omaha eight times (1987, 1988, 1993, 1997, 2002, 2005, 2008 and 2011) and also worked 34 Division I Regionals and 15 Division I Super Regionals. He also served as the Western Regional coordinator for the National Umpire Improvement Program during his tenure.

Outside of college baseball,

chosen to not make themselves available Jan. 1-14 if pay was not increased. In addition to recommending the pay increase, the ad hoc subcommittee also recommended doubling down on penalties for poor sportsmanship whether it involved players, coaches or fans.

Jeff Cooney, the supervisor of football officials for the Patriot League and Ivy League, retired

Garman worked the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, Spain, the 1988 Junior World Championships, the 1990 World Championships and five years in professional baseball (1977-81), making it to the Double-A level.

“It’s those World Series moments and the guys I worked with that stand out,” Garman said as he reflected on what those years spent in uniform meant to him. “There isn’t one moment in particular that stands out, it’s a culmination of everything.”

The members were inducted into the Hall of Fame as part of the College Baseball Night of Champions celebration held Feb. 3 in Omaha, Neb., site of the College World Series. This year’s event returned to in-person as the last two years were held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This class checks all the boxes … it is an accomplished list,” Mike Gustafson, president and CEO of the National College Baseball Hall of Fame, said in a statement.

Other umpires who have been inducted into the College Baseball Hall of Fame include Dick Runchey (2011), Rich Fetchiet (2012), Dale Williams (2013), Henry “Hank” Rountree (2014), John Magnusson (2015), Gus Steiner (2016), Jon Bible (2019), Randy Christal (2020) and Dave Yeast (2021).

from the position at the end of 2022. Cooney was hired in 2019 when the leagues moved to a six-conference officiating alliance that also includes the American Athletic Conference, Atlantic Coast Conference, Big South and Colonial Athletic Association.

“Jeff has been a valuable resource for our coaches, student-athletes, officials and staff regarding rules changes and instant replay,” said Patriot League Commissioner Jennifer Heppel. “He will be missed not

MLB Retirements continued from p.12

broadcast, Hallion told WHASAM radio of Louisville, Ky., where Hallion resides, that he worked his final game in Cincinnati.

“Did my last game which was nice,” Hallion said. “Had my whole family up for the game. It was a little emotional. A couple tears came to my eyes. But as I walked off the field, a couple players came over and said, ‘Hey, congratulations and good luck.’ And then my … longtime friend and partner for years, Phil Cuzzi, came over and hugged me. We both cried. It was kinda like this was it; this was the end. It was weird, but I’m very excited about moving forward.

“It’s time to call it an end,” Hallion said.

Hallion was crew chief on the 2021 World Series and may have thought about retiring after that season. His interview with a Kentucky radio station just before the World Series left that impression, but he came back for one more season.

Gibson’s retirement was reported in the 1/23 issue.

“For me, it was time,” Gibson said. “The day I know I can’t physically perform the job, I was getting to that point. I need to get out of the way and let someone else have the job.”

only within the Patriot League but throughout college football for his contributions during his accomplished career.”

Cooney served as an on-field official for 35 years, including 25 seasons of collegiate experience with 10 years in the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) and nine years in the Football Championship Subdivision (FCS). He was assigned to FCS Playoff games from 2002 through 2011, including the 2011 FCS National Championship Game.

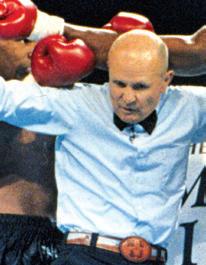

Steve Smoger, a Hall of Fame boxing referee who worked more than 200 title fights, died Dec. 19 from an undisclosed illness. While widely reported he was 72, one boxing commissioner insisted Smoger was born in 1943, which would make him 79.He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2015.

SOURCES: THE PATRIOT LEDGER, THE JOURNAL NOW, THE PATRIOT LEAGUE, FOX NEWS, BOXING NEWS ONLINE

RENO, Nevada — Mills Lane, the hall of fame boxing referee whose assignments were interrupted by earchomping, a wayward skydiver and a heavyweight having a nervous breakdown, died at his home on Dec. 6, 2022. He was 85.

Lane had been incapacitated since suffering a stroke in spring 2002. It left him partially paralyzed and virtually unable to speak.

“The past 20 years after the stroke were pretty tough, to be honest,” Lane’s son Terry said. “My mom took care of him since the stroke; he never spent one night in a nursing home. I don’t know if Dec. 6 is my dad’s date of death or a new life for her.”

Lane’s career in boxing began after he joined the Marines in 1956. After being defeated in the U.S. Olympic trials in 1960, he turned pro the next year. He lost his first bout, then rattled off 10 straight wins — six by knockout — before retiring in 1967.

Upon graduating from law school at the University of Utah in 1970, he returned to the ring as a referee and worked his first title fight the following year. He became one of the most skilled and famous referees, working bouts featuring Muhammad Ali, Thomas Hearns, Julio Cesar Chavez and Mike Tyson.

On Nov. 6, 1993, a bout between Evander Holyfield and Riddick Bowe was interrupted when a man used his powered paraglider to fly into the arena, eventually crashing into the side of the ring. Four years later, Oliver McCall began acting strangely during his fight with Lennox Lewis. He threw few punches, walked around the ring crying and refused orders from his corner. Fifty-five seconds into the fifth round, Mills waved off the fight and declared Lewis the winner.

But Lane’s most memorable decision was disqualifying Tyson for twice chewing on Holyfield’s ear. The first bite resulted in Lane taking points away from Tyson. But the second ended the fight.

Lane retired from the ring in 1998, taking his famous phrase, “Let’s get it on!” with him. A former district attorney and judge in Nevada, he appeared on a syndicated television program, “Judge Mills Lane,” from 1998-2001. His image and catchphrase were also used in an adult stopmotion Claymation series, “Celebrity Deathmatch,” that appeared on MTV.

In 2009, Lane received the Gold Whistle Award from NASO. Unable to attend himself, his wife and son accepted the award on his behalf. At

the time of the presentation, Marc Ratner, former Nevada State Athletic Commission executive director and now vice president of regulatory affairs with the Ultimate Fighting Championship, said, “When he walked into the ring, he brought a big-time feel to the event when he said, ‘Let’s get it on!’ He was a very special referee. He was always on time, always neatly dressed and the respect and command he had in the ring was extraordinary.”

CONTRIBUTING SOURCE: ESPN

of men’s officials development at US Lacrosse. Recognizing the sport had served as one of his first antidepressants, he decided to share his story with US Lacrosse and the media.

“I’m at peace with the part of me that hates myself,” said Corsetti about agreeing to tell his story. “I have more agency over it than I ever did. It just took a hell of a lot of ups and downs to get to that point.”

piece, Corsetti shared that he first began struggling with mental illness at the age of 15 — “I started getting these whispers, odd thoughts that floated by the edges of my mind. I’d wake up and think, ‘Why bother?’” — and he first contemplated taking his own life in April 2008 following a disappointing performance while playing lacrosse during his senior year at Pace Academy in Atlanta.

Over the course of the next 12 years, he would incur three serious attempts on his life and several hospitalizations.

While battling his mental health demons, Corsetti became a respected high school and college lacrosse official, as well as the manager

The story included several photos, including one of a tattoo of a semi-colon on Corsetti’s right wrist, signifying his connection to Project Semicolon, a suicide prevention organization. The semicolon represents a sentence an author could have ended but chose to continue — or a life someone has chosen to continue when facing thoughts of suicide.

Following the story’s printing in the two publications, Corsetti accepted an invitation to speak at the 2019 NASO Sports Officiating Summit in Spokane, Wash., where his 15-minute address as part of the Referee Voices series left a lasting impact on those in attendance.

Corsetti is survived by his fiancée, Lisa; his parents, Mary Jo and Lou; and his sister, Caitlin Corsetti Luscre.

Play is stopped when the ball becomes immediately dead by rule. It is obvious the ball becomes dead when a foul is not caught or a batted, thrown or pitched ball goes out of play; however, there are many other acts that also cause the ball to become immediately dead. The vast majority of those cases involve interference by the offense, but there are several situations for which a cookie-cutter approach does not

work. Umpires must recognize those acts and know how to react. Except where noted, the material applies equally to NFHS, NCAA and pro rules.

The umpire. When an umpire does more than make a call, it could be an immediate dead ball, with or without consequences; a delayed dead ball; or the ball simply stays live.

The ball is immediately dead if a fair ball touches an umpire in fair territory before touching an infielder, including the pitcher, or passing

an infielder other than the pitcher. It is interference and the batter is awarded first base; other runners advance only if forced.

However, if a fair ball touches an umpire after having passed an infielder other than the pitcher, or after having touched an infielder, including the pitcher, the ball remains live and in play (NFHS 5-1-1f1; NCAA 6-1h, 6-2f Note; pro 5.06c6).

Play 1: With the bases loaded and one out, B5 hits a line drive past

F5. The fair ball hits the third-base umpire in the foot and deflects to F6. R3 scores, but B5 is thrown out at first. Ruling 1: The ball is live and in play; the run scores and B5 is out.

The ball also remains live and the contact is ignored if a pitch or thrown ball touches an umpire (no possession) (NFHS 3-2-3; NCAA 6-1b, 8-3i; pro 6.01f).

Play 2: B1 swings and misses for strike three. That pitch is missed by F2, and B1 starts for first. The ball strikes the umpire and is easily retrieved. F2 fires to first to retire B1.

Ruling 2: The play stands, B1 is out.

Play 3: R2 attempts to steal third. F2’s throw hits the base umpire.

Ruling 3: The play stands.

Play 4: With runners on first and third and one out, B4 hits a onehopper to short. F6 fires to second to start a double play, but the throw hits the umpire. All runners are safe and R3 scores. Ruling 4: The play stands.

A delayed dead ball occurs when an umpire hinders or impedes the catcher’s throw to prevent a stolen base or pick off a runner (NFHS 5-12c; NCAA 6-3a; pro 6.01f Cmt.). If the throw is prevented or does not retire the runner, interference is called. The ball becomes dead and runners return to their bases occupied at the time of the pitch. However, if the throw retires the runner, the interference is ignored (NFHS 8-4-2h; NCAA 6-3a Note; pro 5.09b4).

Play 5: R1 is attempting to steal second. F2’s arm accidentally strikes

the umpire’s mask. F2 hesitates briefly, then fires to second (a) in time, or (b) not in time to retire the runner. Ruling 5: In (a), the contact is disregarded since the runner was retired. In (b), runners may not advance when the plate umpire interferes with the catcher’s throw. R1 is returned to first.

Play 6: With a runner on first, F2 receives the pitch and pivots to throw behind R1. He steps on the umpire’s foot and throws wildly into right field. R1 advances to second. Ruling 6: The ball is dead and R1 returns. Since F2’s throw did not retire the runner, it is umpire interference.

An example of an immediate dead ball with no consequences is when the umpire hinders the catcher on an attempt to throw the ball back to the pitcher; no runners may advance.

Play 7: With a runner on first, F2’s throwing arm strikes the plate umpire as he is throwing the ball back to F1. The ball rolls toward a dugout. R1 takes off and makes it to second safely. Ruling 7: The ball is dead. Since F2’s throw did not retire the runner, umpire’s interference is ruled and R1 must return.

The catcher. Contact between the catcher and batter-runner on a batted ball can also result in any of three ball statuses: live, dead or delayed dead. If there is contact while the catcher is fielding the ball, there is generally no violation if they are both “where they are supposed to be and doing what they are supposed to do.” Neither interference nor obstruction is called if neither player attempts to alter the play; the contact is considered incidental (NFHS interp.; NCAA 7-11f Exc. 4; pro 6.01a10 Cmt.). Flagrant contact on the part of either player is a violation and the appropriate call, interference or obstruction, should be made.

When a batter-runner and a catcher make contact following a bunt out in front of the plate, the home plate umpire must rule whether incidental contact, interference or obstruction has occurred, and how that ruling determines whether the ball remains live, is an immediate dead ball or is a delayed dead ball.

The percentage of current umpires who joined the MLB staff on a full-time basis prior to the 2000 season.

The percentage of full-time umpires who will have joined the staff since the 2020 season, pending the hiring of 10 new umpires to fill spots opened by recent retirements.

The 2023 NFHS Baseball Casebook contains an error related to an offseason rule change involving jewelry. Caseplay 3.3.1 Situation PP states that upon discovery of a player wearing a class ring, the umpire should direct the player to remove the jewelry and that if the player does not comply, the player is ejected from the contest. The NFHS has acknowledged this is an error, as changes to rules 1-5-12 and 3-3-1d now allow for jewelry to be worn, so long as it is not deemed by an umpire to pose a danger to the player, teammates and opponents.

Are you a visual learner? Do you achieve a better understanding of rules and mechanics through the use of artistic aids rather than the written word? If so, High School Baseball Rules Simplified and Illustrated should be a part of your ongoing education. The 222-page manual, produced in partnership with the NFHS, uses PlayPics and MechaniGrams to bring high school baseball rules to life and allow officials to “see” the game. The manual costs $10 and is available at store.referee.com/ baseball.

In each question, decide which answer is correct for NFHS, NCAA or pro rules. Solutions: p. 85

1. With the bases loaded and two outs in the bottom of the last inning, the score is tied. B6 is hit by the pitch and awarded first base. R3 legally touches home and scores and B6 legally advances to and touches first. R2 starts toward third but joins the celebration near first before he touches third base.

a. R2 is out for making a travesty of the game and the game is continued.

b. The game is over. The run scores as only B6 needed to go to first and R3 touch home.

c. R2 is out for abandoning his effort to run the bases and the game is continued.

d. R2 is out only if the defense properly appeals R2 missing third base and the game is continued.

2. When a coach physically assists a runner during play:

a. The runner is out and the ball is immediately dead.

b. The runner is out and the ball remains in play. All other play stands.

c. The runner is out and the ball remains in play. All other runners not put out during the play return to their bases at the time of the infraction.

3. The umpires call an infield fly that is intentionally dropped.

a. Call time, the batter is out and all runners are awarded one base.

b. The ball remains live, the batter is out and any runners advance at their own risk.

c. The ball is dead and the batter is awarded first base. Any runners advance one base if forced.

4. If a runner on first who is forced to second interferes with the pivot man at second, interference resulting on a double play is not called unless the defense had a chance to complete a double play.

a. True.

b. False.

If interference is called, the ball is immediately dead. If obstruction is called, play continues in NFHS, but is immediately dead in NCAA and pro because the batter-runner is being played on (NFHS 2-22-1; NCAA 8-2.3e1; pro 6.01h1).

Play 8: B1 chops a ball down the first-base line. F2 starts for the ball as B1 is leaving the batter’s box. B1 collides with F2 from behind. Ruling 8: When the catcher is in the act of fielding a batted ball and a serious collision occurs from behind, the batter is out for interference.

Play 9: Right-handed B1 bunts

the ball down the first-base line. He starts for first as F2 starts to field the ball. They brush shoulders as both proceed toward first. Ruling 9: The play stands. The contact is incidental.

Play 10: B1 tops a ball down the first-base line. He is advancing toward first base while F2 comes up from behind to field the fair ball. F2 inadvertently trips B1, retrieves the ball and tags him. Ruling 10: When the batter-runner is tripped from behind, obstruction should be called. B1 is awarded first base.

George Demetriou, Colorado Springs, Colo., is the state’s rules interpreter.

Newer umpires sometimes think if they master the rules and mechanics and have good judgment their careers will take a steady upward trajectory. There’s more to successful umpiring. Little things I call intangibles can help or ruin us in others’ eyes.

Years ago, a famous athlete made a TV commercial with this line: “Image is everything.” In effect, he said the reality of our proficiency doesn’t matter if people don’t perceive us in a positive light. How true. I’ve known umpires with solid skill sets who never got anywhere because they didn’t come across well. Conversely, others were weak in some areas but managed to create a positive image and got plum assignments and promotions that the first group wanted badly.

A longtime pro/college coach once told me he felt he knew whether an umpire could work by the time he got to the plate for the conference. Such things as physical appearance, body language, eye contact and demeanor told him whether the person was competent or in over their head. Was he wrong on occasion? No doubt. But that didn’t

matter because he thought what he thought. Perception.

I think there’s a presumption for or against us based on intangibles, meaning we will or won’t be assumed to be correct on close pitches or plays. Solid work can, of course, overcome a bad first impression, just as poor work can negate a good one, but I’d rather start on a positive note.

Do you show up at the site at the last minute? There can be circumstances beyond our control, but this sends the message the game is unimportant. Late arrivals also cause coaches consternation because they may be reluctant to let their pitcher begin their pregame routine until they know we’re there. When I had a role that let me poll college coaches about their pet peeves, umpires who arrived late was second behind those who talked too much with their players.

Are you overweight? Is your uniform dirty? Are your pants so tight they get caught on your shinguards when you rise out of your crouch? Does your shirt stick out after two innings? Does your cap have sweat stains? Such things tell the world you can’t get in position or survive on a hot day or are lazy or don’t care.

Play: With a runner on first base, B2 hits a foul fly ball deep down the left-field line. F7 makes the catch and falls into the stands. R1 was beyond second base when the fielder fell into the stands. Ruling: In all codes, R1 is awarded second (award is from time of pitch on an unintentional catch and carry), but if R1 does not tag up at first, he can be retired on a proper appeal. However, in NFHS, R1 cannot legally return to first to tag up because he was on or past a succeeding base when the ball went out of play. In NCAA, R1 can return to first to tag up as long as he is trying to return when the ball became dead. In pro, R1 can return to first and tag up because he did not touch third base, which in this play is considered the “base beyond” or “next base” for R1 determined at the time the ball went out of play (NFHS 8-4-2q; NCAA 8-6a Note 3; pro 5.09c2 AR, MLB Umpire Manual).

Hot Foot

Play: With the bases empty, B1 has a 2-2 count when he swings at and misses a pitch in the dirt. The ball rebounds off F2 and hits B1’s foot as he attempts to advance to first base. Ruling: In NFHS, B1 is only out if he intentionally interferes. In NCAA and pro, interference is called if B1 clearly hinders F2 in his attempt to field the ball. If the pitched ball deflects off the catcher or umpire and subsequently touches the batterrunner, it is not considered interference unless, in the judgment of the umpire, the batter-runner clearly hinders the catcher in his attempt to field the ball regardless the number of outs (NFHS 8-4-1a; NCAA 7-11h; pro 6.01a1).

Undeserved Souvenir

Play: B1 hits a fair ball down the right-field line. A spectator, believing it is a foul ball, picks it up. Ruling: The ball is immediately dead. The umpires will award the number of bases as to nullify the act of interference (NFHS 5-1-1g1; NCAA 6-4a, 8-3n; pro 6.01e).

Do you visit with players and coaches, especially on the home team, when you walk on the field? Walk to the plate stiffly, perhaps with a scowl on your face? During the conference, do you tell off-color jokes or toss your mask on the ground while reviewing the ground rules? Recite the rulebook chapter and verse? If so, you may be viewed as biased, condescending, disinterested, crude, a raw rookie or a rules technician, any one of which may cause you to start the game with two strikes against you.

Do you apply all the rules literally? The game was meant to be played a certain way, and if we don’t learn the advantage-disadvantage philosophy and apply the rules in light of it instead of in a hypertechnical manner, we’ll find ourselves in a world of grief.

Let me briefly mention four umpires who illustrate the importance of perception:

Joe had a wiry physique, moviestar looks and good judgment, mechanics and rules knowledge. But he looked so uptight that he

seemed scared. Coaches, like sharks that smelled blood, gave him so much guff that he eventually quit umpiring.

Tom was the best ball-strike umpire I ever saw but was 100 pounds overweight. Once coaches got to know him they accepted him, but he lost a lot of opportunities because of people’s negative assumptions about him.

Dick had a solid skill set but a Don Rickles-like sense of humor that could be stunning but also off-putting. Verbal jabs that he’d throw at peers, coaches, etc., to be funny, could come across as cruel and cutting, especially if you didn’t know him. Once, he said something during an NCAA tournament that an administrator took the wrong way and that was the last one he worked.

Harry did everything wrong mechanically on the bases and behind the plate and wasn’t swift with the rules, but he had excellent judgment and communication skills and looked like he’d worn a jock (which he had). In the eyes of coaches and people who could help him to advance, the latter outweighed the former so much that he ended up having a stellar college career.

I’m not sure newer umpires always recognize the importance of voice and signals in making calls. Do you raise your fist when an outfielder

catches a ball chest-high, go through gyrations when a runner is out by a step or give the big “strike three” on a swinging strike? If so, you might as well have “Not Ready for Prime Time” stamped on you. Are your signals smooth and fluid or jerky? Is your voice suited to the situation or so loud they can hear you in the next county? You don’t see MLB umpires throwing fits and screaming at the top of their lungs, even on eyelash plays. Everything they do is firm, crisp, but controlled, which projects a “not my first rodeo” image. One can sell a call without being flamboyant; in fact, I think the louder and flashier you are, the less likely you are to be convincing because you can come across as going overboard to mask your uncertainty.

In sum, you need a solid skill set but you must learn how to package it, for perception is more important than reality. Watch how successful umpires look, comport themselves, signal and the like. Experiment; some things you try will look good on you, but others won’t. With careful, objective analysis of yourself and perhaps help from your peers, you’ll hopefully be able to discard the chaff and keep the wheat, which could boost your career.

Jon Bible, Austin, Texas, worked seven NCAA Division I College World Series. In 2019, he was inducted into the National College Baseball Hall of Fame in Lubbock, Texas. *

During a clinic this past summer, a veteran NCAA umpire posed the following philosophical question to me:

“If you don’t have a good look at a tag play and have to make a guess, which way do you guess?”

OK, so let’s start by addressing the first thing many of you are thinking after reading that sentence: “We are never supposed to guess on the field.” That’s a rock-solid philosophy, except for the fact situations occur where we

do not have definite knowledge of what has transpired on a play. And when that happens, like it or not, we have to guess. We are working baseball, not volleyball — there is no provision in any of our rules codes that allows us to call for a replay. We have to make a decision with the information at our disposal.

The key is to make an educated guess and one that does not undercut our credibility as an umpire. Allow me to illustrate using the ongoing discussion that day with my fellow arbiter.

Let’s say you’re working home plate and a tag play develops. Due to the location of the catcher, the runner coming in from third base and the throw, you end up straightlined as the catcher attempts a swipe tag to the back of the baserunner. You have no certainty whether there was a tag before the runner reached home plate. It’s a 50-50 situation. Which way do you rule?

My esteemed colleague’s take? Rule the runner safe. Here’s the philosophy behind doing so.

You make an out call on this play. Video review is available and the offensive team’s head coach asks you to go to replay. The crew does so and there is a great camera angle that shows the catcher’s swipe attempt misses the runner. It’s clear and the crew agrees the call needs to be reversed.

Upon doing so, you as the ruling umpire are likely now going to be in the crosshairs of both coaches. The defensive team coach is not going to be happy the original call was reversed. That’s human sporting nature. However, just as problematic is going to be the thoughts of the offensive coach moving forward during the game. Because while the call reversal went in his favor, here’s what’s running through his head:

“How could you rule there was a tag and an out when you never saw a tag?” No matter how you try to slice it, the review confirms you made a guess on the play, and you guessed wrong.

Now, let’s attack it from the other angle. You make a safe call on this play. The defensive team coach knows he saw a tag from his angle and wants it reviewed. The crew takes a look at the video and it turns out the defensive coach is correct — the catcher’s glove nicks the baserunner’s jersey. It’s enough to reverse the call to an out.

Here comes the offensive coach for an explanation, to which you say: “Coach, from my angle on the field, I could not see a tag. That is why I ruled him safe originally. The video clearly shows there was a tag, necessitating the reversal.”

The offensive coach isn’t going to be happy. Again, human sporting nature. The difference is, you are not having to own up to making a guess about something that did not happen. Instead, you are admitting you did not see something, which is a reality every umpire faces on occasion.

Is it a fine line? Of course. The last thing we want is to have to regularly find a way to parse these types of situations. If we are having

to do so, it probably means we are not doing a very good job with our mechanics in the first place, which is a whole other discussion.

Also open for discussion is the fact many of the umpires reading this will never work a game involving video review. So, what then? The same philosophy should apply. While there may not be a camera to assist, it just may happen that the first-base umpire, with nothing else to look at, had a great view of the play and the tag, and is able to call you and your other partners together to make a crew-saving call. Again, you’d rather have to explain why you couldn’t see something — and your partner could — than explain why something materialized out of thin air.

On those hopefully rare occasions when we do need to flip the coin and make our educated best guess, make the guess that is less likely to cause your credibility to come into question. At the end of the day, it’s better to have them questioning your eyesight than your integrity.

Scott Tittrington is an associate editor at Referee . He umpires college and high school baseball, and officiates college and high school basketball and high school football.

Acommon mechanics and positioning error takes place in the two-person umpiring crew when the infielders move in as part of their pre-pitch positioning to be in place to cut off a potential run from scoring at the plate.

When there is any combination of runners that includes a runner at third base — except when there are runners on first and third — the base umpire, U1, is in the “C” position, between the pitcher’s mound and second base, slightly offset to the shortstop side of the infield. Because of the possibility of a pickoff play at third base in this situation, most base umpires will work

a “deep C” that creates an angle for an open look at the front edge of the third-base bag.

However, U1 is going to have a tough time staking claim to the same real estate if the infield decides to play in, as the “deep C” is in the immediate proximity of where the shortstop will want to set up shop. As such, U1 will often take a few steps backward, even sometimes ending up on the infield dirt, and will give a pre-pitch signal to the plate umpire to indicate a position behind the infielders so that, should the base umpire be struck by a batted ball, the umpiring crew recognizes the ball should remain live.

This is exactly the wrong thing for U1 to do.

As the MechaniGram illustrates, anytime U1 is in the middle of the infield, that umpire has catch/no-catch responsibilities for all line drives hit in the infield except the corner infielders moving back or toward a foul line and the pitcher moving in, left or right. If U1 starts in a position deeper than the two middle infielders, there is no way to see batted balls hit at the feet of the second baseman or shortstop. This creates the unenviable position of making the plate umpire responsible

for these rulings — a ruling PU is otherwise never responsible for — and sets the stage for confusion where a double call is made or, even worse, no call is made.

Instead of moving deeper and creating additional space, U1 must instead move forward and find a spot in the working area that will allow the base umpire to stay clear of any immediate play on a batted ball by a middle infielder, while still allowing for an angle to see these plays being made.

Can it feel uncomfortable? Yes, especially when a screaming line drive comes up the middle and U1 has to find a way to avoid being hit by the baseball and colliding with a diving shortstop. But with only two sets of eyes on the field, U1 has to trade a little bit of comfort in these scenarios to put the crew in the best possible position for any ensuing action that may occur.

Be prepared for the 2023 season! Your complete guide to the 2023 High School Baseball season includes the latest rules changes explained and simplified, the most up-to-date NFHS Points of Emphasis, Mechanics updates, umpiring tips and strategies, Caseplays with rulings, and test yourself Quiz Questions with answers.

In the past, it wasn’t uncommon to see many teachers swap their grading book for a whistle at the end of the school day, using their classroom management skills in a different school setting — as a sports official.

But in recent decades, the number of educators serving as officials has been on the decline.

According to a 2017 NASO National Officiating Survey, K-12 educators comprised 15.7 percent of the officiating pool. Many administrators in state high school association offices will tell you anecdotally the percentage was much higher just a few decades ago.

But the increased demands for accountability on educators — similar to that of officials, including the pervasive role that social media now plays — are preventing many individuals from considering officiating as an option, according to Jason Nickleby, coordinator of officials for the Minnesota State High School League (MSHSL) and current Big Ten football official.

“High-stakes testing and increased social,

emotional and mental health needs for students takes a toll on teachers and administrators,” Nickleby said. “Taking on additional responsibilities and time to become an official is something that many educators just can’t add to an already full plate.”

As teachers already deal with students in a supervisory role, sports officiating seems to go hand in hand with the profession.

“Teachers certainly have the skill set to become very good officials,” Nickleby said. “They are working with kids, they know how to handle kids and they know how to de-escalate situations. And they seem to have the right temperament. Teachers seem to be ideal.”

But officiating can often be a tough sell.

“The money is not great, and the coaches and spectators are out of control. So how do we convince people it’s worth it? It’s hard without a sales pitch,” said Will Anglin, a math teacher from Dawson County High School, 60 miles north of Atlanta.

Anglin is in his fifth

year officiating Georgia high school football. He also serves as the school’s new varsity girls’ head basketball coach in the winter and head boys’ golf coach in the spring. He said balancing teaching, coaching, working toward a master’s degree, officiating and family is sometimes quite complicated.

“My family is the most important, but with my schedule, they have sacrificed tremendously for me to do what I love,” Anglin said. “I think more teachers don’t officiate because of the time commitment. This leaves little time to spend with family or relax after a hard day’s work.”

The good officials spend countless hours studying film in preparation for their next game, said Anglin, the youngest official — in both age and experience — to work a Georgia High School Association (GHSA) state football championship game in 2020. At the time, he was 25 and in his fourth year of officiating.

“Like many, I thought officials just showed up on Friday nights,” Anglin said. But now he realizes that couldn’t be further from the truth. “For most officials, the season starts in May with study groups, camps and offseason training activities required to officiate on Friday nights. I think a lot of teachers are unwilling to put in the time.”

Nickleby knows first-hand the role and expectations of teachers.

He began his education career as a high school physical education teacher in Minnesota for 10 years, while also officiating. His wife is also a teacher.

“I think the expectations for teachers have been a lot more challenging. Going to school in the morning, then teaching all day and working a game after school. It’s tough to take on officiating with everything else going on in the schools,” Nickleby said. “They get judged all day by being a teacher. Do they want to be judged again as an official later in the day?”

Teaching is a tough job that requires extra time outside of the work day, said Mike Kolness, superintendent of East Grand Forks Public Schools in northwest Minnesota. He is currently a high school and NCAA Division II women’s basketball official, highlighted by an Elite 8 appearance in 2014. He has officiated D-I basketball and also continues to assign high school games for his officials association.

“You need to have the right type of mindset in order to officiate, and I feel it is very difficult to put in 15-plus-hour days when teaching and officiating,” Kolness said. “Dealing with fans, coaches and player behavior has definitely hurt in that area. I also feel teachers have found other ways to make extra income that may not require as many hours on the road with fewer challenges. There are so many industries that need extra

help, and their compensation level has increased quite a bit due to supply and demand.”

In Washington state, longtime teacher, coach and basketball official Steve Simonson has seen a steady decline in teachers entering the officiating ranks during his nearly 40-year education career.

“I’ll be honest, I think I am one of the old dinosaurs in doing all of these things (teaching, coaching and officiating) the whole time,” said Simonson, a social studies teacher from Cashmere High School in central Washington. “There just seems to be a lot fewer teachers getting into officiating and more responsibility put on them. It’s that time balance. The balance between work, family and time.”

Simonson manages to balance teaching three collegelevel courses to his high school students, coaching football and track, and serving as vice president of the Washington Officials Association. Simonson’s officiating resume includes a number of Washington

Interscholastic Athletic Association (WIAA) basketball tournament appearances as well as formerly officiating college basketball for about 15 years, including at the D-II level for six years.

He said people’s concerns about the reception they’ll receive on the fields and courts makes officiating a tougher sell.

“The No. 1 reason why people don’t want to officiate is they just don’t think they want to take the abuse of what is going on,” Simonson said.

He said it was critically important to work with new officials to mentor and guide them through the avocation’s challenges.

While the number of teachers has declined in the officiating ranks across the country, overall numbers of officials in neighboring Oregon have dropped significantly.

The number of officials has decreased by about 33 percent over the past 10 years, from 3,000 to just over 2,000 officials, according to Jack

In Michigan, recently retired educators from the 2021-22 school year wanting to join the officiating or coaching ranks after finishing their careers in the classroom were sidelined for at least nine months or faced having their pension earnings temporarily suspended.

In late July 2022, Michigan passed into law a bill that was intended to help with the nationwide teaching shortage. In the past, according to state pension regulations, educators who retired would have to wait 30 days before they could work for a state public school, but could not earn more than one-third of their previous salary if they wanted to retain their full pension.

Under new legislation, educators now have to wait at least nine consecutive months after their school termination date, but will have no restrictions on how much they can earn. The change was intended to attract more retirees back to the classroom with the incentive of higher pay, said state school leaders. According to Mark Uyl, executive director of the Michigan High School Athletic Association (MHSAA), extracurricular sports pay was not even part of the conversation.

“In discussions with school district personnel, we are being told there has never been a more difficult time for finding people than today," Uyl said. “All of us are searching

high and low to find coaches for athletic teams, and officials, referees and umpires to administer those games in an orderly and safe way.”

This nine-month waiting period for retiring teachers meant they were not eligible to officiate during the 202223 fall, winter and possibly spring sports seasons. If teachers chose to officiate or coach during this period, their full pension and health care benefits would not kick in until nine months after the culmination of their final season.

“Because of this current reality, we continue to be dumbfounded over the approval of Public Act 184,” Uyl said.

Folliard, executive director of the Oregon Athletic Officials Association (OAOA) and longtime Pac-12 football official for more than 30 years before retiring. He served as the referee and crew chief for the college football national championship game in 2007.

Folliard is trying to reverse the trend in his own state and re-establish a strong base of officials, including those involved in education.

“It’s great to have teachers, especially with their instructional-type skills, but very few teachers are officiating now,” Folliard said. “I’d be surprised if we have more than 100 teachers who are officials. I wish I had the answer of getting more teachers to officiate.”

Karen Beckmann, a high-ranking basketball and volleyball official and physical education teacher at Sauk Rapids-Rice High School in Minnesota, about an hour northwest of Minneapolis, said there is less time available during the day to complete the necessary work needed for teaching.

“More officials, teachers and coaches are stepping away from the field for numerous reasons,” said Beckmann, a former high school head volleyball coach. “Whether due to workload, parents, students or sportsmanship, many good people are leaving the profession to pursue other career options with less stress.”

A Georgia school official expressed concern in his inability to sway his staff to extend their day by working with student-athletes in either an officiating or coaching capacity.

“I would lump it all together and just say it’s been difficult to do the extra things, whether it be officiating or coaching,” said Steven Craft,

director of athletics for the Fulton County School System just outside Atlanta. “We’re fighting that as a whole, across the country, in trying to figure out where the coaches and officials are going to come from. We keep encouraging teachers to get into another setting and build those relationships outside of the classroom setting. Hopefully, we can change that in the future and attract more people. There is definitely a shortage of both. These days it’s hard to find teachers. Period.”

Fulton County schools even added a 25 percent pay supplement for multisport coaches for the 2022-23 school year, above and beyond their normal coaching pay, to help fill their county’s coaching vacancies at 16 high schools, Craft said.

Georgia is also trying to incentivize coaches to officiate. This past July, the GHSA Board of Trustees approved a policy allowing coaches to officiate the same sport in which they currently coach, with some restrictions, said Ernie Yarbrough, associate executive director and coordinator of officials for the GHSA. Coaches can’t officiate their own school or schools within their respective region.

Prior to that change, coaches were not allowed to officiate the same sport in

which they coached, Yarbrough said.

“We feel that will help fill some of the void created by COVID, at least at the subvarsity level where games are scheduled right after the conclusion of the school day,” Yarbrough said.