#26

APRIL – JUNE 2009

$3.00

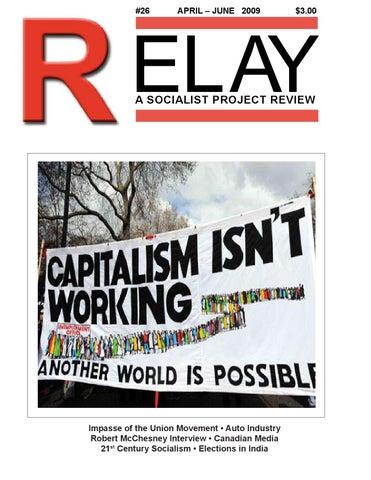

EL AY A SOCIALIST PROJECT REVIEW

Impasse of the Union Movement • Auto Industry Robert McChesney Interview • Canadian Media 21st Century Socialism • Elections in India

#26

APRIL – JUNE 2009

$3.00

EL AY A SOCIALIST PROJECT REVIEW

Impasse of the Union Movement • Auto Industry Robert McChesney Interview • Canadian Media 21st Century Socialism • Elections in India