victorian / planning / environmental / law / association / volume 116 October 22 revue · Planning as an economic enabler · The importance of people and place · Why you should be optimistic about our future · Strengthening our mental health and mindfulness in a post pandemic world · The crisis in growth area planning, and how to end it · Young Professional Group Masterclass Sessions · Paul Jerome award announced · Salutes to champions leaving the professions · Conference outcomes

The Business

People

VPELA Masterclass

compensation after the Brompton

person’s heritage is almost always another person’s property

Conference

Planning as an ‘economic enabler’ through the pandemic period

The importance of people and place

Why you should be optimistic about our future

Strengthening our mental health and mindfulness in a post pandemic world

Grassroot water activism in São Paulo, Brazil

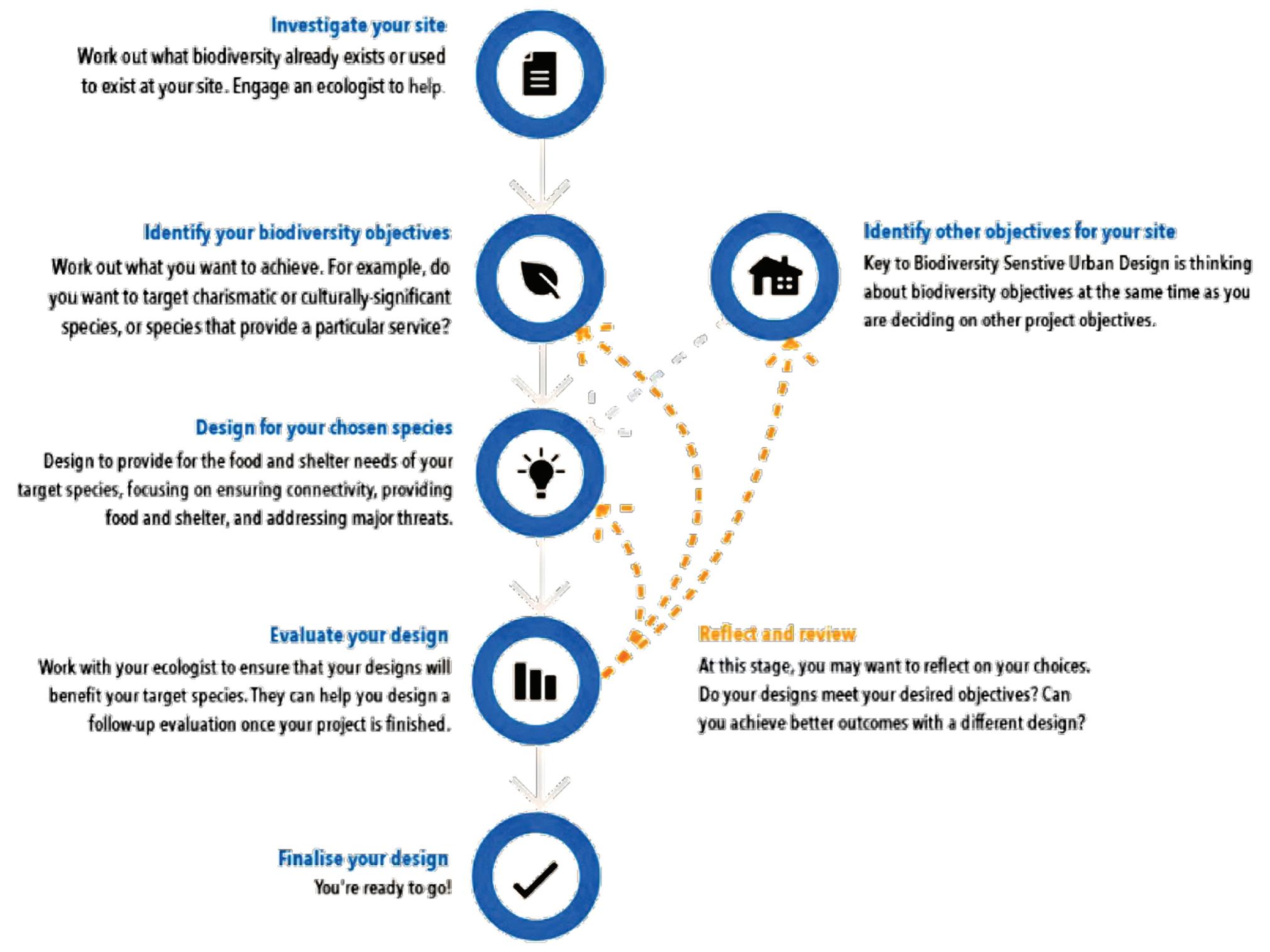

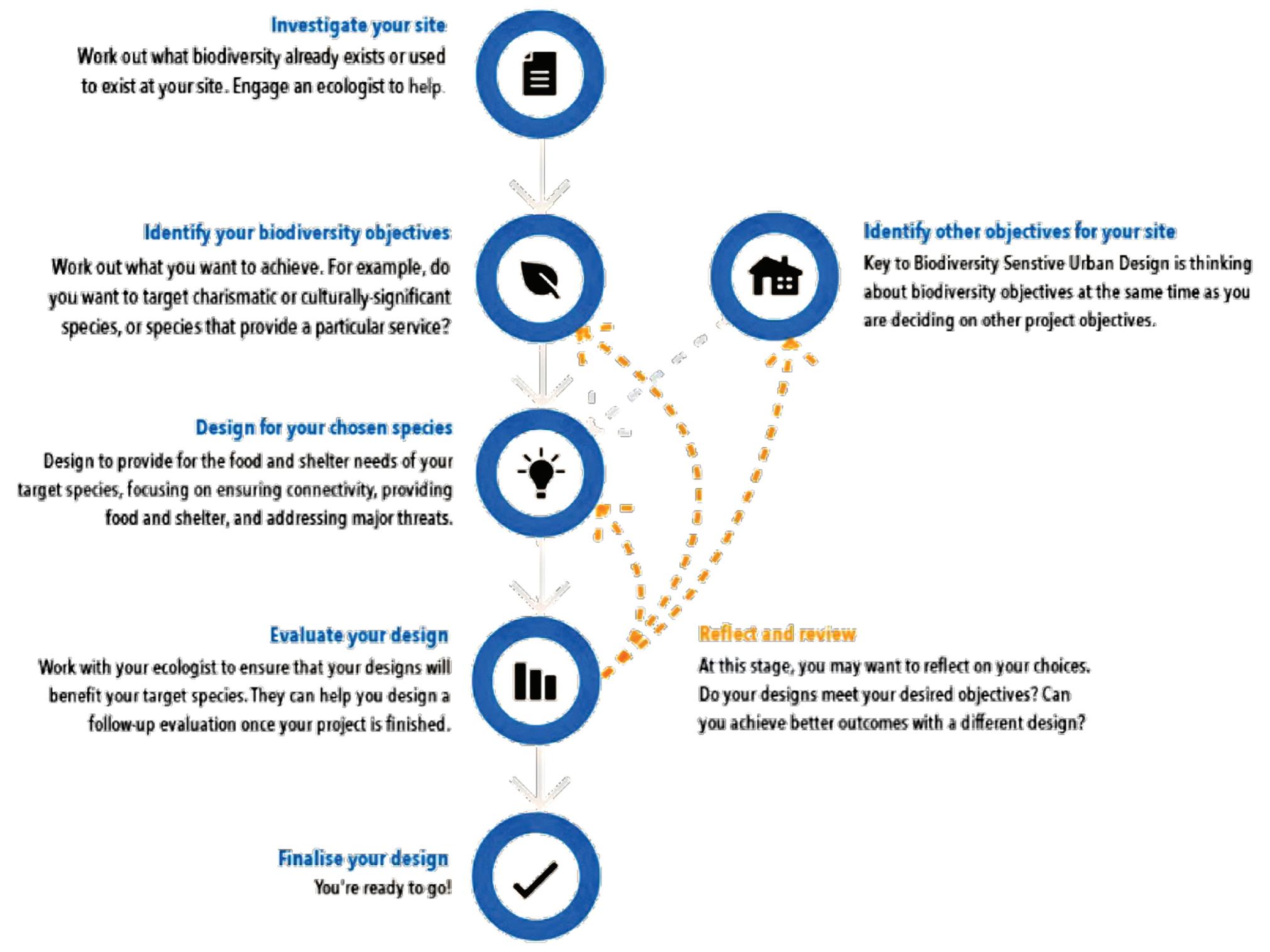

Using Biodiversity Sensitive Urban Design to coexist with Nature in Cities

Applying an intangible heritage framework to socio-spatial use of built form

Cover: Paul Jerome winner Chris Chesterfield, centre, VPELA president, Mark Sheppard,

Tim McBride-Burgess, (Contour, award sponsor),

Newsletter editor: Bernard McNamara

0418 326

bernard.mcnamara@bmda.com.au

9699

VPELA

Box 1291 Camberwell

admin@vpela.org.au

9813 2801

2 / VPELA Revue October 2022 Contents

Building in flood affected areas – why risk it? 34 The crisis in growth area planning, and how to end it 36 YPG

Sessions 39 Planning

Lodge decisions 41 One

43 President 3 Editorial Licence 4 Shadow Minister 6

Paul Jerome award; Chris Chesterfield 8 Au revoir Chris Canavan KC 9 The time has come Chris Wren KC 10 All the ‘Best’ Ian Pitt KC 12 Michael Barlow visionary planner retires from Urbis 13

14

17

21

27

30

31

33

left,

right.

M:

447 E:

T:

7025

PO

3124 www.vpela.org.au E:

T:

The President Spring is the time of plans and projects (Leo Tolstoy)

Welcome to the spring edition of Revue.

It’s been a busy few months at VPELA, highlighted by our first inperson conference for three years. Just like spring blossoms after winter, you were obviously raring to open up after the ravages of COVID because we had our biggest ever turnout, with over 300 delegates. Or perhaps it was because of the fantastic line-up of speakers, headlined by Catherine Freeman and including Tony Wood, Kerstin Thompson in conversation with Stuart Harrison, Sophie Renton, Dr Adrian Medhurst and Julian Lyngcoln.

Big thanks to our sponsors – particularly our ongoing Platinum Sponsor DELWP – and our amazing admin team and organising committee led by Anna Borthwick and Michael Deidun.

VPELA’s Paul Jerome Award, presented at the conference, recognises outstanding contribution to public service. I congratulate this year’s recipient, Chris Chesterfield, whose patient and persistent work over many decades to improve the way we manage stormwater has transformed our urban environments for the better.

Water

Speaking of stormwater, planning for flooding has become more pressing following catastrophic events in Victoria, NSW and Queensland this year, which raise the question of how to deal with existing and planned development in floodprone land. Two current planning scheme amendments promise to draw a ‘line in the sand’ (pun intended!) in relation to planning for sea level rise and increasing rainfall intensity.

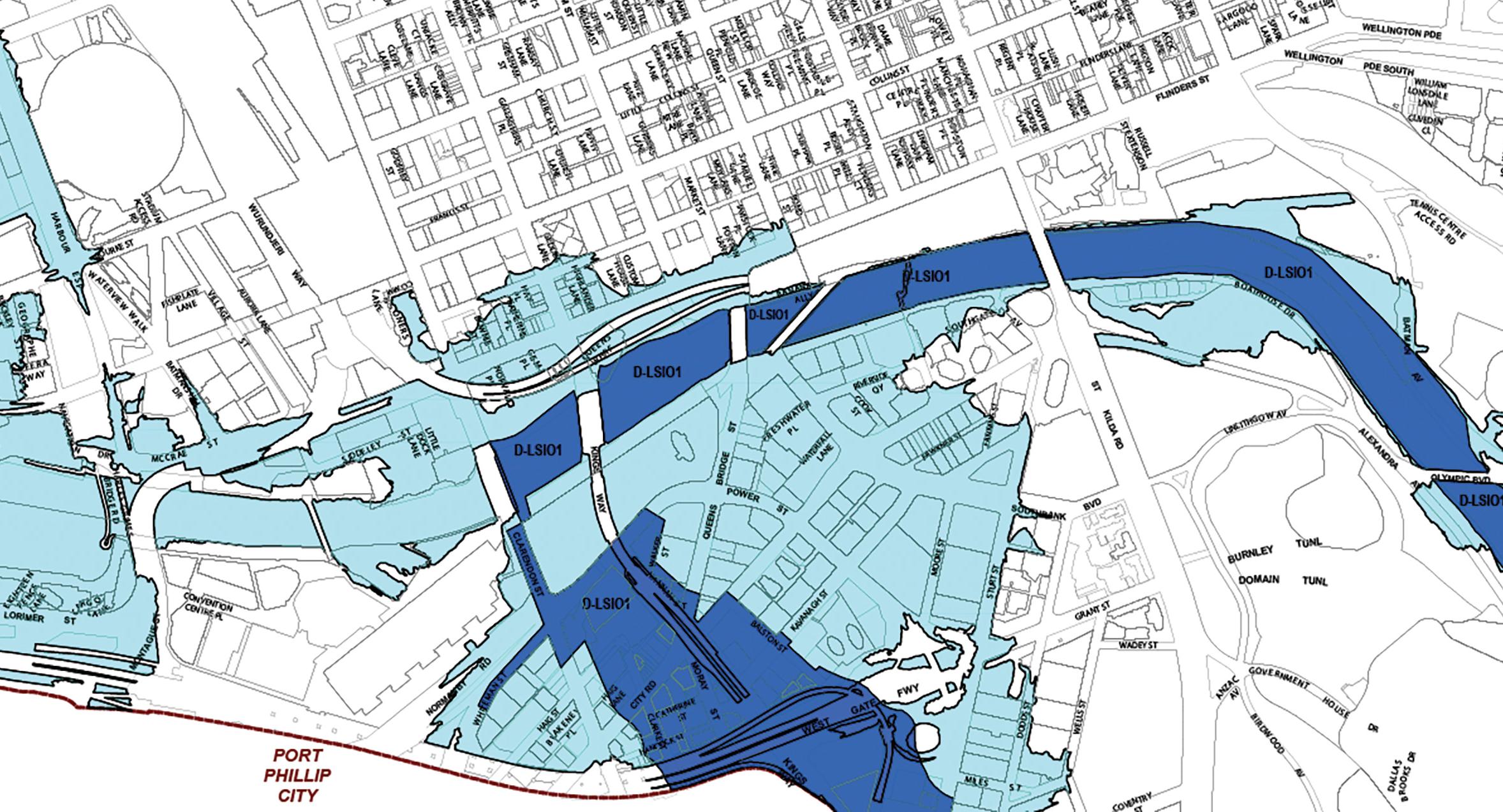

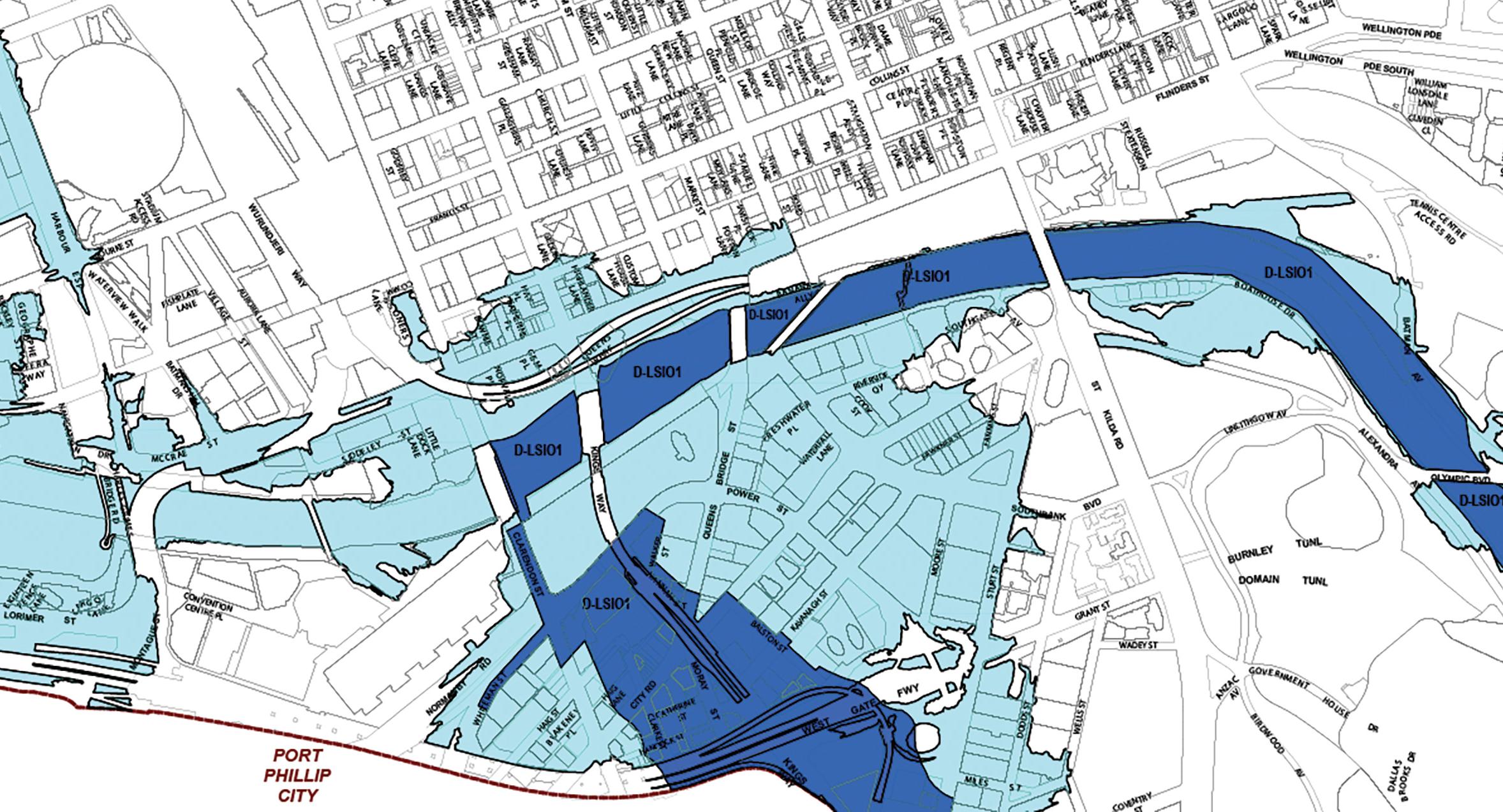

Moyne Amendment C69 explores the question of what extent of sea level rise to plan for in Port Fairy. Melbourne Amendment C384 proposes to increase the area of land affected by the SBO and LSIO to reflect increasing rainfall intensity. It also proposes to introduce as a reference document a ‘Good Design Guide’ for buildings in floodprone parts of key renewal areas, which seeks to ensure that flood responsive design still supports equitable and inviting urban environments. This highlights the need for integrated decisions in established urban areas that balance the need to minimise flood risks with urban design outcomes. We are planning a seminar in the New Year to explore this topic further.

The decisions ultimately made in relation to these Amendments promise to be significant inflection points in Victorian planning for climate change.

This edition’s Think Again article takes up the issue of what scale flood mitigation should be planned at. It poses the question ‘How should land subject to inundation perform in relation to its buildings?’ rather than ‘How should a building perform in land subject to inundation?’.

Wind

Mark Sheppard, Principal, kinetica

From the risks of rain to the potential of wind, a topic which has featured prominently in our winter webinar season.

We learnt that Australia has the potential to be a global offshore wind superpower, but there are major constraints to be tackled before we can get there – not least, the lack of supporting infrastructure and industry. Offshore wind farms are also supported by the Bald Hills Wind Farm VCAT decision, discussed at our Red Dot Decisions event, which highlights concerns about wind farms’ impacts on nearby residents. This is a critical topic that needs thorough investigation to ensure we can capitalise on the enormous potential of carbon-free energy.

Our panoply of webinar topics also included the opportunities and challenges of developing former quarries, and an update of all things PPV and VCAT, illustrating the diverse interests of our multi-disciplinary membership. If you missed any of our recent events (including the conference), the presentations are available on our website, along with recordings (for members only).

New governance

The Victorian Government has appointed a new Minister for Planning: Lizzie Blandthorn. Congratulations to Lizzie on her appointment to such an important role.

Speaking of Ministers, I’m looking forward to introducing you to the Shadow Minister for Planning, Ryan Smith, at a forthcoming webinar. If you haven’t met Ryan before, log in to get to know him and his vision for planning in Victoria.

By the time you read this, it’s likely that the VPELA board election will be complete. Thank you to everyone who nominated and congratulations to the new board members: Lucy Eastoe, Arnold Bloch Leibler Damian Iles, Hansen Partnership Grant Logan, DELWP

Emily Porter S.C., Victorian Bar.

Thanks also to all of you who responded to our survey last month, which has provided a wealth of information to help us serve you better.

I look forward to seeing you all at our Christmas party on 13 December!

Mark Sheppard is President of VPELA and a Principal at kinetica

VPELA Revue October 2022 / 3

Editorial licence

Greetings as we head into no mask territory and a somewhat return to normal. Now quadruple-vaxed and office normal, we move into the end of 2022 and an election in November.

In the shadow of the YPG

I am still in recovery mode after having been shown up by the YPG in its ‘super-good edition of the VPELA Revue in June 2022. Well done to Jack Chiodo, Isobel Viscovi, Emily Mignot, and others for their work.

That, and other activities from the YPG, indicate that VPELA is renewing and strengthening. The humorous and informative Work from Home/Office debate at the Conference illustrates my view.

Conference

Wow , we actually had an in-person conference in Lorne at the start of September. Well done to the Conference organising Committee led by my friend and former BMDA staffer, Anna Borthwick.

There was an energy across the 300 plus delegates. We explored the environmental and professional topics with speakers including Tony Wood, Stuart Harrison, Julian Lyncoln, but also the personal with Cathy Freeman and Adrian Medhurst (breathe and release!)

And lots of fun along the way. This edition of the Revue provides an abridged version of a number of the presentations. These include the new researchnew voices contributions of the RMIT Phd students. Hearing these new voices was a good initiative. A test of a conference/ seminar is to ask yourself whether you are coming away with some new thinking. Conference gets a tick.

Metropolitan Planning as a political football

As a member of the Victorian Government’s Plan Melbourne Ministerial Advisory Committee in the 2013—2016 period (i.e., under Minister for Planning Guy and then reformed under Minister for Planning Wynne), out primary objective was to think about Melbourne as a city, long term.

The objectives included creating an environment that would foster new age skills and businesses to sustain and grow Melbourne as a world city. The initiatives included the National Employment and Innovation Clusters, at Parkville, Monash, La Trobe-Austen and others. We recommended a vision which we hoped would be acceptable to all sides of politics, allowing for long term planning policies and investment confidence; both public and private.

One of the frustrations we experienced was the absence of clear transport plans from the government department. Phrases provided by staff such as ‘node-agnostic modes of travel’ are not much help when one is trying to understand and establish where and how opportunities might be encouraged and connected, respectively.

The Advisory Committee was a fan of Metro 1, and Metro 2 (now thankfully back on the agenda), the east west freeway link,(abandoned),extensions to tram routes and the introduction of high capacity/high frequency Smartbus services to allow people to access services, employment clusters and regional centres. In Melbourne, unlike Sydney, bus services have been a neglected resource.

No suggestion was ever provided to the Committee on a suburban rail link. That first surfaced in late November 2018. To my knowledge there was no input from Infrastructure Victoria. I acknowledge the State Government’s authority to introduce a project without requiring broad scale departmental consultation.

Putting the huge billions of dollars involved (and the various and conflicting business case forecasts) to one side, the situation where the project has become an election issue is a disappointing occurrence.

Personally, I have always questioned why more transport investment should be focussed on the eastern side of Melbourne when the western side of Melbourne is under-provided with rail services. The airport rail link will redress a part of that challenge.

Wither the PPV/Independent Advisory Committee process?

First, a declaration that I provided expert town planning evidence for a party before the Bellarine Peninsula Distinctive Areas and Landscape Assessment. Advisory Committee,

On 6 October, the Premier announced that the Minister for Planning had approved the Bellarine DALs with permanent settlement boundaries around towns. The Minister did so after having the Advisory Committee report in July.

But the Advisory Committee report did not recommend approval. Instead, it criticised (my word) the authorities for the poor level of investigation. It concluded that the authorities had by and large, simply used the old planning scheme town settlement boundaries to become the Permanent Settlement Boundaries without doing the necessary work to meet the DALS criteria. The Advisory Committee effectively handed the DELWP and Greater Geelong CC a massive ‘Fail’ and recommended resubmission. This was no ‘on balance’ call.

Not so, said the Minister and the faceless bureaucrats passing the boundaries into law.

4 / VPELA Revue October 2022

Bernard McNamara Editor and Director, BMDA Development Advisory

OK, Ministers can make unilateral decisions about settlement boundaries and other matters. But why the farce? Many community groups and landowners, in good faith, invested in the preparation of serious and beneficial studies that in most cases identified the inadequacies of the background work and supporting studies. They did this, honouring the independence and high regard that Planning Panels Victoria holds and deserves.

Why waste months of time and resources, and devalue the role of PPV? A bit close to an election maybe? An echo of Spring Creek, Torquay? And every time this occurs, it chips away at the commitment of the PPV members, making him/her ask… “Is what I am assessing going to matter?” A black day for planning assessment independence.

Process or Outcome?

My turn for a grumble. Accepting that plenty is happening, and we all feel a bit under resourced, but we can do better. Acknowledgements to Julian Lyngcoln and team for reducing the time that the Minister(DELWP) is taking to authorise and approve planning scheme amendments and all the expended approvals under Cl 52 everything.

But seriously,… Should a sign in a shopping centre be notified to 180 residents (no objection received)? Should a minor change to endorsed plans take months to be reviewed? Should the RFI button be pushed, probably before an application is inspected?

My thesis is that our systems are drowning us. You can be assure that the planners and authorities which created the Hoddle Grid, the streets of Camberwell, the rail lines to Frankston and the Great Ocean Road, did not spend years in assessments etc. Are they perfect? No, but we have embraced them and built on them.

As development assessment professionals , we are in part guilty within the process game. I don’t have an answer except to say that in a simpler world there was a place called the Planning Counter in local governments where plenty of items were sorted out quickly. Now we find that often a planner within an authority will not pick up a phone, requiring everything by email, controlling the process.

My first suggestion is that the outcome and its impacts (positive and negative) be understood at the outset, before the process buttons are pushed. If planning educators continue to see the profession as a regulator, rather than see it as a creator/builder on ideas, then we will continue for assessments to go slower and slower. As Anna Cronin found in her planning and building regulation review, this all comes at a cost to you and me. Did you read the Spanish infrastructure CEO who identified that project construction costs in Australia are twice as much and much slower in Australia than in Spain.(?)

Notable retirements

We are witnessing a ‘change of the guard’ of venerable proportions. This edition carries tributes to three of our leading QCs, (now KCs) from within the planning and environment jurisdiction. Chris Canavan, Chris Wren and Ian Pitt are passing the batons after decades of contributions. All have been active and generous VPELA members. I have personally worked with (and have been cross-examined by all over years.) My personal tribute as well.

And not forgetting the humble town planner! Michael Barlow, esteemed founder and director at Urbis is retiring after a stellar career.

Adios

This will be my last edition of the VPELA Revue. I assumed the editorial role at the start of 2015, giving me 7 years in this role, after years on the VPELA Board. Time for renewal. My thanks to Tamar Brezzi and the Board for entrusting me with this role. And, my great thanks to Jane Power, Grace Hamilton, and Katherine Yeo at the VPELA office for their support and guidance.

One fun comment to finish. Over the years, at the end of each column, I always requested feedback, but almost never got any. So, I concluded,…. people mustn’t read my column (sigh). But, in one edition, I wrote something that was not correct. Well,… people jumped out of trees! …..The lot of the editor!… Cheers and Thanks

Bernard McNamara e: Bernard.mcnamara@bmda.com.au

Mr Ian Pitt KC

Pivotal and key to Best Hooper’s rich history dating back to 1886 is the contribution of our Mr Ian Pitt KC, who remains actively involved with our firm.

Ian joined Best Hooper in 1966 and, over the years, has been recognised as pre-eminent lawyer and a respected leader in our industry. In 2002, Ian was appointed silk, making him only the fourth solicitor advocate to be appointed as either Queens Counsel or Senior Counsel in Victoria. This significant honour and recognition in the legal industry is testament to Ian’s advocacy skills and dedication to jurisdiction.

On behalf of the entire Best Hooper team, we take this opportunity to thank Ian for his outstanding 56 years of service to the planning, environment and development industry of Victoria.

Ian’s legacy is the next generation from Best Hooper who continue to maintain the high standard set by Mr Pitt KC with quality legal skills, tenacity, mentoring and measured temperament, all attributes that Ian has fostered.

VPELA Revue October 2022 / 5

Shadow Minister

Confidence, probity and integrity: Trust in our planning system

Hon Ryan Smith MP, Victorian Shadow Minister for Planning, Finance and Heritage

Hon Ryan Smith MP, Victorian Shadow Minister for Planning, Finance and Heritage

The newly appointed Minister for Planning, Lizzie Blandthorn, exemplifies the fractured and underhanded nature of this Government’s attitude towards planning.

Those plans sitting on the previous Minister’s desk, gathering dust – remember those? File them away because the new Minister’s hands are tied on the matter.

Confidence: the feeling or belief that one can have faith in or rely on someone or something.

Example – “we had every confidence in the Government”

Under the new arrangements for the Planning Minister and her staff, major projects requiring ministerial approval will be delayed, or potentially prevented from even beginning. There is a lack of logic and practicality in the government’s approach, and with it, a wavering faith that the planning system in Victoria will ever improve.

The Minister is obligated to exclude herself from any planning decisions that involve her brother’s firm, Hawker Britton. There will be no contact between the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning and Hawker Britton. The alternate Minister and their office will also not have any contact with Hawker Britton.

So who will?

Hawker Britton represents some of Victoria’s largest infrastructure project proponents and advocates. Projects which impact the lives of Victorians and pose major challenges to the planning system as a whole. If we are prevented from relying on the government to make the important decisions, then who can we rely on?

Projects like the West Gate Tunnel, which are already behind schedule and well over budget, will likely be delayed even further

given the supposed separation of the Minister and lobbying firm. How can Victorians have confidence in the government to deliver on projects if no one is seemingly allowed to make a decision? How can Victorians have confidence that planning decisions will be made swiftly and competently so as to ensure no further inconvenience is posed? How can we have any confidence at all with an impractical arrangement that will only slow things down?

We can’t.

Probity: the quality of having strong moral principles; honesty and decency.

Example – “Their probity is questionable when conducting business” Australian Super. The largest Australian superannuation and pension fund is waiting for a ministerial decision regarding its proposal to redevelop Kingswood Golf Club. A controversial project that residents of Melbourne’s south-east strongly oppose. The heated dispute between residents and developer is one of the many projects on the Minister’s conflict-of-interest list. Even if the Minister does not directly decide applications from Hawker Britton’s clients, the staff in her office and her department will be aware when an application involves the boss’ brother.

It is an impossible task to reconcile a popularly elected legislator’s duty with that of a lobby firm. Two opposing entities that represent vastly different interests and moral codes. One is accountable to the people. And that one is charged with the responsibility of serving the Victorian people with transparency and decency. Do not forget that.

How can the Minister demonstrate probity in planning if they are already the subject of such potential large-scale conflict-ofinterest with barely even a day in the role?

Integrity: the state of being whole and undivided or the quality of being honest and having strong moral principles

6 / VPELA Revue October 2022

Example – “It is expected that decisions are made with integrity”

Unfortunately, no planning decision going forward under this government will truly be free of doubt. The integrity concerns raised have been met with a clear lack of governance and leadership which means that projects that require decisions won’t get one.

These blurred lines of morality have been clearly felt throughout the industry. Since Bladthorn’s appointment, a number of those in the planning and construction sector have asked to be removed from Hawker Britton’s list of clients.

Stephen Charles, a member of the Centre for Public Integrity, monumentally understated the situation by describing the appointment of the planning ministry an “unfortunate one”.

The question of integrity remains.

Remember this November

For eight years planning, development and progression have suffered under this government. Resources are stretched. Roads are in need of repair. Population growth and the accompanying infrastructure demands have not been met.

Reflecting on these years, it is important that we can see some hope in our futures, and progress for our state. To do this, we must be able to trust our planning system.

Because without confidence, probity and integrity acting as the guiding principles for the government of the day, then our government has truly failed.

What we need is transparency and certainty. What we need is integrity and probity.

Under the current appointment, we have none of these.

STOP PRESS

2022 BOARD ELECTION RESULTS

VPELA would like to congratulate sitting board members Tim McBride-Burgess and Carlo Morello who were successfully returned in our recent election.

Warm congratulations to Lucy Eastoe, Arnold Bloch Leibler, Damian Iles, Hansen Partnership, Grant Logan, DELWP and Emily Porter S.C., Victorian Bar, who were also elected and joined the board in October.

A full profile of our new members will be included in the March 2023 Revue.

VPELA Revue October 2022 / 7

…continues next page

People

The Paul Jerome Award Citation for Chris Chesterfield

This citation was prepared by Helen Gibson AM and David Rae. The full nomination can be found on our website at https://www.vpela.org.au/documents/item/674

At a time when climate change is guiding the decisions and actions of the community through to federal leaders, the ability to work collaboratively with many different stakeholders to bring about change is more crucial than ever.

The winner of this year’s Paul Jerome award is known for their ability to facilitate constructive conversations, building trusted relationships in order to effect change across many levels of government that have changed the way our suburbs are designed, our streetscapes are managed and our resources planned for.

The initiative and leadership of this year’s recipient has played an enduring and outstanding role in fundamentally changing the way stormwater and waterways are planned for and managed in Victoria – across legislation, policy, practice, research, communication and engagement. The legacy of their work underpins our whole approach to the sustainable development of cities, in Victoria and nationally.

They have also led the way in bringing recognition and acknowledgement of First Nations People to the way waterways are managed. They brought rightsholders of Country to the Victorian Parliament to ensure that the way we plan, manage and engage respects cultural values and knowledge. This work has set a benchmark for engagement with Traditional Owner groups, recognition of rights and pathways for collaborative policy making.

Our recipient’s work on improving the way stormwater is managed began some 30 years ago with the formation of the Melbourne Stormwater Committee. This led to a new approach to become known as Water Sensitive Urban Design, which sought to improve the health and vigour of urban waterways and realise their potential to enhance the overall environmental quality of urban settlements, and which was in complete contrast to the then conventional engineering solution. The resulting Urban Stormwater Best Practice Guidelines were incorporated into State Policy. This kicked off an era of capacity building to produce tools and programs to support the transition of WSUD into policy and into practice.

The work of the Stormwater Committee directly led to a profound change in the way stormwater is managed, through:

· the EPA Victorian Stormwater Action Program,

· the Clearwater capacity-building Program which has been recognised by the United Nations,

· multiple publications showcasing the transition in stormwater management practice,

· the development of a wide range of new tools, policies and statutory controls, including the Integrated Water Management Framework for Victoria, and

· the facilitation of a wider approach to water management which achieved recognition and a much deeper engagement with Traditional Owners.

Most recently, this work led to the introduction of the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017 and the establishment of the Birrarung Council where the recipient was appointed as the inaugural Chair. Their leadership has again seen this Council make major strides in its development of a long term physical and cultural management plan for Melbourne’s key river. It leads the way for respectful and effective engagement and integration of cultural values and knowledge in government policy.

This year’s Paul Jerome Award winner has a remarkable reputation – as a respected leader and change-maker, but also as a champion of new ideas and approaches and a mentor to emerging leaders. They have not only led significant change but have also mentored new generations of change makers which has ensured the legacy of their ideas and initiatives is embedded in policy, practice and across the culture of the organisations they have worked in and people they have worked with.

Like Paul Jerome, this year’s recipient is renowned for their creative thinking and their ability to navigate the politics and barriers to change. They share the same trait – unafraid of pursuing ideas that sit outside the comfort zone of politics and government for the betterment of the environment and communities.

Please congratulate the winner of the 2022 Paul Jerome award, Chris Chesterfield.

8 / VPELA Revue October 2022

People “Au revoir” Chris Canavan KC

Kate Lyle, Victorian Bar

After 53 years of practise, Chris Canavan KC has decided to hang up his robes for the final time.

On behalf of the Planning Bar, I would like to mark the occasion of Chris’ retirement.

Chris was admitted to practise and signed the Bar Roll in May 1969. After 18 years as a preeminent planning junior, Chris took silk in 1987.

Over five decades at the Bar, Chris will be known to many within the VPELA community. He has been an active member of VPELA, regularly contributing to legal seminars and keenly attending functions. In 2005, Chris received the Richard J Evans Award in recognition of his contribution to planning.

Chris has been a leader of the Victorian Bar, and in particular, the Planning Bar for a generation. He has rightly earnt a place among the truly great advocates at the Bar. A consummate advocate, he was uncompromising in his advocacy, a ferocious cross examiner and fearless in the pursuit of his client’s cause.

Never one to rely too heavily on written submissions, Chris was a master of the art of oral advocacy. Jeremy Gobbo KC is correct to say that “Canavan has been for many of us an inspiration – a model of excellence in Court craft”.

Chris’ contribution to the planning jurisdiction, in the cases he has run, and won, and in the submissions he has made, has in many instances profoundly shaped the field of town planning and the law. His most important contribution to the town planning field, and the practise of advocates within it, has been the standard at which he has operated. Over many years he has been one of the benchmarks of excellence in advocacy and as such, an important contributor to the much needed rigour in planning decision making.

In leaving the Bar, Chris leaves behind many to which he has been a teacher, a confidant, a mentor and in the truest sense, a friend.

He has modelled true leadership at the Bar, and the responsibility that comes with it. In his retirement he leaves that as a legacy for the next generation.

On behalf of the Planning Bar and broader planning community, Chris we wish you well in your retirement. You leave behind big shoes to fill.

Kate practises principally in planning and environment law. Prior to joining the Bar, Kate was a solicitor at Maddocks and most recently Kate was a Senior Adviser to the Minister for Planning.

Hansen Partnership LVIA Team

Our dedicated Landscape & Visual Impact Assessment (LVIA) team is highly skilled in assessing the impacts of major infrastructure projects. We recently assessed Star of the South, Australia’s first offshore wind project, which will provide renewable energy powering around 1.2 million homes.

Contact Steve Schutt, Director for more information: sschutt@hansenpartnership.com.au

Urban Planning I Urban Design I Landscape Architecture

VPELA Revue October 2022 / 9

Serena Armstrong, Victorian Bar

The time has come, Chris Wren KC said

Never shy of an apt quote, some recall Chris Wren KC lapsing into song during submissions. It was therefore with trademark style that Chris announced his retirement after 47 years at the bar. Those who received his email missive, appreciated it commenced with his typical humour, warmth, theatricality and wit by riffing on Lewis Carroll:

“The time has come”, the Walrus said, “to talk of many things: Of days with time to relaxOf a phone that never ringsAnd whilst I haven’t quite lost the plot –I’m taking to the wings.” 1

Without doubt, those who know Chris remark on his loyalty and generosity. He is the consummate gentleman, courteous and calm yet never shy to fire up when it is of benefit to his case. He is a fierce fighter but level headed, provided the argument does not concern his beloved ‘Pies. The strength of his loyalty to his friends is surpassed only by his devotion to his family.

In the words of Stuart Morris KC, “universally you will be told this man is a man of integrity, a man with a strong commitment to the public good, a man who has been a forceful advocate for his clients, and a man who has been a great friend of planning law in Victoria.”

Chris is known to work relentlessly in each of his cases, doing the utmost for his clients. As Justice Osborn aptly describes, “Chris engages deeply with his cases, honing in on the points that matter, asking pertinent questions, listening intently to the answers and reading the bench.” He reflects that Chris is a leader of the jurisdiction, commenting that his body of work has been significant.

Chris was born in 1950, growing up in Kew and was educated at Xavier. After finishing school he resided at Newman College. It was there that his love of wine blossomed. He recalls engaging with his fellow students in developing a thorough understanding of big, bold reds.

Despite claiming to have spent “far too much time at the Clyde and not enough at the law library”, Chris excelled in his Bar Roll studies and upon completion commenced articles at Corrs. He was admitted to the legal profession in 1974, signing the bar roll 15 months later on 28 August 1975.

He read with John (Jack) Winneke, a formidable intellect whose expertise included town planning and whose judgments are well known from his time as President of the Court of Appeal (1995-2005). Winneke sparked Chris’ love of planning, opening it up as a “fascinating, entertaining and creative” profession. His entre to the planning bar was no doubt further assisted by taking chambers with Robert Osborn KC and Michael Wright KC. He had the good fortune to work with them, as well as Chris Canavan KC, early in his career.

Chris’ early years at the bar were occupied by a typically broad mix of matters. In addition to planning, he was briefed for a range of criminal, personal injuries and workers compensation hearings. But it was planning law that Chris truly loved and as his experience and reputation grew he focused on planning, land valuation, local government and liquor licensing law.

In 1989-1990 he was a member of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, hearing matters to clear the backlog of planning cases plaguing the government. Shortly afterwards he authored the Wren Report” into the Planning Appeals System Review. He wrote the report working out of the Attorney General’s office during the period of Andrew McCutcheon, who was an architect by training and went on to become the Planning Minister from 1990-1992. McCutcheon was also a founding winemaker of Ten Minutes By Tractor, so no doubt there was much talk of pinot and Mornington Peninsula viticulture practices during that period.

Chris was a champion of VPELA and believed deeply in Barber’s vision of a multidisciplinary organisation where people could network and share ideas. He served as its Vice President from 2004 to 2010 and in 2012 was awarded the Richard J Evans Fellowship. He was also an active member of the Law Institute Planning and Environmental Law Committee.

10 / VPELA Revue October 2022

People

Penny and Chris Wren.

Chris was always generous in the time he spent helping develop the careers of young barristers, including his readers Nick Tweedie, Sarah Porritt, David O’Brien and Joanne Lardner. In 2005 his long and outstanding contribution to law, particularly planning law, was recognised through his appointment as Queens Counsel.

Chris is known for giving his complete focus and energy to each of his cases. This is reflected in his response when I invited him to reflect on his greatest career achievements. He replied: “Every case is so important to the individual client, I don’t really differentiate them. You want your advocate to be totally focused on your case and nothing else. I tried to do that.”

Nonetheless, there are certain matters that warrant mention, including his role in the Inquiry into Nillumbik Council (1998), Basslink (2002), and as ‘Counsel assisting’ in a number of major EES and Advisory Committee matters including the Victorian Desalination Plant (2008) and the Logical Inclusions Advisory Committee (2011).

No chronicle of his achievements would be complete without mention of his commitment to the yearly surfing conferences in Indonesia, where, when not preoccupied by surfing with other lawyers and counsel, he is known to present papers about the laws of ‘dropping in on a wave’.

Last, but by no means least, Chris acknowledges his wife Penny, their four children and seven grandchildren as the most important part of his life. In the years to come, Chris’s time will be filled tending to his farm at Flinders, producing cool climate

wines and truffles, teaching the grandchildren to surf and travelling the world with Penny. Chris, we wish you all the best.

Serena Armstrong, is a barrister at the Victorian Bar specialising in planning, environment and heritage matters. She has had the pleasure of working with Chris Wren KC both as a solicitor and later as a junior barrister.

1 Those with a similar love of literature to Chris may recognise the opening three lines appear in Alice Through the Looking Glass

SAVE THE DATE

VPELA CHRISTMAS PARTY 13th December 6.00pm

Q Events by Metropolis 123 Queen Street, Melbourne

Bookings open soon!

Proudly sponsored by

VPELA Revue October 2022 / 11

People All the ‘Best’ Ian Pitt KC

I still vividly recall the telephone call I received, quite unexpectedly, from Mr Ian Pitt (not then KC). In his inimitable way and tone, he got straight to the point. Would I like to join him as a Partner at Best Hooper.

At that time, I was nearing the end of my 5 years sabbatical in the suburbs and the opportunity to join the preeminent planning lawyer was to use an often-repeated cliché “an offer too good to refuse”. Ian and I were soon joined by Dominic Scally and the planning team has organically grown to a point where today we have 14 lawyers, practicing exclusively in the planning jurisdiction.

The strength of the Best Hooper team is, in a very significant part, due to the stewardship, mentoring and the knowledge that Ian has imparted to all of us. One of his outstanding traits is that he always had time to talk to you, even if he was in the middle of doing something.

It was no surprise that in 2002 Ian was appointed silk, making him only the fourth solicitor advocate to be appointed as either Queens Counsel or Senior Counsel in Victoria. This significant honour was recognition by the legal industry of Ian’s outstanding advocacy skills and dedication to the jurisdiction.

John Cicero, Best Hooper

John Cicero, Best Hooper

Ian joined Best Hooper in 1966 and in his 60 years as a planning lawyer, many attempts were made to poach him from Best Hooper, but he remained loyal to the firm. Again, a testament to his character and dedication to the Best Hooper Team.

Ian has left a legacy of the highest standard of legal skills, tenacity, mentoring and measured temperament. I do not think I recall Ian departing from his measured temperament with any employee or with an opposing advocate or dare I say Tribunal Member in the heat of an argument or exchange. Those qualities have made him a remarkable contributor to Best Hooper and to the legal industry.

We will miss him, his dry sense of humour, his wit, his everpresent presence but his contribution to Best Hooper will remain for the current and future generations of planning lawyers. We wish Ian and his wife Helen a retiring and peaceful quieter life and thank you Ian for the irreplaceable contribution that you have made to Best Hooper for the present generation of lawyers and generations of lawyers to come.

John Cicero is a Partner at Best Hooper and has extensive experience in town planning law, Local Government law, environmental planning law, property development and liquor licensing.

reputation, leading expertise.

12 / VPELA Revue October 2022

Zina Teoh Senior Associate

Thy Nguyen Senior Associate

Jessica Orsman Senior Associate

Jeremy Wilson Senior Associate

Outstanding

Our Victorian Planning & Environment team is led by an award-winning group of partners and senior lawyers. We’re here for all your projects, no matter how big or small.

Briana Eastaugh Partner

Kristin Richardson Special Counsel

John Rantino Special Counsel

Terry Montebello Partner

Maria Marshall Partner

Michael Barlow, visionary planner retires from Urbis

After more than 40 years in private practice and local government, the profession is losing one of its truly great and visionary town planners, Michael Barlow, who is retiring to a quieter life in the country.

Michael’s career has followed a unique path, beginning as a young planner at the City of Doncaster before establishing himself in the early 80s as the City of Melbourne’s most talented appeals advocate (boasting an unbeaten record of 75 straight appeal wins in a row!). And when he wasn’t winning cases, he was working side by side with Rob Adams writing the 1985 Strategy Plan for Melbourne, which laid the foundations for the city’s renewal. It was perhaps through this work that Michael’s unparalleled understanding of cities and what makes them tick was first honed.

In 1985 Michael was persuaded by the eminent Terry Cocks to join him in growing what was then a small boutique valuation and planning practice, AT Cocks. Not long after Michael joined, Terry Cocks left the firm, and the remaining partners had their work cut out to reshape and rebuild the business under their own steam.

Over the next 15 years under Michael’s visionary business leadership, the firm was transformed into a nationally integrated multi-disciplinary practice, with offices in every major capital city and a presence in the Middle East. Urbis today is absolutely and

rescue the project, and then spent the next 12 months in Dubai leading an insanely difficult project during the working week and continuing his Managing Partner role for the Australian business on Saturdays and Sundays. He made an unparalleled leadership contribution to both roles throughout, and taught so many of us how great cities are made.

On returning to Melbourne, Michael once again rejoined the planning team within Urbis and picked up where he left off as one of the most authoritative, strategic, intellectual planners and expert witnesses in Australia. He was and remains the unanimous choice across the legal profession for all of the most complex, city shaping projects that come under examination in the planning system– from Melbourne Metro, to North East Link, to Suburban Rail Loop – all are projects where Michael’s ideas, evidence and thinking have been profoundly influential.

Indeed he has left a profound imprint on all who have been privileged to work for him and alongside him over decades. He has inspired generations of young professionals, both inside and outside Urbis, with his gentle powers of persuasion, his integrity and deep intellect. Personally, it has been the single greatest privilege of my career to work with, strategise and learn from Michael over my 20 years at Urbis.

In 2020 Michael’s outstanding contribution to the evolution

People

Michael Barlow

@ Contact: https://www.kinetica.net.au/ info@kinetica.net.au 03 9109 9400

Julia Bell Principal

Jane Witham Associate

David Ferris Junior Consultant

Kinetica congratulates our latest promotions and welcomes David Ferris to the team!

Conference

Planning as an ‘economic enabler’ through the pandemic period

This is an edited transcript from Julian Lyngcoln’ s conference presentation

Planning as an Economic Enabler, was actually a topic chosen a year ago in the midst of the pandemic. But a year on and three months out from a State election, plus, welcoming a new Planning Minister, it was a good time to reflect on the significant role that planning has played through the pandemic.

We’ve helped to keep industries like construction running, helped businesses to keep their doors open (and footpaths in many cases) and keep staff employed. Economic analysis shows the work that we did assisted development activity to the value of 18 and a half billion dollars at a time where the economy most needed it and generated 436 million of state gross value.

We like to talk about the things that planning delivers in terms of outcomes, sustainability, livability, good urban form, heritage. There was a real task for the government to use its planning functions to keep the economy going at a very difficult time. So, what did we achieve over that period, and what can we learn from that; to bring to our ‘business as usual’ mode? And as we move into the next phase, can we build on the efficiencies we implemented, without losing those outcomes that are so important?

Population and growth in the regions

Victoria continues to demonstrate each year that it’s a great place to live, but the pandemic had an impact on our population growth. For the very first time in a very long time, we saw a minor decrease in population compared to the previous year. With international borders reopening, we will return to our previous growth rates.

Our budget papers are projecting Victoria’s population growth rate to return to normal by ‘23, ‘24, at 1.6% per annum. Overseas migration ‘ticked’ back over into the positive again, in the first half of this year. This supports the projection that we’ll return to growth in the coming year.

From Melbourne, people moved out to our regions. We also saw huge demand in Melbourne’s growth areas, with record land sales, at least partly driven by pandemic-era of financial stimulus.

Population movement from Melbourne to the regions was strong before the pandemic and remains so now. In the year up to March ‘21, around 20,000 people moved from Melbourne to regional Victoria. Around 45% of that regional growth was concentrated in our regional cities of Geelong, Ballarat and Bendigo. Geelong grew by about 2.3%, Ballarat by 1.7% and Bendigo by 1.6%.

We also saw about 45% of our regional growth found in the periurban areas. So, Surf Coast Shire up over 4%, along with Bass

Julian Lyngcoln, Deputy Secretary, DELWP

Coast Shire, and Baw Baw. People headed for the coast during the pandemic. Dwelling approvals in regional cities remain at record levels of almost 10,000 in the 12 months to March ‘22, pretty similar to the previous 12 months. We also saw growth in our smaller centres with over 400 approvals in Wodonga, and 300 in Warrnambool.

Supporting Councils through regional planning hubs

In response to the growth in regional Victoria, DELWP provided direct support to councils through the regional planning hubs. That was a program that provided statutory and strategic planning support and resources to the 48 rural and regional councils, to help them plan and develop their municipalities.

We found that handing money over to regional councils wasn’t necessarily the answer. Many councils struggled even if they’ve got the cash, to get professional people in. Councils were looking for staff that could come in and do the work. Through this program we were able to support and provide professional development. The funding included accredited training courses and attendance at conferences.

We have assisted 43 of the 48 rural councils through the program. As of May, we’d received 129 requests from 43 councils. We have completed 13 statutory planning contracts and have another 10 underway. The statutory planning support team has assisted decision making on development applications with an estimated value of a hundred million dollars.

Development Facilitation Program (DFP)

The DFP applies generally across the State. This program is an outcome of the Building Victoria’s Recovery Taskforce. It was set up early in the pandemic to advise government on emergency response to the COVID pandemic. Following the success of a pilot program, the Minister for Planning established a development facilitation program within DELWP in late 2020, to support investment in jobs growth and to drive the economy.

Since 2020, 39 projects have been approved, worth over 4 billion dollars being brought forward. That will create almost 18,000 jobs, create a couple of thousand dwellings. Sixteen of those projects have now commenced construction. A key criterion for that program was for ‘shovel-ready’ projects.

The average approval time for projects under the DFP is about four months. This compares to an average of around 12 months were these projects required to go through a traditional permit process. As well as being shovel-ready projects, we were looking for projects that also delivered on some government policy outcomes as well. So, in sectors such as health, education, regional housing and employment, visitor economy, arts, and

14 / VPELA Revue October 2022

recreation. And, they had to meet minimum thresholds of value or scale.

A few examples are redevelopment of the Caulfield Racecourse, the Jewish Arts Quarter facility in Elsternwick, a major sports recreation facility in La Trobe University’s Bundoora campus, the Akenhead Center for Medical Discovery in Fitzroy, Warringal Private Hospital in Heidelberg and Australia’s first education and therapeutic support facility for children with autism and their families.

Approval pathways re-engineering

In addition, we have looked at policy and process reforms that we can make to really bring efficiency to the planning system, i.e., how we take time out of the processes?

We put new pathways in place for key infrastructure facilities, for transport projects, renewable energy projects and others. We have reduced timeframes for considering planning scheme amendments and we are facilitating apartment housing.

The State projects assessment pathway in Cl. 52.30 has facilitated ambulance stations, public sector aged care facilities, along with multiple transport projects. There is also a Local Government projects exemption in Cl.52.31 for councils, from planning requirements on things like upgrading parks, creating new sporting and community facilities and providing new libraries and town halls. And given how important housing is, we have a significant new assessment pathway to support the 5.3 billion dollar big housing build.

CELEBRATING HERITAGE FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

These changes have not been without contention, with the removal of third party appeal rights, particularly in regard to the social and affordable housing applications. There’s a lot of community concern, often at times, about being located close to these projects. Actually, the experience is that these have run reasonably smoothly. It is an incredibly important program. Victoria’s stock of social and affordable housing is pretty low. We’re probably heading towards that being about 3% of the overall stock on the trajectory we’re on, so it is a critical program. We are also working with the federal government as well, to see what can be done further.

We have new approvals pathways for non-government schools, and that’s had huge demand. Non-government schools play a large role in educating Victorian students, with over a third of all primary and secondary students now enrolled in independent schools in 2020. Population projections suggests that schools will need to accommodate more than 97,500 additional students by 2025. It is a big task to keep up with that population growth in terms of education facilities. Since those provisions were introduced, DELWP has approved 81 planning permits with a combined development value of 765 million.

New exemptions and pathways have also been introduced within the Victorian planning provisions. For major road and rail projects, for state transport projects, level crossings, state car parks for commuters, new tram depots, railway stations, and bike paths. We’ve also updated State planning policy for transport to support a more integrated transport system, including introduction of a new Transport Zone.

VPELA Revue October 2022 / 15

At Urbis, we shape cities and communities for a better future, while achieving the best heritage outcome for our communities.

We offer innovative, professional solutions to help you negotiate heritage frameworks for development, and understand the opportunities your heritage places offer.

State Library

of

Victoria

ID 1769158

History lives on when the buildings of the past shape the places of the future.

Carolynne Baker Director, Heritage carolynne.baker@urbis.com.au urbis.com.au

“

Renewable energy

The government has an incredibly ambitious target around renewable energy. The Minister for Planning became the decision maker for all new planning permit applications for large-scale electricity generation facilities. And that includes not just wind farms and solar farms and the like, but batteries, transmission lines, generation facilities, and things like thermal gas and coal. Previously, the Minister for Planning was only responsible for wind and solar. The changes that have been made will ensure that Victoria’s energy transition is appropriately coordinated. The government has granted over 1600 megawatts of wind power, 700 megawatts of solar power and 1500 megawatts of battery storage as a result. And that’s roughly enough power to power approximately 1.36 million homes.

The amendment process

We know that one of the biggest pain points for councils is the time it takes to get through planning scheme amendments. Our performance as a department, on amendments over the last few years, hasn’t been where it needed to be. We are committed to bring those timeframes down. Pleasingly, we have reduced the amount of time to authorize amendments by two thirds since 2020. This will have a big impact on reducing holding costs for landowners and increase certainty for councils. We’ve set about repositioning the department as the premier statutory planning team for amendments, with active case management using digital work and re-allocating resources.

Apartment design incentives

I want to talk a little bit about facilitating apartment housing. Accommodating population growth and the need to really do that in a smarter way rather than just sprawling out further and further out beyond the boundaries of the current suburbs. We have the Better Apartments Standard in place. We are now working on our Future Homes program, an extension on the Better Apartments program. It is looking to combine the aspirations of the design standards to deliver high quality livable and sustainable apartment design. We’ve been working in partnership with the Office of the Victorian Government Architect and have produced

four high quality apartment designs or blueprints that include gardens, energy efficiency, and adaptability.

Developers who purchase one of these high-quality designs will be rewarded by receiving access to new simplified planning pathways. That process could halve the usual planning timeframes while creating added planning certainty. The future home designs can be recreated and are scalable. We don’t want it to be too cookie cutter. The designs will need to be adapted to a site. All Future Home apartments will have high sustainability performance, seven and a half star rating, cross ventilation, high levels of daylight, family friendly circulation spaces for prams, and adaptability for changing needs.

Closing

This is a great time to reflect on the significant role that the planning industry has played in helping Victoria respond and recover from the pandemic, and the value that planning contributes to the state.

Moving to the next phase, Victoria’s recovery, we hope to build on the efficiencies we’ve implemented. DELWP will continue to focus on post-pandemic economic recovery, looking at the operation of Rescode, to improving heritage processes, further protecting the green wedges and Victoria’s Distinctive Areas and Landscapes. We will continue to focus on the environmentally sustainable design roadmap, waste and recycling, water, sustainable transport, energy, and climate, designing and implementing the new Victorian Planning Vic website for rollout in 2023, and expanding the Better Planning Approvals program to another 10 councils.

Come November with the State election, we stand ready to work with the incoming government; on what priorities they have to improve Victoria’s planning system and ensure it continues to deliver for all Victorians.

Julian Lyngcoln is Deputy Secretary in the Department of Environment Land, Water and Planning with nearly 20 years experience in State government. Julian is responsible for leading the State’s planning, building and heritage systems.

16 / VPELA Revue October 2022

Find out more at ecoresults.com.au Your ESD Consultants Energy | ESD | Daylight | WSUD Waste Management | JV3 | NatHERS

Conference

The importance of people and place

This is an edited transcript of the conversation between Stuart Harrison and Kerstin Thompson at the VPELA State Planning Conference

Stuart: What we want to do today is really try and talk a little bit around some of the key themes of place and people and how architects interact with the planning system as a whole.

This is a little walk I did a few weeks ago from the city to Fitzroy. It’s a rough walk kind of east, from the city through Carlton and then into Fitzroy. The first image is in the city opposite the Royal Exhibition Building site on Exhibition Street, is the new Sapphire by the Gardens project. It’s a collaboration between Fender Katsalidis and Cox Architecture, good large architectural practices. And I guess what this shows us is a very large project, residentially focused, notionally mixed use, activated podium, I guess in some ways it’s a sculptural version of what you might call the standard densification response in a city area where the planning scheme is loose and certainly encourages density.

In Melbourne, we’ve been through a collective experience, of highly densified streetscape towers, which increasingly continue to occur. And you can’t necessarily blame the previous government now, given we’re at the end of the second term of the current government. This scheme, Sapphire, was approved well within the first term of the current government. I’m sure it wasn’t easy getting it through and there was a taller version of this scheme, initially. It was, obviously, a ministerial direct referral large project, but it’s opposite a World Heritage Site, I guess, is the point I wanted to make. And so, in a very significant part of Melbourne, which is the grounds of Carlton Gardens, the scheme supports this activity, and I’m not saying it shouldn’t. But if we walk, as I did, up to Station Street, Carlton, where we did a project a few years ago, that’s buried in this middle shot, we see a highly protected streetscape, the sort of heritage overlay constraint which, to the frustration of many of us as architects, prevents densification occurring in places like this, where there is potential given the large width of streets. This middle slide maybe represents these opportunities to rethink how the planning system constrains things happening in this type of place.

Part of my walk was to continue over to Fitzroy, and I probably should talk about the image on the extreme right, which is a beautiful little BKK project finished a couple of years ago. I have no idea who designed this project, but I do recall it being built in the late 1990s. It’s a pre-cast concrete project. It was wildly disliked by Fitzroy locals at the time and I recall the term yuppie dog boxes being graffitied on the side of it quite largely, and that stayed there for some time. I think it was seen, probably by design professionals and concerned local residents, as the beginning of the end of society. But then you look back at it 20 or so years later and you go, “It’s actually pretty good. It’s probably got too many crossovers, but it’s got some relationship to the

street. It’s got shaded windows. Windows you can open more than 125 millimeters. It’s got vegetation growing on it and it’s three storeys. Actually, maybe that’s not such a bad form of urbanism.” And so, in contrast to Carlton, Fitzroy has now, for over 20 years, supported some reasonably good interventions.

The loose argument is that the planning scheme has supported some reasonable stuff, particularly in areas like Fitzroy that are not less subjected to the kind of restraints we see in that middle slide. That finishes my provocations, and I’m sure Kerstin’s also going to talk a little bit about Fitzroy, because it is a place dear to her heart where she’s worked and lived for many years

Kerstin: Thank you, Stuart. That has raised lots of good conversation pieces. The first of my three images is the Melbourne Holocaust Museum, which we’ve recently completed in Selwyn Street in Elsternwick. I put this up as part of a bigger question, why setbacks? It is an invitation for us to contemplate different sorts of ways in which we might relate heritage buildings or existing buildings with new buildings, and really as an urge for us to expand our repertoire for how we relate existing fabric with new fabric. I think we have been stuck in a very binary idea about either juxtaposition and massive differentiation of new and old or perhaps, a while back, straightforward imitation.

The other thing I want to challenge, which this building does, is this idea of heritage always having to trump the new. And by that I mean to urge us to move from the deferential model that new buildings must always be deferential to heritage and say, “Actually, what we want is equal quality for peer-to-peer rather than one being subservient to the other.” For us to stop being apologists, having a confidence in our current capacities to deliver buildings.

The next image in the middle, is the Broadmeadows Town Hall, which we worked on a few years ago with Hume council. This is to say that, look, there is no such thing as a site outside of heritage. I would say heritage is always a question. There’s nothing outside of space and time. Everything we do is responding to an existing set of conditions. The second point is that something may not have architectural merit, it may not be listed, which is the case in point with the Broadmeadows Town Hall, but it was of great value, social, cultural value to that community in all of its diversity.

So, its retention, its reuse, its recycling, and adaptation for now was really important, because it was a repository of community memories, events, debutante balls, car clubs, you name it, things that have happened there. And the loss of that would’ve been the loss or erasure of those memories. So even how we treated interior palettes, was to keep that link with the past through the architecture. It’s also a suggestion in our consideration of heritage, to understand the more performative aspects of

VPELA Revue October 2022 / 17

Kerstin Thompson

Stuart Harrison

attachments to place, not just a visual one about architectural styles. Finally, it represented the need for us to be resourceful and get better use out of what already exists before we start advocating for tearing things down and new buildings.

The last project is Kerr Street Housing. This is officially the longest standing project we’ve ever had in the office. I think it’s been going for close to 15 years, and I will say right now what is interesting about this project was at the time it had a heritage base, and we advocated to council to dump the usual default of a setback from the base and put the new form in the middle of the site. We said that’s not consistent with the morphology, the forms, of Fitzroy, there is no pattern of this approach, so from a site responsiveness point of view, it doesn’t make sense. It’s actually not site responsive. That was the first point. And secondly, that in adopting a perimeter and adopting zero setback, we got a courtyard in the middle, so mutual benefit for our future occupants and the neighbors next door.

It went before council because of the number of objections, but interestingly, this got through. This is not uncommon anymore, the zero setback, but at the time we like to think we set a precedent. Good design, what we try to practice every day, is our way of advocating and changing and setting new precedents and exemplars through the work that we do.

Stuart: I think it’s worth picking up on a couple of themes there. Maybe we’ll dive into the issue of elected heritage first. This is a term I’ve been using the last few years, and it comes out of experience of hanging around restoration people a little bit. But the Broadmeadows Town Hall is almost a defining project in this idea of elective heritage. To elaborate what that means, it’s where you choose, you elect, to keep a building whereas you could knock it down.

What is interesting about the Broadie Town Hall is there was an existing master plan for the center of Broadmeadows, and the Broadmeadows Town Hall had been demolished in that plan. A long time later, the council obviously came to a position around keeping the building, electing to keep it. By the time you got involved Kerstin, had that decision been made to keep it, or did you have to advocate for its retention?

Kerstin: A bit of everything, actually. But it’s fair to say that I think some councillors would have liked a new building, partly because they felt that this was a second rate, sixties, dated building. We saw its value as an interesting piece of suburban civic. But the thing that really clinched it was just a simple question of money, and impact, and value for money in reusing what we had. But it also seemed like it was the importance of keeping it, because of the attachments that the community had. So really it became a project with a lot of community support.

The thing that was also interesting was that it wasn’t formally listed in terms of any heritage overlay. We did have the freedom to do what we thought were the right moves for the building to reactivate it. And interestingly, when we received an award from the Heritage Jury for the institute, there was an awareness that the outcome was as strong as it was, perhaps because it hadn’t had an overlay which might have prevented some of the moves that they most respected.

Stuart: And just to elaborate, I think it’s what I call the benefits, the privileges of working in the elective heritage space is you can

still barrel things. We worked on the RMIT New Academic Street project buildings, which were not widely loved, and we wanted to treat them carefully, but we were able to knock enormous holes in them. And certainly, with Broadie, you really knocked the whole back of the building down, and there’s a great essay in all different kinds of conservation techniques going from the front to the back. I want to talk a little bit about this setback issue, because you’ve brought it up on really the other two slides.

Kerstin: I must say too, that’s a pre BADS one, and that was the other point I meant to make, which we can come to. When you walk through it now, the quality of those spaces, you think, “Gee, these feel so comfortable and it’s great. The proportions and the idiosyncrasies,” and then you realize it is pre BADS.

Stuart: I’m sure everyone in this room’s familiar with the BADS, and it’s an unfortunate acronym. I recall being involved in some of the stakeholder processes to set up apartment design guidelines equivalent to the well-trodden Sydney SEPP 65 ones. Do you think, Kerstin, that generally those apartment guidelines have been good at the stuff I was talking about before in terms of this theory of the tide lifting all the boats at the less designfocused end? Do you think it’s useful in that end or isn’t it?

Kerstin: I’m sure we’ve all heard people say this before, but it may lift up the bottom, but what it’s also doing is suppressing the top, and I think is dampening innovation, especially in housing diversity and choices. In the social housing work we’ve been doing, we’ve noticed some really interesting tensions in what certain sorts of regulations, like BADS, should be doing. It has effectively de-incentivized any innovation in the sorts of housing products you might be developing and at the level of the individual apartment layout, it’s very prescriptive. Kerr Street being pre that, I think shows a level of innovation, which we couldn’t adopt.

This question of proportion being mandated, I think, is really problematic in terms of building in sometimes slightly more flexible types of spaces. Or for instance, the idea of a second or a third bedroom you might design with a certain degree of openness or open ability to be a living space, to get that flex of how it might be used, for instance. Whereas under BADDS, that would have to be a full bedroom with direct access to natural light. And the proportion thing comes out of the distance from facade as well.

What you’re seeing is, at the level of the apartment design, is very prescriptive. And there is no incentive for people to vary from it, that’s the other thing, because it becomes a default minimum. But the other point is what it’s doing on an urban level in terms of the formation of our cityscapes. We are getting this pattern book of one typology stamped across our city. It’s also a loss of the variation you might get from suburb to suburb. And if there’s one thing we try to do in our work it’s to say that every building we do is an opportunity to speak of that place. When you have some of these sorts of highly prescriptive codes, I do think it is counter to that whole quest for site responsiveness that are supposedly embedded in these codes.

Stuart: We have been hearing about the renewed importance of the local. I think that’s something that, as architects, we are always looking for the specificity of how you embed that. I guess, by definition, planning schemes are trying to control things at a very broad level, although there are often local controls. How do

18 / VPELA Revue October 2022

you think you could get that specificity into a planning system, Kerstin, in terms of things like making a project of a place? You sit on design review panels in Victoria and have had projects go through that process. Is that a mechanism that could be used more broadly? Is it scalable? Could you opt out of the BADS and into design review at a local level?

Kerstin: I mean, it’s certainly an idea. Of course, these things always come to resourcing, and it’s the number one impediment to a more nuanced way of assessing the pros and cons of first principles thinking, if you like, around a proposal, and its relationship to place. But yes I certainly think that’s one way. I also do wonder what rules are useful. You get a very particular outcome, a very predictable outcome, and as I say, there’s no incentive to go beyond that unless you get an unusual client or developer who’s prepared to go above and beyond.

Stuart: Whereas if you would incentivize the design excellence pathway, you could then have floor area benefits for going through such a process, but it is an issue of resourcing. Because design review, for example, as one mechanism in design excellence takes a lot of people, and cost. You can charge for that model, and there are some jurisdictions that charge for it, and if there’s incentives, then developers will pay to go through that model.

I want to also touch on this issue of setbacks, which you’ve raised in a couple projects here. I was fortunate enough to have a guided tour of the Melbourne Holocaust Museum recently as part of Open House Melbourne’s open weekend. It was really interesting to learn that the facade, the original building had no heritage protection either. And I think, as a result, you were able to, again, work with it in a way that you wouldn’t be able to if it had had some heritage listing, certainly.

Kerstin: It was the original building previously known as the Jewish Holocaust Center. It was again of cultural significance as the beginnings of that center in Melbourne, and hence why we thought it was definitely worth retaining. And in fact, our position on it was to almost treat the heritage building like the original artifact of the museum, and well and truly embed it and integrate it with its new and future facility.

At a council level, the heritage advisor was clearly advocating for a substantial setback. We felt that apart from the fact that it really diminished an already very restricted building envelope because of recent residential development, the other issue was just the loss of the building’s presence as a civic building on the streetscape. Another thing that gets lost sometimes in these conversations is about bigness. The council was really keen to support this initiative, because of the education and programming and all sorts of possibilities of the museum. I think the small matter of a heritage setback was seen as a smaller problem in the greater merits of the project.

Stuart: I think what’s also really interesting about the museum is if you put a heritage lens on it, it transgresses so many kinds of rules, but is such a beautiful outcome. And just at the level of coloration, the building comes across as a white cube and under normal Burra Charter ways of thinking about things, you might go, “Well, the new bit, setback or no setback, might be a clearly different color”.

Kerstin: Absolutely. It used to be clear, black and white difference between new and old. And we would sledgehammer

architectures that slam dunked what was there before. And so really what we’ve been trying to do with our work over many years is get this interesting, more complex relationship, where there’s a resonance, there’s a connection, there’s a conversation, and it’s, perhaps, more subtle at times. It is quite an interesting intrigue for people to think where does this new and old begin and end? There are signs there if you look carefully. So even that change, I think, from the original permit, the clarification from the planning department, shouldn’t the new and the old be greater color difference. And that’s where we said, “Actually, this is about a unified response. All of these moments are being brought together in this proposal.”

Stuart: People is the other theme of this session. There has been a big focus over the last 10-20 years on both stakeholder engagement and user experience. As architects, putting yourself in the mind of people using the building seems like common sense but, to some architects, it’s still a revolutionary idea. How do you think that’s been useful in your own work, and how do you do that when you have the unknown client? The person you never meet, who’s going to move in, whether that’s in private, multi-res or social housing.

Kerstin: You touched on part of it, which I think is fundamental to making decent buildings, and that is for us to try very hard to put ourselves in the shoes of future users. They are both the occupants of the building that we know about, they’re the ones we can only speculate about, but there are also the people who are not formally the users of that building, but will pass by it, might pass through it, and so there’s a multitude of people and uses that we have to anticipate. I would say we need to be highly anticipatory too, understanding and anticipating of these other needs.

I often talk about the kind of ethics of design, and that is where ethics comes into it, which is about our responsibility to others and the making of buildings. I think in many spheres, we need to remind ourselves of the ethical component of what we do every day. It is really, really, important. In terms of our planning sphere, it’s a challenge to both be protective of current amenity and users, but also without precluding the benefits for future users, and that’s probably the big challenge with planning. The way in which we navigate those different users and their different needs, because I often describe architecture as the kind of meat in sandwich or the negotiator between these various competing interests, if you like. Ethics is about navigating competing interests.

Then the point is to have fairly clear intentions. There’s a lot of ways you might come up with a solution that meets those intentions, but you do need that clarity of what the building is doing, who it’s doing it for, how it’s doing it. And so, clarity of purpose, I think, is huge, because there are a lot of things to take us off course along the length of time it takes to make buildings. The idea of mutual benefit, which is something we talk a lot about, especially with private sector work, has a public impact. And so, you’re always thinking how can we do more than simply meet the brief itself and deliver some greater positive impact.

Stuart: I’d be interested to hear about some projects where you think that the planning scheme has worked quite well in supporting what you’ve proposed to do, and are there some projects where it has basically prevented something good from happening?

VPELA Revue October 2022 / 19

Kerstin: We recently finished a housing scheme in Balfe Park in Brunswick and Moreland had their own guidelines for multires as well. It was a case of where some of the regulations, if we applied them, we did think we would get a less than ideal outcome, but there was a way in which, for instance, one of the clauses around setbacks, primary, secondary frontages, enabled us to actually introduce a lane way through the site, which had this greater neighborhood benefit. So, one of our things is always to find the ways in which the codes can be pushed to deliver those sorts of extra benefits. Mutual benefits of both proposal and greater neighborhood.

Stuart: Assumedly, that project required an enormous amount of advocacy to get to that point.

Kerstin: It did. And it was an interesting one where we actually demonstrated that we could deliver a smaller footprint through some greater height, and the smaller footprint would enable this more porous and permeable site. The public lanes, for instance. As it turned out, we still delivered on the porous, and the lane ways, and the smaller footprint, but with a lower height. I think height was not the problem it’s just how well you manage it.

Stuart: So, height controls there weren’t that useful in terms of good outcome?

Kerstin: I think height controls are a real questionable device and it should be volume controls. The capacity to introduce negative space, or voids, which have this other greater benefit in civic scale and so forth, they’re the things that get knocked out when you are limited by height, because of land values, all of those things that we’re all aware of.

Stuart: I think that issue of getting that lane way through, it proves that all projects are urban design projects, really. We have time for a couple of questions.

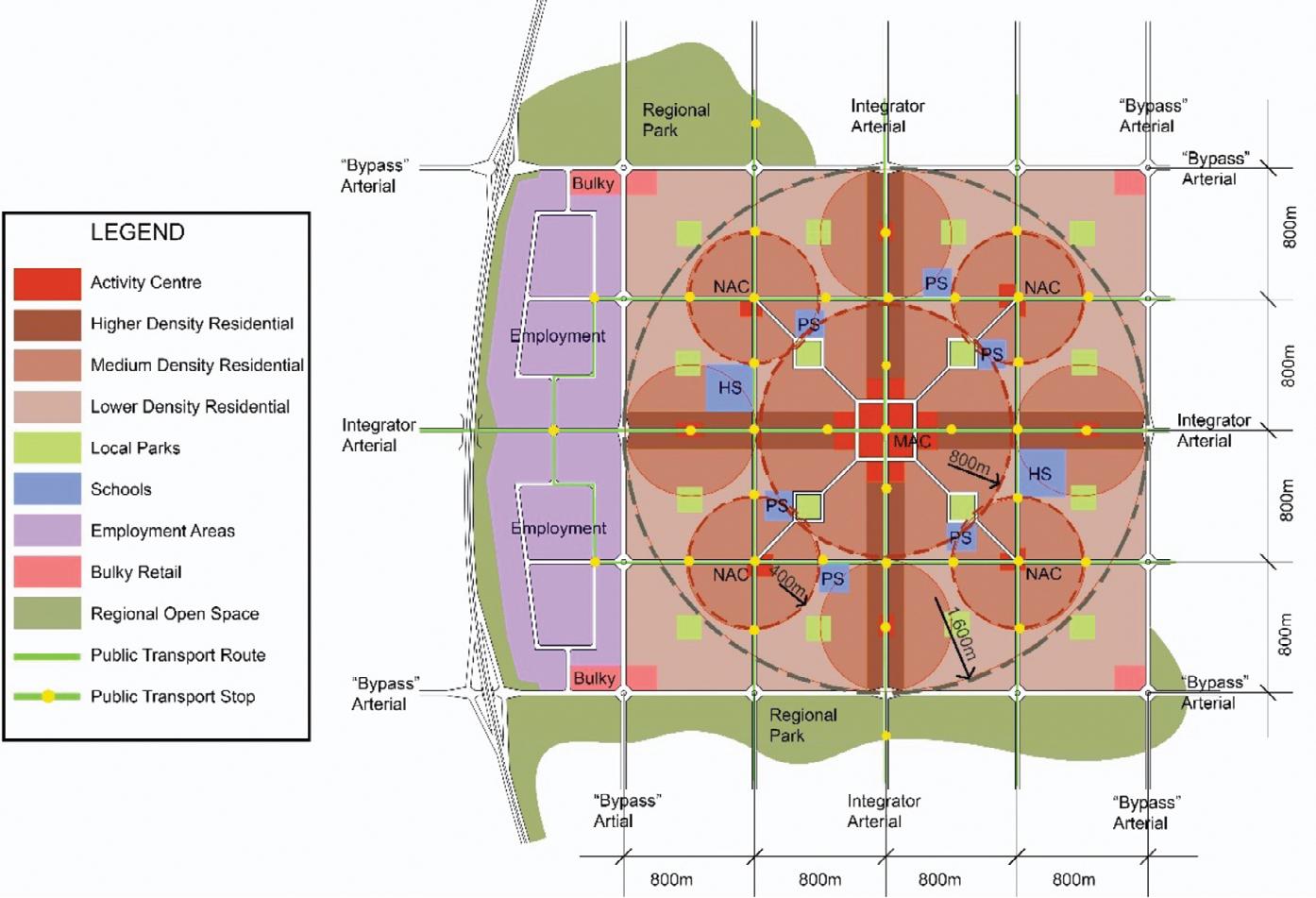

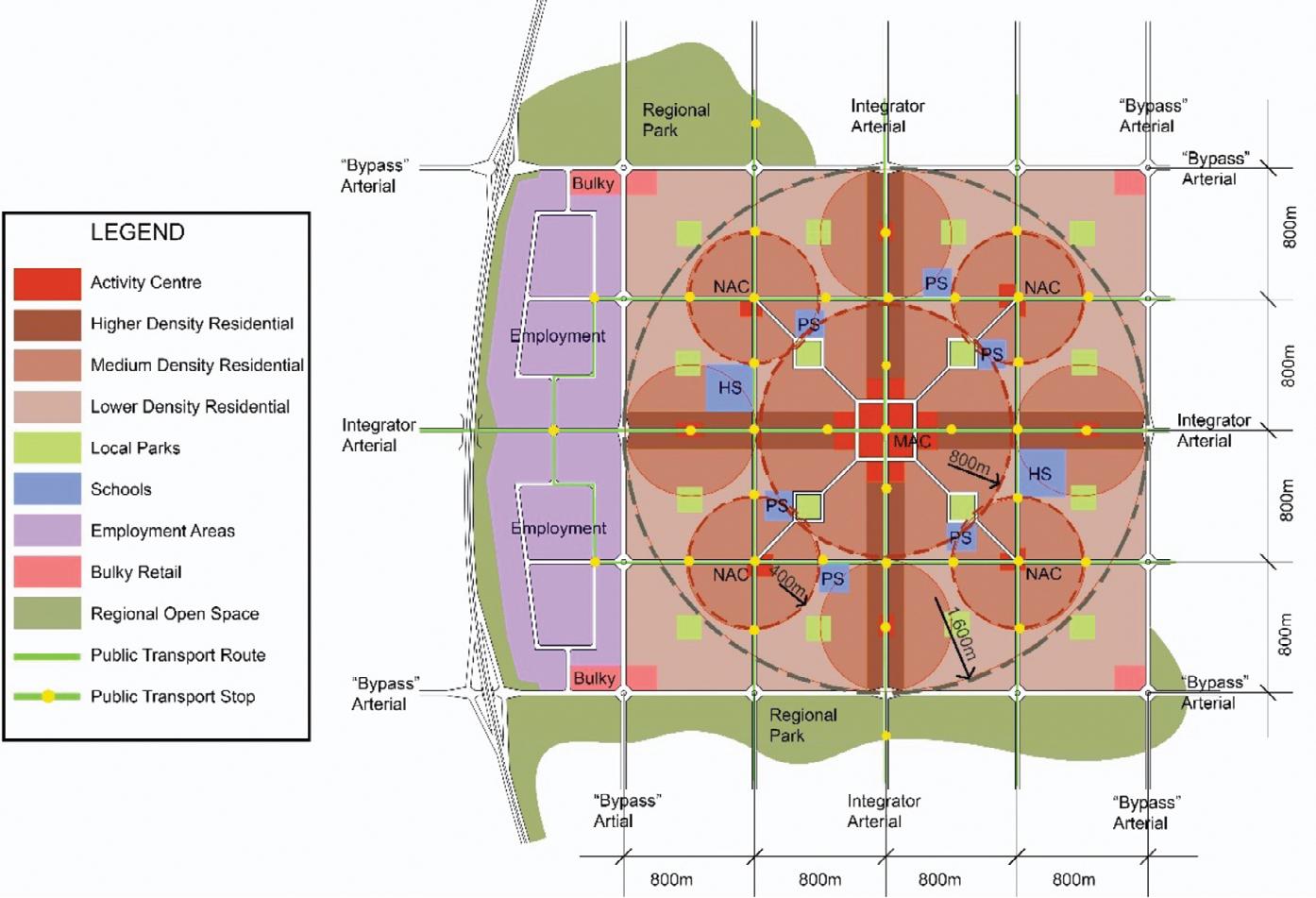

Question: I think this question of how we avoid the kind of lowest common denominator architecture without preventing the top, that’s such an important question. I just wanted to ask, I love this idea of protecting buildings that aren’t listed, or aren’t in the HO. I presume there’s an embodied energy argument for that as well, so there’s a kind of multi-layered argument as to why we should do that.