Theory and Practice

Selected Delivery Dynamics in Discus Throwing

In discus throwing, the period of time between the landing of the left foot in the front of the ring and the actual release of the discus, is called the delivery phase. During that phase all discus throwers are in double support (both feet on the ground) for the majority of its duration. However, at the moment the discus is released, there are differences among throwers in that some maintain contact with the ground at release whereas others have lost contact with the ground at that moment, with both feet. everal years ago coaches, particularly Europeans, would advocate the maintenance of both feet on the ground at release, (whether a no reversing, or a quasi reversing or a full reversing of the feet technique was employed), an idea that made sense from a biomechanical point of view and was widely adopted. In fact, those days almost all women discus throwers would exclusively employ the grounded, double support, technique of releasing the discus. In the subsequent years, work carried by Dapena & Anderst (1997), has shed some light on what may be happening during grounded (one or both feet on the ground), or airborne (both feet off the ground) release of the discus. A discussion of the major concepts involved during that exact phase in discus throwing and whether one or the other method is more advantageous, is presented below. Since, at the moment of the discus release, its velocity is of paramount importance, the examination of velocity itself is central both in the horizontal and the vertical directions.

KIRBY

MECHANICAL BASIS FOR THE GROUNDED DELIVERY

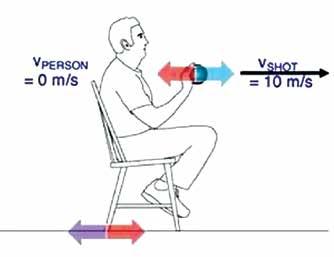

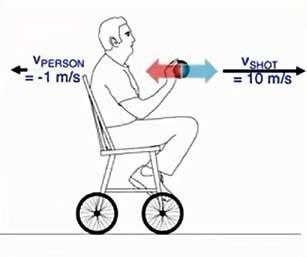

1. Linear movement, horizontal velocity One can follow different kinds of logic to assess the advantages or disadvantages of being off or on the ground during discus release, but a simple example using translational (linear) movement is as shown in figure 1. Here we have a person sitting on a chair while attempting to push a shot

straight out and forward. He is exerting a force on the shot (blue arrow) and the reaction to that force is in the opposite direction (red arrow) and is of the same magnitude. Since the thrower is connected to the chair, together they act as one system. Therefore, as the thrower pushes the shot forward, the shot pushes the system backwards so the legs of the chair push backwards (purple arrow) and the reaction to that force is again

an opposite force (red arrow) of the same magnitude. Since the two reaction forces (the two red arrows) are equal and in opposite directions, they add to zero and the system indeed remains steady and with no velocity. In these early stages of the attempt the shot may have reached a velocity relative to the ground, of say 10 m/s., with the velocity relative to the person’s shoulder, also at 10 m/sec.

FIGURE 1. RUDIMENTAL FORCES AND HYPOTHETICAL VELOCITIES INVOLVED IN A SEATED FORWARD PUSHING OF THE SHOT, (ADAPTED FROM DAPENA, 2024).

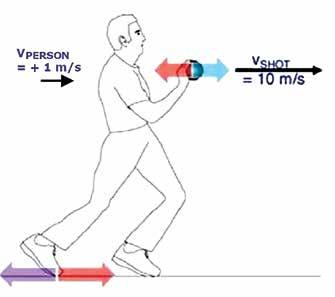

FIGURE 2. RUDIMENTAL FORCES AND HYPOTHETICAL VELOCITIES INVOLVED IN A SEATED (ON WHEELS) FORWARD PUSHING OF THE SHOT (ADAPTED FROM DAPENA, 2024).

FIGURE 3. RUDIMENTAL FORCES AND HYPOTHETICAL VELOCITIES INVOLVED IN AN UPRIGHT FORWARD PUSHING OF THE SHOT (ADAPTED FROM DAPENA, 2024).

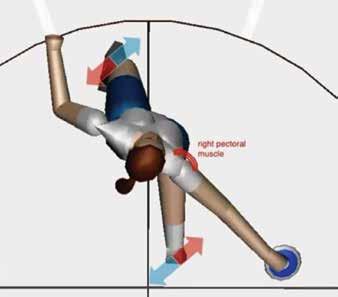

FIGURE 4. PUSH-PULL FORCES EXERTED BY THE FEET ON THE GROUND DURING DELIVERY (ADAPTED FROM DAPENA, 2024).

A similar situation is shown in figure 2, with the chair, however, being supported on wheels. In this case, there will not be a reaction force from the chair and the chair+thrower system will move backwards at a velocity that will depend on the mass of the person and the weight of the shot. For practical purposes we will assume that the backwards speed is at 1 m/s. Under those conditions, the shot’s velocity relative to the ground will again be 10m/s., however, the shot’s velocity relative to the shoulder of the thrower will be 10+1=11 m/sec. Since higher velocities should require faster contractions of the muscles involved in the throw, and since muscles can exert larger forces at slower speeds of contraction (Hill, 1922), in this case, a higher relative speed between the shot and the thrower means that the thrower under those conditions can exert less force, in the ensuing effort to fully

extend the arm, as compared to the first case in figure 1. So the set up in figure 1 (net zero velocity of the chair+thrower system) is more conducive to higher force generation. Another potential set up is shown in figure 3. Here the thrower is upright and in contact with the ground. The actionreaction forces on his hand are the same as in the other cases as is the velocity of the shot at that exact time. However, here, the thrower can choose to actually use his leg muscles and exert a large force on the ground (long purple arrow) which will produce the reaction force (long red arrow). Obviously, the reaction force exerted by the shot on the hand, is smaller than that on the feet. At the time then, the shot is reaching the 10 m/s., velocity, the body of the thrower is also moving forward at, say, 1 m/s. In this case, the velocity of the shot relative to the ground will again be 10 m/s.,

but the velocity of the shot relative to the shoulder of the thrower will be, 10-1= 9 m/s. Therefore, here, this lower relative speed of the shot means that the thrower will be able to exert an even larger force on the shot. Comparatively then, the set up in figure 3 is the best (better potential for force exertion), followed by that in figure 1, while the one in figure 2 is not recommended.

From all described above, mechanically speaking, it is to the advantage of the thrower to keep both feet on the ground during the delivery phase of the projectile. Jumping up during release (losing contact with the ground) will be similar to the set up in figure 2, where there is a backwards acceleration of the thrower’s body resulting in less potential to exert maximum force.

2. Rotational movement, horizontal velocity In discus throwing, during the delivery

phase (figure 4), there is also a theoretical mechanical advantage in maintaining contact with the ground throughout the delivery phase for the same reasons described earlier, namely, the grounded release allows the muscles to be in slower contractions, resulting in higher force production, which is associated with obtaining a greater amount of angular momentum from the ground. Figure 4, shows the ground forces exerted by the thrower on the ground (blue arrows) which result in the reaction forces (red arrows). If the thrower were to jump up and lose contact with the ground the forces depicted in blue will be absent (as will the reaction forces in red) and the generation of angular momentum will be, theoretically, compromised.

The aforementioned reasons are the foundation behind the logic to conclude that being in double support throughout the delivery phase is the prudent way to release the discus.

ANGULAR MOMENTUM CONSIDERATIONS

To better quantify the size of the angular momentum and its significance during the delivery phase, first, we are going to hypothesize that by remaining in double support during the whole delivery phase, a thrower can produce 20% more angular momentum than if throwing airborne. Although empirically this seems to be an optimistic percentage, it is nevertheless a significant improvement and will aid in producing more horizontal speed for the discus. It needs to be pointed out here that, around 90% of the angular momentum about the vertical axis (horizontal velocity of the discus) is generated at the back of the ring and only around 10% is generated during the delivery phase (for more see Maheras, 2022). Therefore, the hypothetical 20% improvement mentioned above does not mean that the advantage will be a comparative 20% increase in the total angular momentum. Rather, it would be a 20% increase in the small, 10%, of angular momentum that is produced in the deliv-

ery phase. Twenty percent of 10% would be only 2% of the total angular momentum produced during a discus throw. So assuming that there is a practical advantage of the grounded release method, that would be minimal. However, even 2% is better than none, so, so far, it seems that staying in the ground is better than losing contact during the discus release.

Many coaches have found it logical to assume that the majority of angular momentum was generated at the front of the ring during the all-in, explosive delivery phase. This way all attention was focused to that phase and emphasis was given to the release method (grounded release) as the method that will produce the bigger advantage.

FROM THEORY TO PRACTICE

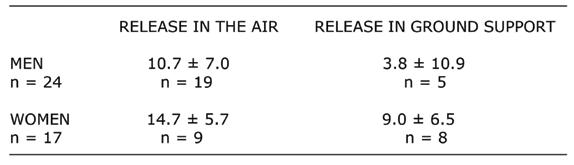

Table 1, shows the angular momentum values during the delivery phase, observed by male or female throwers, as a percentage of the total angular momentum produced during a discus throw (Dapena & Anderst,

TABLE 1. PERVENTAGE OF TOTAL ANGULAR MOMENTUM, ABOUT THE VERTICAL AXIS, PRODUCED IN THE DELIVERY PHASE.

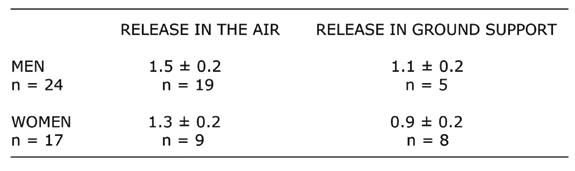

TABLE 2. AVERAGE VERTICAL VELOCITY OF THE SYSTEM’S CENTER OF MASS, IN THE LAST 1/4 TURN.

1997). Those values show, that throwers who were airborne at discus release were able to generate higher percentage values of the total angular momentum generated, during the delivery phase as compared to those who maintained contact with the ground. This is an unexpected result as all theoretical evidence had led us to believe that no matter how small the advantage, indeed there should be an advantage when employing the grounded method of releasing the discus.

LINEAR MOVEMENT, VERTICAL VELOCITY

An attempt to try to explain the observed discrepancy could, in addition to the horizontal, examine the production of linear vertical velocity also. For that, the average vertical velocity of the center of mass during the last quarter turn, roughly from the low point of the discus until release, will be considered (Dapena & Anderst, 1997). Table 2 shows the vertical velocity of the center of mass, for both genders, during the mentioned period. It shows that in all cases the vertical velocity for the grounded release method is significantly lower compared to that during the airborne method.

The thinking on the part of the grounded release method may be, that during the delivery of the discus although the vertical velocity of the center of mass (vertical velocity of the discus) may be lower in the grounded method, the opportunity to produce large angular momentum about the vertical axis (horizontal velocity of the discus) is greater and that this advantage, may give the grounded method a better overall result. However, as it was discussed earlier, this is not the case. The grounded release method does not seem to produce neither larger amounts of angular momentum, nor does it produce higher values of vertical velocity during the delivery phase.

To explain the apparent failure of the grounded throwers to produce more angular momentum around the vertical axis at release, Dapena (2024), speculated that during the delivery phase the thrower pushes directly downwards against the ground, and at the same time he is also making push-pull forces that are exerted by the feet on the ground during that phase (figure 4). In the case of the grounded method, the thrower, to avoid becoming airborne, may inhibit the production of large forces in the vertical direction, and incidentally and unwillingly he may also inhibit the production of pushpull forces the ones that are mostly respon-

sible for the production of the generation of angular momentum about the vertical axis and the horizontal velocity of the discus.

SUMMARY

Releasing the discus in double support as compared to being airborne has only a small effect on the result of the throw. In the vertical direction, releasing the discus while in the air produces more vertical velocity for the thrower, helping in the production of more vertical velocity for the discus. As for the horizontal velocity, theoretically, being on the ground during release should allow for the generation of more angular momentum about the vertical axis and eventually the production of more horizontal velocity for the discus. In practice though, the opposite is true. Releasing the discus while airborne, produces more angular momentum about the vertical axis and higher horizontal velocity for the discus. According to the presented data, releasing the discus with the feet on the ground is a bit worse than releasing the discus while airborne.

REFERENCES

Dapena, J. (2024). Personal communication.

Dapena, J. and W.J. Anderst. (1997) Discus throw, #1 (Men). Report for Scientific Services Project (USATF). USA Track & Field, Indianapolis.

Dapena, J., M.K. LeBlanc and W.J. Anderst. (1997) Discus throw, #2 (Women). Report for Scientific Services Project (USATF). USA Track & Field, Indianapolis.

Hill, V. (1922 ). The maximum work and mechanical efficiency of human muscles, and their most economical speed. Journal of Physiology, 56:19-41.

Maheras, A. (2022). Speed GenerationMomentum Analysis in Discus Throwing, Techniques for Track and Field & Cross Country, 15 (4), 34-42.

The Full Names and Complete Mailing Addresses of the Publisher: Sam Seemes, 1100 Poydras St., Suite 1750 New Orleans, LA 70163. Techniques is owned by USTFCCCA, 1100 Poydras St., Suite 1750 New Orleans, LA 70163.The Average Number of Copies of Each Issue During the Preceding 12 Months: (A) Total Number of Copies: 7.096 (B1) Paid Circulation through Mailed Subscriptions: 7,048 (C) Total Paid Distribution: 7,048 (E) Total Free Distribution: 0 (F) Total Distribution: 7,048 (G) Copies not Distributed: 49 (H) Total: 7,096 (I) Percent Paid: 99% The Number of Copies of a Single Issue Published Nearest to the Filing Date: (A) Total Number of Copies: 6,372 (B1) Paid Circulation through Mailed Subscriptions: 6,297 (C) Total Paid Distribution: 6,297 (E) Total Free Distribution: 0 (F) Total Distribution: 6,297 (G) Copies not Distributed: 75 (H) Total: 6,372 (I) Percent Paid: 99% Signed, Sam Seems STATEMENT REQUIRED BY TITLE 39 U.S.C. 3685 SHOWING OWNERSHIP, MANAGEMENT AND CIRCULATION OF TECHNIQUES, Publication #433, Published Quarterly at 1100 Poydras Street Suite 1750 New Orleans, LA 70163. The business office of the publisher is 1100 Poydras St., Suite 1750 New Orleans, LA 70163.

DR. ANDREAS V. MAHERAS IS THE LONG TIME THROWS COACH AT FORT HAYS STATE UNIVERSITY IN HAYS, KS.

Recipe for Success

Creating Cornerstone Culture for Your Program

Many coaches have wondered why some programs have an excellent, thriving culture year after year that everyone wants to be a part of, and why some cultures are much less desirable and often even toxic. What is the secret to developing a great culture? Are there secrets? Is there a model to follow?

First, a formal definition of culture straight from the Merriam-Webster dictionary: “A set of shared values, goals and practices that characterize an institution or organization.” That sounds all good and dandy. But what

does it really mean? My less formal definition of culture in layman’s terms: “Culture is what you are. It is what you collectively value and the way you cooperatively do and feel things as you passionately work toward a common goal.”

Our intent with this presentation was to gather different perspectives and information pertaining to program cultures from leading track and field and cross country coaches. First, though, we will offer an explanation of the culture at the University of Mary (Bismarck, ND) where the author was the

director of track and field and cross country for 24 years (46 conference championships and over 400 All Americans in that span).

We also reached out to both present and former athletes for their perspective. Our survey was constructed around three major questions: (1) What do you deem a great culture? What are the ingredients? (2) How can a great culture be built and sustained? Is there a model for coaches to follow to create a great culture in a program? (3) What is the role of the athlete(s) in developing a great culture?

An additional question for coaches was this: What advice would you offer a young, beginning coach who is attempting to establish and create a great culture?

The goal for the coach is to guide athletes and programs to perform at their highest level. That typically does not happen without a great culture. Some of our own general thoughts and reflections on culture before we move onto the University of Mary culture:

• A coach has the power to create their own reality and values that comprise the culture of the program. A coach must decide on the behaviors that are acceptable and which behaviors are unacceptable.

• The coach must know themselves and their philosophy before they can establish the culture they want. In his book entitled, “Win Forever,” former Seattle Seahawks coach Pete Carroll summed this up very well: “When you truly know yourself, you have the best chance of using your strengths to your best advantage.”

• A coach must be the culture. A very common theme in great cultures is that the coaches are consistent and don’t change their core values. Your culture can’t be something you are not. The culture of a program will quite often assume the personality and identity of the coach. Looking back, I can see this very clearly in the culture we built at Mary.

• The head coach and the staff must together build and put the culture in place. We always emphasized that the entire staff must be on the same page if culture is to be created. But ultimately, the athletes will have to embrace and sustain it. The athletes are the vanguards of your program and culture.

• Great leaders always have a vision, and a great culture is part of that vision and mission. Great leaders understand that culture is very dynamic — it is never static, and it is constantly changing as the athletes in a program come and go and change on a yearly basis.

• At the end of the day, culture is a mindset. It is the persona of the program. And it will have a huge impact on any program that wants long term success.

MARY CULTURE CORNERSTONES

The cornerstones of the Mary culture are summarized below with explanations: A passion for excellence, for winning and for being successful. The most important trait for any individual, in my mind, is having a passion for excellence, whether that be in athletics, business, music or life. There are many forms of passion. An example would be one of my daughters, a highly successful realtor, who always reminds me that her

number one passion in life is “being the best mom she possibly can be to her two children.” We built a very passionate, collective community striving for excellence at the University of Mary. Our aim was greatness. That was the expectation. That was our passion. We always referred to our program as the school “where legends were made.” That was the foundation of our culture. Excellence became the standard and sustained success fueled a quest for more and greater success. One of my favorite things to tell athletes, and especially young athletes: “Never be content. Good isn’t good enough at the University of Mary. We want to be great.” The pursuit of excellence needs to be an ongoing process. I have always said that I shaped the groundwork for the culture at the University of Mary. But Jamey Mulske defined our culture. She was the standard bearer. Mulske was a small town North Dakota athlete who won eight national championships and was a 21-time All American for the Marauders, while earning a spot in the NAIA Hall of Fame. Mulske had an unbelievable passion to be the best and to be a champion. She was willing to do whatever it took to win and be successful. There is no question Mulske made everyone around her better, including teammates and coaches. She certainly made me a better coach. She would very frequently ask me and challenge me with the same question: “How are you going to make me better, Coach?” She didn’t leave me many options. I had to work at being a better coach to guide her to a higher level of performance. Great wasn’t good enough for Jamey. She always wanted to be better. Her mindset was greatness, and she used her passion for excellence to raise our entire culture to that level. I have often wrestled with whether passion can be coached. My feeling after 46 years of coaching is that it is indeed exceedingly difficult to mentor. But I strongly believe that a great culture can certainly foster a passion in your team and athletes. It can most definitely be an infectious element.

An excellent work ethic and the willingness to do what it took to be successful became the norm. Our culture started as a moderate success story and evolved into a tradition of excellence. One of the major reasons we were able to achieve the success we did was an unbelievable work ethic that became a vocal point of our culture. The slogan on the back of our very first team T-shirt was this: “Excellence doesn’t just happen.” We were very emphatic that we had to establish and sustain a culture of working harder and smarter if we were going to be a successful program. Many newcomers arriving for the first time in our program needed some

pushing and prodding to train at the high levels we desired. Our athletes, though, were surrounded by teammates that would go the “extra mile” and push even beyond their limits and that certainly created an atmosphere where a great work ethic was the expectation. Athletes and people in general rise to their level of expectation. A great work ethic is contagious and became a prominent part of the Mary culture.

Coachability, listening skills and trusting the process were valuable assets. It was stressed that it was very difficult to be successful if you weren’t willing to trust the process that we had established. Athletes who didn’t believe in our process were assisted in finding another school. We underscored that our process was a “tried and true” system that had worked well for many athletes over a long period of time. Not that it couldn’t be customized and tailored to meet the needs of individuals, but we deemed it worthy of the athlete giving it an “honest effort.” The fact that our process had led to unparalleled success at the University of Mary was often a huge selling point in the athletes “buying in.” Most would agree that athletes must take ownership in the mission if they want to be successful.

Consistency in training at a high level over long periods of time was extremely valued. We always stressed that our most successful athletes were all able to remain healthy and train at an elevated level on a consistent basis. There was certainly an emphasis on “doing the things that you need to do” to stay healthy and injury free. Our athletes were made very aware that they would need to make sacrifices and difficult, dedicated decisions if they wanted to obtain consistency in the very necessary, high level training.

Relationships, communication, accountability and honesty were emphasized. One of our key talking points was that success in life was dictated by strong relationships, honest communication, and being accountable. We discovered very quickly that athletes that weren’t honest with themselves had a difficult time being accountable.

I have always said that “life is about relationships. The X’s and O’s are critically important. But it is about relationships. It’s about connections.” A sense of belonging is a key component in Maslow’s (Abraham) hierarchy of needs. His theory of psychology on human motivation says that people need and want a sense of belonging. Our Mary culture manifested that.

The goal was to produce good people of character, good leaders and people who could be productive members of society. Academics and education were obviously

high priorities, as they should be at any collegiate institution. We always said that education and athletics “worked hand in hand” at the University of Mary. We were extremely proud of the 187 Academic All Americans that were achieved during our tenure. With that being said, however, we always stressed that, “not everything is learned in the classroom.” Life outcomes and personal growth come from experiences outside the classroom, too, and our program and culture nurtured that. We felt one of our tasks was to prepare our student-athletes for the challenges of the real world and the realities they would face post college. An excellent quote from Pat Williams in the book “Every Day is Game Day,” which he wrote with Mark Atteberry, certainly applies: “Always remember that the whole world is a classroom.”

Enough about our Mary culture. Let’s move to the questions that the coaches and athletes answered for our project:

SURVEY CULTURE QUESTIONS

Question 1: What do you deem a great culture? What are the ingredients? I received what I thought was an odd answer at the time when I asked my son, Troy, about selfconfidence for an article I was doing about a year ago. A successful cross country and track and field coach at Sheyenne High School in West Fargo, North Dakota, Troy

answered with this reply: “We always strive to make practice the most enjoyable part of the day for our athletes.” When I pressed my son about his answer, he noted that enjoyment for the athlete was one of the most important values in their team culture and contributed to their success. I had never really looked at culture through that lens. Obviously, I needed to re-evaluate. Many of the coaches who responded to our survey echoed the same sentiments as my son when asked about great culture.

“The hours spent at a practice or meet should be an escape from the outside world,” said Dana Schwarting from Lewis College (IL). Chris Parno, the extraordinarily successful sprint/hurdle specialist and many time coach of the year from Mankato State (MN), alluded to the same thing as Schwarting when asked about great culture. “An easy answer is that it is having a group of coaches and athletes that enjoy showing up every day to get the work done that is needed to be successful in our sport.”

Cale Korbelik, a very successful coach from the University of Mary (ND), said much the same thing. “It is where athletes and coaches gravitate to every day for practice and team comradery,” he explained very simply.

The survey results certainly confirmed my belief that a huge part of culture is about feel-

ings and what everyone connected with the team or program feels. Long-time, veteran coach Tommy Badon from the University of Louisiana, summed this up best. “Culture is certainly intangible. You can’t really touch it, but you can feel it,” said the head coach of the Ragin Cajuns, and one of the most renowned coaches in the country.

Feelings were just one of the ingredients listed by coaches and athletes as to what constitutes great culture. Some of the other major ingredients that make up a great team culture, according to the coaches and athletes in the survey, were trust, leadership, vision, high but realistic expectations, caring, communication, good relationships, sense of belonging (inclusiveness), accountability, and a team first attitude working toward a common goal. Dennis Newell, the cross country and distance coach at North Dakota State University in Fargo, talked about ingredients and their importance in building a strong, healthy culture. “It is important to create a set of foundational ideas, attitudes, values, and goals that you believe in and can think and behave passionately about every day,” said the longtime coach, who had been very successful coach at the University of Mary (Bismarck, ND) before moving to NDSU four years ago. “Those variables and ingredients will vary for a variety of reasons. The key is to design the framework, educate the information and thinking, and then behave in accordance with your values as you work towards your goals,” said the 21-time coach of the year.

There was a consensus among the coaches and athletes that the “culture creator” must be the coach, and it is the coach who provides the leadership for a great culture. Are athletes important? Yes. Vitally important. You cannot have a great team culture without the athletes buying in and taking ownership. But nearly all the coaches and athletes agreed that the coach sets the tone, and that leadership is extremely critical to creating and sustaining a great culture.

Amelia (Maher) Sherman, a standout track and field athlete from the University of Minnesota-Duluth and a former collegiate coach, summarized this very well. “Creating great culture has a lot to do with the coach(es),” said Sherman, who coached at High Point University (NC) and Mary. “I think a coach needs to know their values and beliefs in order to be a strong leader for others. You need to be a strong leader to establish a great culture. Culture is about everyone buying into a common goal, and being invested in the performance, and the functioning of the team as a whole. A

coach needs to see the value in each individual member’s role and contributions to the team. I think it’s hard to achieve that when you don’t have trust in your leadership. I think consistency, reliability, and emotional stability are all characteristics that are important for building that trust.”

Julia Hammerschmidt, an All American collegiate hurdler and the track and field coach at Bismarck State College (Bismarck, ND), echoed the same sentiments as Sherman regarding leadership by the coach. “The head coach needs to create and lead by example to have a great culture,” noted the coach, who had been an assistant at Chadron State (NE) prior to BSC. “The assistant coaches and athletes will follow,” she added.

Jim Vahrenkamp, the head track and field coach at the University of North Dakota (Grand Forks, ND), further added to the comments by Hammerschmidt. “I always fall back on the role of coach as a teacher,” noted the Fighting Hawks mentor, who was a 14-time coach of the year at Division II Queens (NC) prior to arriving at UND four years ago. “Our people come to us from so many different backgrounds and experiences. The unifying themes should be the principles that we share with our group. Specifically, what is said is important, but more so, what we allow, we give implicit approval to. Being consistent with what you say and how you act can really go a long way. So yes, know what you want for your culture, be intentional, talk about it, and teach about it. Athletes need regular, positive feedback about it, and less about it when you don’t see it. Don’t tolerate people that don’t want to be part of the group. Adopting the identity of the whole is an important step for any team. You can ask the simple question, ‘who are we,’ and you’ll get a pretty good idea of what your culture is.”

Several coaches promoted the idea that the coach is not only a leader of the culture, but needs to be a role model as well, and that character-building should be an important part of a team’s culture. Some coaches voiced disappointment with how some coaches have lost sight of character in the value system. Reece Vega from North Dakota State University, who feels environment is a better term than culture for his group, said his role has two tiers. One tier, he says, is fostering character, and the second tier, guiding athletes to success. Vega, a very successful sprint/hurdle coach who had one of the top hurdle programs in Division 1 last year, says ego and pressure to win and “get results” is the reason many coaches forsake the character part of culture.

In addition to coaches and leadership,

expectations, and a sense of belonging with everyone having ownership and working toward a common goal were the other major factors that coaches and athletes said contributed to a strong culture.

Mason Rebarchek, the long-time coach at Winona State University (MN), who has had many successful athletes and great teams at his Division II school, put it very bluntly: “I don’t think about culture very often. I think about expectations because they create culture. Great culture starts with the attitudes and expectations of the coaching staff. Great culture is a team full of athletes that want to work hard with a great attitude and be committed to the things that it takes to be successful. That starts with expectations. That is the first line of my team policies.”

Coach Rebarchek and his staff have many of the normal expectations that you would find in most programs, including respecting yourself, and respecting others. But it was interesting to note the line that stood out in his policies: “The easiest part of college track and field is the two hours a day you spend at practice. All you have to do is show up on time with a great attitude and ready to work hard. Your event coach has everything planned for those two hours. It’s the other 22 hours of the day that require effort and commitment.” Coach Rebarchek goes on to list expectations like sleep, nutrition and supporting teammates as just a few of the many expectations that make up the Winona State culture.

Several other coaches weighed in on the expectation factor of culture. “Clearly defining the expectations is crucial,” claimed Ryan Godfrey, an assistant cross country and distance coach at Oklahoma State. “ If the group is to be successful, then work is required,” expressed the coach, who had stops at North Dakota State University, Kansas State and Nebraska before arriving at Oklahoma State. “Secondly, when great effort is given by the athletes, the coach should recognize the effort. When an athlete receives recognition from a coach for a job well done, it becomes contagious. Rewarding the effort is many times simply done with a ‘good job’ and a pat on the back and other times, the reward can be tangible,” said the coach, who directed NDSU to the Division II national women’s track and field title in 2002.

Coach Hammerschmidt, who came to the University of Mary from Germany, added to that: “Great cultures have a positive but competitive environment with high but realistic expectations.”

Coach Schwarting, who arrived at Lewis in 2002 and is the president of the Division II Coaches Association, talked about the

recruiting component, like many of the coaches in the survey. “A coach needs to sell their reality to recruits on what the culture will be and preach every day to the current team what the expectations are,” declared the veteran coach.

The real essence of a great culture, in the minds of many of the coaches and athletes who responded to our survey, was the athletes feeling a sense of “belonging” and “ownership” as they worked together toward success and a common goal. Coach Vahrenkamp, who is often very analytical, approached the concept with a philosophical slant. “I think it is important to make culture a cooperative endeavor,” noted the coach, who guided Queens to 21 conference championships before taking the reins at UND. “It drives buy-in when people feel like they are a part of deciding and developing a place or organization that promotes a specific set of principles that make up the culture. Shared goals and knowledge can be huge motivators. They also drive feelings of safety and security. Maslow was on to something with his hierarchy of needs. Self-actualization and being the best that you can be requires certain things to be fulfilled first. It’s a simple truth. Regardless of the priorities of the group, being able to reach the apex of selfactualization always needs to be met for the individual.”

Josh Lamers, an All American hurdler at Mary who had transferred from a Division 1 institution, provided an athlete’s perspective: “At Mary, it was a very different experience,” voiced Lamers, a standout high school hurdler from Louisiana. ”The team felt like a community where each person was valued, and the focus was on getting better and making progress. The smaller team allowed each of us to be treated as individuals and develop closer relationships with each other. The coaching style at U Mary was tailored to meet the needs of each athlete, and I felt like my performances made a meaningful contribution to the team.”

Both Coach Schwarting and Coach Pol Domenech from Wingate University (NC) added to Lamer’s take. “The environment a coach creates needs to be inclusive to each individual and who they are,” stated Schwarting. “A great team culture is such where every member of the team and staff feels like they belong and own,” opined Domenech. “I believe humans crave that sense of belonging, and providing a space where all student athletes feel like they belong is one of the major cornerstones of a great team culture,” he added.

Mandy (Schroeder) Sheldon, a four-time national champion at Mary who had trans-

RECIPE FOR SUCCESS

ferred to the Marauders from a Division 1 program, followed that up with a similar statement. “It felt more personal at U Mary, and that it mattered that I did well,” stated the 11-time All American who was inducted into the NAIA Hall of Fame in 2006 and who now is a high school coach. “The coaches and my teammates, and even administrators throughout the school cared about how we did. Passing instructors in the halls and throughout campus, they always said good luck and good job, and I felt they knew how our teams did.”

Tereza Bolibruch, a conference champion in the hurdles from North Dakota State University, echoed some of the same thoughts when she said simply, “Our team was an army. One that would fight together to the end to be successful.” Armando Payan, an assistant coach at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, said it even more distinctly: “It is the WE over the ME in our program at Platteville.”

Eric Hanenberger, the associate head coach at South Dakota State University (Brookings SD), added to that line of thinking when he said goals always must revolve around the team. “There needs to be open and honest communication that the common goal is team first,” said the coach, who is in charge of the very successful sprints/ hurdles program at SDSU.

To summarize culture, many of the coaches had excellent thoughts of what they termed culture. Two of the best, one somewhat more formal, and one less formal, came from Coach Badon and Coach Newell.

“Culture starts with a belief, a way of doing things, a vision that permeates an entire team,” said Badon in a quick down-home version of culture. Newell’s more academic response: “I define culture as a set of foundational ideas, attitudes, values, and goals that are established and maintained with accepted and consistent thoughts and behaviors by the individuals of any organization, program, and team. This helps guide the decisionmaking process effectively and efficiently towards a goal or collection of goals in a manner in which has been agreed upon.”

Question 2: How can a great culture be built and sustained? Is there a model for coaches to follow to create a great culture in a program?

Most of the coaches agreed that there is no real standard model for building culture in a program. There were, however, many perspectives and different viewpoints from both coaches and athletes concerning how

great culture, which is dynamic in nature and always changing, could be built and sustained. Coach Domenech, the fifth-year coach who led his Wingate men’s cross country team to the Division II national championship in 2023, had a great response and summed up the feeling amongst the respondents that there was no exact model to follow: “I don’t think there is a specific model because every team is different. As a coach, you have to work with different personalities every year, so inevitably team culture is something fluid that must be constantly adjusted to fit all the new members, as well as the current members who may be going through some change,” commented the coach.

There were a number of different angles on how to sustain a great culture, but most of the ideas involved athletes, traditions, legacies and recruiting the “right” athletes. Coach Badon had a lengthy but great answer: “I think culture starts by building a program, not a team,” he remarked. “Success is not defined by a year, but by years of sustained success as defined by the goals of the culture. To sustain culture, the coaches need to get athletes to ‘buy in’ to how the team operates, then show and vocalize that standard to younger athletes. Older athletes build the legacy that younger athletes have to live up to. Then as they grow older, they take up the mantel and pass the cultural standards from generation to generation.”

Josh Buchholtz, whose University of Wisconsin-La Crosse men’s team swept the Division III indoor and outdoor national track and field championships last year, said it is critical to recruit the athletes that will “buy in” to the culture that has been established at institutions. “We are looking for the right people to be a part of a culture that has a foundation of excellence established long ago by Coach Guthrie,” said the coach, who is in his 16th year at UW-La Crosse, and who has won 11 national championships. The coach that Buchholtz is referring to is Hall of Fame Coach Mark Guthrie, who was at La Crosse from 1988-2006 and won 22 national championships. “Everyone contributes and carries on the culture that Coach Guthrie built,” noted the coach. “The alumni, administration, professors, and obviously, the athletes.”

Mike Silbernagel, the former head strength and conditioning coach at the University of Mary, said it is a constant process to continue a flourishing culture. “You have to work daily to get the right mindset, work ethic and

commitment,” said the coach, who was at Colorado State prior to Mary, and who is now the director of performance at Sanford Power in Bismarck, ND. “You cannot waiver on what you consider the necessities of a great culture,” he added.

“You always need to be gravitating toward excellence,” declared Coach Hanenberger very simply when asked about sustaining a great culture.

Coach Newell, who directed his NDSU women’s team to the Summit League cross country crown in 2022 and was named coach of the year for his efforts, gave a very detailed synopsis on how to nourish culture: “Great culture is sustained by creating an environment that fosters accountability, affirmation, communication, competitiveness, consistency, discipline, empathy, honesty, leadership, ownership, passion, and teamwork from its individuals within the framework of the team’s foundational ideas, attitudes, values, and goals.” Very well stated.

Question 3: What is the role of an athlete(s) in developing a great culture?

There was no question about the importance and critical role of the athlete in nearly all the responses by coaches in our project. The answers were very blunt and very emphatic. “The source of ingredients in a culture (positive or negative), are the athlete,” proclaimed Carl Caughell, a highly successful jump coach from Sacramento State. “They are the face of the program, and ultimately the end product. Once athletes begin to hold each other accountable you know that your culture has taken foot,” said the associate head coach who had been at Nicholls State (LA) prior to Sacramento.

Coach Korbelik, whose women’s team was seventh in the USTFCCCA Division II all program standings last year, noted that a coach can only take the program so far. “It really comes from the athletes and the leaders in your program,” he declared. Coach Badon concurred. “Without the athletes buying in, there is no culture. They are the driving force behind your team’s culture. One team, one belief system.”

Several coaches talked about how important recruiting is in a program’s culture and getting the so-called “right” athletes for your culture. “Almost every conversation I have with prospective student-athletes centers around team culture,” explained Coach Godfrey, who is his first year at Oklahoma State, and who is a 28-time coach of the year. “The recruit needs to know that we are teamfocused. We have team goals. In the recruit-

ing process, if the prospect I am visiting is only interested in himself or herself, then I move on. We are constantly trying to protect our culture.”

Jack Hoyt from Azusa Pacific (CA) said much the same as Godfrey. “The critical mass of the team needs to be on the same page and event leaders need to be extensions of the coach,” said the APU director of track and field, who came to the California school in 2017 after five years as the associate head coach at UCLA. “There must be a careful selection of recruits who will add to the culture and not be a risk. When athletes understand the team culture and thrive because of it, they will help recruiting efforts immensely,” added the veteran mentor who guided Azusa to the 2021 Division II national women’s title in track and field and was named the women’s Coach of the Year.

VETERAN ADVICE

There was an additional, optional question for coaches to respond to in the survey: What advice would you offer to a young beginning coach who is attempting to establish and create a great culture?

There were a numerous quality responses to this question and some of the best ones came from young coaches who were really just getting their careers started. “Athletes are more likely to buy into a culture, respect the coach, and follow the expectations of the coach if the coach leads by example,” interjected Coach Hammerschmidt, a sixtime All American at the University of Mary. Coach Domenech also offered excellent advice despite his youthfulness: “Not sure if I am qualified to give any advice to young coaches, as I am still young myself, but my advice would be to not hold on too hard to your power,” he said. “Let your student athletes be who they want to be and guide them when they need to be. I believe when student athletes feel free and supported, that’s when great team cultures are created.”

Coach Silbernagel, a former national champion power lifter, commented that coaches should not be afraid to learn from the past. “Coaches shouldn’t feel or think they are on their own in building a culture,” said the long-time coach. “You can learn from those who came before you, and you can most certainly learn from both successes and failures of those coaches who have lived it.”

The most heartfelt, honest, and direct advice came from Coach Newell, always a very detailed, organized and thorough

coach. “Create your ideas, attitudes, values, and goals in alignment with your state, city, university, athletic department, program, staff, and/ or any other entities that may be involved with your organization, program, and team,” said the coach who started his coaching career at his alma mater, Black Hills State University (SD). “Think communal. Do not be afraid to give a voice and ownership to others involved in the program. A GREAT culture is one that values the diversity of the group to collaboratively create a positive atmosphere and environment that everyone has a part in. One of my biggest mistakes as a young coach was my arrogance, ego, and my lust for control and power. The longer I coach, teach, educate, guide, and mentor; the more I realize I need to do just that… coach, teach, educate, guide, and mentor. I do NOT need to control, dictate, and decide every detail of everything the organization, program, and the team does. This is actually counter-productive on many levels from time management to enabling those around me, to me becoming too one-dimensional in my thinking. Create a plan, educate the plan, think, and behave in alignment with the plan. Hold individuals accountable to the plan and ingredients of the culture, give affirmation, assign leadership and/ or allow leadership to develop organically, and then watch what happens!

SUMMARY

It was very apparent from our project that a lot can be learned from coaches who have developed and sustained a great culture. It was also very obvious that there are many different routes to cultivating a great culture. One theme that emerged from our project: The “one size fits all” method of creating exceptional culture is not at all true. One of the messages that surfaced from this presentation was that coaches shouldn’t be afraid to do it their way. The way that suits them and their value system. I am always reminded of the advice from Vern Gambetta, a pioneer in functional training and a former track and field coach, who said you can be either be an imitator or an innovator. Don’t be afraid to be an innovator, he advised. This always reminds me of a famous poem by Robert Frost entitled, “The Road Not Taken.” The last stanza of the poem speaks to what Gambetta is saying:

I shall be telling this with a sigh. Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two roads diverged in a wood and I, I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference. It was very telling and interesting, too, that very few of the coaches equated winning with prominent team cultures. Most of the respondents in this project agreed that a great culture is certainly possible without a program being a big, powerhouse juggernaut. Coach Silbernagel did offer this perspective, however, on great cultures and winning. “While success in whatever the given field of competition doesn’t always equal to a good culture,” he said,“ I have seen very few losing teams who can boast a great culture. Losing seems to bring out the worst in people, which tends to erode whatever glimpses of a great culture there might have been.” Many of the coaches agreed with Silbernagel about success and excellent cultures going hand in hand. Nearly all agreed, though, that there are many different ways to define “success.” Many fell back on the old cliché’ that success is in the “eye of the beholder.” Although there were minor disagreements among coaches and athletes alike on what the “ingredients” are that make up excellent culture, most coaches concurred there is no definitive list. Rather, they agreed that the components of a great culture should be what the coach and program value and are comfortable with. There was absolutely no disagreement, however, that a high functioning, great culture just doesn’t happen without both coaches and athletes working together in a unified, collaborative effort to achieve the culture that is desired.

A very special thank you to Ann Thorson and Ameila Sherman for editing and technical assistance.

MIKE THORSON IS THE FORMER DIRECTOR OF TRACK AND FIELD AND CROSS COUNTRY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MARY. THE FOUR-TIME NATIONAL COACH OF THE YEAR EXAMINES HOW GREAT CULTURE IS CREATED AND SUSTAINED IN LEADING TRACK AND FIELD AND CROSS COUNTRY PROGRAMS

Practical Distance Running Advice for Runners of All Levels Based on 50 Years of Running, Teaching, and Coaching.

IN THE RACE

When you are in a race, here is a checklist: relaxation, pace, race position and strategy, form, rhythm, and easy, even breathing. You especially need to think about these things when you are tired. Keep your head level and your eyes up unless footing is a problem. Don’t look back. Instead, focus on catching the person ahead of you. That doesn’t mean you can’t look back to be aware of who is behind you. However, some constantly look back, interrupting their focus on what is ahead. Assume that someone is behind you and will attempt to pass you at the end of the race. Go hard through the finish. Some other things you can think about to mix things up a little are taking risks to test fitness, thinking of strategy to block you from thinking of the pain, learning what to do from different positions in the pack, working toward the next runner, looking at the runner’s shoulders and not their feet, running over the top of hills, surging and learning when to and when not to use it, paying attention to other runners’ breathing, and relaxing and getting into a natural rhythm to fight off a “bad patch” mid-race. This list isn’t all-inclusive. In elite-level racing, with everyone at approximately the same ability and fitness, losing concentration for even 100m may be problematic. It could be enough for the runner to lose contact with the athletes they had been running with. They may lose their ability to get back with the group before the end of the race. Also, for anyone, loss of concentration in the middle of the race, usually just after the halfway mark, can derail even the best of efforts. Keep your rhythm and stay engaged in the task at hand. This is the same for all of us. It requires training to learn how to relax and stay focused on what you are doing. Practice this during your workouts. Strategy, figuring out how fast you can run, and determining who you should be running with are aspects of racing that must be practiced. An evenly paced plan is the most efficient way to race but may never lead you to explore your potential. Try going out fast a few times. It’s a great way to test your limits when you are ready for it. Can you physically and psychologically break from the field? How fast can you go, and how long can you hold it? Will your energy run out before the race does? Do you trust your conditioning? Can you run strongly enough to carry it on to the finish? Can you go a little farther each race at this faster pace? Can you “settle in” to a pace after a while so that you can respond when you are challenged again, especially near the end of the race?

Or should you go out slowly? The danger with this strategy is that people may get away from you, and you might not see them again until the post-race refreshments. If you start too slowly, will you be able to get back to the athletes you know you can be competitive with? Will your ability to pass runners later in the race get you close enough to be competitive? Will you dig yourself such a big hole that you won’t be able to climb out of it before the finish? Will you get discouraged or get “stuck” in the slower pace and stay slow, unable to work your way back? There are many more questions.

My first “go-to” standard for race strategy is one that I borrowed. It isn’t the only strategy I’ve used, but the basic one I almost always start with. I attended a panel where the term “critical zone” was discussed. This is like football, which uses the term “red zone” to highlight the part of the field where success is critical. The ability of a football team to determine a way to be successful when it is near the goal line defines the team’s character. In distance running, the first two-thirds to three-fourths of the race is about getting a good tactical position, staying relaxed and controlled, and using as little energy as possible. You don’t have to run slowly. If you can stay relaxed while letting others do the pace work and break the wind, that will set you up for a strong finish. It is hard, but be patient.

This doesn’t mean you can’t lead or help dictate the race’s strategy. It means that if you use a lot of energy getting to the twothirds to three-fourths mark of the race, you probably won’t have the energy to respond to someone else’s surge to the finish. Make sure to maintain your concentration between the halfway point and the start of the critical zone, a troublesome time in a race for many runners as their pace tends to lag. I like to define the critical zone as the last third of the race to be more intentional for this challenging period just after halfway. Commit most of your energy and focus to the critical zone. It is more fun to pass people at the end of a race rather than being passed. It gives such a mental lift. Be confident, in control, and ready to move. Practice “owning” the end of the race. So again, start the race, establish your position, maintain a good pace and rhythm, use as little energy as possible, and go hard the last third of the race.

This strategy is directly applicable to many situations. It is particularly valuable in longer races. If you go out too hard in a marathon, or even a 5K or 10K, you are going to use carbohydrates as the primary fuel, your core

temperature will increase, you will lose water and salts more rapidly, and the acid build-up in the muscles will affect your performance. It is like a race between the inside of your body and the outside race that you are trying to finish with a strong performance. Will your carbohydrates run out? Will your core temperature go too high, inhibiting your performance? Will you have enough water to cool and efficiently fuel your body with enough electrolytes to function correctly? Will the acid buildup limit your muscle function? Which side will win that race?

When learning to run in a tight group, practice running in all positions. Try running in front, in back, on the sides and in the middle. Find a comfort level in all places. You may have a favorite strategy or way to race, but you also may be thrust into any of these situations, and you must be able to relax and be confident. Some runners are very comfortable leading a group. They want control and are willing to spend their physical and psychological energy to lead and break the wind for the rest to have control. Others stay in the back, just being towed along for the ride. Using the group as shelter from the wind is a great reason to stay behind others. In a pack where things are a little crowded, refrain from darting back and forth to find free space, essentially unnecessarily doing an interval workout and using a lot of energy. Be patient and see if things open up so you can move to free yourself from a boxed-in position. You can gradually move your positioning so that the people around you have to make decisions about their position, which

may help things open up. If the race is short, you may force the decision more aggressively.

Most people find it best to run next to someone, just off their shoulder and slightly behind. While running directly behind a runner, there are the potential problems of bumping legs, getting spiked or stepping on a heel. Watching the movement of their legs gave me the illusion that they were running away from me and certainly running faster than me. By running next to and slightly behind, I could use their shoulder as a frame of reference, which most people didn’t move very much. It meant that I could keep my head up. This was especially helpful if I was starting to struggle. It was a little chance to relax and refocus.

Be strong and be aware of what is happening around you. Watch others and listen to their breathing. Determine who is struggling and who isn’t. Pay attention. A problem can arise if you aren’t alert when runners in the front positions accelerate and make a break from the rest of the group. This is especially a problem if you are in the middle, have nowhere to go, and can’t make a move to go with the front runners. Pay attention! If the runners are all of equal ability, five meters may be enough of a lead that you won’t catch them before the end of the race. The middle of the pack can also be treacherous, with arms and legs going in every direction. Tangled legs aren’t fun. It is a good place if everyone is calm. If people are jumpy, darting in and out, or unsteady with their pacing, it can make the middle a scary place. Staying

on the outside shoulder slightly behind the leader gives you the advantage of being able to move when you want. You might catch some wind but can put yourself in a strong position.

Learn to stay in contact with a group or another runner. Don’t even give them a meter of space. If you can’t be that close physically, keep mental contact to somehow tie you to them. They are the connection between you and the other athletes in the race. They help you focus on working your way back up to them to be competitive with everyone else. The focus should be on bridging the gap and returning to direct contact. Some people prefer to run a race with no one around them. That isn’t what most people want. Most want to run with another individual or a group. In cases where you find yourself in no man’s land with no one around you, work your way to the next group, latch onto them, and then take a little breather from the work you just did. If there is no group close to you, relax and concentrate on keeping your rhythm.

If you have been gapped and have a distance to make up to catch the next person, focus with your eyes up and on them. Try not to let that gap open in the first place. But if it does, change your rhythm to get back up to them. “Throw them a rope” and gradually work your way back to the group. Look at them. Stay in mental contact. Constantly work toward getting up to the next person and the next. Concentrate on their singlet and will yourself back to them. When you get back up to them, settle in for a few seconds to catch your breath, relax, and recover. It is frustrating if they decide to speed up at the same time as you do or increase their pace just when you have gotten back in contact. That’s a risk you will have to take.

When mirroring someone’s rhythm, pay attention that they don’t slow without you noticing. Don’t get lulled to sleep thinking you are maintaining a good pace. That can negate the good work that you have done. Pass another runner quickly to open distance and break their will. When being passed, change your rhythm to go with them. Pay attention to other runners. Is their breathing strained? Are they struggling? How are their form and foot strike? Are they relaxed? If they are having trouble, can you take advantage? Anticipate an upcoming hill, a turn, bad footing, a group up ahead, or someone trying to pass you that might cause you to be boxed in. Surging may allow you to break from a group, give a clear view of the course or

track, or charge up a hill, but there are costs. Practicing will help you understand the costs and the competitive risks involved.

A strong, steady rhythm is great. There are times when you want to get “stuck” in that rhythm, and there are times when you don’t — when getting “stuck” means you will fall farther and farther behind. When you get tired, try to maintain your rhythm unless your pace is rapidly decreasing. Getting into a solid rhythm can be a very efficient way to cover a lot of ground. But if your stride length, stride frequency, or both deteriorate when you get tired, it can cause you to slow dramatically. When this happens, shorten your stride instead of trying to lengthen it. You can also try to quicken your rhythm to catch someone or ward off a challenge. Sometimes, you might lose your concentration. Changing rhythm can help you regain focus and revitalize your race effort. Do anything to stay focused and engaged. Road and cross country races can do this automatically for you with hills, turns, predetermined strategy, surges, and competitor or personal challenges. In fact, on some courses, constantly changing rhythms is the norm. All this needs to be practiced.

Surging, pushing the pace for short sections during a race, is a great tactic, especially if you are equal to or better than the competition. However, it can be used to your advantage even if you aren’t. It must be practiced, or it could lead to your disaster. Going hard from the beginning can take people by surprise. You can use it to “soften” your competitors. If you want to pass someone, if the pace is controlled, make the pass quickly and carry it on to open a gap. Be careful. It may doom you later if you make an extremely hard surge or pass.

When you know other runners are always extremely fast at the finish, you might start the race harder than usual, attack a hill or another part of the course, or drive to the finish line from farther away to neutralize your opponents’ late speed. A surge as you approach the finish area can help you make it difficult for someone to catch you. If you have practiced and are ready, this could come from a long way out. Surges can be planned or a reaction to something that has happened. Be aware that you might have one or two opportunities to have the energy to make a major move, so you want to use them wisely. The change of rhythm can quickly open a gap that others would have trouble closing. Or it could be an effort on your part to get up to the person or group that’s ahead of you. When you respond to a surge, slowly

reduce the margin of distance, close the gap and get back in contact, wary that another surge may be imminent.

I’ll never forget one of the first world-class 10K races that I saw in person on a stadium track. All the runners had impressive credentials. The favorite was a runner who had won all his races that year. One of the other great runners surged ahead. The favorite gradually worked his way back up to the leader, who surged again just as the favorite caught up. This must have happened four or five times until, finally, the favorite couldn’t respond. The person who surged all those times won the race. It couldn’t have been an easy race for either the winner or the favorite. To see this play out over those 25 laps was highly entertaining. The favorite did everything he could. He didn’t sprint to reconnect with the leader, as that would have been a mistake. He would gradually close the gap to cover the move. On this day, the winner had one more move than the favorite.

FINISH

A strong finish is essential. How much energy should you save? Or should the finishing speed be a strong mental attitude that you know is there no matter how badly you feel? If you save a lot, you may have already gone too slowly during the race and lost a lot of time. Spread the “hurt” out over the whole race. You should especially be in your “critical zone” frame of mind for the long drive to the finish. You might get challenged or passed near the finish, but you might also be racing against another “class” of runners much better than the ones you usually finish with. The training philosophy that I’ve outlined has been to complete every workout strongly. The mental image and the physical presence should be well established. Let that practice carry you over the finish line. It isn’t a bad idea to save a little energy for the end of the race. However, sometimes it isn’t about speeding up but holding your pace while everyone else is slowing down. I want you to be strong at the end, and most of all, I want you to know it, even when you are tired. This must be practiced over and over. Make sure that you race through the finish line. The finish line is the finish line is the finish line. This needs to be practiced, practiced, and practiced every day. Easing your pace before you finish can cost you a victory, a place, a record, or a qualifying performance. Every race should be a strong effort for the whole distance, not a hard race for most of it, with a coast at the end. You want the pain to end as soon as possible. I get that.

Just carry the strong pace for a few more seconds through the finish line. Always assume someone is on your heels, trying to pass you just before the finish line. How often have you seen someone in pain as they approach the finish line, seemingly going as fast as they can only to find another gear when challenged? Always go to that “other” gear.

Learning how to finish a race when you are tired, tight, or struggling is essential. You are almost sure to have a “bad patch.” Some techniques for regaining control are dropping your arms and shoulders, calming your breathing, relaxing your upper body, shortening your stride length, quickening your rhythm, slowing down=/// and focusing on the people ahead of you. Hopefully, you will recover and be able to get going again. Avoid struggling to the finish without attempting to relieve the tightness and pain you are feeling. This is where mental toughness helps as long as you leave some of that mental space to help you finish faster. Float, grab some water or food (if available), and concentrate on your rhythm. Most of the time, you will work your way out of a bad patch and return to feeling more in control.

There can be only one winner. If everyone must be first, there will be many disappointed people. Remember, you aren’t a failure if you fail to take first place. Figure out a plan, a way to be first, and give it your best shot. It is exceedingly rare that someone wins all the time. If you don’t win, assess what happened and plan for a better result next time. If you are competitive and want to do well, your mental toughness may be your ticket. At some point during every tough race, the question will be asked: will I or won’t I? Will you or won’t you put up with the pain, and will you or won’t you do what is necessary to be competitive? This is a quote that I remember from a long time ago, and I don’t remember where I read it, “It is easy to find people who want to win. It is hard to find people who don’t want to lose!”

JIM FISCHER HAS COACHED CROSS COUNTRY AND TRACK AND FIELD FOR OVER 50 YEARS. HE LED THE UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE MEN’S CROSS COUNTRY AND TRACK AND FIELD PROGRAM FOR 30 YEARS WHERE 45 OF HIS TEAMS PLACED IN THE TOP THREE AT CONFERENCE CHAMPIONSHIPS. FOLLOWING HIS RETIREMENT FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE, HE COACHED AT SANFORD SCHOOL AND URSULINE ACADEMY IN DELAWARE. UNDER HIS LEADERSHIP, URSULINE ACADEMY WON THREE STATE CHAMPIONSHIPS.

KIRBY LEE IMAGE OF SPORT