9 minute read

Local Vets Reflect on their Military Service

By Gary Goettling

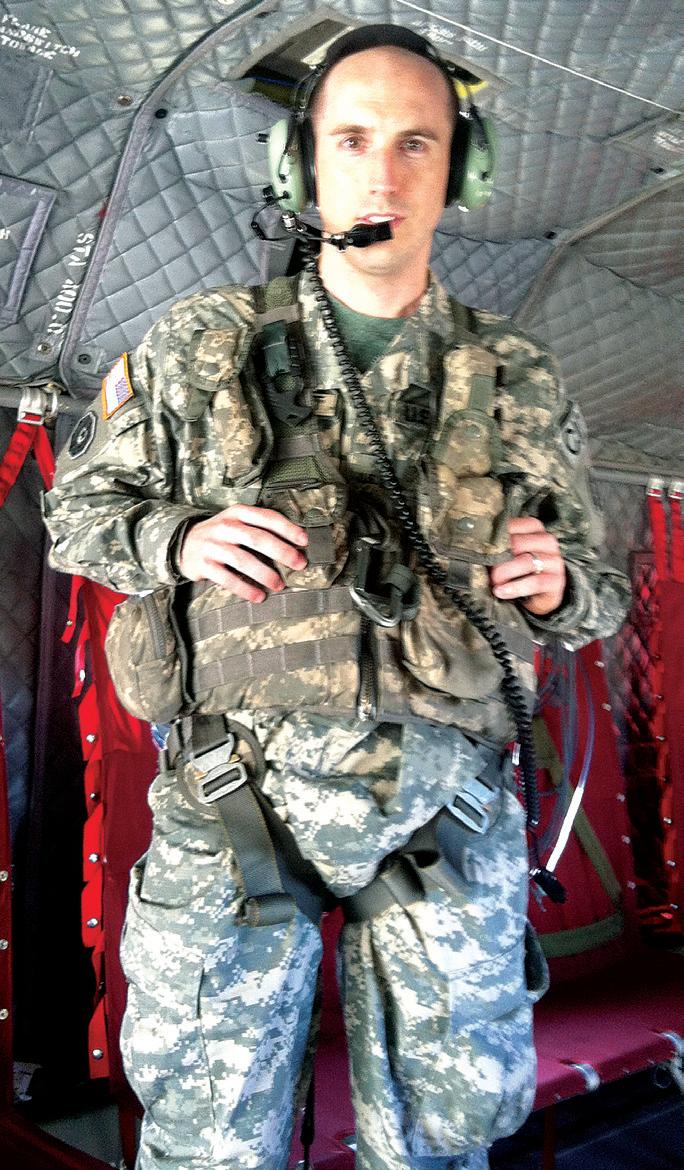

When Jeffrey Burnett signed up for a hitch in the U.S. Army, he was following a family tradition of military service. Hs grandfather and an uncle were Army veterans and his father served in the U.S. Navy. Burnett enlisted in 1997, when he was 18. He started as an infantryman, but took a job as a military policeman as part of his plan to pursue a career in law enforcement. He spent seven years in the Army, including stints in Afghanistan and Iraq, where his group provided perimeter security at the time of the capture of Saddam Hussain.

This month, as Veterans Day returns, we celebrate the thousands of men and women who dedicated portions of their lives and careers to military service to their—and our—country.

“I don't think about me or my service,” said Burnett, who now lives in Tucker. “I think about the other guys—the World War II and Korea veterans who endured so much and accomplished so much and the Vietnam vets who came home to an awful situation.

“When you think about them and what they went through, and you gain a lot of respect for these other veterans. That's what Veterans Day means to me."

Veterans of the major conflicts of the 20th Century—World War II, the Korean War and the War in Vietnam—are aging and disappearing. But they and their service are not being forgotten.

For Veterans Day, here are snapshots of three who served.

Georgia Tech student Jim Tucker was spending the early Sunday afternoon of Dec. 7, 1941 at the Techwood theater on the edge of campus. Abruptly, the film was interrupted by the announcement that Pearl Harbor had been attacked by Japanese aircraft.

"We knew we were going to get called up at some point, remembers the 94-year-old Stone Mountain resident, "but we didn't know when."

At the time, every Tech student at the then all-male school was required to participate in ROTC in their freshman and sophomore years.

"We could then sign up for advanced ROTC, which would require us to attend Officer Candidate School and serve in the U.S. Army for four years after graduation," Tucker said. "However, although we expected to complete our studies first, we were called to active duty on April 6, 1943, at Fort McPherson, and after induction sent to Aberdeen Proving Ground, Md., for basic and cadre training. We were then sent back to Georgia Tech to complete another quarter of college because of a backlog at the Ordnance Officer Candidate School."

Tucker graduated from Ordnance Officer Candidate School and was commissioned as a second lieutenant on May 27, 1944. He then decided to work in bomb disposal and signed up for the rigorous training course in deactivating fuses on bombs and other explosive devices

"I like to hunt, but I don't like to hunt humans," he said of his decision. "I didn't want to be involved in killing anybody, so this seemed like a great thing. I could be a part of the war effort and help, but in a way that was more productive to me."

In 1944 he was sent to the Philippines, where he was assigned to the American Division during their retaking of Cebu in the Visayan Central Islands. The majority of the munitions that needed deactivating were U.S.-dropped parafrag bombs, anti-personnel fragmentation bombs with small parachutes attached that were designed to explode on contact with the ground and spread shrapnel in all directions. The problem was that the parachutes would get snagged up in the bamboo and the field artillery couldn't advance or fire heavy weapons with these live explosives hanging everywhere.

"During the first 30 days after we landed, I had to remove the fuses from over 100 parafrags a day," he said. "I had so many fuses to dispose of, I found a bombedout concrete building in Cebu City where I could toss the fuses over a wall and they'd blow up on the other side. Unfortunately, I became tired or careless, and the last one I tossed one day dropped on my side and took off part of my cheek. I came close occasionally, but that was the only major harm that I suffered."

Tucker also disarmed booby traps and bombs the Japanese had re-purposed as land mines, and "anything else that the commanding general wanted us to take care of."

When the war ended in August 1945, Tucker was sent to occupied Japan to clear out munitions on the peninsula across the bay from Tokyo.

"Big, heavy shells were loaded onto ships and dumped at sea," he said. "For loose munitions— powder and so forth—we'd locate some field or airport nearby and burn them. We burned tons and tons and tons of the stuff."

Tucker was discharged from active duty with the rank of captain on September 10, 1946, in time to go back to Tech for the fall quarter and resume his studies for a chemical engineering degree.

The student body included a large number of returning veterans.

"We didn't particularly care to worry or talk about or reminisce about what we'd just gone through," Tucker recalled. "We wanted to get through our studies and get on with life."

He graduated from Tech in December 1947 and embarked on a long and productive career in pulp and paper processing before retiring in 1991.

While proud of his military service, Tucker didn't often think about it until 1996, when a few classmates proposed that Tech coop alumni who entered Georgia Tech during 1939-1940, but had never had a class reunion because they graduated in different years, have a special muster. Following the muster, several alumni living in or near Atlanta decided to meet for lunch every other month. More than two dozen veterans attended the first musters, but the number has slowly decreased over time. Today there is only Tucker and one other, Jim Ivey.

"Fortunately, Marilyn Somers, director of Tech’s Living History, supports and joins us for lunch," he said.

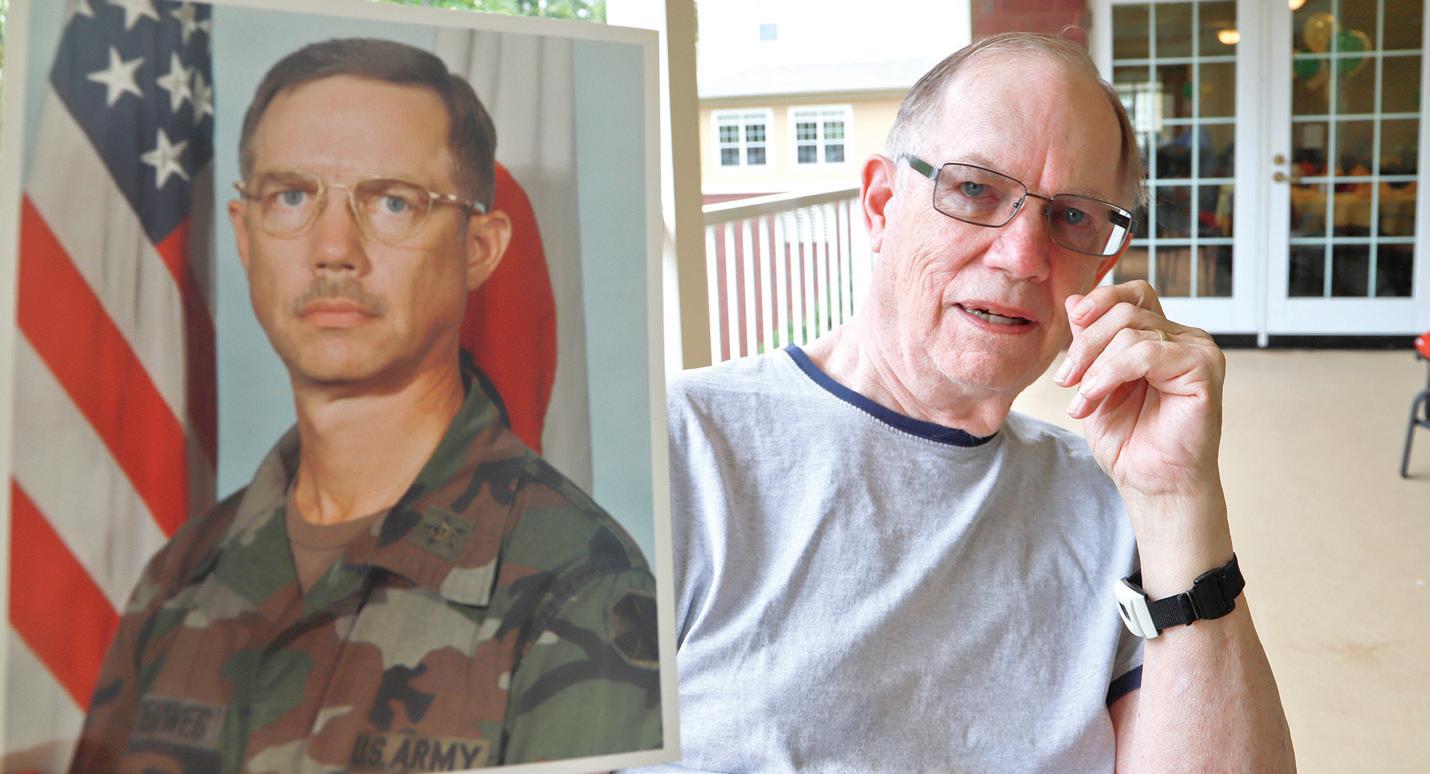

Wilson "Bill" Dreger III

Bill Dreger had wanted to join the U.S. Army ever since he was a little boy growing up in Buckhead, where he'd watch long convoys of troop trucks moving down Peachtree Road during the Second World War.

"It was quite a sight," recalled Dreger, 86, who makes his home in Alpharetta.

He got his wish in July 1950 when he enlisted in the Army Reserve as a private while still a student and ROTC member at Georgia Tech.

"I enlisted in a unit that had been activated for the Korean War, but right after I joined they took it off the activation list," he said.

After 4 ½ years of Reserve service, and by now a distinguished military graduate of Georgia Tech and an alumnus of the Infantry School at Fort Benning, he was commissioned a lieutenant in the regular army. Next stop: Korea, for a 16-month stint as a member in the 21st infantry, 24th division.

He served as a platoon leader at a main battle position on the Imjin River, a major waterway near the boundary between the two Koreas. He later served as a company executive officer and a company commander.

"The war had just ended when I got there—the shooting had stopped," he said, adding that technically, "we're still in a state of war over there. They signed an agreement to stop shooting at each other, but that's as far as it went."

Upon returning to the U.S., he was detailed to Army Intelligence at Third Army headquarters at Fort McPherson. With the move back to the Atlanta area, he spent more time with his father's apartment development and management company. In 1960 he decided to re-join the Army Reserve and pursue real estate full time, eventually taking ownership of his dad's company. Dreger's notable achievements include construction of the first apartments on Buford Highway.

He continued his education by studying mission-oriented training for soldiers at the Command and General Staff College in Leavenworth, Kan., and the Army War College in Carlisle, Pa.

Dreger's steady rise through the ranks culminated with assignments as a staff officer, chief of staff and brigade commander, and in 1983, a promotion to brigadier general as deputy commanding general of the 81st Army Reserve Command.

He retired six years later, closing a 39-year military career, about a third of which was spent on active duty. In the reserve, "I commanded all size units from a battalion to a brigade," Dreger reflected, including "a battalion in Macon that had reserve units all over Georgia." He also noted that, "Every one of the units I commanded served in Desert Storm," the early 1991 military action to force Iraqi invaders from Kuwait.

Earlier in his retirement when Dreger lived in Cumming, he gave talks at the War Memorial there on Veterans Day and on other occasions, "but I've got to an age now where I don't do much of that anymore."

His topics centered on current events related to the military. If he were to deliver such a talk this year, he might speak about medical care provided by the Veterans Administration, which has "gotten totally out of control," according to Dreger.

But for the most part, "I think Americans by and large take care of their veterans very well," he said. "If a need exists and it's identified, they step in and do something about it.

"I am very proud to be a soldier."

Conrad Boterweg

Conrad Boterweg's assignments in Vietnam included a popular and essential service for U.S. troops— he brought the mail.

A native of Perry, Ga., Boterweg, 77, joined the Army in 1962 after graduating from North Georgia College's ROTC program and receiving his commission as a second lieutenant. Thirty years later the Alpharetta resident retired as a colonel.

In between he served a pair of year-long stints in Vietnam, the first beginning in 1966.

"When I first got there, I was stationed in Di An—not so much a town as a little hovel," he said with a chuckle, referring to the American base camp located about 25 miles northeast of Saigon. Boterweg was the personnel officer "in charge of the Army assignments and records that had to do with officers assigned to the 1st Infantry Division"—popularly known as the Big Red One.

During his second tour, which lasted from 1972 to 1973, he worked in Saigon as a postal officer.

"I was in charge of getting mail to soldiers in my division

Continued from page 5 at least once a day," he said. "Everybody liked to see me."

The mail came in on one of the commercial aircraft delivering replacement soldiers. "Occasionally we would receive a package with a cellophane window cut into the top to reveal a homemade cake," he said. "The postal clerks personally hand-carried these special deliveries to each soldier rather than tossing them in the large, locked mail bags."

The assignment had him flying to U.S. outposts all over the 3d Corps region to deliver letters and packages to approximately 25,000 men.

Also moving through the air was a defoliant called Agent Orange.

Due to the thick tree canopy, American forces "couldn't see the Ho Chi Minh Trail," a logistical network thousands of miles long that brought supplies to Viet Cong and North Vietnamese soldiers via bicycle, Boterweg explained. "So

Check out veterans day celebrations on pg. 20

the Army and Air Force sprayed this agent all over toward the trail to cut down the tree cover."

The dioxin-bearing chemical agent was dropped extensively over farms and jungles in Vietnam from 1961 until 1972.

His last military assignment was to Fort McPherson, where he served as the Forces Command adjutant general.

After retiring in 1992, he and his wife, Pat, opened a picture-framing franchise, The Great Frame Up, on the south side of Peachtree City that proved successful enough that they opened a second location on the north side.

Toward the end of the decade, Boterweg began having seemingly unrelated neuro-muscular physical symptoms. A diagnosis eluded doctors for several years until 2001, when it was determined he was in the early stages of Parkinson's Disease, brought about by his repeated exposure to Agent Orange.

"It was pretty much all through the air, and those of us who were susceptible—which was quite a few of us—got Parkinson's disease in addition to other life-threatening diseases related to exposure to Agent Orange," he said.

As the symptoms increasingly limited his ability to work, he was forced to sell both of his framing stores.

These days, he gets around in a wheelchair. The Parkinson’s continues to worsen his ability to eat, swallow, speak and write, and he has frequent falls because of poor gait and balance.

On the occasion of Veterans Day, Boterweg said that he especially remembers "the soldiers who worked for me in Vietnam who gave their lives for their country."

"I'm very proud of my service, too," he added. "Under the circumstances of the time, the use of Agent Orange was the necessary thing to do. It was effective. I don't blame anybody for using it."