11 minute read

The Yard p

The Yard:

The implementation of water management, subsequent food production and quality of life

Advertisement

by Lassen Anna Bundgaard

water collection

(cycle begins with the collection of water and its fi ltration of grey water and rainwater. This system will be applied to each microcommunity)

community

(a stronger more resilient community can fl ourish with an increased quality of life and stronger social cohesion) (production can be sold in order to create extra income for community spending)

micro farming plots

(the water is used to irrigate the courtyard landscape and garden plot. Each microcommunity cares for their own plot and eventually be able to grow their own food)

In the Carabanchel neighbourhood in Buenavista, Madrid the community faces issues of being entirely reliant on external aid and resources. However, through the utilization of the existing structures and resources, it has the potential to become self-suffi cient.

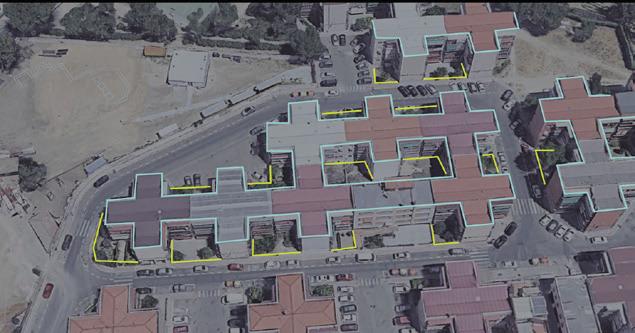

With two types of buildings, one seen as a cross and small isolated groups, and the other as an extending building with minimal space, the areas have courtyard spaces that have yet to become resourceful. One interesting factor of Carabanchel is how the buildings were devised, with only of few having access to parks and green spaces, the majority instead has untouched space. When considering these two factors; the courtyards and lack of greenery, an opportunity

arises where such spaces can be revitalized and generate value.

A courtyard has various positive impacts on the surrounding neighbourhood and residents when looking at a country like Denmark, where courtyards are common within the larger cities, they aid in the development of social relations and the maintaining of environmental quality ( Nelson, Alyse, et al. ). Yet, despite the presence of such spaces, and their ability to create a positive environmental impact, they do not support the residents. Via Caranchancel, The Yard will redefi ne the importance of courtyard spaces and their

contributions to the neighbourhood.

The project is devised to allow the resident buildings to become self-suffi cient in their water management and food production. As shown in Figure 2, these areas will be the main points of interest as they lack a direct engagement with the environment and have access to unused courtyard spaces. The fi rst stage involves the integration of sediment fi ltration. This form of fi ltration will be connected to the greywater produced by the residents and natural rainwater, thereby it is stored in containments within each building. The collected water will then be controlled independently according to the residents, and due to this, the fi lter will likely be a sediment fi lter as they are easy to manage and low cost, therefore the quality of water collected will be dependent on the courtyard residents.

The tanks will be made from steel as it lasts for many years and can also be recycled when it no longer functions (Neconnected). As the seasons change the amount of rainwater will vary, as such the tanks will also require fi ltered greywater from the residents. The courtyard is transformed into a garden landscape, capable of growing small plants and crops.

Large planting beds will be installed, and while the preparation will be simple, the results are reliant on

the dedication of the residents. As they will be using water from the filtration system, it is more economically beneficial and does not interfere with their existing lives (Ferguson, Donna.). As the courtyards grow and cultivate the plants, there will be an eventual stream of food production, allowing for partial self-sufficiency.

Each courtyard, while considered to be the property of each resident surrounding it, can be viewed as a communal private space; in the open yet simultaneously isolated from the public. The courtyard allows for the development of social relations and a positive mentality, not being affected nor controlled by the public. Additionally, while the resources produced are intended to be consumed by the residents, dependent on their needs it can also be profitable and sold to local stores, creating micro-economic benefits. The project creates a cycle, relying on each main stage in order to function correctly and produce desirable outcomes.

While this project has the main goal of creating efficient water management, food production and subsequent well being, by creating a well-balanced courtyard it is capable of generating value within the neighbourhood, giving Carabanchal a higher standard of housing.

Urban Rooftop Farming Circular economy applied to Buenavista, Madrid

by Marie-thé Pathe Pastor Alejandra Victorine

precipitation

surface runoff

evaporation condensation

closed greenhouse system

A concern which is becoming prevalent is how urban sprawl is causing soil and water pollution, mainly due

to people’s need for the transport of food and water

supply. Urban governments around the world are constantly facing an increasing demand by those who live in cities for small plots of land to grow vegetables or have a garden. However, these unoccupied patches are usually polluted by industrial activity which once took place on them. This is why a potential solution for authorities would be investing in rooftop gardens.

In the area of Madrid called Buenavista, this could work especially well because of all the vacant rooftops of apartment buildings. Additionally, due to the neighborhood being so densely populated with little space on the ground, it would be even more advantageous to incorporate rooftop gardening.

Rooftop gardens/ farming can help contribute to a reduction in the urban heat island effect as we incorporate more green spaces in an area, and they can also lead to less, and more effective use of energy by providing insulation and regulating temperatures in the winter and summer. Perhaps the aspect most important for energy effi ciency the rooftops would provide us with, would be its use of rainwater harvesting to supply the water demand of the gardens. Not only would the plants on roofs use the rainwater immediately, but the excess can be stored for later use. This is the part in which we see how rooftop farming can play a vital role in the circular economy. The crops and integration of re-used parts in cultivation could increase the sustainability of the gardens by using less resources in the consumption system.

Urban rooftop farming is a feasible way of reducing energy consumption and reducing the loss of water in the urban hydrological cycle in areas of cities like in Buenavista - a densely populated area with little space for gardens or farming on the ground.

Electronic Cadavre Exquis; Circular economy applied to E-waste

by Frantsuzov Mikhail

platform for change: e-waste re-purposing workshop.

(new users will explore the potential of these refurbished items and fresh models of treating what would be e-waste. a collective consciousness is building up) new residents e-waste

aquired value

(value can be monitized and the local workshops can act forprofi t, managing and maintaining the park) (new items gain new value, as well as added knowledge)

re-wiring & repair obsolete technology

(the workshop processes, fi xes, repairs and repurposes pieces. It is seen as a public market rather than a business. Group workshops are held to engage the community and educate about rethinking waste)

The dual goal of this project is to tackle the issue of E-waste and simultaneously, to create and promote an active public park in the neighborhood of Buenavista in Madrid.

As technology advances, it brings about a better and more effi cient communication, resource management and optimization among other benefi ts. However, the exponential growth in the advancement of technology also means more and more items grow obsolete at an equally increasing pace. In Spain, the problem of E-waste management and recycling has been around for some time. The article in El Pais dated from 2015 states that according to CWIT report on WEEE (waste electrical and electronic equipment), Spain was at the bottom of the recycling effort in Europe “ahead of only Romania and Cyprus.” Initiatives were sought on a large-scale level, through establishment of Integral Management Systems (SIGs) non-profi ts. However, these could not cope with the amount of E-waste in the country, handling only 67k out of the staggering 750k tons of waste. Another issue is that usually, E-waste is not treated locally at all, most of it is transported from developed countries to the developing ones.

Hence, to address these issues, the project proposes to deal with E-waste locally. And instead of tackling the problem of insuffi cient recycling, the project aims at

maximizing re-use and fostering a circular economy

prototype model which would be implemented on a small scale of a neighborhood and could be expanded horizontally to add other nods in the system across the district. Carabanchel has experienced changes in its demographic, from a working class neighborhood it has shifted towards a new hotspot for young professionals and creative entrepreneurs who seek cheap rents in the vicinity to the city center.

This means that even more types of E-waste will be accumulating in the district: in addition to the irreplaceable domestic devices and appliances, increasing dependence on cloud technologies equals constantly updating hardware plus new interface gadgets; even more electronic stuff.

The second vital part of the proposal is its community aspect. While the tendency of migration of the younger generation could bring about gentrifi cation and raise the real estate prices, the more positive impact is the diversifi cation of the community both in cultural and socio-economic terms. Hence, the physical location of the project plays an important role as a booster of interaction. The area of intervention is the underused interior courtyard in the heart of the Buenavista residential quarter. This void is re-imagined as a platform for exchange and acquiring knowledge. Formally a park, the courtyard is envisioned to become a center of the

community interaction based on exchange and reuse of obsolete technology – a 21st century localized marketplace. Here, the traditionally seen ‘natural’ habitat of the park coexists with the synthetic, instead of propagating banning the artificial dimension to our daily lives, the project promotes a more sensible and responsible use of technology by exposing its physical domain.

On the cultural level, the project introduces a slow shift in mentality, where people are encouraged to reuse and rethink rather than throw away.

The circular economy model is designed to help sustain the project and reinforce its values.

1)First, any piece of obsolete technology is collected individually by the neighbors: mobile phones, dishwashers, keyboards, wiring, toys (even sex toys, yes, they have a battery), tv screens, radios etc.

2)These would usually be considered E-waste and be thrown away or put in line for recycling. However, the next step is have them repaired, fixed, alternated or simply donated to the workshop established in the courtyard. This preliminary E-waste is classified and weighted. In accordance with this procedure, the owner collects a compensation in the form of a voucher for a different device that has been previously repaired. This is how a reuse cycle happens. But apart from this, schools, universities community centers, fablabs and galleries are encouraged to take part in the processing and re-thinking of these collected electronics.

3)Through a process of manipulations, these products gain an acquired value, a sort of cadavre-exquis reworked by multiple unknown hands and having a new functionality resisting a simple act of tossing away. This value can be in the shape of a physical functionality of the new tool, technical knowledge gained by the participants of the process, consciousness regarding environmental issues and waste management etc. The value can also be monetized (items sold to exterior actors) and the workshop will generate income4 to sustain the environment of the park and other infrastructural elements in the neighborhood. Hence, the communal effort of the residents will bring a real positive change in their environment.

4) The last piece to lock and kick start the mechanism are the new users. These users will be the ones appreciating the cycle that an otherwise useless piece of electronic equipment has gone through to end up in their hands. The last act of the cycle happens when their refurbished technology becomes obsolete and can be brought back to the exchanging platform-park for the community and the workshop to make use of.

Electronic Cadavre Exquis sees the discarded objects of mass consumption as an opportunity rather than disposable waste. To conclude, the project aims to tackle the issue of the E-waste management on a local scale, designing a conscious way to deal with obsolete technology in the setting of a courtyard park and, therefore, providing a lively platform for the neighborhood engagement and encouraging a slow mentality shift through gradual appreciation of the crafted nature and added layers to the items of the obsolete.