8 minute read

Artificial Food Coloring and its Effects on Human Health

Artificial Food Coloring and its Effects on Human Health Theo Camille Burden

Abstract:The use of artificial food coloring in our food has become more prevalent in our society. Some color additives are usedto enhance natural colors, add color, or help identifyflavor.Manyartificialfoodcolorings have been recognized by some to impose certain health risks. This paper evaluates the various types of artificial food coloring along with its potential effects on human health.

The use of artificial coloring dates all the way back to ancient times, around 300 BC, when wine was beginning to be artificially colored. Natural color additives from vegetable and mineral sources were used to color food, drugs, and cosmetics (paprika, turmeric, saffron, and iron for example). Over time discoveries of synthetic organic dye started to emerge with the first discovery being mauve by British chemist, William Henry Perkin, in 1856. As more and more discoveries of dyes emerged the United States began the federal oversight initiative in 1881 with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA). Their Bureau of Chemistry began research on the use of added colors in food with cheese and butter being the first foods the federal government authorized the use of artificial coloring for. Artificialfood coloringwas morewidespread in the U.S. by the 1900’s, even though not all were harmless. Most color additives were used to hide the imperfections in food through added lead, arsenic, and mercury. As a result, Congress passed the Food and Drug Act in 1906 that prohibited the use of poisonous coloring or using color additives to hide the imperfections in food. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was responsible for enforcing the Food and Drug Act of 1906 in 1927. Four years later, in 1931, there were 15 colors approved for the use of food that have not been mixed or chemically reacted with any other substance, some of which are still use in our food today, such as, Blue No. 1, Blue No. 2, Green No. 3, Red No. 3, Yellow No. 5, and Yellow No. 6.1 As of recently there are nine FDA approved color additives, including those previously mentioned, along with Orange B, Red No. 2, and Red No. 40.2 Color additive derived from petroleum are found in several food products, such as breakfast cereal, snacks, beverages, vitamins, and products advertised for children. The FDA approved artificial food coloring derived from petroleum in order to enhance the appearance of foods. For example, some fresh oranges are dipped in coloring to brighten them up. It’s also said to be that the cereal “Cap’n Crunch’s Oops! All Berries” has the most color additives with 41 mg of dye.3 Over time some of the dyes have posed as health risks and some were even banned in certain continents. In 2010 the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) in Washington, DC did a report where they found that “the nine artificial dyes approved in the United States likely are carcinogenic, cause hypersensitivity reactions and behavioral problems, or are inadequately tested”.4 There have been studies to show how the effects of dye consumption can have an impact on a child’s behavior. Although, the studies are inaccurate since the dye dosage the children are given are far less than the amount of dye being consumed daily. The typical daily dosage of Red No. 40 is 10 mg, according to an exposure assessment by the FDA in 2014, whereas people consume as much as 52 mg of a single dye in one day. With trying to observe the effects artificial food coloring has on a child’s behavior there

are two general studies that come about, the studies that gave children food dye and see how they respond, or, the studies that eliminate certain dye containing foods from a child’s diet and observing their reaction. Some of the results of the studies showed that even the smallest amount of artificial dye, smaller than a cupcake, can spark adverse behavioral changes. Not only in children with behavioral disorders, but those without. These studies believe that artificial dyes can trigger ADHD symptoms which can be altered by dietary changes. The overall conclusions of these studies being that behavioral improvements for some children is possible by either eliminating food dyes completely or taking on a broader diet to eliminate them.5 Even though these studies conducted found somewhat of a behavioral change, this is not the case in all children. Some target “elimination diets” for artificial food since “they serve no health purpose whatsoever”, says, Michael Jacobson, director of the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CPSI).6 Although, in a small study with 26 children with ADHD, 73% of the children experienced “a decrease in symptoms when artificial food dyes and preservatives were eliminated”.7 There are many debates surrounding the topic of artificial food coloring and behavior problems in relation to ADHD as a result of insufficient data conclusions. As well as the effectsartificialcoloringhasonhyperactivity varies from child to child.8 Along with hyperactivity there’s a growing concern that some color additives contain a

*A substance capable of causing cancer in living tissue. † Free benzidine is an organic based manufactured chemical that was previously used to produce dyes for cloth, paper, and leather. chemical that could increase the risk of bladder cancer. There have been three color additives that have been identified as containing a human and animal carcinogen*. FDA and Canadian government scientists found that Red No. 40, Yellow No. 5, and Yellow No. 6 have some containments of carcinogen. It was found by the FDA in 1985 that the “ingestion of free benzidine† raises the cancer risk to just under the “concern” threshold (1 cancer in 1 million people)”.9 Although the odds might appear minimal, the FDA only primarily test free benzidine, but overlook the bound benzidine. The dangers in bound benzidine are much greater than free benzidine since it comes in greater amounts, “so we could be exposed to vastly greater amounts of carcinogens than FDA’s routine tests indicate” (Michael Jacobson).10 Even though this is a concern brought by the CPSI, the FDA are unable to comment on topics under review so their position towards the issue is unknown. Moreover, the FDA has established legal limits to regulate cancer-causing containments in certain dyes. Although their efforts were to help prevent this health concern, the FDA didn’t consider in their tests the increased risks dyes have on children. Children consume much more artificial dyes than adults and they are more sensitive to carcinogens. Another risk that the FDA is failing to realize in their study on artificial dyes is the effect they have on the human body collectively, rather than independently.11 Since the use of artificial dyes are mainly advertised towards children, they are consuming large dye amounts of various types. For example, if a child were to

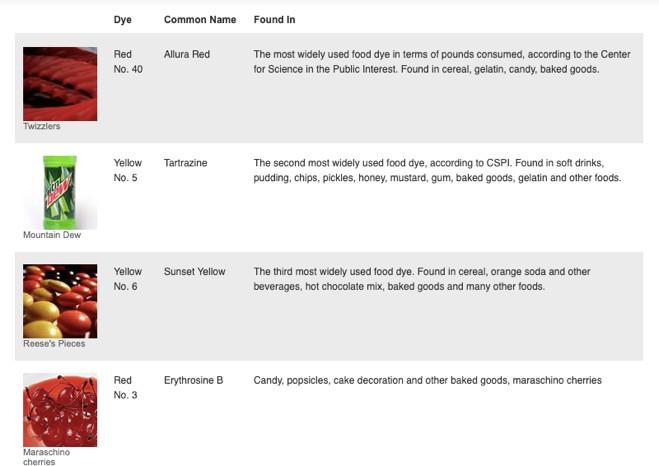

eat a pack of jellybeans, they’re consuming a large amount of Red No. 40, Yellow No. 6, and Blue No. 1.12 As a result, it would be more beneficial in their lab work to test the effects of the consumptions of multiple color additives. With the growing concern that artificialdyes do not improve the safety or nutritional value in foods it has come to the attention of Michael Jacobson that, “all of the currently used dyes should be removed from the food supply and replaced, if at all, by safer colorings”.13 There has been an increase effort in trying to regulate artificial coloring. Manufactures overseas are considering using natural dyes that are made from beets and turmeric. The United States is also considering using natural dyes rather than artificial, although the only thing preventing them from doing so is how expensive natural dyes are and how they are less stable than artificial dyes.14 Meanwhile, still disturbed by the health concerns coloring additives have the Center for Science in the Public Interest is requesting that the FDA ban the following artificial food dyes in Figure 1 and in Figure 2.15

1 Barrows, Julie N., et al. "Color Additives History." Edited by Sebastian Cianci. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 3 Nov. 2017, www.fda.gov/industry/color-additives/coloradditives-history. 2 "Color Additives Questions and Answers for Consumers." U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 4 Jan. 2018, www.fda.gov/food/food-additivespetitions/color-additives-questions-andanswers-consumers. 3 Hennessy, Maggie. "Purdue Study: Artificial Dyes Highest in Beverages, Cereal, and Candy." Food Navigator, 7 May 2014, www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/ 2014/05/08/Purdue-study-Artificial-dyes-highestin-beverages-cereal-candy. 4 Potera, Carol. "Diet and Nutrition: The Artificial Food Dye Blues." Environmental Health Perspectives, Figure 1: List of Artificial Food Coloring the CPSI hopes the FDA will ban16

Figure 2: List Continued

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PM C2 957945/. 5 Lefferts, Lisa Y. Seeing Red. Edited by Michael F. Jacobson and Laura MacCleery, e-book. 6 Woodman, Dawnielle. "FDA Probes Link between Food Dyes, Kids' Behavior."

Interview conducted by April Fullerton. National Public Radio, 30 Mar. 2011, www.npr.org/2011/03/30/134962888/. 7 Bell, Becky. "Food Dyes: Harmless or Harmful?" Healthline, 7 Jan. 2017, www.healthline.com/nutrition/food-dyes/. 8 Office of Food Additive Safety, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition,

Food and Drug Administration. "Artificial Food Color Additives and Child

Behavior." Environmental Health Perspectives, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ articles/PMC3261955/.

9 Potera, Carol. "Diet and Nutrition: The Artificial Food Dye Blues." Environmental Health Perspectives, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC29579 45/ . 10 Potera, Carol. "Diet and Nutrition: The Artificial Food Dye Blues." Environmental Health Perspectives, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC29579 45/ . 11 Kobylewski, Sarah, and Michael F. Jacobson. "Food Dyes: A Rainbow of Risks."

Center for Science in the Public Interest, PDF ed. 12 Woodman, Dawnielle. "FDA Probes Link between Food Dyes, Kids' Behavior."

Interview conducted by April Fullerton. National Public Radio, 30 Mar. 2011, www.npr.org/2011/03/30/134962888/. 13 S., Kobylewski, and Jacobson M. "Toxicology of Food Dyes." PubMed, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23026007. 14 Woodman, Dawnielle. "FDA Probes Link between Food Dyes, Kids' Behavior."

Interview conducted by April Fullerton. National Public Radio, 30 Mar. 2011, www.npr.org/2011/03/30/134962888/. 15 Woodman, Dawnielle. "FDA Probes Link between Food Dyes, Kids' Behavior."

Interview conducted by April Fullerton. National Public Radio, 30 Mar. 2011, www.npr.org/2011/03/30/134962888/.