5 minute read

KAREN KAUFMAN

KAREN KAUFMAN

Editor’s Note: You can find Part I of Karen’s experience with this research-informed strategy in “Think Differently and Deeply Volume 3.”

“ H ave we learned this before?” is one of the most unsettling questions a teacher can hear from students at the end of what was thought to be a successful school year. It is also the first line of an article I wrote in 2017 for Volume 3 of the CTTL’s “Think Differently and Deeply” publication. This article, “The Science of Forgetting and The Art of Remembering,” described how a colleague and I implemented spaced repetition and interleaving in our Algebra 2/Trigonometry classes.

If you are thinking, hold on, topics in math courses don’t lend themselves to spacing and interleaving, you are right. But this might be because you are thinking of the math classroom you are used to. Traditionally, math topics are presented linearly, each building on the prior one — envision a textbook’s table of contents that a class spends the year working through. However, I was at a point in my teaching career when I could no longer deny the dissatisfaction that students and I both felt at the end of a school year when it was time to prepare for the final exam.

Student stress and lower-than-antici- pated final exam grades had become an expected end of year norm. The final exam seemed to be a measurement of how well students crammed for the exam rather than how well they had learned through- out the year. And, our math teachers were spending the better part of each new school year revisiting prior year’s content to make up for students forgetting much of what they had learned.

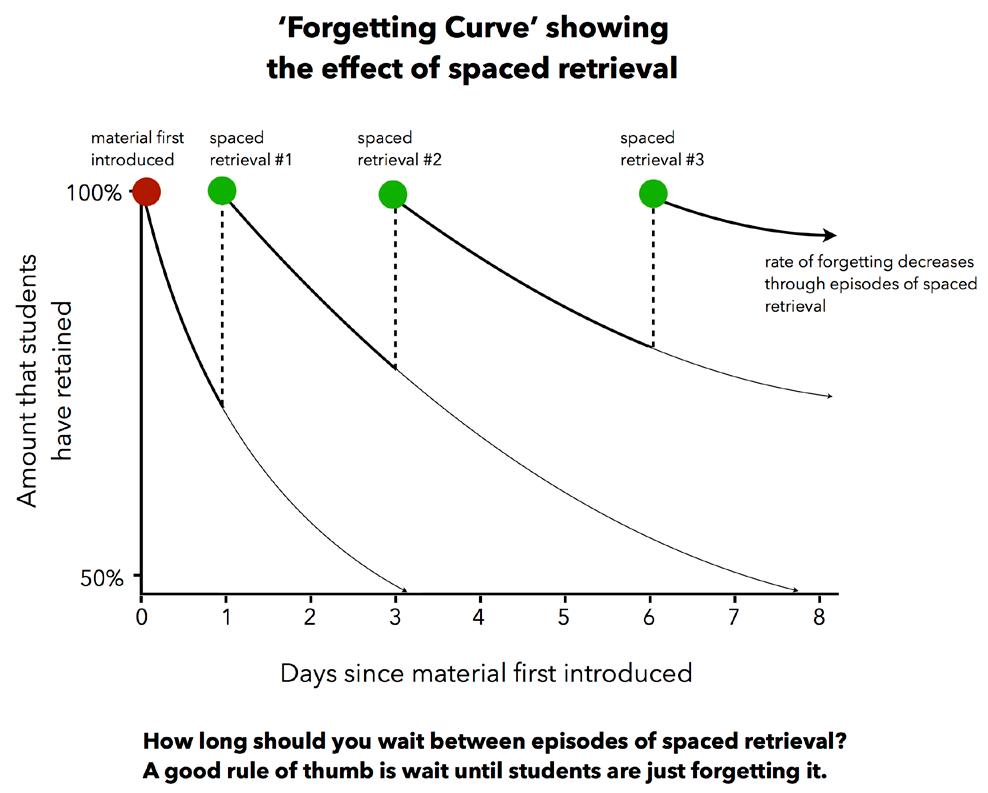

Since math is a subject that continues to build on prior knowledge, this was a debilitating cycle for all involved. What’s more frustrating is that we knew why the forgetting was happening. As researchinformed educators, we were familiar with Hermann Ebbinghaus’ study of memory retrieval aptly named the “forgetting curve.” The forgetting curve has the shape of a decreasing exponential-like func- tion with the greatest decline in memory (steepest portion of the curve) occurring within the first few hours or days of learn- ing a new topic. The antidote to forgetting was to revisit the topics at appropriatelyspaced intervals.

So, after years of frustration, and armed with this compelling research, my brave colleague and I decided to try spacing and interleaving. We completely deconstructed and reorganized our Algebra 2/Trigonome- try course to provide ongoing and multiple

opportunities for student exposure to new content. We abandoned the linearly presented order of topics in our textbook and instead connected subtopics based on their relation to other subtopics.

We peppered topics strategically and repeatedly throughout the course. To fully establish interleaving and spacing, we chose to lag all homework by establishing a weekly homework review sheet. Homework was assigned based on ideas presented in prior units. A topic would never appear on a weekly homework review until it had been practiced extensively and repeatedly in class. Assessments were also lagged often several weeks after a topic was first taught and after students had multiple practice opportunities.

At the end of my 2017 article I promised to update readers on the outcome of this new pedagogy. As a math teacher and numbers person, the plan was to collect quantitative data on student final exam grades (in precalculus) from year to year as a way to determine if students coming from Algebra 2/Trigonometry were forgetting less. We collected and analyzed the data and found that final exam scores were in fact somewhat higher since we implemented spacing and interleaving.

However, these outcomes can’t be relied on as statistically significant since the composition of students in our classes vary from year to year. In this past year, there was an unusually large contingent of precalculus students who came from Honors Algebra 2/Trigonometry. Therefore, it is unreasonable to state definitively that the increase in exam scores was related to our new methods.

It turns out, perhaps the most compelling data to support spacing and interleaving is not quantitative at all. Instead, it is the qualitative feedback from students and

teachers. Students who experienced spaced repetition and interleaving in their math classrooms were happier and less stressed throughout the school year and especially during the final exam period. We know from a 2014 research study on happiness by the CTTL and Research Schools International that there is a statistically significant correlation between happiness and students’ GPA from elementary school through high school. 1

One of our goals then as math teachers should be to generate happier more confident math students. In that regard, I do believe the data is compelling. This past year, four of our math courses adopted spacing and interleaving. At the end of the year, we surveyed students asking them specifically what they thought about their weekly review homework, and the interleaving of course content. Student feedback was overwhelmingly positive and only a few students surveyed said that they preferred a more traditional approach

to learning and homework. Here’s a small sampling of student feedback:

“I really like the weekly review homework because it helps me quickly figure out what I know and what I don’t, and then I can get help with the things I don’t know and carry those skills over to the next assignment.”

“I really like the review homework because I feel like I am not reaching for help every time we encounter something older in class or during practice. It keeps me actively thinking about concepts that in other subjects, we would forget about in the next year after the summer. It allows me to manage my time better as well because I can space out the time I will need to complete it and work on homework when I have the time. As stated before, I truly feel like I benefit from this system more than previous ones.”

Beginning in the 2019-2020 school year, all of our Middle and Upper School Math courses will adopt some form of spacing and interleaving. And we will design an improved action-research study to measure the impact. Over the coming years, we will continue to observe and report on the effects of this new pedagogy on student learning, particularly on retention from year to year, and on student attitudes toward math. Stay tuned... again.

Karen Kaufman (kkaufman@saes.org; @karen_ kauf) is Head of the Math Department and an Upper School Math teacher at St. Andrew’s.