6 minute read

The battle for parental rights and government oversight remains alive

By Natasha Sokoloff

parents involved in looking at school library materials or being involved in their kid’s education,” Sen. Peake said.

Advertisement

Huguenot

High School’s

library functions as a type of escape from the pressures of student life, a place where students can come and “chill out,” as librarian Kevin Murray puts it. He doesn’t give out grades or assign homework, so it makes sense why so many students like spending their time there, a serene space away from the bustling halls of high school.

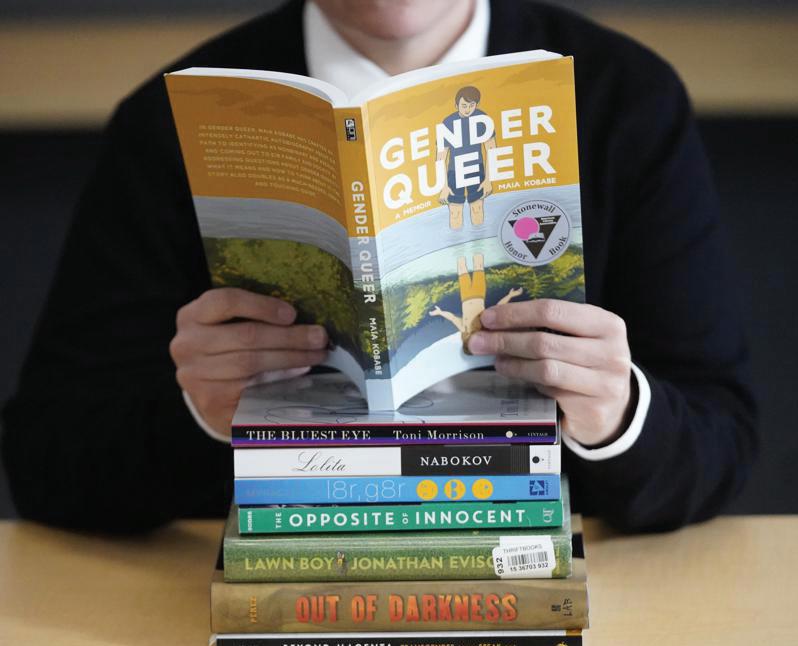

But underneath the familiar silence that envelops all libraries, a war rages over the books that are allowed to be placed on the shelves. Public schools across the nation have become a focus on the debates surrounding parent and government involvement in students’ education, from picking novels to the curriculum taught in classrooms.

The culture wars reached Virginia’s divided General Assembly during this election-year session. Republicans introduced legislation aimed at increasing parental involvement in public schools through cataloging and flagging books in libraries; increasing parental permission requirements; allowing parents to restrict their child’s access to certain books; and parental review of public schools curriculum.

Most of the parental rights bills passed the Republican-controlled House but then failed along party lines Feb. 16 in the Senate’s Education and Health Committee, where Democrats are in the majority. The actions center on HB1507, HB1803 and HB1448 that intended to increase parental involvement in curriculum. And although these bills may have been killed, the polarizing battle for parental rights and government oversight remains alive. Mixed sentiments among parents, teachers, librarians, politicians and experts seem to indicate that it’s not going away anytime soon.

The battles in Virginia are a reflection of tensions nationwide, perhaps most notably in Florida, where the Parental Rights in Education Act, commonly known as the Don’t Say Gay act, was passed in 2022. Under the law, classroom discussion and instruction in public schools about sexual orientation or gender identity is prohibited from kindergarten to third grade. Discourse over banning books isn’t new to school boards across the nation, but they’ve increased in the context of the debate over parental rights.

“You know, back in the old days, when I was younger, with parents there was kind of like this blind faith,” Mr. Murray said. “Of ‘OK, go to school, learn this, learn this.’ There weren’t that many questions asked as to what you’re being taught.”

Patrick Miller, president of the Henrico Education Association and an English teacher at Highland Springs High School, said he believed educators in the county saw parents as equal partners in their children’s education. To Mr. Miller, too much parental involvement can signal a lack of trust in teachers.

“While any parent should have the right to ask specifically what their kid is reading or learning in school, I would appreciate trust from parents when it comes to my professional judgment, having studied for a master’s degree in teaching literature and writing and reading strategies to students,” he said.

In his decade of working for Henrico County Public Schools, Mr. Miller said he had never known a book to be outright banned. However, as far as challenges to curriculum and challenges to books, he said he has seen that all over, not just concentrated in one location.

“A lot of times, communities have different points of view on how they handle things, from southwest Virginia to the Tidewater area,” said Shane Riddle, the Virginia Education Association’s government relations and research director. “That’s why school board members are elected – to represent not only the parents but all community members.”

Richmond School Board member Jonathan Young said he fully supported the parental rights bills and believes that though schools have been better at emphasizing the central role of parents, they are still too infrequently prioritized.

“I really truly wish more parents in K-12 across this country would invest the kind of labor and time to scrutinize what their students are learning,” he said.

And school board members have a duty to consider families’ wishes and needs, Mr. Young said.

“The families have made a conscious decision to entrust us as a school district with protecting and educating the most important thing in the world to them: their children,” he said.

Although he does not think that trust in teachers and pushing for parental involvement in curriculum are mutually exclusive, Mr. Young said that what parents are seeking for their children is the most important consideration.

“You have to meet the customer where they’re at,” he said.

As a father of three school-age daughters, Mr. Murray, the Huguenot High librarian in South Richmond, has his opinion on how involved he should be in their education.

“Of course, yes, parents should have a say,” he said. “And that’s why there’s school board meetings, and that’s why there’s PTAs.” Parents have always talked with teachers and principals, he said, so in that sense a feedback system has always been in place.

However, excessive oversight will eventually be damaging to students, he said.

“Gotta leave it to the experts,” Mr. Murray said. “A lot of parents are not educational experts. A lot of people in school boards are not either.”

Sen. Mark Peake, R-Lynchburg, who voted in favor of three parental rights bills regarding curriculum, said he wasn’t surprised that they failed – he thought the bills wouldn’t get past the subcommittee level.

“The Democrats don’t seem to be that excited about having

Mr. Miller said most teachers have parents sign the syllabus at the beginning of the year, and they can read the curriculum on it.

“But, I mean, if somebody wants to come in and catalog all of the books in my classroom library, they can be my guest,” he said. “That’s quite a lot of work that I wouldn’t be getting paid for.”

One Republican-authored bill would require the Department of Education to make recommendations on adopting model policies for the selection and removal of public school library materials, “in consultation with local school boards, public school librarians, parents of public school students, and other interested stakeholders.”

Del. Timothy Anderson, R-Virginia Beach, introduced HB1379, which would have required librarians to identify books with graphic sexual content and put them in an online compilation for parents to know that they’re there, and then give parents the right to opt-out.

“If I’m a parent, I should have the right to exclude my child from having access to these books,” Mr. Anderson said during the Feb. 15 committee hearing.

Speakers from conservative religious lobby groups such as Pro-Family Women, based in Arlington, and the Family Foundation, headquartered in Richmond, expressed their support for the legislation during the committee hearing.

Susan Muskett, president of Pro-Family Women, called it the bare minimum.

“It’s not banning the book,” said Todd Gathje on behalf of the Family Foundation. “It’s just simply saying, ‘Let’s create a list of graphic sexual material that any reasonable-minded parent would not want their child to have at any level of school.’”

Speakers on the other side, however, viewed it as redundant to the policies already in place.

“Librarians regularly partner with parents,” Nathan Sekinger, president of the Virginia Association of School Librarians and librarian at T. Benton Gayle Middle School in Fredericksburg, told the committee. If a parent’s concern requires more than a conversation, then they can challenge a book using the school board’s approved process, he said.

Virginia school boards already have the authority to make these decisions, and to ensure parental notification and review of any instructional material that includes sexually explicit content, according to a law passed last year. In addition, school divisions have publicly available websites that show every book or material in its library, Mr. Sekinger said.

Since Mr. Murray started his position as the high school librarian in 2017, he has never been challenged on any of the books the library makes available.

“I’ve been lucky,” he said.

Mr. Murray said he opposes banning books, but believes there are some titles inappropriate for children.

“Because every high school kid, even though they’re roughly the same age, they’re not the same maturity level,” he said. “So some kid who’s 16 can handle or understand a book dealing with sexuality, or dealing with violence in a manner that’s more like an adult, and some kids who are 17,18 won’t be able to handle it that well.”

The selection of books for a school system is decided based on a variety of factors, from selections of vendors and publishers to student recommendations, Mr. Murray said. But the question of who determines if a book is appropriate can lead down a slippery slope, he said.