72

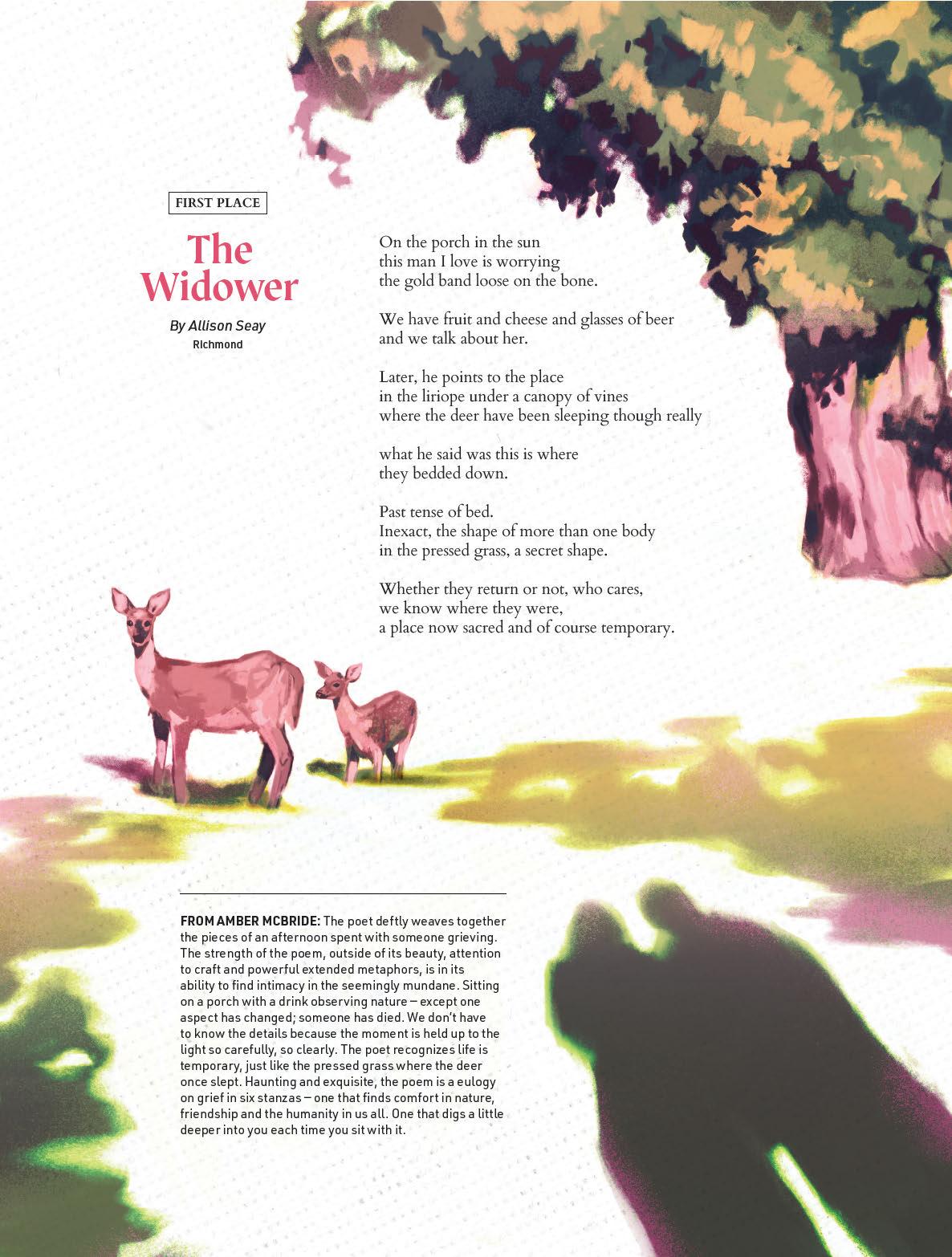

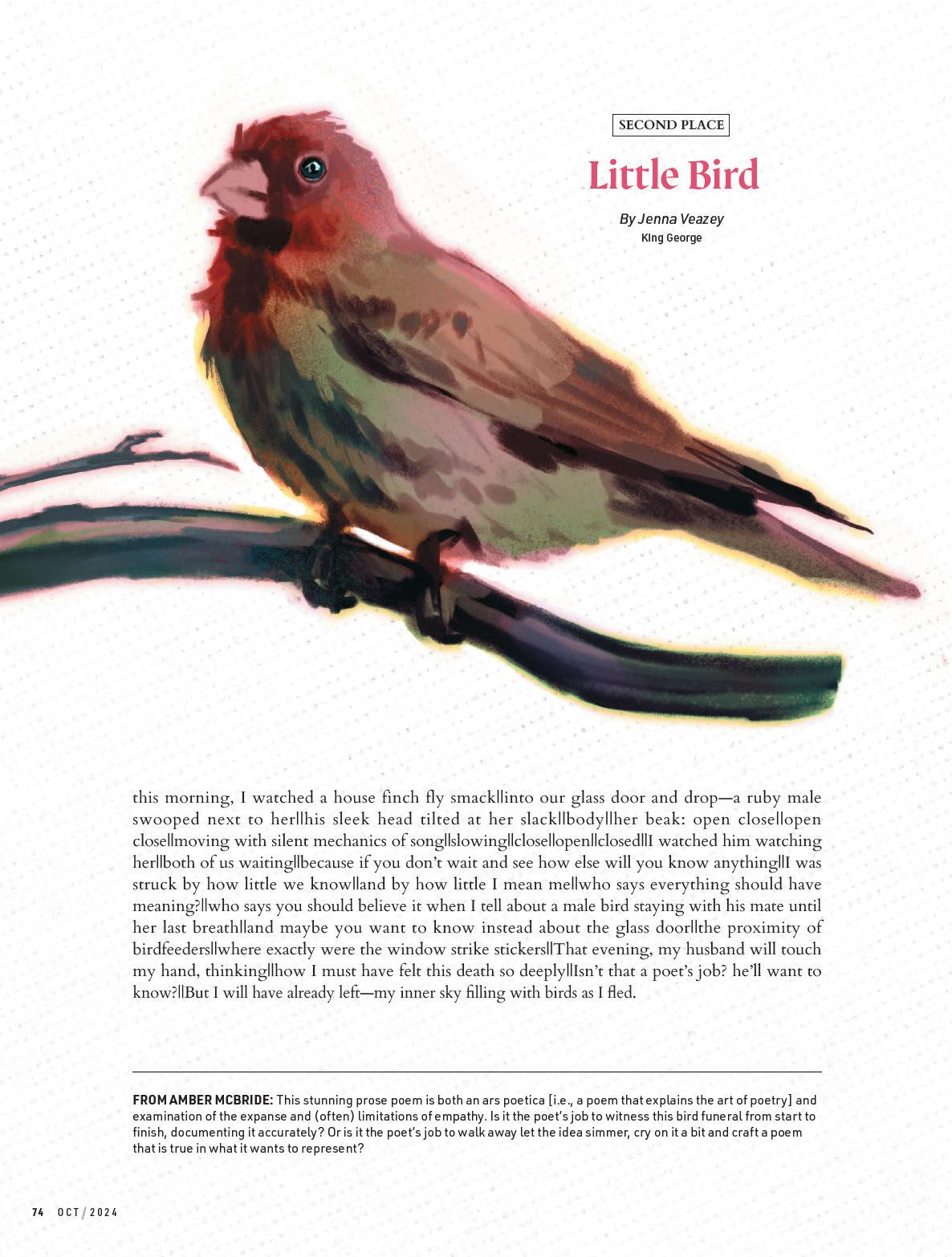

Presenting the winners of the 2024 Shann Palmer Poetry Contest

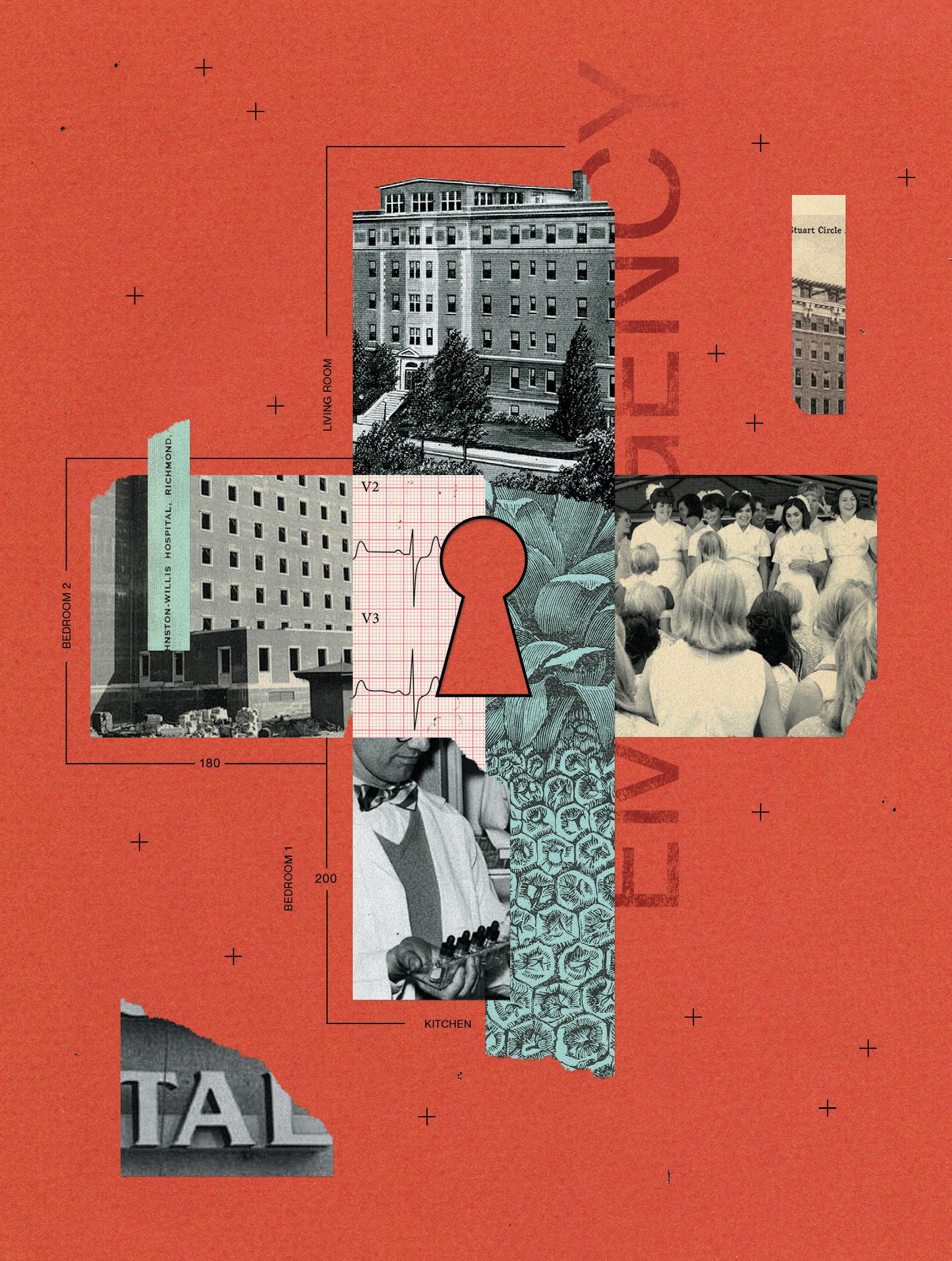

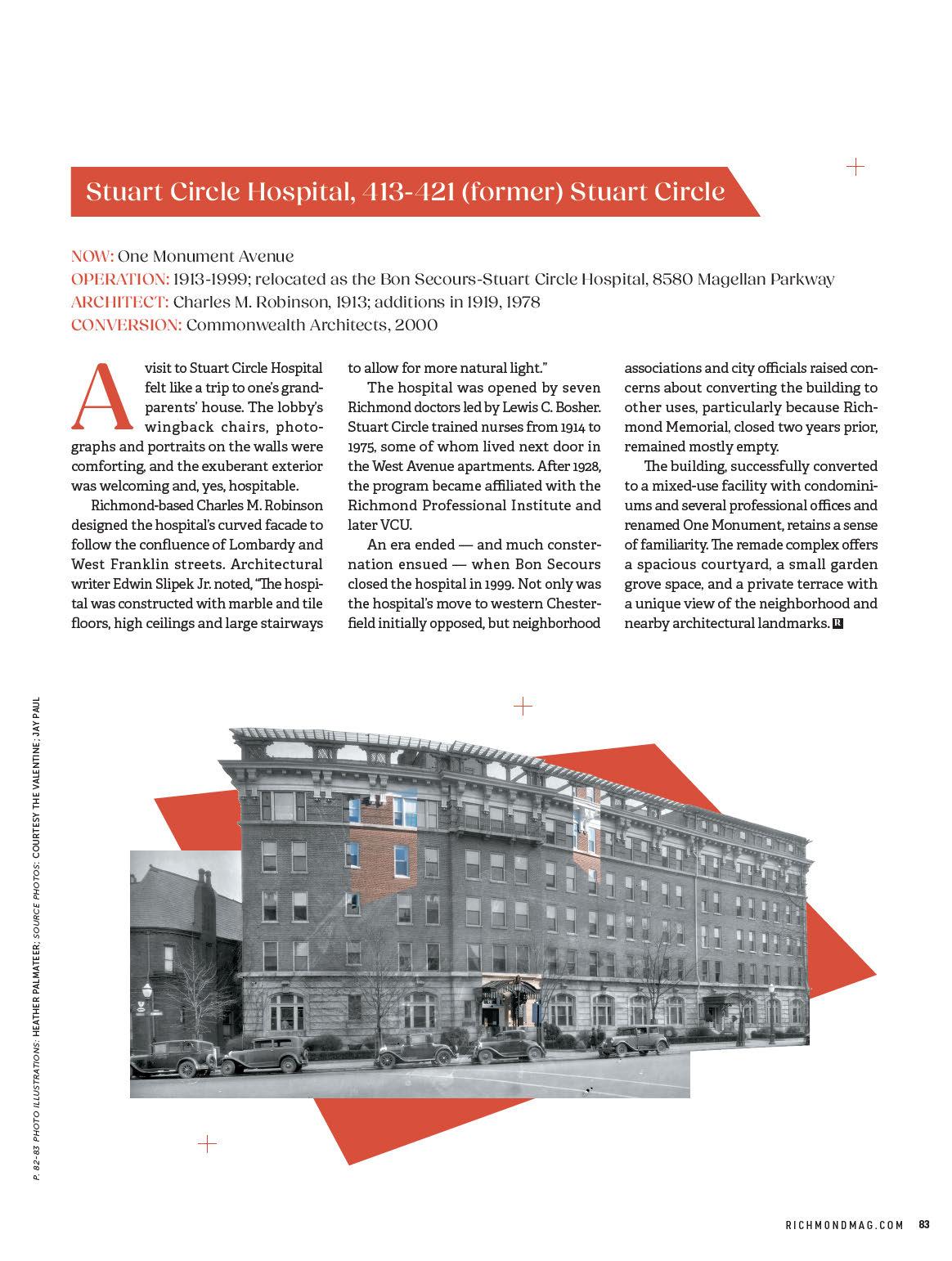

In a quirk of coincidence, adaptive reuse has seen several Richmond medical centers become residences

By Harry Kollatz Jr.

VOTE A guide to the 2024 Richmond elections By Sarah Huffman, Rachel Kester, Laura Anders Lee, Mark Newton and D. Hunter Reardon

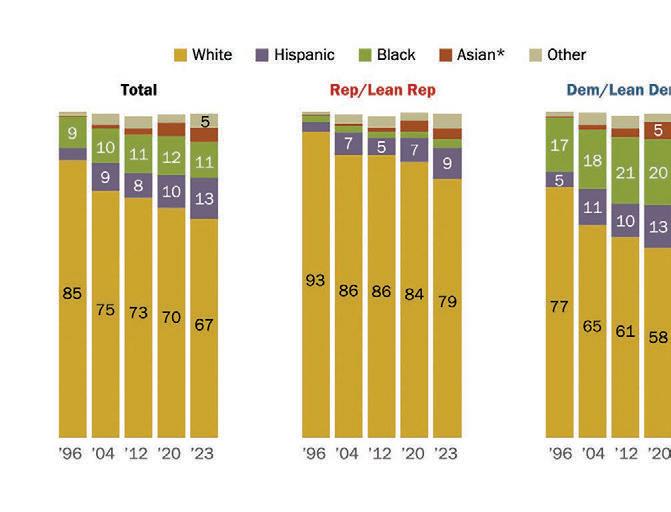

(Percent of registered voters)

*Estimates for Asian voters are representative of English speakers only.

member of Alpha Kappa Alpha, the oldest Black sorority in the United States.

“The Divine Nine has national, if not global, outreach,” Wrighten says. “They do community-based work — it started in Black communities, in churches. These sorts of organizations made a difference in the Civil Rights Movement, making strides towards equality. They’ve been mobilizing since they were created, and voting is one of their biggest missions.”

The Divine Nine has thrown their weight behind Harris, which Wrighten says puts parts of the South back into play for Democrats. In states like Virginia, where the electorate is diverse and the Divine Nine is well-organized, the dri of Black voters toward Trump — along with his chances of winning the election — could be reversed.

Wrighten emphasizes that Black women voters are particularly influenced by the presence of a woman of color — Harris’ parents were born in Jamaica and India — at the top of a national ticket.

“There’s a lot of excitement surrounding Kamala Harris’ nomination, a reckoning that Black women have come through in support of the Democratic Party in many ways,” she says. “There’s an idea that, ‘It’s about time.’”

Wrighten also suggests that Black women voters prioritize democracy, and

Data courtesy Pew Research Center

she says that by contesting the 2020 election and making unforced remarks about “dictatorship,” Trump alienates those voters.

“In the ideal version of democracy, you have inclusion, and everyone has a voice,” says Wrighten. “There’s an expectation that with more democracy, there will be more equality. That’s the hope of marginalized communities.”

‘PEOPLE FROM EVERYWHERE’

Michael Paalberg, professor of Latin American politics and the politics of immigration at VCU, says there is one very important thing to remember about Hispanic voters.

“Latinos are not a monolith,” he says. “Latinos are people from everywhere, from Argentina to Cuba.”

The 2020 Census has the Latino population in Virginia at 10.5%, while the average nationwide is 16.3%. Paalberg also indicates that Latinos in Virginia may be more likely to vote like those in their community.

Trump has made “migrant crime” a focus of his campaign, apparently linking the rise in crossings at the southern border with criminal activity, though there is scant evidence for this association. Paalberg, however, says that it doesn’t mean Trump’s rhetoric will drive away all Latino voters, whose voting

pa erns are difficult to analyze.

“In more conservative areas, a lot of Latino voters are more conservative. In liberal areas, they are more liberal,” he says. “Latino does not equal migrant — they don’t necessarily identify with newcomers, who aren’t from areas near where they live.”

Nationwide, Harris has retaken the lead among Latino voters. She is still polling below Biden’s 2020 numbers, but a BSP Research poll showed Harris beating Trump 55% to 37% among that group just days a er Biden dropped out of the race, marking a 27-point swing in the Democrats’ favor.

The classes taught at VCU by Amanda Wintersieck, director of the Institute for Democracy, Pluralism, and Community Empowerment, focus primarily on elections and the intersection of media and politics.

“The American public doesn’t know [Harris],” Wintersieck says. “Even [those of us who follow politics] are still learning a lot about who she is as a person and a candidate.”

Youth voter engagement, says Wintersieck, is a historic problem — one she hopes does not continue in November.

An immediate and obvious boon for the revamped Democratic ticket is the fact that Harris is 59, a spring chicken compared to the octogenarian Biden, and nearly 20 years younger than Trump. Before Harris took over, independent voters were in lockstep with Republicans on whether Biden’s age impacted his ability to lead.

Upon the news of Biden’s decision to drop out, an NPR/PBS News/Marist poll indicated that 43% of voters under 29 were “more likely to vote in November,” against 10% who were less likely. Polls between Trump and Harris among young voters vary widely, but Wintersieck says there may be an obvious reason for increased engagement. “Perhaps, it’s an effect of having a younger candidate on the ballot,” she says. R

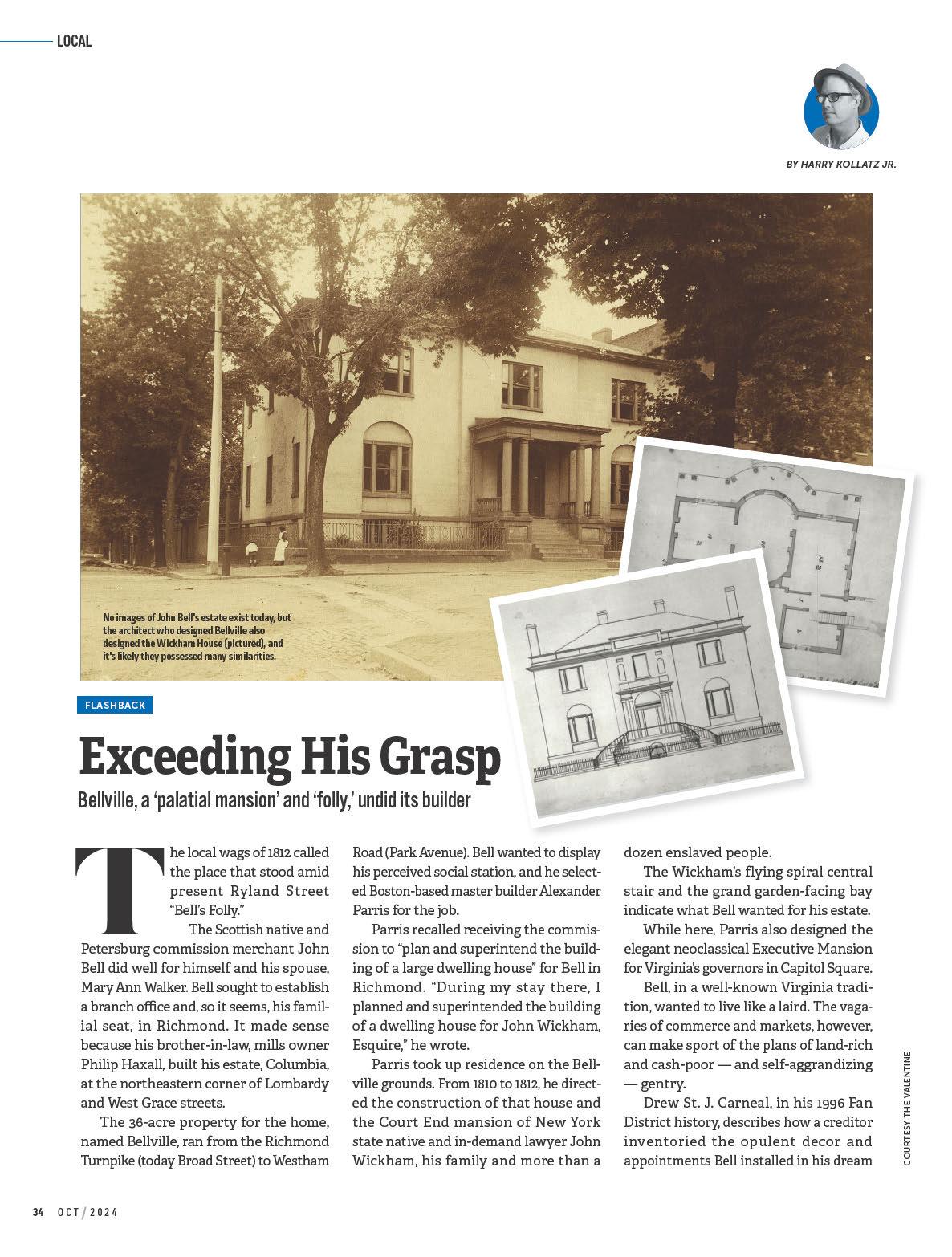

home: mahogany furnishings, fine china and crystal, an expensive “Piano Forte Musick,” two “Shakespear” prints and a painting of St. John. Another observer remembered a “magnificent chandelier of cut glass” that dominated the main hall. What Bellville may have looked like can only be discerned from Parris’ other surviving Richmond houses. No drawings of “Bell’s Folly,” as Carneal coined it, are known to exist.

A somewhat clumsy description appears in the Oct. 11, 1841, issue of the Richmond Courier. A double flight of curved marble stairs led to the entranceway. “The foundation walls were of immense thickness, the first floor resting on arches like the casements of a fortification,” the Courier writer said in an attempt to visualize the building for readers. The “ascending walls went up a massive inclosure, upon which rested a heavily built and substantially braced roof of stalwart timbers. Underneath the dining room floor and connected by narrow stairways were solidly constructed wine cellars and other receptacles for household goods of value.”

The cellar and receptacles contained 20 dozen bo les of Madeira and 60 gallons “of old rum.” The drink may have eased (or caused) some of the financial pain that followed.

While Bell didn’t end up completely losing his place, family kept him housed for a while. William Haxall, the brother and business partner of Bell’s brotherin-law Philip, bought Bellville. The Bells stayed there in their straitened circumstances until December 1816 when the Haxalls sold the mansion and 20 acres to John Mayo Jr.

The Mayos were one of Richmond’s first families and prospered from investments out of the tolls taken on their bridge to Manchester, known as the 14th Street Bridge. The Mayos then lived nearby in a rambling country villa called the Hermitage (as in the road name).

The Bells packed up for Cou s’ Addition, north of East Broad. They moved into a new brick house at what became 506 E. Leigh St., which they rented from William Mann on the terms of five years for an annual rent of $400. Anglican minister William Cou s profited more from operating a Richmond-to-Manchester ferry than preaching and assembled property that the city annexed (hence, the term “addition”).

Mann, serving as deputy marshal of Virginia, purchased the entire square along Leigh in 1810. He placed the residence in the square’s middle, surrounded by gardens. That site is today buried beneath the Altria Center for Research and Technology and ki y-corner from the bunker-like Coliseum entrance where Leigh Street slides beneath Fi h Street.

Despite the accommodation, Bell’s debts overwhelmed him and, around 1820, he died broke.

Meanwhile, the Mayo fortunes rose. Bellville suited Philip Jr.’s sense of advancement. The place was suited for entertainment and there on May 11, 1817, his eldest daughter Maria DeHart was wed. Maria by accounts fit the designation of a “belle”: desirable for her appearance and connection to wealth, ability to play with notable skill the harp and harpsichord and knack for foreign languages.

The groom, already a national military hero, was Dinwiddie County native Brevet Major Gen. Winfield Scott. The newlyweds moved to a Mayo house in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, closer to Sco ’s

Northeastern command.

Of the Scotts’ seven children, both sons died young as did two daughters. Maria, separated from her frequently campaigning military husband, suffered depression and sickness. In the 1830s, she chose to live abroad for health reasons until she died in Rome in 1862. They and their eldest daughter, Cornelia, are buried at West Point Cemetery, New York.

Descendants inherited the Richmond properties that became Sco ’s Addition. Belleville Street, the section’s westernmost thoroughfare, may have been named with either a misspelled sense of residential history or an appreciation of Maria. The legacy, knowingly or not, continues on the street with the 2024 completion of the six-story, 125-unit Belleville Apartments designed by Richmond's 510 Architects.

Philip Mayo died in May 1818 at age 58. His widow, Abigail, remained in the “palatial mansion,” of Bellville, as the Courier described it, until an 1841 fire. The former Mayo estate of Hermitage went disused and burned in 1857. Later there arose the Union or Broad Street Station, now home of the Science Museum of Virginia.

The place in Coutts’ Addition to which the Bells retreated entered Richmond lore as the haunted Hawes House with appearances of a certain “Grey Lady.” You can read more about the Hawes — and the associated ghost story — at richmondmag.com. R

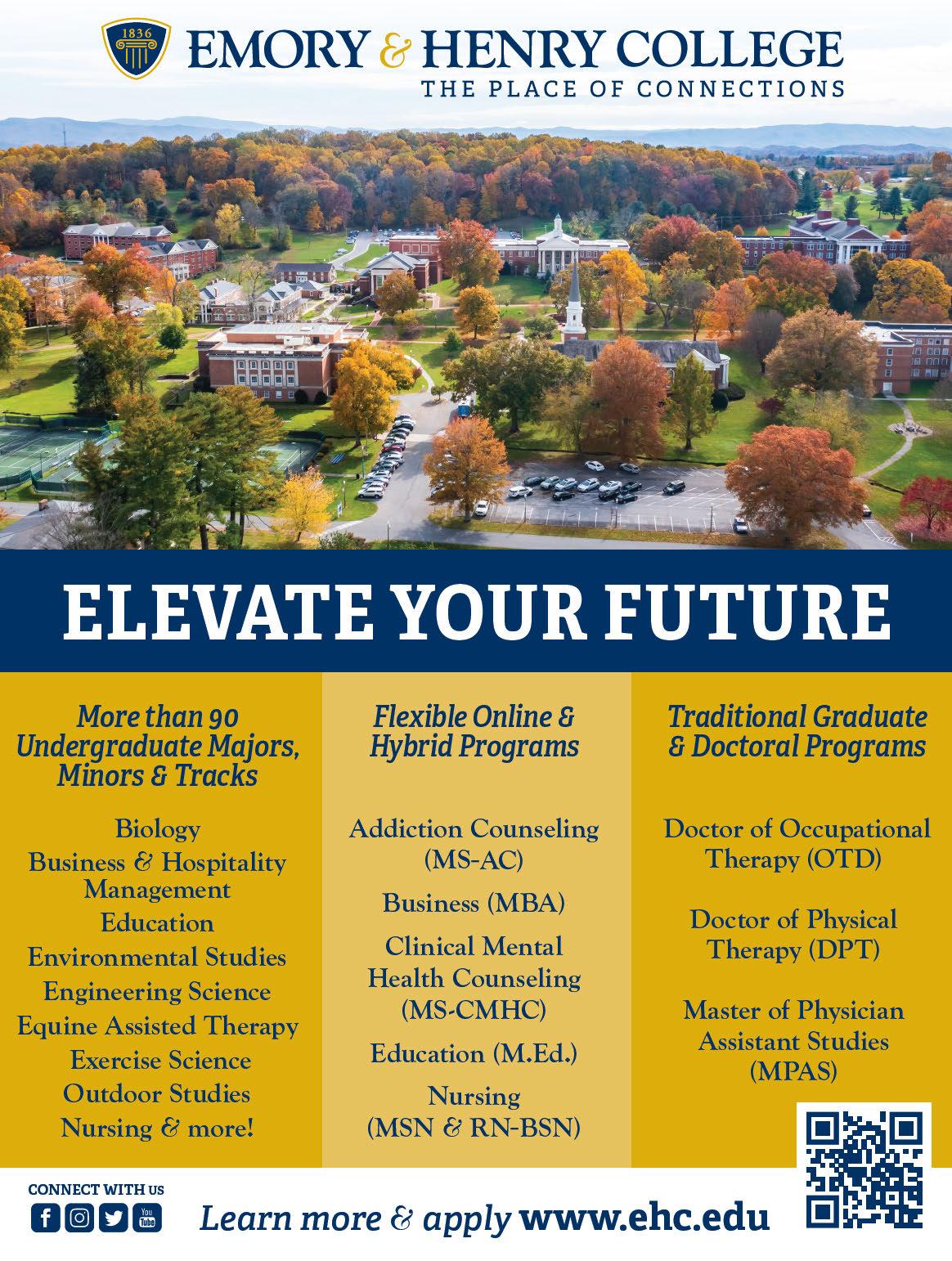

Families navigate the winding road to higher education

By Laura Anders Lee

As the mom of middle school boys, I love having friends in all phases of parenthood, whether I’m re-living the carefree kindergarten years or learning what lies ahead.

Several of my friends are in the throes of college applications this year. No ma er where they live or where their kids are applying, they share the same worries: “How much is this going to cost? Have we saved enough? Are their scores high enough? Can they actually get in?” ese questions are daunting for parents and overwhelming for students with their sights set high.

“ ere is just so much pressure on these kids, it’s crazy,” says Cristin Drummond, whose son, Jackson, is a senior at James River High School in Chesterfield County.

Drummond worries her son’s high performance in his school’s Leadership & International Relations program might not be enough to stand out, because Virginia’s schools have become increasingly competitive.

For the class of 2027, the University of Virginia received nearly 60,000 applications; it accepted just over 16%. In 1994, its acceptance rate was 34%. In the same period, Virginia Tech received about 45,000 applications and accepted 57%,

compared to 75% 30 years ago.

Virginia’s high application rates reflect a larger trend. e National Center for Education Statistics reports two-thirds of high school seniors go straight to college. Last year, roughly 19 million students were enrolled in U.S. colleges and g raduate programs, about twice the number enrolled 50 years ago, according to the Education Data Initiative. In addition, the online Common Application allows students to apply to multiple colleges with essentially one click. While convenient, the system has created an increase in overall college applications and wait-listed students.

To give kids the best chance at acceptance, some parents are hiring private advisers. A former college counselor at Trinity Episcopal School and Maggie L. Walker Governor’s School, Julie Bruner founded College Edge to guide high school seniors and their parents through the admissions process.

“Apply to reach schools, schools that are 50-50 and schools that are safe — and don’t apply to any schools you don’t like,” Bruner says.

She also recommends touring colleges as early as ninth grade. “When you’re traveling, fit in a visit. Or, we have a wealth of schools right here in Richmond, and it’s easy to set up a free tour,” she says. Bruner notes that being on campus with students present is a helpful way for prospective students to feel the vibe they’re searching for — small or large, urban or suburban, hot climate or cold, etc.

ey will also hear firsthand just how important grades are. “We can say it until we’re blue in the face, but they believe it from a stranger with an admissions badge,” Bruner says. “I tell my students to take the most challenging course load they can handle — that last part is important — manage that energy so you have a balance.”

Research now indicates high school GPA is a be er predictor of student success in college than standardized tests, according to the American Educational Research Association.

entered the world in the club room, between the pool table and the piano.

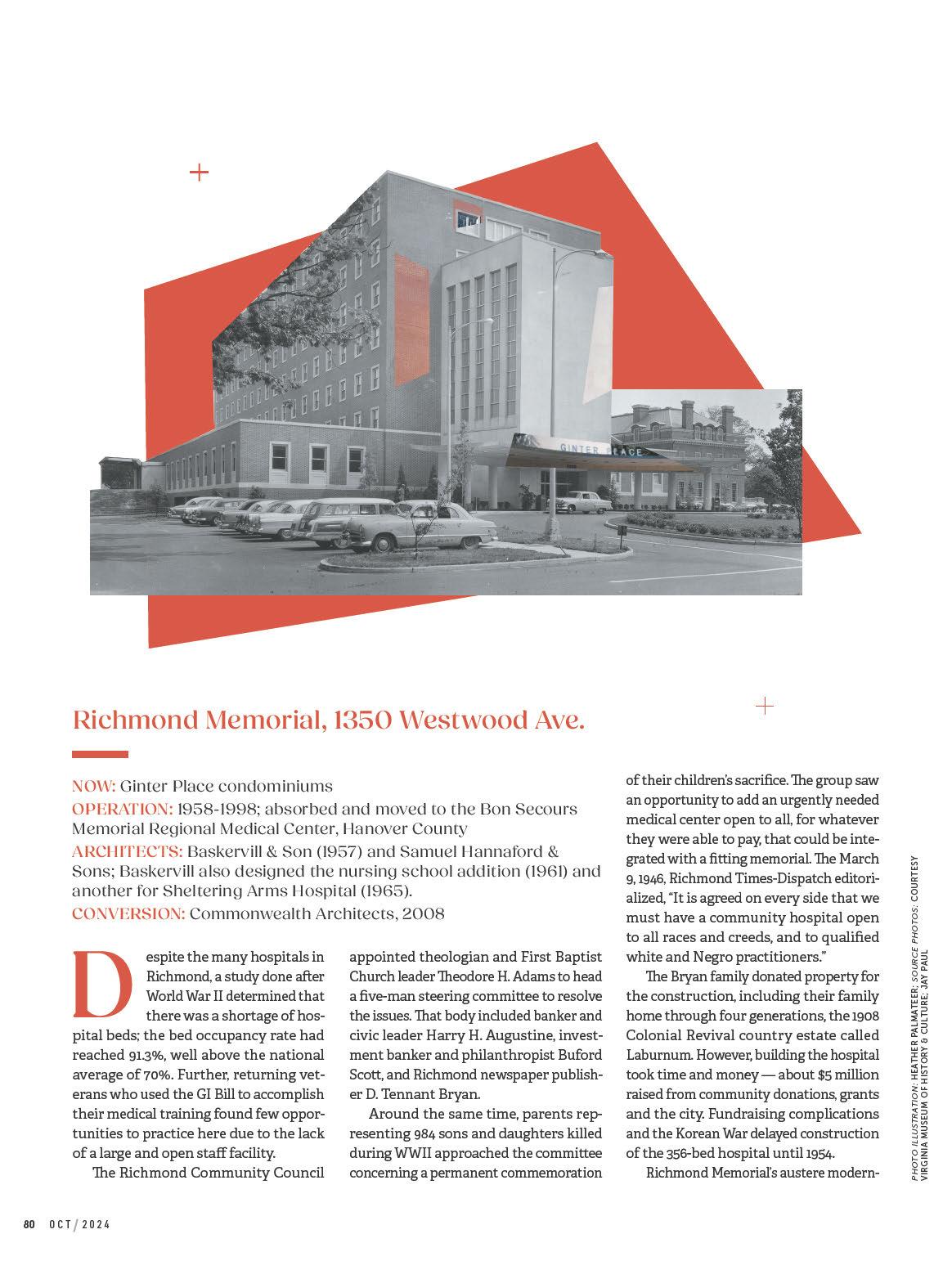

By HARRY KOLLATZ JR.

At least, that’s what blueprints seemed to reveal when shown to me by a resident of the Ginter Place condominiums during a pilgrimage I made to my birthplace — what was then the 7-year-old Richmond Memorial Hospital. Although no historical plaque yet touts the location as the site of my nativity, the conversion of the birthing room

into a hub for social activity seems entirely in keeping with my mature interests. is was but one spot in my exploration of five former city medical facilities transformed into living spaces.

‘A Church or Hospital on Every Corner’

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, several privately run medical centers operated in downtown Richmond — among them Grace Hospital — their

By Stephanie Ganz

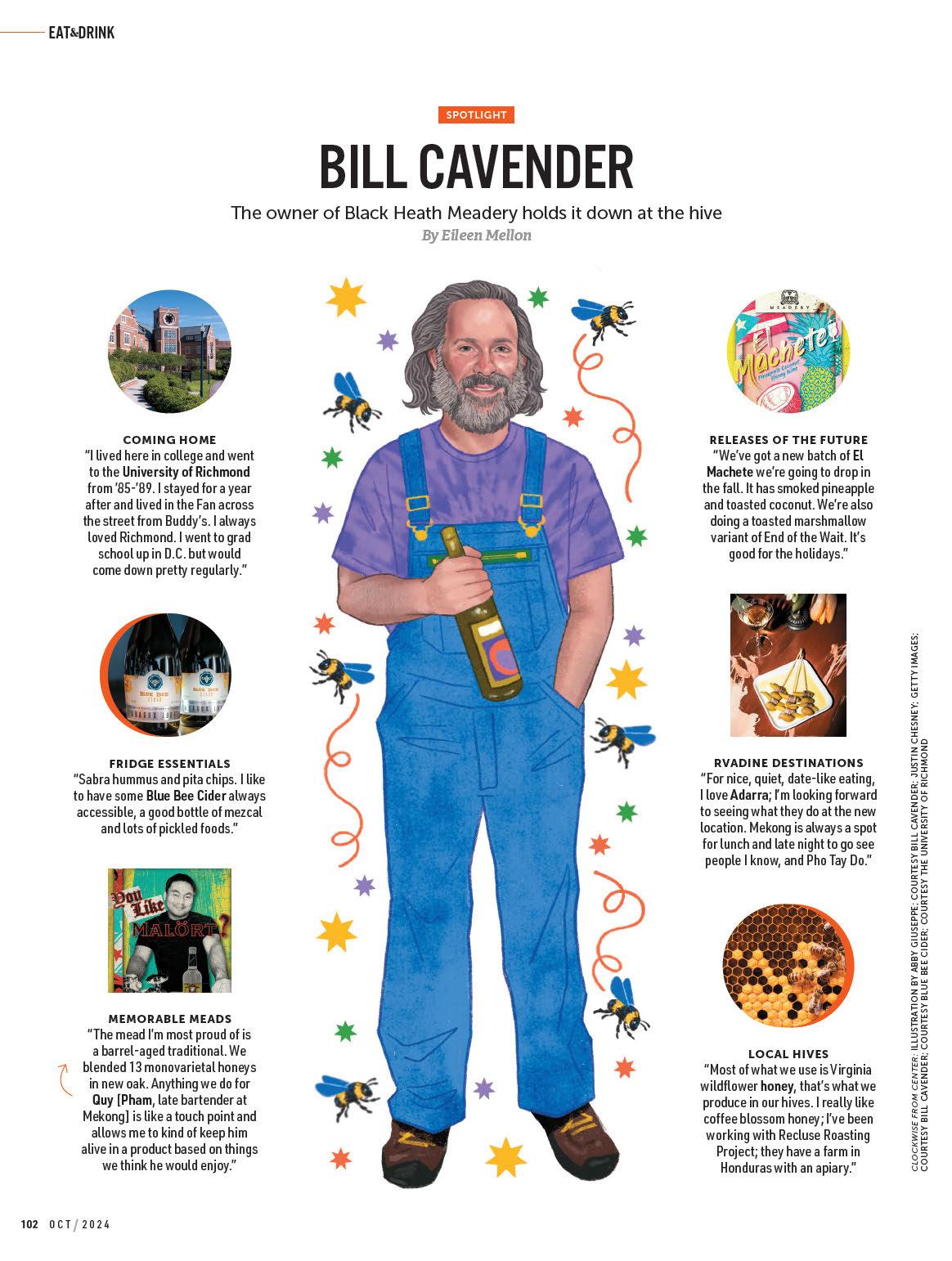

There’s flour in the air. Like a fine mist, it se les on every surface — the floor, the windowsill and on Evrim Dogu, who, a er 12 years as the co-owner of Sub Rosa Bakery, is used to it. Dogu is milling wheat, not in the shed behind his Church Hill bakery like he used to, but at Triple Crossing Beer in Fulton, where a 48-inch stone mill occupies a single room at the brewery.

Since Sub Rosa’s earliest days, baking with stone-milled flour has been central to the vision held by Evrim and his sister and co-owner, Evin Dogu. While the vast majority of professional bakers rely on commodity flour for their breads and pastries, Dogu sees a value in grains grown from farmers he knows by name.

Initially, Dogu planned to outsource grains to capture what he calls an “Old World aesthetic,” but, he explains, “I didn’t know it was possible for this simple thing to taste that good. When that’s the basis for a bakery — it’s the No. 1 ingredient you’re using

every day — that does shi your perception.” A er that revelation, Dogu became committed to baking bread from 100% stone-ground flour.

Along with Sub Rosa, a growing number of artisanal food and beverage businesses are sourcing regionally grown and heirloom grain varieties. Connecting with grain farmers, however, can be a fraught process with many obstacles. “ e burden is on each farmer,” Dogu says. “ ey have to be able to harvest, clean, store and then bag and ship the grain to us.”

Milling for eight hours a day, three days a week, Dogu typically produces 1,300 pounds of flour from about 1,600 to 1,700 pounds of grain. That flour is used in every loaf of Sub Rosa bread, sold wholesale to Pizza Bones and made into pizza and pastries, used to splendid e ect in an heirloom corn funnel cake at Metzger Bar & Butchery, and employed as the base for the delicate chew of Conejo’s flour tortillas.

These days, though, Dogu’s

e orts are more about supporting the farmers. “I can count the number of farmers we work with on one hand,” he says. “If we don’t have the farmers, then we’re just getting grain from elsewhere, and then what’s the point of being a Virginia bakery, doing Virginia cra , if we have no connection to the land around us?”

Enter the Common Grain Alliance. Established in 2018, the nonprofit has made a mission of connecting farmers and grain users in the mid-Atlantic grain economy. Originally just 13 people (including Dogu), the network now comprises 128 members spanning farmers, millers, bakers and, increasingly, brewers, maltsters and distillers, for whom wheat and other grains are just as fundamental.

“We’re trying to figure out, how do you communicate to a consumer the environmental, social and personal health benefits of shopping local grain?” says CGA Executive Director Madelyn Smith. While small grains can be more expensive and require a bit of knowledge to work with compared to the bags of all-purpose flour at the grocery store, they’re more nutrient dense, free of preservatives and an important component of a localized economy.

Grapewood Farm, located in Virginia’s Northern Neck in Montross, has been supplying small grains to professional and home bakers since 2000. Owned and operated by Fred, Cathy and David Sachs, Grapewood sells its grains online to customers including Sub Rosa and Richmond pasta purveyor Oro. ey also express a need for more infrastructural support.

“The practical solutions that are in front of us require that we form cooper-