Inside the struggle to return training thoroughbred horses to a stable industry

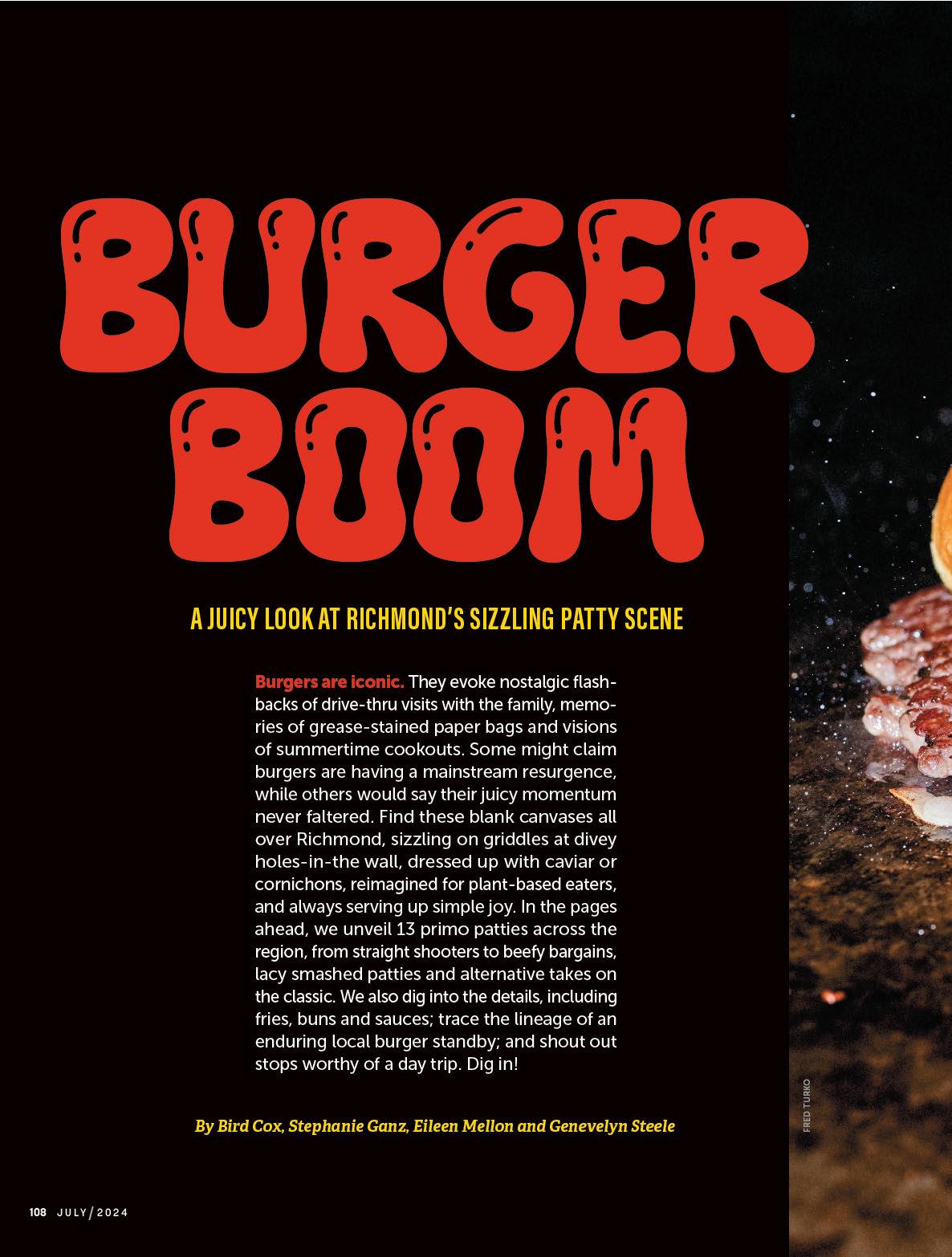

A juicy look at Richmond’s sizzling patty scene

By Bird Cox, Stephanie Ganz, Eileen Mellon and Genevelyn Steele

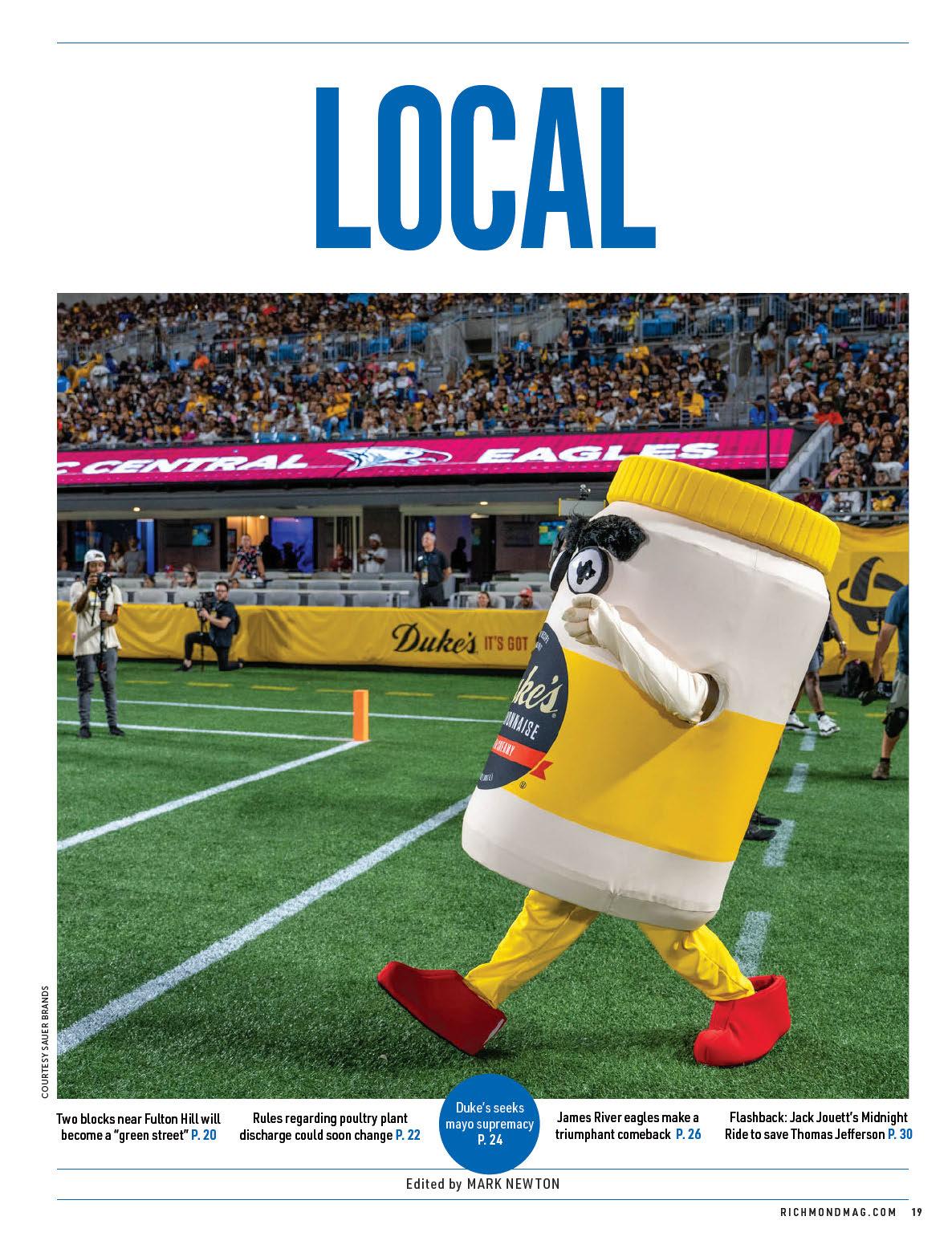

Devotion to Duke’s began in 1917 a er America entered the first World War. An enterprising local woman named Eugenia Duke began selling sandwiches at Army canteens and other eateries around Greenville, South Carolina, to contribute to her family’s income. A er the war, she began bottling her nowfamous spread for sale.

Then, as today, the recipe used egg yolks, oil and cider vinegar, the la er of which gives Duke’s its signature twang. Unlike others — including Hellmann’s — Duke’s doesn’t add sugar, which was rationed during wartime and le out of the recipe.

Struggling to keep up with the demand for her namesake mayonnaise, Duke sold the business to Sauer in 1929. For decades, Sauer expanded its footprint throughout the Southeast. In 2019, private equity fund Falfurrias Capital Partners acquired Sauer and the Duke’s brand.

Since then, a new creative team has responsible for spreading the love.

RICHMOND DNA

It was the kind of viral moment that a social marketing manager dreams of.

While dancing to celebrate winning the first Duke’s Mayo Bowl in December 2020, the University of Wisconsin Badgers quarterback Graham Mertz dropped the trophy, shattering the football-shaped piece of Lenox crystal on top. Mertz had

a solution: He taped a squeeze bo le of Duke’s to the base and posted an image to his Instagram.

As ubiquitous as Duke’s may be in the South, the brand was still relatively unknown to much of the country. With the sha ering of a crystal football, that began to change.

Like many consumer packaged goods, Duke’s saw a surge in sales in early 2020 when the pandemic led people to stock their pantries. That June, Falfurrias hired Rebecca Lupesco as “Duke’s brand manager of ‘mayohem’” and digital content manager Sarah DiPeppe to further the brand’s good fortune.

“The dream for a marketer is when there’s this passion that already exists,” Lupesco says. “We’re not creating this; we’re really just fueling the fire.”

Before Lupesco came on board, the brand’s tagline was “The Secret to Great Food.” In 2020, Sauer’s then-creative agency, The Richards Group in Texas, came up with “It’s Got Twang.” Lupesco says the previous slogan “was not differentiating to the brand, whereas ‘twang’ was really taking the tanginess of the mayo, combined with our Southern roots and our heritage and personality, and bringing it to life.”

Following controversy around The Richards Group, Sauer moved its creative business to Richmond ad agency Familiar Creatures, which focuses on challenger

brands, those that have outsized ambitions in industries in which they’re not the market leader. While Duke’s is the third best-selling mayonnaise brand in America, Hellmann’s and Best Foods, both owned by Unilever, take up 98% of the market share.

“Challenger brands usually have to show up in new and innovative ways to attack the market leaders, and that’s what we’ve been doing with Duke’s since Day One,” says Dustin Artz, who co-founded Familiar Creatures with Justin Bajan in 2018. The two met while working at the Martin Agency.

Artz credits Lupesco and DiPeppe with much of the brand’s recent success.

“They’re taking a brand that is thought of as cool and nostalgic and not ruining it with a corporate sensibility,” Artz says. “That Duke’s fans are unapologetically fanatics over a mayonnaise is kind of absurd, and we lean into that.”

Where the brand previously marketed itself to older Southern women, it’s now going a er younger consumers who are already intensely loyal.

“The shi has been to millennials — Southern-minded millennials, we call them. Tastemakers who are up on new things, good food, ta oos, chef culture, etc.,” Artz says. “We are leaning into that. It’s not like we’re Be y Crocker and now we’re trying to be young and hip. It has fundamental DNA in the brand.”

Another big part of the brand’s DNA is Richmond itself. Not only are Sauer and Familiar Creatures based here, but so is Golden Word, Duke’s PR firm. Lupesco, who met Artz and Bajan at the Martin Agency, says the talent pool and culture of Richmond have created an ideal scenario for Duke’s recent marketing push.

“There’s a deeper partnership that can happen when we all share the same city and know the same folks,” Lupesco says. “It’s just a testament to the creative talent that Richmond has.” R

Richmond.” Arnold set fire to the vessels of the Virginia navy. Phillips continued into Manchester, where he burned tobacco stores and public buildings, stole furniture and slaughtered ca le and hogs.

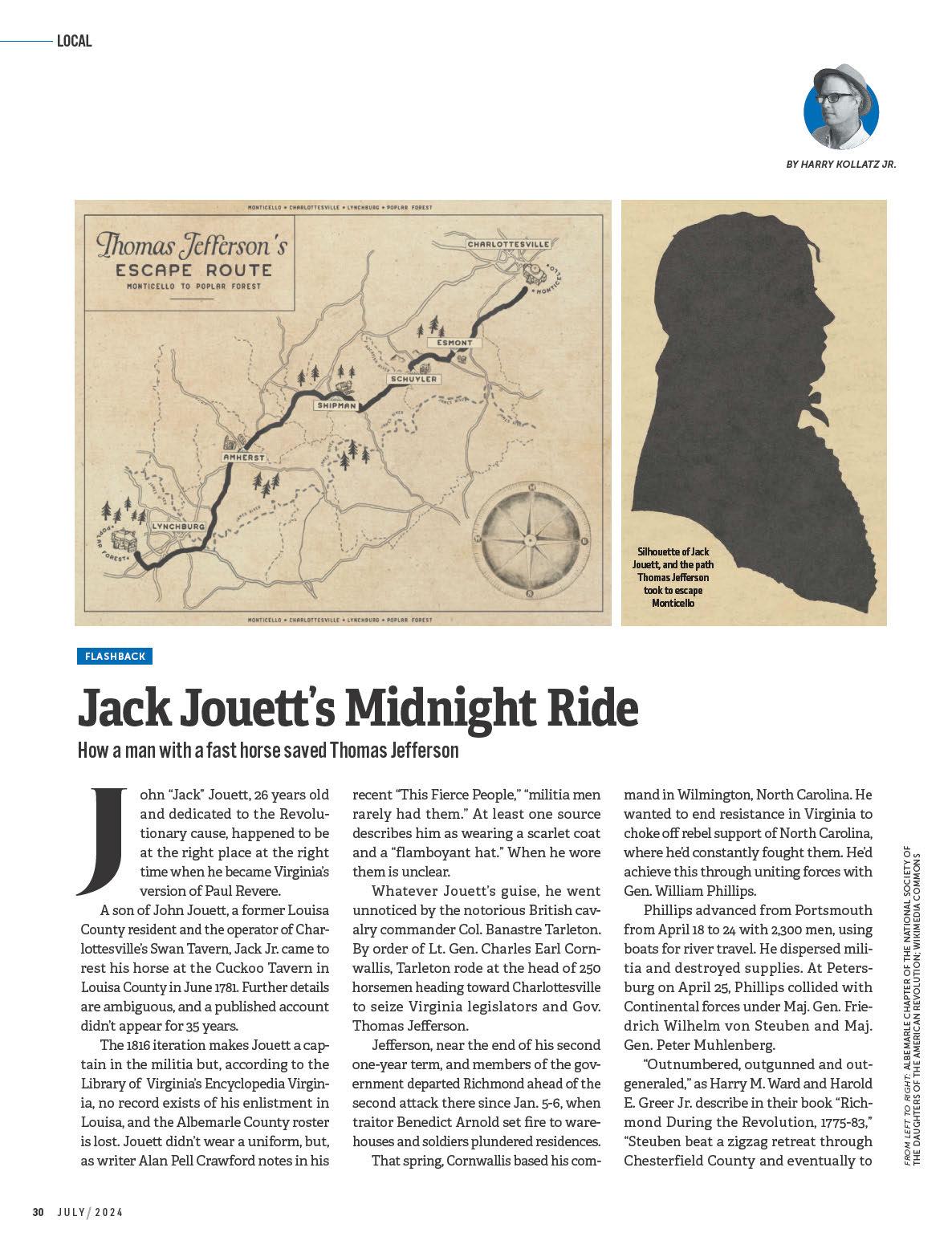

On May 10, the Virginia government evacuated the state capital and headed for Charlo esville.

Jefferson sent his family first to a friend’s plantation, then to his Poplar Forest farm near Lynchburg, and then to Monticello.

Eliza Ambler, whose father, Jacquelin, served on Virginia’s Council of State, a ested to correspondent Mildred Smith the situation in Richmond: “Such terror and confusion you have no idea of. Governor, Council, everybody scampering. ... How dreadful the idea of an enemy passing through such a country as ours commi ing enormities that fill the mind with horror and returning exultantly without meeting one impediment to discourage them.”

Ambler further jibed: “But this is not more laughable than the accounts we have of our illustrious [Gov. Jefferson] who, they say, took neither rest nor food for man or horse till he reached [Carter’s] mountain.”

A courageous and ba le-tested ally,

the 23-year-old Maj. Gen. Marquis de Lafaye e, formed on the north side of the James River with about 3,000 men, though only some 900 were experienced Continental troops.

Lafaye e couldn’t take the British in an open fight until additional men arrived from Pennsylvania from “Mad Anthony” Wayne. Delayed by commissary problems, his men wouldn’t get there until June 10. Meanwhile, Lafayette harassed the invader.

Phillips believed Richmond was an easy conquest until he viewed Lafaye e’s force bristling on the ridges of the north bank. Before Phillips called a halt, several British boats a empted a landing, but a swift militia charge drove them back across the James River.

An angry Phillips withdrew to Petersburg to await Cornwallis. Lafaye e shied his command to Wilton plantation in eastern Henrico County. At the Bollingbrook house in Petersburg, Phillips died of yellow fever on May 13.

Cornwallis arrived in Petersburg on May 20. He took command, sent Arnold to New York and anticipated the arrival of 2,000 reinforcements, making his force of 7,000 the third-largest army fielded by the British during the entire war.

Crawford emphasizes Joue ’s advantages: alone, fresh and knowing his way, even in the dark. Yet branches slapped and bloodied his face, and he bore scars the rest of his life.

At 4:30 a.m., he arrived at Monticello, shouting, “You must flee!” A convivial Jefferson saluted him with a drink of Madeira. Then Joue and steed galloped down the mountain to roust slumbering legislators who included Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. They’d make their way to Staunton.

Daniel Boone, however, then a representative from what became Kentucky counties, got swept up by British dragoons and spent some time stowed in a coal house.

Jefferson, though, made preparations to send his family and guests to safety. For two hours he and his servant Caesar prepared important papers and valuables for the run. They started out, but then Jefferson realized he’d left his “walking sword.” Using a telescope, they saw greencoated British dragoons in Charlo esville’s streets, and it was time to scurry.

In a message to Clinton, Cornwallis outlined how he planned to dislodge Lafaye e by destroying “any magazines or stores in the neighbourhood.”

He dispatched Col. John Simcoe and his Queen’s Rangers to seize a stockpile center near present-day Columbia and Sco sville, and he sent Tarleton from Hanover Courthouse to Charlo esville with instructions to destroy rebel capacities until joining the main force at Jefferson’s Goochland County plantation, Elkhill.

An d at Cuckoo Tavern, the attentive Jack Jouett somehow learned of Tarleton’s plans. He set off on the night of June 3-4 to ride 40 miles through forest and field, carrying the warning to Jefferson and the legislators that the British were coming.

Within minutes, a British detachment under Capt. Kenneth McLeod arrived at Monticello. He found the place in the care of Jefferson’s butler, Martin Hemings. To McLeod’s credit, he le the house and grounds undisturbed.

Cornwallis, though, laid waste to Elkhill, burning the barns and taking away 30 enslaved people, the livestock and horses, except for the colts too young to ride, whose throats he ordered cut. Many of the enslaved fell fatally ill.

A quorum of the legislature in Staunton voted Thomas Nelson Jr., head of the Virginia militia, as governor. They also voted their appreciation for Joue and the gi to him of “an elegant sword and pair of pistols.”

Joue moved to Kentucky, ultimately serving both in the Virginia and Kentucky legislatures, fathering a large family and dying in 1822.

While documents indicate repeated efforts to put a ceremonial sword in Joue ’s hands, there’s no evidence that he ever received one. R

By Kevin Johnson

new kind of dental cosmetic flair, spurred by escalating beauty trends and new pressures for self-expression, is on the rise. Just ask A.J. Sunkins, and he’ll tell you with a shimmering, silvery smile.

“I’ve been wanting this for a couple years now,” Sunkins, 22, says. “I was like, ‘Listen, I want them to bling. When I smile, I want them to brighten up.’”

The Richmonder got his tooth gems done in May at Atelier, one of a handful of local cosmetic salons that offer the service of bonding crystals and precious metals to tooth enamel, for roughly $1,000. A er seeing wide receiver Odell Beckham Jr.’s jewelry-filled jaw (valued at $1.8 million), Sunkins was hooked. “I saw this guy’s full set of tooth gems and liked what he had, but I put my own spin on it.”

Growing out of the era of grillz (diamond-and-metal jewelry meant to cover entire rows of teeth), the modification has hit the mainstream as a low-impact and creative way to personalize a smile. The straightforward nature of the gems, which are bonded to teeth similarly to brackets used for braces, appeal to many looking for nonpermanent jewelry to express themselves in new ways — especially Gen Z.

Tooth gems are a part of a broader landscape of modern cosmetic enhancement trends over the years, seen in the shiny mouths of Hollywood stars and rappers and all over social

media platforms, where people show off and market their latest designs.

Savannah Sheely co-founded Atelier in 2017, offering cosmetic ta ooing, microblading, lash extensions and more. That’s also when she introduced the tooth gems service to the practice, while the trend was nascent in the area. She has since seen a steady increase in demand.

“It fits into a lot of what we do here. It makes you feel so beautiful with low maintenance,” Sheely says. “It’s like permanent makeup; you can wake up and it’s just there.”

Midge O’Brien was among Sheely’s first patients, ge ing new gems and styles swapped out weekly. “I was obsessed; they’re addictive,” O’Brien says. “I was so gung-ho for something less permanent than ta ooing and piercing, and these are just so fun.” In 2022, as the studio expanded to its new location on Cary Street, O’Brien went from patient to provider and joined the studio as a tooth gem specialist.

O’Brien explains the a raction many patients have with tooth gems while sporting a row of Swarovski crystals on her upper and lower teeth. “It’s a very quick process and totally reversible, which I think is the huge appeal for a lot of people,” she says. “It’s the newest option there is for a fun new accessory.”

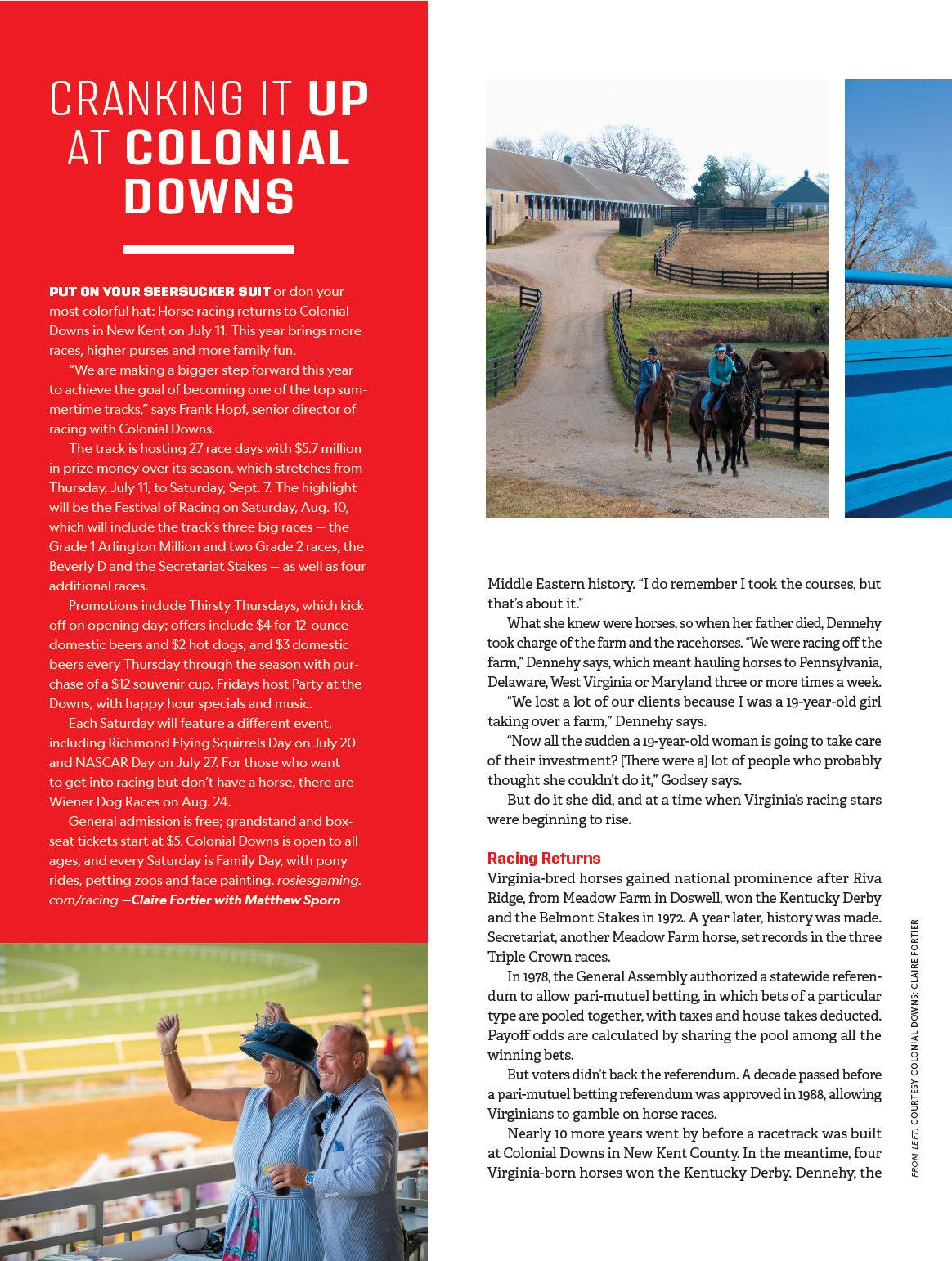

has been a story in survival. “When they say blood, sweat and tears, I mean, it was buckets of them all,” Godsey says. “ e farm was up and down, and the [racing] industry was up and down.”

Critical to Eagle Point Farm’s survival was a notable change in Virginia’s horse racing policy and a “really good horse. It all started with Toccoa in 2005,” Godsey says.

Toccoa was her first winner as a trainer. “She won at Colonial Downs, and she won 10 races, making over $100,000. She had four foals, all of them winners. ree made over $100,000. Her second foal, What the Beep, was my first stake winner.”

What makes Toccoa’s success even more inspiring is that there was nothing about her that racehorse owners would have found impressive. Owners are o en willing to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for high-end breeding to get the horse they

fervently believe will win big races, including using computer-generated scores to predict a pedigree mix, but Toccoa wasn’t that kind of horse. “She had what we call ‘backyard pedigree,’” Godsey explains. “She was locally bred, but she had a ton of heart.”

Being fast is essential for any racehorse, but having the heart to race is critical for success. “You can spend a million dollars at a sale, and you might not have a racehorse. You can’t buy it. I have had many [horses] that have pedigree out the wazoo and seem so talented, but if they don’t want to do it, they are not going to. I’ve had some horses that are the most backwoods-bred things in the world, but they can also be the most determined,” Godsey says, adding with a chuckle, “ at’s kind of what keeps everybody in it.”

“You certainly appreciate the peaks because there can be

many valleys,” says Christine Applegate, a retired airline pilot from the Eastern Shore who has had horses trained at Eagle Point Farm. “It’s an absolute labor of love. We brought our yearling to Karen, who trained her until her first race at Colonial Downs. She [placed] second in her first race. Since then, she has won numerous races.”

Horses usually come to Godsey in the spring when they are a year and a half old. In September or October, she starts some initial training “to get a li le foun-

“ When they say BLOOD, SWEAT and TEARS, I mean, it was BUCKETS of them all.”

KAREN GODSEY

dation on them. I don’t push these horses, but I know it is very important to start with them early. It’s like a kid starting with T-ball before he goes to the major leagues.”

When the foals are old enough, Godsey breaks them, teaching them to take a bridle and a bit, then a saddle and finally a rider on their backs.

“Each horse is di erent, and you need to figure out what makes them comfortable and happy because a horse will perform be er when they are happy. ey all have their own personalities. What works on one horse may not work on another. You just have to be flexible. They will humble you,” Godsey says.

But that’s just the beginning. The young racers must learn to be loaded

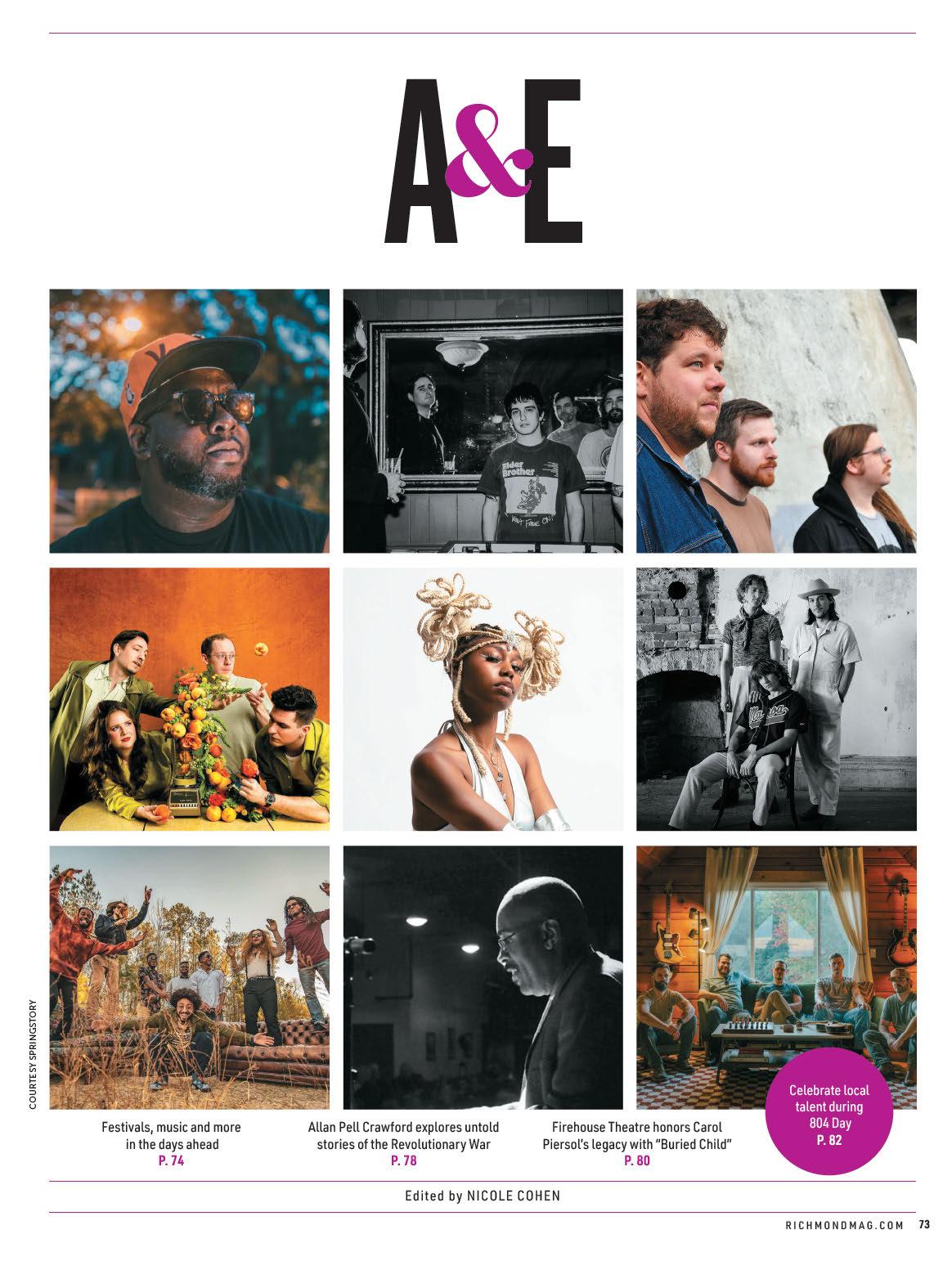

into a cramped starting gate, then leap out of the gate the second it opens and run in a jostling, chaotic pack as fast as they can with the singular focus of being first.

Godsey, who has trained many winners since ge ing her trainer’s license in 2005, has ridden the modern-day roller coaster of Virginia thoroughbred racing, from the opening of the state’s only racetrack in 1997 to its closing in 2013 — which almost led to the demise of the thoroughbred horse business in Virginia. But she was there for Colonial Downs’ reopening in 2019, and “it’s been o to the races” ever since, she says.

It’s a calling Godsey was born to, just like her mother, and her grandfather

T. Edward Gilman before her. In fact, Godsey and Dennehy are carrying on a family tradition that started in 1947 with a crazy bet.

As the story goes, Gilman, a local real estate agent, was so taken with an ad he wrote about an old farm that his family had owned, he bought the property himself. But he wasn’t much of a farmer. “My father hated chickens and dairy ca le, but he liked horses,” Dennehy says.

What Gilman loved was a retired racehorse named Ginger. He used her for foxhunting, o en bragging about her speed, although she had never won a race. One night, a er a few drinks with Dick Keeley, a neighbor who owned a racehorse, Gilman made a wager: his Ginger against Keeley’s racehorse. Keeley accepted, and a match race was set up at a county fair, with the event garnering much a ention in the local newspaper. “ e race was the most talked of event of the Meet,” according to a 1952 story in the Ashland Herald-Progress.

Outfi ed in foxhunting gear, Gilman faced o against Keeley, who was decked out in racing silks. Ginger won, and Gilman was stricken with racing fever.

Gilman was so convinced his horse was a winner that he loaded her in a trailer and set out to the Charles Town Race Track in West Virginia. When he arrived, he stopped at a local drugstore and asked if anyone knew a trainer. One happened

to be si ing right there, enjoying lunch at the counter. No amount of dissuasion on the trainer’s part would deter Gilman, so the trainer took on Ginger for the last race of the season. She won, shocking the racing community and inspiring Gilman to breed racehorses.

With each race Ginger or her o spring won, Gilman added on to Eagle Point Farm and his growing stable of racehorses.

e task of keeping Eagle Point Farm operational over the next 70 years is, at its core, the story of horse racing in Virginia.

Back in Colonial days, George Washington and Thomas Je erson had plenty of chances to show o their best horses. According to research compiled by Charlie Grymes on Virginia places.org, racing — and gambling on races — was a popular Virginia pastime starting in the early 17th century, well before the colony’s first track, a 1-mile oval, was built in Williamsburg. Nearly a dozen more tracks operated around Virginia in the 1700s, including five near Richmond. But in 1894, racing corruption and Victorian sensibilities led the General Assembly to ban gambling on horse races. Some exceptions were made for state fairs and agricultural associations, such as the Camptown Races in Ashland, which closed in 1977, and the Strawberry Hill Races

former president of the Virginia oroughbred Association and director of the Virginia Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association, was also co-chair of the architectural review committee that helped design Colonial Downs, which opened in 1997.

Getting from the barn to the track is the easy part of training young horses. Getting them into a starting gate requires more coaxing.

More than 13,000 people were there for the track’s opening day. And for a while, horse racing was back in Virginia.

Then a dispute between Colonial Downs management and local horsemen’s groups closed the track in 2013. “A lot of farms went out of business because the track shut down,” Dennehy says.

Godsey, who had now taken over the farm, was an accomplished equestrian — she was the overall individual champion at the 2004 A liated National Riding Commission and placed third in the 2005 Intercollegiate Horse Show Association National Championships — and trained a successful stakes horse within a year of graduating with honors from Sweet Briar College and ge ing her license in 2005. But experience and expertise weren’t paying the bills.

“We didn’t have good horses and didn’t have many good clients,” she explains.

“Ge ing paid was a huge issue.” A er she took over the farm, Godsey says, “the first thing I did was to get rid of all the stallions. ey were pu ing us in a hole. I decided that I was going to focus on training.”

It turned out to be the best decision she could have made.

“Donna hung in there during the lean times,” says Rob Bailes, a trainer for Maryland’s Laurel Race Track who has known the family at Eagle Point Farm since he was a boy and his father trained for Meadow Farm, home of Secretariat. “What Karen [has] done with Eagle Point has been spectacular. They do such a good job. It takes a great deal of work and dedication. It has to be something you really love.”

All tracks and horsemen’s associations get income from online and o -site be ing, which can be used for prize money. Without a track, that money sat in the bank until 2017, when the Virginia oroughbred Association created the VirginiaCertified oroughbred Program, which gives bonuses for winning horses trained in Virginia (see story on Page 105).

“ e program was wonderful,” Dennehy says. “Before the program, we were hustling. You would take anybody you could get. But since, we have been able to raise our rates. All our employees have go en raises. For us, we got a full barn. We are turning away people.

“You are going to send your horse somewhere to be trained, why not send them someplace you get an extra 25% bonus anywhere they race in the mid-Atlantic? It helped save a lot of people’s businesses. It certainly saved mine. Now Virginia is one of those spots that everybody wants to bring their horses.”

Supportive legislation passed by the General Assembly and substantial investment by new owners enabled Colonial Downs to reopen in 2019. There will be 27 days of racing this summer, but next year “that could be 45 to 50,” says Debbie Easter, executive director of the Virginia oroughbred Association. e economic impact of horse racing for the industry and the state has been significant, totaling $542.1 million and creating 5,297 jobs. With the recent purchase of the track by Churchill Downs and the success of the Virginia-Certified oroughbred Program, the future of horse racing — like that of Eagle Point Farm — seems to be back on track. R

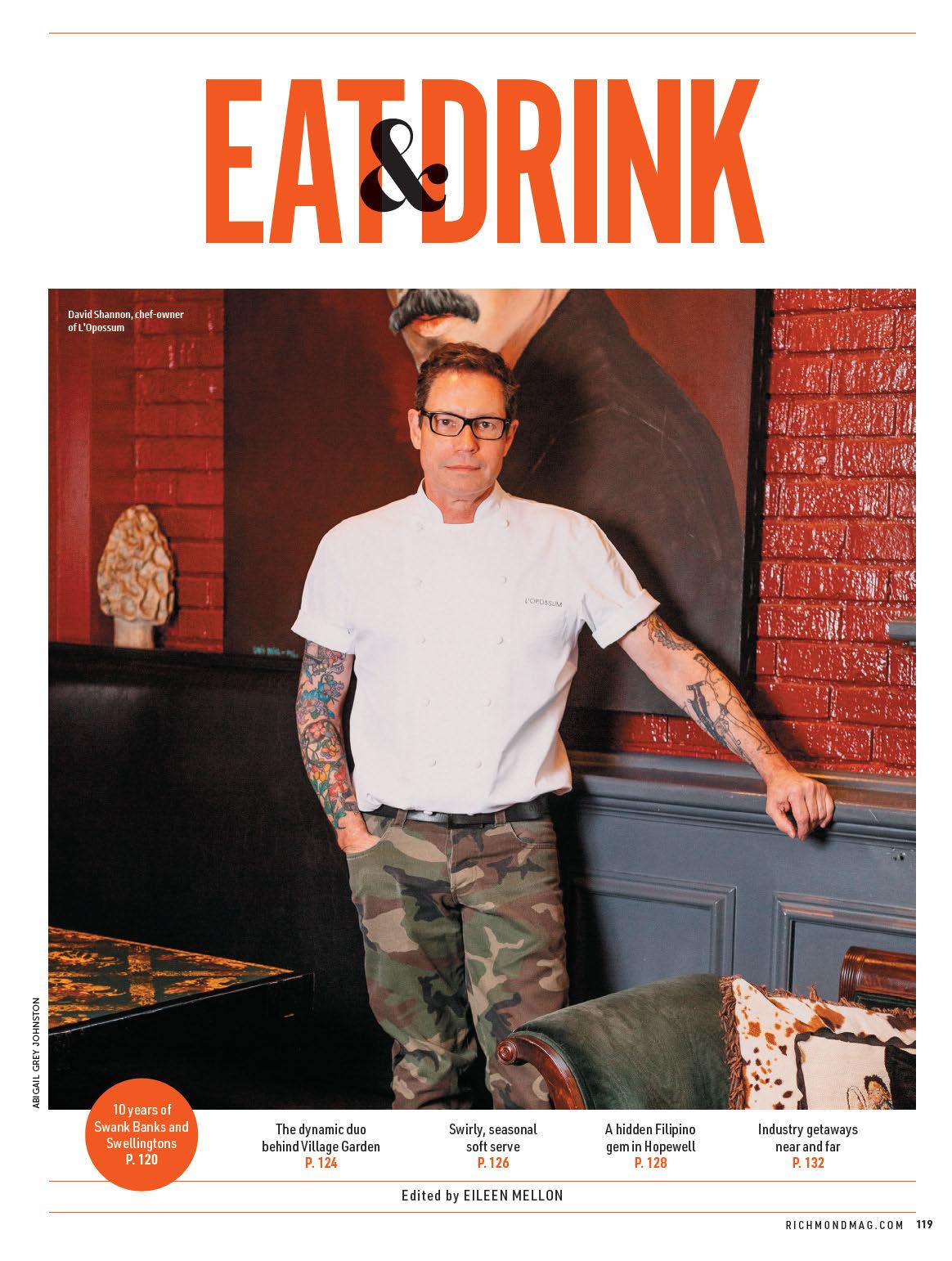

ing it light and playful is very deliberate,” he notes. “You get heavy and bogged down with serious food. I didn’t want to be a serious restaurant.”

at sentiment has proven true during some of L’Opossum’s legendary ticketed dinners, such as the time Shannon booked Puddles, a 7-foot singing sad clown, as a surprise during an honorary dinner for his mentor, Inn at Little Washington chef Patrick O’Connell, or the raucous foodporn-themed dinner in 2018 with adult film star Jack Vidra and author Madison Moore.

While those nights were a masterclass in “surprise and delight,” general manager Will Seidensticker, who’s been with L’Opossum since 2016, notes that people celebrate major milestones at the restaurant year-

round. “It’s very common to wait on somebody’s 50th anniversary. We’ve even had 70th anniversaries,” Seidensticker says. “Hearing those people’s stories, and what they’re taking from it — because everybody takes something different from it — is really rewarding.”

Many of those guests have become faithful regulars over the years, including Herb and Betsy Hill. “From the unique ambiance of eclectic art and music to the creative and themed descriptions of cocktails and menu choices, it truly is one of a kind,” Herb says.

“Every single detail in this place is one man,” Worsham says with reverence, “and this is his collection of things. You’re in a man’s vision. I feel really lucky, just as

someone who’s also an artist, to be working here to be serving this amazing food.”

For Shannon, L’Opossum couldn’t exist any other way. Each careful choice over the last decade has built on his original vision to make the restaurant the standout it is today. “A lot of these things were on a long list that people said you can never do in a restaurant: You can’t put this art on the walls, you can’t play this music, you can’t write like this,” he says. “And I just kept thinking, ‘You know what, I’m going to play.’ It just all entertains me. It’s fun to do. I think that’s why it works.”

His words call to mind another quote from “Wild at Heart,” in which Sheryl Lee as the Good Witch tells Nicolas Cage as Sailor, “If you are truly wild at heart, you’ll fight for your dreams.” R

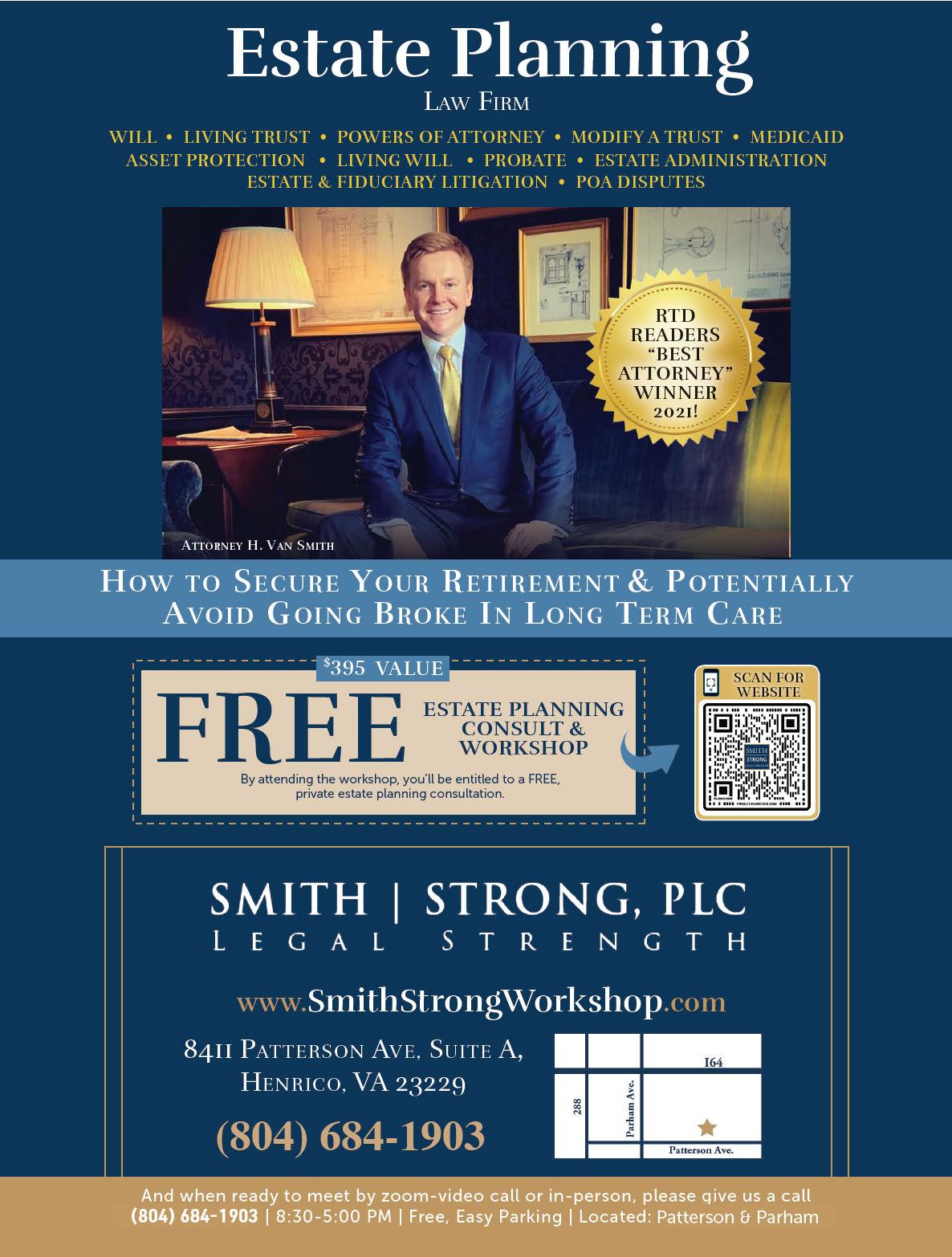

7/4 “The Big Show” 5:30pm

7/6 The English Channel 8:00pm

7/7 14th Annual Gospel Music Fest with The Belle 5:00pm

7/12 Silent Movie 9:00pm

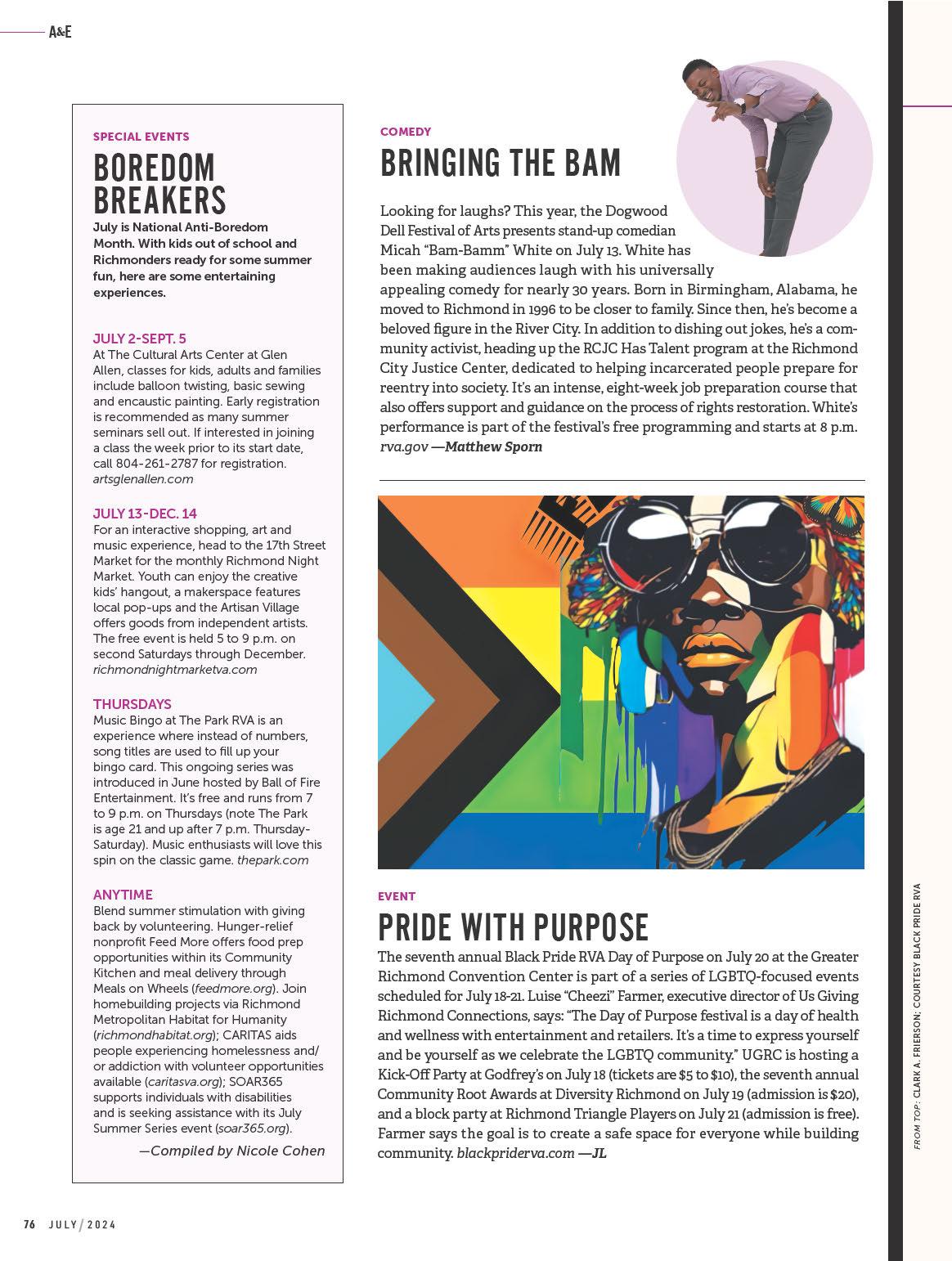

7/13 Sounds Funny with Micah “Bamm” White 8:00pm

8/3 Pitchin’ A Fit & South Hill Banks 7:00pm

8/16-17 SPARC Presents: You’re A Good Man Charlie Brown 7:00pm

8/23-25 Firebringer 8:00pm

8/31 Afro Festival 12:00pm

9/1 Andrew Ali 8:00pm

9/7 An Evening with Prince - A Tribute 8:00pm

9/20 Sounds Funny with Micah “Bamm” White 8:00pm

9/21 Silent Movie/Silent Party 9:00pm