The deaths of two VCU students in a single semester has left Richmonders wondering what is being done about pedestrian safety in the city

By Emily McCrary-Ruiz-EsparzaThe makeup of the next Virginia General Assembly will be historic, no matter what happens in November

By Don Harrison

By Don Harrison

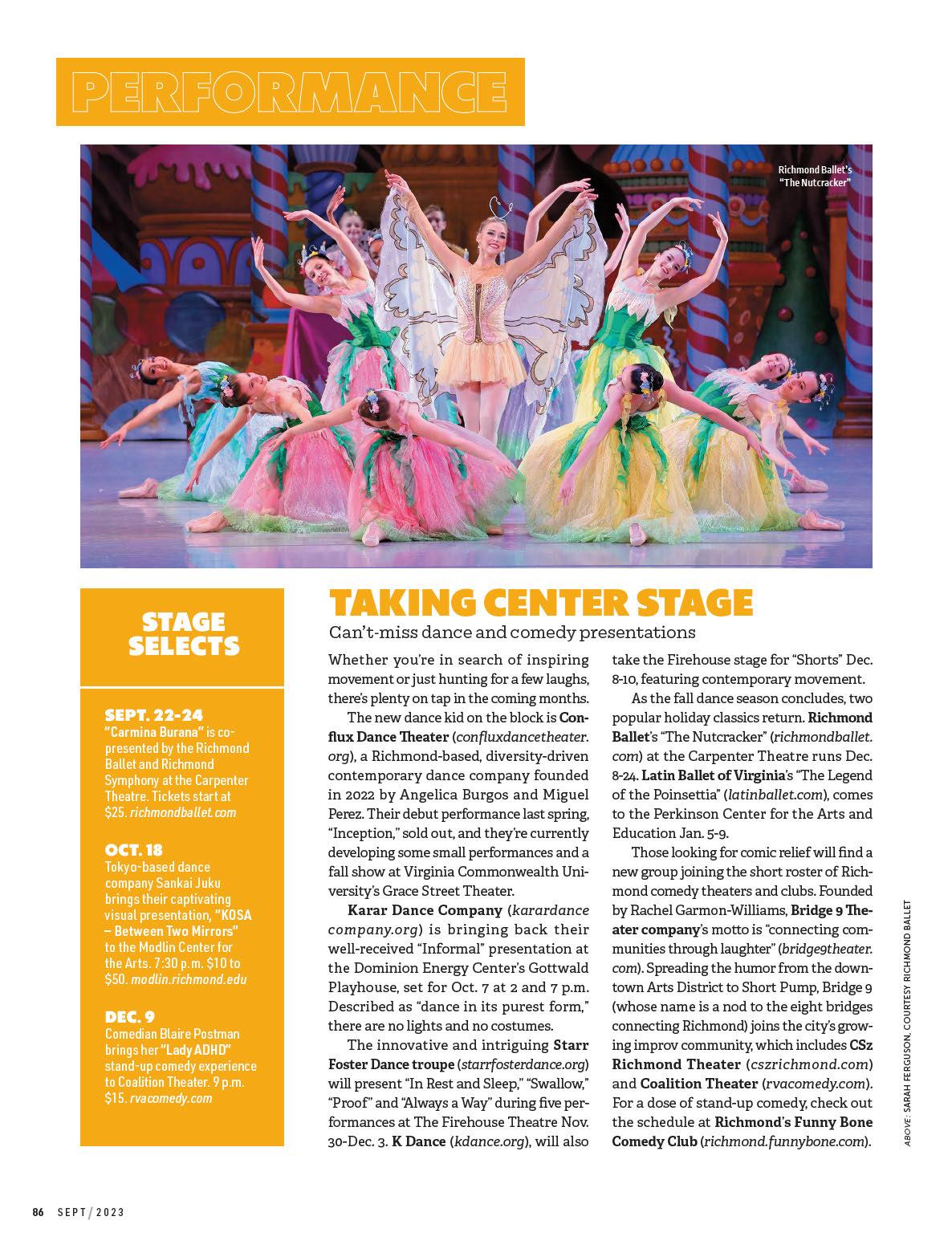

From enriching exhibitions to pulsepounding performances, the months ahead promise arts experiences that will please even the most discerning connoisseurs

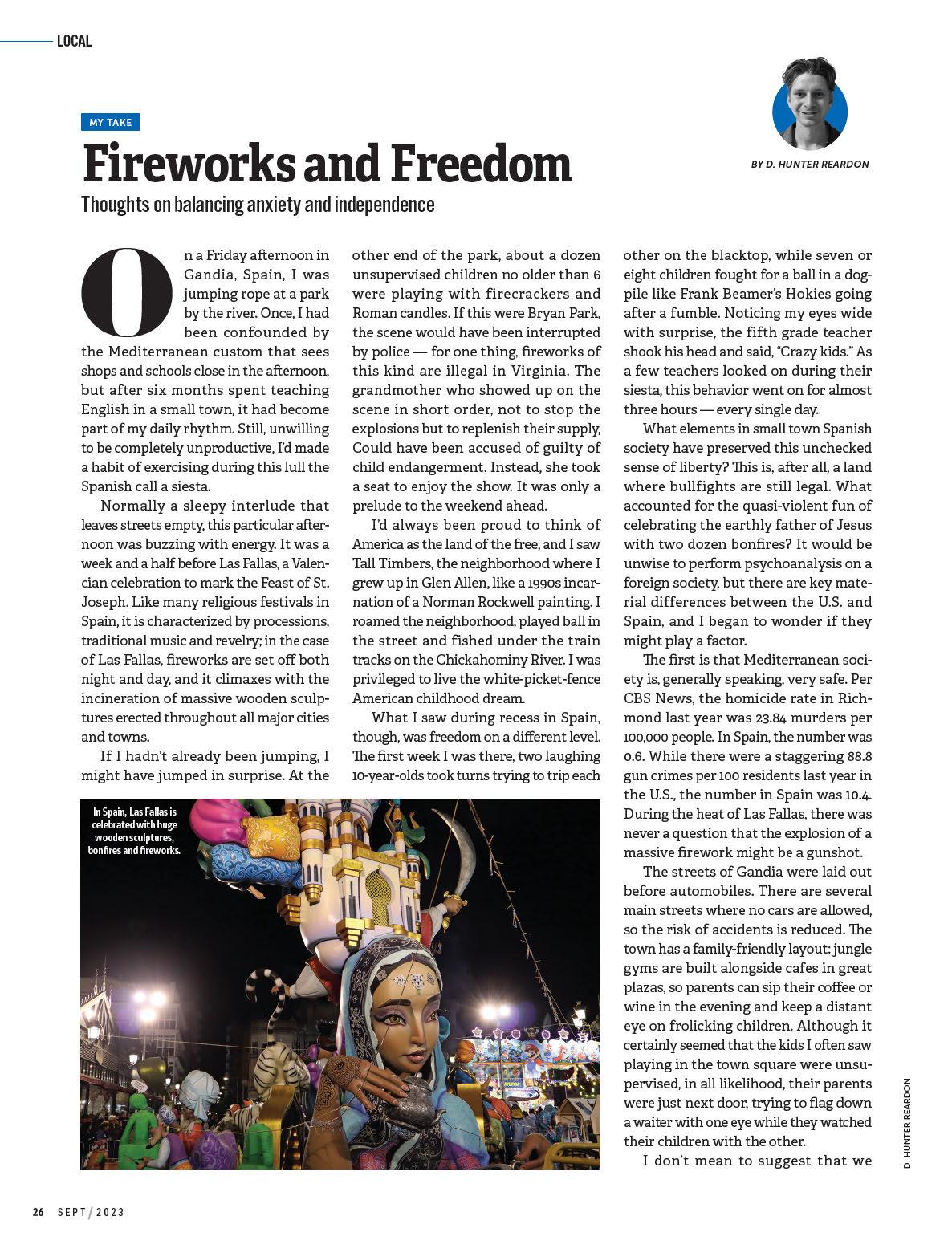

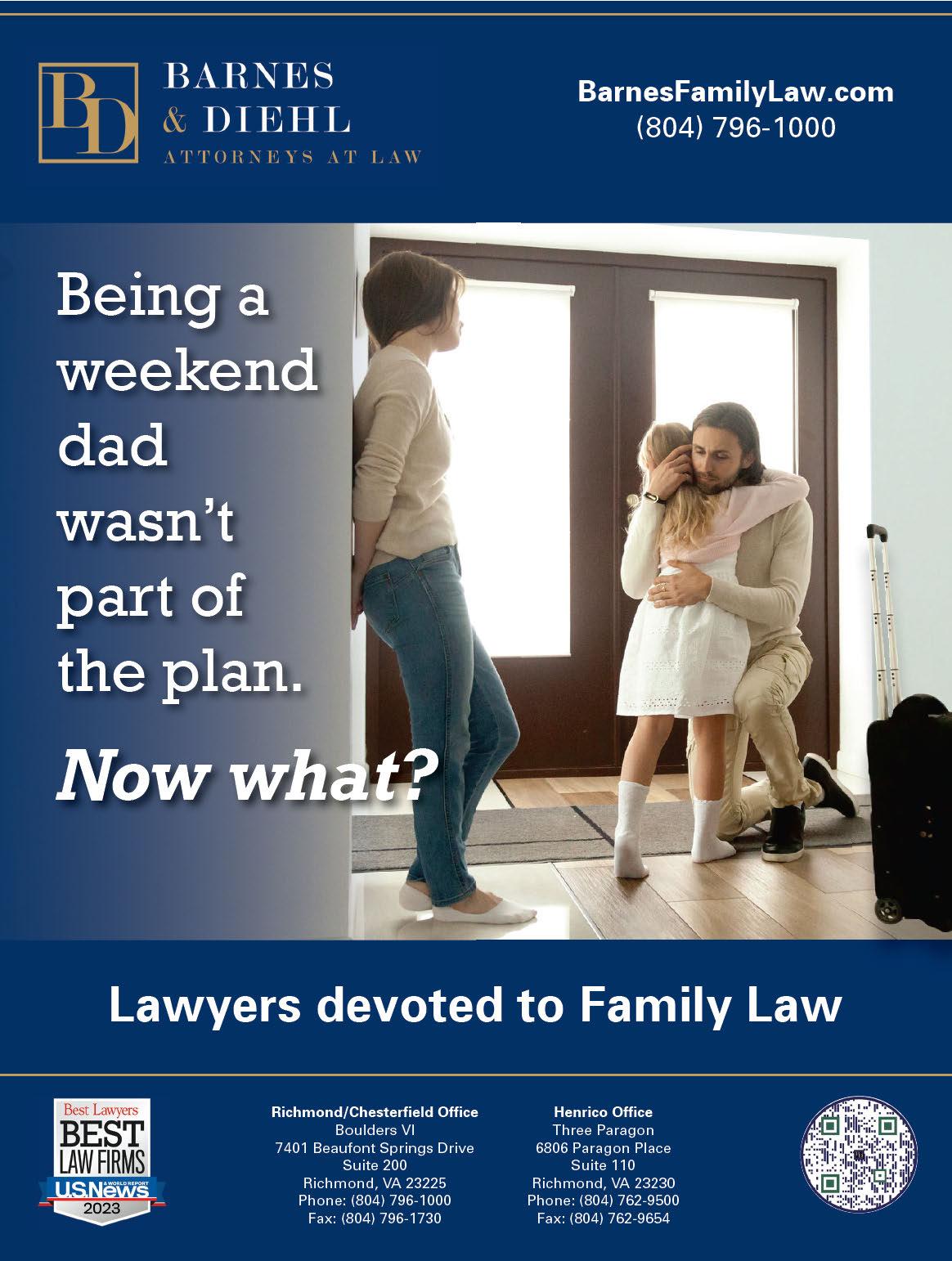

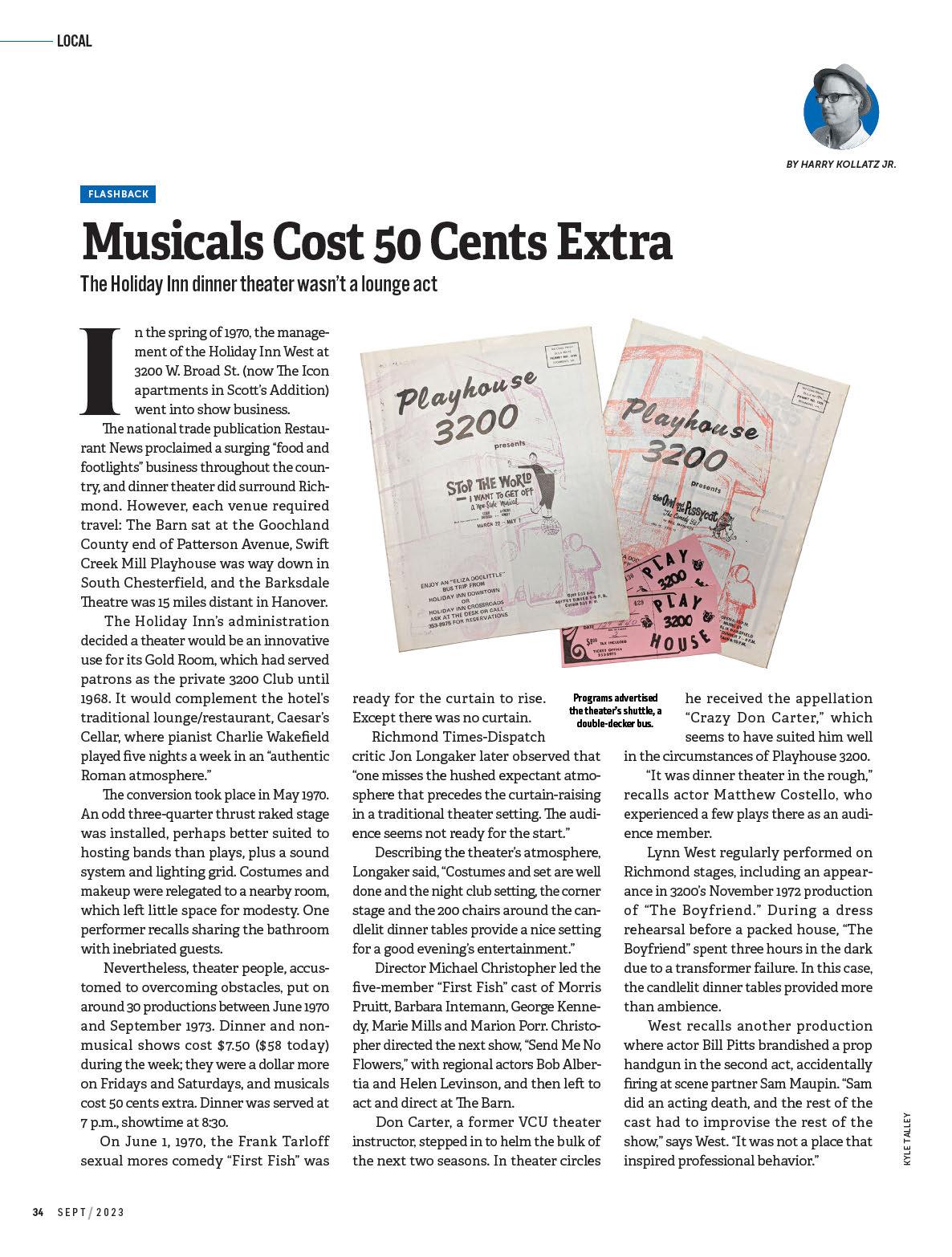

e Holiday Inn promoted their theater through advertising and specials. Guests at the newly opened Holiday Inn Crossroads as well as the downtown location could take an “Eliza Dooli le” English double-decker bus to 3200. Whether there was more to the promotion than the vehicle is unclear. e Cascade Room at the Holiday Inn Downtown (now the Graduate Richmond) added a Saturday night cabaret-style review that included comedy, music and magic, billed as Playhouse 301.

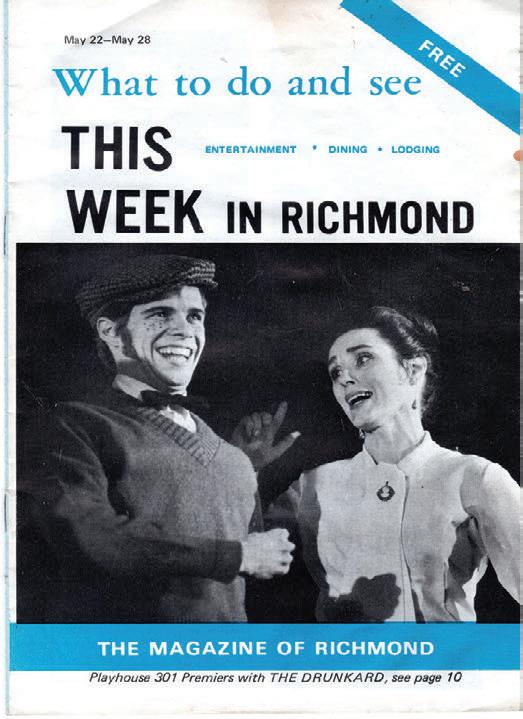

At least one 3200 hit was transferred downtown. “The Drunkard” was a century-old anti-drinking play that reviewer Bob Brickhouse described as a “zany mixture of melodrama, farce, music hall and revival meeting spirit.”

Barbara Baroody, who played “ e Widow’s Daughter — An Innocent Flower,” appeared in both versions. “I have many fond memories of that show,” she says.

e cavalcade of music and comedy continued into spring 1972 and featured performers either known in the Richmond region or on their way. Among them were Ted Boelt,

Glen Crone (who became the longtime alhimers department store Santa), Del Driver, Maury Erickson, Anthony J. Kahwajy, Eileen O’Grady, Ed Sala and director/choreographer Randy Strawderman.

Then in March-April 1972 came the appropriately titled “Stop the World I Want To Get Off.” The Broadway show had made a star of entertainer Anthony Newley. But the Richmond production, directed by Don Clark and featuring Ken Kopec and the versatile Barbara Mappus, worried hotel manager Roger Briggs, thanks to its cast of 10 and six-member orchestra. e expense of the production caused Briggs to reconsider how theater could continue. He decided to bring in packaged New York shows to be rounded out by locals as needed.

“Our product needs to be commercial entertainment,” Briggs told TimesDispatch writer Carole Kass. “Stop the World” wasn’t. He didn’t want to compete “with ‘theater’ people like Barksdale and Swi Creek Mill,” but instead sought to provide light comedy a ractive to both hotel guests and Richmonders.

Briggs described Don Carter as “amenable and capable,” but the longtime director got the hook nevertheless. His successor, Jack Cannon, came from the Barn Dinner eatre franchise and had once owned a playhouse. Briggs noted that Carter had relied on 3200 for most of his income while Cannon wouldn’t.

Rehearsal space was another factor. Local talent usually worked day jobs, so Briggs bought 6 W. Cary St. (today, a ta oo parlor) for use while the theater was occupied. e New York professionals would rehearse at 3200 during the day while the current show played at night.

Today a 3200 veteran sco s at Briggs’ justifications. He knew a bartender there who said the theater’s alcohol sales far exceeded the production budgets.

Carter’s last show was Neil Simon’s “Barefoot in the Park,” featuring newcomer Carolyn Paule e and Ed Sala, a

V CU graduate who went on to write plays, perform on and o Broadway, and narrate books.

The “Broadway” cast took over for another Neil Simon play, “Last of the Red Hot Lovers.” Critic Longaker was apparently impressed with the change, saying it had “paid o handsomely”

But New York’s traveling companies didn’t save Playhouse 3200. A series of apparently well done but undistinguished productions culminated in an ambitious September 1973 mounting of “The Teahouse of the August Moon.” Auditions were advertised for small parts in another bedroom farce, “No Hard Feelings,” but the production never happened. In the Sept. 25, 1973, Times-Dispatch Carole Kass announced the closing of Playhouse 3200’s metaphorical curtains.

e former theater’s space was joined to the adjacent 250-seat Green Room for meetings, dining and parties. e change, manager Jim Russo said, would draw more customers and “that’s where the profit comes from.”

And that’s show biz. R

An informal rule of the road holds that if you want to eat like a local, look for a restaurant parking lot populated with a smattering of law enforcement patrol cars. These road veterans chalk up hundreds of miles of driving about their jurisdictions and are well familiar with the highways and byways, people and attractions, and, of course, the best places to eat.

It may be an unwritten rule, but it’s true, says Bryan Hutcheson, sheri of Rockingham County and the city of Harrisonburg. “Patrolling the area, you do get to know where the best co ee and dining are,” he says.

There’s a lesser-known corollary to that rule that comes into play each fall. Few folks know which routes o er the best views of fall foliage at its finest more than the state troopers and local sheri s and deputies in the Virginia highlands. So, we asked for some suggestions for your autumn getaways from three local sheri s and a state trooper who shared where they take friends and family to enjoy the amazing hues of yellow, orange and red. Here’s what they had to say.

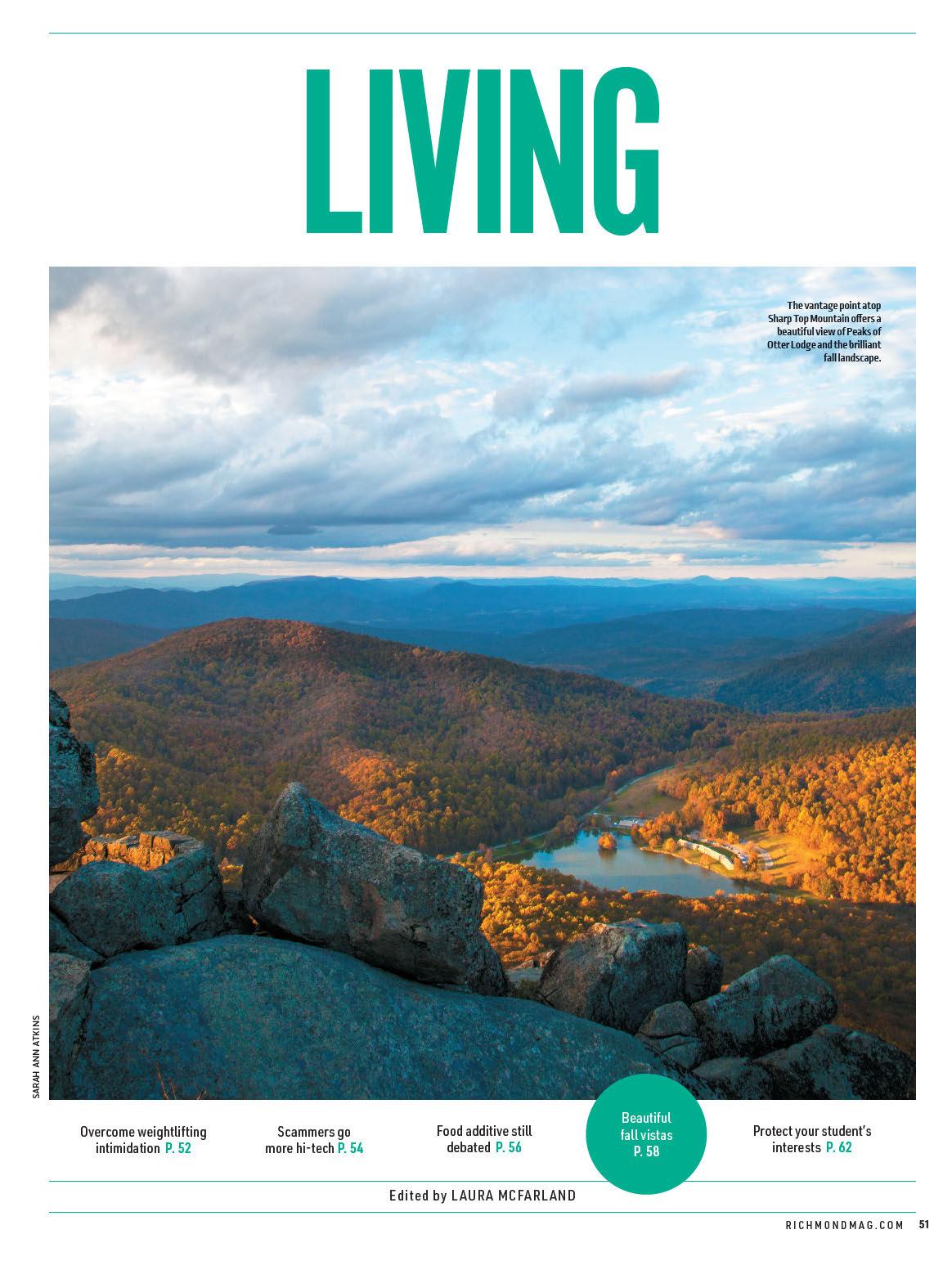

Outstanding scenery abounds in the heart of the Shenandoah Valley, and it’s best experienced on two byways, Skyline Drive

and U.S. Route 33, Hutcheson says. Start with Skyline Drive o Interstate 64 at Rockfish Gap. Proceed north 39 miles to the Swift Run Gap access, then take U.S. 33 west into Harrisonburg. Skyline Drive’s speed limit is 35 mph, so enjoy the cruise, and take some breaks along the way (explore a trail or a waterfall or two around Jones Run and Black Rock Summit). “The drive alone is beautiful this time of year,” Hutcheson says.

If time allows, U.S. 33 west of Harrisonburg is an enjoyable excursion for motorcyclists and other motorists who enjoy an expanse of winding roads and mountain scenery. There’s an abundance of opportunities to hike and camp in the George Washington and Je erson National Forests along the route into West Virginia.

Hutcheson loves The Galley Diner, a locally owned bistro “that pretty much has everything,” he says. The diner serves breakfast, lunch and dinner Monday to Saturday and breakfast and lunch on Sundays. Mr. J’s Bagels & Deli, which has four locations, touts its bagels and cream cheese as being made fresh each day.

Lodging options include Massanutten Resort about 14 miles east of Harrisonburg, Hotel Madison and Shenandoah

Conference Center near the James Madison University campus, The Village Inn south of the city, and Airbnb homes, cabins and campsites.

An Amish community in a bowl-shaped valley atop a mountain and 32 miles of twisting (some 300 curves) scenic highway are favorite fall experiences in Tazewell County, says Sheri Brian Hieatt.

The Amish enclave is in Burkes Garden, touted as Virginia’s highest valley and often used for biking and hiking along the Appalachian Trail. Check out Burkes Garden General Store for baked treats and other goods.

Back of the Dragon (state Route 16) takes you south from Tazewell across three mountains and ends near Hungry Mother State Park. Like U.S. 33, it’s a favorite of cyclists and sports car enthusiasts for its fall views.

You’ll find phenomenal views along the upper reaches of the Blue Ridge Parkway, according to Nelson County Sheri David W. Hill. “The parkway gives you the best JACK

By Emily McCrary-Ruiz-Esparza

By Emily McCrary-Ruiz-Esparza

The deaths of two VCU students in one semester left many Richmonders wondering what is being done about pedestrian safety in the city

he reward for making it through a tough exam was fried ravioli from Aladdin Express on West Broad Street. On a Monday night in February, with takeout in hand, VCU sophomore Nicole Madda waited for the walk signal and crossed Broad, heading north toward her apartment. At the corner of West Broad and North Harrison streets, a car hit her, and her head hit the windshield.

Madda says she su ered a traumatic brain injury, a brain bleed and a concussion. Her mother flew in from India, and Madda was sent home to Northern Virginia to recover, missing a month of classes. Six months later, she struggles with hearing loss as well as neck and back pain that seems to get worse.

Just three weeks before Madda’s injury, another VCU student had been killed on the other side of campus. By May, a second student would be dead, hit and killed on the same street three blocks east, when two cars collided. He just happened to be standing on the sidewalk nearby. “To be in the situation where I was so close to that is crazy,” says Madda.

A er two fatal accidents in a single semester, many Richmonders wonder what is being done to keep pedestrians safe on the road.

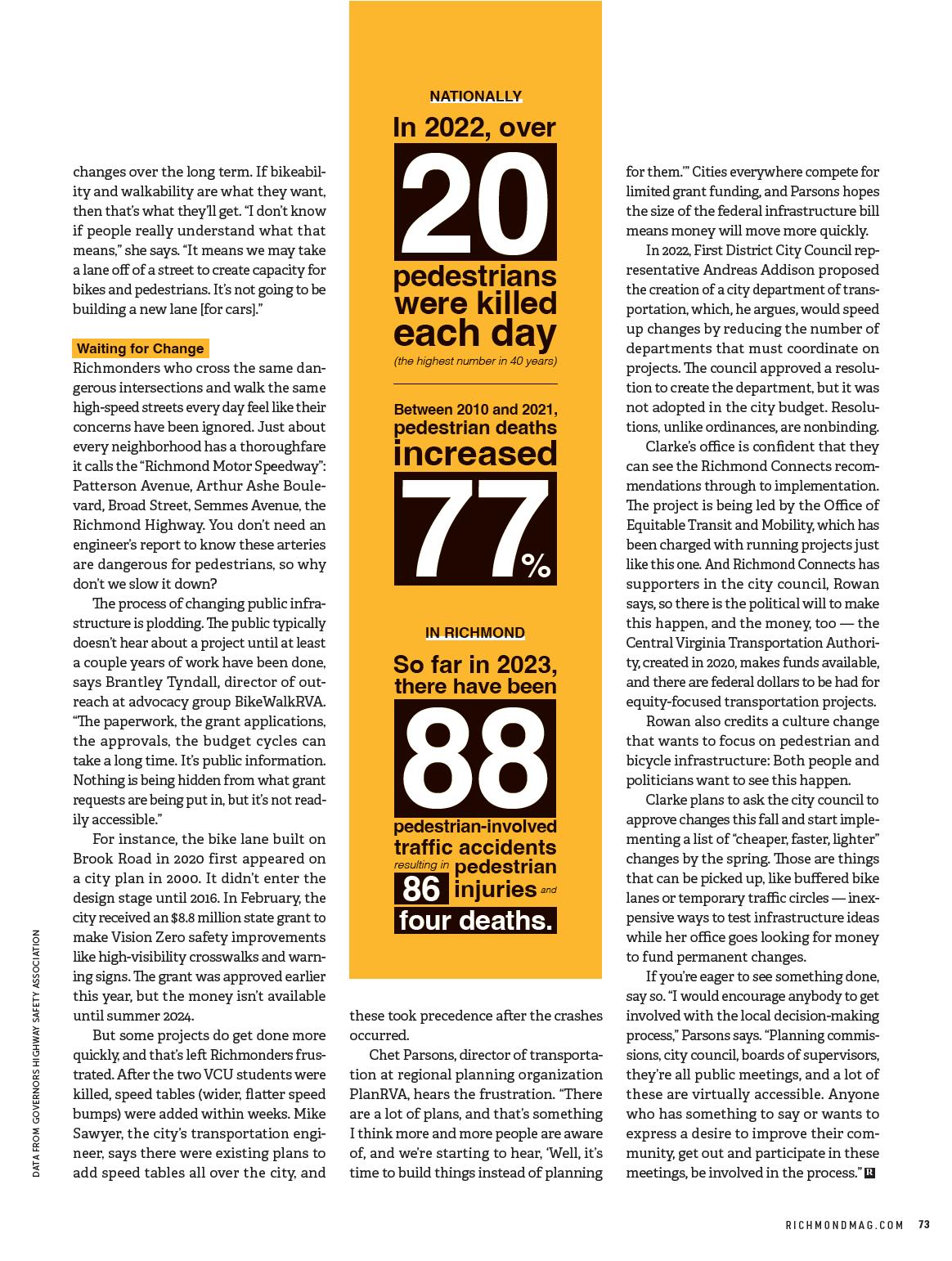

e United States has become a dangerous place to be a pedestrian. In 2022, more than 20 pedestrians were killed each day, the highest number in 40 years, according to the Governors Highway Safety Association. Between 2010 and 2021, pedestrian deaths increased 77%. In Richmond, there

have been 88 pedestrian-involved tra c accidents since the beginning of the year, resulting in 86 pedestrian injuries and four deaths.

Overall, driver fatalities increased 33% from 2011 to 2021, when 42,939 people died on American roads, including 7,388 pedestrians killed in tra c crashes. e most common contributing factors were alcohol, speeding, falling asleep, distracted driving and poor visibility, according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. What’s behind the pedestrian death toll? ere’s no single factor, but a confluence of many.

involved in fatal pedestrian crashes increased 82% between 2009 and 2016 — more than any other vehicle type.

We’re also driving our big cars much faster. In 1974, the national speed limit was 55 mph. Since 1995, states have set their own limits, and it’s not uncommon for them to be well above the old ceiling. In Virginia, the maximum for highways is 70 mph. e Insurance Institute of Highway Safety estimates that 25 years of rising speed limits have cost us 37,000 lives.

e higher the speed limit, the higher the risk of severe injury to pedestrians:

e odds of a pedestrian dying in a motor vehicle crash increase by an average of 11% for every 1 kilometer added to impact speed — that’s less than 1 mile per hour. A study in Toronto found that speed limit reduction by 25% lowered the rate of pedestrian-vehicle accidents by 28%.

Pedestrian actions can also play a role. Just as there are distracted drivers, there are distracted pedestrians, too, walkers paying more a ention to their phones than to tra c and their surroundings. But tra c fatality trends indicate that our tendency to blame pedestrians may be misplaced. It’s dangerous to be a motorist, and car accidents are ge ing more deadly.

For one, we’re driving more. American motorists logged 3.26 trillion miles on the road last year, 280 billion more per year than a decade ago. In Richmond, the average household accounts for about 31,000 road miles per year. We’re also walking more, about 1 to 5 more miles per day than we did before the pandemic. More cars and more people on the road create more opportunities for deadly collisions. Another factor is the size of our rides. Americans love SUVs, which may be safer for drivers but not for pedestrians. SUVs sit higher, making it harder for drivers to see pedestrians, especially short adults, children and people in wheelchairs. They’re also heavier, about twice the weight of a sedan. e number of SUVs

Urban and suburban design has a major influence on pedestrian safety. “Our cities are not fully designed for a safe pedestrian experience,” says Adie Tomer, who studies infrastructure policy at the think tank Brookings Metro. Especially in cities and towns developed a er the widespread adoption of automobiles, new developments are scaled for cars, not people.

Compare Carytown and the stretch of West Broad Street at Willow Lawn. Where would you rather be a pedestrian? Both are shopping districts, but Cary Street is scaled for people, West Broad Street for cars. Where houses and shops are bigger and farther apart, driving is more convenient or simply required.

Modern development has put people

“Our cities are not fully designed for a safe pedestrian experience.”

—ADIE TOMER, BROOKINGS METRO

in low-income households (disproportionately people of color) and the elderly most at risk due to an e ect known as the suburbanization of poverty.

It works this way: White flight from city centers in the 1950s and 1960s led to car-centered suburbs. In the 21st century, the a uent are migrating back to city centers for perks like walkable streets, shopping and human-scaled infrastructure. Prices in urban areas rise, and people with low incomes are priced out, pushed out to the suburbs where, if you want to get around, you need to drive. You also have to be able to a ord a car.

Civic leaders across the country are

trying to solve the problem of pedestrian safety from di erent angles.

In Washington, 100,000 drivers with at least two tra c camera tickets since 2021 are getting warning notifications that they’re endangering themselves and others. Some states are imposing harsher punishments for reckless driving. In June, a man in Florida was given a 30-year prison sentence for an accident he caused in 2016, which killed a 9-year-old boy and injured three other passengers. In Richmond, a driver received a 25-year sentence for an accident he caused in 2020 that killed two people and injured a third.

is summer, more than 130 teenagers spent four days at James Madison University learning how to be community advocates for tra c safety during a retreat sponsored by Youth of Virginia Speak Out About Tra c Safety.

Some cities have adopted a plan called Vision Zero. Richmond is one of them.

Vision Zero is a global safety project whose goal is to eliminate tra c-related deaths and injuries. If that sounds ambitious, it is, but it’s also possible: Jersey City in New Jersey went a full year without a tra c death in 2022. Hoboken, New Jersey, hasn’t had one since 2019.

ese cities haven’t overhauled their streets to see a di erence. Many changes are small: Slowing tra c on narrow

avenues or preventing cars from parking close to intersections so they don’t block drivers’ line of sight. “We need roadways designed to protect drivers and pedestrians from one another,” says Tomer at Brookings Metro.

Richmond’s department of public works is seeking federal grant funding for a slate of small-scale projects designed to meet Vision Zero goals. Among them are building sidewalks and traffic islands around St. Catherine’s School in Westhampton, adding pedestrian crossings and curb ramps at Route 1 and Dinwiddie Avenue and at Westminster Avenue, adding bike lanes downtown and along Pa erson Avenue, and pouring sidewalks in Sco ’s Addition and in Maymont. Grant determination is expected in June 2024.

City leaders have long emphasized the importance of pedestrian safety, but residents are ready to see it happen.

Infrastructure changes take years, and Richmonders wonder if we can wait that long. ere’s a new project in the works that may deliver changes as early as next year.

“Our office is all about those small wins,” says Dironna Clarke, who leads the city’s O ce of Equitable Transit and Mobility. “If we keep ge ing small wins, small wins, small wins, small wins — we will win every time.”

She may talk of small wins, but Clarke’s plan for pedestrian safety is ambitious. A er three years of looking for funding, Clarke created Richmond Connects, a multiyear project to make it easier and safer to get around Richmond without a car.

Her team spent a year studying the needs of walkers, cyclists and transit riders. ey looked at our most dangerous streets and intersections, the areas most a ected by suburbanization of poverty

and redlining, the ones blown apart by interstates, neighborhoods where investments could increase access to jobs and housing, air quality and water quality. ey found areas where safety and security issues coincide — maybe there is a sidewalk, but it’s poorly lighted.

ey took their data, opened it up for public comment and went out into the community asking, where do you see problems? e ones they heard repeatedly were prioritized. A cluster of public comments, a concentration of violent crimes or property crimes could also bump something up the list.

Crunching crash and crime numbers doesn’t catch it all, says Kelli Rowan, who is leading the data collection process. ey needed to hear from residents. “If there’s a ton of people that keep saying it over and over again, there’s probably a problem there that we just haven’t captured in the data yet.”

In June, Richmond Connects released a needs identification report that includes a detailed list of problems that need a ention — intersections that don’t feel safe, roads where cars o en speed, crosswalks not conducive to wheelchair users.

Next, the team will collect ideas for improvements. So, this intersection is unsafe for walking — should we put in a crosswalk? Lower the speed limit? “We’re in the stage where we’re saying, ‘We know that there is a problem. Here are a few solutions. What do you want to prioritize and how do you want to get it done?’” Clarke says.

e city’s master plan, Richmond 300, states that plans will prioritize people over cars, and Clarke wants to hold them to it. “Richmond 300 said that we were going to move away from cars and go to a walkable city. at’s the vision they have for Richmond. is plan is ge ing us that,” she says.

e plan makes 140 recommendations for non-motor transportation improvements, though not all will make it into the final document. Clarke envisions major Dironna Clarke leads the city of Richmond’s Office of Equitable Transit and Mobility.

Local theater productions o er a variety of experiences

From dramatic storytelling to comic farces, chances are there’s a theater production available locally that will satisfy any appetite. Fall is an ideal time to start planning your entertainment schedule as the new seasons debut at theaters around the region.

After vacating their Henrico homebase, the Chamberlayne Actors Theatre (cat theatre.com) is taking a comedic approach to their 2023-24 season, dubbing it “A Season of Comedy” and taking on a playful temporary rebrand to Stray CAT, as the performances are hosted at venues around the area. The lineup kicks off with the Steve Martin play “Meteor Shower” at Brightpoint Community College from Sept. 16-29.

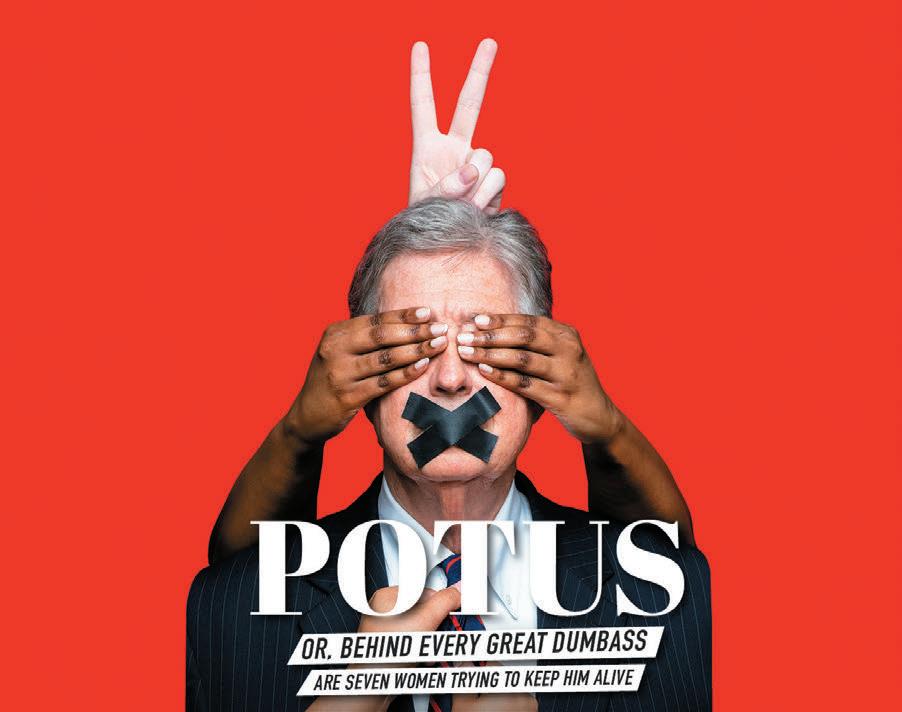

With four locations offering a packed programming roster, Virginia Repertory eatre’s new season (va-rep.org) includes musicals, plays, special events and collaborations. The Signature Season at the November Theatre debuts with the regional premiere of the Tony Award-nominated “POTUS: Or, Behind Every Great Dumbass Are Seven Women Trying to Keep Him Alive,” which runs Sept. 1-Oct. 1.

Richmond Triangle Players’ new season (rtriangle.org) sticks to its mission of presenting unique, thought-provoking productions. It opens with “One in Two,” billed as “a defiantly embracing call to action,” running Sept. 20-Oct. 14.

SEPT. 15 - OCT. 1

The Henrico Theatre Company’s production of “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” set during 1967, puts liberal sensibilities to the test when a white couple’s daughter brings her Black fiance home to meet them. The Cultural Arts Center at Glen Allen. $10. artsglenallen.com

OCT. 20 - NOV. 12

Part of the Children’s Season at the Virginia Rep Center for Arts and Education, “The Emperor’s New Clothes” tells the story of an emperor who hires tailors to make him a remarkable set of clothes under the pretense that the garments will be invisible to anyone who is incompetent. $TBA. va-rep.org

NOV. 15 - DEC. 23

One of Richmond Triangle Players’ biggest holiday hits returns with a production of “Scrooge in Rouge,” a reimagining of the Charles Dickens classic “A Christmas Carol.” $TBA. rtriangle.org

NOV. 16 - 19

Berta” from Sept. 27-Oct. 15. Presented in collaboration with The Conciliation Project, the play follows Leroy, who, a er commi ing a reprehensible crime, seeks to make amends with his former lover Berta. Two world-premiere performances follow, including “Memories of Overdevelopment,” running Feb. 7-25, and “Roman à Clef” from May 8-26. For a full schedule of events, visit firehouse theatre.org

This month, the theater stage is being named in honor of founder Carol Pier -

sol, who died in May from brain cancer. Shaw says a to-be-announced Pulitzer Prize-winning production from Piersol’s early days with Firehouse will close out the season. The 5th Wall Theatre, which Piersol founded in 2013 following a falling out with the Firehouse’s board, will be the first resident company of the 202324 season. It will be joined by three other resident arts groups, Yes, And! Theatrical Co., Starr Foster Dance and K Dance.

“It really is a time of great growth and expansion at Firehouse,” Shaw says.

The University of Richmond’s Department of Theatre & Dance presents the Pulitzer Prizewinning drama “Fairview.” The play seemingly starts as a sitcom, following a Black middle-class family as they prepare for a birthday dinner, but evolves into a deeper examination of race and white supremacy. The performances are free, but reservations are required. modlin.richmond.edu

DEC. 7 - 17

The Weinstein JCC’s Jewish Family Theatre presents the Tony Award-winning musical “Cabaret,” which delves into the world of bohemian Berlin as Germany slowly yields to the emerging Third Reich. The production is recommended for ages 12 and up. $30. weinsteinjcc.org

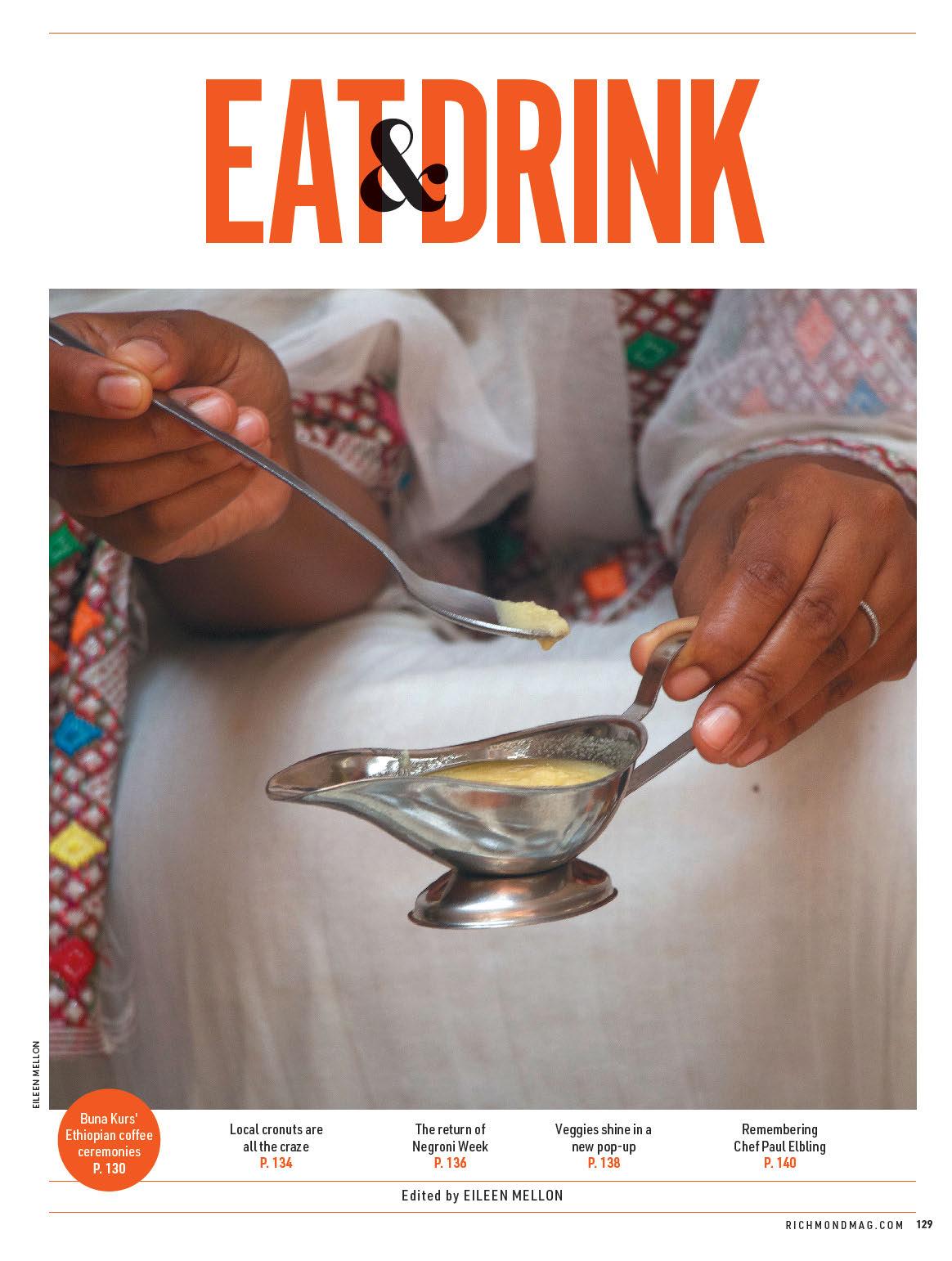

to hone, like perfecting a bread recipe — there are errors along the way, from muddy pours to charred beans.

“Not just anybody can do this,” says Faisal, who notes she prefers her elder sister to take the lead. “It’s a process, making Ethiopian coffee; you have to know the sounds.”

A er finely grinding the beans (Kochel uses an electric grinder, but a mortar and pestle is common) Kochel adds them to a jebena, an Ethiopian clay pot with a long neck and spout, that contains boiling

water. During non-ceremonial days it can be spo ed si ing on the co ee bar at Buna Kurs.

When she deems it ready, Kochel begins to pour the co ee into the sinis si ing atop her rekebot, a low-lying table used during the ceremony. In one graceful, continuous motion, she fills the cups in an uninterrupted flow. The grounds settle to the bottom of the vessels as a basket of popcorn is passed around — but only once the coffee is complete. While “buna” translates to

coffee, and “kurs” to breakfast, Faisal says, “Bunakurs is also a snack you have with your co ee ceremony.”

Bits of refined bu er are dropped into the cups along with a sprinkle of salt before each is passed o . And just like that, two hours on a Sunday have passed, the single sini well worth the wait. Taking a slow and thoughtful sip, Kochel says, “ is is the perfect blend. I’ve been drinking co ee since I was 8, so I know when co ee is good.” R