VIEWS

Intersectionality

DECISION-MAKING WHILE INTERPRETING IN SOCIAL SETTINGS

Tiffany Hill & Kenton Myers

THE BLACK ASL PROJECT: AN OVERVIEW

Dr. Carolyn McCaskill, Dr. Ceil Lucas, Dr. Robert Bayley, Dr. Joseph C. Hill

REFLECTIONS ON KURDISH ITP PILOT DEVELOPMENT: DEAF LEADERSHIP & CROSS-CULTURAL COLLABORATION Emma DeCaro

VOLUME 41 | ISSUE 1 | WINTER

2024

OUR TEAM

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

President | Ritchie Bryant, CDI, CLIP-R

Vice President | Dr. Jesús Rēmigiō, PsyD, MBA, CDI

Secretary | Jason Hurdich, M.Ed, CDI

Treasurer | Kate O’Regan, MA, NIC

Member-at-Large | Traci Ison, NIC, NAD IV

Deaf Member-at-Large | Glenna Cooper

Region I Representative | Christina Stevens, NIC

Region II Representative | M. Antwan Campbell, MPA, Ed:K-12

Region III Representative | Vacant

Region IV Representative | Jessica Eubank, NIC

Region V Representative-Elect | Rachel Kleist, CDI

HEADQUARTERS STAFF

Chief Executive Officer | Star Grieser, MS, CDI, ICE-CCP

Human Resources Manager | Cassie Robles Sol

Affiliate Chapter Liaison | Dr. Carolyn Ball, CI & CT, NIC

Director of Member Services | Ryan Butts

Member Services Manager | Kayla Marshall, M.Ed., NIC

Member Services Specialist | Vicky Whitty

CMP Manager | Ashley Holladay

CMP Specialist | Emily Stairs Abenchuchan, NIC

EPS Manager | Tressela Bateson

EPS Specialist | Martha Wolcott

Certification Manager | Catie Colamonico

Certification Specialist | Jess Kaady

Communications Manager | Jenelle Bloom

Publications Coordinator | Brooke Roberts

Director of Government Affairs | Neal Tucker

Government Affairs Coordinator | Jimmy Wilson IV, MPA

Director of Finance and Accounting | Jennifer Apple

Finance and Accounting Manager | Kristyne Reeds

Staff Accountant | Bradley Johnson

CASLI Director of Testing | Sean Furman

CASLI Testing Manager | Amie Smith Santiago, MS, NIC

CASLI Testing Specialist | Sami Willicheva, MAOL

2

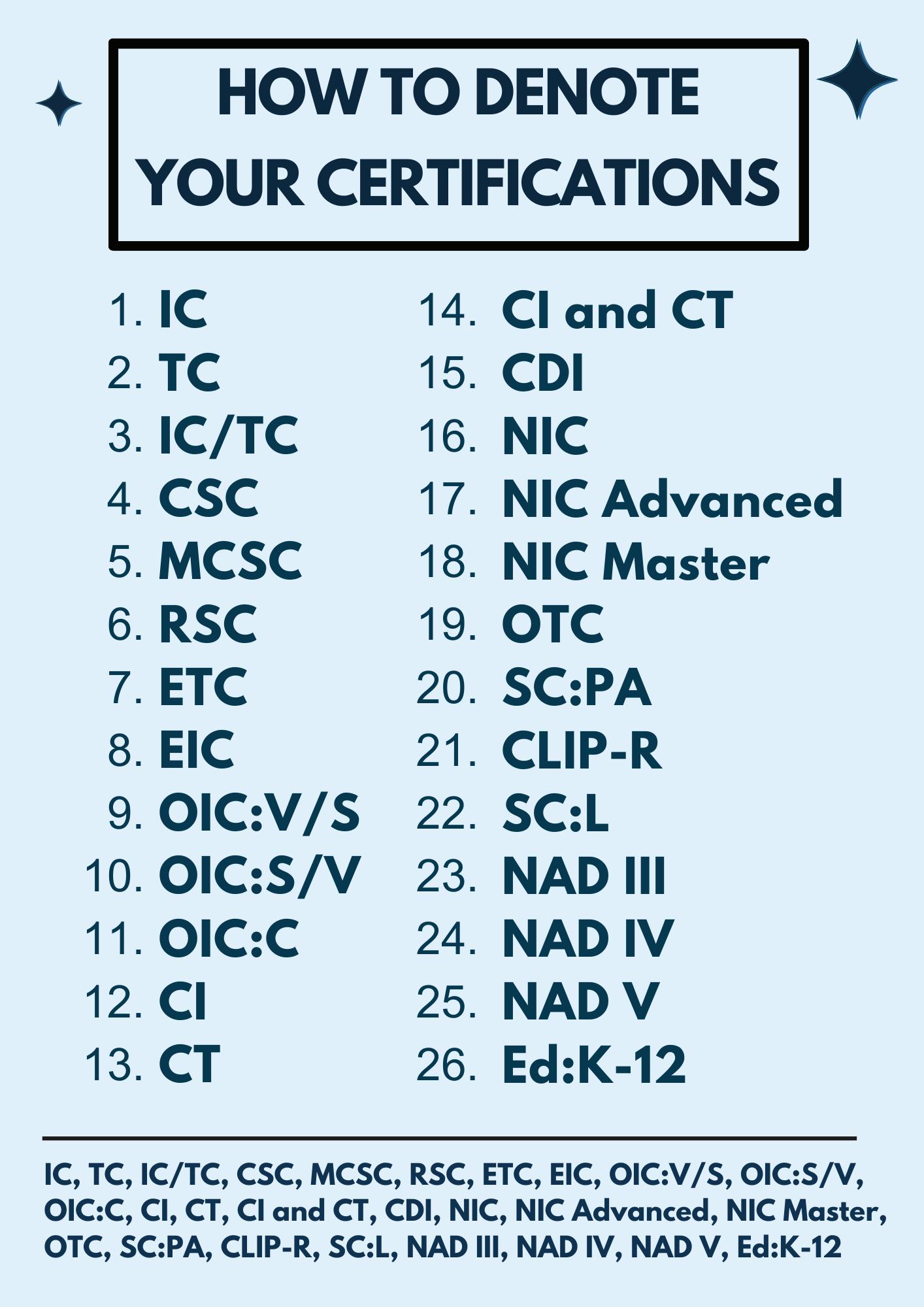

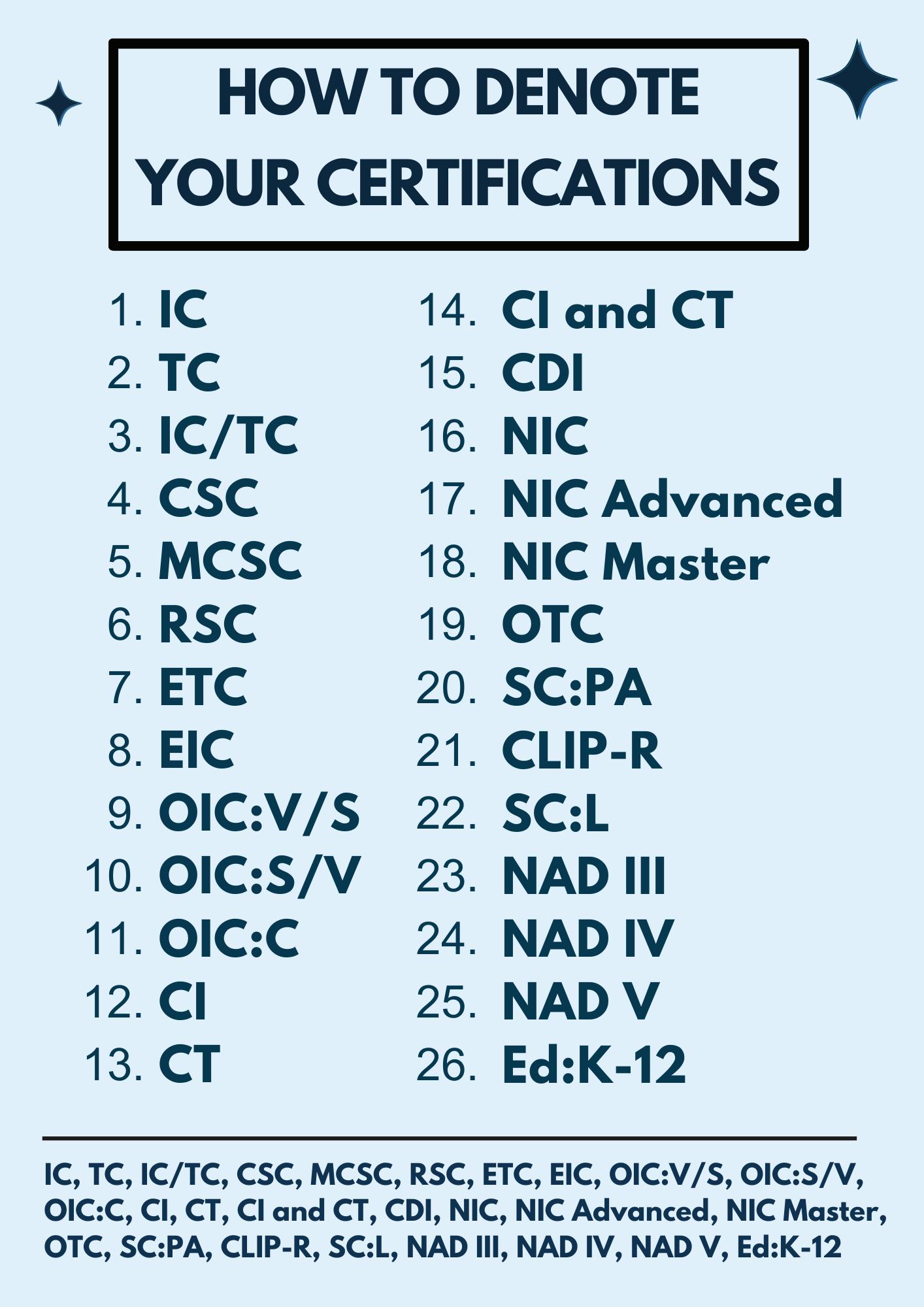

3 CONTENT 22 26 From the desks of HQ DecisionMaking While Interpreting In Social Settings 04 President’s Report CEO’s Report Region Reports 06 08 30 Webinars Scholarships & Awards 31 32 34 Newly Certified Denote Certifications CMP 36 38 Ethical Violation 39 16 10 Reflections on Kurdish ITP Pilot Development: Deaf leadership and Cross-Cultural Collaboration The Black ASL Project: An Overview EATE

PRESIDENT’S REPORT

4

Ritchie Bryant | RID President CDI, CLIP-R

Welcome to RID VIEWS, where we delve into the heart of sign language interpreting and explore the multifaceted world of intersectionality. As we navigate through this terrain, we must acknowledge the imperative role of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility, and Belonging (DEIAB) principles within RID’s strategic planning objectives.

Our commitment to implementing DEIAB principles is rooted in the recognition that diverse voices enrich our organization and strengthen our collective knowledge base. We champion the inclusion of communities of color, interpreters of color, individuals with neurodiversity, and

people with disabilities, recognizing that their perspectives contribute invaluable insights to our profession.

Each person brings to the table a multitude of identities, making it impossible to compartmentalize or prioritize one over the other. This acknowledgment underscores the importance of embracing intersectionality and creating spaces where individuals can authentically represent the complexity of their identities.

Throughout my tenure, I’ve remained keenly aware of the diverse tapestry of individuals within our community. Every person’s unique blend of experiences and identities shapes their communication styles and interactions with the world. This awareness propelled me to delve into the concept of intersectionality in interpreting, recognizing its profound implications for our profession.

Intersectionality, coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (Crenshaw, 1989), illuminates the intricate interplay of different identity facets. It extends beyond mere labels of race, gender, or Deaf identity, delving into how these facets intersect and influence one’s experiences. In interpreting, this understanding is pivotal, as it sheds light on how our work is intricately tied to the diverse identities and experiences of those we serve.

Our exploration of intersectionality in interpreting unveils the myriad of ways in which our practice is shaped by the complex web of human experiences. Beyond being intellectually stimulating, this exploration is crucial for enhancing our practice and delivering optimal service to our clients.

Furthermore, understanding intersectionality enables us to confront and challenge our own biases and assumptions. As interpreters, our identities and experiences inevitably influence our work, often unconsciously. By embracing intersectionality, we can actively dismantle biases and strive to provide more equitable and responsive interpreting services.

In conclusion, as we embark on this journey of exploration and introspection, let us remain steadfast in our commitment to DEIAB principles and the recognition of intersectionality’s significance in our profession. Together, we can cultivate an inclusive environment where every voice is valued, and every identity is celebrated.

Reference:

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chcago Legal Forum, 1989(1), Article 8.

5

CEO’s Report

Recently, I experienced something as a Deaf person that was very personal and very harrowing. I woke up one Saturday morning with intense pain in my eyes. Thinking that it might be some kind of sinus headache I’ve never experienced before, I treated it - with minimal effectiveness - with over-the-counter medications until about a week later, on Friday, I woke up with partial vision loss in my left eye. I called an ophthalmologist who gave me the next available appointment on a Monday morning. Upon some preliminary testing, I was sent to the emergency room. Upon arriving at the emergency room, I was bumped to the front of the line. The stark reality sank in that permanent vision problems - or worse, some serious underlying condition - were a very real possibility. I was brought in, seen by no fewer than eight different doctors, and scheduled for all sorts of neurological and vision tests.

This isn’t a story about my eyes. My eyes are fine and in the end I was treated and diagnosed with a condition that causes Optic Neuritis, or inflammation of the optic nerves and all prognosis are optimistic. My vision has made a full recovery and the ordeal ended with the best possible outcome. For that I am very, very grateful.

There is also an element to this story that most people reading probably will probably never need to think about for themselves, but do provide on a day-to-day basis through their work: effective communication access.

I arrived at the emergency room and told the person at the front desk that I am Deaf and required an ASL interpreter. They immediately texted for an interpreter and one showed up for my triage interview. The interpreter was very proficient - clearly a certified and experienced professional, and unlike experiences in other

Star Grieser | RID CEO MA, CDI, ICE-CCP

Star Grieser | RID CEO MA, CDI, ICE-CCP

emergency rooms, I was able to focus on just being a patient. There was no need to ask, beg, negotiate, argue, persuade, convince, make threats for my rights to communication access in the emergency room. It was readily available by design.

The interpreter stayed with me and at the end of their shift, was relieved and replaced by another highly qualified professional and proficient interpreter and this repeated daily until my release (Optic Neuritis requires a multi-day treatment of IV steroids only administered inhouse, under observation). This was my experience for my entire stay at the hospital. Granted, I live in an area with a large population of Deaf ASL-users and there were other Deaf patients in and out of the emergency room, as well, and the interpreters were tag-teaming between us to provide communication access for our various needs. Seemingly, there was a comparatively well designed system set up that fostered not just effective communication access, but successful communication access.

I say comparatively because this experience is, unfortunately, the exception, rather than the norm.

In this specific emergency room, I never had to argue with hospital personnel as to why I need an interpreter, or justify why the interpreter should be nationally certified. I didn’t have to wrestle with an Ipad, deal with bad internet connectivity, explain to a doctor how to use an interpreter, or request another interpreter due to lack of sign proficiency or professionalism (and then argue again with hospital personnel as to why the current/present interpreter was ineffective). In my 48 years on this planet, while either accompanying someone or for myself, I can only remember witnessing or experiencing this level of successful communication access in

6

emergency rooms twice.

Only twice.

This is a reality for many Deaf people. Whether we have effective communication access in emergency rooms and hospitals, never mind doctors appointments and follow-up, is literally hit or miss and often involves an exorbitant amount of self-advocacy to achieve. Deaf patients are so often forced to deprioritize their pain or medical condition at the moment to advocate for basic communication access. Within our community, every Deaf person has a horror story of something that happened to themselves or to a loved one who is Deaf, DeafBlind, Hard of Hearing, etc., and has been impacted by barriers to successful communications access in medical care. I have seen countless stories throughout my years of Deaf patients going to an emergency room and being told to wait for an interpreter before they can even be checked in, resulting in the emergency that brought them to the ER in the first place to go unattended for hours because there was no successful communication system in place.

A question I ask myself in the wake of this experience is: how can RID better work towards creating a norm for successful communication access, especially in high-risk/high consequence settings such as within hospitals and within all areas of healthcare? What advocacy work can be done to set standards, guide our professional practices, what laws can we lobby for that help to ensure that hospitals are held to better standards of access for our Deaf con-

sumers? How do we better utilize deaf interpreters to enhance effectiveness? What tools can we develop to educate consumers towards better self-advocacy? Who can we partner with for collaborative advocacy efforts? And how do we give our advocacy efforts “teeth” in this arena?

As the nation’s sole professional organization of ASL interpreters and as advocates and stakeholders in the profession, it is incumbent upon RID to set clear standards, advocate for legislative reforms, and promote the use of qualified interpreters - including Deaf interpreters - in order to make meaningful progress towards a healthcare system that is truly inclusive and accessible to all, everywhere.

Moreover, empowering Deaf individuals with the tools and knowledge to advocate for their rights is essential in fostering a culture of self-advocacy and resilience. Through education and awareness initiatives, we can empower Deaf patients to navigate the complexities of healthcare with confidence and assertiveness.

In the pursuit of a more equitable healthcare landscape, the journey ahead may be challenging, but it is not insurmountable. Together, let us commit ourselves to the cause of ensuring that every Deaf individual receives the quality care and communication access they deserve, regardless of the barriers they may face. Only through concerted effort and collective action can we truly create a healthcare system that leaves no one out of successful communication access.

7

Region I

Christina Stevens, NIC Region I Representative

Region Reports

Connecticut - Continues to have monthly social gatherings. Follow them on Facebook at ConnRID to see when the next meet up is.

Massachusetts- Continues its search for an executive board. If you are interested, email President@massrid.org Their CMP continues to maintain CMP requests for workshops and events. You can see updates on their website: https://www.massrid.org/ or Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/groups/massrid

~Shana Gibbs, President

New Hampshire- please watch your email for upcoming events.

New Jersey- We were glad to welcome Region 1 Rep Christina to our Nov all day workshops and membership meeting. During that meeting we were able to vote in a full new board and look forward to their great work!

Genesee Valley- GVRRID is currently seeking a Vice President and Treasurer for our current board. In addition, we will soon be electing a new President and Secretary. We are hoping to find replacements for these positions to ensure GVRRID can continue operations. Elections will happen in March and conclude in April for a start date of July 1st. We recently piloted

a social event for interpreters in the greater Rochester area that had some success. We are hoping to continue hosting social events for members of our interpreting community to connect. Find us at gvrrid.org and https://www. facebook.com/gvrrid/. ~Eliza Fowler, President

Long Island- LIRID finished off 2023 with a website re-design and an end-of-the CEU-cycle workshop series! Keep an eye on our new events calendar, and follow us on Facebook and Instagram @_LIRID_ for announcements about our upcoming workshops, meetings, and fundraisers. ~Alyssa Lardi, President

Metro- Is currently seeking members for the board. Please reach out via email if you are interested.

Pennsylvania- The new Pennsylvania RID (PARID) board has been hard at work during the first few months of our terms! We are excited to announce many board positions have been filled including: President (Sarah Reed, NIC), Vice President (Kerry Patterson, NIC), Recording Secretary (Amanda Landrey, NIC), Corresponding Secretary (Laura Schupp, NIC), PA District 2 Rep (Megan Wetzel, CDI), PA District 5 Rep (Imanni Jones), PA District 6 Rep (Shannon Wheeler), and PA District 8 Rep (Maribel Flaherty, NIC, Ed:K-12). One of our top priorities has been working on finalizing the details of our annual PARID conference, slated for Fall 2024. Look for announcements with exact dates on our newly energized social media

8

Reports

accounts (Facebook, Instagram and YouTube), as well as our website (currently in the process of being updated)! In addition to the conference, we have been diligently working to fully understand our Bylaws, Policy and Procedural Manual, organizational history and current roles/ responsibilities. While we establish this strong foundation as an entirely new board, we are also looking towards the future. This includes ideas around increasing member engagement by listening to, working with, and better supporting the communities we work in and serve. ~Sarah Reed, President

Rhode Island- Is working diligently with the local RICDHH to reestablish a relationship with them and improve access for the Deaf community. ~Rosa Norberg, Co-President

Vermont- Please watch your email for upcoming social events and board announcements.

Region II

M. Antwan Campbell, MPA, Ed:K-12, Region II Representative

Hello from Region II. Region II has been really busy as several of our Affiliate Chapters are working on updating websites and PPM /Bylaws. Meanwhile, we are thrilled to begin preparations for our Region II conference that will take place this summer

from June 21-22, 2024. This conference will be hosted by NCRID, but it will be virtual so that everyone will be able to attend. We have lined up great presenters and workshops, so be on the lookout for more information in the days ahead. We are looking to have a blast, see you there!!

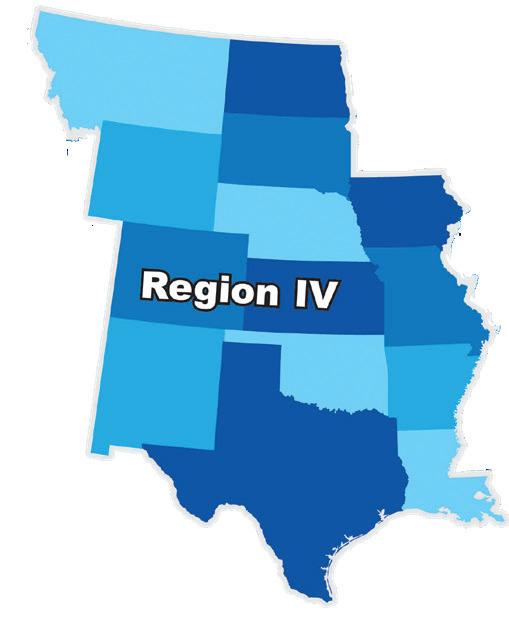

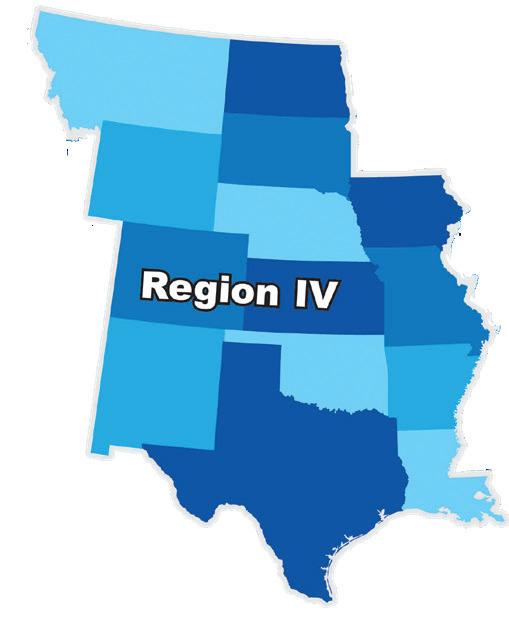

Region IV

Greetings from Region IV! We have determined that there will not be a Region IV conference in 2024. Instead, the Affiliate Chapters will offer their own conferences, workshops, and professional development opportunities. These will be advertised to the region as a whole, and in-region discounts will be offered for those who would like to attend. 2025 will be focused on the national biennial conference, but we do intend to host a Region IV conference in 2026.

Oklahoma RID (OKRID): OKRID will host their biennial conference to support the growth of Deaf and hearing interpreters in their knowledge base of American Sign Language, interpreting skills, and the current issues impacting Deaf, DeafBlind, and Hard of Hearing communities. The conference will be held in Tulsa, Oklahoma from June 20-22nd. Stay tuned by following their website here https://okrid. org/events. For questions or more information, please contact conference@okrid.org.

9

Jessica Eubank, NIC Region IV Representative

Reflections on Kurdish ITP Pilot Development: Deaf Leadership and Cross-Cultural Collaboration

Emma DeCaro M.A., NIC, BEI Advanced

Originally from Austin, Texas, but with much of her childhood spent in Asia, Emma holds a B.S. in Public Relations from The University of Texas at Austin (‘15) and an International Development M.A. from Gallaudet University (‘23). She has over six years of experience in communications and partnership marketing and eight years of experience as a certified interpreter. Since 2017, she has volunteered with Deaf refugees, immigrants, and asylees (RIAs) as they resettle in the U.S. Since 2021, she has been studying and collaborating with Jordanian and Kurdish Deaf communities on educational and human rights priorities. She is currently a freelance interpreter and international development consultant.

My introduction to the Kurdish Deaf community came through Hawal Abdullah, who grew up in Kurdistan without access to a shared sign language or education for 18 years. He came to the U.S. in 2016. Since being introduced by a friend in 2017, he and I have navigated the systems of education, healthcare, Vocational Rehabilitation, immigration, and more. In 2021, I contacted the Kurdistan Deaf Association –Duhok via Facebook to explore the possibility of six colleagues and me visiting and learning from them.

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq’s population is 6.5 million (Kurdistan Region Statistics Office, 2023). Its Deaf population could be as large as 325,000 if using the World Health Organization’s (2023) estimate of 5% of the world’s population having hearing loss or deafness,

10

Image credit: AUK Communications

but there has been no census to confirm this. Marked by celebrations like Newroz (Kurdish New Year) and Kurdistan Flag Day, Kurdish people are known for gathering to enjoy picnics on mountainsides with friends and family, drinking tea, sharing stories, and cherishing their diversity, languages, and culture.

While Deaf Kurds also celebrate these same traditions as their hearing peers, they do not have the right to drive (Rûdaw, 2022), are only educated until grade nine (or never attend formal education) in several cities (Jaza, 2016, p. 571), sit in classrooms under teachers who have not been trained to sign (IOM, 2022, p. 11), have limited pathways to pursue higher education (IOM, 2022, p. 17), and only have legal rights to an interpreter in the courtroom (IOM, 2002, p. 6; Amnesty International, 2009, p. 48). What is the first step toward advancing systemic change toward equality? When my colleagues and I asked this question to 70 Deaf leaders across Kurdistan at a March 2022 conference we hosted, the resounding answer was a need for qualified Kurdish Sign Language (KuSL) interpreters. The need is so great, that one Deaf woman shared she was thankful to now have a hearing daughter so her son would no longer have to interpret her OBGYN appointments.

At the time, I was a first-year International Development M.A. (IDMA) student at Gallaudet University. The trip team included two Deaf

Americans (a software developer and early childhood education specialist) and five hearing Americans, three of whom were also interpreters. I am hearing, and two of the other hearing members included fellow IDMA students Samantha (Hoeksema) Wulz and Elias Henriksen. In the IDMA program, we learned the importance of collaborating with local Deaf communities to advocate for the issues they care about most. We also learned about countries where well-intended people had gone to teach American Sign Language (ASL) without researching or preserving the local sign language. We committed to avoid that mistake in Kurdistan.

Concepting and Funding

Over the next 15 months, we listened to, researched, documented, and strategized alongside Deaf Kurdish leaders via Zoom as they articulated their priorities. We translated their vision into a concept note and a house graphic. For them, the lynchpin to removing barriers was having qualified interpreters to provide communication access during meetings with government leaders and policymakers.

An internship with the Kurdistan Regional Government Representation in the United States (KRG-USA) connected me to the International Research & Exchanges Board (IREX). After presenting the concept note to IREX via KRGUSA with proposed solutions, budgets, and timelines to address various barriers, my col-

11

Click image to enlarge

leagues and I received a one-time small grant to develop the first KuSL interpreter training pilot course in Kurdistan. The project was supported by the U.S. Embassy, Baghdad, under the U.S. Iraq Higher Education Partnerships Program.

Building the Team

The project team included four IREX employees (Dr. Lori Mason, Anmar Albabaka, Thomas Fenton, and Benjamin Hobbs) for grant administration and program guidance; three Kurdish Deaf consultants (Ahmed Ali, Rizgar Ismail, and Karzan Rasheed) to guide the partner institution selection process, learning objectives, and KuSL instruction; two project managers/course co-instructors (Elias Henriksen and me); and two faculty consultants (Sammie Sheppard and Rebekah Covington) from Tarrant County College (TCC). Another critical team member was our spoken Badini Kurdish/English course interpreter, Aram Harbi Saadallah, who also translated all our materials and written student communication.

As a team and using screening criteria on applicant institutions, we selected The American University of Kurdistan (AUK) to host the “Introduction to Educational Interpreting” in KuSL course under its Center for Academic and Professional Advancement (CAPA). We joined status meetings with the IREX team to plan program logistics and facilitated weekly curricu-

As a final component of the project setup, we recruited a Kurdish community advisory board of representatives from three Kurdistan Regional Government ministries (Higher Education and Scientific Research, Education, Labor and Social Affairs), the Prime Minister’s office, two universities, two non-governmental organizations (NGOs), one Deaf school, a hearing parent of a Deaf student, and the president of the Kurdistan Deaf Association – Duhok. The board convened monthly to discuss course progress and larger Deaf community advocacy goals.

12

lum discussions via Zoom with the Kurdish Deaf consultant team and TCC.

Designing the Curriculum and Student Selection Process

Due to funding and time constraints, we had the challenge of creating an eight-week course to cover interpreter fundamentals. To appropriately set expectations, we shared that U.S. interpreter preparation standards typically require a four-year degree, participation in an interpreter training program, and passing a certification exam. We understood eight weeks of training would not yield fully qualified interpreters; however, we knew it would be an essential first step and pilot opportunity to raise awareness about the critical need for KuSL interpreters.

The Kurdish Deaf consultants shared their hopes and desires for the course, which TCC translated into a draft syllabus. Together, we worked through each week of the syllabus to brainstorm culturally appropriate lessons, activities, projects, and assignments. We chronicled Kurdish Deaf history, role models, cultural norms, and fingerspelling.

We used Google Docs and Slides to build the curriculum, Flip for student video submissions, and EdPuzzle for receptive fingerspelling practice. We added images to virtually every curriculum slide to combat barriers from literacy limitations, and spent hours via video calls reviewing each prospective vocabulary word with the Kurdish Deaf instructors. This exercise was essential to confirm understanding and if a corresponding KuSL sign was available, while expanding our creativity and visual thinking. We filmed KuSL vocabulary YouTube videos

because a Deaf-led KuSL dictionary resource does not exist.

We recruited prospective students via social media and AUK’s website to submit an essay and video in KuSL. We assumed the student applicant pool would be family and friends of Deaf individuals with strong KuSL experience; however, due to a lack of available KuSL education resources, most of the students who applied were beginner signers, and only two had Deaf relatives. Some prospective SODA and CODA applicants we connected with through the local Deaf community cited transportation, lack of a class stipend, work, and family commitments as barriers to applying for and joining the course (Anonymous, personal communication, [September 17-26, 2023]). Thirty-one students applied, 26 were accepted, and 19 attended and completed the course; 10 were local hearing teachers of Deaf (ToDs) students. The ToDs shared that no tailored Deaf education training exists in Kurdistan, and they have had to primarily rely on outdated printed KuSL dictionaries for instruction. The five applicants who were not accepted had no sign language background and did not respond to requests to resubmit their applications with KuSL resources; the seven applicants who did not attend the course even after being accepted, cited transportation and schedule conflicts as barriers to joining the course.

Teaching the Course

The course met for 32 three-hour sessions across eight weeks. For most of the instruction

13

Image from a video courtesy of Tarrant County College

time, Ahmed Ali and Rizgar Ismail (Kurdish Deaf lecturers) were in the front of the class to focus on KuSL language modeling with support from hearing lecturers on higher education principles and classroom management. The course had to pivot from focusing on interpreter fundamentals to prioritizing KuSL fundamentals, layered with interpreting ethics, theory, and practice. During the first two weeks of the course, hearing students attempted to correct the Deaf instructors’ signs, which we quickly addressed: KuSL is the Deaf community’s language. Therefore, we will respect it and the Deaf instructors teaching it. We will not invent signs as hearing people. We witnessed mindsets in the 19 students shift from a limited view of the Deaf community’s potential and autonomy to an expansive view and appreciation of the Deaf community and its KuSL expertise.

For lectures, Ahmed/Rizgar signed in KuSL, Elias/I interpreted into English, and Aram interpreted into Badini Kurdish. Although we prioritized voice-off times in class to enhance the students’ KuSL expressive and receptive skills, having a spoken language interpreter in class benefited the more technical aspects of our lectures, such as interpreting ethics and theory. We dedicated several sessions to brainstorming a potential KuSL interpreter code of ethics, as

Images credit: AUK Communications

Kurdistan does not have an interpreter governing body or certification process.

Outside of class, Elias and I spent time with the Kurdish Deaf community to learn as much KuSL as possible. For three weeks in the middle of the course, Elias and I co-taught remotely from the U.S. due to a security protocol concern, while our Kurdish Deaf colleagues and spoken Badini Kurdish/English interpreter continued in person with the students. We received approval to return for the final week and completion ceremony.

Course Takeaways

Students completed evaluations at the midpoint and end of the course. They loved the activities (e.g., KuSL “telephone,” Pictionary, speed challenges, and Rory’s Story Cubes), KuSL vocabulary instruction, and the Kurdish Deaf role model interview assignment. Improvement requests included a desire for additional courses, splitting KuSL and interpreting into separate semesters, a KuSL video dictionary app, and including KuSL grammar fundamentals. As course instructors, we completed a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) diagram to reflect on the course process critically and enhance future offerings.

14

The course fostered additional benefits, like the opportunity for Kurdish Deaf women artisans to showcase their work at AUK; facilitating three outreach events for the Kurdistan Deaf Association – Duhok; hosting seven Deaf guest presenters; and bringing Deaf leaders to meet with 15 organizations and government representatives about the Kurdish Deaf community’s future economic, educational, and civic opportunities. In addition, discussions are underway to explore the possibility of Deaf-led KuSL courses at Kurdistan universities. The importance of collaboration with local Deaf communities cannot be understated and requires patience. Pulse-checking and maintaining open lines of communication with a posture of humility throughout the process was vital to maintaining mutual understanding and priority alignment.

Although this interpreter training course provided a basic framework of KuSL and the sign language interpreting profession, it was only the first step in creating a robust two-year university-level training program. We acknowledge this course alone is insufficient to combat the history of social stigma and limited resources the Kurdish Deaf community has confronted.

Through this pilot course, our colleagues intro-

Additional Reading and Resources

duced KuSL as a living, diverse, and respected language to a class of hearing students. We spotlighted Deaf Kurdish leaders in public events, high-level government meetings, and social media. This course was the first time a Deaf Kurdish person had instructed at a university level in the region. With the momentum built and the public eye placed upon the Deaf Kurdish social movement, future Deaf human rights advocacy in the region remains possible.

Food for Thought

If you want to learn how to apply your sign language interpreting skills to international contexts through collaborative projects, I highly recommend the Gallaudet University IDMA program. It gave us a critical foundation and lens to envision this project and invite stakeholders to support it. Please contact idma@gallaudet. edu for more information. Or, if supporting future interpreter training endeavors in Kurdistan is something you would like to explore, please reach out to me at emma_decaro@me.com We will continue to seek grant opportunities for expanded interpreter and educator training in Kurdistan and are always looking to build the team.

Introduction to Educational Interpreting in KuSL Class. (2023). Draft of Proposed KuSL Interpreter Code of Ethics. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1lzmGskMF6oN-fl_nvPefqJLelSNhAHWwL5GRliOT0hc/edit?usp=s haring

KuSL Vocabulary Videos. (2023). Home [@HannahDeafLove]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/@HannahDe afLove-rf1nb

World Federation of the Deaf (WFD). (2022). Declaration on the Rights of Deaf Children. https://wfdeaf.org/rights deafchildren/

References

Amnesty International. (2009). Hope and Fear: Human Rights in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. https://www.re fworld.org/pdfid/49e6e8922.pdf

International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2022). Deaf People in Iraq, A Cultural-Linguistic Minority: Their Rights and Vision for Inclusion. https://mena.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl686/files/documents/Deaf%20peo ple%20in%20Iraq%2C%20a%20cultural-linguistic%20minority%20their%20rights%20and%20vision%20 for%20inclusion%20report.%20%28Updated%29%5B2%5D.pdf

Jaza, Z. (2016). 23 Kurdish Sign Language. In De Gruyter Mouton, Sign Languages of the World (pp. 567-582). https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781614518174-029/html

Kurdistan Region Statistics Office. (2023). Population. https://krso.gov.krd/en/indicator/population-and-laborforce/population

Rûdaw. (2022). Deaf People Call on the Government to Grant them Driving Licences. https://www.rudaw.net/ english/kurdistan/24092022

World Health Organization. (2023). Deafness and Hearing Loss. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/de tail/deafness-and-hearing-loss

15

DECISION-MAKING

WHILE INTERPRETING IN SOCIAL SETTINGS

This article was originally published on Myers & Lawyer website (www.myersandlawyer.com) in 2024.

ASL video by Angela Vilavong (AV), DI

Kenton Myers, NIC, QMHI, ABICE, CHI™, CMI-Spanish, CoreCHI-P™, AL Court Certified, BEI Advanced, Trilingual Advanced

Kenton Myers is a trilingual (ASL/Spanish/English) interpreter based out of Birmingham, Alabama. He is well known across the South for his leadership in the advancement of the field of interpretation and translation. He currently serves as president of the Interpreters and Translators Association of Alabama (ITAA), a diverse group comprised of professionals working in over 12 languages, to promote community education and support ongoing education for interpreters and translators. Kenton is also 1/2 of Myers & Lawyer, a Black multilingual researcher/interpreter duo that engages in research, consultation, training, and resource development for BIPOC interpreters. Beyond his linguistic pursuits, Kenton embodies holistic wellness as a Licensed Massage Therapist, Hispanic Outreach Wellness Instructor, and an avid CrossFit enthusiast.

Tiffany T. Hill, CI & CT, NIC-Advanced

Tiffany Hill is a Washington, DC/DMV native, born in the District and raised in the Metropolitan area where she is the founder of First Choice Interpreting Service, LLC. She is a trilingual (Spanish) interpreter and interpreter mentor. She is a community bred interpreter receiving her RID CI and CT in 2004 and her NIC-Advanced in 2009. She is a self-proclaimed couch scholar with a passion for expanding our human capital through dialogue and meta analysis, with a strong emphasis on improving and enhancing the field for Black, Indigenous and Interpreters of Color. When she is not running races and lifting weights, she is traveling the world and reading books. Usually at the same time.

16

PLEASE DON’T KILL MY VIBE

Our work as interpreters comes embedded with layers of demands. We tend to look at the work of an interpreter through a myopic lens of hard skills. This can often become a challenge when our work goes from daytime to evening, formal to intimate, and/or concrete to abstract. When this occurs in social interpreting environments, we have to embody and employ more than just our language skills. An interpreter who takes on the dynamic, yet nuanced role of interpreting in social spaces has to think beyond linear linguistic transactions and toward the utilization and practice of interpersonal skills, aka soft skills. Networking, socializing, and building collegial rapport often takes place after office

hours. Interpreters should have a working understanding of how this applies to the business culture in which we find ourselves while using discernment and observation in order to traverse the arena successfully. This conversation starter will address considerations for our decision-making, the impact it can have on the Deaf professional and their image, as well as the precedents our actions might establish, shaping the course of future interactions.

17

No two social settings are exactly the same, rendering the creation of a one-size-fits-all list of do’s and don’ts futile. Nevertheless, amidst this variability, there are standards, strategies, and guidelines we can apply to help us preemptively think before accepting jobs intertwined with social interactions. If not an innate skill, it can be a very complex and unpredictable terrain to negotiate for many interpreters. Therefore, if and/or when we are spontaneously sprung into these situations, it’s good to have a

running repertoire of thoughtful consideration to reference.

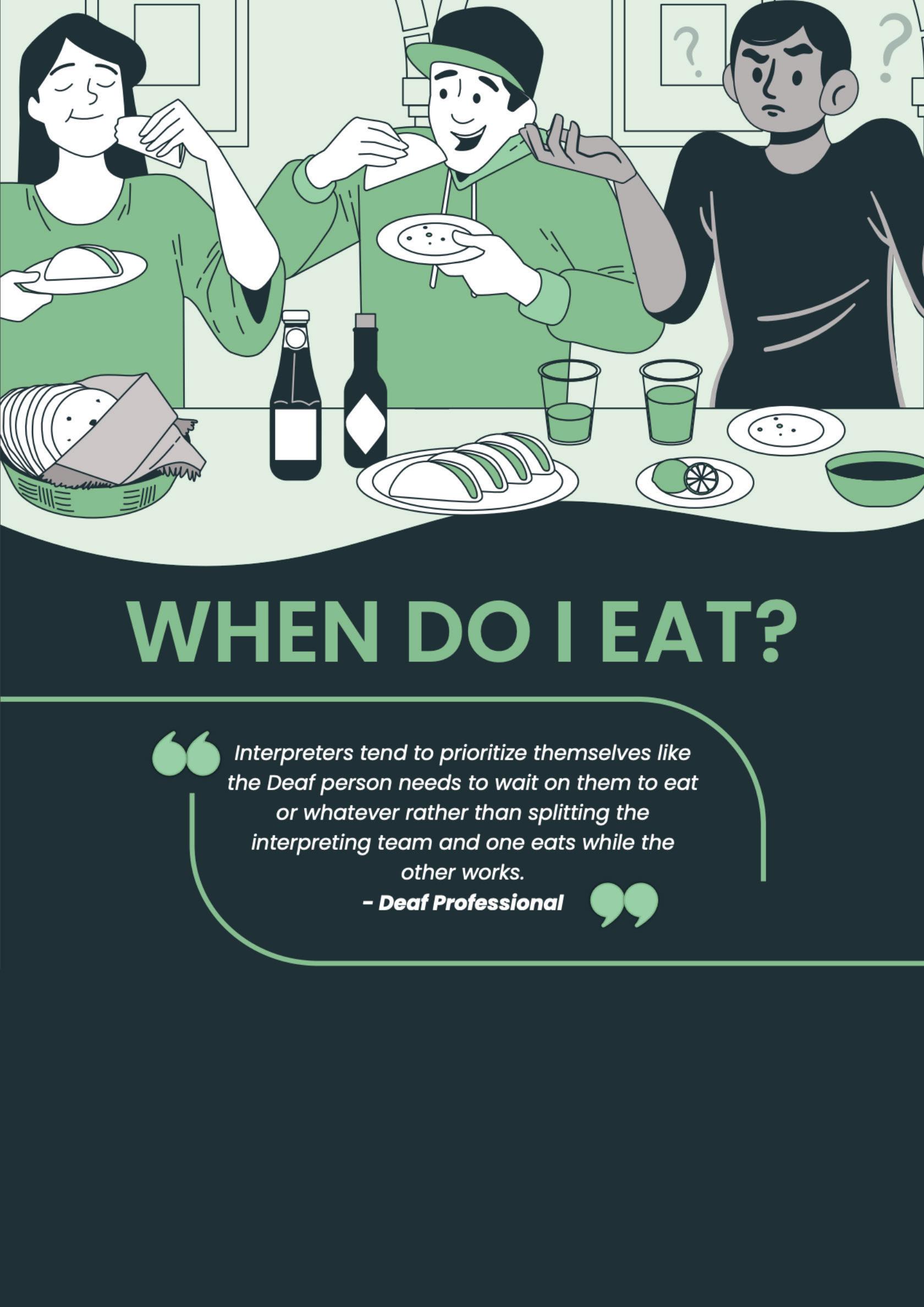

As interpreters assigned to all-day events, the prospect of a “working lunch” often fills us with apprehension. Frequently, such decisions are made on the spot during the course of an event and can disrupt the pre-established break schedule for the interpreting team. Even in the absence of an agreed-upon working lunch (i.e. “lunch on your own”), interpreters are constantly

18

maneuvering around the uncertainty of whether a Deaf professional might choose to utilize scheduled breaks for networking or interacting with peers, unburdened from the distractions of a crowded environment. This necessitates ongoing consideration, flexibility, and careful plan-

Tips to avoid hunger:

ning amongst the interpreting team. Our soft skills become crucial in this moment of on-thefly coordination and teamwork with the overarching objective of tending to our physiological needs while ensuring a smooth uninterrupted facilitation of access for the Deaf professional.

• Inquire about meal logistics prior to the event

• Eat a little before the engagement

• If food is offered to everyone, get there early and partake so you aren’t starving

• Keep discreet snacks in your bag for sustained energy

• Implement a turn-taking system to ensure everyone has the chance to eat.

WE DRINKIN’ OR NAH?

As if operating in social engagements isn’t challenging enough, it always gets trickier when there’s an open bar. There are a number of factors to consider when deciding whether or not to partake in social drinking while working. Whether the offer is extended or not, it’s crucial to acknowledge that, given the cognitive demands of our work and the associated physical and mental challenges—such as navigating prolonged social interactions in noisy environments, managing drinks while conversing, and the balancing act between work and play—interpreters may choose to decline alcoholic beverages. This decision aims to uphold the precision of conveyed messages and conserve energy, a choice that may not always be entirely appreciated despite possible encouragement. In these instances, preparing a running script to wield on command in defending your choice to partake or not is always a good idea. It also serves to provide notice to attendees that while

Interpreters that don’t drink at social events are stuffy to me.

- Deaf Professional

no two interpreters are the same, our intentions are: to provide equitable and effective access.

Factors for reflection:

• How might my decision to partake be perceived, considering not only the perspective of the Deaf consumer(s) but also that of the hiring entity?

• Will drinking impair my judgment, production, or quality of interpretation?

• Does alcohol tend to have physiological impacts on me (sleepiness, shorter stamina, etc.)

• How will my decision impact my team?

19

OH YOU FANCY, HUH?

Our need to show up as our authentic selves should never outweigh or overshadow the needs of the Deaf professional to whom we are providing access. When choosing how to present, it’s always important to read the job notes thoroughly, and assess the nature of the event, location, and participants. While there is no universal rule, our decisions should not be driven solely by personal preferences. Instead, they should align with what is most appropriate and acceptable for each work environment. If ever we are in doubt, we should ask.

Factors for fashion:

• What kind of event is it?

• Have I read the job notes thoroughly?

• Do I know the expected dress code of all attendees?

• If I don’t match the dress code will this negatively impact the Deaf professional?

I view the interpreter as an extension of myself. So, if they look, dress, or behave unprofessionally, I take it as a reflection of how people might view me.

-Deaf Professional

20

YO! YOU BLOCKING

I get wanting to be ‘human,’ make connections, be friendly, but let’s face it, when that happens, Deaf people are the ones getting the short end of the stick.

-Deaf Professional

We never want to be the reason a Deaf person is reticent or uncomfortable interacting with their Hearing colleagues and counterparts. However, this could present a challenge for us when our day job moves beyond the didactic space and into a more social one especially if we are unfamiliar working with the participating clients and consumers. An interpreter’s interpersonal awareness, or lack thereof, will undoubtedly have an impact on a Deaf professional’s ability to network, mingle, and engage effortlessly. The use of soft skills can be the make or break of a successful social interaction. If we are seemingly unapproachable, or conversely, overly familiar with no sense of boundaries, this could present a deterrent or send a message to would-be-chatters that we are closed for business and discourage attempts to approach the Deaf professional. How we show up and navigate these spaces could ultimately lead to undesired outcomes if not handled appropriately or with the right amount of finesse.

Factors for consideration:

• What is my body language communicating?

• Am I actively present or do I seem disinterested?

• Am I doing the most/taking up too much space?

• Am I having a lot of incidental conversations independent of the Deaf Professional?

The call to action is clear: As interpreters, we must embrace a broader perspective, acknowledging the multifaceted nature of our role and function in professional and social spaces. Let’s learn how to integrate soft skills seamlessly into our repertoire, recognizing that our decisions are not just personal choices, but rather crucial components of fostering inclusive, equitable, and effective access for Deaf professionals. It’s time to enrich our practice, wholly aware of the impact we can have beyond the bounds of language, and in the realm of social interactions, where networking and professional opportunities unfold. Our hope, with this conversation starter, is to prompt self-reflection when considering accepting jobs of the social nature and/or if our job unwittingly shifts in that direction. May we all look to improve the framing of equitable access by ongoing and intentional decision making.

21

The Black ASL Project: An Overview

Dr. Carolyn McCaskill, Gallaudet University

A graduate of the Alabama School for the Deaf, 1972, Gallaudet in 1977, BA; 1979, MA & 2005, PH.D. She is the Founding Director of the newly Center for Black Deaf Studies at Gallaudet. She is also a Professor in the Deaf Studies Department. Carolyn is the co-author of groundbreaking research and book, The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure, published in 2011 (with Ceil Lucas, Robert Bayley, and Joseph Hill). She is also an associate producer on the documentary Signing Black in America, with Joseph Hill and Ceil Lucas, produced by the Language & Life Project, North Carolina State University, 2020.

Dr. Ceil Lucas, Gallaudet University

Ceil Lucas is Professor Emerita of Linguistics at Gallaudet University and editor of the journal Sign Language Studies. She has conducted extensive sociolinguistic research on American Sign Language (ASL) as well as research on African American English. Her books include Sociolinguistic Variation in American Sign Language (with Robert Bayley and Clayton Valli), The Linguistics of American Sign Language, 5th edition (with Clayton Valli, Kristen Mulrooney, and Miako Villanueva), and The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure (with Carolyn McCaskill, Robert Bayley, and Joseph Hill). She is an associate producer for the documentary Signing Black in America, with Carolyn McCaskill and Joseph Hill, produced by the Language & Life Project at the North Carolina State University, 2020.

Dr. Joseph C. Hill, National Technical Institute for the Deaf, Rochester Institute of Technology

Dr. Joseph C. Hill is an Associate Professor in the Department of ASL and Interpreting Education, Associate Director of the Center on Culture and Language, and Assistant Dean for Faculty Recruitment and Retention at Rochester Institute of Technology’s National Technical Institutes for the Deaf. His research interests are the socio-historical and -linguistic aspects of Black American Sign Language and the American Deaf community’s attitudes and ideologies about existing signing varieties. His contributions include The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure (2011) which he co-authored with Carolyn McCaskill, Ceil Lucas, and Robert Bayley and Language Attitudes in the American Deaf Community (2012). He is also one of the associate producers for the documentary, Signing Black in America, with Carolyn McCaskill and Ceil Lucas, produced by the Language & Life Project at the North Carolina State University, 2020. Link: www.josephchill.com

Dr. Robert Bayley, University of California, Davis

Robert Bayley is Professor Emeritus of Linguistics at UC Davis and an associate member of the Centre for Research on Language Contact at York University in Toronto. His research focuses on language variation and language socialization, especially in bilingual and second language populations. Professor Bayley is the author of more than 150 publications, including 16 co- authored and co-edited volumes and articles in major journals such as American Speech, Asia- Pacific Language Variation, Language, Language Variation and Change, and Studies in Second Language Acquisition. Currently he is conducting research on the acquisition of sociolinguistic competence by second language learners and, with Kristen Kennedy Terry, working on a book on social network analysis for second language acquisition research.

22

On February 1, 2024, the Black ASL team gave a presentation via Zoom for the membership of the Registry of Interpreters of the Deaf (RID), coordinated by Kayla Marshall. What follows is a summary of the project’s findings1

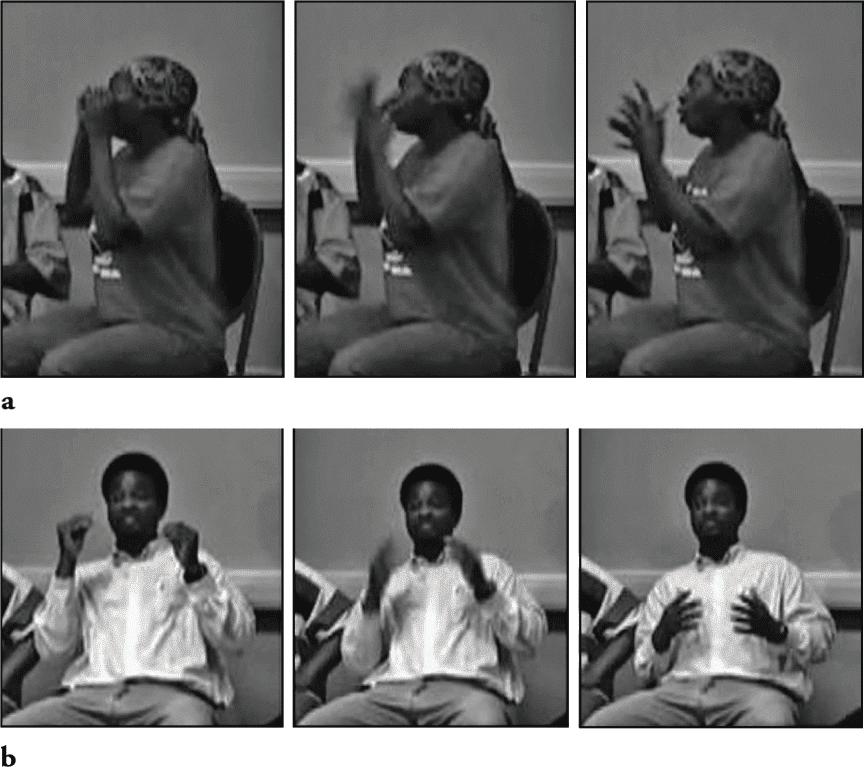

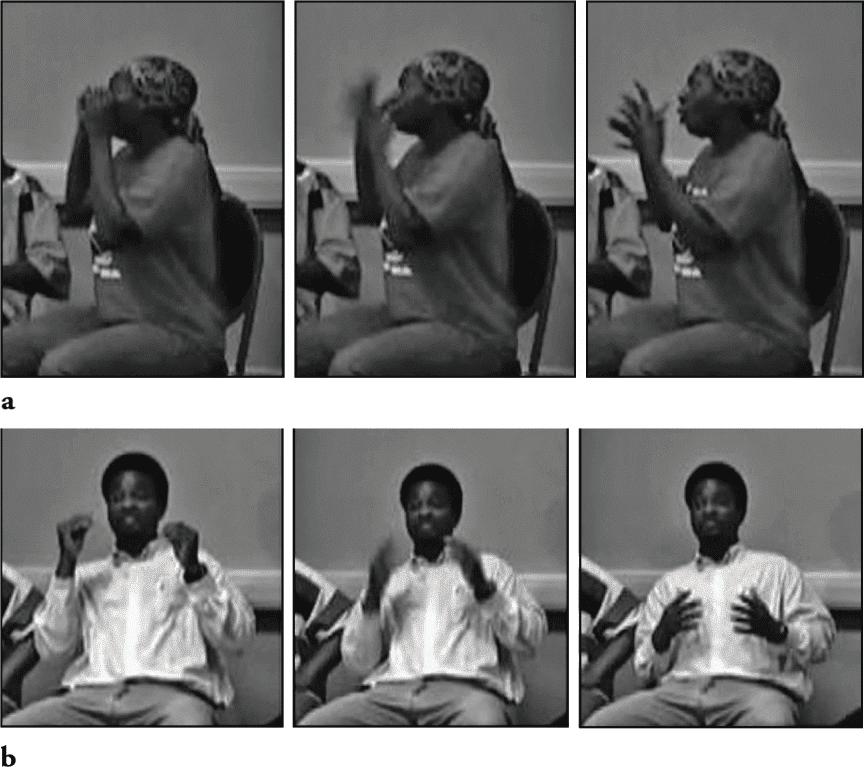

The first large-scale systematic study of Black ASL reported that, at least with respect to some of the variables analyzed, Black signers were more likely to produce signs in citation form (+cf), the standard form found in ASL dictionaries and taught in ASL classes, than their white counterparts were (McCaskill et al. 2011/2020). Moreover, the older Black signers, those who were fifty-five or older in the first decade of the twenty-first century and had attended segregated schools, were more likely to produce +cf variants than their younger Black counterparts who had attended integrated schools. For example, Black signers are more likely to produce signs like KNOW or TEACHER 2 in their citation form on the forehead, while white signers are more likely to produce them somewhat lower (Lucas et al. 2001, McCaskill et al. 2020 [2011]). Similarly, Black signers are more likely than their white counterparts to use the two-handed variant of signs, the traditional +cf form. Examples include the signs WANT, DON’T-KNOW, TIRED, and TEACHER. Figures

1a and 1b and 2a and 2b illustrate the +cf (forehead) and –cf (lowered) versions of the sign TEACHER and the +cf (two-handed) and –cf (one-handed) forms of the sign DON’T-KNOW.

Figure 1

(a) TEACHER in citation form.

(b) TEACHER in lowered (non-citation) form.

Figure 2

(a) DON’T KNOW in two-handed (citation) form.

(b) DON’T KNOW in one-handed (non-citation) form.

Figure 3 (click image to enlarge)

Lowered signs by age, and one-handed vs. two-handed signs by age: Results from four studies3 .

Figure 3 summarizes the results of four studies of the lowering of signs produced on the forehead in citation form and two-handed signs that can also be produced as one- handed. In every case, the Southern Black signers produced a smaller percentage of signs in –cf form than their white counterparts did. That is, the difference between Black and white ASL varieties is quantitative, rather than qualitative.

In addition to producing more +cf signs, including those produced at a lower level and more two-handed signs, the Black signers studied in McCaskill et al. (2011/2022) used

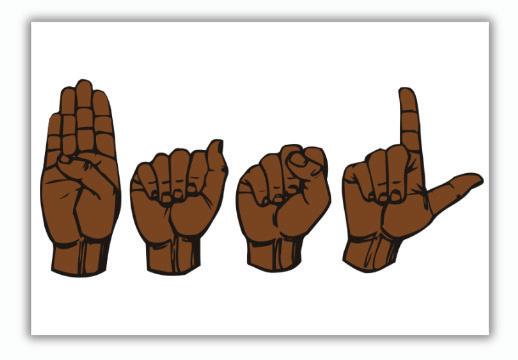

23

markedly less mouthing of English words and phrases than their white counterparts did, as well as a larger signing space, and they had a tendency to repeat the same sign within a sentence. McCaskill et al. also report on a number of lexical differences. Finally, Black ASL exhibits many borrowings, both lexical items and phrases, from African American English (AAE), two of which, the signs MY BAD and TRIPPIN’, are shown in Figures 4 and 5. These features add up to a distinct variety of ASL.

(a). TRIPPIN’, forehead with movement out.

(b). TRIPPIN’, forehead, short, repeated movement, no movement out.

The project has shown that a distinct variety of American Sign Language, known as Black ASL, developed in the segregated schools for deaf African Americans in the US South during the pre-civil rights era. The project found:

• very clear evidence of deaf teachers, both Black and White, in many of the Black schools/departments, that is, fluent signers who provided solid models of ASL. These models combine with the lack of oralism to account for the more traditional and standard usage in Black ASL, including the lack of mouthing of English;

• strong evidence that the Black and white students did not interact with each other, even if their schools were located close to each other;

• strong evidence of the fierce racist resistance to integration, to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, and to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and, in all cases, integration required intervention from the federal or state governments. No state voluntarily desegregated before 1954, and only four did so shortly after the Brown v. Board decision;

• that Black deaf people are of course fullfledged members of the American Black community and are thus in contact with African American English (AAE). As our research shows, one feature of Black ASL is the incorporation of AAE lexical items and phrases.

The project findings can be found in McCaskill et al. (2011/2020); the project is also discussed in the documentary Signing Black in America, produced by the Language and Life Project at North Carolina State University (2020), available for free on YouTube.

Some specific questions for discussion arise from this summary and from the February 1 presentation, questions which may be useful in interpreter training settings:

1. Have you ever interpreted (a play, personal conversation, comedy show, VRI, church etc.) for a Black client where standard English and African American English were used? How does code-switching impact the interpreting process?

2. Have you ever interpreted (a play, personal

24

Figure 4 MY BAD

Figure 5

conversation, comedy show, VRI, church etc.) for a Black Deaf client where ASL and BASL were used? How does code-switching impact the interpreting process?

3. When is it appropriate for an interpreter to voice African American English or sign BASL? Should the race of the interpreter be considered? Why or why not?

4. How does interpreting in Black ethnic/cultural environments during interpreting education programs or professional development courses impact an interpreter’s preparation?

Notes

1 Portions of this article have been adapted, with permission, from Lucas, C., R. Bayley, J. C. Hill, & C. McCaskill. (2022). The segregation and desegregation of the Southern schools for the deaf: The relationship between language policy and dialect development. Language 98.4: e173198. Figures 1–5 appear with permission of Gallaudet University Press. They appear in McCaskill, C., C. Lucas, R. Bayley, and J. Hill (2011/2020), The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure

2 We use small caps for ASL signs, including those for words and phrases originating in African American English. For example, TEACHER refers to the ASL sign, not to the English word.

3 Data for lowered signs for northern Black ASL and white ASL are from Lucas et al. 2001. Data for one- handed vs. two-handed signs for northern Black ASL and white ASL are from Lucas et al. 2007. Data from white signers were collected in California, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Virginia, and Washington State. Data from no southern African Americans were collected in California, Massachusetts, and Missouri. Data for Louisiana ASL are from Bayley & Lucas 2015. Data for southern Black ASL are from McCaskill et al. (2011/2020). Older signers in all studies are fifty-five or older. Younger signers in McCaskill et al. were younger than thirty-five, and in Lucas et al. 2001, Lucas et al. 2007 younger signers were younger than fifty-five.

References

Bayley, R., and C. Lucas. (2015). Phonological variation in Louisiana ASL: An exploratory study. New perspectives on language variety in the South: Historical and contemporary perspectives, ed. by Michael Picone and Catherine E. Davis, 565–80. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Language and Life Project, North Carolina State University. Signing Black in America. Video documentary. W. Wolfram, executive producer; D. Cullinan and N. Hutcheson, video producers. Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oiLltM1tJ9M&t=6s&ab_ channel=TheLanguage%26LifeProject.

Lucas, C., A. Goeke, R. Briesacher, and R. Bayley. (2007). Phonological variation in American Sign Language: 2 hands or 1? Paper presented at New Ways of Analyzing Variation (NWAV) 36, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Lucas, C. R. Bayley, J. C. Hill, and C. Mc Caskill. (2022). The segregation and desegregation of the Southern schools for the deaf: The relationship between language policy and dialect Development. Language 98.4: e173-198.

Lucas, C., R. Bayley, and C. Valli (2001). Sociolinguistic Variation in American Sign Language. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

McCaskill, C., C. Lucas, R. Bayley, and J. Hill (2011/2020). The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL: Its History and Structure. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. (The 2020 publication is an updated paperback version of the 2011 one, produced to accompany the Signing Black in America documentary.)

25

HQ

From the desks of RID Headquarters

26

Who we are

MISSION

RID is the national certifying body of sign language interpreters and is a professional organization that fosters the growth of the profession and the professional growth of interpreting.

VISION

We envision qualified interpreters as partners in universal communication access and forward-thinking, effective communication solutions while honoring intersectional diverse spaces.

VALUES

The values statement encompasses what values are at the “heart” or center of our work. RID values:

- The intersectionality and diversity of the communities we serve.

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility and Belonging (DEIAB).

- The professional contribution of volunteer leadership.

- The adaptability, advancement and relevance of the interpreting profession.

- Ethical practices in the field of sign language interpreting, and embraces the principle of “do no harm.”

- Advocacy for the right to accessible, effective communication.

RID understands the necessity of multicultural awareness and sensitivity. Therefore, as an organization, we are committed to diversity both within the organization and within the profession of sign language interpreting.

Our commitment to diversity reflects and stems from our understanding of present and future needs of both our organization and the profession. We recognize that in order to provide the best service as the national certifying body among signed and spoken language interpreters, we must draw from the widest variety of society with regards to diversity in order to provide support, equality of treatment, and respect among interpreters within the RID organization.

Therefore, RID defines diversity as differences which are appreciated, sought, and

shaped in the form of the following categories: gender identity or expression, racial identity, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, Deaf or hard of hearing status, disability status, age, geographic locale (rural vs. urban), sign language interpreting experience, certification status and level, and language bases (e.g., those who are native to or have acquired ASL and English, those who utilize a signed system, among those using spoken or signed languages) within both the profession of sign language interpreting and the RID organization.

To that end, we strive for diversity in every area of RID and its Headquarters. We know that the differences that exist among people represent a 21st century population and provide for innumerable resources within the sign language interpreting field.

27

Help us expand our CASLI LTA network to provide more access to national interpreter certification testing by becomin g a Local Test Administrator (LTA) or referring someone else.

Test Room

Specifications:

• Private room in a educational/ business setting

• Computer equipment that can effectively run extended video, audio files and recordings

• Google Chrome browser

• Minimum 21 inch monitor

• High speed internet connection

• Webcam and microphone for extended recordings

Local Test Administrator (LTA) Qualifications:

• Certified ASL interpreters OR have no interest in becoming a certified interpreter

• Have no real or perceived conflict of interest

• Are comfortable with and can troubleshoot current technology

• Agree to serve all roles of an LTA including protecting exams, monitoring candidates during exams, and enforce all CASLI requirements to maintain the integrity of the exams

• Willing to accommodate CASLI approved ADA accommodations

28

Find more information: casli.org/about-casli/whoswho-in-casli/local-testadministrators/ Contact CASLI at: Manager@casli.org (571) 257-4761

VIEWS Write for

Calling all authors! Do you have insights, anecdotes, research, or training on topics related to ASL Interpreting? We want to work with you!

VIEWS provides an unparalleled opportunity to reach an audience of 13,000+ members! We strive to deliver content that activates member engagement and starts conversations that drive the profession forward, and we can’t do it without authors like you! Submit your article today!

SUBMISSIONS

The following information is required with your submission:

• English version (800 - 1800 words)

• Author(s) name and credentials

• Author(s) biography (100 - 150 words)

• High resolution headshot of author(s)

Once we receive your submission, the VIEWS Board of Editors will review the article and gather feedback. You will then work directly with the VIEWS Editor in Chief to go through all of the feedback and ask any questions you may have. Once the English version of the article is finalized, send us your ASL version and we will take care of the rest! As an extra perk, published authors will have the opportunity to continue collaboration by working with our team to see if we can turn your topic into a CEC webinar!

2024 TOPICS & SUBMISSION DEADLINES:

15

Have another topic? Share it with us! We accept submissions on any topic relevant to our members on a rolling basis.

29

Submit today!

15 Spring “Ethics” April 15 Summer “Conferences/Community” July Fall “Education” October

ENHANCING THROUGH EDUCATION

About the EATE

Project

Aligning with RID’s mission to foster the growth of the ASL interpreting profession and community, the Enhancing Awareness Through Education (EATE) project will provide educational opportunities that coincide with nationally recognized diversity months. These months include topics such as cultural awareness, heritage months, mental health, and more! CEUs will be offered throughout the calendar year to promote professional development while encouraging broadened awareness within our community.

How Does EATE Work?

Enhanced Webinar Opportunities

This project aims to encourage individuals to participate in EATE events that are intended to raise awareness on topics that go beyond the surface, through CEU opportunities that provide education and professional development across a broad spectrum of lived experiences. By providing a wide range of thoughtful learning opportunities, we hope this program will foster a culture of individual and professional growth year-round.

Webinar Presentations and Proposals

We are seeking content experts to present on these topics throughout the year. In an effort to create as much opportunity as possible, EATE will offer multiple webinars each month. Submission deadlines are strict and set to the 10th of the month before a webinar is scheduled to be presented. Submissions do not guarantee selection; however, they may be considered for a different month should the topic apply. Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Accessibility, and Belonging (DEIAB) are part of the cornerstones of RID, and we want to ensure presenters submit activities that will align with these values. Those interested in having their presentation considered for the EATE project can submit their proposals here: https://rid.org/eate-project-proposals/

430

Learn more here! rid.org/programs/webinars/#eate Questions? No Problem! Email us at webinars@rid.org

AWARENESS EDUCATION

Access

EATE Webinars So Far!

Black ASL: What Does it Mean for Interpretation?

Dr. Carolyn McCaskill, Dr. Joseph Hill, Dr. Ceil Lucas, Dr. Robert Bayley

Purchase this EATE webinar: education.rid.org/products/black-asl-what-does-it-mean-for-interpretation is BASL fo’ real?

Vyron Kinson, CDI

Purchase this EATE webinar: education.rid.org/products/is-basl-fo-real Are

5

you interested in presenting for the EATE Project? Submit your proposal here: rid.org/eate-project-proposals/

31

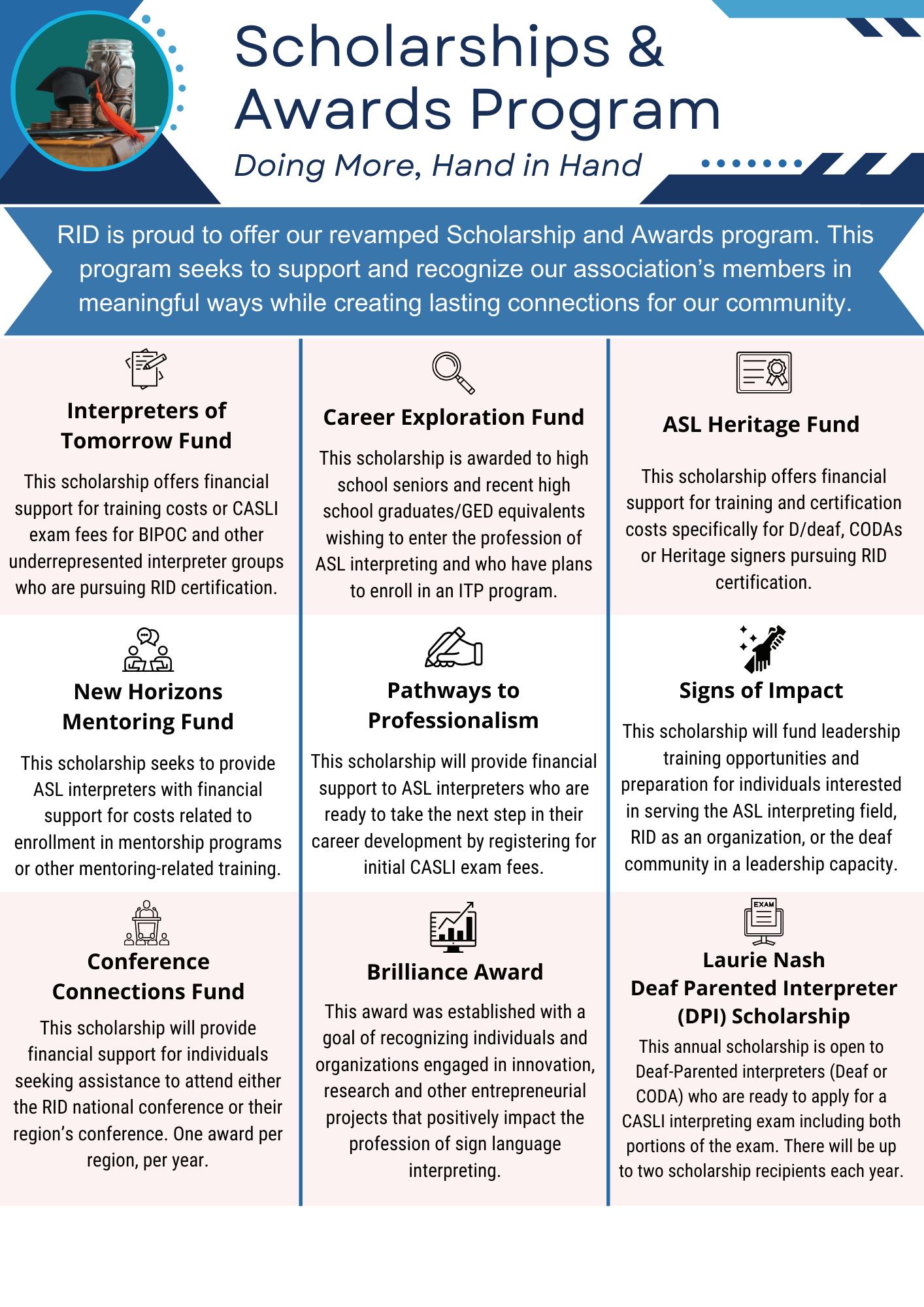

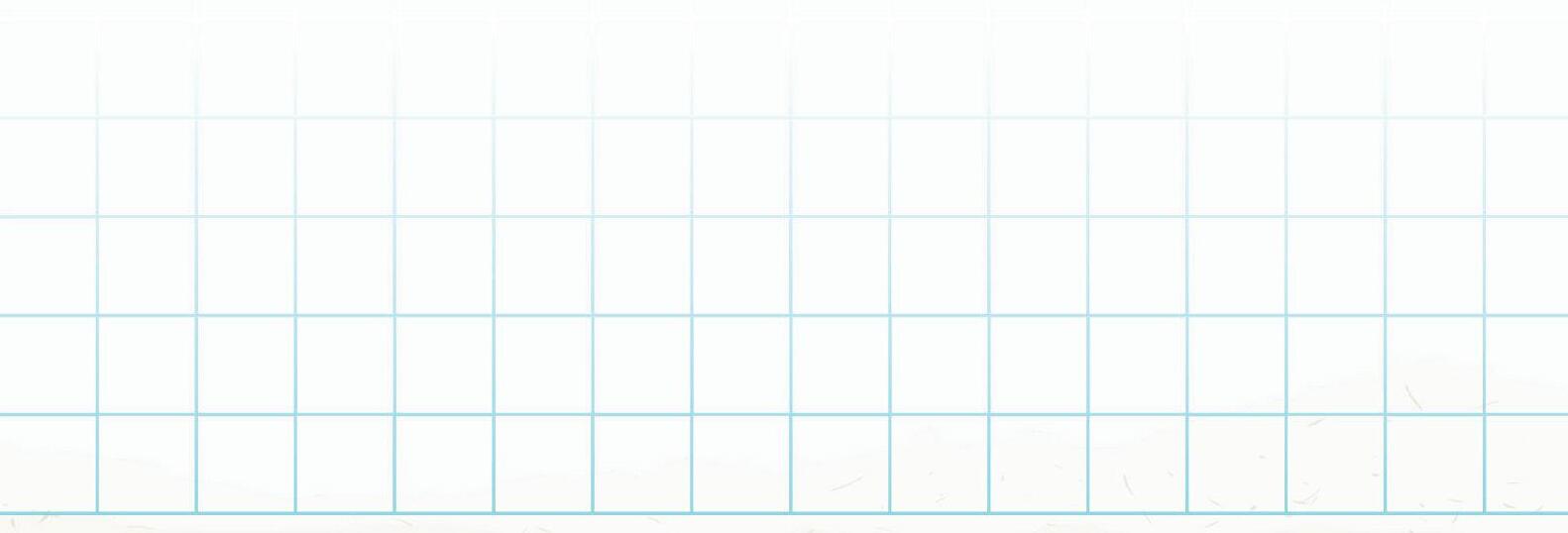

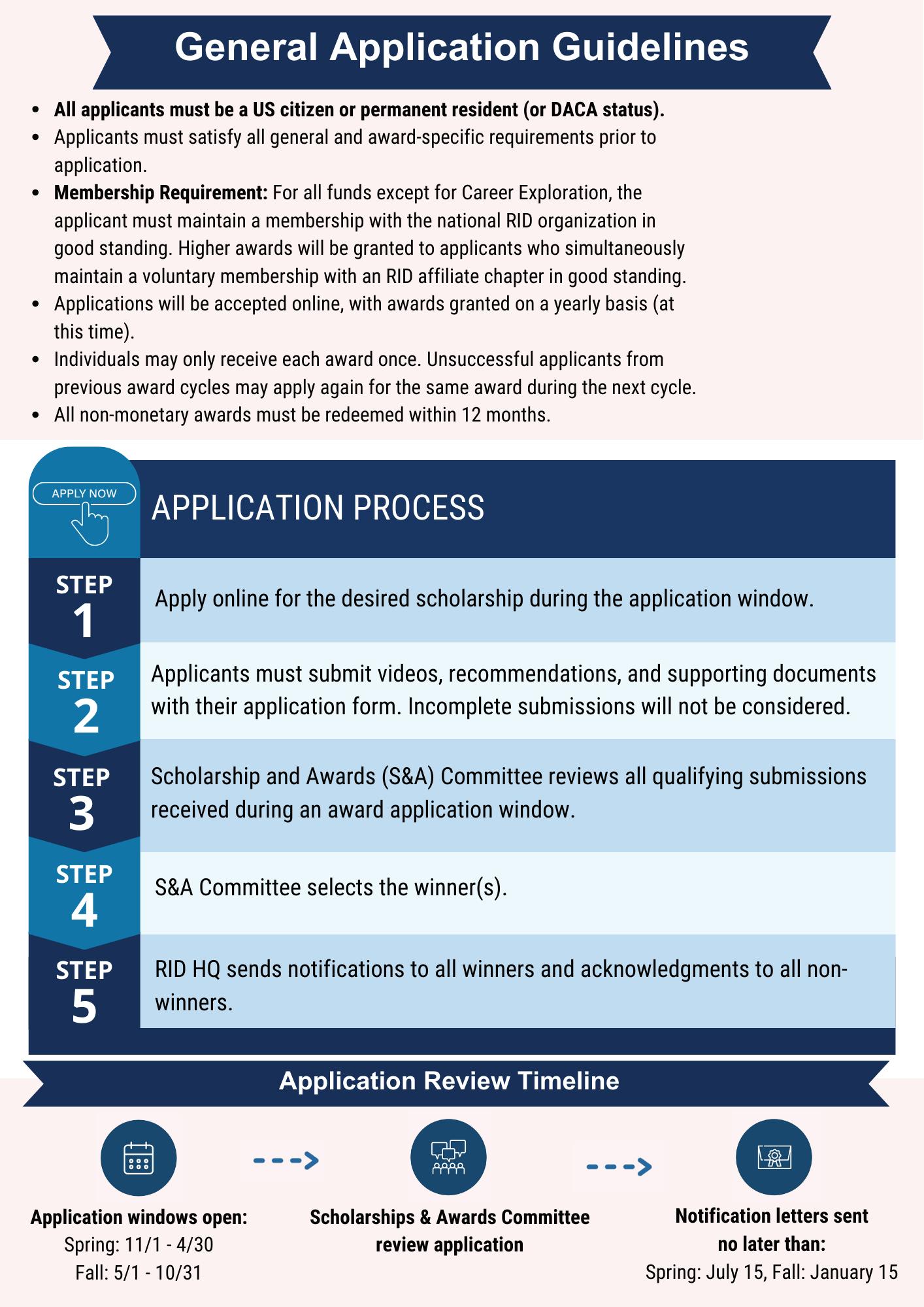

32 Apply today at rid.org/scholarships-and-awards/ Contact us at scholarships@rid.org

33

NEWLY CERTIFIED INTERPRETERS

Kelsey Beers, NIC

Hannah Cameron, NIC

Casey Cutler, NIC

Jillian Elaine Deaton, NIC

Jonella Esposito, NIC

Elizabeth Finnerty, NIC

Sofia German, NIC

Stephanie Guber, NIC

Monique Harris, NIC

Andrew Daniel Holmquist, NIC

Connor Michael Litzenberger, NIC

Natalie Mascarenas, NIC

Sarah Morgenthal, NIC

Izaac Anthony Ochoa, NIC

Jessica Ann Oley, NIC

Victor Manuel Rivera, NIC

Rosalinda M Santana, NIC

Carly Shannon Swinford, NIC

Sean Trainor-Castle, NIC

Shannon Elizabeth Tracy, NIC

Jennifer Lynn Yacono, NIC

Sara Ahn, NIC

Tabitha Renee Arrowood, NIC

Shanna Rachele Balfe, NIC

Marissa Benoit, NIC

Kelly O’Donnell DeMarco, NIC

Jennifer Falls, NIC

Joamia M. Germany, NIC

Rachel Goette, NIC

Sabrina Guida, NIC

Beily Hernandez Gutierrez, NIC

Morgan Ransom Hall, NIC

Taylor Harris, NIC

Joshua Franklin Holmes, NIC

Jaime Jennifer Holloway, NIC

Mara Kay Holtzman, NIC

Sarah Jeanne Howard, NIC

Joanna Hughes, NIC

Hannah Brooke LaTurno, NIC

LaShaundra Lewis, NIC

Wesley Jamal Mills, NIC

Eliany Morejon, NIC

Rocio Cristina Nicholas, NIC

Morgan Wren Pardee, NIC

Scarlett Quick, NIC

Amanda Margaret Reilly, NIC

Isabela Rompf, NIC

ShaCarol Stewart, NIC

Mary Thompson, NIC

Hannah Joy Warran, NIC

Rachel Regan Williams, NIC

Brooke Noelle Carroll, Laura Carpenter, NIC

Shelby Champlin, NIC

Brittni Lynn Duckwall, AnneMarie L. Frankenstein-Orebaugh, Lisa Alexandra Gingery, Elizabeth Marie Godbold, Brittany Jo Haire, NIC

Kyle R Hill, NIC

Cari Noel Huffman, NIC

Kelly Kollar, NIC

Morgan Magnuson, NIC

Mariah Rosemary-Joy

Danielle Martin, NIC

Elle Sandra McCollum, Chadd G Navejar, NIC

Annalise M O’Connell, Veronica Amanda Olvey, Lydia Grace Rogers, NIC

Todd Smith, NIC

Kathryn E Lee Tiemeyer, Sean Walker, NIC

VA NC MD SC TN NC FL FL FL FL SC VA SC MD FL DC MD FL FL NC FL MD FL FL SC MD NC FL NC NC NY NY NJ NJ MA MA MA NY NY NY NY NY NY NY NY NY MA NY NY NY NY

34 INTL

Heisinger-Nixon, NIC

Day

INTERNATIONAL

Jessica Ainsworth, NIC

Susannah Spencer Baen

Russell Bartholomew, NIC

Jody C Clodius, NIC

Frankenstein-Orebaugh, NIC Gingery, NIC Godbold, NIC NIC NIC Mantz, NIC McCollum, NIC NIC O’Connell, NIC Olvey, NIC NIC

Tiemeyer, NIC

Marisa Lyn D’Rose, CDI

Alysha Dyer, NIC

Summer Elizabeth Dykstra, NIC

Kaylee Michelle Fragoso, NIC

Abigail Joy Giambattista, NIC

Alyssa Cristine Harrison, NIC

Jennifer Ann Jackson, NIC

Travone D. Marshall-Pearson

Katherine Murch, CDI

Sarah E. Patterson, NIC

Heather Rahn, NIC

Audrey Anderson Reyna, NIC

Roman E Ross, NIC

Jenna Jerri Barry, NIC

Lynne Elisabeth Buck, NIC

Angeles Camacho, NIC

Sara Katherine Cardinale, NIC

Whitney Noel Christiansen, NIC

Tessa Lynn Clevenger, NIC

Anthony Diaz, NIC

Elizabeth Ashley Grant, NIC

Tracy Grant, NIC

Ryan Haddan, NIC

Elizabeth Haddad, NIC

Heather Ann Harris, NIC

Darryn Rousseau Hollifield, NIC

Allyson Kay Imholz, NIC

Ashley Keller, NIC

Carmelina Kennedy, NIC

Nicole Larson, NIC

Ashlee McHenry , NIC

Breeanne Patrick, NIC

Fetch Phoenix, NIC

Brenna M Povelite, NIC

Dustin Joseph Rael, NIC

Julie Reis, CDI

Sarah Daegling, NIC

Sophia Sexton, NIC

Ingrid Angela Sims, NIC

Stephanie Taylor, NIC

Tanner E. Vance, NIC

CA AZ CA CA WA CA CA AZ AZ OR CA CA CA AZ CA CA AK CA OR CA AK CA OR OR WA CA OR UT TX TX TX CO TX TX NE NM NE NM CO CO TX NM TX TX OK MI OH KY OH OH MI IN MI MN KY OH MN MN WI MN OH WI IN IL OH OH WI

NIC NIC NIC

*List as of March 19, 2024 35

36

Advertise in VIEWS

With over 13,000 members in the U.S. and abroad, RID is the largest, comprehensive registry of American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters in the country! Connect and communicate with your potential and existing clients through our exclusive, digital magazine VIEWS, offering fresh and relevant content every season. Reach your marketing goals by connecting with our VIEWS audience for your company or organization’s events, promotions, job announcements, webinars and more!

Learn more here!

37

Certification Maintenance Program

Here is a link, accessible to the community at large, that lists individuals whose certifications have been revoked due to non-compliance with the Certification Maintenance Program or by reasons stated in the RID PPM.

If an individual appears on the list, it means that consumers working with this interpreter may no longer be protected by the Ethical Practices System should an issue arise. The published list is a “live” list, meaning that it will be updated if a certification is reinstated or revoked.

The Certification Maintenance Program requirements are:

1

Maintain current RID membership by paying annual RID Certified Member dues.

2

Meet the CEU requirements:

• 8.0 Total CEUs with at least 6.0 in PS CEUs

• Up to 2.0 GS CEUs may be applied toward the requirement

• SC:L only

• 2.0 of the 6.0 PS CEUs must be in legal interpreting topics

• SC:PA only

• 2.0 of the 6.0 PS CEUs must be in performing arts topics

Should a member lose certification due to failure to pay membership costs or failure to comply with CEU requirements, that individual may submit a reinstatement request. The reinstatement form and policies are outlined here. The certification reinstatement list can be found here.

3 Adhere to the RID Code of Professional Conduct and EPS Policy.

Voluntary Relinquishment of RID Certification(s)

RID Certified members who decide to voluntarily relinquish the RID certification(s) they currently hold are required to submit a completed, signed and notarized form. To learn more about the eligibility requirements or to submit your request to voluntarily relinquish the RID certification(s) you currently hold, click here.

This form is required to be notarized.

38

Ethical Violation

Decision Date: 1/8/2024

Member Name: Kylie Kirkpatrick

Tenet Violations Found:

2. Interpreters possess the professional skills and knowledge required for the specific interpreting situation.

4. Interpreters demonstrate respect for consumers.

6. Interpreters maintain ethical business practices.

Sanction:

Revocation of certification and membership and eligibility for same for no less than three years. Any application for reestablishment of eligibility for certification must be supported by satisfactory evidence of professionalism and honesty.

39

VIEWS

40

VIEWS, RID’s digital publication, is dedicated to the interpreting profession. As a part of RID’s strategic goals, we focus on providing interpreters with the educational tools they need to excel in their profession. VIEWS aims to inspire thoughtful discussions among practitioners by providing information about research and insight into various specialty fields in the interpreting profession. With the establishment of the VIEWS Board of Editors, the featured content in this publication is peer-reviewed and standardized according to our bilingual review process. VIEWS utilizes a bilingual framework to facilitate knowledge sharing among all parties in an extremely diverse profession. As an organization, we value the experiences and expertise of interpreters from every cultural, linguistic, and educational background. We aim to explore the interpreters’ role within this demanding social and political environment by promoting content with complex layers of experience and meaning.

SUBMISSIONS

VIEWS publishes articles on matters of interest and concern to the membership. Submissions that are essentially interpersonal exchanges, editorials or statements of opinion are not appropriate as articles and may remain unpublished, run as a letter to the editor, position paper, or column. Submissions that are simply the description of programs and services in the community with no discussion may be redirected to the advertising department. Articles should be 2,000 words or fewer. If you require more space, the article may be broken into multiple parts and released over consecutive issues. Unsigned articles will not be published. RID reserves the right to limit the quantity and frequency of articles published in VIEWS written by a single author(s). Receipt by RID of a submission does not guarantee its publication. RID reserves the right to edit, excerpt or refuse to publish any submission. Publication of an advertisement does not constitute RID’s endorsement or approval of the advertiser, nor does RID guarantee the accuracy of information given in an advertisement. Advertising specifications can be found at https://rid.org/about/advertising/, or by contacting advertising@rid.org.

Please submit your piece using the submission form found here. All submission and permission inquiries should be directed here

COPYRIGHT

VIEWS is published quarterly by the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc. Statements of fact or opinion are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinion of RID. The author(s), not RID, is responsible for the content of submissions published in VIEWS.

STATEMENT OF OWNERSHIP

VIEWS (ISSN 0277-7088) is published quarterly by the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc. Periodical postage paid in Stone Mountain, GA and other mailing offices by The Sauers Group, Inc. Materials may not be reproduced or reprinted in whole or in part without written permission. Contact publications@rid.org for permission inquiries and requests.

VIEWS’ electronic subscription is a membership benefit and is covered in the cost of RID membership dues.

VIEWS Board of Editors: Brooke Roberts, VIEWS Editor in Chief Elisa Maroney, PhD, CI & CT, NIC, Ed:K-12

© 2024 Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc. All rights reserved.

41

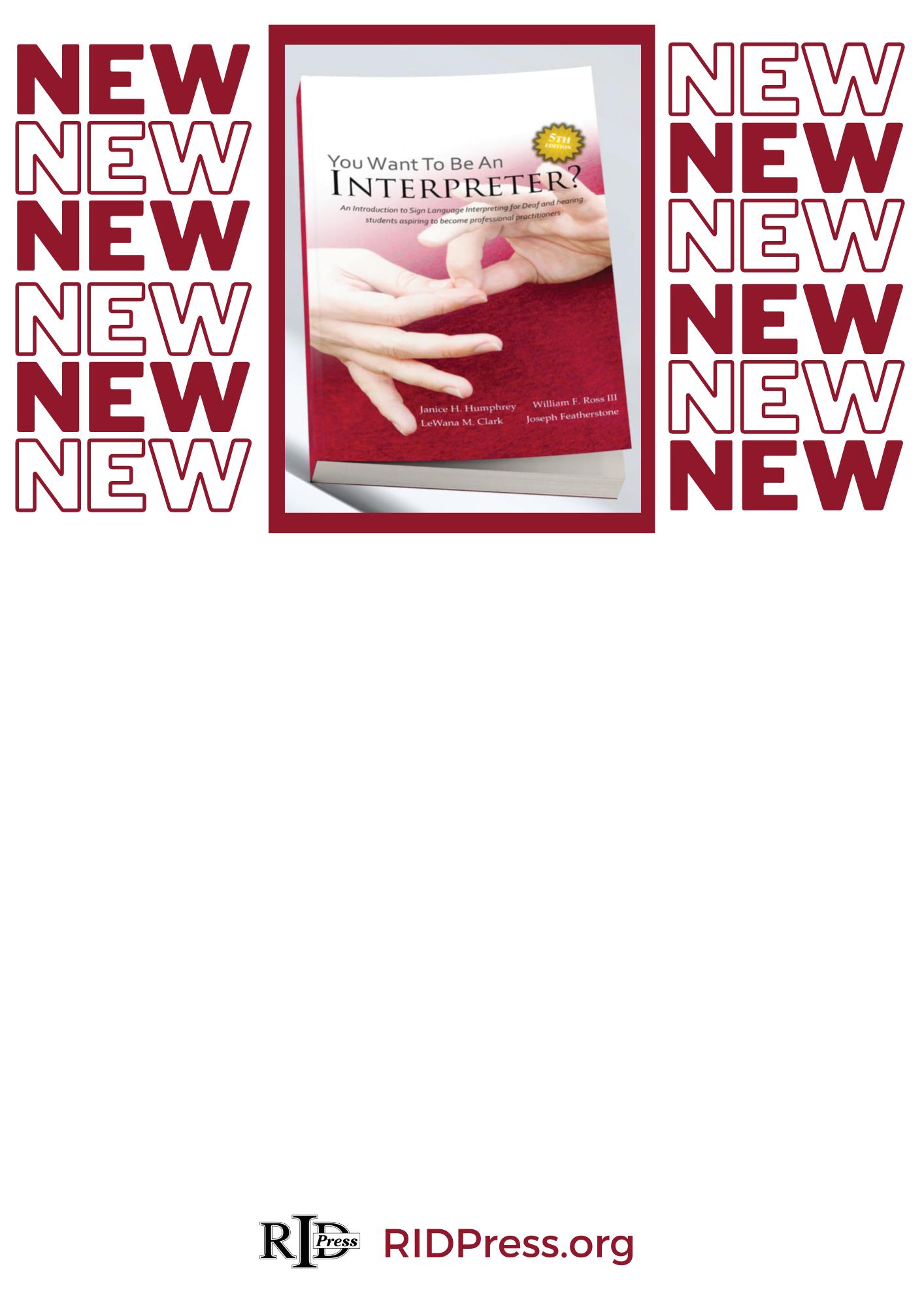

Check out our new title in the RID Press store!

The authors of this entry-level textbook are excited about your desire to become a Sign Language interpreter and have done our best to provide you with a guide as you begin this journey.

Regardless of your background, if you want to be an interpreter, this book is for you! Here, you will find an introduction and pathway to working as a sign language interpreter, understanding the in’s and out’s of professional practice, ethical guidelines to inform your decision making, and the complexities of creating messages that start in one language and end in another, while maintaining the same meaning and impact. You will learn about the history of the interpreting profession, professional associations, and the credentialing processes in the US and Canada. You will also discover the nuts and bolts of working in different types of assignments.

This revised and updated edition is the work of a team of authors who have a total of over 150 years of experience interpreting and teaching, joined by invited guest authors and members of a Deaf interpreter focus group who have shared insightful contributions as well as feedback from recognized leaders in our profession, past and present.

Star Grieser | RID CEO MA, CDI, ICE-CCP

Star Grieser | RID CEO MA, CDI, ICE-CCP