16 minute read

AoomONAL CLARIFICATIONS

What can an institution established for the purpose of territorial conquest and imperialistic submission have in common with one intended to safeguard a government system so highly varied from an anthropic, economic and legal aspect? Indeed, only the use of weapons, though for diametrically contrasting reasons: a wolf transformed into a watch dog, its size and fangs remaining unaltered! Starting with this last affirmation we can evoke a Roman army that differs from the usual stereotype of brutality and violence, slaughter and victories, deportations and slavery. Certainly these tragic aspects did exist over a period of almost ten centuries, but there was also order and legality, discipline and civility. progress and well-being.

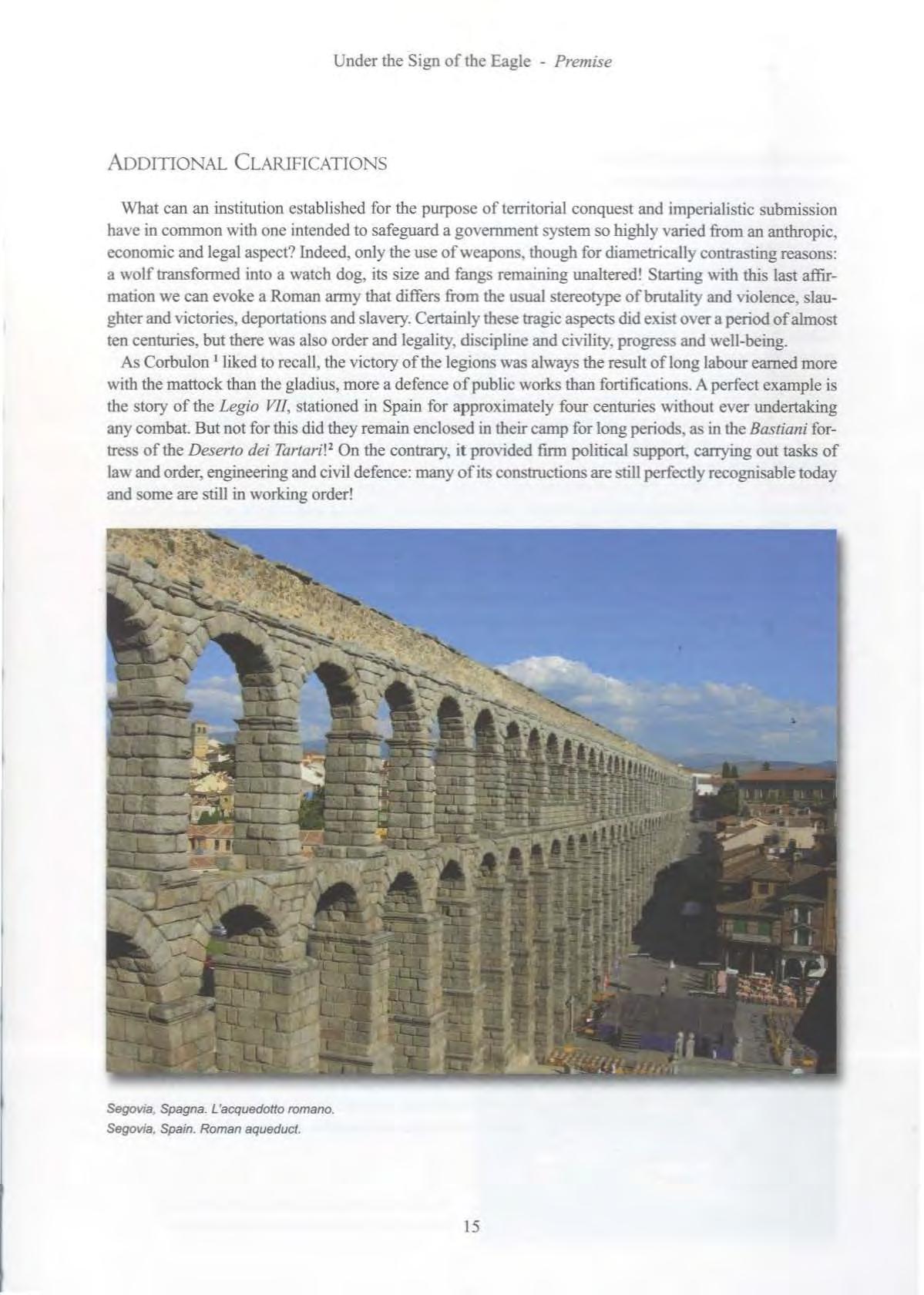

As Corbulon 1 liked to recall, the victory of the legions was always the result of long labour earned more with the mattock than the gladius, more a defence of public works than fortifications. A perfect example is the story of the Legio VII, stationed in Spain for approximately four centuries without ever undertaking any combat. But not for this did they remain enclosed in their camp for long periods, as in the Bastiani fortress of the Deserto dei Tartari! 2 On the contrary, it provided firm political support, carrying out tasks of law and order, engineering and civil defence: many of its constructions are still perfectly recognisable today and some are still in working order!

Advertisement

Though reporting and describing the salient military characteristics of the army of the Monarchical, Republican and Decadence era, our reconstruction wiH focus more on the characteristics of the Imperial Era. The study will thus extend to the vast range of activities undertaken by the army and that are by far its greatest expression. Taken as a whole, these activities will constitute the cultural and technical foundation of the entire West. Specifically language, laws, currency, measurements and later even religion to mention only a few of the principal contributions, will become the true common factor of the entire Empire, to the extent that even the Christian credo wi ll , from a certain moment on, become its moral buttress and the very source of Western culture. In truth, the new faith did not support the State, even when its soon to come decline became self-evident. If anything, its deep ideological abhorrence of the military institution, widely shared by those enjoying luxury and indolence, accelerated its demise. Thus, for example, wrote Hippolytus in the year 215 concerning the rules to be followed in accepting any new members: "the soldier under authority shall not kill the enemy. Ifhe is ordered to do so, he shall not carry out the order, nor shall he take the oath. Ifhe is unwilling, let him be rejected. The magistrate who wears the purple, let him cease or be rejected. And if a catechumen wishes to be a soldier, he shall be rejected,for in hating other men, he hates God."3

This extremely rigid prohibition, lacking any ambiguity, did not long survive for long for in the meantime the general situation was also precipitating, and so the rigid ban was circumvented by claiming that the defence of the Empire was actuall y the defence of the Church and of Christianity itself. The soldiers would thus be fighting in the name of Christ and when forced to kill the fault would lie with the assailant who bad forced them to take this action! But such a hypocritical change of heart arrived too late as the combative spirit, already seriously compromised by indolence and luxury, had been vanquished. Increasingly higher stipends to entice the reluctant and increasingly grandiose and expen sive defensive structures attempted to make up for the deficiency in the number of men: solutions that soon led to an exasperated and brutal fiscal policy that further worsened the situation. At the conclusion of its agony, the Empire will not fall because of the pressure of the barbarians, for in actual fact such pressure may not even have actually existed as their arrival was more (as we can easily understand today) a migration than an invasion, and one sufficiently easy to manage and to channel. The end, and on this many scholars agree, was a capitulation to an internal aggression cond ucted by a criminality that was the direct result of poverty. It was a perverse circuit, a vicious cycle of merciless fiscalism, an arrest of the market and a social repression that, added to an abhorrence of the military activity, increasing ly loathsome because of the admission of barbarians into the army that finally led to the collapse of the Wes t ern Empire.

A Strange Characteristic

The lack of solidarity between the civilian population and the military component, openly manifest during the Late Empire, displayed its premonitory symptoms as early as the Vulgar era. And probably the first signs of separation between the army and the c itize ns appear in the wealthy cities far from the frontiers, where from a certain time onward the presence of the legions is pe rceived as that of an occupation force rather than a defence force. If we observe the perimete r walls ofPompeii, the best preserved of the Ist century and those that, following the catastrophe of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 B.C., appear to have escaped the subsequent habitual and radical requalification, we note a rather singular feature.• In many respects it reminds us of the large r Greek city walls, and in fact this structure was mostly of Greek manufacture, where defence was provided by a mercenary force. The political and economic context is the period of the greatest prosperity and dynamism of the Empire, with Europe almost fully subjugated. the Mediterranean reduced to a R oman lake and no enemy ships to be feared: there was nothing that hinted at any possible enemy attack, from land or sea. Yet the walls ofPompeii have towers that project both outward and inward as well as a double parapet along the communication trench, also facing toward the interior and the exterior, a characteristic that makes the entire structure capable of resisting on two fronts and only s lightly less effective in the event of an attack from the rear.

In other words, walls structured in such a manner as to resist sieges against the city from the exterior but also from within the city itself, obviously against its own armed force. The initial explanation for this system is the will to resist to the bitter end: even if the city falls, the walls continue their function, exactly like a Renaissance stronghold. But the analogy is deceiving, as the city walls had neither this function nor this concept: when a city falls, the walls surrounding it no longer have any military purpose or possibility of survival! Leading to the conclusion that the purpose of the double parapet was not to resist on both sides, but to resist possible public uprisings! A loyalty not unlike what the Romans expected from auxiliary uruts, who not incidentally and in many cases, defected. Over time and with the affirmation of Christianity, diffidence increased rather than decreased, creating a quasi dichotomy between the military world and the civilian world, benefiting neither the institutions, the people, or the Empire.

A MlNrMuM OF CLARITY

For centuries now we have been saying, with the Dostalgia typical of those on the decline, that the inhabitants of Italy are the direct descendants of the Romans, the good-natured grandchildren of aggressive ancestors. In reality the only aspect we would seem to have in common is geographical. In his meticulous study of southern Italy 5 , Giuseppe Galasso makes a number of correlations and reaches the conclusion that the great majority of its current population is the direct descendant of the people that inhabited the very same districts in the VI century AD. In other words, after the dissolution of the empire and following the conspicuous migrations of the barbarians. Considering that in the VI century the population of the south and of a good part of the rest ofltaly was the population that bad survived the Roman conquest and, especially. the servile class of the landed estate, it is absurd to search for Roman characteristics from that most humble assembly. Which leads to a second conclusion: if this occurred in the most tormented area of the peninsula, occupied and colonised repeatedly from the north by progeny of Germanic origin and from the south of Arab origin, the persistence of such characteristics would be even stronger in the European regions. It is thus logical to suppose that the human legacy of the Roman army, more behavioural than physical, would be more obvious in the territories contiguous to the great limes, where the great legionnaire contingents were stationed for centuries, leading to a significant ethnic evolution. It such case, it would also be plausible to venture that the mythical Prussian militarism did not descend directly from a Teutonic order but may be the final derivation of the legions, as seems to be suggested by its combat and territorial control tactics.'

This is nothing new, at least in general terms, but it is in observing hereditary features that we can glean an even tenuous idea of the character of ancestors, and ours were of a completely different origin and nature. Our greater propensity toward juridical disciplines, the religious and ideological sophism for which our peninsula has always been the cradle and our modest response to violence and supine acceptance of foreign aggressions, often presage of lengthy dynasties, are indirect confirmation. With such a foundation, not necessarily negative in its consequences, our historiograpby is doubtless the most appropriate for cultural, geographic and linguistic reasons to trace a historical picture of the Roman army but, at the same time, the least suitable to penetrate its menta)jty and underlying logic. And. regrettably, because of our renowned aversion to technical disciplines, it is also the least able to comprehend the re- levance and variety of the initiatives and activities of the legions in every corner of the Empire that facilitated the progress of civilisation. For these reasons it comes as no surprise that the majority of research is German, British, French and often even Spanish and that we limit ourselves, in the best of hypotheses, to simply translating their analyses. Not even our language, which more than any other neoLatin language resembles the ancient one of the Romans, was sufficient incentive to undertake more accurate and serious inquiries on the activities of this grandiose institution. A deficiency that leads to obvious technical approximations and serious formal improprieties. deleterious for any scientific study but intolerable when one considers our close etymological affinity. For this reason and to attempt a different approach to this topic, it seemed fitting to begin with an etymological analysis of the words and definitions that will be used frequently in this chronicle and that are too often confused.

Meaning Of Army

Etymologically, it is very clear that this word has :remained unaltered in Italian: the word esercito coming from the Latin exercitus which, in turn, comes from the verb exerceo meaning addestro (1 train), tengo in esercizio (I maintain in exercise). Up to this point everything seems logical and normal, justifying those who perceive in this word a distinctive peculiarity of our armed force. The word in fact does not refer, as was the case with the majority of other nations, to the destructive logic of weapons, as does Army, for example, for the United States and Britain and Arme' for the French, but to the peaceful example of exercise, of work. A concept that confirms the primacy of technical capability over the use of arms.

Not stopping, however, at appearance, in this case to the sole Latin etymon, in endeavouring to identify the more archaic term from which it derives it does not escape us, to remain with Latin, that the verb esercitare is composed of ex meaningjiJori (out) and arcere meaning spingere (to push), giving the meaning spingerefoori (to push out),far uscire (to let out), stimolare (to stimulate) and, in a wider sense,far lavorare (cause to work), sol/ecitare (to solicit), stancare (to tire) and finally also addestrare (to train). This, far from confirming the preceding etymology, places it rather in doubt, as it is not clear what could be meant by spingerefoori (push out), or who and from what should be made to get out.

For other scholars the explanation is innate in the fact that it does not derive from the verb arcere but from the noun arce, which meansfortezza (fortress), rocca (stronghold) from which we get our area (arc): in such case the meaning would befuori del/a rocca (outside the stronghold),foori dellafortificazione (outside the fortification) and by extension all those who are conducted outside of the defences, obviously to confront the enemy. A meaning that is doubtless more fitting. To further strengthen this second theory we have the etymology of arco (arch) deriving from the Latin arcus having the generic meaning of arma (weapon or arm), from which descended arceo, respingo il nemico (I thrust back the enemy), obviously using arms. And here we are back to the starting point, as we easily deduce the comprehensive meaning of an active defence conducted with the use of arms: a concept fitting to the Constitution, but far from the above edulcorated interpretation. In any event the concept of the use of arms is present even in the etymon of exercitus, esercito (army), then as now!

The Meaning Of Legion

The Latin etymology oflegion, legio-legionis, comes from the verb legere meaning raccogliere (to collect), adunare(to assemble) and radunare (to convene). The Latin legere, that for us becomes leggere, derives in turn, like the Greek word of the same period leg-ein, from the root lag= leg, meaning adunare (to assemble), raccogliere (to collect), vagliare (to examine). By reading the individual alphabetic symbols together we obtain the correct phonetic pronunciation of the entire word: by examining the individual men, that is, seleering and convening them, they attained the correct military formation of legion. The meaning thus incticates that introduction into the legions was neither automatic nor taken for granted, nor was it a mass entry as with medieval units where the only requirement was quantity. That acceptance was, instead, a sort of social promotion, a desired recognition that remained such for many centuries, almost a qualification without which the most prestigious political and administrative careers would have been definitively precluded.

Meaning Of Army

The term has always indicated a large formation of warships, a sufficient number of large ships to compose a line of ba tt le. It has now been replaced by the word fleet, a word with no etymological origin either in Greek or Latin. According to Guglielmotto, the members of the armada are admirals, captains, officers, commanders, sailors, skilled labou r, crews, rowers, machinists, in effect anyone who has any connection with the sea, with ships, their equipment and their machines. Very recently, beginning around the second half of the XIX century, the word 'armada' also began to be used to indicate the army, or a large part of the army, causing confusion when reading classical works.

Meaning Of Soldier

Even though this word also has an obvious etymological root in the Latin word solidus, soon to become soldus, or wages, a definition adopted at the time for gold and silver coins because of the solidity of their value, the word was not used in the military context until the modern era. The word soldato (soldier), in fact, comes from the Spanish soldato 1 , which defmed a person who was as-soldato (recruited) for tasks that were only marginally and partially inherent to armed defence . In other words, a paramilitary assigned to auxiliary tasks and lacking, by definition, the dignity of being an actual member of the military.

The qualification of soldier appears in I taly for the first time among the garrisons in the coastal towers of the kingdom ofNaples 8 , when two or more soldati were placed alongside a Spanish corporal, who assumed command of the garrisons by royal patent and with the pompous title of castellano. Appointed and recruited by the nearby universities and paid by them only for the summer, they were, in effect, seasonal workers, an anachronistic defi - nition for the legionnaire s of the Roman army, of whatever role, rank or period of service, even after the systematic payment of the stipendium, initially a government contribution to the adsidui, soldiers who bad to extend their period of service to the winter season because of wartime requirements. As for the meaning of the word stipendium, closely related to our own stipendio (stipe nd) , the word comes from stips-sti'pis, a small copper coin oflittle value. Logical to conclude that originally the service was not paid and that when and if there was any sort of remuneration this was a very modest allowance to alleviate the burdens of the less affluent. From a historical perspective and according to tradition, the military stipend was introduced during the siege ofVeii, which lasted from 406 to 396 B.C. This was apparently an expedient not intended to be systematically adopted, but the transformation of war from an annual and seasonal event to something constant and continuous, soon made it indispensable.'

Meaning Of Military

Once understood that it is not correct to define the members of the Roman army as soldati, what terms were then used to define its conscripts and more important, why? All sources concur on a single word, miles, or milite, a definition adopted only to a limited extent perhaps because it appears to apply more to paramilitary formations - highly ideological bodies ill inclined to submission to the State, having little in common with a national army. For some authors the difference between militia and army is in the temporary nature of the former and the permanence of the latter. In other words, a formation that comes together in view of a battle or a seasonal campaign and that disbands upon its conclusion is always amilitia. But one that remains permanently in service, independent of whether it is a period of peace or war, is considered an army. Viewed from this perspective, all the armies of antiquity, including the Roman one, were first militia and on ly later, and not always, did they develop into armies. This di stinc tion would explain the reason for the protracted use of the word milite for legionnaires, even when they were no longer such but had become what is better defined as pedites or foot-soldiers. But for the Romans, a miles was the military member in the fullest meaning of the word.

Concerning the etymology of the term, many scholars tend to believe that the word goes back to the very first institution of the army, formed by Romulus by selecting one thousand men from every tribe. According to this theory, every member was unus ex mille, uno dei mille (one of a thousand). Other scholars hold to a contrasting theory, that is, that the root of the word is mil, meaning convene, unite, with the addition of item as participial ending of the verb ire (to go), thus to convene a moderate number to go, to move, to march. In such case, mille would come from the word for unite. in the sense of a multitude!

Much clearer and probably more applicable is the following socio-etymological contention on the comprehensive meaning of militare. That the word comes:''from the Latin miles, militis, is obvious; but where does miles come from? The more informed texts cite the word milleria, a tactical unit ofthe Roman army during thefirst period ofthe Monarchy (753-51 0 B. C.) that supposedly consisted ofone thousand men.· from this number therefore, the name.

And what is a number? Today it is no more than a pure and simple indication ofquantity; but such was not the case for our ancestors who considered a number as the synthetic expression of certain truths or laws, whose ideas were found in God, in man and in nature (that is, in the sk): the earth and in the mediator between these two.for such is man by divine will). In other ..:ords, numbers were sacred mathematics, its cradle being Chaldea; from here it probably passed to Egjpt, into Palestine, to the Greek world and, finally, to the Italic peninsula where its greatest and best known proponent was Pythagoras ofSamos (VI century B. C.).

It is almost impossible to provide a synthetic explanation ofthis highest and most archaic ofphilosophies; but we can give an example that may serve also - and especially- to explain the troe meaning ofthe number mille (one thousand), and thus ofthe word miles. Lets try.

One is God, the prime Being, the creator ofall, from whom all originates and emanates. 'flze numbers that follow- thosefrom two to nine - are nothing more than the various aspects ofthe manifest and material Nine is followed by ten, the number that expresses the level known as 'animate matter 'and whose productive activity is manifested in the numbers between eleven and ninety-nine. Ten means therefore that God is within us, in our matter: Further up, beyond the material/eve/, there is another level in man, that of the spirit, the site of feelings and ofthe mysterious Vital Force, that subtlefluid that the Ancients believed to be in the blood ... In numerical terms, we are now on the level ofhundreds- that is, the numbers from one hwzdred to nine hundred ninety-nine- where all originates from ten to the second power (ten squared equals one hundred). One hundred, which means - as we now know- God is within us, in our spirit. Similar arguments are also valid, obfor the number one thousand (one thousand equals ten to the third pol1'er) which, in the language of sacred mathematics indicates that God has also penetrated the soul ofman, the third and last -and highestcomponent. 'fl1erefore, purification, the spiritual catharsis ofman, has been accomplished three times: at ten it conquered matter, at one hundred it beca lmed passion, at one thousand it sublimated the spirit. Thus every obscure trace of instinct has now disappeared, and all in him is candid and resplendent: the l-.·arrior is thus dedicated solely to an idea and is ready to enter the field and to fight as a miles who is part ofthe milleria. The temzs miles and milleria qualifYing not physicalforce as such (that ofone man in one case and ofa thousand in the other) but a pure spiritual a nd animistic power. the highest level man can hope to reach " 10

Notes

1 -On Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo cf. P. C. TACITUS, Annals, books 1-Vl For a more detailed report on his military activities cf. M. A. LEVI, L 'impero romano, Torino 1967, vol. I, pp.285-303.

2- Cf. D. BUZZANTI, 11 deserto dei Tartari, ed. Milan 1940.

3- Quotation is from U. BROCCOLI, L'inferno in terra, inARCHEO, n°ll, November 2007, p.l03.

4- Cf. F. RUSSO, F. RUSSO, 89 a. C. Assedio a Pompei, Pompeii 2005., pp. 64-69.

5- From G. GALASSO, L'altra Europa, Milan 1982, pp.19-25.

6- Cf. F. L. CARSTEN, Le origini de/la Prussia, Bologna 1982, pp. 19-21.

7- Cf. R. A. PRESTON, S. F. WISE, Teoria sociale della guerra, Verona 1973, pp.l33. Additional infonnation cf. R. PUDDU, fl soldato gentiluomo. Autoritratto di una societa guerriera: la Spagna del Cinquecento, Bologna 1982, pp. 145 and foll. By the same author, Eserciti e monarchie nazionali nei secoli XV-XVI, Florence 1975, pp. 27-34.

8- Cf. F. RUSSO, Le torri anticorsare vicereali, Naples 2001, pp. 185- 192.

9 - Cf. J. WACHER, Il mondo di Roma imperiale, Bari 1989, p. 88.

10 -From G. CERBO, F. RUSSO , Parole e pensieri. Raccolta di curiosita linguistico-mili tari, Roma 2000.

L