8 minute read

At the origins of Rome

Amilitary organisation presupposes the existence of an urban or state system, one that is well defmed throughout the territory, for without this mandatory definition the 'organisation' would be not more than an ephemeral formation of raiders and marauders. Obviously Italy did not escape this subordination and so it is correct to speak of armies in Italy only after the founding of their respective cities, which the difficult morphology of the country placed at the mouths of rivers. Not so distant from the sea as to lose its advantages nor so close as to fear incursions! In his monumental Storia di Roma antica, Mommsen describes the territory where the city par excellence would be founded as:"approximately three miles from the mouth of the Tiber, hills ofmoderate elevation rise on both banks, higher on the right, lower on the left bank. With the latter group there has been closely associated for at least two thousand five hundred years the name ofthe Romans. We are unable, ofcourse, to tell how or when that name arose; this much only is certain, that in the oldest form known to us the inhabitants of the canton are called not Romans but Ramnians (Ramnes), and this shifting ofsound, which frequently occurs in the older period ofa language, but fell very early into abeyance in Latin, is an expressive testimony to the immemorial antiquity of the name. Its derivation cannot be given with certainty, possibly Romans may mean 'the people of the stream'. But they were not alone on the hills by the banks of the Tiber. A trace has been preserved ofthe division ofthe ancient Roman citizenry, indicating that the body rose out ofthe fusion ofthree groups once probably independent, the Ramnians, the Tities and the Luceres, that then became an independent republic; out ofsuch a synoikismos as that from which Athens arose in Attica.''1

The author makes another interesting observation concerning this site and that is that he considered it incorrect, in the case of Rome, to speak of a founding similar to that of any generic city, as narrated in legend, since it was not built in a day. And he believed it to be highly significant that Rome earned such a pre-eminent political position in Latium so rapidly, when the difficult characteristics of its territory would suggest the opposite. A soil that was much less fertile and less healthy than that of the majority of other ancient Latin cities, one that was poor in springs and devastated by the frequent overflows of the Tiber. 2 On the other hand:"no site was more suitable than Rome, both as the trade centre for fluvial and maritime Latin commerce, and as the maritime stronghold ofLatium, because it had the advantage of a strong position and an immediate vicinity to the river; it commanded the two coasts up to the mouth of the river and was equally favourable and comfortable to the navigators of the river, descendingfrom the Tiber and the Aniene, and those of the sea, given the mediocre size ofships at the time; a site, finally, that offered greater shelter from piracy than other sites located on the coast itself"3

Advertisement

Considering that the Tyrrhenian from the Straits of Messina upward has very few natural ports that could fulfil the needs of ancient navigation, this interpretation appears extremely likely and sufficient to justify a settlement in an unfortunate environmental context, with swamps and marshes to the south and north, as it was the only satisfactory landing place from Gaeta to Civitavecchia. In other words, Rome appeared to reproduce in miniature the destiny of Troy, a city-fortress located near the mouth of a river, ideal for the control of merchant shipping.

A strategic choice that reveals the mili taristic and imperialistic matrix of the city from its vel) beginning. Thus: "in this sense, as confirmed by the le- gend, Rome may have been a city that was created rather than developed, and of the Latin cities, the youngest rather than the oldest it is not possible to guess whether Rome came to life because of a decision made by the Latin league, or because of the genial idea ofa forgotten founder of the city, or due to the natural development of commercial conditions. ''4 Accepting the theory as valid, it is interesting to note that the most frequen tl y adopted fortification for hill settlements, typical of the era, consisted of a rampart running aro u nd the top or along its slope, not necessarily closed, and constructed of large stones installed dry. The sol id ity of the structure, defmed in technical terms as polygonal. cyclopic, megalithic or pelagic, derives from the inertia of the blocks of stone, while its defence capability was based on the possibility of weakening the waves of enemy attacks. It was, in effect, a sort of grand staircase that could not be ascended rapidly and contcmporaneously en masse, allowing the defenders to s l aughter the attackers. This was very similar to the tactics used in the confrontation between the Horatii and the Curiatii, transposed into a system of defence.

Archaic Settlements Of The Latium

If the perimeter fortification had to be similar to the one described above, the settlement of primitive Rome could not, in turn, differ greatly from the primary urbanistic plan used throughout the Latium region of the era. In detail:"in order to place themselves in a stronger position, these primitive centres often exploited the natural conditions of the terrain, settling on the heights ofsteep and rocky crags that could easily protect them Such a fortified town would be located at the confluence of two trenches,forming a triangle or rectangle, with two or three sides naturally protected, leaving only the last side, where the hill continued upward, to be defended. Using the favourable conditions of the terrain, like a dominant cliff or the convergence ofsmall lateral valleys, the hill was isolated by a barrier that usually consisted ofa wall and a ditch. We know ofmany ofsuch oppida and the same system was still in use during the Republican era. " 5

This type of fortification was substantially and widely used even where the geologic conformation of the hill was calcareous rather than tufaceous, a common feature along the central Apennines, the area settled by the Italics. Such fortifications were generally described as arx 6 , a name perfectly fitting to the already mentioned etymology of army. There is also a curious coincidence innate to this type of fortification: its initial defence, and the most lethal, was to hurl spears and javelins against the hordes attempting to climb the slopes, to the extent of considering such a tactic as complementary to that structure. The two largest ethnic groups that contended extensively for military supremacy, the Samnites and the Romans, both took their name from the spear: quiriti in fact means the people of the spear, and samnites the people of the sannia, a squat Italic javelin.' Reference to the spear is also found in several other Latin terms such as populus, similar to popolari=to devastate, found in the ancient litanies called pilumnus poplus, the militia armed with a spear, also called pi/us.

Legend And Tradition

According to tradition, the period of the Roman monarchy, that of the famous seven kings on the seven hills, extends from 753 B.C. to 509 B.C. The likelihood of such a dynastic evocation can be demonstrated by a simple division 8 : each king would have had to reign an average of 33 years, a rather significant period to say the least! In reality, and following the destruction of the few written sources during the Gallic raids of390 B. C., the origins of Rome remained enveloped in mystery. During theAugustan era, such writers as Livy attempted to mitigate this mystery by reconstructing, or better yet, theorising what would have been a suitable past for the city. Legend was thus replaced by myth, without the least changing the historical unreality, though narration did at times adhere to specific crucial events. But if the evocation is not fully credible, neither is it completely false, since it does appear that there was a Monarchy between 500 and 450 B.C. And it is also likely that there was a phase of Etruscan domination that, based on archaeological evidence, probably dates to around 600 B.C., coinciding with the paving of the forum to cover the sewer network. 9

But evidence aside, Roman historians attributed the founding of the city and the monarchy to Ramulus: according to tradition, he was the nephew of Aeneas, the direct genetic link between a city that was already legend and one that was destined to become one. Who better than he could have been its first king?

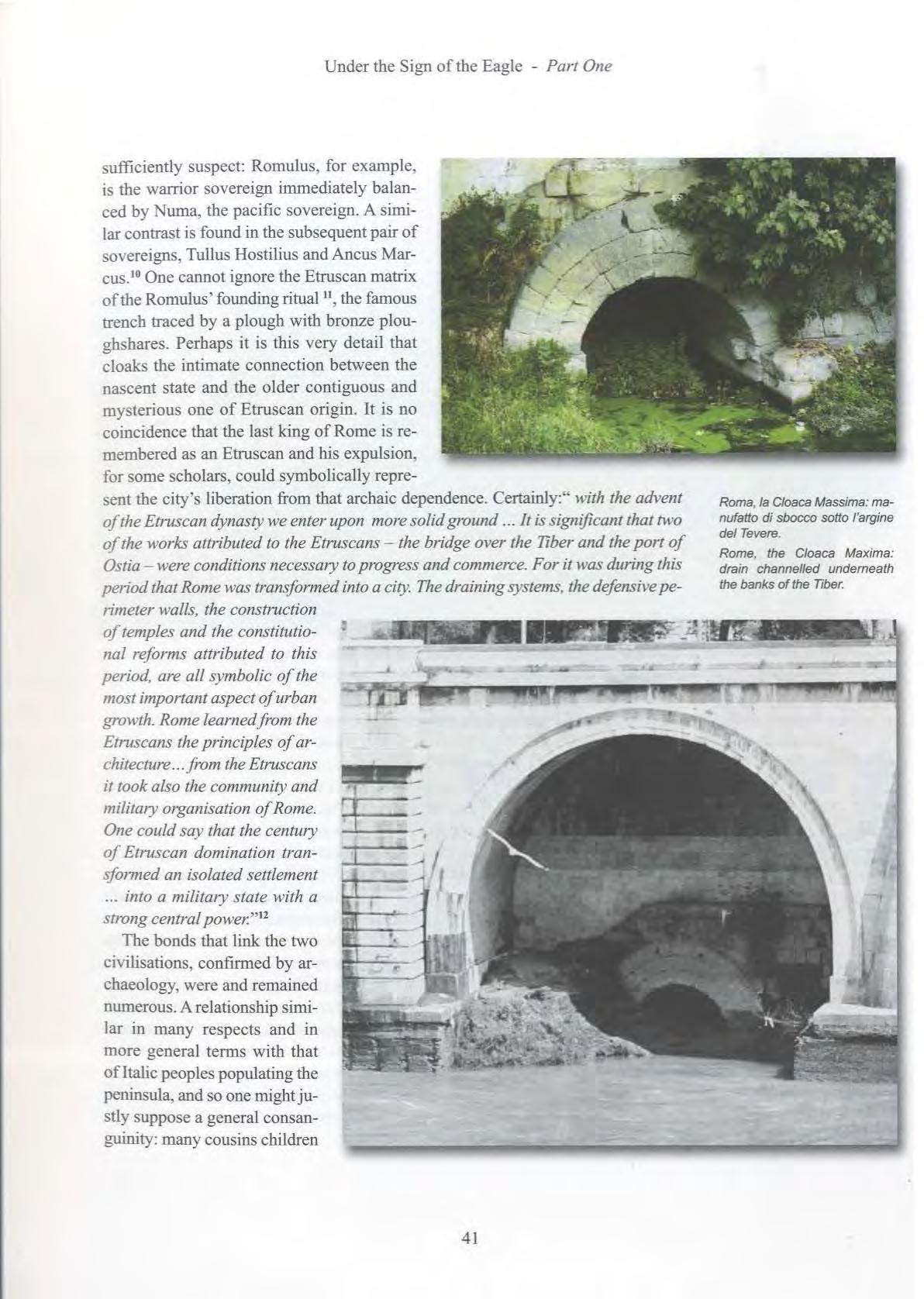

Less prosaically it appears all too obvious that the first four kings are a synthesis of mythology and popular narration relating to heroes who had certainly existed, with historical inventions providing illustrious genealogies to the principal farnil ies of Rome. This strange combination of antithetical figures is sufficiently suspect: Romulus, for example, is the warrior sovereign immediately balanced by Numa, the pacific sovereign. A similar contrast is found in the subsequent pair of sovereigns, Tullus Hostilius and Ancus Marcus.10 One cannot ignore the Etruscan matrix of the Romulus' founding ritual 11 , the famous trench traced by a plough with bronze ploughshares. Perhaps it is this very detail that cloaks the intimate connection between the nascent state and the older contiguous and mysterious one of Etruscan origin. It is no coincidence that the last king of Rome is remembered as an Etruscan and his expulsion, for some scholars, could symbolically represent the city's liberation from that archaic dependence. Certainly:" with the advent ofthe Etruscan dynasty we enter upon more solid ground ... It is significant that two of the works attributed to the Etruscans - the bridge over the 1iber and the port of Ostia - were conditions necessary to progress and commerce. For it was during this period that Rome was transformed into a city. The draining systems, the defensive perimeter walls, the construction of temples and the constitutional reforms attributed to this period, are all symbolic of the most important aspect ofurban growth. Rome learned from the Etruscans the principles of arc hitecture from theEtruscans it took also the community and military organisation ofRome. One could say that the century of Etruscan domination transformed an isolated settlement into a military state with a strong central power."12

The bonds that link the two civilisations, confirmed by archaeology, were and remained numerous. A relationship similar in many respects and in more general terms with that ofltalic peoples populating the peninsula, and so one might justly suppose a general consanguinity: many cousins children of few brothers! According to the ancient historians, Romulus founded the city, while for many modem ones be simply limited himself to unifying into a single organism a plethora of small villages called pagi, huddling on the various hills that emerged from the enormous swamp of the middle course of the Tiber, swamp that a series of drains about a hundred kilometres in length, attempted to reclaim for centuries. The celebrated French scholar De La Blanchere maintained in some of his works, published in 1882, that without those drains, consisting of very narrow passages, Rome would not even have existed! 13 A confederation of numerous settlements that initially appeared to be homogeneous, inhabited by as many tribes, confirmed by the least likely tradition.

Almost as if to confirm this fact, the hill that witnessed the infancy of Romulus and that later became the site of the imperial residence, the Palatine, has restored the most ancient settlements, some dating to 800 B.C., to archaeological excavations. Recently identified was the grotto where, according to tradition and in that historical period, the wolf milk-fed the two twins, a winding gorge richly decorated during the Augustan era. 14 Also dating to the same era are the villages on the Quirinale, the Esquilino and the Viminale hills, villages that the rough morphology of the sites, with its deep incisions and wide marshes had long kept totally autonomous and separate, though not distant. We cannot exclude that the reason for the closer contacts among the different settlements and their eventual unification into a substantial residential unit of moderate size, was determined not so much by the will ofRomulus as by the increase in the population. When this fusion did take place, Romulus made use of the critical human mass to organise the archetypical regular armed force of Rome.

Sopra: interni di cunicoli di drenaggio: Faicchio (BN) e Veio (LT).

Sotto: Roma, inferno del/a grotta sotto la Domus Aurea.

Above: interior of the drain passages: Faicchio (BN) and Veii (LT).

Below: Rome, interior of the grotto underneath the Domus A urea.