22 minute read

THE MARCH OF THE GIGAFACTORIES

The booming demand for batteries is going to have to be met somehow — and gigafactories are being conceived, planned and built at breakneck speed. Frank Millard reports on Europe’s moves.

The march of the

Insatiable. That’s the only word to describe Europe’s frantic demand for energy storage in the years ahead. In the rush to decarbonization the continent is setting ever tougher CO2 emission targets.

Fossil fuels — be they for powering industry, the home or transport — are going to be phased out. Instead renewables will become a vital part of the new energy mix. And with renewables comes this insatiable demand for energy storage.

To meet this growing demand, gigafactories are being conceived, planned and built. Although the buzz word here is lithium — it’s not just factories for lithium-ion batteries that will be needed: next generation batteries emerging from other chemistries are also going to need a manufacturing home as countries increasingly adopt intermittent energy sources such as wind and solar.

Caspar Rawles, head of price assessments with Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, says his firm is tracking 211 supersized (greater than 1GWh capacity) lithium-ion battery plants globally, either in operation, construction or in a planning phase, totalling more than 3.8TWh of planned capacity by 2030.

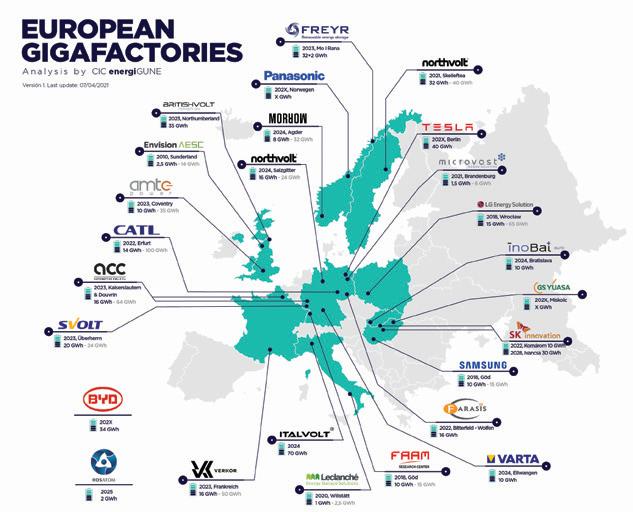

In Europe he predicts that by 2030 there could be 22 gigafactories, at whatever stage of readiness, with a total annual capacity of 621GWh.

“This is more than enough pipeline capacity but not all of these plants will make the quality of cells required,” says Rawles. “It isn’t guaranteed that they will make it to production, and we are starting to see smaller operators face financial difficulties as competition grows within the space.”

The Spanish research centre for electrochemical and thermal energy storage, CIC energiGUNE, does not agree that the proposed capacity for Europe will be enough. It claims that even if all 22 factory projects come to fruition and produce an annual total of 600GWh, it will only meet half of the expected base demand in the continent.

And this is just batteries for electric vehicles — stationary storage applications are not even factored in.

Just one company, Tesvolt, has confirmed it is focusing on batteries for stationary storage: in Germany, it was the first company to build a gigafactory in Europe dedicated to stationary ESSs, and began production in April 2020.

The facility at Lutherstadt Wittenberg has a production area of 12,000m², where it makes battery storage systems of various sizes with storage capacities ranging from 9.6kWh into the multiMWs.

Italvolt to build largest factory in Europe

Italvolt is one example of the new size of factory being planned and built in Europe.

Taking over an abandoned Olivetti di Scarmagno plant, the 300,000m² gigafactory near Turin in Italy has a capacity of 45GWh, with the first construction phase due to be completed in spring 2024. The facility will employ 4,000 workers, and the wider ecosystem will provide up to 10,000 new jobs.

As well as the main facility, a research and technology centre is being developed in collaboration with the Politechnico University in Torino.

Raw materials will arrive on site and enter the production line, emerging as complete battery units of varying sizes

By 2030 Europe will have 22 gigafactories at some stage of readiness and a total annual capacity of 621GWh.

gigafactory

and capacity. These will be transported to a EV manufacturing site and installed directly into the vehicles.

Lars Carlstrom, CEO and founder of Italvolt and a car enthusiast, is particularly keen on the gigafactory being sited in Italy.

“Having worked within the sector (at Saab and others) for a number of years before starting Italvolt, I’m acutely aware of the importance of Italy to the automotive ecosystem — we cannot let that fade away, like it has done in Detroit,” he says.

Financing mammoth projects

Carlstrom says Italvolt has not yet entered into any public funding to pay for its mammoth factory, although he said there would be a discussion ‘at some point’.

At the moment, companies outside China are financing expansions from their own balance sheets, says Benchmark’s Rawles, but there is a growing interest from the financial industry in the sector.

“Typically, new operators, such as, are raising capital through traditional debt facilities,” he says. “We have also seen some capital raised for cell production via SPACs (special-purpose acquisition companies), which is something relatively new to the industry.”

The EU also sees battery manufacture as a green path to the future and is keen to help with financing. It has already provided cash through institutions such as the European Investment Bank, but more avenues have recently opened up.

Sara Ortíz, economic-financial director with CIC energiGUNE, says that several projects have announced they will apply for funding to build battery factories under the €672.5 billion ($815 billion) Recovery and Resilience Facility announced by the EU this February.

The funding is meant as a postpandemic stimulus package for members of the bloc, and grants and loans will be available ‘to finance national measures designed to alleviate the

economic and social consequences of the pandemic’.

To be eligible, projects must focus on the key EU policy areas described as ‘the green transition including biodiversity, digital transformation (where Ortíz suggests battery factories fit in), economic cohesion and competitiveness, and social and territorial cohesion’.

“Many of the projects announced in recent months have already announced their intention to apply for these funds in collaboration with the different national governments, intending to accelerate their launch and development process,” says Ortíz.

“Some of these executives have already informed the European Union of their specific plans to develop and invest in gigafactories located in their territories.”

Sustainability

Peter Harrop, chairman of electronics market research firm IDTechEx, believes the next 10 years will be fairly predictable in that the decade will include a mass movement towards building new gigafactories.

But he says there will be a time when the music stops.

“Then people who have been investing in gigafactories (‘because you can’t go wrong, can you?’) will probably find some stranded assets, but not until 15 years from now,” he says.

Although lithium batteries will still be in high demand for at least the next

UK TO NEED SEVEN GIGAFACTORIES

In a sector where China leads the world and the US and Europe are racing to catch up, recent UK government funding for gigafactories is all about levelling the playing field, says Stephen Gifford, head of economics and market insights at the UK Faraday Institution.

The Faraday Institution believes that one gigafactory will be needed in the UK by 2022, two by 2025 and seven by 2040. Employment in the automotive industry and battery supply chain could grow from 170,000 to 220,000 by 2040.

The UK government says it is dedicated to building gigafactories, and as part of prime minister Boris Johnson’s Ten Point Plan, announced in November 2020, the government said it would make £500 million ($710 million) available as part of a wider commitment of up to £1 billion ($1.4 billion) to support the electrification of vehicles and their supply chains, including developing gigafactories.

Moves were already in place to support the move towards developing a battery industry: in 2018 the UK Battery Industrialization Centre, created under the Faraday Institution, opened its doors to researchers, manufacturers and companies.

All kinds of support is offered there ‘to enable large-scale battery production opportunities’, such as providing equipment, advice, training and manufacturing knowhow, as well as taking the steps towards commercialization.

The UK’s SMMT (the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders) estimates that the UK will be manufacturing up to two million PHEVs a year by 2040, requiring a battery production capacity of 120GWh a year. With capacity currently 2.5GWh and just 13GWh planned there is a way to go, but the Faraday Report — March 2020 Annual Gigafactory Study UK: Electric Vehicle and Battery Production Potential to 2040 does predict there will be 140GWh a year by 2040.

Faraday suggests that EV production at the levels that will be required will almost certainly depend on the establishment of a secure domestic EV battery supply, meaning UKbased gigafactories.

Rumours of Tesla and Tesla-type gigafactories being built in the UK and elsewhere in Europe have proliferated but hopes were dashed when one was instead announced for Germany — the Tesla Berlin-Brandeburg Gigafactory is due to open this July, with a planned capacity of more than 100GWh a year.

That doesn’t mean the UK has been left out of Tesla’s plans — in March, business minister Kwasi Kwarteng hinted the carmaker had shown interest in Somerset, believed to be the Gravity site near Bridgewater.

Market speculation was that Brexit — the UK’s retreat from the European Union — advanced the case for Berlin but delayed Tesla’s plans.

But with or without Tesla, moves to build gigafactories in the UK are being drawn up, with some further ahead in the planning stages than others.

Britishvolt, ‘operational by 2023’

Isobel Sheldon, Britishvolt’s chief strategy officer, says total spending on Britishvolt’s state-of-the-art gigafactory at Blyth in the north of England is £2.6 billion ($3.7 billion), making it one of the largest industrial investments ever made in the UK.

“By the final phase of the project in 2027, it will be employing up to 3,000 highly skilled people producing more than 300,000 lithium-ion batteries for the UK automotive industry. It will further provide up to 5,000 jobs in the wider supply chain,” says Sheldon.

“Production will begin at the end of 2023 with the first phase seeing 10GWh of capacity installed, before ramping up to a total capacity of 30GWh by 2027.”

Plans to break ground this summer before beginning production at the end of 2023 remain on track.

Sheldon says that despite the pandemic, construction has continued for both industrial and domestic projects with no impact on deadlines.

The company is planning a flexible manufacturing approach, allowing it to move into different sectors rather than being limited to a single technology, or cell chemistry.

“ESG (environmental, social and governance) is at the core of our business and sustainability is paramount to the project,” says Sheldon.

“We are establishing a full digital twin (a complete replica of physical assets built with artificial algorithms that can help provide a real-world model for the actual processes) that

10 years, we are probably heading for severe battery shortages as a result of a lack of materials rather than a lack of the factories in which to process them, he says.

It takes a long time to bring a mine onstream and there are usually geopolitical considerations and obstructions.

There is a big push for cell plants to reduce emissions and in Europe particularly a number of plants use renewable power supplies to achieve carbon neutrality at their operations.

The EV supply chain is under scrutiny from an ESG perspective to ensure that the next generation of vehicles not only cut emissions at the tailpipe but also during production.

“Not only are we seeing the push to reduce emissions during cell production but also throughout the entire value chain from the mine,” says Rawles.

There must also be a greater push for getting recycled materials into battery manufacturing, and Italvolt is taking this on board, with plans to integrate a recycling plant with its gigafactory.

The company has already signed a memorandum of understanding with American Manganese, whose technology, Carlstrom says, will make it possible to recover 99.8% of all minerals in the battery.

UK TO NEED SEVEN GIGAFACTORIES

> Continued from page 58

will be fully running in quarter two of this year, giving us the opportunity to simulate production processes and flows ahead of construction completion. This enables us to optimize design and efficiencies ahead of completed construction and fitment.”

AMTE to build next year

Meanwhile, AMTE intends to build a facility in 2022, with a team analyzing detailed design and process engineering plans for three possible sites.

Output will start at 2GWh-3GWh, with a view to increasing to 10GWh using a modular plant design.

“The AMTE Power gigafactory will be sustainable and aligned with our ESG goals for the business, staff, and local groups,” says CEO Kevin Brundish.

Brundish says AMTE’s plant at Thurso, Scotland has successfully demonstrated the manufacturing process for all current lithium-ion blends, as well as lithium iron phosphate and the newest sodium-ion chemistry.

“Our new gigafactory facility will build on our development work, and bring product for the car battery and energy storage industries to market,” he says.

“Our differentiated product for the ESS cell market is ‘Ultra Safe’. It’s a safe and cost-effective rechargeable pouch format battery cell to address key applications in ESS, whether that’s microgrids or larger systems.”

AMTE plans to build a smart plant that has been drawn up with the help of HSSMi, a sustainable manufacturing innovation consultancy.

“We worked through the challenges of building a gigafactory using practical, problem-solving methodologies focused on three key areas: the scale-up of products and processes, productivity enhancing opportunities, and supporting the transition to a circular economy,” Brundish says.

And Coventry Airport has been selected as the preferred site for a West Midlands gigafactory.

Coventry looks to future

Coventry Airport Ltd and Coventry City Council have formed a joint venture to bring forward a planning application for a battery plant before an investor is even identified.

This is to make the site more attractive to prospective manufacturers and drastically speed up steps to operation.

Jim O’Boyle, cabinet member for jobs and regeneration at Coventry City Council, says a bid will be submitted for a share of the £500 million ($708 million) government fund for gigafactories in the UK.

“Plans are at a relatively early stage but discussions are ongoing with car and battery manufacturers to understand their requirements as we develop our planning application and our wider offer, including access to our world-leading supply chain and automotive eco-system,” he says.

The location of the site is ideal for the UK’s automotive industry, being close to major car makers such as Jaguar Land Rover and Aston Martin, as well as the London EV Company.

Coventry is also home to the new UK Battery Industrialization Centre, which is part of the government’s ‘Faraday Battery Challenge’ programme to speed up the development of battery technology. Imperium3 New York — iM3NY — announced on April 19 that it had secured $85 million in funding from investment firms Riverstone Credit Partners, Riverstone Holdings and Magnis Energy Technologies to back construction of a gigafactory at Endicott in New York State. iM3BY’s gigafactory is now fully funded and will be able to manufacture an initial capacity of 1GWh of battery cells a year.

The build-out of the gigafactory has begun with production scheduled for early 2022, and Paul Stratton, senior vice president of sales and marketing, said their first market would be the commercial and residential sectors.

“Although electric vehicles are a very attractive market where we believe our first product offers many competitive attributes, our first markets will focus on energy storage for solar and other sources, both commercial and residential,” he said.

“Our product will achieve extended life cycles over others, up to 4,500 at present and possibly many more as we gain more test data.”

The batteries will be those designed by Charge CCCV (C4V), an R&D company founded by Shailesh Upreti, who has worked with and continues to be mentored by Nobel laureate Stanley Whittingham.

C4V and iM3NY have worked together for 10 years and the batteries produced in the new gigafactory will use their patented ‘bio mineralization’ technology, which the company says creates higher capacity, safer and longer cycling batteries at a lower cost. “The company’s substantial growth plans include building out 32GWh of capacity over eight years, which will create direct employment opportunities for approximately 2,500 people,” iM3NY says.

AND IN NEW YORK…

Supply chains

Italvolt believes batteries must be produced locally to avoid long transport costs and more pollution going into the environment.

“Which, as we all know, is one of the key reasons behind electric vehicles in the first place,” says Carlstrom.

“Many batteries on the market today are considered ‘dirty batteries’ if they’re made in a factory powered by fossil fuels. Central governments across Europe must address this issue urgently, otherwise we’ll miss our zero emissions targets.”

In March, Italvolt signed a letter of intent with certification firm TÜV SÜV for technical advisory services such as sustainability, risk assessment and battery testing.

AMTE Power also aims for its facility to be as sustainable as possible.

Landscaping will be designed to improve the habitats for biodiversity and mitigate the visual impact of the facility, and every detail is being considered in how to keep facilities ‘green’.

“Where possible, off-site module construction will be used to reduce waste and CO2 in construction,” says Kevin Brundish, CEO of AMTE Power. “The manufacturing system will require sustainable power 24/7 — a modular energy centre will be used to harvest energy from solar arrays on the roof and landscaping.

SUPPLY CHAIN THREATS MULTIPLY

No battery manufacturing plant of any kind is viable without a guaranteed supply of raw materials. There is no shortage of raw materials, but the more that are needed, the less secure the supply chain becomes. In 2019 Richard Herrington, head of the Earth Sciences Department at the Natural History Museum in London wrote to the Committee on Climate Change warning that to meet electric car targets for 2050 the UK would need just under two times the world’s annual production of cobalt, nearly the entire world’s production of the rare earth neodymium, three quarters of the world’s lithium and at least half of the world’s copper.

Herrington, whose research looks into the behaviour of metals critical for the modern economy in earth systems, particularly cobalt and rare earth metals vital for battery manufacturing, says around 70% of cobalt comes from the DRC, ‘which has seen its share of uncertainties, politically and socially’.

“The added issue here is that 20% of the DRC supply comes from artisanal small miners, where there is evidence for practices such as child labour which is not something that should be supported,” he says.

“Cobalt has a further issue as a by-product metal, largely from copper mining, and this means that its supply can be erratic as mining practices change. Most of the cobalt is then refined in China and so that country effectively controls 70% of world supply.

“In the case of graphite, China has a similar monopoly since it produces around 62% of the world’s mined production of graphite. There are supply options such as Brazil, Mozambique and Norway which should hopefully guarantee a secure supply chain in an expanding market.

“Also, graphite can be produced as a byproduct of hydrocarbon processing but the future of that source could be uncertain.”

Lithium is roughly 50% produced in Australia from hard rock sources and 50% from Chile and Argentina from salar brines, however Herrington says expanding production in these areas is tricky as the Australian deposits are difficult to scale up and there are social issues with South America’s lithium supplies.

“The good news is that close-tomarket deposits of lithium are found in Serbia and more latterly potentially in Portugal, Germany, and Cornwall in the UK. Cornwall has the potential to supply around half of what the UK will need if the company reports are to be believed,” he says.

For stationary storage, Herrington says redox flow battery systems using multivalent metals such as vanadium will be challengers to lithium, although vanadium supply is also quite tight, with China controlling around 50% of the world’s available resources.

“There are alternative producers, but a key question will be whether the industry can double production to cope with the World Bank estimate of a 200% increase in demand needed before 2050. This is not as extreme as the 500% increases predicted for cobalt, graphite and lithium but still challenging to deliver in the time pledged.”

The development of gigafactories linked to car production plants makes sense as this can secure the main parts of the manufacturing supply chain, but it does not solve the issue of supply.

In theory, by about 2035 there will be enough end-of-life batteries around to provide up to 40% of the metals needed for new batteries, so recycling strategies will be essential and gigafactories linked to manufacturers could aid efficiency, Herrington says.

Circumventing the chain

Supply agreements are a clear way to get around the issues of transparency in the supply chain and for manufacturers it makes sense to make a deal with a miner directly so they know for sure where the metal comes from, says Herrington.

However, such agreements can lead to shortages for the open market, which in the worst case could drive manufacturers to source their metals on the open spot market, where information about their

Richard Herrington

“Battery energy storage systems will allow solar energy to be used overnight. Ground source heat pumps will provide background process energy. The design intent is to allow the system to export to the grid, giving instant energy for frequency stabilizers to keep the lights on.”

The march of the gigafactory is certainly on — but it will largely depend on whether the materials can be got through the front door.

EUROPE’S FIRST GIGAFACTORY GOES LIVE

… VERY SOON

source may be absent.

“Blockchain technologies to monitor material flows is also something being touted as a way to ensure that metals are tracked throughout the supply chain. Currently knowing where metals come from is difficult since for most metals, all the supplies become homogenized at a refinery (say in China), where it then becomes difficult to provenance specific supply.”

Diversity of supply is essential to ensure there is no total reliance on one source, he says. A range of sources means each can be objectively assessed for its pros and cons, be it the kind of labour used to produce it or environmental considerations such as the ability to minimize energy and water use and work towards a zero waste scenario.

The main concern for cell plants will be a secure supply of sustainable battery minerals, says Caspar Rawles, head of price assessments with Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

“At the moment we are seeing key players in the battery supply chain lock up raw materials in long-term supply contracts, and as more and more of these contracts are signed it leaves little for companies that are yet to act,” he says.

“At Benchmark we are predicting deficits in critical battery mineral markets including lithium, cobalt, nickel and graphite at various stages between now and 2030. In the case of lithium and cobalt we expect these markets to fall into deficit before 2025 — cell and automakers will need to act now to secure the battery minerals they will need.” The first European home-grown gigafactory is set to come into operation by the end of 2021. Built by Northvolt, a Swedish company founded by two ex-Tesla executives in 2015 and initially called SGF Energy, the factory is located in Skelleftea, in the far north of Sweden some 125 miles south of the Arctic Circle.

The plans for the gigafactory are ambitious to say the least. It hopes to provide a quarter of the lithium batteries that will power Europe’s EVs in the future. Part of its business plan is predicated on the enormous surge in demand for EVs expected to happen once sales of ICE powered vehicles stops

The car firms themselves say they are leading the charge.

Honda for example, says that it will only sell electrified vehicles — ie they will be pure electric or hybrid — by 2022. Ford and Volvo, for example, says their entire range of passenger vehicles will be fully electric in Europe by 2030. BMW reckons around half will be by that date.

Some brands such as Jaguar will be pure electric by 2025, Opel by 2028. UBS, the international investment bank, recently predicted that some 40% of all new cars sold in 2030 will be battery electric.

“Many automotive companies, for example, think that our forecast that electric vehicles will have a 40% share of global new car sales by 2030 is too high,” says the authors of a recent report. “If anything, we think it could be too low. And the financial community is starting to realize what is happening. Pure play electric car companies are valued much higher than any of the legacy car companies, despite producing only a small fraction of their volumes.” As evidence of this, it’s worth looking at the market capitalization of Tesla which has as stock valuation larger than the next 10 car manufacturers combined. “If you look at the agenda for all the automotive manufacturers to make those electric cars, the amount of cells that you’ll need to access, is going to be huge,” says a Northvolt official.

In its first phase of development Northvolt aims to make enough batteries to power almost 300,000 electric vehicles a year, but with the potential to raise that figure to 1 million.

The company has already a $14bn order from Volkswagen to produce its batteries for the next decade. VW also has a 20% stake in Northvolt. BMW has signed a deal for €2 billion ($2.3 billion) to receive batteries from 2024. Talk about a joint venture between Northvolt and Voltswagen based near VW’s pant in Salzgitter in Germany appears to have stalled with a Chinese firm called Gotion High-Tech taking Northvolt’s place. Some media sources say Northvolt is now seeking its own site in Germany.

Northvolt has secured huge sums of investment over the years from large investment funds, automobile companies and European Union institutions. It most recently attracted $2.75 billion in a private placement.

Including this new funding, Northvolt has raised over $6.5 billion to expand up to 150GWh of annual production capacity in Europe by 2030.

BNEF research says electric vehicles represent a possible $7 trillion global market by 2030. Lithiumion battery demand from EVs is set to rise from today’s 269GWh to 2.6TWh per year by 2030 and 4.5TWh by 2035.