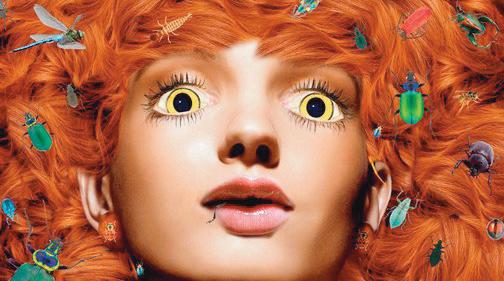

Human-Animal

Academic research is generally not envisaged as a collection of art works or an idea articulated with material culture, however, like the best academic inquiry, good exhibitions have strong, logical nar ratives, cultural relevance and in-depth research. They are ideal models for knowledge transfer. Work ing with researchers to conceptualise an exhibition pushes ambitious conversations across disciplines and departments.

RMIT Gallery’s exhibition program focuses on show casing the best of RMIT University research from both university staff and higher degree students. RMIT Gallery’s Senior Communications and Outreach Advisor Evelyn Tsitas has embraced this opportunity to build upon her PhD research into a meticulously researched exhibition of engaging art works that resonate with the main themes of her thesis.

To our delight the exhibition was resoundingly embraced by both the student cohort and the wider public. The opening night garnered large audiences supporting the gallery’s new programming. For stu dents, the gallery offers new impactful and enduring experiences, connections and pathways to learning in a welcoming environment.

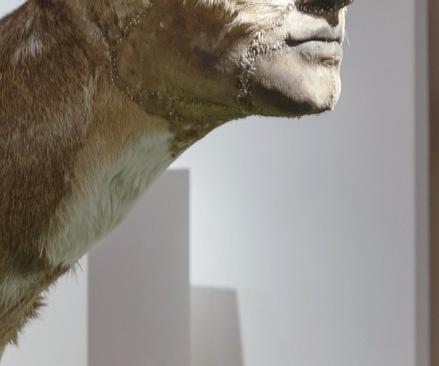

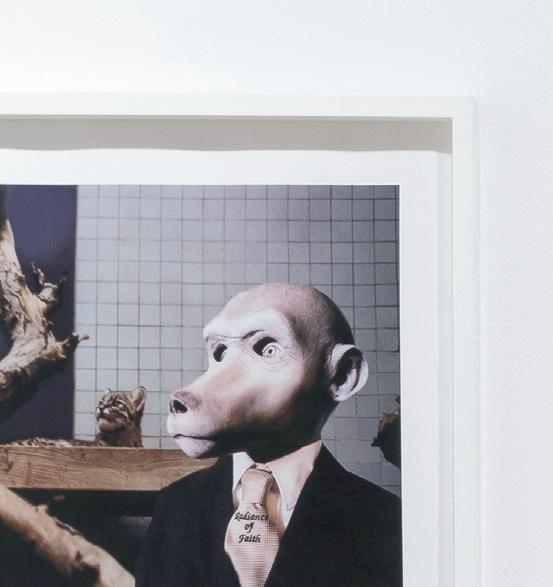

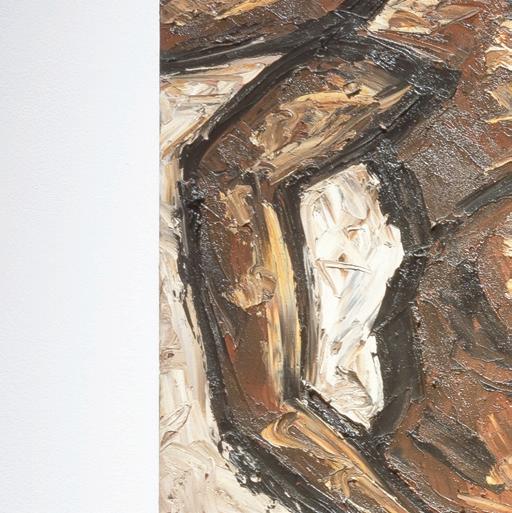

I would like to thank all the artists, both locally and internationally, who generously delved into their studio or archives to source the right work or devel oped a new work for the exhibition. Many artists contributed to our diverse public program of stand ing-room only artist talks. A selection of edited transcripts from these events are reproduced in this catalogue. I thank the artists for taking the time and sharing their love of this engaging topic. New York based taxidermy artist Kate Clark travelled to Mel bourne to speak alongside Julia deVille and attend the opening. Kate’s impressive work Gallant, a fusion

of human and deer, spoke beautifully to the notion of the hybrid fiction and stopped us in our tracks as we entered the gallery each day. Having her on site was a joy – she shared her experience and wealth of knowledge with us all.

Sincere thanks also go to the institutions and private collectors who kindly shared major works of art with us including: The Art Gallery of Ballarat, Latrobe Uni versity Art Collection, MONA, Heide MOMA and Royal Australia & New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. At RMIT University we would like to thank Deputy Vice-Chancellor Research and Innova tion and Vice President Professor Calum Drummond and Jane Holt, Executive Director Research and Innovation for their support and trust that enables RMIT Gallery to showcase the best of RMIT Univer sity research; as well as Professor Paul Gough, Pro Vice Chancellor and Vice President for his encour agement and enthusiasm hosting our opening night event along with guest speaker Professor Barbara Creed, whose insightful remarks located the exhibi tion historically, culturally and politically.

Finally I would like to thank Evelyn Tsitas, whose commitment to the broader impact of her research made this exhibition possible. The very long hours she worked to transform a creative writing thesis into the practicalities of a visual art exhibition was appre ciated. I wish to congratulate all the staff of RMIT Gallery; Nick Devlin, Jon Buckingham, Mamie Bishop, Meg Taylor, Maria Stolnik, Valerie Sim and Vidhi Vidhi who worked supportively and collaboratively to assist the complex production of this exhibition.

Helen Rayment Acting Director RMIT Gallery

I am delighted to open this wonderful exhibition My Monster: The human-animal hybrid curated by Evelyn Tsitas whom I first met at the Minding Animals conference in Utrecht, 2012.

I mention this conference by way of an introduction to My Monster. The Minding Animals Conference, held bi-annually, is one of the largest and most thought-provoking conferences I can recall attending. The conference runs over four days with sessions running from early in the morning until late in the evening. Presenting speakers came from across all disciplines, such as: humanities, science, philosophy, medicine, literature, art history, cultural studies and film.

The Nobel Laureate J.M. Coetzee opened the conference by reading from his manuscript that features his alter ego, Elizabeth Costello, a controversial academic who gives defends animals, arguing that, like us, they are sentient beings who have the right to live out their lives freely and free from cruelty.

Contemporary human-animal studies (HAS) which inspired the Minding Animals conference has inspired this exhibition. HAS subjects are now taught at many major Western universities. The Animals and Society Institute (ASI), a scholarly organisation whose aim is to expand knowledge in the field of human-animal studies, lists on its website that over 160 universities in North America offer courses in animal studies with over 22 dedicated HAS postgraduate programs.

While some humanities and social-science courses

Summoning the Muse, (detail) 2004, stoneware, glaze, Perspex, 67 x 70 x13cm, courtesy of the artist.

in Australian universities teach HAS subjects, the tertiary sector has been comparatively slow in responding to this field of research, despite the fact that Australians committed to the goals of animal liberation have played a leading role in the establishment of the area world-wide. These include the philosopher Peter Singer, author of the still-controversial and iconic book Animal Liberation (1975) and Christine Townend who founded Animal Liberation (1976) an animal rights organisation based in Sydney. Despite the lull in academic programs, Australian activists, authors, artists, filmmakers and scholars, alongside their overseas counterparts, play a key part in the global movement through publishing, research and community outreach as well as artistic practice and the organisation of conferences, seminars, and reading groups. RMIT Gallery is to be congratulated for contributing such a forward-thinking exhibition such as My Monster to the field.

The curatorial statement for My Monster states “the desire to merge human and animal into one creature has fascinated artists for 40,000 years, with the hybrid constantly updated and reinvented from century to century, from Greek classical myths and European folktales through to popular culture.” The aim of the exhibition is “to explore our complex relationship with ourselves, other species and the environment.”

A major reason for our fascination with the human-animal hybrid over the centuries is that we do not believe what mainstream institutions and academic discourses such as philosophy, science and religion

have been telling us about ourselves over the years, that is, that we humans are an exceptional or special species, more developed and of greater importance that all other species. Philosophers, religious schol ars and scientists have gone to great lengths over the centuries to emphasise our difference from other animals. They have argued throughout human history (not species history) that we are superior to all other species because we are more intelligent, we possess a soul, we show empathy, we are altruistic, we have speech and we experience emotions. The Enlight enment rationalist philosopher René Descartes asserted that what separates humans from animals is that animals do not feel emotions. He argued that if you hurt an animal and it yelps in pain, this was simply a reflexive response, just as if you hit a piano keyboard it will emit sound. Today, Descartes’ theory is difficult to accept but it was used by scientists for centuries to operate on animals without sedation or anaesthetic.

Today, philosophers such as Jacques Derrida, Kelly Oliver, Cary Wolf, Lori Gruen and Peter Singer are working to dispel these myths of human superiority and the supposed lack of animal sentience. It is rem nants of these beliefs that animals feel no pain and lack sentience that has contributed to society’s cur rent treatment of animals. Human superiority allows us to excuse our harsh treatment of animals, even if this involves animal suffering in scientific labora tories, factory farms or the live animal export trade.

Human-animal studies confronts one the most profound issues of our time, also a theme of this exhibition, the coming of the Anthropocene. For the first time, we are experiencing a human-made geological age distinguished by climate change, the mass extinction of species, and the loss of both animal and human habitat. Human-animal studies explores the Anthropocene along with anthropocen trism, that is, an approach to life that always puts the human first. Human-animal studies also explores the rights of non-human animals and the future of ethical thinking. Artists, writers and film makers also explore these and related issues in works that are

experimental and challenging - they are not afraid to speak out about the crisis of the animal.

My Monster explores a key question in human-ani mal studies; what does it mean to be human in the 21st Century? There is now an increasing body of sci entific evidence that challenges the traditional view that the human subject is an exceptional being whose intelligence sets it apart from all other species. Even Charles Darwin challenged human exceptionalism which earned him the ire of many influential people and institutions, such as the Church.

Scientific research today is demonstrating that both human and non-human animals share the character istics of sentience, intelligence, empathy and altruism. When living in their own communities, non-human animals communicate with each other, live according to social rules, raise their young, express emotions, show empathy and even altruism. The more we learn, the more we realise that we are also a species of animal, different, but ultimately an animal.

Despite the overwhelming evidence pertaining to animal sentience, they remain objects of human exploitation. Governments of many countries have passed legislation recognising animal sentience, however, they must now accept that measures need to be taken to attend to their welfare. The most recent tragedy, concerning the live export trade of animals from Australia in which over 3,000 sheep suffered from heat exhaustion and perished in their own waste, we need such legislation more than ever. The majority of animals on earth (as with modern human slaves) remain commodities of exchange, exploited commercially for human benefit, denied the right to live out their lives according to their nat ural needs and desires.

This state of affairs exists because of the way in which human beings are able to live, in fact, thrive in states of contradiction. One of the major contradic tions of the human condition is that we deny our own animality. This is the central theme of My Monster; the artists in this exhibition all set out to explore the

human-animal divide. Their works explore this issue from the perspective of the animal and the human. The various artists do not adopt an anthropocentric, or human-centred, point of view as so often happens when artists, such as Damien Hirst, use animal in their works to pose questions of the human condition.

The artists have used a range of techniques to explore the human-animal hybrid: painting, pho tography, film, taxidermy, biotechnology, and multi-sensory sound installations. Their works are exciting, thoughtful, challenging, sometimes abject and sometimes beautiful.

This exhibition, a tribute to Evelyn Tsitas’ power ful vision, explores the contradiction inherent in calling ourselves ‘human’ through its focus on the human-animal hybrid. My Monster argues that we are also animals and as such we need to take respon sibility for the plight of all other creatures, our kin, as well as the planet herself.

Creed is the author of five books on feminism, sexuality, film and media including the feminist classic The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis (1993).

Her recent research is on animal studies, the inhuman and social justice issues; and her latest publication Stray: Human–Animal Ethics in the Anthropocene (2017) explores the relationship between human and animal in the context of the stray.

Barbara Creed is a Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor at the University of Melbourne and an Honorary Professorial Fellow.One of the oldest-known examples of figurative art was created about 40,000 years ago in the shape of a hybrid. The Löwenmensch figurine, or Lion-man, fuses human and animal elements. It was discovered in a German cave in 1939, and is the first known example of humanity’s endless fantasy of the animal and human fused into one being. The hybrid form is repeated throughout mythology, folklore, figurative art, fiction, comics, cinema and computer games.

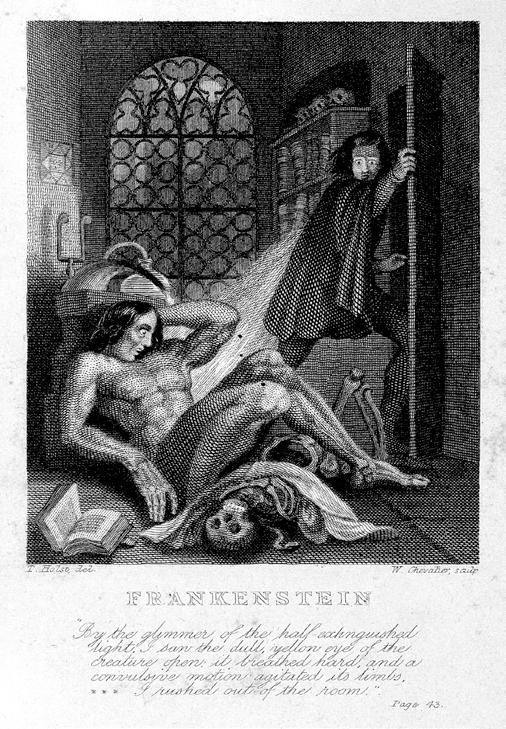

Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein is the first science fiction novel in which the human-animal hybrid appears. This is a cautionary tale about science without moral or social responsibility, heralding in the now well recognised portrayal of the mad scientist.

From the Lion Man to Dr. Frankenstein’s creature, the hybrid being imagined by artists and writers forces us to acknowledge our connection to the non-human animal with whom we inhabit this world.

The original inspiration for my research is Greek mythology. I was strongly influenced by the amazing tales my Papouli (Greek grandfather) told me, as well as the cautionary, Gothic stories of the Brothers Grimm, and the German classic children’s book Der Struwwelpeter, read to me endlessly by my Omi (Baltic German grandmother).

The deliberate use of specific Greek words for the different sections of the exhibition – xenos (foreigner, stranger); mythos (stories/tales/narrative); tokos (childbirth/reproduction); eros (erotic love); kosmos (the world/universe) - takes into account the chapters of my PhD research exploring the lifecycle of the human-animal hybrid in fiction.

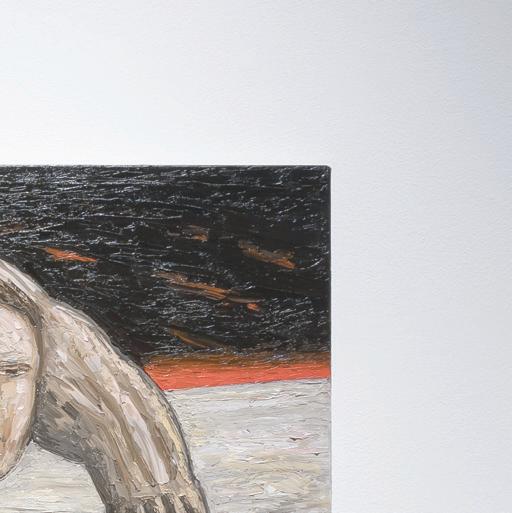

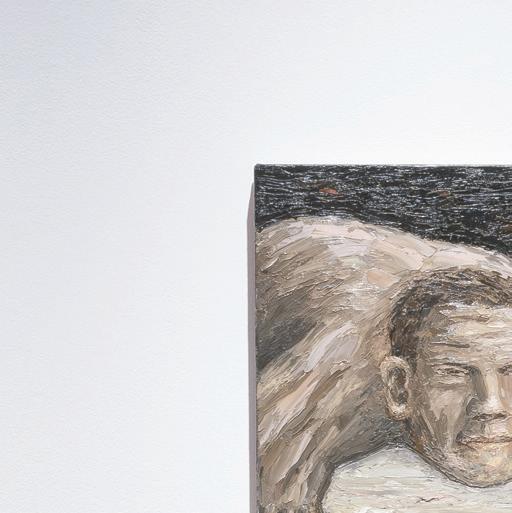

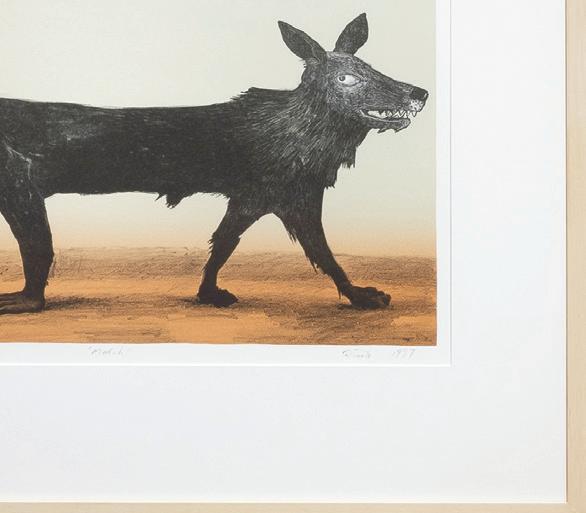

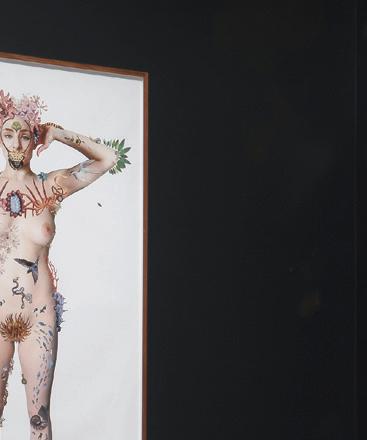

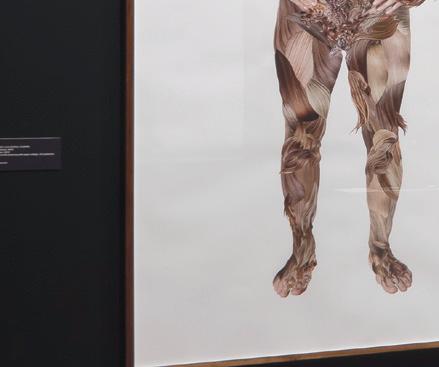

Dr Evelyn Tsitas Exhibition Curator RMIT GalleryGallant, 2016

Fallow deer hide, antlers, clay, foam, thread, pins, rubber eyes, wire 140 x 140 x 55 cm

Kate CLARK

Courtesy of the artist

Kate CLARK

Courtesy of the artist

The semi-human mythological creatures from Greek mythology, such as the Centaur (upper body of a human and the lower body of a horse); the Siren (half bird and half woman) and the Chimera (fire-breathing creatures composed of the parts of multiple animals) have been the subject of art and literature for centuries.

Mythological hybrid creatures can be understood as reflections of the uninhibited, strong and instinctual animal within us, as well as the socially responsible and repressed aspect of the human upon the natural world.

The hybrid is a creature that is constantly updated and reinvented across the centuries. With her combination of human and animal features, the frightening Medusa from Greek mythology is a Gorgon monster who can turn people into stone with a single glance. In the 20th Century, Medusa was adopted by many women as a symbol of female rage.

From Greek classical myths to European folktales and fairy tales; from stories of werewolves and vampires to superheroes with animal powers; the hybrid is alive and well and flourishes in literature, cinema, visual arts and popular culture.

The artists in this space use the hybrid as a varied and powerful metaphor. These works explore our complex relationship with maternity and domesticity; segregation and alienation; freedom and oppression; fractured relationships with the natural environment and other animals, as well as struggles with our public and private personas.

Hovering above the gallery, Indonesian artist Heri Dono’s angels (inspired by Flash Gordon comics) are a metaphor for freedom and dreams; but flying trapped in a cocoon, these hybrid creatures take on a social and political meaning as well.

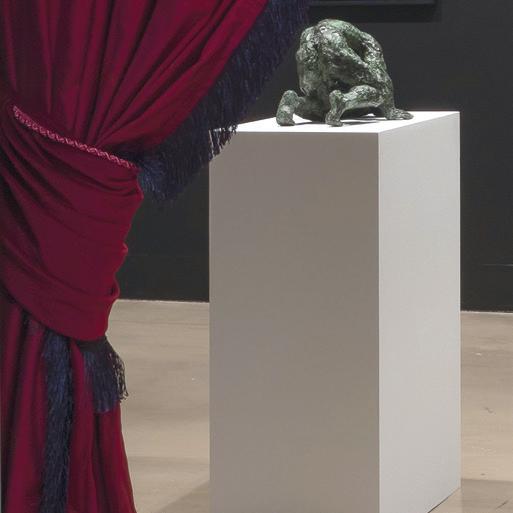

THIS PAGE: Geoffrey RICARDO

Untitled, 1993

Bronze sculpture

18 x 15 x 6 cm

Courtesy of the artist

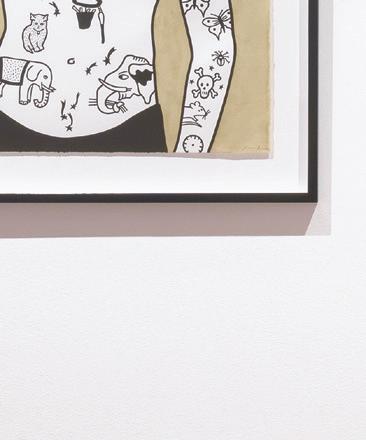

OPPOSITE: Eko NUGROHO

Trap Costume for President Z, 2011 Embroidered rayon thread on fabric backing 190 x 146 cm

Collection of Konfir Kabo, Melbourne

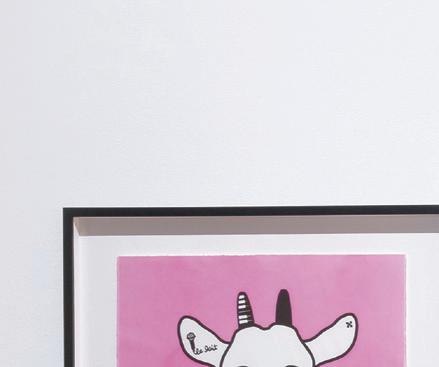

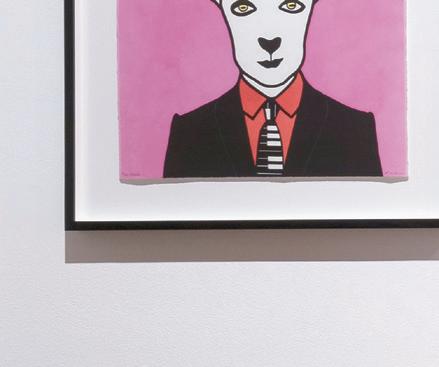

Pascal, 2017, The Surgeon, 2010, Dusty Rhodes, 2011, Dutch, 2009, hand coloured linocut prints, courtesy of the artist and Australian Galleries.

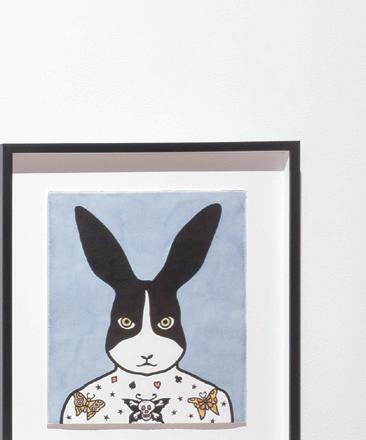

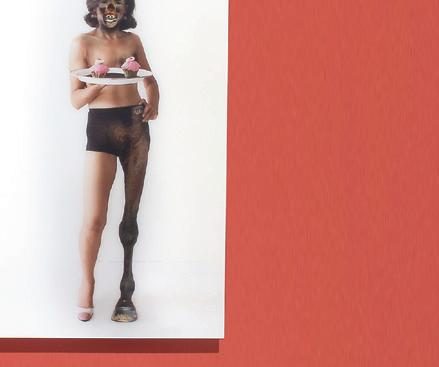

Madness, 2001, Self, 2001, Sculpt d. Dog, 2001, print on archival museum rag paper, 81 x 51 cm each, courtesy of the artist

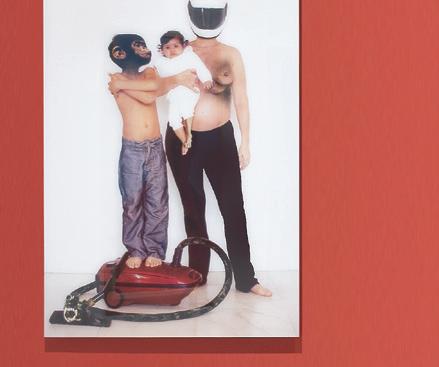

Family Portrait, 2004, Feather Duster, 2004, The Hunter and the Prophet, 2004, Chocolate Muffin, 2004, Angel, 2004, diasec prints, courtesy of the artist.

OPPOSITE: Jane

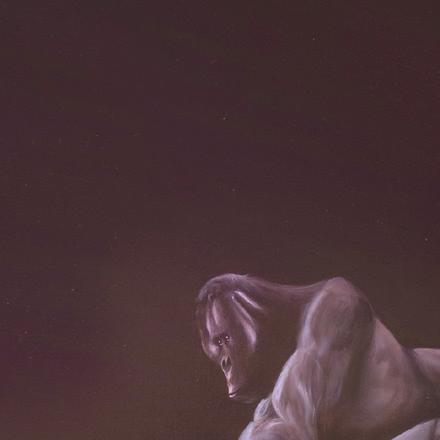

Post Conversion Syndrome (in captivity), 2003, Post Conversion Syndrome (in the wild), 2004, courtesy of the artist and gordonschachatcollection, South Africa.

BELOW: Peter BOOTH

Untitled, 2002 Bronze sculpture 15 x 14 x 16 cm high Courtesy of the artist and Chris Deutscher

ABOVE LEFT: Mermaid Bowl 2017 Stoneware, glaze, lustre 28 x 9 x19cm

Courtesy of the artist

ABOVE RIGHT: Reptile Woman, 2017 Stoneware, glaze, lustre 20 x 14 x 14cm

Courtesy of the artist

Cat Candelabra 2017 Stoneware, glaze, lustre 41 x 25 x17cm

Courtesy of the artist

Untitled, 1988, Untitled, 2008-2018, courtesy of the artist and Chris Deutscher Gallery.

Bigfoot, 1997, Match, 1997, Another Otherwise, 2014, Courtesy of the artist

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: Geoffrey RICARDO

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: Geoffrey RICARDO

BELOW L-R: Song, 2018, Promise, 2017, Harbinger with Rainbow, 2004, Landscape with transmitter, 2007, Missing, 2004, Post Conversion Syndrome (in captivity), 2003, Post Conversion Syndrome (in the wild), 2004, courtesy of the artist and gordonschachatcollection, South Africa.

Flying in Cocoons, 2001, fibreglass, acrylic, papier mâché, cast iron, gauze, chicken wire, bulb, metal string, mechanical and electrical devices, 210 x 110 x 110 cm each, Private Collection, Melbourne.

Charles Darwin’s revolutionary book On the Origin of Species (1859) introduced the theory that pop ulations evolve through natural selection through common descent. The unassailable belief that humans were unique and unrelated to other animals was shattered. There was also the fear that if man evolved from animals he could degenerate back to animal.

Humans and animals have never been known to reproduce naturally, despite many recorded inci dents of bestiality over the centuries. This has not stopped artists, scientists and writers from imagin ing that the merging of biological identities would result in improvements for both species.

In the early 20th Century, Soviet biologist Ilya Ivanov carried out experiments to create hybrid human-pri mates using artificial insemination techniques. He tried and failed to create human-ape hybrids insem inating female primates with human sperm. Later he devised an experiment to inseminate female volunteers with orang-utan sperm. However the orang-utan died before these procedures could be carried out.

In 2017, scientists from the Salk Institute (USA) announced that they had created hybrid human-pig foetuses. These contained human cells in multiple tissues, but were not allowed to develop to term. Despite these safeguards, public anxiety at crossing the species barrier remains high.

Slovenian artist Maja Smrekar developed her award-winning performance project K-9_topology in order to question current biotechnological possibil ities in reproduction. She lived in seclusion for three months with her dogs and manipulated her body to be able to breastfeed them. On another occasion, one of her emptied ova was used as a host for a somatic cell of her dog Ada. The resulting cell was not intended to become a hybrid.

In another hybrid fantasy, Japanese artist Ai Hase

gawa imagines that a woman could gestate and give birth to a baby from another species in her video work In I Wanna Deliver a Dolphin

Just as in Mary Shelley's time, there is still enormous debate and discussion about what technological ad vances and rapid changes in reproductive medicine mean for humanity, throwing into question the very essence of what we know to be ‘natural’. Franken stein’s creature was created, not born, and therefore treated as a commodity rather than an individual with a soul, free will and inherent rights. This is the same anxiety felt by many as we ponder the future of our species.

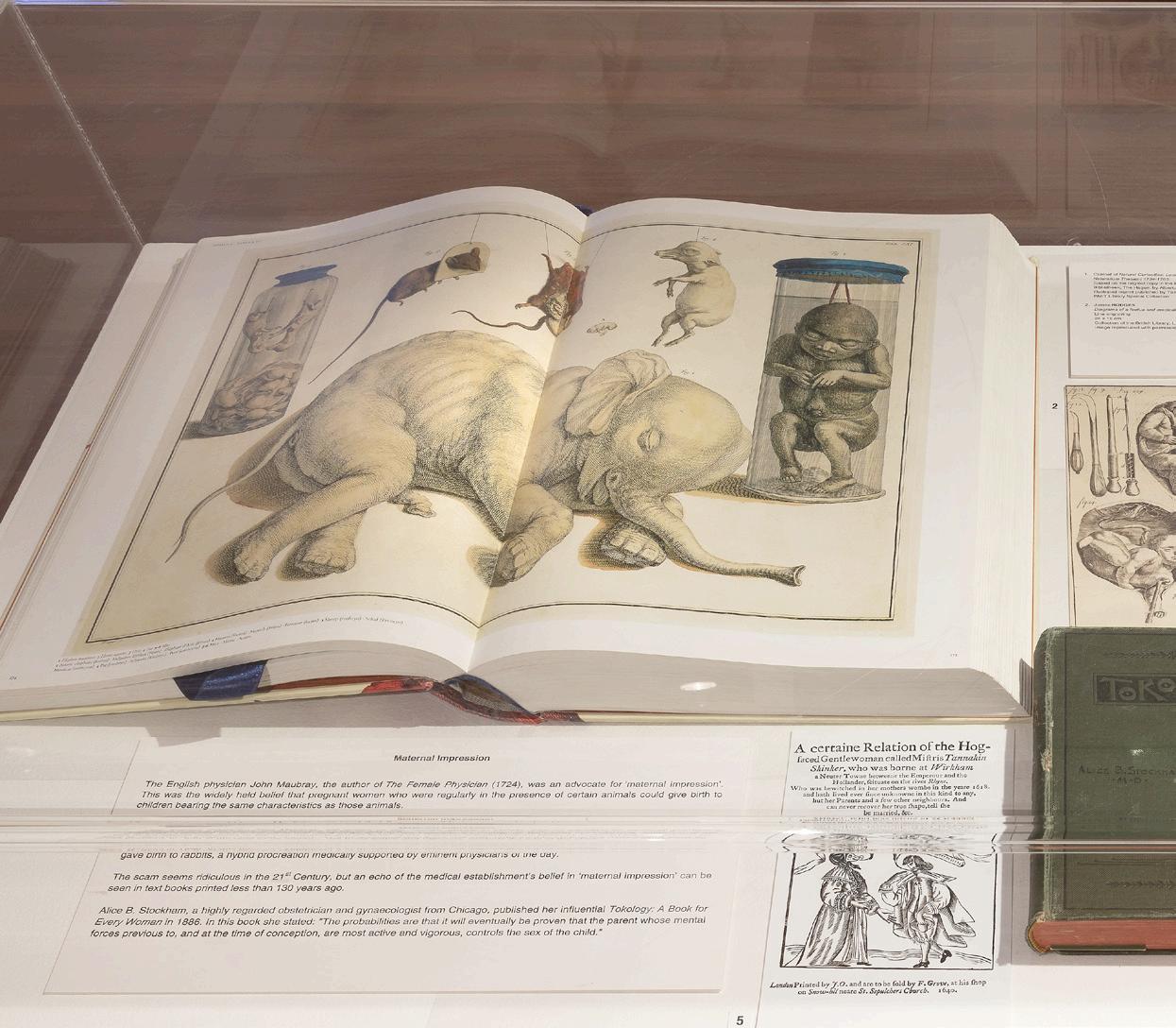

The English physician John Maubray, the author of The Female Physician (1724), was an advocate for ‘maternal impression’. This was the widely held belief that pregnant women who were regularly in the presence of certain animals could give birth to children bearing the same characteristics as those animals.

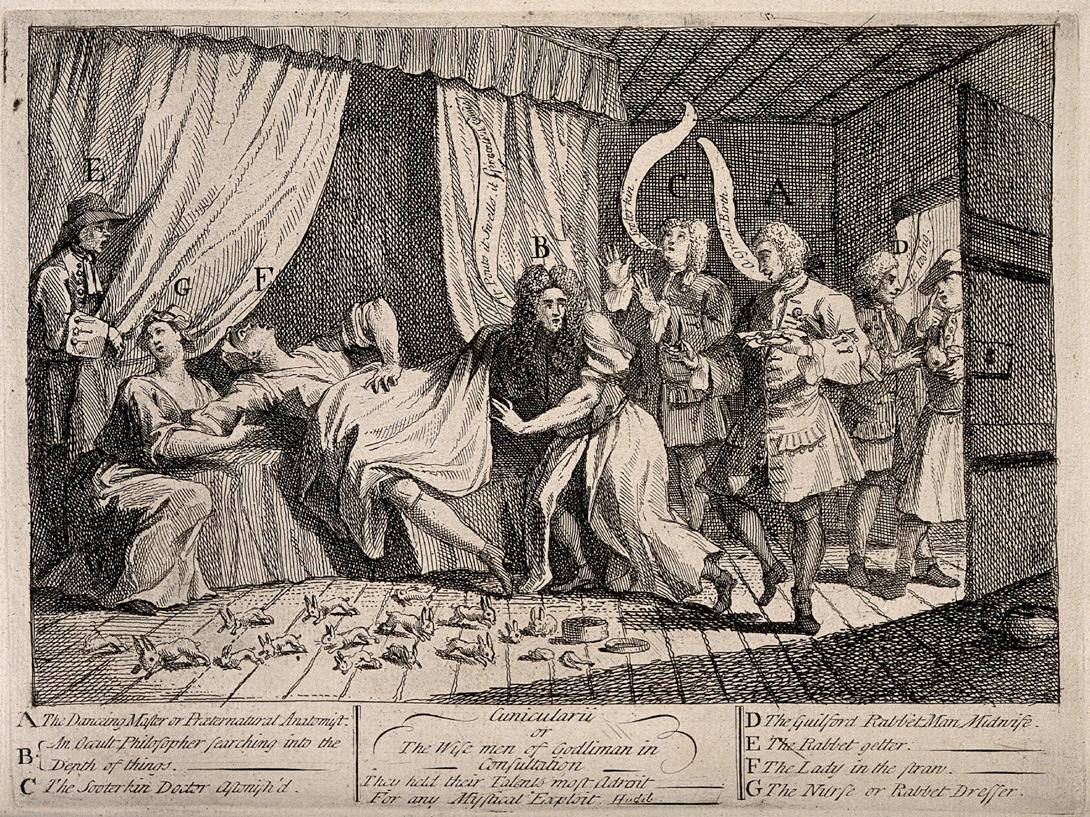

Like many doctors of his era, Maubray proposed that it was possible for women to give birth to sooterkins, small mouse-like creatures. Maubray was involved in the case of Mary Toft, who appeared to vindicate his theory. In 1726 Toft claimed that she gave birth to rabbits, a hybrid procreation medically supported by eminent physicians of the day.

The scam seems ridiculous in the 21st Century, but an echo of the medical establishment’s belief in ‘mater nal impression’ can be seen in text books printed less than 130 years ago.

Alice B. Stockham, a highly regarded obstetrician and gynaecologist from Chicago, published her in fluential Tokology: A Book for Every Woman in 1886. In this book she stated: "The probabilities are that it will eventually be proven that the parent whose mental forces previous to, and at the time of con ception, are most active and vigorous, controls the sex of the child."

I wanna deliver a dolphin, 2011-2013, digital video, duration: 02:39, courtesy of the artist.

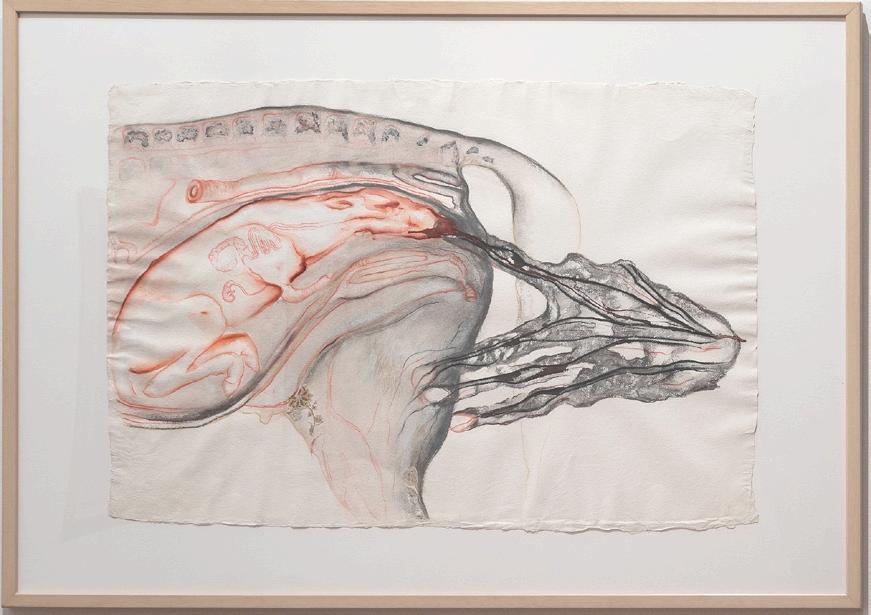

In our hands…Nothing (Egon and Me) 1, 2010, mixed media on handmade paper, 70 x 100 cm, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris and Brussels.

Maja SMREKAR with Manuel VASON

‘K-9_topology: Hybrid Family’, 2016 digital performance-based photography, courtesy of the artists

Maja SMREKAR with Manuel VASON

‘K-9_topology: Hybrid Family’, 2016 digital prints: performance-based photography, courtesy of the artists.

Top Row, L-R : Smellie’s Forceps, c.1750 obstetric forceps; iron, leather, metal sheet coating, Courtesy of RANZCOG, Melbourne

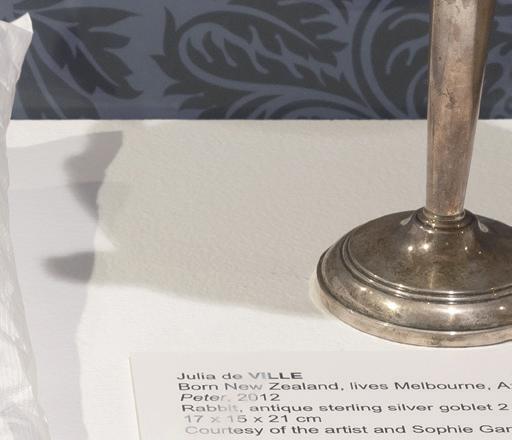

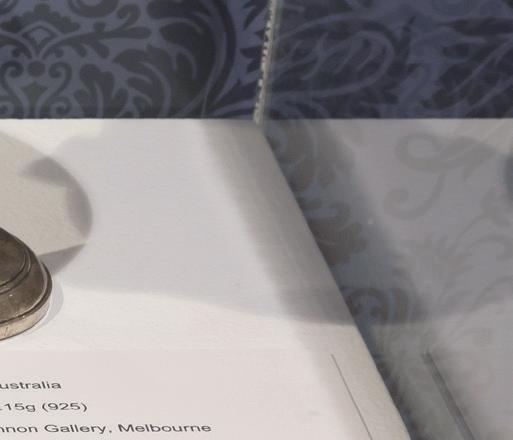

Julia DeVILLE Peter, 2012

Rabbit, antique sterling silver goblet 2.15g (925), 17 x 1 5 x 21 cm Courtesy of the artist and Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne

Bottom Row, L-R : William MADDOCKS

A portrait of Mary Tofts, date unknown, stipple engraving with watercolour, image reproduced courtesy of Wellcome Collection, UK

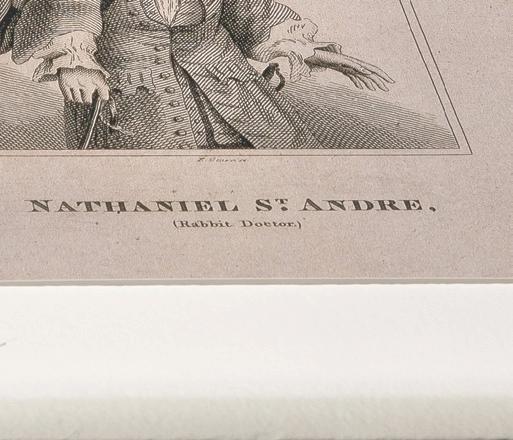

Portrait of Nathaniel St. André, date unknown, line engraving, Image reproduced courtesy of Wellcome Collection, UK

The strange case of Mary Toft

The obstetric forceps (c.1750) displayed alongside Julia deVille’s taxidermy rabbit sculpture Peter pays homage to the strange case of Mary Toft and her hybrid birth. This early example of ‘fake news’ has lived on in William Hogarth’s satirical engraving.

In 1726 Mary Toft, a peasant woman from a country town in England, convinced not just her local male midwife, but also King George I’s physician Nathaniel St André that she had given birth to rabbits...many, many rabbits.

Toft was taking advantage of the widespread belief held by the medical profession had that women were able to give birth to hybrid monsters because of their aberrant imaginations.

André examined Toft and not only was he convinced about the hybrid births, he claimed he helped with the delivery of a fifteenth rabbit. He went on to opportunistically publish A Short Narrative of an Extraordinary Delivery of Rabbet.

Shortly afterwards, Toft confessed to the event being a fraud when a thorough internal medical examination was demanded of her.

Looking at the Smellie forceps, it is easy to see why admitting the truth would seem preferable to submitting oneself to a medical obstetric investigation of that era.

Such was the anxiety about the medical profession that by the 1750s even the brilliant obstetrician William Smellie was accused of multiple murders of pregnant women in order to gain access to corpses.

By the time Frankenstein was published in 1818, the study of anatomy across Europe was so popular that viable cadavers were becoming rare and increasingly

valuable, meaning body snatching became a major problem.

It is no wonder that women have played a central role in animal advocacy since the 19th century when neither women nor animals had legal rights. Women felt that, just like animals, they were mistreated by the medical establishment. Women’s rights groups of that era, such as the Suffragettes, were at the forefront of moves to stop experimentation on live animals for medical research, known as vivisection.

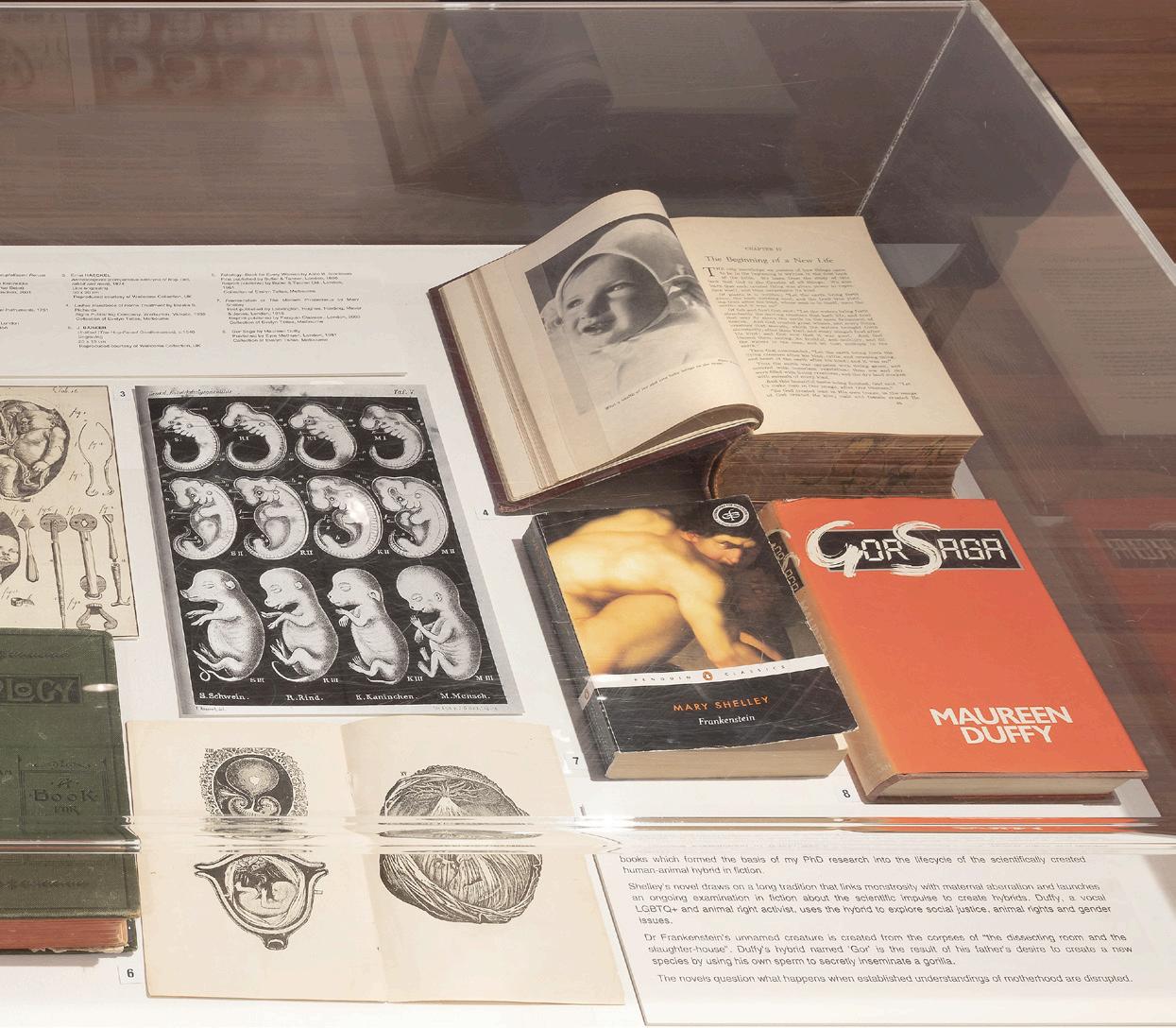

Frankenstein (1818) by Mary Shelley and Gor Saga (1981) by Maureen Duffy are the two influential books which formed the basis of my PhD research into the lifecycle of the scientifically created human-animal hybrid in fiction. Both speculative fiction novels explore the ethical consequences of what happens when the ‘natural’ boundaries of science and reproductive technology are pushed. The novels can be understood to question what happens when established understandings of motherhood are disrupted.

Dr Frankenstein’s unnamed creature was created from the corpses of ‘the dissecting room and the slaughter-house’. Duffy’s hybrid ‘Gor’ was the result his father’s desire to create a new species by using his sperm to secretly inseminate a Gorilla.

The authors give a voice to the hybrid creature cruelly cast aside by their creator, and pose the question of what makes us human, and what it is that distinguishes the hybrid from both humans and animals.

Shelley’s novel draws on a long tradition that links monstrosity with maternal aberration and launches an ongoing examination in fiction about the scientific impulse to create hybrids. In the 20th Century, Duffy, a vocal animal right activist, uses the hybrid Gor to explore social justice, animal rights and gender issues.

Mary tofts appearing to give birth to rabbits in the presence of several surgeons and man-midwives sent from London to examine her, 1726, etching, image reproduced courtesy of the Wellcome Collection, UK.

During the 1800s, when Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein, the distinction between scientist and artist was much more fluid. Shelley’s husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, experimented with electricity (once terrorising his sisters with his experiments). Mary was well aware of the scientific procedures of her time, such as Giovanni Aldini and Luigi Galvani’s experiments and theories on animal electricity. The artists in this space explore the interface of art and science, and art and technology in their examination of the human-animal, highlighting the importance of the creative arts in bioethical debates. Deborah Klein’s half-woman, half-insects are pinned down, resembling specimens in natural history collections. Kira O’Reilly and Jennifer Willet’s uncanny laboratory flips our expectations of animal experimentation.

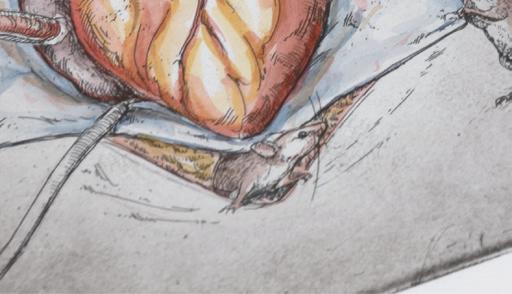

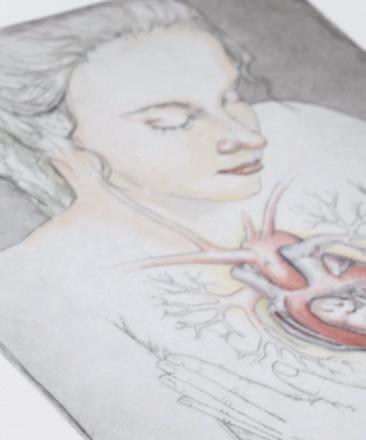

As we absorb the animal into us, via pig insulin, or pig valves and bovine cardiac tissue routinely used in heart surgery, where do we draw the line at ‘us’ and ‘them’? The transplantation of animal organs into humans (xenotransplantation) is on the horizon. The first genetically edited pig-to-human organ transplants could occur before 2020. Beth Croce’s modern fable is a symbolic narrative about animal sacrifice and medical progress.

ABOVE: Deborah KLEIN Ladybird Woman, 2014, watercolour, 41.9 x 29.7 cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

The Pig Prince; A Xenographic Tale, 2018, 11 sheets: intaglio print with hand coloured watercolour and letterpress, courtesy of the artist.

The Pig Prince; A Xenographic Tale (detail), 2018, 11 sheets: intaglio print with hand coloured watercolour and letterpress, courtesy of the artist.

Belly, 2011, silicone, fibreglass, human hair, 70 x 70 x 7 cm, Heide Museum of Modern Art, purchased with funds from the Truby and Florence Williams Charitable Trust, ANZ Trustees 2013

RIGHT: Deborah KLEIN

European Wasp Woman, 2015, Ladybird Woman, 2014, Actinus Imperialis Beetle Woman, 2014, all works: watercolour, courtesy of the artist.

Untitled, 2009, digital print in convex glass frame, courtesy of the artists

My Monster: the Human-Animal Hybrid, RMIT Gallery, Tokos gallery -‘Maternal Impression’ vitrine, installation image by Mark Ashkanasy.

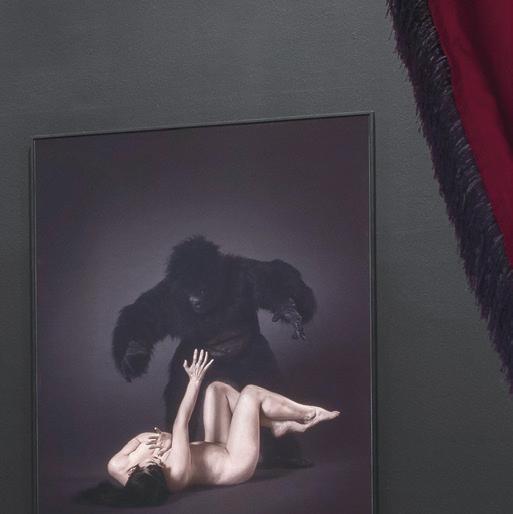

Humanzee pt. 2 from the series ‘When I laugh, he laughs with me’, 2014 Type-C photograph, edition 1 of 3 103.5 x 145 cm

Historically, human society has evolved in close proximity with animals. It is not surprising that our myths, folklore and the visual arts have embraced the erotic fantasies between human and animal in the form of the hybrid creature. This can be seen from representations of the well-endowed and insatiable satyrs of mythology to the sexually charged King Kong movies.

Humanity’s perceived uniqueness and dominance over the natural world was defined by its separation from the animal, and still lingers; witness our current obsession with body hair removal. This idea is powerfully challenged by Deborah Kelly’s hairy women, reminding us that depilation aside, we cannot deny our animal bodies.

Greek mythology is rich in bestial themes, such as Leda and the Swan, a story in which the god Zeus assumes the form of a swan in order to seduce Leda. This myth has been an inspiration for artists and poets for hundreds of years. For instance 'Leda and the swan’ was imagined by the 18th Century French artist Louis Garreau, after an earlier work by 17th Century Dutch artist Jan Verkolye. In My Monster the myth is explored by Sidney Nolan’s 20th Century depiction of the erotic scene, which is filled with energetic and implied sexual imagery.

Unknown artist (attributed to Nicola HICKS)

Minotaur, c. 20th century Bronze sculpture

24.5 x 40 x 24 cm

Collection of Jennifer Shaw, Melbourne

The offspring issuing from such mythical unions are hybrids, like the tortured Minotaur with the head of a bull and the body of a man, who was conceived by Queen Pasiphae and a white bull while she was under a curse from Poseidon.

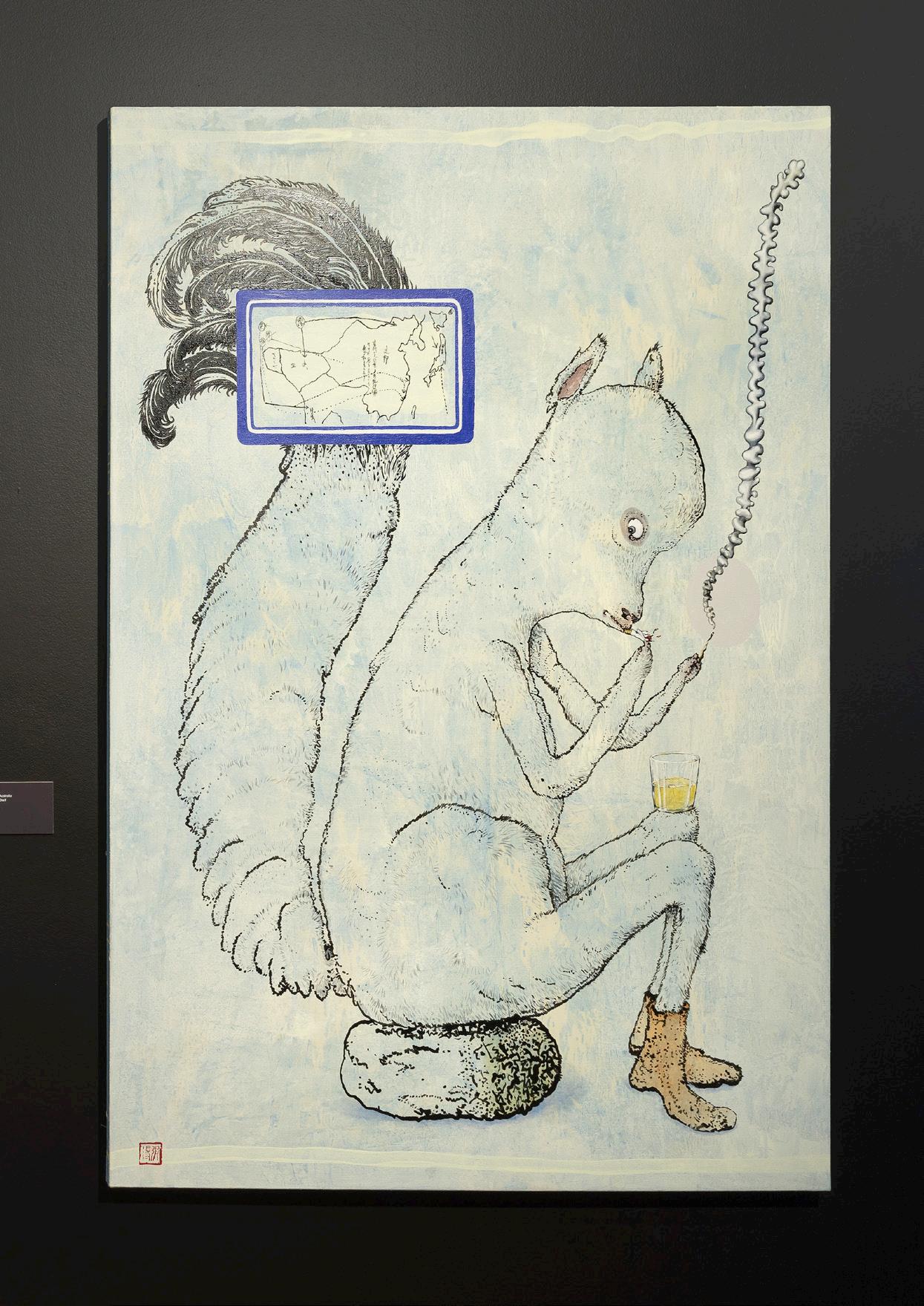

Animal sexuality is seen as forceful, driven by primal instinct and unhindered by human anxieties, and this is the lure of the hybrid creature in erotic fantasies. In the 17th century, the satyr legend came to be associated with stories of the orang-utan, a great ape now found only in Sumatra and Borneo. We see the echo of this bestial fantasy in Lisa Roet’s highly sexualised imagery of the woman and ape. Sam Leach’s eroticised portrayal of animal dominance forces us to confront the historical idea of viewing humans as superior to animals. His ongoing investigation of the relationship between humans and animals is informed by art history, science, and philosophy.

What is confronting about the work by Oleg Kulik is the reversal of consent, and how it forces the viewer to ponder our own animal nature. Are we more upset by the notion of an animal taking charge sexually of a human, or vice versa – and why? , a human, or vice versa – and why?

Afternoon of a Faun, c.1920; Desire, 1919, etchings, Private Collection, Sydney.

Sidney NOLAN Leda and Swan, 1960, synthetic polymer paint on composition board, 121 x 121 cm, Art Gallery of Ballarat: The William, Rene and Blair Ritchie Collection, Bequest of Blair Ritchie, 1998 : 1998.19;

Faun and Nymph, 1924, bronze, 26.5 x 29 x 13 cm, Private Collection, Sydney

Sidney NOLAN Leda and Swan, 1960, synthetic polymer paint on composition board, 121 x 121 cm, Art Gallery of Ballarat: The William, Rene and Blair Ritchie Collection, Bequest of Blair Ritchie, 1998 : 1998.19;

Faun and Nymph, 1924, bronze, 26.5 x 29 x 13 cm, Private Collection, Sydney

Deborah KELLY Venus of Beeness, 2017, Mervenus, 2017, silk banners, courtesy of the artist

Deborah KELLY Venus of Beeness, 2017, Mervenus, 2017, silk banners, courtesy of the artist

Family of the Future, 9, 1997, digital print: performance based photography, 136 x 150 x 5 cm, Collection of the Museum of Old and New Art, Tasmania

My Monster: the Human-Animal Hybrid, RMIT Gallery, Mythos gallery, installation image by Mark Ashkanasy.

My Monster: the Human-Animal Hybrid, RMIT Gallery, Mythos gallery, installation image by Mark Ashkanasy.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein launched a new strand of Gothic horror genre that established the human body as the site of power and control. These concerns are explored in cinema’s preoccupation with both the mad scientist and the transformed human, whose mutating human-animal body pushes the boundaries of nature.

Cinema has also embraced mythical hybrid creatures which owe their metamorphoses to a curse or mutation, such as the werewolf, vampire, mermaids or cat people. We invite you to linger in the hybrid narrative, and watch the movie trailer showreel.

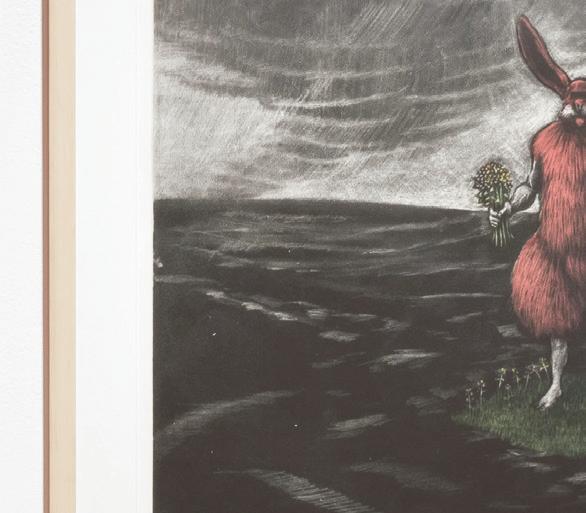

Stories of werewolves continue to resonate as they represent both human and something profoundly other that operates on impulse and instinct. Jazmina Cininas’ exploration of the female werewolf throughout history provides us with powerful narratives of aberrant femininity in the form of the hybrid creature.

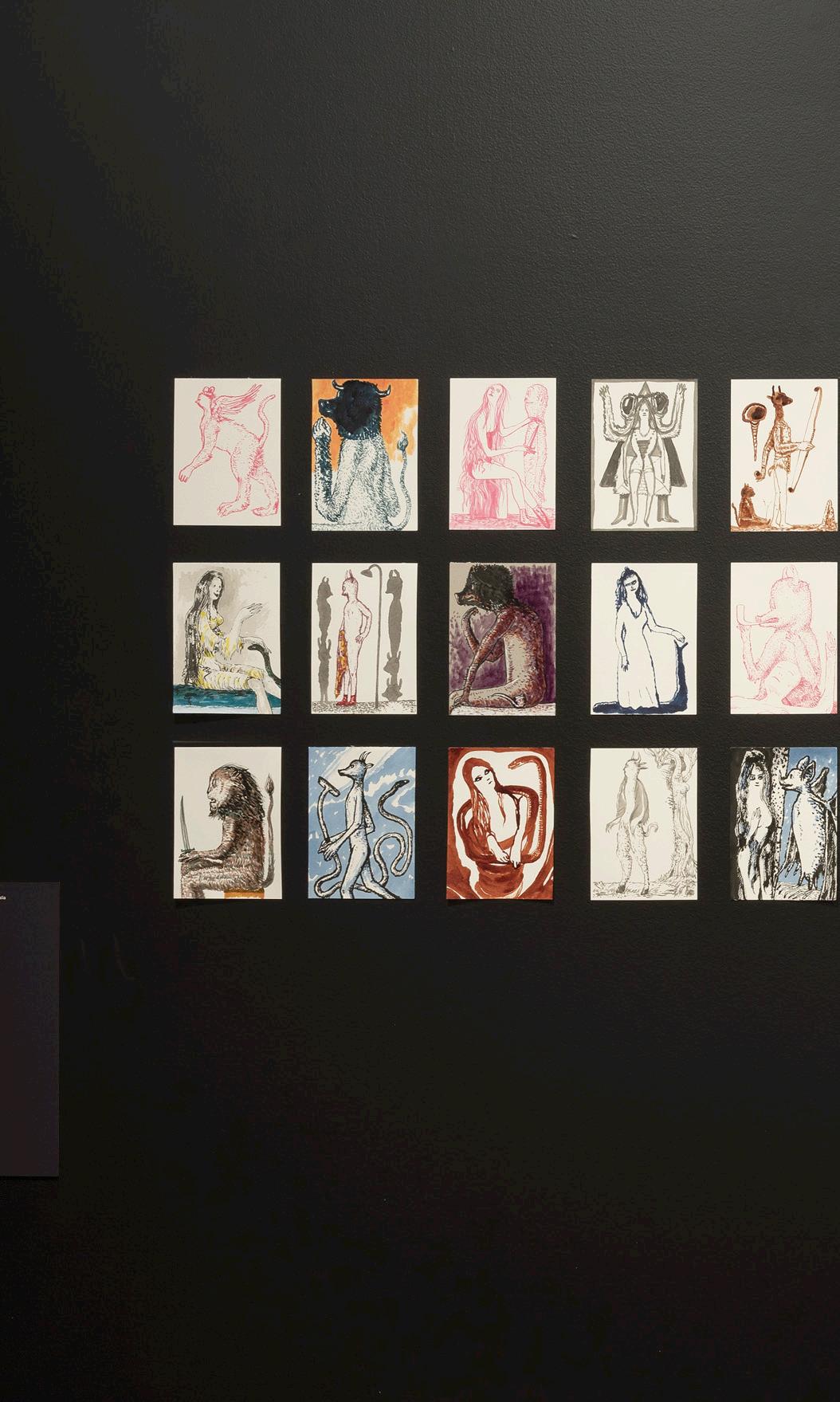

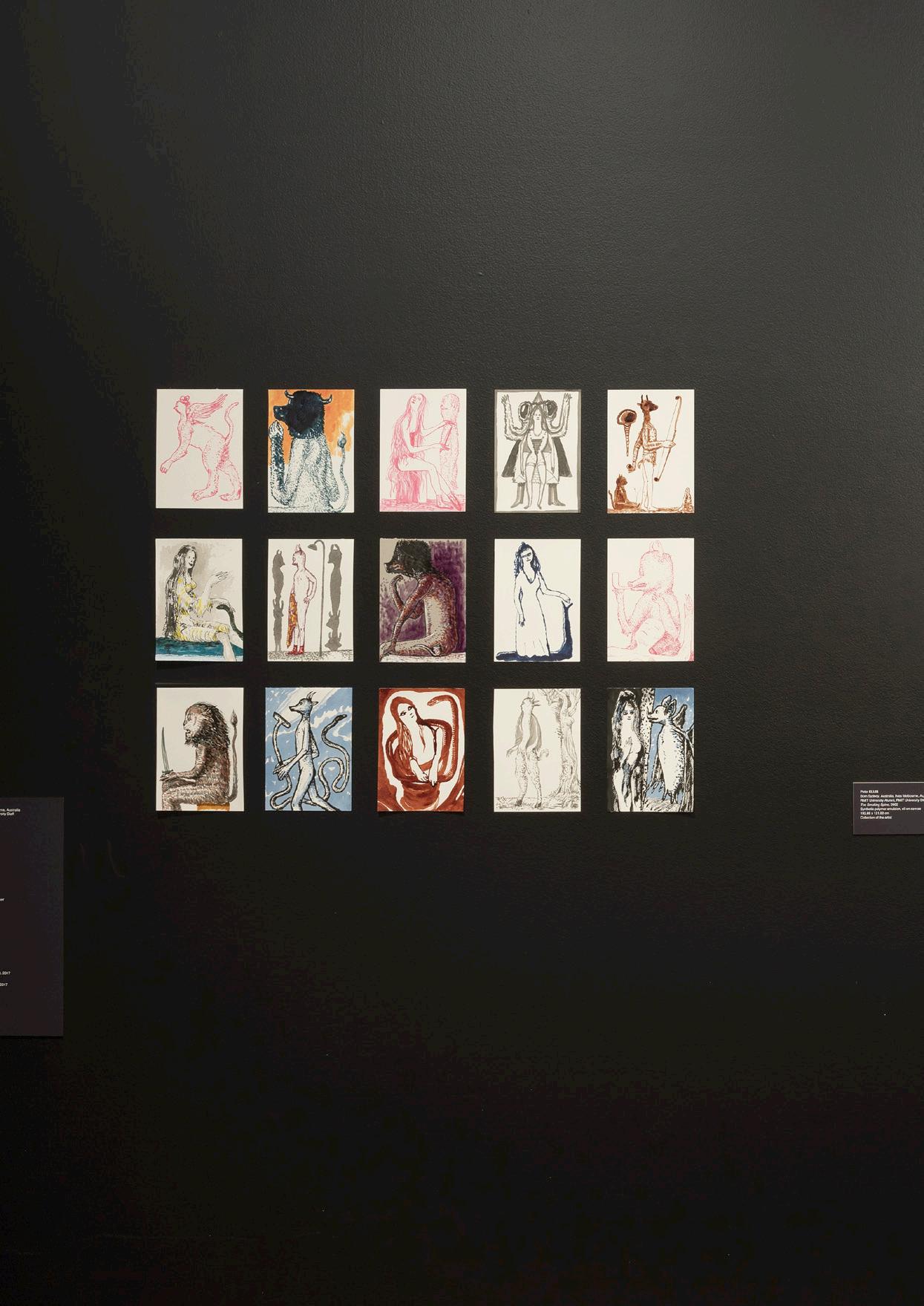

Peter Ellis builds on the Surrealist tradition of tapping into the subconscious mind; his hybrids appear to exist simultaneously in the human world, the fantasy dreamscape and the animal existence.

Birds feature in many hybrid stories, perhaps expressing the human desire to fly. Angels, found in religions and mythologies, are believed to guide and protect humans, while the Harpy and Siren of Greek mythology are dangerous creatures.

In the enduring Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus, father and son tried to escape their island home by making wings, but Icarus flew too close to the sun, and his wings melted.

Let your imagination take flight in The Rapture/ Fur Can’t Fly. Created by Melbourne’s iconic provocateur Moira Finucane with digital artist and symphonic composer Shinjuku Thief, this hybrid multisensory installation allows participants to immerse themselves in a magical hybrid world of birds, angels, redemption, ascension, transformation and rapture.

‘I went to Oro Preto one day, in the mist, in a bus, around the winding mountains. And I saw a kite, flying high above the forest. And for the first time in my life I knew I could leave, I could walk into the steep misty streets, I could buy a kite, I could fly a kite, I could fly.

I asked people all around the world, what is art to them and why do they love it? And those that love it said, in dozens of languages, art is freedom, art is transporting, art doesn’t tell you how to arrive or when to arrive but it will take you nonetheless. So I decided art was a raptor, rapture, physically, spiritually, emotionally transporting you from one place to another.

I saw a hummingbird in the mountains, unexpectedly, when I was buying a ticket, hovering, flying backwards, its wings moving so fast I saw a jewelled blur. Then it disappeared, and I was left behind on the ground.

Angels, birds, showgirls, goddesses, gods; they can all fly, they can all ascend, they can all transcend. Everyone knows creatures of the fur can’t fly. Some can, but they are freaks. Yet we all dream of it as children, and those that continue to dream are saints, angels, maniacs, polymaths, visionaries and lunatics. But here in this room, in this chair, the fur can fly.’

Created by: Moira Finucane & Darrin Verhagen

Text & Voice: Moira Finucane Score: Shinkjuku Thief Hummingbird Diorama: Rose Agnew Vibration, Movement & Light: Darrin Verhagen & Thomas Dahlenburg System: Jay Curtis

The Rapture/Fur Can't Fly, 2018, sound, feathers, armchair, eyelid projection, vibration, motion code, duration: 00:04:48, courtesy of the artists and AkE Lab, RMIT University.

Artworks L-R: Chimera, 2017, Minotaur, 2017, Vacuum, 2018, Alien, 2017, Actaeon, 2017, Ghost, 2018, Shower, 2018, Cursed Changeling with Pipe, 2017, A Girl and Her Slug, 2017, Dreaming Monster, 2017, Lion with Sword, 2017, She Searched Him for the Cutlery (2), 2017, Woman with Snake, Christmas Eve, 2017, Young Faun in Forest, 2018, They Inhabit the Night, 2018, The Smoking Spine, 2002, Courtesy of the artist.

Arline

of Barioux, Auvergne 1588, 2008, Angela Prefers the Company of Wolves, 2005, Blood Sisters, 2016, Rahne Dreams of Saving the World, 2006, Lydia's Humanity is Mostly Prosthetic, 2009, White Fell's Eye Turned (Green), 2010, Courtesy of the artist. quaecae. Nequas delique acimpostiam abo. Et debitiuntior sunt.

of Barioux, Auvergne 1588, 2008, Angela Prefers the Company of Wolves, 2005, Blood Sisters, 2016, Rahne Dreams of Saving the World, 2006, Lydia's Humanity is Mostly Prosthetic, 2009, White Fell's Eye Turned (Green), 2010, Courtesy of the artist. quaecae. Nequas delique acimpostiam abo. Et debitiuntior sunt.

Movie trailer showreel compilation

Duration: 01:05:55

Concept, development & research: Evelyn Tsitas Research assistant: Megan Taylor

Editing: Karen McPherson

Producer: Timothy Arch

Additional images: courtesy of Wellcome Collection, UK

Victor Frankenstein, directed by Paul McGuigan (20th Century Fox, 2015), theatrical trailer

Chimera, directed by Maurice Haeems (Praxis Media Ventures, 2018), theatrical trailer

Splice, directed by Vincenzo Natali (Warner Bros. Pictures, 2009), theatrical trailer

Chimera, directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark (A&E Networks, 1991), theatrical trailer

Rise of the Planet of the Apes, directed by Rupert Wyatt (20th Century Fox, 2011), theatrical trailer Mary Shelley, directed by Haifaa al-Mansour (ICF Films, 2018), theatrical trailer

Tusk, directed by Kevin Smith (A24 Films, 2014), theatrical trailer

The Island of Dr. Moreau, directed by John Frankenheimer (New Line Cinema, 1996), theatrical trailer

The Frankenstein Chronicles, directed by Benjamin Ross (ITV Encore, 2015), theatrical trailer

The Fly, directed by David Cronenberg (20th Century Fox, 1986), theatrical trailer Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, directed by Kenneth Branagh (TriStar Pictures, 1994), theatrical trailer

The Island of the Lost Souls, directed by Eric Kenton (Paramount Pictures, 1932), theatrical trailer

First Born, directed by Philip Saville (British Broadcasting Company, 1988), Episode 1: 0:00 - 4:20

The Return of the Fly, directed by Edward Bernds (20th Century Fox, 1959), theatrical trailer Mansquito, directed by Tibor Takács (Syfy, 2005), theatrical trailer Frankenstein, directed by James Whale (Universal Pictures, 1931), theatrical trailer

The Fly, directed by Kurt Neumann (20th Century Fox, 1958), theatrical trailer Frankenstein, directed by Danny Boyle (originally presented at the National Theatre, London, 2012), promotional trailer

The Fly II, directed by Chris Walas (20th Century Fox, 1989), theatrical trailer

The Curse of the Fly, directed by Don Sharp (20th Century Fox, 1965), theatrical trailer

The Shape of Water, directed by Guillermo del Toro (Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2017), theatrical trailer Siren, created by Eric Wald and Dean White, (Freeform Original Productions, 2018), promotional trailer

HISSS, directed by Jennifer Lynch (Millennium Entertainment, 2010), theatrical trailer Cat People, directed by Paul Schraber (Universal Pictures, 1982), theatrical trailer Manimal, created by Glen Larson and Donald Boyle (20th Century Fox Television, 1983), promotional trailer

An American Werewolf in London, directed by John Landis (Universal Pictures, 1981), theatrical trailer Wolf, directed by Mike Nichols (Columbia Pictures, 1994), theatrical trailer Catwoman, directed by Pitof (Warner Bros. Pictures, 2004), theatrical trailer

When Animals Dream, directed by Jonas Alexander Arnby (Nordisk Film Distribution, 2015), theatrical trailer

Cat People, directed by Jacques Tourneur (RKO Radio Pictures Inc., 1942), theatrical trailer

Ginger Snaps, directed by John Fawcett (Motion International, 2000), theatrical trailer Nosferatu the Vampyre, directed by Werner Herzog (20th Century Fox, 1979), theatrical trailer Beauty and the Beast, directed by Bill Condon (Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 2017), theatrical trailer

Beauty and the Beast, created by Ron Koslow (CBS Television Distribution, 1984), opening credits, 00:00-- 01:44

Penelope, directed by Mark Palanksy (Momentum Pictures, 2006), theatrical trailer I Think I’m an Animal, director unknown (Blue Ant International, 2015), 0:00 – 1:15 Fursonas, directed by Dominic Rodriguez (Gravitas Ventures, 2016), promotional trailer Animal Imitators, directed by Justin Pemberton (Natural History New Zealand, 2003), 0:00 – 0:50

Theodor von HOLST

Frankenstein observing the first stirrings of his creature, engraving, date unknown. Published by W. Chevalier, 1831. Image courtesy of Wellcome Collection, UK

Artist unknown, The Peruvian harpy: a harpy with two tails, horns, fangs, winged ears, and long wavy hair, coloured etching, date unknown. Published by Ednauis et Rapilly, c.1700. Image courtesy of Wellcome Collection, UK

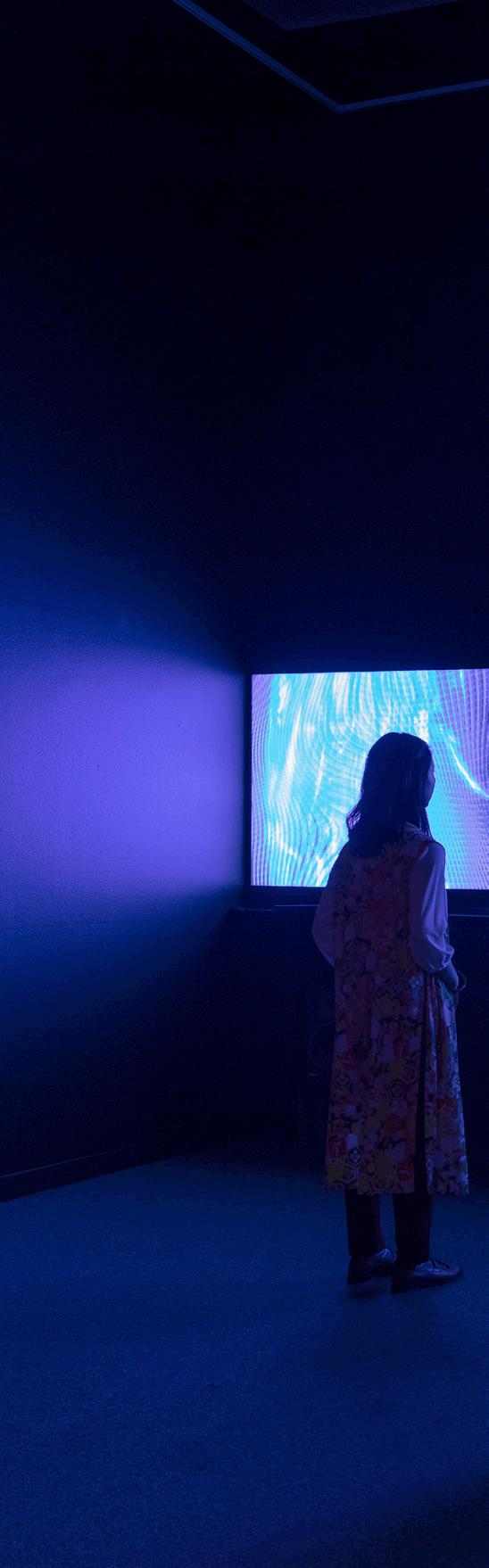

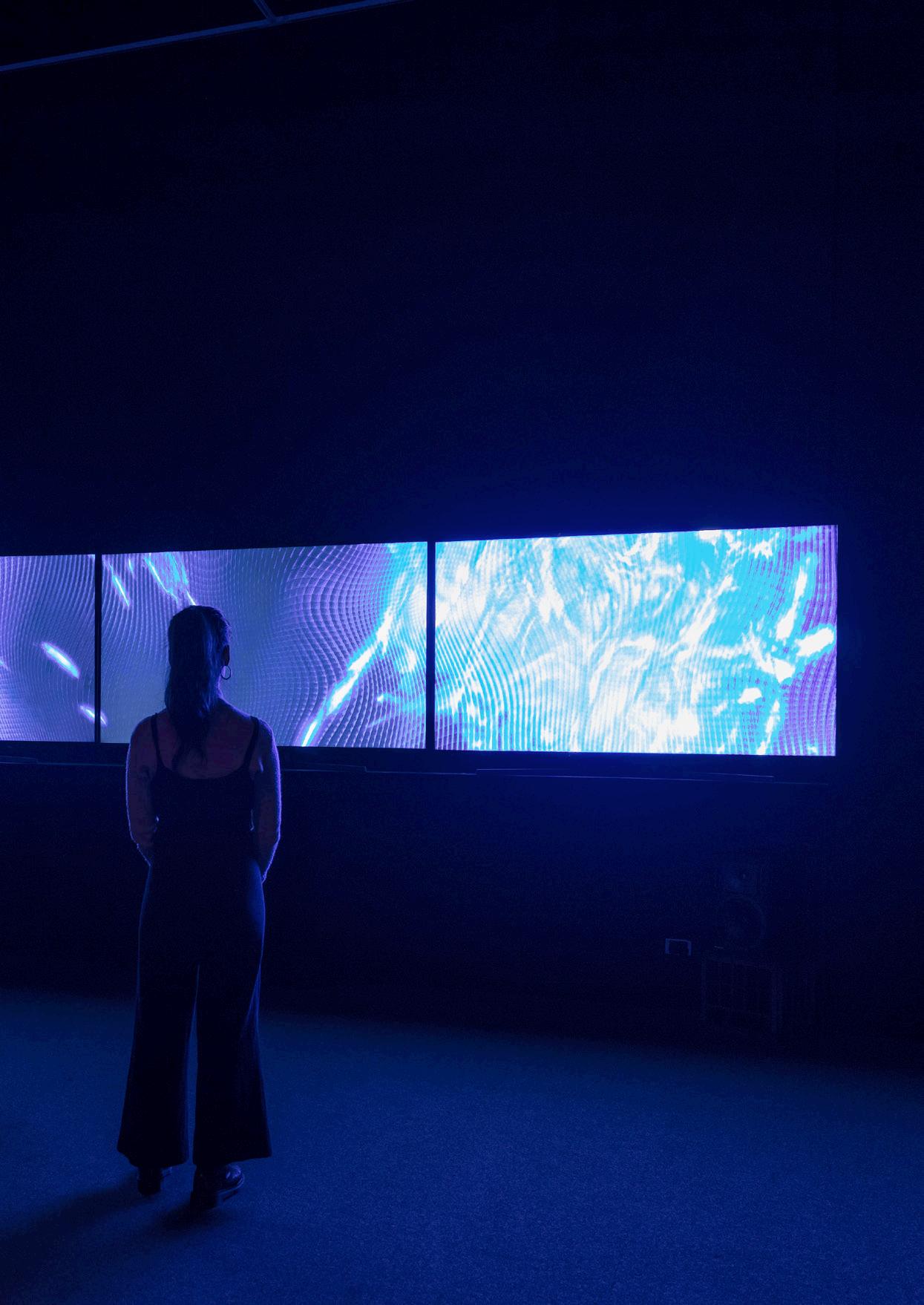

(((20hz))) and the Sensible World, three-channel digital video with audio soundtrack, duration: 00:03:17

Narration: Darrin Verhagen, Sound Design: Darrin Verhagen & James Paul, Image: Richard Grant, System: Thomas Dahlenburg & Nick Devlin

One of the main standards by which humans have asserted dominance and difference over non-hu man animals has been language. It is the failure to communicate across the species barrier that allows humans to justify exploitation of animals for food, clothing, labour, and even sexual gratification.

Frankenstein’s creature was somewhat unique in his articulate grasp of written and spoken language; even the hybrid in Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid had to sacrifice her tongue and voice to live on land with human legs.

Fiction generally provides us instead with examples of hybrids utilising animals’ sensory range, strength and endurance as a marker of difference with the human, such as werewolves and vampires.

Yet humans actually exist in a world in a limited capacity compared to many animals (let alone monsters), able to access different parts of the infor mation in the environment in which we inhabit. How can humans and animals speak the same lan guage when we don’t experience the same reality?

Inspired by the work of ethologist Jacob Von Uexküll, and more recently, neuroscientist David Eagleman, (((20hz))) enters My Monster with The Sensible World, an ode to the Umwelt (an organism’s subjec tive experience of its environment).

In this gallery space, audiences are invited in to a journey of the entire electromagnetic spectrum, briefly alighting on the narrow band of frequencies humans can detect as vision. By so doing, (((20hz))) identifies the monstrous scale of the maelstrom we are immersed in, yet ultimately oblivious to.

(((20hz))) and the Sensible World, three-channel digital video with audio soundtrack, duration: 00:03:17

Narration: Darrin Verhagen, Sound Design: Darrin Verhagen & James Paul, Image: Richard Grant, System: Thomas Dahlenburg & Nick Devlin

In a manner of speaking is an audio recording, score and vinyl lettering on glass by sound artist Catherine Clover. Her work is a speculative attempt at consid ering language across species in the urban context.

This score was constructed using attentive listening in central Melbourne, with a focus on considering common urban birds as language users. These are the birds we hear around us daily - such as ravens, wattlebirds, pigeons, silver gulls, rainbow lorikeets, willie wagtails, swallows, blackbirds, common mynas, noisy miners, spotted turtledoves, Australian mag pies, grey butcherbirds, pied currawongs, starlings, sparrows, and magpie-larks.

Like a textual echo of the sounds commonly heard in Melbourne, Clover’s work is focused on listening to the mix of bird and human voices in the city, as well as seeing and reading urban texts such as traffic signs, advertising, street names, business names and graffiti.

As part of the exhibition, RMIT Gallery hosted a par ticipatory performance for visitors to collaboratively perform Clover’s bird songs. There were no expec tations of skill or ability with this voicing. As Clover said, ‘It is not about virtuosity or accuracy, nor is it about deceiving the birds; it is about listening, impro visation and imagination. All are welcome!’

In a manner of speaking, 2017-2018, audio recording and vinyl lettering on glass, duration: 08:33, courtesy of the artist. Exhibition Entrance views.

J. BARKER

(((20hz))) and the Sensible World

Digital video with audio soundtrack Duration: 00:03:17

Narration: Darrin Verhagen Sound Design: Darrin Verhagen & James Paul Image: Richard Grant System: Thomas Dahlenburg & Nick Devlin

Rose AGNEW

Born Grahamstown, South Africa, lives Melbourne, Australia

Prayer at the Temple of Flora, 2018

Mixed media

30 x 25 x 48.8 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Jane ALEXANDER

Born and lives Johannesburg, South Africa Missing, 2004

Pigment print on cotton paper, AP3 from an edition of 12 45 x 60.5 cm

Harbinger with rainbow, 2004

Pigment print on cotton paper, AP3 from an edition of 12 45 x 54.5 cm

Post Conversion Syndrome (in the wild), 2004

Pigment print on cotton paper, AP3 from an edition of 12 45 x 66.5 cm

Post Conversion Syndrome (in captivity), 2003

Pigment print on cotton paper, AP3 from an edition of 12 45 x 65 cm

Landscape with transmitter, 2007

Pigment print on cotton paper, AP3 from an edition of 12 45 x 60.5 cm

gordonschachatcollection, South Africa Promise, 2017

Pigment print on cotton paper 14 x 12 cm

Song, 2018

Pigment print on cotton paper 7.55 x 10 cm

Courtesy of the artist and the South African National Research Foundation

Untitled (The Hog-Faced Gentlewoman), c.1640 Engraving 20 x 13 cm

Image reproduced courtesy of Wellcome Collection, UK

Janet BECKHOUSE

Born and lives Melbourne, Australia RMIT University Alumni Cat Candelabra 2017 Stoneware, glaze, lustre 41 x 25 x17cm

Mermaid Bowl 2017 Stoneware, glaze, lustre 28 x 9 x19cm

Reptile Woman, 2017 Stoneware, glaze, lustre 20 x 14 x 14cm

Summoning the Muse, c.2004 stoneware, glaze, perspex 67 x 70 x13cm

Courtesy of the artist

Peter BOOTH

Born Sheffield, United Kingdom, lives Melbourne, Australia Untitled, 1988 Oil on canvas 198 x 111 cm Untitled, 2008 - 2018 Oil on canvas 51 x 71.5 cm

Untitled, 2002 Bronze sculpture 15 x 14 x 16 cm high

Courtesy of the artist and Chris Deutscher

Jazmina CININAS

Born and lives Melbourne, Australia RMIT University Alumni Lydia's Humanity is Mostly Prosthetic, 2009 Linocut reduction 22 x 22.2 cm

Blood Sisters, 2016 Linocut reduction 69.5 x 56 cm

Rahne Dreams of Saving the World, 2006

Linocut reduction 54 x 56.5 cm

Angela Prefers the Company of Wolves, 2005

Linocut reduction 49.5 x 47 cm

White Fell's Eye Turned (Green), 2010 Linocut reduction 20 x 15 cm

Ann's Invisible Greyhound is Most Bewitching, 2017

Reduction linocut with second block and letterpress on Somerset White 300gsm 61.5 x 41 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Arline of Barioux, Auvergne 1588, 2008

Linocut on paper 65 x 48 cm (image), 76 x 56 cm (sheet)

Purchased through the RMIT Art Fund, 2013 RMIT University Art Collection Accession no: RMIT.2013.46

Kate CLARK

Born and lives New York, USA Gallant, 2016

Fallow deer hide, antlers, clay, foam, thread, pins, rubber eyes, wire 140 x 140 x 55 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Catherine CLOVER

Born London, United Kingdom, lives Melbourne, Australia

RMIT University Alumni

In a manner of speaking, 2017-2018

Audio recording, vinyl lettering on glass, printed score

Duration: 08:33

Courtesy of the artist

Beth CROCE

Born Washington, USA, lives Melbourne, Australia

Title Page

Letterpress print, ed.1 of 8

There was once a Prince One evening he chanced upon her Fate is fickle

An unsound heart Seeds of an idea Love is everything The operation Love was saved

The heart she fostered Her mother’s stories of love and loss

From the series ‘The Pig Prince; A Xenographic Tale’, 2018 Intaglio print with hand coloured watercolour and letterpress

All works ed.1 of 8

All works 35.5 x 25 cm

Collection of the artist

Julia DE VILLE

Born Washington

Born New Zealand, lives Melbourne, Australia Peter, 2012 Rabbit, antique sterling silver goblet 2.15g (925) 17 x 1 5 x 21 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Sophie Gannon Gallery, Melbourne

Heri DONO

Born and lives Yogyakarta, Indonesia Flying in Cocoons, 2001

Fibreglass, acrylic, papier mâché, cast iron, gauze, chicken wire, bulb, metal string, mechanical and electrical devices, automatic timer, transformer, foot switch, cable. 210 x 110 x 110 cm (x2)

Collection of Konfir Kabo, Melbourne

Peter ELLIS

Born Sydney, Australia, lives Melbourne, Australia

RMIT University Alumni, RMIT University Staff The Smoking Spine, 2002

Synthetic polymer emulsion, oil on canvas 182.88 x 121.92 cm

She Searched Him for the Cutlery (2), 2017 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Dreaming Monster, 2017 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Ghost, 2018

Ink, gouache on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

They Inhabit the Night, 2018 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

A Girl and Her Slug, 2017 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Woman with Snake, Christmas Eve, 2017 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Alien, 2017 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Young Faun in Forest, 2018 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Vacuum, 2018 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Minotaur, 2017 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Chimera, 2017 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Cursed Changeling with Pipe, 2017 Ink, gouache on cardboard 21 x 15 cm

Actaeon, 2017 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Lion with Sword, 2017 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Shower, 2018 Ink on Arches 300 gsm paper 21 x 15 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Moira FINUCANE with SHINJUKU THIEF

Born Perth, Australia, lives Melbourne, Australia

The Rapture/Fur Can't Fly, 2018

Sound, feathers, armchair, eyelid projection, vibration, motion code

Duration: 00:04:48

Text and Voice: Moira Finucane Music: Darrin Verhagen

Light & motion: Darrin Verhagen & Thomas Dahlenburg System: Jay Curtis Hardware courtesy of Audiokinetic Experiments (AkE) Lab, RMIT University

Rona GREEN

Born and lives Victoria, Australia

The Surgeon, 2010 Hand coloured linocut 108 x 76 cm

Dusty Rhodes, 2011 Hand coloured linocut 76 x 56 cm

Dutch, 2009 Hand coloured linocut 45 x 38 cm

Pascal, 2017 Hand coloured linocut 57 x 57 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Australian Galleries, Melbourne

Robert GRAVE

England 1798–1873

Portrait of Nathaniel St. André, date unknown Line engraving 25.7 x 16 cm

Image reproduced courtesy of Wellcome Collection, UK

Ernst HAECKEL Prussia 1834-1919

Anthropogenie (comparative embryos of hog, calf, rabbit and man), 1874 Line engraving 30 x 20 cm

Image reproduced courtesy of Wellcome Collection, UK

Born and lives Tokyo, Japan

I wanna deliver a dolphin, 2011-2013

Digital video

Duration: 02:39

Courtesy of the artist

Diagrams of a foetus and medical instruments, 1751

Line engraving

24 x 16 cm

Collection of the British Library, London

Image reproduced with permission of the British Library, London

Rayner HOFF

United Kingdom and Australia 1894-1937

Faun and Nymph, 1924 Bronze sculpture 26.5 x 29 x 13 cm

Private collection, Sydney

William HOGARTH

England 1697-1764

Mary Tofts appearing to give birth to rabbits in the presence of several surgeons and man-midwives sent from London to examine her, 1726

Etching 52 x 70 cm

Image reproduced courtesy of the Wellcome Collection, UK

Sam JINKS

Born Bendigo, Australia, lives Melbourne, Australia Medusa (Beloved), 2016 Silicone, pigment and resin 71 x 49 x 29 cm

Collection of Latrobe Art Institute, Bendigo

Deborah KELLY

Born Melbourne, Australia, lives Sydney, Australia

Beastliness, 2011

Digital animation from paper collages

Duration: 03:17

Animation: Christian J Heinrich and Chris Wilson

Original Score: The Brutal Poodles

Venus of Beeness, 2017

Paper collage reproduced in pigment inks on silk banner

100 x 200 cm

Mervenus, 2017

Paper collage reproduced in pigment inks on silk banner

100 x 200 cm

Courtesy of the artist

The Magdalenes (Penitence), 2012

Archival print on hahnemuelle photorag with paper collage, UV protective matte varnish 206 x 112 cm

The Magdalenes (Praise), 2012 Archival print on hahnemuelle photorag with paper collage, UV protective matte varnish 206 x 112 cm

Private Collection, Melbourne

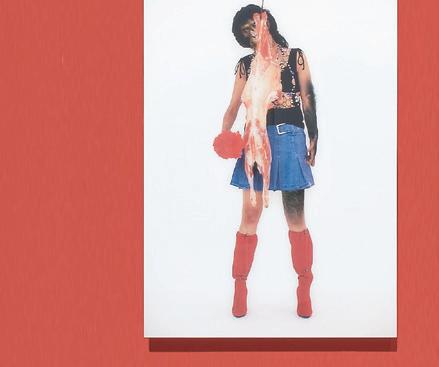

Bharti KHER

Born London, United Kingdom, lives New Delhi, India

The Hunter and the Prophet, 2004

Photographic print on aluminium composite panel 76.2 x 114.3 cm

Feather Duster, 2004

Photographic print on aluminium composite panel 76.2 x 114.3 cm

Angel, 2004

Photographic print on aluminium composite panel 76.2 x 114.3 cm

Chocolate Muffin, 2004

Photographic print on aluminium composite panel 76.2 x 114.3 cm

Family Portrait, 2004 Photographic print on aluminium composite panel 76.2 x 114.3 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Deborah KLEIN

Born and lives Victoria, Australia European Wasp Woman, 2015 Watercolour on on Khadi rag paper. 41.9 x 29.7 cm

Ladybird Woman, 2014 Watercolour on on Khadi rag paper. 41.9 x 29.7 cm

Actinus imperialis Beetle Woman, 2014 Watercolour on Khadi rag paper. 41.9 x 29.7 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Oleg KULIK

Born Kiev, Ukraine, lives Moscow, Russia Family of the Future, 9, 1997

Digital print, performance based photography

136 x 150 x 5 cm

Collection of the Museum of Old and New Art, Tasmania

Sam LEACH

Born Adelaide, Australia, lives Melbourne, Australia

RMIT University Alumni Pedestal 2, 2018 Oil on canvas 101 x 92 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Norman LINDSAY

Australia 1879-1969 Desire, 1919 Etching 56 x 50 cm

Private collection, Sydney Afternoon of a Faun, c.1920 Etching 21.5 x 21.5 cm

Private collection, Sydney

A portrait of Mary Tofts, a woman who pretended that she had given birth to rabbits, date unknown Stipple engraving with watercolour 22 x 16 cm

Image reproduced courtesy of Wellcome Collection, UK Sidney NOLAN

Australia and United Kingdom 1917-1992 Leda and Swan, 1960

Synthetic polymer paint on composition board 121 x 121 cm

Collection of the Art Gallery of Ballarat. The William, Rene and Blair Ritchie Collection. Bequest of Blair Ritchie, 1998; 1998.19

Eko NUGROHO

Born and lives Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Trap Costume for President Z, 2011

Embroidered rayon thread on fabric backing 190 x 146 cm

Collection of Konfir Kabo, Melbourne

Kira O’REILLY & Jennifer WILLET Kira O’REILLY Born Ireland, lives Finland Jeniffer WILLET Born and lives Ontario, Canada Untitled from the ‘Pig Tales and Show Girls Protocol’ series, WAAG Society, the Netherlands, 2009 Photographer: Bernd Bohm Digital print in convex glass frame 40.6cm x 50.8 cm

Courtesy of the artists

Patricia PICCININI

Born Freetown, Sierra Leone, lives Melbourne, Australia Belly from the ‘Hair Panels’ series, 2011 Silicone, fibreglass, human hair 70 x 70 x 7 cm

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne Purchased with funds from the Truby and Florence Williams Charitable Trust, ANZ Trustees 2013

Geoffrey RICARDO

Born and lives Melbourne, Australia Match, 1997 Lithographic print 30 x 42 cm

Another Otherwise, 2014 Intaglio print 50 x 50 cm

Bigfoot, 1997 Intaglio print 15 x 18 cm

Tall Tales, 2008 Copper sculpture 190 x 96 x 80 cm Untitled, 1993 Bronze sculpture 18 x 15 x 6 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Born and lives Melbourne, Australia

RMIT University Alumni

Humanzee pt. 2 from the series ‘When I laugh, he laughs with me’, 2014

Type-C photograph, edition 1 of 3 103.5 x 145 cm

Photographic support: James Geer Blond Venus 1932 from the series ‘Bride of the Gorilla’, 2014

Type-C photograph, edition 1 of 3 163 x 116 cm

Photographic support: James Geer Courtesy of the artist

Born West Bengal, India, lives New Delhi, India

In our hands…Nothing (Egon and Me) 1, 2010

Mixed media on handmade paper 70 x 100 cm

Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris and Brussels

William SMELLIE (obstetrician and designer)

Scotland 1697-1763

Smellie’s Forceps, c.1750

Obstetric forceps; iron, leather, metal sheet coating 4 x 30.5 x 11 cm approx.

Collection of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Melbourne

Maja SMREKAR with Manuel VASON

Born and lives Ljubljana, Slovenia

Untitled from the performance ‘K-9_topology: Hybrid Family’, 2016

Documentary film

Duration: 00:04:35

Untitled from the performance ‘K-9_topology: Hybrid Family’, 2016

Digital print, performance based photography

Three images; 82 x 122 cm each Courtesy of the artists

Unknown artist (attributed to Nicola HICKS) Minotaur, c. 20th century Bronze sculpture 24.5 x 40 x 24 cm

Collection of Jennifer Shaw, Melbourne

Born Christchurch, New Zealand, lives Melbourne, Australia Monkey Madness, 2001

Digital print on archival museum rag paper 82 x 122 cm Self, 2001

Digital print on archival museum rag paper 82 x 122 cm

Beastliness, 2011, digital animation from paper collages, duration: 03:17, courtesy of the artist

My Monster: The Human-Animal Hybrid ISBN: 978-0-6484226-1-7

My Monster: The Human-Animal Hybrid Curated by Evelyn Tsitas

RMIT Gallery 29 June – 18 August 2018

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to the participating artists and designers for their generous support, insight and commitment to the exhibition.

Appreciative thanks also to Professor Calum Drummond, DVC R&I; Professor Paul Gough, PVC DSC; Jane Holt, Executive Director R & I;

Evelyn Tsitas would also like to thank Jane Holt, Executive Director R & I for making this exhibition possible; RMIT Gallery Acting Director Helen Rayment for her unwavering commitment and support of the exhibition and her guidance in all matters of exhibition co-ordination; Nick Devlin for his generous support during installation; Jon Buckingham for sourcing work from the RMIT Art Collection and Meg Taylor for her assistance and enthusiasm for the project.

Acting Director & Senior Exhibition Coordinator: Helen Rayment

Senior Advisor Communications & Outreach Evelyn Tsitas

Exhibition Installation Coordinator: Nick Devlin

Installation Technicians: Fergus Binns, Beau Emmett, Robert Bridgewater, Ford Larman

Collections Coordinator: Jon Buckingham

Collections Assistant: Ellie Collins

Gallery Operations Coordinator: Mamie Bishop

Exhibition Assistant: Meg Taylor

Administration Assistants: Sophie Ellis Valerie Sim Maria Stolnik Thao Nguyen Vidhi Vidhi

RMIT Gallery Interns & Volunteers: Natalie Vella Simon Aubor

RMIT Gallery / RMIT University www.rmitgallery.com

344 Swanston Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Tel: +61 3 9925 1717 Fax: +61 3 9925 1738 Email: rmit.gallery@rmit.edu.au

Gallery hours: Monday-Friday 11-5 Thursday 11-7 Saturday 12-5. Closed Sundays & public holidays. Free admission. Lift access available.

Catalogue published by RMIT Gallery December 2018

Graphic design: Karen Scott

Catalogue editor: Evelyn Tsitas

Catalogue research: Evelyn Tsitas

Catalogue photography: Mark Ashkanasy

RMIT University acknowledges the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nation on whose unceded lands we conduct the business of the University.

RMIT University respectfully acknowledges their Ancestors and Elders, past and present. RMIT also acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and their Ancestors of the lands and waters across Australia where we conduct our business.