Photography by Gabi Linke

Photography by Jorja Stratton

Photography by Lilian Ma & Sam Nelson

Photography by Sam Nelson

Photography by Mia DiNorcia

Photography by Christian Murphy

Photography by Christian Murphy

Photography by Christian Murphy

The emergence of punk in 1970s Britain is a defining moment in the country’s cultural history.” Its birth is often linked to the Sex Pistols, whose hit tracks like “Anarchy in The UK” (1976) and “God Save the Queen” (1977) provoked controversy and distinguished punk as an explicitly politicized youth culture. This image became solidified as punk bands integrated themselves into movements such as Rock Against Racism, and included overt commentary in their music about gender, class and race issues, as well as issues of consumption and authoritarianism.

The development of punk in the US followed a similar vein, stemming from the underground music scene in major cities like New York, and becoming more explicitly politicized by anarchist bands such as Ramones and Black Flag. Punk culture was

significant in creating a space for youth rebellion and political involvement, especially during the Reagan Era. Punk youth protested government intervention in South and Central America, protested the threat of nuclear annihilation and protested Reagan’s mental health reform, amongst a multitude of other issues at the time. It was one of the most significant and radical threats to Reagan’s politics throughout the 80s, as it saw a movement led entirely by teenagers and young adults rebelling against the status quo. The very idea of a youth revolt has long been one that has threatened the institutions in power.

Although punk began to die down in the late 90s and early 2000s, it has maintained a place as an important political movement that has driven social change. As it begins to make a resurgence in Gen Z music and popular culture, many have started to ask–why now? Many associate the newer generation with an increased awareness of social issues, coming with a culture of tolerance and acceptance that is unprecedented in the Western world. Whilst this may be true, we have also seen an emergence and normalization of dangerous political ideology similarly emerging in the last decade.

Potentially linked to the rise of Donald Trump as a political figure in America, the conservative ideology in the United States has evolved to one in which men can buy their way into the government, stand on stages in America, throw up the Nazi salute and face minimal consequences. As the rights of women, people of color, immigrants and LGBTQ+ people come under threat, the necessity for youth political involvement and rebellion becomes more important than ever. With the dissemination of information becoming more limited due to restrictions on apps like TikTok, punk takes a more important role in creating a space for young people to band together to oppose government control. The need for music as a method for demonstrating dissent becomes increasingly significant as our ability to communicate with one another becomes confined to those controlled by billionaires who are pawns of the government. Although there is the misconception that you have to look a certain way to be punk, the idea of punk has evolved from “one look” to an ideology that rejects an authoritarian rule, rejects consumerism and is anti-establishment, instead valuing freedom, expression and nonconformity. As tensions continue to rise throughout the Trump presidency, punk culture will become more important than ever.

Photography by Sam Nelson & Christian Murphy

Photography by Sam Nelson & Lilian Ma

Photography by Sam Nelson

Photography by Lilian Ma

Photography by Christian Murphy

Photography by Garrett Botsch

Photography by Gabi Linke

Photography

Christian Murphy

Photography by Lilian Ma

Photography by Lilian Ma, Christian Murphy, Camron White

Photography by Christian Murphy

Photography by Sam Nelson & Christian Murphy

Photography by Sam Nelson

Moving Forward Moving Forward Ava Rotman

From ceiling to baseboard, the only “empty” and free space in my room is my walking path from the door to my bed, to my closet and vanity. I’ve curated my organized clutter through gathered trinkets I’ve obtained from small day trips with friends I know well. I’ve spent every school day, after school and honestly, almost every weekend with them since we first met. I’m unsure what comes next; we’re all off to college and this week it’s my turn. I somehow have to manage to condense my maximalist lifestyle into a couple of boxes to move into a shared dorm. I’ve spent all of summer putting it off but there’s no more time to procrastinate.

My mother says to only bring things that have importance and necessity. But what counts as a necessity? – every aspect of my room is important to me, or at least it was.

I decided to first take on my walls for decor. Gently pulling down posters from concerts I’ve attended over the years– I’d certainly want those for college. Then grabbing other framed photos and items to add texture… that’s when my focus shifted to the dried-out lily and rose bouquet I had received from my now ex-boyfriend for senior year prom. Senior prom was incredible, getting to spend the last dance with all the people I loved, friends and him; with no care in the world about how different things would become in the next few months. No more movie dates, participating in TikTok trends or late-night drives to Flagstaff to look at the stars and plan out our future together. I quickly grabbed the last of the wall decorations I wanted for my dorm, shoved them into the box and moved on.

I trudged towards my vanity, noticing all the knick-knacks covering the surface and those shoved into the crevice between my mirror and the wood. My hand grasps the vintage photo booth picture taken my junior year with my best friend with our smiling faces looking back at me. My mind wanders off to all our hangouts; we’d frequent our favorite thrift shops, and Broadway in Denver. We’d play dress up for hours, get coffee at one of the several coffee shops nearby and just talk about who from our school was together now and who broke up. What happened within our household units that week– no concern about college or about being separated 1,000 miles away from one another. I don’t know what I’m going to do without her. She’s my other half and now we’re at two completely different colleges on the opposite ends of the country.

I never expected cleaning out my room to be so saddening and bittersweet. I had packed my whole pre-college life into only a couple of boxes. Every item has a memory attached to it, some even a person.

Knock Knock.

“How’s packing going? Are you ready to move it all into the car?” asked my mother.

Her smile was gentle and sad. I was going to miss her, miss everything I had here back in my hometown but soon I’d gather new items, new memories and people.

“Yeah, I think I’ve brought all the items I need and want. If not, I can always come back.”

Photography by Gabi Linke

52 Photography by Christian Murphy

Photography by Lilian Ma

Photography by Garrett Botsch

Blue

Couch Grace Moore

58 Photography by Tylyn King

You remember how it felt, don’t you?

Don’t you? Sitting there, your ninth birthday. A day not about you because it was also Mother’s Day. A day like any other, really. Everyone had just celebrated Mother’s Day. Your Grandma got gifts, your mom got gifts and you got a gift too. It wasn’t anything special. Something so unspecial you can’t even remember what it was. It didn’t really matter. You looked up from the new t-shirt, or maybe it was a coloring book, it really didn’t matter. All you’d wanted was a new coat for next winter so you wouldn’t get bullied at school for having a coat that was “too girly” again, but

“I’m sorry honey, we just couldn’t afford it this year.”

“No Mom it’s ok really,” you sigh.

Everyone’s getting drunk on the back patio, enjoying the May breeze. But you’re still on that blue couch. A blue couch, that had seen the birth of your aunts, your birth and your grandfather’s death, would now see you sit and stare at the same old wallpaper. You can feel that haunting loneliness that seems to start in your knees, making them weak, then your hands start to sweat and your heart starts to ache. The blue couch feels like it’s floating in space away from anyone who could ever save you. You begin to contemplate why you hadn’t been given a coat.

“It’s because you’re not that special,” you told yourself.

The other girls at school, they’re special. They get Christmas gifts, birthday gifts, St. Nicholas Day gifts and Tuesday night gifts. They’d have a new winter coat if they wanted one. It always seemed like their mothers loved them so much. Not you. All you get is the sight of old carpet and a haunting feeling that this is all that you’ll ever get, all that you’ll ever be. Forever.

Time passes, it’s a few years later, your little sister’s ninth birthday. Today it’s in a townhome your parents rent, a new development. The corners of the walls are rounded. Every detail is taken care of. Your sister gets everything she wants: the newest Barbie dolls, stuffed animals and an iPod touch. You smile and clap for her. You watch as she opens gift after gift. You can’t help but think about that blue couch.

Your mom comes to you when you’re alone that night, feeling the fall breeze through the windows. She comes to you in tears.

“I know you saw all that Leslie got for her birthday,” she says.

“I wish I could’ve gotten all that for you on your ninth birthday.”

“I know Mom,” you say. “You shouldn’t feel bad.

You comfort her as she cries into your arms. Suddenly, you have to be strong again, just as you did that one night in May.

“It’s ok, Mom.”

Now here you are in your college apartment. That girl feels so far away. You can’t even still be her; your couch is gray now. But when you sit with yourself you can still feel that old blue couch. You can feel the pilling on your hands even though they’re just dangling by your side. You’ll always be that girl. Forever. Even though you’re twenty now you’ll always be that nine-year-old girl that didn’t even have her own birthday. You’ll always remember how it felt. Won’t you?

60 Photography by Christian Murphy

“In another life, I would have really liked just doing laundry and taxes with you.”

Photography by Sam Nelson

64 Photography by Christian Murphy, Sam Nelson & Tylyn King

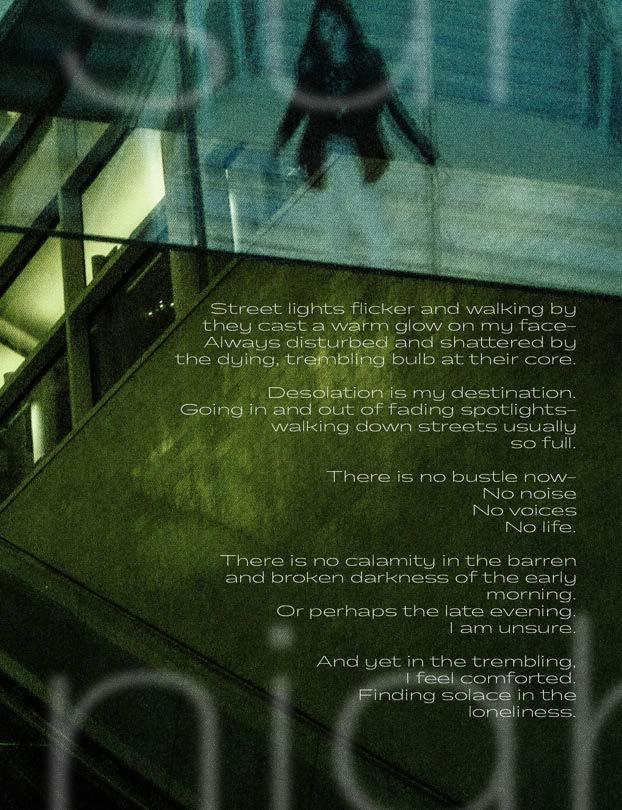

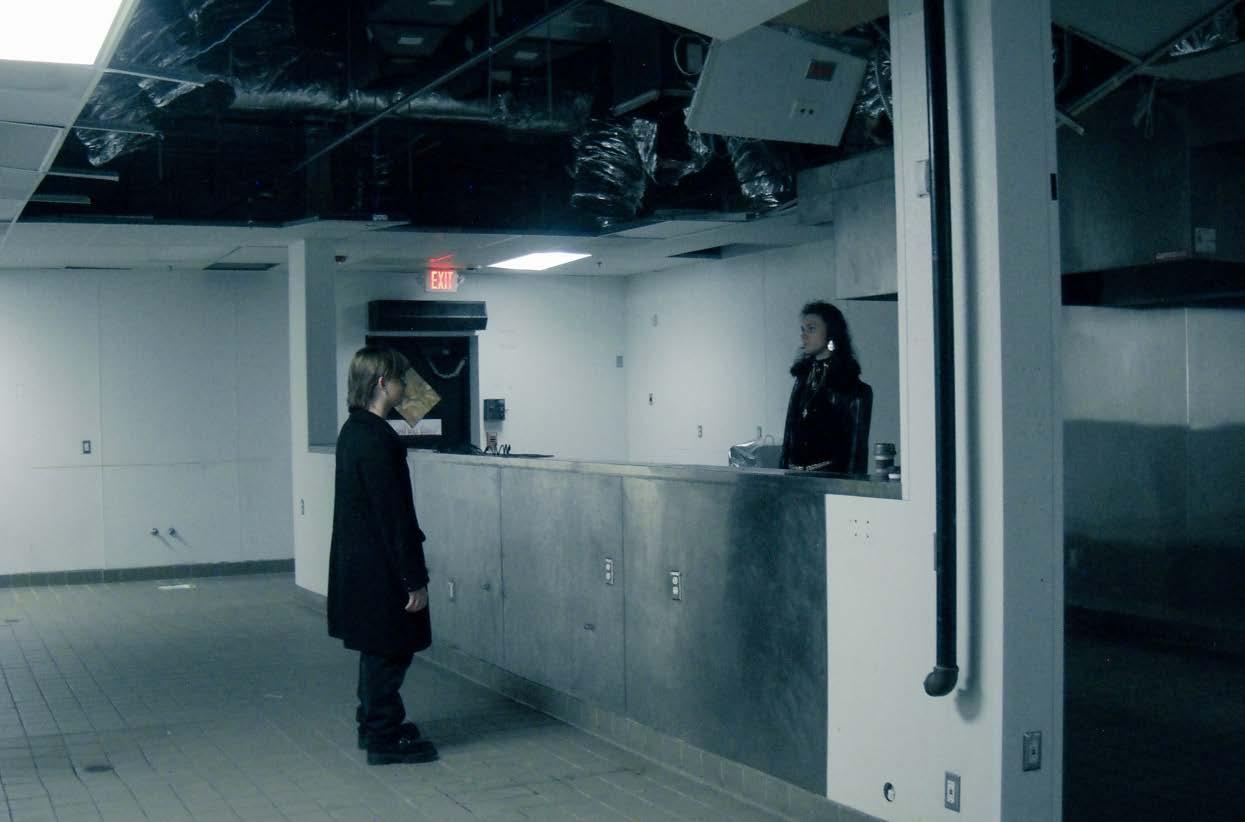

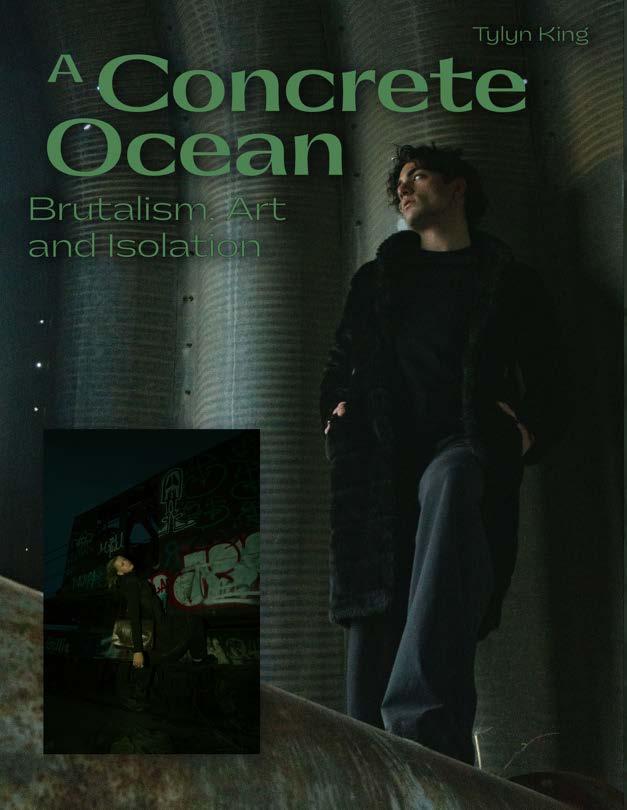

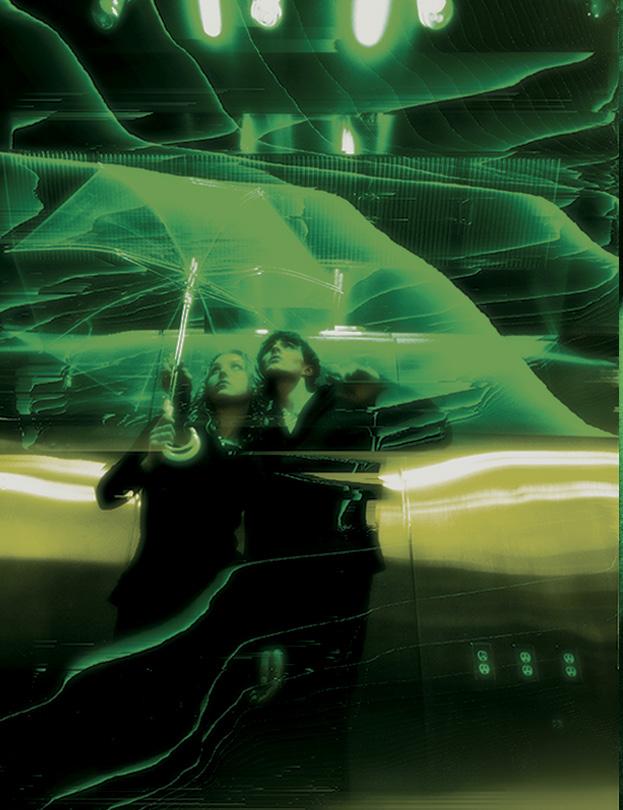

Many yearn for an escape from an industrial urban landscape. The fear of the future is abundant in today’s world. The past several years have left people shocked and scared for what’s to come. The unknown swallows all the future that cannot be seen or predicted. Brutalist-style art conveys those impressions of deserted urban and isolation stretching beyond the horizon.

Brutalism began as an architectural movement in the 1950s. The name originates from the French word bréton brut, meaning “raw concrete.” After World War II, countries found concrete to be affordable for rebuilding after the war’s impact. The style’s popularity decreased in the 1980s due to an association with totalitarianism and authoritarian structures.

Motifs in brutalism include dense blocks of concrete, monochromatic or grayscale palettes and sharp geometric shapes. Brick, glass, steel and unfinished surfaces are also common. Brutalism visually provides a colossal sense of strength and boldness. Coldness, isolation and loneliness seem prevalent in brutalist structures.

Brutalist art can appear in forms outside of architecture. Designer Martijn van Strien created a fashion collection inspired by brutalist architecture. Presented in Dutch Design Week 2013, Dystopian Brutalist Outerwear was produced through heavyduty tarpaulin. Each piece of clothing was cut with a single piece of tarpaulin and used sealed seams. Van Strien intended to use durable materials with swift and inexpensive manufacturing techniques.

Van Strien’s motivation likely comes from the fear and mystery of the future—the economic and social decline on Earth will leave behind mountains of uncertainty. The choice of the black coats represents protection against the fear and downfalls of life. Through the sleek, reflective raincoats, van Strien combines utility with narrative. The collection’s blocky shapes hide the model’s silhouette as if the wearer hides away from the pain of the world’s future.

Kanjiro Moriyama’s ceramic collection End of the World Supernova II (2020) reveals knife-like edges. Although not stated by the artist, Moriyama’s art seems reminiscent of brutalist motifs. The artwork’s monochromatic swirl of shapes seems to defy

gravity. The series combines alternating layers of smooth, curvy and sharp pointed lines.

Through wheel-throwing, Moriyama creates cylindrical pots and then cuts and rearranges them into abstract sculptures. This technique forms an overall sense of disconnected parts that create a wholeness. The pieces are separate yet together, much like an isolated humanity connected through technology.

Loneliness and the feeling of being trapped in urban concrete are very prevalent. Through a growing world of technology and the effects of COVID lockdowns, people are more scared of being lonely than before. Less on brutalism and more on isolation in art, Edward Hopper’s painting Nighthawks (1942) demonstrates urban isolation through brushstrokes. Through oil painting, Hopper illustrates a landscape of loneliness.

Four customers sit alone at a diner. Three customers, one server. The couple speaks with the server, while a lone man contemplates his troubles. The wide space of the street outside the diner conveys an emptiness. Silence whispers into the night outside, where no one is around to hear the couple’s conversations.

With the diner’s warm yellow lighting and turquoise exterior, the painting is both inviting and solitary.

by Lilian Ma

Photography

Photography by Sam Nelson & Lilian Ma