THE ODYSSEY HOMER

A Prose Rendering by Wesley Callihan

The Odyssey

First Edition

Copyright © 2023 by Wesley J. Callihan

Published by Roman Roads Press

Moscow, Idaho

info@romanroadspress.com | romanroadspress.com

Prose rendering by Wesley J. Callihan, based on the 1879 translation of Samuel Butcher (1850–1910) and Andrew Lang (1844–1912).

General Editors: Daniel Foucachon and Wesley Callihan

Edited by Carissa Hale

Cover Design by Joey Nance and Daniel Foucachon

Cover Image: Athena appearing to Odysseus to reveal the Island of Ithaca (oil on canvas) by Giuseppe Bottani (1717-1784).

Interior Layout by Carissa Hale

Adaptions of John Flaxman’s 1793 illustrations by Carissa Hale

Maps by Carissa Hale and Joey Nance

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher, except as provided by the USA copyright law.

Licensing and permissions: info@romanroadspress.com

The Odyssey

Roman Roads Press

ISBN: 978-1-944482-79-4

Version 1.0.0 July 2023

To Andrew KernWhose delight in the perpetual feast has inspired my own for almost three decades

I say that there is no more perfect delight than when all the people make merry, and the men sit orderly at the feast in the halls and listen to the singer, and the tables beside them are loaded with bread and meat, and a wine-bearer drawing the wine serves it round and pours it into the cups. This seems to me the fairest of all things.

( Odyssey 9.5–11)

As one that f or a weary space has lain

Lulled by the song of Circe and her wine

In gardens near the pale of Proserpine, Where that Ææan isle forgets the main, And only the low lutes of love complain, And only shadows of wan lovers pine,

As such an one were glad to know the brine

Salt on his lips, and the large air again, So gladly, from the songs of modern speech Men turn, and see the stars, and feel the free Shrill wind beyond the close of heavy flowers, And through the music of the languid hours

They hear like Ocean on a western beach

The surge and thunder of the Odyssey.

~ Andrew LangAcknowledgments ix

Preface xi

Introduction xiii

1. The Importance of Homer xiii

2. The Historical Christian Perspective xv

3. The Historical Background of the Story xix

4. The Story of the Trojan War xxv

5. Between the Iliad and the Odyssey xxxi

6. The Form and Context of Homeric Epic xxxiv

7. The Contents and Structure of the Odyssey xli

8. Xenia (the guest-host relationship) in the Odyssey xlv

9. Major Characters in the Odyssey xlviii

10. How to Read the Homeric Epics lii

11. What to Read Next lv

12. This Version—and Why Another One? lvi

Maps of the Odyssey lxi The

A C knowledgements

Iproduced this text during a year of teaching Homer, finishing rough drafts of each book of the Odyssey just ahead of each week’s assignments. My students read and commented, finding grammatical, syntactical, and stylistic errors; they suggested additions and deletions and footnotes for further explanation, all of which helped me immensely. Lucy Barry, Katharine Kotecki, John Matheny, Lisa Mayeux, Angela Morgan, Kelly Raquipiso, Tracey Leary, Mastin Barry, and Aubrey Robinson all contributed, especially the last three.

As with my Iliad , I’m grateful to Carissa Hale for her patience, thorough editing work, and unfailing cheerfulness; and to Daniel Foucachon, ἄναξ of Roman Roads Press, whose irrepressible enthusiasm for the Homer project kept me moving when the lotus blossoms of life threatened my journey.

Ihave written a lengthy introduction to this version of the Odyssey in hopes that it will help many to understand and appreciate better what they find themselves reading. It is identical in many sections to the Introduction to the Iliad , but of course there are sections devoted specifically to the Odyssey . If the reader has already read the Introduction to my Iliad , be sure to at least read sections 7, 8, 9, 11, and 12 in this Introduction.

The study of history has fallen on hard times in the last couple of generations, but it seems obvious that context matters when studying anything, and history is the context of the Odyssey , just as it is of the Bible, or any other text we read that does not come from our modern cultural milieu. We know more about ourselves when we know something of our family history, and in the same way we understand more about our culture if we know its history, and that includes both the great books that have shaped our culture, and the historical context out of which those books grew.

1. The Importance of Homer

Homer’s two poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey , set against the backdrop of the Trojan War, are the earliest complete works of imaginative literature in the Greco-Roman tradition which is the foundation of Western Civilization. They have had an incalculable influence on the Mediterranean civilization of which we are heirs, and on the medieval and modern civilizations of Europe and the Americas which grew from that one.

The Iliad and the Odyssey were, without exaggeration, as important to ancient Greek culture as the Bible has been to medieval and modern European civilization. The two poems profoundly influenced the Greek understanding of man— what he is, and what he should be, and why there is a difference between those two things—and of his relationship to the gods, to other people, to the world around him, to time and space, to power, to good and evil, to freedom and will and their limitations, and to virtue and the nature of a good life. From the days of ancient Athens onward through the long centuries of the Roman and Byzantine Empires, the European Middle Ages, and the early modern European and

American worlds, until the twentieth century when our New Dark Age was well underway, it would have been incomprehensible to call oneself educated without having read Homer. The Iliad and Odyssey were memorized in their entirety by many literate Greeks and Romans as they formed the backbone of education in the Greek and Roman worlds in the pre-Christian and Christian ages alike. In the European Middle Ages the knowledge of Greek and of Greek literature was almost entirely lost until the Renaissance, but the stories were known and loved through Latin translations and retellings. In the Byzantine East, however, Greek literature continued to be foundational for education, and after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Greek language and its literature flooded into western Europe carried by fleeing Eastern Christians. From the late Renaissance on, the study of Homer and of the Greek language became an essential part of education in Europe (and wherever in the world European influence went) until very recently. Because literate people have always read and loved Homer, there are quotations, references, and allusions to Homer everywhere in literature from the ancient Greeks (Aristotle and Plato), Romans (Vergil and Cicero), and the early church fathers (Basil the Great and Augustine) to more modern authors (Spenser, Milton, Pope, Jane Austen, Lewis, Tolkien, Chesterton) up through the twenty-first century. Some of the basic metaphorical elements in literature and even everyday speech come from Homer. We speak of a “Trojan horse” (a damaging element invading computer software under cover of something more innocuous), an “Achilles heel” (a vulnerability of any kind), a “siren-song” (something tempting that leads to destruction), “hectoring” (harassing), and so on. Because great authors have always assumed that their audiences read Homer too, to read those authors without knowing Ho-

mer is to fail to understand or even to misunderstand much of what they wrote.

So powerfully has it always been felt that Homer’s epics are the foundation and greatest works of the European literary tradition, that G. K. Chesterton says “…it is true that this [the Iliad ], which is our first poem, might very well be our last poem too. It might well be the last word as well as the first word spoken by man about his mortal lot, as seen by merely mortal vision. If the world becomes pagan and perishes, the last man left alive would do well to quote the Iliad and die.”1

2. The Historical Christian Perspective

Note Chesterton’s words well: as seen by merely mortal vision. The Christians, who began showing up in the early years of the Roman Empire, had more to say about man’s existence and meaning, which they learned not from philosophical speculation (“merely mortal vision”) but from something beyond, that is, from supernatural revelation—from the Hebrew prophets, from the Jewish and Christian scriptures, and most importantly, from the incarnate God Himself, Jesus Christ.

But significantly, this did not include a rejection of Homer’s poems or of pre-Christian literature and thought in general. The vast majority of the early Christian writers— the “early church fathers” of the first millennium of Christianity—were educated in the classics of Greece and Rome, as well as in the Scriptures and earlier Fathers, and almost without exception they did not reject that learning but rather 1

advocated it. Indeed, some of the great Christian catechetical schools, such as the famous one in Alexandria in Origen’s time2 and after, included instruction in the classics as well as in Christian writings and doctrine. The great majority of these early leaders of the church did not consider Christianity a replacement for or repudiation of much of earlier Greco-Roman philosophy and religious thought, but a fulfillment of it. Irenaeus of Lyons, Clement of Alexandria, Athanasius the Great, Basil the Great, Gregory of Nazianzus, Gregory of Nyssa, Ambrose of Milan, Hilary of Poitiers, Augustine of Hippo, Maximus the Confessor, John of Damascus, and countless others reference or allude to the ideas, categories, and images from Homer, Plato, Aristotle, the historians, the dramatists, and other ancient Greek authors to illustrate and explain Christian teachings, just as the apostle Paul did in the New Testament.3

Even more amazing is the fact that on the walls of many churches and monasteries in Greece (and even on many icons) there are depictions of some of the ancient “pagan” authors (including Homer, the Sibyl, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Thucydides, Apollonius, Plutarch, and others) next to the depictions of the great saints of the past (though without the halos that identify the saints). This is because these pre-Christian authors were thought of as “forerunners” of Christianity, having used human reason to try to follow the prompting of their consciences, to try to find the God all humans know is there because all are made in His image. Though they could not find Him on their own without Christ the Logos, they were feeling in the right direction. Justin Martyr, one of the early “fathers,” says that the “see of the Logos” is present

2 Early third century AD.

3 See, for instance, Acts 9, 17, 26; 1 Corinthians 1–3, 9, 15; and Titus 1.

everywhere; 4 that is, the knowledge of God is implanted in all things because all things have been made and are continually sustained by God the Word. And most amazing of all is that some of the early Christian writers—Justin Martyr himself, for example—say that some ancient Greeks like Socrates could be called, in some sense, “Christians,” though they didn’t know Christ by name, because they had been faithful to what little light they’d been given in the witness of creation and their consciences, and so probably “saved.”5

Whether we agree with this or not is irrelevant. The point is that the early Christians did not reject all of pagan thought—though naturally some of it must be rejected—but instead loved and used it, redeeming it by appreciating what was good, true, and beautiful in it (God being the true source of those things) and turning it to fully Christian purposes. The prevailing attitude among Christians not only in this early period but throughout Christian history6 has always been that Christ does not come to destroy cultures but to redeem them. One famous Christian advocate of ancient learning was Augustine, the great bishop of Hippo in north Africa, who had a classical education as a young man. He became a brilliant teacher of literature and rhetoric but quit teaching when he became a Christian—not because he rejected those things but because he refused to arm the enemies of Christ. In other words, he saw classical learning as a powerful thing to be put into the right hands, not the wrong ones. He complains in his Confessions about some aspects of his classical education as a youth, but not about the education itself—rather, he objects

4 Justin Martyr, Second Apology , chs. 8 and 13.

5 Ibid., ch. 46.

6 See Don Richardson’s books Peace Child and Eternity in Their Hearts for a modern example of this perspective.

to the emphasis on correctness in learning with no corresponding emphasis on virtue. And most famously, he exhorts Christians to “plunder the Egyptians”—that is, to take what is valuable from classical learning but leave the chaff:

If those who are called philosophers, and especially the Platonists, have said aught that is true and in harmony with our faith, we are not only not to shrink from it, but to claim it for our own use from those who have unlawful possession of it…all branches of heathen learning have not only false and superstitious fancies and heavy burdens of unnecessary toil, which every one of us, when going out under the leadership of Christ from the fellowship of the heathen, ought to abhor and avoid; but they contain also liberal instruction which is better adapted to the use of the truth, and some most excellent precepts of morality; and some truths in regard even to the worship of the One God are found among them …These, therefore, the Christian, when he separates himself in spirit from the miserable fellowship of these men, ought to take away from them, and to devote to their proper use in preaching the gospel. (italics mine)7

Another famous Christian advocate of classical learning was Basil the Great, bishop of Caesarea (in modern-day Turkey). He wrote an address or letter to young men about the right use of Greek literature (by which he meant “pagan” literature). Like Augustine, he urges caution and discernment between the good and evil in it, but he also urges the value of studying it because so much of the best of it teaches virtue and the pursuit of the good, the true, and the lovely. And of course, Homer would have been the first name in Greek literature.

From these ancient Christians until the present day, the nearly universal attitude of Christians toward the ancient classics is that of appreciation for the truths and beauties in them, though urging caution to separate wheat from chaff.

3. The Historical Background of the Story

(For this section, refer to Maps 1 and 2 at the end of the Introduction)

A great civilization called the Mycenaeans 8 dominated southern Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean around 1700–1100 BC, constructing spectacular cities, palaces, and navies; they left libraries full of written records and a brilliant tradition of stories about their great kings and heroes and their wars and adventures. It is from this civilization that most of the great Greek stories come—Jason and the Argonauts, Herakles (whom the Romans called Hercules), Oedipus and the Theban wars, and the Trojan War. There is good literary and archaeological evidence that they were seafarers and therefore made extensive contact with other empires of the eastern Mediterranean world. One such empire was that of the Hittites, who dominated much of Anatolia (modern Turkey) and who also left a great quantity of written records; when the Hittite cuneiform tablets were unearthed by archaeologists in the late nineteenth century and later translated, references were found to the Trojans, their king Priam, Paris the prince, and the Achaians (the Greeks who fought the Trojans). The Mycenaeans also

8 So called because of the great city of Mycenae, in the northeastern part of the Peloponnese (the southern half of Greece south of the Gulf of Corinth), which dominated the culture. See Map 2.

had contact with the Egyptians, whose records also mention the Mycenaeans. Finally, the Israelites in the time of Joshua through that of King David (roughly 1300–1000 BC) had contact with the Mycenaeans; in fact, many scholars argue that the Philistines mentioned so frequently in the Old Testament were Mycenaeans who had settled in the vicinity of the Israelites, but before the Israelites arrived. If this is so, then the giant Goliath whom young David defeats in the Old Testament may in fact be of the same race as the colossal Aias in the Iliad , who uses a spear thirty-three feet long (Bk 15) and carries such a gargantuan “tower” shield that most men couldn’t lift it.

But another civilization called the Dorians, more primitive and barbaric, swept down from the north into Greece starting around 1100 BC and destroyed the Mycenaean civilization, dispersing many of the people eastward to the Aegean islands and Ionia (the west coast of modern-day Turkey). This was part of a larger Late Bronze Age Collapse of the twelfth century BC, in which many of the previously great cultures of the region, including the Hittites and Egyptians, were overcome by foreign conquerors or for other reasons declined radically from their early greatness. The Greek world fell into its dark age, with local feudal lords warring with each other, no great buildings being raised, no vast armies plowing the Mediterranean, and in general a low level of culture prevailed. One of the worst aspects of this period (and one of the main reasons it is called a Dark Age) is that the art of writing was lost and there are no written records at all from this period.

When the Anglo-Saxons invaded Britain in the late fifth century after Christ, decades after the Romans had left the island, they stared in amazement at the ruins of the great buildings and walls the Romans had constructed over the

previous four centuries. An Anglo-Saxon poem from the time called “The Ruin” describes their awe at what the builders must have been—giants, brilliant and wealthy beyond all reckoning. This is how the Greeks of Homer’s day would have looked on the remains of the old Mycenaean world, had anything survived. But even the ruins of the old palaces and cities, along with all written records, were in the course of nature heavily covered over with soil and vegetation by Homer’s time four hundred years later, and the only knowledge they had of the greatness of the Mycenaean Age, the age of their heroes, was the oral tradition of stories passed down from generation to generation.

But the art of storytelling, that oral tradition, did continue and became the sole conduit of knowledge about those glory days. The local bards were the repository of cultural memory in the absence of books and writing, and their role was highly respected and honored by all. Young apprentices who had good memories would study under the old bards, learning the ancient poems, and thus would carry on the tradition, sometimes adding to, or elaborating on, the old inherited tales, but as the evidence suggests, never forgetting or dropping the old stories.

Hundreds of years after the Dorian invasion, late in the Dark Ages, roughly around 800 or 750 B.C., Homer was one of those bards. According to ancient tradition—and there is no evidence about him except tradition and his stories— he was born and lived in Ionia (the west coast of what the Romans would call Asia Minor and is part of modern-day Turkey), was blind, and composed the Iliad and Odyssey and perhaps some other works. The two great epics are different enough in theme and spirit that some later critics have suggested that a different poet wrote the Odyssey , but the ancient tradition attributed both poems to Homer, and there

is no good reason to doubt it. All the evidence suggests that Homer’s two poems are the product of the tradition he had inherited of a great many carefully memorized poetic stories and fragments of stories about the Mycenaean kings and their armies and exploits, especially the war against Troy, and about the gods they believed had made the world and involved themselves in it. But the poems are also a product of his own genius in putting together that received material into brilliant forms, both by reassembling the received material and by adding his own elaborations. There were other bards like him, and there were many other poems circulating, but most of those poems have been lost and only tantalizing fragments remain to us.

The length of the two poems suggests the astonishing power of the bards’ memories. The two poems together constitute at least thirty hours of material recited aloud, and every bard would have memorized vastly more material than that. Social anthropologists in the first half of the twentieth century proved beyond a doubt that this was not only possible but was still happening in the twentieth century. Some went to the mountainous regions of the Balkans (the area northwest of Greece) and found villages remote from the rest of the world, without modern technologies like electricity, which had bards who would regularly entertain the villagers with very long epic poems about long-past events of the region, poems that would go on for hours, entirely from memory. Similarly, bards like this were found in the back hills of Ireland before World War II, with the same role in their villages. 9

9 On a very sad note, after the second World War, those anthropologists returned to one of these Irish villages and discovered that electric lines had been run to the village and the people, in a fit of misguided generosity, had given the old bard a television set, and he had forgotten nearly all of the old stories. An unimaginable quantity of old traditional stories and knowledge had

Not long after Homer, perhaps in the late eighth century BC or in the seventh, an alphabet was introduced to Greece from Phoenicia, and writing returned, (which is partly why the dark ages are considered to have ended around this time). The two poems were finally written down, probably in the vicinity of Athens. From then on, the form of the poems were more or less fixed, though with many minor variations, as they were copied and recopied (and later printed) and exhaustively studied and commented on as scholars attempted to discover the exact original wording of the texts.

In spite of the fact that the poems were committed to writing, they were still always recited orally and publicly. (For more on this oral and public aspect of the poem, see Section 5, “The Form and Context of Homeric Epic.”) Professional reciters of epic poetry, called “rhapsodes” and “Homeridae” carried on the oral tradition, reciting sections of Homer’s epics and other poetry at the great festivals in Athens and other places until well after the Greeks fell under the domination of the Macedonians in the fourth century BC.

The poems contain elements of real history, though there has always been tremendous controversy over which parts are historically accurate, and which are invented by Homer (or by those he inherited the stories from), which he assembled into the Iliad . There is no doubt that there was a real war at Troy involving the Mycenaeans (Homer’s Achaians), probably early in the twelfth century BC, just before or around the time of the Dorian invasion, and that many of the heroes named in the poems are based on real men and places. The city of Troy itself was excavated10 in been lost forever.

10 It had many layers, showing that the city had existed for well over a thousand years even before the Trojan War, being periodically destroyed and

NOTE:

The preview of the introductory material ends here to leave room in this preview of the text itself.

Maps of the Odyssey

FLOORPLAN OF A MYCENAEAN PALACE COMPLEX

The palace complex of a Mycenaean kingdom, such as have been excavated at Mycenae and Pylos, was the heart of the kingdom and always followed a pattern involving a central room called the megaron or great hall with a columned entrance and a forecourt leading into it. There was a series of smaller rooms surrounding these main spaces, serving as storerooms for food, wine, and oil, and as bedchambers, offices, archives, workshops, baths, wardrobes, armories, and hallways. It was common to have a second floor. Beyond these rooms were workshops, animal sheds, and gear and fodder storage. The complex was built on a hilltop commanding a view of the countryside and was surrounded by massive walls with impressive entrance gates to intimidate invaders, and watchtowers on nearby hills gave warnings via signal fires. The complex had a secure water supply such as a well within the walls. The people of the kingdom occupied farms and villages around the palace complex and could take refuge in the palace complex in case of invasion. The palace complex was located near a harbor since the Mycenaeans were strongly oriented toward the sea and sea travel, the mountainous topography of Greece making overland travel difficult.

Megaron, or Great Hall—see the description for Map 8.

Forecourt—see the description for Map 7.

Entrance Gate

Staircase

Private Chamber—Penelope spends time here with weaving and other pastimes and comes down the staircase to talk to the suitors. Her bedchamber, though, was likely on the ground floor as the description by Odysseus of crafting one post of their bed from a rooted tree trunk would not work with a second floor bechamber.

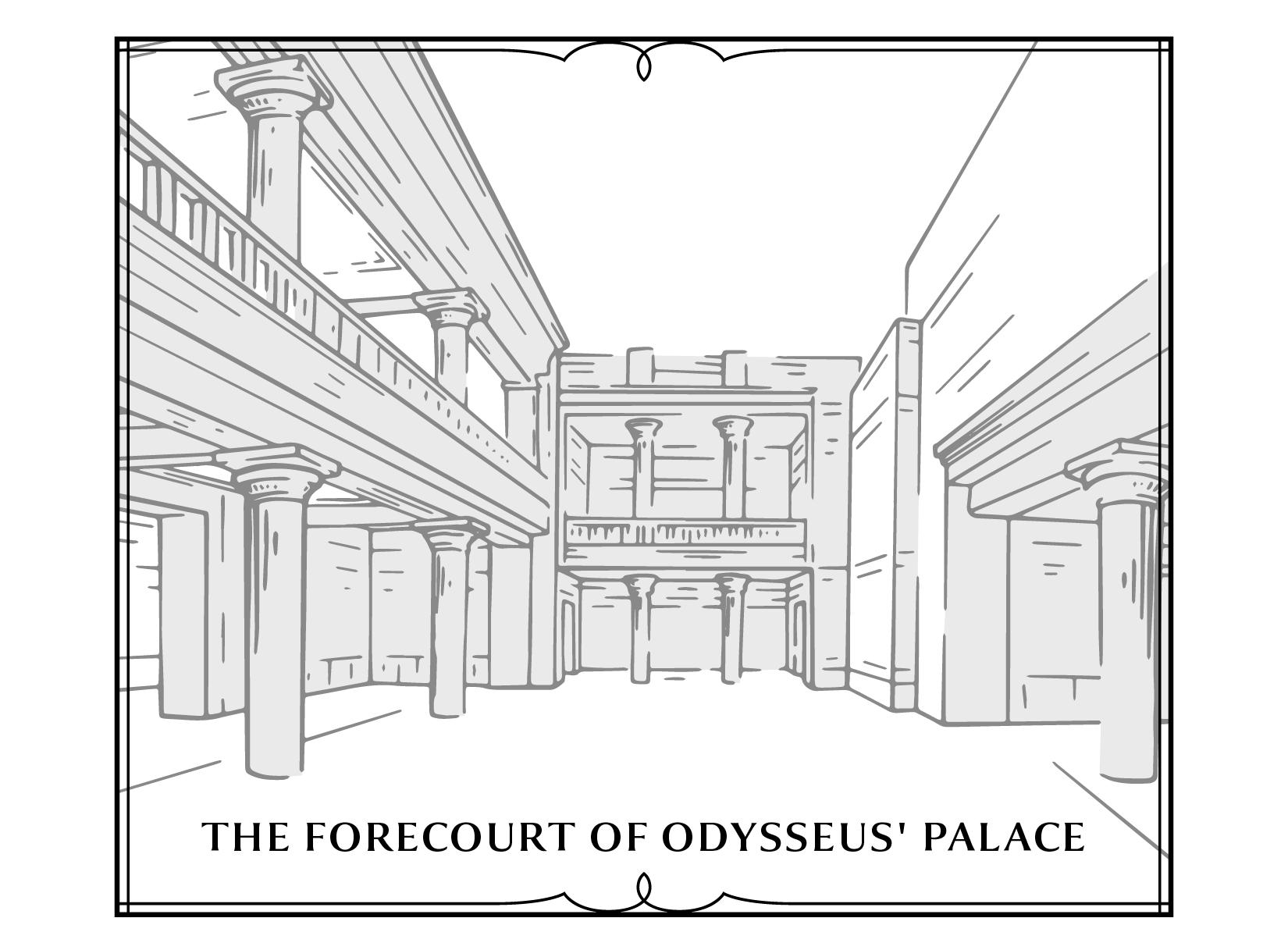

THE FORECOURT

The forecourt with its entrance gate leading into the megaron is the location of the action in the middle of Book 17 where Odysseus sees his old dog Argos lying on a dungheap outside the entrance gate, and again of the action at the beginning of Book 18 where Odysseus knocks out the arrogant old beggar Iros and drags him outside the palace. This forecourt may sometimes have been open to the sky but it may also have been roofed over. Its construction would be similar to that of the megaron, described in Map 8.

THE MEGARON, OR GREAT HALL

This room was at the heart of the palace complex and was the center of palace life in a Mycenaean kingdom. Here the king received visitors and heard news and supplications and here great feasts, religious and political ceremonies took

place, but this was also a place for social gathering where members of the community would visit, play board games, exchange gossip, and generally pass the time. At the center of the rectangular room was a great circular hearth surrounded by four Minoan style pillars (tapering in diameter from larger at the top to smaller at the bottom, the reverse of later classical Greek columns), and above this hearth was an oculus, or opening in the roof, to allow smoke to escape. The walls were sometimes of stone but often of mud brick and timbers—a sort of wattle and daub construction. The roof was supported by heavy beams, and the floor was a type of concrete or flagstones. The wood elements in the walls and room were vulnerable to fire and they are absent in the excavations of the ruins by modern achaeologists so little is know about the walls and especially the roofs. The king’s throne was set against one wall, but again this was a “throne room” in the usual sense; it served many central social functions.

Most of the action in the first two books and the entire second half of the Odyssey takes place in the megaron of Odysseus’ palace on Ithaka, and much of the action in Books 7 and 8 take place in the megaron of King Alkinoös of the Phaiakians on the island of Scheria, where Odysseus also tells his adventures in Books 9–12.

THE ODYSSEY

Homer Invoking the MuseBook I: Athene Visits Telemachos

The Council of the Gods

Tell me, Muse, about the man of many turnings,1 who wandered far and wide, after he had sacked the sacred

1 The Greek word is polytropos , seen as ambiguous since ancient times, referring either to Odysseus’ resourceful mind or to his geographical wanderings in his journey home or to both. Most scholars, ancient and modern, take it in the first sense. But a number of early church fathers use polytropos in spiritual writings to refer to a distracted, unfocused mind, which only Christ can make monotropos —whole and undivided ( Fifty Spiritual Homilies of Pseudo-Macarius , Classics of Western Spirituality, pg 287). Hebrews 1:1 in the New Testament says that of old, God spoke to the fathers by the prophets “polymeros kai polytropos ”—“at many times and in many ways ”—but the second verse goes on to say that “[God]…hath in these last days spoken to us by his Son…” “With the coming of the Only One into your heart, plurality vanishes, says Basil the Great,” (Colliander, Way of the Ascetics , Ch. 18. I owe this last observation to my friend

citadel of Troy. Many were the men whose cities he saw and whose minds he learned, and many the woes he suffered in his heart upon the deep sea, striving for his own life and the return of his companions. Even so he could not save his companions, though he desired it greatly, for they perished through the blindness of their own hearts, the fools, who devoured the oxen of Helios, son of Hyperion, 2 and the god took away from them their day of returning. Of all these things, goddess, daughter of Zeus, from wherever you have heard them, tell them now to us.3

Now all the rest,4 as many as fled from sheer destruction, were at home and had escaped both war and the sea, but Odysseus only, longing for his wife and his homeward way, was held by the lady nymph Kalypso, 5 the lovely goddess, in her hollow caves, longing to have him for her lord. But now when

Jeff Moss). These early Christian uses of the word add to the ambiguity and so to the depth and richness of the Odyssey and its hero from the very first line.

2 Helios is the sun god and Hyperion, a Titan, is his father, so I have translated it that way in this line. But often in Homer, as is clear a few lines below, Hyperion is just another name for the sun god. I’ve deliberately retained the ambiguity; as with polytropos it’s part of what makes Homer such a delight.

3 In the Greek text, this paragraph is ten lines of poetry and is the prooimium ( exordium in Latin), the introduction to the poem, introducing the hero, the clever Odysseus, and the main theme, his return home to Ithaka after ten years of war and nearly ten more years of wandering the Mediterranean lands, and his blamelessness regarding the loss of his men. The prooimium of the Iliad is the first seven lines.

4 That is, the rest of the Achaians (Greeks) who had been at the Trojan War.

5 This is of course Kalypso, who appears in Book 5. Here Athene says Kalypso is the daughter of Atlas (who holds up the sky), but in the Theogony of Hesiod (a younger contemporary of Homer) she is the daughter of the Titans Okeanos and Tethys, brother and sister offspring of Uranos (sky) and Gaia (earth). She is a nymph, a minor female nature deity, who lives on the island of Ogygia, which has been located by ancient and modern scholars in various places around the Mediterranean. See Map 2.

the year had come, in the round of the seasons in which the gods had ordained that he should return home to Ithaka, not even then was he free of his troubles or back with his loved ones. But all the gods had pity on him except Poseidon, who raged continually against godlike Odysseus, until he came to his own country.

But Poseidon had now departed for the distant Ethiopians,6 who are divided in two, the remotest of men, some living where Hyperion sinks and some where he rises. There he waited to receive the great sacrifice of bulls and rams, there he rejoiced sitting at the feast, but the other gods were gathered in the halls of Olympian Zeus. Then among them the father of gods and men began to speak, for he thought in his heart of noble Aigisthos, whom the son of Agamemnon, far-famed Orestes, slew. Thinking about him, he spoke out among the Immortals, “Look now, how vainly mortal men blame the gods! For they say evil comes from us, but it is they who bring upon themselves, through the blindness of their own hearts, sorrows beyond what is ordained. Even lately, Aigisthos, beyond what was ordained, took to himself the wife of the son of Atreus and killed her lord on his return, and he did it with sheer doom before his eyes. For we had warned him by sending Hermes the sharp-sighted, the slayer of Argos,7 that he should neither kill the man nor court his

6 This is not the people occupying the modern nation of Ethiopia. In Homer they generally are understood to live far to the East or far to the West (‘some where Hyperion sinks and some where he rises”). Throughout antiquity they had the reputation from Homer onward as the most righteous of all men, loved by the gods, and we must keep this background in mind when considering the New Testament episode of Philip and the Ethiopian (Acts 8:26).

7 Argos was the hundred-eyed giant which Hera set as guard over Io, the beautiful young woman with whom Zeus had fallen in love but turned into a heifer to hide her from Hera. Hera asked Zeus for the beautiful heifer, and Zeus couldn’t refuse. Hera then set Argos to keep Zeus away from Io, but Zeus had

wife, for the son of Atreus would be avenged by the hand of Orestes as soon as he came of age and longed for his own country. So spoke Hermes, yet he did not persuade the heart of Aigisthos, for all his good intention, and now he has paid the price for it all.”

And the goddess, grey-eyed Athene, answered him, saying, “Our father, son of Kronos, throned in the highest, that man certainly suffered a death that he earned; let all who do such deeds perish the same way! But my heart is torn for wise Odysseus, that unfortunate one, who far from his friends suffers affliction for so long on a wave-washed island, the navel of the sea, a wooded island, and in it a goddess8 has her dwelling, the daughter of malevolent Atlas, who knows the depths of every sea and upholds the tall pillars which keep earth and sky apart. It is his daughter who holds the unfortunate man in sorrow, and always with soft and soothing tales she charms him to forgetfulness of Ithaka. But Odysseus, longing to see but the smoke rising upward from his own land, has a desire to die. As for you, your heart does not care at all, Olympian! Did not Odysseus, by the ships of the Argives, freely offer sacrifices to you in the wide Trojan land? Why then are you so angry with him, O Zeus?”

And Zeus, the Cloud-Gatherer, answered her and said, “My child, what word has escaped the door of your lips? How could I forget divine Odysseus, who in understanding is beyond mortals and more than all men has sacrificed to the deathless gods who keep the wide heaven? No, it is Poseidon, the Encircler of the Earth, who has been angry continually with undying anger because of the Kyklops whose

Hermes distract and then kill Argos. The Greek title for Hermes is argeiphontes or “Argos-Slayer.” 8 Kalypso.

eye he blinded, godlike Polyphemos whose power is greatest over all the Kyklopes. His mother was the nymph Thoösa, daughter of Phorkys, lord of the barren sea, and in its hollow caves she lay with Poseidon. From that day on, Poseidon the Earth-Shaker does not indeed destroy Odysseus but drives him wandering far from his own country. But now let us all take good counsel here about his return, so that he may be got home; so Poseidon will let go of his anger, for in no way will he be able to strive alone against all the deathless gods.” Then the goddess, grey-eyed Athene, answered him and said, “Our father, son of Kronos, throned in the highest, if indeed this plan is now pleasing to the blessed gods, that wise Odysseus should return to his own home, then let us quickly send Hermes the Messenger, the slayer of Argos, to the island of Ogygia. There with all speed let him declare to the lady of the braided tresses our sure counsel, the return of patient Odysseus, so that he may come to his home. But as for me, I will go to Ithaka that I may rouse his son all the more, planting strength in his heart, to call an assembly of the long-haired Achaians and speak out to all the suitors who continually slaughter the sheep of his thronging flocks and his cattle with trailing feet and shambling gait. And I will guide him to Sparta and to sandy Pylos to seek news of his beloved father’s return, if perhaps he may hear of it, and so that he might gain a good reputation among men.”

She spoke and bound beneath her feet her lovely, immortal, golden sandals that carried her over both the wet sea and the endless land, swift as the breath of the wind. And she seized her mighty spear, clad with sharp bronze, weighty and huge and strong, with which she subdues the ranks of heroes, those with whom she, the daughter of the mighty father, is angry.

Athene Visits Telemachos

Then from the heights of Olympos she came flashing down, and she stood in the land of Ithaka at the entry of the gate of Odysseus on the threshold of the courtyard, holding in her hand the spear of bronze, in the appearance of a stranger, Mentes the captain of the Taphians. And there she found the lordly suitors; they were taking their pleasure at draughts9 in front of the doors, sitting on hides of oxen, which they themselves had slaughtered. And some of the attendants and the servants were mixing wine and water for them in bowls, and some were washing the tables with porous sponges and setting them, and others were carving meat in great quantities.

And godlike Telemachos was far the first to observe her, for he was sitting with a heavy heart among the suitors, imagining his noble father, if perhaps he might come from somewhere and scatter the suitors throughout the palace and gain honor and establish rule among his own possessions. Thinking about this as he sat among the suitors, he saw Athene, and he went straight to the outer porch, for he thought in his heart that it was shameful that a stranger should stand long at the gates and, stopping near her, he clasped her right hand and took from her the spear of bronze and lifted his voice and spoke winged words to her:

“Greetings, stranger. You will be kindly treated with us, and afterward, once you have eaten, you may tell us what you need.”

9 This is the British word for what Americans call checkers, a board game which, in variations, has been played for thousands of years from the ancient Mesopotamians, Egyptians, and Greeks to the Romans and medieval Europeans.

With that he led the way, and Pallas Athene followed. And when they were inside the spacious house, he set her spear which he carried against a tall pillar in the polished spear-stand where many other spears stood also, those of Odysseus of the stout heart, and he led the goddess and seated her on a beautifully carved chair and spread a linen cloth under it, and beneath was a footstool for the feet. For himself he placed an inlaid seat close by, away from the crowd of the suitors, lest the stranger should be disturbed by the noise and should be put off from the meal, having come among arrogant men, but also so that he might ask him about his father who was gone from his home. Then a handmaid carried water for washing hands in a noble, golden pitcher and poured it out over a silver basin to wash with and pulled next to them a polished table. And a dignified maid brought wheat bread and set it nearby and laid on the table many delicacies, freely giving whatever she had close at hand. And a carver lifted and placed beside them platters of various kinds of meats and near them he set golden bowls, and an attendant walked back and forth pouring wine for them.

Then the haughty suitors came in, and they sat down in rows on chairs and on high seats, and attendants poured water on their hands, and maidservants piled wheat bread by them in baskets, and servants filled up the bowls with drink, and they stretched out their hands to the good food spread before them. When the suitors had satisfied the desire for food and drink, they thought of other things, the song and dance, for these are the crown of the feast. And an attendant placed a beautiful lyre in the hands of Phemios, who was bard for the suitors against his will. As he touched the lyre, he lifted up his voice in sweet songs.

But Telemachos spoke to grey-eyed Athene, holding his head close to her so that those others could not hear: “Dear stranger, will you indeed be angry at what I will say? Those men truly care for such things as these, the lyre and song, thoughtlessly, as those who consume the livelihood of another without repayment, of that man whose white bones, it may be, lie rotting in the rain on the mainland, or the waves tumble them in the salt sea. If only these men were to see him returned to Ithaka, they would all pray more for greater speed of foot than for gain of gold and fine clothing. But now he has perished, a terrible fate, and there is no comfort for us, no, even though any earthly man should say that he will come again. Gone is the day of his returning! But tell me this, and tell me everything clearly: who are you of the sons of men, and where are you from? Where is your city and where are those who begot you? On what kind of ship did you come, and how did sailors bring you to Ithaka, and who did they claim to be? For in no way do I think that you came here by land. And tell me this truthfully, that I may know for certain whether you are a newcomer or whether you are a familiar guest of the house, since many strangers used to come to our home because my father had traveled much among men.” Then the goddess, grey-eyed Athene, answered him: “I will plainly tell you everything. I call myself Mentes, son of wise Anchialos, and I rule the Taphians, lovers of the oar. And now I have come to shore, as you see, with ship and crew, sailing over the wine-dark sea to men of strange speech, even to Temesa, in search of copper, and my cargo is shining iron. And my ship is lying there toward the upland, away from the city, in the harbor of Rheithron beneath wooded Neïon. And we declare ourselves to be friends of one another and from friendly houses from a long time past. If you

desire assurance, go ask the old man, the hero Laertes,10 who they say does not come to the city any more but far away toward the upland suffers grief with an ancient woman for his handmaid, who places food and drink near him whenever weariness takes hold of his limbs as he hobbles along the knoll of his vineyard plot. And now I have come, for indeed I was told that he, your father, was among his people, but the gods obstruct his journey. For noble Odysseus has not yet perished on the earth, but I think still lives and is kept on the wide deep in a wave-washed island, and perhaps rough, wild men keep him harshly against his will. But now indeed I will utter my word of prophecy, as the Immortals bring it into my heart, and I think it will be accomplished, though I am no prophet, nor am I skilled in the omens of birds. After this time he will not be far from his beloved country for long, not even if bonds of iron bind him; he will plan a way to return, for he is a man of many devices. But tell me this plainly, whether indeed, as tall as you are, you are sprung from Odysseus. Truly your head and bright eyes are wonderfully like his, for many times we have talked together before he set sail for Troy, where the others too, the bravest of the Argives, went in their hollow ships. From that day onward I have not seen Odysseus, nor has he seen me.”

Then wise Telemachos answered her and said, “I will plainly tell you everything. My mother indeed says that I am his; as for me I do not know, for no man ever knew his own descent himself. If only I had been the son of some blessed man whom old age overtook among his own possessions! But they say that I am the son of that man who is the most unfortunate of mortals, since you question me about that.”

Then the goddess, grey-eyed Athene, spoke to him and said, “Surely the gods have not ordained a nameless lineage for you in days to come, since Penelope bore such a noble man as you. But tell me this plainly: what feast, or rather, what dissipation is this? What do you have to do with it? Is it a clan drinking or a wedding feast, for this is not a banquet where each man brings his share. In this way, swollen with insolence, they seem to me to revel wantonly throughout the house, and any man might well be angry to see so many deeds of shame, if any wise man came among them.” Then wise Telemachos answered her and said, “Sir, since you question me about these things and inquire about them, our house was once rich and honorable, while that man was still among his people. But now the gods have willed it otherwise, with evil intent, for they have made him pass utterly out of sight like no one ever before. Indeed, I would not grieve so much even for his death, had he fallen among his companions in the land of the Trojans or in the arms of his friends when he had wound up the war. Then the whole Achaean host would have built him a barrow, 11 and he would have won great glory even for his son in after days. But now the spirits of the storm12 have swept him away into obscurity. He is gone, lost to sight, lost to knowledge, but for me he has left grief and lamentation, nor is it for him alone that I mourn and weep, since the gods have caused other terrible sorrows for me. For all the noblest princes in the isles, in Doulichion

11 Burial mound (cf. the mound heaped up for Patroklos in Iliad 23).

12 The word here is often translated as “storm winds” (e.g., Lattimore), but it certainly refers to personified winds, whose genealogy is given in Hesiod’s Theogony , and this would have been recognized by Homer’s (and later) audiences. Many of what we take as merely material elements of nature in Homer and other early Greek literature (especially poetry) were understood by the ancient Greeks as animated and personified.

and Same and wooded Zacynthus, and all who lord it over rocky Ithaka, all these court my mother and waste my house. But as for her, she neither refuses the hated marriage nor has the heart to end the matter; so they devour and waste my house, and before long they will make havoc of me too.” Then in great displeasure Pallas Athene spoke to him: “What a shame! Surely you are greatly in need of far-off Odysseus to stretch forth his hands upon the shameless suitors. If only he could come now and stand at the entrance of the gate with helmet and shield and two spears, as mighty a man as when I first saw him in our house drinking and rejoicing at that time he came up out of Ephyra from Ilus, son of Mermerus! For Odysseus had gone there on his swift ship to seek a deadly drug, that he might have it to smear on his bronzeshod arrows, but Ilus would in no way give it to him, for he was in awe of the gods who live forever. But my father gave it to him, for he loved him greatly. If only Odysseus might in that same strength deal with the suitors; they would all have a swift fate and a bitter wedding! However, these things surely lie on the knees of the gods, whether he shall return or not and take vengeance in his halls. But I urge you to consider how you might drive out the suitors from the hall. Come now, listen and heed my words. Tomorrow call the Achaean lords to the assembly and announce your words to all and take the gods as witness. Bid the suitors to disperse, each one to his own place, and as for your mother, if her heart is inclined to marriage, let her go back to the hall of that mighty man her father, and her people will furnish a wedding feast and arrange for the many courtship gifts that should go with a dearly beloved daughter. And to you I will give a word of wise counsel, if you will listen. Outfit a ship, the best you have, with twenty oarsmen and travel to inquire about your father who is so far off, if perhaps anyone will tell you anything,

or if you may hear the voice of Zeus, which above all brings news to men. Go first to Pylos and inquire of noble Nestor, and from there to Sparta to Menelaos of the fair hair, for he came home last of all the well-armored Achaians. If you hear news of the life and the return of your father, then indeed you can endure the troubles for another year. But if you hear that he is dead and gone, then return to your own dear country and pile his burial mound and over it serve the burial rites, as many as is fitting, and give your mother to a husband. But when you have done all this, then consider in your mind and heart how you might slay the suitors in your halls, whether secretly or openly, for you should not continue thinking as a child, since you are no longer of the age for it. Have you not heard what glory noble Orestes got for himself among all men because he killed the slayer of his father, treacherous Aigisthos, who killed his famous father? And you too must be courageous, my friend, for I see that you are noble and tall, so that even men not yet born will praise you. But now I will go down to the swift ship and to my men, who I think are very impatient waiting for me. Take heed and listen to my words.” Then wise Telemachos answered her, saying, “Sir, indeed you speak these things from a friendly heart, as a father to his son, and I will never forget them. But now I beg you to stay here, even though you are eager to be gone, so that after you have bathed and enjoyed yourself, you may make your way to your ship joyful in spirit, with a costly and very noble gift, to be a remembrance of my giving, such as dear friends give to friends.”

Then the goddess, grey-eyed Athene, answered him: “Do not keep me any longer, for I am eager to be on my way. But give to me whatever gift your heart urges you when I come back again for me to carry home; bring out from your stores a most noble gift, and you will receive its worth in return.”

So grey-eyed Athene spoke and departed, and like an eagle of the sea she flew away, but in his spirit she planted strength and courage and brought to his mind his father even more than before. And he saw and was amazed, for he realized that it was a god, and soon he went back among the suitors, a godlike man.

Telemachos Rebukes the Suitors

Now the famous bard was singing to the suitors, and they sat listening in silence, and his song was of the pitiful return of the Achaians,13 that Pallas Athene laid on them as they came back from Troy. And from her upper chamber the daughter of Ikarios, wise Penelope, heard the glorious music, and she went down the high stairs from her chamber, not alone, for two of her handmaids kept her company. Now when the fair lady had come to the suitors, she stood by the pillar of the well-built roof holding up her shining veil before her face, and a faithful maiden stood on either side of her. Then she began weeping and spoke to the divine bard:

“Phemios, since you know many other songs for mortals, deeds of men and gods, which bards rehearse, sing of these as you sit by them and let them drink their wine in silence, but stop this pitiful tune that continually wastes my heart within my breast, since to me beyond all women has come a sorrow without comfort. So dear a head do I long for

13 Compare this with the songs of Demodokos in Book 8, which have the same themes. The stories of the Trojan War and the nostoi (homecomings) of the Achaians have already circulated widely throughout the eastern Mediterranean by this time.

in constant memory, that man whose fame is praised everywhere from Hellas to the middle of Argos.”

Then wise Telemachos answered her and said, “Mother, why do you refuse to let the glorious bard gladden us as his spirit moves him? It is not bards who are at fault, but rather Zeus, I think, who is at fault, for he gives to all men, who live by bread, what he will. As for the bard, do not blame him if he sings about the unfortunate travels of the Danaans, for men always prize that song the most which rings newest in their ears. But let your heart and mind bear up to listen, for Odysseus is not the only one who lost the day of his homecoming in Troy, but many others also perished. Nevertheless, go to your chamber and attend to your tasks, the loom and spindle, and urge your handmaids to work at their tasks. Speech will be for men—for all, but for me most of all, for I am the lord of the house.”

Then in amazement she went back to her chamber, and she laid up the wise saying of her son in her heart. She ascended to her upper chamber with the women who were her handmaids and then wailed for Odysseus, her dear lord, till grey-eyed Athene cast sweet sleep upon her eyelids.

Now the suitors clamored throughout the shadowy halls, and each one uttered a prayer to be her bedfellow. And wise Telemachos spoke out among them:

“Suitors of my mother, men outrageous beyond measure, let us feast now and make merry and let there be no brawling; it is a good thing to listen to a bard such as this one, like the gods in his voice. But in the morning let us all go to the assembly and sit down, so that I may announce my words clearly: that you leave these halls and busy yourselves with other feasts, consuming your own wealth, going in turn from house to house. But if you think this a likelier and a better thing, that one man’s goods should perish without re-

payment, then waste it as you please, and I will call upon the everlasting gods, if perhaps Zeus may grant that revenge be made; then you would perish within these halls without making atonement.”

So he spoke, and all who heard him bit their lips and marveled at Telemachos, because he spoke boldly.

Then Antinoös, son of Eupeithes, answered him: “Telemachos, indeed the gods themselves have taught you to be so proud and bold in your speech. May the son of Kronos never make you king in sea-encircled Ithaka, though it is your inheritance by right!”

Then wise Telemachos answered him and said: “Antinoös, will you indeed be angry at the word that I will speak? Yes, at the hand of Zeus I would be eager to take this thing upon me. Do you say that this is the worst thing that can happen to a man? No, it is not a bad thing to be a king; the house of such a man quickly grows rich, and he himself is held in greater honor. However, there are many other kings of the Achaians in sea-encircled Ithaka, both young and old; one of them will surely obtain this kingship since noble Odysseus is dead. But as for me, I will be lord of our own house and servants, which noble Odysseus won for me with his spear.”

Then Eurymachos, son of Polybos, answered him, saying, “Telemachos, surely it lies on the knees of the gods what man is to be king over the Achaians in sea-encircled Ithaka. But may you keep your own possessions and be lord in your own house! May no one ever come to force violently from you your wealth against your will while Ithaka still stands. But I would ask you, friend, about the stranger—where is he from, and of what land does he claim to be? Where are his people and his native fields? Does he bring some news of your father on his journey, or does he come to conduct some business of his own? So suddenly he started to leave, and then he was

gone, and he did not linger so we could know him—and yet he seemed to be no ordinary man to look upon.”

Then wise Telemachos answered him and said: “Eurymachos, surely the day of my father’s returning has passed. Therefore, I do not put faith in news any more, no matter where they come from, nor do I care for prophecies, about which my mother has inquired from the mouth of a soothsayer, when she has invited him to the hall. But as for that man, he is a friend of my house from Taphos, and he says he is Mentes, son of wise Anchialus, and he is lord over the Taphians, lovers of the oar.”

So spoke Telemachos, but in his heart he had recognized the immortal goddess. Now the suitors turned to the dance and the delightful song and made merry and waited till evening should come. And as they made merry, evening came upon them. Then each one went to his own house to lie down to rest.

But Telemachos, where his chamber was built high up in the noble court, in a place with a wide view, went to his own bed, pondering many thoughts in his mind, and with him went trusty Eurykleia and carried burning torches for him. She was the daughter of Ops, son of Peisenor, and Laertes bought her once upon a time with his wealth, while she was still in her youth, and paid twenty oxen for her. And he honored her as much as he honored his beloved wife in the halls, but he never lay with her, for he avoided the anger of his lady. She went with Telemachos and carried the burning torches for him, and of all the women of the household she loved him most, for she had nursed him when he was little. Then he opened the doors of the well-built chamber and sat on the bed and took off his soft tunic and put it in the wise old woman’s hands. So she folded the tunic and smoothed it and hung it on a pin by the jointed bedstead and went away

from the room and pulled the door closed with the silver handle and pulled the bar shut with the leather strap. There, all night long, wrapped in a wool fleece, he meditated in his heart about the journey that Athene had revealed to him.

Book II: Telemachos Calls an Assembly

Telemachos Speaks to the Assembly

Now when rosy-fingered Dawn shone forth early, 14 the dear son of Odysseus got up from his bed and put on his garments and threw his sharp sword over his shoulder, and beneath his smooth feet he bound his noble sandals, and he stepped out from his chamber in appearance like a god.

14 The most famous epithet for Dawn is rhododaktylos eos (“rosy-fingered Dawn”). Rhodo is familiar in “rhododendron,” which means “rosy-tree,” and daktylos is familiar in “pterodactyl,” which means “winged finger.” Often she is also called eos erigeneia , which means “early-rising Dawn.” In Homer she not only rises early to herald the coming of her brother Helios, the sun-god himself, but seems to accompany him across the sky all day, because 1) he is often not even mentioned with her, so she stands for both herself and him, and 2) she often appears in the evening sky as well.