The white paint gangs

The prison directors Henk and Christoff wait to start the tour of the place until I can retrieve my level, wallet and belt from the x-ray scanner. I thread the belt through my pant loops and fasten it tight, then stuff the wallet into my back pocket. ‘Not smart,’ says Christoff, pointing to my pants. ‘That’s just asking for it to be stolen,’ Henk concurs. I move the wallet to my jacket pocket shamefacedly and signal with a nod that I’m ready. The door of the security screening room closes behind us with a soft click.

We’re on the inside but standing in the open air. A host of sparrows is pecking seeds from a freshly planted grassy strip. They’re funny little creatures, with their beady eyes and hopping gait. We head up a wide flight of stairs to a landing about thirty feet high that has a roof supported by a row of columns. It looks like a Greek temple. Down below my feathered friends chirp blithely in the grass. It is much more spacious than I had imagined, with the wind given free rein. I see no sign of the prisoners, however, even though there must be at least seven hundred of them. The first group was brought in last week in vans with bulletproof glass – not all at once, but in stages. I will be drawing among them for five weeks and going home at night, as agreed to with the prison management.

It’s a lovely summer afternoon, no razor wire or hanging power lines in sight. The outer wall, though, is topped by a ring of tubular, light-pink sections made of industrial plastic. They look like plumped up pillows or toys from long ago that aren’t much fun. This soft, colourful aura offers small consolation for prisoners hoping to climb over the wall. The sections are too round and too large to adequately get a hold of; at most, they might become dented. So, any attempt at escape will end on the inside of the wall without even the need for guards.

3

This so-called gentler regime comes across as rather cruel and merciless to me.

Upon reaching the landing, we catch our breath. Witloofstraat and Haachtsesteenweg, which runs between Brussels and Aarschot, are visible in the distance. A camera installed on one of the columns points down at us like an artificial cat’s eye.

‘Is there anywhere the technology doesn’t reach?’ I ask.

‘Everything here is high-tech, but no matter how you slice it, detention is detention. Nothing about that has changed through the centuries,’ Christoff says.

‘Still, this is a radical break from the past,’ I say.

He smiles. ‘We’ll take you to the Atelier, where you’ll see a wide cross-section of our population: swindlers, sex offenders, murderers, muggers, burglars… people of all sorts work there.’ I’m looking forward to meeting them, regardless of what they’ve done in the past.

Christoff casually presses his badge against a flat black box about the size of my wallet. After a few seconds the red flashing light switches to green, followed almost instantaneously by a click and the door unlocks. We enter a cylindrical room completely sealed off from the outside world. The arid smell of dried concrete hangs in the air. This is where the attack animals would have been kept in the old days, back when prisoners were thrown to the lions. My mind conjures bloody images of combatants begging for mercy and lions. Their cat’s eyes are embedded in the walls, nearly invisible and thus all the more dangerous than before. I pretend it doesn’t bother me.

‘There are four more of these locks,’ Christoff says. ‘And at each door we have to wait until the one behind us has closed. Everyone working here runs into these digital walls, losing an hour a day just waiting. Even though it’s planned into the schedule, it still takes tolerance. As we used to say at home, patience and good intentions go a

4

long way.’ ‘That you, of all people, would end up here then,’ I let slip. ‘It is better to do good in a bad world than do good in a world where things are marching along smoothly,’ he replies.

The three of us walk down the long corridor, whose walls are coated in epoxy. The contours of our bodies are reflected in them like blurry ghosts. Nothing sticks to such a finish, as I well know, not even chalk. Henk had warned me about that at our meeting in the container office nearly a year ago and I thought I might have to draw on the ceilings, but those are covered in pipes and fire sprinklers.

It’s hushed in the corridor, except for the sound of our footsteps and a strange ticking noise coming from the pipes every now and then. Could it be a mouse: the only prisoner able to move freely about the building? Witloofstraat was overrun by the little rodents. In fact, Fred had set traps throughout his house to catch them. The critters fled to the neighbours in search of better pastures, with all the related consequences. Fred’s daughter Laurence had her own ideas about the mice and said they were holding meetings in the abandoned building at the edge of the birch grove. I shudder at the thought of the stoic guard there with his red whiskers. How can Laurence think he’s so sweet?

It’s a small miracle I’m being allowed inside the prison with no restrictive measures. I hold the level loosely at my side, as inconspicuously as possible.

5

Christoff opens the door to the Atelier, a concrete factory hall about half the size of an Olympic swimming pool.

Some sixty inmates are seated at long rectangular tables working. ‘On weekdays, production runs from eightthirty in the morning to two-thirty in the afternoon. This is the only place in the country where male and female prisoners aren’t separated,’ Christoff explains. He hands me a badge that will allow me to go out when I want. ‘Just follow the signs with a temple symbol and they’ll lead you to the exit,’ he says, introducing me in the same breath to a sinewy female guard. She has short white hair, a weathered face and a moustache. A strong scent of peppermint hangs in the air around her. Her name is Nicole and I like her right away. The directors mumble something to her in a low voice, then quietly leave the Atelier. ‘Go ahead and take a look around; everything is being monitored,’ she says amicably before assuming her position in a room full of video monitors, behind a thick glass window.

The walls here are not covered in epoxy, so I can draw on them freely. There is a shelving unit in front of one wall, containing clear storage bins full of brightly coloured ring binders and sheets of stickers, but it can easily by pushed aside. A very tall bloke with spiky hair and steel-blue eyes, dressed in a plain white T-shirt and blue jeans, moves the storage bins around with a pallet jack. He’s probably in his sixties but has a youthful look. He chats with a young woman he passes on the way. She has a lean face with an oily sheen to it and looks over at me, a snake lying in wait for a mouse.

A man with a trim beard and reading glasses propped on his nose is seated at a table in the middle of the room with his back turned to the others. With the patience of a saint, he manually stamps page numbers in school notebooks. I get the impression he doesn’t want to be disturbed. The smell of peppermint is pervasive. I

6

notice that the stamp marks don’t always land exactly in the centre of the page but drift about, sometimes crooked or alternately too thick or too thin – all of which makes them a kind of personal handwriting. I watch him with a vague sense of collegiality but can’t think of anything to say. Without even looking at me, he says in a lilting Limburg accent, ‘Watch out, because there are thieves in here.’

Sunlight pours in through the barred windows and ceiling skylights. The bars in the skylight are as thick as those of an elephant cage. All the while, the men and women work at a brutal pace, with the assiduous stamper topping them all. I haven’t seen him look up again from his work since he issued that warning. It’s the first time I’m seeing the regime in action. The hall echoes with a chorus of voices and languages, and the radio plays softly in the background. I pick up bits and pieces about the war in Ukraine, including the news that Russian convicts are being sent to the front lines in exchange for their freedom. It makes my blood run cold.

Here, meanwhile, it feels like there’s no time to waste, the driving principle presumably being that time is money. There is, of course, plenty to be said against that proposition, just like the acoustics of the hall leave much to be desired. But I keep my thoughts to myself, only too grateful that the epoxy terror doesn’t extend to the Atelier.

The inmates treat Nicole with respect. ‘They’re on the prison payroll, just like me,’ she says. ‘I’ve been doing this work for forty years, destined from an early age to be a guard.’ Despite the menial work being performed, such as labelling pharmaceutical products and stamping paper, the atmosphere is not depressing. ‘Working in the Atelier helps keep people from going crazy,’ she points out. ‘The fact is that it makes the days pass by more quickly. It’s a legitimate way of making prison life bearable, and then they’re also better prepared for life outside.’

Her words shed new light on the drive I see in the

7

people around me. The tall bloke stacks the boxes with folders on the pallet jack and wipes the sweat from his brow. His desire for freedom is palpable and it fills the Atelier.

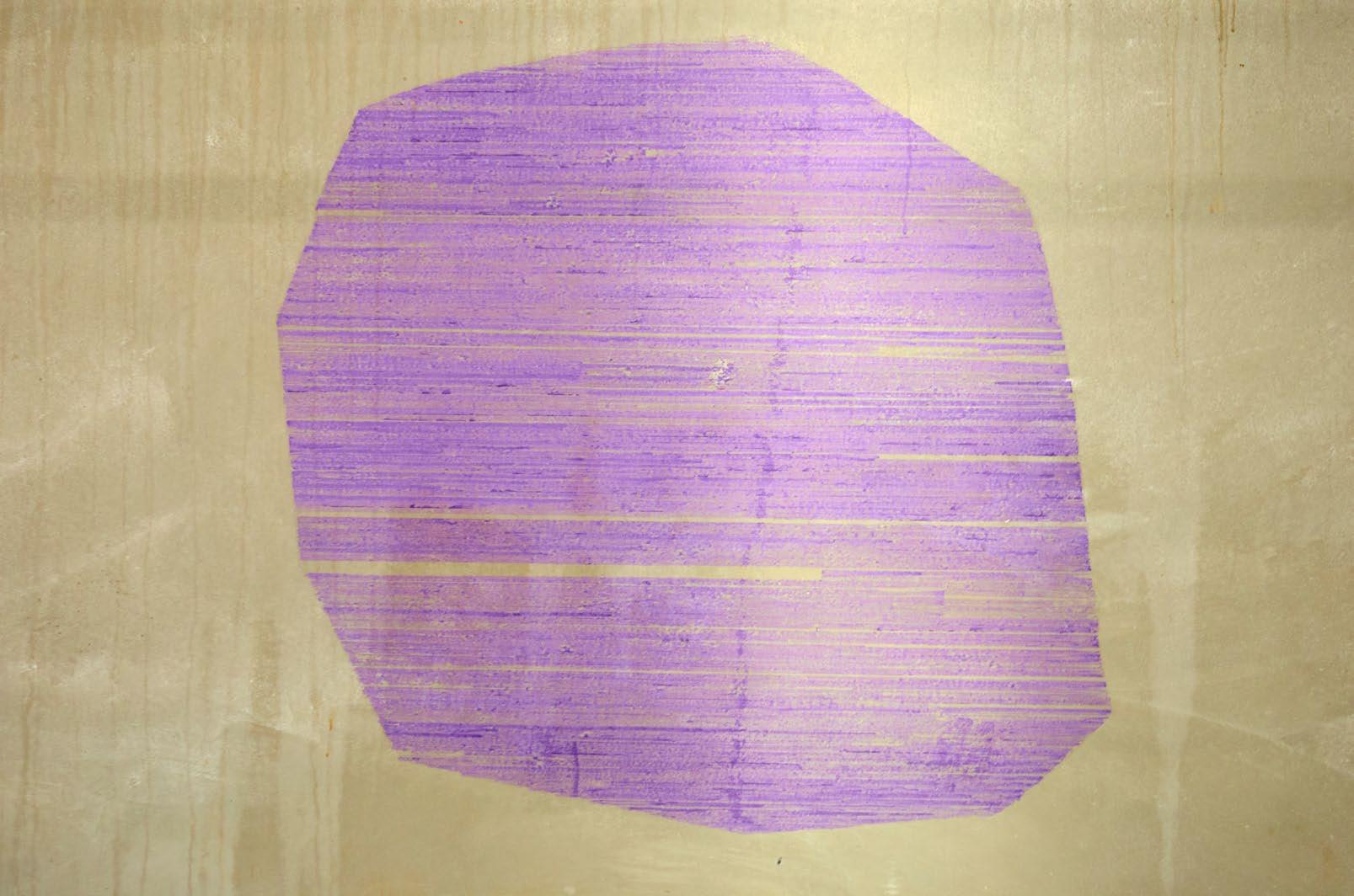

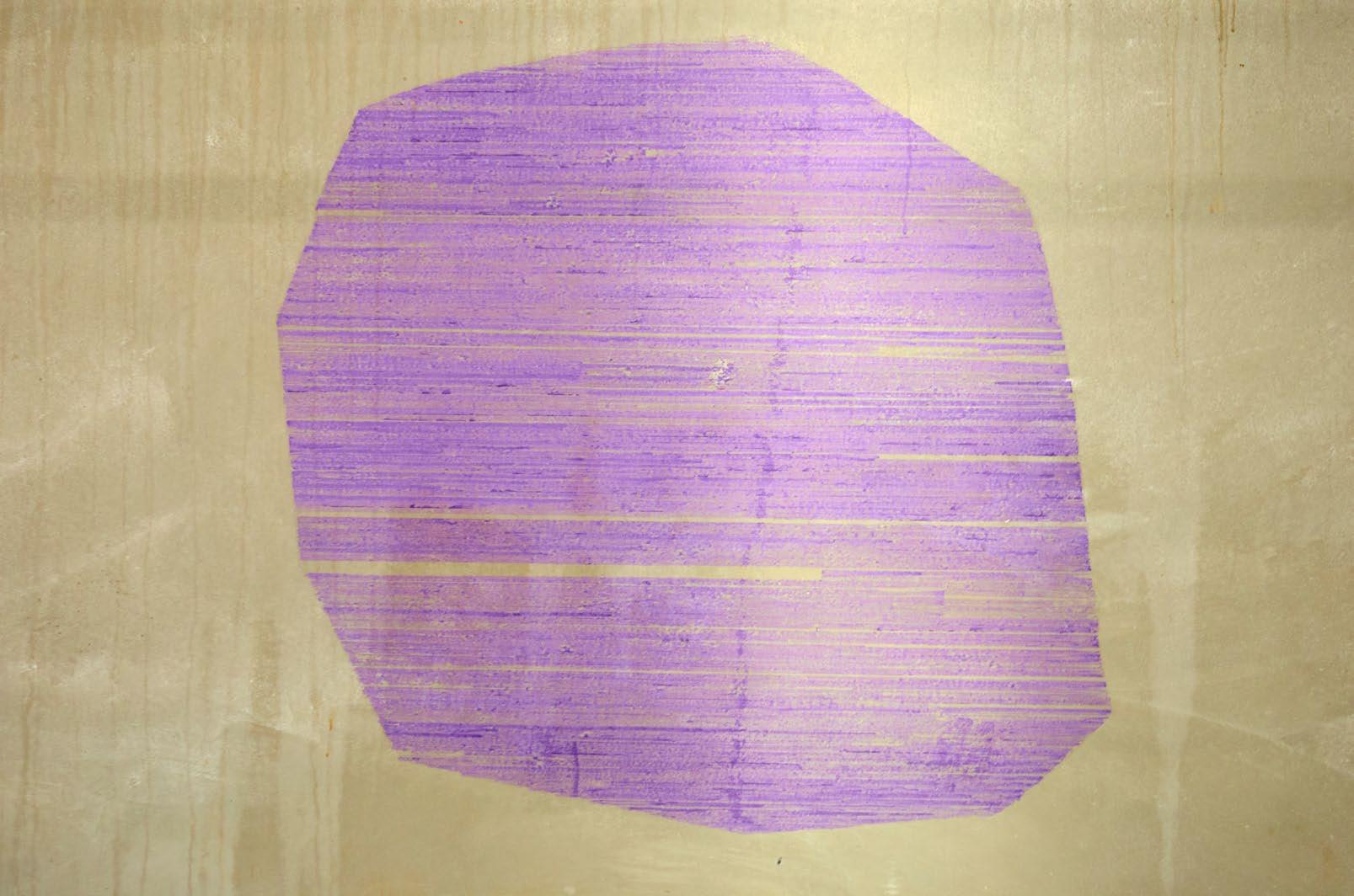

To do well here, I will have to adopt their work pace. This will require a different strategy than drawing on the street, where gaining acceptance generally involves a lot of hanging around or paying people visits. I won’t have a lot of time to think about what to draw. I pull a piece of purple chalk out of my bag, which is not a colour I like much. That increases the risk of failure, but throwing up an initial hurdle for myself is a trick I use to force decisions to be made, to take control of the work and create tension. I soon achieve an unusually high level of concentration, not the least bit distracted; I draw like someone possessed, almost oblivious to what’s happening around me.

8

The prison is filled to the rafters with stories.

9

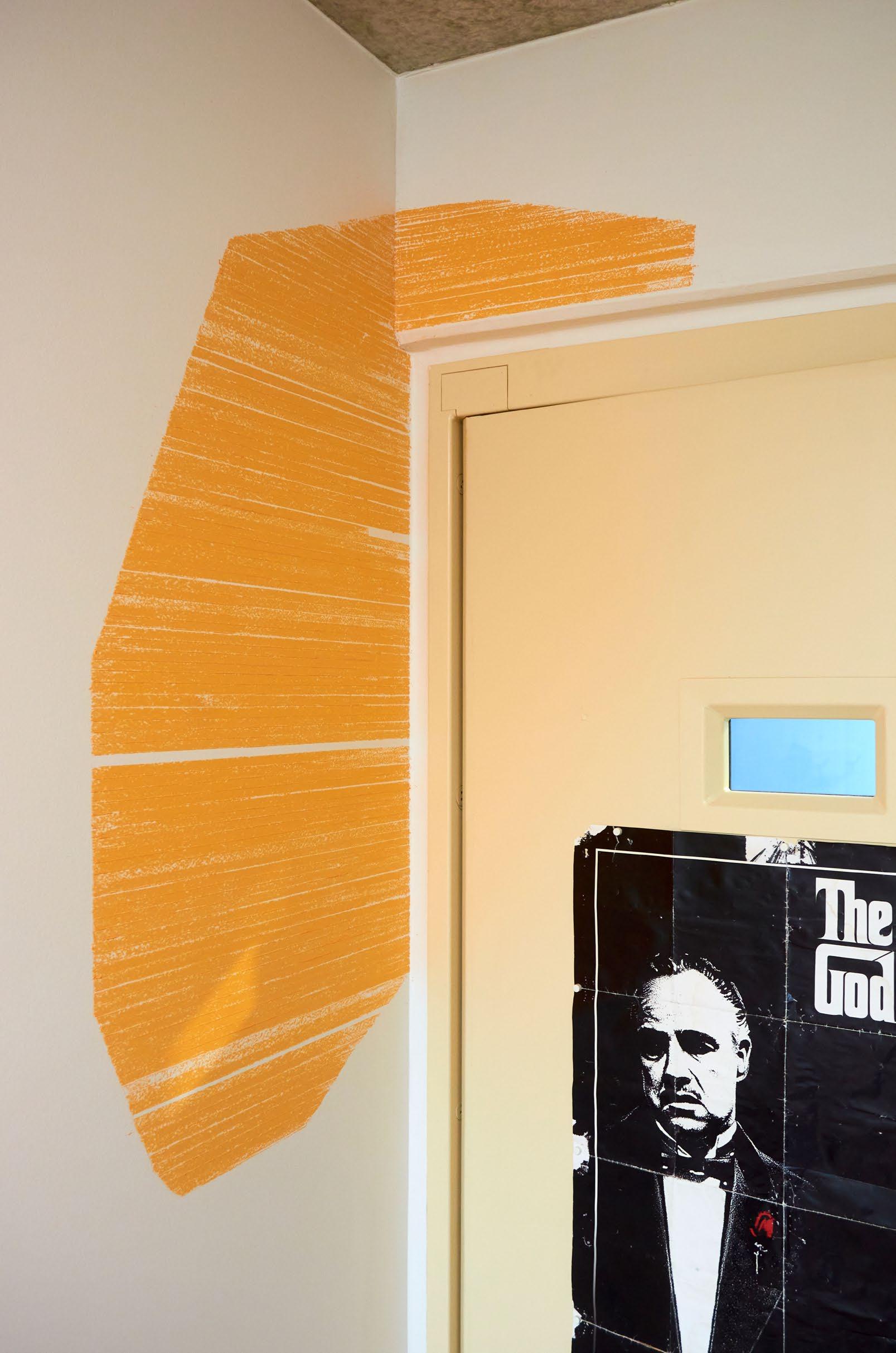

Since spending time in a prison is not easy on anyone, I do the first drawing in a colour that’s not normally my style.

10

Working in groups of six, the inmates wrap stickers around clear tubes about the size of your little finger. They work at a rapid pace, and I manage to hold my own. It’s mostly French and Arabic being spoken, and though my French is better than my Arabic, I’ll still have to step up my game.

11

12

‘Everything okay?’ Nicole asks during the break. I take it as a rebuke for so closely observing the dynamics on the shop floor. Still, she means well and invites me for a cup of coffee. It’s watery slop but I appreciate it for what it is. ‘Where does that strong peppermint smell come from?’ I ask. ‘The tubes contain little globules filled with a liquid that dispels the taste of cigarettes or coffee when taken. You’re smelling the globules that get crushed on the floor – and our fresh breath, of course,’ she answers. ‘At the start of the year, they raised the compensation prisoners receive from seventy-five cents to four euros per hour to boost morale. Since then, more people have been coming to work in the Atelier and production has risen. The more people working here, the stronger the peppermint smell, and the more enjoyable it is in here.’ She smiles. ‘Four euros for such easy work. Isn’t that a bit much?’ I ask. ‘When an inmate is released, an amount like that reduces the risk of recidivism. And they can use it to pay damages they owe,’ she replies.

The man in the white T-shirt trudges up to Nicole. ‘What do you want to know?’ she asks, pulling herself up straight. ‘We want to be able to do our laundry on Sunday,’ he says. ‘Otherwise, we don’t have clean clothes to wear for Monday and have to stay in our cells.’ He speaks in a subdued tone, as if bearing the weight of the entire department. ‘I’m not showing up to work in dirty clothes: I was raised better than that.’ ‘You should have said something to Henk; he was just here,’ she says. ‘The guys who stay in their cells all day can wash their clothes whenever they want,’ he continues, ‘whereas those of us who work don’t have that option. It makes no sense!’ He turns away and walks back to his seat. ‘We call him the Capo because he was involved in organized crime and acts as a spokesman for the group,’ Nicole explains. ‘Unfortunately, being right and having things put right are two different things in here.’

13

At the lunch break I find myself sitting shoulder-toshoulder with the Capo, but can’t seem to utter a word. Two women are waiting for their dish to heat up in the microwave. Diagonally across from me a husky guy in a Kappa T-shirt swallows a bite of lasagna and lets out a loud burp. He looks around triumphantly. The women give him an exasperated look. ‘Is that how you act at home too?’ the Capo enquires, but he doesn’t sound too serious. ‘Sorry,’ the guy says apologetically and supresses another belch. The room fills with the smells of melted cheese, tuna, and coffee and the hum of the inmates.

The Capo cuts his tuna sandwich into four equal pieces and removes the fish bones with a plastic fork. I’ve washed the purple chalk off my hands as best I could but the pigment is stuck under my fingernails and I can’t stop picking at it. ‘Are you paid by the line?’ he asks, turning toward me, and it’s hard to tell if he’s joking or serious. I think of the financial incentive recently implemented to boost the prisoners’ work ethic and morale. ‘Neither one of us is getting rich in here,’ I reply. ‘If I were paid by the line, you’d be sitting next to a wealthy man.’ He doesn’t smile. ‘That purple drawing looks like a setting sun. Why don’t you draw some birds in there?’ he asks. ‘That would cheer us all up.’

I think of Henk, who spoke so ambitiously about the new humane regime. ‘The gentler tactics have an effect; they’ve been shown to work,’ he’d said. And he might well see a sign of that in the Capo’s desire for me to draw some birds and to be allowed to do his laundry on Sunday.

14

To get started, I draw a circle. Yet despite my deep concentration, the nine angles in it betray my discomfort. The piercing glances of the inmates don’t make things any easier.

15

‘If it’s supposed to be a hole, it doesn’t do us any good,’ the Capo comments. He points to the opposite wall, behind which lie the grasslands of Diegem. ‘That’s where freedom beckons and that’s where the hole should be.’

16

At two-thirty the group gathers near the exit of the Atelier. I join them, leaving behind the unfinished drawing. Pressed together and listless as children after a swimming lesson, the sixty of us trudge through the maze of corridors, guards in front of and behind us. The sluggish pace prompts the Stamper to speak. ‘I grew up in Diegem, when it was still a marshy plain with trees and bushes we’d hide in and get into mischief.’ I can’t believe my ears. What if he knows the residents of Witloofstraat? ‘May I ask what you’re in here for? Did you steal some chicory or something?’ I ask. ‘In 2010 I received a suspended sentence of four years in connection with a slew of traffic violations. I’m now serving that sentence. The violations were from thirteen years ago, copain.’ He’s silent for a minute. I take advantage of the opening and ask: ‘Do you know any people living on Witloofstraat?’ ‘In fact, that’s us, isn’t it? We’re their neighbours.’ His mouth twists into faint smile. ‘I don’t hate the guards or the judge who convicted me, but I do hate the police agent who arrested me two years ago. He knew there was a hemp farm in the attic; I didn’t. When I told him that my suspended sentence was almost finished, he should have let me go. There are some men who would be mentally destroyed after being set up like that.’

‘We never know how long our confinement will last,’ the Capo grumbles from behind us. ‘If there is a shortage of cells or guards, they might suddenly release you early, or maybe because of good behaviour, or even if they just feel like it. In the Netherlands, Germany or Sweden you know exactly how long you’ll be locked up for. In theory, nothing gets taken off of that, so you have something to work towards. But this is a shithole country.’ ‘It’s like waiting for a bus that never comes,’ the Stamper adds. ‘They don’t teach you here how to get out of your own way.’ His voice sounds hoarse. ‘When I was first locked up, my son was a child; now he has a moustache.’

17

Once we get outside, the men are separated from the women. The sky is a royal blue. Because they are dawdling, the Capo and the skinny woman with the shiny face are ordered to move along. Then three officers accompany him, the Stamper, the man in the Kappa shirt and me to the Mountain House like it’s a military drill. ‘Look, there are the birds,’ I say.

Mountain House consists of three storeys with ten cells on each floor. The ‘rooms’, as they’re officially called, are reached by way of a galvanized steel staircase. The guards monitor things from behind a glass wall on the second floor. Men of every shape and size are leaning against the railings talking to each other, walking around or loitering near the entrance to their cells. ‘Coffee?’ the Capo calls out over the hubbub, then starts up the stairs without waiting for an answer. The guard, a greenhorn still shy of twenty, apparently has no idea who I am. On the way to my coffee date, I give a friendly nod to the men I pass, but they barely get out of the way.

‘Have a seat,’ he says, gesturing to the only chair in the space. ‘A lot of those young guys are in here on an almost permanent basis. They get locked up, return briefly out into society and then are sent back in. Apparently, they like it better on the inside than on the outside. To them, this is the State Hotel.’ Sitting on a built-in table are a television set and a chrome espresso machine that is now heating up. You can see the outer ring of Brussels in the distance through the large window. ‘All of the cells are basically the same, but this one has the most expansive view. It takes some doing, a cell exchange, and it takes a couple of years to get up in the standings, but then you really have something,’ he says proudly. It’s cramped and sparse in there, like a caravan but then without amenities. I resolve not to use the word ‘room’, even though the view is a considerable plus.

‘I don’t know what they’re paying you, but you could earn twice that working for me,’ he says. I wisely hold my tongue and neglect to mention that I get paid in stories

18

and prefer to cash in on them in person, like right now. ‘How much more time do you have?’ I ask. ‘They could discharge me any day now, but maybe they still need me. I don’t have an immediate replacement. Next week I get two days’ leave and I’m going to have a waffle iron and put my affairs in order.’ ‘A what?’ ‘Two women at the same time. I won’t be wearing anything but an ankle monitor, and they find that powerful.’ A sleazy smile appears on his face. ‘I’ve noticed how seriously you take your work. How long have you been doing it?’ he asks. I look at the garish chalk under my fingernails. ‘Twentythree years,’ I say. He whistles through his teeth. ‘It took them longer than that to catch me.’ Suddenly the door swings open. A burly guard with a bleached goatee and red blotches on his neck steps inside. ‘You are never allowed to enter the rooms and absolutely not allowed to accept coffee or anything to eat from the prisoners,’ he roars at me. ‘I invited him,’ says the Capo. ‘It’s a matter of principle. I’m not saying you’re an idiot, but there are plenty of them around,’ the bearded man snarls at him.

The stairwell has now emptied out, and the two officers have locked all the cell doors except for the Capo’s, which I left open a crack. ‘Go ahead and close it. It locks automatically,’ I hear him say. ‘It’s not something I want to do,’ I say. ‘Don’t feel bad,’ he replies.

19

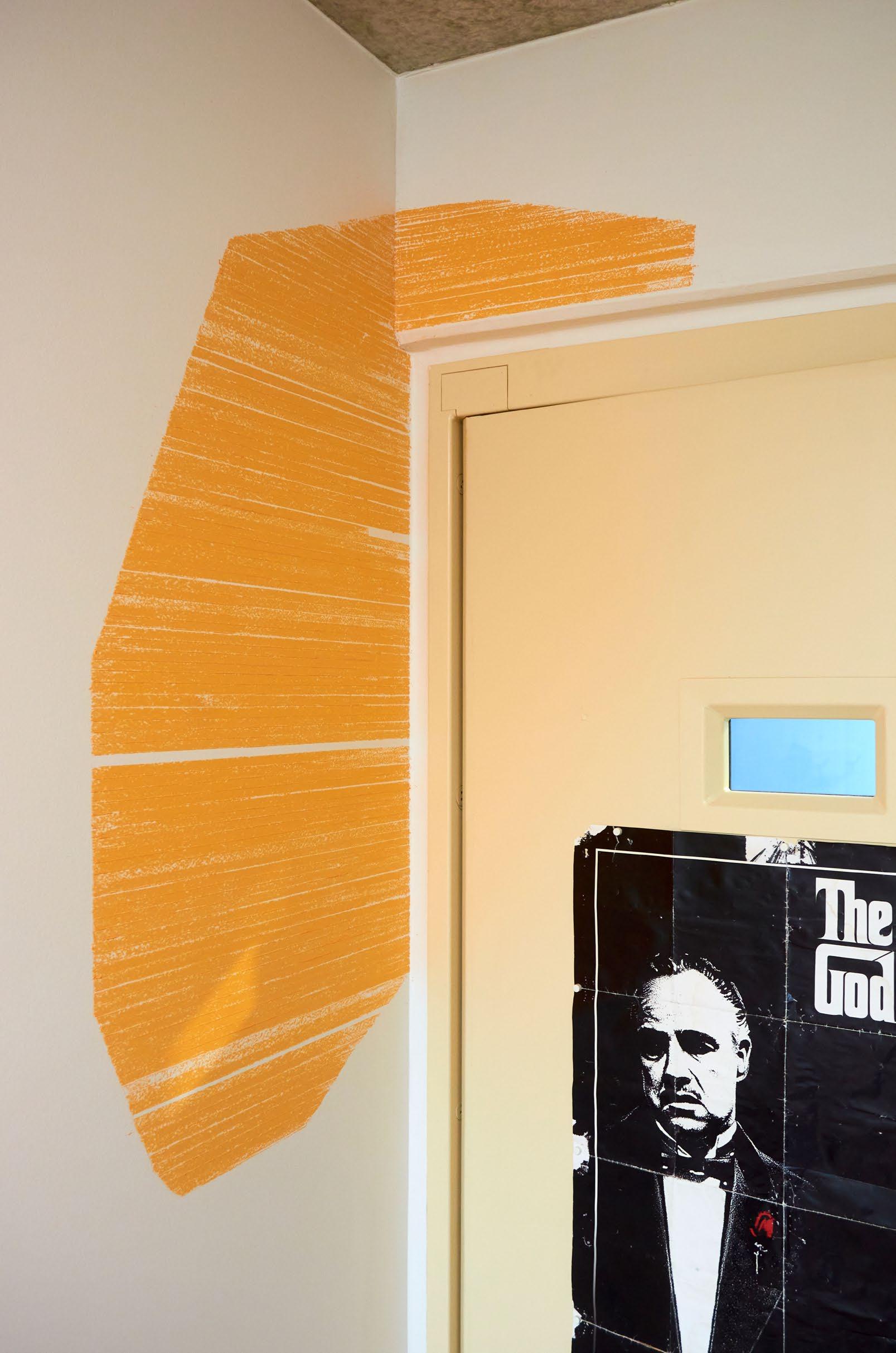

Once the Capo and the Stamper are back under lock and key, I start drawing around the entrance to Mountain House, a name jarringly at odds with the reality.

20

21

The inmates have been convicted of murder, assault and battery, drug trafficking, sexual offences, fraud and money laundering. They’re serving sentences ranging from four to eight years.

22

Aside from the buzzing sound of the black water filter, it’s eerily quiet. It’s unreal to think that behind the cell doors are people of flesh and blood.

23

24

The surface structure of the wall is ideal for drawing on firmly. The white chalk plane has a softness about it, like a tapestry.

When the inmates come out of their cells, they’re not sure what to make of the drawing. The man in the Kappa shirt unexpectedly steps forward and offers to protect it. I’m surprised that he, of all people, would take on such a responsibility, the biggest brute of the group, someone who, I imagine, isn’t the least concerned about security. He sees me hesitating and says, ‘I’ll make sure the guards keep their hands off of it.’ I give him a thumbs up to indicate that he’s hired. He looks around as triumphantly as after his belch in the kitchen and doesn’t leave my side after that.

25

‘We have nothing to be proud of. You can be proud of your work; we can’t,’ he says.

26

27

I also draw in Ocean House for two days, another one of those fantastical names. The drawing is abstract, but several of the inmates see a face in it, complete with a nose and a chin. One also recognizes the shape of Africa.

28

It doesn’t occur to anyone to touch the drawing, making the need for protection redundant.

30

On the wall opposite the purple drawing in the Atelier, I draw a second chalk shape. According to the Capo, it’s the opening to the Daltons’ escape tunnel. He has a lot of private chats with the woman with the shiny face, but she avoids me completely. She does enhance the work atmosphere by humming along with the songs on the radio, though. He tells me by way of warning that in a previous life she knocked off her boyfriend and her husband.

31

The man in the Kappa shirt searches the airwaves for reggae and Caribbean music. Like most of the people here, he’s serving a long sentence for drug trafficking. ‘It’s an open secret that we’re training the guards,’ he says.

32

His helpfulness does the drawing good.

33

‘Why are you drawing in white chalk now and not purple? We think it’s because you’re out of coloured chalk,’ he says.

34

‘If the drawing refers to the Daltons, you could make it more exciting,’ the Stamper says. ‘You should colour that blotch under the window red to show that the little brat Joe has bumped his head.’

35

The drawing undermines the rectangularity of the walls and windows.

36

37

38

Prison protocol calls for a high level of sophistication and restrained interactions.

I’m starting to feel at home here and take more and more liberties.

39

I do a small drawing all the way at the back of the Atelier. Rolling shelving units are often stored in front of this wall, so the drawing will be hidden from view, but that doesn’t make it any less important.

40

41

‘Life without coffee and cigarettes is pointless,’ the Capo asserts.

42

When I ask the Stamper what he has on his record, he says, ‘Let’s just call it money laundering and leave it at that.’

43

The tumult alternates regularly with a muffled silence.

44

I’ve developed a routine of drawing in the Atelier until two-thirty and then spending the rest of the day working in the residential units of Mountain House. Every once in a while, I strike up a conversation with the Capo, but ever since I was fished out of his cell, he keeps it brief. There is some serious flirting going on between him and the woman who took out two men. ‘She’s drawn to criminals, the more extreme the better,’ the Stamper tells me. ‘She barely notices me,’ I say. ‘You’re too soft, too good, not enough of a bad boy,’ he answers. And while I would never want to come across like a criminal, the notion of being considered a goody two-shoes offends me even more. Drawing with chalk has gotten me into more than my fair share of sticky situations over the years. It has moulded me into who I am and toughened me up but never dulled my edge. I gulp down a big swig of coffee in an attempt to wash away this internal discord, and to my horror, I let out a terrible belch. It’s so loud and metallic that every face in the room turns my way, except for the woman who always ignores me. ‘Sorry,’ I say. My imperial eructation was definitely louder than the one the man in the Kappa shirt had let out and it puts me on the map. Head held high, I stride back to my spot and continue drawing as a man among equals.

The Capo addresses me later in the day: ‘Is that how you act at home too?’ It’s pretty much all I do, I want to say, but don’t. It would make me seem ridiculous, and more importantly, it’s not true. Instead I say, ‘I can’t do almost anything at home.’ He nods knowingly.

45

Per the management’s orders, I’m not allowed to go into the prisoners’ cells, but I do anyway. The guards rotate and some are not as strict as others. One of the times the greenhorn is on duty, I ask the Capo if I can draw on his cell wall.

46

‘You’re not allowed to get the cell walls dirty, which means you can’t put any chalk stripes on them. Officially, you’re now in violation of the rules. And you’re easy to trace; too easy, if you ask me,’ he says.

He lies stretched out on his cot while I draw. ‘No one around here has any patience. They all think they’re the centre of the world. Some of these guys will come along and pound on the door, which bothers us, but they never get punished for it.’

47

48

‘It’s pretty impressive that it took them so long to catch you,’ I muse as I draw in the Capo’s cell. I work quickly, not entirely at ease, since I don’t know how long I have.

‘You’ll appreciate the story behind it. It all has to do with chalk, or actually limewash paint.’ He sits up to tell me about it. ‘I was known as the leader of the white paint gang. Every time I got wind that the police were closing in on me, I would have the walls, doors, floor and furniture in the office I rented whitewashed. Then I would leave behind an envelope with a thousand euros for the cleaning crew and cancel the lease. The lessor would, of course, have the paint removed as quickly as possible. Any trace of me was already gone, but the cleaners would come through and do it over again professionally. Since half of the money I left probably disappeared into the landlord’s pocket, no one ever reported a thing. It was a watertight system for thirty years.’

49

After the man in the Kappa shirt assures me he’s not part of the cell exchange, I also do a drawing in his cell.

50

The drawings in the two cells are discovered by the guards, whereupon I receive a reprimand from the higher-ups and almost get kicked out of the prison. As a result of the incident, though, I climb higher in the inmates’ pecking order.

51

My request to place scaffolding against the blue wall meets with resistance from guard Nicole. She makes a good impression with her small, wiry frame and firm approach.

‘The scaffolding and ladders are in such high demand that it’s better not to have them at all,’ she says.

52

53

‘I would round off the drawing more at the bottom, bring it a bit lower,’ says the Stamper, critiquing my work.

54

55

The letterboxes in the cell complexes can be used by the prisoners to submit queries to the monitoring committee, the complaints committee or the medical service.

56

I place an empty speech bubble above the letterboxes: a plane of projection for the inmates’ stories.

57

One night as I walk down Witloofstraat on my way home, I run into the landlord Jean-Pierre. He’s still fixing up his buildings and asks me in a grouchy tone when I am going to finally remove the chalk lines from the houses. ‘People think it’s mould,’ he complains. ‘Just be thankful it isn’t,’

I reply, ‘but I’ll wash the facades as soon as I’m finished in the prison.’ ‘How is it in there, actually?’ he enquires.

‘You would like it,’ I say. ‘Everything is double-glazed, there’s good insulation, good ventilation, no issues with dampness or vermin, no flooding, and it smells nice. I get coffee and my drawings are guarded.’

58

I start on an overly ambitious large drawing on the wall above the kitchen in the Atelier and move a metal table over a few yards so I can reach the higher sections more easily. Out of nowhere, the woman the Capo warned me about appears and starts attacking me. I was completely unaware that she is responsible for the table next to the sink, which holds a liquid soap dispenser and a roll of paper towels for everyone to use. She is beside herself. I jump down quickly and slide the table back to its original location, then hastily put the dispenser and paper towel roll back as if nothing happened, but the damage has been done. ‘Just stay out of her way for now. She is incapable of forgiveness,’ the Capo advises, after coming over to see what the commotion was.

59

After repeated requests, Nicole finally requisitions the only ladder the Atelier has at its disposal for me to use.

60

I leave my belongings on the ground while I draw, neatly stacked against the feet of the ladder. One day, when my guard is down, my notebook disappears. In that instant I lose everything I’ve written about prison life. But, not wanting to make the inmates look bad, I blame the disappearance on my own carelessness and don’t report the theft. I follow the unwritten rule that no one snitches on anyone else here.

61

62

63

To be continued…

You can subscripe here for the mailing list: www.romapublications.org/Bart_Lodewijks_Library

64

Colophon

Drawings and text: Bart Lodewijks

Photographs: Bart Lodewijks

Editing: Bep van Muilekom

Copy editing (Dutch text): Lucy Klaassen

English translation: Nina Woodson

Image editing: Huig Bartels

Graphic design: Roger Willems

Publisher: Roma Publications, Amsterdam

Production: Government of Flanders and Cafasso

This project was made possible in part by: Haren Prison, Brussels

Quasi Museum

Thanks to: Anouk Focquier, Ief Spincemaille, Henk Mortier

This publication is part of the Quasi Museum, a project by Ief Spincemaille in collaboration with Berserk Art Agency / Anouk Focquier.

© Bart Lodewijks, 2024