Special Issue: Behaviourally Informed Organizations

MANAGEME NT The Magazine of the Rotman School of Management UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO 2024 BEHAVIOURAL SCIENCE IN ORGANIZATIONS PAGES 92, 98 Data is Everywhere! PAGE 90 The Elements of Context PAGE 84 Changing Behaviour for Good PAGE 20

Interested in group subscriptions? Order 5 or more and save! Email rotmanmag@rotman.utoronto.ca for details. Get access to the latest thinking on leadership and innovation with a subscription to Rotman Management, the magazine of Canada’s leading business school. An affordable professional development tool that will help you and your team thrive in a complex environment. www.rotman.utoronto.ca/subscribe "Read cover to cover. Superb." Tom Peters Author, In Search of Excellence; Thinkers50 Hall of Fame Subscribe today! Just $49.95 cad Available in print or digital MANAGEMENT The Magazine of the Rotman School of Management UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO SPRING 2023 TAKE YOUR LEADERSHIP UP A NOTCH How to Stay Cool Under Pressure Hybrid Leadership: Lessons from a Crisis The Art of Precision Questioning Next-Level Leadership MANAGEMENT Questioning Next-Level Leadership

MANAGEMENT

SPECIAL ISSUE: Behaviourally Informed Organizations

Features

6

Harnessing Behavioural Insights: A Playbook for Organizations by Bing Feng, Melanie Kim, Jima Oyunsuren, Dilip Soman and Mykyta Tymko

14

Thought Leader Interview: Richard Thaler by Dilip Soman

20

Changing Behaviour for Good by Angela Duckworth and Katy Milkman

32

Consumer Behaviour Online: A Playbook Emerges by Dilip Soman, Melanie Kim and Jessica An

50

Managing Mental Health: A Behavioural Approach by Renante Rondina, Cindy Quan and Dilip Soman

Bridging the Organ Donation Gap with Behavioural Science by Nicole Robitaille and Nina Mažar

MART

60

Behavioural Science in the Wild

by Michael Sobolev

66

The Behavioural Science of Online Manipulation

by Elizabeth Costa and David Halpern

72

Cash Transfers to Address Homelessness

by Kenneth Ong, Daniel Daly-Grafstein and Jiaying Zhao

78

Leaning In or Not Leaning Out?

by Joyce He and Oceana Ding

104

Defaults Are Not the Same — By Default by Jon Jachimowicz, Shannon Duncan, Elke Weber and Eric J. Johnson

92

Banking on Behavioural Science: Commonwealth Bank of Australia by Jingqi Yu, Sanskriti Merchant, Bing Feng and Dilip Soman

98

PwC Consulting: Strategic Value by Sanskriti Merchant, Ankita Suresh and Jingqi Yu

110

The Between Times of Applied Behavioural Science

by Dilip Soman, Jingqi Yu and Bing Feng

Idea Exchange

26

POINT OF VIEW:

POINT OF VIEW: The Elements

Context by Selina Yang, Meghan Yeung, Nathaniel Barr, Chang-Yuan Lee, Wardah Malik, Nina Mažar, Dilip Soman and David Thomson 88

EARLY

90

EARLY

POINT

47

POINT

57

115

BI-ORG BOOKS:

Rotman Management

Behaviourally Informed

Published in January, May and September by the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, Rotman Management explores themes of interest to leaders, innovators and entrepreneurs, featuring thought-provoking insights and problem-solving tools from leading global researchers and management practitioners. The magazine reflects Rotman’s role as a catalyst for transformative thinking that creates value for business and society.

ISSN 2293-7684 (Print)

ISSN 2293-7722 (Digital)

Co-Editors

Oceana Ding and Dilip Soman

Contributors

Elizabeth Costa, Angela Duckworth, Bing Feng, David Halpern, Joyce He, Matthew Hilchey, Eric Johnson, Melanie Kim, Nina Mažar, Katy Milkman, Piyush Tantia and many other members of the Behaviourally Informed Organizations partnership.

Contact Us/Subscribe:

Online: rotmanmagazine.ca

(Click on ‘Subscribe’)

Email: RotmanMag@rotman.utoronto.ca

Phone: 416-946-5653

Mail: Rotman Management Magazine, 105 St. George Street, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3E6, Canada

Subscriber Services:

View your account online, renew your subscription, or change your address: rotman.utoronto.ca/SubscriberServices.

Privacy Policy:

Visit rotman.utoronto.ca/MagazinePrivacy

Design:

Bakersfield Visual Communications Inc.

118

POINT OF VIEW:

Copyright 2024. All rights reserved.

Rotman Management is printed by Mi5 Print & Digital Solutions

POINT

121

Rotman Management has been a member of Magazines Canada since 2010.

Behavioural Science on the Ground: A Global South Perspective

Behavioural Science at Scale

MacLeod

Cameron French

OF VIEW: Segmentation Reimagined by

and Dilip Soman

by Anisha Singh and Chaning Jang 29 POINT OF VIEW:

by Piyush Tantia, Alissa Fishbane, Kate

and

44 POINT

Kayln Kwan

OF

Does Budgeting Actually Work? by Chuck Howard and Marcel Lukas

VIEW:

OF VIEW: Taking Charge of Financial Information by Matthew Hilchey

81

OF VIEW: Designing Incentives to Improve Outcomes by Catherine Yeung and Yih Hwai Lee

84

of

CAREER RESEARCH:

Choice Architecture Interventions Considered Ethical?

Are

by Daniella Turetski

CAREER RESEARCH: Data is Everywhere! by

Stacey Choy

The Behaviourally Informed Organizations Book Series

by Jennifer DiDomenico

Reframing Change to Maintain Trust in Public Health

Ethan Meyers

by Jeremy Gretton, Derek Koehler and

A Brief History of BEAR by

BEAR HISTORY:

Dilip Soman

Organizations

57 29 88 81

47

The BI-Org Nerve Centre

Liz Kang, Cindy Luo and Yanyi Guo

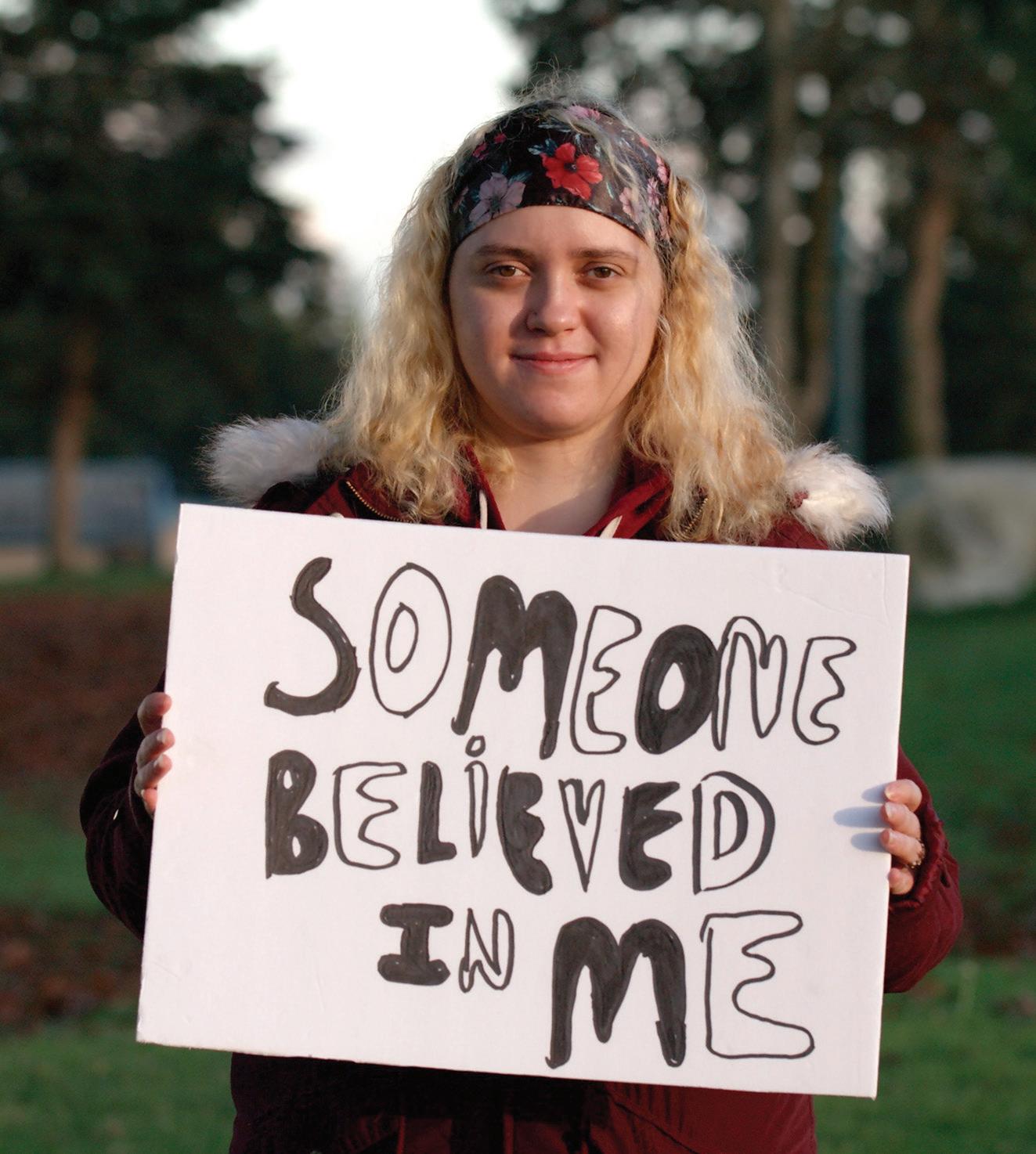

WHAT WAS IT LIKE TO WORK ‘behind the scenes’ at the Behaviourally Informed Organizations (BI-Org) office at the BEAR research centre? What most people don’t usually get to see are the human mechanisms and processes that play an instrumental role in supporting the activities and outputs from the partnership. The three of us would like to share our reflections on behalf of everyone who was part of the BI-Org core team.

Our mandate was simple: to make it (the partnership) work! We were responsible for numerous tasks, including facilitating collaborations, reporting requirements, budgeting and managing finances, running events, coordinating multiple book projects (plus this magazine issue), and providing research support. This happened through the first global pandemic in a century, as well as several changes to personnel as colleagues here and in our network moved on to new opportunities and new members came aboard.

Each of these activities and tasks came with their own trials and tribulations at times, but we were surrounded by team members who were truly supportive and reliable in every way. We would argue that the origin of this supportive organizational culture stemmed from the behaviours modelled by our leaders at the helm. Leaders who provided guidance and feedback — both positive and constructive — actively encouraged continuous learning and career growth, promoted a healthy work-life balance, often showed appreciation and attributed successes to

the team with humility (even when they really deserved the spotlight), and had everyone’s (idiomatic) backs.

This empowered us to confidently tackle our responsibilities and assist the BI-Org faculty, student researchers and partner organizations with their research projects and related activities. Knowing that support was readily available allowed us to ask for suggestions when we were creating videos, animations, presentations, or infographics without any hesitation. It also meant that our interest in taking educational courses or workshops would be accommodated. We were granted the flexibility to work in a hybrid environment, and our well-rounded team learned to adapt and approach challenges by turning them into opportunities.

Under the leadership of humans who really understand the nuances of human behaviour, we are thankful for the boundless support that enabled us to meaningfully contribute to the partnership. We learned immensely from these experiences and will undoubtedly apply these learnings to other endeavours. It is bittersweet to see this partnership come to an end, but we know we can never really leave, especially after forming such memorable experiences and bonds at BEAR.

4 / Rotman Management Behaviourally Informed Organizations 2024

Liz Kang (BCom 2016), Knowledge Translation Specialist. Cindy Luo (HBSc 2015), Research Officer. Yanyi Guo (Rotman MBA 2023), Research Associate, Behaviourally Informed Organizations.

FROM THE EDITORS Oceana Ding and Dilip Soman

Behaviourally Informed Organizations

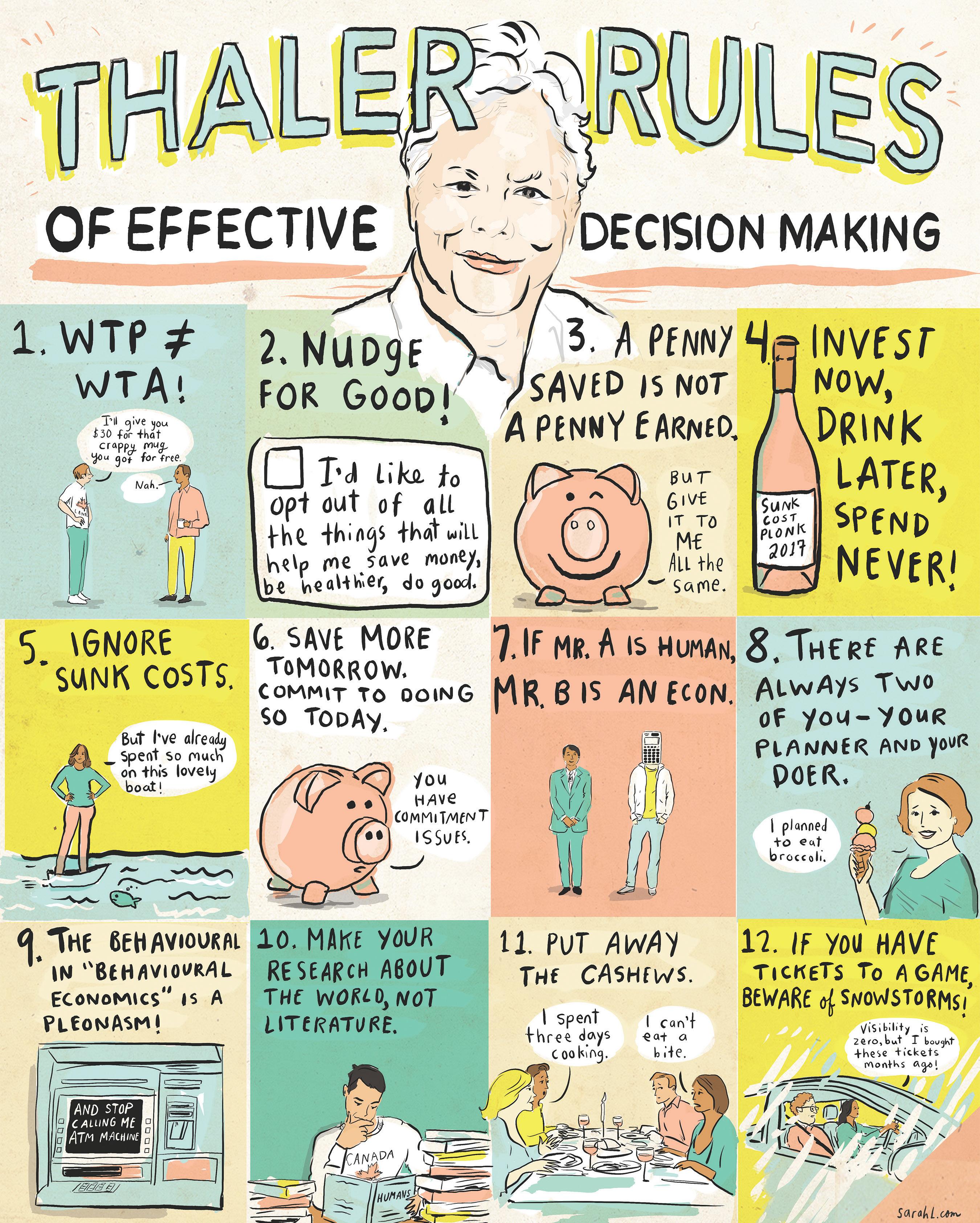

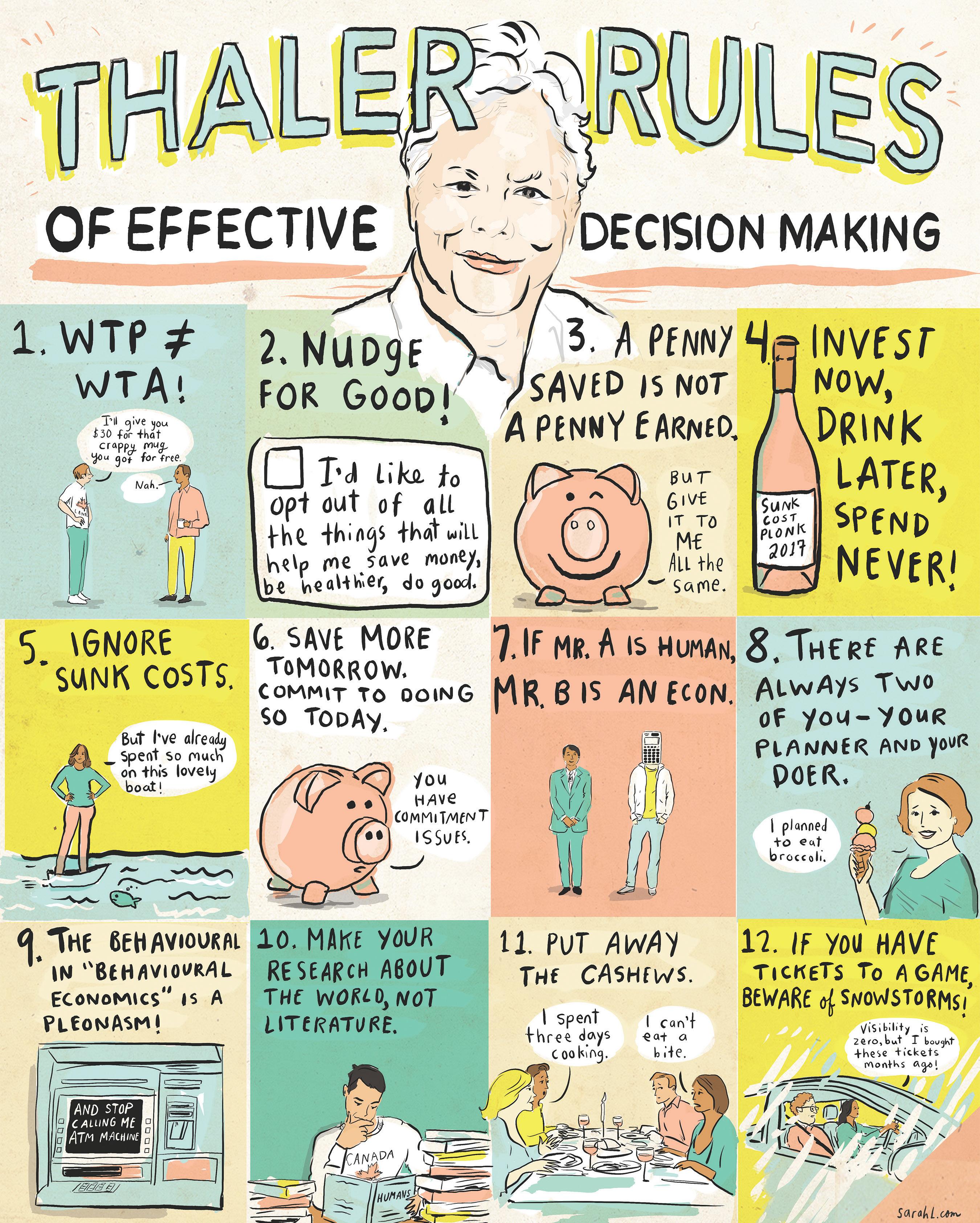

FOR THE PAST FIVE YEARS, the Behavioural Economics in Action at Rotman (BEAR) research centre has been home to an initiative known as the Behaviourally Informed Organizations (BIOrg) Partnership. BI-Org is a collective of academic researchers, government units, for-profit entities, consulting firms, and consumer groups across the world working on how best to embed behaviourally informed thinking and practices in organizations. The articles in this special issue of Rotman Management magazine are some of the outputs produced over the course of the partnership. This issue has also benefited from inputs of the BI-Org core team, as well as from Iris Deng (for conceptualizing the cover), Sophia Khan (for editorial assistance) and Sarah Lazarovic (for the Thaler Rules illustration).

Highlights from this issue include an interview with Nobel Memorial Prize winner Richard Thaler, a short history of BEAR, and an article by Dilip Soman, Bing Feng and Jingqi Yu on the challenges to the adoption of applied behavioural science in organizations. We showcase two case studies from our partnerships with PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and the Commonwealth Bank of Australia that illustrate what it takes to build in-house behavioural science capabilities. Nicole Robitaille and Nina Mažar, former BEAR members and now professors at Queen’s and Boston University, respectively, present an initiative that helps Ontarians who intend to sign up to be organ donors do so. Jiaying Zhao discusses what behavioural insights can teach us about creating successful cash transfer programs, and Joyce He shares findings from her research that show how certain choice architecture interventions can help close the gender promotion gap.

Beyond these highlights, you’ll find articles that discuss whether budgeting really works, whether choice architecture interventions are ethical, and how frequent changes in policy can be better framed to build public trust.

We recognize that most organizations are in the business of behaviour change, so understanding how behaviour change comes about is critical to organizational success. We hope that this issue teaches you something new about how to apply behavioural insights and inspires you to approach your work with a behaviourally informed lens.

Oceana Ding, Co-Editor

Oceana Ding, Co-Editor

Dilip Soman, Co-Editor

Dilip Soman, Co-Editor

rotmanmagazine.ca / 5

@UofT_BEAR

bear@rotman.utoronto.ca

HARNESSING BEHAVIOURAL INSIGHTS: A Playbook for Organizations

Some of the smartest organizations are moving behavioural insights up the value chain and embedding them into their everyday processes.

by Bing Feng, Jima Oyunsuren, Mykyta Tymko, Melanie Kim and Dilip Soman

WHILE THEY GO ABOUT THINGS in very different ways, at their core, every organization is actually in the same business: behaviour change. Whether it is a for-profit firm encouraging consumers to switch to its product; a government agency trying to get citizens to pay taxes on time; or a health agency interested in improving the consumption of medication, behaviour-change challenges abound.

Many organizations struggle to make behaviour change happen due to a fundamental empathy gap. ‘Econs’ — as depicted in economics textbooks — are hypothetical individuals who have well-defined preferences, are able to accurately predict the future consequences of their actions, have immense computational abilities and are unfazed by emotion. Humans, on the other hand, are cognitively lazy, impulsive, emotional and computationally constrained. The empathy gap occurs when organizations design products and services for econs, when in fact, the end-user is a typical human being.

Not surprisingly, the day-to-day behaviour of humans differs

significantly from that of econs. Factors including context, cognitive laziness, procrastination and social pressure play key roles in human decision-making. The emerging field of behavioural insights works to connect the psychology of human behaviour with economic decision-making to explain these phenomena.

Over the past 10 years, we have seen a great deal of progress in the application of behavioural insights (BI). With thousands of trials being run by hundreds of public and private-sector organizations around the world, human behaviour has become a key focus of activity in the policy, welfare and business world.

Inspired by the growing interest in BI from all sectors — as well the absence of any formal guidelines for embedding them within an organization — Behavioural Economics in Action at Rotman (BEAR) has published a ‘playbook’ to help interested leaders navigate the realm of BI. In this article we will summarize its key messages, beginning with a description of the four roles that BI can play to create value for virtually every organization.

rotmanmagazine.ca / 7

We can proactively design a ‘choice context’ to nudge users in a particular direction.

ROLE 1: BI as Problem Solver Behavioural insights can enable an organization to address problems arising at ‘the last mile’ — those moments where an end-user directly interacts with your organization or its product or service. Whether your last-mile issue is a low take-up rate, poor sales or low conversion rates, BI can be harnessed to make subtle changes to better align your product or service with human behaviour.

One of the key tools that enables problem-solving here is the concept of ‘choice architecture’, whereby organizations proactively design the ‘choice context’ in such a way as to steer or nudge users in a particular direction. Following are the four main types of decisions that choice architecture can influence:

COMPLIANCE. Getting people to act in accordance with a regulation set by a government or agency (e.g., tax deadlines, regulatory paperwork requirements).

SWITCHING. Getting people to convert from one choice to another (e.g., brand switching, replacing soda with water at meals).

FOLLOWING THROUGH. Getting people to follow through on commitments that they themselves have made (e.g., completing a weight loss regimen, or just acting on intentions).

ACTIVE CHOOSING. Getting people to break undesired habits by converting passive, mindless decisions into active choices.

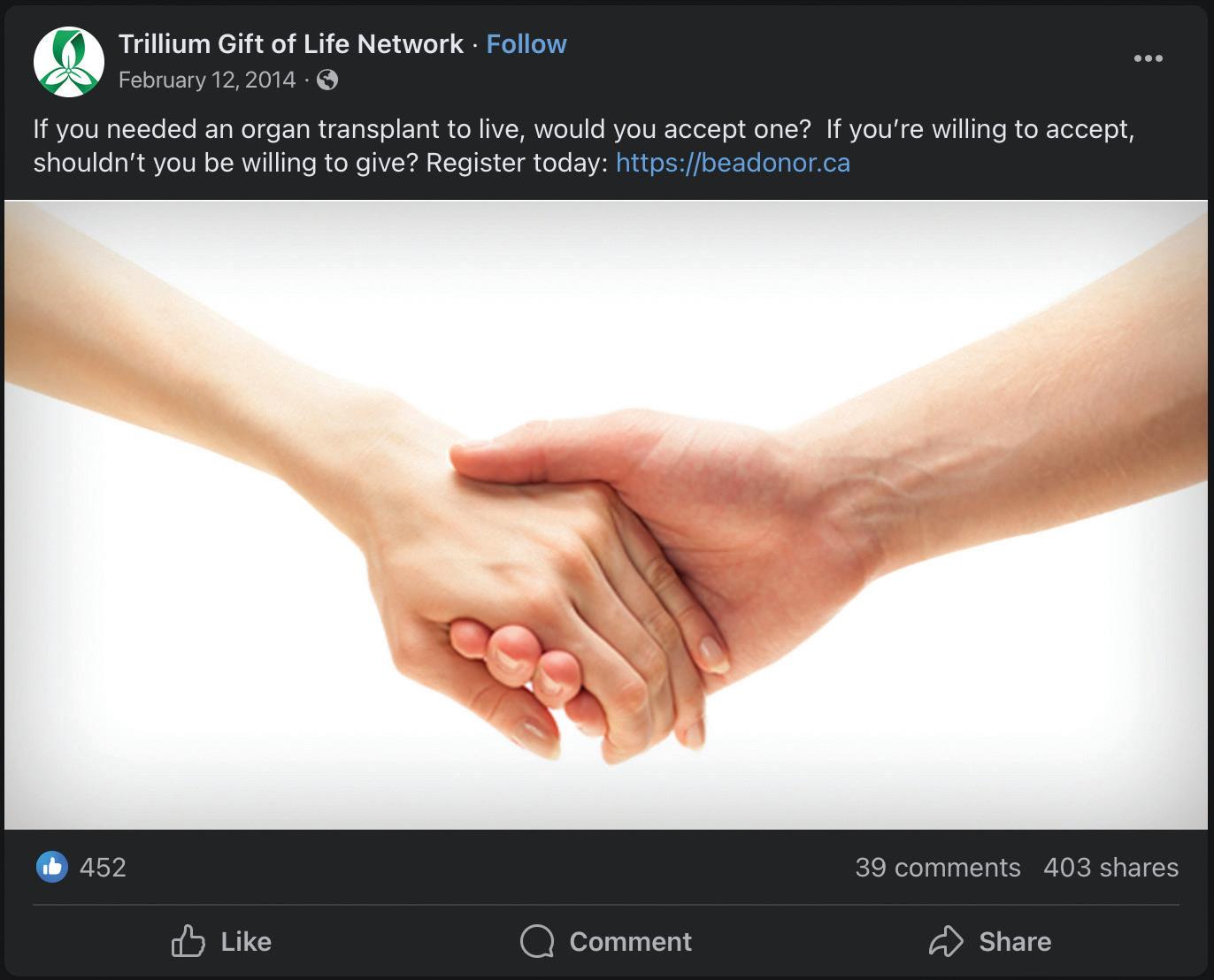

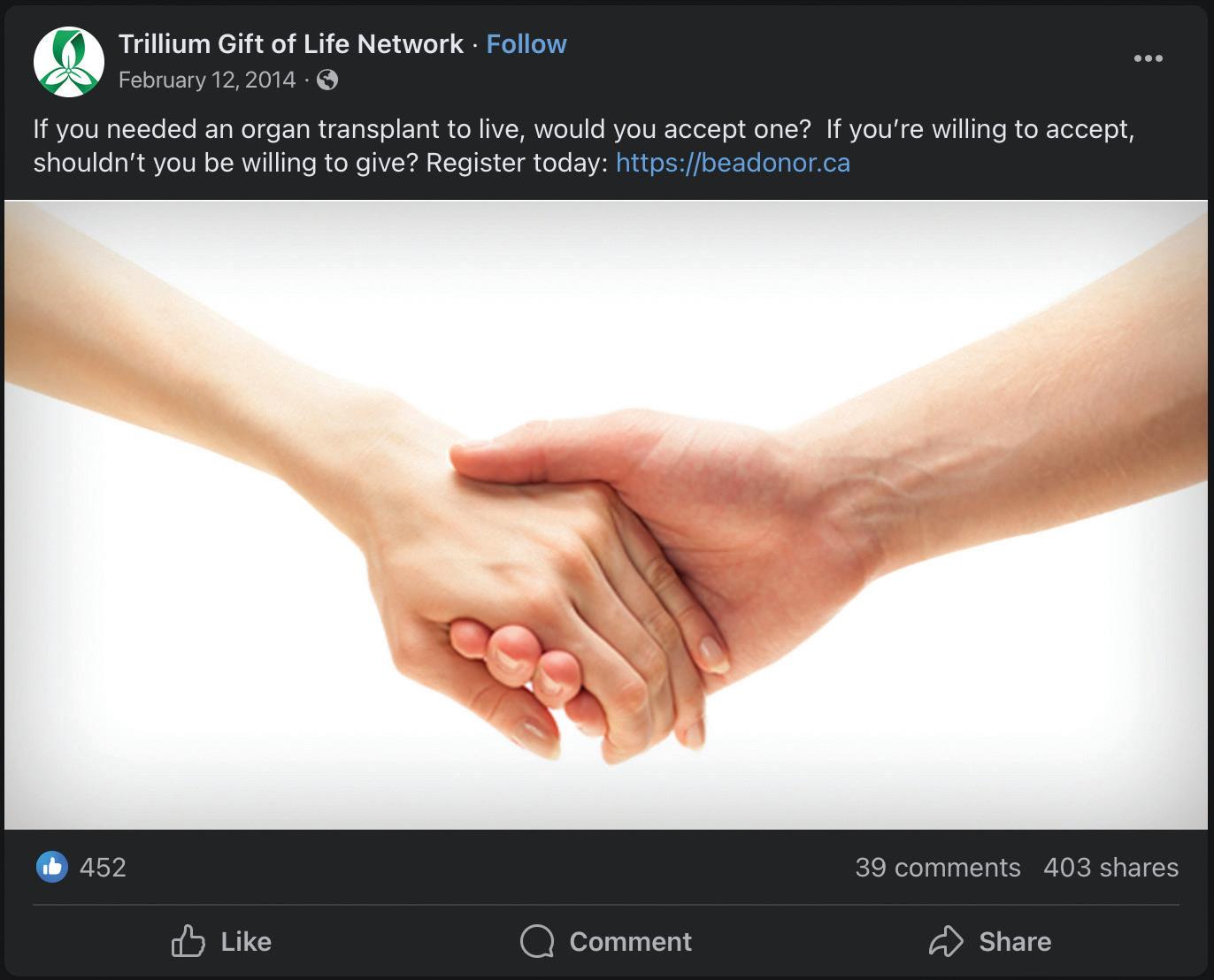

It is fair to say that the biggest successes for BI to date have come in the domain of choice architecture. For example, a few years ago, Ontario’s Behavioural Insights Unit set out to increase organ donations in the province. Working closely with project partners ServiceOntario and Trillium Gift of Life Network, the team’s goal was to increase the number of people who register as organ donors.

Initially, several ‘barriers to registration’ were identified, including the length and complexity of the registration form, failure to ask every customer if they wanted to register and asking customers to complete yet another transaction after they had waited in line and completed other paperwork.

The result: By removing these barriers — and thereby enhancing the choice architecture — registration rates increased

by 143 per cent. The organ donor registration process in Ontario was redesigned based on the following choice architecture principles:

• Provide different versions of the donor registration form;

• Change the timing of when the form is handed out; and

• Offer additional information to help people make their decision.

ROLE 2: BI as Auditor

At the end of every design process for products, services or processes, a behavioural scientist can be tasked with auditing the outcome and evaluating it for human-centricity. In this role, BI is used to evaluate and provide suggestions for further ‘humanizing’ organizational outputs.

The federal government’s Impact and Innovation Unit (IIU), along with BEAR, worked with the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) on its goal to increase the percentage of women in its ranks from 15 to 25 per cent by the year 2026. The team used a BI lens to audit the following stages of the recruitment process:

THE APPLICATION PROCESS. BI-informed changes were made to the Armed Forces’ application form to increase clarity and understanding. Furthermore, the Department of National Defense (DND) made improvements to the appointment process and recruitment follow-ups.

RECRUITMENT MARKETING. The IIU conducted a social media marketing trial aimed at understanding ‘what works’ in engaging Canadian women with a career in the Armed Forces.

POLICY AREAS AND GUIDELINES WITHIN THE CAF. A number of policy areas, including deployments and relocation, leave without pay, childcare support, and long-term commitments were identified for consideration and BI-inspired improvements.

The result: The collaboration was successful and has resulted in changes to the CAF’s marketing and recruitment efforts and an increased appetite for experimentation in these areas. Key success factors included buy-in from executives at both the CAF and the DND. This was essential in allowing the IIU access to the relevant information and in implementing recommendations. In addition, the IIU was equipped with well-

8 / Rotman Management, Behaviourally Informed Organizations 2024

rounded staff that included both quantitative and qualitative researchers. The relationship between the IIU, CAF and DND has resulted in continued engagement and testing. The DND has also recently established its own BI team: Personnel Research in Action (PRiA).

ROLE 3: BI as Designer

In this role, a behavioural scientist is involved from the outset, ensuring that the design of a product, service or process is behaviourally informed from the start — which means that the process always begins with observing actual users in a natural setting.

One of the key concepts in this domain is ‘behaviourallyinformed design’, an approach that combines the principles of BI with those of ‘design thinking’. The BEAR team has worked with a couple of government branches to employ BI to improve consumer protection. At these agencies, BI is now used to better understand the behaviour of consumers and agents in different marketplaces. The agency continues looking for opportunities to apply BI to both its policy design and its daily operations.

Three Truths About Behavioural Insights

1. PEOPLE ARE ONLY RATIONAL TO A CERTAIN EXTENT. We often assume—sometimes implicitly—that people balance the pros and cons and assess risks on the basis of all the available information, and thereby make well-considered and consistent choices. The behavioural sciences teach us that the choices people make are only rational to a limited extent. One example of this is that people are more sensitive to a loss than to a gain . As a result, they put in more effort and take greater risks to avoid loss than to win the same amount.

People also follow certain rules of thumb or shortcuts in processing information. One example of this is the availability heuristic : for events that we can recall more easily—for example, because they were distinctive or emotional or recently in the news—we overestimate the likelihood that they will occur again. These deviations from rationality are partly predictable, which means we can take account of them in policy-making.

2. PEOPLE HAVE LIMITED SELF-CONTROL. It takes effort to resist temptation and suppress impulses, and people have limited available resources for this. They want to eat more healthily, exercise more often or save for their retirement, but in practice it turns out to be harder than they thought. One consequence of this is that there is a major difference between planning to do something and actually doing it — between intention and action. Everyone has experienced this conflict at some point: planning to do some chores but ending up slumped on the sofa; starting a diet but ending up in a burger bar after just a week; wanting to save but still going out for dinner.

Another example of this role is the growing realm of selfcontrol products. Products and services are being created to enable customers to close the ‘intention-action gap’ — whereby people intend to do something positive but fail to act on it. Examples include Clocky, an alarm clock that literally runs away when the sleepy user hits the snooze button — propelling itself off of the bedside table and across the floor, out of reach of the dozing user; and stickK, a website that uses incentives and peer-effects to encourage people to stick to their goals.

The BEAR team also consulted with a government agency that set out to raise awareness of consumer protection issues, targeting adult consumers of all ages who were highly educated, but with limited knowledge of behavioural science. Working together, we designed its information brochure using the following BI guidelines:

• Ensuring that the colour and visual appearance were appealing to the public.

• Balancing image and text ratios to optimize comprehension and readability.

A psychological phenomenon relating to this is that people perceive a reward in the near future as more valuable than a reward further in the future. This plays a role in trade-offs between present and future rewards, such as pensions and savings, but also with respect to health.

3. PEOPLE ARE INFLUENCED BY THEIR ENVIRONMENT.

In order to determine what the ‘right’ behaviour is, people often look at the behaviour of others, particularly in new or uncertain situations. In a classic example of this, researchers conducted a study in which a group of confederates unanimously gave the wrong answer to a very simple question. The participant—who was unaware of this— then conformed by also giving the wrong answer. The news and government communication often show undesirable behaviour in order to stress its objectionable nature; however, often this actually gives the subconscious signal that this is ‘normal’ behaviour.

It is not just the social environment but also the physical environment that can have a major influence on behaviour. If fruit is within closer reach than chocolate, it makes it easier for canteen visitors to make a healthy choice. And optically narrowing stripes on the road prompt people to drive more slowly of their own accord. The physical environment can also communicate a particular social norm. An environment with a lot of litter on the street provides a lot of information about other people’s behaviour, and can therefore lead to more litter.

– Courtesy of the Behavioural Insights Network Netherlands

rotmanmagazine.ca / 9

• Managing the aesthetics of the cover to maximize the likelihood of the brochure being read.

The website for this agency was also improved by using appropriate language to maximize engagement. For instance, making sure that the negative connotations of words such as ‘hazards’, ‘risk’ or ‘unhealthy’ do not reduce attention by creating negative emotions; and testing the balance between visual and text information to minimize the risk of information overload. The results were impressive and included increased traffic to the website; an

increase in public debate and discussions on the site; and greater public reporting of marketplace frictions.

The following research findings indicate the breadth of opportunities in this domain:

• Telling people about positive, pro-social things that others have done (as opposed to asking them to stop doing a certain negative thing) can produce a fourfold increase in the number of people being more pro-social;

• Showing people smiling or frowning faces — a small emotional trigger — on their electricity bills improves resource

The ABCD Framework for Using Behavioural Insights

A: ATTENTION – Make it relevant, seize attention and plan for inattention

Attention is the window of the mind. However, attention is scarce, easily distracted, quickly overwhelmed, and subject to switching costs. Practitioners will often find that attentional issues have been overlooked in the design and implementation of traditional public policies. For this reason, when practitioners find a behavioural problem with attentional issues, it may prove more effective to design policy interventions that are more relevant, seize attention and, if this is not possible, think about how to plan for inattention.

B: BELIEF FORMATION – Guide search, make inferences intuitive, and support judgment

While there is no such thing as too much information in a traditional public policy perspective, information overload has become a serious problem for the people inhabiting the real world. For that reason, problems in belief-formation usually go hand in hand with the vast amounts of information and possibilities that are put on offer. In this perspective, it is not surprising to find that some of the biggest companies today are companies built around information search engines and consumer comparison platforms. What is perhaps more surprising is that traditional public policy interventions with regards to problems of beliefformation have been slow in copying what these companies do, but instead often try to approach problems in belief-formation by offering even more information.

C: CHOICE – Make it attractive, frame prospects and make it social

When making a choice is difficult, people are likely to be influenced by biases and heuristics in their decision-making. ABCD

suggests that researchers look into making preferable choices more attractive, use framing of prospects and leverage social identities and norms. The framing and arrangement of prospects is perhaps the most famous, but also the most technical area of BI as applied to public policy. In facing a series of choice-options, a person also faces a series of possible futures, i.e., prospects. While making it attractive provides reasons for choosing, the framing of prospects influences people to choose one or another option in subtle ways independent of what is chosen and why. That is, one option may be chosen over another simply due to the way that choices are presented – either as a matter of arrangement or as a matter of formulation.

D: DETERMINATION – Work with friction, plans and feedback and create commitments

Most people know that it is easy to form an intention of doing something. It is much harder to get it done. However, we do not always anticipate this and tend to systematically overestimate our own ability in taking the small steps to accomplish our goals. Thus, choosing to do something is not the same as succeeding. The world is complex and when any one person has to juggle multiple goals at once, even relatively small obstacles may become a reason for postponing taking action. As a result people tend to procrastinate leading to inertia and staying with the status quo.

–Courtesy of the OECD Behavioural Insights Toolkit

10 / Rotman Management, Behaviourally Informed Organizations 2024

conservation by 25 per cent; and

• Exchanging similarity-identifying information before a negotiation can boost the successful outcome rate from 50 to 90 per cent, with an average 18 per cent increase in perceived final value across parties.

ROLE 4: BI as Chief Strategist

In these cases, every touchpoint with an internal or external stakeholder is run from a behavioural perspective. The organization is human-centric in everything that it does, with behavioural insight as its main operating principle.

In these cases, firms can create BI-informed decision tools that help agents make better choices by providing feedback, rules of thumb, computational support, decision support or peer comparisons. For example, with a mandate to improve financial literacy and facilitate positive behaviour change, the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC) started offering financial tools and calculators to educate Canadian consumers and help them make better financial decisions: Its Mortgage Calculator helps determine a mortgage payment schedule based on user inputs and allows the user to input different pre-payment options to show them how they can save money; its Budget Calculator helps consumers get a portrait of where their money comes from and where it is going; and its Financial Goal Calculator helps people figure out how to pay off their debts or reach their savings goals.

Another example is Evree, whose app connects to your bank account and helps you save money for things that really matter to you. It basically employs many of the same behavioural science tactics that other companies use to make you part with your cash — but uses them to help you make smarter financial decisions instead.

All members of the Evree team, including management, content designers and engineers, are trained to understand the basic principles and applications of behavioural science. The objective is for the entire team to resolve problems using a scientific method and to approach daily operating roles with a BI lens. According to Stephanie Bank, a behavioural economist at Evree, “We look at behavioural science as our foundation, not just as a tool for a designer or a problem solver. All of our staff members are trained to look at business problems and opportunities through a behavioural lens.”

How to Get Started

Before deciding which of the four domains can create the most value for your organization, there are two key decisions to be made:

Embedding BIs in Organizations: Four Approaches

Concentrated Expertise

Diffused Expertise

CAPACITY BUILDING

INTERNAL CONSULTING BEHAVIOURALLY INFORMED ORGANIZATION

1. THE LOCUS OF EXPERTISE: whether to set up a concentrated team/unit within your organization OR to diffuse expertise across the enterprise; and

2. THE LOCUS OF APPLICATIONS: whether to use BI in a narrow application where they are applied to a specific geographic location or department OR to use BI in broad applications where it is applied across domains, geographies and departments.

These two decisions create four main approaches to embedding BI in an organization.

THE FOCUSED APPROACH. Employment and Social Development Canada has its own Innovation Lab comprised of behavioural scientists, data analysts, designers and policy analysts. The Lab works on projects with internal partners to tackle problems using a combination of human-centred design and BI methods. Its full-scale design project for 2017 was the Canada Learning Bond, which found ways to increase uptake and better understand perceptions of education and financial decision making among low income families.

rotmanmagazine.ca / 11

Broad Application Narrow Application

FOCUSED

FIGURE 1

Four Roles for Behavioural Insights

The valuecreation chain of product development

Roles that BI can play

Pre-marketplace: Within the Organization

Stage 1: Define goals, strategy and operating principles

Stage 2: Design and develop product, program or service

Stage 3: Prepare to go-to-market

In the Marketplace: The Last Mile

Stage 4: In-market: End-user interacts with product, program or service

THE CAPACITY-BUILDING APPROACH. The federal government’s Impact and Innovation Unit (IIU) houses expertise in four areas: innovative finance, partnerships and capacity building, impact measurement and behavioural insights. It offers services through a core unit at the Privy Council Office and through the fellowship model, in which scientists are deployed to other Government of Canada departments and agencies to provide behavioural science expertise and run behavioural insights trials.

THE INTERNAL CONSULTING APPROACH. The World Bank’s Mind, Behavior and Development Unit (eMBeD) is a behavioural science team housed within the Bank’s Poverty and Equity Global Practice. The team works closely with World Bank project teams, governments and other partners to diagnose, design and evaluate behaviourally informed interventions.

THE BEHAVIOURALLY INFORMED ORGANIZATION APPROACH. These examples and cases demonstrate that behavioural science is foundational to the entire organization and to all streams of its work.

In closing

The early years of BI as a field were marked by a need to score quick wins and find proof-of-concept for this approach to engineering behavioural change. Now that the field has gained broad acceptance, we expect organizations to start using it to tackle

more complex behavioural and policy challenges going forward. In our view, BI can — and should — play a key role in important societal domains such as the environment, business sustainability, preventive health, and diversity and inclusion. Consider this article as a nudge to get you started.

Bing Feng (MBA 2019), Jima Oyunsuren (MBA 2019), Mykyta Tymko (Rotman Commerce 2019), and Melanie Kim (MBA 2016) were researchers at BEAR.

Dilip Soman is the Rotman School’s Canada Research Chair in Behavioural Sciences and Economics. Soman is the Founding Director, and Feng and Kim previously served as Associate Directors.

Editor’s Note: The BEAR Playbook has contributed to the thinking on behaviourally based efforts at various organizations, including the OECD, in their work on the application of behavioural insights to public policy. The Western Cape Government in South Africa and the Impact and Innovation Unit in the Government of Canada aim to use its content to strategically embed BI into their work.

12 / Rotman Management, Behaviourally Informed Organizations 2024

BI as Designer BI as Auditor

BI as Problem Solver

BI as Chief Strategist

FIGURE 2

Develop a deeper understanding of behavior and decision-making with Behavioral Scientist magazine.

The latest insights from leading behavioral scientists delivered to your inbox each week.

Sign up for the weekly email edition today: behavioralscientist.org/ subscribe

The Nobel Memorial Prize winner, co-author of Nudge , University of Chicago professor reflects on the field after the publication of Nudge: The Final Edition.

Thought Leader Interview: Richard Thaler

Interview by Dilip Soman

Many years since the publication of Nudge, there is still some debate about how to define a nudge. How would you define it? The way we define it is that a nudge is some feature of the environment that alters the behaviour of Humans but not Econs, which means it does so without significantly changing incentives (since Econs care about prices or imposing limiting ‘choices’. According to that very narrow definition, incentives don’t matter but improved messaging could. But I don’t think we should get too hung-up on the definition of a nudge.

That title, by the way, was not our original idea. It was suggested by one of the many publishers who declined to publish the book. He thought Nudge might be a good title, which it was, but its widespread usage has become a mixed blessing. It did help sell books, but I think of the book as a book about choice architecture. I think that the real answer to your question is, everything is about choice architecture.

What I worry about is that people think that nudging is just about tweaks, adding a word, subtracting a word, changing the colour of the package or billboard. It should be much more that; it can be a complete restructuring of the choice environment.

One of the examples that caused much confusion from the original Nudge was the example about opt-in versus opt-out organ donation. The newer version of the book goes into more depth on the topic.

The most frustrating thing after the publication of Nudge was people were convinced that we were advocates for ‘presumed consent’, the policy that makes agreeing to be a donor the default. It’s true that when we decided to write this book, we had seen the data from Eric Johnson and Dan Goldstein’s Science paper from 2003. But when we started reading the larger literature, we ended up advocating something else that we called ‘prompted choice’, which is an opt-in with a nudge. In other words, people have to volunteer to be a donor, but they are asked periodically until they do agree.

After the original edition came out, every time a country switched from opt-in to opt-out, I would get notes like ‘Hey, way to go, Thaler. Another country has done what you have wanted’, and I would start tearing my hair out. We took a very deep dive on this topic in Nudge: The Final Edition and that chapter is completely rewritten. Here is my take on it. If you look at

14 / Rotman Management, Behaviourally Informed Organizations 2024

Sometimes the results of field interventions do not replicate because the context might be different.

that Science article, the fact that almost no one opts out should tell you something important. It probably should tell you that people are not paying very much attention to it. There are lots of situations where people override the default option. How much weight should we as a society place on the fact that 98 per cent of people did nothing? Should that be enough to infer the donor’s actual wishes?

Of course, the real question is, ‘Which system works better?’ That turns out to be a difficult empirical question. My conclusion is that an opt-in system, like we have in the U.S. and Canada, gets roughly 25 per cent more organs donated. Part of the problem is that in many studies, Spain is misclassified as being an opt-out country, which is not the case. That is important because Spain is an outlier. They are a world leader in providing organs for transplants, but they achieve that because they have a very carefully thought-out and effective organ harvesting choice architecture. As soon as a patient looks like they might be a potential donor, wheels start spinning. It is true that Spain once passed a law adopting presumed consent, but a year later reversed it. They are still classified in most analyses as being in the ‘presumed consent’ category. If you take them out, the results change. I think morally, and in terms of getting the most lives saved, my answer to the Do Defaults Save Lives question is — yes, but you should make the default that you have to opt-in [Editor’s note: See an article on using behavioural science to improve organ donation consent rates using active choice on page 50 of this issue].

What do you say to those who argue that the death of behavioural economics is imminent?

I wrote a paper 20 years ago that was called The Death of Behavioural Finance. I predicted that it would die because finance would become as behavioural as it needs to be. I think that is what is happening in economics. When I came to the University of Chicago, I was an outlier. Now we have a weekly behavioural economics workshop (different from the long-standing behavioural science seminar) that attracts 40-50 people each meeting. More important, there are lots of people who have behavioural economics as part of their toolkit, just like there are people who run experiments, or do econometrics or economic theory.

Should we be worried about the replication crisis?

There is no replication crisis in behavioural economics. Now, there is a big replication crisis in other parts of psychology. The basic principles of behavioural economics — that people have self-control problems, care about fairness, exhibit loss aversion, are overconfident, and so forth seem to hold true. I know this because every time I teach managerial decision making, I start by doing a survey of the students on all the classics. It is always the same. Always, 90 per cent of the students think that they will be above the median. Always, the most popular decile is the second one because of modesty.

Here is a good distinction between a concept and its operationalization to keep in mind. Loss aversion, for sure, exists. Now, does loss framing always have a significant effect? No. If we go and replicate the mugs experiment (demonstrating the endowment effect), it will work. But somebody who does an experiment trying to describe something either as a loss or a foregone gain — that’s somewhere between loss aversion and priming, and priming is not a robust phenomenon.

In Misbehaving, I wrote about ‘Supposedly Irrelevant Factors’ (SIFs). Sometimes the results of field interventions do not replicate because there might be an SIF in one case but not the other; the context might be different. That is not a true replication failure but is something we should be careful about when we do interventions in field settings [Editor’s note: See article entitled The Elements of Context on page 84 of this issue].

Would you say that the results of behavioural economics generalize across cultures and nations? Would you say that there are more similarities or more differences in people across the world?

There is a lot of research on cross-cultural differences. I do not want to minimize or disregard it, but if you ask the question the way you did — which I think is a good way to ask it — ‘do I view people as more similar or different?’, then I do have a clear opinion. I definitely believe that people are more similar than they are different. For example, there was a series of experiments on the ultimatum game [a famous experimental game played in pairs; one player gets to allocate a sum of money between themselves

16 / Rotman Management, Behaviourally Informed Organizations 2024

and a second player, and the second player can accept the allocation, or reject it such that no one gets anything] in various countries. The results do vary somewhat from one country to another, but the basic finding is robust: If you offer less than 20 per cent of the pie anywhere in the world, you have a very good chance of getting turned down.

Maybe you have to offer 30 per cent in this country and 10 per cent in another, but nobody likes to be treated unfairly. Now, there are customs and norms about what people think of as fair that will vary around the world, and that’s going to matter a lot. But again, we see more similarity than difference. There’s an old fairness study that Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch and I did that has been replicated all around the world.

Sometimes when organizations are trying to implement choice architecture to ‘nudge for good’, there might be some internal conflicts due to misaligned incentives. For instance, a financial institution that is trying to design tools to help clients avoid taking on too much debt might face pushback from other groups more interested in profit. Any advice on how to deal with that using choice architecture, or any other approach?

I think this is a big question — how can organizations do good and yet be financially successful? I actually spent some time with the board of a large Australian bank, Commonwealth Bank, which I believe is a partner of BEAR. They are trying to be what I call the ‘good bank’ [Editor’s note: See a case study on Commonwealth Bank of Australia on page 92 of this issue]. There is an open question as to whether a good bank can compete successfully against an evil bank. The reason why this is a question is that the good bank might look more expensive.

If the evil bank says, ‘Here’s a free credit card and a free checking account’, but there are a lot of sneaky fees, it being inexpensive will be a bit of an illusion. It is like some ‘discount’ airlines that may have a low-ticket price but if you have to check a suitcase, good luck. The only way to succeed as the good bank is via trust. You have to be selling trust and you have to earn it.

Here is an old story. My wife, France, and I were in Thailand and needed a cab ride to a restaurant for dinner. The tradition

there is that fees are negotiated. As a good behavioural scientist, I tried to use all the techniques I had learned and managed to get the fare down to something like $3 for a 20-minute ride. When we arrived at our destination, the driver said, “Would you like me to take you back?” I said, “Sure. What would the fare be?” continuing my tough negotiating posture. He said, “Same fare.” Now, we have a dilemma of, ‘Will he come back and get me?’ and ‘Will I be there if he does?’ He proposed a contract to solve the problem that no economist would ever suggest: He said, “Don’t pay me anything now. I will be here waiting for you.” Isn’t that good? He is telling me that he trusts me and I should trust him.

When we got done with dinner, of course, we went to look for him. Then we said, “On the way back, we want to stop at this night market.” He said, “Fine. I’ll wait for you. Again, don’t pay me anything now.” When we were done there, we walked 15, 20 minutes out of our way to go find him because we now owed him $9. I think there is a deep lesson there that if you want to be the good bank business (or any other type of ‘good’ business), the only way you can succeed is by being the place that people trust.

On the one hand, your research on mental accounting says that people are more likely to splurge impulsively on luxury purchases when they receive an unexpected windfall. On the other hand, you seem to advocate for policy that withholds more money from the taxpayer to ensure larger tax refunds at the end of the year, as I understand, because the refund feels like a windfall and will lead to increased savings. How do we reconcile this?

The bigger the windfall, the larger proportion will be saved, though some of it will get spent possibly on luxuries, possibly on durables. You can see this among academics, at least in the U.S., where there is this odd tradition that you get a nine-month contract and then additional ‘summer money’ on top of that. In most places, the ‘summer money’ takes the form of two months of salary. People live on their nine-month salary because they have to pay the rent every month and then they get this lump sum. You see both splurging and durable investments.

A study that I think would be very interesting to do is to compare people who get paid once a month with people who get paid

rotmanmagazine.ca / 17

Remember to nudge for good!

every two weeks. The reason is if you get paid every two weeks, there are two months out of the year that you get three paychecks. Those will feel like little windfalls. If you are affluent enough, it won’t matter, but if you’re constantly checking whether you have enough money to buy shoes for the kids, then I’m guessing that behaviour would be different in those two situations.

You have said, both in the book and elsewhere, that nudges are usually not enough for solving complex problems and that mandates and stronger shoves are sometimes necessary. This calls for a judicious mix of nudge and shove strategies which might not be easy for a practitioner to perfect. What advice can you offer, from a behavioural perspective, on how the practitioner can choose between nudging and stronger options?

When we wrote the book originally, the idea was to show that there are some things we can accomplish even if we tie one hand behind our back and don’t force anybody to do anything or even bribe them to do it. That was like changing defaults and little nudges. When it comes to climate change, we are not going to get there if we rely only on nudges. Like every economist in the world, I am in favour of a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade program because we’re not going to reduce emissions as long as they’re free.

Our chapter on climate change starts with that. First, get the prices right. Now, there are nudges that can help, and you get effect sizes like two or three per cent, which sounds small and cannot solve the problem alone but is nothing to sneeze at. We quote our former University of Chicago colleague and former president, Barack Obama, who liked to say around the White House, “Better is good.”

You have often said by way of advice to researchers; “Make your research about the world, not about the literature.” What do you mean by that?

What I mean by that is people should get ideas by looking at the world rather than by only reading journal articles. I think that there is a trap that graduate students and young faculty members start reading papers and they end up writing the 25th paper on

some topic because there’s some gap in the literature that no one has filled. I have rarely written more than two papers on any topic because I have a short attention span.

I’d rather write the first paper on mental accounting than the hundredth. People were doing mental accounting before I gave it a name, just like they were nudging before we gave it a name. Likewise, there have got to be a number of phenomena, of behaviours and marketplace observations that no one has written about and studied. Study those.

Any final thoughts?

Thanks to all my friends in Canada and around the world. As I always write when I’m asked to sign any of my books, remember to nudge for good!

Richard H. Thaler is the Charles R. Walgreen Distinguished Service Professor of Behavioral Science and Economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He is the 2017 recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, the co-author of Nudge (Penguin Random House 2008, 2021) and the author of Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics (WW Norton, 2016). He is widely considered as the founder of behavioural economics and applied behavioural science.

18 / Rotman Management, Behaviourally Informed Organizations 2024

A multi-day program for talent leaders

Inclusion by Design

Learn how to use behavioural insights and business design to advance your diversity, equity, and inclusion goals.

uoft.me/InclusionByDesign

CHANGING BEHAVIOUR FOR GOOD

Creating new habits might just be the most promising avenue for making behaviour change stick.

by Angela Duckworth and Katherine Milkman

WHILE WE SELDOM THINK ABOUT IT, our life outcomes are powerfully determined by seemingly trivial, repeated acts. Our health, for example, depends on thousands of daily choices — to eat well and exercise regularly, to avoid smoking, and to take medications as prescribed. And yet, 40 per cent of premature deaths each year result from suboptimal behaviour in this domain: Tobacco is responsible for 435,000 of those deaths, while poor diet and physical inactivity account for 400,000. Cardiovascular disease — the leading cause of mortality — is largely treatable with anti-hypertensive medicines; but just one year after receiving a prescription, only about half of patients are still taking their medication as directed.

Our bad habits run the gamit from health to personal finances. One in three American families has no savings at all, and 52 per cent are under-saving, even though most would need to save just 15 per cent of their earnings to prepare for the future. Academic success requires an array of good habits

at any age: attending classes, studying and engaging with challenge on countless occasions. Yet tellingly, 23 per cent of high schoolers and 49 per cent of college students drop out before earning diplomas. Sadly, all of these challenges to life outcomes disproportionately harm disadvantaged members of society.

In recent years, behavioural scientists have learned a great deal about the underlying situational and psychological factors that determine our daily decisions, leading to many successful and scalable interventions to change short-term behaviour. The problem is this: behaviour change rarely endures. In this article, we will review a small but growing body of research suggesting the most promising approaches to changing behaviour — for good.

The Power of Habits

Perhaps the most promising avenue for making behaviour change ‘stick’ is by changing our habits. Habits are automatic,

rotmanmagazine.ca / 21

Adding a desired behaviour onto the end of a routine that is already habitual is an effective way to create a lasting habit.

effortless and repeated actions that develop when the following cycle is repeated multiple times: A situational cue triggers a behaviour, and that behaviour triggers a reward. Exactly how many repetitions of this cycle are required to generate a habit remains an open question, and it is likely context-dependent.

Past research suggests that intervening to creating sustained behaviour change in the form of new habits requires the deployment of two kinds of strategies:

Targeting the situation. Strategies targeting the situation insert behaviour-triggering cues that are both interesting and obvious, making beneficial behaviours easier and more rewarding.

Shifting peoples’ cognition. The second type of strategy shifts cognitions, equipping people, for example, with ‘beneficial beliefs’. This allows them to forecast the consequences of their behaviours more accurately and act more adeptly.

Importantly, changing cognitions without changing the situation puts an inordinate burden on individual willpower — and as a result, there should be synergy in applying these approaches in combination. We will now review some of the most promising research-based strategies for changing behaviour for good.

1. TEACH PEOPLE TO CUE THEMSELVES. Ensuring that cues are established to reliably trigger desired behaviours is key to creating habits. One way to ensure cues are present when they are needed is by teaching people to cue themselves. When people form ‘ifthen’ plans about the behaviours they intend to engage in following a given cue, this robustly increases follow-through. An example of an if-then plan is: ‘If it is a weekday and I am about to leave the house for work, then I will make my own coffee instead of going to Starbucks’. If-then plans reliably promote followthrough on one-time behaviours, but they can also promote

sustained behaviour change. One study found that teaching students goal setting and planning skills improves attendance and grades in the following marking period. Together, this research suggests that to facilitate durable behaviour change, it is helpful to coach people to make if-then plans that put cues in place to trigger desirable behaviours.

2. PIGGYBACK CUES. Another way to ensure cues to trigger desired behaviours are reliably present is by ‘piggybacking’ desired behaviours onto existing routines. For instance, adding a desired behaviour (e.g., flossing, eating an apple a day) onto the end of a routine that is already habitual (e.g., brushing your teeth, having a cup of coffee) can be an effective way to create lasting habits. In one study, flossing habits were more effectively generated by encouraging people to floss after brushing their teeth, rather than vice versa.

3. CHANGE BELIEFS ABOUT BENEFICIAL BEHAVIOURS. People will do things that they believe to be valuable, and accordingly, one of the most powerful cognitive interventions available is to change beliefs about the likelihood of success. For example, teaching students that their abilities — including their intelligence — can improve with effort and experience has been shown to improve report card grades and course completion among at-risk groups. And showing students that ‘deliberate practice is difficult, but it is both doable and effective’ changes how they interpret the necessary frustration of attempting skills they have not yet mastered — particularly among low-achieving students.

Beliefs about ‘norms’ — the attitudes and behaviours of other people — also powerfully influence behaviour. For example, in one study, learning that many people were reducing their consumption of meat prompted more cafeteria patrons to order meatless meals.

22 / Rotman Management, Behaviourally Informed Organizations 2024

The Keys to Changing Behaviour for Good

4. MAKE BEHAVIOUR CHANGE EASY. Making it as easy as possible to sign up for valuable programs that facilitate behaviour change dramatically improves outcomes. For example, letting people enrol in a retirement savings program (so that a portion of every future paycheque is automatically directed to a retirement account) via a stamped postcard increased participation by 20 percentage points, and allowing sign-ups after a future pay raise produced a 78 per cent sign-up rate — boosting enrollees’ savings by 388 per cent over 40 months.

In other studies, providing high school seniors’ parents with help completing the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) while they receive assistance with tax preparation increased the rate at which those parents’ children completed two years of college by eight percentage points over a three-year follow-up period; and providing community college freshmen with reminders and encouragement to renew their FAFSA increased sophomore persistence by 14 percentage points.

5. MAKE GOOD BEHAVIOUR MORE ENJOYABLE. Research suggests that finding ways to make beneficial — but often unpleasant — behaviours (e.g., exercise, studying) more immediately enjoyable has the potential to promote sustained behaviour change. For instance, one study found that when people were only allowed to enjoy tempting audio novels while exercising at the gym, they visited the gym more frequently than a control group over seven weeks. This so-called ‘temptation bundling’ strategy helped make the act of exercising more fun by pairing it with an engaging audiobook.

More generally, combining good behaviours that can be unpleasant with enjoyable activities (e.g., scheduling get-togethers with a challenging relative at a favourite restaurant, doing household chores while listening to a favourite podcast) can promote behaviour change for good. Complementary research has shown

that persistence is increased on challenging-but-important goals by encouraging people to pursue those goals in fun ways. For instance, encouraging gym goers to choose a workout that is fun (e.g., a dance class) rather than pursuing the workout that is most effective promotes more persistent exercise. Similarly, playing music in a high school classroom to make studying more fun increased persistence on schoolwork. Overall, making good behaviour more enjoyable facilitates the association of a ‘reward’ with the behaviour, and such repeated rewards are key to habit formation.

6. REPEATEDLY REWARD GOOD BEHAVIOUR. Perhaps the most promising stream of research designed to promote habit formation has shown that repeatedly paying people to engage in a valuable behaviour or otherwise encouraging it (e.g., by conveying its popularity) for as little as a month can increase the target activity for many months post-intervention. In one study, paying students to visit the gym eight times over the course of a month rather than just once or not at all produced behaviour change that lasted long after that month (and the intervention period) ended. The students who had been rewarded for repeatedly visiting the gym worked out nine times, on average, in the following seven weeks, while other students went roughly half as often.

Several follow-up studies have since replicated the finding that rewarding repeated exercise over a period as short as one month can lead to sustained habits detectable up to a year later. Incentives aren’t the only reward that has yielded this result: Repeatedly alerting people to how their energy usage compares to that of their neighbours in comparable homes (‘social norms marketing’) also has sustained benefits after messaging is discontinued. Monthly energy reports with social norms information sent to residential homes for two years continued to reduce energy consumption for years after

rotmanmagazine.ca / 23

Situational Interventions

Situational Interventions Cognitive Interventions (repeat) (repeat)

CUE

CUE BEHAVIOUR

ROUTINE BEHAVIOUR OUR SOLUTION BEHAVIOUR REWARD REWARD

discontinuation, with only a 10–20 per cent attenuation of their benefits per year.

Finally, similar results have been generated by offering ‘regret lotteries’ — lotteries requiring measurable behaviour change by a given date to win. Regret lotteries have been effective at encouraging sustained weight loss and smoking cessation.

7. INTERVENE AT OPPORTUNE TIMES. Finally, the timing of an intervention matters. Research on the ‘fresh start effect’ shows that people are more prone to engage in beneficial behaviours like exercising, searching for information about dieting on Google, and creating a commitment contract on the website stickK.com at the start of cycles like the beginning of a new week, month, year or following birthdays and holidays.

How to Induce Future-Focused Thinking

Present-bias, or the tendency to over-weigh immediate gratification while under-weighing the long-term implications of a choice, is responsible for many errors in judgment. Specifically, presentbiased thinking has been blamed for societal problems ranging from obesity to under-saving for retirement. Following are a series of nudges designed to promote future-focused thinking in order to reduce the pernicious effects of near-sightedness.

CHOOSE IN ADVANCE. One means of reducing biases related to near-sightedness is prompting individuals to make decisions well in advance of the moment when those decisions will take effect. This strategy is impactful because of people’s tendency to make less impulsive, more reasoned decisions when contemplating the future than the present. Choosing in advance has been shown to increase support for wise policies requiring sacrifices, to increase charitable giving, to contribute to increases in retirement savings, and to increase the healthfulness of consumers’ food choices.

Another result of choosing in advance is that choices are made in a higher construal level mindset, which means they focus more on abstract (e.g., why?) rather than concrete objectives (e.g., how?). This has other by-products, however — for example, higher construal leads to greater stereotyping. Therefore, an important caveat to choosing in advance is that it may lead to greater discrimination against women and minorities, as demonstrated in a field study of decisions on whether to grant prospective graduate students requests for meetings.

In closing

When our daily, routine choices are sub-optimal, they can undermine just about every conceivable life outcome. And when poor choices accumulate, they particularly harm populations with fewer resources and less ‘slack’ — for whom seemingly trivial mistakes can spiral with remarkable speed (e.g., a small ailment goes untreated and becomes debilitating; the interest on small, unpaid debts accumulates to produce financial insolvency; a failing grade makes it difficult to justify studying for a degree over working full-time).

Sadly, adversity itself exacts a hefty physiological and psychological toll: When individuals perceive that the future is uncertain and threatening, they become biased towards meeting their short-term needs versus working towards long-term goals.

INCLUDE A PRE-COMMITMENT.

Because people tend to make more patient and reasoned decisions about the future, providing opportunities for individuals to both choose in advance and make a binding decision (or at least decisions where penalties will accompany reversals) can improve many choices. Research has shown many benefits from pre-commitment. For example, substantial savings increases result from providing individuals with access to bank accounts with commitment features such as a user-defined savings goal (or date) such that money cannot be withdrawn before the pre-set goal (or date) is reached. Although only 28 per cent of those offered such commitment accounts selected them when equivalent interest was available on an unconstrained account, average savings balances increased by 81 percentage points for those customers of a Philippine bank with access to commitment accounts. Recent research has also shown that pre-commitment can help people quit smoking, exercise, achieve workplace goals and resist repeated temptation in the laboratory. Pre-commitment is particularly valuable in settings where self-control problems pit our long-term interests against our short-term desires. When it comes to food, for example, pre-committing to smaller plates and glasses can reduce consumption.

BUNDLE TEMPTATIONS.

A new twist on pre-commitment called ‘temptation bundling’ actually solves two self-control problems at once. Temptation bundling devices allow people to pre-commit to coupling instantly gratifying activities

24 / Rotman Management, Behaviourally Informed Organizations 2024

As a result, solutions to enduring behaviour change carry universal benefits.

At present, organizations and academics are incentivized to work on behaviour change in isolation, focusing on a single setting, measuring success over the short-term. But there is an enormous untapped opportunity for large-scale, interdisciplinary work combining practical and theoretical insights to enable sustained improvements in daily decisions on a collective level.

As Aristotle said, “We are what we repeatedly do.” If our ultimate destinies derive from our daily habits, then the 21st century may be the first in which humanity learns how to change behaviour for good.

Angela Duckworth is the Founder and CEO of the Character Lab, a non-profit whose mission is to advance the science and practice of character development. She is also the Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, faculty co-director of the Penn-Wharton Behaviour Change For Good Initiative, and faculty co-director of Wharton People Analytics. Katherine Milkman is a Professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and holds the Evan C. Thompson Endowed Term Chair for Excellence in Teaching. She has a secondary appointment at U Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine.

This article is based on a paper made possible by support from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the National Institute of Health, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the John Templeton Foundation.

(e.g., watching low-brow reality television, receiving a pedicure, eating an indulgent meal) with engagement in a behaviour that provides long-term benefits but requires the exertion of willpower (e.g., exercising, reviewing a paper, spending time with a difficult relative). Such pre-commitment devices can increase engagement in beneficial behaviours like exercise while reducing engagement in guilt-inducing, indulgent behaviours.

ORGANIZATIONAL COGNITIVE REPAIRS. De-biasing can also be embedded in an organization’s routines and culture. Researchers call these de-biasing organizational artifacts ‘cognitive repairs’. A repair could be as simple as an oft-repeated proverb that serves as a continual reminder, such as the phrase ‘don’t confuse brains with a bull market’, which cautions investors and managers to consider the base rate of success in the market before drawing conclusions about an individual investor’s skill. Other examples include institutionalizing routines in which senior managers recount stories about extreme failures (to correct for the underestimation of rare events) and presenting new ideas and plans to colleagues trained to criticize and poke holes (to overcome confirmatory biases and generate alternatives).

Many successful repairs are social, taking advantage of word-of-mouth, social influence and effective group processes that encourage and capitalize upon diverse perspectives. Although cognitive repairs may originate as a top-down intervention, many arise organically as successful practices are noticed,

adopted and propagated.

One cognitive repair that has not only improved many organizational decisions, but saved lives, is the checklist. This tool could easily fit in many of our de-biasing categories. Like linear models, checklists are a potent tool for streamlining processes and thus reducing errors. A checklist provides a list of action items or criteria arranged in a systematic manner, allowing the user to record the presence or absence of the individual item listed to ensure that all are considered or completed.

Checklists, by design, reduce errors due to forgetfulness and other memory distortions (e.g., over-reliance on the availability heuristic). Some checklists are so simple that they masquerade as proverbs (e.g., emergency room physicians who follow ABC — first establish a irway, then b reathing, then c irculation). External checklists are particularly valuable in settings where best practices are likely to be overlooked due to extreme complexity or under conditions of high stress or fatigue, making them an important tool for overcoming low decision readiness.

rotmanmagazine.ca / 25

— From “A User’s Guide to Debiasing” by Jack B. Soll, Katherine Milkman and John W. Payne in The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making.

Behavioural Science on the Ground: A Global South Perspective

WHILE THE USE of behavioural science in helping organizations tackle applied problems, like the design and delivery of products, programs and services, was initially largely confined to the Western world, we are now seeing an increased use of behavioural science in the Global South. On the face of it, the infusion of funding into behavioural science research seems like a beacon of hope, promising to nurture a thriving ecosystem of researchers and practitioners looking to solve behavioural challenges in the Global South. A closer look, drawn from the experiences of behavioural science researchers in Africa, reveals a narrative far more nuanced and complex. It is a story of disparities in the distribution of benefits, a tale of local researchers and research institutions bearing the hidden costs (both direct and indirect) of this burgeoning field. Busara is a vocal boutique advisory that unlocks impact for organizations working in the Global South by helping them apply cutting-edge behavioural science specifically for the people and the contexts they serve. Drawing from the experiences of Busara, we examine the true price of progress in the field.

Navigating the Predictably Unpredictable Financial Costs

Unusual circumstances arising during a study can affect the time and financial costs of research implementation. Jennifer Adhiambo (Senior Manager, Busara) once ran a study that required participants complete surveys before and after their payday. How often could paydays exist? Once or twice a month? Jennifer encountered eight different types of pay-

day patterns in a pool of women participants. The schedule of the study had to be overhauled and the study, which was budgeted to be completed in a week, took a month. This was accompanied by an increase in costs.

Behavioural science projects are typically funded on the basis of predefined research goals, budget norms and implementation methods. In Africa, this approach to funding often lacks consideration for local realities. Funders, if they fail to consult experienced local professionals, may also hold misconceptions about the local context and fail to estimate project timelines and budget needs appropriately. The commonly held notion that research costs will be low, in keeping with African cost-of-living standards, can lead to wariness and suspicion in the funders’ mind and a refusal to accept practical advice about actual research costs.

In addition to Jennifer’s story, it is crucial to understand the dynamic cultural landscape in which research activities unfold. In contrast to their Western counterparts, many participants in the Global South often lack prior experience with experiments or surveys, necessitating extensive pre-experiment coaching and guidance in using technical tools. Issues like lack of punctuality and absenteeism are prevalent, influenced by factors such as transportation difficulties, opportunities for higher wages elsewhere, and weather conditions. Delays caused by latecomers can lead to demands for additional compensation from those who arrived on time. Furthermore, the burden of domestic responsibilities on women and gender disparities in some

26 / Rotman Management, Behaviourally Informed Organizations 2024

POINT OF VIEW

and

Jang

Anisha Singh

Chaning

One suggestion is to invest resources to truly reverse the top-down nature of the planning, design and control of most research programs.

regions can lead to reduced female participation, thereby skewing the research sample.

Although these incidents are predictably unpredictable, the answer to the question of who should bear the higher costs arising in such situations is unclear. Many times, the research agency bears the costs, a burden hard to carry given that research projects are extremely cost-competitive.

Many research agencies, having firsthand experience with the burdensome costs resulting from impractical budget constraints, approach research funding cautiously when dealing with those who hold unrealistic expectations that research costs will be cheap in African countries. When these funders rely on notions of what costs should be, they often resort to working with local organizations who provide data on their terms. This can lead to the production of unreliable data through oversampling of easily accessible urban populations, rather than sampling from the more challengingto-reach and isolated communities that should be the true focus of the research.

The effects of such pseudo-data gathering add up in the medium- to long-term and it is the communities most in need of development-directed research which tend to suffer. Nathanial Peterson (Vice President, Busara) quotes the example of northern Nigeria whose population of approximately 100 million is about twice that of Kenya. Northern Nigeria is highly understudied and very much in need of research that could improve development efforts. Yet Nairobi, given its proximate location and other factors which make it an easy place to sample, has a sampling rate almost 100 times greater than Northern Nigeria.

Clearly then, taking the reality of African life into consideration in the design of research programs is necessary to obviate such adverse and unwanted outcomes.

Much Needed Flexibility to Fund the Future

Funding for research is often insufficient and primarily allocated to direct costs that include operational aspects like data collection. Consequently, researchers and organizations are left to shoulder the substantial costs involved in literature surveys, publishing, and presenting results from their own salaries. The challenge of building capacity and making internal improvements becomes even more pronounced when budgetary inflexibility prevails.

Research funding programs, especially those originating in Western countries for the broader Global South re-

gion, often prioritize capacity building; however, achieving this goal is difficult. Top institutions in the U.S. and Europe enjoy substantial overhead allowances, along with significant endowments, adept project management, administrative expertise, long-standing leadership, and a wealth of institutional knowledge amassed over decades, if not centuries. This starkly contrasts with research centres in the Global South, struggling to provide such resources within their limited overhead allocations, which typically fall around 15 per cent.

Moreover, often absent from project budgets is an allocation of funds toward the improvement of the research process itself. As the move toward greater localization gathers momentum, there is a growing realization of the possible danger that the changes being implemented may actually represent tokenistic rather than effective localization. Effective localization enhances the effectiveness of development efforts by shifting power, resources and ownership from international actors to local communities. Simply employing more local talent may not always be enough, says Megan Grazier (Director, Busara), who, along with others at Busara, is involved in meta-research, or research about research, with the aim of improving research processes. The idea, she says, is “to internally unpack some of the challenges to make sure the research processes are contextually appropriate to all the stages.” This proactive approach to applying behavioural science internally often falls on the organizations themselves.

This leads to a fundamental question: How can emerging research institutions in other parts of the world reasonably aspire to develop similar capacity and quality without the flexibility to allocate financial resources and establish institutional infrastructure as needed?

Budgeting For Intellectual Aspirations

Universities are supposed to both impart knowledge and generate new knowledge through research. Francis Meyo (Vice President, Busara) takes the example of an institution running courses relating to behavioural science. Such centres are thinly spread across African countries and typically have faculty-to-student ratios that are much higher vis-a-vis the West. In addition, academics in the Global North (unlike those in the Global South) might also have access to support like research and teaching assistants, graduate students and administrative assistants. This contributes to a growing

rotmanmagazine.ca / 27

disparity in what can be accomplished with the resources at hand for academics and trainers in African countries. So when program funders, including major institutional funders, have a policy of routing their (often substantial and long-term) funding only via local academic institutions, such funds often absorb the complete resources of these African centres, leaving little opportunity for them to initiate any research with local focus and relevance.