Kick Back on Route 66

Point your smartphone camera at this QR code to find out more about things to do in Springfield.

Here, the holidays stir magic. A flapper girl perched atop a beaming moon lights your way to storybooks and sci-fi gems. 100 years later, an Art Deco hotel stands tall on the skyline it shaped. Asian fusion flavors mix and mingle to make your spirits bright. And a lush botanic garden is reimagined as a luminous board game, exuding glee in every hue.

Imagine that.

SHOP EAT STAY

DECOPOLIS Discovitorium Tulsa Mayo Hotel Tulsa Yokozuna TulsaPlan a getaway that sets your soul aglow. Spark inspiration at TravelOK .com.

Order or download your free Route 66 Guide & Passport at TravelOK .com.

Philbrook Museum of Art Tulsa

Philbrook Museum of Art Tulsa

WHERE THE MOTHER ROAD BEGINS

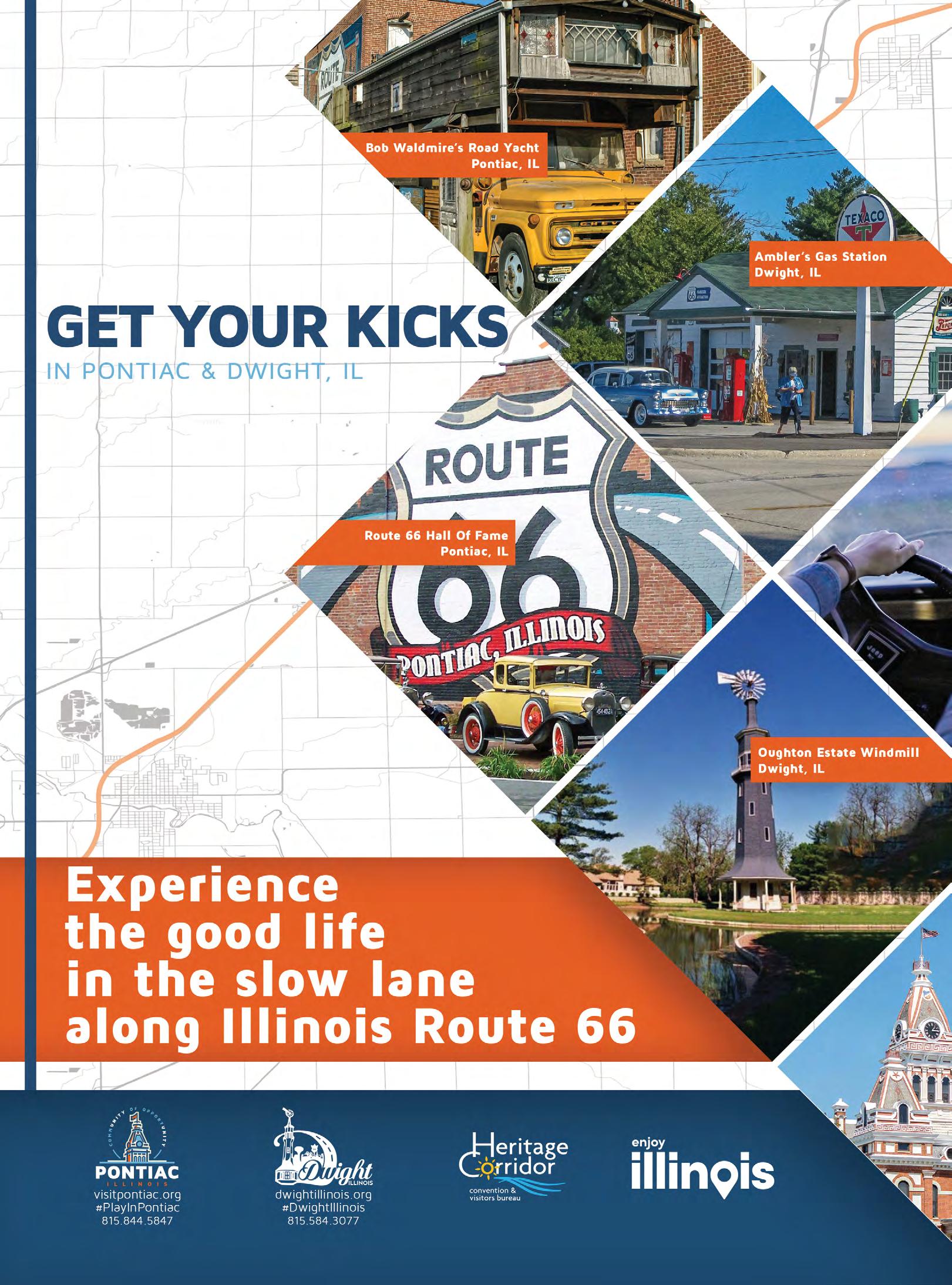

Route 66 defined a remarkable era in our nation’s history – and it lives on today in Illinois’ Route 66’s many roadside attractions, museums, and restaurants –it’s the shining ribbon of blacktop we call ‘The Mother Road’.

Start planning your trip now at www.illinoisroute66.org. Request a visitor’s guide by emailing info@illinoisroute66.org and make sure to check out our mobile app by searching for ‘Explore Illinois Route 66’ in the App Store and Google Play, to help with all of your Route 66 Illinois planning.

Tel: (217)-414-9331 • www.illinoisroute66.org

CONTENTS

24 At the River’s Edge

By Cheryl Eichar JettThe almost 100-year-old Elbow Inn’s story has as many twists and turns as the river that runs next to it. Branded early on as the Munger-Moss Sandwich Shop, that well-known name traveled on down Route 66 to Lebanon where it also stuck to a now-iconic motel. But the family that’s owned the Elbow Inn since the late ‘40s is about to make the name Thompson just as recognizable.

30 A Real Legacy

By Rich RatayThe El Rancho Hotel reflected the majestic beauty of the Southwest and thrived due to its Hollywood movie studio connections, but fell on hard times when low-budget westerns began filming on studio back lots and even in Italy—remember “spaghetti westerns”? Read about the amazing Ortega family who literally came riding in just in time—the wrecking ball was in the hotel parking lot.

46 A Conversation with Linda Ronstadt

By Brennen MatthewsMusic is filled with legends, and no female artist stands out any brighter from the heady 1960s and ‘70s than Linda Ronstadt. From 18-year-old newcomer to the LA music scene, armed with her father’s 1898 Martin guitar, to her last stage concert in 2009, as her voice prematurely gave way, Ronstadt sang with a long list of some of the brightest musicians of the era. Read about her triumphs and tragedies in this candid and intimate interview.

54 Clanton’s Cafe

By Mike VieiraAs Oklahoma’s longest-running family restaurant, Clanton’s is a Route 66 institution. From the eatery’s early days, when founder “Sweet Tator” Clanton stood in the street and banged on a pot to attract customers, to the corporate experience of the current generation, this culinary landmark is still in the capable hands of the Clanton family.

64 Frank’s Place

By Nick GerlichAs the highway alignments through tiny Williamsville, Illinois, changed, so did the ownership of the village’s gas stations. But one became known in the early 2000s as a memorabilia shop called The Old Station, although mostly everyone just knew it as Frank’s Place, for its friendly, extroverted owner. Frank is retired these days, but now Jason Hayward has put his stamp on the shop with his own relaxed style and ever-changing array of relics.

ON THE COVER

Pontiac, Illinois. Photograph by Efren Lopez/Route66Images.

In my books, 2022 lumbered on by, very slowly. For some of you, perhaps the year cruised on past. But one thing is for sure, December marks the end to what has been a fascinating year. Personally, I am so grateful for so many things. Although I am happy to see 2022 go, I am ready for Christmas holidays and for some joyous time with friends and family. I love the festive season, with the decorated houses and Christmas tree shopping. I adore watching the excitement in my son’s face when he tries to guess what is stashed away beneath the colorful wrapping paper and boxes, and I am especially moved by the extra little bit of kindness that many people seem to show during this time of year. Alas, I wish it was always this way. But I am also excited for 2023 to arrive with all of its promises. I am always energized to see what a new year will bring, and 2023 has many exciting things in the works.

One of the most exhilarating things that has happened this recent fall was the release of my new book— Miles to Go: An African Family in Search of America along Route 66 —that hit shelves and homes in October. It is my first book, and it has been an amazing experience listening to readers’ responses as they journey with me and my family on our very first trip down Route 66. It was a time of exploration and uncertainty. It was a time of discovery of both Route 66 and America. I hope that you will all grab a copy this season and dive into America with us. If you love a great America-focused road travel story that is filled with fascinating history, lots of diverse culture, and a ton of hilarious, and at times, deeper human connection, Miles to Go may be up your alley this Christmas season.

And not only Miles to Go. There are a lot of really great Route 66-focused books on the market. Why not order a number of them now and support passionate Mother Road writers and artists while filling your bookshelves with some really important literature? I know that 2022 has been a financially challenging year for most of us, but be kind to yourselves and those around you and make an important investment that will allow talented writers to continue to create fabulous books that will help promote and preserve Route 66 into the future. We really do need your support.

Without a doubt, on each of our trips, that first one, and every subsequent, it has been the unique and friendly people that we met along the way that really made each journey down Route 66 extra special and memorable. America is a country of ideas, but equally, it is a country of people, people with surprisingly shared values and ambitions. America’s diverse beauty is not limited to its history, landscapes, and culture. It is especially obvious in its people. I have been saddened in recent years to witness so much effort by some media outlets and institutions to divide us, but traveling across two-lane America, one can only come to one clear conclusion: there is much more love and similarity that unites us than differentiates us. In 2023, let’s focus much more on that and be the vessels that demonstrate the love that we all naturally have to offer.

As we close the year, we want to bring you some stories that have perhaps not been told enough but are no less fascinating than those that have been told often. It is with great joy that I welcome each of you to flip open this issue and explore some people and places that represent a quieter side of the Mother Road. These are destinations whose stories have been woven via the lives and deeds of a great many people. They are spots that are still luring in travelers today. Help us celebrate their lives and stories.

If you haven’t yet, remember to follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for much more entertainment, stories, and updates. Also visit us regularly online to check our digital-only content and stay connected.

Have a safe and wonderful festive season.

See you down the road, Brennen Matthews

Editor

PUBLISHER

Thin Tread Media

EDITOR

Brennen Matthews

DEPUTY EDITOR

Kate Wambui

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Cheryl Eichar Jett

EDITOR-AT-LARGE Nick Gerlich

LEAD EDITORIAL PHOTOGRAPHER

David J. Schwartz

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Tom Heffron

EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS

Lauren Sanyal

Mitchell Brown Rachel McCumber Shannon Driscoll

DIGITAL Matheus Alves

ILLUSTRATOR Jennifer Mallon

CONTRIBUTORS AND PHOTOGRAPHERS

Billy Brewer Braydon Bell Chandler O’Leary Efren Lopez/Route66Images Gregory R.C. Hasman

Jason Henry Megan Buchbinder Mike Vieira Noah Wulf Rich Ratay

Editorial submissions should be sent to brennen@routemagazine.us To subscribe visit www.routemagazine.us.

Advertising inquiries should be sent to advertising@routemagazine.us or call 905 399 9912.

ROUTE is published six times per year by Thin Tread Media. No part of this publication may be copied or reprinted without the written consent of the Publisher. The views expressed by the contributors are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, or service contractors. Every effort has been made to maintain the accuracy of the information presented in this publication. No responsibility is assumed for errors, changes or omissions. The Publisher does not take any responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts or photography.

Annie’s Got Her Gun

There’s a man in the distance with a cigarette in his mouth. A woman stares him down through a Marlin model 1897 lever-action rifle barrel. She pulls the hammer back, squeezes the trigger, and a controlled explosion erupts at the end of the gun. She hits her target dead-center, just as she always does. The target remnants fall to the ground as the man spits what’s left of the cigarette out of his mouth to the thunderous applause of an audience. They’ve seen Annie Oakley, a legend of the West, show off her marksmanship skills, and they don’t leave disappointed.

Like many legends, the highest accomplishments come from the humblest of beginnings. Her skill with a firearm was born out of necessity rather than ambition. Born Phoebe Ann Moses in Darke County, Ohio, on August 13, 1860, Oakley had to learn how to provide for her family early on. Her father, Jacob Moses, died when she was six, and her stepfather, Daniel Brumbaugh, passed away the following year. By the age of eight, she was hunting small game with her father’s rifle.

“In the American West, contract meat hunters, that’s their sole job, providing game on the table; she did it not only for her survival but for her siblings,” said Michael Grauer, McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture and Curator of Cowboy Collections & Western Art at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum. “In this case, she helped raise her siblings and put a few dollars in her pocket.”

Eventually, Oakley earned more than a few dollars, because, by the time she was fifteen, she was paying the $200 mortgage on her mother’s house by selling the meat that she hunted to the Katzenberger brothers’ grocery store in Greenville, Oklahoma. It was then sold to restaurants and hotels in Cincinnati. Because of this, she received an invitation from hotel owner Jack Frost to participate in a shooting contest against Frank Butler, a well-respected marksman who offered challenges to locals. Out of twenty-five shots, Oakley made every single one she took. Butler missed by one.

The two of them would marry in 1876, eventually becoming a performance act after Oakley substituted for Butler’s sick partner in a show in 1882. On the road, she changed her name to “Oakley,” based on the town of Oakley, Ohio. They performed in several tours, including

the Sells Brothers Circus, but Oakley became famous when they performed for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. They performed all over the country and overseas, going to countries such as Spain, England, Italy, and France. This is when Oakley became a renowned sharpshooter and offered a shift in the dynamic between herself and Butler. She became the star headliner instead of part of a traveling duo. Still, Butler remained a proud and loyal husband.

“They were true equal partners, and there was no resentment on Frank’s part. I think he realized that she was the better of the two. He became a manager and promoter, and mainly her assistant. I think that speaks to their marriage being a true partnership,” said Grauer.

Oakley became widely regarded for her ability to shoot small objects from far distances, items such as dimes and British pennies that were thrown in the air, aiming at targets using a mirror, and quite dangerous stunts like shooting a cigarette out of her husband’s mouth. Her speed was impressive, considering that she predominantly used shotguns and rifles, never sidearm.

Throughout her life and career, Annie Oakley became widely known for her crack shot skills, often surpassing the skills of the men she would compete against, which gave her worldwide accolades.

“Her costume that she wore in her performances was just covered with medals. She received medals from European countries, cities where she performed, and so on. I don’t think any particular one was of higher stature than another, but they were all acknowledgments of recognition,” said Grauer.

Oakley gained respect from those she encountered, especially Hunkpapa Lakota leader Sitting Bull, who admired her skills and assertive confidence and would refer to her as Wayanya Cicilla or “Little Sure Shot.” Her life and achievements have been made into the famous Broadway musical and film Annie Get Your Gun, and her rifles are on display at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. Despite the hardships of her youth, her experiences shaped her into the person she would become—one of the great American sharpshooters, and a true legend of the Old West.

WALDMIRE’S BUS

The Mother Road contains multitudes of wacky artifacts and historical sites that weave through Illinois to California, but perhaps what is just as important are the loyal “66-ers” that travel the road each year. On Route 66, there is perhaps no bigger roadie-legend than artist and free spirited Bob Waldmire. For a time, Waldmire was best recognized for his iconic ’72 Volkswagen microbus that he bought in 1985, which served as the inspiration for the hippie-van character “Fillmore” in the 2006 animated Pixar movie, Cars. Waldmire, however, was always looking for the next adventure, and something much bigger—a home-on-wheels as a matter of fact—was at the forefront of his mind.

In December of 1987, Waldmire stumbled upon a 1966 Chevrolet school bus while driving through New Mexico and promptly sent a letter home to friends and family in Illinois.

“Along the way in Grants, New Mexico, I spotted and quickly fell in love with the vintage, rust-free, 1966 Chevy School Bus, which I have in mind to convert into a homestudio road-show mobile-environmental resource. I hope that is rather self-explanatory,” the letter said.

Self-explanatory, yes. But, a home-studio road-show? What did that even mean? Well, a total reinvention ensued of the ‘66 school bus into a fully functional living space with a wooden second story. Modern day van-lifers’ creations pale in comparison to Bob’s great two-story Road Yacht, now laid to rest in the parking lot of the Route 66 Hall of Fame and Museum in Pontiac, Illinois.

“[An eccentric friend of] Bob’s showed up at our farm home in Rochester, in a school bus that he had converted to his homestudio-everything,” said Buz Waldmire, Bob’s older brother. “That’s where Bob first got the idea of getting a school bus and turning it into that… he was out-growing his VW van.”

Once back in Illinois, Bob had many hands to help him with his big conversion. “Creating that bus was kind of an adventure,” said Buz. “It was like a bunch of kids building a treehouse.”

In the early days of the bus, Waldmire’s mother had helped with the interior design, but over time the look changed as

he continued his travels and artistry, collecting mementos along the way. “Every part of the bus reflects Bob,” said Buz. “I mean, the solar shower … his self-composting toilet—which is one of the few technological things in the bus—his hand-made shelves, his dozens and dozens of reference books, containing information from birds, habitat, animals, mushrooms, human anatomy, diseases, insects. He researched everything he drew or thought about.” While down-sizing considerably from a modern home, he kept the most important parts of his identity and essential modern appliances within the home Road Yacht.

The bus sustained several cross-country road trips as Waldmire split his time between Hackberry, Arizona, and the Springfield, Illinois, area. He was undeniably a man on the move, and his carriage was the bus. For many local Route 66-ers, it became an enjoyable pastime, looking out for when Bob Waldmire may pass through town on his yacht.

“I’ve had a lot of travelers, visitors, who say, ‘It must’ve been great to live the kind of life he lived!’” said Buz. “Because he went where he wanted, when he wanted. I mean, that’s kind of a dream that a lot of people think about.” However, towards the end of his life, Bob parked his bus on his family’s farm and lived where he had started his project so many years earlier.

After the beloved and well-respected artist died of cancer in 2009, the Road Yacht, full of everything Bob had used while living inside of it, took its last trip—to Pontiac, Illinois. While it hasn’t moved in thirteen years, tourists come from all over the world to get an inside look into the life of the Route 66 legend. Visitors to the museum are invited to learn more about Waldmire and his evolution as an artist in the Bob Waldmire Experience on the second floor of the museum building. Bob Waldmire is now long gone, but the unencumbered, carefree way that he lived his life is still speaking to people from around the world, and there may be no better symbol of this than his much-loved Road Yacht. Bob would have liked that.

Pics On Route 66.

ON THE BIG SCREEN

There’s a certain allure to the movie-going experience. Filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino and Christopher Nolan champion the social aura that movies create when seen in an auditorium filled with people. But amid this social philosophy, a more niche experience garners its own merit — that of the drivein theater. While created before World War II, drive-in theaters gained popularity in the 1940s with the increased democratization of automobiles. Their popularity continued to rise through the ’50s for families and romantic dates, thanks to the privacy and lower ticket cost compared to traditional theaters. Attendance, unfortunately, took a dive with the advent of the home video market and the rise of cable TV in the 1980s. But in Illinois, about a half-dozen locations, including three on or near Route 66, still keep the spirit of the drive-in theater alive. One of these, in the capital city of Springfield, already claimed a storied past, even before being re-opened in 2002.

The Springfield Twin Drive-In opened on the south side of Springfield in 1973 — a late-comer in the drive-in theater business — before becoming the Green Meadows Drive-In a couple of years later, and then closing in 1980. In 1992, the Knight family, owners of the neighboring Knight’s Action Park, realized the opportunity right next door after a dozen years of the theater’s dormancy. But it was ten more years before the drive-in finally reopened its gates as the Route 66 Drive-In in 2002, just in time to coincide with the 50 th anniversary of their Knight’s Action Park business.

“It was a nice extension of what we were already doing over at the park,” said Doug Knight, owner of Knight’s Action Park, “We favor a safe place where families can go together and have a good time, and the drive-in seemed like an easy fit for that.” And it added to the fame and appeal of the Knight family’s business reputation in the Springfield area — Doug Knight is one of the “Living Legends,” Visit Springfield’s tour of their most legendary local entrepreneurs.

Perhaps beyond initial expectations, the opening two seasons of the drive-in were so strong that a second screen was added. Although the original speakers were gone long

before Knight acquired the destination, patrons now use their radios to tune into 91.3FM for Screen 1 and 106.3FM for Screen 2. The location itself is over twelve acres in size, and each screen can hold 252 cars. Those are a lot of moviegoers. Consequently, the screens have to be big enough to accommodate such a large audience, which is why they’re each 40-by-80 feet in scope. The sheer volume of the park was fortuitous for massive numbers of patrons for almost two decades, but then, a storm cloud approached.

In 2020, like many other businesses, movie theaters were affected heavily by the pandemic. While closed entirely during the early weeks, the theater was able to open back up in early May 2020, albeit with strict guidelines. Tickets had to be bought in advance, audience members couldn’t sit outside their cars, food could only be ordered through the FanFood app, and only 125 vehicles were allowed per screening. None of this mattered much, considering that the studios could only trickle movies out to theaters instead of flooding the market with blockbusters as they normally do during the summer.

However, attendance has been steadily improving, and they’re open rain or shine during the season — which currently runs from April 1st to October 24th. “In this last year, we’ve seen quite a bit of improvement with the number of guests we see come in,” said Knight, who’s still hopeful about the drive-in’s future. “We always have a few regular customers who come to the drive-in religiously at least once a week for the fresh popcorn and the experience.” With the limited number of major releases, they’ve turned to classic films to fill the parking spaces, such as Jaws, Jurassic Park, and Twister.

“The drive-in is more of a family experience than anything,” said Knight. “You get to have your own space; families can bring the kids. I see it all the time where the young ones come in wearing their pajamas.” That’s ultimately what makes drive-in theaters unique — they offer an experience that’s both communal and intimate at the same time. While movie theaters may continue to struggle with the availability of streaming and same-day releases, loyal fans remain who want to see their favorite movies under the clear, open Illinois sky.

HOME OF TH

Photograph by David J. Schwartz - Pics On Route 66

Photograph by David J. Schwartz - Pics On Route 66

E CAVALRY

Amidst the great plains of the state of Oklahoma, in Canadian County there stands a permanent fort that was established in 1874. It’s the historic Fort Reno. Created 33 years before President Theodore Roosevelt issued Proclamation 780, granting statehood to Oklahoma, it’s a symbol and a lasting reminder of America’s weathered history following the Civil and Indian Wars, as well as the second World War. It represents the country’s ability to evolve and progress through adversity, especially following the trials of war, and demonstrates the civility and compassion that can be shown—even to one’s own enemy.

After the Civil War ended, the Union Army turned its attention to the West and its inhabitants—multiple Indian tribes—and its land. Officers and soldiers who survived the War between the States were sent west, charged with creating Indian agencies and forts to help keep the peace as settlers from the East moved onto land that the tribes occupied. The Darlington Agency, named for the area’s first Indian Agent, a Quaker named Brinton Darlington, was located at Fort Supply, which was established in the winter months of 1868 and located over 100 miles away to the northwest in Indian Territory, near what is now the corner of the Oklahoma Panhandle. However, additional assistance and protection was needed following the signing of the Treaty of Medicine Lodge, which was intended to remove the natives from the path of American expansion and avoid costly wars. As a result, soldiers established the military encampment that preceded Fort Reno, but aid was still needed for the Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho tribes after the conflict ended.

“Fort Reno was being used to control white encroachment after the signing of the Treaty of Medicine Lodge in 1867,” said Craig McVay, retired educator and member of the board of directors for the U.S. Cavalry Association, located at Fort Reno. “Those reservations were set aside as hunting grounds for the natives. The forts maintained the peace for twenty to thirty years.” In February of 1876, the fort commander, General Philip Sheridan, named the fort “Reno,” after his friend, Major General Jesse L. Reno, who was killed in 1863 at the Battle of South Mountain during the Civil War.

On April 22, 1889, the first Oklahoma Land Run brought thousands to scramble for a quarter-section (160 acres) of land apiece in what would become a half-dozen Oklahoma counties, including Canadian County, home of Fort Reno. Nearby, the town of El Reno sprang up on the south side of the Canadian River with the influx of settlers. Additionally, a community named Reno City was also established, with one community on each side of the Canadian River. But when the railroad announced that their rail lines would be built on the south side of the river, the residents abandoned Reno City and relocated, combining the two towns, which grew into the Canadian County seat.

Beginning in 1908, Fort Reno transitioned from a military post to one of three army quartermaster remount stations for the military, which specialized in horse breeding and training pack mules. The fort herded over 14,000 horses and mules on

the former fort’s grounds and transported them worldwide by rail throughout World War I and II to locations including Burma, China, and the South Pacific. These animals became invaluable during the war when soldiers were located in mountainous terrain.

The fort perhaps became most well-known for its operational use during World War II as an internment work camp for over 1,300 German and Italian prisoners of war who were captured in Africa. “They had a commissary, a movie theater that played features in German, a library, and they had three square meals a day,” said Deborah Kauffman, full-time volunteer and president of Historic Fort Reno, Inc. “If they wanted to work, they were allowed to work for farmers in the area with supervision, and they were paid.” Their presence in the camp eventually led to the development of the Historic Post Chapel on the compound in 1944, which was built by the prisoners themselves. Now a historical landmark on the National Register of Historic Places, it was then regarded as a well-hidden location in the rural area of Canadian County, away from any military activity in Oklahoma City. Now, the rather quaint European-style chapel is popular for military or westernstyle weddings.

After World War II finally ended, the need for thousands of military animals declined, and the necessity of housing hundreds of prisoners of war disappeared, and once again, the fort was repurposed. The remount depot was decommissioned in 1948, and the facility was turned over to the U.S. Department of Agriculture for its uses. Since then, the fort has been the site of the U.S.D.A.’s Grazing Lands Research Laboratory for the Great Plains.

The complex was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970. Today, the Fort Reno Visitor Center and Museum is an essential aspect of the site, and Historic Fort Reno, Inc.—a non-profit organization—is responsible for its upkeep. The board members, consisting of seven individuals, including Kauffman, are always looking for volunteers to act as historical interpreters, help maintain the site, or perform as re-enactors. “We are vigorously working to find ways to preserve Fort Reno. If we don’t find ways to raise money to restore and maintain it, then due to safety factors, buildings will have to come down,” said Kauffman. “We always tell our visitors that [their] admission is helping us keep this place open.”

Like many other historical buildings and locations around the country, one can always rely on recorded incidents of paranormal sightings to pique interest. One such incident occurred in the summer of 2022. “We had a picture taken of one of our re-enactors on the steps of the Post Chapel,” said Kauffman. “And in the picture, we caught an image of a boy standing behind her with an orb in his chest.” You can learn chilling stories from Fort Reno’s long history while exploring the site, guided by lantern light. Ghosts or not, this site has marked undeniably important eras of American history, and any spirits, real or imagined, might just be a reminder to make sure that the history of the diverse people that worked, lived, or were held there, is never forgotten.

AT THE RIVER’S

By Cheryl Eichar Jett Photographs by David J. Schwartz - Pics On Route 66

RIVER’S EDGE

all bluffs and a verdant tree line form a backdrop for the nearly 100-year-old wooden building. Just below and behind the old inn flows the temperamental Big Piney River, bending and twisting into the shape for which it was named by lumberjacks attempting to float logs around the “devil’s bend.” The river has raged here, more than once, but more often, it gurgles peacefully under the historic iron bridge, setting the scene for the old sandwich shop with roots about as deep as the trees behind it that grasp at the river’s bank. Although the earlier name of the place—the MungerMoss Sandwich Shop—still resonates with travelers, the name of the family that has hung onto it since the late 1940s is actually Thompson.

Through floods, hand-offs in operation, and its complete bypass by the highway through the iconic Hooker Cut, the original building and its later add-ons have mostly stood fast, enduring what fate doles out. Members of the Thompson family are determined to shore it up, open it up, and make it last another 90-plus years. This is the inn’s story, with enough twists and turns to match the river’s course.

The Munger-Moss Sandwich Shop

In 1929, Howard Munger and his wife, the former Nelle Draper, built and opened a tavern and sandwich shop with the river flowing behind them and a young U.S. Highway 66 running in front of them at Devils Elbow, near the small resort they owned. It was an exciting time. However, Howard unexpectedly died the following year, leaving Nelle to operate their business without her husband. But not for long. Nelle Munger remarried in May 1936 to Dixon resident Emmett Moss; she was 59 and he was 56. The couple made their home at the resort and renamed the eatery the Munger-Moss Sandwich Shop. The eatery became famous for its delicious barbecue and attracted not only locals, but also travelers on old Route 66, and the business prospered. About 1940, a wing was added to the northwest end of the building, nearly doubling their space. Life was good again.

But then came World War II and the uptick in U.S. military build-up, manufacturing, and transport. In June 1941, nearby Fort Leonard Wood was completed and opened. The dramatic increase in traffic during the early 1940s necessitated the construction of a four-lane highway—without the quaint but difficult twists and winding turns of early Highway 66 through Devils Elbow. The resulting construction produced Hooker Cut—a 91-foot slice down through Hooker Ridge, at that time the biggest road cut in the country. The smooth, straight new four-lane road through the cut facilitated traffic and avoided Devils Elbow, preserving the little community’s primitive charm, but of course, it also mainstreamed travelers away from its businesses.

With both their through traffic and youth gone, Nelle and Emmett sold the Munger-Moss Sandwich Shop business to

TPete and Jessie Hudson in 1945. Business clearly turned out to be no better for the Hudsons, and just a few months later, they packed it up and moved it to Lebanon, nearly 40 miles away down 66, carrying the Munger-Moss name along with them. There, they purchased the former Chicken Shanty site and set up their sandwich shop. The next year, they began to expand the business by constructing a 14-room cabin court, which later became enclosed as a modern motel branded with the now-iconic MungerMoss neon sign. In 1971, the Hudsons sold out to the now-legendary Bob and Ramona Lehman, a young couple from Iowa with four children. The Munger-Moss business name stayed in Lebanon, touted to this day on the splendidly restored neon sign in front of the still-operating Munger-Moss Motel.

But back to the bypassed Devils Elbow—in the late 1940s, a new owner arrived on the scene, whose family members would hang on to the property up to the present day.

The Thompsons Arrive

Missouri native Paul Cecil Thompson was born in 1895, served in World War I, met Gussie Clements while he was stationed in Minnesota, and married her in 1919 after the war was over. They moved to Springfield, Missouri, for over 20 years before Paul and Gussie’s marriage ended and Paul moved to Pulaski County, where he met Nadean, his second wife. Paul actually moved into the old sandwich shop building for somewhere to live, before purchasing the 45-acre property for $3,500 and opening the cafe back up as the Elbow Inn. He and Nadean would run it, accompanied by her son Ernie and his son Harold, both in their teens.

“It was my great-grandfather Paul Cecil Thompson that purchased it back in the ‘40s,” Amanda Thompson-Miles, current owner of the Elbow Inn, said proudly. “A pretty interesting character. He was kind of a jack-of-all-trades as a lot of men were back then. He was in World War I and went to France. And he actually played the French horn. Unfortunately, I never got to meet him.”

Nelle and Emmett Moss, with their Devils Elbow property sold, their former business name doing just fine down in Lebanon, and old age looming, left Devils Elbow. By 1950, they had moved 20 miles east to Rolla, where they had gotten married 14 years earlier. Nelle soon suffered from health problems and died in 1957; Emmett sadly followed in 1966.

Back at the Elbow Inn, Paul is remembered as a jokester, setting water glasses in front of customers along with a quip that “the river had cleared up.” Sometime in the 1960s, they added the second wing on the other side of the original building and Paul’s son Harold began to help out at the inn as Paul aged. By this time, with the two wings added on and with the lower level tucked under the building and accessible on the river side, it had become an accepted residence as well as business and would continue to serve on and off in that way for years to come.

“When Paul passed in 1973, the property passed on to my grandfather, Harold, who we called ‘Jug.’ He got that from his mom because when he was [a toddler he] kind of wobbled around on the floor like a jug,” said Amanda. “And then when he was in the Navy during Korea, he liked to make hooch on the ships, so the nickname stuck.”

After his father’s passing, Harold and his wife, Carol, operated the restaurant and bar until 1978, when it all got to be too much, and they simply closed it to the public for nearly 20 years.

“They had their own careers, so they ran it as a side business. Then it wasn’t operated anymore, and basically, [that was] the end of what we call the tavern. That’s just our family name for it. It served as a residence for different family members over the years; my own father lived there for quite a while before he passed away,” Amanda recalled.

The Business is Farmed Out—Twice

In 1997, the Thompsons agreed to sell the business—but not the property—to retired Army veteran Chris Leaverton and his wife Nicki. “They were really successful. They ran it very well,” Amanda complimented them. “And they were good friends of our family, [but] then they decided that they wanted to move on and open their own place across town.”

Next, after the Leavertons reopened elsewhere, Terry and Susie Roberson were interested. In 2006, they opened as the Elbow Inn and BBQ Pit. “That’s, I think, what people are most familiar with now, their version, which became kind of known for the bras [pinned to the ceiling] and biker culture. And, you know, everyone had a great time there and they kind of did their own thing,” said Amanda. “I wasn’t in the state at the time and my family was kind of scattered here and there. My grandma passed away. My grandfather got sick, and he went to live with my aunt in Kentucky, and Terry and Susie had kind of free rein during that time.”

A Hundred-Year Flood

In late April into the first few days of May 2017, torrential rains hit Missouri and the state’s rivers began to rise to record levels not seen in a hundred years. The Big Piney River (the largest tributary of the Gasconade) running through Devils Elbow was no exception, and the Thompsons’ picturesque plank-sided eatery—at that time still under the management of the Robersons—sat in water nearly to its roofline.

Ironically, portions of Devils Elbow had been listed as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places shortly before the flood.

“The community did come together and do a lot of work to get the tavern open. It was done really quickly and so some things, you know, were just kind of overlooked. [The water] was up to the roof. I hadn’t [ever] seen a flood like that,” said Beth Wiles, Executive Director of Pulaski County Tourism Bureau, has been following the ups and downs of the Elbow Inn for a couple of decades now, while keeping its iconic status in the minds of both domestic and international tourists.

“The terrible flooding almost covered the entire building, which, if you go on a normal day, you would never dream the river could get that high. So, it’s sustained considerable damage,” said Wiles. “Terry [Roberson] tried to work through that process at least a good year and a half, just trying to do whatever he could, and they had a lot of volunteers that came together to help with cleanup. But I think damage was so severe to some of the basic parts of the structure that they had to go in a different direction.”

It’s a Family Thing

After Harold passed away in 2017 (ironically just before the flood), Amanda’s desire to run the Elbow Inn as a family again resurfaced and only grew stronger after talking it over with her Aunt Pamela Thompson—the only surviving child of her grandparents and now the family matriarch. She too found that she wanted to try her hand at restoring her family’s historic eatery.

“So, after Grandpa passed away, we decided that we would part ways with Terry and Susie and try to rehab and renovate the [business] and reopen it and run it as a family business. October of 2018 is when we parted ways. We shut the doors and our intention was to reopen as quickly as possible, but we’ve discovered that that’s easier said than done,” mused Amanda. “The tavern was built in 1929 and it’s been through many floods. And back when folks were building things in the ‘20s, it’s not like everything was level and plumb. So of course, we’re running into interesting challenges and trying to figure out creative ways to address them. It’s definitely gone a lot slower than we had anticipated.”

After the Thompsons alerted the Robersons that they would be taking over the Elbow to renovate and operate it themselves, public statements were issued by both parties to address hurt feelings and conflicting viewpoints. But for Amanda Thompson, the Elbow Inn isn’t just a business that they happen to own. It represents family interaction in all its

ramifications—life events, celebrations, stints using the building as a residence. All those memories are woven through the old boards of the inn, creating a strong family desire to inhabit it themselves.

“My grandmother had her first baby shower there when she was pregnant with my Aunt Pam. My mother had her wedding reception there. My father… my sister’s been married there; we’ve had family wakes there. And many friends and family and community members have had really special events at the tavern,” Amanda explained. “The Elbow Inn is not just some motorcycle bar, it’s more than that. So, when people come to see it, we want to give them that experience that they’re coming to eat and have drinks at my house.”

But for all that, the question that is most asked on social media is about all the brassieres hung up in the Elbow Inn’s most recent iteration. “I get it. It was all in good fun,” Amanda commented. “One day, a woman from Germany traveling through stopped in with a bra and a note, and I’ve kept it, but that’s going to be the last one. I have it in a shadow box and it will be displayed with her note inside the tavern.”

Into the Future

In recent years, as the Thompson family has contended with the loss of older family members, the pandemic, their business tenants, the flood, and the resulting damage to their nearly-acentury-old inn, they’ve had a lot to think about. Amanda has emerged as a strong voice for the family and a generational leader, with matriarch Aunt Pamela right behind her.

Amanda and Pamela have given thought to making their new version of the Elbow Inn more approachable and more familyfriendly, while keeping the original look of it—maybe during great-grandpa Paul’s time—intact. Cognizant of it being one of the oldest bar and barbecue places still standing on Route 66, their intention is to preserve it to pass on to their children.

Other family members stepping up to contribute their talents are Pamela’s son Clark Thompson, a trained chef; Amanda’s younger sister and bartender Jayme Thompson Burns; and Amanda’s husband Brandt Miles, a writer who enjoys smoking and barbecuing meat. Amanda herself, although with a long career in health services, also very much enjoys cooking. However, they still must get past the hurdle of the long list of necessary renovations to be able to be open on a regular basis.

“From what I have seen, they have started from the ground up to restore it and secure it… the foundation, and all of that,” said Wiles. “I think that it’s been a tremendous undertaking for them, and they’ve had this ongoing renovation for a period of time. And then, of course, we had COVID with us all going through the restoration process.”

This spot of unmistakably Ozark scenic beauty holds a colorful and storied century full of history. The Thompson family’s painfully slow rebuilding process might just insure another hundred years for the old sandwich shop. There may be more raucous and risqué times with bikers and babes. Undoubtedly, there’ll be more family gatherings with sweet and sentimental memories. But one thing is for sure— there will be more family stories told, more precious visits recounted, and more glasses raised to good times on the bank of the Devils Elbow.

“ Taking off now. Have some stops to make!”

CLEAR YOUR SCHEDULE.

GET TO PULASKI COUNTY, MO!

Ready for a road trip of breathtaking twists and turns that will take you back in time? Experience 33 miles of Route 66 in Pulaski County! Traverse across Devils Elbow bridge, take in scenic vistas, and snap a photo in front of the mural located at the former Devils Elbow Cafe. en, fill up at an oh-so-tasty diner before heading off to uncover even more rare finds at countless unique stores and antique shops. Check out our Great American Road Trip Itinerary, book your stay, and get ready to play on a road you’ll always remember.

Plan your Mother Road adventure at visitpulaskicounty.org/roadtrip.

A REAL LEGACY

By Rich Ratay Photographs by Efren Lopez/Route66Images

LEGACY

ajestic buttes. Craggy red rock canyons. Sprawling desert vistas. For Hollywood directors anxious to cash in on moviegoers’ insatiable appetite for Westerns during the 1930s and 40s, the area surrounding Gallup, New Mexico, offered an ideal shooting location. The sleepy town lacked just one thing — lodging worthy of the biggest stars of the silver screen.

Enter R.E. “Griff” Griffith, brother of legendary film director D.W. Griffith. Sensing an opportunity, the savvy entrepreneur conceived a plan to provide Gallup with the crucial missing cast member it needed to attract major film productions.

In 1937, Griff’s showstopper made its stunning premiere. Situated along the increasingly famous Route 66, the impressive structure deftly combined the rugged character of a classic Western ranch house with the genteel grace of a Southern plantation. Out front, six sturdy columns supported a stately portico. A balcony over the entrance offered guests an airy spot to linger as they greeted new arrivals. And high on the roof above, lending an unmistakable flourish of Hollywood glitz, a neon sign blazed with the striking new landmark’s name: El Rancho Hotel.

Thanks in no small part to the influential connections of his famous sibling, Griff’s luxurious lodge was an instant sensation. Film productions flocked to the El Rancho, bringing with them a steady stream of box office legends: John Wayne, Kirk Douglas, Mae West, Katherine Hepburn, and many more.

In the process, the El Rancho Hotel became a star in its own right — one that still burns brightly alongside the shoulder of the venerable Mother Road.

Setting the Scene

Considering its humble roots, Gallup hardly seemed destined to one day claim the spotlight as Hollywood-East. The tiny hamlet was established as a makeshift administrative headquarters during construction of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad in the mid-19th century. Among the functionaries stationed at the outpost was a nondescript paymaster named David Gallup. Whenever railroad workers were scheduled to be paid, they’d notify their supervisors they were “going to Gallup.” The name stuck. As settlers built permanent homes and businesses around the railhead, the town officially incorporated as Gallup in 1881.

In 1926, the modest community gained greater prominence when Gallup was included as a waypoint along Route 66. From the time of its completion, the highway became a famous and favorite passage to America’s alluring West Coast.

“Gallup had long served as an important stop for travelers heading to California on the railroad,” notes Tammi Moe, Director of the town’s Octavia Fellin Public Library and of the historic Rex Museum (relics from the town’s history housed in a former brothel). “But Route 66 brought countless more tourists to town. It was a big boon for local businesses.”

MDespite its growth, Gallup retained the look and feel of an authentic Old West town. “Even then, the Indian people who lived nearby were still riding to town on horses and setting up camp to trade with merchants just as they had for decades,” notes Larry Fulbright, manager of the Richardson Trading Post, another legendary Gallup landmark.

The town’s rustic charm was matched only by the rugged beauty of the landscape that surrounded it. By the 1930s, the scene was set. All that remained was for someone to recognize Gallup’s enormous potential as a site for filming the thrilling Western shoot ‘em ups dominating the box office at the time. That someone would be R.E. Griffith.

“The Charm of Yesterday… The Convenience of Tomorrow”

Griff was already familiar with the area. Along with several other investors, he owned a large chain of movie theaters operating in small towns not unlike Gallup throughout the American Southwest.

But Griff realized Gallup offered one advantage other destinations couldn’t. In addition to the picturesque scenery that lay nearby, the town’s placement on both a major highway and a railroad made it readily accessible. That made Gallup especially attractive for movie production companies that needed to transport cumbersome lighting and camera equipment, along with dozens of crew members, to the sites of their shoots.

To assist with the plan for the hotel, Griff hired architect (and later hotelier) Joe Massaglia. Together, the pair decided on a rambling Western ranch-style layout. Cast members, directors, and other important guests would be accommodated in a threestory main building while crew members and lower-level staff would be housed in an attached bunkhouse.

Knowing how much celebrities relished making a grand entrance, Griff decided his lobby needed to welcome his famous guests in style. His design combined the rustic feel of a Northwoods hunting lodge with the theatrical flair of a Hollywood movie set.

Then as now, the hotel’s front doors open to a vast chamber with an exposed joist ceiling supported by two pillars like mighty oaks. Rising like a majestic mountain between the two columns is a mound of dark stone housing a spectacular ashlar walk-in fireplace. Ascending both sides of the massif are winding twin staircases fashioned from split logs clad in plush red carpet. They climb to a second-floor balcony that sweeps around the entire level. Brightly colored woven Navajo rugs drape down from a rough-hewn wooden balustrade while mounted deer heads gaze down from their perches on the massive oak columns. Scattered throughout the room, padded dark wood couches and chairs invite guests to settle in for lively conversations.

While famous actors could “chew the scenery” in their on-screen roles, they would also need actual food. To accommodate them, Griff included an onsite restaurant serving burgers and Southwestern fare. Of course, he also made sure to include an inviting bar area to provide exhausted guests a place to unwind after a long day on the set or on the road. Afterward, movie stars and motorists alike could retire to one of dozens of spacious and well-appointed guest rooms in the main building.

Finally, Griff knew the Hollywood crowd he aimed to attract would demand the finest service. To ensure his

employees measured up to expectations, Griff enlisted the Fred Harvey Company — a hospitality outfit often credited with “civilizing the Wild West” — to train all staff.

Griff’s goal was simple: he wanted the El Rancho Hotel to provide “The Charm of Yesterday…The Convenience of Tomorrow.” It became the slogan emblazoned across the portico over the hotel’s front entrance.

Hey Days and Hard Times

If Griff had any doubts Hollywood would take notice of his new venture, they were quickly put to rest. From the day the ribbon was cut on the El Rancho Hotel, movie productions stampeded to Gallup.

Over the next several decades, the El Rancho would serve as base camp for hundreds of films, among them 1940’s The Bad Man featuring Lionel Barrymore and Ronald Reagan, 1948’s Streets of Laredo starring William Holden, and 1950’s Rocky Mountain with Errol Flynn. The hotel’s guest register would read like a “Who’s Who” of silver screen legends: Humphrey Bogart, Burt Lancaster, Gregory Peck, Betty Grable, and Joan Crawford, to name a few.

Tales of the stars’ exploits while staying at the El Rancho abound. “The story that gets mentioned most is Errol Flynn riding his horse from the film set right into the bar,” said Michael Ellis, El Rancho’s General Manager. “I guess he must have been pretty thirsty.” It’s also believed that Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, who was married to another woman, insisted on being booked in adjacent rooms.

Of course, El Rancho’s guests included more than movie stars. The hotel’s prominent location along Route 66 also made it a popular stop for weary motorists. “We’re kind of out in the desert halfway between Albuquerque and Flagstaff, with both cities hours away,” said Ellis. “The location has always made it an ideal place to pull over for the night.”

For Griff and El Rancho, it likely seemed like the good times would never end.

However, as with many of the stars who once walked its halls, El Rancho’s luster would fade with time, despite the mid-century addition of an adjacent modern motel. Initially, the decline was gradual. By the 1960s, audiences were losing interest in traditional westerns. Once lofty production budgets dwindled. To lower costs, studios began to shoot many western-themed TV shows and movies on their own backlots, or even in Italy (earning such films the colorful tag “spaghetti westerns”). Soon, large film crews and big-name stars were no longer blazing a trail to Gallup.

Worse still, the completion of I-40, as part of America’s Interstate Highway System, offered California-bound motorists a faster alternative to Route 66. The once steady stream of cars passing through Gallup slowed to a trickle. Even fewer pulled over to park beneath the glowing neon sign of El Rancho.

As it became harder and harder to pay the bills, the hotel changed ownership several times. In time, the property fell badly into disrepair. When the hotel eventually fell into bankruptcy in the 1980s, plans were made for its demolition. The once celebrated El Rancho appeared headed for its last roundup.

The Hero Comes Riding In

Every great western needs a hero. El Rancho’s would come in the form of Armand Ortega Sr. Like in the movies, Ortega arrived just in the nick of time to save the hotel.

As a boy, Ortega had visited the El Rancho several times with his parents in the 1940s, despite the hardworking family having to scrimp for months to afford each fancy restaurant meal. On one such special occasion, the ambitious young Ortega pledged he would one day purchase the hotel for his mother. He spent the next 50 years growing the family’s Indian trading business — passed down to him for five generations — into one of the most successful in the region. The family also operated concessions businesses at a halfdozen national parks. Finally, in 1986, Ortega made good on his promise.

“The crane with the wrecking ball was literally in the parking lot,” recalled Shane Ortega, Armand’s grandson. “He told my grandmother he was just going to buy some furniture at the bankruptcy auction. Instead, he bought the whole hotel.”

Ortega purchased the property for $500,000. He spent at least the same amount restoring El Rancho to its former glory. Beyond the money, Ortega invested his heart and soul in the project. He refurbished guest rooms. He added an Indian jewelry store. Most of all, he worked diligently to resurrect the splendor of the hotel’s famous lobby.

“He wanted it to look as close as possible to how he remembered,” said Shane. “To recreate the furnishings, he sketched them out by hand on napkins. Then he’d go out and find the right craftsmen to create them.”

Just two years after Ortega purchased the property in 1988, El Rancho reopened. The first eager guests to set foot inside the lobby were astonished by the thoroughness of Ortega’s renovation efforts. Not long after, the hotel was accepted for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Over the next several decades, El Rancho would go on to reclaim its standing as one of the most uniquely enchanting accommodations in the American Southwest.

A New Generation for El Rancho

After enthusiastically welcoming guests and watching over El Rancho for nearly 30 years, Armand Ortega Sr. passed away at age 81 in 2014. For several years, the property was managed by his children. Then in 2018, Shane Ortega bought out his aunts and uncles to become the property’s sole owner.

Like his grandfather, Shane came to acquire El Rancho through hard work — he’d founded and run a successful concessions company operating in several national parks. Also like his Grandpa Armand, Shane is passionately devoted to El Rancho — and the famous road it rests beside.

“For me, Route 66 is like America’s unofficial national park,” explains Shane. “And El Rancho is like Old Faithful— a main attraction.”

To ensure the hotel remains a favorite stop for Route 66 enthusiasts, Shane and his management team recently launched a multi-million dollar renovation project. One initial focus will be updating the 23 guest rooms of the 1960s-era adjacent motel which Shane also acquired in the transaction.

“I want the motel to offer a different experience than the original hotel,” explains Shane. “I want it to be fun and retro, a bit kitschy, like Route 66 itself.”

Back at the hotel, the restaurant will be relocated to its original home in the Andalusian Room, complete with a meticulously recreated, historically accurate backbar. Outdoor dining will also be added. Finally, the plan calls for updating the original guest rooms with décor and amenities in line with the expectations of a new generation of travelers.

In other words, Shane’s goal is to deliver more of “The Charm of Yesterday…the Convenience of Tomorrow.”

Somewhere, R.E. Griffith is nodding in approval.

Where Legends Live On

Today, walking through the main entrance of El Rancho Hotel is like stepping into a time portal. Thanks to the determined efforts of Armand and Shane Ortega, R.E. Griffith’s spectacular lobby appears much the same today as it did upon its debut 85 years ago.

Countless more treasures lie waiting to be discovered within. Nearly everywhere throughout the hotel, the Ortegas have thoughtfully placed and preserved enchanting reminders of the hotel’s glamorous past. On the walls of the lobby’s upper level, you can browse framed autographed photos of the countless celebrities who once strolled the very same hallways — Gene Autry, Robert Mitchum, Doris Day, Rosalind Russell, even the Marx Brothers. Retrace their footsteps to the hotel’s restaurant and you can order dishes prepared exactly the way the celebrities for whom they are named ordered them long ago.

“W.C. Fields really did like Green Chile on his Cheeseburger,” explains General Manager Michael Ellis. “And the Ronald Reagan Burger comes with applewood smoked bacon and a side of jellybeans, just like it was served to him back then.”

After your meal, you can mosey down to the 49er Lounge for a nightcap. There you can sip an ice-cold Mexican beer or hand-squeezed margarita while occupying a spot along the bar where Tom Mix or Roy Rogers likely once sat.

For many guests, however, the highlight of their visit is the chance to stay in the same room as a famous star.

“I absolutely love that the rooms are named for the celebrities who really stayed in them,” said Amy Bizzarri, author of the travel guide The Best Hits on Route 66. “My personal tradition is to stream a movie that starred the actor or actress of the room I’m staying in that evening. During our last visit, my kids and I stayed in the Susan Hayward room and we watched her in the 1946 movie Canyon Passage

Considering El Rancho’s storied past, Shane Ortega knows he has a responsibility to provide guests with much more than a clean room and a hot shower.

“I’m a big believer in the power of moments,” Shane confessed. “From the time they walk into the lobby to the restaurant where they eat to the room they stay in, I want every guest to have five or six ‘Oh, wow’ moments they’ll always remember.”

Rest assured, El Rancho Hotel remains as unforgettable as the stars whose legends it celebrates.

Culture you can step into.

Storyteller Museum

Monday - Friday Gallup Cultural Center

Summer Indigenous Arts: Dances

Monday, Wednesday, Friday May - August Gallup Cultural Center

Summer Indigenous Arts: Demonstrations

Fridays, May - August Gallup Cultural Center

A RELIC WITH

WITH A STORY

Photograph by Efren Lopez/Route66Images

Photograph by Efren Lopez/Route66Images

Amid the dust and sand of the High Plains landscape, about 42 miles east of Tucumcari, New Mexico, and 73 miles west of Amarillo, Texas, and not far from the fast-moving lanes of the I-40, stand the crumbling remains of maybe a dozen buildings the fading evidence of the roadside businesses that once graced the little town of Glenrio. Barely more than a village at its largest, yet originally platted for 3,000 people, the town was once an important wayside stop with a cluster of establishments that served travelers on Highway 66. Today, these abandoned remnants seldom merit as much as a nod from interstate travelers flying by, but they remain a prized stop for those who value its unique history.

While Glenrio literally means “valley river,” from the Scottish word “glen” for valley and the Spanish word “rio” for river, the town is neither in a valley nor near a river. It sits perched on the border between Texas and New Mexico with over 30 miles of desert in either direction to the nearest municipality. Looks can be deceiving, because Glenrio sits at about 3,850 feet elevation. In a good year, it will receive about 15 inches of moisture. Summertime temperatures often hit 110 degrees.

Established in 1903 as a railroad stop on the Rock Island Railroad, the fledgling settlement was supported by cattle and later grain shipments. By the 1920s, the community along the railroad had flourished to support several businesses, including grocery stores, a hardware store, a land office, some service stations, a hotel, a restaurant , and a post office on the New Mexico side. Texans had to walk across the border to get their mail, setting precedent for other border crossings.

When the existing dirt Ozark Trail highway system was incorporated as Route 66 in 1926, to the north of the railroad, a new commercial strip developed along the new highway. The businesses that had existed along the railroad either shut down or moved closer to Route 66 to capitalize on the increasing traffic. Route 66 sparked new trade activities, and by the 1930s, Glenrio boasted a slew of new businesses. On the New Mexico side, John Wesley Ferguson built the State Line Bar, the State Line Motel, and a gas station which became Broyles Mobil Gas Station run by Jim Broyles.

On the Texas side, Homer Ehresman, another local businessman, opened the Longhorn Cafe and Gas station in 1953, and the “U” shaped Texas Longhorn Motel in 1955, with a metal sign announcing “Motel First Motel in Texas Cafe” facing east and “Motel Last Motel in Texas Cafe” facing west. Another Glenrio local, Joseph (Joe) Brownlee, also took advantage of the new highway by opening a Texaco gas station down the street in 1950. He later added the Art Moderne-style Brownlee Diner in 1952

Being split between two states made for a unique way of life for its residents. Back in the day, inhabitants of the town could only purchase alcohol on the New Mexico side, since the Texas side was in a dry county, and they bought gas on the Texas side, because of the high gas tax in New Mexico.

Glenrio’s prosperity continued to grow throughout the mid-century, with families traveling cross-country after

World War II. The story goes that the road traffic was so high that there was a line up for gas on any given day. Day and night, people from across the country passed through to fill up on gas, eat a meal at the Brownlee Diner, or spend the night at the State Line Motel.

However, the glory days of Glenrio were not to last. The first blow was when the Rock Island Depot closed in 1955 due to the decline in rail passengers. This was then followed by the opening of Interstate 40 in 1975, allowing tourists to make faster time by bypassing Glenrio completely. It was like flipping a switch, the same switch that was flipped in many small Route 66 towns across the U.S. Suddenly the people were gone.

“Nowadays more dogs than people live there,” said respected Route 66 author and historian, Michael Wallis. “The town has evolved into an oasis for tumbleweeds and roadrunners on the prowl for reptile suppers.”

Besides critters, the town is said to have only one resident, yet most of its buildings, including the Brownlee Diner and the shell of the Texas Longhorn Motel and Cafe still stand. The remains of these businesses and the rest of Glenrio provided inspiration to the Pixar people in writing and producing the Cars movie. Glenrio’s historic district was placed on the National Register for Historic Places in 2007, but so far that hasn’t halted the decay of the original structures from the town’s golden days.

“To me,” said Wallis, “these [ghost towns] are as important as the many Route 66 towns that are still perking and serving up hospitality to generations of new travelers from literally around the world. There’s always the rogue treasure: stained menus, yellowed gas receipts blowing through the weeds, broken coffee mugs, bottle caps, dead spark plugs hiding in the dust. In the past, I found a trucker’s daily logbook, ceramic shards of bygone times, and newspapers as old as I am.”

Although Glenrio was more or less put to rest after the construction of Interstate 40, there was talk in the spring of 2022 about bringing the town to life again in the near future. Developers Glenrio Properties announced plans to revive the town, but after removing the motel’s roof and part of the venue itself, as well as erecting a chain-link fence, the plans seemed, as of the fall of 2022, to have stalled. No updates have been provided by the development company. Now a stop along this lonely stretch of Route 66 seems a little sadder. But many people are hopeful for the new face of Glenrio. Meanwhile, other structures continue to decay and fall to the earth.

“I am passionate about historic preservation, and also support and advocate the resurrection and repurposing of historic sites. That includes forgotten and neglected places. Glenrio is a good example of such a place and deserves another chance,” noted Wallis.

It’s impossible to know what the future of ghost towns like Glenrio will look like, but two things are certain: they are disappearing quickly nowadays, replaced by new dreams of modern developments that may or may not fit the mood of the road, and two, a trip down the Mother Road will be a little less memorable without them.

GATEWAY

Photograph by David J. Schwartz - Pics On Route 66

Photograph by David J. Schwartz - Pics On Route 66

GATEWAY TO 66

Countless cities across the continental United States have honored welcome signs. The signs serve to greet visitors and welcome home locals, whether it’s the scintillating neon sign of Las Vegas, Nevada, or the understated Brooklyn marker that lets you know “Where New York Begins.” The Gateway Sign in Miami, Oklahoma, a town that refers to itself as the “Gateway to Route 66,” was the city’s passion project that has attracted Route 66 travelers and inspired the town to work on projects of a similar nature.

Miami, Oklahoma (pronounced My-Am-Uh), was originally a Native American Territory before it became a booming town and home to wealthy lead and zinc miners in the 1900s, around the same time the original sign was erected. The sign was initially situated outside the town’s railroad station and embraced those who got off in Miami.

“It was located over on Central Street, and it was near the railroad station,” said Amanda Davis, Executive Director of Visit Miami. “So, as people were coming in and out of Miami, the sign was really put up as a welcome to folks as they came in. Then obviously over time, it went away.”

During the 1930s, the sign was taken down supposedly due to its condition, and almost became lost to time. Decades later, a local group decided to revive it. The project for the replica of the Gateway Sign began when Miami was awarded a National Scenic Byway grant for the historical properties of the sign, which was relocated to Main Street, one of the longest Main Streets along Route 66. The team was composed of Visit Miami, the City of Miami, and the town’s Main Street Program, and they dedicated themselves to replicating the once-standing Gateway marker.

“I remember sitting in meetings for months, even talking just about the fonts,” Davis recalled of the time spent planning the replica. “To make sure that when it lit up at night, visitors would be able to see it. We wanted to make sure that they were taking pictures and that you could tell in the picture that it was Miami, Oklahoma. We knew we had to get it right the first time.” With the “Engravers Bold Face” being the font chosen for the replica, the tireless efforts of the team were brought to fruition during the ribbon cutting

of the Gateway Sign in 2012. The welcoming sign stands over 10 feet tall and spans two lanes of traffic. However, while Davis and the rest of the team celebrated their accomplishment, not everyone in town thought that it was a good investment or money well spent.

“When the Gateway Sign first went up, we got some negative feedback,” said Davis. “People just did not understand why in the world, we would spend that money on a sign when we could have put it into a park, or we could have built a new street or done something different with infrastructure for the city. It took us a little bit to educate people to understand.”

However, now there is no doubt that the community benefits from the sign’s replication and status as a historical marker. Unbeknownst to anyone at the time, the Gateway Sign ended up becoming a catalyst for creating other historical markers in town and revitalizing downtown Miami. The projects the town is now working on include getting a milepost marker for the Ozark Trail and signage to point people off Route 66 to their historical Coleman Theatre. The sign also brought more traffic to downtown, leading to the opening of new business and increased economic prosperity in the community.

“It continues to spur economic growth,” reflected Davis. “We’ve got a café right down there that has been closed for probably a decade. And recently, somebody bought it and is going to reopen it up as a café [again].” While none of this was the initial purpose of the sign, the community gladly reaps the benefits of the replication of their iconic attraction.

The original Gateway Sign was created to greet newcomers to Miami over a century ago, and its replica honors that purpose to this day. The once lost landmark reflects the uniqueness of this stretch of the Mother Road and pays tribute to the work of those who replicated its special attraction. Generating business and traffic in the once bustling mining town, the sign lives up to the legacy left by the original. Route 66 is famous for making visitors feel welcome, but perhaps Miami, Oklahoma, just set the stage, way back at the turn of the century.

A CONVERSATION WITH

Linda Ronstadt

By Brennen Matthews Photographs by Jason Henry

Music is filled with legends, talented individuals who created a name for themselves for a variety of reasons. But few, the truly gifted ones, are remembered for their music and for the influence that their songs have had on our lives and the wider culture of the times. The heady 1960s was undeniably a season of change, a period of musical birth and divine creativity. And onto this classic stage stepped an unassuming, wide-eyed young woman from Tucson, Arizona, who would go on to impact music for the next five decades and influence some of the biggest bands and singers on the planet.

Linda Ronstadt, born on July 15, 1946, was raised in a home that was bathed in music. Her father, Gilbert, had a deep baritone voice and played the piano and guitar, while her mother, Ruth May, sang and played the ukulele. With time, Linda and two of her siblings, Peter and Suzy, formed their own music group, called The New Union Ramblers — a play on the bank where Suzy worked, and the word “ramblers,” which Linda thought sounded sufficiently folky. Soon the siblings were joined on guitar by high school friend Bobby Kimmel. The trio worked hard, perfecting their musical skills, but soon, as they grew older, almost inevitably, the band broke up, as childhood dreams gave way to new ones. Peter joined the local police department — where he would one day become Chief — and Suzy’s time was taken over raising an ever-growing family. As such, Linda was left to perform on her own at local clubs. Shortly after, Bobby left too, heading west to the siren call of Los Angeles to pursue his musical dreams, and Linda decided to enroll for the Spring semester at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

In 1965, ready for a short change of scenery, Linda packed up the car and headed with some friends to sunny California for Spring Break. She planned to visit with Bobby and then head back for classes in the fall. But fate has a way of unraveling our plans. Sleeping on Bobby’s floor, or anywhere the group could fit, the old friends (along with others) visited local clubs and venues to listen to upcoming musicians and popular music. Bobby was eager to introduce her to a guitarist that he had met named Kenny Edwards. She was impressed at once with his guitar playing and struck by the energy and scene in Southern California. One evening, some of the guys began talking about a new band called The Byrds that was creating a new sound — folk rock. Eventually, the friends went to see the band at the Trip, a new club down on the Sunset Strip that was popular for its light show that supposedly added a psychedelic experience to the performances. That night, The Byrds were amazing, their sound and style demonstrating that something truly fresh was afoot in the music being created in Southern California. For a young Linda Ronstadt, she had seen enough. Once back in Arizona, she began to make plans to permanently head west, and music and musical history would never be the same.

Around what age did it click with you that you might want to pursue a career in music?

I never wanted to be anything but a singer. I thought that I would be singing at pizza parlors or Holiday Inns, or something like that. As long as I could make a living as a singer… I didn’t have an ambition when I started.

What did your mom and dad think when you made that decision that you’re going to pursue music in California?

Well, they thought I was too young to leave home. And I was, I was only 18. But I had to get to where the music was. And it was not in Tucson. It was in LA. When it became apparent that they couldn’t change my mind, my father went into the other room and returned with the Martin guitar that his father had bought brand new in 1898. My father handed me the guitar and took out his wallet and gave me thirty dollars. I made it last a month. The only thing I remember about that long ride through the desert night was the searing remorse for having defied my parents.

When you moved to Los Angeles, counterculture was taking hold of the country, with California perhaps being the epicenter. What was it like for you at such a young age, during such a fascinating period, when you first arrived?

Well, it was all very new. It was a new world. There were a lot of art films that we went to see. We went to hear a lot of other music groups. We were kind of brown hippies. Country hippies. We got to tour that world a little bit. There was a lot of stuff, there were psychedelics and a lot of new things to embrace. I fell in love with Japanese movies.

The first time I was there, we were gonna go see this band called the Rising Sons at the Ash Grove. The Ash Grove was where all the good folk music was, and I was just dying to go because I had heard about it. Read about it. And we went down to the Ash Grove and there was Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder playing in a band together. And I just said, “Man, they’ve got some great guitar players here!” I felt humbled by it and wanted to be around it and learn it.

You, Bobby, and Kenny formed your own band, the Stone Poneys.

Yeah, after a Charlie Patton blues song. We got gigs in little beatnik dives like the Insomniac. We got paid $30 or something like that. That is where I first met Jennifer Warnes. She was singing down there, too. Our school friends from Tucson would come stay for a few days on their way to their summer jobs, sleep on whatever bit of floor space they could claim, and we would sing our new stuff for them. The Troubadour had an open-mike night on Mondays, called Hoot Night, which also served as a way to audition. It was well attended by record company executives, managers, and agents. We were hired to open for Odetta, one of my folk music heroes. We were politely received by Odetta’s audience. It was our first time to perform in such a high-profile place.

The Stone Poneys quickly had a big hit with Different Drum , but the executives at Capitol Records had wanted you to record it slightly differently than you had initially envisioned it?

I had first heard it as a bluegrass song on a Greenbriar Boys album and just thought that it was a hit song. So, we recorded it, but it wasn’t the song that it could be. So, the record company said that they wanted to recut it. They recut it with the strings and harpsichord, and I was fairly horrified. I went, “We can’t do this!” But it was a hit. I was wrong.

Well, we were driving, and stopped for fuel at a gas station, and I heard it coming out of the back of the garage. It was on KHJ, which was a big Top 40 station in Los Angeles. I knew that if KHJ played it, it would go national.

We were on our way to the record company to talk about our second album and on the way the car froze. The engine froze. I mean, screaming metal. It was louder than an animal dying. It was horrible. We were stopped at the gas station, and we were trying to think what to do, because we didn’t have a car. And being car-less, as you know, in Los Angeles, is tantamount to death. And we had a big bass and our instruments in the car. So, we had to get somebody to come and get us. We were car-less, but we had a hit record.

You were playing mainly small clubs at that point?

We were playing at the Troubadour. That was big for us. It was wonderful to us. We played several clubs, there was a whole network of them. Golden Bear in Huntington Beach… there was a club in Santa Barbara. In those days, you could work at a real small level and still make money. You didn’t have to be famous to work there.

That must have been quite an exciting time when you look back, to be so young and your career is on the rise, and you’re in a place where so much is happening. What was it like being young and watching your star rise during that time in Southern California?

Well, I didn’t know that my star was rising that much. But when I hopped on at the Troubadour, I thought that was really something. And I played at the Whisky a Go Go. I prayed every night that the place would burn down, so I wouldn’t have to play there. And [then] it burned down three days after I closed. I thought, ‘Oh no, I must have wished it to burn.’

What was it about the Whisky that you didn’t like? Were you nervous to perform there?

It was just a different audience from the Troubadour, a little bit more dated. I didn’t like the band I was playing with.

Capitol Records wanted you to step away from the Stone Poneys and have a solo career. Was it a difficult choice to leave the band behind?