June/July 2024

June/July 2024

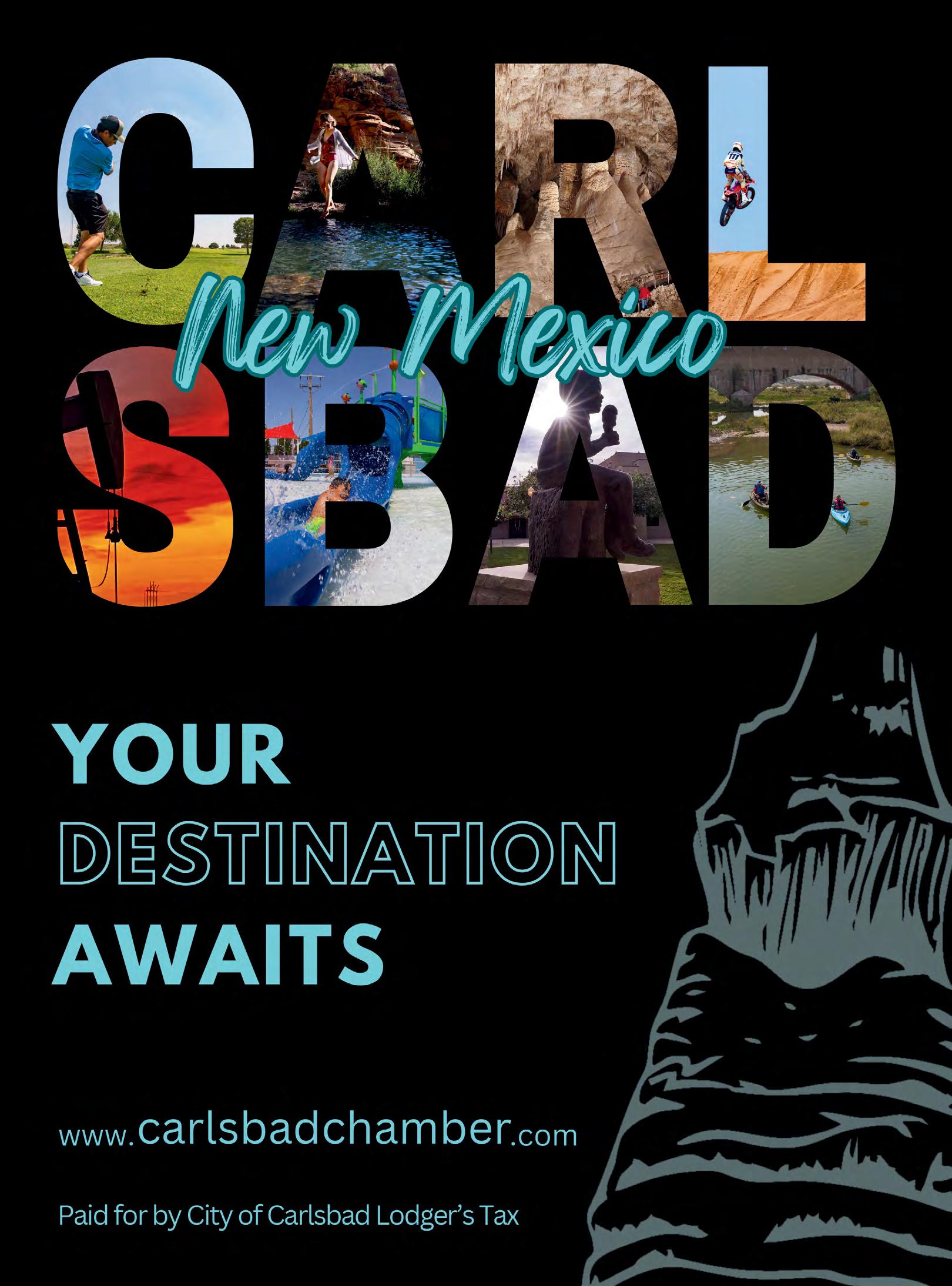

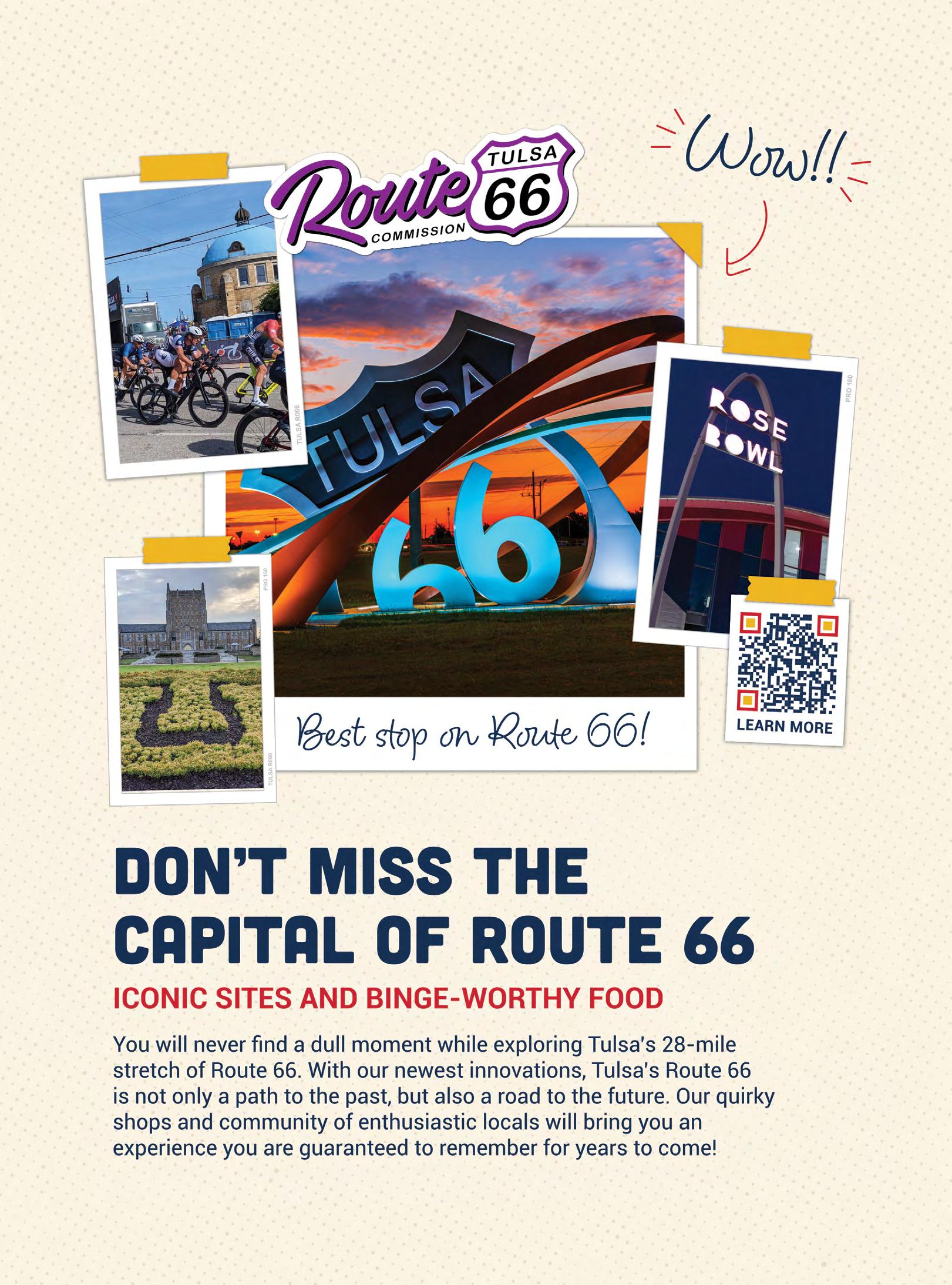

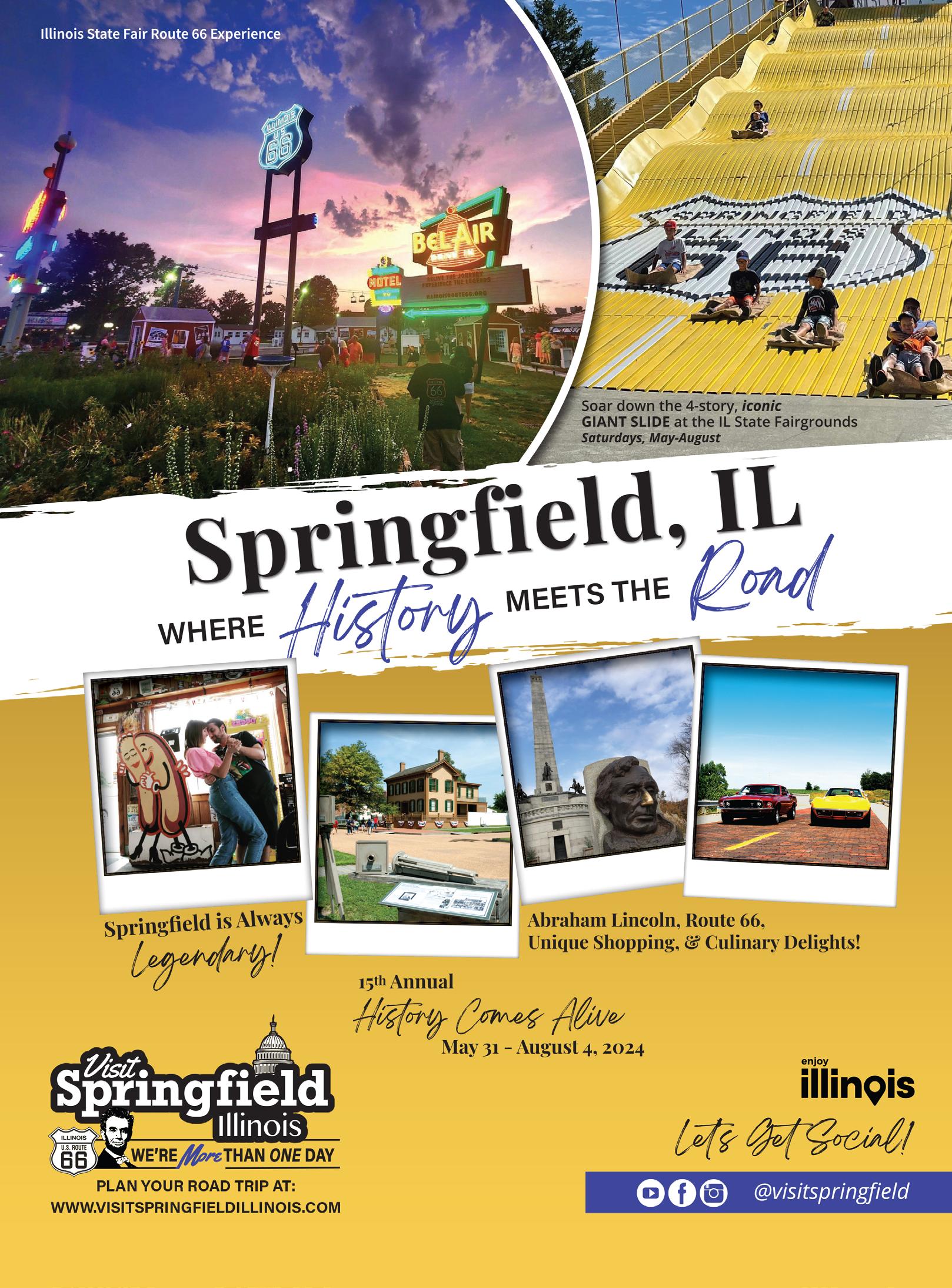

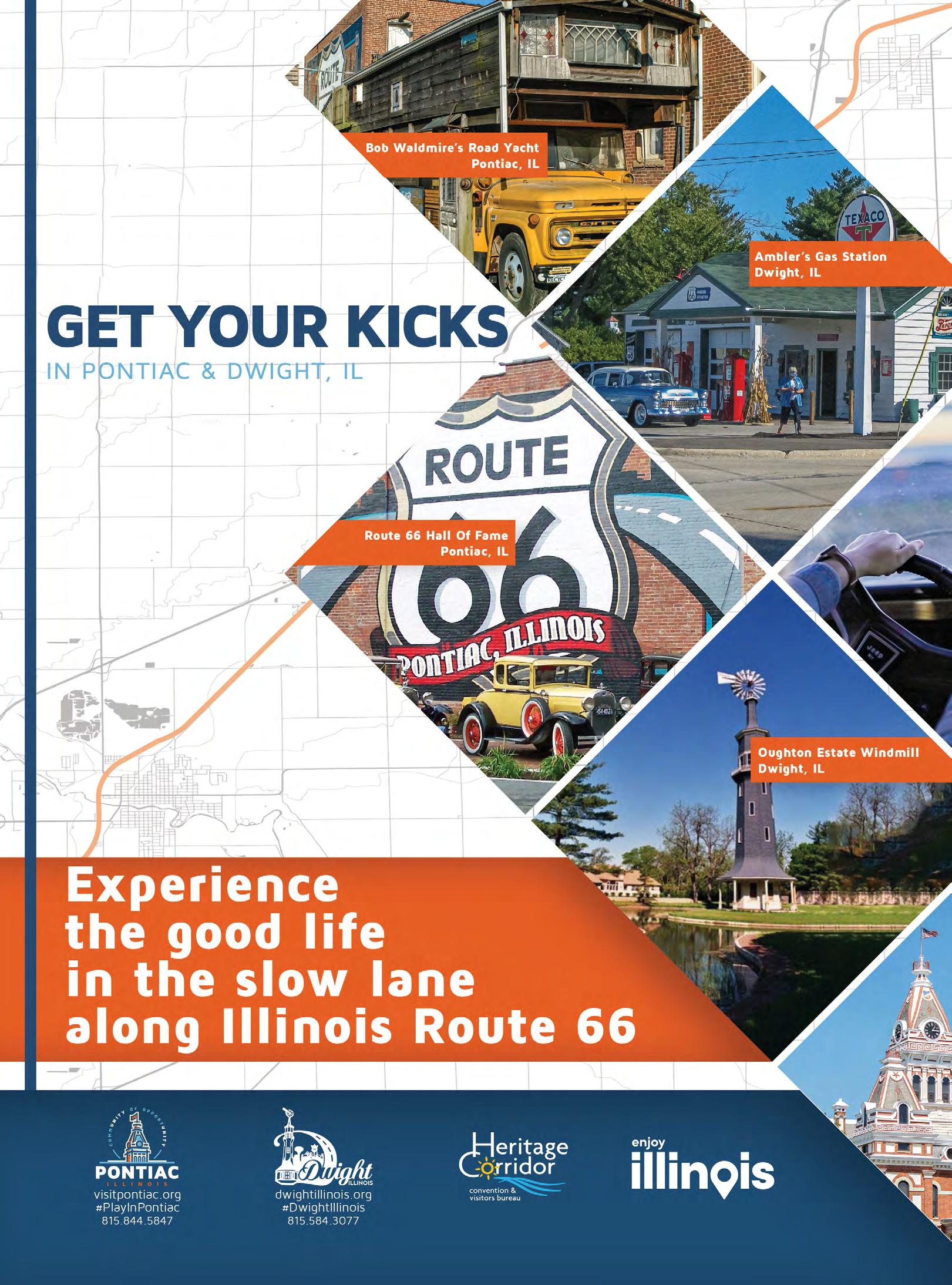

Whether it’s classic cars, old fashioned burgers or a museum that brings history to life, you can relive the glory days of Route 66 in its birthplace. We love our city and know the best places to eat, drink and play.

SEE YOU IN SPRINGFIELD,

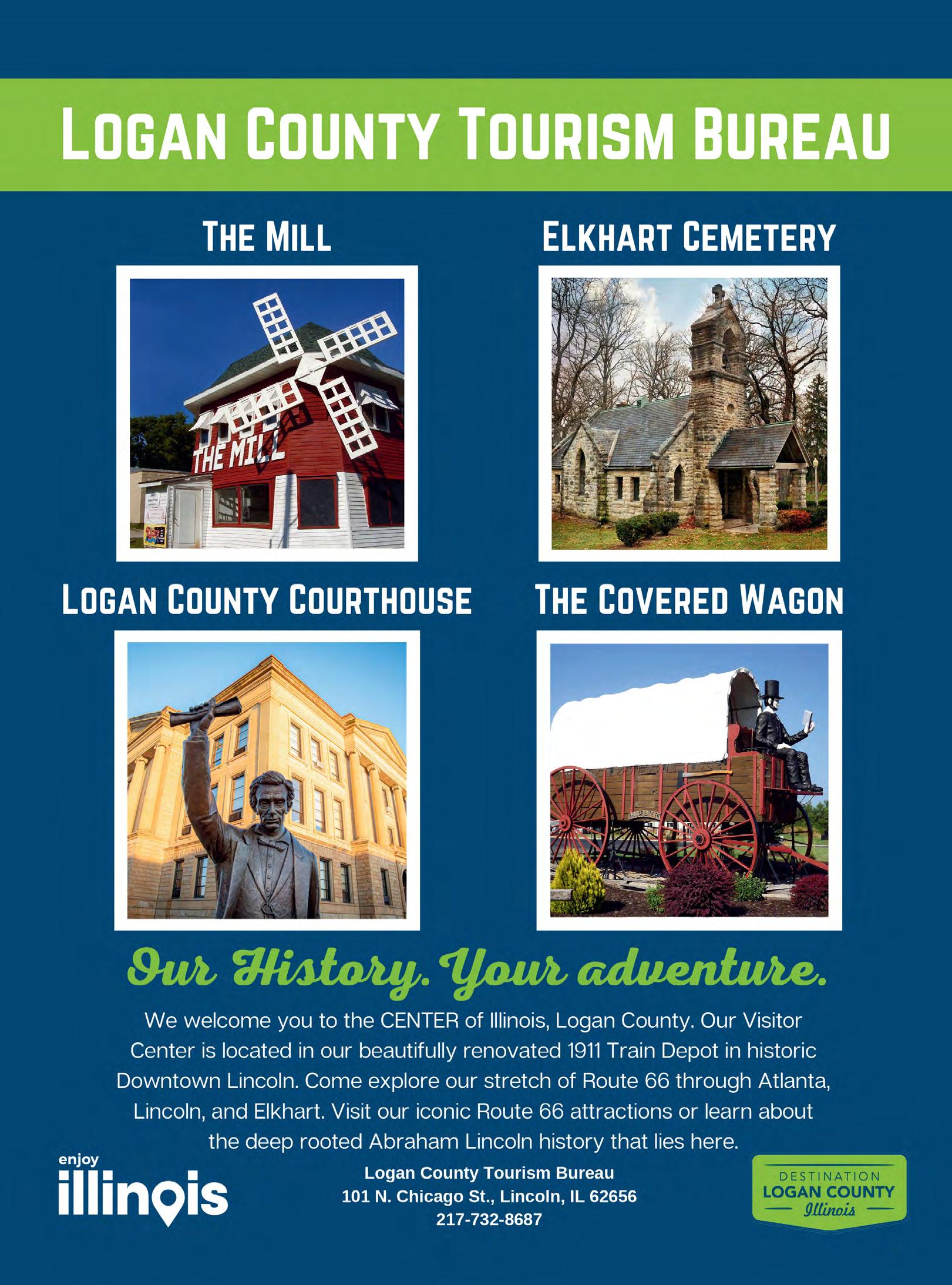

On Museum Square in Downtown Bloomington, the Cruisin’ with Lincoln on 66 Visitors Center is located on the ground floor of the nationally accredited McLean County Museum of History.

The Visitors Center is a Route 66 gateway. Discover Route 66 history through an interpretive exhibit, and shop for unique local gift items, maps, and publications. A travel kiosk allows visitors to explore all the things to see and do in the area as well as plan their next stop on Route 66. CRUISIN’ WITH LINCOLN ON 66 VISITORS CENTER

Open Monday–Saturday 9 a.m.–5 p.m. Free Admission on Tuesdays until 8 p.m. 200 N. Main Street, Bloomington, IL 61701 309.827.0428 / CruisinwithLincolnon66.org

*10% o gift purchases

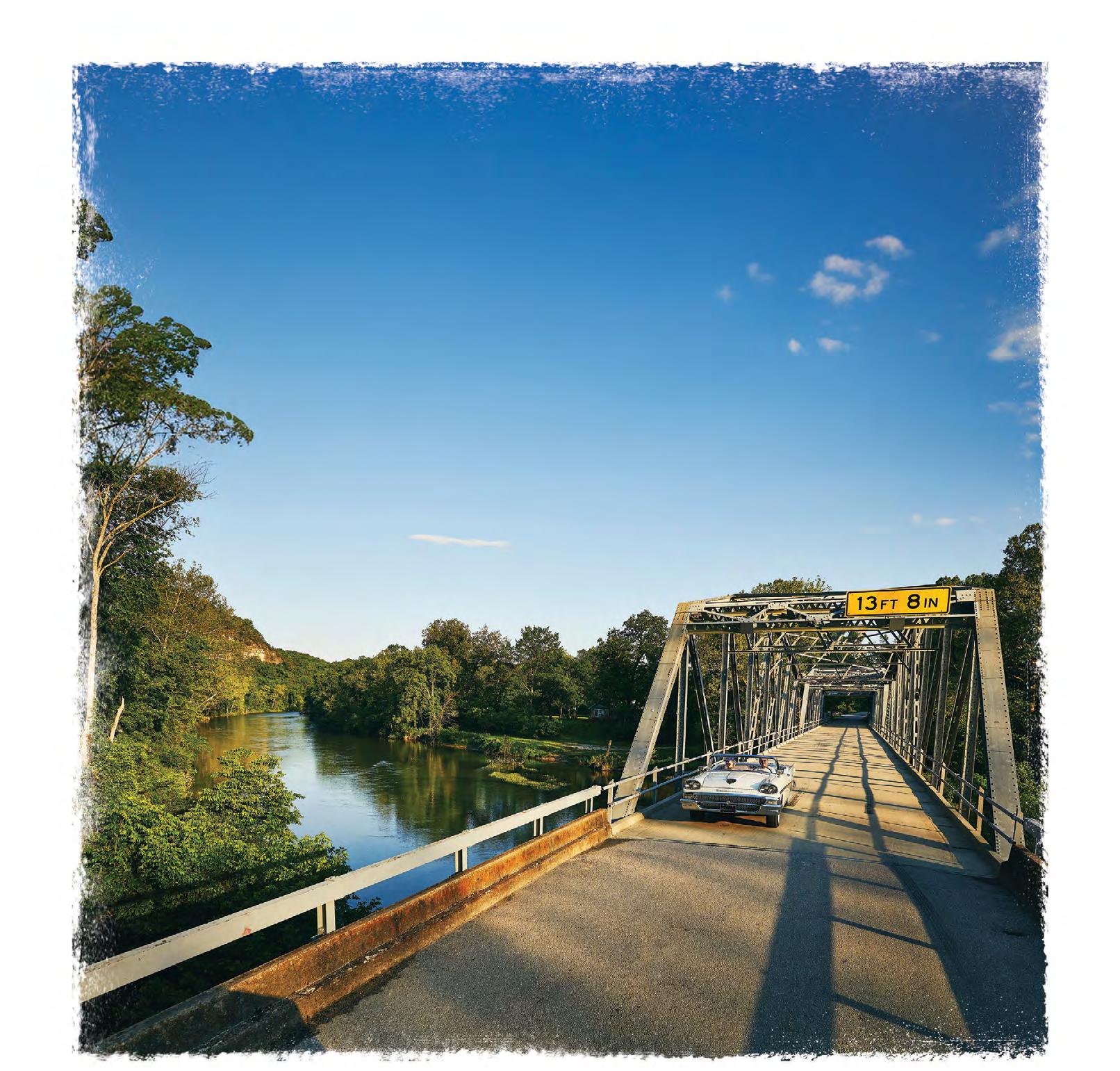

Remains of Cadiz Summit, East of Amboy, California. Photograph by Billy Brewer.

Vinita, Oklahoma, is home to a little café that has a big story. With a history that goes back to the 1960s, this humble but colorful eatery has a Mother Road tale that is packed with hopes, dreams, diversity, two giant guardians, and more than a pinch of ingenuity. This is an American story.

There are many places along Route 66 that collect and celebrate America of yesteryear. But some do it a little more unique than others. This is one of those stories. A story that began around 1930 with a filling station that fueled motorists for almost three decades. It then transformed into a beloved roadside attraction featuring a talkative, friendly truck driver. Today, under second generation owners, it stands as an iconic Mother Road stop where the legacy of America’s most famous highway is whimsically celebrated.

She is one of the music industry’s most respected female singersongwriters, and a performer who leaves it all out on the stage. With her husky voice and soulful blend of rock, folk, and blues, Melissa Etheridge has captivated audiences around the world since the 1980s, and she is nowhere close to slowing down. In this conversation, she takes us into her journey, both challenging and rewarding, that has brought her to where she is today.

If there is one town that evokes the spirit of the Mother Road, it would have to be Seligman, Arizona. And if there was one place in Seligman that truly captures the essence of Route 66, it would have to be the Snow Cap. This eatery is as famous for its tasty food as it is for its wacky antics, outlandish decorations, and for the endless gags played on patrons. Find out how it all began.

America is famous for its roadside attractions. It is the land of the unexpected, the bizarre. This is one of the nation’s biggest tourism draws. And down in southern Illinois, is a destination that has more questions that it does answers. Known as Cahokia Mounds, this once thriving settlement dating back to about 700 A.D., simply vanished. What happened and where did they go?

La Posada Hotel, Winslow, Arizona. Photograph by Efren Lopez/ Route66Images.

There is a commercial that I cannot get out of my head. Don’t you hate that? The main chorus says, “Summertime is here again… da da da da dum dum dum da da dum…” Okay, not very helpful, I know, but man is it stuck in my brain. Regardless, the message is right. Summertime is truly here again. It is June, and the leaves on the trees are green and abundant, and the birds are back in full force. I’ve always loved waking up to their song. Me, personally, I am thrilled with the start of the days of endless sunshine and optimism. I was born for summer.

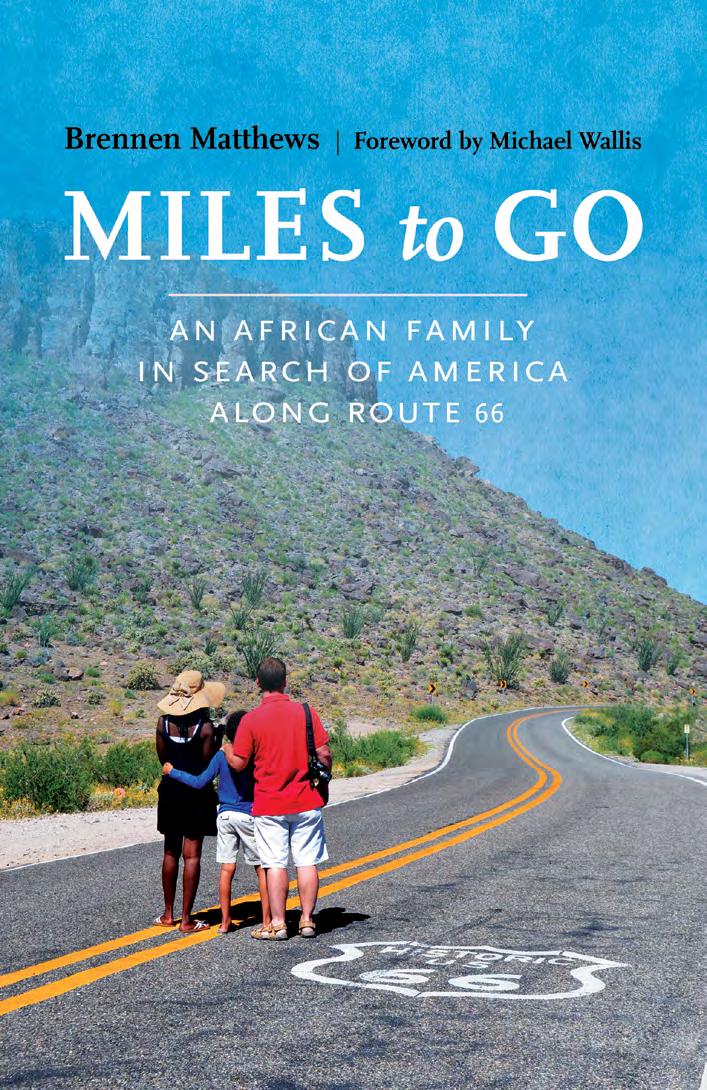

Every year when my son closes school, my family and I hit the road, and investigate our beloved Route 66 and a host of other fascinating destinations. This year, we will be spending eight weeks on the historic highway, heading west to the ever-blue Pacific Ocean, and then venturing up the sunny California coast, before turning back east through Death Valley, into Nevada as we trace the country’s “Loneliest Highway” for another few weeks. After that, we have Utah on the horizon, and then back on the Mother Road to Chicago. It is a big trip, but it will be wonderful to be back with many familiar faces and places, and to encounter some brand-new discoveries and excursions. America is, without a doubt, the most diverse, beautiful country on the planet – and we plan to spend our summer soaking up as much of it as possible. I hope that you all get to do so as well.

Every year we seek to create an issue — June/July: The Big Summer Issue — that will do justice to the season. We aim to bring you stories, imagery, and celebrity interviews that will entertain, inform, and whet your appetite to get out and explore. This year is no exception.

In this issue, we take you on a journey into the history and people behind several of the most beloved destinations on Route 66. The Snow Cap Drive-In in Seligman, Arizona, has long been one of the most popular stops along the highway, but other than the Delgadillo family’s love of hospitality and great food, what do you know about the origins of this quirky establishment and the journey that it has taken over the decades? We promise you, after you finish reading this article, you will be even keener to pay them a visit.

Down in Missouri, just west of Springfield, Gary Turner built his love letter to the Mother Road, and it is as endearing today as ever. Now manned by his daughter Barb and her partner, George, Gary’s Gay Parita is a car stopper. I remember the first time that I traveled that route and the unusual — and unexpected — attraction came into view, we were immediately taken aback. We had to pull over! We wandered around, impressed with the huge collection of vintage signs and midcentury advertising when a gravely voice interrupted our reverie: “Where ya’ll from?” This is a story that just keeps getting better as the years roll by.

Down in Oklahoma live two giants. They are of the friendly and welcoming sort, and they too have a story. And the vintage café that they stand guard over has had a journey that makes for some entertaining reading. This year when you venture down America’s most famous highway, make a point of stopping in Vinita and grabbing a bite at the Hi-Way Cafe. But first, consume this story and prepare yourself for the carnival that is awaiting you along this fine stretch of the historic road.

These, and so much more, make up this year’s summer issue.

I hope that we will see you out on the road this season. It is always such a joy to meet fellow travelers and get an opportunity to celebrate classic Americana with our amazing readers.

Oh, in case you were wondering, that jingle is still rolling around in my head!

Stay well and travel safely.

Blessings,

Brennen Matthews EditorPUBLISHER

Thin Tread Media

EDITOR

Brennen Matthews

DEPUTY EDITOR

Kate Wambui

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Nick Gerlich

LEAD EDITORIAL

PHOTOGRAPHER

David J. Schwartz

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Tom Heffron

DIGITAL

Matheus Alves

ILLUSTRATOR

Jennifer Mallon

EDITORIAL INTERN

Chloe Cassidy

CONTRIBUTORS AND PHOTOGRAPHERS

Aaron Garza

Billy Brewer Brotherdale

Chandler O’Leary

Cheryl Eichar Jett

Dick Lyon

Efren Lopez

Jim Luning

Joseph L. Roberts

Kate Matthews

Lauren Dukoff

Mitchell Brown

Paul Richard

Sarah L. Boyd

Editorial submissions should be sent to brennen@routemagazine.us.

To subscribe or purchase available back issues visit us at www.routemagazine.us.

Advertising inquiries should be sent to advertising@routemagazine.us.

ROUTE is published six times per year by Thin Tread Media. No part of this publication may be copied or reprinted without the written consent of the Publisher. The views expressed by the contributors are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, or service contractors. Every effort has been made to maintain the accuracy of the information presented in this publication. No responsibility is assumed for errors, changes or omissions. The Publisher does not take any responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts or photography.

Ancross a windswept, desolate desert landscape, roughly 500 feet off Route 66, in the Mojave Desert and surrounded by endless nothingness, stand two striking lion-dog-like statues: Foo Dogs, they are called in the Western world. These around five-foot white marble statues, muscle-bound and fierce in appearance, with intricate detailing and striking, magnificent manes, sit stoically just about four miles east of Amboy, California. Mounted on cinder block pedestals, approximately 1.4 miles apart, these exotic beasts of the Orient seem to stand guard over something or, perhaps, someone. However, their presence here in the barren land, tormented by a relentless sun, remains an imposing mystery. Who, and what, are they protecting? How did they get here, and why? We love a good mystery and this one has perplexed travelers for a long time!

“It is completely empty. It is nothing but desert out there, it’s the Mojave Desert. There’s nothing around these lions for miles,” said Beth Murray, a member of the California Historic Route 66 Association. “It’s a big nothing patch of land with two statues about which no one has any freaking idea. I mean, the entire roadie family who prides themselves about knowing everything about Route 66 has no idea where these lions came from or how they got there.”

The history of Chinese guardian lions dates back thousands of years to the Han Dynasty. Symbolically seen as protectors, they were always featured in pairs, with the male on the right and the female on the left. These mythical animals were placed in front of entrances to temples, tombs, and other structures to guard and ward off spirits and intruders. And so it is with the Mojave lions. While the physical appearance of the Mojave lions may seem similar, each is identifiable by the symbols that they hold: the male, caught mid-roar, is on the right with its left front paw resting on a decorated ball, symbolizing the building or structure under his protection. To the left, is the

female with a lion cub under her right paw, representing the nurturer and protector of people dwelling within the home or structure. Which begs the question: why are there guardian lions out in the middle of nowhere without a building or person in sight to protect?

Stories of the sighting of the Mojave lions started popping up sometime in late 2013. Any leads as to what spawned them gave up nothing but a few sparse anecdotes of people who recalled seeing them outside a restaurant in San Bernardino, and hearsay about a Chinese company that was looking to create a luxury getaway spot out in the desert.

“So, there was a gentleman that lived out there…” continued Murray. “He’s passed away now, but he told the owners of the Roadrunner [Cafe] that there were plans on doing a kind of Palm Desert Resort.”

Perhaps issues with infrastructure led to this potential resort being canceled. Maybe someone decided it would just be fun to drop these statues out in the desert as something interesting in the Mojave for other travelers to ponder. Whatever the reason, the Mojave lions have become a much-visited roadside attraction where travelers have attached their own meaning, often leaving memorials, mementos from coins, teddy bears, and flags, to jewelry. There was even once a Facebook page dedicated to the Mojave guardian lions. But to date, no one has come forward to claim them.

Whatever these guardian lions were once intended for, now they stand as a marker for travelers heading down the National Trails Highway, an oddity in the high desert to be examined and to spark interest in just what else is hidden in the sand and dust beyond where the road ends. One thing is for certain: these creatures, who represent an ancient history, acting as gates without doors or walls, are now guardian protectors of the Mother Road and all who travel it through the desert.

With a population of 981, Odell, Illinois, is undeniably a quintessential Midwestern town. Its motto, “A small town with a big heart where everybody is somebody,” captures its welcoming spirit. Nestled on Route 66 in Livingston County, Odell is a mere 76 miles from bustling Chicago, but the energy in the town could not be more different. It holds a serenity, a charm that is somewhat unique to Illinois’ stretch of Mother Road. Today, the town attracts roadside travelers keen to visit its beautifully restored 1932 Standard Oil Gas Station, now a Route 66 visitor center, and maybe stop for a bite at Cafe 110 West, but it was not always so sleepy. As a matter of fact, for a period of the town’s history, it was downright busy! During Route 66’s heyday, the town bustled to the extent of requiring a pedestrian tunnel for those on foot to safely cross the busy two-lane highway.

From 1921 to 1922, Odell witnessed the construction of the “Chicago-Springfield East St. Louis Road,” later renamed Route 4 and designated as Route 66 in 1926. Route 66, which cut straight through the center of Odell, brought both opportunities and its fair share of challenges. While it provided small-town residents with access to a major highway, it also disrupted their tranquil streets with increased vehicle traffic. It also impacted pedestrian safety as streetlights and stop signs were scarce in Odell during that era.

In 1946, a significant development occurred with the construction of a four-lane bypass of Route 66 located just one-fourth mile west of Odell. As a result, the bulk of traffic traveling between Chicago and St. Louis bypassed Odell, altering the town’s dynamics. “They still had crossing guards because there were about 11 gas stations that were still on West Street,” said Dave Sullivan, a Route 66 historian who attended St. Paul’s Catholic School. “There were a ton of gas stations and restaurants that were in Odell. And a lot of the houses, if you lived on West Street, you would just put in gas pumps by your house and sell gas during the daytime. An unbelievable number of people did that. In the small towns, that really happened a lot. I worked on Route 66 [during] high school, at a gas station, and it was just a great little town to grow up in.”

Student safety was a paramount concern for those attending St. Paul’s Catholic School in Odell. With the eastwest commute posing risks, the town and church authorities opted for an underpass instead of a stop sign. Therefore, in 1934, a 30 to 35-foot tunnel was constructed beneath Route 66 at the intersection of South West Street and West Hamilton Street, coinciding with the church’s location. This tunnel not only safeguarded students but also served as a passage for church members. Affectionately dubbed the “subway,” the Odell Pedestrian Tunnel became a symbol of community protection and convenience.

During that era, Pontiac, Illinois, situated a mere 10 miles from Odell, faced a similar predicament. Recognizing the parental concerns surrounding their children crossing Route 66, a comparable tunnel was erected in Pontiac. This tunnel catered to students attending the Ladd School, ensuring their safety, and easing the worries of the community.

While the St. Paul School continues to serve students from pre-kindergarten to eighth grade, St. Paul’s Catholic High School ceased operations in 1966 and the high school building was demolished in 1971. Coinciding with this — and as traffic dwindled — the tunnel was filled with gravel and securely sealed with cement, rendering it unusable. Similarly, Pontiac made a formal request in 1972 to 1973 for the removal of their tunnel. “The [Pontiac] tunnel became more of a nuisance than an asset. I’ve had some of my friends tell me that they got their first kiss in the tunnel in Pontiac. It was a hangout for a little privacy for teenagers. That is why the school board asked the city to ask the state to remove it,” said Sullivan.

In 2006, the Route 66 Association of Illinois Preservation Committee, alongside local residents, convened at the former entrance of the South West Street tunnel in Odell. Their shared objective was to honor history by unearthing a portion of the tunnel’s stairs, a meaningful act of preservation. A solitary marble was discovered on the second step, an artifact now housed at the visitor center. Additionally, committee members installed railing reminiscent of the original design along three sides of the partially unearthed tunnel, while a chain was placed across the front for added protection. Concurrently, a historic marker was erected beside the former entrance on South West Street, serving as a testament to Odell’s rich past, forever intertwined with the legacy of the iconic highway.

In the early 20th Century, the idea of a cross-country route connecting Chicago to Los Angeles began to take shape. It was a time when the nation was on the cusp of transformation, and the call of the open road beckoned to those hungry for exploration. In the Midwest, the original proposal was to bypass the towns of Waynesville, Lebanon, and Marshfield, because there were too many rivers to cross and the landscape too hilly. Fortunately, a group of insightful Lebanon community leaders lobbied the Highway Commission for a more direct route through their town. Their efforts paid off and the new U.S. Highway 66 through Lebanon was mapped out in 1926. The town became a vital pit stop along the highway, birthing iconic places like the Munger Moss Motel with its amazing, flashing neon sign.

However, as the years rolled on, interstate highways bypassed Main Street, and the once-bustling Route 66 in Lebanon fell silent. But the spirit of the road was not so easily extinguished.

A revival would be ignited in the form of a 36,000 square foot space: the Lebanon-Laclede County Route 66 Museum.

To better understand the museum, one must dive into the town’s library itself. From 1896 to 1936, Lebanon lacked an official library. Then everything changed on June 6, 1938. The city received its first library, later expanding to a brand-new building at 135 Harwood in 1951. Ten years later, they merged into the Lebanon-Laclede County Public Library.

Though it was a community effort, two men helped kick-start the project: Bill Wheeler, former president of the Lebanon-Laclede County Route 66 Society, and Gary Sosniecki, ex-publisher of The Lebanon Daily Record . With their proposal approved by the library board, Wheeler and Sosniecki took to the road for inspiration.

“We drove from Lebanon all the way to Joplin to stop at small museums and libraries to get some ideas,” explained Sosniecki. “And we sat down in a cubby hole at the Joplin Library… and we sketched an idea for the museum and how it should be laid out. And I was amazed, years later, that the architect adopted many of the ideas we had in that sketch.”

In 2004, the Route 66 Museum opened its doors to the world. Built within Kmart’s former garage, visitors to this self-guided museum are welcomed with a giant Route 66 shield displayed across the sleek floor, alongside a colorful mural painted by local high school students depicting vintage landmarks from the west to the eastern side of Laclede County: the Harris Cafe and the Harris Cabins from Conway, Missouri, to name a few. Filled with exhibits that showcase the evolution of Route 66 — from its humble beginnings in the 1920s to its heyday as the Main Street of America — the vintage gas

But there was a problem: the one-story Harwood Building’s space was limited.

In 2000, the library board responded to the demand for a bigger space, but they were struggling to find an adequate home. Fortuitously, the old Kmart in town was put up for sale, and with 60,000 square feet of space, it had more than enough room for the hefty collection of books and then some. The library board purchased the building in 2002, and a $6 million remodeling project began in 2003. Around the same time, a group of passionate locals, fueled by a deep appreciation for the cultural significance of Route 66, had a vision to include a Route 66-focused museum in the library. A place that would honor the Mother Road’s legacy in Lebanon.

pumps, neon signs, photographs of the town’s motels, diners, and roadside attractions all offer a glimpse into a beautiful bygone era. One of the museum’s most prized displays is a replica Phillips 66 gas station with two pumps and a black Model A brewing car.

“We decided on that location because there’s a garage door where you can pull classic cars into the museum and change them out periodically,” said Sosniecki. “It became a lot easier, when someone donated a car, just to be in the museum.”

From a retro diner featuring a classy jukebox and an old cash register, to a detailed diorama dedicated to Colonel Arthur Nelson’s “Nelsonville” — whose land donation was fundamental in Route 66 running west of Highway 5 in Lebanon — the Route 66 Museum stands as a guardian of memories and a storyteller of a bygone era that reminds visitors of the importance of this quiet Missouri county.

MORE THAN

By Cheryl Eichar Jett

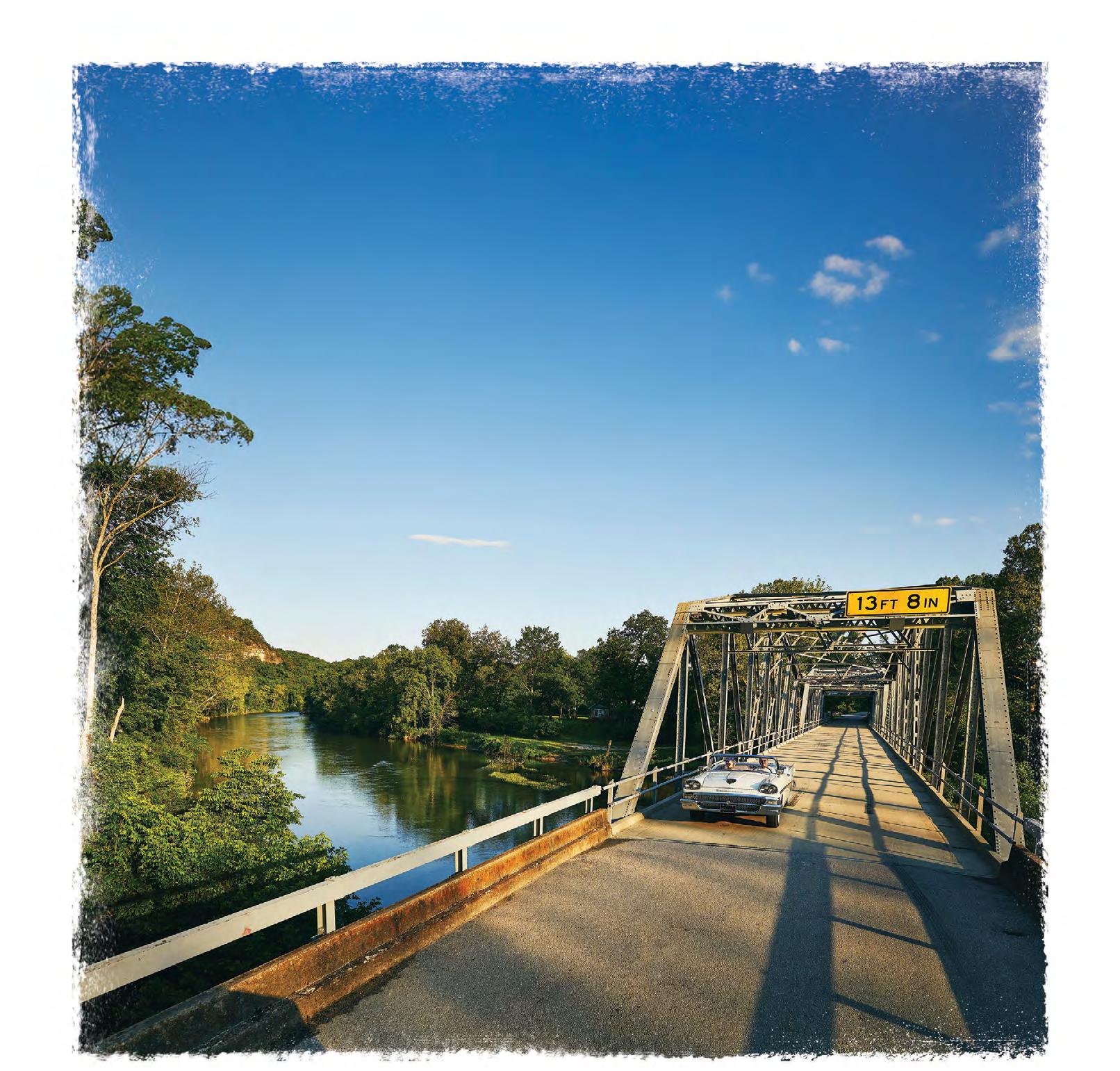

Photographs by Efren Lopez/Route66Images

By Cheryl Eichar Jett

Photographs by Efren Lopez/Route66Images

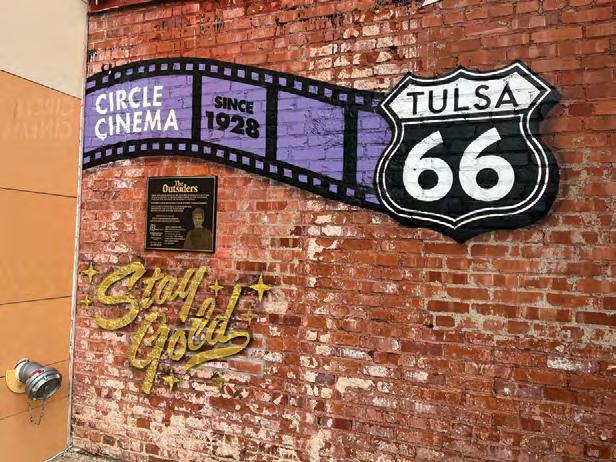

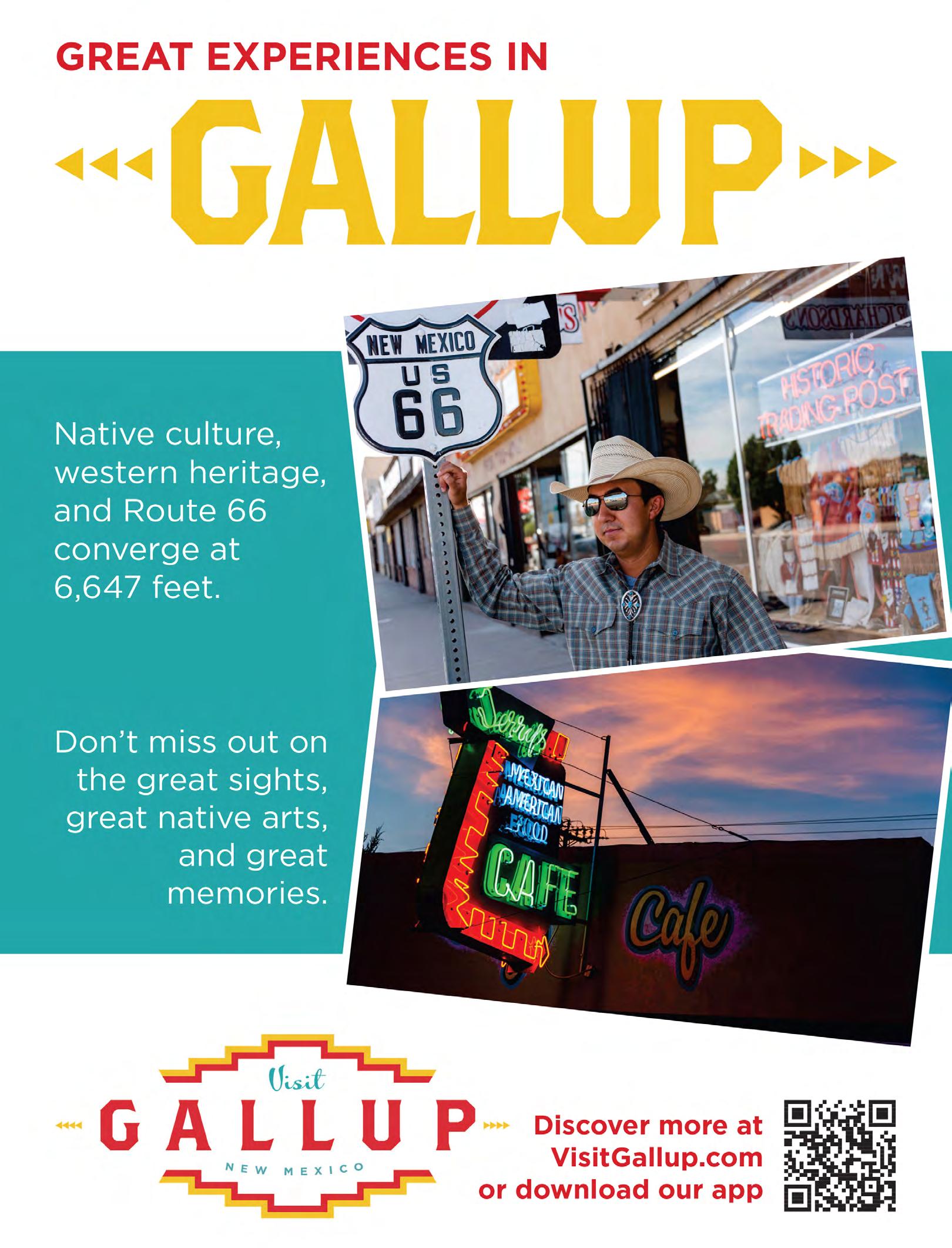

Vinita, Oklahoma, has not been called “The Crossroads of America” for nothing. The second oldest town in the state, it was along the path of the Texas Road cattle trail and later the Jefferson Highway, part of the early National Trail System. (Today, U.S. Route 69 approximately follows the path of both earlier roads.) When U.S. Highway 66 began its east-west crawl through Oklahoma, it cut right across Vinita at the southwest edge of town. Not known just for its plethora of roads, Vinita was originally established at the crossing of the Atlantic and Pacific — now Burlington Northern Santa Fe — and the Missouri, Kansas, Texas — now Union Pacific — Railroads. The city is still an intersection point for those two railroads, plus nowadays, the town is known as the “Crossroads of Green Country,” the Northeastern corner of Oklahoma. In 2000, a crossroad of another kind was faced by a young couple in Dallas, Texas, who wanted a richer family life for their growing family — including grandparents. Would they stay in Dallas with their own parents scattered elsewhere? Or could they find the perfect spot for all to agree to move to? Eventually, they settled on Vinita, where after a bit of time, they would serve travelers passing through town on all those old roads (plus Interstate 44) with a modest motel and a café next door that, with a newly-restored neon sign, a Muffler Man, and a Big Indian, splashed itself all over social media in 2023.

Tom Schwartz Builds a Café — Twice

The café got its start when in the mid-1950s, a young Oklahoma man, Tom Schwartz, had an idea. As a child of Vinita, he had watched the traffic whizzing through town on east-west Route 66 and observed the north-south travel on the Jefferson Highway. He saw an opportunity. On an auspicious spot southwest of town, Schwartz built a truck stop with a café and a small motel to garner a share of the business from all those motorists. He called it “Champlin” Truck Stop, but today, no one seems to know why he chose that name for his enterprise. Like much along America’s Main Street, this nugget seems to be lost to history. But whatever the name, Schwartz was in business. That is, until the early 1960s, when the Oklahoma Highway Department let Schwartz know that new westbound lanes to make this stretch of Route 66 a fourlane highway would be constructed right through his truck stop, which would be condemned. The State of Oklahoma bought him out and put his buildings up for sale by auction. Apparently undiscouraged, Schwartz bought his buildings back — except for the tiny motel — and hired a crew to dismantle and move them 100 feet north. There, he began to rebuild his business, reusing everything he could. But he took things a step further in this location. He installed a neon sign

of his own design, and his rebuilt eatery became the Hi-Way Cafe. It opened in 1963. From that point on, the café has been open continuously under one operator or another. Schwartz himself did not run it for long before a string of other operators took over the café, changing hands every now and then throughout the rest of the 20th Century and into the 2000s — through good times and bad.

In Dallas, it was about the year 2000, and Beth and Alan Hilburn, who had been high school sweethearts, had a good life together. Beth worked in the marketing department at American Airlines, and Alan had his own trucking company. And they had a young daughter, whose care they shared so she didn’t have to go to daycare. But they wanted more. They craved a family setting somewhere where they could be near Beth’s parents, at that time living in west Texas, so that their children — there would be two more — could grow up with grandparents nearby. Beth remembered growing up without her grandparents nearby and didn’t want her children to experience that, too.

They began looking in Oklahoma — Beth had grown up in the Sooner State and still had cousins there. And then Beth’s parents, Bill and Barbara Wood, settled the issue. The Woods had experience operating small motels, and when Beth discovered the Western Motel on Route 66 just outside of Vinita, Oklahoma, the Woods knew the right thing to do to make the family dream of living near each other come true. Purchasing the Western Motel, they moved to Vinita from west Texas.

The Hilburns followed in September 2001, leaving Dallas behind. Conveniently, a charming “giraffe rock” 1940s-era house with 40 acres sat just west of the Western Motel. It was available, and the Hilburns moved in. There, right next door to her own parents, Beth and Alan raised their children alongside their grandparents. At first, Beth commuted back and forth to Dallas to keep her marketing job, but then she reached another turning point.

“We were rolling along, and then about eight years into [my parents’] ownership of the Western Motel, the café, which was a struggling Mexican restaurant at the time, went up for auction,” Beth explained. “My dad said to me, ‘I am thinking about buying the café next door, just because it’s a good business decision. I would like it if you would run it for six months, just to get it off the ground.’ And I was like, ‘Oh, okay, anything you need me to do.’”

Bill took his daughter up on her offer and proceeded to buy the Hi-Way Cafe at auction on March 24, 2011. From that day on, Beth and Alan’s daily lives changed immediately, from a steady routine of domestic life and employment elsewhere to playing every role in running a small-scale eatery.

“My dad signed the papers in the morning, and Alan and I took over that afternoon as cook and waitress. The old owners left, and we just walked in. We never even closed one day,” said Beth. “It was crazy, but we knew that we had payments, so we just went to work. To me, that shows exactly what a small business person does. It reminds me of a duck — you’re smiling on the top of the water but underneath you’re pedaling like crazy just to get going.”

Beth and Alan kept pedaling through the years as their clientele grew. And eventually, they ended up with the

‘50s-era Western Motel as well, after Bill Wood, her father, passed away in October 2020. “It was just too much for my mom to run without him. She was alone with just the memories. So, we moved her to our house and then we took it over that following January. Really, the last 10 years of my dad’s life there wasn’t a lot of maintenance that was done. So, we’ve remodeled 18 of the 20 rooms so far, which is super fun. Some are Route 66-themed and have pictures of the motel from the early ‘70s and pictures of the café — what it looked like back in the day.”

In 2022, two grant applications were submitted that paid off big time. One would have a huge impact on the café’s visibility and popularity — it would restore the iconic redwhite-and-blue sign that Tom Schwartz had designed back in 1963. The Hilburns, the Oklahoma Route 66 Association, and the Route 66 Association of Missouri’s Neon Heritage Preservation Committee had begun the cooperative process early in 2022 of applying to NPS for a 50/50 cost share grant by National Park Service, part of its Route 66 corridor preservation grant program, to restore the Hi-Way sign. This grant application was accompanied by 20 letters of recommendation — more than any other neon sign project submitted to the NPS grant program in its 22-year history! The grant was awarded later in the year and the sign was taken down on January 6, 2023, for its restoration by Encino Signs in Tulsa. New glass tubes were shaped by hand to replace the neon that had gone out decades earlier. And the

colors for the new paint job were accurately restored thanks to a 1980s photograph luckily taken by Route 66 artist and photographer Jerry McClanahan. (More about the sign’s return and re-lighting event in just a minute.)

The other successful application was for a grant program backing historic small restaurants, funded by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and American Express. Twenty-five restaurants across the U.S. were selected to receive the grant, and for the Hi-Way Cafe, it meant an additional 30 seats inside the café, outdoor murals, and security cameras and lighting.

While these additions were in progress, the couple’s “giving wall” inside the café, where customers could pay for meals for others who needed them, was getting noticed, and filmmakers arrived to include the café in a documentary. Next, in an incredible chain of events, the Hilburns heard from Mobil 1, who had a muffler man on tour that would arrive in their parking lot in October 2022 for a visit.

“Mobil 1 had decided that instead of spending money on television advertisements, they were going to invest in the road’s small businesses and try to bring awareness to them,” Beth explained. “They started their ‘Keep Route 66 Kickin’ campaign with a Muffler Man with a suitcase — ‘Big Bill’ — in California, and they were transporting him along Route 66 to iconic stops. Their last stop was scheduled to be the Litchfield [Illinois] Skyview Drive-In. There, they actually broke a Guinness World Record for the most dogs at a drivein movie!”

After the 199 officially-counted canines at the Skyview Drive-In, Mobil 1 continued their Guinness Book of World

Records streak with other campaigns, and the Hilburns were interested in participating. Some friends had a 1963 AMC Rambler for sale, which intrigued the couple, especially since their café also dated to 1963. So, as part of the “Keep Route 66 Kickin’” campaign, the Hi-Way Cafe and Mobil 1 began a campaign to achieve the World Record for Most Stickers on a Car: 66,000! Afterwards, the layer of stickers was coated to protect them, and the Rambler was parked in the “garage,” a fun addition to the café with additional seating and a jukebox. On March 7, 2023, just a couple of weeks before the sign re-lighting, another 1963 Rambler was given a home at the café to allow visitors a chance for a photo op and to “sticker” this car themselves with random stickers.

On March 25, 2023, the results of the efforts to get the original Hi-Way Cafe neon sign retored paid off big time, as a crowd of about 200 from at least six states cheered the achievement. Tom Schwartz, the original owner who built the café and installed the sign in 1963, flipped the switch to relight the neon sign, and social media subsequently lit up with photos of the newly restored and installed neon sign. With owner-operators in charge of the Hi-Way Cafe, Tom had moved on up to Kansas City, but made the trip down to Vinita especially for the sign re-lighting event. It’s a good thing that he did because, sadly, he passed away just three months later at the age of 87.

The same day of the sign re-lighting, Beth Hilburn had an exciting announcement with some news she’d been saving for the sign event: Big Bill, the Mobil 1 Muffler Man holding his “Keep Route 66 Kickin’” sign, would be coming back to the Hi-Way Cafe — this time to stay. “The Mobil 1 storyline was that Big Bill had traveled all of Route 66 and he had chosen to come back to the Hi-Way Cafe to live out the rest of his days. I thought it was a great plan. I loved it.” And so, the Muffler Man and his suitcase arrived in April 2023 to stay.

Then, in August, the Hilburns announced that Big Bill would soon have a large friend joining him. The “Big Indian” had stood on the Mohawk Trail outside of Charlemont,

Massachusetts, for 49 years, but his creator Rodman Shutt had passed away. “American Giants” Muffler Man expert Joel Baker contacted Beth to see if they would be interested in buying him from the current owner. The Hilburns purchased the 20-foot-tall Big Indian, who would arrive at his new home in Vinita on November 10 after some restoration.

“To be honest, I couldn’t say ‘yes’ fast enough,” Beth said. “I wanted to preserve him. That was my main goal. The craftsmanship was amazing. I felt like, as a piece of art, he deserved a new home. As a proud Delaware and Cherokee tribal member, it is an incredible honor to be able to bring him to Oklahoma where he can now call the Western Motel and Hi-Way Cafe home.”

If the 2023 attractions put the Hi-Way Cafe on the Route 66 travelers’ map, then certainly the Hilburns’ food delivery service from 2020 to 2021 endeared the café’s owners to Vinita residents. The couple’s answer to two predicaments caused by the coronavirus pandemic — get food to local residents and keep their own employees — was to create a food delivery service.

“We actually went to seven days a week when we started delivering meals to people. We also started delivering boxed groceries to people, so you could order a box of, say, hamburger fixings,” said Beth. “Then, we started doing family style meals. It helped everybody. We were trying to think of ways that we could serve the community and keep us going during that time.”

Now, as 2024 is well into its travel season, other amenities have replaced the food delivery service. A varied menu features something for everyone, and customers can choose to eat inside, where there are now 94 seats, or at a picnic table out under the shade trees. There is a once-a-month Saturday Steak night to try, and during regular hours, it’s worth checking your eating utensils, because an unexpected set of vintage silverware with your meal means a free dessert.

“The Hi-Way Cafe has become a go-to eatery on Route 66, cherished by locals and a rising star among road trip destinations,” said Jackie Stewart, executive director of Green Country Tourism. “Offering a menu brimming with home-cooked fare, it promises an authentic taste of the storied Mother Road. Enhanced by the impressive Big Indian and the iconic Big Bill muffler man, this café stands out as a must-visit landmark on the historic highway.”

Early Oklahoma travelers found Vinita pretty easily — trails and railroads led to the little town. Now highway travelers from all directions can hardly miss Vinita with its attractions and hospitality businesses. A restored neon sign, a Muffler Man with his huge suitcase, a Big Indian, and plenty of good food and fun promotions bring many of them to the Hi-Way Cafe. Here, a couple’s intentions to move nearer to family intersected with an old café that needed a future. You just can’t beat a good crossroads.

Let’s say you are planning a trip down Route 66. This has been a lifelong dream, something that popped up on a social media feed, or something on the news that piqued your interest. Common knowledge has you knowing generally what Route 66 is, where it goes. A couple of Google searches, an Amazon purchase, a visit to some Facebook groups, and you’ve got some maps and a few stops that are “must do’s” along the way. There is a lot of information out there about places along America’s most iconic highway. Stories of historical events, places and monuments, but what makes the trip most interesting is that there are characters at every turn along Route 66 and seeking them out is all part of the fun.

The characters that help turn a roadside point of interest into a celebrated landmark or a “must-stop” are usually as much of the attraction as the architecture or spectacle itself. It is the unique, eccentric, or the larger-than-life personality behind these celebrated landmarks that make all the difference. But rarely do these gallant personalities outlive the curiosities or monuments they have created. Then what? Hopefully, a new caretaker, with as much passion, comes into the picture to maintain the legend and memory. Such is the case for one of the Mother Road’s most acclaimed roadside stops; Gary’s Gay Parita in Paris Spring Junction, Missouri. The hero of the next chapter in the legacy of Gary’s Gay Parita and its creator, Gary Turner, is unsurprisingly his daughter Barb and her incredibly gregarious partner George.

As you head west out of Springfield, Missouri, you can take “Old Route 66,” or I-44 to Route 96. Not too far past the tiny locale of Halltown, the two alignments come to a point, aiming you straight at Gary’s Gay Parita. Right there at Old Route 66 and Missouri County 1210 sits one of the state’s most beloved Mother Road destinations: a replica of a Sinclair Gas Station, twice burned down and resurrected. Gary’s Gay Parita is known throughout Route 66 communities as a must-stop destination, mostly because of its amazingly friendly creator, Gary Turner. A beloved character whose passion for Route 66 — and his ability to sit and chat with anyone like an old friend — engaged and entertained visitors from across the globe. What had initially been built as more of a man cave project quickly turned into a storied Mother Road landmark.

Some history to set the stage. In 1926, Fred and Gay Mason bought 80 acres of land on which to graze cattle and open a gas station and motor court. The station was built between 1926 to 1930 and lovingly named Gay Parita. The name was a combination of Fred’s wife’s name, Gay, and the Italian word for “parity” or “equal”: parita.

Fast forward to 1953, a spark set the station ablaze, burning it to the ground. Not to let a devastating fire snuff out their business, Fred and Gay simply rebuilt the gas station, but yet again, in 1955, the embers of fate had other plans and the station was set ablaze one final time. However, this time, Fred and Gay decided not to tempt a trifecta and did not rebuild. The underground tanks were removed, and the cows roamed freely, but a stone garage remained.

In the early 1980s, the land was sold to Gary Turner’s brother-in-law and sister, Steve and Leah Faucet. During this time, Gary had been working on various enterprises, from being a sharpshooter at Knott’s Berry Farm, to running a used car lot, to professionally driving a truck throughout the Midwest. Gary was not one to sit idle. However, as the years flew past, Gary, along with his wife Lena, began contemplating the next enterprise they could embark on. Gary was planning his retirement. In 2003, he bought the property that the original Gay Parita gas station was on from his brother in-law, Steve, and set to work on a new project. The idea of recreating this piece of history, for the third time was going to be the next adventure in the Turners’ life.

Steve Faucet and Gary’s nephew, Steve Jr., were charged with the construction of the “new” Gay Parita, and there was a lot to get done.

“The idea of Gary’s Gay Parita started in 2003, 20 years ago now, when my Dad bought 2 ½ acres from my uncle. Then about 2006, I believe, is when he started recreating the gas station,” said Barb Turner, Gary’s daughter. “I’m not exactly sure how long it took to build — I was in Charleston — but I know that [initially], there was a gas station on Route 66 that my dad wanted to move here.” But her uncle had another idea. “He said, ‘No, I’ll build one for you on the property.’ So, my dad had my uncle and cousin build the gas station. Back then he used to serve watermelon and stuff under a tree to all the bikers that came by. Then he decided to build the pavilion so that he could feed watermelon to all the motorcyclists and tourists, too. I believe that he built the shirt shop last.”

If you are going to have a reimagined old-timey gas station along one of the most famous roads in the world, you need to make it look authentic. Steve Faucet had a few interesting pieces of gas station memorabilia that he donated to Gary to get the station started, but Gary himself quickly became an avid collector and preservationist.

“My dad really started collecting when he bought the place. I think he wanted to give something back to Route 66. He was a truck driver, he was born in Missouri, and we actually lived off Route 66 in Springfield. We have an original sign out there from when Gay and Fred owned the place. My aunt and uncle said that they pulled it out of the dirt when they had the property. So, it’s in pretty rough shape, but you can see where it says cabins on it, and it was for Coca-Cola. So, it’s neat,” continued Barb.

Gary’s Gay Parita was on its way to becoming a Route 66 must-stop icon over the next dozen years. Gary became known along the Route as a sociable and knowledgeable

character who could sit and talk to anyone from anywhere. Gary and his wife became well-known and beloved among travelers and fellow Route 66 merchants.

In 2014, a series of health issues hit both Gary and Lena causing the project to take a back seat and close while the couple sought treatment.

Gary had been a lifelong smoker and emphysema, heart attacks, and a stroke had taken their toll. Lena, too, was not well and suffered from diabetes and cirrhosis of the liver. Travelers would continue to stop, however, and take photos — but there was no Gary or Lena to greet them. Sadly, on January 22, 2015, Gary passed away and, not long after, on May 18, 2015, Lena followed her husband of 56 years.

Gary’s Gay Parita had become a destination along a long, narrow historical journey. His business was a picturesque recreation of a time that once was, a true draw in its own right, but Gary himself was as much, if not more, of the pull for the crowds. With the passing of the entertainer, the owner, the soul behind such a place, one wonders if the attraction can carry on without them. What does it take to carry a legacy? Without a focus on preservation, often iconic landmarks simply get sold and repurposed, and something more profitable is put in its place. This was the crossroads of Gary’s Gay Parita. Almost a year had gone by since Gary and Lena had passed, and while relatives

had pitched in to secure and maintain the property the best they could, there was no one there to greet travelers. Signs started to get pilfered, the weeds grew — a reminder to those who had hoped to see Gary or Lena that they were no longer there — and an era had truly ended. But there was a glimmer, a slight hope still in the family.

During Gary’s hospital stay in January of 2015, his youngest daughter, Barb Turner-Barnes, made a promise to her father that she would return home and take over the family business. She would be the one to carry on the torch that her father and mother had lit on Route 66.

“I told my mom, it’s not going to be a process where I can’t get here in a week, because of course, I had to get rid of a lot of things. I had to put my house on the market. It’s a process of getting all those things done. And then I had worked for Carmike Cinemas for 23 years. I had to let them know a while in advance because I didn’t just want to put in a notice and say, okay, bye. So I let them know once my house and stuff was sold, that I would be moving back to Missouri to reopen my dad’s station. When I told George what I needed to do, he was [like], ‘Okay, let’s do this’; he was super supportive, but it was probably a nine month process to get ready and make the move. We got here, April 1st of 2016.” said Barb.

After Lena’s passing, and before Barb and George could get moved back to Missouri, there needed to be an action

plan for the property. “We locked everything up. I told my aunt and uncle that I wanted to leave the signs out, because we had so many tourists that came by, and they knew that my parents had passed. I didn’t want it to feel like it was just gone. Everybody was already devastated about the whole thing. So, I said, ‘Let’s leave the signs.’ And my aunt looked at me and she said, ‘I’m not sure that’s what you want to do because people are going to come and steal them.’ And I said, ‘Surely they wouldn’t do that.’ Well, we had 14 signs taken, so I probably shouldn’t have left them out. But, I felt like we had to keep it alive so that people could come by and at least have something to remember the place by. So, after that happened, my aunt and uncle took the rest of the stuff down. When George and I got here, they came out and we started putting all the signs back up. We’re still putting signs back up and we’ve been here since 2016.”

Among the family, Barb and George were in the best position to take over the business. Both had traveled extensively in their younger lives, which helped with the international tourists, and both were ready for a new opportunity; they did not have kids like Barb’s other siblings. They were a natural choice to pull up stakes and take over. “We pulled up with the biggest U-haul and another U-haul with my stuff from Charleston. My parents’ house hadn’t been touched, other than things put away, and secured. We had left it the way it was when they passed. So, we had to go through the process of cleaning everything out, redoing the house, and then putting all of our stuff in. Plus the station — it was a big process.”

Barb, staying true to her promise to her father, opened the gate the first day they were there. Not shockingly, but very emotionally, it became very apparent the effect that her parents, especially her father, had had on the people he interacted with via Route 66. Barb’s thought was to just open up, let people see the process of the station getting up and running with Barb and George taking the reins.

“My whole reason for doing this was to keep my mom and dad’s memory alive. That’s been the most important thing to me about this whole process. I just want people to see what my dad did. We’re constantly fixing up or

adding or replacing pieces. Recently someone contacted us saying they had a duplicate of one of the Sinclair signs that was stolen, if we wanted it. We did some additions to the pavilion… you work for 15 minutes on something and then someone stops by, they’re our first priority, so it just takes time to get things done. If my dad was here, we would totally be bumping heads though. He wanted the place the way he wanted it. It’s a guy’s dream to come here and see all this stuff, but I wanted it to be a girl’s dream too, so I planted all these flowers and gardens. The flowers are also for my mom.”

Carrying the weight of parental loss and the grieving process along with holding up a large personality’s legacy is a tall ask for anyone. But Barb and George busied themselves with settling in and getting reconnected with Missouri and the family business. Travelers and visitors would stream in throughout the day, eager to meet Gary’s daughter, excited to meet George, and to see Gary’s Gay Parita open again.

“It was hard to grasp people coming in and crying because they were like, ‘Are you Gary’s daughter?’” said Barb. “They’d meet me and start crying. I was like, wow. It was hard for me losing them, then being back at their place, and they’re not here. Sometimes it still gets emotional for me. I love talking about them, but it’s hard for me to do it all the time. It’s a lot easier for George, and he does a great job of it. I’m thankful for all the past generations that got to come and see this place when they [her parents] were here, and when my aunt and uncle were here, when my dad recreated the station. There are a lot of memories. And that’s what it’s supposed to be: a getaway from everyday hectic life, a vacation down the route, seeing those things that past generations made for us.”

Every day, Barb and George meet people from all walks of life, from all corners of the globe. Route 66 has been the string that threads so many people, places, and generations together. “There’s just something about this road. I find being here so comfortable, being amongst the old things. Meeting all these people on the road and talking to people from across the globe. I love it. The road unites people, even as it’s constantly changing, it unites us,” said George.

“My dad put so much time and energy, so much money… everything into this place. I want it to always be my dad’s station. That’s what it is, and what it’s always gonna be,” Barb shared.

Today, Barb and George are in the role of caretaker and advocate. They’re taking care of the home and business that Barb’s family built, and they’re advocating for the legacy left behind by the experience that her parents gave to travelers on Route 66. Gary’s Gay Parita, Gary and Lena, the people they touched, are all part of a story that Barb and George get to retell while making new memories and adding to the legacy that her parents started some 20 years ago.

Wilmington, Illinois. Established as a mill town for local farmers in 1836 by Thomas Cox, Wilmington has had a rich and diverse history that includes its early beginnings as a bustling riverfront community, serving as part of the Underground Railroad during the Civil War and, eventually, to becoming an iconic stop along America’s Main Street. They even have their own muffler man giant — Gemini! Nowadays though, one of the things that Wilmington is most known for is its charming thoroughfare known as Water Street.

This historic road, with its timeworn buildings steeped in tales of yesteryear, held the heartbeat of the town, its destiny intertwined with the river. As ships and barges navigated the waters of the Kankakee carrying goods from one riverbank to another, Water Street, which ran along the banks of the river, became a hub for merchants, traders, travelers, and farmers. The town flourished boasting a post office, a general store, several hotels, banks, and other establishments all along this riverfront rue.

As the decades passed, Water Street flowed through the eras of coal mining, the industrial revolution, and the evolution of transportation. But as times changed, with businesses coming and going as needs changed and the economy shifted, Water Street found itself quiet, dotted with empty, abandoned buildings.

the little five-and-dimes closed up. Well, Wilmington filled that little niche up with antique shops, and it’s been very profitable.”

Today, Water Street stands as a blend of historic charm and modern vibrancy, where 19th Century architecture meets quaint stores and fun local eateries that now fill the once abandoned premises. Vintage buildings with aged brick exteriors and faded colors, lined one after another in a neat row, all hold a story that has shaped the town’s narrative: a one-story brick post office, a traditional barber shop across from a simple café and, at the end of the road, at the intersection of Route 66 stands the 1836 historic Eagle Hotel — the oldest commercial building in Wilmington. Giant murals tell tales of the town’s past, another celebrates Route 66 heritage.

With the antique shops came more tourists, mostly along Route 66, hunting for history and eager to take home pieces of it from local stores. Luckily, the tourism reflected from the antiquing boom of the decade has carried through to modern day, marking it as an important part of Wilmington’s story.

Threatened with being washed away into the echoes of the past, but determined to preserve the legacy of Water Street, Wilmington community members rallied together to take advantage of the antiques trend that was sweeping through much of the U.S. in the 1970s. They filled their empty buildings with local traders who were ready and willing to meet the demands of a growing antiquarian population.

“The first antique shop I remember was probably in the ‘60s. During the ‘70s is when they really started taking off,” said Bill Weidling, former Wilmington mayor and current president of the Wilmington Area Historical Society. “It’s kind of turned into a little antique destination. And that’s one [area] where Wilmington is pretty darn lucky. A lot of the smaller towns, you know, as their big box stores came in,

“The most important thing about saving that history is that that is what people want to come to see. If you don’t have something of unique interest, then nobody is going to stop. Hence, people like to go to see things like the Liberty Bell or the Statue of Liberty,” said Weidling. “It’s a unique item and the history is all part of it. In Wilmington, it started with the antique shops. [We] started getting more and more people coming in and it’s just grown bigger and bigger. I think that’s when [businesses] realized that people liked to collect antiques. People just started filling those empty stores up.”

In the heart of Illinois, along the Kankakee River, the once empty shops looking for new life, now stand as a prominent piece of Wilmington’s history. Water Street remains not just a thoroughfare, but a living, breathing testament to the enduring spirit of a community bound together by the flow of time and the stories etched into the very fabric of age-old buildings that continue to define the town’s vibrant history. Yet another beautiful discovery to be made when next on a Route 66 adventure.

Roadside art and quirky attractions have delighted American travelers for decades. Some famous highways like historic Route 66 provide a plethora of oddities that capture the imagination, offering a glimpse into America’s creativity and love for the unusual. However, some of the most extraordinary roadside curiosities are found well off of the beaten path.

Down in the desolate Californian desert, neatly tucked off of the black tar strip of Interstate 10, stands a surprise for road travelers. A big surprise! Towering over the gently wavering palm trees of the tiny community of Cabazon, are two legendary specimens of architecture: Dinny the Brontosaurus and Mr. Rex the Tyrannosaurus — and their story stands about as high as they do.

One day, while walking down the neon-washed, resort paved streets of Atlantic City, New Jersey, a young boy named Claude K. Bell encountered something that would have an impact on his life in a huge way. A 65-foot-tall novelty structure, in the shape of an elephant, lovingly named Lucy, caught Bell’s eye and attention. What made Lucy stand out — besides her imposing size — was that her belly hosted a small museum that was accessed via a spiral staircase. Inside Lucy’s belly were charming exhibits that told the story of her fascinating history, while an observation deck on her back provided sweeping views of the surrounding landscape. A young Bell was smitten. Lucy’s elaborate design and ingenuity would inspire his own creation years later.

After many seasons of working as a sculptor and theme park artist at Knott’s Berry Farm in California, where he and his second wife, Anne Marie, also operated a portrait studio, Bell determined it was time to bring his childhood inspiration to life. So, in 1964, on a 62-acre property in Cabazon that he had purchased in 1946, Bell set to work on an 11-year labor of love that would inspire sojourners from across America to behold his masterpiece.

Bell envisioned Dinosaur Gardens, a prehistoric-themed attraction that would draw motorists off the freeway and to his truck stop restaurant The Wheel Inn. His initial creation consisted of a steel skeleton framework that stood unfinished for some eight years, promoting many “What is it?” questions. Eventually, a neck, head, and hardened skin, made from shotcrete, were added to the steel frame, bringing to life a primeval beast that towered at a staggering 45-feethigh and spanned an intimidating150-feet from neck to tail. “In the next [30] years, I’m going to build an entire family of dinosaurs here,” said Bell, in an interview on April 12, 1970, with a reporter from the Eugene Register-Guard newspaper. “I’ve always been a nut for prehistoric animals. [Dinny] will be the strongest dinosaur ever built, [and] the first dinosaur in history, as far as I know, to be used as a building.” Dinny the Brontosaurus was completed in 1975 and featured a doorway in the tail, with stairs leading into its belly. An 18-by-56-foot main room served as a museum and gift shop. Despite facing financial challenges and skepticism from critics, Bell remained committed to his vision. With his creative gears still spinning, Bell set out to build an even

more impressive sculpture—a lifelike Tyrannosaurus Rex. Though Bell originally planned to make the jaggedtoothed tyrannosaur 90-feet-tall, by the time Mr. Rex was unveiled to the public in the early 1980s, he stood at 65-feet-tall — mimicking Lucy’s height. With Rex, visitors would be able to climb into the beast’s mouth and get a unique view of the tranquil desert landscape through its razor-sharp teeth.

Notwithstanding their eccentricity, it was not until 1985 that the dinosaurs really became a public sensation and were firmly put on the cultural map as a roadside destination. Featured prominently in the cult classic Pee-wee’s Big Adventure , the world was introduced to Bell’s enormous creations via an unexpected, but rather appropriate, cartoony character named Pee-wee Herman (Paul Reubens). In the film, Pee-wee is on a cross-country trip in search of his stolen red bicycle. His journey has brought him to a diner in Cabazon where he meets a troubled waitress, Simone. Entering Mr. Rex’s head to have a heart-to-heart conversation with Simone, events take a bad turn as Simone’s jealous boyfriend, Andy, misinterprets their friendship and chases Herman around Dinny’s tree-trunk thick legs while swinging a giant bone club. It is a comical scene that has inspired thousands to make the trek in search of the Cabazon Dinosaurs.

“Because they are concrete and monolithic, you can see them from the interstate,” said Doug Kirby, co-author of the Roadside America website. “So, not only were they a local curiosity, but it was something that people coming to and from Los Angeles could see. They were the closest dinosaurs to a metro area, which garnered them a lot of attention — versus some of the other dinosaur statues which were older around the country but located in more obscure places... [like] the middle of the desert.”

Among the scattered blueprints within Bell’s dusty workshop were also ideas for designing a woolly mammoth and saber-tooth tiger sculpture. However, these were not to be. In 1988, at the respectable age of 91, Bell passed away from pneumonia before his full vision could be realized. The restaurant closed in 2013 and was bulldozed in 2016, but thankfully, the dinosaurs have continued to thrive, honoring the memory of their creator amidst the scattered palm trees of Cabazon.

Today, the Cabazon Dinosaurs are part of a creationist museum owned by MKA Cabazon Partnership, a company that bought the land and dinosaurs from Bell’s family around 1996. Despite the shift in management, the dinosaurs remain a source of inspiration, bringing smiles to both adults and children. Besides painting the dinosaurs different colors to honor specific holidays, the new owners continue to fulfill Bell’s original purpose, allowing visitors to roam around the inner bowels of these concrete creatures — albeit for a price.

The Cabazon Dinosaurs epitomize the quirky and nostalgic atmosphere that harkens back to a bygone era of kitschy American roadside attractions. And with a little luck, they will remain spinning within the machine of modern pop culture for decades to come.

Melissa Etheridge is not just a musician; she’s a force of nature, blending her raw, soulful voice with poignant lyrics to create an indelible mark on the music industry. Born in Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1961, Etheridge’s journey to musical stardom is as inspiring as her powerful vocals.

Her rise to fame began with her self-titled debut album in 1988, featuring hits like “Bring Me Some Water” and “Like the Way I Do,” which showcased her gritty vocals and unapologetic lyrics. Throughout her career, she’s continued to captivate audiences with her honest songwriting and electrifying performances.

Etheridge has amassed an impressive array of accolades, including multiple Grammy Awards and an Academy Award for Best Original Song for “I Need to Wake Up” from the documentary “An Inconvenient Truth.” Her discography boasts a string of hit songs like, “Come to My Window,” “I Want to Come Over,” and “I’m the Only One,” each track showcasing her evolution as an artist, while staying true to her Midwestern roots.

Yet, Etheridge’s life took a poignant turn in 2004 when she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Rather than succumbing to fear, she confronted the disease head-on, becoming an advocate for breast cancer awareness and a symbol of strength for countless women facing similar battles. Her openness about her struggle, including her decision to undergo chemotherapy and her subsequent journey to recovery, resonated deeply with fans around the world. Despite the challenges she faced, Etheridge never allowed cancer to dim her creative spark. She continued to produce music that reflected her resilience and determination, earning critical acclaim and accolades along the way. Her willingness to speak out on social and political issues — combined with her electrifying stage presence — has inspired generations of fans to stand up for what they believe in.

Melissa Etheridge has left a lasting impression on the world, inspiring countless individuals to find strength in their own struggles and to embrace life with unwavering passion. In this conversation, discover the fascinating journey that this musical icon made to arrive where she proudly stands today.

You started singing and songwriting at a really young age. How did you decide that you wanted to become a songwriter and pursue a career in music?

It was the late 1960s, early 1970s, and there was great music: it was everywhere. There was one radio station — you got it all in one place and everyone heard the same things. WHB 710 Radio, which was the radio station in Kansas City, would play the Jackson 5, then you’d hear Tammy Wynette, Led Zeppelin, then a Frank Sinatra song. So, it varied, but it was all this great music. We constantly listened to the radio at home. When I was young, my parents would bring home albums… The Mamas & the Papas, Aretha Franklin, and I would listen to them over and over. My mother would also have classical rock records. I fell in love with music.

When I was a kid, my biggest influence was probably The Archies , the cartoon. I watched it as a child, and I thought, “They’re in school; they’re playing instruments.”

When I was eight years old, my father brought home an old Stella Harmony guitar for my sister, but she didn’t play it. They finally let me play it, even though they said I was too young. Then, by the time I was 10 years old, I was really playing the guitar and writing.

Do you remember the first song that you wrote?

Yes! (Laughs) Well, I remember the first song that I wrote as a 10-year-old. “We were on the bus.” I rhymed “Gus” with that, then I would write “Love, don’t let it fly away, it’s love.” Like protest songs, when I was 10! This would be 1970 and 1971. When I was 12 years old, my grandmother passed away, and I wrote my first real song, “Lonely as a Child.” It was sad. It was about a child in a war-torn country, losing its mother. It was very sad. I liked that people had an emotional reaction, and I kept writing sad, emotional songs. I played in bands, I played cover songs, I learned what a hit pop song was. You learn what people like to hear and the makings behind it. I found my own voice when I was 17 or 18.

Death is something that we don’t really understand when we are young. Did you find it cathartic to write that song, to deal with your grandmother’s death?

At the time, I didn’t know that was what I was doing. At the time, I was this kid that was feeling… my grandmother’s funeral was my first time with a death experience. I was moved by the way people gave respect to others who are grieving. It touched me deeply as we were driving to the cemetery. They would not only stop, but they pulled over to the side of the road. It touched me as a 12-year-old deeply. I sat down on the porch, and I wrote that song. Now that I look back, I can see that all of those things were connected, but at the time I was just gonna write a song.

You were very young at the time. How supportive were your parents to your progression toward a career in music?

They weren’t not supportive; that was the best thing. It was quiet, except for my older sister — she made a lot of noise. I would keep to myself and sit in the den and practice my guitar. My father got me a piano when I was 14, and I would write and play. Once I started singing a couple of songs that they liked, they would have me perform for visiting family. It was fun, but I remember once asking my mother at 16 or 17 — I was playing in bands and wanted to do this — I asked her if she thought that I would make it as a star, and she said, “It’s a one in a million chance, but why not you?” And that was enough to get me going.

When you were in grade seven, you started traveling with a local variety show. How did that come about?

I did! It was a fun thing to do on the weekend. It would be once every couple of weeks. He — Bob Hamill was his name, and he came from Philadelphia. I have no idea what he was doing in Leavenworth, Kansas — would gather all these acts together and we would go and play. It was never further than twenty miles. He reminded me of the music man, putting a show together. He was a showman; he was a ventriloquist… He convinced the Chamber of Commerce to put a talent

show on in the plaza, our local mall. It had seven stores, but it was the mall. I was in sixth grade, and my friend said, “Let’s go sing at the talent show.” We got up and sung folk songs. There were acrobats, dancers, [and] little girls and boys singing country songs. At the end of the final night, he said, “Give me your address, and I will sign you up, and you can be part of The Bob Hamill Variety Show.”

He called us up and we would play at old folks’ homes, Kiwanis clubs… then we started playing in the prisons. We would entertain these guys in prison, then we went to the women’s prison and did a show. It was bizarre, but it was delightful. They were crazy audiences; they were hooting and hollering — who knows why — but I enjoyed it. It was my first experience with an excited audience and that made me want to do it more.

Did you get nervous performing in front of people initially?

Yeah, there would be nerves, but it was so close to the excitement of it that it was more like fuel. Things would go wrong, and things would happen, but each experience helps you grow.

You went over to Boston to attend the Berklee College of Music? Was this straight after high school?

I graduated in May of 1979, and then I went to Boston in September. I stayed in Boston for about a year, but I never really wanted to go to school in the first place; college wasn’t anything that I thought about. But my mother wanted her daughter to go to college. So, I thought, “Okay, but it has to be a music college.” I was trained, I could read music, but Berklee was a place where you could major in guitar. There were no other places where that was offered. I got in there, and this is 1979, and in my guitar class of 60 kids, there were only two women. Each of my classes were like that; there were very few women. The talent there was remarkable. I came from a singer-songwriter, rock ‘n roll sort of base, and there’s these jazz guys that are running circles around everything. But I didn’t have a love for it. I had a teacher that told me this has to go after this… I said, “No, it doesn’t. There are no ‘have to’s’ in music,” and he said, “Yes, there is.” So, I sort of ran up against that, and it all fell apart. I got a job in a restaurant, was making a living, and I could have an apartment. I didn’t want to go to school anymore. I stuck around Boston and performed around town for another year.

By 21 you moved to the West Coast?

I turned 20 and I went back to Kansas City, because I lost my job. I don’t know why, but I got fired. I came home, got an apartment, and worked for another year to have enough money to buy a car to drive out to [Los Angeles].

LA can be a very lonely town when you are new and don’t really have a base. When you arrived at 21, did you know anyone? What was the game plan when you started driving West?

Well, I fortunately had an aunt who lived in LA. My father’s sister and my father’s brother both lived there. My aunt lived alone, and my sister had gone out there a couple of years

before and stayed. It wasn’t a good experience, but I didn’t know that at the time. I asked my father if he thought that I could sleep on Aunt Sue’s couch if I went out. (Laughs)

I had been able to make a living in Boston, I’d been able to make a living in Kansas City, and I was self-sustaining and took care of myself. I figured [that] I would go out to LA, get a job, and I’d be there. So, I drove out to California… I stayed in two hotels along the way. That’s all I could afford. I had friends in Oklahoma City that I stayed with, and a friend of a friend that I stayed with in Phoenix. But I got there.

So, I knew my aunt, but I did not know a single other soul otherwise. It was hard.

I quickly figured out that there was no work to be had in LA — musicians were playing for free and not having a problem with it. I was young and meeting women, and one came from Long Beach. We went to this new club called the Executive Suite, and I noticed that there was a piano in the corner. I asked if they had live music and they said no, but the [venue] used to be a steakhouse, and the piano came with the restaurant. They had a disco there at the time, and I told them that I could play before the disco. So, I got a job playing at this bar in Long Beach, like five nights a week, from 5PM to 9PM, before the disco.

I brought people in for cocktail hour. When that ended, because it got popular, and they went full disco, I went to the other bar in Long Beach called Que Sera. It was a women’s bar, and I played there. From that, I got a job at Vermie’s, and I went back and forth from Pasadena and Long Beach every other night. It was brutal, but the cost of gas wasn’t like it is now. Women would come every week to hear me play, I was a draw. There were these women that would come in on Sundays after their soccer games from Cal Tech. One night, one of them asked if I had a demo or something. I had made this demo of one song, and I gave it to her. That was enough to get a manager. He said that he wasn’t interested initially, but his wife came down… she was one of the coaches. So, she came down and she went back to him and said, “You have to come see this girl.” He finally came down and signed me right away. He liked the way that I performed. I was not just singing songs. He believed in me. He said, “I don’t know how long it’ll take, but I think you can make it. I think you have what it takes, so let’s try.”

Then, it was all about getting a record deal. That was the main focus. He started bringing record companies out to see me, and he brought the president of Capitol Records at the time; he was one of his best friends. My manager had managed Bread, and had been in the business for a while, so he was successful. And the guy loved me. It was 1982 or 1983. He said that he wanted to sign me. But then… I can’t tell you how many times I would get in with a record company and then the president would be fired, everybody would go away, and the whole deal fell apart. It was like that with A&M and then Warner Brothers, everybody came out to see me.

Yeah, the business has always been quite fickle. But in 1988 your first album comes out, finally.

Yes, on Island Records! Chris Blackwell himself walks in and literally asked me why I wasn’t signed. This was 1986. He said that he wanted me on his label and then he went away. I didn’t believe him, but he made it happen. I never even had an A&R guy; he loved me and signed me. It was super cool being on Island, but I didn’t know what to do. I’d never made a record before. I’d been performing solo for 10 years. I didn’t have any musicians and there wasn’t a record company guy there to guide me. But Chris said to me, “I want what I heard in the bar.” We had already done the photo shoot for the album cover, and Chris loved the picture so much that he had them blow it up. He had someone put the picture up and said, “Make the album sound like this photo,” so we did.

Your first album was successful right away.

Well, what do you call right away? It was successful on the rock radio in Canada. It was very big in Australia. It was huge in Europe. In America, it was playing on rock radio. They had the difference between pop and rock, but it was nice, and I’m very happy with how it hit. It was perfectly fine, and I was able to play and to go do concerts all over the world. I loved it.

Were you concerned that it wasn’t hitting on the Billboard Top 20?

I wouldn’t say I was concerned. But I was comparing myself to others, and that will make you sad every day, no matter who you are. I did a lot of that. Tracy Chapman’s album and mine came out on the exact same day. So, “Fast Car” was the number one song, but I’m so glad now. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Do you remember the first time you heard yourself on the radio?

Yes, I was in London. Chris always thought that I would break in London first, so he wanted me to be like Chrissie Hynde and The Pretenders, since they got huge in London, then came back to America. Initially, I did this intensive tour of England and, to this day, England is the least of all the English-speaking countries in the world for me. I sold the least number of records there, I never got on the radio,

and it never ever worked. It was painful. But I was with the record guy, and we had been to a radio station, we were driving away, and they played one of my songs. It was the first time I heard myself, as I’m in some car. The song came on and I thought, “Wait a minute, that’s me!” It blew my mind.

Did your life change after the first album came out?

Yeah, my life was constantly changing anyway. I got my own house, but I was gone most of the time. I loved being on the road, and I loved playing, and I was writing. When I was home, I had friends and we had a lot of fun, and then I’d go tour. I would come home and make an album. 1988 to 1993 was pretty much like that.

I am a huge fan of the Laurel Canyon culture of the 1970s and the music movement that was happening in southern California at the time. Was that era of interest to you?

Yeah! That is why I came out to California. I thought that Jackson Browne was going to be there and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, The Eagles, and Fleetwood Mac… they were all going to be playing in the Canyon. But I show up in 1982, and it was all Spandex and big hair, and I thought, “What happened?” It was completely different and very strange, but that was the music I was loving — that was it.

When you arrived, Whisky a Go Go and Troubadour, were those still clubs that people were playing at?

Yes, but it was Guns N’ Roses, Ratt, L.A. Guns.

Big hair and metal guys.

Yep.

How did you get connected with some of the musicians that you had looked up to?

When I was making my first record, the executive producer that Chris sent over to oversee it all, knew Bonnie Raitt. He had produced a couple of her albums. He wanted to introduce me to her and did so just before my first album came out. She was so kind and supportive; she was incredible. I also met Jackson Browne, and Bonnie quickly took me into that 1970s and 1980s bubble of people that were doing benefit work, moving socially forward, and they called me out to do those things. That is where I met everyone else.

Did you get a little starstruck in the early days?

I tried not to show it. I was also observing what they were like because they had what I wanted: what are they doing and how are they managing their careers?

In 1989, Brave and Crazy came out, and peaked at #22, and, in 1992, Never Enough also peaked at #22, but in-between, 1991 was a sad year for you.

Yeah, I lost my dad.

Very much so, he was an incredible human being. He was a high school teacher and a basketball coach. Everyone loved him. He had come from migrant farmers in Missouri, his father had been in World War II and was a horrible alcoholic. He had a metal plate in his head. His mother worked just as hard and there were seven kids. I think there were nine and two of them died. It was the poverty of the 1930s, the Great Depression. He came out of that, and he was good in sports; he had been a swimmer. His high school coach said that he could get a scholarship to college. My dad didn’t know anything about that: he didn’t know what he was going to do with this life. But he went to college, he met my mother, he married, and he graduated with a teaching degree. He was able to go up to Kansas — we didn’t have any family there, but he went up there and he started life. He had the belief that you can come from nothing and become something.

He got to see the first two albums, so he got to see his little girl successful at what she started when she was only seven.

Yeah, that was cool. I remember taking him to Quebec, he had never been up to Canada before. They came up to see me and we had such a wonderful time. I played at this big outdoor concert with thousands of people, it was fun to have him see me play on that level.

In 1993, you released the album that would catapult your career and fame, Yes I Am . It was a huge album for you. It had numerous radio hits, and it seemed like you were everywhere. That must’ve been a bit overwhelming.