18 minute read

Dino Days

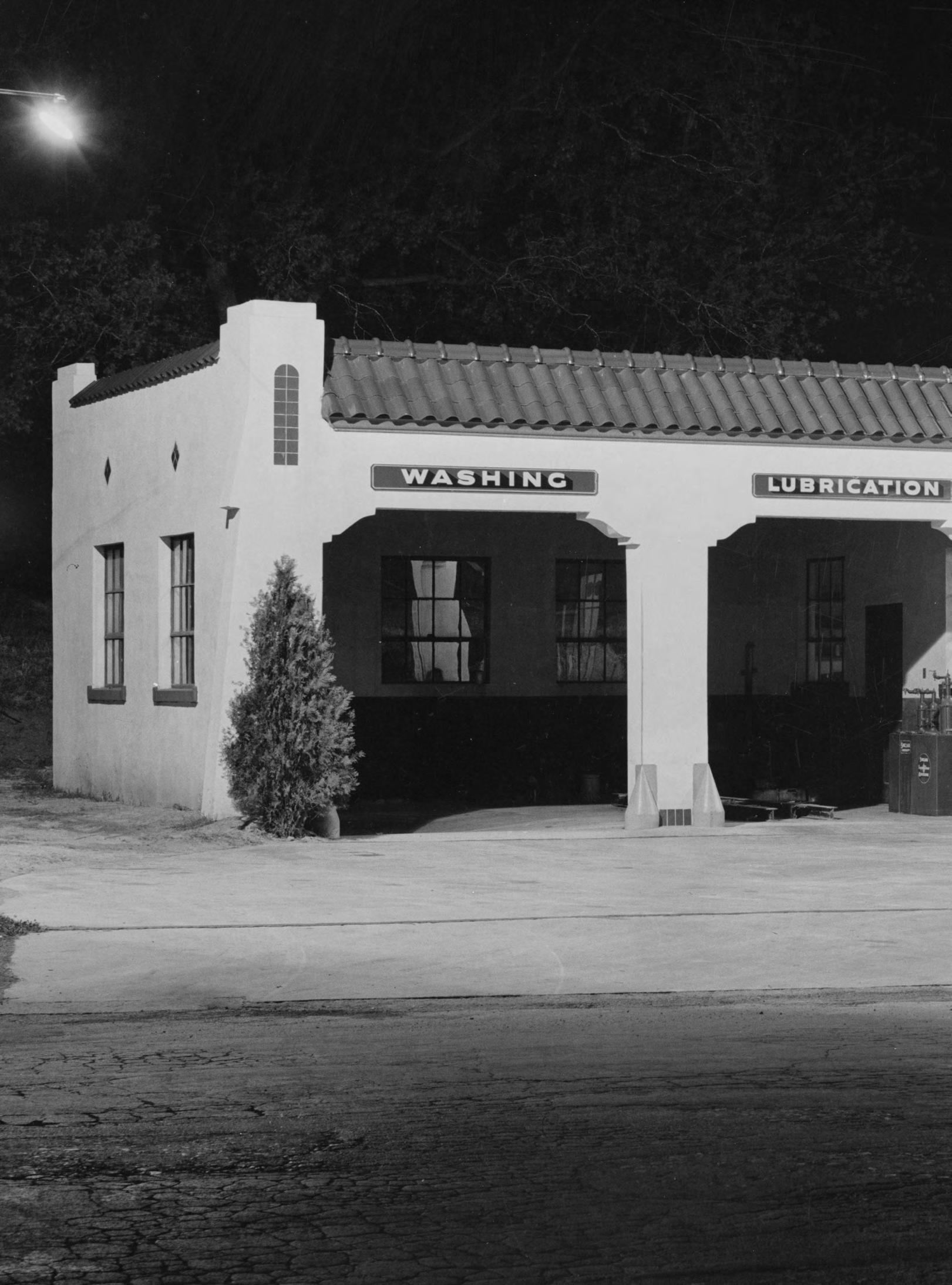

By Richard Ratay Opening photograph by Lee Russell

DINO DAYS

Advertisement

The ad men were stuck. Tasked with coming up with a splashy marketing idea to promote a new line of automobile lubricants, they stared blankly at each other.

What would people find remotely interesting about petroleum products, they wondered? Oil was slippery. Messy.

Mostly, it was noticed only when it wasn’t there—when metal parts began grinding or engines seized.

The writers kept going. Where did crude oil come from anyway? Deep underground. Usually found in vast pools.

Ancient oceans, really. Formed millions of years ago. Way back before humans. Back in the days of… dinosaurs!

BAM! Lightning had struck. The creative team went to work. They mocked up ads, labels, placards, posters. Each featured one of a dozen different dinosaurs—all promoting the products of Sinclair Motor Oils.

The campaign was a sensation. People loved the striking illustrations of the ancient reptiles. For whatever reason, they responded to one in particular—the brontosaurus.

Recognizing this, Sinclair Oil executives focused their future promotions on the hulking long-necked beast. They even gave their Mesozoic megastar a name— “Dino” (pronounced

DYE-no)—and registered him as a trademark in 1932.

Depicted realistically, as a smiling cartoon, or as a simple green silhouette in the company logo, Dino would go on to become one of the most beloved icons of American road travel. And Sinclair would grow into one of the most recognized names along the nation’s highways.

But how did it all begin? And how did Sinclair rise to such lofty status? Let’s drill down a little deeper.

Harry Hits the Jackpot

If Harry Ford Sinclair had simply listened to his father, that would have been the end of it. The elder Sinclair had a simple plan for his son—become a pharmacist, take over the family drugstore, start a family of his own, and embrace a quiet existence in Independence, Kansas. But Harry’s ambitions were far too big for his small town—or for such an ordinary life. He wanted more.

Despite his yearnings, young Harry gave his father’s plan a try. In 1897, he graduated from pharmacy school and returned home to assume ownership of the family business. But Harry couldn’t fight his own nature. Driven by the soaring popularity of newfangled contraptions called “automobiles,” America was in the middle of an oil boom—and Harry happened to live right in the heart of oil country. Hoping to strike it rich, he went all in on a chancy drilling scheme—and promptly lost everything, including his father’s drugstore.

But Harry was far from done with the oil business. He found work selling lumber to construct oil derricks, while also buying and selling oil leases—agreements allowing drilling on private property—on the side. Harry learned he had a knack for picking winners—and so did a host of wealthy backers, including Chicago meatpacker J. M. Cudahy, and Prairie Oil Company president James F. O’Neill. The investors rolled over their profits from one of Harry’s lucrative ventures to the next, building fortunes for all.

“Harry fell into the industry at the right time, and he was smart,” said petroleum industry historian Wayne Henderson. “He got good at the game—and won.”

In 1905, Harry hit his biggest jackpot when he purchased a stake in a drilling operation in northeast Oklahoma. The “Glenn Pool” turned out to be a historic producer, paying out more money than the California gold rush and the Colorado silver rush combined. Almost overnight, Harry became a millionaire. By 1907, at age 31, he was the richest man in Kansas.

The Road to the Top

For Harry, the sudden windfall was simply seed money. In 1909, he established Commercial National Bank in Tulsa, Oklahoma, for the express purpose of serving the country’s leading oil producers. Among the bank’s first clients were Prairie Gas and Oil, a subsidiary of J.D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, and Texaco. Harry made millions. What’s more, the bank helped establish Tulsa as “The Oil Capital of the World.”

Still, it would be years before Harry established Sinclair Oil. That time would finally come in 1916, when Harry combined several smaller operations into a single company. As always, his timing was masterful. Europe was at war, spurring long-term demand for fuel for fighting abroad. Meanwhile, here at home, Americans were clamoring to buy Henry Ford’s affordable Model T. The future of fossil fuels was assured. However, the industry also faced a temporary issue—oil was being overproduced. As oil prices plummeted, smaller cash-strapped operations went bust. Harry aggressively snapped up as many as he could.

“Harry had resources, pipelines, access to refineries, transportation,” explained Henderson. “He was able to put all the pieces together.”

During this period, Sinclair also became a familiar and trusted name for American motorists. In 1922, Sinclair introduced the first modern service station. Beyond dispensing gasoline and oil, Sinclair stations offered oil changes, greasing, tire repairs, washes, free air and minor mechanical repairs. They also sold tires, batteries, and other automotive necessities.

“The stations were clean and bright, and a uniformed attendant would pump your gas, then check your oil and clean the windows,” said Robert Tate, a retired historian of the Automobile History Collection. “Motorists never had to get out of their cars.”

If they did, it was likely to take advantage of another Sinclair innovation, one most appreciated by traveling families—the first service station restrooms offered for customers.

However, Sinclair would hit a pothole on its journey to the top. In 1921, Harry was implicated in the infamous Teapot Dome Scandal, in which several major oil companies were accused of bribing government officials to win no-bid contracts. Although Harry was acquitted of the bribery charge, he was convicted of lesser offenses. In 1929, he served six months in the House of Detention in Washington, D.C.

Sinclair Oil station in Nevada.

“Harry emerged from confinement in classic Harry fashion,” noted Steve Gerkin, author of the The Hidden History of Tulsa. “He strutted down the steps of the federal detention center sporting an expensive suit, fedora, and his signature swagger, shouting to the mob of reporters, ‘I cannot be contrite for sins I did not commit. I was railroaded!’”

Almost immediately following his release, Harry was confronted with another challenge—the Great Depression. Like most companies, Sinclair was hit hard by the tumultuous times. But Harry’s skillful maneuvering set his company up for success, even as other oil producers faltered. As he’d done years before, Harry seized the opportunity to buy still more troubled operations. In 1932, he even acquired Rockefeller’s Prairie Oil and Gas company—and with it, the nation’s largest pipeline system.

Sinclair had become a major force in the American petroleum industry. Next, the company was ready to take its place on the world’s stage.

Dino Becomes a Big Draw

With Chicago set to host the World’s Fair in 1933, Sinclair had the chance to introduce itself to visitors from around the planet, an opportunity the company took full advantage of. It also had the perfect gimmick—the company’s already successful dinosaur concept was tailor-made for making a big impression.

Sinclair decided to sponsor a large exhibit entirely dedicated to the enthralling giants of the prehistoric past. The centerpiece was a full-sized, two-ton replica of a brontosaurus. Designed by Hollywood effects artist P.G. Alen, the monstrous model was even capable of raising and lowering its head to “chew” the surrounding vegetation.

“Fairgoers loved these types of immersive exhibits,” said Robert Rydell, author of several books about the history of the World’s Fair. “Sinclair found a very effective way to teach people about the origins and processing of fossil fuels, while also promoting its products.”

To capitalize on the exhibit’s popularity, Sinclair produced rubber miniatures of Dino the Brontosaurus for distribution at its service stations. By 1959, Dino had become so tied to Sinclair, that the company incorporated the gentle giant into its logo.

In 1964, when the World’s Fair returned to America— this time to New York—Sinclair hoped to build on its earlier success with an even more elaborate display. The company commissioned the creation of nine different lifesized animatronic dinosaurs, a project requiring a team of paleontologists, engineers, and robotics experts. It took three years to assemble. Once completed, the beguiling beasts were transported to Sinclair’s exhibit at the Fair—dubbed “Dinoland”—on the deck of a giant barge which was floated 125 miles down the Hudson River and around Manhattan, thrilling an awestruck public.

A year earlier, a 60-foot vinyl inflatable Dino had already stalked the streets of New York in Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. Dino would remain a highlight of the event until being retired in 1977. During this period, pony-sized fiberglass Dinos began popping up at Sinclair service stations everywhere, offering traveling families fun, exciting photo ops.

“Dino cemented Sinclair’s place in history,” said Henderson. “He’s memorable. Likable. I still give my own grandkids little inflatable Dinos as gifts.”

By all appearances, Dino and Sinclair seemed to have conquered America.

The End of an Era

Sadly, Harry Sinclair wouldn’t live to see his company’s heydays of the 1960s. After relinquishing control of Sinclair in 1949, Harry retired to his palatial home in Pasadena, California, where he passed away seven years later. He was 80 years old.

Harry Sinclair.

“For me, Harry Sinclair was one of those incredibly successful businessmen who always looked for the next mountain to conquer,” noted Gerkin. “Despite all that he accomplished, I bet he felt unsatisfied that he ran out of time to scale all of the peaks on his horizon.”

Though Harry and wife Elizabeth had two children, Virginia and Harry Jr., neither wished to follow in their father’s footsteps. After declining a purchase offer from a suitor outside the oil industry, Sinclair reached out to the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO). In 1969, the two companies came together in what was at the time the largest merger in the history of the oil industry.

However, there was a catch.

For the deal to go through, the U.S. Justice Department required the newly formed version of ARCO to sell off substantial assets. These included all the company’s service stations located west of the Mississippi River—and its rights to the name “Sinclair Oil Corporation.” As a result, the Sinclair brand would live on, but under new ownership and only west of the Mississippi—including along the celebrated Route 66. Sinclair service stations in the eastern United States would be re-branded as ARCO and other brands.

As had happened with the real dinosaurs, Dino and the Sinclair name disappeared almost overnight in nearly half the country.

Sinclair Adds to its Holdings

For a brief period, Sinclair lumbered along under the direction of the Pan American Sulfur Company (PASCO). But in 1976, the company would change hands once again. It would seem like history was repeating itself. The new owner was a man every bit Harry’s equal in terms of vision and business savvy. And just like Harry, his story was one of self-made success.

Robert “Earl” Holding learned the value of hard work early on. When his parents lost everything in the stock market crash of 1929, young Earl helped his family survive the ensuing Depression years by doing odd jobs for 15 cents an hour. After serving in World War II, Holding returned home to Salt Lake City and married his college sweetheart, Carol.

Together, the young couple scraped together enough money to purchase a stake in a service station in Little America, Wyoming, which Earl also managed. Rolling up his sleeves, Holding turned one service station into several. Soon, the “Little America” chain of service stations was among the most successful in the nation. It also became Sinclair Oil’s biggest customer.

Holding had long kept an eye on Sinclair. He’d even attempted to buy the company when the ARCO deal was being negotiated. When Sinclair became available again in 1976, Holding jumped at his chance. It wasn’t the best of timing. America was in the middle of an oil crisis. The economy was on the rocks. Refinery workers across the industry were unhappy. Not long after Holding assumed control, they’d walk out on strike.

As always, Holding got right down to work. In 1980, he personally met with union leadership to negotiate a fair deal. Employees came away from the talks so impressed with Holding’s integrity, they even agreed to de-unionize. Next, in a move that would have made Harry Sinclair proud, Holding boldly purchased a major refinery in Tulsa, Oklahoma, that had closed amid the turmoil. Holding also refocused Sinclair on finding new sources of natural gas and crude oil, not only to supply the company’s own refineries, but to sell at a profit. It proved to be a prescient strategy.

Along the way, Holding earned the respect of the industry—and those who worked for him. “He had very high expectations,” recalled Mark Peterson, Sinclair Vice President of Transportation. “But at the end of the day, you wanted to come back and work for him some more.”

By all accounts, Holding treated his employees like family. In a way, they were. Under Holding’s 30-year tenure, Sinclair grew into one of America’s largest family-owned businesses, with assets including multiple hospitality properties, a luxury ski resort, and even a cattle ranch.

Holding would pass away in 2013 at age 86 in Salt Lake City, where Sinclair maintains its headquarters.

The Legacy Lives On

Harry Sinclair built his company into a phenomenon. Earl Holding guided Sinclair through its most challenging times, making sure its legacy would endure.

Indeed, Sinclair and Dino still stand tall among the legends of American road travel. Animation studio PIXAR paid homage to them both in Toy Story and later in its popular Cars movies, which feature characters from the fictional “Dinoco” oil company—a thinly disguised parody of Sinclair. Vintage Sinclair collectibles, especially those featuring dinosaurs, remain favorites of collectors of Americana, and Route 66 memorabilia. More poignantly, in 2015 Dino made his triumphant return to the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, ushering in the festivities to celebrate Sinclair’s centennial anniversary the following year.

Today, Sinclair continues to offer an inviting presence along America’s highways—at least those that run west of the Mississippi. Road-weary travelers in need of a fill-up or snack can still pull over at any of 1,600 Sinclair-branded stations.

And somewhere near the entrance to each one, a proud Dino still waits to greet guests on every visit.

THE TINIEST TARGET

At 6,192 square miles, Brewster County, Texas is the largest county by size, but also the most desolate, in the state. The towns are small, the roads dusty and deserted, and the desert seemingly endless. But it’s here, of all places, that one of those remote towns was able to bring itself into the limelight.

Marathon, Texas, was originally a ranching town that sat along the Galveston, Harrisburg, and San Antonio railroad. Today, it’s home to about 500 people and the darkest night skies in the lower 48 states. The only major road connecting those in Marathon to any other place is Route 90, the barren highway stretching from Texas to Florida, often called the Route 66 of the South. Along this route, about halfway between Marathon and the county seat of Alpine, sat a forlorn little cinderblock building, a railway switching station from the days of the railroad. It blended in with the barren landscape surrounding it, barely interrupting the rugged beauty of the Glass Mountains in the distance. However, one day the little building got a makeover that changed the area’s dynamic forever. One night in 2016, someone went to the tiny cinderblock building and decked it out with the iconic red bullseye logo of the mega store, Target. From then on, that once small nondescript building became known as the world’s smallest Target.

“It was a joke that went viral,” said Robert Alvarez, the executive director of the Brewster County Tourism Board. “We all fell in love with it. When it started gaining traction on social media, people from out of town would start calling us, asking questions about it.”

Visitors from all around the country would make their way into the middle of nowhere in Texas to take pictures of the little building to post on their social media, often with cheeky captions attached. Many visitors would take the opportunity to help clean up the little abandoned station. One family would make a regular trip to visit and spend an afternoon picnicking there.

While the artist of the tiny Target is unknown, and no one has ever come forward to claim its creation, it’s commonly accepted that it was intended to be a response to nearby Prada Marfa — an equally quirky and unexpected art installation that rises out of the endless Texas desert as a mini-Prada store. Located about forty miles outside of the town of Marfa, Texas, the installation has gained worldwide attention, and perhaps gave birth to the tiny Target. “From the tourism side, the Target was like it was giving a thumbs up to Marathon,” Alvarez said. “We’re more Target people than Prada people. We embraced the heck out of it because it gave us attention like what the Prada does, but it’s more representative of the town and the area. We don’t need the luxury stuff. Target’s more our speed.” However, as the joke got bigger, to the point that someone even brought a Target shopping cart to sit somewhat ominously outside the building, the landowner began to worry about the safety of the many visitors. In December of 2020, he had the building bulldozed. Nothing remains of the building but a pile of bricks on the side of the road, some still painted a bright Target red.

“There were just too many risks for him,” said Alvarez. “There were bricks missing and beehives inside, and it was just becoming too dangerous as more people were coming to visit. He didn’t want to take on the responsibility if someone got hurt, and thought it was best just to destroy it.”

In response, the Brewster County Tourism Board expressed interest in leasing the land from the owner, but sadly, the structure was destroyed before any agreement could be formed. Partnership would have made the building a true local tourist destination, especially as it sat along old Route 90.

Despite the loss of such a beloved inside joke, the town of Marathon hasn’t let the tiny Target die. Soon after the demolition of the Target, the shopping cart appeared in front of the Marathon Library with a note reading: “May the only Target in 100 mi. R.I.P”. Sometimes, for towns big and small, the biggest attraction is the joy that comes from something small.

“In telling the story of his African family’s journey on

Route 66, Brennen Matthews has made an important contribution to the legacy of the highway. He offers both a new voice and a new look at the Mother Road.”

—from the foreword by Michael Wallis, New York Times bestselling author of Route 66: The Mother Road

“Hop in and buckle up. Brennen Matthews’s

Miles to Go is a ride you won’t soon forget.”

—Richard Ratay, author of Don’t Make Me Pull Over! An Informal History of the Family Road Trip

“Miles to Go awakens fond memories of my many road trips by car and Greyhound bus along the

—Martin Sheen

“In Miles to Go, we don’t just drive the highway looking out the window. We stop, interact with people, and learn things we were not expecting. . . . This Route 66 journey doesn’t just immerse us in the sights, sounds, and experiences of the road. As guests on the journey, we’re encouraged to think about what it means to live in America and be an American.”

—Bill Thomas, chairman of the Route 66 Road Ahead Partnership

Miles to Go is the story of a family from Africa in search of authentic America along the country’s most famous highway, Route 66. Traveling the scenic byway from Illinois to California, they come across a fascinating assortment of historical landmarks, partake in quirky roadside attractions, and meet more than a few colorful characters.

Brennen Matthews, along with his wife and their son, come face-to-face with real America in all of its strange beauty and complicated history as the family explores what many consider to be the pulse of a nation. Their unique perspective on the Main Street of America develops into a true appreciation for what makes America so special. By joining Matthews and his family on their cross-country adventure, readers not only experience firsthand the sights and sounds of the road, but they are also given the opportunity to reflect on American culture and its varied landscapes. Miles to Go is not just a travel story but a tale of hopes, ambitions, and struggles. It is the record of an America as it once was and one that, in some places, still persists.

Experience America and Route 66 through a lens never seen before.

VISIT AMAZON.COM AND PRE-ORDER A COPY OF MILES TO GO NOW AND JOIN BRENNEN MATTHEWS AND HIS FAMILY AS THEY SET OUT TO DISCOVER AMERICA ALONG HISTORIC ROUTE 66