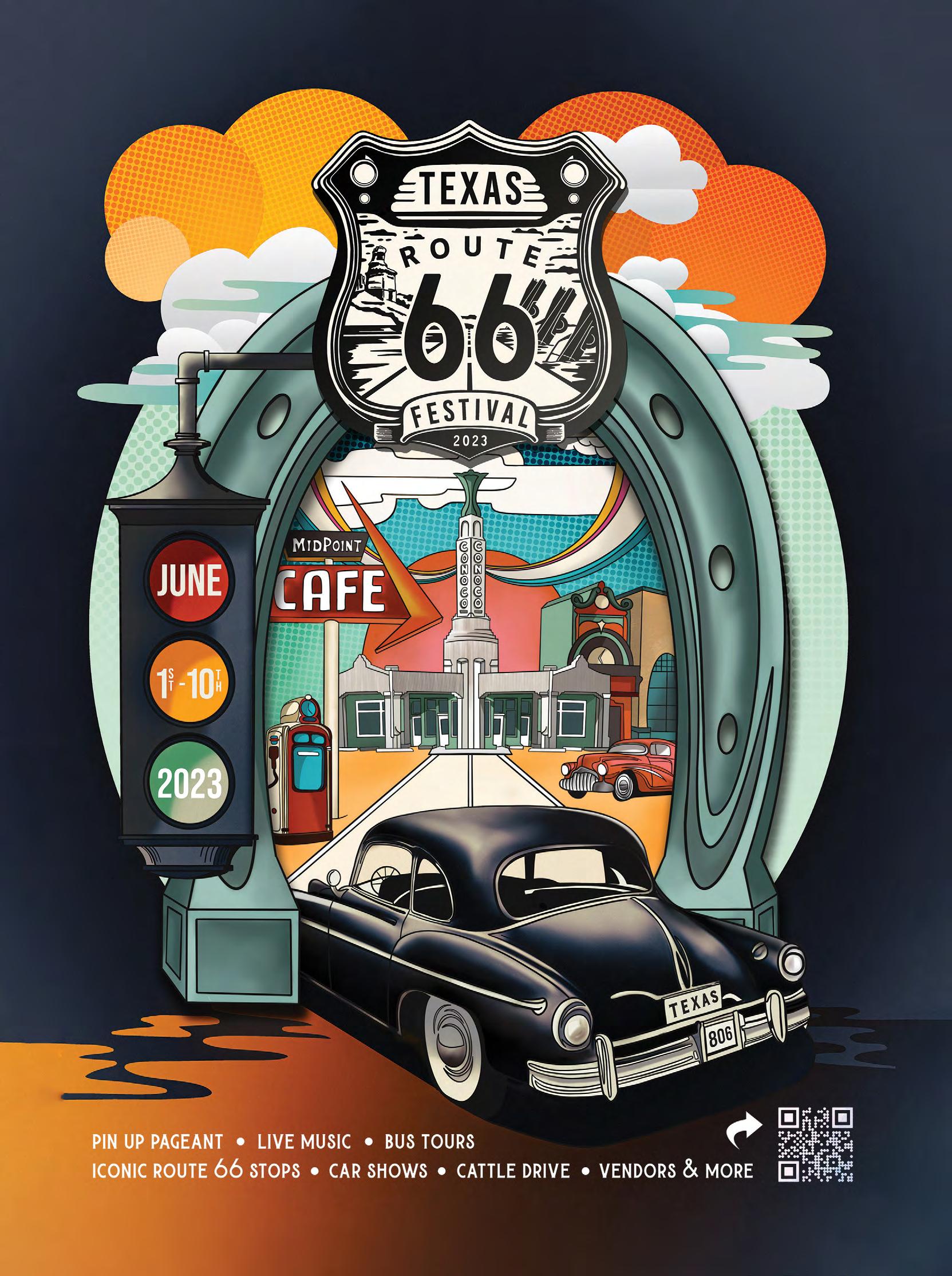

June/July 2023

$7.99

Magazine

AMERICA’S MOST FAMOUS GHOST TOWN

WHERE IN THE WORLD IS HACKBERRY, ARIZONA? KEEPING TULSA QUIRKY

WHERE ROCK & ROLL STILL LIVES PROUD ON 66 +

June/July 2023

$7.99

Magazine

AMERICA’S MOST FAMOUS GHOST TOWN

WHERE IN THE WORLD IS HACKBERRY, ARIZONA? KEEPING TULSA QUIRKY

WHERE ROCK & ROLL STILL LIVES PROUD ON 66 +

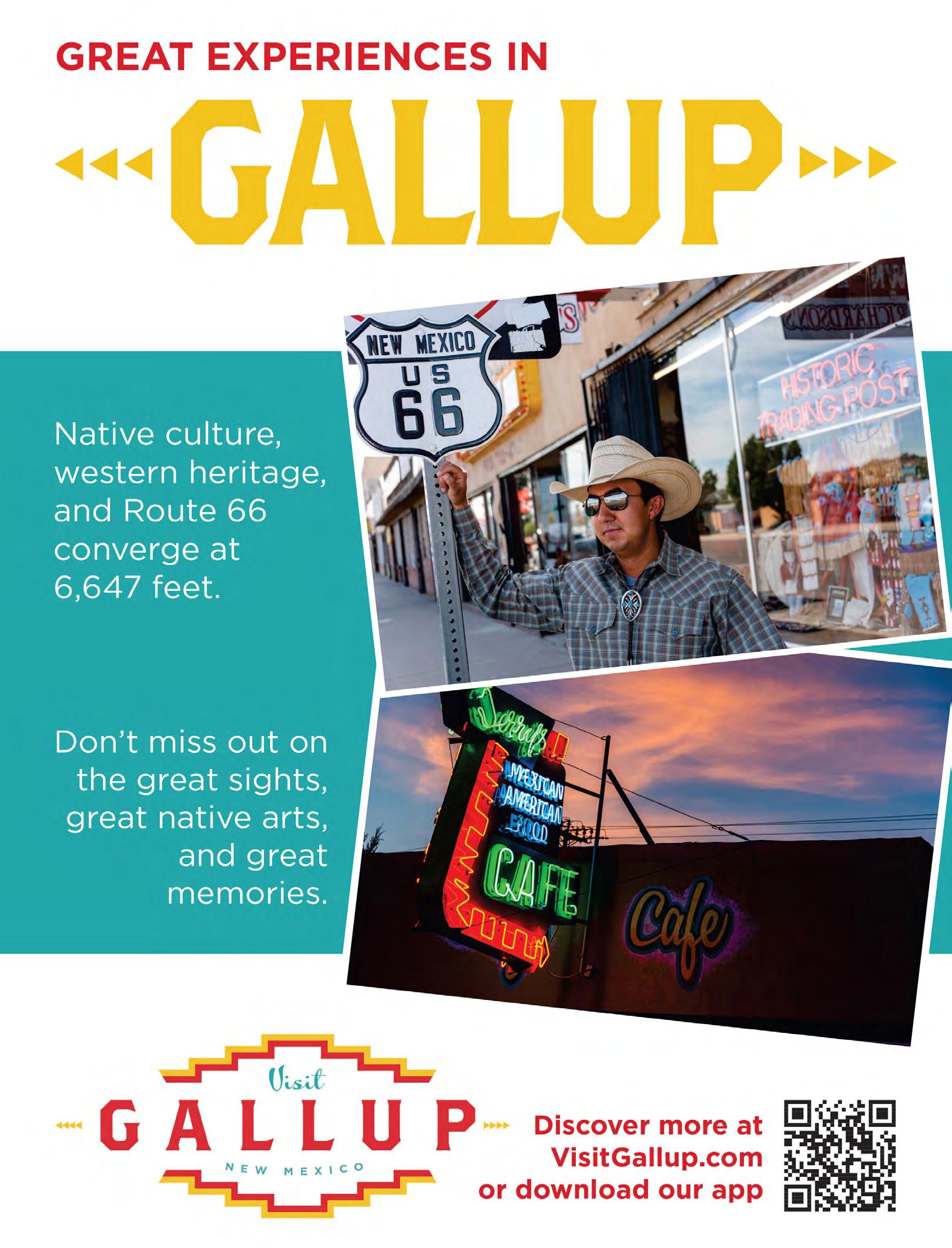

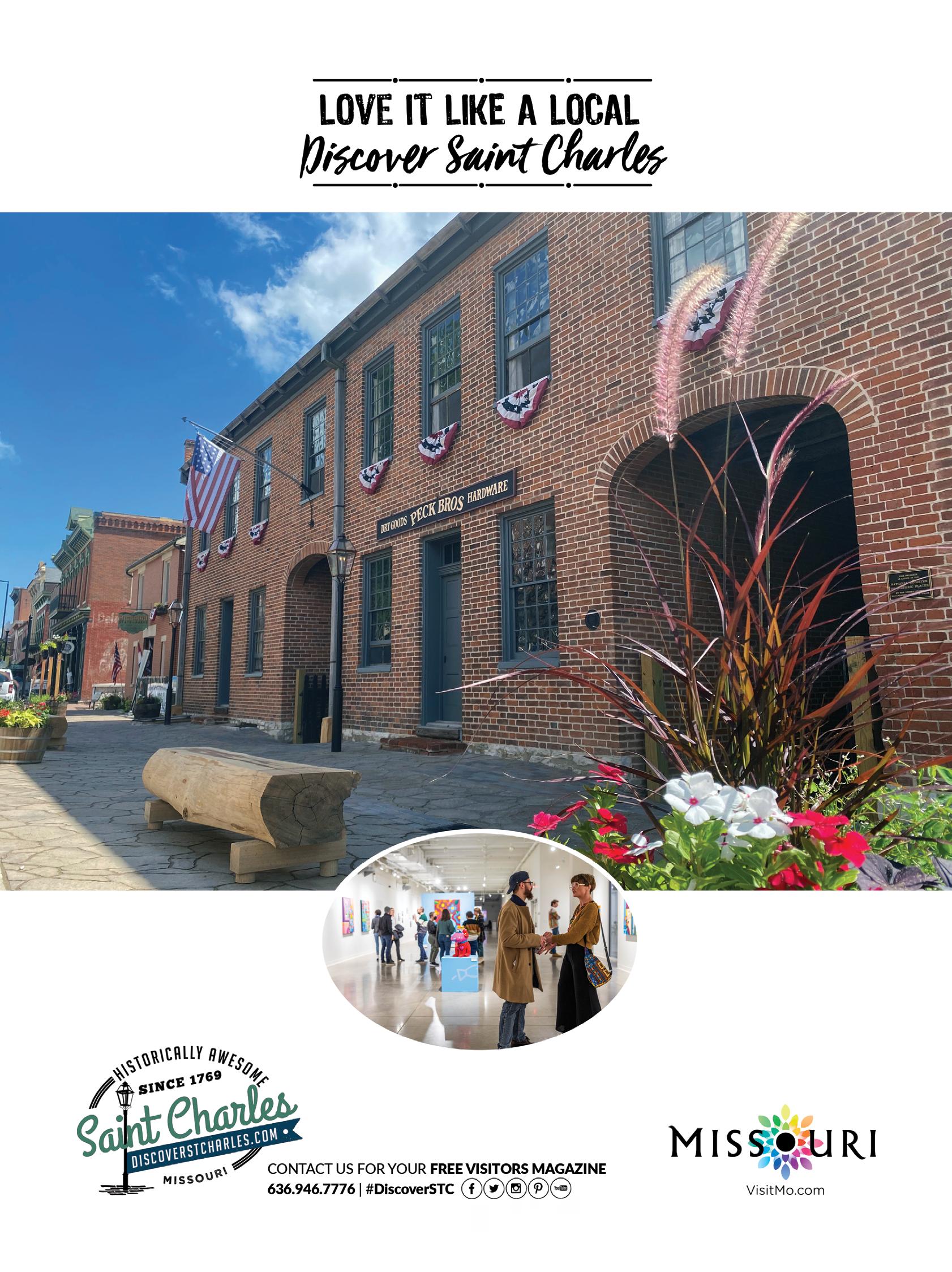

Whether it’s classic cars, old fashioned burgers or a museum that brings history to life, you can relive the glory days of Route 66 in its birthplace. We love our city and know the best places to eat, drink and play. Get your kicks at the Birthplace of Route 66 Festival, August 10–12, 2023.

Here, a tropical conservatory bridges 15 acres of botanical beauty. Homegrown produce shines in homemade courses, where farm to table meets fine dining. Just off Route 66, a rustic lodge welcomes you to wine country. And a transplanted Ferris wheel offers breathtaking views of the Oklahoma River after decades of California dreaming.

The Route 66 East Gateway is located on the north side of E. 11th Street just east of I-44. It has an LED Route 66 shield and lights up by night.

The University of Tulsa campus on historic Route 66 offers pre-statehood roots. TU boasts Division I athletics, manicured gardens, Collegiate Gothic architecture, and more.

A one-of-a-kind 70-feet by 30-feet structure from artist Eric F. Garcia dedicated in 2019. This massive installation draws inspiration from the Dust Bowl-era Depression, as well as the Mother Road’s beacon of hope.

Circle Cinema is Tulsa’s oldeststanding movie theatre that originally opened in 1928 and now operates 365 days a year as the only nonprofit cinema in the area.

Buck Atom is a hard-to-miss 21-foottall space cowboy muffler man who stands outside of Buck Atom’s Cosmic Curios–a shop celebrating the magic of the Mother Road.

This open-air museum educates visitors about Tulsa’s history in the oil, refining, and transportation industries. Pop inside their Visitor’s Center – a replica Phillips 66 Station!

A plaza on Southwest Blvd. and Riverside Dr. featuring bronze statues, a skywalk and pedestrian bridge all honoring the father of Route 66, Cyrus Avery.

The namesake of the Blue Dome Entertainment District, the Blue Dome in downtown Tulsa was once a 1920s-era Gulf Oil station on the original Route 66 path.

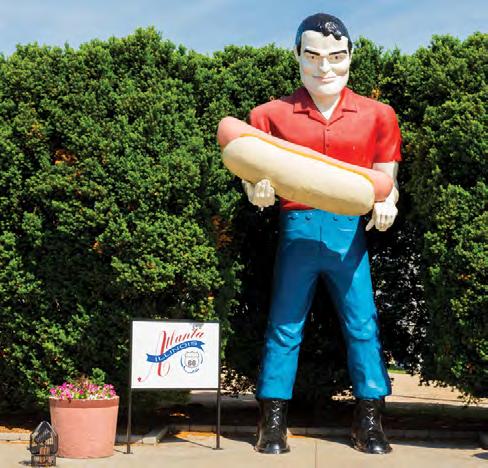

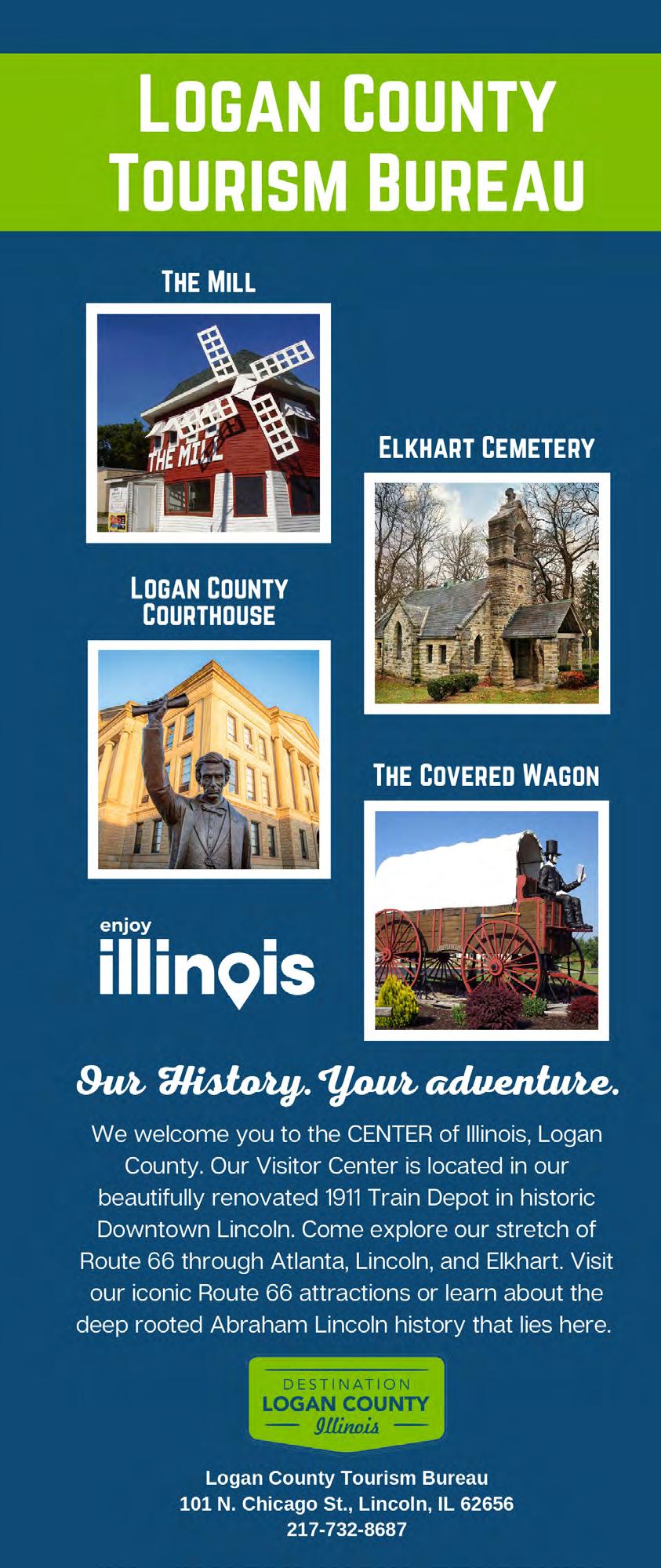

Discover Springfield, Illinois - one of the most iconic stops on historic Route 66. The road comes through our “Living Legends & Landmarks” Explorer Passport with 14 stops to engage all of your senses! Plan your road trip, meet the legends face-to-face, marvel at the landmarks, snap some pics, and create your own Route 66 memories!

Pontiac, Illinois, is a real Route

Few places in St. Louis, Missouri, get as much Mother Road fanfare as Ted Drewes. Show up any night of the week and expect to join a large crowd of hungry, enthusiastic patrons thrilled to experience one of Route 66’s most beloved destinations.

Once owned by Mother Road icon Bob Waldmire, this “middle of nowhere” destination comes up on unsuspecting travelers quite unexpectedly and few fail to stop. This Arizona desert stop has garnered quite the global following but not many know the store’s layered history.

Huey Lewis sang about the heart of Rock & Roll being in Cleveland, but down in Joliet, Illinois, right on the Main Street of America, is a new museum making waves and urging people to take a unique musical journey through the decades of Rock & Roll.

Family-owned businesses have always been an important part of the Mother Road. They make up the backbone for which the spirit of the road has been formed. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, one neon laced restaurant embodies the essence of America’s roadside diner in spades.

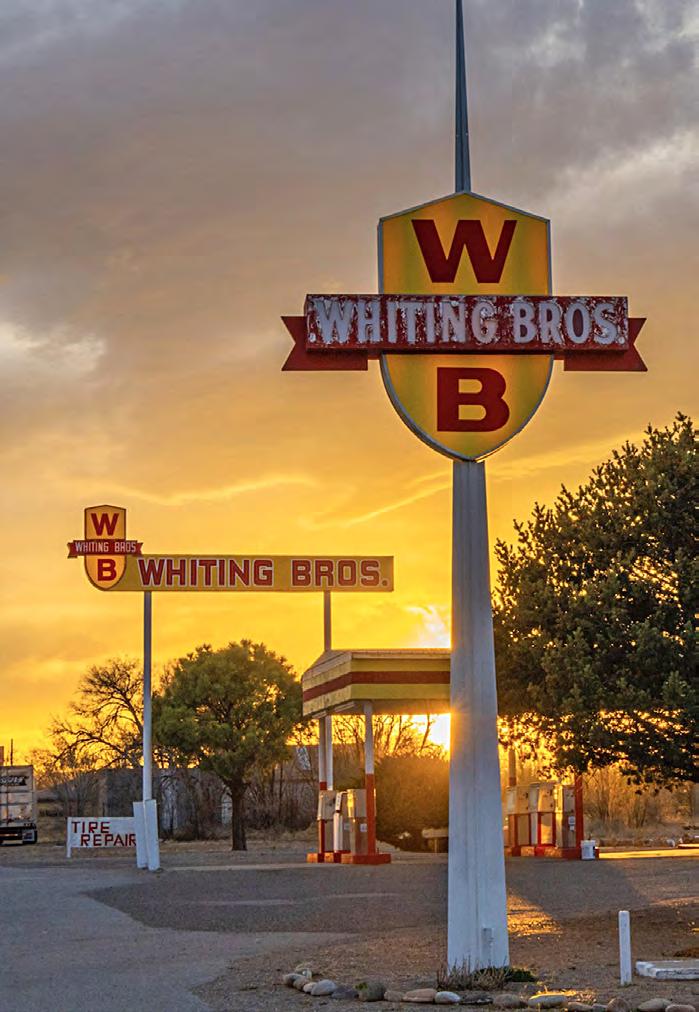

At one point in time, the Whiting Brothers gas station brand ruled the highway. Today, the sole survivor stands in the tiny town of Moriarty, NM. This is its story.

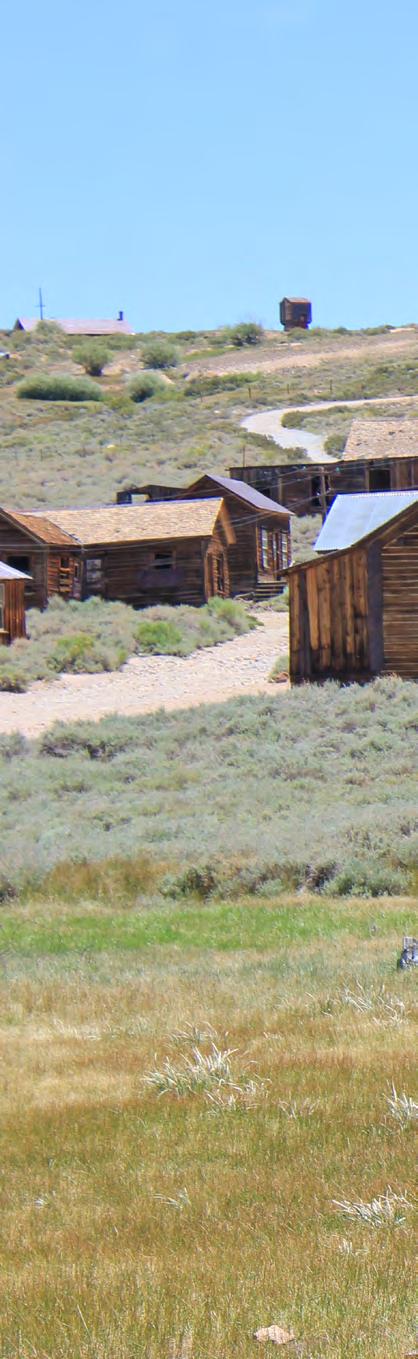

Ghost towns are part and parcel of the Southwest’s empty landscape and road travelers have been keen on discovering and exploring them since their first inception. Up in northern California rests the granddaddy of them all — Bodie — a ghost town truly frozen in time.

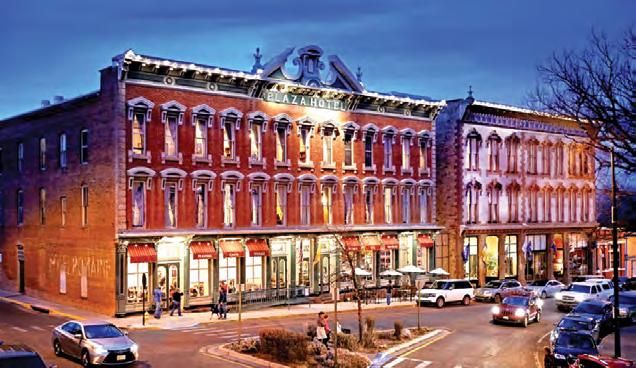

As the first Hilton Hotel outside of Texas, the Hotel Andaluz in Albuquerque, New Mexico has quite the storied past, spanning decades, several owners and some spooky tales thrown in. Truly worth a visit.

Stewart’s Petrified Wood, Holbrook, AZ.

Photograph by David J. SchwartzPics On Route 66.

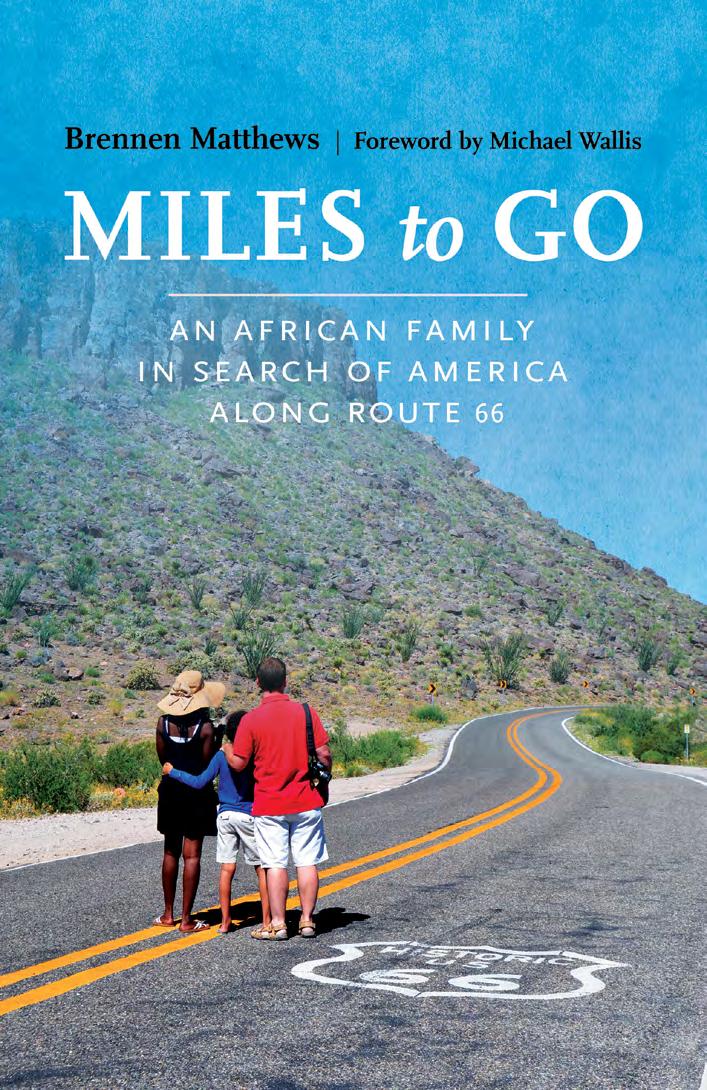

I’ve been reading Andrew McCarthy’s new book, Walking with Sam , about a recent trek that he took along the Camino de Santiago with his eldest son, 19-year-old Sam. The 500-mile walking adventure across one of Spain’s most beloved scenic routes showcases not only the diverse culture and beauty that can be found along “The Way” but also the very ability of such an arduous trip to influence and impact our relationships and our own perspectives and attitude. I worked with McCarthy for the April/May 2023 issue, and we had a wonderful time together but diving into this new book I feel like I understand him better and appreciate his personal journey as a man and a father more.

Yet, what really impacts me when reading this book is the realization that my own road trips with my son Thembi were very likely doing more to shape his young mind and spirit than he ever lets on. I mean, of course I’ve always held firmly to the belief that travel opens minds and expands horizons… blah, blah, blah, but most of us do not stop and really analyse how this is practically happening in our lives and in the personality and very soul of our children. Often, they don’t really show it. “Are you having a good trip?” “Yeah, it’s fun.” “What do you think you’ve enjoyed the most so far?” After they rattle off a short list, we usually feel affirmed and go back to living our own trip. But likely, there is much more going on inside of their hearts and minds than we bother to pay attention to; even they are not aware. It is our responsibility to nurture and cultivate it.

This June we are starting our eleventh trip down the Mother Road. We first discovered the historic highway when Thembi was eight and we had just moved to Canada from Kenya. The road trip was not only enjoyable and eye opening, but it hugely impacted our appreciation for and understanding of America. It broadened our worldview and created space in our minds for more ideas and ways of life. This year, I am especially interested in engaging with my son as he is now 15 and more likely to embrace the journey on his own terms. Regardless, I know that his love of roadside Americana and appreciation for the diversity of American history and personalities along Route 66 is undeniable. I’ve listened over the years as he tries to explain his experiences to his friends, but few seem to care or understand. Most of them have lived a life of airplane travel and resort-based “vacations.” I am grateful that Thembi has a lifelong tapestry of travel that is not only unique, but it has been off the grid, and it continues to make him a fuller, deeper, more passionate young man. Really, is there any better gift that we can give our children?

In this issue, we bring you the story behind some of the most iconic stops along Route 66. The roadside oasis in the Arizona desert of Hackberry General Store has long been a traveler favorite. Motorists out exploring the iconic highway, especially those from Europe, have been placing Hackberry General Store at the top of their must-see list for decades and the quaint, unassuming little shop has developed its own story along the way. Multiple owners, numerous names, and various visions for the store have created an unconventional experience for visitors: sometimes spooky and silent, sometimes energetic and jubilant. This destination has a fascinating tale to tell. If there is one thing that is unique to American travel, it is the ability to visit ghost towns, once bustling settlements that have long gone silent, left to decay in the march of time. And perhaps the most famous and well intact destination is the northern Californian town of Bodie. Many ghost town enthusiasts will have either visited Bodie or have it on their bucket list, but how many know the true and intriguing story behind it?

These and so many other stories fill this special summer issue. As you get out on the road this season, and if you are traveling with your children or grandchildren, slow down and take a moment to soak in the importance of the journey.

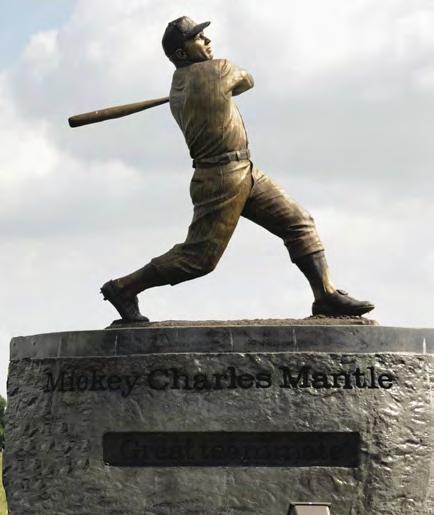

This month, I will be in Tulsa, Oklahoma, for some book signings. Join me on June 24th at Magic City Books and/or June 25th at the AAA Road Fest. I will also be at 21c Museum Hotel in OKC on July 1st for a book signing. Pick up your copy of Miles to Go: An African Family in Search of America Along Route 66 , today and bring it to get signed or grab a copy at any of these venues. I would love to meet you and get an opportunity to talk a little more in-person. So, come and join us as we showcase my new book and celebrate the Great American Road Trip and Route 66 together. Make sure to visit us online daily for news and updates and new stories not found in the magazine and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. And of course, subscribe now and never miss another amazing issue of ROUTE Magazine!

Blessings, Brennen Matthews EditorPUBLISHER

Thin Tread Media

EDITOR

Brennen Matthews

DEPUTY EDITOR

Kate Wambui

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Nick Gerlich

LEAD EDITORIAL PHOTOGRAPHER

David J. Schwartz

LAYOUT AND DESIGN

Tom Heffron

DIGITAL

Matheus Alves

ILLUSTRATOR

Jennifer Mallon

EDITORIAL INTERN

Aaron Garza

Kristy Gillespie

CONTRIBUTORS AND PHOTOGRAPHERS

Chandler O’Leary

Cheryl Eichar Jett

Efren Lopez/Route66Images

Ellen E. Proctor

Greater Arizona Collection

Greg Disch

Jarrod Lopiccolo

Jim Luning

Jimmy Pack Jr.

Joseph L. Roberts

Juankr

Kelli Smith

Linda Doyne

Marianna Civitillo

Mia Goulart

Mitch Brown

Oscar Vasquez

Shannon Driscoll

Editorial submissions should be sent to brennen@routemagazine.us

To subscribe or purchase available back issues visit us at www.routemagazine.us.

Advertising inquiries should be sent to advertising@routemagazine.us or call 905 399 9912.

ROUTE is published six times per year by Thin Tread Media. No part of this publication may be copied or reprinted without the written consent of the Publisher. The views expressed by the contributors are not necessarily those of the Publisher, Editor, or service contractors. Every effort has been made to maintain the accuracy of the information presented in this publication. No responsibility is assumed for errors, changes or omissions. The Publisher does not take any responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts or photography.

21c Oklahoma City is the perfect road trip destination for the curious traveler. Explore our latest multi-media art exhibition, The SuperNatural, indulge in creative cuisine at Mary Eddy’s Dining Room or Pool Bar and Bodega, and make a night of it in one of our stylish and light-filled rooms.

Two worn-down roads run parallel to one another on the edge of Broadwell, Illinois. Surrounded by fields of corn, a motel, and the Lincoln AG Center, there’s a sign that stands tall, and it’s not the ‘Welcome to Broadwell.’ This is the sign of the Pig Hip restaurant, and it, along with a plaque, is all that remains of the classic local diner that fed the people of both Broadwell and tourists driving through Route 66 for decades. But while gone, it has not been forgotten!

Back in 1937, a young Ernest L. Edwards Jr. — Ernie, to those who knew him — bought the Wolf’s Inn and changed the name to Harbor Inn due to the nautical wallpaper that invoked images of anchors and boats. He obtained the funding thanks to a $150 loan from his father, Ernest Sr., a factory worker who believed in the rewarding nature of being a self-made man and didn’t want his son to follow the same career path that he did. Ernie Jr. had plenty of experience working in food service, working in hot dog and popcorn stands at fairs and at Bea’s Ice Cream in much larger Springfield.

And it would not take him long to leave his mark with the famous Pig Hip sandwich, which would eventually, by 1939, become the restaurant’s namesake. As is commonly known by those who visited, Ernie only ever used one of the hips of pigs.

“You only take meat from the left leg because the meat wasn’t as tough as the meat on the right leg. It was because of which leg they stood on a hill or something silly like that,” said John Weiss, Chairman of the Route 66 Association of Illinois Preservation Committee. “Someone came in and said, ‘Give me a slice of that pig hip,’ that they saw hanging in the kitchen, and that’s what gave Ernie the idea to change the name.”

Soon, Ernie Jr. earned some minor celebrity as the owner of the restaurant, gaining the moniker of ‘The Old Coot on Route 66’ after the release of an article in the Chicago Tribune written by Mike Royko, that mentioned

a conversation he had with Ernie about Emil Verban, second baseman for the Chicago Cubs. Royko referred to Ernie Jr. as the ‘Old Coot in the Rocking Chair,’ and Ernie Jr. liked the sound of it so much that if he ever autographed a piece of paper, that’s how he would sign it. Being a self-starter became something of a family trade. While he ran the restaurant, his brother Joe ran their Phillips 66 filling station, and his sister Bonnie operated the Pioneer’s Rest Motel. All three businesses were on the same property, but today, only the latter remains, but not as a functioning motel. And in a true testament to Route 66, Pig Hip stayed open for decades, longer than the average business on Route 66, after the Mother Road was decommissioned. However, by the late 1980s, it had become too overwhelming for Ernie Jr.

“It was just too much work,” said Weiss. “He and his wife Frances, who was a waitress at the restaurant, felt it was time to retire. Business wasn’t nearly as good being on the outskirts of I-55, and you can’t make it strictly on tourism.” So, in 1991, Ernie Jr. closed Pig Hip’s doors as a restaurant and opened them as a museum, where it remained open for seventeen years. That’s until March 5, 2007, when a fire occurred.

“One day, he went to the store, and when he came back, the place was on fire,” said Weiss. “It was in the attic. So, we assume that a squirrel chewed through some wires, and by the time he got back from the store, the fire was already engulfing it, because no one could spot it sooner, and by the time the fire department got there, it was too late to save anything.”

Today, all that remains of the Pig Hip restaurant is the restored road sign, a commemorative plaque on a boulder where the building previously stood, and a few surviving artifacts that reside at The Mill Museum on Route 66 in Lincoln, Illinois. Ernie Edwards passed away in 2012 at age 94, but he left behind a remarkable life and a career at a restaurant that became something of a legend on the historic Mother Road.

It’s March 1907, and John Melville Bayless, an entrepreneur, and businessman in the area, breaks ground in Claremore, Oklahoma. He’s building a home for his family to settle into, and the groundwork for the house is laid in Indian Territory. But in eight months, it will rest in Oklahoma, one month after President Roosevelt issues Presidential Proclamation 780, declaring it the forty-eighth state. The Victorian, Painted Lady-style mansion will stand three stories tall, be framed with four towers, and even have woodwork shipped from the St. Louis World’s Fair. It’s the Belvidere Mansion, and with time, it will become known as the Belle of Rogers County.

During his time in Claremore, Bayless was sure to leave his mark and show his worth. Having moved his family from Cassville, Missouri, to Sulphur, Oklahoma, and finally to Claremore in 1900, Bayless saw financial opportunities in the Indian Territories due to the presence of the railroads.

“He was a banker from over in Missouri; he also acquired the right of way for railroads,” said John Cary, volunteer director of the Belvidere Mansion. “If a town didn’t have a railroad, but it needed a short spur [line] built, he would acquire the right of way, and if he thought it was a good deal, he’d basically hang onto part ownership of it in exchange for his work acquiring the right of way. Otherwise, he would just ask for payment. But anything real estate related, or anything bank related, he was involved in.”

He chose Claremore over Tulsa because it had two railroads instead of Tulsa’s one.

Upon arriving in Claremore, he already had the construction of the Cassville & Western and the Arkansas & Oklahoma Railroads under his belt. Along with the development of Belvidere Mansion, which cost him somewhere between $25,000 and $50,000, or roughly $800,000 to $1.5 million when adjusted for inflation, he would also go on to build the Windsor Opera House, the Claremore Athletic Association, and the Sequoyah Hotel, which housed the Bank of Claremore. Out of all of these structures, the mansion is the only one to remain fully intact today. The tragic irony is that Bayless wouldn’t live to see his home completed. In June 1907, he suffered a fatal Appendicitis attack and died

prematurely. His wife, Mary Melissa, and their seven children would, however, go on to live in the mansion until 1919. By 1926, the mansion would house new residents when the Bell family purchased it. The 9,000-square-foot building was repurposed into a complex with twelve apartments on the second and third floors. However, when most of the family who owned it passed away, and the rent from the tenants wasn’t enough to keep it going, the mansion fell into disrepair in the 1980s and by the 1990s, it was all but deserted. Fortunately, in 1991, the Rogers County Historical Society, led by President Wanda Moore, purchased the property and began restorations.

“She saw the building and decided that it was a building that needed to be saved. She was a local dynamo who was able to find people who were interested in helping her,” said Cary. “We had a local pediatrician who headed up the effort and cosigned a mortgage to borrow money to buy it for $75,000. It was in very poor condition. We don’t get any federal, state, or local funds. All of the money we’ve been putting into the building [is from] donations and fundraising; some people have even left money to the Belvidere Historical Society in their wills.”

The Belvidere Mansion — aptly named “Belvedere” meaning a building with a view — currently rests on the corner of 4th Street and Chickasaw Avenue in historic Claremore and is safely listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Because of its age, maintenance is a constant priority. Upkeep and maintenance gets paid thanks to donations from people around the community, especially those who donate following the daily free tours around the glamorous home. The third-floor ballroom is rented out monthly for special events like proms and weddings, and the first floor is rented out to a restaurant called The Pink House, which has been voted “Best Place to Have Lunch in Claremore’’ by the Claremore Daily Progress.

John Melville Bayless did not get to enjoy the fruit of his vision, and his family only resided at the home for a little more than a decade, but sometimes, if we are lucky, our work and dreams live on beyond us. Over a century later, the mansion continues to overlook the city of Claremore, and is a reminder of one industrious man and his short time in Oklahoma.

Photographs by David J. Schwartz - Pics On Route 66

om-and-pop businesses were once the backbone of the communities dotted along American highways. Most of them opened and closed with the cycle of the owners’ lives or the popularity of the throughway along which they stood. A few survived threats like generational change, highway bypasses, chain venues popping up next door, and the changing tastes of the motoring public to become legendary must-stops.

And so, it’s rare — but not unheard of — when a momand-pop business, begun on a shoestring and intended simply as a means to eke out a living, endures through multiple generations and rises to a level of popularity that makes it a given, the absolute go-to place, after baseball games, the theater, or a visit to the zoo. It’s even more uncommon when that modest family business rises to the iconic status of being mentioned in the same breath as the city’s legendary baseball team or outdoor theater.

But so it is in the City of St. Louis. Cardinals baseball, The Muny in Forest Park, the Gateway Arch, Ted Drewes. Yes, Ted Drewes Frozen Custard is one of those places that visitors and tourists make a beeline for. Its iconic status is known well beyond St. Louis’ environs, and it’s most definitely on the Route 66 bucket list. “The one thing everybody can agree on is that they love Ted Drewes,” said Joe Sonderman, Route 66 author and St. Louis radio personality. “You go to Cardinals games, and every time the Cubs [play] here, you can go back to Ted Drewes and there’ll be the Cubs fans with their blue caps and the Cardinals fans with their red caps standing in line at Ted Drewes, and they can share the experience. It’s the great melting pot — all ages, all demographics, all lifestyles. Everybody’s welcome at Ted Drewes.”

Truly, the Ted Drewes story is a unique one, involving not just tasty custard and a catchy slogan (“it really is good guys...and gals”), but professional tennis, carnival stands, Christmas trees from Nova Scotia, and three generations of a St. Louis family. This tale is one for the history books, and St. Louisans love to tell the story.

The Ted Drewes story began in 1898, when Ted R. Drewes (Sr.) was born in Hannibal, Missouri, to Reverend Christopher and Laura (Motz) Drewes. In 1905, Reverend Drewes took a call to Bethany Lutheran Church, a St. Louis congregation, and the family, including little Ted and his older brother Walter and sister Laura, moved to the big city. The Reverend became a well-known pastor and leader in the Missouri Synod Lutheran organization. But his son, Ted R. Drewes (Sr.), became famous for his winning tennis skills. The boy began playing tennis at age 11, often playing on the city’s Forest Park courts, and he became a well-known player, winning the Municipal Association title fifteen times (between 1916-1935); four consecutive National Public Parks

Mchampionships (beginning in 1924); and The Muny title twelve times (1924-1935). As a young adult, when he wasn’t playing in St. Louis, he played in Florida during the winters. But when he was in St. Louis, he alternately taught tennis at Concordia seminary, worked as a newspaper sports reporter for the St. Louis Star, and was employed as a clerk by Wagner Electric. In the early 1920s, between one job or another, he married Mildred Schaefer, who, like Ted, was from a German immigrant family.

During one of his trips to Florida, Ted was introduced by a friend to the idea of making money from the increasing popularity of frozen custard stands. Ted bought a custard-making machine and a recipe, and in between tennis tournaments, earned income traveling with a carnival, setting up a small stand, and selling frozen custard. In 1929, he opened up his first fixed location custard stand at St. Petersburg, Florida.

The next year, he opened what would be the first of several St. Louis locations, on Natural Bridge Road. There, his stand was on a 50-foot lot, sandwiched in between Sam the Watermelon Man and Balsano’s Shell Station. In the early ‘30s, Ted opened a second location at 4224 S. Grand Boulevard. Meanwhile, his wife Mildred let Ted know that it was time for him to quit “commuting” between St. Louis and Florida, what with two St. Louis business locations and also four children.

Ted apparently paid attention to Mildred’s admonition, and in 1941, the Drewes family would make what many would argue as the most propitious move of their business. The St. Louis Hills neighborhood, created by developer Cyrus Crane Willmore, was growing rapidly, and through it came U.S. Highway 66 and the promise of many business opportunities. So, the Drewes family fortuitously took advantage of that promise with a new location on Chippewa Street.

Many years later, in a 2019 interview, Ted’s son, Ted Drewes Jr., shared his memory of his mother excitedly telling him that their new store location would be on the famous Route 66. “I knew it was special and I never forgot that,” Ted Jr. said. There, in St. Louis Hills, the new Ted Drewes Frozen Custard location at 6726 Chippewa would grow to be the most important and famous one in the group.

Ted Drewes Jr. grew up knowing how to work hard. He once said in an interview that his father got him his first job picking up trash in the neighborhood. As he grew up, young Ted had a role model. Ted Sr. consistently worked additional jobs during the winter months to pay the bills when the custard stand was closed — he managed an archery range, he ran a combination swimming pool and roller rink, and sold pastries.

Ted Jr. got married in 1950 to his sweetheart, Dottie, one of the Ted Drewes carhops, and started a family of his own, while Ted Sr. thought about retiring — but kept on working. Mulling over the family’s assortment of additional jobs, Ted Jr. hit upon the idea of selling Christmas trees from their custard stand lot to bring in income during the custard business off-season.

“So, Ted Jr. said, ‘Dad, we got to get an income for the wintertime.’ They did all kinds of things — Fuller Brush salesman, door-to-door sales, owned a roller rink — but they really struggled in the winner because there was no income,” explained Travis Dillon, son-in-law of Ted Drewes Jr. and the third generation to operate the frozen custard stand. “So, he convinced his father to get some Christmas trees from Nova Scotia. They actually went to Nova Scotia and then shipped them down by railroad. And those trees started selling — they were the most beautiful Canadian Balsam Firs. [Most] Christmas trees at that time were basically domestically grown — Scotch Pines grown in the Midwest — and they look nice. But boy, when you saw these beautiful Balsam Firs from Canada — we were the only place selling [them] in 1956.”

The 1950s saw two other changes to the business. Due to crime and declining sales, the family made the decision to close the location on Natural Bridge Road. And, more importantly, the famous frozen treat known as the

“Concrete” was born! The way the story goes, a boy in the neighborhood kept after Ted Jr. to make a thicker shake — as thick as possible. Ted Jr. took on the challenge and made a shake without the milk. Presenting a thick upside-down shake to the boy who started it all, the youth said that it was “like concrete” and the name stuck.

Another change that Ted Jr. made was to begin advertising in St. Louis media. With his upside-down Concrete to show how thick it was, to his slogan — “it really is good guys — and gals,” Ted Jr. became a beloved spokesperson on St. Louis TV channels. Between the Christmas tree sales in the winter and the catchy advertising, Ted Jr. is credited with growing the business into a St. Louis icon and making it a viable long-term family business. By about 1980, it’s clear from newspaper articles that Ted Drewes Frozen Custard had really arrived and was an accepted element of St. Louis culture.

“If it wasn’t for Ted Jr., my father-in-law, I’m not sure what would have happened, because he was the instigator of starting to advertise the frozen custard,” said Dillon. “Before that, the business was just barely getting by, because there’s so much competition. He really had to push him [Ted Sr.] to start advertising. But then Ted Jr. became such a fantastic, outgoing spokesperson for the business.”

However, when Ted Sr. died at the age of 70 in 1968, he was still known more for tennis than for frozen custard.

A newspaper article began, “Theodore R. (Ted) Drewes, one of the greatest tennis players developed in St. Louis, died early today...” After enumerating his tennis awards and honors in several paragraphs, the article stated, “Drewes had a far-flung Christmas tree business and operated two frozen custard stands in south St. Louis.”

But Ted Jr. successfully switched up the focus from tennis to custard. With Ted Jr.’s smiling face on TV touting custard and good times, and St. Louisans lining up at the lot in December for some of the best Christmas trees in town, the business moved up to iconic status. After sports games and concerts and theater, for birthdays and anniversaries and just because, locals lined up ten deep at the wooden windows to order special Ted Drewes custard concoctions. And it didn’t hurt anything that its Chippewa location was right on iconic Route 66. In 1985, to accommodate the growing crowds, they expanded from five serving windows to an impressive twelve. By then, just the two South Side stands — South Grand and Chippewa — remained, and they stayed busy.

“The Hill and South [locations] really remain stuck in the ‘40s and ‘50s. It’s still a tight-knit, clean neighborhood, and Ted Drewes is a part of that,” said Sonderman. “When you step into the [neighborhood], you’re taking a trip back in time. I think people take comfort in knowing that the concrete you had in 1959 is the same [now].”

Ted Jr.’s daughter Christy, no stranger to working at the custard stand, met and dated Travis Dillon while they were both in college in the ‘70s. “When my wife and I got married in 1977, I was working for a CPA firm after college,” explained Dillon. “The accounting business was just fine for me, but, after a while, Ted would ask me to help out a little bit. I was happy to do that. I went in for maybe one time a week at first and it grew to three or four nights a week, and I was still working for that CPA. Then Ted came to us and

said, ‘I could really use your help, Travis.’ He was working so many hours and we were feeling sorry for him. He asked me to go full-time, and my wife agreed with me that if I’m going to work this many hours anyway, I may as well do it.”

Travis and Christy are still there as co-owners and operators of the business, some 45 years later, and it seems to have worked out just fine for everyone. “We’re just tickled pink that we’re still able to hang in here,” quipped Dillon. “I think it’s fun. In what other business can you see your customers walk away smiling from ear to ear?”

Ted Drewes Frozen Custard celebrated 90 years in the business by hosting a celebration on April 25, 2019. Attended by local celebrities and politicians, former employees and longtime customers also turned out en masse. Even Fredbird, the St. Louis Cardinals mascot, showed up. Unfortunately, a drenching rain fell for a good share of the day, but Ted Jr. and Dottie presided over greetings and congratulations under the protective canvas of a tent. “And so, the hundredth [anniversary] is on our mind; we are wondering what we’re going to do,” Dillon mulled.

It’s still a family affair, with Travis and Christy Dillon at the helm, and on special occasions, Ted Jr., with Dottie by his side, still appearing as the beloved spokesperson. “It’s really good, guys, because Ted is St. Louis through and through, because he’s from here, he was born and raised here, and he’s proud of it and of Route 66 and the TV commercials,” said Sonderman. “The man always has a twinkle in his eye and a smile when he talks about Route 66.”

Approaching the century mark, the family still has no plans whatsoever to franchise the custard. “He [Ted Jr.] always said that if you want a business to run well, you have to be there and pay attention to the details. If you franchise it, you’re giving your business away to someone else to keep your name in quality,” said Dillon. But Ted Drewes products are available in the St. Louis area at Dierbergs, Shop ‘n Save, Schnucks, and Walgreens stores, plus in vending machines at Lambert-St. Louis International Airport. The recipe remains unchanged and is a closely guarded secret, although it’s a given that it’s mostly eggs, cream, vanilla, and honey — with no preservatives. One of the favorite variations is still the “Dottie” — your choice of a concrete or a sundae with mint, chocolate, and macadamia nuts. And just like frozen custard in the warmer months, the Ted Drewes Christmas Trees are undeniably still a holiday tradition.

“St. Louis is very big on sharing things from generation to generation. With Drewes, three generations have now grown up in the neighborhood, having the same experience for 90 some odd years now,” said Sonderman. “That’s why remembering these people is important now. Who will be the person who says, ‘Hey, there was this guy who sold frozen custard from a building trimmed with wooden icicles that you should know about, and you should know what an icon he was, and how important to St. Louis he was, and how his place anchored not just the neighborhood, but our region.’ And I think it’s kind of up to us to make sure people hear that story.”

Roberts

and Joseph L.

Photographs by Efren Lopez/Route66Images

Roberts

and Joseph L.

Photographs by Efren Lopez/Route66Images

wenty-plus miles north of Kingman, Arizona, where the original Route 66 forms a parabola, rests the only natural pass through the mountains of Mohave County between the towns of Hackberry and Valentine. The canyon area is known for its colorful rocks and rough terrain. Western yarrow, desert grass, and Arizona cottontop line the road. It seems like the only living things out here are the flora and fauna that call this place home.

Yet as you round a slight curve, a large, silver water tower stands on the right, announcing that the landmark Hackberry General Store is just ahead. A phalanx of antique gas pumps and retail signs stand facing 66; a sign above an awning announces, “YOU ARE HERE! HACKBERRY GENERAL STORE.”

Located less than a half mile as the crow flies from the “town” of Hackberry, the eponymously named General Store welcomes travelers with an outdoor area that is filled with Americana. Inside awaits the expected selection of t-shirts, souvenirs, and refreshments. Hackberry, located only 35 minutes northeast of Kingman along Old 66, is unincorporated. This means that there is no local government, but for most, that’s okay. The residents are an off-the-grid type of folk who cherish the land and enjoy their solitude — just like those who were there long before them.

In 1857, Lt. Edward Fitzgerald Beale, an Indian Affairs Superintendent and the big-man-in-charge of the Camel Corps, had been tasked by President James Buchanan to carve out a wagon road from Fort Defiance, Arizona, to the Colorado River. He used a team of camels to navigate the desert.

By the 1860s, the Mormons were using the old road to head west, sometimes setting up camp in Hackberry. By the 1870s, prospectors had been picking at the area for years, with a man named Jim Music helping to establish the Hackberry Silver Mine in 1875. It is one of the oldest mines along the Mother Road. The mine and the area are named after a hardy variety of tree known as the Netleaf Hackberry that grows across western Arizona and into the Sonoran Desert.

The original camp caught fire in 1879, burning all records of early settlement. Yet, because the area was so rich in silver, camps continued to pop up all over, and the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad established a station in Hackberry in 1882. There, miners and local ranchers could ship out their goods. But by 1919, claims were being disputed and the ore was running out; Hackberry was briefly deserted. That is, until Route 66 was established.

John Grigg, whose relatives still call the town of Hackberry home to this day, was born there in 1897. He set up a Union 76 service station in the 1920s, which he ran until he died in 1967. The only other businesses in town were the Northside Grocery Store and its conjoined Conoco Station. The store

Tand station opened in 1934, but by the time it closed in 1978, it was known as the Hackberry General Store. Details on the store during this span of its life are conflicting, but it possibly went through a series of owners before it folded.

The closure forced those who lived in the area to venture down Route 66 to Kingman for goods and sundries. In 1980, Interstate 40 was completed, connecting Seligman to Kingman, a development that further sealed the fate of Hackberry residents and their now-local Route 66, as both were suddenly isolated from longdistance traffic. However, things were about to take a turn for the brighter.

Early in 1992, famed Route 66 artist Bob Waldmire, an Illinois native whose heart beat for the open, rugged land of Arizona, was looking for somewhere to settle down after years of wandering 66. “He’d always been a rolling stone, ever since before his first day of high school,” said Buz Waldmire, Bob’s older brother. “He’d been driving the road for three or four years, but he eventually burned out from driving so much.”

Bob’s first interest for a place to settle had been the abandoned gas station at Cool Springs, about 45 miles southwest, but then he turned his attention to the Hackberry General Store. There, the remoteness inspired him. Paying a visit one day, he discovered no one at home so stuck a make-shift business card with his parents’ phone number in the crack of the door and headed off. A few days later, the owners, Bill and Lois Roan of Kingman, who had spent five years making improvements, contacted him. The timing was good, they were interested in selling the 22-acre property. Bob met with Bill, who named a price. Unsure, Bob called his mother for advice, and heard his father in the background saying, “Buy it! Buy it!”

So, Bob did buy it, and found his new home. In his Old Route 66 Dispatch newsletter he wrote, “Here that the edges of two great bioregions meet: The Colorado Plateau & the Basin & Range Province. Being a lover of the desert since my first visit (1962), this is my idea of ‘paradise’.” By early 1993, he was creating what he originally called the “International Bioregional Old Route 66 Visitor Center,” which was reduced to the Route 66 Visitors’ Center for breath’s sake.

He established himself in the vintage building and its surroundings, his iconic Route 66 bus and VW camper van parked outside. Using the area as his art studio, he spent much time creating hand-drawn and hand-written Old 66 Dispatch newsletters, postcards, and sketches of places up and down the Mother Road.

Inside, he offered visitors an opportunity to enjoy and purchase his own artwork and a sampling of what the road had to offer, including Funks Grove Maple Sirup and Cabin Creek pecans. In homage to his father, creator and owner of the Cozy Dog Drive-In in Springfield, Illinois, was a bookcase holding the “peace library.” Outside, visitors could view a cactus garden and wander a nature path. For Bob,

his Visitor Center was a place to commune with nature and gather one’s thoughts.

But Bob was not the predictable type, and the Visitors’ Center wasn’t always open. He did much of his work at night and slept during the day. Sometimes, to catch up on rest, he’d sleep for two or three days, which meant that those who visited him in the early morning could sometimes be bothersome, and Bob was not always overly welcoming. One day a group of visitors arrived at 8AM for a look around and left a note and a contribution to support the shop’s efforts. Unimpressed, Bob burned the money in his wood stove.

“He told that story on and off to other people, how he felt really bad,” said Buz. “It was one of the ways he knew that he would not be a good caretaker for visitors. He loved people, but he also loved his alone time.”

By 1998, Bob was one of a few residents of Hackberry who were angry at the quarrying going on in Crozier Canyon, an activity that was disturbing the area’s natural beauty and ecosystem. “It’s just more of the same as far as erasing nature and selling it off… I’m an old hippie nature lover,” said Bob to the Arizona Daily Star newspaper in September that year. “There is opposition to the quarrying around here, and it will continue after I leave, but I didn’t start it.”

The environmental and aesthetic impact of the quarrying simply added to Bob’s feeling of being encroached upon.

He needed his space. After six years of ownership, he was ready for his next move. He sold the Visitors’ Center and settled into retirement on the eastern slope of the Chiricahua Mountains in Portal, Arizona, where he had often spent winter months building a camp.

On August 12, 1998, Bob was visited by a couple, John and Kerry Pritchard, from Tacoma, Washington. It was their first visit with Bob, but it was at least their two-dozenth time driving by the Hackberry store on their way to and from their vacation home in Lake Havasu City. Each time, they fell more in love with the place that they knew would be perfect to display their lifetime collection of roadside memorabilia. Bob was ready to sell, and it turned out that John and Kerry were ready to buy. For Bob it was an escape; for the Pritchards, it was a motive to retire and move to Hackberry with their two sons. After some negotiation, the deal was made, and on December 1, 1998, the Pritchards took over. Bob headed back to Illinois to tie up some loose ends and prepare for retirement at his camp near Portal. He would bounce back and forth between Arizona and Illinois for the next eight years, but by 2006, it was clear that Bob was ill. He had the same symptoms of colon cancer that his father

and grandfather each experienced before dying from the disease. Bob moved back to the family farm in Rochester, Illinois, where he spent the next three years, surrounded by family and friends, before passing away in December 2009. The old road had lost a beloved ambassador.

Meanwhile, the Pritchards restored the name of the place to the Hackberry General Store and spent years curating their collection of Route 66 memorabilia and Americana. Bob’s bioregional center morphed into a popular souvenir shop selling Route 66 trinkets on the inside and offering photo ops of the Pritchards’ massive collection outside.

A bright red Pegasus in mid-flight — a vintage promotional display featuring Mobil Oil’s former mascot — still crowns the building. Elsewhere, an old Greyhound Bus stop sign, a neon Phillips 66 shield, a faded red water pump, the shell of a rusted Ford Model-T, sun-bleached steer skulls, and metal advertising signs hawking everything from Diamond Tires to Clabber Girl Baking Powder, are scattered about.

The Pritchards’ additions gave new life to a valuable travel stop. They employed their rescue dog, Max, and a donkey named Rudy as unofficial greeters and kept the business open all day. It was a viable destination once again.

Ultimately, Bob was not happy with what had happened to his International Bioregional Old Route 66 Visitor Center. “Bob left Hackberry on kind of a sour note,” said Buz. “Because what they did was turn it into a rather thriving tourist stop where people would come in, look around, take a few pictures, buy some Chinese-made goods, which offended [Bob], and [then] leave. So, he didn’t like what his store had become — very commercialized.”

In 2016, the Pritchards were also ready to retire. They had hoped their son would take ownership of the place, but he had no interest. But then Amy Franklin, an employee who had been there ten years — plenty of time to fall in love with the place, as the Pritchards had done — asked John not to close the shop.

“I said, ‘John, you can’t do that. This place is historic. It’s known all over the world,’” Amy explained. The next day, Amy, who moved to Hackberry in 1999 to escape city life in Chicago, asked Pritchard if he would consider selling it to her. Her question took him by surprise, and he told her that he would discuss it with his wife. “And the very next day, he said, ‘I’d like to make a deal,’” she said.

Prior to her employment in Hackberry, Amy had visited the Mojave and had fallen in love with the idea of the warm, arid desert. It contrasted sharply in her mind with the lake-effect winds and cold of Chicago. When she did visit, a friend who worked at the General Store said that she was leaving her position and asked her if she was looking for something to do. “I thought, ‘Why not?’ I’ve never looked back,” Amy said. “I’m so glad I took it over and am able to keep it going.”

Her daily mantra for the future: “Keep it open. Pay my bills. Add to the collection.”

Once she started running the show, Franklin didn’t want to disappoint visitors hoping to see a Corvette grace the entrance of the store, so in an unofficial representation of new ownership, she parked a 1990 Corvette in front of the gas pumps. It might not be a ’57 Corvette like the Pritchards owned and displayed, but it was still considered an antique. Alas, that Corvette was causing problems of its own. “I sold that ‘Vette. It was nickel and diming me,” she added. “It had a computer problem. It was the first year the Corvette had a computer. Even my good mechanic was chasing his tail all the time on something electrical. A guy who is 78 years old and always wanted a Corvette saw this one. He lives in Kingman and fell in love with it. I gave it to somebody who not only loved it but fixed it.”

Amy waxed philosophic about her decision to buy the store. “With me, it was very important. And really, if I hadn’t taken it over, it would have just been closed up,” she stated emphatically. “People would be disappointed. After seeing hundreds of pictures online of the Hackberry General Store, and they come here and go, ‘What happened?’ I couldn’t do that.”

In addition to a handful of locals who regularly stop by, the Hackberry General Store attracts many Route 66 travelers, and is a highlight of their journey. “Hundreds of visitors come by the Hackberry Store and say, ‘I came all the way to the U.S. to visit your store.’ I say, ‘Are you kidding me?’ They say, ‘No, this is the coolest place in the whole United States,’ and they just saw the Grand Canyon!”

But when each group of tourists leaves, it’s just Amy Franklin and the flora and fauna that survive in the rocky quiet that is Hackberry. The store and surrounding area take on a lonely mood again and the once busy tarmac just out front bakes silently in the desert sun, alone with its memories. That is, until the next carloads arrive.

HISTORY YOU CAN TOUCH.

VISIT TUCUMCARI NM.COM

#tucumcariproud

Come explore Tucumcari’s four iconic interactive museums which showcase the town’s old west history, Route 66 Americana heritage, railroad roots, and its role in the ‘Age of Dinosaurs’.

Photograph by David J. Schwartz - Pics On Route 66

Photograph by David J. Schwartz - Pics On Route 66

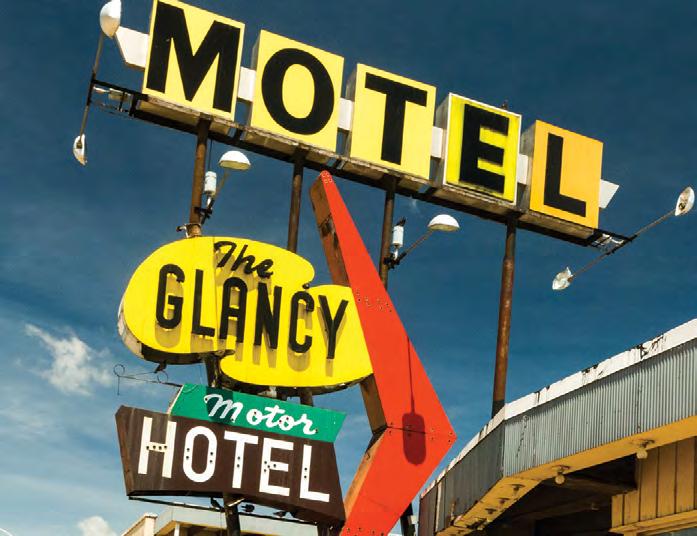

Heritage travelers run the gamut in tastes and preferences. Among those traveling Route 66, many opt for the mid-century mom-and-pop motel experience, especially since it perhaps best captures the hive mind’s memories of what the old road once was like. After all, the 1950s was a period of unprecedented economic growth, and large numbers of America’s families were hitting the road. Although chain motels were busy getting their start back then, roadside lodging was still dominated by independent properties, accounting for a wide range of amenities — or a lack thereof.

But Route 66’s origins date back another three decades or so from that mid-century point, and when the Mother Road and all the others were christened with their federal numbers in 1926, lodging was either in city center hotels or tourist camps, a highly bifurcated Rich v. Poor scenario. While the motel had its birth in 1925, it took many years for them to be commonplace along American highways. And while those aging motels are still popular — some prefer the vintage venue — others like modern twists on what was considered proper lodging. The Hotel Vandivort in Springfield, Missouri, is a perfect example of the latter.

Tucked neatly in the downtown district, only a couple of blocks off Route 66, Hotel Vandivort — named years ago for Springfield Little Theatre volunteer Francis Vandivort — occupies a decades-old historic building that wore many hats throughout its lifetime.

“The historic structure was originally built in 1906 as a Masonic Temple, [and] offered up 40,000 square feet of floor space with a spacious auditorium on the fourth floor,” said Hannah Dingman, Marketing Manager. “The center played host to local Masons for more than 75 years.”

And then, like many historic buildings, it underwent a transition. “The Vandivort went through a prolific renovation in the 1980s, with most of the space divided into offices. Unfortunately, the drop ceilings and drywall hid much of the building’s original charm,” Dingman continued. “During this time, it was placed on the Springfield Historic Sites Register and the National Register of Historic Places.” In recent years, the building had even served as home to the Springfield Contemporary Theatre. It’s had a lot of faces over the decades.

The building was reimagined again when brothers Billy and John McQueary, veterans of a century-old Springfield family business and of the tech world, shook their own world a bit in 2012 by buying the four-story red brick building. The brothers took the structure’s classic architectural ornamentation and methodically transformed the empty space into the selfproclaimed “first urban boutique hotel of Springfield.” After a $13.5-million conversion, Hotel Vandivort opened on July 13, 2015, initially offering 50 guest rooms. In 2019, the hotel increased its guest rooms by an additional 48 via an expansion, located directly across from Hotel Vandivort.

“The need for an upscale boutique hotel in the heart of downtown inspired the McQueary brothers to purchase the Vandivort building with its rich history and prime location,” said Dingman. “They began reclaiming the building’s history and original beauty, while creating a thriving and social hospitality venue.”

Because the hotel was fashioned from an existing building, rooms are not cookie-cutter like at many other newer properties. High ceilings and exposed brick from the original structure were intentionally incorporated into the design whenever possible to mix well with the sleek and well-

appointed contemporary decor. However, technologically up-to-date room amenities include in-ceiling speakers and the option of controlling audio and lighting via a guest’s mobile devices.

The first floor boasts The Order, a sophisticated restaurant that serves a modern take on Missouri cuisine. By incorporating the building’s key elements such as the brick wall and wood accents, while introducing contemporary touches such as the 92 luminescent glass bulbs atop the dining area’s tall ceiling — hand-blown specifically for the restaurant by local artisans — The Order presents a beautiful juxtaposition of old and new. Another historical piece of note is the stunning 2,800 square-foot Vandivort Ballroom located on the building’s top floor, which has been hosting events for more than 100 years.

Over at the V2 (the new addition) is the casual-attire Vantage Conservatory & Lounge, a rooftop bar featuring creative cocktails and other adult beverages. The elevated rooftop offers stunning views of the city’s skyline, and it is not impossible for patrons to catch a glimpse of where Route 66 passes through city center, or to spot the awesome History Museum on the Square sign. But it is the 70 seats in The Order, along with 80 more in the lobby, that the developers hope will entice locals to mingle with out-of-towners staying and dining there.

The Vandivort is a pleasant alternative from both midcentury motels and historic hotel renovations in that it is purely a 21st Century interpretation of how upscale lodging should be. The interior design features modern aesthetics to balance the history of the building, often relying on glass globes, greenery, and negative space to add ambience. The McQuearys’ efforts paid off handsomely in 2016 when they were awarded the Boutique Hotel of the Year award by the Boutique & Lifestyle Lodging Association.

Social media buzz has been a mainstay of Hotel Vandivort’s marketing efforts. The story goes that the designers installed just the right kind of lighting in the first-floor restrooms to make everyone look like a cover model, airbrushed and all. And in 2016, patrons were encouraged to post photos from the restrooms, using the hashtag #HotelVandivortBathroomSelfie. And post they did. Along the way, the Vandivort became the only hotel in Springfield to earn the Four Diamond rating from the American Automobile Association. This prestigious award places the hotel in the Top 5% of more than 28,000 properties in the U.S.

Springfield, Missouri, is famous for many things: it’s the birthplace of Route 66, where Cyrus Avery, John Woodruff, and others agreed on April 30, 1926, to the Route 66 moniker for the road that they had envisioned, it is the site of the historic Wild Bill Hickok-Tutt shootout that created a legend, and it is known lovingly as the Queen City of the Ozarks. The city has increasingly become a favorite Route 66 layover because of its history, numerous attractions, dining, vintage neon signs, breweries, and a number of previous alignments of the highway.

Today’s Route 66 travelers are arguably different from those from past decades, largely due to their higher level of cultural exposure and their discerning nature. They are keen to explore and experience, but they want to enjoy some creature comforts, too. And down in Springfield, the Birthplace of the Mother Road, Hotel Vandivort and venues like it are doing what Route 66 businesses have always done: rising up to meet the traveler and offering them exactly what they want.

A trip down the Mother Road through Pulaski County, MO, is a journey through time. These 33 miles of Historic Route 66 carve through the rolling Ozark hills that pioneers and pilgrims throughout history have called home. Witness both natural beauty and engineering marvels at the scenic overlooks of Devils Elbow. Catch a rare glimpse at the well-preserved, 19th-century structures around Downtown Waynesville. Pay tribute to the many men and women who passed through Fort Leonard Wood in service of our country at our patriotic memorials and museums. With so many sites to see, you won’t regret making this time-traveling excursion an overnighter.

Plan your trip at visitpulaskicounty.org/roadtrip.

Photographs by Jim Luning

Photographs by Jim Luning

on Romero had a dream. His entire life had been filled with music. His grandmother, who was born in Mexico, instilled a love of music into the family dynamic with her playing the piano, classical guitar, and violin. Grandma Romero died at the ripe old age of 103, leaving behind a legacy for her children and grandchildren to follow. And they did just as their grandmother would have wanted. Romero embraced the art of creating and enjoying music, and a path was made.

“My father, Robert, picked up and played jazz. He taught himself how to play clarinet, flute, and other instruments. My brother played piano and guitar. My mom would perk up and say, ‘I played the radio,’” said Ron with a chuckle. She did not share the family’s musical abilities.

Robert Romero supplied his family with space and with instruments. At the family home a separate building was created that was specifically designed for performing everything from classical music to rock and roll. Nearly every instrument, including a radio, had a home in that special space.

Ron attended Joliet Junior College and earned certificates in fields such as Audio and Video Technical Specialist and Event Production Management. He was previously employed as Director of Events for Encore Productions at the Hyatt at McCormack Place, and in 2000, he became the owner of Stage Right Productions, a live event production company. And through him a new attraction along the Mother Road would eventually be born — the Illinois Rock & Roll Museum — and its journey has been anything but ordinary.

They say that behind every successful man is a strong woman. Ron was quick to recognize this truth when he met his wife, Patti, in 2009. She reached out and introduced herself to him. Being a quick thinker, he asked if he could put her on the band’s mailing list. There was no band and there was no mailing list, but the request got him the information that he needed to stay in contact with her. Before he had a chance to call her though, she called him. They married four years later and now have three daughters and three grandchildren.

As time went on, Ron developed a foothold in the music industry, one that was satisfying and profitable, but something was missing. He wanted to pass on his love and knowledge of music to other people. He wanted to do more than just take the records off the shelf and enjoy the beats. Performing was not enough. But he wasn’t sure how to make that dream a reality. So, in an effort to find some clarity, he traveled around the country, visiting music museums. He found some fulfillment and borrowed some useful ideas, but he still didn’t know exactly what he could do to share his enthusiasm for music in a unique and effective way. That was until he attended an exhibit in California and a spark was lit.

R“In 2013, Rick Nielsen’s Cheap Trick had an exhibit at the Berkeley Museum. While attending the exhibit, I was pushed over the edge of amazement because there were people from around the world who came to see that exhibit. I loved Cheap Trick; they were one of my favorite bands. But I wondered, what could I do if I opened my own museum and added other performers like REO [Speedwagon], Styx, Buddy Guy, and Muddy Waters? A light came on and I knew what I wanted to do. I would open my own museum.” He began looking for the place that would bring his dream to life.

Illinois has deep roots in the history of rock and roll, with a long list of iconic rockers hailing from the state. Folks like Sam Cooke, Muddy Waters, Earth, Wind and Fire, Miles Davis, and Cheap Trick, to name a few.

“The influence of Illinois rock and roll can be seen in these examples: The Rolling Stones got their name from a song by Muddy Waters called Rollin’ Stone ; The Rolling Stones also sang a song called (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction , and Muddy Waters wrote a song called I Can’t Be Satisfied; and Led Zeppelin’s first album primarily used Willie Dixon songs,” exclaimed Ron.

The town of Joliet is the home of the country’s first Dairy Queen. But besides luscious dairy treats, Joliet, just 35 miles southwest of Chicago on coveted Route 66, is also the home of the Rialto Square Theatre. Opened in May 1926, the theatre has been nicknamed the “Jewel of Joliet.” It has played host to fashion shows, plays, and many amazing performers, including the Marx Brothers, Chuck Berry, Sam Cooke, Buddy Guy, and others. Joliet was not just a place musicians passed through while traveling on Route 66 to their next gig, it was THE gig. Anyone who was anyone in the entertainment world aimed for a show date at the Rialto in Joliet.

For Ron, the rich rock and roll history made the town the perfect location for his museum. “Joliet is the third largest city in Illinois and connects with Routes 80, 55, 66, and U.S.30 (Lincoln Highway). There is a new train station, and the city is undergoing a rejuvenation. I wanted the museum to be a part of that synergy. Joliet is fast becoming a ‘music city.’ Besides, you don’t have to fight the Chicago traffic problems in Joliet.”

With the decision made on where he would house his museum, Ron Romero now had to find the right brick and mortar that his museum could call home.

It was 1929 and Jackson Jarvis Cohen was in search of a larger space for his dry goods store. He found it at 9

West Cass Street in Joliet. A three-story, Beaux-Arts/ Sullivanesque-style commercial building caught his eye. The location was central to town merchants and, as a bonus, it was just down the street from the Rialto Square Theatre where theatergoers would pass by the store and gaze at the merchandise in his windows.

Cohen made his deal with the developer, Dr. J.J. Coady of Minooka, and leased the entire space for $10,000 annually. At the direction of Mr. Cohen, the building was painted white in correlation to the name of the store being the “White Store.” By 1937, the White Store had outgrown the space and moved to another location, but the building would continue to be known as the White Store.

The building changed hands several times, once to Goldblatt Brothers Department Store and then to The Silver Dollar Store. In 1977, the building once again changed hands making it the Buy-Rite Furniture Store with Jack’s Gym occupying the entire third floor. When Buy-Rite Furniture closed, the building was briefly considered a tear down, for a newer, more modern building, but that idea was short-lived.

When Ron discovered the store, he knew that he had found just the right building to become the museum’s home.

“I decided on the White Store because it was the right size, had the right space, and was in the right location. I could envision what the building could be with the right renovations. Besides, it is directly across the street from the Forge Theatre and a few blocks away from the Rialto Theatre,” said Ron. The White Store was exactly what he needed.

In 2019, with funds garnered from grants and donations, he was able to purchase the building under the Illinois Rock & Roll Museum on Route 66 organization.

It would take three years to refurbish and renovate the multi-level building, and the process is still ongoing. Besides the necessity of bringing it up to code, the space had to be reconfigured to meet the museum’s needs.

The first level of the museum focuses on the educational aspects of music. Students can take classes in a variety of musical instruments, but what makes the program unique is its offering of classes on music as a business. Students learn how to make money making music.

“Not everyone is going to be a recording star. Other people are going to be a part of services, like a sound engineer, light engineer, business manager, tour manager, and we want to be able to show these opportunities to the students.”

The museum also works with two local colleges that offer music programs. Students of all ages and backgrounds can get their feet wet in all aspects of the music industry through the museum. There is also a program that works with economically challenged students by helping them obtain instruments through donations from the public.

The second level is an exhibit space that begins with Blues, Jazz, and Gospel music and evolves into what we now call Rock and Roll.

The majority of the third level is exhibit and Hall of Fame space, but there is also event space.

There are two radio stations, one showcasing the 19601970s era which is for display only, and the other is a working station that is visible from both the street and inside the building. Also, on that level is a small concert area for student performances.

While the museum is not ‘officially open’, on September 2, 2021, it celebrated its inaugural inductees into the Hall of Fame. Performers included Buddy Guy, Chicago, Cheap Trick, REO Speedwagon, Muddy Waters, The Buckinghams, The Ides of March, and DJs Dick Biondi and Larry Lujack. The second Hall of Fame inauguration happened on June 5th, 2022. While the museum was still not officially opened, the inductees included Styx, Chuck Berry, Sam Cooke, Dan Fogelberg, New Colony Six, Dennis DeYoung, and Jim Peterik. John Records Landecker was inducted into the DJ category.

“We do all sorts of events,” said Ron, “from concerts, car shows, Hall of Fame induction ceremonies. They are all fundraisers for us. We are not officially open, but we are very active in the completed spaces that we have available.”

Yet, with all that he has going on in his historical structure, the big white building still needed something unique to set it apart. Shannon MacDonald, known as the World’s Best Beatles Artist , was commissioned to create a 24-foot-tall guitar sculpture to be mounted on the outside front of the building. With assistance from the Heritage Corridor Convention and Visitors Bureau, the museum was able to secure a grant from the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity. Together with help from other sponsors, the impressive ornamentation designating that you have arrived at Illinois Rock & Roll Museum on Route 66 became a reality. MacDonald named the guitar “Gigantar.”

On January 14, 2023, Gigantar was loaded onto a Legacy Express Trucking flatbed trailer in Freehold, New Jersey, and began the 800+ mile trek to 9 W Cass Street in Joliet, Illinois. The event was commemorated with a celebrity launch party at The Stone Pony in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Upon entering the state of Illinois, many stops were made to allow photo opportunities for fans and supporters who were lined up along the route and hoping to catch a glimpse of Gigantar.

On January 20, 2023, nearly 500 people attended a celebratory lighting ceremony as Gigantar, the largest guitar structure in the world, got mounted onto the front of the vintage building on Route 66. Rick Nielsen from Cheap Trick flipped the switch illuminating the giant structure.

Ron Romero continues to perform. His father and grandmother’s musical influence is still in him. “I am a lifelong musician and still play in bands. I perform in the Illinois Rock & Roll Museum Band and have played with some of the inductees into our Hall of Fame.”

With the missing piece to Ron’s career satisfaction now in place, the real work begins. He is the Executive Director and the museum’s Chairman of the Board. It is his full-time job now.

The establishment of the museum is just one more stop in the never-ending entertainment on Route 66. Where else but Route 66 will you find Arcadia: America’s Playable Arcade Museum, the World’s Largest Laundromat, the Pink Elephant Antique Mall, or Henry’s Rabbit Ranch? For a road that has ceased to exist as a United States highway since 1985, the Mother Road is still a hugely beloved route for those who enjoy stepping out of their interstate highway comfort box. Just like the song goes, “Get Your Kicks On Route 66 ,” new kicks are popping up every day, and with all the old and brand new attractions and businesses to be discovered and enjoyed, there are lots of “kicks” still to be had.

On Museum Square in Downtown Bloomington, the Cruisin’ with Lincoln on 66 Visitors Center is located on the ground floor of the nationally accredited McLean County Museum of History.

The Visitors Center is a Route 66 gateway. Discover Route 66 history through an interpretive exhibit, and shop for unique local gift items, maps, and publications. A travel kiosk allows visitors to explore all the things to see and do in the area as well as plan their next stop on Route 66.

CRUISIN’ WITH LINCOLN ON 66 VISITORS CENTER

Open Monday–Saturday 9 a.m.–5 p.m. Free Admission on Tuesdays until 8 p.m. 200 N. Main Street, Bloomington, IL 61701 309.827.0428 / CruisinwithLincolnon66.org

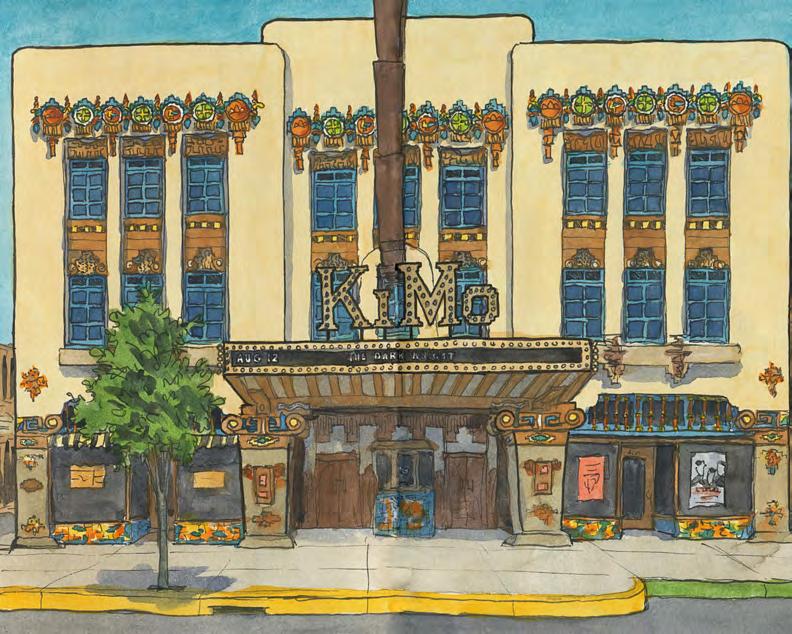

*10% o gift purchases

At the corner of Central Avenue and Fifth Street in Downtown Albuquerque, New Mexico, the KiMo Theatre has screened motion pictures and hosted live performances since its opening on September 19, 1927, earning its place among the extravagant, palatial movie theaters of the 1920s. But to tell the whole story, one must start from the beginning.

In 1885, ItalianAmerican entrepreneur Oreste Bachechi began his career with a modest business in a tent near the railroad tracks in Albuquerque. Over time, as the city expanded, so did his portfolio of odd jobs, which included peddling alcohol, owning a grocery store, and, in partnership with Joe Barnett, running the Pastime Theatre — but that wasn’t enough. Bachechi dreamed of his own film house to join the pinnacle of movie magic and, in 1925, decided to get to work on building a venue that would stand out from others of its kind.

Soon, Bachechi enlisted Carl Boller of Kansas City-based Boller Brothers, a firm that specialized in theater design in the Midwestern United States, to bring his vision to life. Boller, along with Carl Von Hassler, one of the region’s most popular painters, embarked on a tour of New Mexico, exploring the Pueblos of Acoma and Isleta, as well as the Navajo Nation, to draw inspiration in designing a relic that honored tradition while infusing bits of 1920s Art Deco America. Following months of research, Boller presented Bachechi with a watercolor rendering that met his approval — a pioneering amalgamation of American Indian and Art Deco, dubbed “Pueblo Deco,” and each aspect of the resulting three-story brick-stucco building, both inside and out, was chosen with significance, even its name, which means “king of its kind” in the language of the nearby Isleta Pueblo.

The interior design featured plaster ceiling beams textured to resemble logs and adorned with culturally specific imagery. Air vents were cleverly disguised as Navajo rugs, while chandeliers were shaped like war drums and Native American funeral canoes. A wrought-iron bird motif descended the stairs, along with rows of buffalo skulls adorned with garlands and eerie, glowing amber eyes. Of particular note was the use of the swastika, a cultural symbol of life, freedom and happiness, which has remained unaltered, despite its nownegative — and ironic — connotations.

pLike its symbols, color also played an important role in the design. The space is splashed with warm hues of orange, yellow, white, and red in a blend of both regional heritage and the opulent, Old Hollywood aesthetic of the 1920s.

The theater, which cost $150,000, was completed in less than a year, with an extra $18,000 for the Wurlitzer pipe organ to accompany the silent films. Dr. Shelle Sanchez, Director of the Department of Arts & Culture for the City of Albuquerque, who has been dedicated to KiMo in her current position since 2018, said the design is like nothing she’s seen before.

“It’s magical and a little surprising for its mix of imagery and materials,” Sanchez said. “You can spend the ten minutes waiting for a show to start just looking at the architecture and the murals painted into the space.”

Oreste Bachechi died just one year after the theater opened its doors, leaving its management to his sons, but the theater continued to be beloved by visitors until the early 1960s when a massive fire nearly consumed the building. Neglect set in, accelerated by the exodus from downtown, experienced by many cities during that time period, as the public focused their gaze on “newer” attractions, like the various malls and entertainment centers popping up on the outskirts of the city, so different from the grandiose picture palaces enjoyed for forty years prior.

Slated for destruction, KiMo was saved in 1977 when a group of city activists, historians and residents voted to purchase and restore it, and today, it remains a registered historic site and continues to operate as a popular attraction for entertainment seekers both near and far, collecting tickets from roughly 78,000 each year.

“It’s a popular place, and it’s photographed every day by people who pass [by],” Sanchez said. “Regardless of whether or not people travel specifically to see it, its eye-catching façade and big marquee captures the attention of everyone who passes, and I can only hope that the KiMo will remain a place of magic in the community for another hundred years.”

So, if you find yourself in the audience waiting for the curtain to open, take a moment to appreciate the legacy of the KiMo Theatre—a funky little landmark just as iconic as the road it calls home.

By Ellen Proctor

Photographs by Efren Lopez/Route66Images

By Ellen Proctor

Photographs by Efren Lopez/Route66Images

Just say the name of this state in a crowded room and chances are that someone will break into song. “Oklahoma! Where the wind comes sweepin’ down the plain.” Route 66 sweeps across the Sooner State in the longest stretch of original roadway that is still drivable today. Truly America’s Main Street, Oklahoma’s section of the Mother Road is home to a plethora of charming roadside diners and eateries. But there is one diner, located at the intersection of 11th Street (Route 66) and Yale Avenue in Tulsa, Oklahoma, that is not only an iconic realization of the American Dream, but has been a successful part of the Tulsa restaurant scene for 36 years, Tally’s Good Food Cafe.

The year was 1987, and Mark & Mary’s, a local restaurant chain in Tulsa, was closing one of their locations. The eatery, opened just four years prior, had been put up for sale and it needed a lot of work, but the Route 66 location made it an ideal spot.

“I jumped on it,” said Tally Alame. “It was really just one room with a small kitchen.”

As with many locations along America’s most famous highway, background information on the building itself is scarce, but it is believed that the location was once a grocery store. The old terrazzo floor is still intact.

The thirteenth of November fell on a Friday in 1987, but there was nothing unlucky about it for Alame. That was the day that he first opened the doors of his new restaurant. “I’m just going to open — I’m not going to believe in superstitious stuff,” Alame remembered. “It was Mark & Mary’s Good Food Diner, and I kept the name for two months.” He thought that keeping the old name would help him keep the old, already established customers. But he soon found out that wasn’t the case. It appeared that the name carried with it a not so positive reputation associated with uncleanliness among other things. But Alame was not one to stay idle for long. He decided on a new name. “I changed to Tally’s Good Food Cafe, and that changed the whole ballgame.”

One of the first things that he did after opening for business was to give food away. Yes, he decided that it would be a good practice to help his new community. The fourth Thursday in November is Thanksgiving, and though he hadn’t been open for a full two weeks, he made the local papers as one of five Tulsa restaurants giving away a free dinner. Tally’s not only provided a meal, but also offered free delivery to people who were described as “shut-ins,” or invalids, people who weren’t able to eat in the restaurant. And he has continued the tradition for 36 years.

“Thanksgiving is my favorite day of the year, because it’s about being thankful and about sharing with others. Everyone is welcome, and it’s all free,” Alame shared. “I open the doors and feed more than 1200 people.”

Alame’s journey to becoming a successful restaurateur wasn’t an easy one. He is one of ten children — five boys and five girls. In 1979, they were living in the city of Beirut, in Lebanon. A civil war was raging, and it was impossible to get a good education there at the time. So, when Alame was 19, his family sent him to Tulsa.

One of Alame’s brothers was already living in the area, having come to the U.S. two years before, and he also had cousins in town who owned Jamil’s Steakhouse. Originally opened in 1945, the steakhouse is considered the oldest Lebanese Steakhouse in Tulsa. The Lebanese community in Oklahoma has deep roots. Even before the region attained statehood, Oklahoma historians note that early Middle Eastern immigrants who settled in Oklahoma came mainly from Jediedat Marjeoun (Judaidet Marjayoun), a small town in southeastern Lebanon. One early immigrant’s success story would inspire more to follow in his footsteps, and soon entire extended families would be a part of the growing and vibrant Lebanese-American community of Tulsa and across the region. In fact, the character of peddler Ali Hakim in the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical Oklahoma is based on one of these early Middle Eastern settlers.

Alame settled right into his new life in Tulsa, first attending the University of Tulsa English Institute where he learned English as a third language, his native language and French being the first two. He later enrolled at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater to pursue a major in business management and marketing. Alame had a natural love of cooking that had been nurtured at home, so while he studied, he also worked at his cousin’s restaurant during the weekends, getting his first taste of the local hospitality industry.

“My lovely mother is the best cook ever,” Alame said. “She would cook everything in a big pot. She would ask me to help her in the kitchen. She’d ask me to cut cilantro, to dice garlic. She was a great example.”

After graduating from college, Alame worked at various restaurants in Oklahoma and Texas developing his dream

of one day owning his own business. “I learned concepts and ideals, learned a lot about hospitality — good service, making eye contact. Good food, good atmosphere. If you cook it, they’ll come to you.” At the age of 26, everything fell into place when he noticed that a certain property on 1102 South Yale Avenue was for sale.

Alame developed a set of basic principles by which he runs his business and posts them proudly on his restaurant’s website: treat every person who enters the diner just as you would like to be treated; serve plenty of good wholesome food at a reasonable price; and never use anything but the highest quality of food available. He makes his own batter, serving up homemade onion rings, dinner rolls, pancakes, and cinnamon rolls. While he does have some traditional Lebanese food — cabbage rolls on special, homemade chicken kabobs — he quickly learned that in the late 1980s, his clientele didn’t want food such as hummus or tabbouleh. The menu is mainly authentic diner food, with a full breakfast menu available all day and a wide variety of entrees served in a classic old-style diner atmosphere.

By 1990, just three years after he opened his doors, business was brisk enough that he needed more seating.