VIABILITY OF PHOTOS IN WILLS

STRATEGIES FOR REMEDIATING LOAN DEFAULTS

INTANGIBLE ASSETS IN PROPERTY TAX APPEALS

Leases and REAs, COREAs, and Operating Easements

Considerations for Drafting and Negotiating

PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN

|

TRUST AND ESTATE LAW SECTION VOL 38, NO 2 MAR/APR 2024

A

BAR ASSOCIATION

REAL PROPERTY,

The American Bar Association’s 36th Annual RPTE National CLE Conference

REGISTRATION IS NOW OPEN!

WRITING COMPETITION WINNERS

Welcome Message from RPTE Chair

This premier American Bar Association’s real property, trust and estate law conference will take place in Washington, D.C. May 8–11, 2024. The American Bar Association’s 36th Annual RPTE National CLE Conference is renowned for its exceptional business connection opportunities, innovative programming, and trending legal topics. We cannot forget about the latenight fun if you choose!

WHY ATTEND?

Dear Esteemed Colleagues,

I am thrilled to extend a warm welcome to all of you as we approach the 36th Annual Real Property, Trust, and Estate (RPTE) National CLE Conference, scheduled for May 8-11 at the Capital Hilton in Washington, D.C.

Premier Experience: Upgrade your conference experience. As a premier registrant, you will gain exclusive access to the VIP Only Lounge, discounts on conference events, first access to reception, red carpet check-in area and gold name badge.

In-Depth Programming: Interactive sessions led by industry experts. Business Connection Opportunities: Connect with fellow legal professionals. Innovative Trending Legal Content: Stay at the forefront of the real property and trust and estate landscape.

36TH ANNUAL RPTE NATIONAL CLE CONFERENCE

May 8-11, 2024 | Capital Hilton

This year’s conference promises to be an enriching experience, filled with engaging sessions, valuable business connections, and the chance to earn CLE credits. Our agenda is packed with insightful presentations by leading experts in real property, trust, and estate law, ensuring that you leave with a wealth of knowledge and practical tips to apply in your practice.

The Capital Hilton, with its prestigious location and exceptional facilities, provides the perfect backdrop for our gathering. In addition to the educational sessions, we have arranged a variety of social events to allow you to connect with peers and build lasting professional relationships in a relaxed and friendly atmosphere.

May 8-11, 2024 |

Washington, D.C., with its rich history and vibrant culture, is an ideal setting for our conference. I hope you will take some time to explore all that our nation’s capital has to offer.

36TH ANNUAL RPTE NATIONAL CLE CONFERENCE May 8-11, 2024 | Capital Hilton

www.rptecleconference.com

As Chair of the RPTE Section, I am proud to be a part of this incredible community and look forward to welcoming you in person. Let’s make the 36th Annual RPTE National CLE Conference a memorable and productive event!

Robert S. Freedman

Chair | American Bar Association, Real Property, Trust, and Estate Law Section

May 8-11, 2024

36th Annual RPTE National CLE Conference and Leadership Meeting

AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION

WASHINGTON

36th Annual RPTE National CLE Conference

Capital

Hilton

AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION

pp-38-01-janfeb24-design-cc23.indd 4 12/14/23 11:41

rptecleconference.com

WASHINGTON

1.

AM

Tuesday,

Tuesday, March 14, 2024

Register

Register for each webinar at

Tuesday, April 11, 2024 12:30-1:30

March/april 2024 1 PROFESSORS’ CORNER January/February 2024 1 PROFESSORS’ CORNER November/December 2023 1 PROFESSORS’ CORNER A monthly webinar featuring a panel of professors addressing recent cases or issues of relevance to practitioners and scholars of real estate or trusts and estates. FREE for RPTE Section members! Register for each webinar at http://ambar.org/ProfessorsCorner SOURCE OF INCOME DISCRIMINATION LAWS Tuesday, November 14, 2023 CORPORATE LANDLORDS Tuesday, December 12, 2023 September/OctOber 2023 1 PROFESSORS’ CORNER Explore opportunities to get exposure to more than 15,000 Real Property, Trust and Estate Law Attorneys at conferences and all media platforms. CHRIS MARTIN | Corporate Opportunities 410.688.6882 | chris.martin@wearemci.com BRYAN LAMBERT | Law Firm Opportunities 312.835.8978 | bryan.lambert@americanbar.org Partner with us www.ambar.org/rptesponsorships A monthly webinar featuring a panel of professors addressing recent cases or issues of relevance to practitioners and scholars of real estate or trusts and estates. FREE for RPTE Section members! Register for each webinar at ambar.org/ProfessorsCorner A monthly webinar featuring a panel of professors addressing recent cases or issues of relevance to practitioners and scholars of real estate or trusts and estates. FREE for RPTE Section members!

http://ambar.org/ProfessorsCorner ADAPTIVE REUSE, PART I

for each webinar at

January 9, 2024 12:30-1:30 pm ET LEGISLATIVE EXACTIONS & KNIGHT V. METRO GOVERNMENT OF NASHVILLE

12:30-1:30 pm

Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association. A monthly webinar featuring a panel of professors addressing recent cases or issues of relevance to practitioners and scholars of real estate or trusts and estates. FREE

members!

Tuesday, February 13, 2024

ET

for RPTE Section

http://ambar.org/ProfessorsCorner DEATH AND TAXES: DYNASTY TRUSTS AND WEALTH IN AMERICA

12:30-1:30 pm

REGULATION AND A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT TO PRIVATE PROPERTY

ET

pm

AM

ET

March/april 2024 2 March/April 2024 • Vol. 38 No. 2 CONTENTS 26 6 Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association. Features 6 Leases and REAs, COREAs, and Operating Easements: Considerations for Drafting and Negotiating By D. Joshua Crowfoot, Karen M. T. Nashiwa, and Joseph M. Saponaro 26 The Viability of Inserting Descriptive Photos in Wills: A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words By Gerry W. Beyer and Scout S. Blosser 31 Understanding and Using Financial Statements in Valuations and Planning By Stephen J. Bigge, Timothy K. Bronza, Abigail R. Earthman, and Bruce A. Tannahill 44 Strategies for Remediating Loan Defaults By David L. Zive 48 Crisis Planning: The Oxymoron That Could Save Your Client By Dale M. Krause 52 Intangible Assets in Property Tax Appeals By Barry J. Cunningham and H. James Stedronsky Departments 4 Uniform Laws Update 20 Keeping Current—Property 40 Keeping Current—Probate 56 Technology—Property 60 Land Use Update 62 Career Development and Wellness 64 The Last Word

A Publication of the Real Property, Trust and Estate Law Section | American Bar Association

EDITORIAL BOARD

Editor

Edward T. Brading

208 Sunset Drive, Suite 409 Johnson City, TN 37604

Articles Editor, Real Property

Kathleen K. Law

Nyemaster Goode PC

700 Walnut Street, Suite 1600 Des Moines, IA 50309-3800 kklaw@nyemaster.com

Articles Editor, Trust and Estate

Michael A. Sneeringer

Porter Wright Morris & Arthur LLP

9132 Strada Place, 3rd Floor Naples, FL 34108

MSneeringer@porterwright.com

Senior Associate Articles Editors

Thomas M. Featherston Jr.

Michael J. Glazerman

Brent C. Shaffer

Associate Articles Editors

Robert C. Barton

Travis A. Beaton

Kevin G. Bender

Jennifer E. Okcular

Heidi G. Robertson

Aaron Schwabach

Bruce A. Tannahill

Departments Editor

James C. Smith

Associate Departments Editor

Soo Yeon Lee

Editorial Policy: Probate & Property is designed to assist lawyers practicing in the areas of real estate, wills, trusts, and estates by providing articles and editorial matter written in a readable and informative style. The articles, other editorial content, and advertisements are intended to give up-to-date, practical information that will aid lawyers in giving their clients accurate, prompt, and efficient service.

The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the authors and editors and should not be construed to be those of either the American Bar Association or the Section of Real Property, Trust and Estate Law unless adopted pursuant to the bylaws of the Association. Nothing contained herein is to be considered the rendering of legal or ethical advice for specific cases, and readers are responsible for obtaining such advice from their own legal counsel. These materials and any forms and agreements herein are intended for educational and informational purposes only.

© 2024 American Bar Association. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Contact ABA Copyrights & Contracts, at https://www.americanbar.org/about_the_aba/reprint or via fax at (312) 988-6030, for permission. Printed in the U.S.A.

ABA PUBLISHING

Director

Donna Gollmer

Managing Editor

Erin Johnson Remotigue

Art Director

Andrew O. Alcala

Manager, Production Services

Marisa L’Heureux

Production Coordinator

Scott Lesniak

ADVERTISING SALES AND MEDIA

KITS

Chris Martin

410.584.1905 chris.martin@mci-group.com

Cover

Getty Images

All correspondence and manuscripts should be sent to the editors of Probate & Property

Probate & Property (ISSN: 0164-0372) is published six times a year (in January/February, March/ April, May/June, July/August, September/October, and November/December) as a service to its members by the American Bar Association Section of Real Property, Trust and Estate Law. Editorial, advertising, subscription, and circulation offices: 321 N. Clark Street, Chicago, IL 60654-7598.

The price of an annual subscription for members of the Section of Real Property, Trust and Estate Law is included in their dues and is not deductible therefrom. Any member of the ABA may become a member of the Section of Real Property, Trust and Estate Law by sending annual dues of $95 and an application addressed to the Section; ABA membership is a prerequisite to Section membership. Individuals and institutions not eligible for ABA membership may subscribe to Probate & Property for $150 per year. Requests for subscriptions or back issues should be addressed to: ABA Service Center, American Bar Association, 321 N. Clark Street, Chicago, IL 60654-7598, (800) 285-2221, fax (312) 988-5528, or email orders@americanbar.org.

Periodicals rate postage paid at Chicago, Illinois, and additional mailing offices. Changes of address must reach the magazine office 10 weeks before the next issue date. POSTMASTER: Send change of address notices to Probate & Property, c/o Member Services, American Bar Association, ABA Service Center, 321 N. Clark Street, Chicago, IL 60654-7598.

March/april 2024 3

Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

UNIFORM LAWS UPDATE

The Mortgage Modifications Act Endeavors to Clarify

Patchwork of State Laws

In 2021, the Uniform Law Commission began drafting the Mortgage Modifications Act, which aims to remove uncertainty in the law addressing the making and interpretation of modifications to recorded mortgages. The Mortgage Modifications Act is currently being drafted by a committee consisting of Uniform Law Commissioners, an ABA advisor, and observers from the title insurance, mortgage lending, and property records industries. The act aims to clarify and refine the law by introducing clear parameters for when and how mortgages can be modified and the implications of various types of changes.

Mortgage modifications may be initiated for many reasons, including as a common alternative to foreclosure for both residential homeowners and commercial borrowers. Typical modifications may include extending the loan’s maturity date, changing the interest rate or the method for capitalization of interest, increasing the principal amount of the loan in exchange for additional advances, or adjusting insurance requirements, escrow requirements, or financial covenants. A lender may agree to a modification in response to a borrower’s actual or prospective default on payments or in light of changing conditions in debt markets.

The common law serves as a baseline for mortgage modifications, but there are several gaps in the common law when applied to modern

Uniform

Author: Jane Sternecky, Legislative Counsel,

Uniform Laws Update provides information on uniform and model state laws in development as they apply to property, trust, and estate matters. The editors of Probate & Property welcome information and suggestions from readers.

mortgages. First, the common law does not provide clarity regarding whether the modification of a loan or other obligation secured by a mortgage affects the mortgage’s priority against junior lienholders. Furthermore, the common law is unclear on whether recording a mortgage modification agreement is an adequate basis for maintaining mortgage priority. To complicate matters further, case law indicates that when a modification results in a novation of an obligation that is secured by the mortgage, then the mortgage no longer secures the obligation.

Beyond the common law, each state establishes its own rules for recording mortgages and determining mortgage lien priority. This patchwork of mortgage modification law creates confusion as borrowers move between states and complicates the administration of mortgage loans by national entities. This confusion can result in foreclosure, even when a borrower and lender have agreed to a modification. A uniform law on mortgage modifications would benefit residential and commercial borrowers by providing predictability in transactions and reducing delays associated with mortgage loan modifications. Additionally, the Mortgage

Modifications Act should reduce costs by significantly decreasing the need for a borrower to pay to record an amendment or bear the cost of a title policy endorsement or legal opinion.

This project is a work in progress. As currently drafted, the Mortgage Modifications Act will permit safe harbor modifications of mortgage loans and other transactions secured by a mortgage. Permissible modifications will likely include: (1) extension of the maturity date; (2) decrease in the interest rate of an obligation; (3) modification to the method of calculating interest if it does not increase the rate; (4) change to capitalization of unpaid interest or other unpaid obligations; (5) forgiveness, forbearance, or reduction of principal, interest, or another monetary obligation; (6) addition, modification, or elimination of escrow or reserve requirements; (7) addition or modification of insurance requirements; (8) modification of existing conditions to an advance of funds; (9) addition or modification of an obligor’s financial covenant; and (10) change to the payment amount or schedule. The drafting committee chose to include these modifications as part of the safe harbor because they either are changes that do not affect the priority of a junior interest holder or are changes that are not typically materially prejudicial.

For these safe harbor modifications, the Mortgage Modifications Act plans to ensure that the mortgage will continue to secure the obligation as modified and that the priority of the mortgage will not be affected. Additionally, the act as currently drafted will not require recording of modifications to retain priority and states that a safe harbor modification will not constitute

March/april 2024 4

Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

Benjamin Orzeske, Chief Counsel, Uniform Law Commission, 111 N. Wabash Avenue, Suite 1010, Chicago, IL

Contributing

Laws Update Editor:

60602.

Uniform Law Commission.

a novation. Similarly, senior interests, including tax liens with statutory priority, should not be affected by the modification.

Under the current draft, modifications that occur outside of the safe harbors, such as modifications that increase the principal or interest rate in a way that was not contemplated by the original loan and which would materially prejudice a junior lienholder, will still be governed by existing law. Additionally, the Mortgage Modifications Act will likely defer to state law for the

RPTE BOOKS

required contents of a mortgage agreement, the statute of limitations for enforcing obligations or mortgages, and the procedures for recording.

The Mortgage Modifications Act is expected to be finalized at the Uniform Law Commission’s annual meeting in the summer of 2024 and should be made available for state-level enactment in the fall of 2024.

The Mortgage Modifications Act strives to reduce costs and facilitate modifications to avoid foreclosure whenever feasible. Mortgage

PC: 5431137 | 974 pages

Price: $179.95 / $161.95 (ABA member)

$143.95 (RPTE Section member)

modifications are common, regardless of the economic climate, but they are an especially valuable tool for borrowers and lenders during times of economic uncertainty and turmoil. The final version of the Mortgage Modifications Act could significantly benefit borrowers and prevent unnecessary foreclosures in the event of another financial crisis. The act will aim to provide much-needed clarity for homeowners, commercial borrowers, and all entities involved in the mortgage lending and title industries. n

Insurance Law for Common Interest Communities: Condominiums, Cooperatives, and Homeowners Associations, Second Edition

Francine L. Semaya, Douglas Scott MacGregor, and Kelly A. Prichett

Insurance Law for Common Interest Communities: Condominiums, Cooperatives and Homeowners Associations is an exhaustive insurance primer for both those who are new to insurance coverage law and seasoned professionals seeking new guidance. It offers comprehensive coverage of insurancerelated topics involving common interest communities, discussing and analyzing statutes, court decisions, and insurance policies on those topics and more.

An Estate Planner’s Guide to Qualified Retirement Plan Benefits, Sixth Edition

Louis A. Mezzullo

This ABA bestseller has helped thousands of estate planners understand the complex rules and regulations governing qualified retirement plan distributions and IRAs. Now newly updated, An Estate Planner’s Guide to Qualified Retirement Benefits provides expert and current guidance for structuring benefits from qualified retirement plans and IRAs, consistently relating key distribution issues to current estate planning practice.

PC: 5431127 | 184 pages

Price: $139.95 / $125.95 (ABA member)

$111.95 (RPTE Section member)

March/april 2024 5 UNIFORM LAWS UPDATE

To purchase, please visit ambar.org/rptebooks Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

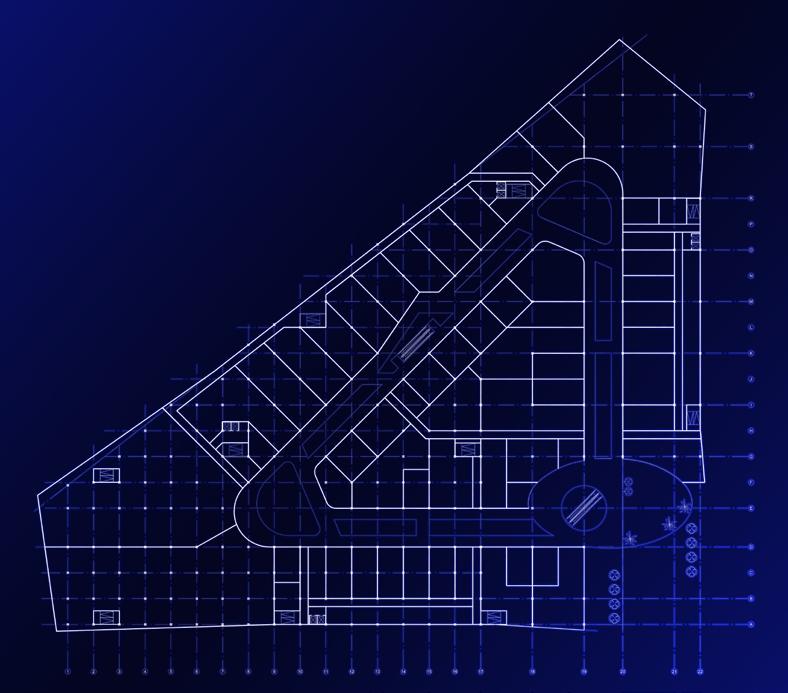

Leases and REAs, COREAs, and Operating Easements Considerations for Drafting and Negotiating

By D. Joshua Crowfoot, Karen M. T. Nashiwa, and Joseph M. Saponaro

Overview of Reciprocal Easement Agreements

A reciprocal easement agreement can take many forms including a COREA (Construction, Operation and Reciprocal Easement Agreement), DOE (Declaration of Easements), OEA (Operation and Easement Agreement), OE (Operating Easement), or ECR (Easements, Covenants, and Restrictions). For the purpose of these materials, all of the foregoing will be collectively referred to as REA(s).

REAs are agreements that set the terms, conditions, and obligations for the easements, restrictions, and covenants between owners of real property and stakeholders with a leasehold interest in the real property to ensure harmony in the development, operations, and maintenance of such real property. REAs can be used in both commercial or residential contexts but typically apply to integrated shopping centers, retail, office, and other mixed-use properties. REAs set forth a uniform standard for the subject real property with respect to construction; maintenance obligations; architectural theme; prohibited, restricted, and exclusive use protections; site plan controls; signage rights; and other operational requirements.

Pertinent Provisions

Here are the most common and pertinent provisions contained in REAs.

Access: The parties to the REA will want to grant and receive reciprocal easements for ingress and egress across parcels to ensure that driveways, walkways, parking lots, lanes, aisles, roadways, and ring roads located on the various tracts allow the parcel owners and their respective employees, customers, and suppliers the ability to travel between the public roads and the subject real property.

Parking: Parking is a key point of consideration for REAs. The parties to the REA grant each other the right for their tenants, customers, employees, and suppliers to park in designated parking areas on the real property subject to the REA. Similar to the access easement, consideration should be given to the rights and limitations on the right to relocate parking areas. An important item to consider is whether each parcel has to be self-sufficient for parking or if one owner will be allowed to count parking on another owner’s parcel to meet

D. Joshua Crowfoot is the managing attorney of Crowfoot Law Firm in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Karen M. T. Nashiwa is the deputy general counsel of Triple Oak Power LLC in Portland, Oregon. Joseph M. Saponaro is the chief operating officer and chief legal counsel of Kohan Retail Investment Group LLC in Great Neck, New York.

March/april 2024 7 Getty Images Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

required parking ratios on the subject real property.

Operation of Common Areas: The definition of “common areas” typically includes, but is not limited to, the following: access roads, driveways, walkways, ring roads, outdoor green spaces and seating areas, lobbies, elevators, escalators, hallways, and other shared or common areas of the property that are available for all tenants, customers, employees, visitors, and others to use throughout the property. The REA should provide the party that controls the common areas of the subject real property, such as the developer or manager, to operate, insure, and maintain the common areas. In addition, the REA should outline each REA party’s responsibility for, and costs related to, maintaining common areas. These collected fees pay for expenses such as upkeep, insurance premiums for common areas, trash removal, cleaning, and lighting. Property owners are typically required to pay taxes relating to their own property and a portion of the taxes pertaining to common areas. In addition, each party is also required to maintain the appearance of the buildings on its property and maintain insurance on the buildings and improvements located on its property.

Term: REAs can be perpetual or for a limited timeframe as may be determined by the types of easements granted and the particular use of such easements. Perpetual easements such as access, stormwater, party wall, and utilities generally last as long as improvements exist on the benefitted tract. For limited timeframe easements, the parties should consider the appropriate time for expiration of easements, such as parking, accent lighting, construction, and the right to use an enclosed mall. For example, the burdened owner might want to consider including language in the REA that gives the burdened owner the right to force an abandonment of certain easements such as an accent lighting easement if the benefitted owner has not used the easement for extended periods of time. Furthermore, language in the REA may want to address

what occurs to certain easements if the intended use of the real property as set forth in the REA ceases to exist.

Signage: REAs can contain provisions pertaining to signage. These provisions address the size, location, lighting, and materials for signage and also provide access details for maintenance and repair. Typically, a common sign such as a monument sign will be located on one party’s property. As a result, the other REA parties will want the owner upon whose tract the sign is located to grant to other owners (and their tenants or designated parties) an easement to cross the burdened tract to access the sign and to maintain its panel on the sign. If a sign does not exist on the effective date of the REA, then there should be language included to address an owner wanting to erect its own monument or pylon sign on the tract of another owner, and the benefitted owner should obtain a construction and maintenance easement to construct and maintain the sign.

Utilities: REAs typically include provisions dealing with the installation, maintenance, relocation, and replacement of utilities on the subject real property, such as electric, gas, cable, water, and sewer. The REA parties grant each other and the applicable utility service providers the right to install, operate, maintain, and repair utility lines on each owner’s tract. The REA should address the burdened owner’s right to consent to the location of the utility facilities or placement of the utilities and should have the right to prohibit utility lines from being installed under its building. As with an access easement, the burdened owner will want to reserve the right to relocate a utility easement, which is a common occurrence, especially with outparcels and redeveloped parcels. The relocation of a utility easement will have the same concerns as the relocation of an access easement. The burdened owner should give the benefitted owner notice, not vacate the existing utility line until the new one is ready to use, and not make it more difficult for the benefitted owner to use the utility line. If an interruption of service is necessary to relocate the

utility line, the interruption should be scheduled with the benefitted parties so their business is not interrupted. If the benefitted owner is working on utility lines on the burdened owner’s tract, the benefitted owner should be required to provide liability insurance and indemnify the burdened owner against any liability claims. The benefitted owner should be required to pay all of the costs of the work and keep the burdened owner’s tract free of liens. The burdened owner will want to require the benefitted owner to perform the work as quickly as possible; to schedule the work with the burdened owner; and, unless it is an emergency, not to perform any utility work during the holiday, back-to-school, or other important shopping periods.

Mortgagee Protection: An REA should contain provisions for the benefit of the lender of any party to the REA. In the event of a default by one party to the REA, the nondefaulting party should be obligated to notify the defaulting party’s lender, if known, and allow such lender to cure the default. In addition, the REA should provide that a breach of any of the covenants or restrictions contained in the REA will not defeat or render invalid the lien of any lender made in good faith and for value as to the shopping center or any part thereof.

Use, Recapture Rights, and Rights of First Offer: Some REAs may require the subject real property to be used for a particular use or, in turn, may restrict certain uses on one parcel to benefit another parcel. If a major retailer that is a party to the REA fails to use its property for a particular use for a specified period of time, then the other parties to the REA may be given the right to purchase the major retailer’s property for its fair market value. The REA may also provide that, in the event either party desires to sell its property to a bona fide third party, the other party will have a “right of first offer” to purchase the selling party’s property. The specific terms and conditions of said right of first offer should be set forth in detail in the REA, which should include a mechanism to determine purchase price and timing of the exercise of such right of first offer.

March/april 2024 8 Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

Construction: Some REAs are executed at the onset of a project or construction phase of a development. In these cases, the parties will want to grant to one another a temporary easement for an adjacent owner to access the tract of an adjacent owner to construct foundations and walls on the tract of the benefitted owner. Such temporary easements may require the workers to be on the burdened tract and provide appurtenant easements pertaining to the construction standards, maintenance obligations, and operations of such project or development. If each owner is not only constructing a building on its tract, but also performing site work, the easement will include the right to install utility lines and grade the benefitted tract. If the developer is doing the site work and the parties are building their own buildings, the parties will want to grant an easement for the site work to the developer and a construction easement to the adjacent owners.

Amendments and Other Considerations: REAs include the mechanism to modify the REA, if necessary. Typically, the REA cannot be amended without the approval of all, or a majority of, the other REA parties. The REA must be clear, however, as to who has this approval right if one party’s property is subsequently subdivided into multiple properties or owned by multiple parties. The ability to grant easements is as important as the ability to not grant easements. The parties will want to establish that the other parties will not have the right to grant similar easements to anyone that is not an owner under the REA. As mentioned above, the parties will also want the right to close off access and parking occasionally to keep the public from gaining prescriptive rights in the burdened owner’s tract. The benefitted owner will want to obtain an agreement from the burdened owner not to install any landscaping, signs, or structures that will interfere with visibility of the benefitted owner’s sign. As with other easements where work is being performed by one owner on the tract of another owner, the burdened owner should require the benefitted owner

to indemnify the burdened owner and maintain liability insurance.

REAs and Priority

REAs are vital real property interests, and the intent of REA parties is that the rights and restrictions contained therein must not be subject to being extinguished by third parties (e.g., lenders). Accordingly, if a security instrument, such as a mortgage, happens to encumber any portion of the property that is intended to be governed by, or subject to, an REA at the time the REA is established, then such security instrument will need to be subordinated to the REA. Likewise, future security instruments encumbering the property must remain subject and subordinate to the REA. This may sound controversial because lenders abhor title encumbrances that are superior to their mortgage interests; however, lenders understand that that the rights in the REA in favor of the encumbered property are often critical to the property in which they have interests, so lenders are comfortable with not having priority over an REA. It helps to think about the concept in reverse. A mortgage lender (or property owner) would not want another lender with a mortgage on another portion of the shopping center to have the right to extinguish the REA if the other lender forecloses (or otherwise exercises its rights) due to a default by the other property owner. As a practice point, when

representing a party obtaining an interest in an existing shopping center that is encumbered by an REA (whether as a buyer or lender), it is important to have the rights under the REA be part of the property insured under the title policy.

How REAs Affect Leases

REAs exist in real estate projects and developments for every type of use— retail, industrial, or office. In the retail context, you find them in a shopping center development. In an office context, you find them in office parks, and in the industrial context, you find them industrial parks. Because REAs are typically seen in a shopping center development, these written materials will focus on the effect of these documents on retail leases.

How REAs Can Restrict a Tenant’s Use

Similar to a COREA, DOE, OEA, declaration, master deed, or covenants, conditions, and restrictions, REAs are documents meant to run with the land and specify in detail (i) the promises that each owner of a parcel of land makes to an owner of an adjacent parcel, (ii) the obligations and duties of each owner of a parcel of land, and (iii) ways in which the development of such parcels will be restricted to accomplish the vision for the development.

REAs are meant to affect the land in perpetuity. Ideally, REAs will accomplish the long-term development goals

March/april 2024 9 Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

SAMPLE LEASE PROVISION GRANTING AN EXCLUSIVE USE THAT PROTECTS LANDLORD

EXCLUSIVES

a. Definitions.

i. “Exclusive Use” shall mean the operation of a [insert use].

ii. “Competitor” shall mean a business not affili- ated with Tenant that uses its premises in the Retail Center primarily for the Exclusive Use; provided, however, it shall exclude the following:

A. Any business which engages in the Exclusive Use but is not specifically permitted to do so in its lease;

B. Any anchor store or any store containing a floor area in excess of [insert square footage];

C. Any business occupying its premises directly or as an assignee, subtenant, or licensee under:

1) A lease that was executed prior to the execu- tion of this Lease but that is in effect as of the date of execution of this Lease (an “Existing Lease”);

2) A renewal or extension of an Existing Lease;

3) A new lease that is executed by a business that leased or occupied premises in the Retail Center directly or indirectly under an Existing Lease (a “New Lease”); or

4) A renewal or extension of a New Lease.

D. Any store containing a floor area less than [insert square footage];

E. If the premises currently occupied by [insert name of existing tenant] shall cease to be used primarily for the Exclusive Use, [insert number] additional store[s] (which may be located any- where within the Retail Center) containing a floor area not exceeding [insert square footage]; and

F. Any business which devotes less than [insert number]% of the sales area of such premises to the Exclusive Use or on an annual basis, less than [insert number]% of the gross sales from such premises are generated by the Exclusive Use.

b. Exclusive Use Remedy. Notwithstanding anything contained herein to the contrary, if Landlord shall rent space in the Retail Center in the designated area shown on Exhibit [insert number] (the “Excluded Area”) to a Competi- tor (as defined below) for the Exclusive Use (as defined below) during the [insert period of time, i.e., first five years of the Term], then Tenant’s sole and exclusive remedy shall be a reduction in monthly Minimum Rent to [insert agreed-upon

amount] from the date Tenant notifies Landlord of such violation until such violation is cured. This rem- edy shall be exercised upon [insert number] days’ prior written notice that must be given to Landlord within [insert number] days after the Competitor opens for business in the Excluded Area.

c. Primary Use. The Premises shall not be deemed to be used primarily for the Exclusive Use unless:

i. More than [insert number]% of the sales area of the Premises is devoted to the Exclusive Use; and

ii. On an annual basis, more than [insert number]% of the gross sales from the Premises are generated by the Exclusive Use.

d. Exclusive Becomes Void. This Paragraph shall automatically become void if:

i. Tenant defaults under any provision of this Lease, including, but not limited to, the radius restriction set out in Paragraph [insert number] hereof;

ii. Tenant is not open and continuously, actively, and diligently using and occupying the entire Premises pursuant to the terms and conditions of this Lease;

iii. Tenant assigns its rights under this Lease in whole or in part or sublets all or any portion of the Premises;

iv. The Tenant’s average monthly gross sales over [insert number] consecutive months is an amount which is below $[insert amount];

v. A sale of Tenant, a transfer of corporate shares of Tenant, or a transfer of any partnership or mem- bership interest of Tenant occurs that would entitle Landlord to terminate this Lease pursuant to Para- graph [insert number] herein (regardless of whether Landlord actually exercises such right to terminate);

vi. The Premises ceases to be used primarily for the Exclusive Use; or

vii. Tenant fails to give Landlord the notice required by Paragraph (b) hereof within the time period pro- vided therein.

e. Primary Use. The Premises shall not be deemed to be used primarily for the Exclusive Use unless:

i. More than [insert number]% of the sales area of the Premises is devoted to the Exclusive Use; and

ii. On an annual basis, more than [insert number]% of the gross sales from the Premises are generated by the Exclusive Use.

March/april 2024 10 Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

of the developer/co-owner but also ensure compatibility of future tenants with the use of the major retailer/coowner that also has a vested interest in seeing the retail development succeed. Ultimately, a thriving retail center will drive traffic to the major retailer, and the foot traffic that the major retailer experiences will inevitably spill over into the physical locations of nearby tenants in the retail center.

The provisions of REAs address the mechanics of how the retail center will develop, how it will operate, and how the co-owners will divvy up the duties and obligations that come with owning the development.

Invariably, REAs will establish a general use for the development. For example, an REA for a shopping center might contain the following general use language: “No part of the Shopping Center shall be used for other than retail sales or services, offices, restaurants, information centers, or other commercial purposes.” In addition, REAs will set out a list of prohibited uses for the retail center. Although the list of prohibited uses can vary from one retail center to the next, these are the most common uses that are banned in a retail center:

• Any use that amounts to a public or private nuisance;

• Any use that allows noise or sound that is objectionable due to intermittence, beat, frequency, shrillness, or loudness;

• Any use that allows any obnoxious odor;

• Any use that produces an excessive quantity of dust, dirt, or fly ash (the parties may want to exclude the sale of soils, fertilizers, or other garden materials or building materials in containers if incident to the operating of a home improvement or general merchandise store; typically, a major retailer will want to carve this out from the list of prohibited uses);

• Any use that results in fire, explosion, or other damaging or dangerous hazard, including the storage, display or sale of

explosives or fireworks (depending on the major retailer, the parties may want to carve out that the sale of gasoline is an acceptable use);

• Any use allowing a trailer or mobile home, labor camp, junk yard, stock yard, or animal raising [the parties may want to carve out pet shops, dog grooming stores, or doggie “day cares” (or not) from this use];

• Any use allowing the drilling for or removal of subsurface substances;

• Any use allowing the dumping of garbage or refuse, other than in enclosed receptacles intended for such purpose;

• A cemetery, veterinary hospital, mortuary, or similar service establishment;

• A car washing establishment;

• A shop providing automobile body and fender repair work;

• Any use allowing automobile, truck, trailer, or recreational vehicle sales, leasing, or display that is not entirely conducted inside of a building;

• Any church, synagogue, temple, mosque, or other place of worship;

• Any fire sale, flea market, bankruptcy sale (unless pursuant to a court order), or auction operation;

• Any apartment, home, or other residential use or any hotel, motel, or other lodging facilities;

• Any theater, playhouse, cinema, or movie theater;

• Any bar or discotheque;

• Any school, training, educational, or day care facility, including, but not limited to, beauty schools, barber colleges, nursery schools, diet centers, reading rooms, places of instruction, or other operations catering primarily to students or trainees rather than to customers;

• Any sexually oriented business or cannabis establishment;

• A hospital or clinic; or

• A convenience store.

Potential tenants looking to lease in the retail center will want to review

the REA to make sure there is no outright ban for the expected use of their space. Prohibited uses are usually listed altogether in one paragraph and easy to locate. What can be more difficult to locate are uses that the major retailer might want to reserve for itself that may overlap with an exclusive for which the potential tenant wants an exclusive—say the sale of coffee or the sale of pizza. Typically, the way this gets handled is that the REA will be drafted so the major retailer promises to never have more than a certain percentage of its sales (for example, three percent) be attributed to the sale of pizza or coffee.

What can be a trickier situation is whether the major retailer—say a Walmart—will be allowed to have a small store within its location—such as Starbucks, Subway, an optometrist, or a nail salon, for example—that may compete with a future tenant. This is a major negotiating point that will have to be decided between the developer/ co-owner and the major retailer/coowner when drafting the REA. This is also an issue when a potential tenant is performing its due diligence on the retail center and reviewing the REA for such provisions that allow the major retailer to contain a possible competitor within its walls.

If you represent a developer/coowner of a retail center, one way to protect your client from unwanted litigation that asserts the violation of a tenant’s exclusive use is to do the following in your form lease:

Ensure your lease sets limits. The landlord’s form lease should impose the following limitations with respect to granting exclusives to any tenant:

• Limit the remedy for an exclusive violation to a lower amount of rent.

• Limit the term of the exclusive (i.e., set an “expiration date” for the exclusive).

• Limit the applicability of the exclusive to a certain area of the retail center.

• Limit the exclusive to the tenant’s “primary” use.

March/april 2024 11 Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

Give the landlord the ability to eliminate the exclusive. The landlord should be able to eliminate an existing tenant’s exclusive in the event any of the following occurs during the term of the tenant’s lease:

• Tenant’s gross sales fall below a certain amount.

• Tenant assigns or sublets a portion of or the entire premises.

• Tenant triggers an event of default under the lease.

• Tenant stops using the exclusive use.

• Tenant establishes a competing business nearby.

• Tenant fails to continuously operate its business.

• Tenant does not notify the landlord of a violation of the exclusive in a timely manner.

Except certain tenants that would otherwise be a competing business. For example:

• Rogue tenants.

• Anchor tenants.

• Existing tenants.

• An assignee or subtenant of an existing tenant.

• Small tenants.

• Tenants that replace an existing tenant but are smaller in size.

• Tenants who violate the exclusive use on an incidental basis.

A sample lease provision granting an exclusive use that protects landlord is provided on page 10.

How REAs Can Affect Where a Tenant Can Build

REAs provide the rules and mechanics for a developer/co-owner and a major retailer/co-owner to develop the property. Ideally, the REAs will provide the owners of the development with flexibility to develop the retail center as they please. However, potential tenants of the retail center often want the landlord to make assurances in the site plan that can restrict the landlord’s development.

If not addressed ahead of time by the parties, unresolved issues with the landlord’s site plan can be flashpoints for lease disputes.

With the site plan, a tenant typically wants a representation from the landlord that the final development will be the same as the proposed development, and the site plan is a complete and accurate depiction of all matters. In contrast, a landlord will want minimal detail and maximum leeway to change the site plan, if necessary.

Common areas of dispute are the following:

• Landlord makes material changes to the site plan without tenant’s consent;

• Landlord’s site plan ends up significantly reducing the amount of parking to tenant;

• Landlord’s development under the REA impedes the visibility that the tenant expected to have; and

• Changes to the common areas or other development move the tenant to an undesirable location or cause its existing location to be undesirable.

Therefore, the parties will usually agree that the landlord’s changes to the site plan will NOT:

• Be substantial;

• Reduce parking below a specified ratio;

• Affect the visibility of the premises or access to them;

• Put any other tenant’s store line in front of the premises; or

• Remove the tenant from a specified proximity to proposed anchor tenants, retail center entrances, or parking areas.

When negotiating a retail lease in a retail center that is the subject of an REA, the tenant will want the following designated on a site plan (that is dated and scaled):

1. The perimeter of the shopping center;

2. The common areas;

3. The number of spaces for tenants;

4. The parking ratio and angle of striping;

5. The location of pylons, monuments, planters, and other barriers;

6. The outparcels;

7. The parking areas reserved for the tenant or other tenants, or designated for employees;

8. The location of handicapped or loading-zone spaces;

9. The size of the spaces; and

10. Entrances and exits, curb cuts, loading areas, means of access to the premises, and the size and location of buildings.

Cases have been litigated over reneged promises pertaining to parking ratios and visibility of a tenant’s premises. The parties can typically avoid disagreements ahead of time by giving

March/april 2024 12 Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

the tenant an unobstructed vista on the site plan or a sight line easement on the site plan. Tenants will want the vista or sight line easement to be as large as possible, all the way to the nearest major thoroughfare. Landlords will want to limit the vista or sight line easement to areas directly in front of the premises, if possible.

Tenants will want to make sure their site plans show where all the signs will be located in the development and refer to their sign criteria set forth as an exhibit to the lease. This is important because a misplaced sign can impair visibility of the tenant’s premises.

The site plan should show outparcels, too. A building built on an outparcel may obstruct visibility of the tenant’s premises. In addition, the demand for parking by the owner of an outparcel may exceed the supply of the outparcel (i.e., restrictions imposed by building or zoning code). In situations like this, the developer/co-owner will typically negotiate with the buyer of the outparcel for a cross-parking arrangement. The problem with such an arrangement is that overflow parking from the outparcel may impair the parking reserved or intended for the tenant.

As a general rule, landlords should disclaim any promise that the site plan will not change during the term of the lease. And landlords should ensure that any promises they make to tenants regarding their physical requirements for the premises should not conflict with what is stated in the REA.

Consent to Changes in the REA

An important point of contention between a landlord and tenant is whether a tenant should be allowed to prevent a landlord from making alterations or improvements in the retail center pursuant to the REA that could hurt the tenant’s business. Whether a landlord can refuse to provide such a right to the tenant largely turns on the tenant’s size.

Anchor Tenants. Anchor tenants will have the most leverage in any lease negotiation with a landlord. Generally, such tenants have the clout to negotiate

a provision that allows them to prevent the landlord from amending the REA without its consent. As an example, an anchor tenant would certainly want the right to preclude the landlord from making revisions to the REA that would allow it to change the retail center from a “lifestyle” center to that of an “outlet” center.

Midsize Tenants. For midsize tenants, a landlord can offer that it must obtain the tenant’s consent for any changes to the REA that would “unreasonably adversely” affect the tenant’s rights or obligations under the lease. This consent would apply to any changes that unreasonably interfere with the tenant’s use or enjoyment of the retail center.

Small Tenants. For small tenants, a landlord can offer that it must obtain the tenant’s consent for any changes to the REA that would “materially adversely” impact the tenant’s rights or obligations under the lease, which is a tougher standard than “unreasonably adversely.” The landlord will want to ensure that it has the final determination regarding what is “materially adverse.” If possible, the landlord can state in the lease specific instances where the “materially adversely” standard is met. For example, such changes to the REA would have to be changes that affect visibility, access, or economic provisions of the lease. Furthermore, the landlord wants to ensure that the tenant’s consent cannot be unreasonably withheld, conditioned, or delayed.

A sample lease provision using the “materially adversely” standard is as follows:

Landlord shall not amend, modify, or terminate the [insert name of REA] without the prior written consent of Tenant if such amendment,

modification, or termination would materially adversely affect in Landlord’s sole opinion any rights or obligations of Tenant under the Lease. Tenant’s consent shall not be unreasonably withheld, conditioned, or delayed.

The lease should also consider the kind of changes that require the consent of the tenant before the landlord can amend the REA. Tenants will want landlords to require their consent for as broad a category of changes as the landlord will allow, but the landlord will want to narrow down the types of changes for which it will need to obtain the tenant’s consent. In fact, it would behoove the landlord to specifically list the specific changes that will require the tenant’s consent, such as changes that will affect the amount of parking directly in front of the tenant’s premises. Landlords would also be wise to provide the tenant a specific period of time to respond to any proposed changes to the REA. If the tenant does not respond prior to the expiration of the deadline to do so, then its rights to consent to such changes should be waived.

If the landlord deems it necessary to revise the terms of an REA, it is not limited to giving the tenant a consent right to such changes. In lieu of giving the tenant a consent right, it can offer other remedies, such as the right to receive rent abatement or the right to terminate the lease. The former remedy is less severe than the latter. If rent abatement is offered, the landlord should require the tenant to provide proof that such changes to the REA have decreased its sales prior to providing a rent abatement.

March/april 2024 13 Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

Ways to Ensure Leases Do Not Trigger Violations of REAs

When parties negotiate a commercial lease, it behooves both landlord and tenant to ensure that the terms of the lease not conflict with the terms of the REA. Ensuring agreement between the two documents gives the tenant clarity and prevents a costly lawsuit to the landlord. Landlords do not want to add provisions to the lease that inadvertently violate the REA.

For example, assume the REA dictates where the retail center’s entrances and exits will be located. As part of lease negotiations, however, the landlord makes a concession to an important, midsize tenant that it will move the entrance close to the midsize tenant’s space—a location that would violate the terms of the REA.

Once the parties sign the lease and the issue is brought to the landlord later, the landlord is in an impossible situation. If the landlord moves the entrance close to the tenant’s space, a third party will sue the landlord for violating the REA. If the landlord moves the entrance to the location designated in the REA, then the tenant will sue the landlord for violating the lease.

The parties can protect themselves by doing three things.

First, the parties should ensure the terms of the lease and REAs are consistent with one another. If there is an inconsistency, the landlord should modify or delete the offending lease clause and notify the tenant of the reasons for doing so.

Second, the lease should contain language that alerts the tenant during its review of the lease that an REA encumbers the real property on which the premises will be located. The lease should state that it is “subject to” the terms and provisions of the REA, as it may be modified or amended. By including the “subject to” language, the parties ensure that the REA must be followed if the REA ever conflicts with the lease.

A sample provision could read as follows:

Landlord and [insert name of major retailer] (the “Anchor”) have entered into a [insert name of REA], dated [insert date]

(the “REA”). This Lease is in all respects subject to the terms and provisions of the REA and to all modifications, amendments, and revisions thereto.

A sophisticated tenant will demand that the landlord modify the lease

language to limit the landlord’s ability to enter into modifications, amendments, and revisions to the REA on its own. The landlord will likely have to agree to the following additional language: “Notwithstanding the foregoing, Landlord shall not enter into any modifications, amendments, or revisions of the REA if they would materially adversely increase Tenant’s obligations under this Lease.”

Third, the tenant can require that the tenant’s business comply with the REA. The tenant should be obligated to conduct its business in a way that will not cause it or the landlord to violate the REA. The lease should state that the tenant must maintain and conduct its business in strict compliance with the REA, as well as any laws, rules, regulations, and orders of insurance underwriters.

A sample provision could read as follows:

Tenant shall at all times maintain and conduct its business, so far as the same relates to Tenant’s use and occupancy of the Premises, in a lawful manner, and in strict compliance with any maintenance or easement agreement, including but not limited to the REA, all governmental laws, rules, regulations, and orders and provisions of insurance underwriters applicable to the business of Tenant conducted in and upon the Premises, including those with respect to storage, handling, discharge, and transport of any pollutant, contaminant, or hazardous, toxic, or dangerous substance.

A sample form of REA appears following this article.

Conclusion

Practitioners are well advised to understand the basic considerations of landlords and tenants in REAs and the provisions that should be included in such documents. n

March/april 2024 14 Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

Sample REA

THIS RECIPROCAL EASEMENT

AGREEMENT (“Agreement”) is made and entered into as of ______________, 202__, by and between ______________________________, a(n) __________ limited liability company (“Primary Lot Owner”), and _________________, a(n) ___________ limited liability company (“Outparcel Lot Owner”), with reference to the following facts:

WHEREAS, Primary Lot Owner is the owner of the real property consisting of a shopping center situated in the Township of ____________, County of __________, State of __________, consisting of the parcel legally described on Exhibit A attached hereto and made a part hereof (“Primary Lot”), and Outparcel Lot Owner is the Owner of the adjoining parcel of real property described on Exhibit B attached hereto and made a part hereof (“Outparcel Lot”). A depiction of the entire shopping center including the Primary Lot and the Outparcel Lot is attached hereto as Exhibit C.

WHEREAS, Primary Lot Owner and Outparcel Lot Owner desire to grant certain reciprocal easements upon the Primary Lot and the Outparcel Lot (individually, a “Parcel” and together, the “Parcels”), and to establish certain covenants, conditions, and restrictions with respect to the Parcels for their benefit and for the mutual and reciprocal benefit of the Parcels and the present and future owners and occupants thereof, on the terms and conditions hereinafter set forth.

NOW, THEREFORE, in consideration of the above premises and of the covenants herein contained, Primary Lot Owner and Outparcel Lot Owner hereby establish, declare, covenant, and agree that the Parcels and all present and future owners and occupants of the Parcels shall be and hereby are subject to the terms, covenants, easements, restrictions, and conditions hereinafter set forth in this Agreement so that said Parcels shall be maintained, kept, sold, and used in full compliance with and subject to this Agreement and, in connection therewith, Primary Lot Owner and Outparcel Lot Owner on their behalf and their successors and assigns covenant and agree as follows:

1. Definitions. For purposes hereof:

(a) The term “Owner” or “Owners” shall mean Primary Lot Owner and Outparcel Lot Owner and any and all successors or assigns of such persons as the owner or owners of fee simple title to all or any portion of the real property covered hereby, whether by sale, assignment, inheritance, operation of law, trustee’s sale, foreclosure, or otherwise, but not including the holder of any lien or encumbrance on such real property. Further, Owner shall include any tenant of the Outparcel Lot that has a recorded memorandum of lease evidencing such tenancy.

(b) The term “Parcel” or “Parcels” shall mean the Primary Lot and the Outparcel Lot, and any permitted future subdivision(s) of either.

(c) The term “Permittees” shall mean the respective occupant(s), employees, agents, contractors, customers, invitees, and licensees of (i) the Owner of such Parcel, and/or (ii) such tenant(s) or occupant(s).

(d) The term “Common Areas” shall mean those portions of the Parcels intended for the nonexclusive use of a Parcel, which may be either unimproved or improved such as (without limitation) parking areas, landscaped areas, ring roads, driveways, roadways, walkways,

light standards, curbing, paving, entrances, exits, and other similar nonexclusive exterior site improvements, including, without limitation, all portions of Mall Drive.

2. Easements.

2.1. Reciprocal Access Easements. The Owners grant to each other and the subsequent Owners of their respective Parcels an easement over and across all portions of each Parcel constituting a part of the Common Areas of such Parcels, as they exist from time to time, for nonexclusive right-of-way access and parking, for the purpose of pedestrian and vehicular ingress, egress, and parking over all access and entrance drives and parking areas of their respective Parcels.

2.2. Additional Utility Easements. The Owners agree to grant each other and the subsequent Owners of their respective Parcels an easement over and across all portions of each Parcel constituting a part of the Common Areas of such Parcels, as they exist from time to time, for utilities such as electricity, gas, water, cable, telephone, storm sewer, and sanitary sewer (collectively, the “Utilities” or individually, a “Utility”), provided that such Utilities and such easements shall not have a material adverse effect on the use or operation of the Parcels burdened by such easements. Each Owner shall be entitled, on reasonable notice to the Owner of the other Parcel, to enter upon such other Parcel at reasonable times and without unreasonable interference with the use and enjoyment of such Parcel, to maintain, repair and replace the Utilities, as necessary. Notwithstanding the foregoing, if repairs are required because of the negligence or willful misconduct of an Owner or Permittee, or if the event necessitating the repairs occurs on such Owner’s Parcel only, such repairs shall be the sole responsibility of such Owner, including utilities, lines, and connections, running beneath an Owner’s Parcel, and such Owner shall promptly commence such repairs and pursue such repairs diligently to completion. If the aforesaid portion of a Utility is damaged by fire or other casualty, such Utility shall be repaired and restored by the Owner of the Parcel with the damaged Utility unless all of the parties who use such Utility otherwise agree in writing. Notwithstanding anything herein to the contrary, the Primary Lot Owner shall have the right to expand, modify, renovate, or relocate the Utilities that are located on the Primary Lot, at the sole expense of the Primary Lot Owner, which expansion, modification, renovation, or relocation shall be done in a manner as not to materially disrupt the service provided by such Utility to the Outparcel Lot, and any such expansion, modification, renovation, or relocation shall only occur on the Primary Lot.

2.3. Drainage. Primary Lot Owner grants to Outparcel Lot Owner a nonexclusive easement and license, appurtenant to the Outparcel Lot, to tap into and use the storm sewer lines and related facilities located in the Common Areas of the Primary Lot for the purpose of draining any and all surface water runoff from the Outparcel Lot and the improvements which may, from time to time, be located on the Outparcel Lot.

March/april 2024 15 Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

2.4. Indemnification. Each Owner having rights with respect to an easement granted herein shall indemnify and hold the Owner whose Parcel is subject to the easement harmless from and against all claims, liabilities, and expenses (including reasonable attorney fees) relating to accidents, injuries, loss, or damage of or to any person or property arising from the negligent, intentional, or willful acts or omissions caused by the other Owner, its contractors, employees, agents, or others acting on behalf of such Owner, including, and without limitation, any breach of the Prohibited and Restricted Uses (as defined hereinafter) as provided on Exhibit D, which contains all of the restricted uses applicable to the Outparcel Lot.

2.5. Insurance. Each Owner shall maintain for its Parcel, or cause such Owner’s Permittee to maintain, at all times beginning on the date this Agreement is recorded, and ending no earlier than the expiration or earlier termination of this Agreement, a commercial general liability policy or its equivalent, including coverage for contractual liability for personal injury. Such insurance to be carried by each Owner shall have minimum limits of not less than $2,000,000.00 in respect of any one occurrence and $2,000,000.00 with respect to property damage occurring in, on, or about the Owner’s Parcel, and $5,000,000.00 general aggregate. Each Owner shall maintain workers’ compensation and employers’ liability insurance covering its employees as required by law in the State of __________ in an amount not less than $1,000,000.00 in respect of loss or damage to property, in the amount of not less than $1,000,000.00 per disease and in the amount of not less than $1,000,000.00 per disease aggregate. An Owner or such Owner’s Permittee shall have the right to satisfy its obligations regarding the foregoing insurance by way of self-insurance provided such Owner or such Owner’s Permittee maintains a tangible net worth of at least Fifty Million Dollars ($50,000,000.00). Upon the request of any other Owner, such self-insuring Owner or Permittee shall furnish a letter certifying that such party has elected to self-insure and shall provide financial statements, prepared in accordance with GAAP consistently applied, outlining such party’s then-current net worth. The foregoing insurance coverage amounts and self-insurance net worth requirement amounts may be adjusted from time to time to a commercially reasonable level as mutually agreed by the Owners.

2.6. Common Areas. The Owners shall have the right to block, close, alter, change, or remove the Common Areas located on their respective Parcels, so long as (a) the existing access drives depicted on Exhibit E attached hereto are not adversely changed and (b) the number of parking spaces remaining on the affected Parcel shall comply with all applicable laws and regulations.

2.7.

Reasonable Use of Easements

(a) The easements herein above granted shall be used and enjoyed by each Owner and its Permittees in such a manner so as not to unreasonably interfere with, obstruct, or delay the conduct and operations of the business of any other Owner or its Permittees at any time conducted on its Parcel, including, without limitation, public access to and from said business, and the receipt or delivery of merchandise in connection therewith. If

an Owner is required to perform an activity in the easement area, including any Common Areas, which may interfere with, obstruct, or delay the conduct and operations of the business of any other Owner or its Permittees at any time conducted on its Parcel, such Owner shall use its best efforts to diligently prosecute to completion any such activity.

(b) Once commenced, any work undertaken in reliance upon an easement granted herein shall be diligently prosecuted to completion so as to minimize any interference with the business of any other Owner and its Permittees. The Owner undertaking such work shall with due diligence

repair at its sole cost and expense any and all damage caused by such work and restore the affected portion of the Parcel upon which such work is performed to a condition that is equal to or better than the condition that existed prior to the commencement of such work. In addition, the Owner undertaking such work shall pay all costs and expenses associated therewith. Notwithstanding the foregoing or anything contained in this Agreement to the contrary, the Owner(s) of a Parcel and its/their Permittees shall in no event undertake any work described in this paragraph (except normal minor repairs in the ordinary course that do not interfere with the businesses) on another Parcel that is not of an emergency nature unless the Owner of that Parcel and its Permittee(s) consent in writing thereto, which consent shall not be unreasonably withheld or delayed.

3. Maintenance of Mall Drive and Mall Ring Road. The Primary Lot Owner will maintain or cause to be maintained the ring road (i.e., Mall Drive and Mall Ring Road as shown on the Site Plan attached hereto as Exhibit E), which provides access to the Outparcel Lot, in good order, condition, and repair and in full compliance with all applicable laws and regulations (including, without limitation, snow removal and customary repairs). At no time will the Primary Lot Owner be responsible for any maintenance, including, but not limited to, snow removal, striping, and resurfacing, on the Outparcel Lot, including Common Areas located thereon. The Outparcel Lot Owner will pay to the Owner of the Primary Lot a sum of ____________ and 00/100 Dollars ($______,000.00) annually for the maintenance of the ring road. The ring road maintenance expense will increase by two percent (2%) every five (5) years thereafter and shall be payable in equal monthly advance installments on or before the first day of each month. If the ring road maintenance expense is past due and not paid within ten (10) days after the Outparcel Lot Owner receives written notice thereof from the Primary Lot Owner, it shall thereafter bear interest at the rate of ten percent (10%) per annum until paid in full, or the maximum rate allowed by law, whichever is less.

OR Maintenance of Common Areas

. The Owner of the Primary Lot will operate and maintain or cause to be operated and maintained all Common Areas on the Parcels in good order, condition, and repair and in full compliance with all applicable laws and regulations with respect to the Common Areas. The Owner of the Outparcel Lot shall pay (or shall cause payment to be made to) the Owner of the Primary Lot a “Common Area Charge” in the amount of ______________ per annum to reimburse the Owner of the Primary Lot for the cost to maintain, operate, and repair the Common Areas. [In no event shall the Common Area Charge exceed __________Dollars ($________.___).] The Owner of the Outparcel Lot agrees to pay

March/april 2024 16 Published in Probate & Property, Volume 38, No 2 © 2024 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

to the Owner of the Primary Lot the Common Area Charge in twelve (12) equal monthly installments in advance of the first day of each calendar month. If the Common Area Charge is past due and not paid within five (5) days after the Owner of the Outparcel Lot’s written notice thereof, it shall be subject to a late payment fee equal to five percent (5%) of the amount due and shall thereafter bear interest at the rate of ten percent (10%) per annum until paid in full.

4. Further Subdivision. Subject to the satisfaction of all requirements imposed by, and the receipt of all approvals from, any governmental body to do so, the Primary Lot or the Outparcel Lot may be subdivided or otherwise reconfigured by its Owner; provided, however, that any such subdivision or reconfiguration shall not materially and adversely impede and impair access to the Outparcel Lot. The Owner of any subdivided or reconfigured parcel shall immediately become and remain subject to the duties, obligations, and liabilities with respect to the other subdivided or reconfigured parcels within the Parcel so subdivided or reconfigured and, with respect to the other Parcel(s), shall have the rights and benefits of this Agreement as though such reconfigured parcel had been originally described herein. Further, the Owner of each such subdivided or reconfigured parcel shall be relieved of any further obligation hereunder with respect to that portion of the Parcel so subdivided or reconfigured not owned by it and shall continue to be obligated to the other Owners hereunder only with respect to that portion of the original Parcel it retains.

5. No Rights in Public; No Implied Easements. Nothing contained herein shall be construed as creating any rights in the general public or as dedicating for public use any portion of any Parcel. No easements, except those expressly set forth in Section 2, shall be implied by this Agreement.

6. Exclusives, Prohibited Uses, and Restrictions. The Parcels shall be subject to the exclusives, prohibited uses and restrictions (collectively “Prohibited and Restricted Uses”) set forth in Exhibit D, provided that (i) the Prohibited and Restricted Uses contained in the leases referenced in Exhibit D shall only apply so long as the leases containing such Prohibited and Restricted Uses remain in full force and effect and (ii) only the Owner of the Parcel containing the Lease with the applicable Prohibited and Restricted Uses and the Declarant shall be entitled to enforce such Prohibited and Restricted Uses.

7. Remedies. In the event of a breach or threatened breach by any Owner or its Permittees of any of the terms, covenants, restrictions, or conditions hereof, the other Owner(s) shall be entitled forthwith to full and adequate relief by injunction and/ or all such other available legal and equitable remedies from the consequences of such breach, including payment of any amounts due and/or specific performance. Notwithstanding the foregoing to the contrary, no breach hereunder shall entitle any Owner to cancel, rescind, or otherwise terminate this Agreement. No breach hereunder shall defeat or render invalid the lien of any mortgage upon any Parcel made in good faith for value, but the easements, covenants, conditions, and restrictions hereof shall be binding upon and effective against any Owner of such Parcel covered hereby whose title thereto is acquired by