The first six months of this year have been some of the most disruptive I have ever known, as perhaps predictably the transition out of Covid throws up all sorts of problems and stresses. Many people are still working incredibly hard, leading to online debate about whether mass staff burnout is imminent. Some are still getting ill. Many are trying to get out and enjoy their renewed freedoms, leading to a larger proportion of people being away than I can ever remember. Some have taken the opportunity to reconsider their career, or their retirement. And others have returned to jobs from ‘Covid emergency’ roles of various kinds and are now playing catch-up. It’s not been easy getting people to convene, let alone to make things happen, and that’s without the backdrop of war, severe strains on public budgets, and rising food and energy prices. It does all feel quite relentless.

Unsurprisingly then, we felt we needed a lighter theme for The Geographer for this autumn. The great thing about geography is that it is so universal that it can easily provide the scope for this diversity. Working with Geographer Royal for Scotland Professor Jo Sharp, Dr Cheryl McGeachan, and leading crime writer Val McDermid, we explore in this magazine the importance of the settings of crime stories, so critical to any narrative. Not only does landscape drive atmosphere within fiction, but fiction can play a very significant role in how we perceive and understand landscape, both real and imagined.

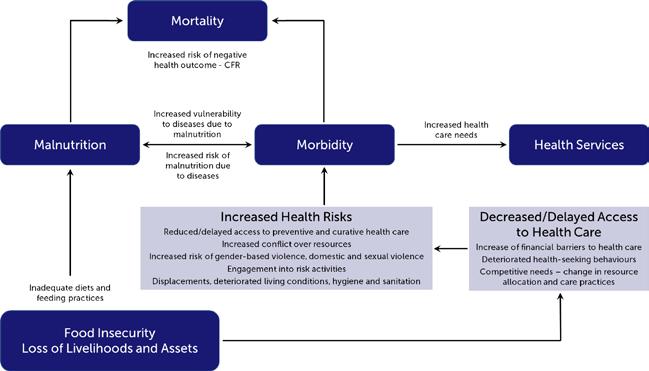

We are grateful for their help, and to the many authors who have contributed to this edition. Of course, we didn’t feel we could ignore all of the current global concerns, so we have features on global food insecurity, a look into recent heatwaves and future national parks, and even some guidance on how to spend a trillion dollars, alongside an interview with outgoing President Iain Stewart, and a short insight into RSGS Board members. We hope you enjoy reading this magazine, and we look forward to seeing many of you again as the face-toface talks kick off again around Scotland, beginning on 19th September.

RSGS, Lord John Murray House, 15-19 North Port, Perth, PH1 5LU tel: 01738 455050 email: enquiries@rsgs.org www.rsgs.org

Charity registered in Scotland no SC015599

The views expressed in this newsletter are not necessarily those of the RSGS.

Cover image: ‘Crime scene’ at the Fair Maid’s House. © RSGS

Masthead image: Crime fiction collection. © Euan Robinson

RSGS: a better way to see the world

In June, our Chief Executive received an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Stirling. Mike Robinson was recognised for his outstanding commitment to delivering and embedding climate solutions to help protect the world, through driving legislation, informing policy, and educating thousands in climate and geographical understanding. At the presentation ceremony, he commented, “I am absolutely delighted to accept this Honorary Doctorate. As a graduate of Stirling it is an especial honour; indeed, it is an important institution in our family – I met my wife at Stirling and my son is also now a student, so it is very close to my heart. I could not be more pleased.”

We are delighted to announce that Mungo Park Medallist Doug Allan will speak for RSGS at a special one-off event at Perth Concert Hall on Wednesday 21st December 2022! The Scottish wildlife cameraman and photographer, best known for his work in polar regions and underwater, will share some of his amazing experiences from throughout his life and career. Tickets are £15 for RSGS members, £10 for students and under-18s, and £20 for general admission. These are likely to sell fast, so please call 01738 621031 or visit www.horsecross.co.uk to secure your place.

book your tickets now

RSGS welcomed its newest member of staff at the end of July. In the role of Deputy Chief Executive, Ross McKenzie will initially focus on strengthening and developing partnerships to ensure that as many people as possible can engage with the Climate Solutions programme. Ross has 15 years’ experience working in the charity and sustainable development sectors, and brings a wealth of programme design, fundraising, and operational management experience. He previously worked for Raleigh International, which included many years working overseas in Tanzania, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Nepal, implementing programmes focused on water, sanitation and hygiene, livelihoods, natural resource management, and youth leadership. In the months prior to joining RSGS, Ross travelled through South America and cycled the ‘El Camino’ pilgrimage from Pamplona to Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

Starting in September, we are delighted to be returning to live talks at our 13 Local Groups across Scotland. Our 2022 23 Inspiring People talks programme features a stellar line-up of speakers, all with incredible stories to share; audiences will hear in person from leading explorers, photographers, communicators and scientists. Before Christmas, we have adventurer Christopher Horsley, exploring some of the most active volcanoes in the world; geomorphologist Professor Colin Ballantyne, on a journey through time to explore the evolution of Scotland’s diverse mountain landscapes; runner Elise Downing, recounting her feat of running 5,000 miles around the coast of Britain; filmmaker Alex Bescoby, talking about his epic road trip from Singapore to London in a 1955 Land Rover; sea kayaker Will Copestake, sharing fabulous tales of adventure in the world’s wet, cold and wild temperate regions; TV presenter and author Cameron McNeish, reflecting on four decades of chronicling Scotland’s majestic landscapes and outdoor communities; climate and energy scientist Professor Stephen Peake, taking a once-in-a-lifetime tour of our Earth system and energy choices; photographer Colin Prior, on visiting the remote and magnificent Karakoram mountains, and on his sources of inspiration and influence in his work in over 50 countries; freelance journalist Rebecca Lowe, sharing the joys and challenges of her year-long 11,000km odyssey by bicycle across the Middle East; photographer Shabhaz Majeed, on a spectacular photography journey, showing Scotland from a

new perspective; and cyclist Lee Craigie, recreating the 1936 journey of 17-year-old Mary Harvie, who rode her bike 500 miles around the north-west coast of Scotland.

Admission to face-to-face talks is FREE for RSGS members, students and under-18s, and £10 for others. Tickets are available through rsgs.org/events or at the door. Pre-booking may be required for one or two venues; please see the printed programme (sent to all members) or our social media for details.

This year’s programme marks the first time that we are offering a monthly online talk, hosted through Zoom, on top of all the usual live talks at Local Groups, allowing the events to be especially accessible to everyone all over Scotland and beyond. We are delighted to bring you interviews with renowned explorers Robin Hanbury-Tenison, David Hempleman-Adams and John Blashford-Snell, endurance swimmer Lewis Pugh, skier and adventurer Myrtle Simpson, and ecocide campaigner Jojo Mehta Tickets for online talks are £2 for RSGS members, students and under-18s, and £6 for general admission. Book now at rsgs.org/events.

Inspiring

for 2022-23: face-to-face and online! come along to a talk!

In May, we were delighted to present RSGS Honorary Fellowship to author and conservationist Clifton Bain, for his crucial work towards the conservation of peatlands and promoting public awareness of their importance. Over the last ten years, Clifton has worked as Programme Advisor of the IUCN UK Peatland Programme on environmental policy and advocacy to promote the conservation of peatlands. He has also given public talks and written books about peatlands and other ecosystems, highlighting their value to people’s physical and mental health as well as to biodiversity and climate action.

With new content every week on our online blog (rsgs. org/blog) there’s always something of interest. Recent additions include:

• Circumnavigating the Globe, Part One – on 9th January 2022, Kirsty Fisher set sail from Antigua on board the 72ft sailing yacht Intrepid, bound for a circumnavigation of the world. Read her adventures in part one of her travel blog.

• Amundsen and Scott in the Great Tay Boat Race – artist Michael Durning was inspired to celebrate Scottish explorers, and at RSGS HQ he found that Amundsen’s race to the South Pole began in Perth!

• John Rae: gatecrashing the annual dinner of the Lochaber Agricultural Society – in 1856, a gentleman, apparently a tourist, arrived at the Society’s dinner just as the party were to sit down to dine. “My name is Rae,” he announced at the end of the evening, “and you may have heard it associated with the Franklin Expedition.”

In August, 82-year-old Nick Gardner from Gairloch completed the Munro-bagging challenge he had begun in July 2020, having never climbed a Munro before. He was joined by family and friends for the final climb, Cairn Gorm, and was met at the top by a guard of honour of supporters. “I’m on cloud nine, it’s absolutely surreal,” he said. “I was walking through the archway thinking, it’s all for me.”

Mr Gardner raised more than £60,000 for Alzheimer Scotland and the Royal Osteoporosis Society through the challenge. “I couldn’t look after my wife any more. She had to go into care and I had to get a project to refocus my life,” he said. “I am elated but I’ve not finished climbing. I have my eye on the Devon and Cornwall coastal path walk.”

The first articles for the revamped Scottish Geographical Journal have now been published online (www.tandfonline.com/ journals/rsgj20), with some available to read on open access, and all available free for RSGS members. The latest additions include:

• Periglacial landforms of Dartmoor: an automated mapping approach to characterizing cold climate geomorphology by Sadie Harriott and David J A Evans;

• Ukraine, Russian fascism and Houdini geography: a conversation with Vitali Vitaliev by Chris Philo and Vitali Vitaliev;

• The Anthropocene and the geography of everything: can we learn how to think and act well in the ‘age of humans’? by Noel Castree;

• The spatial variable: Professor Ron Johnston’s inaugural lecture (University of Sheffield, 1975) by Ron Johnston (with a foreword by Richard Harris).

The summer months have seen the continuation of much of our ongoing work. Katrina Strachan has done a fantastic job of pulling the 90 Inspiring People talks together and, because of the popularity of online talks, she has also organised a programme of six recorded interviews which we will schedule monthly throughout the talks season.

On the policy front, this is a busy period for government consultations around key geographical topics, from agriculture and circular economy to land reform, national parks and net zero. We will struggle to respond to all of these but, as ever, are keen to present the geographical perspective in these discussions wherever practical, and to provide input to discussions with partner organisations and representative bodies.

I continue to engage with the Cabinet Secretary’s advisory board on agriculture reform (ARIOB) which has just begun to revert to face-to-face meetings, and will determine the basis of future agricultural subsidies and priorities, particularly post-2024. I am also an ambassador for Glasgow’s National Park City campaign, which aims to use the familiar idea of a National Park to inspire a shared vision for Glasgow as a greener, healthier and wilder city for everyone, where people, places and nature are better connected.

External talks continue apace. In July, I was invited to present to the Scottish Science Advisory Committee of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, in Edinburgh, on RSGS’s exemplary approach to communicating science and sharing learning, particularly through the Climate Solutions course, and it is great to see this gaining traction in the wider world.

Martin Duddin was a proud Geordie who started his career in Scotland teaching Geography at Kirkcudbright Academy in 1974. He was appointed as Principal Teacher of Geography at Knox Academy in Haddington in the late 1970s, and was promoted as an Assistant/Depute Rector towards the end of the 1980s. An inspirational Geography teacher, Martin led a large number of foreign field trips, especially to the Alps, and established many links to other countries through the EU Comenius programme. During his time at Knox, he joined the committee of the Scottish Association of Geography Teachers, eventually serving as its Chair in the latter half of the 1980s.

Alongside his day-to-day Geography teaching, Martin worked for the Scottish Examination Board as a Marker and Examiner, progressing to become the Chief Examiner in Certificate of Sixth Year Studies Geography, the forerunner of Advanced Higher. A prolific author, he wrote and edited a series of school Geography textbooks. RSGS recognised his service to the teaching of Geography in Scotland by awarding him an Honorary Fellowship in 1995. In his retirement he enjoyed his membership of Rotary, and pursued his love of walking and of travel. He will be much missed for his wit, storytelling and love of people.

On 19th May 2022, Raleigh International closed. Formerly known as Operation Drake (1978–80) and Operation Raleigh (1984–88), Raleigh International was a youthdriven organisation supporting a global movement of young people to take action on the issues they care about. Raleigh worked globally to promote the role of young people in decision making and civil society, creating meaningful youth employment and enterprise, protecting vulnerable environments, and ensuring the right to safe water and sanitation.

Operation Drake was launched by HRH Prince Charles and RSGS Livingstone Medallist Colonel John Blashford-Snell, with scientific exploration and community service as its aims. It gave a generation of young people the inspiration to change the world; 55,000 volunteers from over 100 countries completed programmes with Raleigh. The decision to close was taken with deep sadness. Unfortunately, the effects of the pandemic resulted in delayed or cancelled programmes. Reductions in foreign aid and the cancellation of corporate partnerships were also directly impactful. In July, the travel company Impact Travel acquired the Raleigh International brand, which it plans to add to its portfolio. However, this would be a different entity to the registered charity Raleigh International.

The RSGS’s prestigious Medals and Awards allow us to recognise outstanding contributions to geographical exploration and learning.

• Scottish Geographical Medal, the highest accolade, for conspicuous merit and a performance of world-wide repute.

• Coppock Research Medal, the highest researchspecific award, for an outstanding contribution to geographical knowledge through research and publication.

• Livingstone Medal, for outstanding service of a humanitarian nature with a clear geographical dimension.

• Mungo Park Medal, for an outstanding contribution to geographical knowledge through exploration or adventure in potentially hazardous physical or social environments.

• Shackleton Medal, for leadership and citizenship in a geographical field.

• Geddes Environment Medal, for an outstanding contribution to conservation of the built or natural environment and the development of sustainability.

• Tivy Education Medal, for exemplary, outstanding and inspirational teaching, educational policy or work in formal and informal educational arenas.

• Bartholomew Globe, for excellence in the assembly, delivery or application of geographical information through cartography, GIS and related techniques.

• President’s Medal, to recognise achievement and celebrate the impact of geographers’ work on wider society.

• Newbigin Prize, for an outstanding contribution to the Society’s Journal or other publication.

• Honorary Fellowship, for services to the Society and to the wider discipline of geography.

We are inviting nominations for the RSGS Medals 2023. Visit www.rsgs.org/Pages/Category/medallists for more information and to access the nomination form.

In August, we were delighted to present RSGS Honorary Fellowship to Claire Mack, Chief Executive of Scottish Renewables, for overseeing significant growth in the renewable energy sector, and showcasing her dedication to implementing renewable energy across Scotland. By working closely with Scottish Government, leading NGOs and the public, Claire campaigned effectively for new developments, communicated the potential of renewables, and played an important role in strengthening Scotland’s position as a global leader in renewable energy.

A collection of lost essays by one of Scotland’s most remarkable women is being published in September by Edinburgh publisher Taproot Press (taprootpressuk.co.uk). Peak Beyond Peak: The Unpublished Scottish Journeys of Isobel Wylie Hutchison is compiled and transcribed by Hazel Buchan Cameron, who first discovered the essays in a box marked ‘Unpublished?’ while working as Writer-in-Residence for RSGS.

We are currently looking for volunteers for our 13 Local Groups (in Aberdeen, Ayr, Borders, Dumfries, Dundee, Dunfermline, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Helensburgh, Inverness, Kirkcaldy, Perth and Stirling) to help host our Inspiring People talks programme. We are also on the lookout for some more volunteers at our Fair Maid’s House Visitor Centre in Perth. To learn more about the local events in your area, or to volunteer with your Local Group, please contact us on enquiries@rsgs.org or 01738 455050.

In July, we were very pleased to present Professor Iain Black with RSGS Honorary Fellowship for his invaluable contribution towards the creation of the Climate Solutions course, which provides a simple and quick way to gain significant understanding of why and how to tackle one of the most important issues of our generation – climate change. Iain has worked closely with our Chief Executive to write and deliver the course, and its popularity is a testament to this effort, with an amazing 75,000 people now enrolled. Iain recently joined the University of Strathclyde Business School as Professor of Sustainable Consumption, to lead on the School’s sustainability strategy and develop the Climate Solutions programme.

In June, we were very pleased to present the Tivy Education Medal to a group of inspirational teachers and volunteers, for their collective work in creating free Geography lessons for Scottish secondary school students studying at home during Covid-19 lockdowns. There were limited learning resources for students, so RSGS coordinated a small group of teachers and filmmakers to try and help.

Alastair McConnell, Jennifer McLean, Gill Dean, Keith Turner, Alex Wylie, Carl Phillips, Jacqueline Smith and Shiv Das created 26 virtual Chalk Talks lessons covering the entire National 5 and Higher Geography curriculum, from glaciers to coasts, cities to deserts, and everything in between. Collectively, the lessons have had a fantastic response, accumulating over 35,000 views on RSGS YouTube. The team members were recognised for their exemplary and inspirational contribution to teaching, due to their incredible response during the Covid-19 pandemic, taking on extra work to deliver a public resource when so many were already struggling to adapt to the drastic and changing circumstances.

Based in Stirling, Bloody Scotland established itself as Scotland’s international crime writing festival in 2012. Over the years, it has brought hundreds of crime writers to the stage, for a programme of entertaining and informative events during a weekend in September, covering a range of criminal subjects such as fictional forensics, psychological thrillers, tartan noir and cosy crime. The special tenth anniversary festival takes place over 15th 18th September 2022, and includes several of the writers featured in this edition of The Geographer. See www.bloodyscotland.com/events for details.

Professor Roger Crofts FRSGS

Professor Roger Crofts FRSGS

At last, a comprehensive, up-to-date book on the geomorphology of Scotland. This scholarly treatment by 21 geomorphologists and geologists provides a review of the physical environment, detailed chapters on all parts of Scotland, and an overview of geoconservation. Two RSGS Fellows, Colin Ballantyne and John Gordon, have masterminded this magnificent tome which stands well in the World Geomorphological Series published in high-quality format by Springer. The text is accessible for the general reader and is aided by copious photographs giving examples of many places that are not well known.

In July, we were delighted to present RSGS Honorary Fellowship to Dr Nazzareno Diodato, founding Director and Research Fellow of the Met European Research Observatory, in recognition of his contribution to conservation and protection of the natural environment, and for his role in promoting climate research and environmental hydrology in water and soil conservation. Through his work, Nazzareno has helped to advance fundamental understandings in environmental hydrology, GIS science and nature conservation.

In late June, we launched a very special fundraising appeal to help us create a Future Generations Fund, an investment in activities to support and inspire our young people. We are thrilled that our members responded so warmly to this idea, and we have already received donations of over £10,000! This is a wonderful start to a five-year programme through which we aim to substantially increase our work with and for young people –promoting geography in schools, convening and mentoring young geographers, sharing skills and encouraging travel, providing public platforms, and much more. Thank you so much to those who have already donated. We are still welcoming donations: please visit www.rsgs.org/appeal/future for details.

In August, we were very pleased to present RSGS Honorary Fellowship to Professor Andrew Dugmore, for his invaluable contribution to world-leading environmental geography and humanenvironment interaction in Iceland and the North Atlantic. Andrew was a recipient of the RSGS President’s Medal in 2002, and since then he has continued to strengthen his reputation for his research and studies of long-term changes in environments, and the dynamics of complex socio-ecological systems.

Doors Open Day on Saturday 17th September will provide a great opportunity to visit our headquarters in the Fair Maid’s House in Perth. With a European Heritage Days theme of ‘sustainability’, and a VisitScotland theme of ‘Year of Stories’, the RSGS Collections Team has created a special display, Roots, Routes and RSGS, using our visitors book as the centrepiece from which rich stories flow. Everyone is welcome and entry is by donation.

11.30am - 4.30pm 17th September

We were delighted to welcome over 90 members of the extended Bartholomew family to our headquarters in Perth in July. The descendants of renowned Edinburgh cartographer and RSGS co-founder John George Bartholomew (1860-1920) and his wife Janet MacDonald had travelled across the world from the United States, New Zealand, Canada, Australia, Continental Europe, England and Scotland to celebrate their mutual relative. Coming from a celebrated line of map-makers himself, John George held the title of ‘Cartographer to the King’, and was the first to introduce the use of coloured contour layer maps.

RSGS Trustee Lorna Ogilvie warmly welcomed the family, before Chief Executive Mike Robinson addressed the visitors through video. The family members were shown around the Fair Maid’s House – home to the Society’s vast historical collections of maps, diaries, books, photos and artefacts, all gathered from scientific exploration over the past 150 years – by our experienced volunteers. Members of the RSGS Collections Team, headed by RSGS Trustee Margaret Wilkes, arranged a special display for the visitors; this included a small silver matchbox gifted to John George Bartholomew from co-founder Agnes Livingstone Bruce (daughter of the famous explorer and missionary David Livingstone) to mark his idea of founding the Society.

During their visit all members of the family were invited to sign a special map reproduced by artist Colin Woolf from The Times Survey Atlas of The World (1920) which was prepared at the Edinburgh Geographical Institute under the direction of John George Bartholomew, depicting world vegetation distribution and ocean currents. Four generations of Bartholomews signed the special map, including some of the youngest members!

“Glasgow is a magnificent city,” said McAlpin. “Why do we hardly ever notice that?”

“Because nobody imagines living here,” said Thaw. McAlpin lit a cigarette and said, “If you want to explain that, I’ll certainly listen.”

“Then think of Florence, Paris, London, New York. Nobody visiting them for the first time is a stranger, because he’s already visited them in paintings, novels, history books and films. But if a city hasn’t been used by an artist, not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively… Imaginatively, Glasgow exists as a music hall song and a few bad novels. That’s all we’ve given to the world outside. It’s all we’ve given to ourselves.”

Alasdair Gray (1981) Lanark

Landscapes of crime fiction may not immediately appear to be the most obvious topic for a special issue of The Geographer, but as the quote from Gray’s Lanark suggests, geographical imaginations are key to our sense of identity. How do ‘we’ imagine ourselves as a community? Much of this comes from popular culture and there are no literary (and TV) genres more popular than crime fiction. From serial killers and detectives to crime scene investigators, there is an almost insatiable desire for stories that illuminate the darkest edges of our worlds. This is evident in the increased number of book sales of crime fiction and the steady rise of events that bring together writers and readers on the genre from around the world including Bloody Scotland, Iceland Noir, Quasi de Polar and the Theakston’s Old Peculiar Crime Writers’ Festival to name but a few.

These representations of our landscapes are not just contained within pages of books or on our TV screens.

Recently, for instance, in association with the crime festival Bloody Scotland, Heritage Environment Scotland produced a volume of work that used their properties as a backdrop to various grisly acts of murder. From castle killings to walking mysteries this book utilises the public’s fascination with crime fiction to promote places. While the act of using violence to sell places appears counterintuitive the evidence reveals this most certainly to be the case. Recent television adaptations of Ann Cleeve’s crime novels, Shetland and Vera, have been held responsible for a spike in tourist numbers to the Shetland Islands and Northumbria with some individuals noting their desire to ‘follow in Vera’s footsteps’ and visit the fictional crime scenes that have taken place across the Northumbria countryside. There are Peter May-themed tours of Lewis.

Much of the so-called Golden Age of crime writing was dominated by English writers and is characterised by murder mysteries set in an interchangeable village landscape or country house; it doesn’t really matter where it takes place. More recently there have been a disproportionate number of northern-based authors who explore crimes that are organic to the landscapes within which they are set. The work of writers associated with Nordic Noir (such as Maj Sjöwall, Per Wahlöö, Henning Mankell, Steig Larsson, Arnaldur Indriðason and Yrsa Sigurðardóttir) and Tartan Noir (writers based in Scotland such as those included in this issue and others such as the ‘godfather of Tartan Noir’ William McIlvanney, Ian Rankin, Denise Mina, Peter May and Christopher Brookmyre) is set in dark and complex landscapes, haunted by past crimes and current injustice –so much so that the landscape itself almost becomes a protagonist in the stories.

The essays in this issue seek to address the question of why it is that the landscape is so important to crime writing, and especially to the Scottish tradition of Tartan Noir. First, Val explores the nature of Scotland’s relationship with crime writing, putting the blame for the lack of imagination in Alasdair Gray’s question that we started this piece with at the feet of Walter Scott. McDermid shows how her work, and that of other Scottish crime writers, emerged instead from the tradition of duality at the heart of Scottish culture and a concern with social justice. For her, the turning point was reading the work of William McIlvanney. McIlvanney had won the Whitbread novel prize in 1975 for Docherty, a moving portrait of a miner whose courage and determination were stretched to the limit during the Depression of the 1920s. He was a writer of great elegance and compassion who was never going to be constrained by other people’s expectations. He turned to crime with because he was passionate about writing

lives of working-class people and he saw the

the

Cheryl McGeachan, Jo Sharp, Val McDermid

“‘If a city hasn’t been used by an artist, not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively.’”

detective story as a milieu where he could effectively do that. Whatever he wrote was always going to be set in the Scotland he knew – a country of urban communities living cheek by jowl, a landscape of steel mills and coal mines and shipyards, a precarious world where poverty and unemployment were always lurking in the wings. These were stories that were animated by emotional, living landscapes: The derelict tenements were big darknesses housing old griefs, terrible angers. They were prisons for the past. They welcomed ghosts.

William McIlvanney (1977) Laidlaw

Of course, alongside the picturesque ‘Scott-land’ representations of our nation was another tradition, going back to traditional murder ballads (such as The Twa Corbies) and the dark dualities of Jekyll and Hyde. In a conversation with us, Louise Welsh explores some of the darker moments in this duality, and the ‘hauntings’ of older landscapes that would also characterise the work of many recent Scottish crime writers. The layering of old and new landscapes comes literally to embody social relations, crime emerging from the landscape itself. For instance, both Denise Mina and Liam McIlvanney write about the changes to the landscapes of postwar Glasgow in a way that captures the tensions and conflicts of the time. Liam McIlvanney highlights that the relocation of people from city centre tenements to the peripheral estates helped to generate extreme levels of interest and anxiety amongst the city’s population: when living in city centre tenements, people knew their neighbours – they shared outside toilets, back courts and washing lines. The new high-rise buildings broke up these horizontal bonds of communities, and the provision of such modern norms as private bathrooms and washing machines limited contact with neighbours. Any one of whom could be the Quaker or Bible John:

The screen showed more half-demolished buildings, disfigured streets. It looked like the footage from Europe after the war. Bombed cities. Smoking ruins. Sometimes it felt like they were fighting a war. The enemy was one man but he could have been anyone. He struck at various points in the city and left his dead for some civilian to discover. You responded by flooding a district with uniforms, knocking a thousand doors, but you never got close.

Liam McIlvanney (2018) The Quaker [emphasis added]

Although he has lived in the city for much of his life, it took Doug Johnstone until his 11th novel to look directly at Edinburgh. In part he struggled with the weight of literary representations of his new home, but the juxtaposition of different urban areas, and the sense of the palimpsest of historical landscapes revealed through the experiences of his three generations of funeral director-detectives opened up new possibilities for him.

In her conversation, Welsh points to the persistent fascination with the Scottish countryside in crime writing. Contributions from Ann Cleeves, Lilja Sigurðardóttir and Lin Anderson reveal the complexities of these landscapes that move us on from

the idyll of Scott-land. For Ann Cleeves, it is the combination of the rapid social change and dislocation caused by the influx of oil money (and outsiders) with the extremes of the northern landscape that makes the Shetland Islands such a fertile location for her writing. Similarly, Lilja Sigurðardóttir notes the similarities between the northern attitudes of her place of birth, Iceland, and her new home, Scotland, exploring the ways her own writing has opened up now that she has wider vistas than her claustrophobic homeland. Lin Anderson celebrates the way that the diverse landscapes of Scotland provoke different narrative possibilities for her work, whether through the rapid turn of the weather or the dramatic possibilities of communication black spots. Our final contribution is from a soil scientist, rather than a crime writer. While most forensic scientists chafe at the misrepresentation of their work in many popular TV shows, there is considerable collaboration between forensic scientists and crime writers in Scotland, which has led to joint events and publications, and even the ‘Val McDermid Mortuary’ at the University of Dundee! Professor Lorna Dawson writes about the benefits of working with crime writers and demonstrates the intricate relations between fact and fiction in the creation of crime novels.

In putting together this collection, we are drawing inspiration from the collaborations between crime writers and forensic scientists in Scotland to make the case for opening discussion between crime writing and geography. Exploring the ways in which the effects of crime ripple through our landscapes as much as individual lives or societies points us to new exciting considerations of place, community and the darkest edges of our geographical imaginations.

“The new highrise buildings broke up these horizontal bonds of communities.”Image by Vishnu Prasad from Unsplash.

I chose this quote from the Scottish band Deacon Blue as the epigraph for a novel called The Distant Echo, which was published in 2003. Although Scottish crime fiction had started to make an impact far beyond our borders, it still seemed to me that when people thought about Scotland, what they conjured up for themselves was not a real place. Why did it take us so long to embrace a genre that appears to have been designed specifically for our dark winter skies and the dour Presbyterian side of our national character? I believe the answer can be laid at the door of one man. When visitors get off the train in Edinburgh, they alight at the only railway station in the world named after a novel: Edinburgh Waverley. When they emerge from the station, they’re confronted with an ornate Gothic spire stained black by years of pollution. It’s the biggest monument to a writer anywhere in the world. It was built by public subscription –though the city council did struggle towards the end, literally sending people from door to door with a begging bowl – and it honours the memory of Sir Walter Scott. In his obituary, the Edinburgh Evening Courant wrote that “Cervantes has done much for Spain and Shakespeare for England but not a tithe of what Sir Walter Scott has accomplished for us.” He published 21 novels between 1814 and 1832, and those novels, coupled with the myth he constructed around himself, were responsible for the confection of Scottishness that has proved remarkably persistent in spite of its lack of grounding in any recognisable historic reality. Tartan and shortbread; the romantic image of the Highlands and their noble way of life; the shocking transformation of our history into sentimentality. All of this can be laid at the door of Scott. For many years after his death, Thomas Cook was running Tartan Tours. Cook said, “Sir Walter Scott gave a sentiment to Scotland as a tourist country.”

And the historian Lord Macaulay wrote, “Soon the vulgar imagination was so completely occupied by plaids, targes and claymores that, by most Englishmen, Scotchmen and Highlander were regarded as synonymous words. Few people seemed to be aware that a Macdonald or a Macgregor in his tartan was to a citizen of Edinburgh or Glasgow what an Indian hunter in his war paint is to an inhabitant of Philadelphia or Boston. At length this fashion reached a point beyond which it was not easy to proceed.”

We accepted the bogus tartan caricature. It lingers still in dozens of city centre outlets whose only ingenuity is revealed in the number of things to which tartan or Harris tweed can be attached. And for a long time, it hogtied us.

As the novelist and historian J M Reid wrote in the 1920s, “Nineteenth century Scotland was one of the chief centres of the industrial world. Its society was complex and curious enough to feed and excite any keen observer of human nature. Yet there is no Scottish Balzac or Dickens, not even any Thackeray or Trollope. Scottish writers and their readers both inside the country and elsewhere preferred Scott-land to Scotland.”

It was quite a straitjacket to burst out of. There was however one kind of fiction that it did lend itself to, and that was the

adventure novel, because the scope of the adventure novel could be played out against a rural backdrop rather than an urban or industrial one. In Kidnapped and later Catriona, Robert Louis Stevenson used Scott-land to great effect. But because he was unquestionably a better writer than Walter Scott, he wrote about the landscape more evocatively and more effectively. His descriptions of the Highlands and Islands add another dimension to the fiction, creating a vivid

“We accepted the bogus tartan caricature.”The Scott Monument. Image by Ric Brannan from Pixabay.

backdrop for the action to play out against. Some years later, John Buchan did much the same thing in The Thirty-Nine Steps with Richard Hannay’s flight across the Scottish borders. But in spite of the landscape’s service to the narrative, Scott-land was still in the ascendant. Because the engagement with that landscape was these books’ only engagement with the country, they reinforced the prevailing image rather than exploring what lay beneath.

It’s true that Tartan Noir has some significant forebears. James Hogg is usually identified as the first of these, with The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner. Published in 1824, it’s often cited as an early example of modern crime fiction. And if, as I do, you consider Graeme Macrae Burnet’s Booker Prize shortlisted novel, His Bloody Project, as a crime novel, then clearly Hogg fits the category. It contains murder; it’s largely narrated by its criminal anti-hero; and the action takes place in a historically and geographically defined Scotland. However, it also features angels, devils and demonic possession and it has elements of metafiction, satire and the gothic. Many attempts have been made to translate its complexities to the screen and all have failed. To be honest, it’s a tough and complicated read. It’s not the sort of book to kickstart a genre.

The next in line is Robert Louis Stevenson. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, published in 1886, is generally viewed now as an early example of the psychological thriller. At its heart is the idea that repressing our dark side is bound to have terrible consequences. But the threat of violence and murder runs through its pages like a sinister black thread. There’s no doubt it deserves its place in the pantheon of the genre. But again, like The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, it’s too far from the mainstream to be the kind of pioneering work others can readily follow. Strange chemical potions and radical personality shifts work brilliantly here, but it’s not a template that’s easily adapted.

It also reminds us that it’s virtually impossible to write about a Scotland that isn’t Scott-land. For Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’s adventures are not set in Stevenson’s native country. It’s not Edinburgh’s smoke-darkened streets and straitjacketed society that feature in its pages. Even though reading it always conjures up for me the close-packed warren of the city’s Old Town, that’s not where Stevenson tells us his story is taking place. Jekyll and Hyde’s city is London. London had a fictional, imagined identity already. There was nothing

ground-breaking in setting a novel of sensation where so many had previously taken place. But that safety net probably allowed Stevenson to unleash his imagination in different directions.

The next Scot to make a mark on the landscape of crime fiction was, metaphorically, even more of a monument in the literary landscape than Walter Scott. And he too chose London as the setting for his detective, even though that detective’s roots were very firmly in his home city of Edinburgh. The story behind the creation of Sherlock Holmes is well known, but I’ll recap briefly.

When Arthur Conan Doyle was a young medical student at the University of Edinburgh, one of his teachers was one Dr Joseph Bell. Bell was renowned among his students for his diagnostic skills. Not only could he adduce what ailed the patients who presented themselves at his door, but he could also draw inferences about their lives and their occupations from details of their clothing and aspects of their appearance. Conan Doyle, like many of his fellow students, was entranced by this and when he was embarking on his career as a writer, he remembered his former mentor and decided to enhance Joseph Bell’s skills and give them to the great consulting detective. But although his family’s often straitened circumstances meant that Conan Doyle knew the underbelly of his native city as well as the polite drawing rooms of lawyers and professors, still he turned his back on it and used the teeming metropolis of London instead. It’s hard not to see that as the result of the familiarity of writers and readers with London. At the very least, Edinburgh must have felt like something of a risk. It’s always easier to take the more well-trodden path, especially if the stories you are writing are breaking new ground, as the Sherlock Holmes stories were.

By choosing London for their great popular success, it seems to me that the Scottishness of Stevenson and Conan Doyle was somehow buried. Their work contains the elements of what we have come to know as Tartan Noir – the fascination with what lies beneath, the psychology of crime, the idea of duality and the doppelganger, and those occasional shafts of black humour – but London disguises that distinctiveness. The so-called Golden Age of crime fiction – that period between the two world wars – was almost exclusively an English phenomenon. Scots novelists were being published –the likes of Jessie Kesson, Lewis Grassic Gibbon and Neil Gunn – but they weren’t killing people for fun.

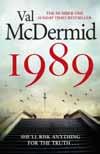

Val McDermid is a writer and broadcaster. Her most recent novel is 1989.

This article is an excerpt from her longer essay, I Now Describe My Country As If To Strangers, published in New Zealand (Dunedin: Dalriada Press, 2022)

“The scope of the adventure novel could be played out against a rural backdrop.”

Louise Welsh is an author and Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Glasgow. We sat down with Louise to chat about the role of the Scottish tradition in crime fiction, the importance of landscape in her writing, and the hauntings of the past in our contemporary worlds.

Jo: What are the key Scottish influences on your work and how important do you think the Scottish tradition is to your crime writing?

It’s funny isn’t it, because I guess, here I am a Scottish writer. You know, you don’t think about it in that way. You don’t go to your desk and think, here I am, a queer Scottish writer writing at the beginning of the second decade of the 21st century. You don’t. You’re not conscious of that as you’re writing, but of course, your place, your politics, your own personal history. All of that impacts on your work.

Also, that connection between politics and social realism, that’s still important within my work, and I think that’s something that you get in the Scottish tradition. I read James Hogg’s Confessions of a Justified Sinner probably every couple of years as a text that I go back to and a text that I didn’t discover until I was a young adult. But it’s a text that means a lot to me and I think that part of what that has is this element of social realism but also this element of absurdity, which I think is quite important to crime fiction, because in a way it’s an absurd genre. But we’re asking the reader to really invest. And then there’s moments where you can have this release.

I guess the other thing about Scottish crime fiction is it’s an international fiction, so we are influenced by Scottish texts, but we’re possibly equally influenced by European texts or texts from America. I’m increasingly interested in Chester Himes, who I think has this element of real hard social realism. The grit. And then this strand of absurdity. Himes says that the life of a black person in America is absurd and so I wrote an absurd fiction because the degree of prejudice that he faced was, it’s like Kafka.

Cheryl: As geographers we are really interested with this issue of landscape and how you use and think about landscape in your work. Do you think landscape is particularly important in crime fiction?

Yeah, I think it’s massively important and I think it’s also one of the pleasures of writing. When I’m editing I have to pull back on the landscape because I could just, it’s the bit where I get carried away and when you come back there’s often a lot of that that I have to take out. But I guess my books tend to be quests. You know, just that straightforward ancient form. And within that the person is always moving through some kind of landscape and often, for me, it’ll be a cityscape. So, what does it do? I guess we’re always looking at how the person responds to their environment. It has to be what they see. So, in this book [The Second Cut], Rilke is not me. We had breakfast outside in the central garden this morning. So, I go out and I think I’ll look at that lovely clematis. Isn’t that gorgeous? And these daisies are coming up and Rilke doesn’t think that, he doesn’t notice the flowers. He notices something else; you know?

And then there’s also the way in which the urban landscape again reflects politics. I went out to the local pub and sat in the window and looked out. And there was a moment when I was like, look at this place because the road is a mess. The actual road itself is a total mess. There’s graffiti everywhere. The building opposite you can see that there’s bits crumbling at the top. There is just the remnants of a street light which is no longer a street light. It’s just a great big bit of rusted pole at the edge of the ground. There is so much decay in this little square. This view from this window, is so reflective of this built environment, this urban landscape that I’m looking at, is reflective of so much. The people that are going across it. So many people with compromised health. Just within half an hour of sitting looking out the window, you could see a lot about the world, and that finds its way into your book because the book is political, even though it’s a story it has political underpinnings. And I see myself very much as a storyteller, and a story is like music as well, isn’t it? You have this sort of build-up and release like you do in music. And I think you have that in the novel as well. And the other thing that you have, of course, are repeating moments that you don’t really want people to notice or repeat in moments, but they’re also part of the build-up too. And a lot of that’s just done unconsciously because I think you know how to tell a story. I think it’s build up, release, build up, release, and landscape plays its role in that and sometimes it’s a quieter moment. But it is not just a quiet moment, it must be stuff where you’re still entertaining. You’re still somehow transferring some ideas that you might be building in there. You might be burying. You know, this is gonna come up again later. And I want you to remember it, but I don’t want you to notice it.

Jo: In your work, landscape is never simply a kind of superficial thing.

Cheryl: There is a real sense in which the past continually reemerges through your writing.

I think I understand the world historically. Maybe this is part of the reason that the crime form appeals to me because often it is asking how did this happen and how did we get to this point? And I think within politics or any sort of issue, how did we get to this point, how did we get here is important, and that’s part of what history tells us. Also, if you occupy a city for a long time or a country for a long time you begin to become familiar with the history. You also have your personal histories. As you walk along the road you think, oh yeah that pub used to be called this… you can see what used to be there as well as what is there.

And this is a fundamental form, and in my opinion, crime writing is a fundamental form. Ghost writing, romance, etc, they’re all things that connect to the stomach and the heart. You know, the gut. And what you can see in these are people’s politics and what people are scared of. There are points where they’re really scared of women’s liberation. And there’s also a kind of colonial ghost stories where you think people are aware that something has been done that’s wrong, and that these people who they’ve wronged may come back and get

, School of Geography& Sustainable Development, University of St Andrews, Geographer Royal for Scotland, and RSGS

“The person is always moving through some kind of landscape and often, for me, it’ll be a cityscape.”

them. And that’s expressed in some of these ghost stories. Jo: I remember being struck by listening to Sarah Paretsky who was talking about, how do you write about crime when your entire country is a crime scene? And that was when Trump had just been elected. And it does seem that so much Scottish crime writing is not just about the individual crime at the heart of the story, but there is that sense of wider injustices, that using Cheryl’s language, kind of haunt the landscape that the protagonist is moving through?

Definitely. And I think this is part of the international nature of the genre as you mentioned Sarah Paretsky there. She’s so right, isn’t she? And this is, I think the same for a lot of us. We might be politically engaged in whatever way that we are, we might make personal choices too. But I think a lot of us feel quite overwhelmed at the moment. You can feel that our country is changing in a way that’s massively distressing and we don’t know if we can get it back. Will we be able to regain

the National Health Service after this decade of austerity?

One of the things that we can do is write. And so, I think it’ll be really interesting to see how the genre develops because there’s so much happening and it’s all happening so quickly. How do we express this and how do we embed our politics? And I wonder, will there be a rise in historical fiction that somehow embeds some of this in it? Because to write in the contemporary world is difficult.

“Just within half an hour of sitting looking out the window, you could see a lot about the world.”Image by Fer Gregory from iStock.

Doug Johnstone

Doug Johnstone

On one level, my last four novels have been love letters to my beautiful and idiosyncratic home city of Edinburgh. This was deliberate; they’re a series of books about the Skelfs – three generations of women who have to take over the running of a funeral directors and a private investigators when the patriarch of the family dies.

Those businesses are based in a large Victorian pile on Greenhill Gardens overlooking Bruntsfield Links, with a view of Edinburgh Castle in one direction and Arthur’s Seat in the other. While that location was deliberate, so was the idea that the women would be running two concurrent businesses spread across the whole city. In the operations room of the house (which is really just their kitchen), the Skelfs have a huge map of the city, covered in pins for all the locations they regularly use in the funeral game. A spider’s web of cemeteries, graveyards, crematoriums, care homes, hospices, hospitals and the city mortuary, a city of death that lies beneath our everyday experience, was an idea that appealed to me greatly.

So the women venture to all corners of Edinburgh dealing with the dead and helping the living at the same time. From Leith to Corstorphine, Silverknowes to Blackford Hill, the books take readers to the parts of the city that tourists rarely see.

But it took me a long time to reach this point. The Skelfs series started with my 11th novel, but my first few books barely featured Edinburgh at all. My debut novel, Tombstoning, was set mostly in the seaside town of Arbroath where I grew up. When it was published in 2006, I had lived as long in Edinburgh as I had in Arbroath, having moved to the city to study in 1988.

But, looking back, I was subconsciously scared to write about Edinburgh. My next two books avoided the city in similar fashion: The Ossians was a road trip around the Scottish Highlands, while Smokeheads was about a disastrous whisky-tasting trip to Islay. All three of these books featured characters from Edinburgh travelling elsewhere. It’s almost as if I couldn’t bring myself to look directly at the place.

No doubt this was because Edinburgh feels like a very wellmapped literary city, from Sir Walter Scott through Muriel Spark, Ian Rankin, Kate Atkinson, Irvine Welsh, Alexander McCall Smith and beyond. As a novelist just starting out, who was I to tackle this wonderful place? But eventually I began to realise that I had all this wealth of experience living in Edinburgh that I wasn’t tapping into. And, after all, everyone’s version of a place is completely different; why not try to depict mine?

So I did. Initially, this was in geographically contained small doses. Over a number of standalone thrillers, I set the action in compact and distinct areas of the city – again, the lesser-travelled parts. Gone Again was set almost entirely by the beach in Portobello, The Dead Beat in the student-friendly Southside, Breakers in the schemes of Craigmillar and Niddrie. I even wrote one novel, Faultlines, in an alternative version of the city plagued by earthquakes, and with a newly created volcanic island in the Firth of Forth.

But all that time, I longed to write about the city as a whole. Swimming in Wardie Bay, scattering ashes at the top of Crow Hill next to Arthur’s Seat, visiting a widow in Craigentinny, investigating an escaped black panther in the back gardens of The Grange, I wanted to do it all.

I don’t know if Edinburgh is unique amongst small cities, but both the layering of history and the present, and the jostling of rich and poor neighbourhoods next to each other, are endlessly fascinating. It’s a ten-minute drive from the most deprived parts of town to the most affluent, and that creates a visceral sense of tension and friction on the street.

Like police officers or journalists, funeral directors are one of the very few professions that go across these barriers and reach all parts of a city. Everyone dies, after all. It’s that ability of the Skelfs to delve deeply into the psychogeography of Edinburgh that keeps me writing about them, and I don’t see that stopping any time soon.

“It’s a ten-minute drive from the most deprived parts of town to the most affluent, and that creates a visceral sense of tension and friction on the street.”Image by Jim Divine from Unsplash.

I first went to Shetland in the 1970s and then it was a place of contrasts. Oil had just arrived into the islands and Lerwick, the main town, had a gold rush feel. Men (and it always was men) spilled out of the bars by the harbour, and islanders with a truck or building skills, or the initiative to set up a cleaning company to service the accommodation block at Sullom Voe, could make more money in a few months than their parents had after years of crofting.

Shetland Islands Council had the sense to allow the oil to come ashore on their beautiful islands only if a percentage of every barrel was paid to the community. Suddenly, there were swimming pools and leisure centres, new schools, new care homes, subsidised theatre and music. All this for a population of a little over twenty thousand. There were new people too. Some made no effort to integrate and some tried too hard, using dialect words with abandon, or learning to spin. It seemed to me that islanders usually accepted the strangers. Shetland is used to incomers – or ‘soothmoothers’ as they are known – from Vikings to whalers to Eastern European workers in the fish processing plant. Crime fiction is often populated by outsiders.

I was working in Fair Isle, the UK’s most remote inhabited island, where little had changed in generations, and the oil had no impact. Edie still milked the Midway cow by hand, hay was formed into stooks to dry, and we all turned out to round up the hill sheep for clipping. Women knitted the old patterns, or invented new ones, and no celebration was complete without traditional music and dancing. I fell in love with the place, its people and its stories, and though of course the isle has changed, I love to go back. It still feels like my place of sanctuary. Shetland’s contrasts make it a perfect setting for the crime novel. There are few trees in the islands. There are too many sheep and the winds are too strong to allow any natural vegetation to take hold. Mainland is long and thin with inlets called voes cutting into the coast. The sea is everywhere, there are no tall buildings to break the horizon. The sky is enormous. It would seem in this bleak and open landscape that nothing could be hidden. And yet, in small communities everywhere, there are secrets. Some are known, but never

spoken of, because without a degree of privacy we would all become slightly crazy. Some are unknown, but held, brooded over, almost cherished. It’s in these secrets that most of my stories begin.

Shetland lies so far north – on the same line of latitude as parts of Alaska and Greenland – that each season is very different from the others. In midwinter it doesn’t get light until ten and dusk comes again in the middle of the afternoon. This is a place where weather matters. There are winds strong enough to rip an opened door from a car, to stop the daily ferry to Aberdeen, to ground planes. Of course, the background howling of the storm, the dark days, the contrasting warmth of peat fires in croft kitchens, provides atmosphere. Readers who enjoyed the darkness, literally and figuratively, of Nordic Noir found something similar in Raven Black, the first of my Shetland novels.

Midsummer is altogether different. Then it’s light nearly all night. Islanders call this the simmer dim, or summer dusk. It’s possible to read a newspaper outside at midnight, and the birds are still singing. I asked a crofter once what happened at midsummer. “We single neeps and clip sheep.” He paused and grinned. “And we party!”

The oil and the gas no longer provide the income they once did, but still the islands thrive. Fishing has always been more important to the economy. Soon they’ll be exporting wind-driven power, though without, it seems, the same splendid deal as the oil. I sense some resentment as the giant turbines appear on the bare ridge in North Mainland. Tourism, especially cultural tourism, has grown by nearly 50% in the last 20 years. There are folk festivals, jazz festivals, a film festival curated by Mark Kermode, and Wool Week when people from all over the world come to learn about the famous textiles. I’ve stopped writing novels about Shetland, but I’m still fascinated by the place; there are still stories to be told.

“I fell in love with the place, its people and its stories.”Ann Cleeves is the creator of the Vera, Shetland and Matthew Venn series. The new Vera novel is The Rising Tide Image by Robert Witanski from Unsplash.

When you look at the top of a globe you can see that the Norwegian Sea is enclosed by countries that make almost a perfect circle around it: Greenland, Iceland, Norway and Scotland. This vast sea was but a pond to the seafaring Vikings who travelled it constantly, exchanging goods and services, robbing, killing and taking slaves. They understood the world as a circle of countries inhabited by different peoples who all spoke or could at least understand Old Norse, or Icelandic as we call it today. Our sagas rhyme with Scottish tales of great clans and their disputes, we also have selkies, the Shetland trows have the same characteristics as our ‘hidden people’, except trows are small and live in the ground but hidden people are human-size and live in rocks.

Some of my favourite crime authors are Scottish and I have been influenced by them in many ways. Now that I have a second home in Glasgow, and am getting to know the city quite well, my writing world has expanded and my stories are reaching out towards Scotland for material. It gives me freedom to not be bound to an Arctic island with almost no murders. The protagonist of my new series, Áróra, is half Icelandic, half English, and living in Edinburgh. And although the story starts with her leaving Scotland for Iceland to look for her missing sister, she as a character has possibilities an Icelandic character doesn’t have. One of these possibilities is looking at Iceland as an outsider looking in, a reflection important to me as I have spent so much of my life abroad. The similarities between Iceland and Scotland are reassuring to me because the Scottish environment is not something I struggle to make sense of, and neither are its people or their culture. I feel at home in Scotland.

It has the same stark difference between the long days of summer and the dark melancholy winters, but there is at least some daylight in winters and some darkness in summer so you can sleep. And Scotland has lots and lots of trees. Iceland mostly has moss and shrubs. With roughly eight degrees of latitude between Reykjavík and Glasgow, making it an exactly two hours flight, the weather in Glasgow is so much better than in Iceland. I am told I might be the only person who comes to Glasgow for the weather, but these two hours on an airplane take me from knee-high snow in late March to sitting in the sun on the green grass of the Glasgow Botanic Gardens.

The food in Scotland is also a little bit better than in Iceland. I am not talking about the price here (as then I would say much better!), but it is fresher, because Scots both grow more produce and are closer to the European food markets so vegetables and fruits still have flavour when they arrive in Scotland, but have lost it as the gas-filled shipping containers finally reach Iceland. The same goes for culinary delights: it is undeniable that haggis is better than our slátur, the scones are better than our skonsur and whisky is better than brennivín. Icelandic crime fiction is shaped by the Nordic social structure and sense of justice. We have a very mild view on crime and

punishment. The maximum prison sentence is 20 years but everyone gets parole after twothirds of it is served. The Nordic attitude toward crime – that the reasons behind crime are mostly of a social root and therefore everyone deserves a second chance – is reflected in the crime fiction. I always feel Scottish crime fiction also has this sense of ‘sympathy for the devil’ as well, and have always found it to be much closer to Nordic Noir than for example the English crime fiction.

Like everything else, Scottish crime fiction is slightly better than the Icelandic. By better I probably mean more developed as a genre. When we compare the debut dates of William McIlvanney, the godfather of modern Scottish crime fiction, who wrote Laidlaw in 1977, and his colleague Arnaldur Indriðason, the godfather of Icelandic modern crime fiction, who wrote Sons of Earth in 1997, we see that the Scottish crime fiction has exactly 20 years on us.

In literature a lot happens in 20 years. I can only hope that in two decades Icelanders will have more authors and that we will have developed a more defined sense of Icelandic-ness, just like Scottish crime novels always give you a strong sense of place but also a strong sense of the national identity of the people.

Lilja Sigurðardóttir is an award-winning Icelandic writer for page, stage and screen. She lives in Reykjavík with her partner but spends a lot of time in Glasgow where she has a second home. Her latest book out in English is Cold as Hell, a missing persons mystery and the first in an exciting new series.

“I might be the only person who comes to Glasgow for the weather.”

Prior to becoming a crime writer, I’ve been lucky enough to live and work all over Scotland. From Glasgow to Orkney, from the Highlands to Edinburgh and parts in between.

The inspiration for my protagonist Dr Rhona MacLeod came from one of my former Maths students at Grantown Grammar School, Emma Hart, who studied forensic science at Strathclyde University.

Throughout the series of currently 16 novels, Rhona has attended crime scenes in all of the places I have either lived in, or spent time in. In fact, all the stories have been inspired by such places.

The opening scene of each of my books has always come to me as a visual image. The location may be rural or urban, but the place itself immediately becomes a character in the story, essentially providing the question that drives the tale. What if you were stranded on top of Cairngorm at Hogmanay in a snowstorm? (Follow the Dead). What if a storm drove an abandoned cargo ship against the cliffs at Yesnaby on the Orkney mainland? (The Killing Tide).

Once I’ve decided the location, everything arises from it. In Follow the Dead, four young climbers take refuge from a blizzard at the Shelter Stone near Loch A’an on Cairngorm, after which three of them are found dead. Speaking to Willie Anderson, team leader of Cairngorm Mountain Rescue, I learned that in such circumstances his team would essentially be the first forensics on the job. Protecting the locus, taking photographs and bringing in Rhona by helicopter to study the crime scene in detail. In our discussions I also learned that light aircraft frequently come down on Cairngorm, especially

in poor weather, many from Norway. He showed me a photograph of one such icicle-clad aircraft, which sent me to Stavanger in Norway to interview the police there, which both inspired the character, Police Inspector Alvis Olsen of the Norwegian National Bureau of Investigation, and informed the story.

The latest book in the series, The Killing Tide, was inspired by my reading about a ghost ship which came aground south of Cork. I immediately wondered where such a ship might meet land in Scotland, and, having lived on Orkney, knew the perfect place would be on the cliffs at Yesnaby. When the ship is boarded by the coastguard, three bodies are found in what appears to be a gladiatorial fight to the death. The difficult location of the ship, the possibility of it becoming an environmental disaster, the international nature of the incident, all played into how Rhona might examine the crime scene, and who would take charge of the investigation, Police Scotland or the Metropolitan Police. Rhona’s base is at Glasgow University (my Alma Mater), where I have placed her lab with a view to die for over Kelvingrove Park, which in reality, I am well informed, is where the Principal’s office is. The geography of her workplace, the park, her flat in Park Circus, all play a role in the books, and are a great contrast with the loci outwith the city.

The characters that surround her, and those she meets during her work across Scotland, are also informed by the locations they inhabit, as are their reactions to the crime.

I had a lot of fun with this in None but the Dead. Set on the Orkney island of Sanday, which does not have a police station, and where the ferry from Kirkwall takes an hour and a half to reach this northern isle, presents a difficulty for DS McNab. A townie, he finds himself as though in a foreign land, where there is no signal for his mobile phone, little internet access, no local police, and where he is totally reliant on locals to supply him with information. As for Rhona, she is comfortable wherever she goes. For her, the geography of the locus is as important as what she finds there, because it forensically informs what has happened to the victim, which is her overriding concern.

“Once I’ve decided the location, everything arises from it.”Lin Anderson is a writer and screenwriter, best known for her series of forensic thrillers starring Dr Rhona MacLeod. Her most recent novel is The Party House Lin Anderson Glasgow University. Image by Charlie Irvine from Pixabay.

I am a forensic soil scientist (and before that a biogeographer) contributing to the criminal justice system on the question of from where something has likely originated. This can be in the forensic examination of a questioned sample from an object such as a vehicle, tool or footwear/clothing to ascertain from where it likely had originated. From this examination, areas can be identified where a sample could not have come from (ie, is totally different/exclude) to assist and guide the police to search within a limited area of where it could have come from (ie, it cannot be differentiated from/include). I am invited by police forces from the UK and across the world to make such assessments in relation to objects and soils from crime scenes (ie, the site where a body or objects were recovered from).

Working mainly within a nation that works under an adversarial system of law, involving juries as the triers of fact, I believe it is important that forensic scientists endeavour to make their science easy to understand by the layperson and the findings clear to evaluate. For that reason, I am delighted to work with crime writers as they explain the use of my science (forensic soil and ecological sciences) in their novels, in describing locations (places) and crimes in ways that are easily understood.

I have had the pleasure in working with many UK crime writers over the last 20 years. One of these is the well-known Scottish crime writer Alex Gray, who has utilised my expertise in forensic soil science/ecology several times in her novels. She writes:

“Facts within fiction matter. Take, for example, the search for a missing person, especially in cases when it appears that the likelihood is of finding a dead body. Now, Lorna has a superb track record when it comes to tracing samples of soil to their original geographical location, and so having her work alongside William Lorimer, my fictional detective, was a real coup. The story of The Stalker, when Lorimer’s teacher-turned-children’sauthor wife, Maggie, is off on a book tour, follows several locations around Scotland, mainly destinations I have visited during my own book tours. What the reader discovers, however, is that Maggie’s stalker who follows her around the country has in fact killed women before, burying one of his victims in a remote Ayrshire wood.

“Enter Professor Dawson, having been given the missing woman’s wellington boots, and lo and behold, the very deposition site is discovered!”

Therefore, demonstrating the many ways in which fact and fiction collide in crime fiction.

Lin Anderson is another leading Scottish crime writer who has used soil geography in her novels to great effect, describing place in an eloquent manner. In Sins of the Dead (2019), she used soil forensics as an integral part of the plot, illustrating that soil can be useful in an urban environment as well as in a rural setting. In her novel None but the Dead (2016), Rhona, her forensic scientist, used the spatial distribution of soil on the map of Sanday to help the reader work out where someone had driven or stood.

Another great crime writer, sadly no longer

with us, is beloved Alanna Knight, who embraced the sense of place within her novels. For example, in The Darkness Within (2017), Alanna revisited her beloved Orkney:

“The sea road was rough and dangerously narrow, running in many places close to the cliff edge and requiring care and skilful attention from the driver. It was not for a nervous passenger. Faro was glad that he had no fear of heights, watching the translucent, wild-green Atlantic rollers crash on to the long stretches of pale gold sand.”

(The Darkness Within, 2017)

Not only did Alanna “walk the paths and touch the stones” as she used to say, but she captured place as seen through the eyes of real historical figures: “Wild and desolate. As the road twisted its way out of Ballater into the mountainous countryside, the late Queen’s words in her journal described the scene most aptly. She had loved to draw it, as I did now, as we progressed west along the road with far below us tantalising glimpses of a gleaming river.”

(The Balmoral Incident, 2014)

Alanna Knight was also a fine artist; her many watercolours of landscapes in Scotland are prized by those friends who gratefully received them over the years.

In a lovely twist of fate, soon after meeting Alanna I discovered that her husband, Dr Alastair Knight, was a colleague at the same laboratory where I started my career as a soil scientist. I would often chat to him in the canteen of the then Macaulay Institute, now the James Hutton Institute, about his recent inventions, and so admired his skills in analytical chemistry. I imagine Alanna had used gems of his knowledge in her wonderful historic crime novels.

This article is dedicated to the shining light of crime fiction, Alanna Knight MBE (1923–2020), born Gladys Allan Cleet, a British writer who was based in Edinburgh.

Soils on the island of Sanday, Orkney.

“I am delighted to work with crime writers as they explain the use of my science in their novels.”

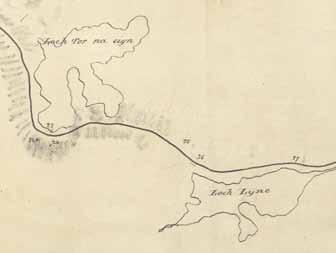

This hand-drawn sketch map by the Sutherland estate and county map-maker, Gregory Burnett, shows the location and details connected to a brutal robbery and murder that took place in Assynt. In the early morning of 20 April 1830, a man’s body was found floating in Loch Tòrr na h-Eigin (marked as 22 on the map), about a mile south of Drumbeg. The body was subsequently identified as Murdoch Grant, an itinerant peddler from Lochbroom, who had mysteriously disappeared a month earlier whilst passing through Assynt. Locals initially wanted Grant to be buried as a suicide, but it was observed that the peddler’s pockets had been turned inside out, and his death had been caused by wounds to the head inflicted with a blunt-edged iron instrument. Grant had also been known to be carrying a large sum of money from recently selling his wares.

For several months the crime was unsolved, but suspicion eventually fell on Hugh MacLeod, a young schoolmaster from Loinn Mheadhonach (26 on the map), an isolated settlement less than half a mile south of Loch Tòrr na h-Eigin. It was

observed that MacLeod had been enjoying new-found wealth, settling several long-term debts and acquiring large quantities of whisky, and he was arrested. But no firm evidence could be found to convict MacLeod until, a month before his trial, a tailor’s apprentice from Clashnessie, Kenneth Fraser, claimed that it had been revealed to him in a dream where the peddler’s pack was hidden, by MacLeod’s house. A search was made and a small collection of Grant’s goods were found. MacLeod was subsequently found guilty, and made a full confession before a crowd of over 7,000 people in Inverness before being hanged on 24 October 1831. Although some were to credit Kenneth ‘the Dreamer’ with second sight, others had a more prosaic explanation. Kenneth had earlier been invited to a two-day drinking bout paid for by Hugh MacLeod, and perhaps details were inadvertently revealed…?

“This hand-drawn sketch map shows the location and details connected to a brutal robbery and murder.”G Burnett, Sketch of the grounds in the Parish of Assynt relative to the murder of Murdoch Grant, 1830. Image courtesy of Sutherland Estates. View

Many people will know you as the enthusiastic presenter of several TV series about geology and Earth sciences. How did that impact on your career?

My life has changed a lot since I started in TV in 2004, when I made the big switch from academia. I had this parallel world going on between academia and telly which ran to about 2015. I think TV changes you because the TV requires you to see the bigger picture. I remember going in to pitch some ideas to this production company. To my astonishment they said, “Okay, that’s all very interesting. That would be the first ten minutes of a one-hour show – what else do you have?”

I thought, “Oh my goodness, that’s my whole year’s lecture programme I’ve just given you.” Basically, TV is a sponge – it just soaks stuff up, so you have to constantly get broader and broader. So then I started putting these weird connections together. I joined RSGS in 2012, and of course the thing about geography is that it’s everything. Geography allows you to dabble in all sorts of things that are all very interesting –from the physical, economic and social all the way through to the political – so I started embracing all of that. What do you think has changed in the time that you’ve been RSGS President?