you

makes a difference. And you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

you

makes a difference. And you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

The National Health Service (NHS) has been in the news a lot of late, not just because of the obvious pressure created through the pandemic, putting staff and resources under severe pressure and leading to all sorts of knock-on consequences in the availability of wider health services, but also because of the ageing population, austerity, staff shortages, stress, increasing incidents of violence against staff, and the costs of new treatments and technology.

According to the UK Health Secretary Sajid Javid, one in nine of the population in England is on a waiting list for hospital care, and despite a two-year recovery plan this is likely to grow before it gets better. In Scotland this figure is slightly better, at closer to one in ten (just over 400,000). Additionally, Shadow Health Secretary Wes Streeting claimed there were 93,000 staff vacancies. In Scotland, the Royal College of Nursing reported in November 2021 that there was a record high shortfall of 3,400 nurses (which rises to 5,000 if you count all vacancies for registered nurses, midwives, and healthcare support workers).

I have friends and family in the health-service, and every one of them talks of low morale, burnout and, for far too many, a desperate urgency to retire as soon as possible. I know the health service isn’t alone in all of this, but it does not feel healthy, and an unhealthy health service is surely in nobody’s interest.

So, is the health service healthy and happy? Are the claims of its demise or creeping privatisation exaggerated? Are there trends we should be more conscious of, or issues we need to raise awareness around? And how does our health service compare with other countries?

The health service, alongside freedom of speech and a free press, is one of the values people hold most dearly about the UK. So much so that an homage to the NHS formed the centrepiece of the opening ceremony of the London Olympics in 2012. And during the early part of the pandemic, many of us took to the streets to clap health workers (and other front-line workers) for their invaluable contribution to society. This edition of The Geographer, then, is in a small way our thanks to the NHS for all it has done over the past two years and all it continues to do.

Mike Robinson, Chief Executive, RSGS

RSGS, Lord John Murray House, 15-19 North Port, Perth, PH1 5LU tel: 01738 455050 email: enquiries@rsgs.org www.rsgs.org

Charity registered in Scotland no SC015599

The views expressed in this newsletter are not necessarily those of the RSGS.

Cover image: 2012 London Olympic Games Opening Ceremony. Julian Simmonds / Shutterstock

Masthead: A beautiful winter’s morning at Lake Camp, Hakatere Conservation Reserve, Canterbury. South Island. © Rach Stewart

RSGS:

Almost 800,000 trees, including Scots pine, birch, aspen, holly, rowan and oak, have been planted at Beinn Eighe National Nature Reserve near Kinlochewe since it was established in 1951. Woodland cover has increased by over 40%, creating ‘corridors’ that connect fragments of ancient woodland, allowing animals to move more freely, helping to combat climate change, and increasing local biodiversity.

This year, the main planting phase will end with the last 20,000 trees. In future years, natural regeneration will help expand the woodland further, and NatureScot will only use targeted planting for under-represented species in areas where there is no seed source.

Due to the local oceanic climate, the woodlands at Beinn Eighe are classed as temperate rainforest. Many such forests around Europe are degraded due to pollution or mismanagement, but Scotland has some of the best examples of the habitat anywhere in the world.

Dutch engineers have solved one of the biggest hurdles towards a sustainable future – how to store excess renewable energy generated when weather conditions are favourable, and release it on demand. Developed by Ocean Grazer (oceangrazer. com), the Ocean Battery is an energy storage solution for offshore wind farms. Installed at the seabed at the source of power generation, and based on hydro dam technology that has proven itself for over a century as highly reliable and efficient, Ocean Battery provides eco-friendly utilityscale energy storage up to GWh scale.

To store energy, the system pumps water from the rigid reservoirs into the flexible bladders on the seabed. The energy is stored as potential energy in the form of water under high pressure. When there is demand for power, water flows back from the flexible bladders to the low-pressure rigid reservoirs, driving multiple hydro turbines to generate electricity.

a better way to see the world

“Bound by paperwork, short on hands, sleep, and energy… nurses are rarely short on caring.”

Sharon Hudacek, nurse educator

In November, we were pleased to present Keith Anderson, Chief Executive of Scottish Power since 2018, with RSGS Honorary Fellowship, in recognition of his role as a leading representative of industry in the climate discussion, and for leading the transition of Scottish Power to 100% renewables, helping in Scotland’s journey towards becoming net zero by 2045. Recently, he was behind the demolition of Scotland’s last coal power station, Longannet (see page 27).

2021 was an incredibly busy year, but we have plans to ensure 2022 is successful too. We get opportunities to input to all sorts of policy work and discussions, and it is difficult not to, when we get so excited about the universality of geography and the need to problemsolve and engender action on so many complex issues and wicked problems. So we will continue to embrace opportunities that pop up. However, our main focus for 2022, beyond the usual talks, magazines, medals, various advisory roles, conferences and events, will be around two key priorities: education and climate change.

On education, we will continue to support young people and teachers, build online and CPD activity, input to curricular discussions with Government, represent views in national fora and with education bodies, work with other scientific societies to develop collaborative thinking, push for more choice and a higher profile for all things geographical, and look at how we can drive the profile of Geography in early school years and the uptake of Geography in senior phase and university. In addition, we will always work to push scientists and geographers into direct policy discussions and consultations.

On climate change, our Climate Solutions course is still growing, we are seeing a lot of interest in offering more to businesses and organisations trying to put plans in place, and we hope we will see more internationalisation of this over the coming months. In addition, we will continue to work in a number of other key climate areas, the most obvious being the three other topics where action is so essential – agriculture, transport and cities. To find out more please check out our website under ‘What We Do’.

Because of growing success and workload, we are now advertising for an additional member of staff to fill a new post of Deputy Chief Executive. This person will support our Chief Executive, Mike Robinson, particularly in expanding RSGS’s public-focused and policy-related work, and in fundraising and financial management. The person appointed will focus initially on helping us to significantly increase uptake of our major Climate Solutions training programme, and then increasingly transition into the many broader aspects of RSGS’s work at a senior level.

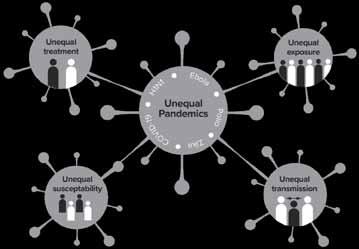

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a major threat to human health around the world. A comprehensive assessment of the global burden of AMR, published in The Lancet at doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0, found an estimated 4·95 million deaths associated with bacterial AMR in 2019, including 1·27 million deaths attributable to bacterial AMR. In the global study of 204 countries, the team of international researchers estimated the allage death rate attributable to resistance to be highest in western sub-Saharan Africa (27·3 deaths per 100,000) and lowest in Australasia (6·5 deaths per 100,000). Lower respiratory infections accounted for more than 1·5 million deaths associated with resistance in 2019, making it the most burdensome infectious syndrome. For comparison, researchers estimate that, in the same year, AIDS caused 860,000 deaths and malaria caused 640,000.

In November, we were pleased to present RSGS Honorary Fellowship to Lee Craigie, Active Nation Commissioner for Scotland. Working closely with the Scottish Government and leading NGOs to champion active travel and the outdoors in a wide range of policy fora, Lee has helped ensure that walking and cycling are accessible and inclusive for all, and as a figurehead and policy lead she has helped increase the budget for active travel in Scotland. She has demonstrated support for the promotion of physical activity for marginalised young people and girls, and has advocated for the environment and decreasing carbon emissions.

Covid has caused huge disruption in schools, particularly around the potential for outdoor and experiential learning. As restrictions start to be lifted, having the courage to start planning these activities again is a judgement being made in schools across the country. The importance of residential trips cannot be underestimated and, as always, Geography teachers are at the vanguard of developing these opportunities.

It looks like formal examinations will also run this May for the first time in two years. It is with some relief that the pressure of making these judgements has been removed from teachers, but there is still some uncertainty. The Scottish Qualifications Authority is providing a range of different support measures and guidance, but the details of these will not be released until early March. Geography is one of the earliest exams this year, taking place on 27 April, and for many pupils this will be the first formal exam they have ever sat. The RSGS-produced Chalk Talk summary videos are being well used for revision and to fill any gaps in learning, and continue to be a resource valued by teachers, parents and pupils, being viewed over 18,000 times.

According to research by campaigning organisation Climate Emergency UK, more than one in five of all councils in the UK have no climate action plan. Out of 409 local authorities, 84 had no climate action plans, while 139 had not committed to achieve net zero emissions by a specific date. Climate Emergency UK scored 325 plans according to 28 questions based on how well councils’ plans would help mitigate climate change locally, the extent to which climate was integrated into existing policies, community engagement, climate education, scale of emissions targets, and commitments to tackle the ecological emergency. High scores included 91% for Somerset West and Taunton, 89% for West Midlands, and 87% for Manchester City.

The Scottish explorer and plant-collector Isobel Wylie Hutchison is attracting a lot of attention just lately, particularly with documentary-makers. I have been asked to give some background information on her travels and experiences by three separate film-making teams, who intend to produce documentaries for television. These documentaries will either focus entirely on Isobel, or include her as part of a wider theme. I believe that filming on all these projects will take place this year.

Isobel is one of Scotland’s most underappreciated explorers, and her expeditions in the 1920s and 30s to Greenland, Alaska and Arctic Canada deserve much wider recognition. I’m very glad that her story is going to be shared with wider audiences.

Since 1890, RSGS’s prestigious Medals have allowed us to celebrate outstanding contributions made by individuals in a wide range of geographical fields. And among learned societies, RSGS is unusual in that our Fellowships are honorary, bestowed solely in appreciation of achievement. These awards help us publicly recognise some of the best in humanity, project the importance of geographical endeavour, build our connections with some of the most influential minds of our day, and thank those who push the boundaries, promote kindness, and provide inspirational role models.

We have been able to carry out this work in large part thanks to a fund established by Agnes Livingstone-Bruce, who endowed the very first medal back in 1901 in memory of her father, the explorer David Livingstone. This led to the establishment of the Inspiring People Fund, which supports the costs of administering today’s programme of awarding Fellowships and Medals.

But after 120 years, we need to replenish this fund to ensure that we can keep making these important awards. And so we are launching a fundraising appeal which will be sent to our members and posted on our website. Please look out for this appeal, and please support us if you can.

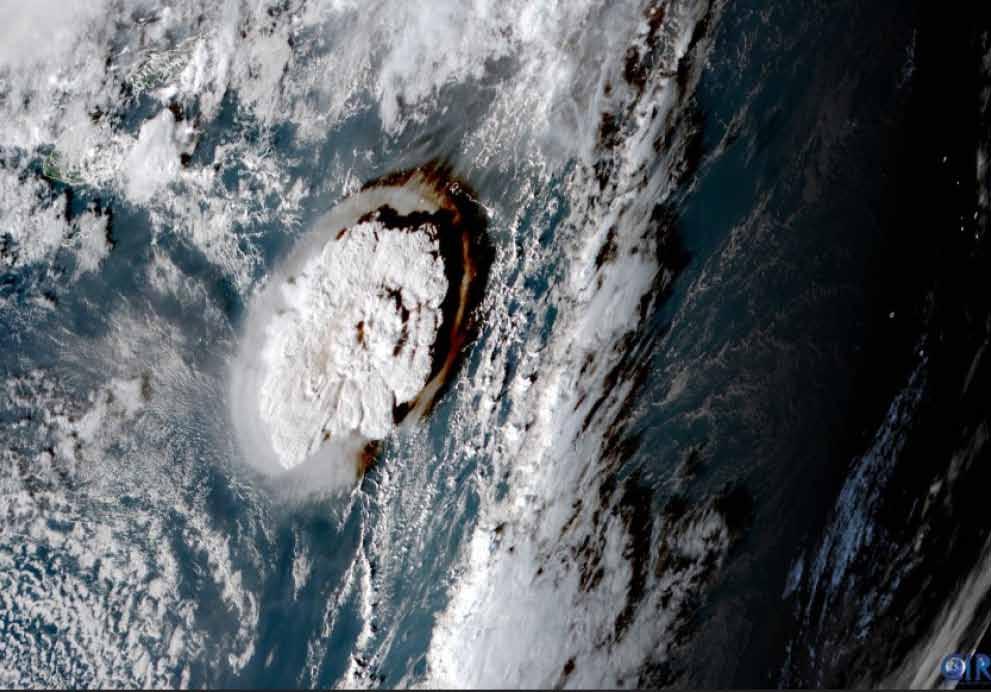

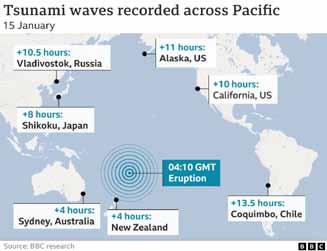

In January, Tropical Cyclone Ana caused extensive disruption across Southern Africa as torrential rains and heavy flooding resulted in more than 80 deaths and left tens of thousands of people homeless. The storm formed over western Madagascar and then hit northern and central Mozambique and Malawi. Heavy rains caused overflowing rivers, floods and landslides, which resulted in casualties and widespread damage.

Malawi experienced copious amounts of infrastructural damage, with roads destroyed by rapidly flowing floodwater. President Lazarus Chakwera declared a state of disaster in areas affected by the cyclone, and appealed for humanitarian assistance for essential items such as tents and food.

A spokeswoman for the World Food Programme highlighted some of the impacts, including damage to agricultural land, key infrastructure and houses, causing loss of life and livelihoods, adding, “Southern African countries have been repeatedly struck by severe storms and cyclones in recent years that have impacted food security, destroyed livelihoods and displaced large numbers of people.”

Several parts of Africa have experienced destructive flooding over the past year, as they deal with the twin issues of prolonged drought and increases in rainfall intensity, which together create prime flooding conditions. The continent is projected to experience a greater frequency of heavy rain according to the latest IPCC report, meaning that the region impacted by Cyclone Ana is projected to see an increase in such events as global temperatures continue to rise.

Nadia Whittome MP is sponsor of a Private Members’ Bill going through the UK Parliament, to require matters relating to climate change and sustainability to be integrated throughout the curriculum in primary and secondary schools and included in vocational training courses. She said, “the education system should be helping young people get informed on the impacts of climate change.”

Some students have voiced their frustration at the lack of opportunities to discuss climate change in classes and the lack of resources available, and teachers have described feeling like they are pressured to be cautious when talking about the climate crisis and unequipped to teach what can be considered a controversial subject.

A spokesperson from the Department of Education said that “by 2023 all teachers in all phases and subjects will have access to high-quality curriculum resources so that they can confidently choose those that will support the teaching of sustainability and climate change.”

please support us© RSGS Collections

We continue to make weekly additions to our blog (www.rsgs. org/blog), covering a range of interesting topics and news. Recent posts include:

Sir Fitzroy Maclean: Escape to Adventure – the legendary Scottish soldier considered to be one of the inspirations for Ian Fleming’s James Bond undertook a hair-raising mission in Benghazi.

A Sleigh Ride in the Snow – when the weather outside was frightful, Captain Fred Burnaby was pole-vaulting across the Volga and battling across the frozen Kazakh steppe in a sleigh drawn by three camels.

A Fruitful 2021 at RSGS – as we entered into a new year we reflected on some of RSGS’s activities and achievements during 2021.

Isobel Wylie Hutchison: Toasting Rabbie Burns in Greenland –“It is Burns Night! Can one be the only Scot in Greenland and forget to celebrate such a festival? One cannot!” said Isobel Wylie Hutchinson as she celebrated the famous poet in Greenland in 1929.

Following the decision to postpone face-to-face talks for the second half of the season due to ongoing Covid-19 restrictions and limitations, our revised online programme got underway in early January, with the first talk – Tim Marshall speaking on The Power of Geography – attracting over 500 households! We are delighted with the general numbers joining us every week.

The revised online programme will continue until the end of March and, with relaxing conditions, we are hopeful of returning to faceto-face talks in September. As always, we are grateful to all of our members and others who have continued to support us throughout these times. We look forward to your continuing support and to welcoming you back to in-person events when it is safe to do so. Please visit rsgs.org/events for details and to reserve tickets for forthcoming talks in the online programme.

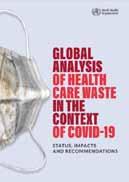

Tens of thousands of tonnes of extra medical waste from the response to Covid-19 has put tremendous strain on health care waste management systems around the world, threatening human and environmental health and exposing a dire need to improve waste management practices.

A new report (www.who.int/publications/i/ item/9789240039612) from the World Health Organization (WHO) bases its estimates on the c87,000 tonnes of personal protective equipment that was procured between March 2020 and November 2021 and shipped to support countries’ urgent Covid-19 response needs through a joint UN emergency initiative. Most of this equipment is expected to have ended up as waste. The authors note that this just provides an initial indication of the scale of the problem; the report does not take into account any of the Covid-19 commodities procured outside of the initiative, nor waste generated by the public, like disposable masks. “Covid-19 has forced the world to reckon with the gaps and neglected aspects of the waste stream and how we produce, use and discard our health care resources, from cradle to grave,” said Dr Maria Neira, Director, Environment, Climate Change and Health at WHO.

In November, a scientific research mission supported by UNESCO discovered one of the largest coral reefs in the world off the coast of Tahiti. The pristine condition of, and extensive area covered by, the rose-shaped corals make this a highly valuable discovery. “It was magical to witness giant, beautiful rose corals which stretch for as far as the eye can see. It was like a work of art,” said French underwater photographer Alexis Rosenfeld.

“To date, we know the surface of the moon better than the deep ocean. Only 20% of the entire seabed has been mapped. This remarkable discovery in Tahiti demonstrates the incredible work of scientists who, with the support of UNESCO, further the extent of our knowledge about what lies beneath,” said UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay. See ioc.unesco.org/news/rare-coral-reef-discovered-near-tahitiunesco-mission for more information.

The Geography world lost a champion with the death last summer of Leslie Hunter FRSGS. Born in Glasgow, Leslie started teaching at Alloa Academy on 1 April 1961. That year he also married Val, his wife for almost 60 years. After further spells of teaching in Wick and Edinburgh, he became a lecturer at Moray House College of Education, training young Geography teachers.

In 1975, Leslie was appointed Geography specialist HMI, a post which offered him further challenge and satisfaction in his beloved subject. He oversaw the introduction of Standard Grade and Revised Higher, and produced the excellent Effective Learning and Teaching in Geography

Leslie was well respected by Geography teachers because he’d experienced Geography at all levels. He understood the subject, and the quirks and limitations imposed by individual schools and local authorities. Subject inspectors help drive up standards by encouraging and building confidence in teachers of all ages and experience. Leslie was the very best exemplar. The idea that school inspections are dreadful things filled with angst was certainly not the case with Leslie. His kindness in setting teachers at their ease during inspections was impressive. For example, he didn’t expect a teacher to continue teaching the prepared lesson when a helicopter landed outside and provided a different interest!

Apart from his trusty HMI briefcase, Leslie had two other essentials, especially on inspections in the Highlands, Western Isles or Northern Isles: his collapsible fishing rod, and his binoculars for bird watching.

Leslie actively supported teachers through the Scottish Association of Geography Teachers, and he served on RSGS’s Education Committee and as Chair of RSGS’s Dundee Group. Leslie didn’t consider himself an important man, but those of us who had the pleasure of knowing him, knew different!

Things have calmed down a bit since COP26 in Glasgow and the follow-up to that; it feels a long time ago that we were bouncing between coordinating and chairing events, media interviews, extra publications and hosting various visitors. And although it is not as hectic, we are still very active. We have given talks to external bodies, including the International Development Alliance, Scottish Enterprise, and several Chambers of Commerce. In January, we were delighted to address the staff conference for Sistema, an organisation for which we have a high regard. We look forward to working closely with all of them as the year progresses.

We gave evidence to the Scottish Parliament’s Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee, to debrief them postCOP26. We met with the Historic Towns Trust, looking at developing historical atlases of Scottish towns and cities. We continue to be represented on the Scottish Government’s Agriculture Reform Oversight Implementation Board. And we are talking to the Explorers Club of New York about future joint working. So there is lots to get our teeth into over the course of 2022.

If you would like to know more about any of these work areas, or to get involved, please drop us an email on enquiries@rsgs.org

Within the crises of climate change and biodiversity loss, the role of cities is becoming ever more prominent. According to the World Bank, some 55% of the world’s population currently live in cities and this is expected to increase to 70% by 2050. In their 2020 report on urban development, they say, “Once a city is built, its physical form and land use patterns can be locked in for generations, leading to unsustainable sprawl. The expansion of urban land consumption outpaces population growth by as much as 50%, which is expected to add 1.2 million km² of new urban built-up area to the world in the next three decades. Such sprawl puts pressure on land and natural resources; cities consume two-thirds of global energy consumption and account for more than 70% of greenhouse gas emissions.”

This increased emphasis globally on the role of cities is a vital area of future sustainable development. RSGS has been working through Perth City Leadership Forum to convene discussion about how a smaller city like Perth, with advantages of scale and good environmental integrity, can play more of a role. We hope to help deliver projects which can make Perth more resilient, prosperous and net zero; and, by doing so at city and area scale, provide example and experience to inspire other cities to develop too.

In January, we ran a biodiversity conference featuring the Mayor of Lahti in Finland, European Green Capital of 2021, Elizabeth Mrema, Executive Secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity, and an array of other speakers from around the world. Over 200 people and organisations attended, and we hope good things will follow. As Elizabeth Mrema said, “your work will be an inspiration for other cities.” See mostsustainablecity.com for more information and to watch the speeches.

Rivers have captivated wildlife writer Keith Broomfield since childhood: special serene places where nature abounds and surprises unfold at every turn. If Rivers Could Sing is his personal Scottish river wildlife journey, in which he delves deeper into his own local river – the River Devon as it flows through the counties of Perthshire, Kinross-shire and Clackmannanshire – to explore its abundant wildlife and to get closer to its beating heart.

Jo Woolf FRSGS, RSGS Writer-in-Residence

Jo Woolf FRSGS, RSGS Writer-in-Residence

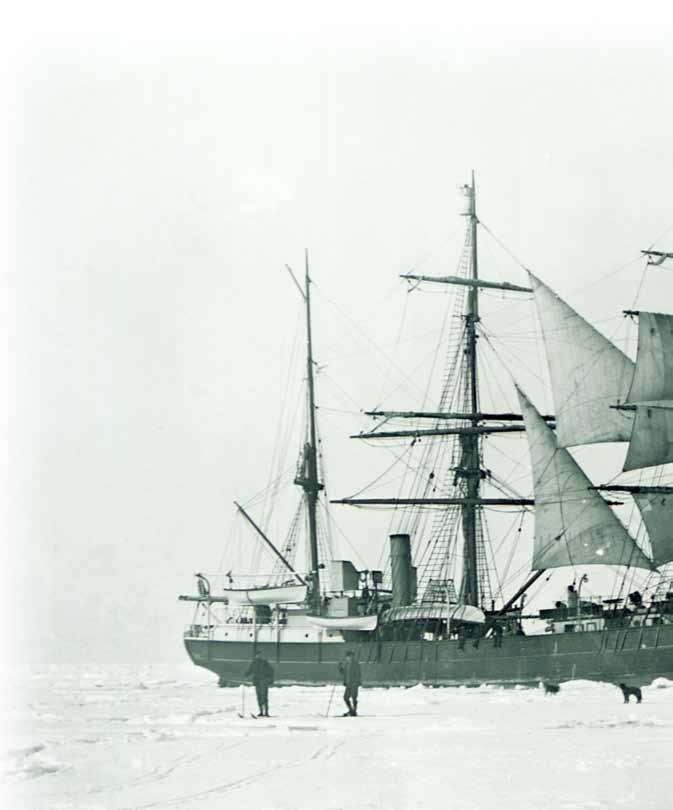

The Shackleton Museum in County Kildare, Ireland, has established an annual event called the Ernest Shackleton Autumn School. For the last couple of years this event has been held online in the form of live-streamed presentations by guest speakers on all aspects of Shackleton’s story. I was invited to take part in last year’s event, called Virtually Shackleton 21, on 30 October. My talk, entitled Sir Ernest Shackleton at the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, focused on Shackleton’s time as Secretary of RSGS and was illustrated with some of our much-loved artefacts, such as his CV and photographs of the Endurance before it set sail. All the talks are available to view online, on the Shackleton Museum’s YouTube channel, ’Shackleton Museum Athy’, at www.youtube.com/ watch?v=Q2jc4t6STTY

We were delighted to participate in the Royal Society of Edinburgh’s inquiry panel which ran during late December and early January, responding to the UK Parliament consultation on ‘Aligning the UK’s economic goals with environmental sustainability’. There is broad consensus on the need to find more suitable economic indicators than GDP, and the need to begin to cost current externalities, but there still remains a good deal of debate about how best to do that, which measures to back, and how to begin challenging the primacy of GDP in government thinking and public discourse.

The Scottish Government Climate Assembly, a group of over 100 citizens from all backgrounds tasked with outlining recommendations on how Scotland should change to tackle the climate crisis effectively and fairly, will soon be coming to an end. The Assembly has commended the Scottish Parliament for bringing the Assembly together, and for taking its 81 recommendations into consideration. Just some of the recommendations highlight the importance of shared goals and targets, prioritising the most pressing climate issues, fair access to public transport, and the necessity of climate education to succeed in our collective mission in Scotland towards net zero.

In November, we were delighted to present RSGS Honorary Fellowship to Professor Ed Hawkins, a leading climatologist from the National Centre for Atmospheric Research at the University of Reading, a lead author for the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report on the physical science of climate change, and designer of the climate ‘warming stripes’ graphics. Ed received his Fellowship certificate at one of our Meet the Experts events, monthly online Q&A sessions with sustainability experts.

In January, RSGS Chief Executive Mike Robinson spoke with The Herald for its Climate Conversations podcast, discussing a wide range of topics, from Scotland’s position as a leader in climate change to the importance of political will globally. Together with podcast host Marc Strathie, he considered the industries that have a significant impact on the feasibility of achieving net zero by 2030, and how RSGS is helping to bring people up to speed on climate change as quickly as possible. The hour-long podcast can be found at shows.acast.com/climate-conversations

In February 2020, First Nations representatives from British Columbia joined more than 500 participants from 50 countries in Mexico City to discuss a roadmap for the Decade of Indigenous Languages which officially began at the start of 2022. The resulting Los Pinos Declaration places Indigenous peoples at the centre of its recommendations, under the slogan ‘Nothing for us without us’. In its strategic recommendations for the Decade, the Los Pinos Declaration emphasises Indigenous peoples’ rights to freedom of expression, to an education in their mother tongue, and to participation in public life using their languages, as prerequisites for the survival of Indigenous languages, many of which are currently on the verge of extinction.

See en.unesco.org/news/pinos-declaration-chapoltepek-lays-foundationsglobal-planning-international-decade-indigenous for more information.

Uptake of our Climate Solutions course continues to go well. It has been great to see that a large number of staff from all three enterprise networks (Scottish Enterprise, South of Scotland Enterprise, and Highlands and Islands Enterprise) have now completed the course. We have more interest from overseas, with Outward Bound Oman adopting both the Climate Solutions Accelerator course and the Scotland: Our Climate Journey film for training young people in Oman about all things climate-related. We have had a lot of interest from existing participant companies in rolling out access to the course to their entire supply and customer chains. And each Wednesday, The Herald newspaper has featured an article with testimonials and experiences of participants in the course, and some of the wider issues surrounding climate solutions adoption. Here is a sample of recent feedback: “I have been really struck with the impact the course has had on quite a number of participants. While we hoped the course would help raise understanding across the board, it’s gone well beyond these expectations – so thank you to the whole team once again.” And another piece of (too?) honest feedback: “I thought the course was very good indeed; frankly, much better than I expected it to be! I’m no climate change denier but I find a lot of the material on climate change to be annoyingly preachy and self-righteous. This wasn’t; it was interesting and informative and it made me think.”

We want anyone and everyone to undertake the course in order to encourage a universal understanding of this critical issue. Please visit rsgs.org/climate-solutions to learn more.

visit rsgs.org/climate-solutions

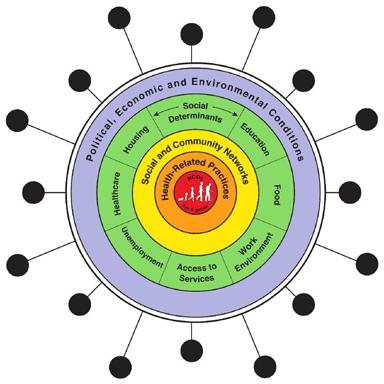

Geographers should be interested in what is happening to the NHS because it is through making geographical comparisons with other countries that we can see that its current decimation is unnecessary. The claim that there is no alternative but to spend less can be disproved by considering how other very nearby countries manage to spend more. Furthermore, there is a geography to the cuts that have taken place in the UK which reveals where is prioritised and where is not. Finally, very local geographical stories, such as two briefly told here from Oxford and Glasgow, can also help reveal what is going on.

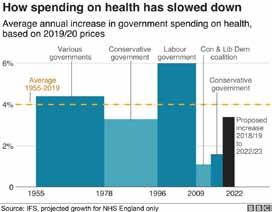

On 9 January 2020, the BBC published a news story entitled ‘11 charts on the problems facing the NHS’. The second of those charts (Figure 1) shows how cuts in spending increases for the NHS began in earnest in the late 1970s, were briefly reversed for 13 years after 1996, but then began again after 2009. All of these changes were political choices, as the labelling of the graph makes clear, although there had been something of a political consensus between 1955 and 1978 when spending increases were usually above 4% a year regardless of the political party in power in the UK.

A spending increase of 4% a year does not mean an actual improvement in service; it often means just holding the line. This is especially so today when the population is ageing far faster than it was in the 1960s or 1970s. That BBC article went on to show that spending on health care in the UK is much lower as a proportion of GDP than it is in France and Germany, and that is even the case when private health spending is included. It also showed that there was little difference in outcomes in the different countries of the UK, almost certainly because spending across them varies so little as compared to spending across Europe. In 2017, health spending in the UK as a whole, including all the spending on private hospitals, was almost identical to the EU average. Today it will almost certainly be less than that average, not least as other countries in Europe have responded with a larger increase in emergency spending due to the pandemic. This is alongside the now usually higher increases in health spending that most other European countries are making as they bolster up their health services more widely. In contrast, the UK government plans to reduce public spending overall once the pandemic has subsided, as illustrated by the submissions it has made to the International Monetary Fund on planned future public spending.

The final graph the BBC published in their series of 11

illustrates one theory as to why these choices have been made. That graph (Figure 2) shows that patient satisfaction with the NHS was falling until 1997, then rose as public spending rose, to a high of 70% being ‘very or quite satisfied’ in 2009, before falling again afterwards. Satisfaction with the NHS tends to track how well the NHS is able to cope, which in turn is largely determined by how well it is funded and organised.

Why would some politicians instigate changes in funding that inevitably result in a fall in satisfaction with the NHS? These politicians often say that a continuation of funding increases could not be maintained. That clearly was not the case as other countries in Europe chose differently despite suffering similar economic shocks at particular times. Geographical comparisons are a key way in which you can determine if the politicians are lying to you about what is possible, as compared to what they are choosing to do.

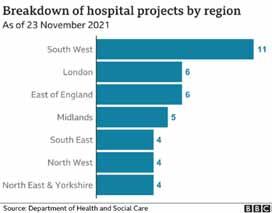

Of course, there is always some part of the UK that is receiving a greater increase in health funding, or less of a decrease, at any one time. Politicians tend to point to the increases to say that they are doing something substantial. It is well known that the UK government has promised “40 new hospitals” in England. What is less well known is that hardly any of these hospitals are new; most are extensions to (or rebuilding on) existing sites, but even here there is a clear geographical pattern to what is planned as yet another graph

“A spending increase of 4% a year does not mean an actual improvement in service.”

(Figure 3), published by the BBC on 1 December 2021, makes clear. The 40 planned projects are concentrated in the South West of England; although as the BBC story that accompanied that graphic made clear, there are now doubts as to whether most of those will happen on time. More importantly, even if the planned projects were to all be completed, they would not reverse the decimation that has been occurring more widely, or even begin to address the increase in need that comes as we age and become more frail overall. Neither would they begin to cope with the health legacy of a pandemic and a disease which is becoming endemic, resulting in greater levels of illness than before for an as-yet-unknown number of years to come. What is going on? I grew up in the city of Oxford in England at a time when the NHS was well funded and in a city with a surfeit of public hospitals. I left the city when I was aged 18 and returned nine years ago. One of many shocks on returning was discovering what had happened to the old ‘Manor’ ground where Oxford United used to play. It now housed a brand-new private hospital, built walking distance from the old public hospitals so that consultants who chose to do part private work could walk over with ease. Before the private hospital had been built, there had been much less opportunity to expand the private health sector in the city. Later I discovered that some Oxford colleges offer to fund private health insurance for their academic and other staff. Something dystopic was happening, however slowly and gradually, so that each of us can tell a story of the dismantling of public health care, but few of us can see the overall orchestration underlying this.

In January 2020, it was quietly announced that a new £20 million private hospital had been opened just off the Old Govan road in Glasgow. The ‘Ross Hall Clinic Braehead’ was described as “state-of-the-art” by the Daily Record. Nestled on an industrial estate between an accountancy firm and a computer shop, and opposite a new charging station for electric cars, “The new hospital includes 17 new consulting rooms, a new MRI scanner alongside new respiratory, colposcopy and urodynamic departments. The inclusion of these key additions will mean that an extra 200 outpatients a day will be able to receive care from clinical specialists.” But of course only a few people will be able to afford to use these services, and others will rely on the NHS sending them there, if it is able to do so.

The pandemic could have begun a sea-change in the direction of health care and healthcare spending across the UK. Many private hospitals would not have survived it had they not been supported by state contracts and emergency funding to keep them solvent. We could have nationalised most of

the new private facilities, at almost no cost – given that they were no longer solvent. Instead they were supported, kept alive for when they could begin could begin fully operating; and new private facilities were built during the pandemic.

In relation to the growth in need, healthcare spending has been decimated across the UK. One reason this is allowed to happen is because a small but growing proportion of the population can afford to bypass the ever-lengthening waiting lists; they do not have to worry about what will happen to them if and when they fall ill. They receive an increasingly better level of service as compared to what most people can access. And the politicians who have presided over this growing social and health divide are not unaware of this. In fact, they are often lobbied by private healthcare companies or have even more direct involvement than that.

Why should British geographers care about any of this? One reason, perhaps the most trivial, is that it will affect the maps of health outcomes for many years to come, to the extent that differential health and social care is part of the reason as to why people live shorter lives in some areas rather than others. A less trivial reason is that even if they are not worried about the direction their society is travelling in generally, they could worry about themselves. A recent RGS-IBG survey found that 51% of students who go on to study Geography at university do so because they rank “earning a good salary” as important (while only 19% said they ranked “doing ‘good’ through my job” as important). However, only a minority, even of that 51%, will ever earn enough to be able to afford private health care.

“Each of us can tell a story of the dismantling of public health care.”

University of Birmingham

University of Birmingham

The state of the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK has always been the subject of debate, which often generates more heat than light. Two elements have often been linked: ‘privatisation of the NHS’ (over 933,000 Google hits) and ‘end of the NHS’ (a mere 203,000 Google hits). However, both of these debates have long histories. For example, Aneurin Bevan, the Minister of Health who created the NHS in 1948, wrote in his book In Place of Fear (1952) that recently announced legislation would ‘mutilate’ the service. More recently, government critics have ‘cried wolf’ at almost every NHS reorganisation since 1989. This article explores privatisation in health and social care, with reference to differences within the UK.

The definition of privatisation is contested, with the term used in many different ways along a continuum. The ‘minimal definition’ tends to be used by Government, and is largely concerned with ‘finance’, with services free at the point of use: we are not privatising the NHS because treatment remains (largely) free. The ‘maximal’ definition tends to be used by critics, and refers to any movement from public to private in provision, finance or regulation. In terms of provision or ownership, it is often considered that the NHS is fully public. However, it has always contained some private elements. For example, GPs, dentists and opticians are independent contractors (or small businesses). Put another way, it was only the hospitals that were nationalised.

In terms of provision, the term ‘creeping privatisation’ has been used since the 1980s, but it is creeping fairly slowly, currently amounting to some 10% of the NHS budget. However, this varies by sector. For example, while acute hospitals still remain public, areas such as general practice, mental health and hospice provision have always been less public.

Turning to finance, some regard the NHS as being (largely) free at the point of use because the most important and costly element – hospital treatment – is free. However, there have been some charges almost throughout the period of the NHS, such as charges for prescriptions, and optical and dental treatment. Bevan resigned from the Labour Cabinet in 1951 in protest about charges. Charging has broadly increased over time. There is some variation between the UK

nations. For example, Wales has free prescriptions. Scotland has free dental examinations for all, but requires payment up to 80% of cost to a maximum of £384 (with free treatment for particular groups such as those aged up to 26).

The final criterion of regulation is more difficult to assess. Regulation can act as a counterweight to provision: that if (a big if) properly regulated, then ownership does not matter. However, it could be said that we have more regulators (eg, Care Inspectorate in Scotland) but insufficient regulation.

The main problem of crying wolf with the NHS is that few took much notice when the wolf appeared for Long Term Care (LTC) which has now been significantly privatised. Unlike the NHS, LTC has always relied on significant amounts of ‘informal’ (unpaid, and often female) care, and has been subject to means testing, but originally in 1948 charges were set at similar levels to pensions. There has been a huge explosion in private provision since the 1990s. There have also been huge levels of debt for ‘self-payers’, which has led to people selling their homes to pay for care.

LTC exhibits perhaps the most obvious differentiation linked to political devolution. The Royal Commission into LTC, set up by Tony Blair, recommended free ‘personal care’ in 1999, which was rejected in England, but taken up by Scotland to provide free ‘personal care’ (but ‘hotel charges’ remain). In England, the Conservative government’s promise to ‘fix’ social care has resulted in a cap on lifetime costs on personal care, which will mean that some people will still have to sell homes. In Wales, a Labour / Plaid Cymru alliance has promised a ‘National Care Service’ (NCS) to provide ‘free’ social care within three years. In Scotland, the First Minister wished to build a “social care legacy equal in stature and impact to the creation of the NHS after World War 2.” The Feeley Review (2021) recommended an ‘NCS’ within a ‘human rights approach’. However, unlike the NHS, nationalisation or public ownership was ruled out. An NCS is clearly meant to be compared with the NHS. Bevan was very clear what an NHS meant. The term NCS should not be used if it is not free at the point of use (minimal definition, above) or publicly owned (maximal definition), and is not ‘in place of fear’.

Professor Martin Powell, Professor of Health and Social Policy,

“It is often considered that the NHS is fully public. However, it has always contained some private elements.”© Luke Jones

, Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Dean, Otago Business School; Co-Director, Centre for Health Systems and Technology, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

, Pro-Vice-Chancellor and Dean, Otago Business School; Co-Director, Centre for Health Systems and Technology, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

Readers familiar with the UK NHS (the NHS) will find much in common with New Zealand’s health system. There are also some important points of difference. The two both have so-called national health systems, largely funded by general taxes and delivered through government-owned public hospitals and related facilities. Both also feature private provision, which delivers some public services. New Zealand was the first country in the world to pursue creation of a national health service. This was through the Social Security Act 1938, some ten years ahead of NHS establishment. This Act sought to create comprehensive social services including education, housing and retirement support, along with health care. Health care services were to be nationalised, with all professionals becoming government employees. Instead, in a historic compromise with the then British Medical Association NZ branch, resistant to nationalisation, the foundations of the New Zealand health system today were laid. This permitted general practitioners to retain private ownership and to generate income through patient service fees. It was agreed that the government would subsidise fees which were consequently brought down to a low level. Public hospitals would be free of charge with all professionals on salary fully funded by the government. Public specialists would be permitted to maintain a parallel private practice. Expenditure is today just over 9% of GDP; government provides around 80% of total funding, with the remainder from private sources. The social-insurance-style Accident Compensation Corporation covers injuries.

Over the years, government subsidies for general practice have not kept up with costs, and patient fees have increased to the point they are often prohibitive and a major access barrier. Nonetheless, New Zealand has a strong system of general practice. Those unable to pay often have their fees waived or will attend a public hospital emergency department where services are free. Around 40% of public hospital specialists also retain a private practice. There are no private emergency or intensive care facilities, so private specialty work is dominated by routine procedures such as hip replacements and cataract removal. Like the NHS, waiting lists prevail in public hospitals which are underfunded and face perpetual pressure to improve efficiency. Those with private insurance or ability to pay often seek private treatment where waiting lists are virtually non-existent. Interestingly, the same specialists unable to provide treatment in a timely fashion in the public sector can do so

privately. A significant proportion of elective work is privately provided. Critical backup and support for private patients with complications is provided in the public sector, taxpayerfunded. Patients are also not able to see a private specialist without a publicly-subsidised GP referral.

In contrast with the NHS, New Zealand’s services were built in the context of strong regionalisation which has persisted over time. Decision making and services vary hugely by district, exacerbated by a system of 20 local District Health Boards (DHBs) established in 2000. These have responsibility for service planning and delivery for a geographic area, and fund public hospitals, primary care and disability support services. Some 30 Primary Health Organisations (PHOs), established in 2003, channel government funding into various services and work with general practices for delivery. PHOs in areas with higher populations of Maori, Pacific or lower socio-economic status receive more government funding, which is used to reduce patient fees and improve services for these groups which are more likely to suffer ill health. From 2013, in an effort to integrate care planning and delivery, the government required each PHO to enter into an alliance with the local DHB.

The current arrangements will cease in July 2022 when significant reforms take effect. Guided by the Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act, a new national entity, Health NZ, will take over all DHB responsibilities and centrally plan and fund public hospitals and primary care services. In a first for the country, a new Maori Health Authority will do the same for Maori people. The two new entities will work in partnership, giving effect to core principles of the Treaty of Waitangi signed in 1840 between Maori and the Crown. Public hospitals will be funded separately from primary care. Considerable work is going into building new primary care locality networks, aimed at integrating a range of providers, including social services. A core goal of the reforms is equity and population health through national planning. An obstacle to this, which the reforms will not address, is the underlying institutions of parallel public and private systems, the latter of which does not serve the less well-off.

Gauld R, ‘New Zealand’, in R Tikkanen, R Osborn, E Mossialos, A Djordjevic, G Wharton (eds), International Health Care System Profiles, New York, Commonwealth Fund, 2020 (www.commonwealthfund.org/international-healthpolicy-center/countries/new-zealand)

Professor Robin Gauld

“New Zealand was the first country in the world to pursue creation of a national health service.”

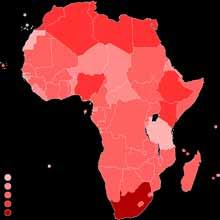

The Covid pandemic has had serious health and economic consequences right across the globe, and no country, it would seem, has been spared. African countries are no exception. Even in some quite remote rural areas in the continent, there have been Covid outbreaks, mainly attributed to migrants returning to villages from work in the urban areas. However, the available data suggest that the direct clinical effects of Covid in Africa may have been less severe than elsewhere. Just over 17% of the world’s population is located in Africa, but Africa has experienced only about 3% of the world’s recorded Covid cases and just over 4% of global deaths. Quite why this is the case is still being debated and researched, but there are two possible explanations being explored. The first is that there has been a significant under-reporting of both positive cases and deaths in many countries. There has been a well-reported shortage of testing kits in Africa, so it would not be unreasonable therefore for there to be an under-reporting. Secondly, there is a view that the relative youth of the African population may be a factor. It is well-established that elderly people are more vulnerable to Covid than younger people, and the median age of the population in Africa is 19.7 years, compared to 40.2 years in the UK. In Africa, only just over 3% of the population is over the age of 65 years; in the UK the equivalent figure is 18%. However, the same cannot be said for the indirect consequences. Many clinics have reported a rise in the incidence of nonCovid diseases as access to primary health care has been impacted. This has been because of lockdowns which have resulted in the reduced availability of transport for people to attend clinics, as well as staff shortages at clinics themselves through staff illness. People in pre-Covid days would have regularly attended clinics when needed, and been tested for malaria, tuberculosis and HIV, among other things, but during the pandemic, testing for these diseases has been much reduced, leading to more serious cases of all three conditions developing before being able to be treated.

Children’s education has also been badly affected. Schools in most African countries have been closed for varying periods of time during the pandemic. In Uganda, schools were closed for over 18 months, for example. Unlike in the UK and other high-income countries, online learning from home has been largely unavailable, except for a very few wealthy, mainly urban families. For the majority, lack of ownership of computers, tablets and smartphones, lack of access to the internet, and, in all too many cases, lack of electricity precluded this as a means of continuing learning outside school. One of the more successful Millennium Development Goals was focused on providing access to universal primary education, with 91% of children in Africa by 2015 receiving a full programme of primary education. Sadly, these gains have been set back by the pandemic, but the full impact is yet to be evaluated, although there is evidence already from some areas that fewer girls than boys are returning to schools when they re-open.

Economic gains over the last couple of decades have also been damaged by the pandemic. The reduction in global demand, especially during 2020, has had a serious impact, especially on those African economies which are more interconnected with the global economy. Reduced global demand for copper, which typically provides about 30% of Zambian government revenues annually, has had a major negative impact on that country’s economy. An important export for Kenya is cut flowers, being Kenya’s third largest earner of foreign exchange in a typical year. In 2020, as the pandemic started to grip the world, exports of cut flowers, most of which are to Europe (mainly to the Netherlands and the UK) declined precipitously from 17,600 tonnes in February 2020 to only 8,000 tonnes in April of that same year. This very much reflected both the cancellation of flights out of Kenya to Europe, the expense of chartering cargo aircraft, and the reduction in consumer demand as weddings and other events and celebrations were curtailed as a result of lockdowns in Europe and elsewhere. As lockdowns eased, the market built up again, but it was not until August 2021 that the volume of exports had recovered to pre-Covid levels. It is estimated that up to one million people depend either directly or indirectly on the cut flower industry in Kenya, and a great many of these lost their jobs and their income.

For those countries where tourism represents a significant element of economic activity, notably South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, Botswana, and increasingly Mozambique and Namibia, the decline in tourist arrivals, and the drop in tourist income, has been calamitous. In South Africa, pre-Covid tourism generated about R130 billion annually (about £6.3 billion), and contributed about 8% of Gross Domestic Product, as well as about 4.5% of employment. In 2019, international arrivals amounted to 10.2 million people, but this dropped to 2.8 million in 2020. In Kenya, where tourism makes up about 8% of GDP, international arrivals dropped from just over two million in 2019 to 568,000 in 2020. Tanzania saw its tourist revenues drop from US$2.6 billion in 2019 to less than US$1 billion in 2020. The impact on national economies, local employment and household incomes, without social security or furlough safety nets, has been severe, and countries are still counting the cost.

Whereas these macro-level impacts have been challenging in the extreme, smallholder farmers at the local level have not been immune from the economic impacts of Covid either. Markets have been closed for periods of time, and transport for inputs has been badly affected, which, in turn, has impacted agricultural production and household incomes in different ways. Experiences from Malawi are very instructive. Although Malawi did not experience a complete lockdown in response to the Covid pandemic, nonetheless there were school closures, restricted opening of marketplaces, gatherings restricted to fewer than 100 people per group,

Dr Boyson Moyo, Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources; Professor John Briggs, University of Glasgow

“Many clinics have reported a rise in the incidence of non-Covid diseases.”

and vehicle capacities reduced to 60%. This had a significant impact on smallholder farmers, sometimes in unexpected ways.

For the majority of small-scale farmers, particularly those who rely on grain production, especially maize, marketing opportunities were severely curtailed as many markets were closed and the movement of those buying agricultural products on sale in towns was also severely restricted. Because of the reductions in the seating capacity of passenger vehicles, and limited sizes of gatherings for mobile markets where major crop produce sales often take place, demand necessarily declined and smallholder farmers’ incomes and livelihoods were badly hit. The Government of Malawi estimated that the country’s agri-food system suffered a loss of 10.4% over the first two months of the pandemic, and although it stabilised after that, it did so at lower than pre-pandemic levels.

Although grain producers were hard hit, ironically a small minority of other smallholder farmers fared quite well. There was a widespread belief among many in the population that crops such as ginger, lemon and green leafy vegetables were key in keeping people healthy and resistant to Covid. Hence, these crops have seen an increase in demand during the pandemic. The challenge, however, for producers was that ginger and lemon production can only come from mature plants, so the increased demand did not directly result in immediate increased production. But for those farmers who were already producing lemons and ginger there was a small and unexpected windfall increase of incomes. Happily, the production of vegetables offered more flexibility as these could be sown and grown quickly, and as restrictions relaxed on marketplaces, those farmers who were able to produce such crops benefitted. An unexpected consequence of school closures was that students who were out of school became useful in agricultural production, not least for the production of vegetables which were in high demand. Labour shortages which in the past might have negatively impacted production were not now, by and large, an issue.

A further unexpected consequence is that there is a view that with people spending more time on their farms instead of in school or in their other jobs because of the pandemic restrictions, this may have had an impact on reducing the spread of the virus. Indeed, with social distancing and the requirement to keep away from crowds in place as part of the government’s response to the pandemic, farms and vegetable gardens provided spaces for safe isolation and social distancing without the need for putting on a mask.

Africa has not escaped the pandemic and the consequences have been significant. How Africa recovers economically is going to be an interesting challenge over the next few years.

“The impact on national economies, local employment and household incomes has been severe.”

Dr Julia Grace Patterson, Chief Executive, EveryDoctor

Dr Julia Grace Patterson, Chief Executive, EveryDoctor

The NHS has just experienced the most extraordinary challenge in its history. The pandemic has heaped enormous pressure upon a service which was already struggling to cope after a decade of government underfunding (during the 2010s, the real terms growth in health spending was the lowest since the NHS’s inception). As a result, both of cumulative underfunding and of treatment delays because of Covid-19, the NHS in England currently has waiting lists of 6.1 million patients. These are the longest ever on record.

One might expect that in the face of such an extraordinary national healthcare crisis, the response from our politicians would also be extraordinary. Extraordinary funding increases. Extraordinary measures to support current staff and recruit new ones. Extraordinary efforts to transform the NHS into a service which truly fits the healthcare needs of the public in 2022. We might expect that having lived through a pandemic which has claimed the lives of over 150,000 people in the UK, healthcare would (finally) be put front and centre of this government’s agenda. Sadly, this does not appear to be the case.

There is much fanfare currently about proposed NHS funding increases, which the government plans to implement until 2024 2025. And yet this increase (which will amount to a 3.5% spending increase in real terms) is lower than funding increases in the 1960s, 1970s, 1990s and 2000s. In short, it’s a much more paltry investment than the government is letting on.

As well as this lukewarm investment in the health of the nation, there is a Bill travelling through the UK Parliament at present called the Health and Care Bill. It is causing enormous concern to NHS campaigners, who believe that the Bill will accelerate NHS privatisation. The Bill involves fragmenting the NHS in England into 42 ‘Integrated Care Systems’, governed by Boards, which look as though they’ll be allowed to give seats to private healthcare providers. There is much discussion about Bill amendments at present, with campaigners and many politicians alike trying to remove the ability of private healthcare providers to occupy these Board seats. Whether or not this is achieved, the Bill has broader and deeper consequences for the NHS. It contains elements which will allow the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care to intervene in local services. It contains a worrying policy called “discharge to assess” which means that a patient can be discharged from a hospital before having an assessment from the services which will provide continuing care for that person in the community. And

it’s bound up in difficult-to-decipher rhetoric which sounds progressive, but has seemingly little in the way of practical detail (the government’s Integration and Innovation White Paper which preceded the Bill talks of putting “pragmatism at the heart of the system” and claims it will “set aside bureaucratic rules”). The thing is, every NHS shake-up contains a great deal of bureaucracy. Old rules will simply be replaced with new rules. And it seems that this particular shake-up will remove some power from experienced local healthcare providers, and transfer it to the Secretary of State. Our current Secretary of State for Health and Social Care has no background in health. Neither did his two predecessors. It is unclear to many of us why a politician in Whitehall would presume to make better decisions for patients than a local clinician.

The Bill is winding its way through Parliament, and at the time of writing (February 2022) is awaiting its third reading and a vote in the House of Lords. It may be voted down, and if so will then have to return to the House of Commons. But quite frankly, even with successive ping-pongs back and forth, tweaking amendments here and there, this Bill is simply the wrong Bill. It does not prioritise the welfare and support of staff who have endured the trauma of the pandemic and the incredible strain of working in an understaffed and underfunded workforce for a decade. It does not consider how that workforce can be buoyed up, grown and nurtured, to provide fantastic care to NHS patients in the decades to come. And it does not appear to tackle the enormous problems of inequitable care across the NHS, which disadvantage many patient groups.

We desperately need a national conversation about the future of public healthcare in the UK. We need politicians to admit to the existence of NHS privatisation (which is embedded, and takes up around 7% of the annual budget in England). We need to think hard about the kind of NHS we want. And it is time, as we emerge from the acute phase of this pandemic, to think radically. The government needs to listen; listen to patients, listen to experts, listen to healthcare providers. It needs to scrap this Bill, and write a better one.

“We desperately need a national conversation about the future of public healthcare in the UK.”

No one I know has set New Year resolutions for 2022 that do not include making Covid history. The latest scourge of Omicron takes us into the third year of seemingly endless disease and death. Yet we now know Covid-cycles of destruction can be broken by vaccination and testing. But vaccination and testing have to happen everywhere if the virus is to be contained. And to bring Covid under control, Boris Johnson and President Joe Biden should appoint a global coordinator. Their task: to urgently transfer the vaccines and testing equipment, that the richest countries currently monopolise, to the poorest countries still without them. Only then, by backing up the work of the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the global vaccines agency, COVAX, can we halt the threat from new variants.

For even as the West has reached 70% adult vaccination, 90 countries have yet to meet the worldwide (end of 2021) target of 40%. In low-income countries the figure is still only 4%. Even now, three in four African health workers, who are risking their lives to save lives, remain unvaccinated. In Africa’s biggest country, Nigeria, which has a population of over 200 million, only one in 50 people (2%) are fully vaccinated. And another huge country, Ethiopia, with over 100 million people, remains frighteningly unprotected, with only 1.2% fully vaccinated. But in some countries, immunisation rates are even below 1%: Chad 0.5%, DR Congo 0.1%. Worse still, in Burundi, the vaccinated account for just 0.04%, just one in every 2,500. With the low coverage, it is not surprising that these countries are fertile grounds for the disease to spread.

It also puts next year’s WHO global vaccination target, of 70% by July, in jeopardy. We’re failing because the richest countries continue to stockpile vaccine and equipment supplies with the result that, even after all of us have boosters, there is a surplus in the richest countries and a shortage in the poorest. Cooperation between rich and poor countries failed so badly in 2021 that 60 million vaccines, that could have been sent from the global north to the global south, passed their ‘use by’ date and, instead of being sent southwards to prevent the spread and mutation of Covid, had to be destroyed. I hate waste. So does the British public. Lives could have been saved by sending Africa the unused vaccines before they expired.

Quite simply we are having to recreate Nightingale wards in the United Kingdom to cope with possible emergency admissions here because we have failed to halt the emergence and spread of the Omicron virus abroad. And it seems we have also inexcusably sat on over-ordered PPE surpluses, letting medical equipment like masks and

gowns also pass their ‘use by’ date instead of being sent to countries in desperate need of them – because of a predetermined cap imposed on the overseas aid budget.

And as long as we waste vaccines and can’t offer unused equipment to people in Africa and elsewhere, global medical experts are predicting 200 million further Covid cases for 2022. Almost 5.5 million lives have now been lost to Covid.

Unless we get vaccines and testing equipment to the global unvaccinated, they anticipate it could lay waste to five million more lives in the months to come.

The longer we delay vaccinating the unprotected, the more likely the virus will keep mutating. But with 1.4 billion vaccines being produced every month, and nearly 20 billion by June (in total), we have the capacity to vaccinate everyone in the world. To control the disease also requires testing – and again, we have failed to honour our promises. Only one in 250 of the Covid tests administered worldwide have been administered in low-income countries. So, in 2022, to end the pandemic, we must stop the underfunding of vaccinations, testing and medical equipment needed in low-income countries.

President Biden will recall his Vaccine Summit in the first weeks of 2022. On the agenda should be a ‘fair shares’ agreement, with America and Europe guaranteeing more than half the $23.4bn cost of getting vaccines, testing and other medical equipment to the poorest countries. Big international financial institutions, like the World Bank and the IMF, should be asked to come up with the cash needed to build in-country capacity to administer the vaccines, staff the makeshift vaccination clinics and help prevent future pandemics. And if we need more cash to save lives, let’s try some innovative ideas. France has raised $1.25bn for global health since 2006 through its tax on airlines. $100bn of the $650bn in special drawing rights (new international money created by the IMF) could be quickly deployed to provide resources for poorer countries to buy the necessary medical supplies. The richer countries could leverage $2bn of loan guarantees into $10bn of additional resources for poorer countries. During the financial crisis of 2009, we underpinned the world economy with $1.1tn of support. The medical price tag for 2022 is $60bn, only a fraction of what was spent in 2009 and certainly a fragment of what it’s costing us now in lost output and lost trade. It’s the best investment the world can make, and the best ever insurance policy to stop the agony of lost lives.

This article is extracted with permission from an article written for the Daily Mirror, available at www.mirror.co.uk/ news/politics/five-million-more-lives-could-25843975

“Vaccination and testing have to happen everywhere if the virus is to be contained.”

Axel Heitmueller, Senior Associate Fellow, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change

Axel Heitmueller, Senior Associate Fellow, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change

I look back at the early days of the pandemic with a mix of cold sweat and wonderment. Those early months in spring 2020 were filled with great anxieties about the ability of the NHS to cope with the rapidly rising numbers of hospitalisations. There was no cure, there was no vaccination, and there was a great sense of uncertainty. The spectre of people dying in corridors in Italian hospitals loomed large. No one knew when cases would peak.

At the same time, up and down the country, something extraordinary was happening. NHS organisations that had been in fierce competition for years found ways to collaborate. Innovation was adopted in days not years. Stifling bureaucracy was suspended. For the first time in my decade in the NHS, action preceded planning. There was no playbook, no business case template. A burning hot platform instilled purpose that couldn’t be served by postponing action until tomorrow.

Maybe naively many of us felt that this might be the beginning of a new chapter in the provision of health and care, allowing us to hang on to the momentum, the collaboration, and focus on transformation. A strong collective purpose, an existential threat leading to rapid change as opposed to plans for change. That sentiment didn’t last very long. Midway through April the Covid case numbers finally started to turn and with them the elastic band of change snapped back fast.

On 29 April 2020 the NHS London regional leadership issued a letter asking all London designated Integrated Care Systems (ICS) to produce a transformation plan within ten days. This was to address 12 specific expectations including a high-level financial summary. To all intents and purposes, an impossible ask not least because everyone locally was exhausted, many were recovering from Covid themselves.

The muscle memory of NHSE [NHS England] kicked in with a vengeance.

By 10 May, we did submit a plan; the NHS always does. I’ve not counted the opportunity and real costs of those ten days and nights, but it will have been considerable.

It will come as no surprise to those who have gone through the motions many times before in the NHS that this plan was never

delivered. It was never written to be deliverable. In the months that followed, it was simply superseded by new plans and instructions.

Schrödinger’s NHS cat is the illusion of top-down change –always present, never to be seen. If half the plans for change published in the past decade had actually been implemented, the NHS would be a beacon of transformation. They weren’t and as a consequence it ranks towards the bottom of international league tables for health outcomes. This is increasingly impossible to sustain. Unprecedented sums of money are flowing towards health and with that come public and political expectations. At the same time, the first major health legislation in a decade is going through Parliament and Covid has demonstrated that accelerated change is possible.

Forthcoming White Papers, which will set out the detailed policy underpinning the legislative reforms in the coming weeks and months, are an opportunity to think harder about a change model that delivers on these expectations. There is much to learn from recent decades about the role of different policy levers. The evidence is increasingly strong: healthcare as a complex ecosystem can’t be meaningfully controlled top-down. A command-and-control style may provide the illusion of being in charge, but it most certainly does not foster innovation and

“Unprecedented sums of money are flowing towards health and with that come public and political expectations.”

change of the nature that is required. Market forces have also had limited impact. Reaching for structural change on its own also avoids the real work; form should follow function. Instead, implementable change requires local energy, aligned policy levers, collaboration, and a level of autonomy.

Less top-down and more local freedoms will run against the deep instincts of the Treasury which rightly seeks accountability for public spending. A central question for the reform agenda is therefore how to ensure accountability while moving towards greater local autonomy.

I see five potential areas worth considering for a progressive public management playbook to achieve meaningful change:

1 Empower and trust citizens to hold local systems to account: local autonomy may come with local variation in care. Therefore, a necessary feature of a more devolved system should be a transfer of trust and power to citizens to hold their local healthcare system to account. Currently it is very hard for patients to understand what good care should look like. Addressing this will not only support direct accountability between a patient and caregiver but also accelerate the adoption of best practice innovation.

2 Rely on local democracy: the governance of Integrated Care Systems offers an opportunity to include local government. This opens the door to a progressive version

of Local Area Agreements between different public sector organisations and citizens through their elected representatives. Regions differ in their health needs. Trading off resources and needs within local preferences and democratic structures will provide a different quality of legitimacy compared to traditional NHS plans.

3 Reward learning as part of accountability: making integrated care happen will require systems leadership. Compared to organisational leadership, this is a fundamentally different style. Part of systems leadership is acknowledging and becoming comfortable with not having all the answers. Systematic and continuous learning will be essential in driving change and should be explicitly rewarded and nurtured.

4 Focus on fewer, essential measures: with more accountability concentrated locally, central control and regulation can retreat to functions that truly benefit from a national perspective and scale. This includes setting a small set of non-negotiable baseline safety and operational measures. Healthcare is evidence based and closing the gap between what we know and what we do is essential. Healthcare is also a high-risk business, and the NHS does not always get it right.

5 Move towards dynamic, outcome focused measures: whether for national or local purposes, we should reduce the burden of data collection. Real World Evidence from electronic patient records and app-enabled, patient-led data collection are increasingly routinely available. This offers opportunities to compare a broader and increasingly outcome-based set of measures across ICSs and providers in more timely and agile ways. It may also safeguard against the gaming of data collected specifically for performance management.

Sharing power with local organisations, citizens, and elected politicians requires a significant cultural and behavioural shift in NHS England and the centre of government. The pandemic offered us a glimpse of a much more innovative and dynamic health and care system, and the technological leap it created makes radical reform a realistic prospect. Seizing that opportunity will require political courage. But then, insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result.

“Healthcare as a complex ecosystem can’t be meaningfully controlled topdown.”

We are surrounded by feedback. From hotels to holidays, meals to music, we now provide or seek out feedback about almost every kind of product or service you can imagine. But what about healthcare? In most countries, including the UK, it isn’t common for clinics and hospitals to ask for or display patient feedback, and even if it were, what would be the purpose? Healthcare, especially in emergencies, is not usually something people look forward to choosing and using.

At Care Opinion, a non-profit social enterprise, we’ve been sharing online patient feedback for over 15 years now. We’ve learned that feedback, and particularly online feedback, can be complex, multi-layered and highly relational, with a range of powerful and surprising impacts for both patients and healthcare staff.

At careopinion.org.uk many thousands of people have shared their specific experiences of health and care: childbirth, emergencies, operations, mental health issues, addictions, end of life. These stories are by turns heart-warming or angry, grateful or desperate, routine or life-changing. But all are about things that mattered to the person experiencing care, and sometimes about services that could have been better. We link these stories to the local services which provided the care, and aim to alert staff (by email) to their feedback. And then staff respond: around 75% of stories receive a response on average, rising to over 97% in Scotland and Northern Ireland. That’s because in those jurisdictions Care Opinion is now the online platform of choice for feedback across the healthcare system, used by all hospital, ambulance, mental health and many other services. In addition, feedback flows upwards to regulators, policymakers and politicians, and outwards to medical and nursing schools, analysts and researchers.