2024 downtown Visioning and design

was produced by

was produced by

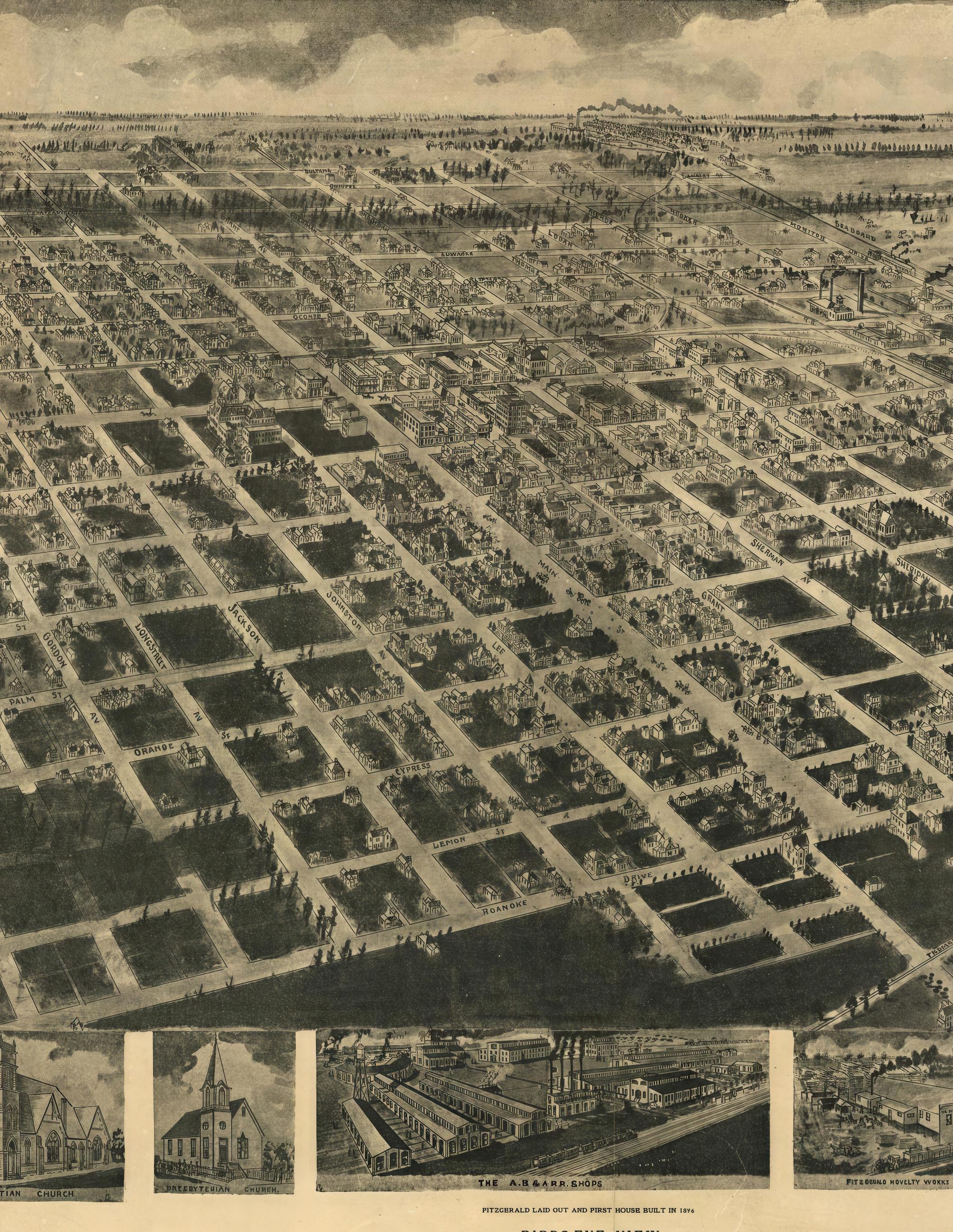

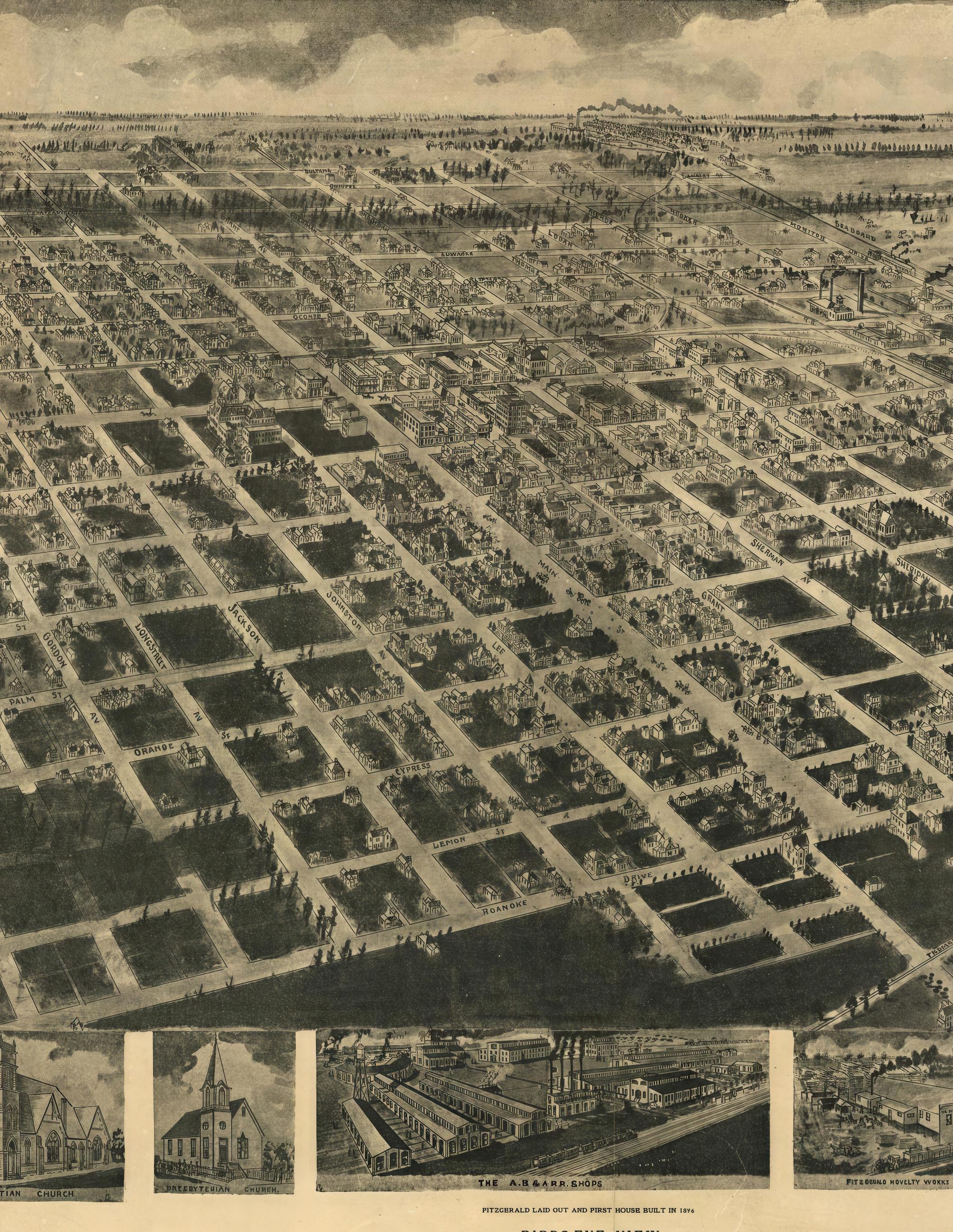

1895: Philander H. Fitzgerald proposed creating a city in South Georgia as a colony for Civil War veterans.

1896: Fitzgerald was incorporated as a city. Early 1900s: Local landmarks including the AB&A depot, City Hall, First National Bank, and the Garbutt-Donovan Building constructed.

1902: Fitzgerald City Hall constructed at Central Avenue and Sherman Street.

1906: Fitzgerald becomes the seat of the newly formed Ben Hill County.

1945: Fitzgerald Municipal Airport opened to the public.

1960: Blue & Gray Museum established in the old Lee-Grant Hotel.

1963: The Fitzgerald and Ben Hill County Development Authority was formed.

1966: Ben Hill-Irwin Area VocationalTechnical School, later Wiregrass Georgia Technical College, opened in Fitzgerald.

1986: Community leaders began organizing to save and restore downtown’s Grand Theater.

Whitney Justice, Director of Community Development

Incorporated in 1896 as a haven for Union veterans of the American Civil War, Fitzgerald, Georgia is home to over 9,000 residents and serves as the county seat of Ben Hill County. Located in South Central Georgia, Fitzgerald and Ben Hill County are known for innovative industrial initiatives, a welcoming atmosphere, and exceptional hospitality. Only 25 miles off Interstate 75, Fitzgerald and Ben Hill County boast a stateof-the-art airport with a 5,000-foot runway, a trainable and loyal workforce, and many industrial properties all within a 2.5-hour drive of Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport and the Ports of Savannah and Brunswick. The community is also home to Dorminy Medical Center, one of rural Georgia’s top-rated hospitals.

Fitzgerald’s mission is to listen to and communicate with citizens while providing services and programs in a safe and efficient manner. The local government coordinates with other agencies and operates under financially sound practices to provide a better quality of life for all. The city defines their vision as working to improve the lives of citizens by fostering educational and career opportunities for future generations, thereby creating a safe and thriving city. Fitzgerald is a warm and charming community where citizens feel they belong.

1996: Fitzgerald celebrated the city’s centennial.

2000: Fitzgerald celebrates the city’s first Wild Chicken Festival.

2001: The city began improving 26 blocks of downtown streetscaping.

2006: Fitzgerald’s restored Carnegie Library reopened as a community arts venue and meeting space.

2014: Fitzgerald partners with the UGA Institute of Government to develop the 2014 Downtown Renaissance Fellowship plan.

2022: The Fitzgerald High School College and Career Academy opened to the community.

2023: Ben Hill County becomes a PROPEL community.

2024: PROPEL Rural Scholars visit and interview local small business owners downtown.

2024: Fitzgerald partners with the Institute of Government on the 2024 Fitzgerald Downtown Vision and Design plan.

Jason Dunn, Executive Director Emily Harper, Community Partner

Fitzgerald and Ben Hill County have always been trendsetters in economic development. The community is widely known for its efforts in recruiting new industry and especially for nurturing and providing opportunities for existing industries to grow. With stated goals of being the most aggressive, efficient, and credible development authority in South Georgia, the authority leverages our local, regional, and state relationships to create even more opportunity for growth. In 2015, the community launched an initiative to revitalize the local economy through industrial and manufacturing efforts. Since that time, the Fitzgerald and Ben Hill County Development Authority has worked with existing and new employers to capture over $250 million in capital investment, seen the construction of 500,000 square feet of new industrial properties, filled 600,000 square feet in formerly vacant industrial properties, and sold nearly 200 acres for industrial expansion and development. These efforts have created hundreds of new career opportunities, launched new career training initiatives, and reestablished the community as one of the region’s top job creators.

Cindy Eidson, Director of Economic and Community Development

Chris Higdon, Community Development Manager

Created in 1933, the Georgia Municipal Association (GMA) is the only state organization that represents municipal governments in Georgia. Based in Atlanta, GMA is a voluntary, nonprofit organization that provides legislative advocacy, educational, employee benefit, and technical consulting services to its members. GMA’s mission is to anticipate and influence the forces shaping Georgia’s cities and to provide leadership, tools, and services that assist municipal governments in becoming more innovative, effective, and responsive.

Pam Sessions, President

The Georgia Cities Foundation was originally established in 1999 by the Georgia Municipal Association as a 501(c)(3) organization. In December 2010, the foundation was designated as a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) by the US Department of the Treasury’s CDFI Fund. The foundation’s mission is to assist cities in their community and economic development efforts to revitalize and enhance underserved downtown areas by serving as a partner and facilitator in funding capital projects and by providing training and technical assistance.

T. Clark Stancil, Principal Investigator

The University of Georgia Carl Vinson Institute of Government is committed to promoting excellence in government through technical assistance, training programs, applied research, evaluation, data, and technology solutions. As a Public Service and Outreach unit of the University of Georgia, the institute shares in the university’s overarching public service mission of connecting communities with professional knowledge, expertise, and resources to help improve quality of life. The Institute of Government informs, inspires, and innovates so that governments, large and small, can be more efficient and responsive to citizens, address current and emerging challenges, and serve the public with excellence.

The University of Georgia Foundation enriches the quality of education at the university by supporting scholarships, endowed chairs and professorships and other programs that rely on private funds. With more than $1.9 billion in assets, a large portion of which is endowed, the foundation provides an average of more than $90 million annually to UGA to advance its mission of teaching, research and public service. The foundation was established in 1937. As a steward of donor funds, the foundation has a strong record of fiscal and financial management. Its investment portfolio has consistently outperformed key benchmarks. Growth in the foundation’s assets has allowed for greater financial support of the university’s mission.

City of Fitzgerald

Whitney Justice, Director of Community Development

Fitzgerald and Ben Hill County Development Authority

Jason Dunn, Executive Director

Emily Harper, Community Partner

The Georgia Municipal Association

Cindy Eidson, Director of Economic and Community Development

Chris Higdon, Community Development Manager

The Georgia Cities Foundation

Pam Sessions, President

The University of Georgia Carl Vinson Institute of Government

T. Clark Stancil, Principal Investigator

Danny Bivins, Senior Public Service Associate

Kaitlin Messich, Public Service Associate

Eleonora Machado, Creative Designer

Greg Wilson, Associate Director; Workforce & Economic Development

Hannah Hussain, Editor

Sara Ingram, Multimedia Specialist

Garrison Taylor, Downtown Renaissance Fellow

The University of Georgia Foundation

The Georgia Downtown Renaissance Partnership was founded in 2013 as a community-driven collaborative planning and design partnership. The partnership brings together public institutions, nongovernmental organizations, and private foundations to assist local governments with downtown revitalization and other planning challenges. Partners including the University of Georgia Carl Vinson Institute of Government, the Georgia Municipal Association, and the Georgia Cities Foundation bring diverse resources to the table to support community-driven planning. Since 2013, the Georgia Downtown Renaissance Partnership has brought a collaborative planning approach to over 60 cities across Georgia and neighboring states. Through program elements like the Renaissance Strategic Vision and Planning (RSVP) process, the Georgia Downtown Renaissance Fellowship, and collaborative studio courses with the UGA College of Environment and Design, the Georgia Downtown Renaissance Partnership helps provide the tools for communities to realize their vision and maximize their potential.

In 2014, Fitzgerald was selected as one of three communities to take part in the Georgia Downtown Renaissance Fellowship program. This plan was developed by student fellow T. Clark Stancil in partnership with Fitzgerald’s former Community Development Director Cam Jordan. Exactly 10 years after this initial planning effort, city leaders once again partnered with Mr. Stancil, now a Creative Design Specialist at the Institute of Government, to create professional-quality design concepts intended to support the city’s small business owners and enhance downtown development. Reuniting city leaders with Institute of Government design faculty and staff, this unique project aims to chart the course for the next decade of development in downtown Fitzgerald. As part of this plan, the UGA Institute of Government design studio worked directly with local officials, residents, and the Fitzgerald-Ben Hill County Development Authority to address specific design opportunities in Fitzgerald.

This project emerged from the city’s participation in the Planning Rural Opportunities for Prosperity and Economic Leadership (PROPEL) program, which provides rural communities with resources to create systems necessary to support their own economic and workforce development strategies. Over the past year the PROPEL program has brought new resources, including a team of PROPEL Rural Scholars, to support economic development in the community. The two-year program is operated by the Carl Vinson Institute of Government and funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

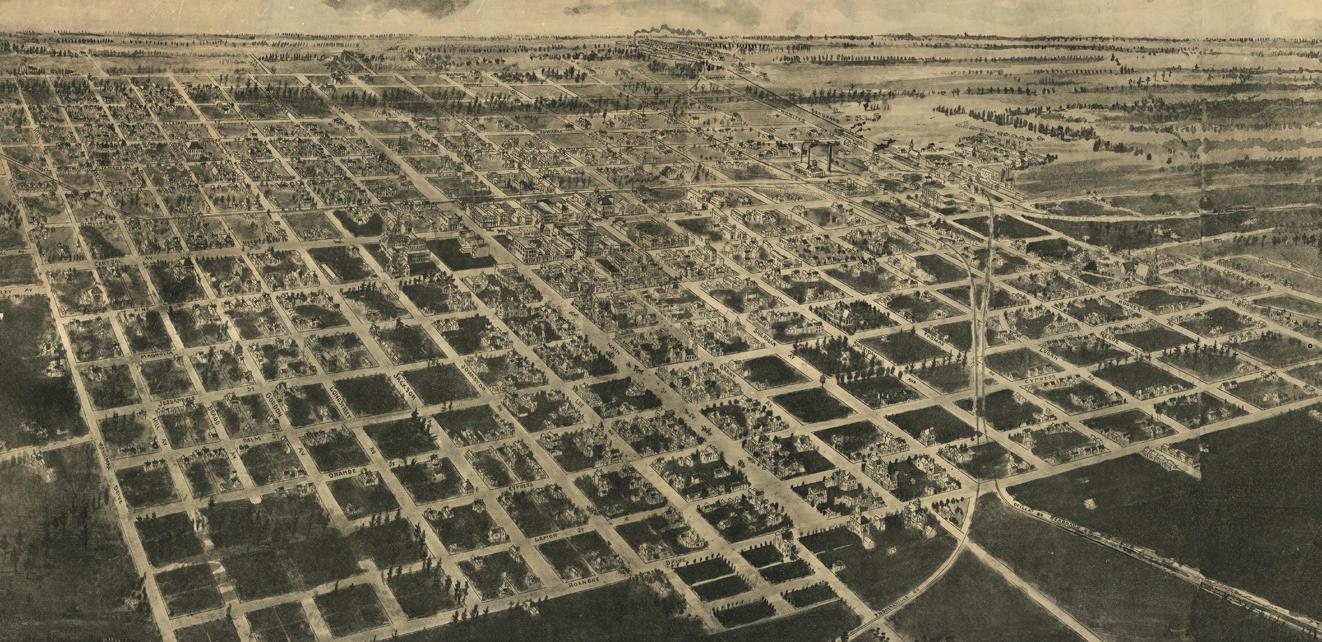

Located in Ben Hill County in the heart of South Georgia, Fitzgerald is known for the city’s unique origin story and exceptional town planning legacy. Originally planned as a welcoming Southern settlement for Union veterans, Fitzgerald prides itself on the city’s role in healing national divisions in the aftermath of the Civil War.

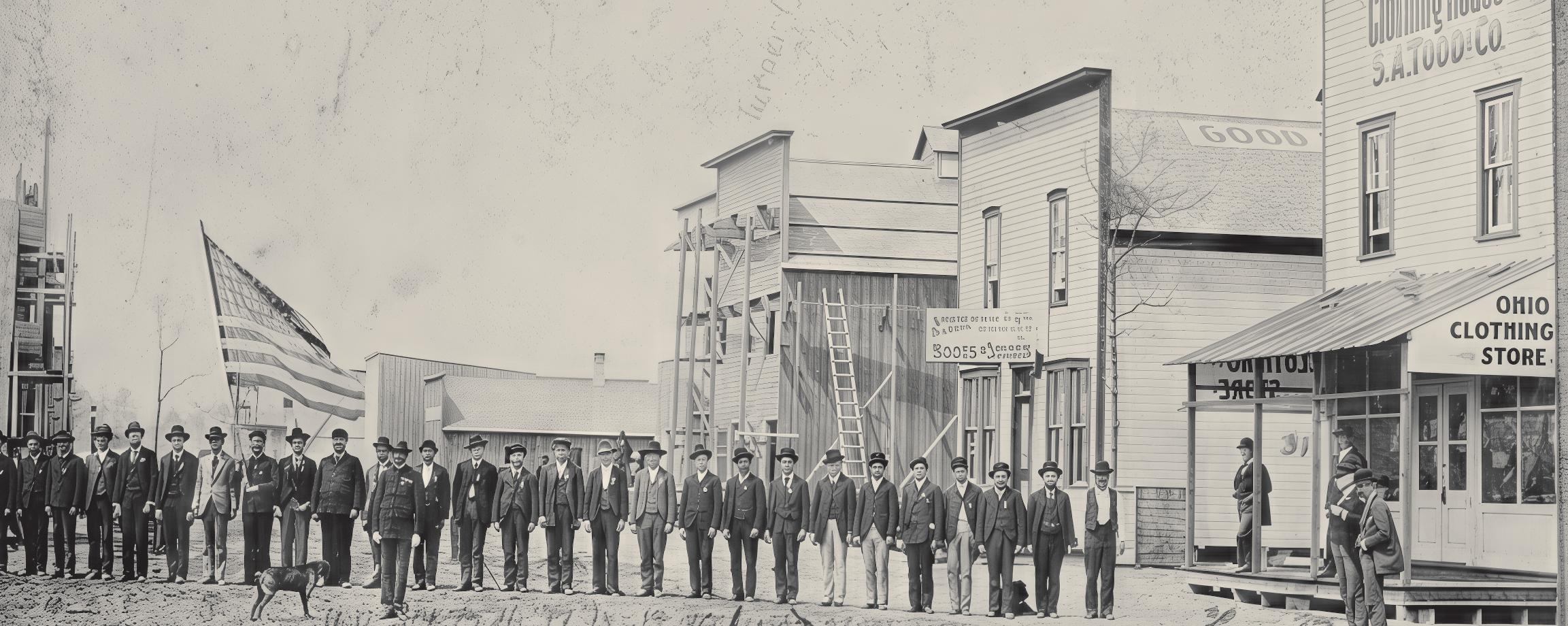

Fitzgerald’s origins can be traced back to 1895 when Indianapolis newspaper editor Philander H. Fitzgerald responded to the plight of Midwestern veterans facing drought, crop failures, and economic turmoil from the Panic of 1893. Fitzgerald suggested a bold idea: a colony city for displaced veterans in the warm climate and fertile soil of South Georgia. In 1895, P.H. Fitzgerald’s American Tribune Soldier’s Colony Company began advertising shares of fifty thousand acres in Georgia’s

wiregrass country throughout the Midwest and Northeast. At a settlement known as Swan, a thousand of the company’s acres were divided into 256 gridironed city blocks, forming the heart of downtown Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald soon began drawing settlers from across the country, creating an overnight boomtown and melting pot of American culture. Fitzgerald’s early heritage lives on, from the network of gridded brick streets and alleys to the city’s unique architecture and dedicated lots for public schools and parks. These early investments fostered a community spirit that continues to thrive.

Fitzgerald’s rich architectural heritage continues to add a palpable charm to this historic community. Unfortunately, the qualities that make Fitzgerald special are also under threat. In a pattern seen in many other cities, from the 1950s onward many of Fitzgerald’s once vibrant downtown businesses began relocating to major automotive corridors outside of Fitzgerald’s original thousand-acre grid. The relocation of downtown businesses to sprawling corridors has slowly siphoned activity from the booming downtown that long-time residents fondly remember. Too often, property owners have allowed vacated downtown buildings to fall into neglect. As a result, far too many of the city’s iconic buildings have been lost to demolition. Buildings allowed to fall into neglect continue to endanger the architectural integrity and economic vitality of the city’s historic

core, making preservation efforts even more critical in maintaining Fitzgerald’s unique character and sense of place. Recognizing the importance of preserving the city’s historical assets, the local government has often played a crucial role in maintaining and restoring key downtown buildings. Iconic structures like the Grand Theater and the historic Carnegie Library stand as testaments to the city’s longstanding commitment to heritage preservation. Fitzgerald’s 2014 Downtown Renaissance Fellowship took place as the city and region were still recovering from the Great Recession. The plans and design concepts included in the city’s 2014 fellowship plan primarily focused on revitalizing city-owned properties and public spaces, including the courtyard behind the city’s 1915 Carnegie Library, now the home of the Fitzgerald-Ben Hill Arts Council. In a challenging time for the local economy, community leaders recognized that public investment is often required to stimulate private investment. In subsequent years the city has built on concepts envisioned in the 2014 fellowship plan to return economic vitality downtown.

Fitzgerald has made great strides since the completion of the city’s 2014 Georgia Downtown Renaissance Fellowship. Today visitors traveling along Central Avenue are greeted by an assortment of inviting parks in the city’s historic medians, with eventual plans to complete a full trail network linking Main Street and Central Avenue’s 41 medians. New street trees, inviting sidewalks, and lush plantings send the signal that the community is committed to the continued revival of the city’s historic core. Throughout downtown, the careful efforts of local developers including L.E. Harper Commercial have brought new life to some of Fitzgerald’s marquee historic properties. Numerous façade renovations and new small businesses speak to the entrepreneurial spirt alive and well in Fitzgerald.

In the past decade the city has thoroughly embraced public art and placemaking, a peoplecentered, place-based approach to the planning, design, and use of public spaces. In 2021, the city was selected one of five communities to take part in the Georgia Economic Placemaking Collaborative, a twoyear place-based economic development program housed at the Georgia Municipal Association. With support from groups like the Fitzgerald-Ben Hill Arts Council and the City of Fitzgerald’s Department of Tourism, Arts &

Culture, new murals and vibrant artwork greet guests throughout downtown. Often these works of art reference the city’s unique history and the wild chickens that help make Fitzgerald the special place it is. Even many of the fire hydrants and dumpsters have been transformed into canvasses for local artists. Downtown is altogether a more colorful and economically vibrant destination than it was 10 years ago.

Beyond the city’s historic downtown, Fitzgerald has long boasted a strong industrial and manufacturing base. The city and dedicated local partners including the Fitzgerald and Ben Hill County Development Authority have worked to expand the local manufacturing base, nourishing a diverse roster of growing companies like Mana Nutrition, Polar Beverages, Golden Boy Foods, Protein Plus, Covered Wagon Trailers, Modern Dispersions, and more. Fitzgerald has also been successful recruiting five new major industrial employers from 2016-2020 alone. With local industries expanding, community leaders recognized the need to enhance career training for local youth graduating high school and moving into the workforce. Since 2016, the city has become a leader in workforce development, creating a unique pipeline that pairs the local school system, Wiregrass Georgia Technical College, and local industries to meet the labor force demands of Fitzgerald’s 21st century industrial base.

Fitzgerald’s story is one of resilience, innovation, and a deep commitment to community. From the city’s founding days as a haven for Civil War veterans to the 21st century manufacturing hub of today, Fitzgerald has continually embraced the city’s rich heritage while adapting to contemporary challenges and opportunities. The city’s dedicated leadership and commitment to preservation and economic development have set a strong foundation for ongoing growth and revitalization.

In the summer of 2024, the City of Fitzgerald and the Fitzgerald Ben Hill County Development Authority sought design assistance from UGA’s Carl Vinson Institute of Government. Local leaders worked with the Institute of Government to outline a vision to guide the future development in downtown. This project was made available to Fitzgerald through a partnership between the city, the development authority, the Georgia Municipal Association, the Georgia Cities Foundation, and the UGA Carl Vinson Institute of Government. This project was also made possible by the Institute of Government’s Georgia Workforce and Economic Resilience Center, with additional financial support from the UGA Foundation to support PROPEL

communities. This project is a continuation of the Planning Rural Opportunities for Prosperity and Economic Leadership (PROPEL) program, funded by USDA Rural Development. The generous support of these funding partners allowed this planning effort to take place without any cost to Fitzgerald.

This document is intended visualize options for the future growth of downtown to assist local leaders and residents. The designs that follow respond to unique challenges and opportunities found in downtown Fitzgerald, including streetscape recommendations and façade designs for small businesses throughout downtown. Developed with the assistance and oversight of local property owners and city leaders, the proposed designs show concepts that create more vibrant, active storefronts and more attractive, inviting streets for residents and visitors. Together, these designs are intended to spur reinvestment in downtown Fitzgerald, support local small business owners, and grow the local economy.

Streetscape Concepts

• Pine Street Streetscape

• Create up to four renderings showing street tree plantings.

• Develop a list of street tree recommendations for appropriate street trees along Pine Street.

• Public Parking EV Station

• Create one to two renderings showing the appropriate site of a downtown electric vehicle charging station

Façade Designs for Small Business Owners

• Develop up to four design concepts for interested property owners.

• Develop façade design concepts for potential properties along Pine Street, Central Avenue, and Main Street.

• Develop back-of-house courtyard and parking design concepts for properties at 105 East Central Avenue and 109 Main Street.

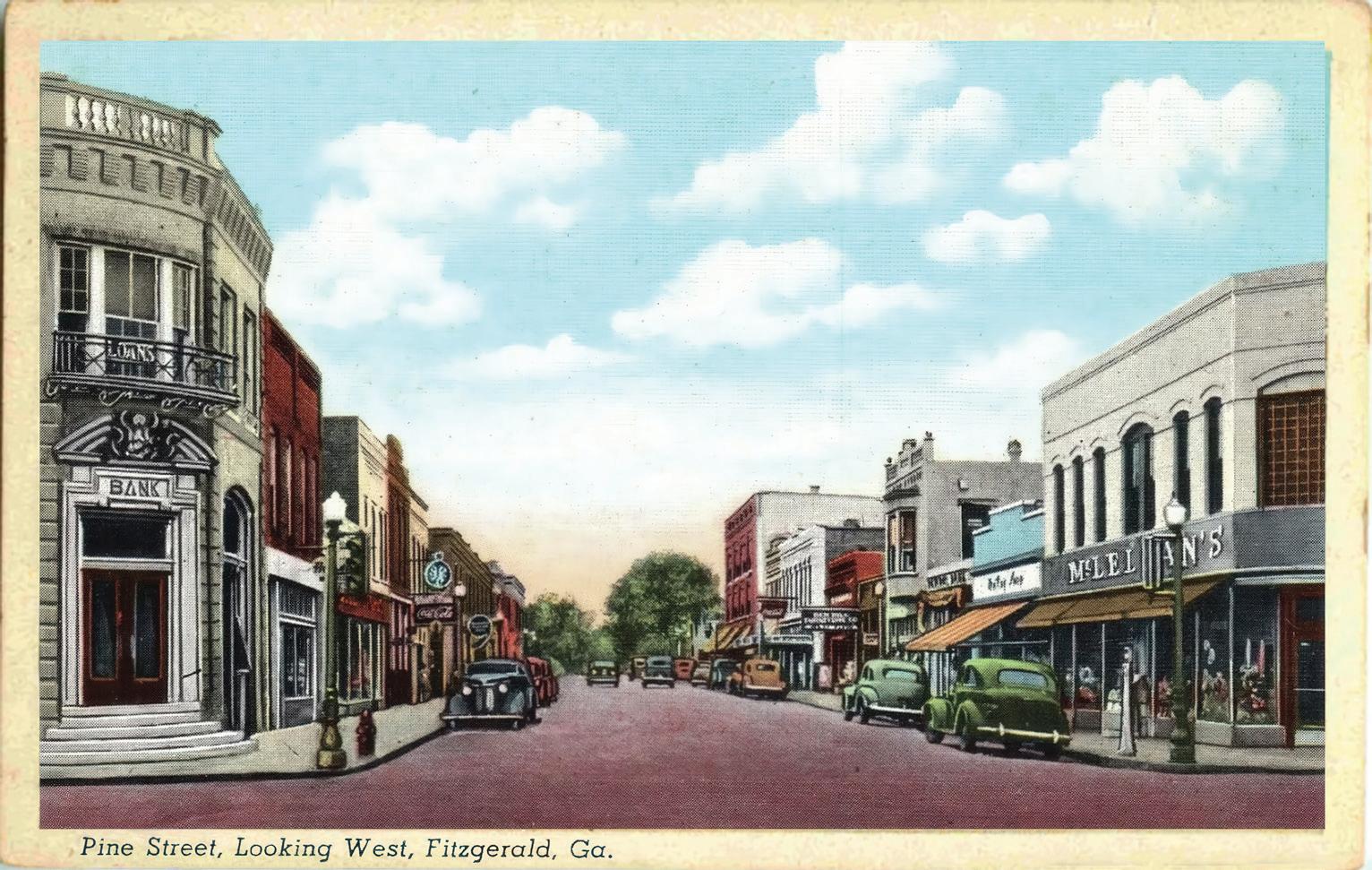

Paved in red brick from the early 1900s, Pine Street contains one of Fitzgerald’s best collections of historic commercial buildings and a growing variety of small businesses. Visitors to this corridor are treated to a glimpse of this city’s rich heritage. Grand historic buildings like the Former First National Bank (1903), Former Third National Bank (1907), and the fivestory Garbutt-Donovan Building (1908) lend a timeless dignity to the streetscape. Elements like the distinctive hexagonal pavers and twinkling string lights all send the signal that this is a special place worthy

A streetscaping program in the 1990s and early 2000s returned blue and gray hexagonal pavers, a historically significant material with unique local ties, to the sidewalks along Pine Street. This program also constructed tree wells and maple street trees along the sidewalk. Unfortunately, the maples selected proved to be a problematic tree selection that quickly outgrew the tight parameters of the existing tree wells. The trees were removed in 2019 and have not been replaced. From Main Street to Thomas Street, today Pine Street includes 37 vacant tree wells. Local leaders reached out to professional planners and landscape designers at the Institute of Government to provide options for appropriate street tree selections for Pine Street. After consulting with local business owners and city leaders and staff, it became clear that many locals had mixed feelings and lots of opinions about returning street trees to Pine Street.

From reducing energy bills to enhancing walkability, planting trees ranks as the single highest impact, lowest cost improvements that can be made to a downtown area. Particularly in sunny South Georgia, withering summer heat make street trees a necessity

for encouraging year-round pedestrian activity and commerce. The Pine Street streetscape was thoughtfully designed to include roughly a dozen street trees per block. This expensive infrastructure has already been purchased and installed. For Pine Street to perform to its highest potential, thoughtfully considered, low maintenance street trees should return to these important downtown blocks. Street trees are a proven way to encourage walking, slow traffic, and beautify city streets. After three years of watering, a hardy street tree is generally established enough require little or no maintenance beyond occasional pruning. Compare this level of maintenance to that of annual flower beds or perennials, which require near daily watering, weeding, seasonal replacement, and don’t provide any shade. Shaded pavement can be up to 45 degrees cooler than surrounding unshaded surfaces, an important consideration in Southern climates. Trees also release water vapor and oxygen, which helps to cool the air around them. This process, called evapotranspiration, can reduce air temperatures by up to nine degrees. For additional benefits of street trees, please see the “10 Benefits of Street Trees” section on the following page.

While installing new trees is relatively inexpensive compared to other municipal improvements, a number of opportunities exist to offset the cost associated with tree planting. To encourage tree planting in communities across the state, the Georgia Tree Council and Georgia Forestry Commission offer an annual funding opportunity available to cities investing in street trees. The Georgia ReLeaf Grant Program provides up to $15,000 for municipal tree planting projects. Fitzgerald could consider applying to this or other grant opportunities to help offset the cost of tree planting. Grant funding could also help the city invest in more costly but impactful large-caliper mature trees.

A number of constraints limit the size and type of tree selection that would be appropriate for Pine Street. Pine Street’s sidewalks are narrower than others downtown, the existing tree wells are very limited in size, tree wells are placed in close proximity to building faces, and Fitzgerald’s distinctive sidewalk pavers are constructed in a way that make aggressive tree roots problematic. When future sidewalk maintenance requires relaying pavers, city leaders should look to installing Silva Cells or a similar suspended pavement system. These fairly low-cost cells create a stable base for sidewalk paving while restricting the growth of tree roots to a contained cell beneath surrounding paving. These systems are engineered to allow street tree roots to grow freely without damaging neighboring sidewalks.

After consulting with city leaders and staff, black gum trees (Nyssa sylvatica) were determined to be the most appropriate selection for the majority of the tree wells along Pine Street. These sturdy, drought tolerant native trees grow throughout the Eastern Seaboard deep into Florida and west to Texas. Their slow rate of growth and narrow habit minimize potential conflicts with surrounding buildings and paving. In the fall, these trees also produce a brilliant display of red to deep purple foliage. While surrounding building faces and other constraints limit what can be planted in many of Pine Street’s tree wells, eight locations along Pine Street would be appropriate for a larger canopy street tree. A Chinese elm (Ulmus parvifolia) or similar tree would likely be the most appropriate selection in these areas. These trees have a spreading habit that creates a welcoming canopy of shade. Chinese elms are extremely drought tolerant, low maintenance, and thrive in downtown areas from Boston to Orlando and beyond. The following design concepts illustrate the impact these trees could make to the Pine Street Streetscape.

1. Temperature Reduction

2. Improved Air Quality

3. Increased Economic Activity

4. Enhanced Property Values

5. Stormwater Management

6. Traffic Calming and Reduced Vehicular Speeds

7. Lower Utility Bills

8. Physical Activity

9. Wellbeing

10. Sense of Community

1. Temperature Reduction

o Street trees can lower surface temperatures by up to 20-45°F (11-25°C) by providing shade and evapotranspiration. Ambient air temperatures can be reduced by 2-9°F (1-5°C) in areas with ample tree cover.

2. Improved Air Quality

o A single mature tree can absorb up to 48 pounds of carbon dioxide per year. Trees also filter airborne pollutants, removing up to 60% of street-level particulates and absorbing other harmful gases like nitrogen dioxide and sulfur dioxide.

3. Increased Economic Activity

o Shoppers in tree-lined retail areas are willing to pay 12% more for goods and services, and they tend to shop more frequently and for longer periods.

4. Enhanced Property Values

o Properties with trees on or near them can see an increase in value by up to 10-15%. In commercial districts, well-landscaped areas with trees can increase rental rates and occupancy.

5. Stormwater Management

o Excess stormwater runoff often places burdens on existing infrastructure in downtown areas. Trees reduce stormwater runoff as their roots capture rainfall. A mature tree can absorb more than 1,500 gallons of rainwater annually, decreasing the burden on combined sewers and drainage systems.

6. Traffic Calming and Reduced Vehicular Speeds

o The presence of street trees can have a traffic calming effect, encouraging drivers to reduce dangerous speeds. Slower traffic speeds mean both safer streets and more eyes on downtown commercial storefronts. Studies show that treelined streets can lead to a reduction in driving speeds by 3-5 mph. Trees can help provide a vertical element and a sense of enclosure by visually narrowing the road, prompting drivers to slow down. Reduced speeds can lead to fewer and less severe accidents, improving overall pedestrian safety.

7. Lower Utility Bills

o South Georgia business owners rely on air conditioning to make their businesses viable in the hot spring and summer months. Strategically planted street trees can significantly reduce the cooling costs for nearby buildings. Trees provide shade, which can lower surface and ambient

temperatures around buildings. The shade provided by street trees can reduce the demand for air conditioning, leading to energy savings of up to 10-30%. In less dense residential areas, shaded homes can experience a reduction in cooling costs by 15-50%, depending on the density and placement of trees.

8. Physical Activity

o People are 25% more likely to walk in neighborhoods with tree-lined streets, contributing to better public health outcomes.

9. Wellbeing

o Access to green spaces, including tree-lined streets, has been linked to a reduction in stress, anxiety, and depression. Even a view of trees through a window can lower stress markers, such as cortisol levels, by up to 12%.

10. Sense of Community

o Green spaces and tree-lined areas promote social interaction. In neighborhoods with green spaces, there is a reported increase of 83% in socializing among residents, leading to stronger community ties.

1. Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “Reducing Urban Heat Islands: Compendium of Strategies.”

2. Source: Nowak, D. J., et al. (2006). “Air pollution removal by urban trees and shrubs in the United States.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 4(3-4), 115-123.

3. Source: Wolf, K. L. (2005). “Business district streetscapes, trees, and consumer response.” Journal of Forestry, 103(8), 396-400.

4. Source: Wolf, K. L. (2004). “Economics and Public Value of Urban Forests.” Urban Agriculture Magazine, 13, 31-33.

5. Source: Xiao, Q., et al. (1998). “Rainfall interception by Sacramento’s urban forest.” Journal of Arboriculture, 24(4), 235-244.

6. Source: Dumbaugh, E., & Gattis, J. L. (2005). “Safe Streets, Livable Streets.” Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(3), 283-300

7. Source: McPherson, E. G., & Rowntree, R. A. (1993). “Energy conservation potential of urban tree planting.” Journal of Arboriculture, 19(6), 321-331.

8. Source: Sallis, J. F., et al. (2012). “Role of built environments in physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular disease.” Circulation, 125(5), 729-737.

9. Source: Ulrich, R. S. (1984). “View through a window may influence recovery from surgery.” Science, 224(4647), 420-421.

10. Source: Sullivan, W. C., & Kuo, F. E. (1996). “Do trees strengthen urban communities, reduce domestic violence?” USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, 8(3).

These four options show potential street trees appropriate for the climate and conditions found along Pine Street in downtown Fitzgerald. The narrow width of the existing sidewalk, limited size of the tree wells, and close proximity of building façades limit the type of tree that can be selected for Pine Street. Options pictured include Natchez crape myrtle, bald cypress, Chinese pastiche, and black gum trees.

The 100 block of East Pine Street running from Main Street to Grant Street includes some fine examples of Fitzgerald’s spectacular architectural heritage. The former Third National Bank building has brought a dignified presence to this corner since 1906. Grand Plaza Park across the street was once home to the Empire Hotel. Additional shade trees would be a welcome addition to this popular downtown park.

This stretch of Pine Street includes 13 vacant tree wells, two of which border Grand Plaza Park. This design shows slow growing, low maintenance black gum trees in 11 of the tree wells. The two tree wells bordering Grand Plaza Park would be appropriate for a tree with a more generous, spreading habit. The two Chinese elms pictured could quickly provide much needed shade at the neighboring park.

The 200 block of Pine Street extends from Grant Street to Sherman Street in downtown Fitzgerald. This block is dominated by the beautiful five-story Garbutt-Donovan Building visible on the left of this image. Unfortunately, this block has lost two historic buildings within the past decade, leaving a number of openings within the block. A dozen vacant tree wells line this stretch of Pine Street.

This rendering illustrates 10 black gum trees lining the 200 block of Pine Street. Two of the 12 tree wells along this block could easily accommodate a larger canopy street tree. The image above shows two Chinese elms planted in the tree wells bordering the parking area by the Garbutt-Donovan Building.

The block of Pine Street running from Sherman to Thomas Street primarily features single story historic buildings with some later additions, including the Fitzgerald Fire Department Station 1 pictured above. This block includes 12 vacant tree wells, four of which do not interfere with surrounding buildings.

Four graceful Chinese elms bring much needed shade to this stretch of Pine Street. The eight black gum trees selected for the remaining tree wells will grow tall enough to not interfere with the surrounding one-story buildings and storefronts.

In order to remain economically competitive and draw the type of investment and visitors desired downtown, officials at the Fitzgerald Ben Hill County Development Authority noted the need for a convenient downtown electric vehicle (EV) charging station. Demand for EV charging is likely to grow significantly over the next decade. S&P Global estimates that 28 million EVs will be on American roads by 2030, up from two million in 2023. While Georgia ranks 12th among the states in the adoption of electric vehicles, the state has the seventh lowest ratio of electric chargers to vehicles in the nation. Following the passage of the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) and other partners are taking action to bring more EV chargers to communities across Georgia. To support this effort, the UGA Institute of Government has partnered with the Governor’s office and the Georgia Department of Economic Development to create the Electric Mobility and Innovation Alliance. The alliance brings together public officials and business leaders to develop a comprehensive, statewide strategy and relevant public policy to guide the growth of EV adoption in the state.

As electric vehicles grow in popularity, Fitzgerald leaders should thoroughly consider bringing a convenient EV charging station downtown. EV owners often plan routes based on the availability of charging infrastructure. A convenient downtown EV station within easy walking distance of shops and restaurants could enhance the local economy and draw more tourist dollars downtown. Many rural communities are investing in public EV charging stations through the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) federal grants administered by the Georgia Department of Transportation. Other communities have successfully partnered with utilities like local Electric Membership Corporations (EMCs) and Georgia Power to bring EV charging infrastructure to downtown areas. The USDA and other federal agencies also support EV infrastructure development in rural areas. The following concepts illustrate potential EV charging opportunities in downtown Fitzgerald.

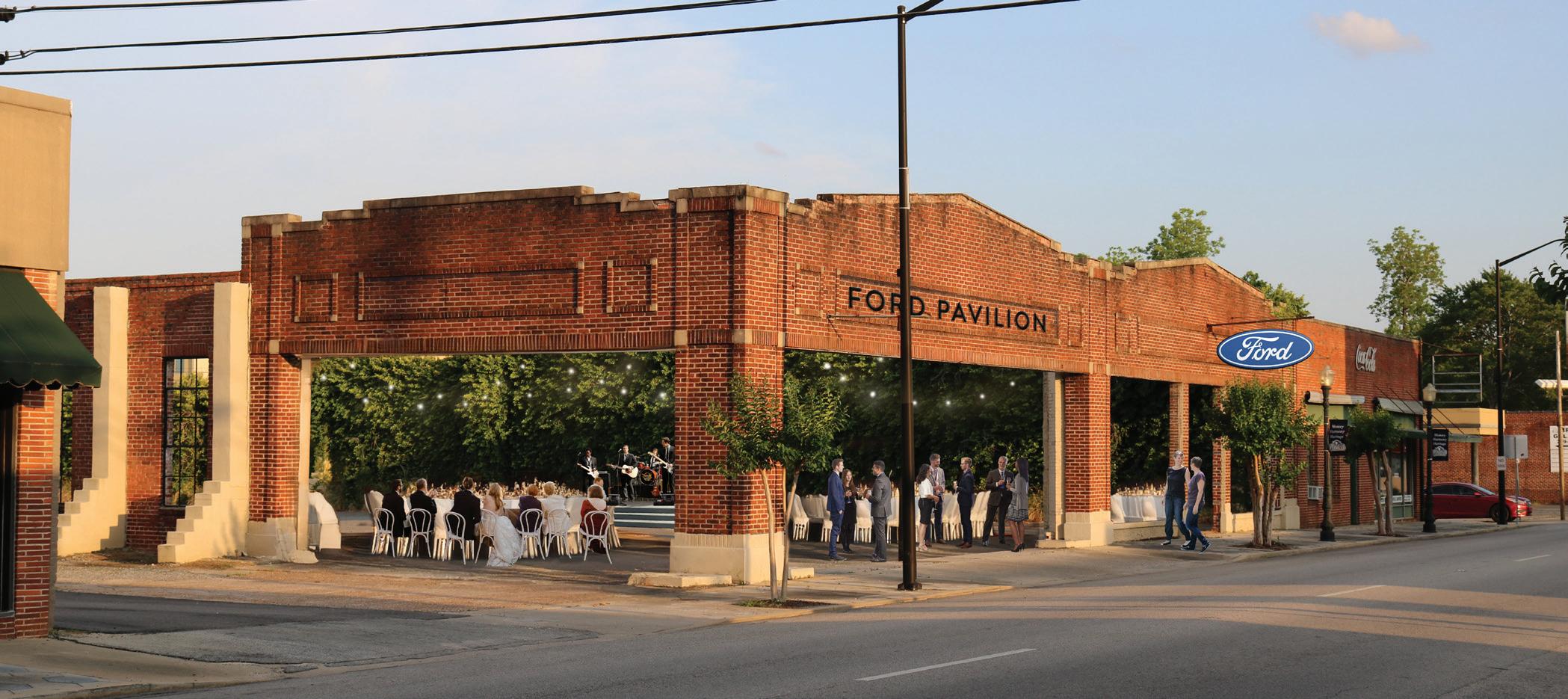

This location on Grant Street once housed the local Ford dealership. The interior of the building was demolished and the corner lot now contains a public parking lot. Because of the tight dimensions of the lot the layout is less efficient than it could be.

Local leaders see the need for a convenient EV charging station downtown. This prominent location could provide one option at an existing public parking area. Enhancing the signage could better signal that visitors are allowed to park in this location. The blue and white signage pays homage to the former Ford dealership that once occupied this site.

In the past this prominent downtown location has been used for outdoor Chamber of Commerce events. Local leaders could utilize this city-owned space as a future outdoor venue similar to the Hook & Ladder in downtown Bainbridge. Rechristened the Ford Pavilion, this space could bring a new gathering space and rentable venue downtown.

The White Swan Parking Lot is a public parking lot along West Pine Street. This unshaded parking area can get uncomfortably hot on summer days.

The White Swan Parking Lot could be an appropriate location for an EV charging station. Planting two Chinese elms in the existing raised planter could add shade and make this parking area more inviting.

Talented local developers and major employers like Mana Nutrition are bringing new life to some of Fitzgerald’s most prominent downtown buildings. As part of the 2024 Fitzgerald Visioning and Design Plan, Institute of Government designers worked with property owners, including Emily Harper of L.E. Harper Construction Company, to reimagine a number of key downtown properties slated for renovation.

The Harper family has a successful record of rehabilitating downtown Fitzgerald buildings, including the iconic former First National Bank (1903) at the corner of Pine and Grant Street. These projects not only preserve the architectural heritage of the city but also stimulate economic growth by attracting new businesses, investment, and storefront commerce to the area. Several of these properties also incorporate upper story lodging, creating a 24-hour population that benefits downtown retail outlets and restaurants.

Through the city’s Community Development Department, Fitzgerald has a long record of incentivizing improvements to downtown buildings and storefronts. Dozens of downtown properties have benefited from Fitzgerald’s long-running façade grant program. This program provides a 50% reimbursement for eligible properties

with a maximum grant award of $2,500. This support helps reduce the financial burden on property owners, making it more feasible to undertake necessary repairs and upgrades. Additional programs including the city’s Revolving Loan Fund help incentivize redevelopment in downtown and throughout the city. The façade renderings and designs developed during the 2024 Georgia Downtown Renaissance Fellowship aim to assist local business owners and developers in making informed decisions about their properties, enhancing the overall economic vitality of downtown Fitzgerald. The concepts that follow range from more modest “can of paint” façade design concepts to detailed site plans for back-of-house service areas. These designs propose both aesthetic and functional improvements to assist local business owners and enhance economic development and investment in downtown Fitzgerald.

The local business Ivy on Pine successfully uses videos on social media to promote their downtown boutique. The proprietors of this business are hoping to renovate their second floor to house an in-house recording studio. The distinctive second story bay window of this historic property is currently covered over and the second floor is used for storage.

Inspired by the Jolly Jeweler façade across Pine Street, improvements shown to the Ivy on Pine façade include sanding and replacing the stucco finish, repainting, and incorporating new historically-appropriate second story windows. Prominent new signage in a crisp, contemporary font better advertises the storefront to passing vehicles.

This circa 1920s image shows the building at 121 Pine Street as home to Johnson Hardware Company. This image shows architectural elements including storefront transom windows and cast-iron columns that have been removed over the decades.

The historic building at 121 Pine Street was home to Johnson Hardware Company in the early 1900s. Lovingly restored by L.E. Harper Construction in the early 2010s, today this prominent downtown building houses the Fitzgerald Ben Hill Chamber of Commerce and the local development authority. The second story of this property houses the Loft on Pine, a three-bedroom boutique lodging rental space.

Property owner Emily Harper provided this image of Clementine Café in Harrisonburg, Virginia and requested a similar color palette for 121 Pine Street. The property owner requested storefront elements including warm wood and a contrasting color on the building’s distinctive masonry detailing.

This façade concept shows the building repainted in a shade similar to Peppercorn by Sherwin Williams. The distinctive masonry banding and other details are shown highlighted in a contrasting lighter gray. This concept features warm hart pine framing the storefronts. Brass lettering clearly indicates the Chamber of Commerce to visitors. The blank wall between the two entryways could provide the ideal location for a downtown business map.

This secondary option features many of the same elements of the previous concept. In this option the masonry detailing has been painted a warm off-white similar to Creamy by Sherwin Williams. This lighter option further accentuates this building’s historic character.

This alternative option takes inspiration from the historic appearance of this building. While removing many decades of paint from a brick façade would be an expensive and time-consuming endeavor, this option uses a red paint similar to Benjamin Moore’s Georgian Brick to reflect the color of the original brick.

Located at the corner of Central Avenue and Main Street, the property at 105 East Central Avenue is undergoing a major renovation. The second floor of this space will soon house a signature conference space and offices for Mana Nutrition, a major local employer.

The developer of this property requested a façade design concept showing second story windows repaired and repainted to coordinate across the front façade. The Central Market storefront is shown repainted in a color similar to Benjamin Moore’s Wythe Blue to better contrast with the unpainted cream-colored brick. The building on the left occupied by Cinderella’s Commercial Cleaning is illustrated with a historically-appropriate storefront renovation that includes new transom windows and dark trim. This design also shows some minor paint touch-ups at the GoFroe storefront on the corner.

This secondary design option shows the storefront at 105 East Central Avenue repainted with a contrasting dark paint similar to Sherwin Williams Iron Ore.

Developer Emily Harper requested a concept plan for the back-of-house area at the Mana Nutrition building. The renovation will incorporate a wide back deck and rear stairway access. Ms. Harper requested a design with the neighboring rear addition removed. The concept plan above shows the unprogrammed rear service area transformed into an inviting rear lawn with room for two large canopy street trees. Five dedicated angled parking spaces off of the existing alley integrate this once overlooked area into the fabric of downtown.

Existing: This aerial view shows the back-of-house service area at the Mana Nutrition building. This space is accessed by a busy east-west alleyway that leads to the parking area of the Fitzgerald Police Department. Neighboring businesses along Main Street also use this area for employee parking and services. The chaotic arrangement of vehicles indicates a lack of defined parking spaces.

Existing

This secondary concept plan shows an efficient, landscaped parking area occupying the back-of-house area at the Mana Nutrition building. This dedicated off-street parking area could incorporate eight new parking spaces to serve Mana Nutrition and neighboring businesses. This concept includes elements pictured in the previous design, including a generous 12-foot back deck, relocated utilities, and the removal of the neighboring rear addition.

Existing: This aerial view shows the back-of-house service area at the Mana Nutrition building. This space is accessed by a busy east-west alleyway that leads to the parking area of the Fitzgerald Police Department. Neighboring businesses along Main Street also use this area for employee parking and services. The chaotic arrangement of vehicles indicates a lack of defined parking spaces.

Existing

The back-of-house area at the Mana Nutrition building shows a mix of cracked paving, unkempt greenery, storage, and utilities. The cinderblock rear addition shown on the right is included in a neighboring property. The roof of the building has partially collapsed and property owners would like to see it removed. It also includes deteriorating paving, overgrown vegetation, and various storage and utility areas.

This cinderblock extension belongs to an adjacent property. The owners are considering its removal.

This concept for the Mana Nutrition building shows a rejuvenated and inviting rear façade. Welcoming French doors with arched transom windows fill the openings on both the first and second floors. Matching new windows fill historic window openings on both floors. Undergrounding utilities and relocating the parking to the perimeter of the site creates the opportunity for a large, flexible rear lawn area. This inviting space is shown planted with attractive and fast-growing street trees like laurel or willow oaks. An impressive rear deck shades the first-floor openings and offers a fine view of the lawn area below. New sidewalks throughout the space link rear entryways with the existing and proposed on-street parking areas. Removing the cinderblock addition could allow for the construction of a new rear storefront at the neighboring property.

Removing the unstable rear addition and relocating on-site utilities could create the space for an inviting rear entryway and efficient parking area. This parking design includes four landscape beds planted with ornamental trees like downy serviceberry. This design concept includes previously proposed improvements to the rear façade of the Mana Nutrition building and neighboring property, including new windows and French doors.

The neglected and overgrown back-of-house area behind Coastal Plain Barbecue Company and 109 Main Street could someday contribute to both of these properties. Emily Harper, the owner of 109 Main Street, envisions a second story lodging or apartment space taking shape at this property. Harper requested a rendering of this space showing rear façade improvements, new parking, usable outdoor space, and the cinderblock addition on the right removed.

This concept shows the back-of-house area transformed into an inviting dining courtyard. Paved with crunchy pea gravel, this attractive rear courtyard concept could bring a new outdoor dining experience to downtown Fitzgerald. Inviting string lights, flexible café seating, and a soothing color palette help make this space an elegant retreat. The preserved large tree bathes this space with refreshing shade. Three new on-street parking spaces serviced by the north-south alleyway provide a dedicated parking area for 109 Main Street tenants or visitors.

Twinkling string lights could make this courtyard the perfect venue for evening meals and celebrations.

For many years a factory at the corner of Lee and Pine Streets produced a cast cement product known as granitoid. Many of Fitzgerald’s historic building utilize this locally-produced material. The property at 109 Main Street features a distinctive granitoid ground floor and two storefronts with historical cast iron pillars fabricated by Fitzgerald Iron Works. The owner of this property sought some options to improve the appearance of the second floor and the storefront on the left.

This façade design concept for 109 Main Street adds a smooth coat of stucco to the second story. Painting the second story with a creamy white paint similar to Sherwin Williams White Snow provides a contrast to the granitoid ground floor. This concept shows the storefront on the left repaired with the trim and doors repainted to coordinate with the insurance office on the right.

This second façade design option for 109 Main Street includes the storefront repairs and new paint featured in the previous concept. In this option the second floor is shown painted a warm gray similar to Gray Owl by Benjamin Moore.

The blank northern wall of 109 Main Street faces busy Central Avenue, making this wall a first impression for many visitors approaching downtown Fitzgerald. The owner of this property requested concepts showing the existing shrubbery and light pole removed and replaced by an inviting mural.

This rendering transforms the northern wall at 109 Main Street into the perfect canvas for a welcome mural featuring the city’s new logo. This mural could be applied using a stencil, allowing the design to be used in multiple downtown locations and repainted easily as needed. This concept replaces the evergreen shrubs with a river rock-lined swale planted with flowering muhly grass. The property owner requested this feature to address stormwater runoff and flooding issues.

Fitzgerald is defined by the city’s palpable community spirit, proud origin story, and determination to thrive. Faced with the challenges of a shifting economy, the city, partners, and the private sector are rising to the occasion, reinvigorating the city’s downtown core building by building. For decades, the city government and partners have successfully and strategically invested in the historic heart of this unique community. From the restoration of the Grand Theater, Carnegie Center, and B&A Railroad Depot, to the ongoing efforts of the Fitzgerald-Ben Hill Arts Council, Fitzgerald evidences a daily commitment to preserving and promoting the city’s unique heritage to visitors and the next generation of citizens. By embracing both historic preservation and innovative economic development strategies, Fitzgerald is successfully attracting new businesses, fostering entrepreneurship, and creating a vibrant community atmosphere that draws residents and visitors alike. The city’s dedication to thoughtful planning and preservation has helped return activity to downtown streets, attracting reinvestment while ensuring that Fitzgerald’s treasured history remains alive for generations to come. Fitzgerald’s leaders of today are actively shaping a dynamic future worthy of the city’s founders– a diverse, resilient, and proud community that honors the past while embracing the opportunities of tomorrow.

Thank you to Emily Harper, Whitney Justice, Jason Dunn, the City of Fitzgerald, and the Fitzgerald-Ben Hill County Development Authority for your guidance and leadership during this planning process. Thank you to the Georgia Municipal Association and the Georgia Cities Foundation for their ongoing support of the Georgia Downtown Renaissance Partnership. We extend our gratitude to the PROPEL program at the Institute of Government’s Georgia Workforce and Economic Resilience Center and the UGA Foundation for making this plan available at no cost to the city.

This report was produced by the University of Georgia Carl Vinson Institute of Government for the City of Fitzgerald. Download digital report: https://issuu.com/rsvpstudio/docs/fitzgerald2024