V

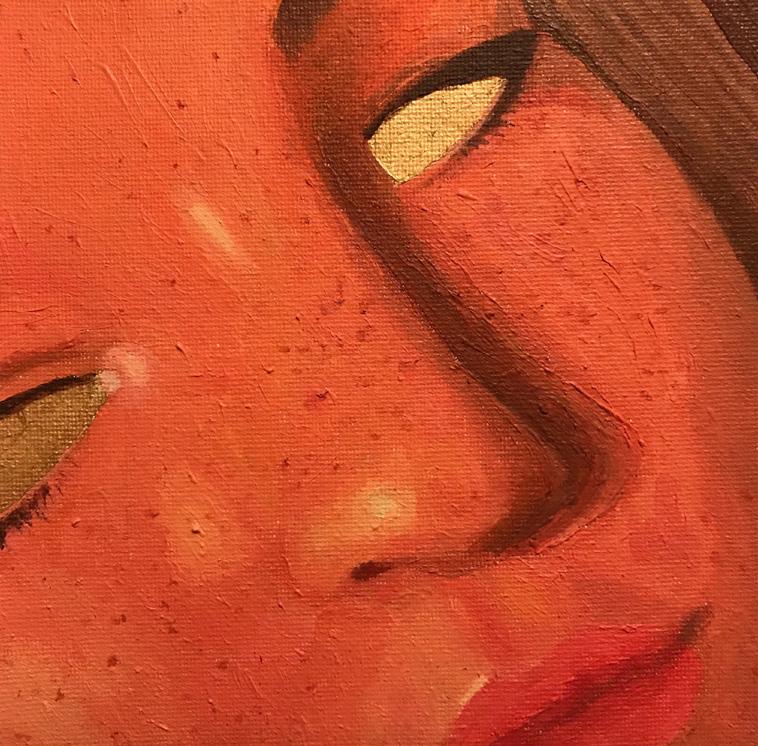

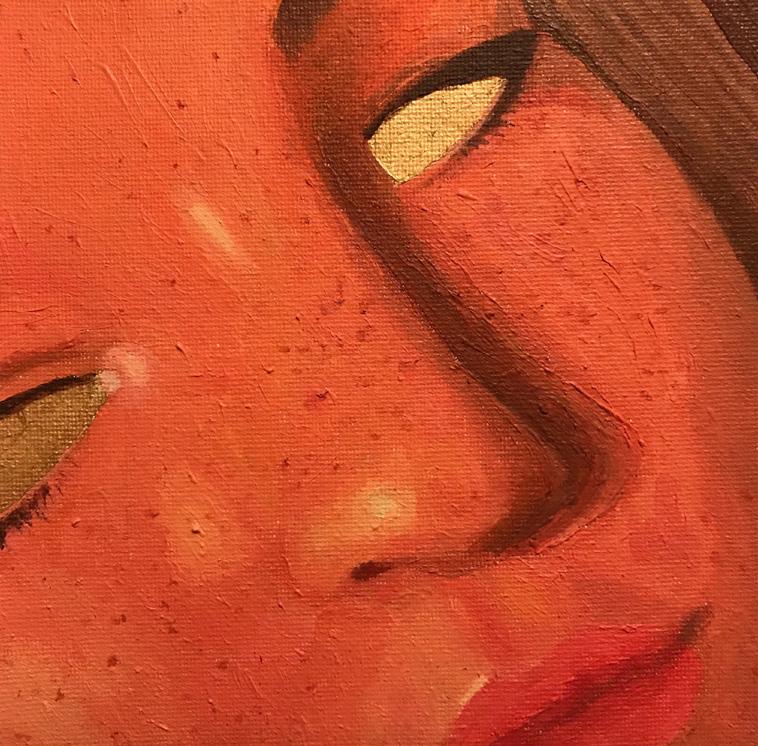

Gold • Isobel Alm

Iris: Art + Lit Vol. V June 2021 • • • St. Paul Academy and Summit School 1712 Randolph Avenue Saint Paul, MN 55105 Phone: 651.696.1459 Email: irisartlit.spa@gmail.com • • • Website: irisartlitspa.wixsite.com/litmag @irisartlit.spa on Instagram

There were so many faces, but I remember each one.

- Nan Besse, Yhdessä Kanssasi, p. 68

If you, like many of us, have spent this past year tethered to a single point in the world, we offer to you this map of new geography. It is a landscape of homes, injustice, intimacy, screens, change, threat, and selves.

The work in this fifth publication is an embrace of the limitations of the past year. How have we been altered by the narrowing of our world? How do we navigate social upheaval, coming of age, and a pandemic from our corners of the world?

These are the questions that shape our Viewpoint.

Rashmi Raveendran

Sonia Ross

Eugene Tunney

Noah Lindeman

Sara Browne

Isabel Toghramadjian

Eleanor Smith

Maren Ostrem

Mimi Huelster

Eugene Tunney

Eliza Farley

Lulu Priede

Sara Browne

Gavin Kimmel

Adrienne Gaylord

Nan Besse

Bev O’Malley

Rylan Hefner

Per Johnson

Annika Brelsford

Elle Chen

Eugene Tunney

Rashmi Raveendran

Maya Coates Cush

10 12 16 18 20 23 26 34 38 43 44 52 54 56 61 68 72 74 78 85 86 88 95 97 SPEECH • POETRY • ESSAY • LITERATURE Journal • Essay / Reflection Dandelions are Beautiful, Lying Weeds • Creative Nonfiction Tanka for Bogmen • Poem I Remember • Poem ALRIGHT • Poem

• Short Nonfiction The Air Above A Campfire • Short Fiction A Celebration of Queer Joy • Speech: Memoir Johnny Cash and the Tube • Short Nonfiction The Lonely Stag • Poem For Want of a Meal • Short Fiction bogo • Poem

me when you get home” • Poem Dead Man’s Trilogy • Poem a ghost • Speech: Creative Interpretation

Kanssasi • Creative Nonfiction the story of my mama • Poem

• Speech

infection

•

A Love Letter to FaceTime • Letter

Harrowing •

“Dreams”

“Text

Yhdessä

What is Music?

Dictionary by Perriam-Webster • Creative Nonfiction

• Poem Untitled • Poem The Gannets

Poem

The Great

Poem

06. TABLE OF CONTENTS

Isobel Alm

Adrienne Gaylord

Evelyn Lillemoe

Isobel Alm

K. Goodman

Val Wick

Lucy Murray

Max Spencer

Maggie Baxter

Ellie Murphy

Sarina Charpentier

Lucy Benson

Mimi Longe

Mimi Huelster

Lulu Priede

Tana Ososki

POTTERY • CERAMICS

Ben Chen

Jack O’Brien

Luka Shaker Check

Saffy Rindelaub

Maggie Baxter

Isle Graupman

Stella McKoy

Leni Nowakowski

.07

DRAWING 01 09 12 17 35 36 38 40 45 53 67 68 80 84 87 96 Gold • Acrylic and Oil Pastel my cology • Pen eyes • Acrylic Storyboard • Acrylic and Cotton 1970 - Donna Summers and Garlic Flowers

Pen and Marker

• Oil Pastel Perspective • Marker, Acrylic, and White Out Self Portrait • Acrylic Girl in the Forest • Acrylic Get Up! • Watercolor and Pen Consciousness • Acrylic Pink and Blue Morning • Watercolor and Pen Mary • Oil Pastel Mine Too • Digital Drawing feeling flowers • Marker La Niña Bella • Watercolor

PAINTING •

•

Camille

18 29 42 46 60 70 73 88 Sculpture • Plastic and Tape Nature’s Coral • Stoneware, Slip, and Glaze Tree in the Yard • Stoneware, Slip, and Glaze Cupcake • Stoneware, Slip, and Glaze Orb 1 • Stoneware and Glaze Blossom Vessel • Stoneware, Slip, and Glaze Untitled • Stoneware, Slip, and Glaze Kiwi Bird • Stoneware, Slip, and Glaze

Isabella

John Hall

John Hall

Isabel Lutgen

Liv Larsen

Mia Hofmann

Nikolas Liepins

Milo Waltenbaugh

Maggie Fields

Hayden Graff

Sophie Cullen

Mac Brown

Pilar Saavedra-Weis

Nikolas Liepins

Vivian Johnson

Gavin Kimmel

Nikolas Liepins

Isabella Tunney

Addie Morrisette

08. PHOTOGRAPHY • VIDEOGRAPHY • AUDIO 10 15 21 22 25 27 32 33 50 54 57 57 66 75 77 81 89 94 Justice • Digital Photo Star Searching • Digital Photo Moon Searching • Time Lapse Video Behind the Mask • Cyanotype playback • Short Film blurry vision • Digital Photo Fall snow in the capital city, October 2020 • Digital Photo Minnesota Public Water #27-31 • Documentary 龙 • Digital Scaffolding • Cyanotype Cycling Thoughts • Digital Photo Self Isolation • Digital Photo Pandemic Portrait • Digital Photo Illustration Chauvin found guilty • News Photo Oneirataxia • Digital Photo Gershwin Wakes Up Singing • Dance Film Backyard Degobah • Digital Photo Minnesota Summer • Digital Photo Stairwell • Digital Photo

Tunney

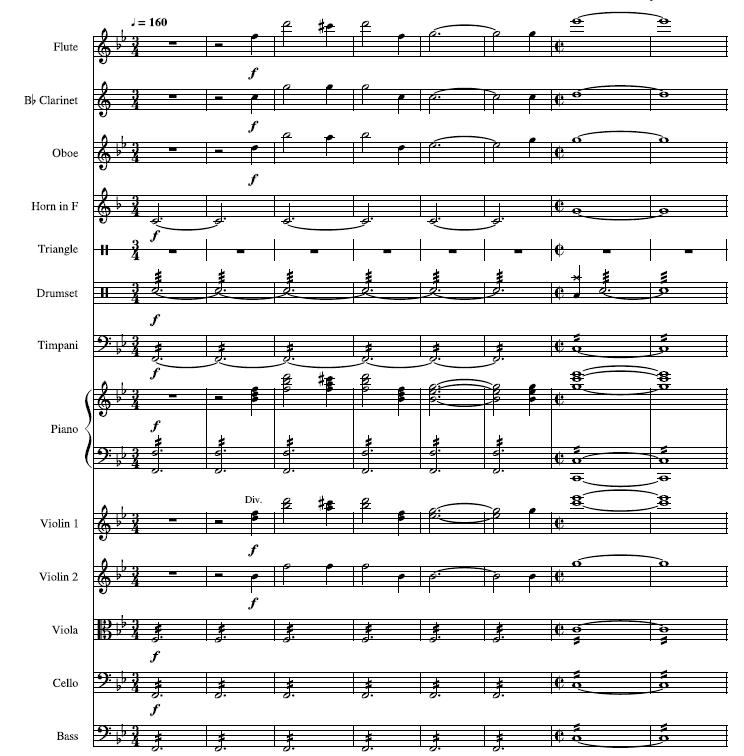

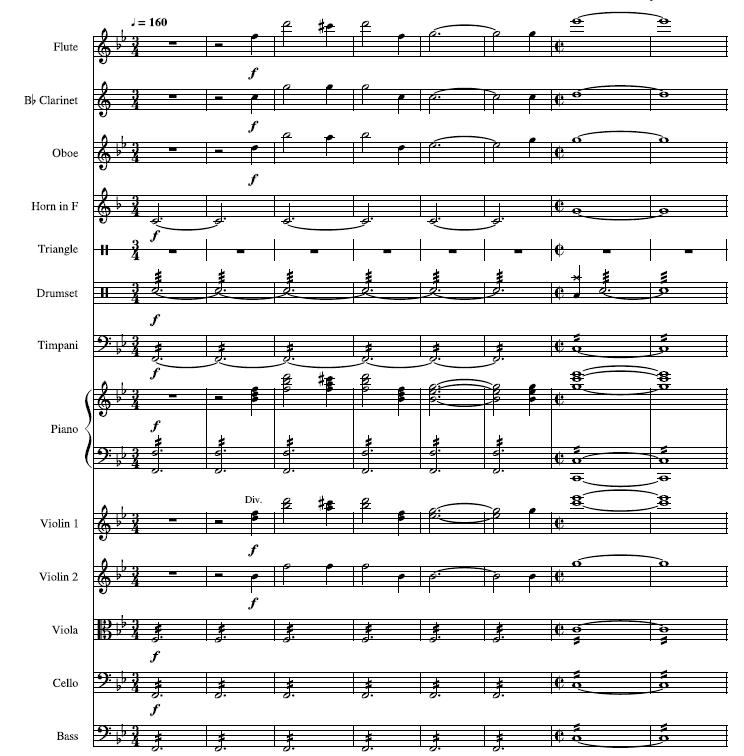

ORIGINAL MUSIC • COMPOSITION 67 90 Consciousness • Original Song Overture • Original Score Sarina Charpentier Rylan Hefner TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTIST PROFILE • VIRTUAL GALLERY 82 Noor Christava Light. Isolation. Beauty. • Q&A and QR Code

my cology • Adrienne Gaylord .09

• Rashmi Raveendran

A poem should be a story.

But, not a story of white fragility. Never a story of oppressive comfort. It should not be a story we already know, a story that’s falsely been taught, or a story that romanticizes one’s view on life while overshadowing the stories that we need to hear.

A poem should be the absent stories. The ones that resist the poems of fragility, comfort, and romanticization of oppressive and prominent voices.

So what stories do people need to hear? 10.

Justice • Isabella Tunney

Journal

The stories of heartbreak. The stories that leave blood on the streets, and echo wails in the face of distress. The stories that threaten white comfort, that threaten the prominent narrative, and threaten the romanticization of societal life. They should cause the audience to look out a window - peering out into the real world, where not everything is about butterflies and happiness, but rather a place where inequality benefits some and harms others.

These stories of harm need to be shared. Poems can share those stories. So we don’t want poems that take away from those narratives - that overshadow them. We don’t want poems that leave the audience walking away feeling the same way they felt before reading it.

We want poems that push. Push the boundaries of one’s mind, and push them to step outside of their comfort zone to think about life in a new way. To think about their life in a new way.

The stories of heartbreak. The stories that leave blood on the streets, and echo wails in the face of distress. The stories that threaten white comfort, that threaten the prominent narrative, and threaten the romanticization of societal life.

A poem doesn’t need to be revolutionary in its description. In it’s words or in it’s tone. It can be revolutionary in its message alone. This is why poems should capture the messages of those wishing to resist oppression. Those who have little room to share their voices in normal lights.

Poems should also be the happy medium of Interpretation.

It should be mystical - something that doesn’t say “I’m being killed”, but still says “I’m being killed”. Something that speaks power, and lives in the mind of the reader for days. Something that lives as a thought, and soon becomes action.

A poem shouldn’t leave interpretation so far as to the majority, though.

A poem doesn’t give those who don’t experience the narrative the opportunity to interpret the experience. It gives them the opportunity to understand. To learn. To see.

See the water we all swim in. Because, like fish, can you recognize water if you live in it? Can you recognize something you’ve been so used to seeing? Can you recognize the tragedy in normality?

A poem can. So let’s give poems to those who need that opportunity. The opportunity to share their story.

To share their words.

To share their life.

“ .11 V

eyes • Evelyn Lillemoe

Dandelions are Beautiful, Lying Weeds

• Sonia Ross

Dandelions live two lives. First as a beautiful yellow nuisance and second as a withering grey seed-spreading wish-giver.

More than three hundred years ago, dandelions snuck aboard a ship and planted themselves into the heart of America, the backyards and boulevards of millions.

Their luminescent yellow petals tower over blades of grass, and their muscled stems are rooted deeply in dirt.

The sunny crowns that sit atop their long bodies beckon passersby and make for the most enchanting of childhood bouquets.

The word dandelion means lion’s tooth, in reference to their toothy, biting petals.

Dandelions are America’s most beloved weed.

The most common cause of death among dandelions is a cheap, violent, and bloody beheading. The roots, which implant themselves ten to fifteen feet into the soil, coiling towards the center of the Earth, stay.

A dandelion’s death is quick and temporary.

Dandelions are the pockmarks of the American backyard.

When a dandelion approaches a natural death, it gives the last of itself to the continuation of its lineage. It grows a silky white halo, which carries and nurtures the dandelion’s seeds.

A child’s deep and firm blow will spread the seeds to the four corners of the country.

The child’s fee is simple.

12.

I wished to become a mermaid. I pushed the air from my cheeks, squeezed my eyes shut, and repeated my wish three times. When I let my eyelids fall open, there was nothing left in my hand but the slim, soft green stalk of my wish-giver.

In 1936, my great grandfather fled Germany for the United States. The boat took him first to Cuba, where he stayed for a number of weeks before completing his journey. After arriving in the US with only a tourist visa, he stayed in New York with the affluent woman who had paid his way.

Behind him, he left his family, who had been rich in drama, nepotism, and loyalty.

He and his American wife, Ethel, raised my grandmother Jewish in Jamaica Estates, Queens, New York. She bore his surname, Glaser.

She was a part of an accelerated learning program with other kids in Jamaica Heights. Her schooling was two years shorter than most and she attended Barnard College when she was sixteen years old. Her class at Barnard was made up of other Jewish girls with stories like hers.

When my grandmother moved with her two sons to Gulfport, Mississippi, where the oppressive air is too hot and sticky to inhale, nothing is said without a theatrical drawl, and everything is fried, she made the decision to keep her Jewish roots a secret.

She announced that the three of them would identify as Unitarian. She enrolled her sons in Episcopal school. She married a Catholic man. She became a Field.

My father took communion.

My grandmother is in love with the idea of being an American. When we speak on the phone, she quizzes me about American war heroes, whose names only sound vaguely familiar to me. She grumbles about my education failing me.

At the age of twenty-five, the first thing she did after leaving my Jewish New York grandfather, who had had his bar mitzvah and knew the Chanukah blessing by heart, was get her ears pierced at Bloomingdale’s and order herself a soda at a Manhattan diner on the corner of 59th and 3rd.

“I felt so grown up when I did that,” she told me as I spoke to her over the phone after she had finished decorating her Christmas tree with hundreds of shimmering white lights and dozens of ornaments. There was Christmas music singing cheerily in the background.

She told me that sipping that soda in the diner on 59th and 3rd was sipping liberty. She told me, sitting there on the vinyl-covered chair at the gingham-clad table for one, drinking her soda, her ears still tingling, she felt free.

Sometimes my grandmother pretends to have a Southern accent. She drops her voice and stretches her words.

On the rare occasion that the two of us talk about religion, my grandmother always .13

brings up the Tom Lehrer song, “National Brotherhood Week.”

“Oh, the Protestants hate the Catholics

And the Catholics hate the Protestants

And the Hindus hate the Muslims

And everybody hates the Jews.”

When a dandelion’s petals wilt, they wrinkle and darken. The flower becomes floppy and weak and embarrassing.

Our family story has been retold hundreds of times, though its accuracy is debated. These pieces are involved in every recounting: My great grandfather worked at a successful brewery owned by his uncle in Berlin. One day, his uncle’s portrait had been replaced by a painting of Hitler. In his own office, my great grandfather found another man sitting at his desk. My great grandfather had a girlfriend. He wanted her to move to the United States with him. Her parents were Nazi sympathizers. Instead of joining my great grandfather on his journey across the Atlantic, she allied herself with her parents. Later, she married an SS colonel. He stood in the way of a train. My great grandfather secretly mailed her money for most of his life.

Dandelions grow in the wake of calamity. They can be found at avalanche sites and throughout the remnants of a burnt forest. They are in love with the disturbing wake of disaster. They thrive in the perpetually mowed lawns of Americans.

My grandmother’s house was completely redone after Hurricane Katrina. The front door now has grand rounds knockers. No one uses the front door. The kitchen is filled with silver surfaces and sleek planes and baubles hang from the ceiling. The kitchen table is glass and I can see my grandmother’s dogs sleeping with their tongues hanging out of their mouths. They rest their bellies on the cold white tile floor. Sometimes they fight. Sometimes they beg for food. They mostly sleep. I can see a lot through the glass of my grandmother’s kitchen table.

Her pantry is filled with food, encased in packaging that warns of delectables within. Rich brownies, creamy soups, and stacks of thick pancakes with maple syrup dripping down their tower decorate the packages in her asymmetrical pantry.

When I climbed up the old two-step stool, grabbed a package, and pulled it open, the plastic crinkled a little too loudly. Inside, I found the dry powder of her failed high protein diet attempt. Or the eight-hundred calories a day attempt. Or the failed vegan attempt.

14.

Moon Searching • John Hall

Star Searching • John Hall

Moon Searching • John Hall

Star Searching • John Hall

There’s never anything to eat in my grandmother’s pantry.

To control the spread of dandelions is close to an impossible task.

To avoid a dandelion-takeover of an American backyard, it is recommended that herbicide is applied while the dandelions are still seedlings, before they truly become lion’s teeth.

Once they turn into flowers, they grow, multiply, and infest.

When my grandmother talks about her father, she does not like to talk about his time in Germany. She says things like, “When I was a little girl,” and “my daddy,” and “bratwurst and lard on toast.”

My great grandfather read the English dictionary until he knew every word.

He was obsessed with the number five. He said it had everything. Lines, curves, edges, everything. He used clay to sculpt the number hundreds of times. Some of his sculptures are bright and vibrant. Others are dark and jagged.

One of his fives lives in my house. It sits on his old mahogany desk with red paint and golden detailings and deep drawers that line the legs and now belongs to my mother. The five is shiny golden black and a thick arrow pierces the center of its belly, pointing forward.

My great grandfather’s fives are beautiful and coated in fingerprints and nail marks. They now litter my grandmother’s house.

One April, we spent Passover in Gulfport. There was no seder. My sister cried. My grandmother tried to soothe her by buying her a pastel pink dress for Easter.

I still walk on two legs.

The dandelion’s seeds have been long spread, and I never collected the wish owed to me.

A dandelion is a weed. It grows and spreads and is beautiful and won’t die without leaving more wicked dandelions behind it.

The United States made promises to my great grandfather when he boarded his boat to Cuba. America swore to him he was leaving the hate and persecution of Germany behind him.

A dandelion lies and breaks promises. I’m still a human. My grandmother tells the world she is a Christian.

V

Tanka for the Bogmen

I’ve seen the men

They’ve unearthed. Frail limbs

Found inert.

I’ve seen their skin, tanned

Black by the bog.

Corpses flattened

By centuries of sod.

• Eugene Tunney .17

Storyboard • Isobel Alm

I Remember

• Noah Lindeman

I remember when the world was normal

I remember when I could go into the world without caution

I remember when I could see my family

I remember when I could see my friends

I remember when thousands of people were not dying

18.

Sculpture • Ben Chen

I remember when the world was happy

I remember when the world was safe

I remember when the world could see each other

I remember exploring the city

I remember exploring nature

I remember being outside

I remember not wearing a mask

I remember breathing the fresh air

I remember hearing laughter throughout the streets

I remember gatherings

I remember concerts

I remember nights out to eat

I remember birthdays, and holiday celebrations

I remember shopping

I remember the twin cities

I remember being free to do whatever I wanted

I remember sleeping over at my friends house

I remember vacation

I remember the beach

I remember normal school

I remember looking at the seniors as a little kid waiting to become one of them

I remember being a junior

I remember wanting to go to prom

I remember wanting to have a speech where there is no seat left unfilled

I remember wanting to have the perfect senior year

I remember hearing about the virus

I remember the first time it was in America

I remember hearing about the first death

I remember thinking that this will not last very long

I remember thinking that it was great to have a break

I remember loving online school

I remember getting bored of online school

I remember when my first friend got COVID

I remember when the next one did, and the next

I remember being in my house all day

I remember being bored

I remember wanting to leave

I remember wanting to go back in time

I remember when the world was better

I remember when the world was normal

.19

ALRIGHT

• Sara Browne

It’s alright, servant to well-being and we don’t want to get into. More or less mentality of in-between irrelevance.

I’m alright, place-holder for all we want to sing and sputter. Substitutes fervor of feeling. Assuring your audience the fall was soft, somehow.

Unattainable, but spaces away is all right. An inconceivable genuity of simply well.

20.

Behind the Mask • Isabel Lutgen

22.

playback • Liv Larsen

We go when the rest of our family is asleep. Sometimes he’ll knock gently on my door, or he’ll text me from the basement. Other nights I’ll wander down and find him on my own. We leave the lights off in the basement and slowly open the sliding door, careful to minimize the rumbling sound it makes as it is pushed along its track. Next is the gate leading from our yard into the side garden. I always go first, wrapping my fingers around the latch as I lift it to create a buffer, making sure that the metal doesn’t clang and wake anybody up. Tommy leaves the gate ajar, ready to welcome us when we come back. We pad down the driveway, still not letting our voices rise above a whisper in case a window is open upstairs. Our street is a quiet cul-de-sac, surrounded by woods that block out any sky that’s not directly overhead. The driveways are long and there aren’t many windows on the front facades of the houses, so that I never feel watched as we make our way towards the entrance of the neighborhood.

109th Avenue is never busy, and at midnight it is practically empty. The road is straight for 2 miles, which means that we can see any car coming minutes before it reaches us. We always turn left out of our street, walking towards the stoplight in the distance. The road cuts through a flat expanse of marsh grass. The woods skirting the fields are a couple hundred yards away, so that on the road we’re exposed. When my brothers come home from tangled Boston or mountainous Armenia, they always comment on how strange it is to see such a vast open space. There is no sidewalk, but the shoulders are wide enough to walk without fear of passing cars. If I happen to be barefoot, the lines of tar put down to repair cracks feel velvety underfoot, providing a reprieve from the gravelly pavement.

We call it sneaking out, but there’s nothing sneaky about it. I leave my bedroom door open and my string lights on, so that if my parents were to wake up they’d immediately know I was gone. Tommy leaves the gate open, even though I worry about deer coming in while we’re away. If a car drives by, I refuse to run and hide in the grass like my brothers used to before I was allowed to come along. Instead we keep walking, eyes up. I talk animatedly so any concerned driver would see that I am not distressed, just out enjoying the night. Tommy worries about being stopped by the police, but I remind him that we’re doing nothing wrong. I wonder what the drivers feel when they go past us. Concern? Fright? I think I would be scared to see us, two kids walking on the shoulder, a mile away from any neighborhood with nowhere to go.

Sometimes these walks are a celebration of sorts, a perfect end to a pleasant day. Sometimes they’re more therapeutic, taken the night before a test or as a break from writing. Other times they’re the way we say goodbye—a way to spend a final hour together, to leave a fresh memory of one another in our minds the night before he leaves again. Whatever the reason, the feeling is always the same.

“Dreams”

• Isabel Toghramadjian

The first time Tommy played “Dreams” by Fleetwood Mac on one of these walks, I didn’t know how to describe it other than to say that it was perfect. The subdued chords and gentle croon of Stevie Nicks’s vocals sound, for lack of a better descriptor, like walking down 109th at one in the morning. The word I’d later settle on is “haunting”. Something about the breeze coming off the marsh, the vast openness of the area, and its propensity for fog lends itself to a ghost story. When the senior living center on the corner of the stoplight was still just a shell-less skeleton and construction lamps lit up its exposed insides, we speculated about what—or who—could occupy the building. Though I didn’t actually believe any of our sinister theories, I felt a surge of gratitude to be accompanied by my big brother.

I wonder what the drivers feel when they go past us. Concern? Fright? I think I would be scared to see us, two kids walking on the shoulder, a mile away from any neighborhood with nowhere to go.

“Dreams” is not the only song we’ve listened to on our walks, but we’ve agreed that it is decidedly the soundtrack of our sneakouts and, perhaps less explicitly, of our relationship as siblings. Since he first played the song for me, I’ve realized that in a way, Nicks is describing us. The song opens with “Well here you go again/You say you want your freedom/Well who am I to keep you down”. Out of my three brothers, Tommy is home the least often. After a few weeks, it’s not difficult to see that he wants to leave. I know it’s not personal—he has connections elsewhere and he feels restless being stuck in suburban Minnesota. I won’t be the one to hold him back, to keep him down.

The streetlight on the corner of Flanders Court and 109th Avenue casts a yellow glow onto the pavement. When we’ve walked out towards the stoplight and back, we pause on the edge of this glow to dance. “Dreams” is a song for walking—when it’s time to dance, he’ll put on something more upbeat—Bobby Darin, Maurice Chevalier, Charles Trenet. Neither of us is a good dancer, but it doesn’t matter on the highway in the middle of the night. We hold each other’s hands and spin around, feeling much more graceful than we must look. I turn under his arm, the music swelling and retreating as the phone speaker in his pocket moves around me. The song ends and he turns the music off. We turn silently back into our sheltered neighborhood. We plod back up the driveway and through the garden, the gate ajar exactly as he left it. I close the latch, careful not to let the metal clang and wake up our parents. We slowly pull open the sliding door, slip inside, hug goodnight, and crawl into our beds.

“ 24. V

.25

• Mia Hofmann

blurry vision

The Air Above a Campfire

• Eleanor Smith

It’s late winter and Leah sits at the bus stop. The sky is pink, easter egg pink, the color of an early morning sky, and the hum of the highway in the distance is the only thing she can hear. She has an empty feeling at the top of her stomach, almost like she’s hungry.

In high school, when she was waiting for the bus, a classmate pulled up.

“You want a ride?”

“Do you come this way every day?” Leah was surprised that she hadn’t seen him before.

“Yeah, but I’m actually running early today. Shocking, I know.”

So Jasper had started giving Leah a ride to school. Leah waited for him at the bus stop every morning, and he would pull over and pick her up. She got so used to the routine: get ready, run out the door, realize she wasn’t actually running late, and then walk the rest of the way to the bus stop. Her family would never be up that early, and she savored her time alone in the empty house.

The early morning air was so still, so peaceful. She would go through the motions, she had her routine down to a science.

The present silence is shattered by the hissing of the brakes.

“You getting on today?”

Leah shakes her head. She hasn’t ridden the bus in months.

“See you tomorrow,” says the driver as the bus pulls away.

Leah watches the bus go past. Sitting in the back row is a woman wearing a beautiful

brown sweater, reading. She has wild curly hair, but Leah can tell it’s well taken care of. The woman looks kind, and Leah thinks they could be friends. As the bus stops to let someone walking their dog cross the street, Leah makes eye contact with her. The woman turns her head and goes back to her book.

The bus lurches around the corner and is gone. It is silent again, and cold. Leah walks back to her empty apartment, shivering, thinking about the beautiful brown sweater.

Jasper’s car had broken down on the way to the state park. It was early March, and Leah was dressed to run, not to sit in a rapidly cooling car. Jasper was walking to the gas station to use the phone. She was rifling around in the back seat in an attempt to find something to wear. Inside his bag, Leah found a big green sweater. She pulled it on and had stopped shivering by the time the tow truck pulled up.

Jasper jumped out of the truck, jogging towards her. As he got closer, he slowed down, and Leah could see that he was smiling sadly.

She grabbed the hem of the sweater and started pulling it back over her head.

“Keep it on. I don’t fit into it, and I want it to get used. Just… take care of it for me.”

It’s warmer today at the bus stop, but a cold feeling still sits deep in Leah’s stomach.

26.

Excerpt

from

The bus pulls up. The brakes hiss and the doors swing open.

Leah sees the woman sitting in the back of the bus, next to the window.

“Hey,” says the bus driver. He looks shocked when Leah stands up and climbs on the bus. She taps her card and walks to the back of the bus. The woman is sitting next to the window closest to the sidewalk, and Leah sits across from her. She glances over at the book the woman is reading: The Sun Also Rises. Leah hasn’t heard of it before. The woman is wearing a thick red sweater with a pattern around the neck.

The heater running along the side of the bus turns on. The trees outside look hazy from the heat, like the air above a campfire.

Ten minutes later, the woman turns to the inside front cover. Leah sees “Renée” written in the book. Renée looks over at her again and shuts the book quickly. On the next block, the bus stops. Renée gets off. Leah gazes out the window at her, sees the corner store behind the bench, realizes that the bus she would take to get to Jasper’s apartment stops at this corner. Renée sits at the bench and watches her as the bus takes Leah away.

It’s April now, and Leah’s toes are soggy from walking through the puddles on her way to the bus stop, in front of the corner store. In the past few weeks, she’s been riding the bus every weekday. She’ll sit across from Renée in silence as they read. Leah used to try to diversify her reading, but Renée seems to like the white

male authors of the early to mid 20th century.

She hasn’t spoken to Renée, but she has spent a lot of time trying to figure out what her life is like. Leah writes all these things down in a planner she had stopped using months ago. Renée only rides the bus on weekdays, she drinks tea every morning. She seems to like black tea: Earl Grey and English Breakfast. Leah bought a box once, but the tea was bitter and

.27

Fall snow in the capital city, October 2020 • Nikolas Liepins

left her mouth feeling dry and her throat tasting sour. Sometimes, Renée gets phone calls from a 206 number, and she frantically declines them. Those calls happen every other Wednesday around 8:05 am.

Renée will get off at the stop in front of the corner store, and Leah will get off at the next stop and walk home from there. Even though she never has a destination, it feels nice to have a routine.

that had started unraveling worries her. Every time she looks at it, heat floods her body and she starts sweating. She knows that one tug could unravel the entire sleeve. She needs to take care of this sweater. She needs to wear it when Jasper comes back.

A door opens across the street. Leah writes down the time in her planner: leaves work Friday, 4:36. She closes the planner and clutches it in her hand.

Leah is wearing the sweater, which is now so worn that it looks less like a knit garment and more like a solid piece of fabric. There are pills of lint coming off it, and a lot of the lint is more gray than green. She often picks them off and throws them behind her, like tossing salt over her shoulder.

Her usual bus pulls up and Renée gets off. She seems surprised to see Leah there, but she doesn’t question it and sits down at the other end of the bench.

Leah wants to say something but doesn’t know what. She hasn’t had a conversation, a normal conversation, with anyone in so long. She doesn’t want her voice to crack. She found out that he was her dad’s friend from high school. “You didn’t know that?” her dad had asked, “That’s Martin Weiss! That’s why he always said hi to you!”

Leah glances at her sleeve. The cuff

Leah stands up and crosses the street. She sees Renée’s sweater, the beautiful brown one that she was wearing the first time Leah saw her, and it is all Leah can think about. It seems so soft, so warm. Leah’s sweater feels less comforting, more constricting. She can’t lift her arms in it anymore, it’s so small. If she could knit, maybe she could weave the loose thread back into the cuff. She wants to make a sweater like Renée’s. Maybe she could ask Renée where she bought the sweater. She stops in the middle of the sidewalk and writes that down. Her hands are shaking, and she can’t feel her fingers, and the handwriting is almost illegible.

When she looks up, Renée is turning the corner. Leah walks faster to catch up. She just wants to see where Renée is going, then she’ll write that down, then she’ll go home. She just wants something to talk about. Leah tries not to think about the cuff of her sweater. The sleeves no longer cover her whole arm, they are so shrunken. The thread blows in the air as Leah walks even faster to catch up with Renée.

They’ve walked blocks at this point.

“ 28.

Leah is wearing the sweater, which is now so worn that it looks like a knit garment and more like a piece of fabric.

Renée is approaching a busy intersection, one with a stoplight. Leah sees the light start counting down. If Leah can’t get across the street, she’ll have to wait until next week. She looks at her feet, and notices, in some distant part of her mind, that her shoelace is untied.

She sees Renée’s back and the beautiful sweater. She starts running. The light is still counting down, and she’s half a block away. She has to make it. There’s no alternative. Her foot lands in a puddle, and she thinks about the first time she spoke with

Renée. That’s why she’s writing these things down. Her next conversation has to be better.

Leah is reaching the intersection. Her foot is wet. Everything feels distorted, blurred, out of focus.

The light turns red, and Leah starts sprinting. The curb comes up, and she isn’t expecting the drop. Leah sees the little red book fall into the gutter, and she goes sprawling into the busy intersection. A car honks. The last thing she sees is Renée’s head turning, finally noticing her.

Nature’s Coral • Jack O’Brien

Nature’s Coral • Jack O’Brien

V .29

V

The time we have spent counting and waiting is unfathomable. When your only viewpoint is your bedroom window, and your periphery is nonexistent, you lose your friendship with time. In response to the clock and calendar slowly drifting by, we bend and stretch, turn and break. As we count and wait, we read and see and hear. We learn words.

vicious. verbose. vacant. variable. voracious. viable. virulent. vulnerable. vital.

Words we know. Words we resonate with, and words we fight against. From these words comes creativity. Beauty pours onto the pages and canvasses that fill our houses. Unlike the strictness of Roman numerals, art and literature are flexible. They flow across the page in a river much smoother than the stream of time. We can use these pieces to declutter our home and our mind, opening our eyes to the world in our periphery that we had lost so long ago. Welcome home.

V

32.

龙 • Maggie Fields

When the construction of Fort Snelling was underway, John C. Calhoun sent surveyors to the surrounding area of the fort to understand geographically where they were located, the surveyors came upon the name of Costco, they decided to give it the name, Lake Calhoun, to honor the Secretary of War at the time, Mr. John C. Calhoun, the inhabitants of this land, the Dakota people have used this lake for centuries to fish, swim, clean, and more. They had already given lake a name, but they Makarska. The name translates to English as per day meaning Lake Makai, meaning earth, and ska meaning white or white Earth lake this name was given to this body of water because of its white sandy beaches.

Minnesota Public Water #27-31 • Milo Waltenbaugh

Minnesota Public Water #27-31 • Milo Waltenbaugh

“

A Celebration of Queer Joy

• Maren Ostrem

I told myself I wasn’t going to write a gay speech. I thought it was too cliche, too predictable. I also told myself I wouldn’t reference the speech writing process, but here we are. Although it may be cliche, I will never forget how it felt as a ninth grader to watch seniors talk openly and confidently about their identities. So here we go.

I came out when I was 13. It happened suddenly, and was entirely unplanned. I honestly can’t explain why I did it like I did, but once the realization hit me, I had the unstoppable urge to tell someone. I texted my best friend, “I’m bisexual.” She was amazing and calm, and rather unsurprised, but I started crying while on the phone with her anyway. In the middle of our phone call, my mom called me for dinner (it was chicken, I still remember) and I panicked. I knew I would have to explain why I was crying, and suddenly I was standing in front of my parents in our kitchen, coming out. It was a silly reason to come out — I definitely could have thought of a reason why I was crying — and it was unceremonial and rushed. They were taken by surprise, much to my amusement now, but I could not ask for a more supportive and loving family.

That was in the winter of seventh grade. I came out to my grandparents next, and then to the world in eighth grade, by posting a set of selfies on Snapchat, this time claiming the label pansexual. The photos are incredibly cringy now — the filter makes everything oversaturated and it’s obvious how serious I’m taking myself — but I try my best to remember that moment fondly. That moment was when I began to feel more like myself.

I cut my hair short and stopped wearing dresses, presenting more “masculine”. I started attending the Gender and Sexuality Acceptance Club and Rainbow Connections, finding a wonderful community at SPA that accepted me with no questions asked. Almost all my friends are queer. I even did my church confirmation project on the tension and beauty that comes from belonging to a church and being gay.

Now, five years after I first came out, I define myself in pretty fluid terms. Gay, lesbian, queer, anything goes. I am not bi, or pan, and am attracted only to girls.

Overall, I am privileged and lucky to feel comfortable as myself and loved by my community. That’s not to say that I haven’t felt “othered” or “different”. Just like so many other queer people, what I long for more than anything is visibility. I crave hearing stories of queer joy, but I know that they too often have their caveats that come with living in a heteronormative society.

34.

I went to my first pride festival the summer before 8th grade. To say that I felt truly seen and overjoyed would be an understatement. The person at the glitter tattoo booth proudly showed off all of their own glitter and joyfully complained about how they could never get it out of their sheets. They called me “honey” and gave me a rainbow Wonder Woman tattoo. Every person I came across treated me like a friend, or a younger sibling. I got a rainbow temporary tattoo on my cheek and on my wrist. I bought my first pride flag and wore it around my neck like a cape. My mom took a super cheesy photo of me, with my hands on my hips, and my brother holding the flag out behind me so it looked like it was blowing in the wind, like a cape on a superhero. I still have that flag, hanging up on my bedroom wall. If you have ever been on a Google Meet with me, you have probably seen it.

I wanted to go to the pride parade the next day, but I had plans to go on a church service trip to Tennessee and Alabama. That night, as I did some last minute packing, I found myself staring at the tattoo on my face in the mirror. Some part of me knew that I wasn’t brave enough to announce my queerness like that in an unfamiliar place. As

.35

1970 - Donna Summers and Garlic Flowers • K. Goodman

I scrubbed the tattoo from my face, the skin irritated under the washcloth, I felt like I was failing every person at that pride festival and like I was somehow not proud enough. Later, in the bathroom of a Pizza Ranch in Missouri, I did the same to the rainbow on my wrist. When I was at the church we partnered with and heard one girl talk about “the wrong kind of love” I felt camouflaged, and I hated it.

I know now that wanting to avoid conflict or stay safe does not make me less queer, or less deserving of the community’s love. I wasn’t ready to come out to every stranger I met in the deep South like I was ready to come out to my friend over the phone. And that’s okay. The tension between pride and safety is all too common, and the reality is that sometimes safety comes first. There are a multitude of reasons to not come out, and

36.

Camille • Val Wick

sometimes, you’re simply not ready. No one reason is more valid than the other. It is a nebulous process that never truly ends.

It has been a long time since I first came out. Five years and a month, to be exact. But I continue to discover new nuances to my identity every day. My journey has been complicated and sometimes I doubt that it is truly over. In moments when I have to share my pronouns in a group setting, I find myself hesitating to say she/her. I have avoided putting pronouns in my Instagram bio, not because I don’t understand the importance of them, but because I struggle to commit to one set. Gender is a whole part of my identity that I don’t talk about very often because I don’t have the answers to my own questions. While I may never formally come out again, giving myself space to change and grow is something I’m still working on.

I was among one of the first people in our grade to come out, so I very rarely have to come out nowadays. It also may just be that I fit just about every stereotype in the book (the hair, the button downs, the theater, the camping.) Still, I remember the feeling of being in the closet, unsure and confused and scared. I remember having just come out, and feeling like I had to justify my identity to every person I talked to. And I know I’m not the first person to do a speech similar to this, but I believe there is value in repeating this message over and over again. There is value in repeating every story of queer joy and struggle and everything in between as many times as possible because that type of normalization and celebration is so, so important.

There is value in repeating every story of queer joy and struggle and everything in between as many times as possible because that type of normalization and celebration is so, so important.

Queer joy looks like the immediate connection I feel to people with similar identities — the little secret codes we have to acknowledge each other, like complimenting pride shirts or certain haircuts, or TikTok trends (which I won’t reveal here — they’re secret for a reason.) Queer joy was when my friend came out to me in middle school and I responded with “me too.” Queer joy is seeing a queer couple in public and making eye contact with them and feeling just a little more seen.

As cheesy as it may be, I hope that my words have resonated with even one person in the audience today. I know that even in a supportive community, coming out is scary. My advice: take your time. You don’t owe anyone anything. You will find your people. They will find you. They always do.

I am proud to be queer. I am thrilled to celebrate that queerness with my community. And I am determined to continue to fight for queer joy.

.37

“ V

Johnny Cash and the Tube

• Mimi Huelster

I was fortunate enough to have been bestowed parents who valued the gift of worldly travel. Having grown up in staunchly low to mid-middle class families, the farthest my mother and father ever traveled as children were the exotic villas of Florida and Iowa, respectively. Therefore, upon having younguns of their own, they resolved to make sure my siblings and I saw as much of the world as we could until my father convinced himself that if he had to sit in one more airplane, his legs would never move again due to extreme clottage.

38. Perspective •

Lucy Murray

The summer before my freshman year of high school we crammed ourselves into those plush blue pleather seats at the very back of the airplane, barely tolerating the scent of rehydrated chicken alfredo wafting behind us, and ventured off to London.

Our stay in the British man’s New York was quite pleasant. We stayed in Notting Hill, which my mother enthusiastically reminded us time and time again was the setting of the film Notting Hill. My siblings and I were mostly excited that we were staying two blocks away from Portobello Road, as featured in Disney’s Bedknobs and Broomsticks, hoping to see tantalizing choreographed dance numbers displaying the United Kingdom’s vast imperialistic and colonial reaches. Alas, all we found were £5 shirts that displayed the phrase “I AM COME FROM SPACE.” Needless to say, we were equally satisfied with our experience.

Another aspect of London I was especially excited for was public transportation. Nowhere else in the world has there been such an idolization of buses and trains. The New York subways are filthy, the San Franciscan railcars frail memories of antiquity, and the Parisian metro overrated, much like Parisians themselves. In the hierarchy of public transportation, London reigns supreme.

London’s trains are clean and well-managed. There are very few strange odors, spilled meals, or attempted gropings to bear witness to. While the absence of unpleasantries were nice, we quickly realized you cannot escape the candidness of our fellow man.

Halfway through our stay, we were riding the train back to our local Underground station and discussing where we would purchase dinner for that night.

A couple seats down stood a stoutly Englishman, sporting the traditional attire of offbrand Adidas track pants and a sweat stained T-shirt. The Englishman swung his way down the traincar toward my family much like the way a monkey would, one rung after the other, until he planted himself next to my father.

“Oi, are you lot American?” He brashly inquired, his accent forming a melodic tone to match the screech and squelch of the wheels beneath us.

“Yes, yes we are,” my father replied.

One thing I have noticed about my father over the years is that, when faced with the task of conferring with an unprompted stranger, he straightens yet arches his back, as if to show that, while he may appear to be a young, Indiana Jones-esque male, he has seen a couple tours around the sun for himself. He also widens his stance, pointing his feet outwards, as if to show the stranger he may run, lunge, or kick an incoming soccer ball at any moment. It was in a moment like this that he assumed his fighting stance.

“Where from? In the country, I mean,” pressed the Englishman.

“We’re from Minnesota,” said the lone defender of our nation.

“Minneapolis, Minnesota,” piped in my mother.

“Oh. Never ’eard of it,” replied the Englishman.

There was a noticeable pause, and then the Englishman promptly continued.

“Y’know, I’ve been to America a few times meself.” There was an air of pride he had which was undeserving of the phrase.

.39

“Oh yeah? Whereabouts?” said my father. This is another characteristic my father develops as soon as strangers are involved — genuine interest in other people’s stories.

As that at the time of this encounter with the Englishman I was 14; I was already embarrassed to have anyone speaking to myself or my family at all, but having my father encourage this bizarre individual’s behavior mortified me. I shot a quick, pleading look at the patriarch, begging him to stop egging this man on.

This tactic of self-preservation was to no avail.

“Oh, y’know, I’ve been to Florida and Times Square and the like… Las Vegas is my favorite city of your’s, though.”

“Oh, really?” said my father, clearly amused. He thinks this is funny, I thought to myself. I was in a desperate state.

“Yeah, I love gamblin’, but the music was great, too.”

“Ah, yes.” I could see my father’s eyes twinkle. I wanted to strangle him.

“What kind of music do you like?” piped in my mother once more, realizing the effortless torturing of her children that was about to ensue. I began to make plans for emancipation.

“I love yer country music, I do,” the Englishman said, clearly happy to have an audience.

“Y’know, Johnny Cash and sorts.”

And then, with absolutely no prompting whatsoever, and to my horror, the man began to sing: “I fell in to a burning ring of fire…”

I was going to kill myself.

“I went down, down, down…”

The train was still moving. Maybe I could open a window and jump out. The fall might not kill me, but at least the rats could eat me alive.

“And the flames went higher…”

Or maybe the train rats would accept me as their own. Over time, I’d grow closer 40.

Self Portrait • Max Spencer

to the Rat King and his family. That is, at least, until the Rat King dies from mysterious circumstances, and it is revealed in his little rat will I have been named the next Rat King instead of his eldest son, Ratthew. I graciously accept this shocking turn of events, but Ratthew is less inclined to follow. The Great Rat Civil War ensues, tearing the very fabric of ratkind until there is nothing left except me, Ratthew, and the Royal Rat Throne. Ratthew and I battle until I humbly concede, realizing this is not my place in the world. I gently pick up Ratthew’s bloodied body and lay him on the throne, where he regains his strength after I nurse him back to health. Once he is well enough to assume his role as King Ratthew IV, I climb a sewer ladder and enter the human world. Upon clambering out from the manhole, I am hit by a car, and dumped in the Thames, where my body floats out to the Atlantic Ocean.

“And it burns, burns, burns…

The ring of fire… The ring of fire.”

The Englishman had stopped. His performance was complete.

My siblings clapped enthusiastically, side-eyeing me with a look of pure evil. They knew what had just happened to me, and they sprung at the opportunity to rub salt into my cavernous psychic wound. My parents not so much cheered the man as gave him gentle words of approval. They had seen me suffer and loved every second of it.

And, with the final twist of the knife, the other passengers in the car clapped and cheered along with my family, giggling to themselves. I hated all of them. How dare they treat a guest in their own country this way. Xenophobia, that’s what it was.

The Englishman, feigning bashfulness, did a slight curtsey. I looked at him with sheer disbelief. How someone could possibly wave all sense of shame and talk, much less sing, to a troupe of strangers in a public, close-quartered train was beyond me. In some ways, I envied him.

The train lurched. We had arrived at the next stop, and it was time to get off. My family said goodbye to the Englishman, and I attempted a slight nod of acknowledgement, but the weakness of my knees prevented me from performing any more of such gestures.

I staunchly believe that English people get a bad rap. Not for the genocide, or colonialism, or inbred ceremonial icons, but for being rude people. Looking back, the Englishman had no intentions of being impolite whatsoever, and the same goes for the other English passengers on that train that day. He was simply being himself — a friendly man, who goes out of his way to make foreigners feel loved in a strange and unnatural landscape. And while I reacted with embarrassment and horror, I am glad he did what he did. At an age as vulnerable as 14, his unabashedness fueled my will to be, more or less, myself.

“ .41 V

I was already embarrassed to have anyone speaking to myself or my family at all, but having my father encourage this bizarre individual’s behavior mortified me.

in the Yard • Luka Shaker Check 42.

Tree

The Lonely Stag

• Eugene Tunney

I woke up one morning, as if divinely, And walked through the woods I saw in my dream.

The silver stream was there to welcome me And I followed its lucid flow Into a world unknown.

TURN BACK! TURN BACK! The ravens screamed. But the river continued to usher me.

Deeper and deeper we went Until the sun could no longer spy on me Through the crowded leaves.

There the river abandoned me. In this ring of mossy trees. I trudged upon their sacred ground And heard a rustling abound.

I turned to face the gentle beast, His antlers turning As he examined me.

O what resemblance I bear to thee, Lonely stag on a walk like me. He seemed to nod as he—

But then the ravens crashed through the crowded trees. I looked up to see them circle me Proclaiming it was time to leave.

I returned my gaze to the pensive stag. He was already gone.

For Want of a Meal

• Eliza Farley

The cold hand of famine gripped the village. It first stole the grain from the fields, then from the storehouses, until the only things to eat were the crusts of rotten, molded bread. Then, not even that. Terrible, lingering hunger that never relented — it felt the ribs of the townspeople through their skin. But one woman, who passed through the square on occasion, never became painfully thin like the rest. She would pay a curt greeting to the young girls sitting on the fountain’s edge, nod to the men fixing their hats in a window’s reflection, and wrap herself tighter in her many shawls before continuing on. As the crows in the trees cried out, it was almost if she had never been there at all. If you were to follow the woman out of town, you would reach a worn path that led into the dark forest. As the pines and the junipers towered over you, blocking out the remains of the watery winter sun, you would become frightened. You would turn back. Eventually, all who tried to follow the woman into the woods did the same. The loose earth of the path contained many sets of footprints, and then, with a short incantation spoken under the woman’s breath, only one. She continued on alone. The trees thinned out as the snake-like path wound deeper into the forest, and finally revealed a clearing about a mile in. The woman’s mouth broke into a smile at the sight of her house, sitting in the middle of the clearing; she never liked to leave for long. The smell of it, of course, had reached her long before she could see it, wafts of butterscotch and molasses mingling with the crisp breeze. She almost laughed to herself, thinking of the starving villagers as she lived in luxury. Why else have a gingerbread house, if not to taunt those stupid enough not to find it?

She crossed the lawn and walked inside, closed the peanut brittle door behind her, and hung her shawls on the peppermint hooks. Now, a different smell: the comforting scent of meat in the oven. The woman took in a deep breath. Savored it. Then, realizing it must be almost cooked through, she hurried into the kitchen and opened the oven door. Ahh. Nothing like the delicate aroma of a young child, fattened on the very confectionery her house was made of. Her smile never faltered as she placed the poor thing on her candy-glass table and began to cut into its flesh; in that moment, it felt to her as though there was nothing more to life than pure indulgence.

A few months later into the famine, the witch-woman was returning home from the village one day when she noticed something most unusual. Although she muttered her spell as always, there were footprints that seemed to remain on the path — someone, or

44.

“

Why else have a gingerbread house, if not to taunt those stupid enough not to find it?

many someones, had crossed into her dominion against her will. Fearing the worst, she sprinted to her cottage as quickly as her legs would take her.

Although she was not old for a witch, she could no longer keep up with the blackbirds flitting through the boughs of the trees as she could in her youth. She broke into the clearing with adrenaline still fiercely coursing in her veins, and she scanned the field with a sick kind of determination. Prey is prey, even if it’s crafty, she thought, but her hair stood on end nonetheless. Approaching the house, she peeked around the corner with wide, wide eyes, and had to look twice to make sure she wasn’t dreaming: not one, but two children, a boy and a girl, sitting and gorging themselves on her licorice siding.

“Hello,” said the witch.

The two children promptly screamed. Spotting the woman, they tried to scramble away, but their laps were too full of candy for them to escape quickly enough. The witch simply laughed at their performance with a smile that didn’t quite reach the eyes. “Don’t worry, you two. Why, my house is practically falling apart already! Why should I care if a few hungry kids have some for themselves?” And they were hungry, visibly so — just like most everyone in town, their arms had grown skinny and their eyes were sunken in. Still, her words brought some relief to their emaciated faces.

“...We’re really, really, sorry, miss,” the boy began. “We’ve been out in these woods for a while, and… well, I’m sure you know. My sister and I didn’t mean anything by it,

.45

Girl in the Forest • Maggie Baxter

Cupcake

Saffy

Rindelaub

I swear.” He smiled weakly, showing off the chocolate stains on his lip.

“Oh, I understand completely, you poor mites. Why don’t you come in, and I’ll fix you a proper meal?” The witch grinned again.

And so the three of them entered the house. The two children settled in the kitchen, tracing the swirls in the candy-glass with their fingers and whispering to each other. The girl laughed every so often, and the boy looked so pleased to see her happy that they seemed the most content pair of siblings there had ever been. Soon enough, the woman returned with a chicken that she placed in front of the two.

“Here.”

The two cautiously stuck their forks in and began to eat, slowly at first, but then more and more ravenously, until all that was left was a skeleton. Just as soon as they finished, the witch brought out a turkey and quietly took away the first plate. After exchanging glances, the siblings began to eat again and finished the turkey, too. The witch kept bringing out more and more fowl, and the children kept eating whatever they were given. The plates were filthy with grease and fat pieces. Finally, after what seemed like hours, the girl raised her hands as if defeated.

“Please, miss, we’re full. Please stop bringing us food. We would hate to waste it.”

Now, the witch determined, was time. She was growing hungry herself, and so she smirked, a cruelty entering her eyes that she had carefully cloaked thus far. “Oh, are you? Really? Because I don’t think you’re done unless I say you are.” The girl’s eyes widened and a new kind of terror sunk into the room. The boy slammed his hands down on the table.

“You’ve been very kind to us, but I think we have to go! Come on,” he said, tugging at his sister’s sleeve. “I don’t like it here.” But the witch moved with the agility of one half her age and blocked the door.

“You can’t leave. I don’t know what’s so unclear about that.” So close, my next meal. So tantalizingly close. The witch bared her teeth, eyes wide. Never had the children seen such a monster. “I’m going to fatten you up, you insolent starving brats. You won’t But an oddity occurred. No matter how many days passed, the boy never seemed to gain weight, and yet the bird was always gone. The witch was growing impatient. Her temper was thinner than ribbon-candy, and her hunger threatening to overtake that of the famished villagers. Finally, after days of waiting, she thought of an idea. He won’t

46.

“

The witch bared her teeth, eyes wide. Never had the children seen such a monster.

eat. I’ll just have his sister instead — she must be quite delectable by now, if she’s been the one helping him. So she called her out of the basement. On unsteady legs she surfaced, her eyes squinted against the filtered afternoon sun. Sure enough, her face had filled out and become a healthy shade again, far from the sickly pallor of before. Her eyes bored into the witch’s face.

“You thought you’d be safe as long as you protected him, right?” The witch barked out a laugh. “Well, the jig’s up. And to punish you, I think I know just the thing. Get over here.” She clasped her hand around the girl’s forearm and yanked her in front of the oven. “Go ahead. Turn it on and get in.”

The girl stood there for a second, then simply said: “I don’t know how.”

The witch paused. “Really, you say? Really. Hmm. How do you not know how to work an oven? It’s quite simple, you know. Even an idiot like you could figure it out.”

“I really don’t know, miss. I’ll…” Her voice shook. “I’ll get in, but I need you to show me how.”

A sigh rang out. “I guess. I guess I can humor a girl’s last request. If I can prove how stupid you really are, I suppose this will be quite amusing indeed.” And so the witch stepped in front of the girl and opened the door. “You see, you just—”

Oops.

From her back, the witch felt a forceful shove, far more hard-hitting than any other blow she’d ever felt, and tumbled into the giant oven. The iron burned her, and she scrambled to find purchase and escape, but every rod on the rack was red-hot. With a deafening clang, the door swung shut, and she could hear the latch falling into place. No. It wasn’t supposed to end this way. She swiveled around, skin nearly melting on the tortuous rods, and banged on the door until her fist, too, was branded with burns and scalds. She screamed. First curses, then pleas, then unintelligible rage. She could hear the children taking their sweet time escaping her house and stealing her every possession on their way out, until they would finally take her life. She sobbed. She had been beaten at her own game, she could admit that much. Maybe they’ll eat me, too. With the last of her strength, she could hear the familiar peanut-brittle door swing open. Take me with you, she wanted to say.

And with the children’s first steps towards freedom, the chapter of the witch’s cruelty had been firmly closed by the cold hand of death. V

.47

This past year has switched the lenses on our understanding of the world. Forced to linger on the small things, forced to distill the catastrophic, the world becomes distorted as it reaches our vantage point. And because perspective is central to any creative expression, that contortion of the truth shapes the words, images, and brushstrokes on these pages.

The points you see are not periods, rather pins in the map - a step on your journey. They are keyholes opening you to new experiences. The point is something to make, a physical space, a place of focus, a pause, a detail, an ending. How does point of view change when you can see the full picture? You won’t know for certain unless you turn the page.

Scaffolding • Hayden Graff

Scaffolding • Hayden Graff

my pigmented love, wishful green wisp for you has gone. it slipped between my fingers, like honey from a jar and disappeared under the kitchen rug. i believed that after nights of hazardous fairies and braiding locks of sandy pink paper hair, we would be one.

no more do i call you or you call me in the evening, and share stories from a blissful perch in the brown attic. forget happiness, this was a dedication that we both failed. to be one.

52. •

i think about it all during the winter, because the destinations to which i walk are silenced by snow packed tightly around my cold ankles. i don’t have to think about what i missed and what you missed. i can just listen to nothing. that bittersweet nothing.

• Ellie Murphy

• Ellie Murphy

.53

Get Up!

“Text me when you get home”

• Sara Browne

The walk across the street will test my nerves. I cross my fingers, clutch my keychain mace in hoping there’s just space under the car. (this episode seems too familiar) Eleven twice I see atop the dash I click the lock at least eleven times. Impatience creeps, backseats await the gas, my music blasts to drown out any fear. I question palpitations in my chest, no time to walk among the moon and stars. Next door, nearby, all neighbors went to bed at nine. No danger waits behind that bush, this time yet quick consistent runs inside persist.

The dark, no childish, simple fear of mine, just all that comes with staying out at night.

Cycling Thoughts

• Sophie Cullen

• Sophie Cullen

54.

Dead Man’s Trilogy

• Gavin Kimmel

I. Flowers He Loved

In time that’s passed, I’ve come to see You learn a lot when someone dies

Of flowers from across the sea

That guide the dead as up they rise

The smell of life soon fills the air

As all the colors shed their light

They stop us falling in despair

And let us walk through endless night

But purple flowers cannot be

The violet is but a disguise

Pollen is yellow, for the bee

I’m eating flowers made of lies

56.

Pandemic Portrait • Pilar Saavedra-Weis

Self Isolation • Mac Brown

Pandemic Portrait • Pilar Saavedra-Weis

Self Isolation • Mac Brown

II. Take a walk around a dead man’s house. The empty sofa, the half-read novels, the Blu-ray DVDs. Everything thick with the smell of cigarettes. He started smoking inside when the weather was nice, when he could just open his window, the hot ashes falling onto the street below. But now it is cold.

Abandoned Farmhouse. By Ted Kooser. Something went wrong, they said.

What killed him?

Was it old age? Or was it the cigarettes?

Trick question. It was cholangiocarcinoma. Bile duct cancer. But it might have been the cigarettes.

Did you know there around thirty cancerous cells in your body at this very moment? But you are young, and healthy, and they won’t hurt you.

But if they do, they will replicate rapidly, an exponentially growing clump of poison, disobeying the laws of nature and creating their own cell cycle. The repetition of growth and division, growth and division, without thought or recognition. But you’re still the one in control, right?

It’s still your body, right?

Take a walk around a dead man’s house.

They say he made a good end. His death paid tribute to the brilliance of his life. Step gently, careful not to break a memory.

There is a soft whirring.

Like the cancerous cell cycle, a record player, no record, spins its plate in slow circles. And you can’t turn it off.

58.

III. Don’t Send Me Flowers Please

There are so many flowers in my house

The classics: lilies (poisonous for the cat), tulips, roses, then there are ones I don’t even know the name of but could describe in great detail

Like those little white flowers on thin stems that bundle together to form a collection of dots, all crowded into single amoeba of pin-sized petals

A bouquet or two around the house are nice, But not twenty-three (there are two vases in each room)

That’s too many vases

Too many flowers

Instead, send me memories

Send me love, send me support

Don’t send me plants, dying upon arrival

That’s just twenty-three reminders of death

Their sunshine just brightens the mourning (or lack thereof) in my heart

Their color will wither and die. And then what?

Send me stories about your family members who have died

Send me connection

Send me moments, like finding old pictures he was using as a bookmark

Send me tears

I need to cry

I naively thought, at first, that I wasn’t afraid of death

Because being afraid of death? That’s for children

Death is unavoidable. It’s one of the beautiful parts of life

But then

think of our other, rational fears:

heights, serial killers, bridges, the ocean

The reason I’m scared of those things is because I’m scared of getting hurt

And getting hurt means

the distance between life and death narrows

It’s there, at the basis of all fears

And I’m afraid of it.

.59

60.

Orb 1 • Maggie Baxter

The Ghost

• Adrienne Gaylord

There was a ghost. It had died in some morbid way. Whether that had been at the knife of an outraged lover or auto-aquatic asphyxiation the ghost didn’t remember and found it of little importance anyway.

The ghost lived in a house, like many ghosts do, and it spent a majority of its time gazing hauntingly through window panes on the second story, like many ghosts do. While it stared, it wasn’t deeply contemplating its state of existence or thinking about the profoundness of nature and ghosthood. To be honest, it didn’t think about much at all. Most of its thoughts were observations.

“There’s a mouse in the bush.”

“That child is ugly.”

And so on.

The ghost couldn’t remember.

Anything.

Daily haunts through the house never brought any satisfaction or inspiration to the ghost. All its actions were aimless. The ghost had little idea of where it was going to be, just as it had little idea of where it was now. When one doesn’t put in thought to make a thought, one’s reality will reflect that lack of effort. Yet sometimes a thought will slip through in an incident of deliberate happenstance.

“There’s a photograph under the radiator.”

The ghost bent down and picked it up. The ghost blinked for a minute, staring at the image as its mind cobbled together what it was looking at. Onto the ghost’s lips a lost smile meandered. The ghost stood. The ghost stared. The ghost blinked, and then its eyes grew wider. The muscles in the ghost’s face fell delicate and the strength to support the smile slipped. It shivered, shook. Fat tears soaked into the surface of the photograph. The ghost hurt.

In the morning the ghost awoke to the warm shifting of the sun under its eyelids. It was a pile on the floor. Its body ached. Its eyes were raw, the skin beneath them soft. When it opened its eyes it felt the sunlight caress the dewy skin of its cheeks. The house smelled new, and yet familiar.

It stood up and began to walk the house.

“The peonies are in bloom.”

“There’s a cat stuck in the banister.”

The ghost chuckled to itself. It stopped. Confused. It stood. It stared. It went upstairs.

.61

“There’s a mouse in the corner.”

The ghost walked over to the mouse and squat down to the floor. The mouse was trembling. It frantically ran crazed loops. The ghost extended a finger to pet the mouse, an attempt to calm it down, but the ghostly finger phased right through. It sent a shiver down the mouse’s spine. The mouse stopped abruptly and fell onto its rump.

The ghost stood up and, after exploring a few kitchen cupboards, it found a cup. The mouse was still sitting in the same spot the ghost had left it, so the ghost scooped the mouse up and carried it outside. It looked around the yard for a pleasant spot, then sat down and released the mouse into the peonies. The mouse slid out like a lump. Then it got back up off its haunches and skittered away.

...lately I’ve been noticing things and there’s this sensation. As if there used to be something connecting what I see to what I’ve seen.

That night, for the first time in a long time, the ghost dreamed. A little after midnight it shook awake from a terrible nightmare. Once awoke the ghost couldn’t remember what it had seen. The ghost got up to see what else was awake at this hour. The cat was. The cat sat on the middle of the couch in the living room. It licked itself with its sandpaper tongue and sheltered an object to its chest with a single paw. The ghost smiled and sat down on the couch next to the cat. They sat in silence before the ghost addressed the feline.

“I can’t remember anything.

“Yet... lately I’ve been noticing things, and there’s this sensation. As if there used to be something connecting what I see to what I’ve seen. I’ll feel things and I don’t know why. Like, a bit ago I saw the sun set into a beautiful warm horizon, and I felt butterflies in my stomach. Why? I want to know what’s happening. Why is this happening? I want to remember what happened before I couldn’t remember. I can’t stand constantly pulling up empty. It hurts. Not knowing. I hate it.”

The ghost looked over at the cat and smiled, asking to be seen. The cat looked back at the ghost. Their eyes locked.

The cat slid away its paw to reveal what it had been coveting.

62.

“

It was the mouse. It lay limp on the couch, its fur matted, it’s limbs mangled.

The ghost stared at the cat. Something burbled in the ghost. It felt like a goo coated the innards of the ghost’s form. Its throat closed up, its muscles became dense, its breath, heavy trying to lift all that was weighing it down. The goo began to drip out of the ghosts eyes. The ghost widened its mouth in an attempt to wail it all out, but no sound came. No matter how hard the ghost screamed it couldn’t manage a whimper. It was congealed in anguish. The ghost wished it was who it was just yesterday. When it didn’t hurt. When it didn’t remember how to hurt.

Sometime in the night sleep came to the ghost.

It awoke the next morning once again to the warm shifting of the sun under its eyelids. The air felt fresh even though the sunlight illuminated the clouds of dust floating through the room. The cat had gone. The family was not yet awake. The ghost watched the dust dance through the air. It was beautiful. Like watching millions of miniature ghosts soaring through it’s living room. The ghost got up to join them. It couldn’t feel them on its skin, but it knew they were there when it waved its arms through the air. It wanted to join them. It spun in a circle. It jumped up onto the couch. It watched a mushroom of them fly from the cushions. The ghost laughed. Not a hearty laugh, but a memorable one. The ghost stopped wandering aimlessly about the house. It stopped blankly staring through the second story window. Some of its thoughts were observations.

“The ugly child has an ugly dog.”

Some of its thoughts were more profound.

The ghost fed birds. The ghost drew faces in the dirt. The ghost felt grass between its toes. The ghost watched people get older. The ghost grew to accept that it was going to hurt on occasion, because it knew that occasionally it would also feel nice. Making itself numb didn’t just block out the bad. It couldn’t feel exhilaration without shedding a tear every once in a while. There’s intricacy to every emotion. Spectacle in the small parts. Purely the ability to feel is beautiful, and the ghost could see that now. The ghost smelled flowers. The ghost took naps. The ghost...

On Monday August 17th the ghost ceased. It was over.

.63 V

Did you notice the space? The space following the point? It was invisible, but that gap is always there. It’s the room for embellishment, misinterpretation, and inspiration between reality and our perception. Perhaps, understanding someone else’s story the way they do is impossible, but to be subjective is to be human. Viewpoints limit what we can see, but they also make a space for creativity. The lives and lines that fill this art and literature magazine are products of that space between.

Consciousness • Sarina Charpentier

April 20, 2021: Chauvin found guilty • Nikolas Liepins

66.

Yhdessä Kanssasi

• Nan Besse

| The Depot |

There is a familiar place that secretly everyone knows. A place where the lost come to mourn their dead and the nearly-dead come when they’re no longer sure where to go. You can’t find this place on a map, because it’s the inside of your head.

The train is late again. You check your watch in the dim glow of the neon signs and realize with dread that your fingers have lost their feeling while clutching your umbrella. You decide then that it would’ve been better to walk. But as the air warps beneath your nose, your memories begin to flicker. It seems as if time has finally caught up. And you can’t help but think of that place. You smile as your eyes drift shut and when you awake you are standing in a lustrous city square. You are eight years old again, and you feel as if the air has been sucked from your lungs.

| The Market Square |

The warm summer air is laced with the strange, yet pleasant scent of molten sugar and fresh seafood that seems to pool on your tongue, only to melt within seconds. The white boats and their even whiter sails which line the harbor resemble soldiers crowding around an evening campfire. The restless waves crash gently against their metal hulls, creating a lull similar to that of a subway line. Market Square is Finland’s equivalent to Central Park. The towering white arches of the Presidential Palace and Helsinki City Hall overlook the harbor where the HSL line departs to Suomenlinna across the Baltic Sea. I remember the Market Square. It’s located near the eastern end of Esplanadi, and Katajanokka and it’s one of the most prominent locations for tourists and hungry seagulls in Helsinki.

It’s morning in the square, and the trolley rattles by as the church rings nine o’clock and drops off several people, who instantly bustle away across the cement, clacking their polished black shoes against the brick streets. As women begin flocking the nearest fruit stands, men stand by talking on their cellphones, drinking steaming cups of coffee, or listening with rapt attention as the nearby pigeon and seagull have their morning debate about the weather.

My older sister and I clutch small paper bags brimming with sweets to our chests as my mom’s cousin, Johanna, takes us by our hands and guides us under metal awnings and across trolley ties that run the length of the shaded roads. We stop frequently to stick

68.

our noses against the polished windows to admire the Marimekko dresses, but I quickly feel myself fall behind. The air around me is so unlike home that it makes me dizzy.

| Juvenescence |

My grandmother, Tuula Itkonen, was born in Helsinki, Finland on December 2nd, 1935. She grew up with her three siblings during WWII, something that she brings up often during quiet conversations. One story she tells a lot is that on her and her twin sister’s birthdays, their mother would make them birthday cupcakes using rye flour rations.

She tells other stories too though. About how the children back then were afraid of being spotted by enemy planes while walking to school, or how she and her siblings would stay awake listening to the sound of bombs falling all around them.

| Remembrance |