be Iris: Art + Lit the student magazine of St. Paul Academy and Summit School Vol. 8, May 2024

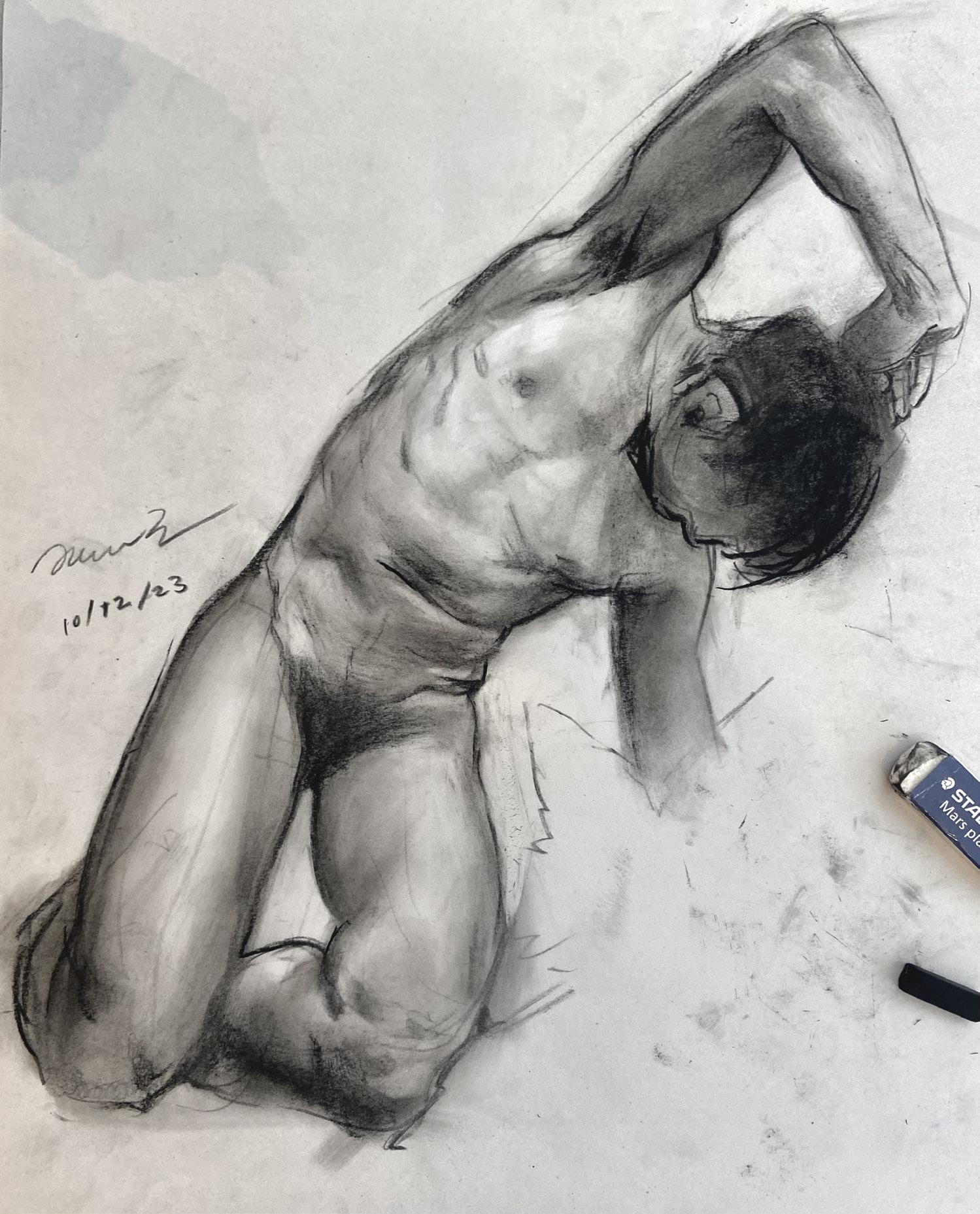

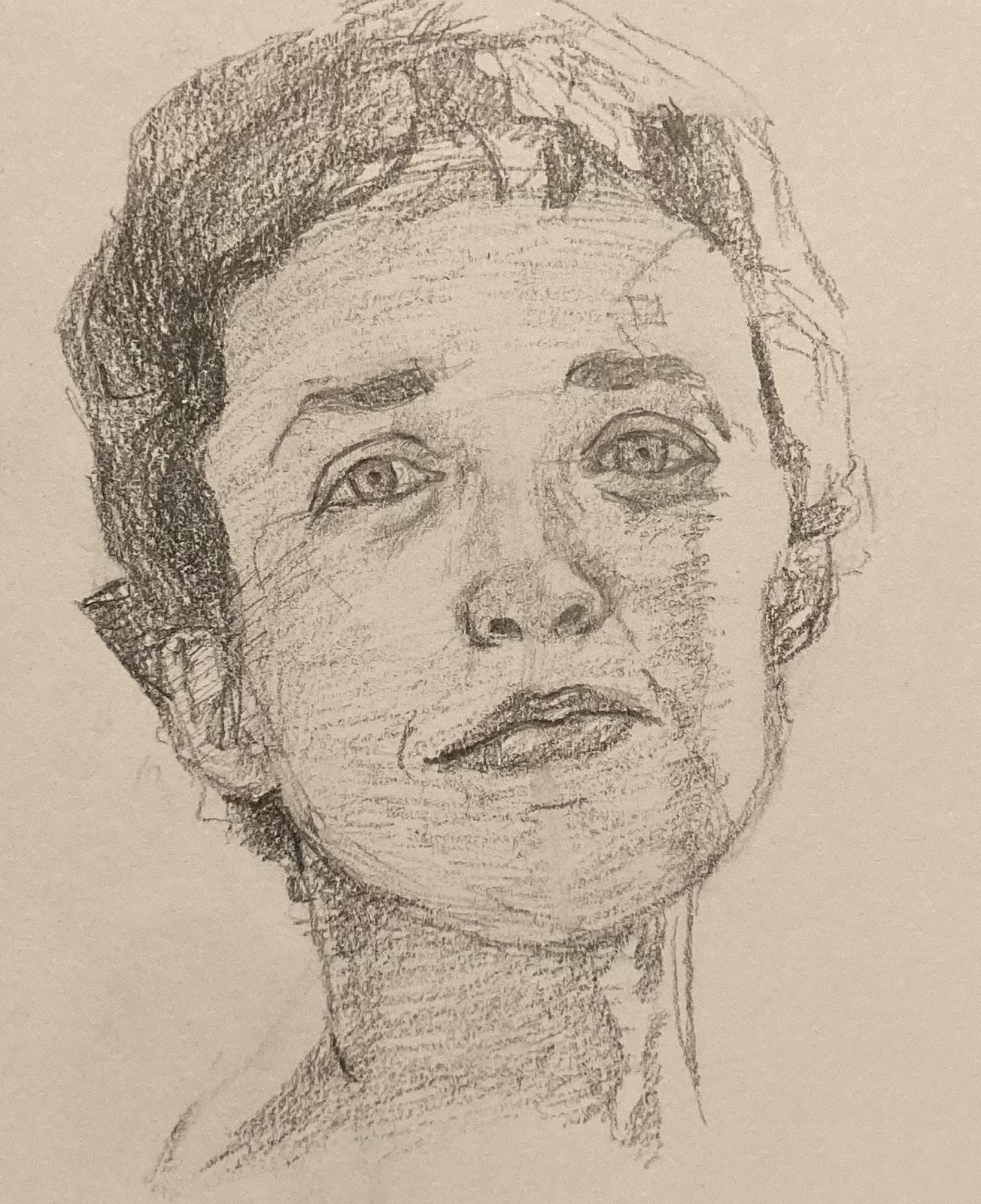

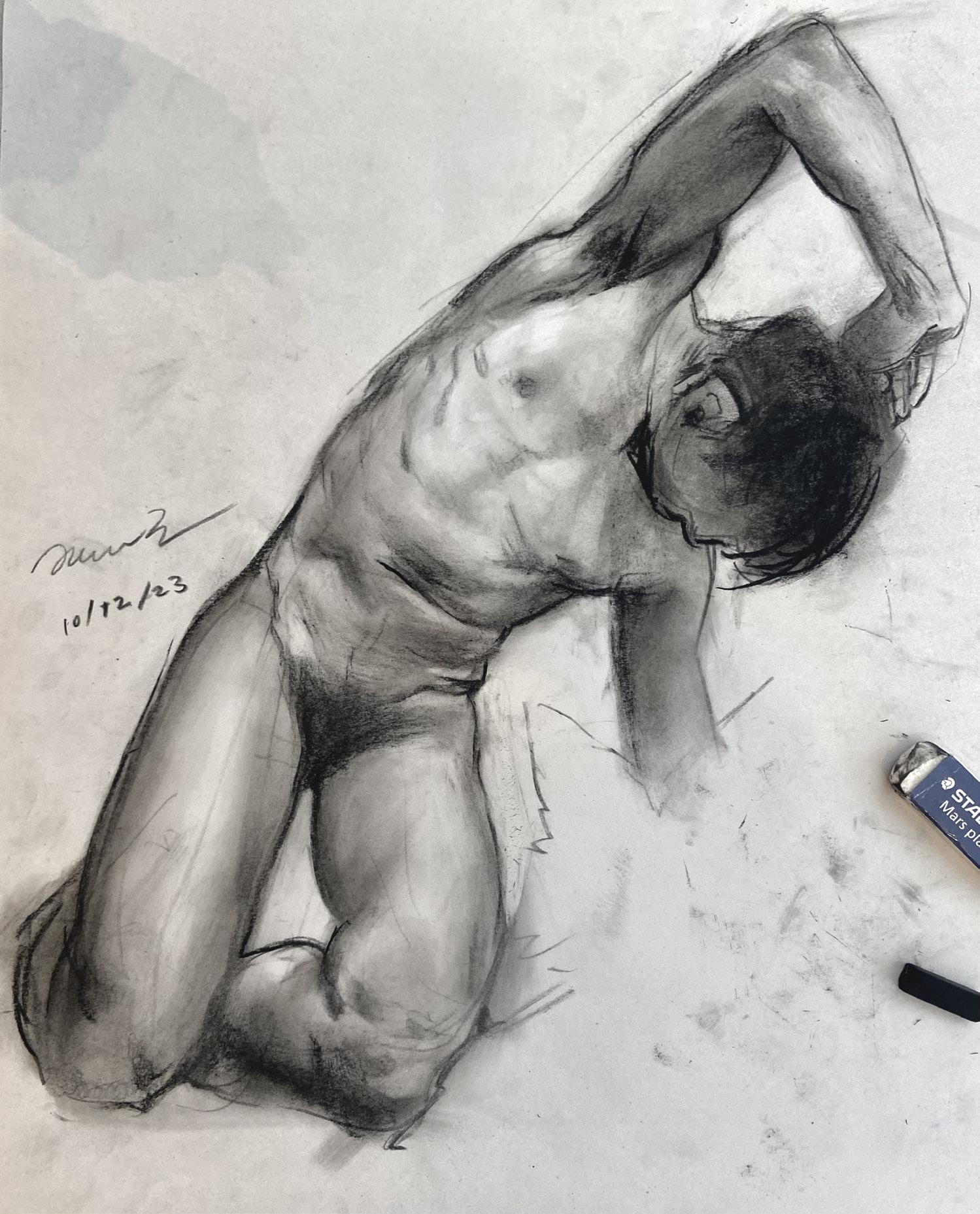

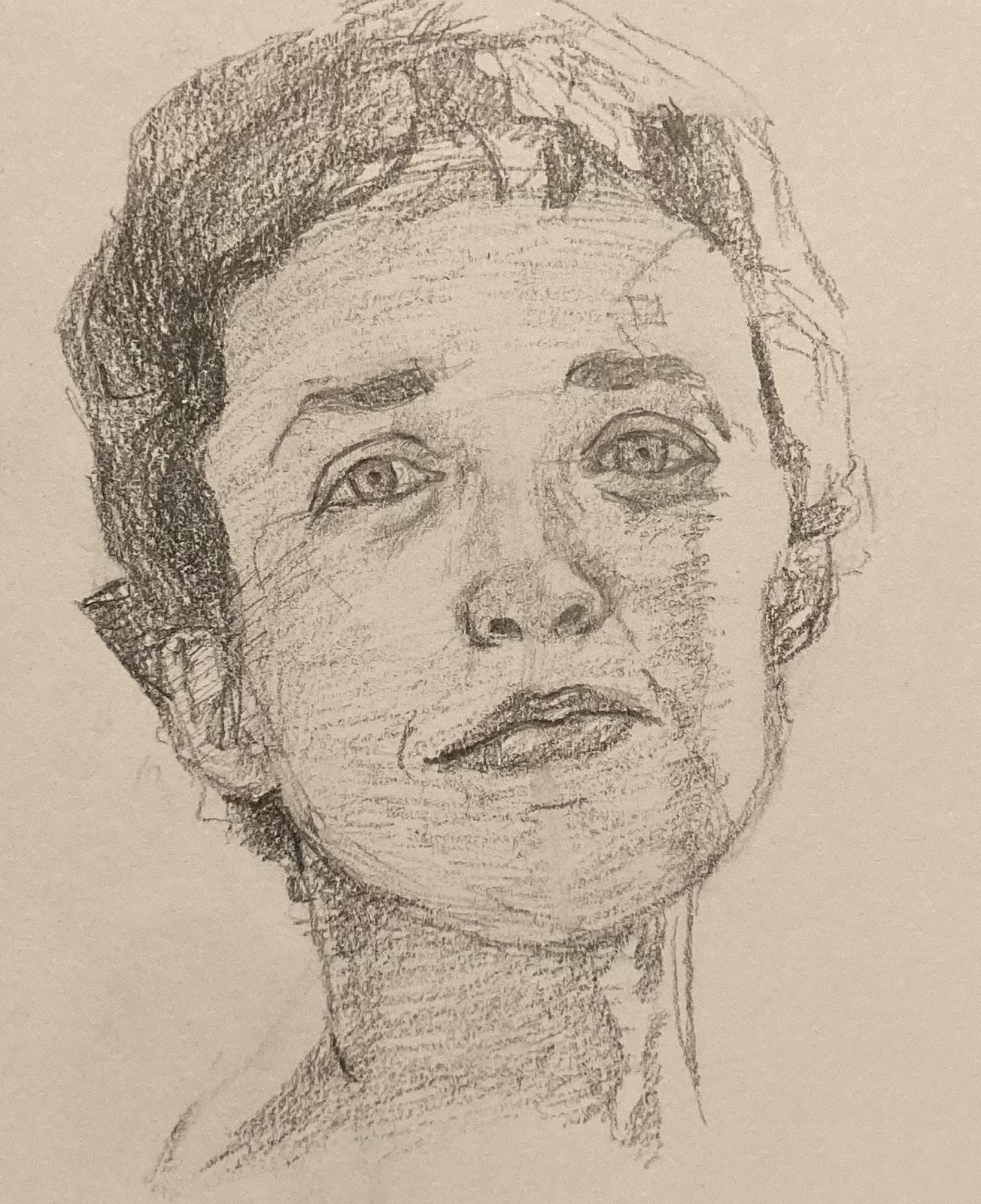

Title / Franny Wagner (__x__”) pencil sketch

St. Paul Academy and Summit School 1712 Randolph Avenue Saint Paul, MN

Phone: 651.696.1459

Email: irisartlit.spa@gmail.com

Website: irisartlitspa.wixsite.com/litmag @irisartlit.spa on Instagram

/ 001 / be Iris: Art + Lit Vol. VIII May 2024

55105

to be

/ 002 /

is to

be unafraid to stand out.

/ 003 /

The Fallacy of Fortune Telling On The Field

Family Isn’t Forever (that’s why it means so much) Day in the Life of a Dog

The Progression

They Fall Afterwarwds

Pando

Celestial Vanity

The Starlings Camera

Pieces of Migration

Elaina Elliots

My gnarly legs twist

Cordyceps Journal

Fragile Beauty

The Downpour

Instructions for Driving

A Loss

Senior Speech

How to overcome art block with Oliver Zhu

wha is left?

photography, videography

Audrey Leatham

Ivy Evans

Eliza Farley

Rowan McLean

Jacob Colton

Rowan McLean

Eleanor Putaski

Sofia Rivera

Eleanor Putaski

Sandro Fusco

Liza Thomas

Eliza Farley

Sam Hilton

Humza Jameel

Chloe Kovarik

Oliver Conrod-Wovcha

Annika Lillegard

Nora Shaughnessy

Sofia Rivera

Aarushi Bahadur

Lucy Thomas

Audrey Senaratna

Zadie Martin

Eliza Farley

The city’s

Under the Shadow of His Eyes

The Sun Hits

Claire Kim

Hadley Dobish

Hadley Dobish

Lucy Shaffer

Zimo Xie

Nora Shaughnessy

Carys Hardy

Taryn Karasti

67

essay,

journalism 7 8 14 21 23 36 41 42 45 46 50 53 55 56 60 68 72 81 82 86 88 90 94 98 she stands tall Tea

poetry,

literature,

at

end

day,

the

of the

58 61 64 66 78 80 84 87 cross north the rush Kado no Mise

after hours Fragile Beauty

/ 004 /

painting, drawing, collage

Jump!

Stuffed Love

Metaphorical Self Portrait

La tante, c’est moi

Midnight Daydream

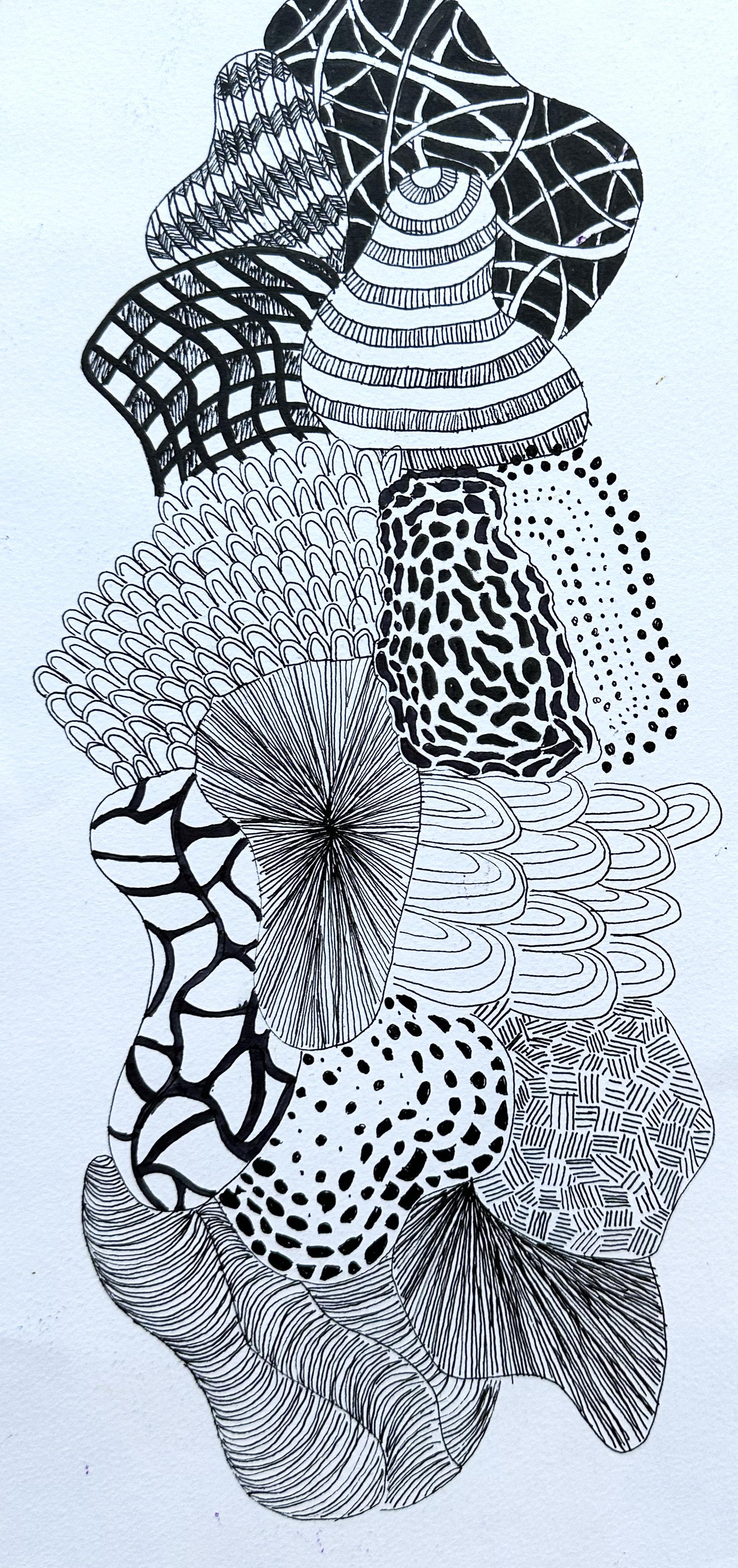

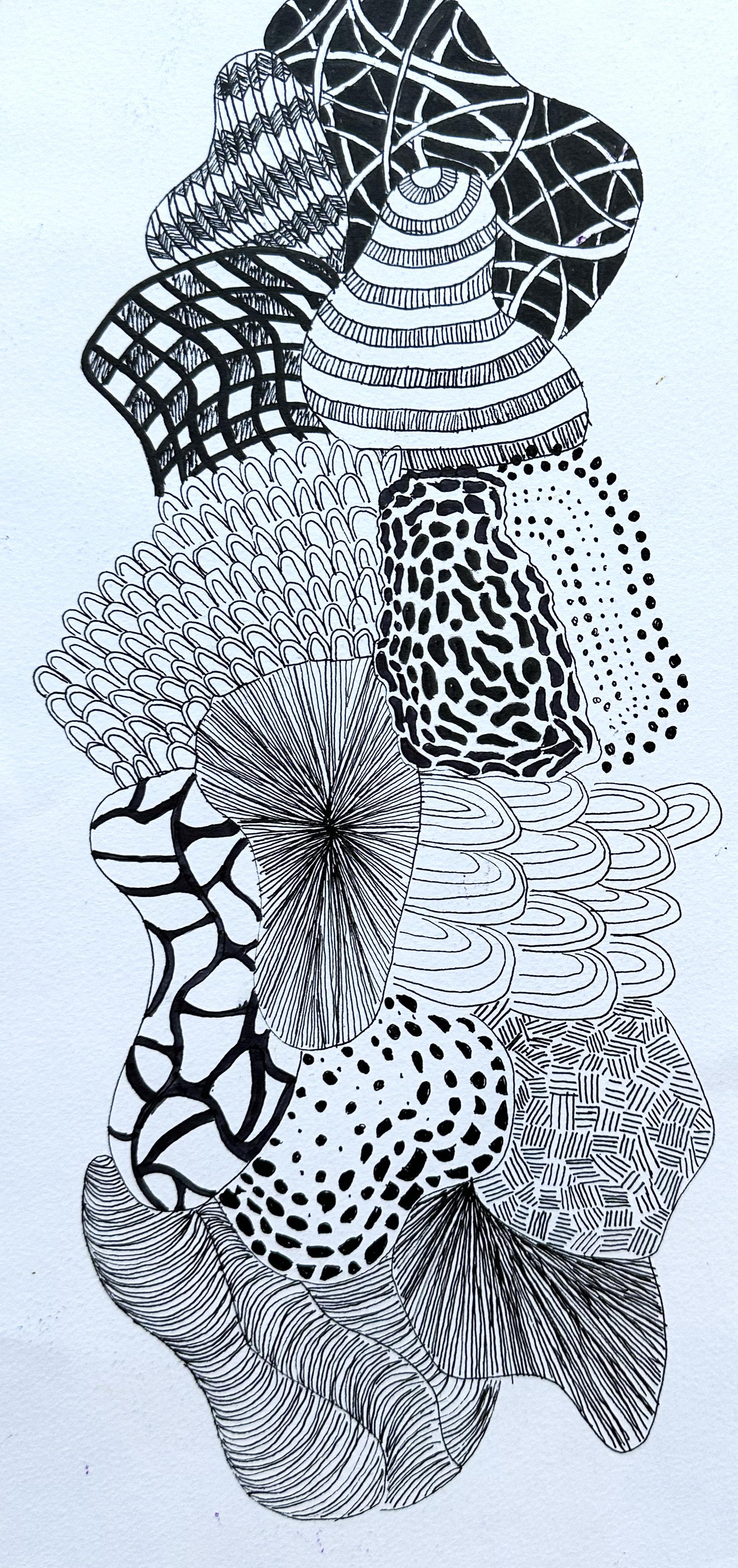

Doodle

Turkish Lanterns

Strength Growing Pains

Untitled Birds

Spiraling Hills

Window to my Imagination

Examining Death

Landscape

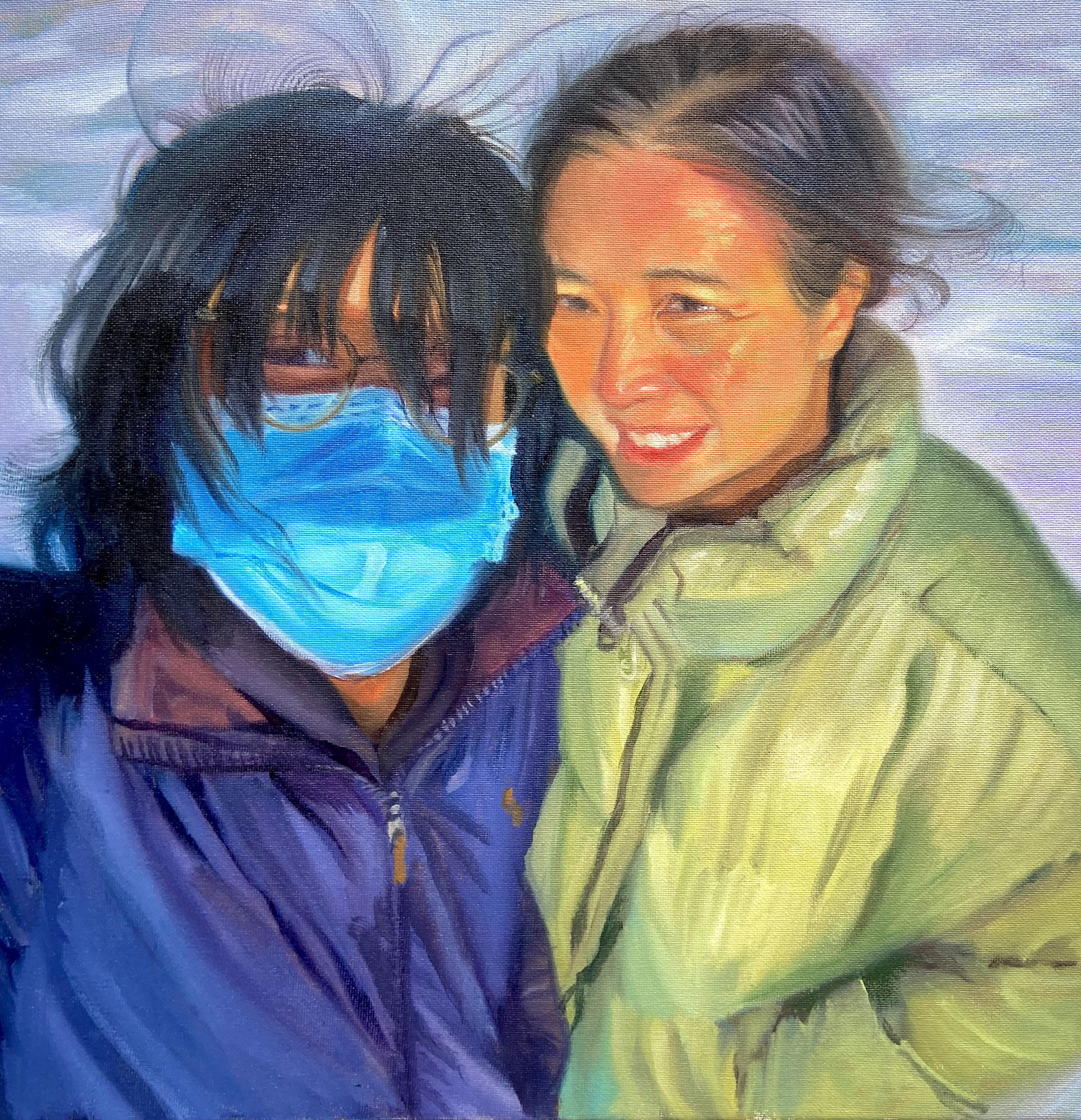

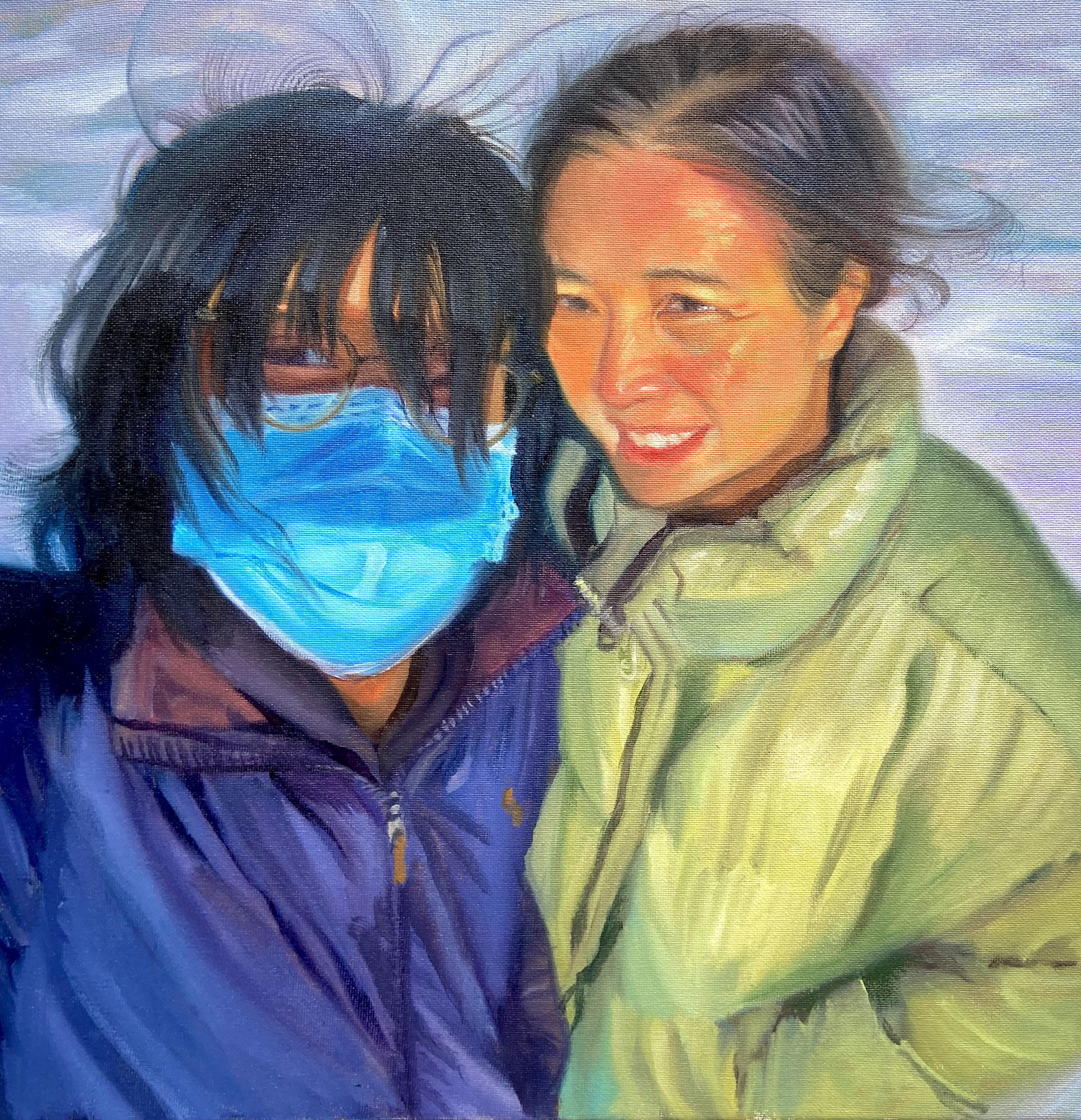

Azure Clouds Winter hike

Tisiphone

Untitled

Stumpy

Big Wave Teapot Net

A Trapped World

Purple Haze Vases

Outward Looking In

Violet Benson

Caden Deardurff

Ann Li

Franny Wagner

Annika Kim

Sophie Nguyen

Nabeeha Qadri

Dalia Wolkoff

Jane Higgins

June Dalton

Anisa Deo

Duncan Lang

Nabeeha Qadri

Bri Rucker

Talia Cairns

Avital Coleman

Oliver Zhu

Oliver Zhu

Oliver Zhu

Cormac Graupman

Helen Townley

Evan Morris

Hannah Sanders

Mikkel Rawdon

Anneli Wilson

Ethan Peltier

Bora Mandic

Sofia Rivera

Emma Krienke

Georgia Ross

92 39 54

glass 9 10 13 18 30 34 51 67 73 76 99 Blue Tea

with

Bucket

ceramics, sculpture, textile,

Bird

a Wire

Teapot Forest Bowl

6 15 20 22 27 39 40 43 44 49 52 54 57 70 83 89 92 95 97 / 005 /

/ 006 /

Jump! / Violet Benson (20x28”) acrylic on canvas

by Audrey Leatham

S she stands tall

he stands tall she is not just tall, but she has a form grace that anyone could notice she radiates it

freckles, like constellations, line her cheeks the little specks map summers past they fade when the snow falls but they still remain present

she twirls strands of hair as a form of habit or nerves something we share her habits annoy me, but I am guilty of them too she can be self-serving aren’t we all at times? when I race to school her own clock ticks louder and slower than mine

in our shared existence, we do find equilibrium it is found in a delicate balance of give and take understanding and forgiveness the balance is woven into the relationship of our sisterhood

/ 007 /

Tea

by Ivy Evans

The world is dark and I’m scared. Water crashes onto rocks, far below me, too far to jump and almost too far to see. The trees rustle. I can barely hear anything over the roaring of nature.

The atmosphere feels tense, but only to me. Jae grins like he belongs here, like this is where he was meant to be his whole life.

Not with me, or Annika, or his sister, but here.

Jae was meant for the wild. It’s his natural habitat, even though he was born in the city. He’s like a wolf raised by men instead of the other way around.

He tears off his shirt, leaving only his swim trunks and that wicked grin still plastered onto his face. The wind whips through our hair, tangling it with its chilly fingers, like it’s ensuring the dark strands will never be smooth again.

“Ready?” he asks, and I shake my no.

“I don’t know if I want to do this.”

“Don’t be a wimp. We already climbed all the way up here; it’ll be fun! C’mon.”

“I don’t want to die, Jae.”

“What? We won’t.”

/ 008 /

I don’t reply. Instead I fold my arms and stare straight at him until he sighs and relents, his shoulders shrugging as the wind intensifies once again.

“Find, suit yourself. But I’m going.”

“What?” I ask, confused.

“I’m going. If you want to jump, then jump; if you don’t, don’t. But I’m not waiting for you.”

“Jae, wait-”

The water looks like the tea my mother drinks every day. I picture her stirring it gently, swirling her spoon in circles, making a great, dark whirlpool out of the warm, sweet liquid.

Great; I call the whirlpool; great, it looks, even though it’s only the size of a teacup.

Jae doesn’t resurface for ten seconds. The wind tears through my lungs so fast that I can’t breathe. Tears rush to my eyes. I grab a nearby branch for support, swallowing hard as I peer over the edge of the cliff, waiting for him to come back.

When he does, his hair blends in with the water, so I don’t see him until he climbs out and begins scaling the rock. The wind calms down a little.

At the top, he smiles like he’s satisfied with himself. The wind can’t seem to decide whether it wants to blow with all its might so that it

/ 009 /

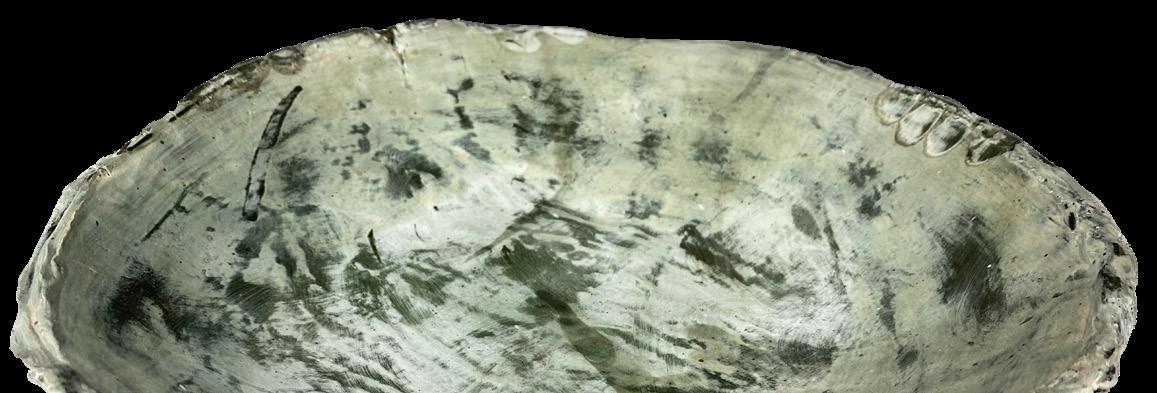

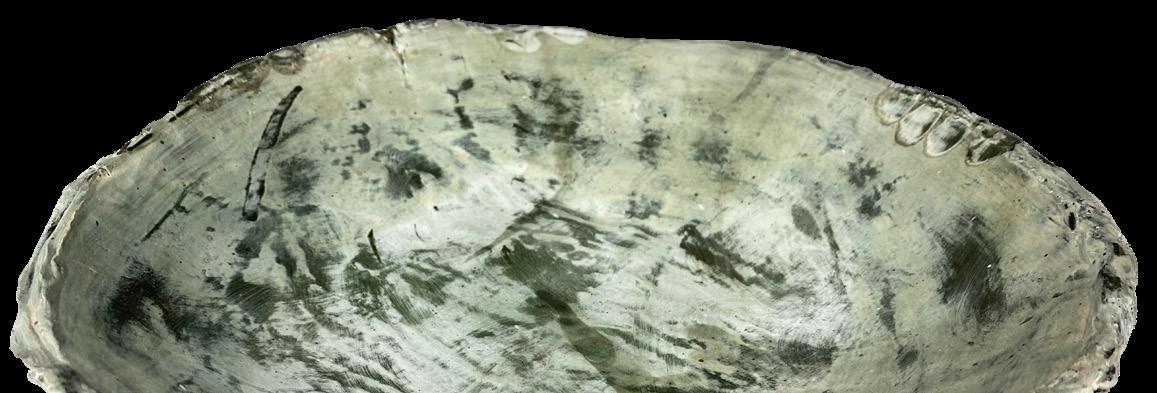

Blue Tea / Cormac Graupan (10x12x7”) ceramic work

might be noticed or step back and let the world run its course.

We go home.

Two weeks later, the world is dark again.

I watch the news on Jae’s phone. It’s quieter here than at the cliff, at least a little, and there is no wind save for a soft breeze that brushes past me like a ghost of something bigger.

I sit outside, in Central Park, and Jae sits next to me, looking over my shoulder with a sour face that he wears so often in the city. I think he likes it better where he can be free. Here,

he has to conform to society. He has to do what they tell him, or he’ll be looked down upon, even though he doesn’t want to.

He stays here for his sister, and he stays here for me, and he pretends he stays for Annika, but really he doesn’t. I feel bad for Annika sometimes. Also, guiltily, I wonder why she ever fell in love with him in the first place.

An explosion fills my screen, and the dust clears into the remnants of what used to be a bank as a reporter describes the scene from far away, eyebrows furrowed the way mine surely are on the other side of the

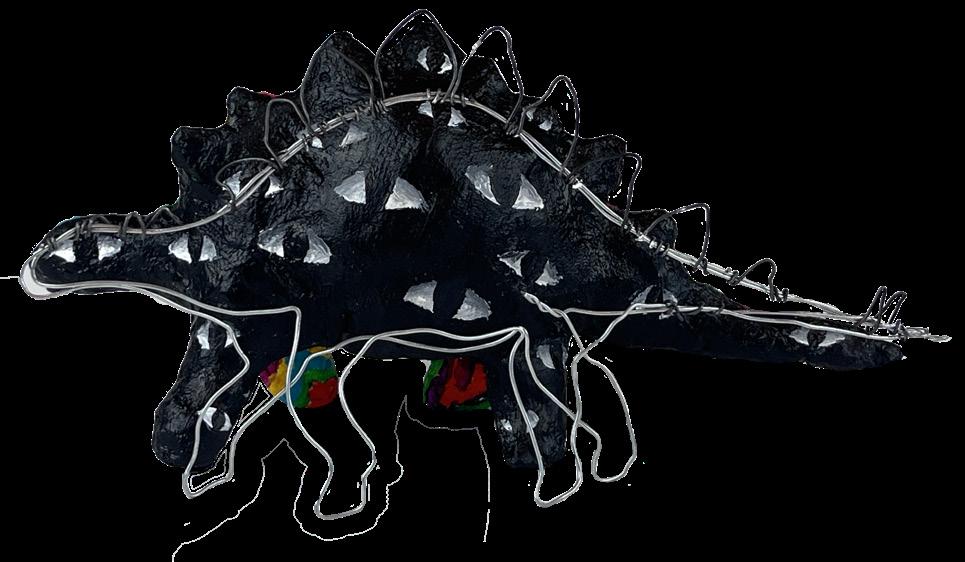

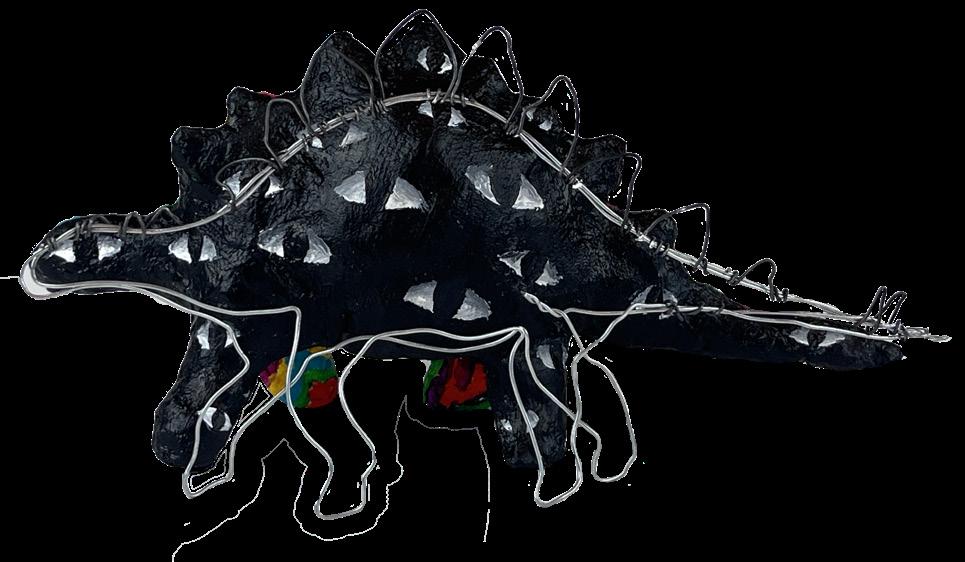

Bird with a Wire / Helen Townley sculpture /

Bird with a Wire / Helen Townley sculpture /

010 /

Buildings collapse all the time here, so they rebuild them. They make them better. Jae thinks they were fine just the way they were, and if they fall then they’ve fallen, and that’s that. He tells me so every time we hear of a new one.

I don’t know if I agree. I don’t want the buildings to fall and be gone forever, but I don’t want them to change either.

“

I didn’t want to go anymore.”

We don’t laugh, even though it feels like we’re supposed to.

There aren’t any stars, or at least none that we can see. All the new buildings covered up the starlight with their own.

Once, Jae climbed to the top of one of those construction sites. I thought he would fall off of the building and die. But he didn’t. He went up there and waved at me from the crane lift and climbed back down the building like nothing ever happened.

“Remember when we went to Paris, on the airplane? For that school trip a few years ago?” Jae asks, turning away from the screen and looking up at the black sky. There aren’t any stars, or at least none that we can see. All the new buildings covered up the starlight with their own.

“Yeah, why?”

“You said you always wanted to go on an airplane.”

“Yeah. Then you told me all about how many people had died on them.

Sometimes I wish I was more like Jae. A risk-taker; someone who loves the adrenaline that comes with danger; the thrill that comes with adventure. But life is so short already, and there are so many people who have to face scary things every day without a choice.

I’m not sure taking risks like Jae does is worth dying in the way I’m always scared he will. Jae stands up, and we go home.

Three days later, the world is dull - not dark or light, just something muted in between. Jae’s eyes are red, and tear stains are drying on his cheeks.

“We can’t predict anything,” he murmurs, staring at the ceiling from where we rest on the carpet, his voice barely audible over the hum of the fan in my room. We lay together, looking up, watching it spin.

It’s so routine; so normal. The air it blows down on me is too cold, and part of me wants to reach out and stop it from moving so I can be comfortable / 011 /

screen.

again. But I know if I interfered with its rotation it would end up much worse than doing nothing ever would.

“Yeah. Life’s kinda scary like that, isn’t it?”

Jae misses his sister. She’s in the hospital, and he’s scared she won’t make it out. We both are.

“Yeah.” He sounds like he’s going to start crying again. I look over at him, and sure enough, his eyes are damp. He looks away from me.

“I just- I keep hoping she’ll come back, but what if she doesn’t? Won’t hoping only make it hurt more? If she doesn’t make it out, won’t I regret how long I spent waiting for something that was never going to happen?”

“It’s okay, Jae.”

“

Change will always come, whether I like it or not. It’s an inevitability that comes with living. But that doesn’t stop me from hating it, because I know that Jae will never be the same, not after this, not without his sister. And that means that we will never be the same.

He used to love the unpredictable; all the things he couldn’t foresee. Now he hates it. We both hate it.

“It’s not.” He inhales sharply, like he’s holding back a sob. “I put myself in all these dangerous situations, just for the thrill of it, and then something dangerous actually happens to someone else and suddenly everything changes. And it feels like I shouldn’t have taken all those risks because she doesn’t get that luxury. Her life is on the line because of something she didn’t choose.”

For once in all the time I’ve known him, I don’t know what to say.

He goes home.

Our building has fallen, and it will be rebuilt with walls in places where there were never walls before.

Jae takes risks; he belongs in the wild. I belong in captivity, where I’ve always been. I do what I’m used to. I stay safe.

I relish the quiet; he lives for noise.

He has more fun in the dark; I feel safer in the light.

I find peace in routine. He used to love the unpredictable; all the things he couldn’t foresee. Now he hates it. We both hate it.

Entropy is beautiful until it kills.

But he’s still angry, and I’m still kind.

He still loves the ocean at night, and I still love the sky.

He still wants to live, and I still don’t want to die.

/

I

012 /

/ 013 /

Bucket / Evan Morris

(10x11x11”) ceramic work

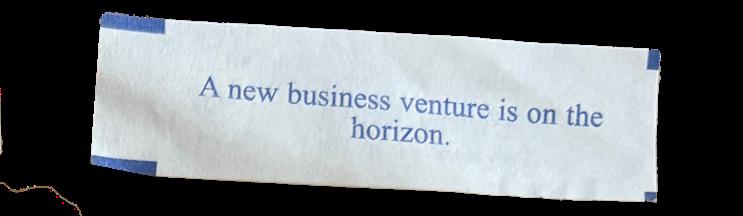

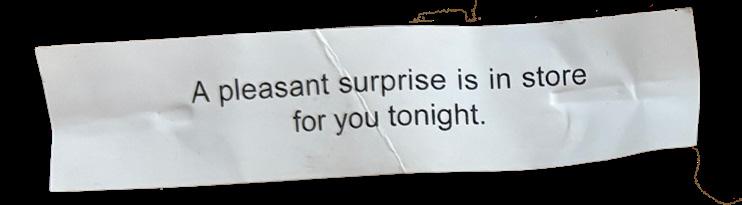

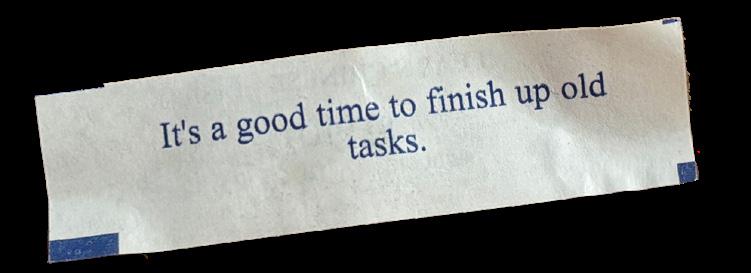

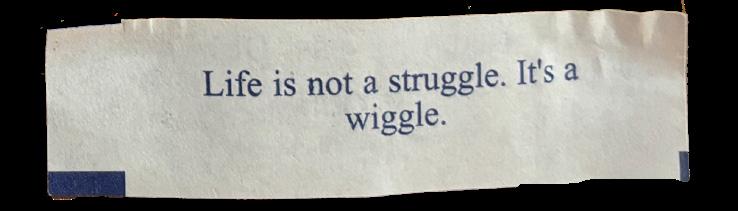

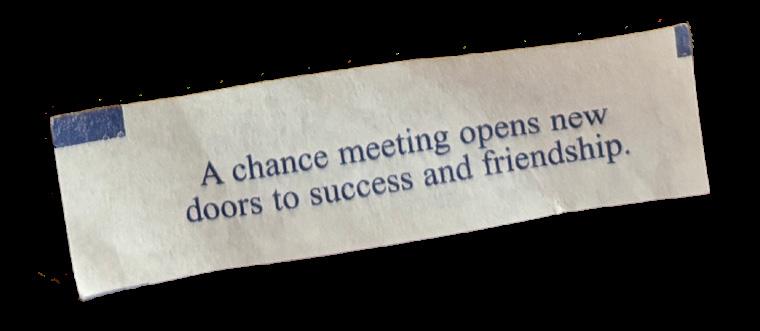

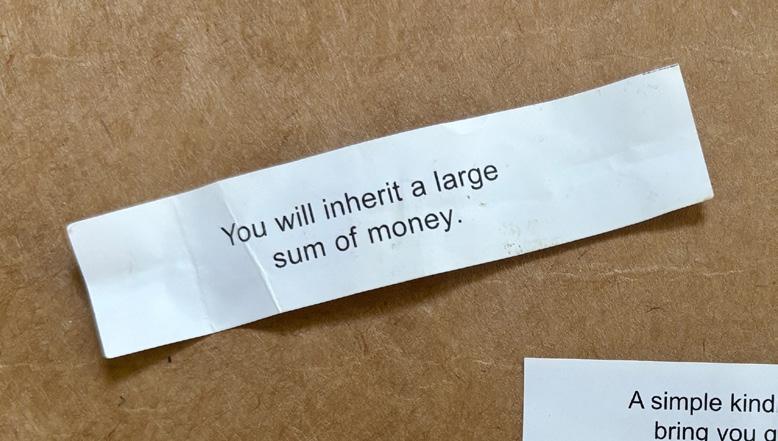

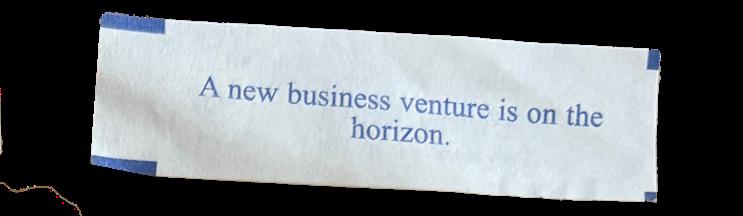

The Fallacy of Fortune Telling

by Eliza Farley

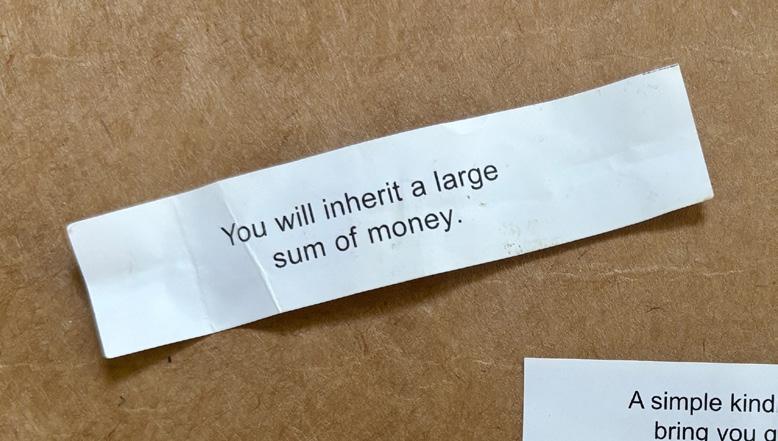

Icollect fortune cookie fortunes. I don’t remember exactly why. And yet, at every school lunch, I keep my eyes peeled for those little folded cookies. I always snatch one or two if I can find them. (I don’t usually eat them; I’ve never loved the taste. Instead, like it’s a game of Operation or something, I surgically extract the paper and slide the broken cookie halves onto my friends’ plates.) By this point in my collecting ca reer, my friends usually hand me their fortunes without me even having to ask. I carry the small paper strips in my pocket throughout the day. When my darlings finally arrive home with me, I stuff them into my overflowing cinnamon Altoids tin, chock-full of such wisdoms as “A simple kindness today will bring you great reward” and “You will inherit a large sum of money.” I’m happy, now, at this moment.

I think I love fortunes so much be-

cause they lay out a concrete future. They leave no room for doubt. For someone like me, who loves certainty more than anything, they’re a lifeline. To secure that sense of certainty that I love so much, I usually try to prepare for every scenario. I’ve always prided myself on my organizational skills; I live by the phrase “a place for everything and everything in its place.” I’ve cultivated an eye for detail that comes in handy almost every day. Perhaps even too handy—for instance, a few years ago, I started noticing the uneven placement of my books on my bookshelf. Not all of them were at the same depth, and they all came up to different heights. So, I started using a ruler to straighten them out, and arranged them by height and genre, and it gave me such a thrill! I remember once during online school that a teacher told me my bookshelf was the neatest they’d seen in a while. I looked back at my bookshelf full of

/ 014 /

/ 015 /

Stuffed Love / Caden Deardurff

(20x14.25”) dry pastel on paper

carefully aligned rows and columns— mathematical perfection—that could only result from the machinations of a truly diseased, sickened mind, and the next twenty months I spent in a cheerful glow. Now, like any good addict, I can’t be stopped without a serious intervention. After all, to organize and prepare is akin to writing myself a fortune: “You will be ready for what lies ahead.” And I love to feel ready.

So often, though, it doesn’t matter how much I prepare — something will come out of left field and leave my plan in tatters. (Not even my fortunes are immune. My brother, who was fourteen at the time — fourteen entire years old — decided that a couple slips of paper would make a delicious snack. I don’t know if he was nutrient-deficient or what, but I was left deeply confused and heartbroken.) It feels personal when the things I’ve set up so carefully fall apart—mostly because more often than not, it’s literally my own fault. If there’s anything I love more than preparing, it’s making poor decisions that undo all my preparation. It’s a cruel trick that there is nothing better in this lifetime than a 4 to 8 p.m. nap,

“

In other words: I’m not a fortune cookie; I’m a person, someone with free will.

because unfortunately, frontloading all your sleep and then staying up until the wee hours will lead to waking up in your clothes more often than not. It also usually means that my plans, which depend on me making smart decisions, kind of crumble into little pieces. It can feel like I not only failed, but that I myself am a failure — that, if I were a cookie, my mistake would be set in my fortune’s black ink. “If I had just tried a little harder,” I’ll say to myself in those moments, “I would have been able to foresee that problem and work around it.”

That perfectionistic way of thinking — really, that way of life — is frustrating to deal with and hard to shake completely. I’ve spent years trying to loosen up, accept that not everything can be prepared for, and move forward. Even so, that mindset can still come back at the worst moments.

However, I think that one of my fortunes, brought to me by random chance, sums up the approach that I hope to internalize: “Pick another fortune cookie.”

In other words: I’m not a fortune cookie; I’m a person, someone with

/

016 /

free will (hypothetically) who gets to choose which future to pursue. I don’t have to be tied to these habits I’ve spent all my life perpetuating. It’s possible to crack open the cookie I’ve been handed, look its prediction in the eye, and discard it. It’s possible to “pick another fortune cookie” and change the way I live—today, if I want. And sure, programming those changes will take time. It’s a double-edged sword that we’re creatures of habit, and that it takes so long to break out of the routines we’ve built for ourselves. But it’s possible. My life will change, for better or for worse, based on the habits I choose to keep around. It’s impossible for me to know exactly what will and won’t serve me in the future, but if I try hard enough, I can start to forget how to fall asleep in the middle of the afternoon. Even when I make mistakes, I can move forward in a pattern that will bring me to a better place.

I’ve basked in the sun until I’ve burned. I’ve scratched mosquito bites until they’ve bled. I’ve doused my greased-up shirts in Dawn, and I’ve covered up more popped pimples than I care to count. I carry the marks of a life unpredicted, filled with bad decisions and worse cover-ups. I could never put everything worth knowing on a strip of paper. I wouldn’t even want to try.

I

/ 017 /

/ 018 /

Teapot / Hannah Sanders (9x12x10”) ceramic work

/ 019 /

/ 020 / Metaphorical Self Portrait / Ann Li

(11x14”) watercolor on paper

On The Field

by Rowan McLean

On the grassy field where the action sparks, Soccer vibes, kicking around at the parks.

Feet move, the ball hits the ground with a beat, Players talk, through all the noise on the street.

Goalposts standing, tall and proud, Keeper dives, the crowd goes loud. Defense hustles, planning the chase, Game’s a dance, in every space.

In the stands, cheers and roars, Goals hit hard, the crowd is wild. Soccer’s a jam, where skills aren’t mild, Ninety minutes, a groove so fine. This sport doesn’t disappoint. It plays just fine.

/ 021 /

/ 022 /

La tante, c’est moi / Franny Wagner (6x4”) pencil sketch

Family Isn’t Forever

(that’s why it means so much)

by Jacob Colton

My mom dropped her parents off and watched them walk away, the image only slightly blurred from a foggy lens over her eyes, unlike her dad, who looked like he had just pulled through a car wash as he blew his nose and waved one more time before sorrowfully walking out of sight; my mom drove away, not to her condo, or to her soon-to-be apartment, or to go eat, or to anywhere, really, she just drove around and around, first to downtown Saint Paul and then to Woodbury, before returning back to the airport, and then repeating the circle again and again and again, unable to believe that she was alone, all by herself in the U.S, and it felt to her as if the sun was beaming straight down through the car roof, even though it was an overcast June day.

---------------------------

“It’s like comparing an apple with an orange,” Lolo’s voice from the other side of the world comes through the phone, “as you probably have experienced, or remember experiencing when you were in Manila, is that Filipino people are extremely friendly people. They are

even for complete strangers. That’s why a foreigner feels very much at home here.” I nod, as my wifi connection to him glitches out for an instant before the FaceTime resumes, “But the predominant thing that I like in Minnesota is the efficiency of the system, you know, and the cleanliness of the system,” Lolo, grandfather, resumes, as I rub my eyes and yawn, and he does the same, for the opposite reason.

Lolo was the first to establish a connection to Minnesota, as a young lawyer, when he got a job at 3M, and then what started as infrequent visits to Minnesota as part of his work led to an entire generation of immigrants: “My boss was a lady, Rosa. Rosa Mila. She had some connections to the hospitals in St. Paul,” Lolo’s halting, indescribable, yet immediately noticeable Filipino accent emanates from my phone, “And therefore she said that she would see what she could do for your mom to get her to be resident physician at… was that the Children’s Hospital? I understand that it’s closed now.” I nod offhandedly, and there is a lull in the discussion.

“Ah! I got the word now,” Lolo’s

/ 023 /

deliberately placed syllables lilt through the screen, “the civic orientation is very weak, in the Philippines — in Minnesota there is a strong civic consciousness of cleanliness, or be encouraging to strangers for instance, or by obeying rules and regulations. There’s a time to throw out your garbage and the time for the sanitation team to pick it up. In the Philippines, there’s no such efficiency.”

“Minnesota in winter… the winter in Minnesota, it’s too cold,” he laughs, nasally, and I laugh too.

I make sure to thank him for his time, and he hears my mom in the background: “Can I talk to your mom?”

I hear the language shift to a hybrid mix, half Tagalog half English, and the two talk while I do my homework, while I eat breakfast, and while I read a book...

He asks how my school is going, and after I let him know that it’s going well, he asks if it’s a Catholic school — “Um, I- Uh, I’m not sure…” I respond unconvincingly. Catholicism is omnipresent in the Philippines, with Catholics representing 7,340,458 of the 7,834,028 that live in Manila. We’ve used ‘Saint Paul’ as an excuse for a while now, but it’s a tenuous excuse, so I quickly hurry on the discussion: “You seemed to really like Minnesota.”

“Yes. But in Minnesota, and of course, for any other country, if you stay there long enough, you will discover some of the things that you won’t like, you know. Like obviously,

/ 024 /

“Yeah, yeah, she’s right here.” I hand over the phone to my mom and I hear the language shift to a hybrid mix, half Tagalog half English, and the two talk while I do my homework, while I eat breakfast, and while I read a book, on and on for what feels like an eternity, yet not one minute of their time feels wasted.

As a 23-year-old, my mom would get home from school sweating from the Philippine heat, even though the sun had long since been consumed by endless lines of traffic, and as she would walk into the house her grandparents had owned, and her parents owned, and she thought she would own someday, she would ask a housekeeper for a glass of water. She would turn the radio on to Duran Duran, trying to avoid the sounds of the NBA game her 9-year-old brother was watching. Maybe she would turn on Voltes 5, a

show she would watch as a kid, to get a touch of her dad’s sentimental side.

My mom enjoyed Filipino arts as well, but as her brother JC puts it, growing up, “the U.S. culture was very elevated,” or, as celebrated Filipino writer Doreen Fernandez puts it, “Before most Filipinos become aware of Filipino literature, song, dance, history (thanks to the scholars and artists), education, language, and the media have already made them alert to American life and culture and its desirability. They sing of White Christmases and of Manhattan. Their stereos reverberate with the American Top 40. In their minds sparkle images of Dynasty, Miami Vice, and L.A. Law. They embrace the American dream” (Fernandez 492).

---------------------------

My mom initially immigrated to the U.S. for her medical residency. This pathway to immigration is fairly common for Filipinos, as the Philippines sends proportionally more professional workers than other countries — in 1970, for example, “the percentage of professional workers among all immigrants was 11.27%, while for the Philippines it was 29.7%” (Keely 184).

She started residency as soon as she arrived, managing the whirlwind of learning how to be a doctor all while she still didn’t know what a loon was.

“It just felt very busy,” my mom relays during my haphazard interview

with her. The 20-year-old leather chair she sits on is gnarled with creases and scratches from years of use. “I didn’t really have time to reflect. I mean… we hit the ground running, you know? You have to do hospital service, you have to be on call, you’re seeing your patients in your clinic with your attendance. Just a lot to get used to in a short amount of time.”

I question her about how it was trying to get used to a new country during the chaos of residency, but she mentions it only in passing, “it’s a little bit intimidating. Because you know, I was not in my own country,” before going back to reliving the stress of residency: “Also, there was a whole system of hospitals and clinics to get used to learning, learning how to work the electronic medical records… Yeah, it was a very busy time.”

My mom goes back to work on the computer for a bit as I think of my next question; the sun disappeared a while ago, and she has notes to prepare from clinic that will take her well into the night, yet she somehow made time for an interview with me, as she always does.

“So where were you living during your residency?”

“Oh, so when I got accepted to residency I found an apartment in downtown St. Paul. And my residency slash work was in a small clinic near the Capitol, and the hospital I worked in was St. Joseph’s in downtown St. / 025 /

Paul,” my mom responds as our house clock adds a fourth digit to the time.

“And how old were you?”

“Well, let’s see. I’m 52 now, and I started residency in 1999, so I would have been… 28? Yeah, that sounds right.”

Even as a 28-year-old, the experience of independence was completely new to my mom. In the Phillippines, because there is a lot of poverty, labor is very inexpensive, so growing up my mom had someone to wash her dishes, make her bed, do the laundry, drive her around, etc. When my mom immigrated, she had to learn how to do that all herself, on top of getting used to a new country, on top of dealing with medical residency.

“Were you able to connect to any Philippine community here that helped with the shift or…?”

“Yes. So there is a moderate size Filipino community — ” A lot of them ended up in Minnesota through a similar path to my mom — “And in fact, there’s a Filipino society here. So I did get to know a lot of them and I still am in touch and continue to get to know them,” my mom explains. Just this past September she brought my brother and me to a Filipino tennis gathering.

“How much did that help with acclimating to Minnesota?”

“It helped a lot with the loneliness, I think. When I moved here, I was living alone in my apartment, so

it filled up times, weekends when I didn’t really have any work or anything to do,” my mom says, her eyes looking into her past, “But, did it help me acclimate, other than keeping me company? I’m not quite sure. I’ve always been pretty flexible, I think. So I don’t know that it would have been any different as far as adjusting to culture if I hadn’t had that support,” my mom remarks, trying to remain modest while suggesting that she didn’t have a hard time adjusting to the new country. I realized it explained why she emphasized the strain of residency rather than her struggle with immigration. “You know, the funny thing is, I don’t think I sought out my parents very much, even with the occasional loneliness. We kept in touch, with emails and the occasional phone calls, but I loved being independent. I lived with my family throughout school, including college and med school because that’s just how it usually is in the Philippines. And, it seems kind of odd to say, but by the time I got here, I really was just enjoying living independently. And so maybe because of that, I probably did not keep in touch with my family as much as I should have,” my mom recalls, her eyes inscrutable yet almost regretful, and I’m reminded of her call with Lolo when it seemed as if they were almost desperately trying to fill a gap that spanned from one end of the Pacific to the other.

/

026 /

---------------------------

“We don’t have cold weather in the Philippines. We definitely don’t have snow,” my mom confirms. She’s acclimated pretty well to the weather — she knows how to dress warm, she goes skiing, and she was even dragged onto a winter camping trip, but whenever there is even the slightest bit of ice on the ground, she still looks like a fish out of water.

“The other thing I found weird when I first moved here was how early

the restaurants closed, which is a small silly thing. But you have to understand that Manila is just busy, busy, busy. 24-hours-of-the-day busy. So you could always get food somewhere. So it was weird that kitchens closed here at, like, 9 pm,” my mom recounts with an incredulous frown. Besides Manila, my mom had only visited L.A. and New York, so Minnesota to her must have felt like a cold tundra with only a few deranged stragglers clinging on to a city that should have / 027 /

Midnight Daydream / Annika Kim (15.5x15.5”) digital art

been abandoned centuries ago. But she ended up here, partly because “Lolo really liked it here during his visits for 3M, he felt that it was a safe, quiet city compared to other cities that he’d visited before, like LA and New York.”

My mom also tells me of how she had to adjust to people’s expectations of punctuality — but I don’t need the reminder. Even as she has somewhat adjusted to the US’s standards (in the Philippines, 15 or 30 minutes late is expected, an hour or even more is tolerated), she still takes “on time” to mean within 5 minutes, even for important events. Nothing holds a candle to Lola’s, grandmother’s, extreme tardiness — I’m convinced her perception of time is on a different scale. She routinely shows up an hour to 3 hours late. She will start cooking a meal for a party at the time the party is supposed to begin. She even showed up late to my mom’s wedding. When she visits, each family member takes shifts making sure she is on track to be at least within an hour and a half.

“My first impression of Minnesota, though,” my mom continues, “wasn’t the cold or lack of activity. It was that it’s very white. If you don’t really seek it out, if you just stick to one neighborhood, the

population can be very white. In fact, all except for two other residents in my class were white.”

“Did you notice that people treated you differently?” I questioned uncertainty.

“Like were they biased?”

“Yeah”

“Maybe they were. I’m not a sensitive kind of person. I tend to not get bothered by those kinds of things. I’m not hyper-vigilant for things like that. So there might have been times when the intention was to make me feel different or make me feel inferior, but I don’t I don’t remember one particular instance where I ever felt that. I’m not saying that that didn’t happen. I just don’t notice those things sometimes.”

“

My mom also tells me of how she had to adjust to people’s expectations of punctuality — but I don’t need the reminder.

My mom relayed an instance from a tennis lesson (which she was undoubtedly late to ) when she experienced a microaggression: she was in a tennis drill with her Korean American friend, taking a lesson from an old white man, where they were playing doubles, my mom and her friend against two white men, and the coach said ‘all right ladies. Let’s take these guys to Chinatown!”

“Which, I understand, is not an appropriate thing to say,” my mom / 028 /

laughs, “but I thought it was very funny. It didn’t even occur to me to get offended.”

“During residency, my mom met my dad, and made a decision that changed her forever: she was going to stay in the U.S. She wasn’t going back after residency.

She tells me of a different instance when she was having a picnic with some of her Asian American friends, who were all different ethnicities (one was Korean American, one was Taiwanese American, one was Chinese American, one other was Filipino American, and my mom), and an older white lady came up to them, smiled, and asked if they were having a family reunion. Again, the others were all offended, but my mom didn’t have much of a reaction.

“And I think that might have something to do with having not grown up here and not being exposed to those microaggressions. I did not grow up constantly being bombarded by those kinds of comments or experiences. I grew up in a place where I was like everybody else and was valued as a person, as myself.”

During residency, my mom met my dad, and made a decision that changed her forever: she was going to stay in the U.S. She wasn’t going back after residency.

“We fell in love and got married.

I ended up staying. Which is a very good reason. I suppose it’s a very common reason for people to stay,” my mom explains.

“I do remember, when she moved to the US, that I felt kind of sad. Like ‘Okay, this is part of our family that is moving. But we weren’t very close growing up,” my mom’s brother JC says.

“It felt very sad, you know. I think most fathers would feel sad when their daughters are given away in marriage and even worse is when after getting married they migrate to a different country,” Lolo sentimentally recalls, pushing the conversation forward as if he doesn’t want to think about it. “A typical Filipino parent still feels responsible for a child even when he or she gets married. Unlike in America, where the umbilical cord is cut off after graduation or when he or she chooses practices. And the other thing that is maybe good or bad depending on how you look at it is that in the Philippines there is a very close family kinship, you know what I mean? So it was very hard seeing your mom choose to leave,” Lolo comments, every single piece of his sentimentality coming through his voice as he relives the painful moment

/ 029 /

when he realized that his time as a parent had come to an end. ---------------------------

After my mom had established herself in Minnesota, and her family realized that the U.S. brought more opportunities than the Philippines did, they decided to immigrate to join my mom. Lola was somehow able to obtain green cards for three of them: my mom’s brother JC, Lolo, and herself. But the immigration

process was “long and arduous,” as JC describes it in my FaceTime with him.

“I remember my parents and I, we would line up outside the US Embassy in Manila. And we would be in line for five hours, six hours at a time. Then the line would inch closer and closer to the embassy entrance. Finally, we could take care of some tasks, whether it was a background check or signing paperwork, a physical exam or a medical exam. We had to do that for

/ 030 /

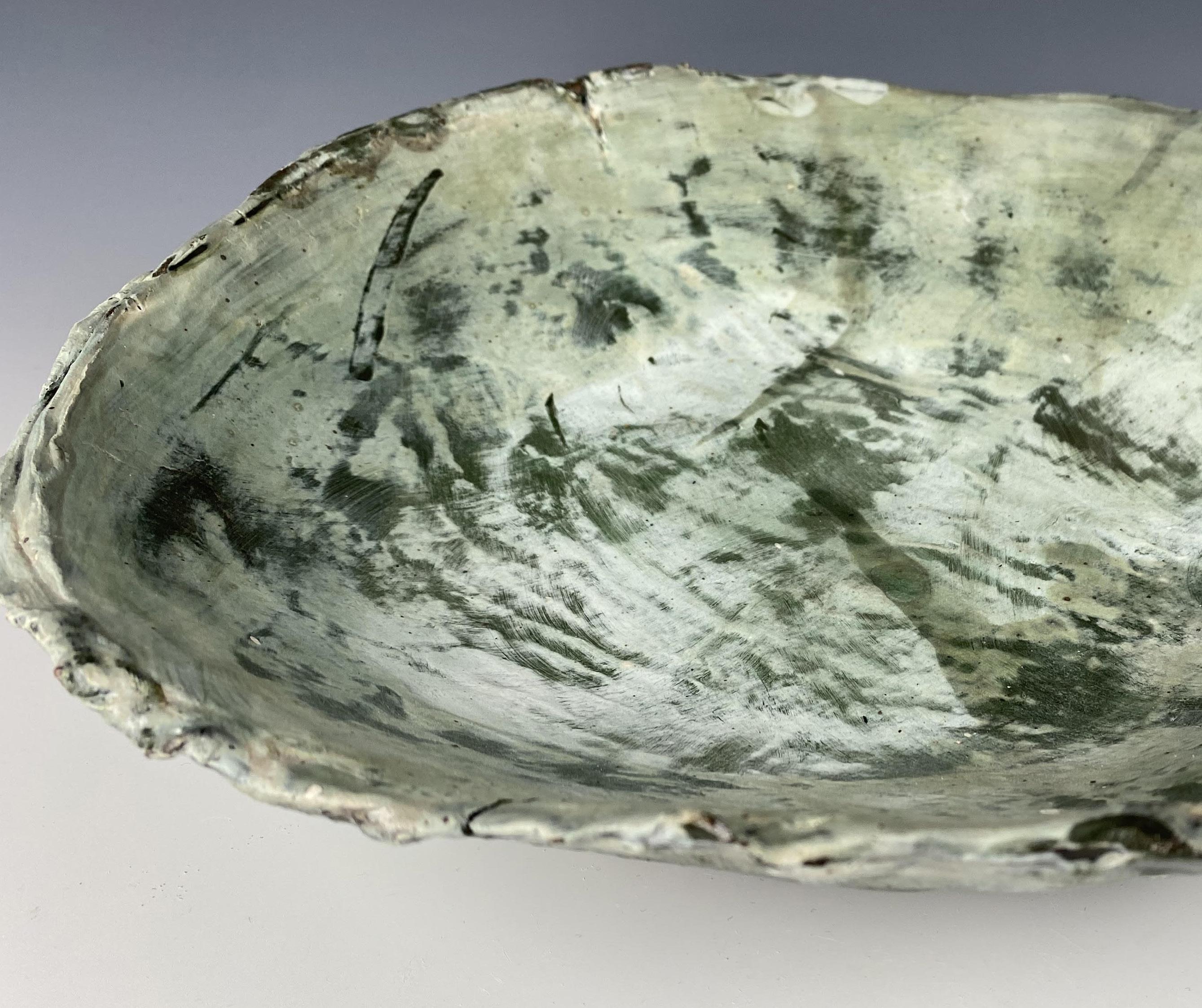

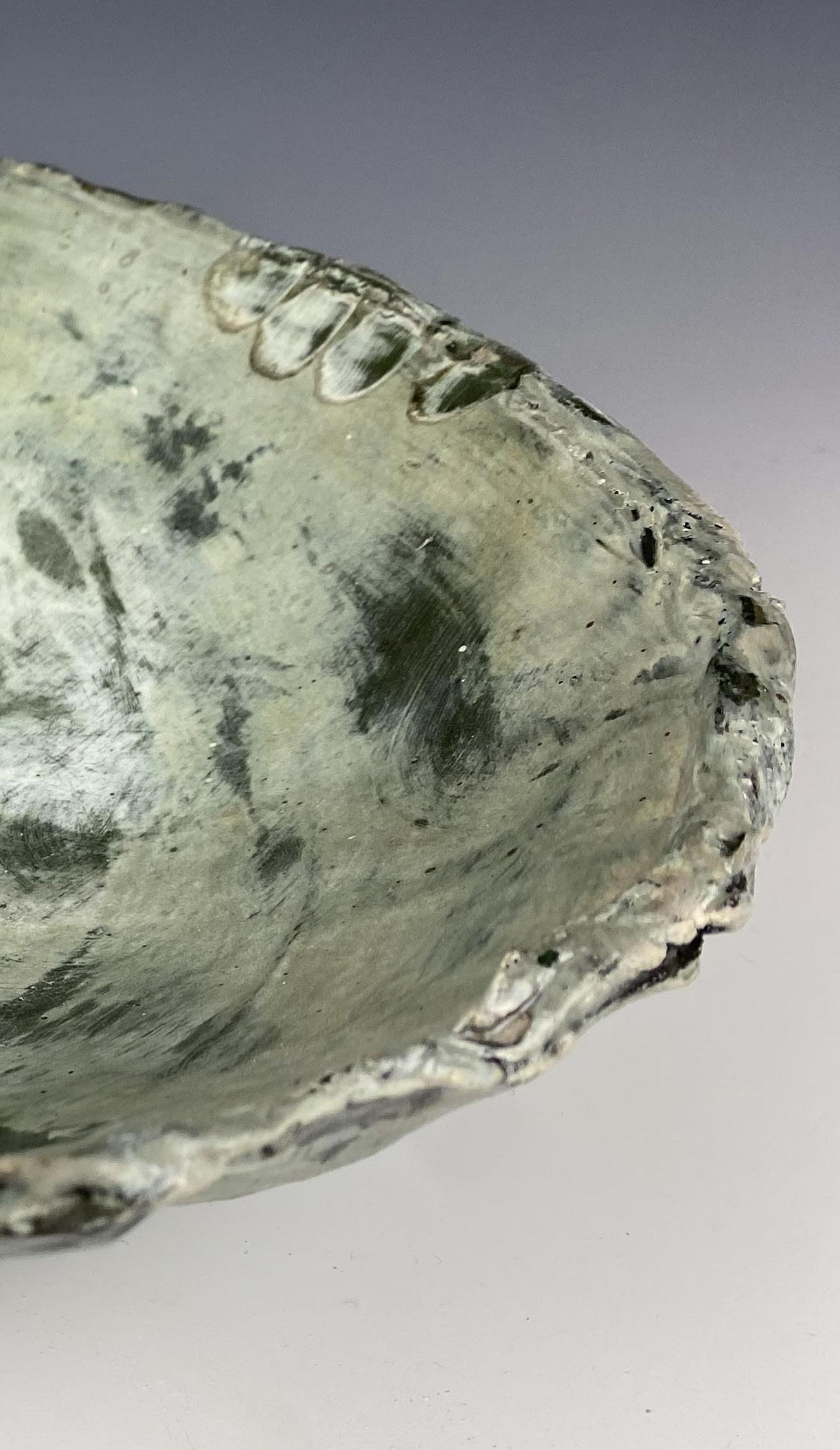

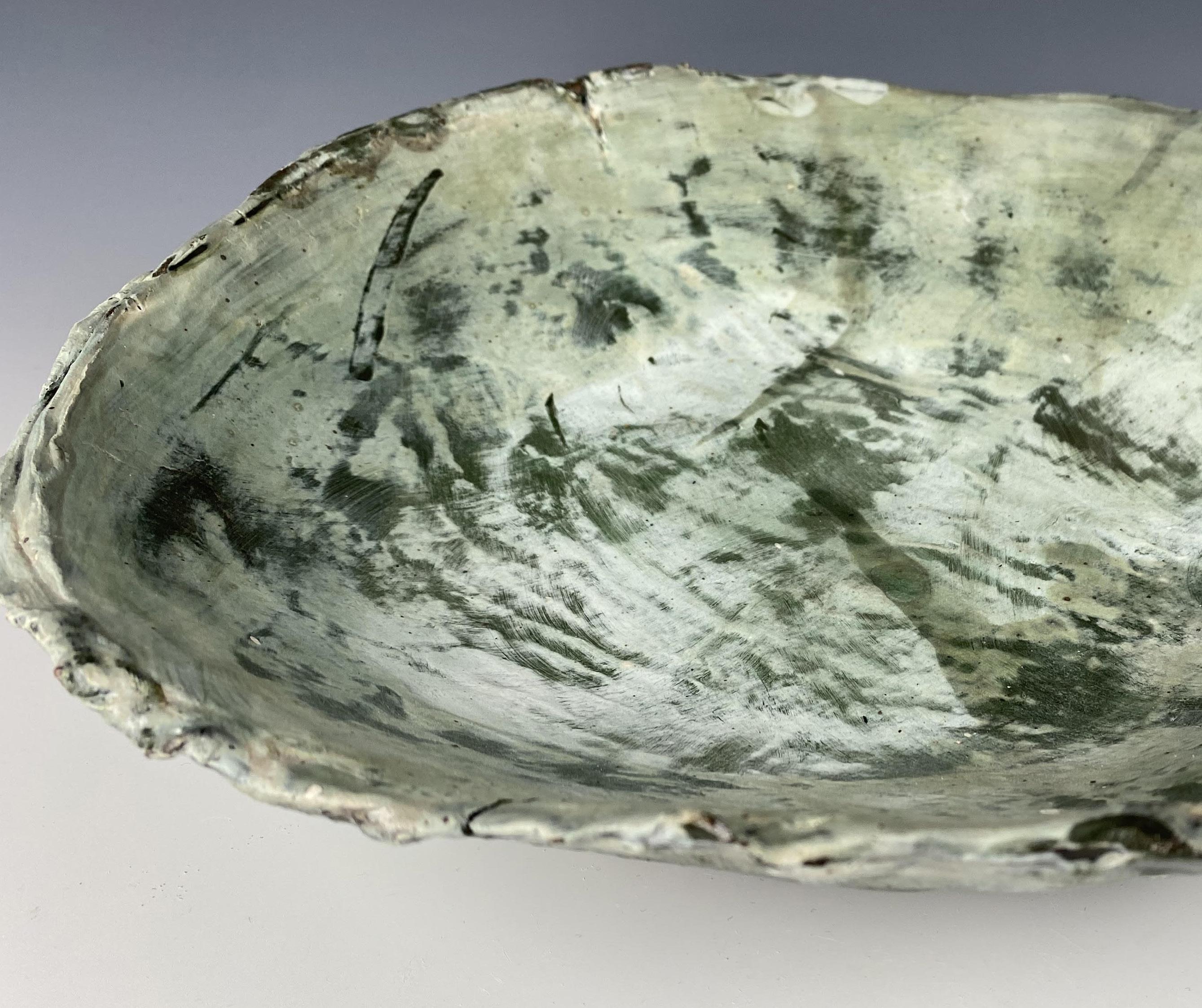

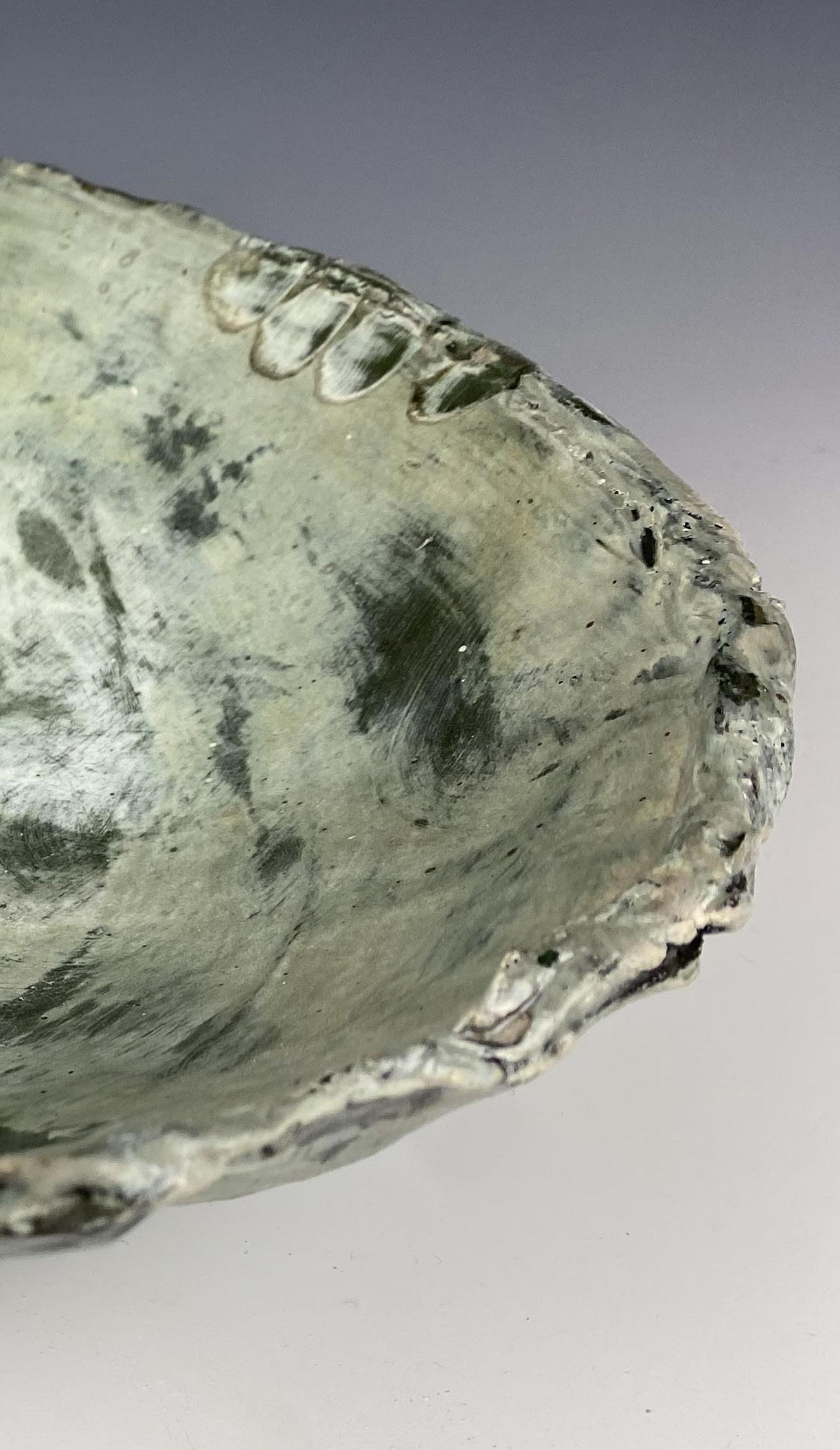

Forest Bowl / Mikkel Rawdon ceramic work

three, four days,” JC describes to me with his lilting voice that he always puts on whenever he is explaining something to someone.

Finally, they got their green cards, but JC was still in college in the Philippines and they needed to keep his green card active, so they would make periodic trips to the States, until eventually Lolo and Lola got tired of flying back and forth, so they told JC to just pick a state and go by himself.

“So of course, I picked New York.”

JC would take the transcontinental flight alone as an 18-year-old, managing the U.S. customs himself before being unleashed into the hustle-bustle activity of New York, roaming through the streets and wandering around the subways, exploring an entirely new world all by himself, experiencing independence for the first time.

“It was so fun,” JC recalls with a fond tone, “So much fun.”

Finally, the three of them ended up in Minnesota to join my mom, but, JC says, eventually Lolo and Lola “found the States a little bit too cold, and they loved their life in Manila,” so they returned home to the Phillippines, leaving JC in a new country without much of an idea about what he was going to do with his life.

“I was in law school back in Manila, but I very quickly discovered that I wasn’t cut out to be a lawyer,” JC explains to me after a short pause to take a drink and collect his thoughts, “and I knew I had this green card, so I just thought ‘you know, I’m young, I’m gonna explore my options.’ So I just stayed in the U.S. But I had no plans whatsoever. No plans.”

Eventually, JC realized he liked mental health, so he went to grad school for it, but the gray period when he didn’t know what to do still sticks in his mind.

“Looking back, fun times. There

/ 031 /

was that feeling of being lost, confused, not knowing what to do. But looking back it was fun.”

“How did you combat that lost feeling?” I ask, noticing a similarity to my mom’s feeling of loneliness, “Did you stay connected to Filipino culture and your family back home?”

“That was hard,” JC confesses, pleasant smile he had had melting away.

He talks to me about the technological barrier they faced — FaceTime, Skype, and Zoom hadn’t been invented yet, so it was all through email — he would go years only hearing his parents’ voices from compressed pre-recorded videos.

He loves Lola’s signature kare kare, peanut butter stew, and the way he talks of it makes it clear that it’s not just the taste that he likes — it also reminds him of home. Lolo’s sentimental genes live on in JC.

“It was a big adjustment for him,” my mom tells me when I ask her if she noticed JC struggling at the time, “I think JC is more sentimental than me. He gets more homesick, he misses Filipino food more. I guess he tends to our parents more, also, so when that was all gone — I think he had a hard time. It was sad to watch when he was struggling for the first few months.”

My mom did her best to support him: I remember ‘Tito JC’ living in our house for a while, and JC reveals that “it was a nice piece of home

/ 032 /

when I could talk with your mom in Tagalog.” She helped him adjust to living in Minnesota and taught him all the small things she had learned living in Minnesota. When JC thought his Burlington Coat Factory windbreaker was enough for the Minnesota winter, my mom laughed and got him real winter gear.

“I remember looking at your mom and thinking, you really have it made. You’ve figured it out. You’re a doctor in the US. You’re independent. You’re very knowledgeable. You’re just very skilled at all of these things. Things that I never really imagined myself to be doing,” JC remembers with a smile.

What’s funny is that JC and my mom hadn’t really spent much time together before JC moved to the States.

“Your mom and I weren’t close growing up. She was always out of the house. She was much, much, much older than I was. There was a fourteen-year age gap. So I spent a small part of my childhood with your mom, but the majority of the time, when I was in grade school, elementary school, she was already in med school,” JC says as a wailing cry breaks out in the background on his side of the screen, but now I’ve been in the U.S. for, gosh how long now? Since 2009? Your mom and I have gotten a lot closer.” JC pauses to think for a bit, contemplative, “So

if anything, one of the main things that I remember about immigrating to Minnesota is the relationship that I was able to develop with your mom, with my sister. It’s something that I didn’t have growing up, but now that I have it — your mom and I are very close, and I’m grateful for that.

“

Eventually, JC settled into the US. That cry in the background during the interview was one of his newborn twins. My mom, of course, also started a family. They try to visit the Phillippines as much as possible, usually every three years or so, to visit the remaining family. They often call Lolo and Lola, checking in on their health, wishing them a happy birthday or a merry Christmas. My mom makes sure to connect with them more often now. After years, decades, of living away from them, her love of independence has not disappeared, but it has been supplemented by a greater appreciation for her family. As a kid, living in Manila, she had always been with her parents, and that’s the way she thought it always would be, so being in the U.S. made her see a new kind of freedom. But

Of

course, immigrating away from the Philippines broke many bonds; my mom and JC left friends, family, relationships. But it also made them.

now, what was once abundant is now sparse, which makes their connection more poignant, like the last few bites of a decadent dessert. The physical distance between them seems to strengthen their bond. Each moment seems intentional, every second feels precious. In a way, immigrating away has made her connection to her parents even more important.

Of course, immigrating away from the Philippines broke many bonds; my mom and JC left friends, family, relationships. But it also made them. My mom and JC have a brother-sister relationship that seems stronger than any other I’ve seen before. I was shocked when I learned they didn’t interact growing up — their companionship seems so wholesome, and both of them are so

glad that the other is here. Leaving everything else made that one piece of home infinitely more meaningful, more important, more relatable.

“That’s one of the things that I want to mention,” JC says as my interview with him closes, “I immigrated, but I also gained a relationship with my sister. I think that is really quite amazing.”

I

/ 033 /

034 /

Stumpy / Anneli Wilson (9x13x7”) sculpture /

/ 035 /

Day in the Life of a Dog

by Rowan McLean

Iwoke up with the sun burning my face and my legs uncomfortably resting against the wall of my kennel.

I rolled out of the sun and into an upright position, ready to be released and itched my paw, biting it lightly while waiting for my owner to come downstairs.

It had been at least 25 minutes, and I started to have to go to the bathroom more and more. Moments before I began to bark, I heard a creek in the ceiling, the same one I hear every morning. I listened to the thumps as my owner made his way downstairs. When I finally saw him,

I Was Ecstatic.

He let me out of my kennel, and I jumped for joy. I couldn’t control myself or even feel my legs, for that matter, and as he opened the door to the backyard,

I darted out and made laps around the garden in the backyard. Suddenly, I remembered why I wanted to go outside, and it wasn’t to run around. I did my business and then returned to the house.

My bowl was already full of kibble alongside some refreshing ice-cold water.

The morning never disappoints.

Now came the time for the inevitable. My owner is leaving for what he calls work. I’m unsure who or what work is, but I’m not too fond of it. My owner grabbed his suitcase, opened the door, and left for work. I still felt tired from the running I did around the backyard, so I decided to take a nap.

Napping is just the best because it can make a day go by just like that. Sometimes, if I rest well, it can / 036 /

I Was A Cheetah.

feel like my owner was only gone for minutes.

But today, I woke up around 2 p.m. This was NOT ideal because my owner usually comes home from work from 6:25 p.m. to 6:36 p.m. I still had more than 4 hours to kill.

I started by walking around the kitchen island and putting my front paws up on the counter to see if I could salvage any food that my owner had left out.

I will never turn down a nice afternoon snack.

I spotted a half-eaten sausage with some ketchup and a bun on the side, and as soon as I saw it, it was gone and in my stomach. Yum. Another successful food run.

I sat on the ledge and looked out the window until I got bored. I hopped down and walked around in search of something to entertain myself. I saw that the gate to go upstairs was slightly loose. This felt like the opportunity of a lifetime, but I quickly realized it wasn’t.

I looked both ways to make sure no one was watching me, and then I

pushed my legs as hard as I could into the ground and leaped. As I was flying through the air, I realized that I might not make it. It felt like as soon as I was in the air, I was back on the ground after slamming my whole right side into the gate. It was now clear that jumping over the gate maybe wasn’t the best option.

I noticed a stinging pain in my right leg. I could feel my pulse throbbing from my toe to my knee, and I began to sob. It felt like I couldn’t move a muscle, but I managed to stumble back to my bed. I lay there and wept for a while before I faded into sleep.

When I woke up, I glanced to the right above the pantry to the clock, which read 4:54 p.m. Devastating. Every minute felt like an hour. My owner is never coming home. I felt worthless. Nevertheless, I lay there immobile until what felt like an eternity later when my owner returned.

It’s 6:32 p.m., and I hear keys rattling against each other as my owner continuously tries and fails to loosen the old, rusty, worn-down lock to open the front door until the lock finally clicks. I couldn’t stop myself from howling with excitement.

/ 037 /

Every day, it’s a bittersweet feeling when my owner comes home because, of course, I’m happy that he’s home, but at the same time, his return reminds me of how long he was gone.

My mood altered entirely from hopeless to fulfilled.

I know that my owner will come home every day, yet I’m still shocked with joy every time he does. I love spending time with him.

He’s the best.

I was greeted by petting as he took his shoes and jacket off and began making some pasta with marinara sauce, which was quite the common choice recently. As he finished cooking, he poured my bowl full of kibble once again, and I got to eating right away. Once we both finished our food, he got up and went to the wooden basket just out of my reach to prevent me from getting the toys inside.

As soon as he grabbed the blue whale squeaker toy out of the basket, I knew what was coming. My favorite part of the day. He threw the toy high into the air, and I leaped with all my might just in time to grab it with my canines and recklessly thump to the

ground and drop it, ready to do it again.

He does this twenty more times counting out each number as he goes, and it’s just as perfect the twentieth time as the first. I was exhausted. My owner returned the toy to the basket and flicked the light off before guiding me into my kennel. I was too tired to resist tonight, so I walked in and lay on my bed.

My owner petted me goodnight, and I swiftly fell asleep, ready for the next day.

/ 038 /

/ 039 /

Doodle / Sophie Nguyen (18x5”) ink on paper

/ 040 /

Turkish Lanterns / Nabeeha Qadri (9x12”) colored pencil illustration

The Progression

by Ellie Putaski

melodies, so common yet somehow unheard

a plea to draw one’s attention away from a piece so mediocre

. dissonance,

creeping into the cracks so carefully ignored

nothing is as it once was yet everything is somehow the same as before.

. silence, the volume of nothing so loud in between chords

a voice in your head saying Do you really remember?

. endings, acceptance that things aren’t as they once were

solidifying the finality of a choice that doesn’t even matter. that doesn’t even matter.

/ 041 /

They Fall

by Sofia Rivera

Minutes and seconds hang there limp as they are tossed around

Swinging from one side to another

The hours hold on, their grip slightly tighter than the rest

The string has been cut, and a minute falls

They try to hold on clinging for a chance at life

As they drop

One.

By.

One.

Into endless darkness, I place my hands out

But they fall through the cracks in my fingers

The wasted time of the people up above begs me as it falls

There is nothing I can do but watch -

As they slip into the world below my feet

/ 042 /

Strength / Dalia Wolkoff

Strength / Dalia Wolkoff

/ 043 /

(4x6”) block printing

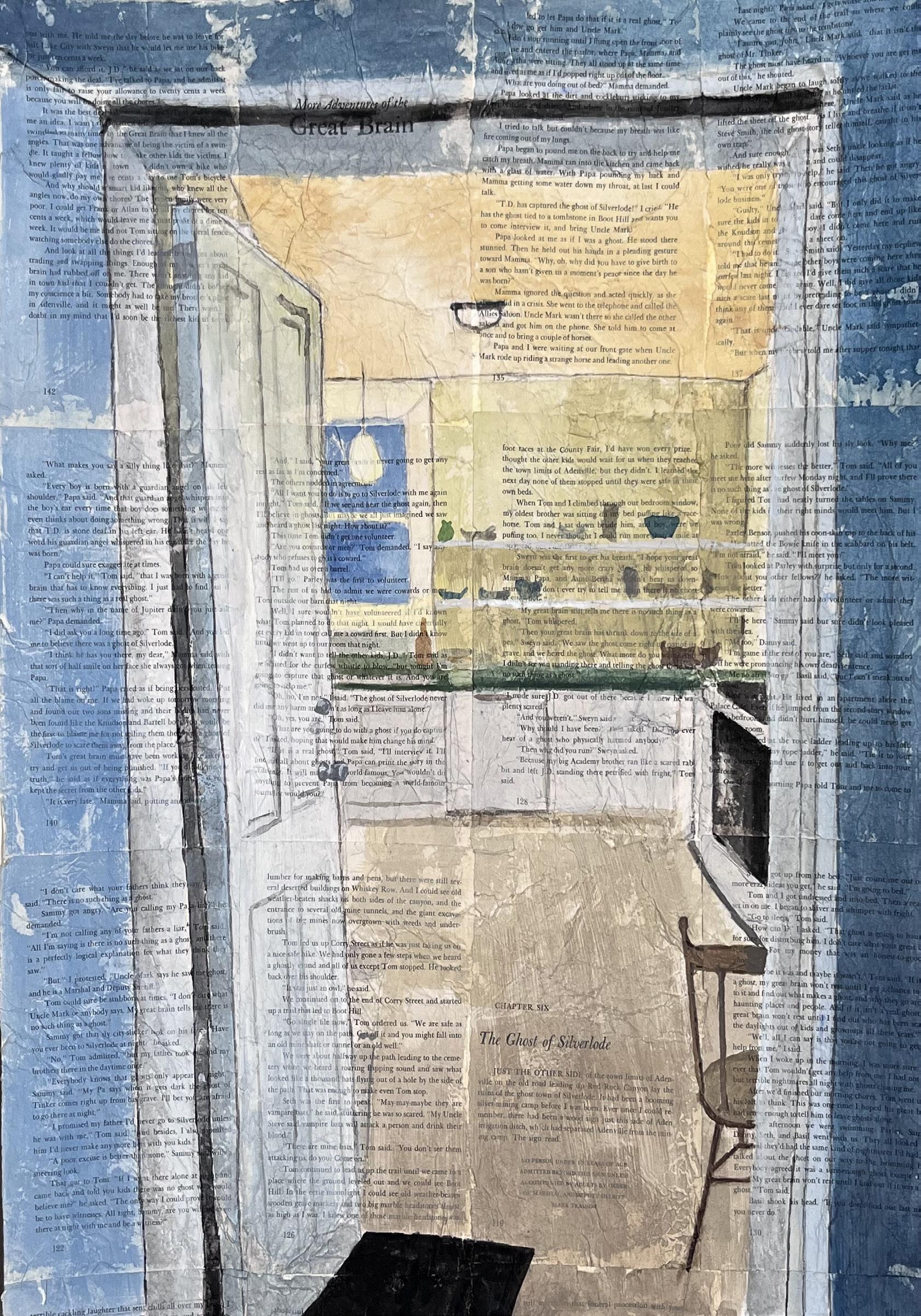

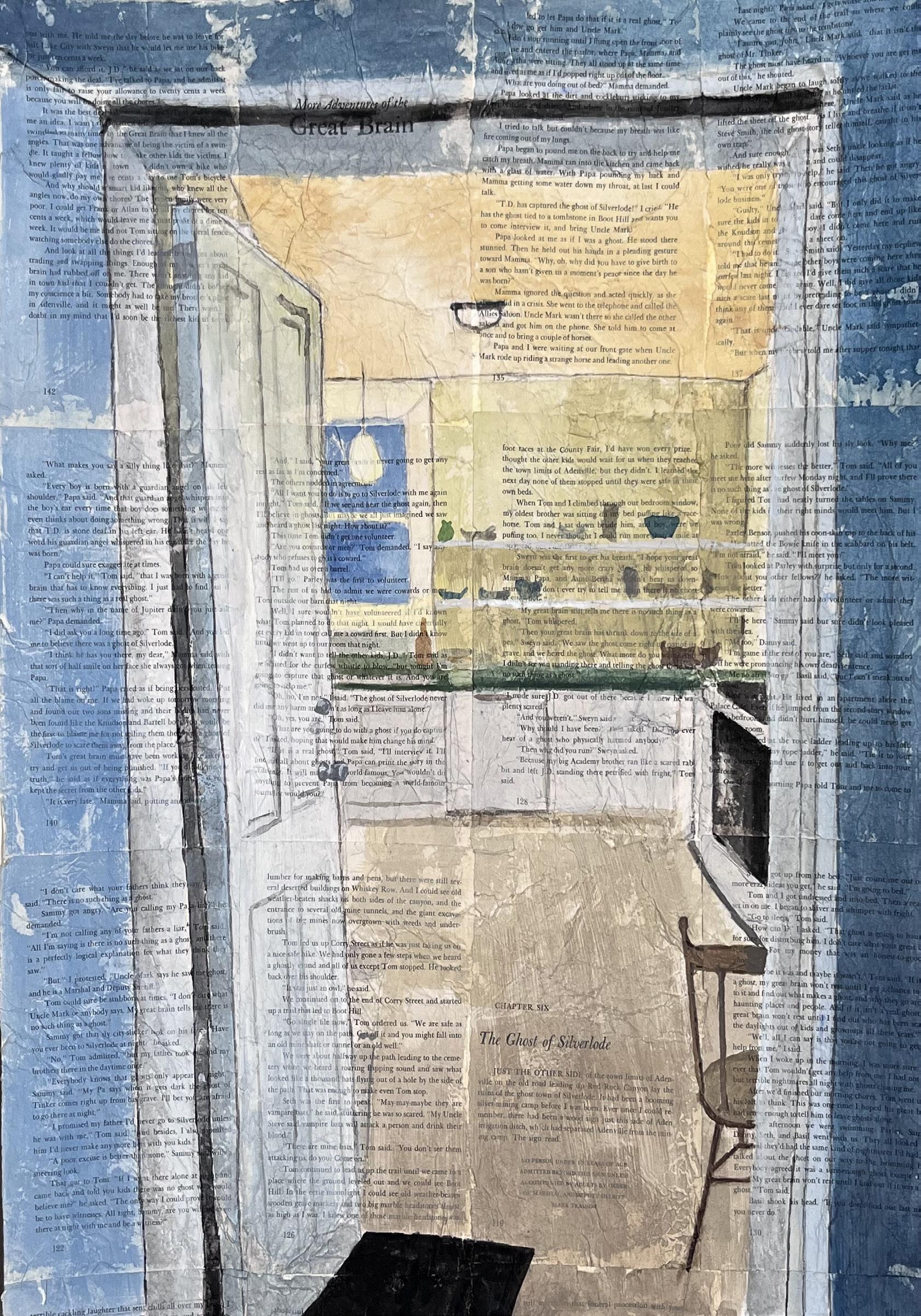

Growing Pains / Jane Higgins (36x24”) watecolor collage

Growing Pains / Jane Higgins (36x24”) watecolor collage

/ 044 /

Afterwards

by Eleanor Putaski

In the aftermath of the final act In the epilogue of a life thus led In the left over ink that never said “They lived ever after in the end.”

In the crumpled up pages that sit on the floor In the words thought but never explored In the plot holes and changes that remain ignored There’s a lingering question of “What happens afterwards?”

/ 045 /

Pando

by Sandro Fusco

All the same, at heart

My limbs extend

Rooted together, since the beginning

Short and dense

White bark, green leaf

I breathe wide

I experience, understand

All different, alone in emotion

They rise

Thin and separate

Beige, cream, ivory bark; lime, emerald, sage leaf

They inhale, gasp, yawn

They each feel, react

All together

It is

It exists ///

It becomes bright, patiently

It annoys me

I lose, shrink

But soon

It is dark

I absorb, seize, expand

It is blinding

Some burn, suffer, cry

They die, end / 046 /

But others

absorb, flourish

They become anew, grow

All together

It cycles

It continues

It is okay

///

It is sudden

Loud, itchy

I am uncomfortable, empty

I do not trust

It is deafening, piercing

Some pain, fall to their neighbors feet

Others are fearful

Their walls broken

All together

It is patchy, less

It struggles

Truly separate

///

I am full, but I am sick

I cannot feel myself

I am not

All the same

Where lay holes

Are put limbs, alien

Brown bark, orange leaf

Those between are choked

/ 047 /

They remain, but Wither

All together

It is infested, uneven It is weak

Can it continue?

Truly different

/// Already? Why? I hurt I don’t understand I won’t experience

One sees a spark It is engorged, ravenous They all see Crimson of a thousand suns, and From the heat does not come Freshness

All crumble, disintegrate

All together We aren’t

\\\ /

048 /

/ 049 /

Swirls and Hills / June Dalton painting

Celestial Vanity

by Liza Thomas

Slit my stomach and see the sadness: this is girlhood.

Open the scar from my umbilical cord, my remembrance of being, and see for yourself.

Peel back the comfort of my bed and see the pinkened rage that is my cocoon. See the hair sewn into the scalp, understand with me. Can I make you understand? Did you see my mother’s hands like golden ropes tightened around each ovary?

Did you see me on Sunday afternoon, God’s day, gripping the bus seat with dread? How I begged down on my knees, kissing the feet of divinity, with my hands to the sky: don’t remind me of my past. Yet placid ignorance, yet chipped paint that regurgitates laziness, yet taunting fear on my freckled shoulders weak from the sun, yet dark navy doubt that tinges the ends of my hair. The world is my enemy now; oh you are the Devil, said us both.

Crumbs in a casserole dish: that’s what I bring to the table. An elegant knock on your door.

My pitch: if I shave the delicate layers, flakes and bleeding hair covering the floor, Can I make you see how the fault isn’t mine?

Someone take me to bed, someone take me apart, someone dismantle the pieces and strip the satin of its purity: lungs placed at the foot, heart at the head.

/ 050 /

Does God have an answering machine? Or a mailbox, an advice column– somewhere I can reach him. Does he take requests? Can he make them see?

Survival tapdances on the horizon as the pink of a child paints the Western sky: Does she know her time is limited? That it will be spent trying to make them listen, make them see?

/ 051 /

Big Wave Teapot / Ethan Peltier ceramic work

/ 052 /

Birds / Anisa Deo (25x24”) mixed media

The Starlings

by Eliza Farley

Swift, sleek, darting to and fro— the starlings group in a thrumming cluster, small bodies forming a larger body, blacking out the clouds, the sky. I have seen it only once before.

Today, it is incomplete. Before, the starlings were as one, simply one large bird in the sky, no cluster, no thrumming.

The bird slithered down my throat and touched my heart, in the middle of it, that’s how it felt to me. Me and my heart and I— me and the bird. Us, one, no cluster. No clouds. No sky.

Today, it is incomplete. But, still, I feel in the middle of my heart— there, that emptiness where the large bird used to be— there, I feel a small body turning into a larger body, one with gaps between the joints where the sky shines through.

Still, I hold this moment over my memory like a suncatcher: seizing that which slides over so quickly, reflecting it inward a thousand times, brighter and more colorful, until it becomes something new entirely.

/ 053 /

Spiraling Hills / Duncan Lang (9x6”) watercolor on paper

/

054 /

Camera

by Sam Hilton

A person snaps a photo the camera a forgotten

The folder stuffed

Its pockets ripping and its seams coming apart

Papers falling everywhere,

Out of the printer hoping you will remember

The papers, so many so

The perfect one will be disclosed

The sensation of a photo.

Perfect. Hoping it’s one of a kind

It seems it can store

Infinite until it snaps.

Outside bustles while inside it is frozen

The camera closes its eyes, the brightness and color

Being remembered

Beneath the piles of papers thinking about what to do

Silenced and frozen

Brilliance being thrown away

Only in bursts of being broken and then waiting

To be fixed

Silently waiting holding back

The camera closes itself to the world

Waiting to be asked again to remember

/ 055 /

Pieces of Migration

by Humza Jameel

They had heard stories about how cold Minnesota was and were warned by some friends, yet the chill from the open airplane exit door still left them stunned. While speed walking through the passenger boarding bridge, X, expecting to see Y’s jet-black frizzy hair, turned to find Y slowly pacing the length of the bridge. Her camera somehow already in her hands, Y was staring out into the runways covered in a mystical layer of thick snow. X had always loved her ability to always find magic in small moments through her artistic eye. All thoughts of hurrying past the bridge and into the heat of the MSP airport disappeared, as X also found himself captivated by the nonstop falling of snow. Wave after wave after wave after wave after wave of snow. No sound upon impact. Just the howling of the wind through the glass bridge.

Y had come to a realization that she didn’t know when she would return to her home country, so she took pictures of everything. Her bedroom cluttered with medical textbooks and papers. She will not forget. The beautiful marble stairs leading up to the red furniture living room. She will not forget. Her parent’s bedroom filled with photos. She will not forget. The dining table filled with food and snacks. She will not forget. The workers at her house. She will not forget. The view outside of each and every window. She will not forget. Her vibrant parrots outside. She will not forget. The energy of her younger sister. She will never forget. The kind faces of her technical aunt and uncle who took her in as a toddler and raised her as their own, her parents. She will never forget. The wrinkled skin and warm smile of her grandmother. She will never, ever forget.

/ 056 /

/ 057 /

Window to My Imagination / Nabeeha Qadri (5x9.5”) watercolor

/ 058 / Cross / Claire Kim

(8.5x11”) photography

/ 058 / Cross / Claire Kim

(8.5x11”) photography

/ 059 /

Elaina Elliots

by Chloe Kovarik

Content warning: graphic violence, murder, and suicide

He’s coming!

Shh!” Elaina Elliots whispered to her friend, Hallie Waller, who was rustling around in their hiding spot under the small table in her walk-in closet. Her friend quieted down as they heard a boy shout through the house that he was beginning his search.

The boy–Scotty Davis–walked through the house, scouring every room. Whenever he found someone, he would yell out to let everyone know. As he kept going, Elaina was counting on her fingers to see how many people had been found. So far, four people had been found so that meant that there were four people left.

Elaina and Hallie heard Scotty open the door to the room they were in. Both knew that he would be checking the walk-in closet so there was a good chance that they would be found in the next minute.

The door to the closet opened and Elaina could swear she and Hallie both stopped breathing. Both awaiting being found out. Scotty moved things around and neither girl had a good angle to see what he was

/ 060 /

doing so they could only hold their breaths and wait.

After what felt like hours, Scotty looked under the small table in the back. He grinned when he saw the two girls cramped under there, limbs intertwined. “Found you,” he said and helped both of them out of the cramped space.

“Hallie and Elaina were found!” Scotty shouted through the house as he began walking to the next room he would search while both girls made their way to the house’s living room where the jail was. They found five of their friends there.

There were two comfy chairs left so they both took one. “Where were you two hiding?” one of the girls asked.

“Walk in closet.” Hallie responded. The now seven of them struck up a conversation as they waited for Scotty to find the remaining two hiders.

They all stopped their conversation when they heard footsteps and a defeated looking Janie Parker walked into the room. Elaina was the one to ask where she was hiding. “Laundry room.” Janie explained, plopping down on a chair.

Scotty returned to the living room with the victor, Seb Trainor. He had a big grin on his face as Scotty grabbed his hand and held it above his head

and all the losers cheered for Seb. Since the game was over and the group of ten was bored, Elaina ran down to the cellar and brought up bottles of liquor. The group all whooped for their friend as she got out cups and started pouring shots.

“Alright, gang.” Scotty Davis addressed his work room. “It’s almost five, but it’s also a Friday. Let’s all pack up early, shall we?” the room full of people all grinned and murmured their approval. “Well then, see you all Monday.” Scotty said and slung his bag over his head before walking out of the building and to his car.

He stepped in and fastened his seatbelt and turned on the radio; The Beatles were playing. Scotty started up the car and backed out of

the parking lot. He started the drive home, humming to the song playing over the radio.

It took no more than ten minutes to drive home. He pulled into the garage of his house, turning off the car and walking into his house. “I’m back!” Scotty yelled through the house and waited a second before he heard little footsteps coming down the stairs.

Scotty grinned when he saw his little boy come running into the kitchen and wrapping his arms around Scotty’s waist, hugging him tight. Scotty hugged him back, ruffling his golden hair. “How are you, Myles?” he asked, gently unwrapping the boy from his waist.

“Great! Andy, Tanner, and I built a sandcastle at the beach today!” Myles

north / Hadley Dobish (4x6”) photography

north / Hadley Dobish (4x6”) photography

/ 061 /

said excitedly, using his arms to show how big the sandcastle was.

After a minute of Myles telling his dad of what he did that day, there was another set of footsteps coming down the stairs and this time one Emily Davis came into the room. She walked up to Scotty and gave him a quick kiss. “How was your day, love?” Scotty asked his wife.

Emily laughed and looked at Myles. “I think our boy summed it up pretty well.” she said and Scotty nodded, smiling. “What about you?”

Scotty shrugged. “Boring as hell” Scotty didn’t have any time to continue when Emily swatted his arm and Scotty sighed, knowing what she meant. He grabbed his wallet and put a crumpled dollar bill in the jar on the counter labeled ‘SWEAR JAR.’

“Have you made dinner or do you need me to?” Scotty walked to the counter to see what was in the pan. He got his answer as he saw ground beef in the pan. He then noticed tortillas on the counter next to it along with cheese, tomatoes, lettuce, and sour cream. “Tacos.” Scotty hummed and Emily nodded.

“I wanted tacos!” Myles’s voice came from the room over and Scotty glanced over to see his son playing with a toy train.

“I’m gonna go upstairs to rest. Call me down when you guys are ready for dinner.” Scotty said and slipped off his shoes before walking up to his home

office and setting his things down. Scotty walked into his bedroom and flopped down on the bed, exhaustion getting the better of him.

Since sleep wasn’t coming as easily as it usually did, Scotty got up and just sat there, staring at his bulletin board. Some papers came and went from it but one of them stayed there ever since it was printed in the paper. Written in bold was the headline ‘Elaina Elliots found dead in her own home August 3rd. Cause of death: Unknown’.

That night, something happened, something very bad happened, and Scotty was the cause of it. Scotty was not at all proud of himself for what he did, and he even felt like dying afterwards. Ever since he’d been trying to go straight. He stopped drinking, actually went to college, and got a decent job. He had met Emily and three years later, they were married with a baby on the way.

Scotty didn’t have time to dwell on the past events because Emily called him down for dinner. Scotty shook his head, trying to rid himself of the thoughts of that night as he descended to the first floor of his house of tacos. Though the second Emily saw his face, she knew that her husband was thinking about that night.

Emily had asked multiple times why Scotty was so hung up on that newspaper but she never got an answer, or at least, she never got the / 062 /

right answer.

Though neither had a chance to discuss because Myles bounced his way into the kitchen, grabbing his plate and beginning the assembly line of toppings. Emily got behind him and Scotty was slow to follow. “Ew!” Myles broke the silence of the room. “You guys know I hate sour cream!” Myles wrinkled his nose at the sour cream before sitting down at the table and folding up the taco.

Once they were all sitting down, Emily started a conversation. “I was thinking of taking Myles and his friends to the beach again tomorrow.” Myles lit up and instantly nodded his head.

“

on him.

“What…?” Scotty trailed off. He stood up and stepped outside, closing the door behind him so it was just the two of them. “Who are you?”

The woman chuckled to herself. “Scotty, Scotty Scotty Scotty,” she said, smiling. “How could you not remember me?” It took Scotty a minute to realize who was standing in front of him. When he had first opened the door, there was something familiar about the woman and now he knew.

Let me ask you something. Does Emily know your secret? Does she know what happened on August 3rd, 1992?

“I can take him.” Scotty offered but Emily didn’t have time to respond because suddenly the doorbell rang. “I’ll get it.” Scotty said before standing up and walking to the door. He opened it and a woman he didn’t recognize was standing in front of him.

“Scotty Davis?” the woman asked and Scotty nodded. The next minute happened so fast, the first second he was standing there and the next he was on the floor, his cheek stinging from the hit the woman had gotten

His eyes went wide. “You have to leave,” he said in a hushed voice. “You can’t be here.”

The woman only widened her smile. “Why? Because you found a wife? Had a kid? I’ve gotta say, you’ve changed a lot. It was hard to find you,” the woman said. “Let me ask you something. Does Emily know your secret? Does she know what happened on August 3rd, 1992? Does she know what happened to Elaina Elliots?” the woman asked, taking a step closer to Scotty.

“Apparently nothing.” Scotty said, laughing now. “And how the hell do you know my wife’s name?”

“I know everything about you. Your son’s name is Myles Benjamin Davis.

/ 063 /

Your wife is Emily Valerie Davis, used to be Hawking,” the woman listed, just giving Scotty a taste of what she knew.

“What do you want?” Scotty asked, now getting angry.

The door behind Scotty opened suddenly, and Scotty whipped around to see it was Emily. “Scotty, what’s taking so long? Myles is getting impatient.” Emily’s eyes traveled to the woman behind Scotty. “Who might you be?” she asked.

“Just an old friend of Scotty’s. The name’s Elle.” Elle walked up to Emily and shook her outstretched hand, smiling. “I was in the neighborhood and thought I’d stop by and surprise Scotty.”

Emily nodded. “It’s so nice to

meet you!” She then turned to Scotty. “Don’t take too long otherwise Myles will be the one out here next.” Scotty nodded and shut the door. Scotty waited a minute to know that Emily was gone before turning back to Elle.

“Elle?” he asked, raising a brow.

“I needed a change. Especially after that night.” Elle explained. “Well, Scotty. I shouldn’t keep you from your family.” She grinned as she said that and Scotty got a shiver down his spine. “Well, I guess I’ll be seeing you shortly.” Elle said and gave Scotty a small wave as she walked down his driveway and turned the street corner, leaving Scotty staring after her.

He shook himself off and walked back inside. He noticed that Emily and Myles weren’t talking, they were

/

064

/ the rush / Hadley Dobish (4x6”) photography

waiting for him. “I’m sorry that it took so long. I just haven’t seen Elle in forever. We were just catching up with each other,” he lied.

“I’m surprised I have never heard of her before.” Emily said as Scotty took a seat at the table.

“I’m sure I’ve mentioned her once or twice.” Scotty muttered to himself and was thankful that Emily didn’t catch it.

The three of them began to eat their dinner and Myles started talking about a new toy that his friend had that he wanted. All throughout dinner, Scotty couldn’t stop thinking about Elle stopping by.

That night, it haunted his dreams. Scotty dreamt of Elle and August 3rd and what he did.

The next morning, Scotty awoke in a cold sweat. He was soaked with his sweat and was breathing heavily. He looked next to him to find that he was in an empty bed. Emily must’ve already gotten up.

Scotty got up and went to the bathroom, taking a shower and brushing his teeth and hair. Scotty walked downstairs, and was surprised to find that the house was quiet. Usually he was woken up because Myles was shouting and running around the house.

On the fridge, there was a note, but it wasn’t written in Emily’s handwriting. Or Myles’s for that matter. He took the note and read it.

It told him to look in his guest room. Scotty’s heart started beating faster and he slowly walked towards his guest room.

The door was closed so he put his hand on the handle before swinging it open. The second he did, the strong stench of blood hit his nose and he threw up on the spot.

Once he was done spilling his stomach on the floor, he finally could process what was in the room. On the bed were Emily and Myles. Both of their eyes were open and bloodshot. Their whole bodies were covered in blood and the walls were painted with it.

Scotty turned in a slow circle, and found a message on the wall behind him. It read ‘Courtesy of Elaina–Elle–Elliots.’ Scotty knew that she was going to be back.

Though there was still more. There was a Post-It note of Myles’s forehead and Scotty lifted it off of his dead son. Tears finally finding their way out of his eyes and pouring down his face. The note said to go to his backyard, and he did. Scotty knew that nothing could be worse than seeing your dead wife and son.

In the backyard, it looked the same, except for one thing. On the branch of the oak tree, was none other than Elaina Elliots with a rope around her neck that was tied to a tall branch of the tree. / 065 / I

/ 066 /

Kado No Mise / Lucy Schaffer photography

/ 067 /

Net / Bora Mandic (15x9”) ceramic work

My gnarly legs twist

By Oliver Conrad-Wovcha

My gnarly legs twist and fight through the thick soil, searching for some escape from the ceramic walls that confine me. My stretched arms drape over the borders, reaching in vain, hoping to encircle anything for support. The home in which I abide provides me with an area just large enough to have an illusion of freedom. The thought is ever-present that I may escape to nature, where I truly belong. Alas, I am trapped in a box, atop a box, all within another larger box.

As far back as I can remember, I have been constricted. When I emerged from my tiny capsule, rupturing through the dirt above, I was already in captivity. In the oblivion of my youth, however, I knew nothing else. The sun streamed through the invisible barriers, warming my small hands that stretched upwards as if pleading more and more. As the light fed my constant appetite and water trickled down into my many open mouths, I grew rich and strong. Numerous additional hands shot out from my arms, seeking as many nutrients as they could. All was well, and I presumed my domain to be bound-

/ 068 /

less, my growth limitless, and my strength all-powerful.

Soon, however, I was confronted with the harsh reality of my situation. As my legs dug into the bottom of what I thought of as my home, I realized it was truly a cage. While it was the same light, water, and air that fed both myself and my friends on the other side, I was fundamentally different. As I watched my friends thrive, growing tall, passing out of my view from the invisible barriers, and scraping the heavens, I longed to be free. I had the innate sense that I belonged among them. I was fierce, strong, wild, and convinced that my borders were a hindrance to my livelihood.

The seasons soon began to shift. The mighty elders I had seen thriving seemingly just moments before turned the colors of the sun and then dropped slowly to the ground, bowing down to the forces that had previously nourished them. I could feel the cold trying to seep into my domain, but the invisible forces kept it at bay. In horror, I observed every last one of my kind wither, crumple, and decay. Even those many times stronger than myself succumbed. But why not me? Something about the walls that en-

trapped me pushed life into my veins.

With the vulnerability of my species coming to light, I found some comfort in my own condition. I thought: I must have been chosen. Some greater force must have decided to bestow upon me shelter, placing me within a realm of safety and stability. But amidst my happiness, I felt a profound sense of loss. With my inability to survive in my natural habitat, was I still an authentic piece of the nature that produced me? I began to wonder. Was my domestication a protection, enhancing my original state, or was I now a completely different species?

What placed me in this predicament was the desire of my captors to mimic the outside world. To trap me inside their bubble, keeping me alive so that my presence helped them forget what they had become: unfit for the natural world. They assumed that a lazy life requiring no fight for survival was ideal. But while their choice was a conscious one, mine was not. I craved natural competition. To dig deep and fight against the others surrounding me. To reach out and climb, twisting and grasping to evade shade, struggling for life-giving light. To consume from both above and below ground. Those who trapped me could never understand this. Generations of sheltering had made them weak, both physically and mentally. They were unable to comprehend the intrinsic need to be self-sustaining.

They lived off one another, never providing solely for themselves. If they found themselves alone in this world, their demise would be inevitable. To understand my natural desires would be to roll back centuries of progress, and so they closed their minds to this possibility.

As the years passed by, I grew, but I grew further from who I was meant to be. I drooped and paled, let go of my arms, and began to curl. I lost my former desires and accepted my easy, domesticated life. The wildness trickled out of me with every tap water drink I was given. As death gradually encroached, I could not escape the thought that I was no longer part of the wilderness, after all; in the end, I was nothing more than a houseplant. I

“

I

craved natural competition. To dig deep and fight against the others surrounding me.

/ 069 /

(5’x4’) mixed media painting

/ Examining Death / Bri Rucker

/ 070

/ 071 /

ARTIST STATEMENT: Cordyceps Journal

by Annika Lilligard

n this artistic endeavor, I delved into the eerie and enigmatic world of Cordyceps, a parasitic fungus that invades arthropod hosts and alters their behavior, ultimately emerging from their remains as elongated club-shaped fruiting bodies. Through a series of journal entries that have been made by a biologist, I aimed to capture the evolution of an individual’s relationship with an ecological nightmare.

Central to my work is the deliberate omission of details about the narrator. This intentional choice veils the human aspect, directing focus toward the broader theme—the blurred boundary between humanity and the natural world. By withholding personal attributes, I aim to emphasize the universal connection shared with the environment, challenging traditional notions of good and evil within the context of the Cordyceps’ infection.

As a botanist embarking on a journey to comprehend these fungi, the narrator becomes a vessel for the intricate dance between nature and the altered human form. Inspired by “Annihilation” and Unit 2

works, I employed journal entries for immediacy, forging an intimate connection with the narrator’s transformative odyssey. The narrative lens shifted from a detached scientific exploration consisting of a series of observations to an introspective understanding of the ecosystem and the human psyche entwined with it.

The intentional degradation of the narrator’s writing quality throughout the journal entries mirrors the insidious influence of the Cordyceps on the protagonist’s cognitive faculties. As the parasitic fungus infiltrates the protagonist’s mind, the linguistic decline reflects the progressive deterioration of mental acuity. This deliberate choice immerses the reader in the unsettling experience of the narrator, symbolizing the transformative and invasive nature of the Cordyceps’ influence. Additionally, it distances the reader from the narrator making it harder for the reader to connect with the narrator’s altered state of being as they become a hybrid between human and Cordyceps. The blurring of coherent thought and the emergence of disjointed ideas serve as poignant indicators of the narrator’s

/ 072 /

diminishing grasp on individual consciousness, evoking a visceral response and heightening the impact of their descent into the amalgamated consciousness of the Cordyceps’ web of interconnected thoughts.

Given more time, I would delve deeper into existential and ecological themes, unraveling the narrator’s relationship with the fungal consciousness and the profound implications of their consciousness, evoking a visceral response and heightening the impact of their descent into the amalgamated

consciousness of the Cordyceps’ web of interconnected thoughts.

Given more time, I would delve deeper into existential and ecological themes, unraveling the narrator’s relationship with the fungal consciousness and the profound implications of their metamorphosis. Further exploration of the philosophical questions surrounding nature’s morality and humanity’s intricate role within it would enrich the narrative, offering a more nuanced exploration of these profound and thought-provoking concepts.

/ 073 /

A Trapped World / Sofia Rivera blown glass

Cordyceps Journal

by Annika Lillegard

Cordyceps: a parasitic fungus within the Ascomycota division, Family Cordycipitaceae, known for infecting and ultimately killing its arthropod host, emerging as elongated club-shaped fruiting bodies from the host’s remains, and exhibiting potential medicinal and ecological significance.

Journal Entry 1

Date: July 5, 2033

Today, I embark on a perilous journey into the heart of an ecological nightmare. The Cordyceps is a cruelty to nature, consuming not only insectoid hosts but the very environment itself. As a botanist, I feel a deep sense of responsibility to understand and potentially explore this environmental anomaly.

Journal Entry 2

Date: July 12, 2033

Beyond the quarantine, a dystopian wilderness prevails, transformed by the invasive Cordyceps. Lush forests, once vibrant with diverse and thriving life, now host grotesque amalgamations of plant and fungus, a chilling testament to this plague’s adaptability. My hidden cabin provides solace as I clandestinely observe this relentless march of the Cordyceps. Amid the pervasive fungal spores, the boundary between humanity and nature blurs. Caution is my constant companion, for their influence may breach even my refuge. The eerie transformation continues, and I realize that my journey into this grotesque disease has only just commenced. / 074 /

Journal Entry 3

Date: August 1, 2033