11 minute read

DESIGN CONSIDERATION

5.2.7. Excessive noise or lack of noise.

Noisy building types such as factories can be placed underground to isolate them from the surface environment. Although this offers benefits to those above grade, it may create excessive noise levels within the space which have well-known effects on hearing impairment. On the other hand, underground spaces can be totally isolated from external sources of noise, creating a silent environment. In some cases, however, such total silence may be unnerving and may diminish acoustical privacy within the space.

Advertisement

5.2.8. Lack of exterior view.

The lack of exterior view from an underground space is another reason for dissatisfaction with this type of building. In addition to providing natural light and sunlight, windows provide a direct view for observing weather conditions, creating a sense of contact with the environment, and giving visual relief from immediate surroundings. Different studies have indicated different relative importance for natural light and view. People in work environments are more likely to favor a view over direct sunlight, especially if no solar shading is provided and if they are not free to relocate themselves out of the sun when desired. Occupants of high-density residential developments are more likely to cite the availability of sunlight in the home as more important than a good view.

5.2.9. High humidity.

Unless controlled, summertime humidity levels will be higher in underground structures than in above-ground structures, as humid outside air is cooled by the earth-covered walls. Humid or damp conditions have not been linked directly with physiological problems, although they may exacerbate certain ailments such as rheumatism. Damp conditions may also encourage the growth of mold and thus increase the potential for allergic reactions.

5.3. Impact of Building Use on Problems

Before concluding which effects are most critical and suggesting design approaches to ameliorate them, it is useful to review the various factors related to building use that influence either the psychological or physiological effects. These factors, listed below, can serve to diminish the potentially negative effects and help to alleviate building user concerns.

5.3.1. Activity within a building.

Internal activity within a building that can offset the lack of external stimuli will normally be beneficial in a work environment, provided it is not too intrusive in terms of noise or distraction. Although internal stimuli may help to a levitate the negative psychological effects produced by no natural light and exterior view, it has no impact on the physiological effects of a windowless environment.

5.3.2. Occupancy patterns.

An individual's reaction to an underground or windowless environment may be substantially affected by the length of time he or she expects to spend in that environment. Underground facilities used primarily for short-term activities, such as indoor sports facilities, restaurants, libraries, and shopping centers, will thus normally raise fewer objections than an underground office. Not only are negative psychological reactions less of a concern when occupants are in underground spaces for shorter time periods, but negative physiological effects are less critical as well.

5.3.3. Need for underground location

Employees of underground or windowless facilities appear to be more accepting of their environment if they perceive a rational basis for the location or design of the facility. In other words, since windows are detrimental to the operation of many sports facilities, museums, restaurants, and shops, employees and visitors do not focus on the lack of windows as a drawback. Similarly, windowless laboratory and manufacturing environments provoke less criticism than windowless office buildings. Although this perception of windowless environments as appropriate for some functions can reduce some psychological effects, it has no impact on negative physiological effects. Job satisfaction. / Employees who are more involved in their work and derive considerable satisfaction from it may be more tolerant of windowless space than employees who work at repetitive tasks. The extent to which this can actually offset the various negative psychological effects is likely to vary considerably from individual to individual.

5.3.4. Design Responses to Problems

The various problems of orientation, image, psychological and physiological concerns discussed in the previous section focus on a few key elements of building design. These are the definition of an exterior image, the entrance design, providing natural light and view, and interior design. Approaches that have successfully resolved these areas of design are presented in this section.

5.3.5. Defining an Exterior Image

Beginning with the least visible design approach, an underground building can have virtually no exterior form at all. Such a windowless chamber would be suitable only for certain functions, such as auditoriums, classrooms, laboratories, or various service and storage spaces. The nonexistent form that results from the lack of visible building mass or edges can be reinforced by not using built forms for entrances, service access, or mechanical systems. Elimination of these forms is usually possible only when the underground building is connected to the below-grade levels of an existing above-grade structure, so that access can occur through the above-grade building. If connecting an

Design Consideration

underground building to an existing complex of buildings is inappropriate, it is still possible to create a building with limited or minimal exposure. A structure can be placed completely below grade, with only entrances, skylights, and courtyards exposed to the surface. Although a building beneath the surface is evident, the character of a "non-building" can still be achieved. Although the library is simple and unobtrusive in its historical setting, building edges are clearly defined by a narrow-recessed courtyard along most of the building perimeter. A larger sunken court at a major circulation crossing provides a clear entrance. A different approach to the exterior form of an underground structure is to place the building above grade with earth bermed around it. Rather than being as unobtrusive as possible, the berms represent an additional object on the andscape. This can provide a distinct image and can define building edges and exterior space. Entry into a bermed building can be more easily achieved than entry into a completely subgrade structure. Plant materials, retaining walls, building materials, and other landscaping elements may significantly influence the image and character of the building. The use of native plants, wood, stone, and berms that appear to be elements of the surrounding landscape can produce a natural image, as demonstrated by the Many of the inherent problems of entry, service access, and image are greatly reduced or eliminated if above grade space is combined with below grade space in one building. Even if the amount of space above grade constitutes a small percentage of the total building, a definite built form appears above grade. The use of an above-grade portion

Design Consideration

of the structure to resolve access and image problems is certainly appropriate in many settings, although some of the benefits of underground buildings-preservation of the surface and integration with the natural environment, for example-may be compromised.

5.3.6. Entrance Design

The exterior form and character of underground buildings, the entrance was discussed as a key element of the exterior image. In terms of the entire site, recognition of and orientation toward the entry is an important concern. The focus of this discussion is the relation between the manner in which underground buildings are entered and psychological perceptions. The degree to which a pedestrian entry is important as a design element is, of course, related to the function of the building. In an underground warehouse, the entrance for a few workers is not as important. as the functional needs of delivering-and storing goods. The entrance design is of greater concern in an underground office or factory where larger numbers of people are employed. And, compared to facilities where people enter and leave once a day, a public building such as a library, museum, or auditorium with many comings and goings requires even greater attention to entry design. Viewed from the exterior, the entrance may be the dominant image of a building that is mostly below grade. It serves as the transition from the exterior to the interior. As such, it can reinforce negative associations with underground buildings. The entry area in any building should be a key element in orienting and directing people to the spaces inside, and particularly so in an underground building. In addition, the entry often serves as a major area for admitting natural light and exterior view to a subsurface structure, since it may be one of the few points of exposure to the surface. In order to minimize the negative feelings associated with entering an underground building, several basic techniques are used. The most common technique attempts to create an entrance that is similar to the entrance of a conventional building. It is most desirable to design this entrance at ground level to avoid the requirement for descending a great number of stairs either immediately outside or inside the entrance.

5.3.7. Providing Natural Light and View

The lack of natural light and view is, both psychologically and physiologically, the single greatest concern related to underground space. With the exception of warehouses and buildings with other functions where human habitability and acceptance is a secondary concern, some natural light is desirable in virtually every type of building. The degree to which this is necessary or even desirable for each space in the building depends on the specific function. In a building composed mainly of small, continuously occupied spaces, such as private offices or hospital patient rooms, the entire form of the structure

Design Consideration

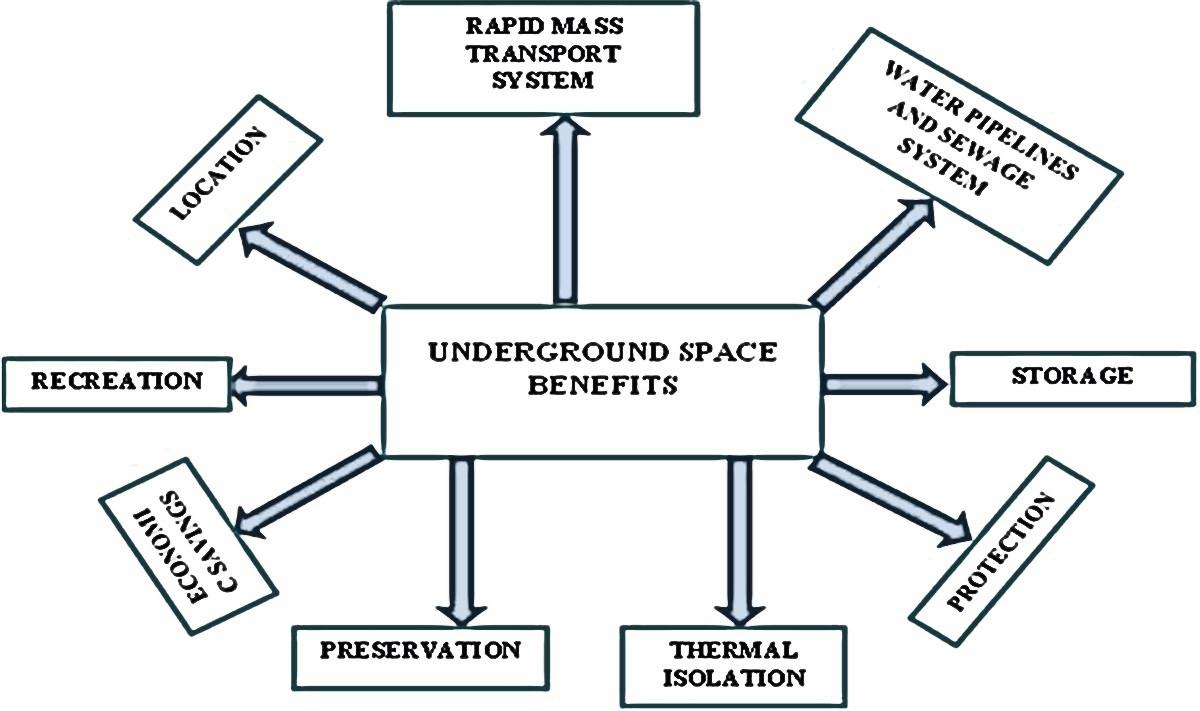

may be shaped by the need for natural light and view. In buildings with functions that are suitable in windowless spaces-classrooms, auditoriums, and exhibition spaces, for example-it may be necessary or desirable to provide natural light and exterior view only to corridors and lobby areas, thus giving the designer greater flexibility. Although designers employ many variations and combinations of techniques, there are only a few basic approaches to providing natural light and exterior view to below-grade spaces. Aside from the functional needs of the spaces, the techniques selected for introducing natural light and view to a particular building are influenced by the site topography as well as the size and depth of the structure. On a sloping site, conventional vertical glazing can be used for the spaces on one side of the building. This approach by itself is capable of providing light and view only to the spaces on the building perimeter. If earth berms are placed around a Figure 3.1.4. Potential of underground space structure on a flat site, conventional vertical glazing can be provided on the building perimeter by creating openings in the berms. For interior spaces on a sloping or flat site, natural light and view can be provided by creating courtyards. If a courtyard must be deeper to serve several floors, it must also be larger in area in order to permit sunlight to reach the floor of the courtyard and create the perception of looking outdoors. The view into an exterior courtyard is usually more focused and limited than a view through the building perimeter, making the landscape design of the courtyard a critical concern. On flat sites, the use of skylights is a common technique for introducing natural light to at least the upper level of an underground structure. In many cases horizontally glazed

Design Consideration

skylights actually provide more natural light than a vertically glazed window, but the same opportunities for exterior views are, of course, not available. Consequently, skylights alone may not be considered an adequate substitute for conventional windows. Some designers used sloped glazing in courtyards or light wells; this glazing provides natural light from overhead while permitting exterior views from some angles. An alternative to creating an exterior courtyard is an interior courtyard with skylights overhead. In large and deep buildings, an interior courtyard provides additional climatecontrolled space and, like an exterior courtyard, natural light from above. The extent to which a view of an interior courtyard is a substitute for an exterior view depends a great deal on the size and design of the space. The use of glass walls between an interior courtyard and the spaces surrounding it is a common technique for transmitting light and view to these spaces. Referred to as "borrowing light," this concept is used in many ways to provide natural light to spaces that are adjacent to spaces that have direct access to light-for example, from a skylight, perimeter window, or courtyard. In addition to the approaches discussed above, some other novel techniques for introducing natural light and exterior view to subsurface spaces have been developed. With the increasing awareness of the advantages of underground buildings for a variety of functions, BRW Architects, Inc., of Minneapolis, Minnesota, has experimented with various optical techniques for providing or enhancing the effect of natural light and view in normally windowless areas. Mirrors can be used to enhance the light and view from a window by reflecting them into spaces not immediately adjacent to the window. Another approach is to provide exterior views using mirrors and lenses in a manner similar to a periscope. In one of the simplest applications, a pair of mirrors was used to provide views to below-grade offices in the Fort Snelling Visitor Center in Minneapolis. A more sophisticated periscope-type system using mirrors and lenses provides a clear exterior view for a lobby area 110 ft beneath the surface in the Civil and Mineral Engineering Building at the University of Minnesota. In the same building, two separate systems are used to provide natural light to different areas. One system uses heliostats on the roof to collect sunlight, which mirrors and lenses then project to the offices in deep mined space below. The other system appears to be a more conventional skylight over the main laboratory space, but reflective surfaces and lenses are used to collect, concentrate, and project the sunlight to the space below more efficiently and accurately. These various optical techniques not only permit greater design flexibility for all underground buildings, but also enable light and view to be introduced to deep subsurface spaces or below-grade spaces on very constrained sites where conventional approaches do not work.

Design Consideration

5.3.8. Interior Design

A key element of the impression created by any building; interior design is critical in occupied underground structures. In addition to the normal concerns of creating an attractive interior environment, special attention must be paid to offsetting the potentially negative psychological effects discussed earlier- claustrophobia, lack of view, loss of orientation, lack of stimulus, and associations with dark, damp, or cold basements. Interior design, however, has little impact on any of the potentially negative physiological effects of underground spaces. Since opportunities to introduce natural light and view are often limited, the interior spaces must be designed to maximize the effect of what light and view there are and to compensate for the lack of light and view in other areas. A number of techniques are used in underground buildings to create a feeling of spaciousness that helps to offset claustrophobia and provide more visual stimulus in the absence of exterior views. Wider corridors and higher ceilings than normal, together with open plan layouts using low partitions, are simple means of creating a spacious feeling. In addition, glass partitions can be used between spaces to provide spatial relief and variety. Perhaps the most effective approach is the use of large, multi-level central spaces surrounded by smaller spaces. Overlooking large spaces from balconies offsets the feeling of being below grade and can provide vistas nearly equivalent to exterior views, even if the central spaces are not naturally lighted. In addition to providing variety within the building, large interior courtyard-type spaces can also help to give building users a reference point in maintaining their orientation. Although the size and arrangement of interior spaces are critical elements in the perception of an underground building, the more subtle elements of color, texture, lighting, and furnishings cannot be overlooked. In an environment that lacks outside stimuli, variation in lighting and color in particular can simulate some of the variation that would occur with natural light. Well-lighted, brightly colored surfaces, with an emphasis on warmer tones, can help to offset associations with cold, dark underground spaces. One characteristic of windowless space that can be used as an advantage is the lack of distraction, which enables manipulation of the interior design to focus the occupant's attention if desired. Dramatic

5.3.9. 360 UNDERGROUND SPACE

lighting can effectively draw attention to artwork, for example. In buildings with interior courtyards or central spaces, plant materials, fountains, and other landscape elements can create a simulated outdoor environment without natural light. Although this approach has been achieved in windowless spaces with some success, there is always the danger that imitation of conventional above-grade spaces in a superficial way- false window frames with painted exterior views, for instance- will leave a negative impression. Rather than working to create an acceptable environment within