4 minute read

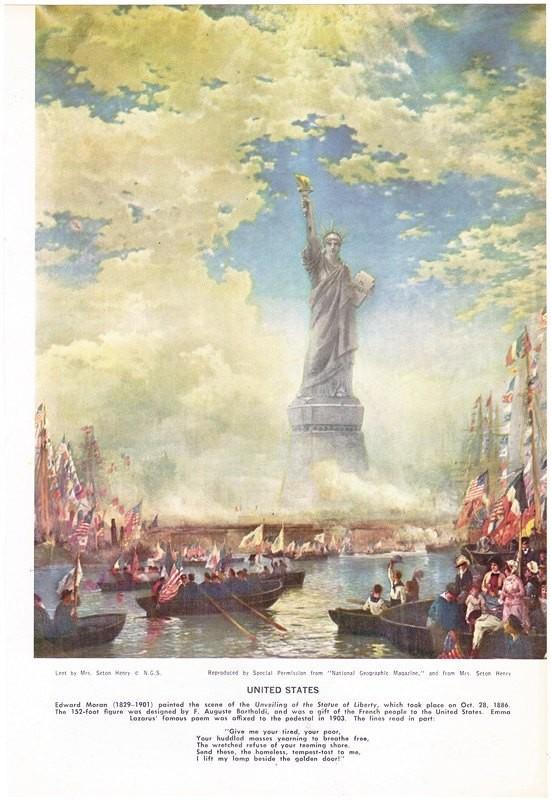

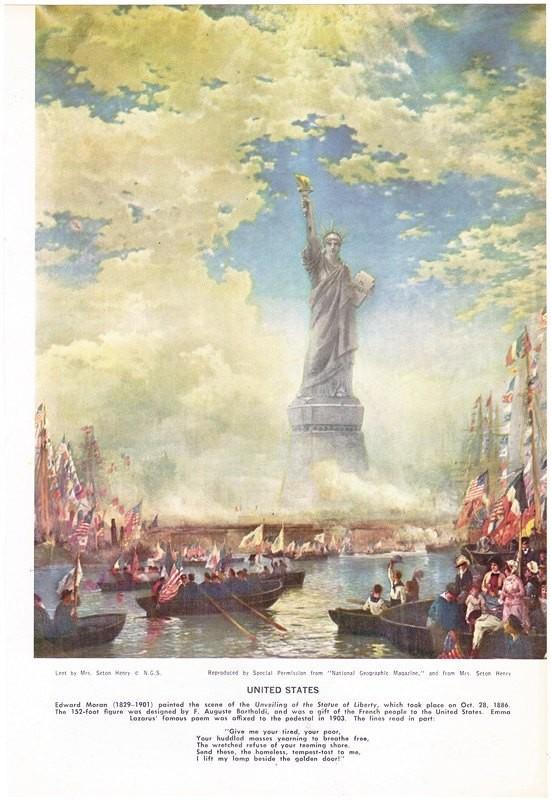

The American Reception of theStatue

from Statue of liberty

by Saba Naz

Bartholdi had received a favorable reaction to the idea of the Statue when he first visited the United States in 1871. In 1875, when the Franco-American Committee was founded, a few Americans endorsed the project. The following year, inspired by Bartholdi's second visit, on which he exhibited a schematic of the finished Statue of Liberty , and coincident with the display of the hand and torch in Philadelphia and New York, the American Committee was formed, principally to finance and arrange for the construction of the pedestal. The Committee's first effort was to convince Congress to accept the French gift, offer a suitable site, and provide for future maintenance. Authorizing legislation to these ends was passed in early 1877, and Fort Wood, a recently decommissioned military battery on Bedloe's Island, in upper New York Harbor, the site which Bartholdi preferred, was the location chosen. When

Bartholdi announced, in July 1881, that the Statue would be completed in 1883, however, relatively little money had been raised for the pedestal. Among the factors that discouraged contributions were artistic and religious criticisms, dissatisfaction with the proposed location, a tendency in other parts of the Nation to view the project as a New York City affair, anti-Statue editorials in some leading newspapers (including several in The New York Times), and dissatisfaction with the thought of the United States paying for the pedestal.

Advertisement

Plans for the pedestal, by architect Richard Morris Hunt, were available in late 1881. They indicated that 9 months would be required to erect it and that the cost would far exceed original estimates. The Committee continued its efforts with modest success and decided to begin work with the funds on hand. Ground was broken for the foundation in April 1883, and it was completed in May 1884. Adding to the financial burdens of the Committee were unexpected difficulties in excavating for the foundation within the walls of old Fort Wood, within which the Statue was to be erected, and design changes in the pedestal. Early in 1885, only preparatory work had been done on the pedestal itself. The Committee was $100,000 short of its goal, and had to halt construction. The Committee renewed its appeals, soliciting the public, the New York legislature, and the U.S. Congress, all to little immediate avail. The situation was embarrassing because the completed Statue had already been presented to the American Minister in Paris, and was being readied for shipment to New York. The individual who galvanized the public into raising the money required to complete the pedestal was Joseph Pulitzer, owner-editor of The (New York) World. In March 1885, Pulitzer renewed the newspaper crusade he had begun on behalf of the "pedestal fund" in 1883. He re-emphasized the national and egalitarian nature of the project, railed at the wealthy of New York for their lack of generosity, and appealed to the "working masses" to make up the deficiency in the fund.5 The participation of the French public was also held up as an example.

A factor that may have spurred the success of Pulitzer's special fund was the offers made by other American cities (Philadelphia, Boston, Cleveland,

Minneapolis, San Francisco, and Baltimore) to provide a home for the Statue.

Pulitzer's fund, however, was a phenomenal success in any case. Between March and early August 1885, more than 120,000 people donated in excess of $100,000 to the fund. (The largest individual contributions were two in the sum of $1,000 by Pulitzer himself and Pierre Lorillard, a prominent tobacco merchant of French descent; small donations came from thousands of schoolchildren and many people of modest means. The World printed the names of all contributers.)

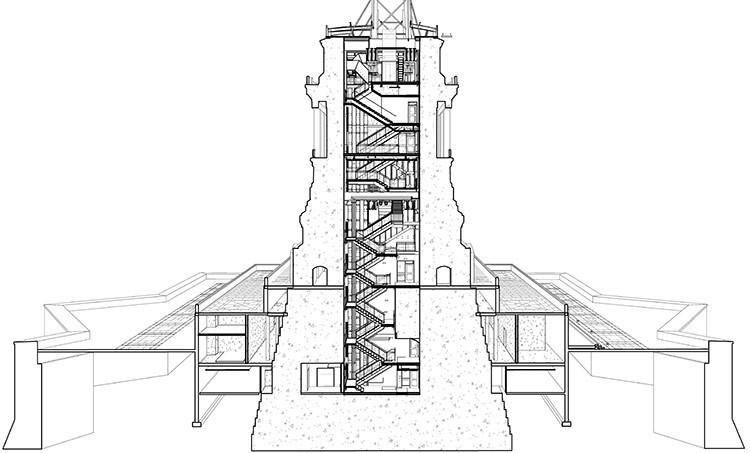

Pulitzer's success had, meantime, in mid-May, permitted the Committee to resume work on the pedestal. At that point, only 8 of its projected 46 courses of masonry were in place. In June the Statue arrived, and provided an additional impetus to the fundraising drive. Pedestal construction proceeded quickly thereafter, and was completed in April 1886. The complicated task of reassembling the Statue consumed the summer and early fall of 1886. The island’s fortifications were previously designed in the shape of an 11point star. Renowned architect Richard Morris Hunt was commissioned to design the pedestal, which ended up 89 feet tall, after budget reductions.

Hunt’s design included a truncated granite pyramid with Doric portals, cornice and base in the neoclassical style. It was meant to represent the triumph of Liberty over Europe’s old ways.

Doric portals an 11-point star truncated granite pyramid

Artists and architects

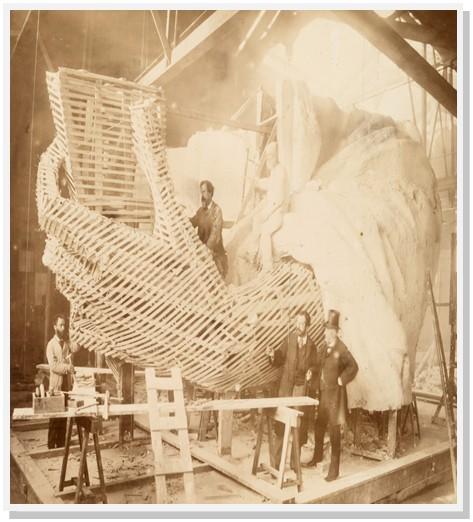

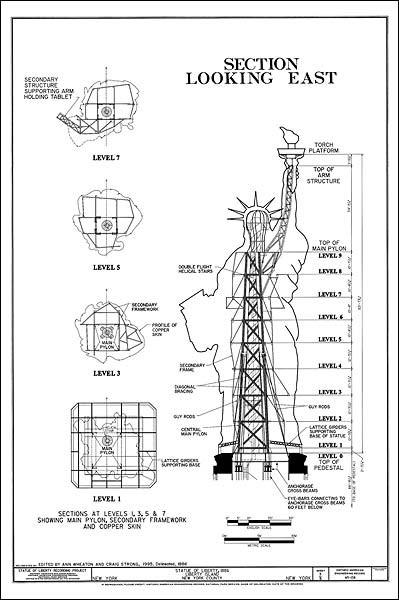

Meanwhile, back in Paris, Bertoli had started construction in 1875. During initial work on the head and arm, Bertoli had consulted with the great French architect Viollet-le-Duc who helped design structural issues. After Viollet-le-Duc died in 1879, Bertoli turned to Alexandre Gustave Eiffel as the structural engineer– who had revolutionized the way bridges and viaducts were designed, but not yet conceived of the Eiffel Tower. Ten years after he began, Bertoli was finished with the statue. In 1885, it was disassembled and crated for its voyage overseas to New York. It barely stayed afloat through a terrible storm, but arrived with fanfare in New York. Of course, the base ,which was begun in 1883, was unfinished and work had stopped due to funding shortages. At this time, they were still building the Capital and the Washington Monument was yet unfinished. But the arrival in New York of the French Steamer Isère with the crated statue, gave the final impetus for fundraising and the base was completed the next year. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead assisted in readying the grounds of the island. A ceremony of dedication was held on the afternoon of October 28, 1886 with President Grover Cleveland. There were hundreds of boats covering New York Harbor.

A quarter-scale bronze replica of Lady Liberty was erected in Paris in 1889 as a gift from Americans living in Paris. It is 35 feet tall and was built on a small island in the River Seine, just south of the Eiffel Tower.

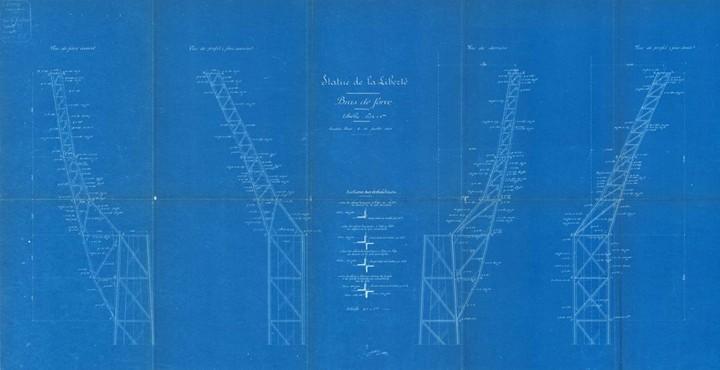

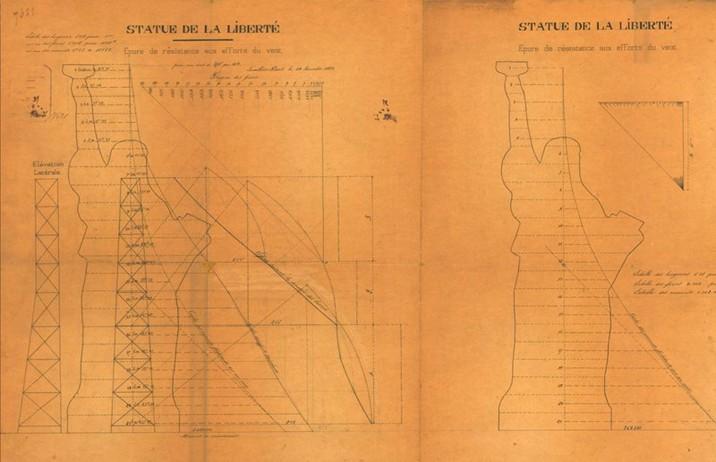

Blueprints of statue of liberty the plans of the statue’s upraised arm

A sketch showing details of the hardware required to attach the statue’s iron support skeleton to its concrete pedestal