Chief Executive Officer

Megan N. Schagrin, MBA, CAE, CFRE mschagrin@saem.org

Director, Finance & Operations

Doug Ray, MSA, dray@saem.org

Manager, Accounting Edwina Zaccardo, ezaccardo@saem.org

Director, IT

Anthony "Tony" Macalindong, amacalindong@saem.org

IT AMS Database Specialist

Dometrise "Dom" Hairston, dhairston@saem.org

Specialist, IT Support Dawud Lawson, dlawson@saem.org

Director, Governance

Erin Campo, ecampo@saem.org

Manager, Governance

Juana Vazquez, jvazquez@saem.org

Coordinator, Governance

Demetrius Pritchett, dpritchett@saem.org

Director, Communications & Publications

Laura Giblin, lgiblin@saem.org

Sr. Manager, Communications & Publications

Stacey Roseen, sroseen@saem.org

Manager, Digital Marketing & Communications, Alison “Ali” Mistretta amistretta@saem.org

Specialist, Web and Digital Content Alex Gorny, agorny@saem.org

Sr. Director, Foundation and Business Development

Melissa McMillian, CAE, CNP mmcmillian@saem.org

Sr. Manager, Development for the SAEM Foundation

Julie Wolfe, jwolfe@saem.org Manager, Educational Course Development

Kayla Belec Roseen, kroseen@saem.org Manager, Exhibits and Sponsorships David Perez, MSMC, dperez@saem.org

Director, Membership & Meetings

Holly Byrd-Duncan, MBA, hbyrdduncan@saem.org

Sr. Manager, Membership George Greaves, ggreaves@saem.org

Sr. Manager, Education

Andrea Ray, aray@saem.org

Sr. Coordinator, Membership & Meetings

Monica Bell, CMP, mbell@saem.org

Specialist, Membership Recruitment

Krystle Ansay, kansay@saem.org

Meeting Planner

Kar Corlew, kcorlew@saem.org

AEM Editor in Chief

Jeffrey Kline, MD, AEMEditor@saem.org

AEM E&T Editor in Chief

Susan Promes, MD, AEMETeditor@saem.org

AEM/AEM E&T Peer Review Coordinator Taylor Bowen, tbowen@saem.org aem@saem.org, aemet@saem.org

Monday - Thursday: 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. CT; Friday: 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. CT Phone: (847) 257-SAEM (7236) or email: saem@saem.org

Ali S. Raja, MD, DBA, MPH President Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School

Michelle D. Lall, MD, MHS President-Elect Emory University

Pooja Agrawal, MD, MPH

Jody A. Vogel, MD, MSc, MSW Secretary-Treasurer Stanford University

Wendy C. Coates, MD Immediate Past President

UCLA Department of Emergency Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

Members at Large

Yale Department of Emergency Medicine

Jeffrey P. Druck, MD

University of Utah School of Medicine

Ryan LaFollette, MD

University of Cincinnati

Julianna J. Jung, MD , MEd Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Nicholas M. Mohr, MD, MS University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine Ava Pierce, MD UT Southwestern Medical Center,

Thriving

The Growing Impact of Asynchronous Care in

A Traditional EM Career Path Not the Best Fit? Consider a Telehealth Fellowship!

88 Toxicology

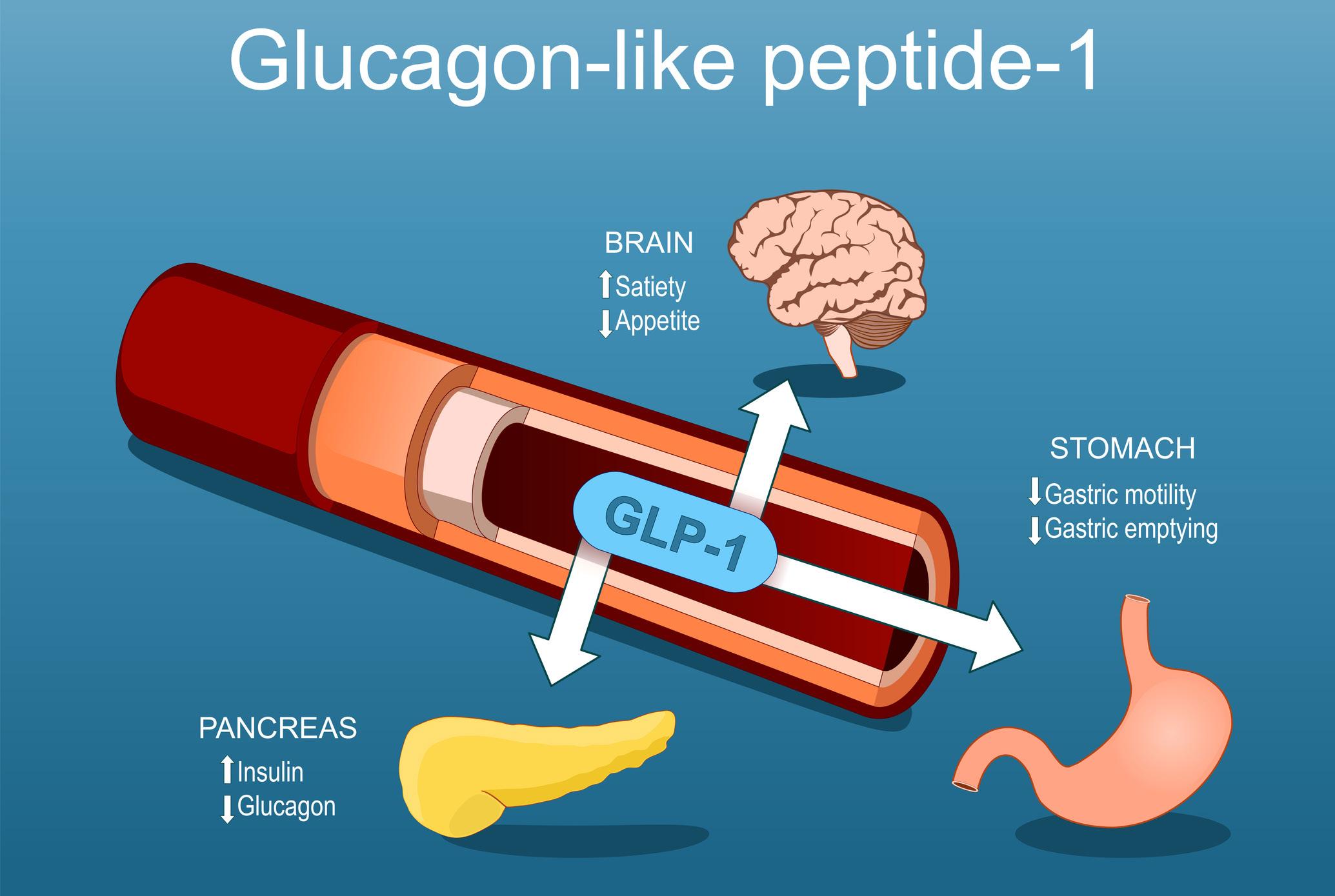

Navigating the Rise of GLP-1 RA Exposures: What Emergency Physicians Need to Know

92 Understanding the Pharmacology, Treatment Challenges, and Aftermath of the Ghouta, Syria Sarin Attack

94 Voices & Viewpoints

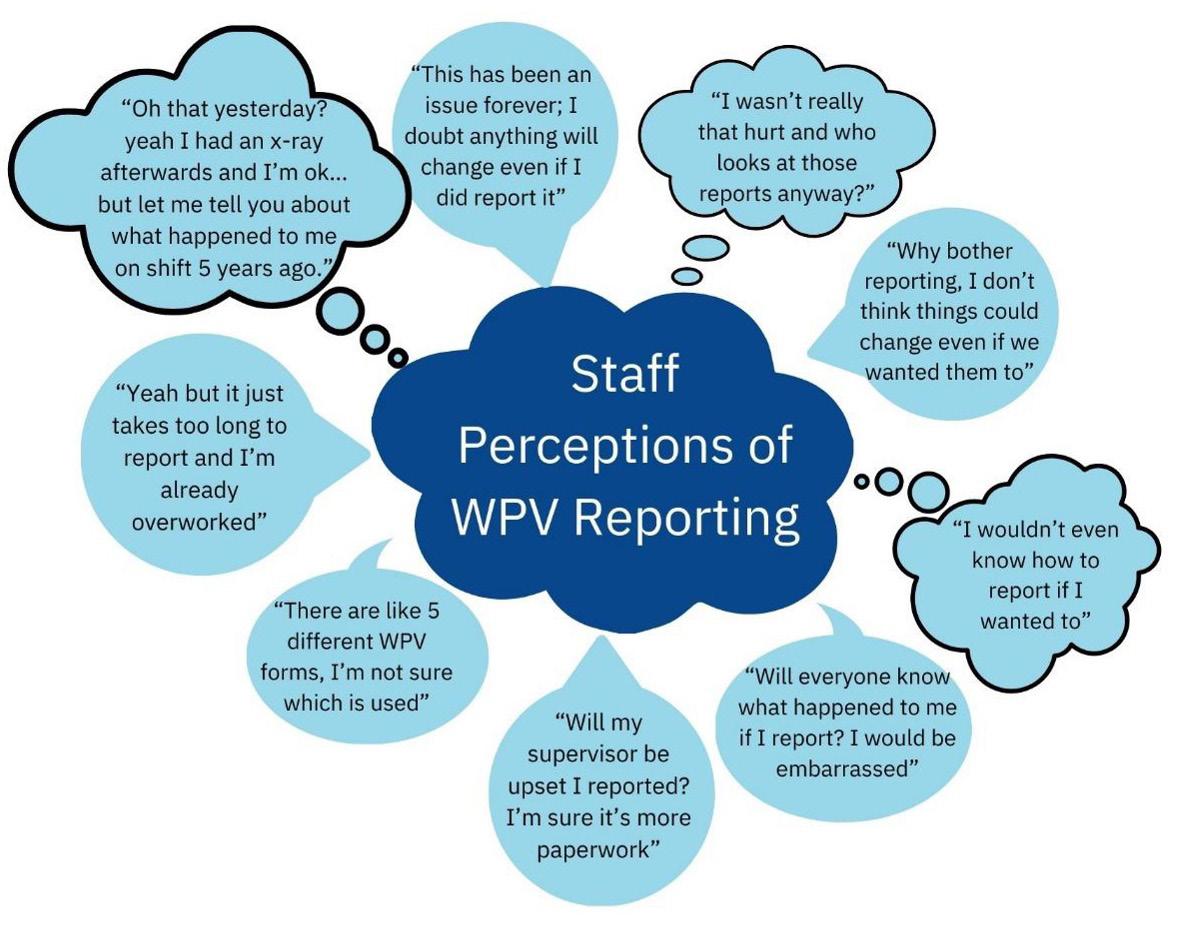

The Legacy of Eugenics in Standardized Testing and Its Impact on Diversity in Emergency Medicine 96 The Pass/Fail Step 1 Shift: Implications for Underrepresented Emergency Medicine Bound Medical Students 98 Wellness Addressing Workplace Violence in Emergency Medicine: Bridging the Gap Between Reporting and Reality

Wellness Reflection Burnout in Emergency Medicine: Observations From a Future Physician

104 Wilderness Medicine Rising Search and Rescue Incidents Highlight Need for Enhanced Wilderness Medical Training 106 Women In Academic EM Careers by Design: Achieving Self-Promotion Without Being Seen as a Self-Promoter 108 Discover What You Might Have Missed: Top Publications From AWAEM

“Your support and camaraderie have been invaluable to me, and I am deeply grateful for it.”

Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts General Hospital 2024-2025 President, SAEM

SAEM has always felt like a family to me. I’ve met some of my best friends within our organization and have relied on them through thick and thin, seeking advice on everything from COVID-19 protocols to parenting. It’s always seemed so mindboggling to me that all of you — amazing academics focused on emergency medicine — also make time to build strong relationships and do so many remarkable things outside of the hospital. Your support and camaraderie have been invaluable to me, and I am deeply grateful for it. Connecting with everyone — from our most senior leaders to our medical students and residents – has meant the world to me and been my favorite part of SAEM.

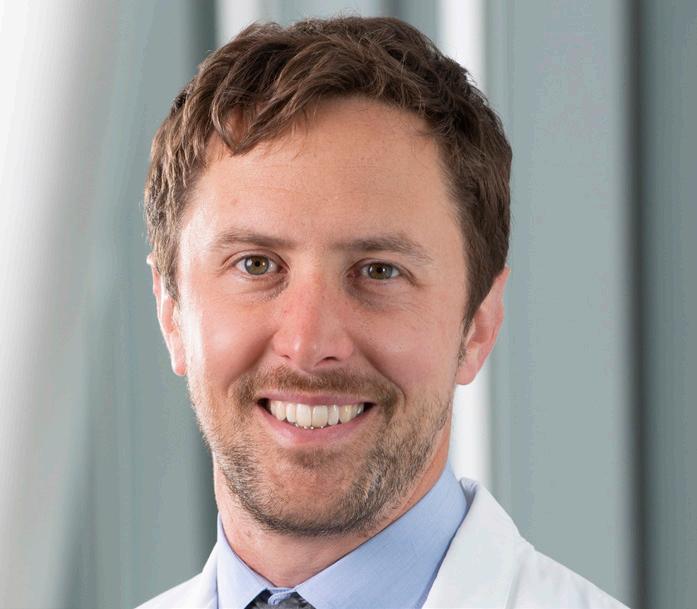

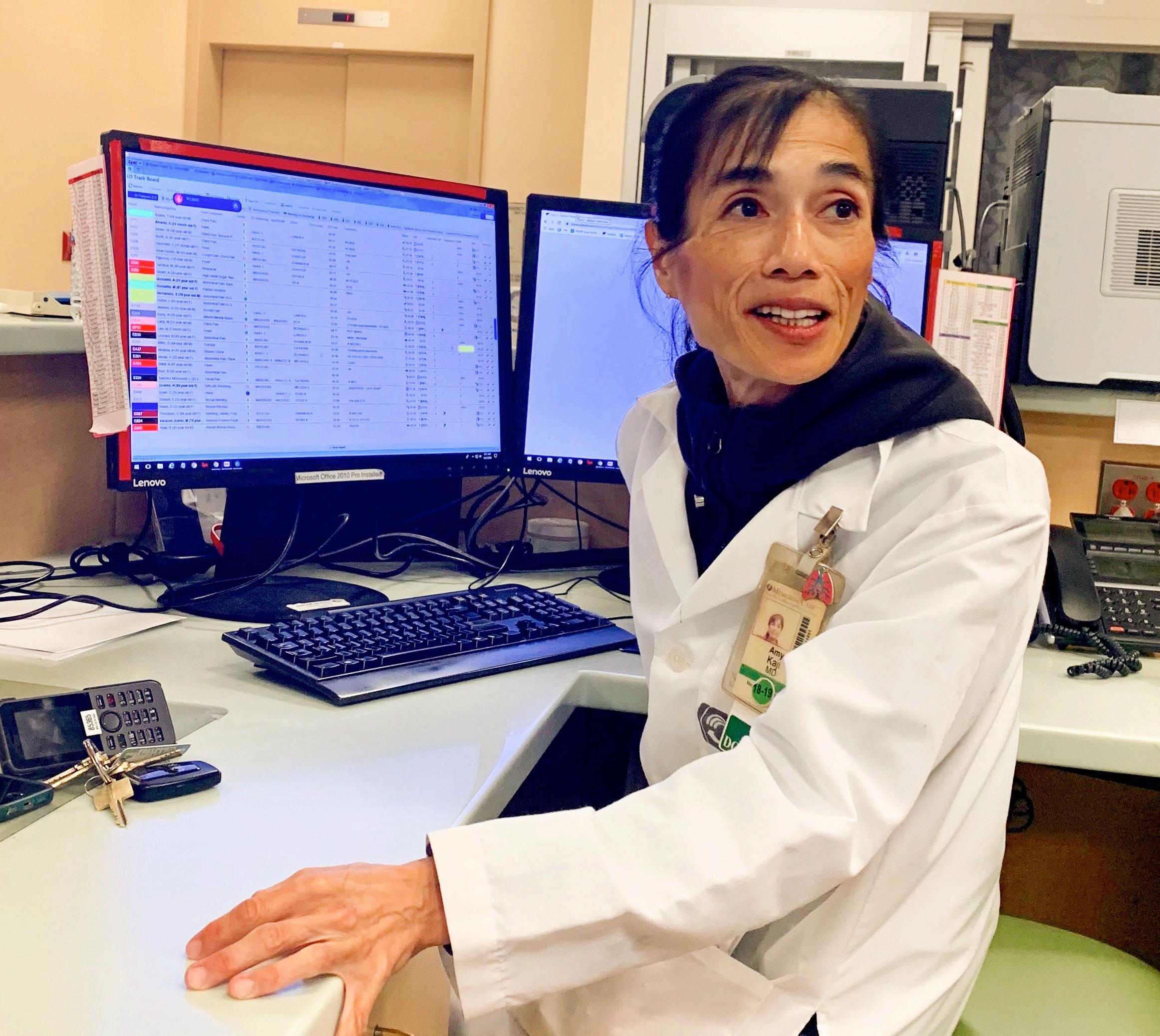

So it was with a heavy heart that I recently learned of my dear friend Dr. Amy Kaji’s passing. I had known Amy for a couple of decades, but we really got to spend time together when we both joined the SAEM Board about ten years ago. She was impossible not to love. Somehow, she had done all the things in academic emergency medicine — from serving as SAEM President to editing Rosen's Emergency Medicine and achieving the rank of professor at UCLA, among too many other achievements to list here — and yet still found time to support her friends and family. Conversations with her were never superficial; she wanted to know what was happening outside of work, took the time to know Danielle and our boys, and shared her own struggles with a vulnerability that I’ve tried to emulate. Even when I last spoke to her a few weeks before her death, she found a way to focus the conversation on me instead of everything she was going through. Amy had a huge heart, and I

know many of us will always miss her immensely.

Amy was known for many things, including her leadership abilities and research skills. She was also an awardwinning educator and mentor, and one of the things she enjoyed most about being on the SAEM Board was our connection with the RAMS (Resident and Medical Student) Board. So, I know she’d be just as excited as I am to read this month’s profile on our RAMS President, Dr. Emily “Ly” Cloessner. She’s another fantastic leader, and she and the RAMS Board will have an amazing year, building off all their successes from last year.

Finally, I wanted to briefly mention the great meeting that we recently had with the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities last month in Bethesda. Megan Schagrin, Melissa McMillian, Jody Vogel, MD, and I met with them and Jeremy Brown, MD from the National Institutes of Health Office of Emergency Care Research. We discussed several potential collaborative opportunities, and I am excited about the possibilities that lie ahead. I hope to share more details with you soon.

In the meantime, please enjoy this month’s Pulse – I know Amy would have loved reading about the fantastic work being done by everyone in this organization that she loved so much!

ABOUT DR. RAJA: Ali Raja, MD, DBA, MPH, is a professor of emergency medicine at Harvard Medical School and the deputy chair of the department of emergency medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Member-at-Large, 2024-2025 SAEM Board of Directors

Associate Professor, Assistant Program Director, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Cincinnati

Dr. LaFollette is SAEM Board Liaison for the following SAEM Groups:

President: Petra Duran-Gehring, MD Overview

AEUS, the largest community of educators and researchers in emergency ultrasound, is dedicated to the education and development of the emergency medicine ultrasound network.

• Provided scholarship funding for the ARMED program (Arthur Broadstock, MD, University of Cincinnati, and Jacob Schoeneck, MD, Wake Forest University) and ARMED MedEd (Rebecca Theophanous, MD, Duke University).

• Presented several awards, including the AEUS Innovation Award, which supports pioneering advancements in emergency ultrasound, and the AEUS Medical Student Ultrasound Enthusiast Award, which funds attendance at the SAEM annual meeting. AEUS also sponsors multiple SAEMF AEUS Research Grants.

• AEUS facilitated a highly successful Grant Writing Mentorship Program, led by Dr. Frances Russell, offering grant writing support and instruction to AEUS members. In the 2023-2024 cohort, nine mentees participated, with one receiving a SAEMF grant, two securing foundational grants, and two others funded by EMF.

• SonoGames24 was the largest event yet, with 105 resident teams participating!

Special thanks to the SonoGames Organizing Committee and the 90+ member volunteers for making it a success. We look forward to an even bigger event in Philadelphia in 2025!

• The AEUS Narrated Lecture Series has been updated with five new courses, including four on regional anesthesia and one on traumatic pneumothorax, along with eight updated courses.

• Probing the Literature is a monthly ACEP/ SAEM National Ultrasound Journal Club available to academy members, covering two articles each month.

Chair: Nancy Kwon, MD, MPA

The Faculty Development Committee is charged with creating resources and education to further the career opportunities of academic emergency physicians and to act as a central resource for academic career advancement.

• Presented seven didactics at SAEM24, in collaboration with AACEM, AWAEM, the Simulation Academy, and the Education Committee.

• The updated Academic Career Guide will soon be available on the SAEM website.

• Developing a toolkit and pathway for junior and mid-career faculty.

• Planning a webinar on the diverse career options in and beyond emergency medicine, covering topics such as career transitions, retirement, and alternative job opportunities.

• Collaborating with AWAEM to support faculty with promotion letters and guidance through the promotions process.

• Continuing the development of the Who’s Who in Academic Emergency Medicine podcast.

Chair: Joshua Joseph, MD, MS, MBA

Overview

The ED Administration and Operations Committee has the task of advancing the unique operations and administrative challenges of the academic emergency department. It does this by monitoring trends and new opportunities in the space and providing educational resources and

community in several outputs online and through the annual meeting.

• Updated the Asynchronous Operations Curriculum on SOAR

• Sponsored an SAEM24 didactic on operationalizing an operations curriculum in conjunction with the education committee

• Working on an educational series about artificial intelligence and its applicability to administration and operations

• Developing a webinar on the impact of boarding in the emergency department

Chair: Dustin Williams, MD

Overview

The Membership Committee is tasked with helping recruit and engage the SAEM membership. Through a regular survey, the committee makes recommendations responding to the trends and directions of the membership and encourages member involvement through communications and onboarding.

• Created a membership survey, to launch in September 2024, which will be used to change SAEM programming in the years to come

• Achieved record membership and attendance at the SAEM Annual Meeting

• Analyzation and implementation of the 2024 Membership Survey findings

• Engagement of residents and medical students through regional and national meetings

Chair: Erin Kane, MD, MHPE

The Emergency Medical Services Interest Group was established to identify and address the educational needs of EMS providers and their learners by offering educational sessions at the annual meeting and updating ongoing EMS curricula.

• Identifying positions for section membership to have a greater involvement in SAEM EMS IG development and works

• Unifying the EMS fellowship list offerings between societies for more consistently up to date information

• Working with the National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP) Education Committee to develop EMS curricular development updates, scholarly activity offerings, and mentorship opportunities for EMS-bound learners

• Working with RAMS to develop an annual EMS Fellowship webinar for interested applicants to receive updates and explore opportunities in EMS scholarly activity

• Exploring opportunities for further collaboration across national societies and institutions for broader EMS exposure for non-fellowship trained providers to participate in work that improves prehospital care in critical access and underserved communities

Chair: Raghu Seethala, MD

Overview

The Critical Care Interest Group aims to promote emergency medicine-critical care (EM-CC) physicians at the local and national levels by recognition and engagement in leadership development activities. The Critical Care IG also creates a forum and community for mentorship, education and operations in the varied environments of EM-CC.

• The group sponsored two didactics at SAEM 24 on the topic of critical care in the era of boarding and co-sponsored a didactic with GEMA on resuscitation education in resource-limited settings

Works in Progress

• The interest group is exploring crowdsourcing methods to gather comprehensive data sets on critical care boarding across member institutions, with a focus on better quantifying its impact.

Chair: Jennifer Mitzman, MD

Overview

The Pediatric Emergency Medicine Interest Group is tasked with promoting pediatric emergency medicine as a career path within emergency medicine. This is achieved through didactic presentations, enhanced research integration, and increased fellowship support.

Notable Accomplishments

• Sponsored a didactic on the complexities of managing pediatric behavioral health crises in the era of boarding

Works in Progress

• The Pediatric Interest Group and its growing membership is striving for Tier

III interest group status through rigorous education and mentorship structure

• Increasing research visibility by permitting the concurrent acceptance of abstracts at adjacent conferences, thereby enhancing the presence of Pediatric Emergency Medicine at our annual meeting

Daniel N. Jourdan, MD, NRP

Resident Member, 2024-2025 SAEM Board of Directors

Chief Emergency Medicine/Internal Medicine

Resident, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit

Dr. Jourdan is the SAEM Board Liaison for the following SAEM groups:

Chair: Amanda J. Deutsch, MD

Overview

The Wellness Committee is actively engaged in addressing emergency physician wellness and resilience, primarily by building a knowledge hub of resources, tools, and models focused at both the individual and organizational levels.

• Organizing the 3rd Annual Stop the Stigma EM Month this October. Focused on addressing the stigma surrounding mental health and accessing support, the event last year included collaboration with 14 national and international EM organizations.

• Significant contributor to SAEM24, including 6 didactics, the annual storytelling evening, and a workshop on wellness tools that drive change.

• Piloted the first-ever Wellness Consultation in collaboration with the SAEM Consultation Services Committee.

Next meeting: September 12, 3 p.m. CT

Co-chairs: Alyssa Valentyne, MD, Gayle Kouklis, MD

Overview

The Climate Change and Health Interest

Group focuses on the impact of climate change on public health, specifically within emergency medicine. Group efforts include research, advocacy, and education regarding the impacts of climate change and opportunities to mitigate its effects within the house of medicine.

• Over the past year, published multiple SAEM Pulse articles in addition to multiple presentations and didactics at SAEM24.

• Currently collaborating with ABEM to create board (re)certification questions based on the latest climate health research.

• Focused on publishing multiple SAEM Pulse articles and submitting didactics to SAEM25.

Next meeting: September 26 at noon, CT

Co-chairs: Nicholas Stark, MD, Zaid Altawil, MD, and Jonathan Oskvarek, MD, MBA

Overview

The Innovation Interest Group seeks to inspire and foster collaboration among innovation-minded emergency physicians to share ideas on applying design thinking and emerging technologies to help solve the challenges of today and the future in the health care system.

• Increased membership to 200+

• Hosted a didactic at SAEM24 focused on utilizing design thinking to find solutions to challenges in psychiatric emergency medicine.

• Collaborating with other SAEM Interest Groups on webinars: “AI in the ED” and “Telehealth in EM”

Chair: Katherine Dickerson Mayes, MD, PhD

Overview

The Neurologic Emergency Medicine Interest Group seeks to enhance research, education, and patient care in all areas of acute neurological emergencies, including traumatic brain injuries, stroke, epilepsy, and intracranial hemorrhages.

• Interest group members actively participate in multiple trials, including ICECAPS and BOOST.

• Planning for multiple didactic submissions for SAEM25, including new guidelines for the care of traumatic brain injuries and intracranial hemorrhages.

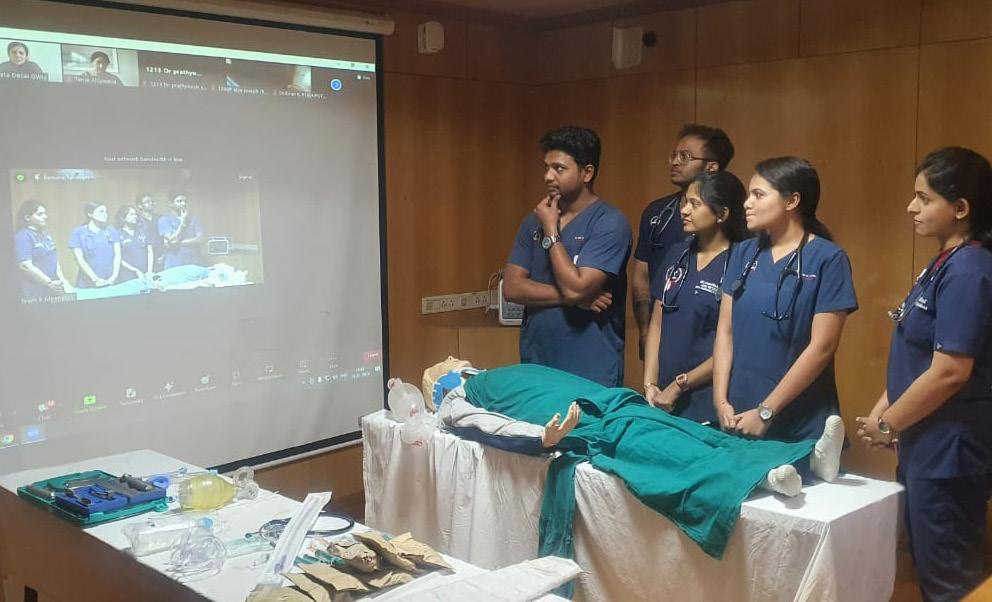

Emily “Ly” Anne Cloessner, MD, MSPH, is a current PGY-4 and chief resident at Washington University in Saint Louis. Her path to emergency medicine (EM) began with a career in public health and public service, driven by a commitment to community service. As a fellow at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), she developed domestic vaccine policy, contributed to the Global Ebola Vaccine Implementation Team’s guidance on Ebola vaccine use, and supported CDC international offices during infectious disease outbreaks. Her work earned her multiple awards from agencies within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Dr. Cloessner earned her medical degree from the Medical University of South Carolina and completed her undergraduate studies at the College of Charleston. She received her master's from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. In her work with SAEM, she has served as a member-at-large on the RAMS board from 2023 to 2024, as the RAMS board liaison to the research committee since 2023, published several Pulse articles with the research committee, and currently chairs the nominating committee. She is also active in the SAEM Global Emergency Medicine Academy and has helped organize the World Health Organization Basic Emergency Care Training of Trainers course at the SAEM Annual Meeting for the last two years. Dr. Cloessner is the 2024-2025 president of the SAEM RAMS board.

Congratulations on your election as the new president of RAMS. What are your primary goals for RAMS during your term?

Thank you! I’m so excited to be leading our RAMS Board this year. I couldn’t ask for a more talented group of people to be working with.

My primary goal is to help RAMS engage fully with their membership. RAMS has experienced tremendous growth over the past two years and, with over 5,200 members, now makes up more than half of SAEM’s total membership. Given this influx of new members, I want to ensure that all RAMS are empowered to become active members of SAEM. I believe that engaging with SAEM academies and committees and using our SAEM Career Roadmaps can connect any RAMS member to the experiences they need to advance their career in emergency medicine. Our RAMS board is working hard to make these connections possible.

What issues do you feel are most relevant to current and future emergency medicine trainees? What steps do you hope to take toward addressing these issues during your tenure as RAMS president?

Emergency medicine trainees have faced several challenges in recent years. The job report of 2021 and the subsequent SOAP of 2022 have changed the perceptions of our specialty among EM-interested medical students. For residents committed to EM, the influence of private equity in our job market and upcoming changes to how residents will be evaluated in residency and boarded thereafter are sources of ongoing anxiety.

These issues have fundamentally changed what it means to be a trainee in EM. EM residents and EM-interested students now come from a broader application pool. Additionally, recent Match and SOAP data show that many current trainees may not have originally planned on EM as their specialty. As RAMS president, I see it as my job to help all RAMS, especially those struggling to find their niche, connect with experiences that will help them build fulfilling careers. To this end, the RAMS board will continue revising our career roadmaps, engaging with our workforce committee, and stepping up our membership engagement efforts to assist all our RAMS in creating successful careers in emergency medicine.

When, why, and how did you first become involved with RAMS?

I attended my first SAEM meeting in my first year of residency. My program did not have a strong presence in global health, so my program director sent me to the annual meeting and told me not to return without a research mentor. Together, we put together a list of sessions for me to attend, including the Global Emergency Medicine Academy’s (GEMA) World Health Organization (WHO) Basic Emergency Care Training of Trainers course (which I have since helped organize), the GEMA meeting, and several research presentations. At the annual meeting, I not only found a research mentor, I discovered a whole community of academic emergency physicians who were just like me. I knew I had found my academic “home” with these physicians, who remain my mentors. I can’t speak highly enough about the

continued on Page 8

people in GEMA: Dr. Torben Becker, who has been endlessly available to me; Dr. Kyle Martin, who has helped me prepare for fellowship applications; and the fine folks who have let me help organize the WHO course the past few years. It’s a wonderful group to grow with and learn from.

My positive experiences with GEMA led me to seek further involvement with SAEM. As a resident, RAMS seemed like the logical place to start. With the encouragement of my mentors, I ran for the board in the 2022-2023 year and served as a member-at-large on the RAMS board last year. This past year, I was encouraged to run for the presidency and was successful in that election.

Why should EM residents and medical students become involved with RAMS? What needs does the group meet or concerns does it address?

The beauty of working in a specialty that sees any patient, for any reason, at any time, is that there is also a place in emergency medicine for any academic interest you can imagine. Through its academies and committees, SAEM offers myriad experiences for RAMS members seeking mentorship or career-building opportunities. Particularly for those in residency programs or schools with smaller research communities, engagement with SAEM can help fill gaps in resumes and prepare members for the next stage of their careers. I found the mentorship and research opportunities I needed for my fellowship application through SAEM, and I believe other RAMS can find the same.

What upcoming RAMS initiatives excite you?

More than any single initiative, I’m excited about the overall growth in our RAMS membership and the expansion of activities from the RAMS board. This year, our board is operationalizing its strategic plan and working to build greater connections between our board and SAEM academies, as well as developing partnerships with other national EM organizations. We have increased our involvement with the workforce committee, continued our work with #StopTheStigmaEM, and are updating the RAMS career roadmaps. These efforts have already yielded promising results. I get immense joy from hearing how RAMS members have become more involved at the national level, connected with new research mentors, or published research with colleagues they met through SAEM. These are the fundamental experiences that build community in our specialty. I’m proud of the work the board has done to facilitate these experiences for our members.

Who or what influenced your decision to choose the academic/EM specialty and if you were not doing what you do, what would you be doing instead?

I came to medicine after a career in public health, which directly influenced my choice of emergency medicine as my specialty. EM physicians are at the forefront of every epidemic and public health issue facing America. On any given day I might treat patients who are victims of gun violence, COVID, traffic accidents, or the opioid crisis. It therefore probably comes as no surprise that if I were not in medicine, I would likely still be at the CDC, working to reduce the risk of people experiencing health-related emergencies.

Any tips on surviving, perhaps even thriving, during residency?

I have two tips:

First, embrace wherever you find yourself. I’m in Saint Louis, and I love it here. Where else can one find this caliber of training, along with a local Taco Bell Fitness Course? (I’m not kidding.) Keeping a sense of curiosity about your new home can make residency more enjoyable.

Second, pare down. Training significantly limits your free time. Being honest with yourself about what is important academically and personally will ensure that valuable time is well spent. For me, this has meant saying yes only to research that aligns with my goals and makes sense for me and focusing my external commitments within SAEM, while allowing other opportunities to pass by.

Tell us about your dream workday.

My dream workday involves being in our trauma and critical care pod, where our sickest patients are treated. I get in a few thought-provoking and successful resuscitations. Drinks and sandwiches at the Gramophone, our usual hangout, follow afterward.

What are your research and/or academic interests?

I am interested in the intersection of larger public health issues and the emergency department, both in the United States and globally. I am particularly concerned with infectious disease cases, especially vaccine-preventable ones, that result in emergency room visits. My overall career goal is to maximize community-level interventions to prevent the progression of these diseases to epidemic levels and create emergency room protocols for outbreaks if these preventative measures fail.

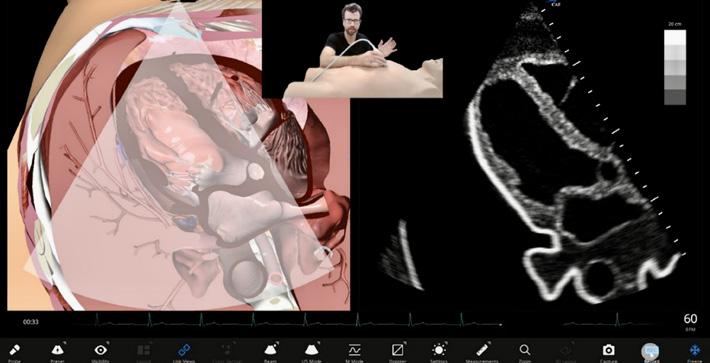

I am also engaged in work with point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), particularly its application in settings with limited resources. I’m a member of GEMA’s new POCUS subcommittee and work with the Global Health Coalition Corporation, teaching POCUS globally. Much of my current work that is nearing publication is related to my POCUS interests.

October is #StopTheStigmaEM month. Stigma is a leading barrier to mental health care for emergency physicians. Many fear that treatment for mental illness could jeopardize their careers or licenses to practice.

What do you consider the key challenges to addressing this stigma?

This can be a sensitive area for trainees, and I’m proud of RAMS’ ongoing involvement with the #StopTheStigmaEM campaign to reduce stigma around seeking mental health care within our community. Overall, there are positive signs of change within the medical community regarding this issue. While many jokes have been made about mandatory wellness modules, the fact that ACGME now has requirements for trainee wellness was a crucial institutional step in acknowledging the mental health needs of physicians. Many programs, including mine, now provide multiple mental health resources beyond what ACGME mandates.

However, addressing stigma within our community is not enough. As negative perceptions around mental health issues change within the medical field, we find ourselves in a situation where the culture of medicine is ahead of its licensing entities. For example, in Missouri, my licensing application asks, “Do you currently have any condition or impairment which in any way affects your ability to practice in a professional, competent, and safe manner, including but not limited to: (1) a mental, emotional, [or] nervous…. disorder?” As long as licensing applications continue to include such questions, physicians will worry that seeking necessary health care may negatively impact their career trajectory. Ultimately, resolving the stigma around mental health care requires all parties to be on the same page regarding physicians seeking care.

What can be done to create a sense of safety for EM physicians and medical trainees that would encourage them to ask for help or self-report when they’re struggling with their mental health.

As mentioned, creating a sense of safety for physicians to seek mental health care will come from acceptance, both inside and outside the medical community, that physicians have the same health care needs as everyone else. More immediately, I encourage trainees who are struggling to reach out to a trusted mentor if they are unsure how to access the confidential resources available at their institution.

What is one thing you can't do without while on shift?

Snacks. I’m infamous for needing a constant supply of food on shift.

What is your “go to” work/on-shift hack?

I learned this tip for caring for trauma patients from my co-resident, Emilie Lothet: if you need to irrigate a head laceration and don’t want to make a mess, cut down a side of a basin and rest the patient’s head through the opening. The basin will catch the irrigation fluid, and you can use a Yankauer to prevent any overflow.

What is a favorite FOAMed resource?

Derangedphysiology.com

What would most people be surprised to learn about you?

I triple majored in college. I have a bachelor of science in psychology and in chemistry, along with a bachelor of arts in art history. I put serious thought into whether I would pursue a career in art preservation.

Who would play you in the film of your life and what would that film be called?

The medical classic, “The House of God” needs a sequel. Let’s call it “Take Your Own Pulse” (rule 3 in the original book) and put in an ensemble cast from everyone’s favorite medical TV shows. Can Katherine Heigl play me?

What is your guilty pleasure?

I never feel guilty about taking time for myself or for the health of my mind and body. I’m currently enjoying caring for my summer garden and catching concerts in town.

What is at the top of your bucket list?

Easy! Refreshing my SCUBA certification before my elective rotation in Hawaii. It turns out there are several places you can dive around Missouri, so I should get this done before the year’s end!

Who would you invite to your dream dinner party?

An unfortunate consequence of medical training is that residency and then fellowship matching have dispersed my friends across the country. My dream dinner party brings all of us back together for an amazing home cooked meal.

SAEM mourns the loss of our former President Amy H. Kaji, MD, PhD, a compassionate leader, cherished colleague, and beloved friend. Dr. Kaji passed away on August 1, 2024 at the age of 56. She touched countless lives through her unwavering dedication to emergency medicine and her deep commitment to SAEM.

At the time of her passing, Dr. Kaji was Senior Advisor for Academic Development at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and a Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. SAEM extends its deepest condolences to her family, friends, trainees,

colleagues, and all those who had the privilege of working with and learning from her.

Dr. Kaji's medical career was marked by exceptional brilliance and dedication. A Harvard College graduate, she earned her medical degree from Thomas Jefferson Medical College. Her extensive training included an emergency medicine residency and research/disaster medicine fellowship at Harbor-UCLA, where she also completed an MPH and a doctorate in epidemiology from UCLA School of Public Health.

Dr. Kaji authored hundreds of published works and was a methodological

and statistical editor for Annals of Emergency Medicine and JAMA Surgery. In addition, she edited the 9th edition of Rosen's Emergency Medicine and co-authored the first edition of the study guide, Emergency Medicine Board Review. Her three-book series, The Kaji Review, remains a valuable educational resource for emergency medicine students, residents, and attending physicians.

A renowned and respected educator, Dr. Kaji was the recipient of the ACEP National Faculty Teaching Award and the UCLA Distinguished Lecturer Award.

Beyond her professional achievements, Dr. Kaji was a cornerstone of SAEM,

exemplifying selflessness and dedication throughout her 22 years as a member. In addition to chairing several committees, Dr. Kaji was a devoted member of the SAEM Foundation Board of Trustees from 2014 to 2023 and served on the SAEM Board of Directors from 2013 to 2023. As the 2021-2022 Board President, she guided the organization with vision and resilience through the challenges of the post-COVID world, helping to shape its future and strengthen its mission.

Dr. Kaji’s unwavering belief in the power of collaboration and teamwork for the greater good was evident in every aspect of her life. Whether mentoring

young physicians, chairing committees, leading SAEM, or providing care during the pandemic, she fostered a spirit of unity and cooperation, always prioritizing the recognition and promotion of others over herself. Her humility and modesty were hallmarks of her character, and she touched countless lives through her kindness.

Dr. Kaji’s beautiful soul, warm smile, and enormous heart will be deeply missed by all who knew her. As we remember Dr. Kaji, we find solace in her own words, which encapsulate her character and the legacy she leaves behind: “[At the end of my career] I would like to be remembered

as being a thoughtful, dedicated emergency physician, teacher, and team player.”

Amy, you will be remembered for all this and so much more. Your legacy is woven into the fabric of our organization and the hearts of all fortunate enough to have known you. Rest in peace.

SAEM Foundation is accepting donations to support a special award in honor of Dr. Kaji. Donations can be made at saem.org/donate

By Hannah Mishkin, MD, MS; Lindsay MacConaghy, MD; Neha Raukar, MD, MS; Laura Walker, MD, MBA; and Wan-Tsu Wendy Chang, MD, on behalf of the SAEM Academy of Women in Academic Emergency Medicine

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly evolving and increasingly integrated into various aspects of our professional lives. In this series, we will explore how AI, particularly large language models (LLMs), can enhance efficiency in academic work within emergency medicine.

Introduction

AI enables computer systems to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence, such as problemsolving, learning, and reasoning. Essentially, AI uses advanced statistical methods to predict outcomes based on patterns in large datasets. This predictive capability is enhanced through neural networks — computer systems inspired by the human brain,

where data is processed through interconnected layers of "neurons" that adjust based on recognized patterns.

A specific type of neural network called transformers excels at handling sequences, such as sentences, by focusing on different parts of the data simultaneously. This allows them to understand context and generate coherent responses. These models are trained on vast bodies of text, known as corpora, which may include books, articles, and even social media posts, enabling them to process and generate natural language.

Among the most advanced AI tools available are LLMs such as ChatGPT, Copilot, and BERT. These models are

designed to understand and generate human language, making them valuable tools for both personal and professional applications in emergency medicine.

This article series will delve into various applications of LLMs in academic emergency medicine. We encourage you to explore using an LLM available through your institution or consider utilizing the free version of OpenAI’s ChatGPT 3.5, accessible at www.chatgpt.com

Getting

To begin using an LLM like ChatGPT, you’ll need to create a free account. Once your account is set up, you can interact with the model by asking it to perform tasks using everyday language.

For effective use, follow this three-step process:

1. Prompting: Clearly state what you want to create, including context about who you are and your intended audience.

2. Detailing: Provide a thorough description of the desired output. The more details you give, the closer the result will be to your expectations.

3. Revising: Review and provide feedback on the output. You might ask the LLM to shorten a speech, adjust the tone of an email, or refine the language used.

When interacting with LLMs, think of them as a helpful administrative assistant. Use conversational language, similar to how you would talk to a colleague, rather than a string of keywords. However, be mindful that LLMs operate in the public domain, so avoid including sensitive or private information.

Feedback is a crucial element of the learning process, especially in emergency medicine education. Delivering difficult feedback effectively requires careful attention to tone, timing, and context — areas where LLMs can offer valuable assistance. Consider this example of feedback:

“Learner X really needs to work on their attitude. They arrived five minutes late, missed some key findings on the physical exam, and when I provided feedback, they were defensive.”

Now, let's use ChatGPT to reframe this feedback to be more empathetic and constructive.

Step-by-Step Guide:

1. Open ChatGPT. Start by opening your ChatGPT interface.

2. Enter the Prompt. Input a clear and specific prompt, such as: "I have received some difficult feedback on a learner's performance. Please help me rephrase this feedback in a supportive way and suggest the best time and method for delivering it."

3. Input the Feedback. Copy and paste the feedback you received, ensuring that any identifying details are removed for privacy.

Here’s an example of a response generated by ChatGPT:

Supportive Feedback:

"Hi [Learner X], I’d like to discuss some observations from our recent shift together. First, I want to acknowledge the effort you’ve been putting into your learning and the progress you’ve made. It’s clear you’re committed to becoming a skilled clinician, which I greatly appreciate.

I noticed a few areas where there might be room for growth. For example, during our shift, you arrived slightly late and missed some key findings on a physical exam. I understand that shifts can be hectic, and these things happen to all of us at times.

When I provided feedback afterward, I sensed some defensiveness, which is completely understandable. Receiving feedback can be challenging, especially when we’re striving to do our best. My goal is to support your development and help you grow as a clinician. Feedback is a tool for growth, and I’m here to work with you through any challenges you might face.

Let’s discuss strategies to improve in these areas together, such as ensuring timely arrival, enhancing physical exam skills, and making feedback sessions more constructive. I’m here to support you every step of the way."

Refining the Output:

While this response is well-crafted, always review AI-generated content for accuracy and relevance. Adjust as needed to ensure it aligns with your intent. Additionally, consider how this feedback might be delivered — whether in person, via email, or as part of a remediation plan. The flexibility of LLMs allows for continuous refinement of communication strategies.

Conclusion

AI tools like ChatGPT enhance academic

“Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly evolving and becoming increasingly integrated into various aspects of our professional lives.”

emergency medicine by streamlining feedback, improving communication, and optimizing workflows. By integrating these technologies thoughtfully, we can elevate the quality of education and care we provide.

The authors would like to acknowledge the use of GPT-4, an AI language model developed by OpenAI, for providing editorial assistance and refining the manuscript.

Dr. Mishkin is the emergency medicine residency program director at Reading Hospital, Tower Health, in West Reading, Pennsylvania. Her academic areas of focus include innovation in medical education and administration, and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Dr. MacConaghy is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine and serves as the assistant residency program director at Guthrie Robert Packer Hospital in Sayre, Pennsylvania. Her professional focus includes advancing medical education and residency training.

Dr. Raukar is an associate professor and vice chair for academic advancement and faculty development at Mayo Clinic Rochester. Her research emphasizes life-threatening injuries in athletes, innovations in emergency medicine, and faculty and leadership development. She leads initiatives to cultivate the leadership skills of the next generation of physicians.

Dr. Walker is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Mayo Clinic. She is a leader in emergency medicine and hospital operations, focusing on health systems, equity, and quality improvement. Her research aims to improve healthcare systems and promote effective management practices within emergency medicine.

Dr. Chang is an associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Maryland. Her professional focus is on medical education and the management of neurologic emergencies.

By McRae Wood, Kristy Jones, and Cole Ettingoff, MPH, on behalf of the SAEM Behavioral Health Interest Group

Emergency departments (EDs) play a critical role by providing immediate care for psychiatric patients during crises. However, ensuring continuity of care post-discharge remains a significant challenge. Patients frequently revisiting the ED for behavioral health complaints add strain to patient loads and are at risk of bias. Effective strategies are essential to bridge the gap between acute ED care and ongoing communitybased mental health support. Several interventions and models have been studied and implemented to address this issue, aiming to reduce readmissions, improve patient

outcomes, and ensure a seamless transition to community care.

Critical Time Intervention (CTI) is a widely researched model designed to support psychiatric patients during the critical period following discharge from the hospital. This intervention is characterized by its time-limited, community-based approach involving three phases: Transition, Try-out, and Transfer of Care. In the Transition phase, intensive support is provided as patients leave the hospital, helping them adjust to life outside the institutional setting. During the Try-out phase, patients

begin to test their ability to manage independently while still receiving support. The final Transfer of Care phase involves gradually connecting patients to long-term community resources and services. (BioMed Central) CTIs have shown an overall improvement in patient outcomes by ensuring continuous care during the vulnerable transition period. Despite the challenge of maintaining caseworkers with small caseloads, local analyses of readmission costs and unreimbursed care demonstrate the financial value of such a model. Implementing CTI requires an initial investment in training

“Effective strategies are essential to bridge the gap between acute ED care and ongoing community-based mental health support.”

and resources yet offers a structured method to ensure psychiatric patients do not fall through the cracks during the critical post-discharge period, thereby decreasing readmission costs over time.

Various transitional care programs have been developed to enhance the continuity of care for psychiatric patients and reduce ED readmissions. These include the High Alert Program (HAP), which specifically targets patients at high risk of readmission by providing intensive follow-up and assistance with coordination of care. The PatientCentered Medical Home (PCMH) model focuses on a holistic approach to patient care, integrating mental health services within primary care settings. Lastly, the Collaborative Care (CC) Program involves

a team-based approach where primary care providers, care managers, and psychiatric consultants work together to manage patients’ mental health conditions. These models emphasize comprehensive, multidisciplinary services that incorporate behavioral and pharmacological strategies, case management, and coordination between inpatient and outpatient services. (MDPI) Robust partnerships with such programs may facilitate “warm” referrals, exchange health records, and open channels for patient information flow back to the ED, improving overall continuity of care.

Effective continuity of care often involves a multidisciplinary approach that includes a range of health care professionals.

Studies highlight the importance of involving case managers, social workers, pharmacists, and peer support volunteers in the care process. For example, case managers can ensure that patients attend follow-up appointments and adhere to treatment plans, while social workers can help patients navigate social services and access community resources. Pharmacists play a key role in medication management, ensuring patients understand their prescriptions and avoid adverse drug interactions. Peer support volunteers, who have lived experience with mental health conditions, can offer unique insights and emotional support to patients. This collaborative approach helps manage medication compliance,

continued on Page 17

continued from Page 15

provide emotional support, and connect patients with community resources, thereby reducing the likelihood of readmissions. Although multidisciplinary discharge planning is common in traditional inpatient settings, it is less common in EDs. Hospitals experiencing frequent prolonged ED boarding may need to create similar discharge planning processes to aid ED psychiatric patients.

EmPATH units offer a proven model of care delivery for acute psychiatric needs, helping keep ED beds open for medical emergencies by providing designated spaces for mental health crises. These units take medically cleared patients out of the chaotic ED and into community-styled open spaces, immersing them with psychiatrists or advanced practice providers who draft treatment plans. These units create a therapeutic environment that reduces the stress and chaos often associated with EDs, allowing patients to receive more focused and specialized care. They have also been shown to significantly improve patient satisfaction and outcomes by providing a bridge between the ED and long-term psychiatric care. If prolonged treatment is required, patients are transferred to inpatient psychiatry units. The success of EmPATH units underscores the importance of creating dedicated spaces for psychiatric care within hospitals, ensuring that patients receive the appropriate level of care without overwhelming the ED. Additionally, EmPATH units decrease ED boarding times, hospital length of stay, and psychiatric admission rates while improving outpatient follow-up visits and enhancing continuity of care following a mental health emergency. Initial funding for such units can be daunting, but public-private partnerships have made them possible in several states, improving ED revenue

Small changes in practice can significantly impact the delivery of care for patients with acute psychiatric concerns. Safety planning for the time immediately following discharge is crucial. The Coalition on Psychiatric Emergencies offers an ICARE2E toolkit for improving

care delivery, including tools for lethal means counseling, safety planning, and post-discharge caring contracts. Providing practical patient education on coping techniques, resources like the suicide and crisis hotline (988), and community crisis centers should be comparable to education provided for other common conditions, such as exercises for musculoskeletal injuries. Culturally sensitive patient education focused on specific, attainable tactics should be part of the overall discharge strategy to improve patient outcomes and lower the likelihood of behavioral health ED readmissions.

EDs often serve as the final safety net for patients who have fallen through other systems. While many impactful interventions for preventing acute psychiatric stabilization or ED revisits are upstream, EDs are uniquely positioned to offer invaluable data on unmet community needs related to psychiatric care. Such data can be valuable to public health and community partners, allowing ED leaders to advocate for patients beyond their walls. Establishing consistent primary care for psychiatric patients has been shown to improve continuity of care and reduce acute ED visits. By analyzing data on ED visits, hospitals can identify trends and gaps in community mental health services. This information can be used to advocate for increased funding, improved mental health services, and policy changes that address the root causes of frequent ED visits. EDs can also collaborate with local health authorities and community organizations to develop targeted interventions that address the specific needs of their patient populations.

EDs routinely provide patient education upon discharge for various diagnoses, yet behavioral health presentations may receive less support. Although chronic behavioral health conditions cannot be cured in the ED, the unique perspective and training of ED staff can greatly impact patients and their families. Acute crises present prime opportunities to educate patients on coping techniques and available resources like crisis hotlines and community centers. Culturally sensitive patient education focusing on specific, attainable strategies should be part of the discharge plan to improve outcomes

and reduce readmissions. For example, patients presenting with suicidal ideation may be provided with information on safety planning, coping strategies, and local mental health resources. ED staff can also offer guidance on recognizing warning signs of a mental health crisis and steps to take if those signs appear. By providing comprehensive discharge education, EDs can empower patients to take control of their mental health and reduce the likelihood of future crises.

(Cureus)

Ensuring continuity of care for psychiatric patients discharged from emergency departments is necessary for improving patient outcomes and reducing the burden on healthcare systems. Strategies such as Critical Time Intervention, transitional care programs, multidisciplinary approaches, EmPATH units, improved care delivery, and reinforced patient education have all proven effective in bridging the gap between acute care and ongoing assistance. Through collaborative efforts and the implementation of innovative care models, the healthcare system can better serve psychiatric patients, ultimately improving public health while reducing the strain on emergency services.

McRae Wood is an MD candidate at Trinity School of Medicine, Georgia, pursuing her passion for emergency medicine. She enjoys soccer, traveling, and spending time with her husband and new baby boy.

Kristy Jones is a fourth-year medical student at Mercer School of Medicine and aspiring psychiatrist with an interest in acute care. She was vice chair of the planning committee for the recent Symposium on Responding to Behavioral Health Emergencies.

Cole Ettingoff, MPH is a thirdyear medical student at Trinity School of Medicine in Georgia. He has a deep passion for all things EM, EMS, and public health and, among other roles, is a leader in the SAEM Behavioral Health Interest Group.

Ronny Otero, MD, MSHA; Neha P. Raukar, MD, MS; and Anthony Rosania, MD, MHA, MSHI on behalf of the SAEM Vice chairs Interest Group

Stepping into the role of vice chair presents an exciting opportunity that promises both challenges and rewards. It's a position that not only offers the opportunity to significantly influence your department but also provides a unique perspective on academic administration. As clinical chairs increasingly handle issues beyond the emergency department, including roles within medical schools, the expansion of emergency departments, and service on hospital committees, the vice chair’s role in managing modern academic emergency medicine departments has become increasingly crucial.

To fill these roles, a chair depends on the expertise of senior faculty members to advise on the increasingly complex landscape of departmental missions. A vice chair is usually appointed when an academic department has expanded in size and complexity to the extent that the chair needs additional support from senior faculty members with specialized expertise. These vice chairs might focus on specific areas such as research, operations, education, or clinical services, depending on the department's needs. Each vice chair brings a distinct skill set to the department, contributing to its overall

success. However, responsibilities and job descriptions can vary widely between institutions. Even if two vice chairs hold the same title, such as vice chair of research, their duties and expectations might differ based on the institution's priorities, resources, and structure. This diversity in roles means that your responsibilities as a vice chair can vary greatly from those of vice chairs in other departments or specialties. For example, while you might focus on advancing research initiatives, a vice chair in another department might be more involved in managing clinical operations or

“The vice chair role is fundamentally about supporting the chair and the department in achieving their goals.”

developing educational programs. Understanding these differences is crucial for effective collaboration across the institution and achieving departmental goals.

Vice chairs hold various specific titles, each focusing on different domains within an academic department. The SAEM Vice Chair Interest Group recently cataloged these roles, finding the most common titles to include:

1. Education: Oversees educational programs, including undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education. Responsibilities include curriculum development, ensuring teaching quality, and meeting accreditation standards.

2. Faculty Development/Academic Affairs: Focuses on faculty professional growth, including mentoring, organizing professional development workshops, and creating career advancement pathways. This role sometimes overlaps with education.

3. Clinical Operations/Clinical Affairs: Manages day-to-day clinical activities, including staff management, practice policies, and patient care quality and safety.

4. Diversity and Inclusion: Promotes a diverse and inclusive environment by developing strategies and programs to enhance diversity among students, faculty, and staff. This role may also include ensuring that care provided to various patient groups meets the

highest quality standards, measuring health outcomes for these populations, and offering education to faculty on caring for diverse patients. Additionally, this role might involve collaborating with recruitment committees to ensure that diversity is a key factor in hiring decisions.

5. Patient Safety and Quality: Dedicated to improving patient safety and care quality. Responsibilities include developing quality improvement initiatives, monitoring patient outcomes, and ensuring compliance with safety standards. This role is sometimes linked with the clinical operations role.

continued from Page 19

6. Research and Scholarship: Supports research activities by helping faculty secure funding, overseeing research projects, and ensuring high-quality research output. Unique among the roles, some departments find this role particularly challenging to fill.

While many believe that serving as a vice chair is a direct path to becoming a department chair, this isn't always the case. Some vice chairs are content with their current roles, focusing on their specific skill sets and supporting the chair. Additionally, with departments often having 5-10 vice chairs, it's not feasible for all to eventually become chairs. In some instances, a department may appoint an executive vice chair, who advocates for the chair, mentors other vice chairs or division heads, and occasionally acts as an intermediary when the chair is unavailable. The career progression from a vice chair role might lead to other domain-specific positions within the medical school or health system, rather than to a chair position.

The duties of a vice chair vary based on their area of expertise, but generally include supporting the chair in managing specific functions within the department. This can involve administrative tasks, vision setting, strategic planning, and representing the department in various capacities.

For example, a vice chair for education might be responsible for developing new training programs, overseeing the accreditation process, liaising between residency programs and midlevel residency or fellowship programs, distributing educational resources, and ensuring that that the educational needs of students and residents are met. They may also take part in faculty evaluations, curriculum reviews, and fostering partnerships with other educational institutions.

Conversely, a vice chair for clinical operations would focus on the logistics of running the department’s clinical services. This could include scheduling staff, managing budgets, ensuring compliance with health care regulations, and enhancing patient care processes.

A vice chair for diversity and inclusion might focus on recruiting a diverse faculty, creating mentorship programs for underrepresented groups, and leading workshops on cultural competency. They would also monitor the department’s progress on diversity goals and report on these to the chair and stakeholders.

While each domain is distinct and “triple threats” are uncommon, it is essential for each domain-specific vice chair to have a basic understanding of the roles and responsibilities of the other vice chairs within the department. Communication is key, especially where domains overlap, such as in clinical operations and quality. Clearly defining roles is important, but it cannot fully substitute for effective communication.

Most vice chair positions are found in academic departments with residencies and fellowships, though this is not always the case. The path to becoming a vice chair typically involves demonstrating excellence in your area of expertise, whether in education, research, clinical practice, or another

domain. Candidates are typically senior faculty members who have demonstrated leadership skills and a strong commitment to the department's goals. They often have a proven track record of achievements, such as published research, successful teaching programs, or enhancements in clinical practices.

Medical directors and other leaders aspiring to vice chair roles can benefit from mentorship, both from their chair and other vice chairs. Transitioning from a director to a vice chair presents unique challenges and opportunities, making understanding these differences crucial for success and for feeling valued in the role.

The role of vice chair is demanding and time-consuming, requiring a careful balance between administrative duties and clinical, educational, or research responsibilities. It also involves collaborating with a wide range of stakeholders, including faculty, students, staff, and external partners.

A major challenge is effective time management. vice chairs often juggle multiple projects and responsibilities, which demands strong organizational skills and the ability to delegate tasks when necessary. Balancing daily role-specific tasks with pursuing growth opportunities can be particularly challenging, especially for those aspiring to future chair positions. In this context, mentorship from the chair and other senior members of the institution is crucial.

Another challenge is navigating departmental politics. As a vice chair, you may need to mediate conflicts, build consensus, and advocate for resources. This requires strong interpersonal skills, along with the ability to negotiate and compromise. You might oversee multiple director-level reports with overlapping responsibilities, and it's essential to help them understand their roles and expectations in relation to both the vice chair and, more importantly, the chair and the department. Despite the challenges, these mentorship and coaching opportunities can be among the most rewarding aspects of the position.

The role of vice chair is distinct in both culture and responsibility compared to that of directors in similar domains. While a director may enjoy greater autonomy in their day-to-day tasks, the vice chair often explicitly represents the chair. Therefore, alignment and constant communication with the chair are critical.

Despite the challenges, the role of vice chair is highly rewarding. It offers the opportunity to shape the future of your department, influence policy, and drive improvements. It also provides a platform for professional growth and the chance to work closely with other leaders in your field. As a vice chair, you have the unique opportunity to develop and implement strategies that can significantly impact patient outcomes, faculty development, and departmental efficiency. On a personal level, you can enhance your leadership skills, expand your professional network, and gain deeper insights into the administrative and strategic aspects of running a department. Collaborating with other leaders, both within your institution and in the broader field, allows you to work on innovative projects, share best practices, and contribute to the advancement of the specialty.

Before pursuing a vice chair position, it's important to evaluate whether the role aligns with your career goals and personal strengths. Reflect on what you currently enjoy in your role and what you hope to achieve in the future. The position of vice chair is more than just a meritbased promotion; it carries a significant responsibility for the overall success of the department. In many ways, it is a position of service — service to the chair in representing the department, and service to your direct reports through mentorship, coaching, and creating growth opportunities. This means that being "on mission" becomes vital, as your personal growth becomes more closely tied to the success of the department.

Consider whether you are prepared for the increased responsibilities and if you possess the necessary skills to excel in a leadership position. It may be helpful to seek advice from current or former vice chairs and chairs to gain a deeper understanding of the role and its demands. Additionally, consider applying for the SAEM Chair Development Program (CDP), a comprehensive leadership training initiative specifically designed to enhance the capabilities and effectiveness of new and aspiring academic emergency medicine department chairs. Through skill development, advising, and mentorship, the CDP prepares participants for the multifaceted responsibilities of departmental leadership.

Becoming a vice chair is a pivotal step in an academic career, offering a unique opportunity to significantly impact your department and advance your professional goals. However, the role comes with its own set of challenges and demands that require careful consideration

Understanding the specific duties and responsibilities associated with the vice chair role in your area of expertise is essential. Whether your focus is on education, clinical operations, diversity and inclusion, or another domain, being wellprepared and informed about what the position entails will set you up for success.

The vice chair role is fundamentally about supporting the chair and the department in achieving their goals. It involves leadership, collaboration, and building strong relationships — with the chair, partners and stakeholders, and your reports and faculty. Serving as a vice chair can be both fulfilling and enriching, offering personal and professional rewards while allowing you to play a key role in shaping the direction and success of your department.

Dr. Otero is the vice chair for clinical operations at Froedtert & MCW Department of Emergency Medicine, overseeing eight emergency departments throughout the enterprise. He is involved in strategic initiatives related to emergency care and improving the interface of admissions into the health system. He is also the co-director of the Health Executive and Administrative Leadership (HEAL) Fellowship for MCW Emergency Medicine.

Dr. Raukar is a clinician, researcher, and educator, serving as vice chair for academic advancement and faculty development at Mayo Clinic. She leads initiatives to cultivate the leadership skills of the next generation of physicians.

Dr. Rosania is the vice chair for clinical operations, associate professor of emergency medicine, and chief of the Division of Operations, Quality & Informatics in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Rutgers Health – New Jersey Medical School.

By Elizabeth Leenellett, MD, and Caroline Freiermuth, MD, on behalf of the SAEM Academy

for

Women

in Academic

Emergency Medicine, the SAEM Awards committee, and the SAEM Faculty Development Committee

The Emergency Medicine Program of Women in Leadership (EMPOWER) at the University of Cincinnati identified a critical issue among faculty members: Despite their impressive accomplishments and expertise, many women were reluctant to self-promote or advocate for recognition. This collective hesitation highlighted a broader challenge within academic medicine: navigating the complexities of career advancement in a competitive field where service, rather than visibility, is often the primary motivation. To address this, EMPOWER created an awards committee, which was later expanded to

include the entire department, aiming to foster a culture where achievements are celebrated, recognized, and leveraged for professional growth.

The awards committee was created to address three key objectives:

1. Building Internal and External Recognition: Enhance faculty visibility within the institution and in professional circles, thereby boosting their professional reputation and that of the department.

2. Facilitating Promotion and Career Advancement: Acknowledge the critical role of visibility and recognition in career progression, leadership opportunities, and overall professional development. Receiving awards builds credibility as an expert and can lead to invitations for collaborations or speaking engagements.

3. Teaching Self-Promotion Skills: Equip faculty with the skills to confidently articulate their accomplishments. Award nominations serve as an opportunity for faculty to practice. Rather than having the committee

“The establishment of an awards committee has proven instrumental in addressing the challenges associated with self-promotion and recognition among faculty.”

produce nomination letters, having faculty draft their own letters has proven more effective for self-advocacy.

Founded in 2019

EMPOWER established an awards committee to identify relevant awards and deserving nominees within its membership. A list of awards with nomination deadlines was compiled, including those from SAEM and the Academy for Women in Academic Emergency Medicine (AWAEM), American College of Emergency Physicians’ (ACEP) and the American Association of Women Emergency Physicians, Association of American Medical Colleges and the Group on Women in Medicine and Science (GWIMS), and institutional awards. Group discussions proactively identify women faculty and residents who meet the award criteria, selecting one candidate per award cycle. A champion is also

identified to contact the nominee, obtain their CV, and write a draft nomination letter based on the award criteria. The letter is then shared with the group, including the nominee, for edits. Success of this approach led to the committee’s expansion into an EM Departmental Awards Committee later that year.

An email is sent to the entire department to solicit interested members for the awards committee, aiming for broad representation. The committee currently has approximately 12 active members, including assistant, associate, and full professors, with an equal gender distribution. They meet for an hour each quarter to review upcoming awards and suggest nominees.

The committee is deliberate in evaluating all upcoming awards for potential candidates and ensures diversity

and inclusivity in nominations, fostering a supportive environment for all faculty members. When multiple candidates meet the award criteria, special consideration is given to those who identify as women or are underrepresented in medicine, prioritizing them for nomination. Those not chosen are prioritized for future cycles.

The committee also considers how many awards each person has been nominated for and works to ensure that new names are proposed. Experience has shown that awards often lead to more awards, as it is easier to adjust a winning nomination letter to meet an award criteria than to create a new one. Nearly half of our award winners have received multiple awards. Award nominations are tracked and have grown to include many subspecialty societies, incorporating the vast interests of the faculty group.

“By creating a supportive environment and providing structured guidance, the committee has significantly improved the visibility, recognition, and career advancement opportunities for the entire department.”

CASE IN POINT

continued from Page 23

One lesson learned was that the champions often wrote multiple letters for candidates they did not know well, resulting in considerable time and effort. Understanding the importance of creating compelling letters, combined with the short turnaround times needed to meet deadlines, led to some burnout. After consideration, it was recognized that no one knew their accomplishments better than the nominees. Additionally, reflecting on their journey and recognizing their achievements is an important process. Now, nominees are encouraged to draft initial letters highlighting their achievements and qualifications, tailored to the award criteria. To aid this process, a drive with prior submissions was created to serve as templates. Drafts are then refined collaboratively within the committee to ensure comprehensive and compelling submissions that align with award criteria and resonate with selection committees.

The committee has facilitated nominations for more than 200 awards at local, regional, and national levels across various categories. These efforts have resulted in faculty, residents, and advanced practice providers receiving over 100 prestigious awards, underscoring the effectiveness of the committee's success in highlighting talent, recognizing achievements, and enhancing professional visibility.

Public announcements of awards have increased both internal and external recognition of achievements. The nomination itself, regardless of the outcome, has often improved the individual’s sense of value and departmental recognition, which is key for job satisfaction and reducing burnout. Furthermore, adding awards and nominations to resumes has strengthened dossiers when being considered for

promotion, leadership positions, and job searches.

The culmination of these efforts aids in retention and recruitment, as a satisfied faculty speak volumes. Additionally, the nominations increase departmental academic stature. As other colleagues become more aware of expertise and prior accomplishments, they are more likely to serve as sponsors and promote other faculty members for opportunities such as invited speaking engagements and committees. Notably, the department’s commitment for promoting diversity, equity, and wellness within emergency medicine was recognized with the 2023 AWAEM Outstanding Department Award and the 2023 ACEP Wellness Center of Excellence Award, both of which were identified, and letters drafted, by the awards committee.

Through its journey, the awards committee has gleaned valuable insights:

While being nominated by the committee is affirming, he passive process did not significantly develop self-promotion skills. Encouraging faculty members to take ownership of their achievements and effectively communicate their qualifications has been pivotal. It is an opportunity to reflect on their career, recognize their achievements and boost confidence. Reviewing award criteria also helps them understand what success in that category looks like, which may help guide future career decisions. Self-nomination is more effective for developing self-promotion skills.

The committee refines the draft nomination letter from the candidate, changing language to active voice, adding superlatives, and highlighting the impact of the nominee’s achievements to maximize their chance of success. The result is an authentic, more targeted nomination, ultimately increasing the likelihood of a winning letter.

Nominees gain recognition from the award nomination, while committee members experience enhanced job satisfaction by contributing to their colleagues’ and the department’s success. This mutual benefit fosters a sense of community and well-being among both nominees and committee members.

The establishment of an awards committee has proven instrumental in addressing the challenges associated with self-promotion and recognition among faculty. By creating a supportive environment and providing structured guidance, the committee has significantly improved the visibility, recognition, and career advancement opportunities for the entire department. Moving forward, the committee remains dedicated to continuing its impactful work, empowering faculty members to confidently celebrate and share their achievements, thereby reinforcing a culture where excellence is celebrated, diversity is embraced, and professional growth is nurtured.

Dr. Leenellett serves as professor and vice chair of faculty affairs and inclusive excellence at the University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine, the W. Brian Gibler, MD, Endowed Chair for Education in Emergency Medicine, and chief of staff for UC Health-West Chester Hospital.

Dr. Freiermuth is an associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Cincinnati, where she holds the Shawn Ryan Endowed Chair to Benefit the Acute Treatment of Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders.

By Spencer Lord, MD, and Gregory P. Wu, MD, on behalf of the SAEM Critical Care Interest Group

Refractory shock includes both refractory cardiogenic shock and refractory distributive shock, often in the form of refractory septic shock. Refractory cardiogenic shock involves ongoing systemic hypoperfusion and end-organ dysfunction despite the use of two vasopressor/inotrope therapies and addressing the underlying cause. Refractory septic shock is characterized by persistently low mean arterial pressure despite adequate fluid resuscitation and high doses of vasopressors, typically norepinephrine ≥1 μg/kg/min. This condition may also involve septic cardiomyopathy with or without vasoplegia. This discussion will review the mechanisms, patient identification, risk stratification,

contributing factors, treatment monitoring, and briefly, patient selection for mechanical support devices.

Refractory septic shock occurs through multiple pathways. First sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction is driven by depressed TNF-α and IL-1β, leading to impaired cardiac contractility via nitric oxide and cyclic GMP suppression. Second, microcirculatory dysfunction causes dissociative shock due to mitochondrial damage, resulting in persistent vasoplegia. Third, systemic inflammatory shock involves widespread endothelial activation, coagulopathy, and blood flow dysregulation, leading

to further tissue hypoperfusion and persistent vasoplegia with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Finally, neurohormonal dysregulation occurs when there is a deficient response to vasopressin or impaired reninangiotensin-aldosterone system which exacerbates vasoplegia.

Refractory cardiogenic shock can perpetuate due to several causes. First is ischemia and myocardial dysfunction, a vicious cycle where worsening ischemia leads to less efficient myocardial function, increased oxygen demand, and continued worsening myocardial necrosis. This is the most common cause and becomes selfperpetuating. Second is the systemic

“Refractory cardiogenic shock involves ongoing systemic hypoperfusion and end-organ dysfunction despite the use of two vasopressor/inotrope therapies and addressing the underlying cause.”

inflammatory response, analogous to events in septic shock, with systemic proinflammatory response, coagulopathy, combined with microcirculatory dysfunction, and dissociative shock. Lastly is failure of oxygen utilization, where despite increasing oxygen delivery, the myocardium and peripheral tissues are unable to utilize oxygen.

Emergency medicine is focused on risk stratification, early identification of critical illness, and initiating management in this patient population. Therefore, we will discuss easy-to-use risk assessment scores to help tailor medical management or identify those who need mechanical cardiac support or transfer to an ECMO center.