7 minute read

Airline Partnerships

AIRLINE

PARTNERSHIPS

Advertisement

As an educational tool or refresher course to our readers, we run an occasional series of briefing articles to explain key aspects of the airline industry that often cause confusion. This month we provide an overview of the range of airline alliances, codeshares, partnerships and joint ventures.

THE GROWTH OF THE AIRLINE hub and spoke network model transformed the way Airlines serve their passengers in terms of the range of destinations on offer. However, due to the route limitations inherent in hub-and-spoke networks, airlines formed alliances to broaden their route networks beyond the restrictions of the hub-and-spoke model.

Alliances between airlines are as arrangements entered into between airlines to share routes, and to a lesser extent to share ground infrastructure such as booking systems and offices. The key advantages of such alliances are that the airlines can expand their route network and feed their own operated routes, thus achieving economies of scale.

Alliances also give airlines multiple options for routing passengers. One such example is ‘sharing metal’ – when a passenger flies on an alliance partner’s aircraft. This has become common practice globally and means that airlines need to provide pricing incentives that encourage people to choose certain routes over others. The airlines then decide on how to share the earnings equitably among the partners.

A key driver of alliances is the need to have tied, or dedicated, feeder routes to the hubs to connect longhaul services. In South Africa a good example of this are SA Express (While it operated) and Airlink airlines, which were both tied airlines to feed the SAA long-haul route network.

Alliances and partnerships between airlines have therefore become a necessary characteristic of the global air travel market. These partnerships cover a continuum from the most basic arms-length interlining agreements to joint ventures, and in the most complete sense, mergers involving equity partnerships. These partnerships and mergers are discussed in the following paragraphs.

THE HUB AND SPOKE MODEL

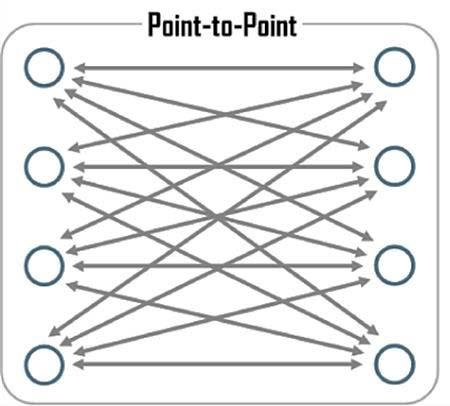

The hub-and-spoke model has come to dominate long-

haul air transport linkages, while the point-to-point model is the dominant paradigm for LCCs. This has had a number of consequences for African airlines:

First, the cost of establishing hubs is high and has created a natural barrier to entry for both airlines and their home states, which would be required to fund the hub development. Second, given Africa’s fragmented political landscape, it has proven difficult to achieve enough cooperation across states to agree on the location of a hub. This is particularly the case in west Africa, although east Africa has effectively developed two hubs, being Addis Ababa and Nairobi, while southern Africa has Johannesburg. (By way of anecdotal illustration of the difficulties of regional cooperation, despite the undesirable colonial legacy of the name Victoria Falls, Zambia and Zimbabwe cannot agree on an alternative name and so the original colonial name has endured.) Third, and perhaps most importantly to this discussion on alliances, the need to bulk-up traffic to feed the hubs has required regional airlines to cooperate in order to feed the hubs, so that they in turn can be fed by them. Lastly, Africa’s small, badly run and undercapitalised airlines cannot compete against the super-connectors.

It can be concluded that taken together, these factors have created an imperative for African airlines to form alliances with the large European or Middle Eastern carriers. The adage, ‘If you can’t beat them, join them’, is apposite in this regard.

sharing metal allows more flights and thus creates more traffic MERGERS As the hub-and-spoke model grew to dominate airline route structures, it became evident that size is important to airline success and that mergers became more commonplace. There are a many examples: The International Airlines Group (IAG), formed in 2011 by British Airways and Iberia; the KLM /Air France holding group; and the 2012 merger of Continental and United airlines in the USA. Of specific interest to Africa is the merger between two

smaller struggling South American airlines: Chile’s LAN and Brazil’s TAM airlines, which formed LATAM. This created the economies of scale and a route network large enough to enable the airline to be notably successful, with a consistent history of growth and profits since its establishment in 2011.

ALLIANCES

The current dominant structures created for partnerships are the three key airline alliances: Star Alliance founded in 1997, was the first and is still the largest, followed by Oneworld in 1999 and SkyTeam in 2000. The key characteristics of alliances are that member airlines pay dues to their chosen alliance, and then reciprocate benefits to other partner airline passengers. The key advantage for passengers is that they can expect consistent standards across the alliance, and shared benefits in loyalty programmes. These alliances permit airlines to coordinate their operations by ‘sharing metal’ and allows them to provide more flights and thus create more traffic, by placing their passengers on another airline’s aircraft. While the airline must naturally pay the other airline to carry their passengers, they retain a margin which is pure profit, and which avoids the cost of operating aircraft which are not full.

Alliances add value by using an agreed pricing strategy between alliance members to reduce fares between hubs. Contentiously for the competition authorities, the reduction in competition between hubs has a countervailing effect, in that the total surplus produced typically rises, suggesting that the positive effects of alliances may outweigh any negative impacts. AIRLINE PARTNERSHIPS

As noted, there is broad evidence that Africa’s

The Hub and Spoke model of air connectvity.

small, poorly managed and undercapitalised airlines cannot compete against the super-connectors. ‘Superconnectors’ is one of the terms used to describe the Gulf three middle-eastern airlines, namely Emirates, Etihad and Qatar, although Turkish Airlines is increasingly considered as one of the super-connectors. (The Gulf Three are also called the Middle East 3, or ME3).

The inability of small African airlines to compete against these very large carriers is evident in the extent to which the super-connectors are increasingly taking over routes to and within Africa, which formerly were operated by African-based airlines. Given the competitive airline hub-and-spoke distribution pattern that created the necessity of having tied feeder routes to support long-haul services, partnerships between airlines have become a necessary characteristic of the air travel environment.

INTERLINING

After the three alliances, interline agreements are the next broadest type of agreement between airlines. Interline agreements encompass a wide level of cooperation, as there are airlines that have interline agreements who do not otherwise partner. An interline agreement is an agreement between airlines to handle passengers when they are travelling on multiple airlines on the same itinerary. This makes it possible for passengers to check-in with their bags

all the way from departure point to their ultimate destination, possibly a number of sectors or legs, later.

CODE-SHARING

A codeshare agreement is an arrangement whereby an airline can sell seats under its own IATA identifier (or code) on another airline’s flight. Most major airlines have code-sharing partnerships with other airlines, and code-sharing is a key feature of airline alliances. The actual flight is operated by the ‘Operating carrier’ or more precisely (and in line with IATA definitions), the ‘Administrating carrier’, (abbreviated to OPE CXR). The shared ‘code’ in ‘code-sharing’ refers to the flight number’s two-letter IATA designator. Each airline sells seats on a specific flight under its own airline designator and flight number as part of its schedule. Code-sharing has become widespread in the airline industry due to the creation of the three large alliances and has the following advantages: a common flight number is less confusing as it allows a passenger to book from point X to Z through a hub at point Y on just one airline, and with just one payment. For airlines, it provides a vast increase in routes served without actually having to fly to those places. Of particular appeal to airlines is that when a passenger flies on a code-sharing partner’s aircraft, the margin paid to the booking airline is pure profit. For application to the African context with its continuing use of flag carriers, it is worth noting that code-sharing directly undermines the supposed benefits of having a flag carrier, as a state’s passengers could end up flying on a competitor’s aircraft. Also relevant to African operations is that buying a ticket on one airline and ending up flying on another airline (which may be perceived inferior or dangerous) is confusing and not transparent to passengers.