–LEARN TO SPIN!

• Jim: Fly by Night

• Boeing vs Airbus: 2024 wrap

• Embraer KC-390 finally for SAAF?

• Peter Garrison: Why do we turn left?

• Jannie Matthysen: A Day in the life of an O&G pilot

–LEARN TO SPIN!

• Jim: Fly by Night

• Boeing vs Airbus: 2024 wrap

• Embraer KC-390 finally for SAAF?

• Peter Garrison: Why do we turn left?

• Jannie Matthysen: A Day in the life of an O&G pilot

With increased headroom, larger windows, and spacious luxury seating, the PC-12 NGX gives you more space to work productively and arrive refreshed.

PILATUS CENTRE SA

Authorised Sales Centre

Sporadically,

over the

past

five years since Covid-19

(yes, it was that long ago) I have been writing about the long-awaited pilot shortage. So what happened to it?

IN 2021 THE NUMBERS were all good. Over 60% of the pilot workforce was expected to either retire or just leave aviation in the next five years.

Flying schools could not make new pilots fast enough, the air forces were training fewer pilots, and despite appeals, there was no yielding by the FAA on their 1,500 ATP hour rule for all Part 121 pilots.

This was all good news for aspiring pilots. The pilot shortage was predicted to reach critical levels in by 2025, driving up pay and working conditions as airlines compete to attract and retain pilots.

For nascent South African pilots the situation was particularly promising as senior pilots took off for greener – or sandier – pastures. Thus, it was expected that Airlink would lose around 100 pilots to foreign airlines in 2024. Just as in 2023 SAA lost 20% of the initial 87 pilots they

A former SAA captain, who was a casualty of Covid and Business Rescue wrote, “Almost every ex-SAA pilot who wants to continue flying is now flying for a foreign airline, so that supply has mostly dried up. Some have hung up their wings and either retired or gone into non-aviation careers or businesses.

“A global pilot shortage is anticipated to extend through at least 2032, with North America anticipated to feel the brunt of it as post-Covid demand exceeds new entrants.”

But the global shortage of pilots turned out not to be as bad as bad as everyone feared. The industry responded in various ways, most notably in the USA, where one of the more significant steps taken to ameliorate the loss of experienced captains is that the retirement age for regional pilots was pushed up to 67.

There was even talk of airliners flying as single pilot operations. Fear not. This will not happen anytime in the next ten years, and probably never.

The industry is nothing if not resilient. The pilot shortage seems to have been largely defused by these measures, increased throughput from the flight schools, and a tightening up of pilot working conditions – so that many are now finding themselves hitting the 100 hour/month limit. Further, South African flight schools are desperately short of instructors as many are being hired with very low time by the airlines.

What there has been is a significant shortage of air traffic controllers, engineers and ground staff due to layoffs, redundancies and forced retirements. But then who would want to work in the political snake pits that are ACSA and ATNS?

j

Day and night, the fun doesn’t stop!

Our catered camp site on the airfield means you won’t miss out on any of the activities – the early morning wake up call of P 51’s getting airborne, the evening ultralight parade, the STOL competitions and of course, the incredible night airshows! Plus all the camaraderie and fun only a camping group can offer.

Our campsite offers you a home from home at Oshkosh, tents and bedding, meals and beverages, charging facilities and sheltered seating – no camping gear required, bring only your clothes!

Tours depart Johannesburg, Durban or Cape Town Friday 18th July and return Tuesday 29th July 2024.

Prices from R40 650, Early Bird specials available!

SALES MANAGER

Kerry Matthysen sales@saflyermag.co.za 082 572 9473

CONTRIBUTORS

Morne Booij-Liewes

Laura McDermid

Darren Olivier

Jeffrey Kempston

TRAFFIC

Kerry Matthysen traffic.admin@saflyermag.co.za

ACCOUNTS

Bella Leitch accounts@saflyermag.co.za

EDITOR

Guy Leitch guy@saflyermag.co.za

ILLUSTRATIONS

Darren Edward O'Neil

Joe Pieterse

WEB MASTER

Emily Kinnear

StandardAero Lanseria, a Pratt & Whitney PT6A designated overhaul facility (DOF) and the sole independent DOF approved for the PT6A-140, is pleased to support operators across Africa with P&W’s flat rate overhaul (FRO) program, which combines OEM-level quality with guaranteed “not to exceed” capped pricing. Meaning that you can plan your maintenance expenses with confidence, and without any compromises.

StandardAero Lanseria, a Pratt & Whitney PT6A designated overhaul facility (DOF) and the sole independent DOF approved for the PT6A-140, is pleased to support operators across Africa with P&W’s flat rate overhaul (FRO) program, which combines OEM-level quality with guaranteed “not to exceed” capped pricing. Meaning that you can plan your maintenance expenses with confidence, and without any compromises.

The FRO program does not incur extra charges for typical corrosion, sulphidation or repairable foreign object damage (FOD), and PMA parts are accepted.

The FRO program does not incur extra charges for typical corrosion, sulphidation or repairable foreign object damage (FOD), and PMA parts are accepted.

As the industry’s leading independent aeroengine MRO provider, StandardAero is trusted by airline, governmental and business aviation operators worldwide for responsive, tailored support solutions. Contact us today to learn more.

As the industry’s leading independent aeroengine MRO provider, StandardAero is trusted by airline, governmental and business aviation operators worldwide for responsive, tailored support solutions. Contact us today to learn more.

PUBLISHER

Guy Leitch guy@saflyermag.co.za

PRODUCTION & LAYOUT

Patrick Tillman www.imagenuity.co.za design@saflyermag.co.za

CONTRIBUTORS

Jim Davis

Peter Garrison

Hugh Pryor

Sometimes pilots get the special privilege of seeing something that is beyond the reach of mere earth-bound mortals. The brief appearance of a comet in late January was one such remarkable event. Captain Glenn Poley was at FL380 on 22 January, at top of descent for Cape Town, when he saw Comet C/2024 G3 (Atlas). He clicked away, capturing images of the comet high above the Cape Peninsula with his trusty iPhone 13. This image of the comet above the lights of Cape Town was caught as they descended through FL280 at 21.20 local time.

There are some things about flying which fill me with awe and wonder.

FLIGHT IS THE MOST BEAUTIFUL synthesis of physics and dreams.

I get all choked when I hear the music from the twelve organ pipes of a Rolls Royce Merlin. SpaceX has the ability to regularly tear me up: when they simultaneously landed two Falcon Heavy side boosters back on their pads – or when they caught the Starship Super Heavy rocket booster in mid-air with the ‘Mechazilla’s chopsticks’. This is a perfect synthesis of man having overcome the combined challenges of space and flight to bring the whole thing back to a perfect landing.

runway and ponderously heaves itself into the air, it is an event possessed of an awesome grandeur. Even to an informed mind this experience can lead to a sense of wonder and creates an almost reverential homage to the seemingly supernatural power of flight.

It’s said that anything we don’t understand we instinctively fear. Do we as puny human beings really understand the power and the forces at work in flight of this magnitude and do pilots really understand their equipment?

At an individual person scale, the script writers for the cult movie “Waynes World” recognised the God-awful power of flight by having the two maladjusted anti-heroes getting their thrills by lying on their car directly under the glidepath of landing jets.

On a more prosaic level the sweep of an Airbus A350 wingtip and the elegant slimness of the pylon engine mounts is art at its most functional and arguably, its best.

When 500 tons of A380 thunders down a

And, if we don’t, do we then not secretly fear flying? Watching the wing tip of a 787 flexing through 2 or 3 metres in even light turbulence makes me wonder about where all that bending is coming from, and just how much strain all the brazillions of rivets – or bonding – can actually take.

Jet engine mounts are another source of amazement. I am amazed that there are not more engine separations than the infamous Nationwide Airlines Boeing 737-200 engine falling off during takeoff in 2007. The twisting forces on the spar of an airliner with underslung engines must be incomprehensible.

As an impressionable youth I remember gazing up with rapture at the tail of that most beautiful of all airliners, the VC-10, and wondering how it’s elegantly slim pylons could hold up, not just one, but two engines.

I try to convince myself with the thought that aircraft design must be an exact science with all the stresses and strengths passively allowing themselves to be computed into unbreakable rules. But nature and physics are not to be controlled that easily.

It is perhaps in primeval recognition of this fear that, when the designers do get it wrong and things like engines or hatches fall off, then the pulp press capitalises on our repressed fears and launches into orgies of sensational journalism.

significant number of commercial pilots) have given up trying to resolve – or even just decide on their own view – on the Bernoulli vs Coanda / Newton’s second law debate.

I reckon many of these pilots secretly consider flying to be somehow a bit supernatural. While training and logical thought tells us how wings produce lift, I think that in the primal and usually sub-conscious recesses of our psyche we secretly wonder at the magic of nothing but air holding up hundreds of tons of metal.

you have to have the right stuff

I wonder if people would feel comfortable in an airliner if they knew that less than an inch of flimsy aluminium was between their posteriors and the thousands of feet of empty air beneath them.

As for that perennially vexatious subject of lift, I suspect that many private pilots (and a

For long after I learned to fly, I used to wonder about the structural integrity of a Cessna 172’s seat. It somehow always seemed that locked in

You have to have faith that there will be lift - somewhere.

the back corners of my mind was the fear that the skin would someday suddenly just split and my seat and I would go plummeting earthwards. Gliders with their thin fibreglass skins are even more worrying – so I never thought about that as I was too busy looking for that other great leap of faith; invisible lift.

I only overcame my fear of having to trust my life to a few millimetres of aluminium when I took up microlighting in weight shift trikes. When your bum is supported by nothing other than a seat squab strapped to the top of a skinny tube running between your legs, and when the whole contraption is suspended from a single bolt (the Jesus Bolt) you quickly learn to have faith in the basic integrity of materials.

And so the chance of your seat suddenly and inexplicably falling through the floor of an aircraft cabin comes to seem remote and just a little silly.

If perching on a pole and hanging on a Jesus Bolt from a fabric wing helped beat my deepseated psychoses about aircraft structural integrity, a quick course in basic aerobatics will go a long way towards reassuring the average closetly suspicious pilot that Bernoulli/Coanda are not just theories. When the windscreen is full of nothing but mother earth going round at dizzying speed and your stomach is in your mouth, the demons of doubt and fear are doing their best to reduce you to a jibbering wretch –or a whimpering child.

Like Chuck Yeager, you have to be made of the right stuff, and have a blind faith in the effects of controls. Faith such that when you push the stick forward in a spin, the ground obediently stops going round. (Yes – it’s the stick forward that stops the spin, not opposite rudder – see Jim’s main article on spinning for more on this).

Anyway – back to the spin; as you calmly but forcefully ease back on the stick and the ground recedes back to where it belongs at the bottom of the windscreen, your belief in the design of the aircraft, and indeed in the whole idea of flight, is strengthened.

And so dear reader, the moral of this essay is, like Jonathan Livingston Seagull, to always be growing. Learn new skills, expand your envelope, and find out what you and your plane can do.

As you find out more about what your plane can do, so you will find out more about what you can do. And what is maturity if it is not putting the child in you in its place?

j

Located in South Africa’s Safari hub of Hoedspruit, Safari Moon is a boutique base from which to discover the wonders of South Africa’s Lowveld region. Explore a range of nearby attractions from the famed Kruger National park to the scenic Panorama Route, or simply chose to relax and unwind in nature, making the most of your private piece of Wildlife Estate wilderness.

Why do we turn left in the pattern, when we could turn right? Thirsting for knowledge, I Googled why we drive on one side of the road rather than the other.

I FOUND A LOT OF OBVIOUS rubbish about quarrelsome knights and Roman charioteers. I suspect that what really happened was that Henry Ford flipped a quarter and William Morris a shilling, and they came up different. Nevertheless, I propose to offer an explanation of why the pilot of an aeroplane sits in the left seat, and why we normally make left turns in the traffic pattern [called the ‘circuit’ in SA, as the remains of the British empire] .

Actually, this theory is not original with me. It came from my late friend Javier Arango, who was a collector, student and flyer of World War I-era aeroplanes. In 2016, the year before his fatal accident in a Nieuport 28, Javier delivered a paper on the left/ right question to the Society of Experimental Test Pilots in Anaheim. He did not claim that his answer was anything more than a guess, but it was, and still is, a plausible one.

In the broad principle of their operation, rotaries were similar to the radials that became dominant later. What was different was that the crankcase and cylinders spun while the crankshaft was fixed to the aeroplane. How this inside-out idea occurred to anyone in the first place is a mystery to me. It may have had to do with the fact that some of the very earliest uses of rotaries, in the 1890s, were in bicycles; a little engine was integrated right into a wheel.

The root of our leftist tendencies was, in Arango’s analysis, the rotary engine. The rotary was the engine type most commonly used on “scouts,” or as we would now call them “fighters,” in the First World War. Rotaries were exceptionally light and powerful and, for the era, reliable.

The rotary arrangement had several advantages. Since the cylinders were always moving, they enjoyed builtin air cooling. A rotary didn’t need a heavy flywheel; the engine itself was enough. It didn’t need an oil pump; centrifugal force did the job, if you didn’t mind spewing used oil overboard. Remarkably, considering that aero engine technology was in its infancy and that rotary engines were made entirely of steel, they achieved outputs and power-toweight ratios comparable to those of current flatopposed Lycomings and Continentals.

One inconvenient peculiarity of the rotary was that, as a heavy, rapidly spinning mass, it imposed gyroscopic forces upon the aeroplane. Fortunately, these forces were only moderately strong, for a number of reasons. The single-

The spinning engine of the Sopwith Camel gave it quirky, and often lethal, flying qualities.

engine fighters were very compact and their engines were close to the aeroplane’s centre of gravity. The rotating mass of the engine, furthermore, was concentrated near the crankshaft, because the cylinder walls and heads were remarkably thin. Finally, rotaries did not spin very fast; 1,200 rpm was typical.

Such a slow-turning engine called for a large propeller, and the propellers of early scouts were huge by modern standards. That of a Sopwith Camel, for example, was almost 9 feet in diameter, though, being made of wood, it weighed only 32 pounds – about the same as today’s 6-foot aluminium fixed-pitch. The gyroscopic contribution of the Camel’s propeller was about half that of the engine.

It happens that aviation rotaries spun, like most modern aero engines, clockwise when viewed from behind. The reason for the choice of direction of rotation, like that of which side of the road to drive on, is buried in history’s junkpile. But the effect in flight was that when a rotary-

engined aeroplane turned to the left its nose tended to swing upward, and when it turned to the right the nose went down. (The gyroscopic force is always 90 degrees off the direction of pitch or yaw, in the direction of rotation of the upper part of the propeller disk.)

Sopwith Camels rolled, using ailerons and rudder, equally rapidly in either direction, but the downward slicing of the nose in a rapid right turn, and the consequent acceleration, gave rise to the idea that they “turned better” to the right than to the left, and to the canard, repeated in Wikipedia, that Camels could make a 270 to the right more quickly than a 90 to the left.

Peculiar turning behaviour was not confined to Camels. In a 1919 book entitled How to Fly and Instruct in an Avro – the Avro 504 was a single-engine trainer widely used by the Royal Flying Corps – the author, one Lieutenant F. Dudley Hobbs of the 2nd Life Guards (who probably never dreamed that his name would be mentioned in a magazine more than a century

later), suggests securing a toy gyroscope to the nose of an aeroplane model to use as a teaching tool. “No amount of explanation of gyroscopic action is worth so much to a pupil,” he writes, “as five minutes spent playing with a little gyroscope.”

A paradoxical consequence of the gyroscopic force was that whichever way you turned, you needed left rudder. In nearly all preWorld War II aeroplanes, and some postwar ones, that did not have rotary engines, considerable rudder, applied in the direction of the turn, is normally needed to overcome adverse yaw. But a rapid, steeply-banked turn in a rotaryengined aeroplane was different. In a left turn, left rudder was needed both to overcome adverse yaw and to keep the nose from slicing upward. In a right turn, after an initial application of right rudder against adverse yaw, left rudder was needed to keep the nose from dropping.

The

Camels had a high accident rate in the hands of novice pilots. As Lt. Hobbs explains, “A pilot starts a gliding turn to the right and finds his nose dropping. Instead of holding up his nose with a little left rudder, he tries to hold it up with his stick, with the result that the machine spins.”

It was this propensity to spin out of a right turn, Javier Arango suggests, that led to a preference for approaching the landing with left turns. That habit, in turn, eventually led to the pilot occupying the left seat in side-by-side cockpits.

A couple of Lt. Hobbs’ other observations are striking. One is that to loop a rotary-engined

aeroplane you must use left rudder, because the pitch-up produces a gyroscopic pull to the right. A more surprising statement is that “a Camel will not roll properly to the left, because the gyroscopic action of the engine swings the nose to the right, with the result that the machine sits up on its tail.” This opaque assertion becomes clear when you realize that when Lt. Hobbs says “roll,” he means not what we call an aileron roll, barrel roll or slow roll, but rather a snap roll, that is, a horizontal spin that begins with an abrupt pitch-up.

In the now-proverbial words of the novelist L. P. Hartley, “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” And they speak a different language, too. But we still fly the traffic pattern the way that was most comfortable for them. j

THE LIAONING General Aviation Academy (LGAA)’s RX4E, which first flew in 2019, will be marketed globally with a focus on short-haul flights in areas without good roads.

The RX4E will target underdeveloped countries with poor roads for short-haul flights.

The manufacturer says the plane, which is about the size of Cessna 182 but with a much longer 45-foot wingspan, will have a 90 minute endurance with a range of about 160 miles and a cruise speed of about 120 knots.

According to its web site, the manufacturer says it has a 2778 pound maximum takeoff weight with a payload of about 680 pounds, but remember that it does not have to carry fuel. Top speedis about 156 knots and stall speed is 54 knots. It takes off in about 1200 feet lands in a little more. Service ceiling is about 10,000 feet. It doesn’t give details about the propulsion system except to describe it as “high efficiency.”

Volar Air Mobility, which will be selling the plane, announced the certification, which happened on December 29, in a social media post.

The RX4E was developed by the Liaoning General Aviation Academy (LGAA), “With this, the RX4E has become the world’s first electric aircraft certified under Part 23 regulations (commercial use),” said the post. “This milestone marks a new era for sustainable aviation, paving the way for commercialisation of electric aircraft in the advanced air mobility (AAM) market.”

Zhao Tienan, deputy head of LGAA said.

China has certified a four-place electric aircraft under Part 23 regulations making it the first to qualify for commercial operations beyond flight training. j

“The RX4E aircraft has a huge market prospect. It can be used in a number of fields such as short-distance transportation, pilot training, sightseeing, aerial photography and aerial mapping,” he concluded.

China has certified its RX4E electric plane.

I have been doing some long-range mentoring of a new instructor. I called her the other night to find out how she was getting on with her patter and preparation for the flight test.

She had been due to patter spinning in a little C152 and I had told her this was going to be fun – she would enjoy it and it was perfectly safe. So when I called to find out how it went I was blown away by her story.

THEY ENTERED IN A NOSE-HIGH attitude and left on about 1600 revs to make sure there was sufficient rudder authority to get the show on the road. It seems they spun so fast that she was unable to count the turns – the countryside was a blur with no identifiable features to count.

Was the stick fully back? She was not sure.

Was the throttle fully closed? She was not sure.

Were the ailerons neutral? She was not sure.

No.

Was she able to patter it? Nope it was much too fast.

They did two spins to the left and gave it up for the day.

How did they recover? Stick forward and opposite rudder

REALLY? In that sequence? She was not sure.

Was there a pause between the two actions?

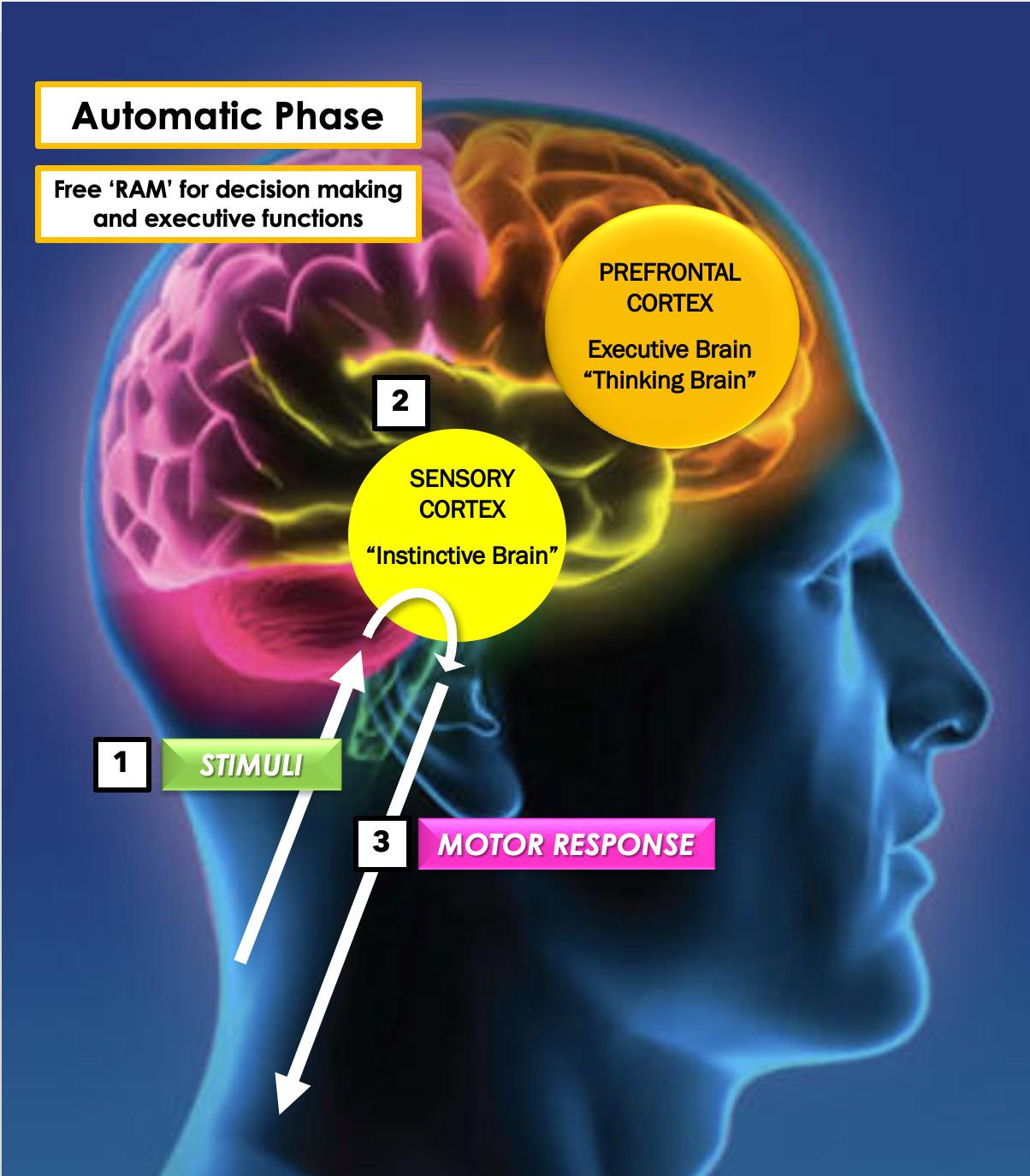

I found the whole thing deeply worrying. Either she was a panicky little girl – which she was not in the least. She is an an intelligent, calm, solid, instrument rated, commercial pilot. Or there was something else going on. They were going to fly again the next day so I risked putting my oar in and doing some long-range patter over the phone – and made her write it down. This is how it went:

As you enter the spin – throttle fully back.

Confirm the stick is fully back.

Confirm the airspeed is close to the stall (not in a spiral dive).

Confirm the direction of rotation.

Confirm the ailerons are neutral.

Firmly apply full opposite rudder.

Move the stick forward until rotation stops.

Level the wings and pull out of the dive.

The ‘pause’ is bold and underlined because if you ease the stick forward first – even by a millisecond – the spin can speed up to the extent that you can’t count ground features going past.

The following evening she was able to confirm that all went splendidly – and she had all day to watch the ground and count the turns.

in the world - an Australian named Harry Hawker.

The same Hawker whose company later built the Hurricane, the Hunter, the Sea Fury, and that most beautiful aircraft of all time – the Hart.

Let’s go back 111 years to June 1914. Picture this: Hawker is high above Brooklands in a Sopwith Tabloid. His goggles keep blurring as the freezing wind mixes with a mist of hot castor-oil – Castrol R – from the 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape. His nostrils are filled with its pungent smell which will at least make sure that his bowl movements are regular. He is shivering, possibly from the cold, but more likely from the thought of what he is about to do.

I beg you not to teach

Instructors, I beg you not to teach spins unless you are totally relaxed and current and comfortable with them. One incident like this can do a lifetime of damage –or it may simply shorten everyone’s lifetime.

Let’s talk a bit about the fascinating history of spinning before we get on to the good stuff about teaching, or not teaching, them. This subject is as wild as the spin itself.

A spin is a condition where the aircraft is pointing steeply down. One wing is deeply stalled and very draggy, while the other wing is partly stalled, and flying around it. This means the aircraft comes down in a corkscrew motion with the airspeed only a little faster than stall speed.

Right, that’s dealt with the formalities. Now I am going to tell you about the bravest pilot

He plans to intentionally enter a maneuver that is statistically sure to kill him. Hawker is deliberately going to spin the aeroplane and hopes that his recovery plan will work. History tells us that it will almost certainly not work.

No one has ever deliberately entered a spin and recovered before. It’s worth reading that again. Imagine how you would feel if your instructor said, “we are going to try a maneuver that is statistically certain to kill us”.

But Hawker thinks he can do it and survive.

Up until then there had been many accidental spins, and almost all ended in death. In fact spins were the biggest killer of pilots. No one understood what caused them, or how to recover. You were simply warned not to turn when the airspeed was low – because the spin god would grab you and hurl you into the dirt.

And no one knew how to recover.

But Hawker believed he had worked out a way to regain control. And he was prepared to bet his life on it.

He started the spin by deliberately running out of airspeed during the entry to a loop. The aircraft obediently dropped into the expected gyration. Hawker allowed it to do a couple of turns and then put his recovery plan into action.

It did not work.

He spun all the way down to the ground and crashed into a forest which left him cut and bruised, but alive.

While he was being patched up in hospital he thought of another method of recovery. He was so certain that his new procedure would work, that two days later he was again wiping the castor oil off his goggles as he looked down on the English countryside.

in his seat, then applies full right rudder. The aeroplane immediately pops out of the spin, levelling off barely 50 feet above the stunned crowd! The event becomes known as the “Parke’s Dive”.

Wilfred Parke is the first to identify the need to use opposite rudder for spin recovery. His experience also highlights the fact that spin recovery actions are contrary to our natural instincts; hence, the appropriate response must be learned. Parke’s Dive is chronicled in the British publication, ‘Flight’, including the first-ever spin recovery procedure: Apply rudder opposite to the direction of rotation.

Unfortunately, Parke had only got it half right. Three months later, he spun a Hanley-Page monoplane into the ground when he tried to turn back following an engine failure after takeoff. He was killed.

Before telling you what happened, I must take you back two years and introduce you to Lt. Wilfred Parke, RN.

August 25 1912. A crowd gathers at Larkhill Aerodrome in Salisbury Plain, England, for the return of test pilot Lt. Wilfred Parke, who has just broken the world endurance record of 3 hours in an Avro G cabin biplane. The Avro G has no forward windscreen, requiring the pilot to look out sideways for visual references. While spiralling down to land, the airplane suddenly enters a left spin.

Consistent with the prevailing theory on recovery from an apparent sideslip, Parke responds by adding full power, pulling the control wheel fully aft, and pressing the left rudder all the way to the stop. Rotation earthward continues unabated. Spinning ever closer to the ground, Parke perceives a force pushing him to the right. He releases the control wheel to centre himself

Now we can return to Hawker’s windy cockpit. He thought that Parke had been on to something when he used opposite rudder. He believed that the other secret ingredient to spin recovery was to go against all instinct. Instead of pulling the stick back to recover, he would push it forward.

Hawker’s epitaph describes him as a “simple, clean, straight souled man.” Picture this slim 25 year old huddled against the cold in an open cockpit, high in a crisp English sky over Brooklands. He is half a world removed from his home and family.

He is again prepared to bet his life on an idea. You can’t get much braver than that.

This time it worked.

So every time you recover from a spin, or even an incipient – say a quiet word of thanks to Harry Hawker – the man who was brave enough to save your life.

Right, that’s the end of the history lesson. We are now in 2025, and aeroplanes still spin into the ground. What’s to be done about it?

Basically, there are three trains of thought:

1. Teach pilots to do full spins and recoveries.

2. Teach pilots to recognize the early part of a spin and recover before this incipient stage develops into a full spin.

3. Teach pilots to recognize and avoid the conditions that could lead to a spin.

Now let me tell you that I am biased. I have only once accidentally entered a lifethreatening full spin. I’ll tell you about it later. I was able to recover solely because I have spun so often that I am completely comfortable with spins. In fact I enjoy them. I have deliberately entered thousands of spins, and not one has caused a problem – even the ones that went flat, or were inverted.

In fact for instrument rating tests we had to do full spins in cloud on a limited panel – with the AH and DI caged so as not to damage them.

In my book, folks who have only been taught the approach to a spin, or an incipient spin, are not fully competent pilots – and certainly should not be instructing others anywhere near the stall.

Now, before your bleating becomes a roar of abuse, let me tell you that I am wrong.

Methods 2 and 3, above, have saved far more lives than the ability to handle spins with confidence. It is not my opinion – these are hard statistics supplied by AOPA.

You can see from Chart A, that by far the majority of fatal spins are started below circuit height. This means that knowing how to recover from full spins would not save you in something like 70% of all spins.

Now have a look at Chart B. Up until 1949 nearly half of all fatal accidents in the USA were the result of spinning. That’s a seriously scary figure. Anyhow in 1949 the FAA took full spins off the menu for PPL training. They were

no longer compulsory. Look what happened –there was a massive decrease in the number of these accidents. Today the figure is around 8%.

If you find that surprising, have a look at Chart C. What hits me in the eye is that only one stall/spin accident, out of the sample of 465,

was while crop-dusting. Amazing. Anyhow by far the biggest percentage of accidents happen during “maneuvering”.

AOPA say: Maneuvering flight is loosely defined, but usually includes any type of flight where a pilot is using the aircraft’s flight controls to perform maneuvers not necessary for straight-and-level flight.

Many pilots commonly associate maneuvering flight with unauthorized low-level flight such as “buzzing” but other types of maneuvering flight might include low-level pipeline patrol, banner-towing, aerobatics, or even normal upper-air work in the practice area. The NTSB defines maneuvering flight to include all of the following: aerobatics, low passes, buzzing, pull-ups, aerial application maneuvers, turns to reverse direction (box canyon type

maneuvers), or engine failures after takeoff with the pilot trying to return to the runway.

Out of interest, according to the 2002 ASF Nall Report, takeoff accidents (including those that result in a stall/spin) are much more likely to be fatal than landing accidents. I don’t know whether go-arounds are classed as takeoffs or landings. Certainly they are badly taught in South Africa and account for many fatalities.

So maneuvering includes most of your training, which, in turn, includes steep turns, sideslipping, stalls, slow flight, spinning and incipient spins. (Interestingly they all start with a snaky “S”.)

OK, I got sidetracked, again. We were deciding how to handle spinning, and I was saying that statistically spin training shortens your life-expectancy. It still breaks my heart that this is the case –but the figures prove me wrong. Anyhow let’s look at the next option –incipient spins.

Perhaps these were an intelligent option forty years ago when instructors were mostly happy to spin, but now we have a huge number of instructors that are shirt scared of spinning. You really don’t want to be doing incipients with someone like that. Here’s what AOPA says about it:

So we seem to have done a full circle. That was the perceived wisdom in the days of the Wright Brothers – and that’s still what we should teach pilots.

In reviewing 44 fatal stall/spin accidents from 1991 –2000 classified as instructional, AOPA found that a shocking 91% (40) of them occurred during dual instruction, with only 9% (4) during solo training flights

So this leaves us with option 3. Teach people to recognize and avoid the conditions that could lead to a spin.

I agree that if you keep away from anything that could cause a spin then you will never spin. But we are talking about deliberate actions to keep clear of stalls and spins. So what do we do about accidental stall/ spin conditions, perhaps while practicing steep turns or sideslipping or stretching the glide or turning to avoid trees you can’t clear after takeoff? How are we meant to avoid accidental spins? It simply doesn’t make sense.

In fact, it takes us right back to the dark ages when you were warned not to turn when the airspeed was low.

Something is very wrong. A spin is the most dangerous loss of control a pilot can encounter. So should we teach pilots,

a) Not to lose control – but if they do they are dead meat.

b) Not to lose control and how to regain control.

Or here’s another thought. Would you like your kids’ driving instructor to teach them not to skid, or would you like them to learn how to avoid a skid and how to recover from one?

Okay I am outvoted and I am wrong and I am very unhappy about it.

I love spinning.

Instructors, don’t despair – I have much more on the subject next month. j

OPERATING FROM GRAND CENTRAL Airport in Midrand, Superior Pilot Services prides itself in its wealth of knowledge and experience in the aviation sector, offering a variety of certified courses, from the Private Pilot’s Licence to the Airline Transport Pilot Licence, Instructor’s Ratings and Advanced training. The school specialises in personal outcome-based training and combines the latest techniques, methods and training aids to maintain a high level and standard throughout. Superior is proud to have been selected as a service provider to numerous institutions like, TETA, Ekurhuleni Municipality, KZN Premiers office, SAA, SA Express and SACAA cadets, however their ideally situated location allows the general aviator and businessman to conveniently access and utilize the same services.

With highly trained and qualified instructors and a fleet of Cessna 172s, a Cessna 182, Sling 2, Piper Arrow, Piper Twin Comanche and R44 helicopter, the school has the know-how and experience to prepare the best pilots in the industry. Making use of a state-of-the-art ALSIM Flight Training Simulator, the Superior Aviation Academy offers unmatched facilities that ensure students’ social needs are catered for and that the training offered is at the forefront of international training standards. The Alsim ALX flight simulator model provided by Superior Pilot Services is EASA and FAA approved and has proven itself worldwide. It provides up to four classes of aircraft and six flight models that cater from ab-initio all the way to jet orientation programmes in one single unit available 24/7.

The school offers a range of advanced courses, including IF Refresher Courses, Airborne Collision Avoidance System (ACAS), GNSS/RNAV, CRM and Multi Crew Coordination (MCC) conducted by its qualified instructors. The school also offers PPL and CPL Ground School and Restricted and General Radio Courses. Superior Pilot Services has accommodation available. The lodge is conveniently located just six kilometres from the airport. All rooms are based on a bachelor’s unit which includes laundry and room cleaning services as well as breakfast. Students have access to the communal lounge, gym and entertainment room, pool and ‘braai’ area.

We elevate the ar t of aviation design to new heights. Our innovative approach blends cutting- edge technology with timeless elegance, transforming aircraf t into personalized sanc tuaries of comfor t and style. From bespoke seating & advanced cabin layouts to exquisite liveries, we craf t ever y detail to ensure your journey is as ex traordinar y as your destination.

Liver y Design

Photorealistic 3D previews

Photography

FlySafair has been much in the news of late – whether over drunk passengers or the threat of being grounded by the two air services licensing councils over disputed foreign ownership.

Kirby Gordon, the Chief Marketing Officer of FlySafair, says that the licencing council rules are vague and open to interpretation. He therefore insists,

"If the Councils can just give us a clear ruling as to what they require, we will be happy to comply - if we are in fact not already compliant. But at the moment it seems that almost all the airlines are non-compliant, and they expect us to sell or give 75% of our company to some natural person."

Flight Test:

Guy Leitch with Murray Kester

Due to the huge value and the irreplaceable nature of a real Spitfire, very few select pilots will ever get the opportunity to pilot the real thing.

FOR LESSER MORTALS there is the option to build and fly your own replica. This is what Australian enthusiast Mike O’Sullivan did after completing a couple of homebuilt projects.

O’Sullivan built his first Spitfire replica in the early 1990s as a 75%-scale version of the original, which he called the Mk.25. Inspired by legendary Spitfire test pilot Alex Henshaw, O’Sullivan completed his own Spitfire and liked it so much he decided to sell kits to like-minded enthusiasts worldwide.

Several Mk.25s were built before he came out with a slightly larger model that had bigger engine options and added a second seat behind the pilot. This was naturally designated the Mk.26. However the second seat was cramped and so he expanded the fuselage yet again to become a 90% version, which he called the Mk 26B.

Whether in Mk26 or Mk.26B forms, the aircraft is an all-metal, monocoque design with a fiberglass cowl.

An important goal for Mike O’Sullivan was for his Mk.26 to look like an original. This ruled out any Rotax engine options. Fortunately Australia is also a great source of aero engines – in particular, the widely used Jabiru air cooled direct drive engines. There are hundreds of Jabirus flying in South Africa and so there is a vast repository of skills and experience for the operation and maintenance of these simple yet proven engines.

Top of the range is the 8-cylinder Jabiru 5100 which is good for 180 hp. Despite this being far less than the original Merlin’s 1,600 hp, this still gives much the same power to weight ratio yet with a proven engine that is far simpler and cheaper to maintain than a supercharged Rolls Royce Merlin that needs to be overhauled around every 250 hours.

Watching the development of this home-grown Aussie product with great excitement was Murray Kester from Western Australia.

Murray acquired Mk.26 kit #47 and after around 1,665 hours of passionate work, finished his beautiful aircraft in 2016. Perhaps surprising, given the more traditional Battle of Britain camouflaged paint schemes that are most often used, Murray elected to paint it in the bright red livery of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Murray says, “I bought the kit in 2005 and work on it progressed slowly as I was still employed up until 2014. I’m

originally Canadian so I thought the maple leaf roundels looked good and I didn’t want yet another war bird. When I gave Mike O’Sullivan the cheque I told him it was not going to be a war bird and would likely be red and white. He thought that would be great.”

On the apron at Serpentine Airfield south of Perth, Murray’s Spitfire Mk.26 is a thing of beauty and a great crowd pleaser at the airshows he has graced with its presence across Westen Australia. The fit and finish are exemplary, tempting you to run your hand across the smooth flush-riveted skins.

With its nose high stance, it looks ready to leap into the air. The only slightly discordant note is the

narrow 2-bladed prop which is a fixed pitch twoblade black painted wooden Hercules prop. Jabiru insists that only a two bladed wooden prop with a maximum diameter of 72” be fitted to this engine. The prop was specially designed by Hercules in the UK for this engine and airframe and has a 61” pitch. The spinner is a four hole from a King Air, installed in anticipation of fitting a 4-bladed prop to a Toyota V12 engine.

The front cockpit of the Mk.26 is on a par with most tandem 2-place aircraft such as the RV-8, although the rear seat is more cramped and reminiscent of a weight shift trike with the seat squab up against the back of the front seat. The rear seat may be tight but thanks to the large bulged canopy, is not claustrophobic. There is no heater, but there are two large eyeball fresh air ducts.

The pilot’s seat is ground adjustable to optimise the pilot’s position relative to the rudder pedals and cushions can be used to vary height and comfort. While there are two seats in the Mk.26, the rear seat does not have rudder pedals or a stick and is only suitable for a person under 70 kilos.

Entry into the cockpit is via an authentic bottom hinged door, a feature found on the original Spitfire and carried through for both nostalgia and practicality.

Murray’s choice of instrument panel for VH-BPD features low maintenance modern glass avionics.

The panel is dominated by a large Dynon Skyview touch screen Primary Flight Display

with comm and transponder controls on either side. The comm radio has a feature (that hasn’t been used in this plane) that can detect a tower frequency when within reach and switch to it.

Below the Dynon is a row of rocker switches for the engine and systems. Notable

The undercarriage operation is idiosyncratic. The mainwheels can each be operated independently. Murray Kester says, “It takes 15 seconds up and 15 seconds down. An electric motor drives a worm gear to deploy and retract the gear. The only reason for the independent controls for each main

is the rocker switch bottom left for the flaps and two rocker switches bottom right to operate the undercarriage. Once the switches on the panel are ‘on’ two levers on the right sidewall operate the ‘chassis’ or undercarriage – or if you speak American, the landing gear.

wheel is that was the way the original Spitfires were built, but I have no idea why.”

To raise the undercarriage the pilot places both left and right selector switches in the retract position before takeoff. Once a positive climb rate has

been achieved, the pilot reaches over to the right sidewall (switching hands on the stick), and pulls back on both undercarriage levers, which unlocks the pins and causes the electric motor to run in the direction selected by the switch. After 5 to 10 seconds the wheels should be in the wells and the Up-indicator light comes on. The pilot then pushes the levers forward to lock the undercarriage in the Up position.

Lowering the undercarriage is the same procedure, with the switch in the opposite position. This all takes getting used to for new pilots, and operations need to be deliberate. Emergency extension is achieved by pulling release cables and letting them free-fall.

Like an RV, the flaps are selected down for the pre-flight to discourage the pilot from stepping on them to enter the cockpit. The flaps operate similar to car windows. A switch is held down to deploy the flaps – which stop as soon as the switch is released. Pushing the switch upwards stows the flaps with a nonstop movement. As there is no cockpit indicator, the flaps have to be eyeballed to judge the position. Murray says, “I put a mark on the port flap which indicates mid-flap position. Maximum flap angle is 50 degrees, but I wouldn’t advise going that far. The pilots who have flown her are quite happy to look out the window and set the flap by feel.”

An novel feature is the screen below the instrument panel which is connected to two on-board cameras. One on the left

wing lets the pilot see what’s coming while taxying. The other is on the belly and clearly shows the undercarriage. It gives a bit more confidence that the gear is either up, down or in transit. A toggle switch on the screen selects which camera is displayed.

The throttle is a single lever on the left sidewall, sharing its quadrant mount with the pitch trim lever in the place of the mixture control. The mixture control is now a simple push-pull knob on the instrument panel in front of the throttle. Below the throttle quadrant is a large push-pull knob that operates the cowl flap.

The wing inspection covers the usual points: aileron and flap hinges, brake fluid leaks, tyre condition and any sign of

Tailwheel is non-retractable but steerable.

undue rubbing which might suggest poor undercarriage rigging. Three hatches take care of the engine inspection.

A single fuel drain at the front of and below the left wing is all that’s needed to check for water. The inspection procedure is repeated for the right wing.

There’s little about the tail section which needs any special attention.

Entry to the cockpit requires a big step up onto the training edge of the left wing (all proper fighters are entered from the left). Thanks to the side door, you don’t need to stand on the seat to slide your legs down through an oval bulkhead aperture. The cockpit is spacious for an average-size pilot, and

despite the classically high cockpit sills, the visibility to the sides is good. Because it uses a flat-8 engine, the top of the long cowl does not need to be as wide as that over the V-12 of a Merlin and so visibility forward is slightly better than the full scale Spit. But it is still a classic taildragger and so S-turns while taxying are essential.

Once settled into the cockpit, the Mk.26’s four-point harness is an improvement on the original’s pin-secured belts and the buckle is easy to secure and release.

At first glance the spade grip control stick replicates the famous hinged loop Spitfire wheel, but it is fixed to the stick and thus articulates only at the base.

For the before-start checklist, you start inside the cockpit to make sure the undercarriage and flaps are selected down. The fuel level is checked via the

tube which runs from the top of the tank in front of the instrument panel to a point close to the bottom. Shaped like a T, the fuel tank is located on the centre of gravity behind the firewall and between the pilot’s legs.

With its SDS electronic fuel injection, the big flat-8 Jabiru engine fires up as smoothly as a car and has a beautiful deep throated rumble through stub exhausts on either side of the long cowl. Like any air cooled aero engine, it must to be warmed up, but this is an improvement over the original Spitfire which needs to get airborne quickly after start otherwise the coolant overheats.

Like any prudent tail dragger pilot make sure it’s lined up straight for takeoff. Open the throttle and the whole airframe comes alive – just as though there were 1,600 horses raring to go.

The steerable tailwheel gives good control on the ground, whether on pavement or the Spitfire’s natural element: grass runways. Just like the original, rudder authority is limited, and so pushing the stick forward to raise the tail early in the takeoff roll runs the risk “of running off the left hand side of the runway under engine torque,” Murray says.

After a brief takeoff roll, the Mk.26 is ready to fly but it’s not a good idea to try get airborne too early. At 7075 mph it will fly itself off and have plenty of rudder authority to manage any threatened swing. Climb out at 2400 rpm with one up and full fuel is a healthy 1,100 fpm at 90 mph IAS.

The fuel tank holds 110 litres and with the engine burning around 35 litres an hour, a two and a half hour endurance is not unreasonable, with the Mk.26’s cruise speed of up to 160 mph (140

knots) at 2600 rpm and economical cruising at 120 knots at 2400 rpm, burning 30 litres/hr.

The airframe is stressed for plus 6 G and minus 3 G and is capable of most aerobatic manoeuvres, but no flick rolls. Loop entry speed is 180 mph, and rolls are started at 140 mph. “It’s a lovely plane to fly basic aerobatics”, says Murray.

Back in the circuit, the undercarriage can be lowered at a usefully high 130 mph, with the limit being 140. 110 mph is the target speed for base leg, and with full flap, final approach speed is between 75-95 mph, depending on weight and wind.

The aircraft can be 3-pointed, but is best wheeled on, purely because of the rapidly diminishing view over the nose at anything near a three-point touch-down.

Murray says “There’s little to see of the ground, and the only points of reference are each side, and in front of the wing. I bring the flaps up as soon as the tail

is down to place more weight on the wheels as early as possible.

“The Mk.26 can be landed and stopped in 400 metres, but if you get it wrong, the results can be humbling. Also, I far prefer landing on tarmac because the wheels are quite small - even a small tuft of uneven grass can start a swing on the ground,” says Murray.

Whilst the Mk.26 does not present too much of a skills jump for a pilot with 50100 hours on a taildragger, those used to a benign taildragger like a Piper Cub might find it a challenge.

Seeing the Mk.26 in the air is a reminder that any Spitfire is very special indeed. The iconic shape is defined by its slim fuselage, relatively wide chord wings and the beautiful elliptical planform of the wings.

It is a shape which arouses very strong emotions in any pilot with a high aesthetic sensibility. Even those with no connections to the Battle of Britain will struggle to remain unmoved by a Spitfire’s iconic airframe flying overhead, or better still, doing a low pass ‘runway inspection’.

Now it’s possible to approximate the real thing in the Mk.26, which is an affordable yet rewarding modern day replica.

Dimensions Length

Engine Jabiru 5100 8-cyl 180hp

Weights and loadings

Empty weight 620kg

MTOW 190kg

Useful load 172kg

Airframe `+6G - 4G

Performance

Vne (IAS) 222mph

Cruise (TAS)@6000ft 160mph

Range 400 sm

Stall 48mph

AS THE DESIGNER of the Mk.26, Mike O Sullivan has done a brilliant job making his scale replica as close as possible to the real thing – and in some cases it is even better.

Neil Thomas has flown both the real Spitfire and the Mk 26. He says, “The scaled replica is very similar to a real Spitfire to fly. The Mk.26 has the same beautifully light and harmonised controls throughout the speed range. The stall is benign with a gentle roll-off in any configuration: 52-mph clean and 44-mph with the gear and flaps out.”

Neil’s descriptive words are exactly what designer Mike O’Sullivan aimed to achieve, as he feels strongly that the flying experience needs to be just as authentic as flying the original aircraft.

In a number of key areas, the Mk.26 is better than the original. As mentioned, in the original, you need to start the takeoff run within four minutes of starting a Merlin. The coolant temperature rises by 10°C every minute at idle and the two big and important gauges were the temperature and boost. Too much boost from the supercharger and the engine would flood. The fuel/air ratio is important to the Merlin’s ability to run smoothly - it’s a lot more temperamental than the Jabiru 5100.

“Another Spitfire foible is its horrible brake system, which requires squeezing a handlebar-type lever on the circular control grip. Applying the brakes relies on pushing the rudder pedal on the side you want the brake to work. Before applying the opposite brake, the pressure has to be released by letting go of the handle first. It takes a good 12 hours to get used to it and I suspect it was a major cause of ground loops in a Spit during and after World War II. I still don’t know why the Brits didn’t simply adopt the system found on US trainers and eventually the Mustang. But imagine the British admitting to copying the Americans!”“In the air the Mk.26 is uncannily like the real thing to fly. Although the cockpit is much smaller, the same harmonious handling and light controls are almost identical. The Mk.26 and the real thing are stunning to fly and it’s easy to be lured into the spirit of a real Spitfire whilst flying the Australian copy. However, the Merlin is far more temperamental, and the Rolls Royce engines barely made 300 hours before overhaul - and only then if they were lucky.

The real Spitfire really talks to you, including the engine, but it is very temperature sensitive, requiring care throughout a sortie. In a real Spit the Merlin easily overheats due to the undercarriage legs disrupting the airflow

into the radiators beneath the wings. It also fouls up the plugs when pilots come back on the power in the cruiseit is an aeroplane that requires flying at high power settings - just like a Formula One car or thoroughbred horse, That is where it is designed to perform as the air force wanted. The Mk.26 has no such demands.

“Landing a real Spitfire, I watch for the tarmac either side to grow as that is the only indication there is any drift. On a narrow runway it needs to be confronted immediately as the view all but disappears when the tail goes down.”

Overall the Mk.26 is the nearest thing to a Spitfire the right side of two million dollars “ j

MURRAY KESTER HAS RETIRED from flying and wants to find a good home for his beautiful and proven Mk.26.

Supermarine Spitfire Mk26 Serial #47 is painted a vibrant red with white trim and underside. It has custom made engine cowls that give it that unique Spitfire appearance.

The Jabiru 5100 5-litre 180 hp 8-cylinder engine has a total time of 31.4 hrs. The TBO is 2000 hrs, The engine has SDS electronic fuel injection and is CASA compliant. It has 8 new pistons and the cylinders are honed. The engine is running beautifully and sounds fantastic.

• Included in the package is a completely refurbished Toyota 1GZFE 300 hp V12 engine with an aviation logbook.

This aircraft features:

• Dynon Skyview Avionics

• Upgraded undercarriage

• Matco brake conversion

• +6 / -3 aerobatic limits

• 30 litres/hr fuel consumption; 115 litres fuel capacity Hercules 72 inch diameter, wooden propeller.

• Backup 12 volt electrics to run the fuel injectors and EMS

Murray Kester says, “This makes this whole package an ideal project for someone who wants a superb Spitfire with a V12 engine. It adds at least $10,000 to the value to the plane. Had I found that engine earlier, it would now be in the plane. At 300 hp, it will liven the plane up quite a lot. The engine has been stripped down by an AME who said it was in pristine condition. I took the opportunity to change all bearings and chains. It owes me $13,000. I have an aviation log book for the engine. Should the plane be bought locally, I would be keen to assist in the engine conversion.”

Price is negotiable around AU$130,000 and all genuine offers will be considered. j

The Jabiru 5100 5-litre 180 hp 8-cylinder engine has a total time of 31.4 hrs and a TBO of 2000 hrs. The engine has SDS electronic fuel injection and is CASA compliant.

It has 8 new pistons and the cylinders are honed. The engine is running beautifully and sounds fantastic.

This 80% scale Spitfire is amazingly similar to the original.

Included is a refurbished Toyota 1GZ-FE 300 hp V12 engine with an aviation logbook.

Should the plane be bought in South Africa, the seller would be keen to assist in the engine conversion.

Price is negotiable around AU$130,000 and all genuine offers will be considered.

Time of Accident: ±1800Z

Type of Aircraft: PIPER PA 34-200T

Type of Operation: Private

Pilot-in-command License Type: Commercial

Age: 24

License Valid: Yes

PIC Experience Total Flying Hours: 1064.0

Hours on Type: 354.3

Departure: Kruger Mpumalanga Airport (FAKN)

• This discussion is to promote safety and not to establish liability.

• CAA’s report contains padding and repetition, so in the interest of clarity, I have paraphrased extensively.

Intended landing: Piet Retief Aerodrome (FAPF)

Accident site: Runway 15 – Piet Retief Aerodrome

Met Fine: Wind light variable from the South,

Temperature: +20°C, CAVOK

POB: 1 + 5

People injured: Nil

People killed: Nil

Synopsis:

ACCORDING TO air traffic control at FAKN the aircraft landed at their facility at 1652Z on an inbound flight from Inhambane in Mozambique with six occupants onboard.

After landing the aircraft uplifted 360 liters of Avgas. According to available records all occupants cleared customs.

Emergency personnel as well as the fuel attendant recorded the aircraft again departing their facility at 1720Z for a flight to Piet Retief, which is a licensed unmanned aerodrome with no active runway lights.

At the time of departure from FAKN the control tower had already closed down for active duty (1700Z).

An arrangement was made by the pilot that two vehicles would be parked at the threshold of Runway 15 at FAPF awaiting the aircraft with their headlamps illuminating the runway.

The pilot perceived his approach to be quite high at the time and he increased his rate of descent accordingly. On final approach the pilot experienced what he described as a lack of runway perspective due to insufficient lighting and the absence of natural light (moonlight).

In this image cars were positioned down the side of a runwaybut at the threshold with converging lights is best

His intention was to fly low over the vehicles to maximize the use of their lights but realized too late that his approach was too steep. In an attempt to flare the aircraft, he exceeded the elevator control range and collided with the roof of one of the vehicles (Pajero) at ±80 knots. It would appear that the impact severed the nose gear assembly resulting in a wheels-up landing on Runway 15. The aircraft skidded along the runway for approximately 70m and then turned

JIM’S COMMENTS

I HAVE BEEN STARING at a blank screen and wondering what to write that will persuade people to use common sense.

But of course it isn’t really a lack of common sense that caused this crash. So what is it that causes an otherwise sensible pilot to take a fat chance with other people’s lives?

If I had sat him down before this 100 nautical mile flight into the dark and asked him if he really thought it was a good idea to endanger

The result of a quick conversion.

sideways. Coming to a halt on the runway. The aircraft was substantially damaged. Nobody was injured in the event.

During an attempt to land on an unlit runway at night the aircraft collided with a vehicle on short final approach, which severed the nose landing gear assembly from the aircraft and resulted in a wheels-up landing on the runway.

everyone’s lives by not having a proper place to land, I suspect he would have called it off.

He must have known roughly what a crashsite looks like. Burned bodies, twisted metal, humans converted to slimy pieces of meat and bone. Flies and a terrible smell.

So what force drives this pilot to risk all that?

Two things – pride and testosterone. These are incredibly powerful pressures that obliterate fear, imagination and common sense.

ZS-NYC after having been repaired from its unnecessary mishap. Image Malcolm Reid.

Well that’s the case for roughly half of the world’s population – the half that were born males. In order to avoid politics and genetics I will not mention the undecided, or unclassified sectors of humanity. Oops, I just have. Sorry.

Anyhow in general – lady pilots don’t do silly things like beat-ups and showing off and flying into cars on pitch black nights. They know when, and how, to say no.

Here’s what a lady pilot might say to a passenger who tries to bully her into a flight she knows is dangerous.

“It’s better to be late, Mr Plunkett, than the late Mr Plunkett.”

Actually I’m always shattered by pax who try to override a pilot’s decision not to fly. If I were a student SCUBA (Self Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus) diver, and my instructor told me that today there was a danger that I could run out of oxygen, have my leg chomped off by a shark, or suffer from the staggers, I would open a beer and wait for more propitious conditions.

You’d think a non-flyer would respect the pilot’s decisions – but it often doesn’t happen.

Let me tell you about those most repulsive members of human society – the charter passengers. If you get the impression I dislike them you have underrated my loathing of these blots on the landscape. I speak of the ones who say, “Put my luggage in the Land-Rover and call my wife to tell her I’ll be late.”

Anyhow here are a couple of stories about how I have managed to deal with them.

I have just landed at Middleburg, having flown four of these horrors up from George. As they are about to get into airconditioned cars and leave me on the hot, desolate airfield, I corner the chief horror and explain that we need to take off at 5.00 pm in order to get home before dark as, in those days, George airfield was unmanned and unlit.

I spend the day with a cowboy book, a bottle of water and sandwiches in a Tupperware container. This is the lot of the charter pilot.

Eventually the Four Horrors pitch at about ten to six.

I ask them what their plan is – they look at me as if I’m mad and tell me they are now ready to depart for George. I tell them we can’t land there because I can’t find airfields in the dark. They are amazed but insist on going as the Chief Horror says he knows where the airfield is.

Of course, when we cross the Outeniqua mountains, and I ask the Chief Horror to point out the runway amongst the lights below, this causes some consternation. So I relieve the pressure by telling them that exactly 162 nautical miles to the east there’s a lighted runway at Port Elizabeth. We will be night stopping there and the extra costs will be invoiced to their company.

I never saw them again – but they did pay.

I’ve told you this next story before, so I’ll keep it brief.

I was based in Kimberley, and I had to fly my rotund and normally jovial boss, Bert Potgieter, to Bloomies in our brand-new Twin Comanche, ZS- EAR for a Very Important Meeting. It took a bit over half an hour to cover the 83 nautical miles.

Sadly the summer thunderstorms had started bubbling early that day. When we arrived there was the grandmother of all Charlie Bravos sitting on top of Bloomies, like a fat hen on a dozen eggs. There was no way in hell we could get in.

A couple of days later I overheard him telling some charter pax that I was the safest pilot in the world.

It was actually on that return flight, while Bert was shouting at me, that I invented my foolproof anti-bullying-pax idea. All you have to do is mentally replace the pax with wooden boxes containing tape recorders that emit stupid and offensive words.

Sounds silly? It works like a strap, and I have used it ever since in the air and on the ground to avoid doing things that frighten me.

Now, to get back to this accident. If you really have to land at night with car lights, the SAAF taught me that you need two Land Rovers, but I suppose Toyotas will do.

They are at the threshold – one either side and well back from the runway. They must shine their lights inwards at about 45 degrees so their beams intersect at the touchdown zone.

I explained to Bert that his VIM had just been cancelled. He told me that was impossible and I tried to explain that I was a coward and the thought of an early death held no appeal.

On the way back to Kimberley Bert shed his customary good nature and bellowed at me like an enraged buffalo. He informed me that he hadn’t bought an expensive aeroplane to be stuffed around by a cheap pilot. I was fired. However we did agree that this would only take effect after landing as he had no idea how to get this lot on the ground.

I ignored the firing – it had happened before, and I found that it generally dissolved withing 24 hours.

At the far end of the runway you have someone holding a bright torch, at waist height, pointing down at the ground ten metres away so as not to dazzle the pilot – this is only for direction after touchdown.

I’m not advocating this – but if you are going to do something silly, do it sensibly.

Take home stuff.

• Ask yourself - would a lady pilot do this?

• Brief your pax the day before on possible delays or diversions.

• Remember the tape recorders – they have often given me solace.

• In the long run you will be alive and respected for saying NO. j

TTAF: 7195 hrs: In excellent

Engines/Props

• LH engine 659 hrs SMOH

• RH engine 1235 hrs SMOH

• Props overhauled 2024

• New rubber fuel cells in wings

• GAMI fuel nozzles

Key avionics:

• Dual Garmin G5 primary flight instruments

• Genesys (STEC) 3100 digital autopilot

• GTN 625

• GNS 430 Nav/Com

• GNC 225 Nav/Com.

• G500TXi as primary engine instrument with CiES digital fuel senders

T-hangar available for rent at a secure private farm airstrip near White River. No landing fees. Power available. R2200/m. Contact Jeremy (064 931 1642).

ZU-ROO is a Gazelle now flying in Libyan parades. Image - Cassie Nel

This month’s column closes off 2024. The year has flown by quickly and by the time you are reading this column you will already be well through the first month of the New Year!

BEFITTING DECEMBER’S STATUS as a holiday month where South Africans traditionally take time off and companies close their doors for the Christmas and New Year period, we have very few aircraft mentioned in this month’s updates.

These updates are kindly supplied by the SACAA on a monthly basis for which we are very grateful!

Just seven aircraft have been registered this month, while three depart our shores.

in the last half of 2024, replacing their elderly Embraer 170s. But by early January they had not yet entered service.

Airlink has registered another one of their four Embraer 175s, ZS-YBE (17000343) but these aircraft seem to be taking longer to enter service than expected. They were reportedly to have started commercial services with these jets

The Pilatus PC-12 family continues to be a popular choice for aircraft owners in southern Africa with yet another new PC-12NGX, ZS-JHG (2433), being registered. This aircraft arrived on delivery to Cape Town on 13 January having ferried from Switzerland via Heraklion, Luxor, Djibouti, Entebbe and Victoria Falls.

The last fixed wing this month is a Scheibe Flugzeugbau SF28A touring motorized glider. This is a type we don’t see too often in this column!

ABOVE: ZS-EAI Is a Beechcraft 1900D now exported to Algeria.

BELOW: ZS-TGY is a much travelled Boeing 737-500 now exported to Goma DRC. Image

Gulfstream IIB N24FU departing HLA in May 2022 heading to its new owners in the USA. Image - Morne Booij-Liewes.

December only saw a single helicopter being registered: an Airbus Helicopters (formerly Eurocopter) EC120B is added, taking up the registration ZT-HKL. This 2016 built helicopter was operated by the US Department of Agriculture as N250WH from its delivery till its sale and export to South Africa in the latter part of 2024. It is not known who the new owners are as this information is regrettably not supplied by the SACAA due to the POPI Act restrictions.

Turning our attention to the NTCA types, two Savannah S and a single Vans RV-10 have been registered this month.

Departing our shores are a Beechcraft 1900D, ZS-EAI, that has moved to Algeria, and a Boeing 737-5Y0 ZS-TGY (25183) that has

been exported on sale to the DRC. This jet joins the fleet of a recent start-up scheduled carrier, Mont Gabaon Airlines (MG Airlines). It was delivered to Goma from OR Tambo International Airport on 15 December and entered service on 3 January on scheduled services linking Kindu with Kinshasa and Goma. This 32 year old jet has a rich history, having been delivered to China Southern Airlines in February 1992. It then joined Russian carrier Transaero’s fleet in December 2006 where it remained for 10 years. The jet was then transferred to another Russian carrier, VIM Airlines, for three months but was then sold to Africa Charter Airline in South Africa in November 2017. It operated for various carriers while in South Africa including several months with Proflight Zambia in 2023/24.

A single Sling 4 ZU-IZW moves to Australia and closes this month’s updates.

Some other notable South African aircraft developments include four Gazelle helicopters recently exported from South Africa that have been seen active in Libya operating for the Libyan National Army. The four in question, ZU-HGZ, ZR-ROO, ZU-ROU, ZU-RZR, were flown from Lanseria International Airport onboard an Ilyushin IL-76 during December 2024. The end destination was initially mentioned as being the DRC but it has since transpired that they are now in service in Libya and there is even video footage of them taking part in a parade at Smerkit Air Force Base as part of the graduation ceremony of cadets of the Libyan Armed Forces. It is not known if these helicopters have been sold or on lease to Libya.

In closing the month is a story of the sad but inevitable end of the last airworthy South African Gulfstream IIB, ZS-DJA (156). This 1975 built corporate jet was a long-time resident at Lanseria International Airport from where it departed for the last time on 27 May 2022, heading to her new owners in the USA, now with the registration N24FU. On 22 December 2024 the burnt-out wreckage of the jet was found in a field near Dolores Village in the Toledo District in southern Belize. She met the same fate so many other old Gulfstream IIs have befallen the past few years: being used for extremely profitable drug running flights that invariably end up with their burnt-out wreckage being found in some remote field in Central America.

On the commercial airline front, South African Airways continues to grow its fleet and the next arrival is expected to be the former Qatar Airways A320-232 A7-AHF (4496) that is said to become ZS-SZN. It was expected to be delivered to OR Tambo International Airport in the latter half of January 2025.

Another new jet is a Boeing 737-476F, C5-STC (24446) that arrived at OR Tambo International Airport on 11 January on delivery to Africa Air Charter. It will no doubt soon feature in this column once its registered locally.

The Belize Defence Force found the wreckage of N24FU on a makeshift airstrip in a secluded cattle pasture about 15 minutes form the Guatemalan border, an area long associated with illicit cross border activities and drug smugglers. The plane had been deliberately torched to destroy evidence. It was still registered to a company “Best Aircraft Deals LLC” (Breaking Bad?) in Salt Lake City, Utah at the time of this flight. A very sad end to this grand old lady that I was fortunately able to photograph on her departure from South Africa in May 2022.

j

The very successful Light Sport Aircraft manufacturer Flight Design has filed for insolvency. The aircraft builder says it has run out of cash because a major customer hasn’t paid its bill.

THIS DEVELOPMENT follows a string of financial troubles in the aviation industry, including bankruptcies from Hoffmann Propeller, Lilium, Sonaca, and ICON earlier in the year.

“The insolvency application became necessary because, on the one hand, an international customer has not yet paid undisputed claims in the mid-six-figure range and another payment in the mid-six-figure range was also delayed,” the company’s website notice said.

Flight Design has declared insolvency - again.

brought temporary stability, Flight Design struggled to maintain momentum with newer models like the F2 and the long-anticipated F4, a four-seat aircraft still under development.

The company is based at Kindl airfield in Hörselberg-Hainich and has production sites in Sumperk, Czech Republic, and Kherson, Ukraine.

The invasion of Ukraine meant Flight Design had to relocate its main manufacturing base to Sumperk, which affected production.

The company says it has 10 employees working in Germany, 70 in the Czech Republic and 20 in Ukraine. Since the company was founded in 1988 it has delivered more than 2,000 aircraft.

Flight Design previously entered insolvency in 2016 due to debt issues, eventually being acquired by Lift Air in 2017. While the move

Marcello Di Stefano was named the insolvency administrator and appears confident the company can emerge with some short-term financing. “The company’s order situation is good and the products have a very good reputation on the international market, and the outstanding debts are manageable,” said Di Stefano.

He said he’ll be looking for bridge money while going after the unpaid accounts. “This would make it possible to maintain the Flight Design Group with its EASA Design and Production Organisations and the F-Series and CT-Series aircraft and to finalise the existing orders and hand over the aircraft to the customers.”

• Now certified for TCAS training.

• RNAV and GNSS Certified on all flight models from single engine to turbine.

Tel: 011 701 3862

E-mail: info@aeronav.co.za

Website: www.aeronav.co.za

Airspan / Kroondal

Baragwanath - FASY

R25,80 R18,64

R29,00

Beaufort West - FABW R29,70 R 21,40

Bloemfontein - FABL R33,04 R18,74

Brakpan - FABB R33,80 R18,42

Brits - FABS

R27,60

Cape Town - FACT R33,93 R19,96

Cape Winelands - FAWN R32,00

Airspan / Kroondal

Baragwanath - FASY

Beaufort West - FABW

Bloemfontein - FABL

Brakpan - FABB

Brits - FABS

Cape Town - FACT

R27,44 R19,49

R29,00

R29,70 R 21,90

R27,60 R18,95

R32,50 R19,05

R27,60

R33,93 R19,96

Cape Winelands - FAWN R32,00

Eagle's Creek R29,50 Eagle's Creek

East London - FAEL R34,67 R18,61

Ermelo - FAEO R29,79 R23,57

Gariep Dam - FAHV R29,50 R20,00

East London - FAEL R34,67 R18,61

Ermelo - FAEO

Gariep Dam - FAHV

George - FAGG R34,57 R19,00 George - FAGG

Grand Central - FAGC R31,68 R20,47

Heidelberg - FAHG R28,90 R20,30

Grand Central - FAGC

R29,79 R23,58

R30,00 R20,00

R34,57 R19,00

R31,68 R20,47

Heidelberg - FAHG R30,00 R20,30

Hoedspruit Civil - FAHT NO FUEL NO FUEL Hoedspruit Civil - FAHT NO FUEL NO FUEL

Kimberley - FAKM NO FUEL R22,52

Kimberley - FAKM NO FUEL R22,52

Kitty Hawk - FAKT R28,90 Kitty Hawk - FAKT

Klerksdorp - FAKD R28,52 R22,42 Klerksdorp - FAKD R28,52 R22,42 Kroonstad - FAKS R27,50 Kroonstad - FAKS R27,50 Kruger Mpumalanga Intl -FAKN R35,15 R26,30 Kruger Mpumalanga Intl -FAKN R35,15 R26,30

Krugersdorp - FAKR R28,00 Krugersdorp - FAKR R28,00 Lanseria - FALA R31,17 R20,36 Lanseria - FALA

Margate - FAMG NO FUEL NO FUEL

R31,17 R20,36

Margate - FAMG NO FUEL NO FUEL

Middelburg - FAMB R29,50 R20,49 Middelburg - FAMB R29,50 R20,50 Morningstar R29,50 Morningstar R29,50 Mosselbay - FAMO R34,50 R27,40 Mosselbay - FAMO R33,00 R23,50

Nelspruit - FANS R32,26 R23,00 Nelspruit - FANS

R29,96 R20,13 Oudtshoorn - FAOH R33,10 R23,05

Parys - FAPY R26,38 R19,22

Pietermaritzburg - FAPM R29,00 R22,40

Pietersburg Civil - FAPI R29,45 R22,15

Plettenberg Bay - FAPG NO FUEL NO FUEL

Port Alfred - FAPA

R33,50

Port Elizabeth - FAPE R30,94 R20,64

Potchefstroom - FAPS R25,80 R18,64

Rand - FAGM R33,50 R23,50

Robertson - FARS R31,90

Rustenburg - FARG R29,50 R21,95

Secunda - FASC R29,33 R21,28

Skeerpoort *Customer to collect R23,56 R16,40

Springbok - FASB R29,50 R23,50

Springs - FASI R37,25

Stellenbosch - FASH R33,00

Swellendam - FASX R29,50 R20,00

Tempe - FATP R26,86 R18,71

Thabazimbi - FATI R26,30 R19,14