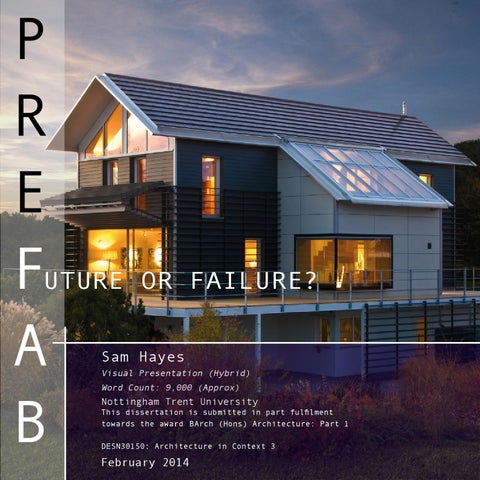

P R E FUTURE OR FAILURE? A B

Sam

Hayes

Visual Presentation (Hybrid)

Word Count: 9,000 (Approx)

Nottingham Trent University

This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment towards the award BArch (Hons) Architecture: Part 1

DESN30150: Architecture in Context 3

February

2014