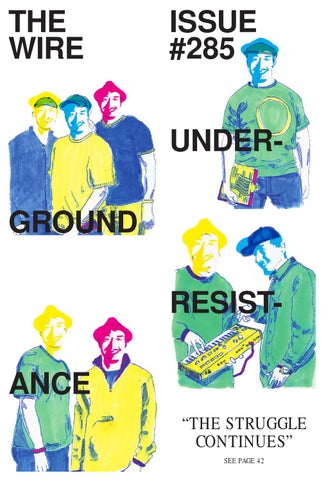

THE WIRE #285 (redesign) — I created this magazine as a school assignment in which we had to give a personal, original way to reinterpret the wire magazine by inserting yourself (face and personality) as an artist in the entire edition. It thus gave the option to be creative with grids (considering the magazine contains all sorts of different material, such as articles, interviews, …) and also reinterpret the imagery which was available. As for my version, I tried to combine the strong, bold typography with the hard, colourful images which I are all hand drawn.