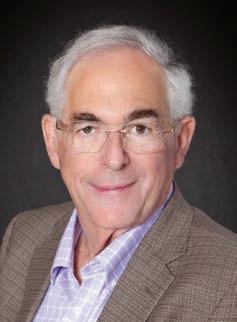

Bexar

County Judge

PETER SAKAI

Family Judge and Chief Executive of the County

THANK YOU FOR YOUR MEMBERSHIP— CHECK OUT YOUR NEW MEMBER BENEFITS!

County Judge

Family Judge and Chief Executive of the County

THANK YOU FOR YOUR MEMBERSHIP— CHECK OUT YOUR NEW MEMBER BENEFITS!

Thank you for being a San Antonio Bar Association member. Use your benefits and connect to your professional community!

The San Antonio Bar Association (SABA) is where San Antonio legal professionals belong and are valued. SABA members hold the key to professional development and profitable business growth. Thank you for being a member of the most collegial bar association in Texas!

• The SABA Directories – Cited by members as the #1 resource, the Member Directory and the new Court & Government Directory are live and mobile-optimized with “click to call” features. No more typing phone numbers! A Vendor Directory is coming in the fall.

• The NEW SABA Member Center – Need to scan or make a copy? Need a quiet spot to draft an email? Want to join a friend for a coffee? Your Member Center has these and many other benefits!

• Lawyer Referral Service (LRS) – SABA members save on marketing, grow their client base, and streamline their intake procedures.

• Time-sensitive court announcements and notices – SABA members are the first to receive this type of information.

• Continuing Legal Education (CLE) – We offer convenient access and affordable education.

• Networking – Grow your network through numerous social mixers and celebratory events throughout the year.

Conveniently located across the street from the Bexar Judicial Complex, SABA members can enjoy their private space to meet colleagues, earn CLE, and access law practice resources.

View a 30-second Member-benefit highlight reel by scanning the QR code.

“His

“A

“One

San Antonio Lawyer® is published bimonthly. Copyright ©2024 San Antonio Bar Association. All rights reserved. Republication of San Antonio Lawyer content, in whole or in part, is prohibited without the express written permission of the San Antonio Bar Association. Please contact Editor in Chief Sara Murray regarding republication permission.

Views expressed in San Antonio Lawyer are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the San Antonio Bar Association. Publication of an advertisement does not imply endorsement of any product or service. San Antonio Lawyer, the San Antonio Bar Association, and the Publisher reserve the right to edit all materials and assume no responsibility for accuracy, errors, or omissions. San Antonio Lawyer and the Publisher do not knowingly accept false or misleading advertisements or editorials, and do not assume any responsibility should such advertising or editorials appear.

Contributions to San Antonio Lawyer are welcome, but the right is reserved to select materials to be published. Please send all correspondence to info@sabar.org

Advertising Inquiries:

Monarch Media & Consulting, Inc.

Archives of San Antonio Lawyer are available at sabar.org. Send address changes to the San Antonio Bar Association.

Chellie Thompson 512.293.9277 chellie@monarchmediainc.com

Publication Design and Production: Monarch Media & Consulting, Inc.

Editor in Chief Sara Murray

Articles Editor Natalie Wilson

Departments Editor Leslie Sara Hyman

Editor in Chief Emerita Hon. Barbara Nellermoe

Monarch Media & Consulting, Inc. 512.293.9277 | monarchmediainc.com

Design Direction Andrea Exter Design Sabrina Blackwell

Advertising Sales Chellie Thompson

Sara Murray, Chair

Pat H. Autry, Vice-Chair

Barry Beer

Amy E. Bitter

Ryan V. Cox

Paul Curl

Michael Curry

Shannon Greenan

Stephen H. Gordon

Leslie Sara Hyman

Rob Killen

Thomas Lillibridge

Rob Loree

Lauren Miller

Curt Moy

Harry Munsinger

Hon. Barbara Nellermoe

Steve Peirce

Donald R. Philbin

Clay Robison

Regina Stone-Harris

ileta! Sumner

Natalie Wilson

Ex Officio

Steve Chiscano

For information on advertising in San Antonio Lawyer: Call 512.293.9277

Chellie Thompson, Monarch Media & Consulting, Inc. chellie@monarchmediainc.com

President

Steve Chiscano

President-Elect

Patricia “Patty”

Rouse Vargas

Treasurer

Nick Guinn

Secretary

Jaime Vasquez

Immediate Past President

Donna McElroy

100 Dolorosa, Suite 500, San Antonio, Texas 78205 210.227.8822 | sabar.org

Directors (2023-2025)

Kacy Cigarroa

Melissa Morales Fletcher

Elizabeth “Liz” Provencio

Krishna Reddy

Directors (2022-2024)

Emma Cano

Charla Davies

Charles "Charlie" Deacon

Jorge Herrera

Executive Director

June Moynihan

Soledad Valenciano, Melanie Fry, and Jeffrie Lewis

Special recognition

Sara, thanks for doing such a consistently great job with this publication. I write to especially compliment the articles authored by ileta Sumner, and most recently, the article regarding the origin of Juneteenth. Her voice is sorely needed in our community—and her grasp of relevant history is impressive—so thanks for including her writings for all of us to enjoy. Have a great summer!

June 4, 2024, email to Editor in Chief Sara Murray from Kevin Young, Prichard Young, LLP

Congratulations!

Congratulations to Steve Peirce and ileta! Sumner—long-time members of the SABA Publications Committee and contributors to San Antonio Lawyer—who recently received State Bar of Texas Stars of Texas Bars Awards for their outstanding articles published during the period from May 1, 2023 — April 30, 2024. Steve won the award for the Best General Interest Story:

Steve A. Peirce, Judge Fred Biery: While Observing the Human Condition, He Also Discovered Himself, San Antonio Lawyer, July–August 2023, pages 6–8 and 10–14.

Ileta! won the award for the Best News Article: ileta! A. Sumner, Bocas Cerradas—¡No Mas! The Reemergence of Emmett Till, San Antonio Lawyer, May–June 2023, pages 23–25.

Please send letters to the editor to Sara Murray, Editor in Chief, at smurray@langleybanack.com. The San Antonio Bar Association thanks our editors, board of editors, and contributing volunteer writers for bringing an unparalleled quality of editorial content to our valued readers.

By Steve A. Peirce

Meetings of the Bexar County Commissioners’ Court are held at the Double-Height Courtroom at the Bexar County Courthouse, aptly named because its ceiling is two floors high. Running the meeting is Bexar County Judge Peter Sakai, and sitting on both sides of him are four County Commissioners. Judge Sakai functions as the Chief Executive of the County, but he is only one of five votes on the Commissioners’ Court. On my visit, in the middle of Fiesta, the meeting starts with an invocation; a passionate plea from Pastor Shetigho Nakpodia of Redeemer’s Praise Church, for a higher being to bestow blessings on all present and those not present as well. The Pledge of Allegiance follows.

The meeting starts with the fun stuff: proclamations, awards, recognition of service, photos, and many incantations of “Viva Fiesta.” Then the meeting turns to business, with an agenda that runs seventeen pages of singlespaced items. The process is formal and informal at the same time, and Judge Sakai smiles as he seamlessly runs through the agenda while giving each commissioner and the agenda presenters the floor to speak. The mood is relaxed and civil. No one is talking over anyone else or losing their cool. The professional staff sometimes chimes in with information or advice. Some on the Court enjoy snacks during the process. The County has a $3 billion budget and about 5,000 employees, and most of the decisions are about how to apply funds for various initiatives. Among other things, the Court considers funding capital improvements to the infrastructure of La Villita, support for a UTSA sports facility, and how to deal with a recent unfunded mandate from the Texas Attorney General for statistical information and digitalization of court records at an estimated cost of about $1 million.

The McAllen Farm Boy

Judge Sakai’s office on the tenth floor of the Paul Elizondo Tower has a magnificent view southward. Over 230 miles in that direction lies the city of McAllen, Texas, where Sakai was born and raised, the eldest child of Yukata “Pete” Sakai and Rose Marie Kawahata Sakai, second generation “nisei” Japanese Americans. Both sides of Peter Sakai’s family were farmers. His grandparents were Japanese immigrants, known as “issei;” the paternal side farming the California Imperial Valley, and the maternal side farming the Texas Rio Grande Valley. Judge Sakai’s father Pete Sakai, became a farmer in McAllen, and his children, including Peter, worked on the farm picking onions, lettuce, and cabbage alongside Mexican farmhands. “My grandparents spoke Japanese first, then Spanish, then a little English,” says Sakai. “I speak English first, then ‘poquito’ Tex-Mex Spanish, and I know some Japanese words.”

Sakai picked up his Spanish (first, the cuss words), something of a necessity in the majority Mexican American part of the state, from his classmates and the farm workers. At school, those cuss words were often directed at him for being Japanese, but he fought back (sometimes inappropriately) and gained respect. He spoke Spanish with the farm workers, “doing backbreaking work, from sun-up to sun-down,” he says. “After years of working on the farm, as a high schooler, I asked my dad if I could be paid. His response was, ‘You get free room and board, and if you want to get paid, get a job somewhere.’ So, I went to work in a shoe store. Farm work is the Lord’s work, but I would never go back to it.”

Judge Sakai recounts his high school days. “In the early 1970s, I was an unfocused student in high school with above-average grades, and a 155-pound center and linebacker on the football team. I was also a student council class officer, but people who knew me in high school would be surprised about where I ended up.” This brings to mind the Kurt Vonnegut quote that “true terror is to wake up one morning and realize that your high school class is running the country.” Since January of 2023, Peter Sakai has served as Bexar County Judge, doing his part to help run the country, after a long and storied career as a lawyer and trial judge. As evidenced herein, his classmates most assuredly should feel more pride than terror.

In everyone’s life there are turning points – life-changing events, experiences, and decisions that make us wonder what our lives would have been like without them. With Peter Sakai, it was the experience of his father, with whom he often struggled, the help of his friends, and his decision to stay in San Antonio.

In the Summer of 1971, seventeen-year-old Peter was a longhaired opposer of the Vietnam War, and would have been grooving to the tunes on AM radio on a family road trip to California. Peter’s dad, a no-nonsense crew-cut conservative World War II veteran with little patience for the hippie culture, pulled the station wagon into an old Indian Reservation in Poston, Arizona. Viewing some slabs in the triple-digit heat of the barren Arizona desert, he informed Peter, “This is where I grew up.”

Judge Sakai looks out over downtown San Antonio from the terrace of the Commissioners Courthouse.

In the weeks following the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, mass hysteria ensued, taking the form of an irrational fear of all Japanese citizens. Faced with intense political and military pressure, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, permitting the Secretary of War to send Japanese Americans to internment camps. Officially, the order authorized the Secretary to exclude all persons from designated military areas and to place such persons in other accommodations. It was mostly used on Japanese Americans and along the Pacific Coast, which was designated a military area, where many Japanese Americans lived, and where sabotage was feared along the coastal shipping areas. Japanese American families were given as little as forty-eight hours’ notice to dispose of their property and report to a train to take them to “assembly centers,” such as racetracks or fairgrounds, with ultimate disposition at one of several “relocation centers,” which came to be known as internment camps (some were taken directly to internment camps).

Most internment camps were in desolate, remote areas, and the housing was typically army-style barracks with shared facilities, little privacy, and little protection from the elements.

Poston, Arizona, contained three internment camps, holding over 17,000 Japanese American internees. All told, almost 120,000 Japanese Americans were sent to internment camps, about 70,000 of whom were American-born, and about 17,000 of whom were children under ten. It is estimated that about $400 million in property was lost by the interned families. They were given no hearing, no due process, and no appeal prior to their loss of property and liberty. Their only “offense” was that they happened to be at least 1/16th Japanese, and that they lived in a designated area. On the legal side, the Supreme Court upheld Executive Order 9066 in Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944).

Closer to home, the Japanese Tea Garden—an old stone quarry in San Antonio, which was maintained as a beautiful garden and home by the family of Japanese artist Kimi Eiso Jingu—was renamed the Chinese Tea Garden. The Jingu family was evicted, and a Chinese family was installed in their place. And Texas itself had its own internment camp in Crystal City, which was unique in that it held Japanese, German, and Italian Americans together. This camp was later the subject of the bestselling book The Train to Crystal City.

“When my dad was in high school, [he] and his family were taken to the Poston internment camp because they were Japanese in the Imperial Valley,” says Judge Sakai. “Because my dad’s family were poor tenant farmers, their living conditions at the camp were almost a step up, according to my dad.” As part of the internment process, the government issued a questionnaire to all interned men over the age of seventeen. Two of those questions were whether you were willing to serve in the U.S. armed forces, and whether you swore unqualified allegiance to the United States. “My paternal grandfather was known as one of the ‘no-no boys,’ because he answered ‘no’ to both those questions,” says Judge Sakai. “As a result, he was shipped off to a secured segregation center in New Mexico. They later let him return to Poston,” Sakai adds. “As soon as he was old enough, my dad joined the Army to get out of the camp. He became a translator as part of the U.S. occupation force in Japan after Japan’s surrender in 1945. My mother’s family, who lived in the Rio Grande Valley, were not interned.”

Judge Sakai recalls, “The stopover at Poston and my dad’s stories of the internment made a lifelong impression on me. As I went through life and began to study law,

it made me think about due process, our Constitutional rights, the rule of law, and how to defend it.” By the end of 1945, the internment camps were closed, with Poston being closed in 1946. It took a good while for further corrective action to be taken. In 1971, when the Sakai family stopped off at Poston, Executive Order 9066 was still in place; it was not repealed until 1976. A 1982 Presidential Commission Report found that racial prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership were the underlying causes of the internment program. Locally, the Chinese Tea Garden was finally renamed the Japanese Tea Garden in 1984. The federal government gave Japanese survivors of the internment an apology and some small reparations in 1988. And in 2018 the Supreme Court finally abrogated its Korematsu opinion in Trump v. Hawaii, 585 U.S. 667 (2018), while upholding a travel ban from certain Muslim majority countries.

When Peter graduated high school in 1972, like many kids of non-college educated parents of that time and place, he had no mentors and got little guidance on what to do with his life. He only knew he wanted to go to college. So he enrolled at UT-Pan American in Edinburg (now UT Rio Grande Valley) with no idea where he was headed. Sometimes, a young person just needs a little confidence. A friend told him that he was “too smart” and that he should go to the University of Texas in Austin. Taking that advice to heart, he transferred to UT Austin, and ultimately got a B.A. in Government in 1976. Still uncertain about what to do, he met another friend who lived in his apartment complex. He recounts that: “She was from an affluent Dallas Highland Park family, and she asked me what I was going to do and told me that she was going to take the Law School Admissions Test,” says Judge Sakai. “I didn’t even know what that was, but she gave me the LSAT workbook and tutored me for the test. I took the test and was accepted into UT Law School, the only Asian American in the law school at the time.”

“At UT Law School, we formed an intramural softball team called the Chicano Bears, consisting of me, one Anglo, and the rest Hispanics,” says Sakai. “Lawyers Fidel Rodriguez and Oscar Villareal were also on that team. We had several players who had played college sports, and we were one of the top teams on campus.” Sakai jokingly takes partial credit for starting the fajita craze in the late-1970s. “I was the only Asian in the Chicano Law Student Association. Being from McAllen, I knew how to cook fajitas, and I was

the chief fajita cook for our fundraisers. At the time, fajitas were considered a lower-class meat, but they sure became popular.” But he wasn’t as successful with his grades as he was on the softball diamond and with the grill. “In my first year, I never studied so hard to do so poorly, and considered dropping out,” he says. “But I became friends with (future federal judge) Orlando Garcia, who was a year ahead of me at

UT Law, who told me that I belonged and to hang in there. He became my mentor, and my grades went up.”

After graduating from law school in 1979, Peter Sakai deferred his job search in order to study for the bar exam. He passed the bar exam but had some difficulty finding

By County Judge Peter Sakai

1. “I Am, I Said” by Neil Diamond

The lyrics speak to me. “ . . . a frog who dreamed of being a king and then became one . . . /If you talk about me/The story is the same one.”

2. “Sweet Caroline” by Neil Diamond

Greatest song by Neil to sing along with at any time. “Hands/ Touching hands/Reaching out/Touching me, touching you.”

3. “Fire and Rain” by James Taylor

This song reminds me of the long hot days in the Rio Grande Valley on the farm and football fields where there were “sunny days that I thought would never end.”

4. “Cat’s in the Cradle” by Harry Chapin

Chapin’s best song—a poignant story about the missed opportunities of a father-son relationship and the consequences thereof.

“He’d grown up just like me/My boy was just like me.”

5. “Time in a Bottle” by Jim Croce

“But there never seems to be enough time/To do the things you want to do once you find them.” The song is a message about how precious life is and how we all need to appreciate what we have while we have it.

6. “Mercy, Mercy Me (The Ecology)” by Marvin Gaye

In the 70’s, this song mourned the destruction of the environment in a modernized society. It still applies today. Marvin Gaye was one of Motown’s best.

7. “All Day Music” by War

Best cruising’ song in my time. “Music is what we like to play? All day . . . /To soothe your soul.”

8. “Wake up Everybody” by Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes

A song that calls for action. “The world won’t get no better/We gotta change it/Just you and me.” The lyrics still touch on everyday issues that are relevant even today. Another great Motown singer, Teddy Pendergrass.

9. “Europa” and “Moonflower” by Santana (Carlos Santana)

Carlos Santana makes his guitar sing in the most beautiful instrumental songs that no one else does. Carlos is still going strong today.

10. “Colour my World” by Chicago

Some of the shortest lyrics, but one of the greatest love songs, especially for those junior high school dances. Chicago songs were on the main playlist for the local band, “Court Jesters” (RIP Judge Sol Casseb and Steve Barrera).

11. “Easy to be Hard” by Three Dog Night

The lyrics reflect on the seemingly heartless and cruel nature of people. The song questions how individuals can be indifferent toward the suffering of others and highlights how it is “easy to be” cold and callous.

12. “Suavecito” by Malo

Greatest song by a Chicano Band. (Jorge Santana—brother of Carlos Santana—was the leader of the band).

13. “Las Nubes” by Little Joe & La Familia

A legendary Tex-Mex song which narrates a bittersweet tale of lost love, showcasing the struggles and resilience of the Latin community. Little Joe Hernandez is the epitome of the Brown Soul. Remember, I grew up in The Valley.

Judge and Mrs. Sakai in the Commissioners Court ready room, where the Judge reflects before each meeting

employment. “By the Spring of 1980, I was a licensed attorney living with my brother in Austin and working at the mall,” he said. “I submitted resumes everywhere. No one would take my calls, and there were no job offers.”

Then he got a call from a law school friend, Ron Mendoza, who was a mid-level prosecutor in the Bexar County District Attorney’s office, about an opening there for an entry level position. At about the same time, another law school friend, Wayne Olson, called him about a position with the City Attorney’s Office in Fort Worth. “The D.A. job paid $13,200, but the Fort Worth job paid $17,500,” says Sakai. “I almost blew it at the D.A. job interview. They offered me the job, and I asked if I could have some time to think about it. I really wanted to be a trial lawyer, and though the Fort Worth job paid more, the best I could hope for was misdemeanor municipal court work. So, I took the position with the D.A.’s office in the hopes of advancing to a first-chair felony prosecutor,” says Sakai. “I never regretted that decision. Never make your decisions based on money alone. Choose your passion,” he adds.

The decision worked out, and Peter Sakai was on his way. Within two years, he married Raquel “Rachel” Dias-Sakai, and they had their first child. They would end up having the common interest of working with children and families. Rachel was the daughter of a Laredo juvenile officer who often brought delinquent minors home so they would not have to share a jail cell with an adult. Decades later, Rachel has retired after having been an educator, counselor, and administrator at Harlandale ISD for thirtytwo years, Director of the Gateway to College

at Palo Alto College, and working as a teacher/ sponsor at Providence Catholic School. She was inducted into the San Antonio Women’s Hall of Fame and was also named as a 2022 recipient of their Volunteerism award. She remains a volunteer in “Youth Do Vote,” an organization that helps demystify voting and elections for young people through voter registration, voting education, and recruitment of student election clerks. Together, Peter and Rachel have two kids, George and Elizabeth. They are also blessed to have three wonderful grandchildren, Grayson Sakai, Jackson Sakai and Grayson McNeil.

At the D.A.’s office, Sakai became an appellate attorney, and was later promoted to Chief of the Juvenile Section, beginning his decades-long career as a specialist in family and children’s issues. By 1983, Sakai had opened a solo practice, where he handled court-appointed child abuse and neglect cases. In 1989, he was named the Juvenile Master in the 289th District Court. In 1995, he was unanimously appointed by the civil court judges as the Associate Judge in the Bexar County Children’s Court. The retirement of his judicial mentor, Judge John J. Specia, left an opening for the 225th District Court, and Sakai was elected to that bench in 2006. Sakai was reelected as Judge of the 225th until the end of 2022, when he briefly retired before deciding to run for his current position as County Judge.

Prior to being elected County Judge, Peter Sakai was best-known as the Bexar County Children’s Court Judge, a national model for handling child abuse and neglect cases, and foster placement and adoptions of children. It is a challenging and emotionally taxing job to try to fix broken families and place these traumatized children in a better situation; incredibly rewarding when it works and devastating when it does not. “The typical case is one or both parents are alcohol or drug abusers, and there may be physical or sexual abuse of a child,” says Judge Sakai.

One such case that nearly ended Judge Sakai’s career in the mid-2000s was that of fourteen-month-old baby girl who had been removed from her home after her mother tested positive for drug use. Judge Sakai signed off on an agreed order that allowed the girl to go home. The child died after being beaten by her mother, and the mother was later given a life sentence. The case left Judge Sakai so distraught that he seriously thought he would leave the judiciary. “I had to take a sabbatical to deal with the pain of that case,” Sakai admits. “I am a

• Experienced, having conducted more than 25,000 mediations since 1989 with more than 850 years’ experience practicing law

• Committed to the mediation process and devoted to the ethical practice of law

• Covered by the AAM Member Insurance Group Policy, an arbitrator and mediator professional liability insurance

For more information, contact the local San Antonio Chapter. www.attorney-mediators.org/SanAntonioChapter Gary Javore - gary@jcjclaw.com

Michael J. Black

210.823.6814

mblack@burnsandblack.com

Paul Bowers

713.907.7680

paul@ptbfirm.com

John K. Boyce, III 210.736.2224

jkbiii@boyceadr.com

Leslie Byrd 210.229.3460

leslie.byrd@bracewell.com

Kevin Chaney 210.889.4479

kevin@kevinchaneylaw.com

Debbie Cotton 210.338.1034

info@cottonlawfirm.net

Michael Curry

512.474.5573

mcmediate@msn.com

Aric J. Garza

210.225.2961

aric@sabusinessattorney.com

Charles Hanor

210.829.2002

chanor@hanor.com

Gary Javore

210.733.6235

gary@jcjclaw.com

Alex Katzman

210.979.7300 alex@katzmanandkatzman.com

Daniel Kustoff 210.614.9444 dkustoff@salegal.com

J.K. Leonard 210.445.8817 jk@jkladr.com

Cheryl McMullan, Emeritus 210.824.8120 attyelder@aol.com

Dan Naranjo 210.710.4198 dan@naranjolaw.com

Patricia Oviatt 210.250.6013 poviatt@clarkhill.com

Jamie Patterson 210.828.2058 jamie@braychappell.com

Diego J. Peña 817.575.9854 diego@thepenalawgroup.com

Don Philbin 210.212.7100 don.philbin@adrtoolbox.com

Edward Pina 210.614.6400 epina@arielhouse.com

Richard L. Reed, Sr. 210.953.0172

rick.reed@steptoe-johnson.com

Wade Shelton

210.219.6300

wadebshelton@gmail.com

Thomas Smith 210.227.7565

smith@tjsmithlaw.com

Richard Sparr 210.828.6500 rsparr@sparrlaw.net

John Specia 210.734.7092 jspecia@macwlaw.com

Phylis Speedlin 210.405.4149

phylis@justicespeedlin.com

Lisa Tatum

210.249.2981 ltatum@tatum-law.com

William Towns

210.819.7453

bill.towns@townsadr.com

James Upton 361.884.0616 jupton@umhlaw.com

person of faith. I work hard, and at the end of the day, I try to leave it behind and recharge my batteries,” says Sakai.

But it is the success stories, as Judge Sakai puts it “to help the least of us” that make his twentysix years as a District Court Judge like none other. He ran the Family Drug Court, which is a program to rehabilitate parents with substance abuse issues, that among other things included a contract with the parents, frequent drug testing, and a weekly “truth telling” session with Judge Sakai. He also ran the Early Childhood Court, whose mission it is to establish a comprehensive, integrated, and coordinated systems approach to helping families within the community. This approach includes developing, supporting, and facilitating services and tailoring those services to the needs of the child(ren) and family. He ran the College Bound Docket, which provides barrier-free access to education and housing for foster children, and was instrumental in the Thru Project, which helps foster kids go to college when they age out of the foster care system. From 1995–2005, adoptions of Bexar County foster children increased by 1000 percent under Judge Sakai’s leadership.

To Sakai, few things are as satisfying as seeing a child who had been in his court reach a level of success and give back to the community. “A Bexar County Deputy approached me and said, ‘I was a foster kid in your court,’” says Sakai. “She said, ‘My parents abandoned me. I talked you out of keeping me in the foster system. You made a deal with me to finish school and come back with a plan on who would be responsible for me. I was emancipated and lived with my sibling and got a job,’” Sakai explains. “Another case was a 15-year-old boy who was the parental figure in his house because his mother was mentally ill. He ran with the gangs and wouldn’t follow the rules. He was a gifted athlete, but he had an attitude,” Sakai recalls. “I had him come in and see me every four months. I told him that he was a leader, in his family and as an athlete. Years later, I saw him at an event where he was a volunteer at CASA (Child Advocates San Antonio).” Judge Sakai says that “after twenty-six years working with foster kids, you have to be able to listen to them and understand that most of them are in circumstances beyond their control. I have tried to impress upon the children the values that my parents taught me: Work hard and follow your dreams; be honest; do things with a sense of integrity; be humble; don’t discriminate; don’t disrespect; and remember where you came from.”

The Bexar County Judge Sakai won election as Bexar County Judge in November of 2022, and was sworn in on

January 1, 2023—appropriately, by his old law school mentor, Judge Orlando Garcia. His immediate goals are lofty: create a public Internet Utility to expand high-speed internet accessibility to all Bexar County residents; create a Public Health Division for emergency readiness for public health crises like pandemics, natural disasters, and terrorist attacks; provide more beds for those with mental illness; support mental health resources in the schools; bring a robust jury system back on line and move cases along; and, certainly not least, facilitate voter registration and easy access to the polls.

During Judge Sakai’s first eighteen months on the job, the County has already accomplished a lot: JCB, the world’s largest privately owned manufacturer of construction and agricultural equipment, is building a new factory on the South Side, adding an estimated 1,500 jobs. Industrial Commercial Properties will take over the old Rackspace headquarters on Walzem Road, for mixed use, retail, and light industrial use. There are fifty new Bexar County deputy positions with a substantial pay hike for Sheriff’s officers, and a joint project with the City of San Antonio’s law enforcement officers to come up with more than thirty actions to address violent crime. The County has contributed more than

$30 million to the Spurs, UTSA, and Texas A&M San Antonio. More funding is being secured for beds to house the mentally ill, rather than placing them in jail. Another $20 million has been provided to area school districts to address mental health concerns stemming from the pandemic’s aftermath.

Though his softball playing days are behind him, he still listens to the AM radio hits of the Sixties and Seventies. He also relaxes by reading his favorite biographies and watching sports. He’s been to several quinceaneras and every Fiesta event he could get to, and he can trade notes with you on the best Mexican food places on the South Side of San Antonio. He’s doing the same job he’s done his whole career: trying to do what’s best for families. There’s a lot more families now, and he’s up for the task.

Steve A. Peirce is Of Counsel in the San Antonio Office of Norton Rose Fulbright. He can be reached at 210-2707179 or at steve.peirce@ nortonrosefulbright.com Many thanks to Judge Peter Sakai and Communications Director Jim Lefko for sharing their time.

6 PM Reception & Silent Auction

7 PM Dinner & Awards Program

9 PM Blues Lounge Entertainment & Dessert

ATTIRE Evening Gown, Cocktail / Black Tie, Dark Suit

SABA Lifetime Achievement Award -

Joe Frazier Brown Sr. Award of Excellence

The Honorable Charlie Gonzalez

SAYLA Outstanding Young Lawyer

Cassie Garza

SAYLA Outstanding Mentor

Robert Soza Jr.

SAYLA Liberty Bell

The Honorable Lucy Adame-Clark

Incoming President

Patricia Rouse Vargas

Outgoing President

Steve Chiscano

SPONSOR AND REGISTER ONLINE

Scan the QR code or visit sabar.org/2024Gala for more information.

By The Honorable Xavier Rodriguez

Editor’s Note: Part I of this series, published in the May-June 2024 issue of San Antonio Lawyer, provided a basic understanding of the relevant technology, including potential benefits and pitfalls about which lawyers should educate themselves. Part II discusses ethical and practical considerations, as well as the implications for using AI in specific practice areas.

This article was previously published as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the Practice of Law in Texas, 63 STXLR 1 (Fall 2023) and is reprinted with permission.

As stated in the introduction to Part I of this series, lawyers are going to be required to adapt to the growth of artificial intelligence (AI) applications, and to determine when and if to incorporate AI into their practice. In doing so, attorneys must evaluate the benefits and risks of using AI tools and navigate how to employ those tools in compliance with ethical standards.

Texas Disciplinary Rule of Professional Conduct 1.05 provides that an attorney generally may not reveal confidential information. Protective orders issued by individual courts impose even more stringent requirements—including, for instance, that attorneys verify the permanent destruction of discovery materials at the end of a case. Attorneys considering using AI platforms should take care not to disclose confidential information inadvertently by inputting such information into a prompt or uploading confidential information into the AI platform for processing, particularly when the AI system is open source, such as the free version of ChatGPT, and the terms of service do not guarantee confidentiality.

Many AI platforms may save data, such as query history, to train and improve their models. Employees working from “free” AI platforms could

potentially be exposing client sensitive data or attorney work product. Some of these free AI tools may use inputted information to further train their models, thus exposing client confidential information. Other AI platforms may not use prompts or inputted data to train. If using paid subscription services, an argument exists that such confidentiality concerns are mitigated due to the terms of service agreements entered with those paid commercial providers.1 Another matter, however, is the concern that exists with any third-party provider—that is, the potential that the AI provider is itself hacked in a cybersecurity incident and client data is taken. As always, due diligence must be exercised to satisfy that reasonable security measures are in place with any third-party provider. Further, sometimes additional requirements are imposed on the parties, such as an obligation to destroy information upon the conclusion of a matter. Sometimes that obligation is mandated contractually or sometimes included in a protective order or other discovery stipulation or protocol. A lawyer uploading documents into an AI tool may be unable to certify that the information was destroyed unless it confirms that this is covered by the platform’s terms of service.

On the other hand, AI can be used to secure information sharing and address privacy concerns. AI-powered redaction can automatically identify personally identifiable information (PII) and efficiently redact a large volume of documents.2 AI-powered redaction reduces the risk of accidentally disclosing sensitive data because of human error. An attorney using AI platforms and redaction software must weigh the benefits and risks associated with both.

Law firms (and corporations) should consider implementing an AI policy to provide guidance to their employees on the usage of AI. At the end of the spectrum, some firms may completely ban the use of AI platforms. As discussed in this article, this approach may be largely unworkable, and fail to prepare the law firm for the realities of the

modern practice of law. A better approach may be to instruct employees that they are responsible for checking any AI’s output for accuracy; they should consider whether the output of any AI platform is biased, that all appropriate laws be complied with, and they evaluate the security of any AI platforms used before inputting any confidential information.3

Although AI tools are vastly improving, attorneys should never file any AI-generated document without reviewing it for accuracy. This includes not only checking to ensure that the facts stated are correct and that legal authorities cited are accurate, but that the quality of analysis reflects good advocacy. Texas Rule of Civil Procedure 13 provides that by filing the document, attorneys certify “that they have read the pleading, motion, or other paper; that to the best of their knowledge, information, and belief formed after reasonable inquiry the instrument is not groundless and brought in bad faith or groundless and brought for the purpose of harassment.” Texas Disciplinary Rule of Professional Conduct 3.03 states that a “[l]egal argument based on a knowingly false representation of law constitutes dishonesty toward the tribunal.” As a result, if lawyers are already required to make a reasonable inquiry, it is likely unnecessary for judges to issue additional standing orders requiring lawyers to declare whether they have used AI tools in preparing documents and certifying that they have checked the filing for accuracy. What remains unclear is whether AI platforms are nonlawyers requiring supervision as contemplated by Texas Disciplinary Rule of Professional Conduct 5.03. It is also uncertain whether negligent reliance on AI tools can establish a violation of these rules, and whether lawyers must exercise “supervisory authority” over the AI platform, such that the lawyer must make “reasonable efforts” to ensure that the AI platform’s output is compatible with the attorney’s professional obligations. The Rules Committees and the Committee on Professional Ethics may wish to consider strengthening the language of these rules to clarify their scope.4

While there has already been substantial publicity about inaccurate ChatGPT outputs and why attorneys must always verify any draft generated by any AI platform,5 the bar must also consider the impact of the technology on pro se litigants who use the technology to draft and file motions and briefs.6 No doubt pro se litigants have turned to forms and unreliable internet material for their past filings, but ChatGPT and other such platforms may give pro se litigants unmerited confidence in the strength of their filings and cases, create an increased drain on system resources related to false information and nonexistent citations, and result in an increased volume of litigation filings that courts may be unprepared to handle. As nonlawyers, pro se litigants are not subject to the Rules of Professional Conduct, but they remain subject to Tex. R. Civ. P. 13. The current version of Rule 13, however, requires that the pro se litigant arguably know, in advance of the filing of a motion, that the pleading is groundless and false. The Texas Supreme Court Rules Advisory Committee may wish to consider whether Rule 13 should be modified.

Generally, “[r]elevant evidence is admissible.”7 Lawyers who intend to offer AI evidence, however, may encounter a challenge to admissibility with an argument that the AI evidence fails the requisite authenticity threshold,8 or should be precluded by Rule 403 (“[evidence] may [be] exclude[d] . . . if its probative value is substantially outweighed by [the] danger of . . . unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues, [or] misleading the jury . . . .”).9

Although the current version of the Rules of Evidence may be flexible enough and sufficient to address challenges to the introduction

of AI-created evidence, the rules of procedure or scheduling orders should ensure that adequate deadlines are set for any Daubert hearing. “[J]udges should use Fed. R Evid. 702 and the Daubert factors to evaluate the validity and reliability of the challenged evidence and then make a careful assessment of the unfair prejudice that can accompany the introduction of inaccurate or unreliable technical evidence.”10

AI evidence may require that the offering party disclose any training data used by the AI platform to generate the exhibit. If a proprietary AI platform is used, the company may refuse to disclose its training methodology or a protective order may be required. Courts are split on how to treat platforms using proprietary algorithms. In a case out of Wisconsin, a sentencing judge used a software tool called Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS), which uses a proprietary algorithm, to sentence a criminal defendant to the maximum sentence.11 In that case, the Supreme Court of Wisconsin held that the circuit court’s consideration of a COMPAS risk assessment at sentencing did not violate a defendant’s right to due process because the circuit court explained that “its consideration of the COMPAS risk scores was supported by other independent factors” and “its use was not determinative in deciding whether [the defendant] could be supervised safely and effectively in the community.”12 Coming to the opposite conclusion, a district court in Texas held that Houston Independent School District’s (HISD) value-added appraisal system for teachers posed a realistic threat to protected property interests because teachers were denied access to the computer algorithms and data necessary to verify the accuracy of their scores which was enough to withstand summary judgment on their claim for injunctive relief under the Fourteenth Mention this ad and receive 20% off your first invoice.

Your IT Solutions Experts who can help with:

• HIPPA Compliance (TX HB300 applies)

• Cloud: storage, files, computers, servers

• Computers: repairs, upgrades, purchases, encryption

• Servers: setup, repairs, maintenance, purchases

• Email: domains, migration, backup, encryption

• Office 365: email, OneDrive, backup and Office software

• VoIP phones: includes Quality of Service (QoS) and backup internet

• Network: devices, setup, repairs, maintenance

• Call when you need us or customized service options available

• Remote and on-site support, antivirus programs, virus removal, maintenance www.pstus.com • 210-385-4287 support@pstus.com

Amendment.13 AI evidence requires a balancing between protecting the secrecy of proprietary algorithms developed by private commercial enterprises and due process protections against substantively unfair or mistaken deprivations of life, liberty, or property.

Further, a pretrial hearing will likely be required for the trial court to assess “the degree of accuracy with which the AI system [correctly] measures what it purports to measure” or “otherwise demonstrates its validity and reliability.”14 One obstacle that may be encountered is “explainability.” That is how one commentator explains how the AI model generated its output.

[M]ore sophisticated AI methods called deep neural networks [are] composed of computational nodes. The nodes are arranged in layers, with one or more layers sandwiched between the input and the output. Training these networks—a process called deep learning—involves iteratively adjusting the weights, or the strength of the connections between the nodes, until the network produces an acceptably accurate output for a given input.

This also makes deep networks opaque. For example, whatever ChatGPT has learned is encoded in hundreds of billions of internal weights, and it’s impossible to make sense of the AI’s decisionmaking by simply examining those weights.15

Simply put, this is the so-called “black box” phenomenon.

The selection of training data, as well as other training decisions, is [initially] human controlled. However, as AI becomes more sophisticated, the computer itself becomes capable of processing

and evaluating data beyond programmed algorithms through contextualized inference, creating a “black box” effect where programmers may not have visibility into the rationale of AI output or the data components that contributed to that output.16

The above statement is not without controversy. Some argue that AI platforms cannot go beyond their programmed algorithms. Even AI tools that have been programmed to modify themselves can only do so within the original parameters programmers develop. “Deep Learning” tools may differ from AI tools that are considered “Machine Learning.” Nevertheless, “Federal Rule of Evidence 702 requires that the introduction of evidence dealing with scientific, technical, or specialized knowledge that is beyond the understanding of lay jurors be based on sufficient facts or data and reliable methodology that has been applied reliably to the facts of the particular case.”17 “Neural networks develop their behavior in extremely complicated ways—even their creators struggle to understand their actions. Lack of interpretability makes it extremely difficult to troubleshoot errors and fix mistakes in deep-learning algorithms.”18

The AI developers may be unable to explain fully what the platform did after the algorithm was first created, but they may be able to explain how they verified the final output for accuracy. AI models may also be dynamic if they are updated with new training data, so even if a specific model can be tested and validated at one point in time, later versions of the model and its results may be significantly different.

An immediate evidentiary concern emerges from “deepfakes.” Using certain AI platforms, one can alter existing audio or video. Generally, the media is altered to give the appearance that an individual said or did something they did not.19 The technology has been improving rapidly.

What is more, even in cases that do not involve fake videos, the very existence of deepfakes will complicate the task of authenticating real evidence. The opponent of an authentic video may allege that it is a deepfake in order to try to exclude it from evidence or at least sow doubt in the jury’s minds. Eventually, courts may see a “reverse CSI effect” among jurors. In the age of deepfakes, jurors may start expecting the proponent of a video to use sophisticated technology to prove to their satisfaction that the video is not fake. More broadly, if juries—entrusted with the crucial role of finders of fact—start to doubt that it is possible to know what is real, their skepticism could undermine the justice system as a whole.20

Although technology is now being created to detect deepfakes (with varying degrees of accuracy),21 and government regulation and consumer warnings may help,22 no doubt if evidence is challenged as a deepfake, significant costs will be expended in proving or disproving the authenticity of the exhibit through expert testimony.23

The proposed changes to Fed. R. Evid. 702, which [became] effective on December 1, 2023, make clear that highly technical evidence, such as that involving GenAI and deepfakes, create an enhanced need for trial judges to fulfill their obligation to serve as gatekeepers under Fed. R. Evid. 104(a), to ensure that only sufficiently authentic, valid, reliable—and not unfairly or excessively prejudicial—technical evidence is admitted.24

Concerned that AI tools may produce accurate results, but not necessarily reliable results, two very distinguished scholars have called for Fed. R. Evid. 901(b)(9) to be amended to require a proponent of AI-generated evidence to describe any software or program that was used and show that it produced reliable results “in this instance.”25 It remains uncertain whether that proposal will be adopted. It is also uncertain how reliability may be satisfied given the proprietary information concerns discussed above, and how much additional cost will be added to the already overly costly litigation system in attempting to establish or refute the proposed reliability standard.

If not already implemented by law enforcement agencies, the probability that AI platforms will be used to track, assess,

and predict criminal behavior is probable.26 By collecting data on movements, occurrences, time of incidents, and locations, AI tools can flag aberrations to law enforcement officials. Such analyses can allow law enforcement agencies to predict crimes, predict offenders, and predict victims of crimes.27 Criminal defense attorneys encountering situations where their clients have been arrested because of AI tools will need to evaluate whether any due process or Fourth Amendment violations can be asserted in this context.

Some benefits and risks associated with AI-adoption in the criminal justice system are apparent. Early adopters, for instance, are using AIpowered document processing systems to improve case management. A new system in Los Angeles recently helped a public defender help a client avoid arrest after the attorney was alerted by the system to a probation violation and warrant.28 Lawyers involved in the California Innocence Project are using Casetext’s CoCounsel, an AI tool, to identify inconsistencies in witness testimony.29

Already tools have been produced that assist courts with bail evaluation and sentencing decisions. However, past platforms of these types have been the subject of some immense scrutiny as being unreliable and biased.30 Racial bias has seeped into some earlier programs because of inputs such as home residence being used in the algorithms.31 Given the presence of racially segregated neighborhoods, these algorithms produced bail recommendations that were unintentionally biased. The effect of implementing AI in place of human decision-making was recently studied by a credited group of researchers. The surprising results showed that bail decision models trained using common data-collection techniques “judge” rule violations more harshly than humans would. “[I]f

Our specialization allows us to offer legal professionals better coverage at rates substantially lower rates than most competitors. Call (866) 977-6720 or email sam@attorneysfirst.com for a fast & friendly quote. Our Promise to you! We won’t waste your time preparing a quote if we can’t SAVE you significantly.

a descriptive model is used to make decisions about whether an individual is likely to reoffend, the researchers’ findings suggest it may cast stricter judgements than a human would, which could lead to higher bail amounts or longer criminal sentences.”32 Another study found that participants who were not inherently biased, were still strongly influenced by advice from biased models when that advice was given prescriptively (i.e., “you should do X”) versus when the advice was framed in a descriptive manner (i.e., without recommending a specific action).33

Courts and probation offices that are considering adopting these platforms should inquire into how the platform was built, what factors are being considered in producing the result, and how bias has been mitigated.34 Further, if such platforms are used in the bail consideration or sentencing process, they should be used only as a non-binding recommendation given the complexity and impact of such decisions.

Some AI platforms contend that the use of their products could accelerate the hiring process and reduce the potential for discrimination allegations.35 Law firms or clients seeking to use these AI platforms should understand that such platforms should be vetted for bias and accuracy. Attorneys counseling employers also need to be aware of the limitations of any such platforms. Efforts should be made to ensure that “explainability” of the platform’s results can be produced. As with all tools that are used to monitor or measure employee actions and performance, privacy, and discrimination concerns should be considered.36 If law firms or clients use third parties to handle their human resource needs, a review of what, if any, AI platforms are used and how should be made. In addition, lawyers working in this area should monitor developments in this field, such as guidance being developed by the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission37 and the National Labor Relations Board.38

A recent example is a New York City law requiring transparency and algorithmic audits for bias. New York City Local Law 144 of 2021 regarding automated employment decision tools (AEDT) prohibits employers and employment agencies from using an AEDT tool unless the tool has undergone a bias audit within one year of the use of the tool, information about the bias audit is publicly available, and certain notices have been provided to employees or job candidates.39

How generative AI and LLMs (large language models) will be incorporated into eDiscovery remains uncertain. Discovery is generally conducted by implementing a legal hold when the duty to preserve evidence has been triggered. Later, key players and other data custodians are interviewed to determine what, if any, relevant evidence the custodian or source (e.g., email server) may possess. Then relevant data is gathered and usually sent to a vendor for processing and uploading onto a platform where the documents can be reviewed and tagged for relevance, privilege, or both. Usually, parties agree to search terms to ensure that relevant documents are procured and produced. In larger cases, parties may opt to use technology-assisted review (TAR) platforms where a “seed set” is reviewed by a person knowledgeable on the file and then the TAR platform “learns” from the “seed set” and automatically reviews the remaining documents for relevance and privilege without human input. The natural language search capabilities of LLMs are now being incorporated into eDiscovery platforms.40 This allows AI to recognize patterns and identify relevant documents. Unstructured data (e.g., social media and collaborative platforms like Slack or Teams) can be reviewed by the AI tool. Theoretically, collection and review costs could

be dramatically lessened, and attorney fees reduced. Another possibility is that AI will be used to augment the document gathering and review process, as well as assist with privilege review. For example, the Clearbrief platform, amongst others, is already being used for this purpose, with the underlying source documents visible in Word so the user can verify the relevance of the results of the AI suggestions of relevant documents. The user can then share a hyperlinked version of their analysis with the cited sources visible so the recipient can also verify the relevance of the source document.

A potential downside to the adoption of AI tools that must be considered is whether any prompts entered in the AI tool, or data or images generated by the AI tool may be subject to production in the event of a government investigation or litigation request. Just as collaboration tools such as Slack and Teams have added to new burdens and costs to production compliance, so too may AI tools.

It is widely expected that AI tools will be more routinely deployed in the diagnosis of diseases and treatment. Lawyers practicing in the healthcare industry will need to consider issues of bias in the AI tool’s seed set that may lead to accuracy problems.41 They will also need to understand how these tools can be employed in a way that complies with healthcare-specific regulatory requirements— in particular, privacy requirements imposed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). As with other issues raised above, liability for any misdiagnosis or treatment resulting from the use of an AI tool will require future judicial resolution.

AI tools have already been implemented by immigration law practitioners in completing U.S. citizenship forms and tracking their status.42 AI tools have been helpful in this area, where often the same data must be filled in multiple forms. Again, as with all forms that are generated, it is still the responsibility of the attorney to review for accuracy any forms completed by an AI tool.

AI tools, in their current, nascent form, present intriguing possibilities, but also serious logistical and ethical risks that attorneys must thoughtfully assess before incorporating these tools into their practice. The savvy practioner will stay abreast of the development of

more accurate and more specialized tools to continuously balance the benefits and risks of this evolving technology.

The final installment of this series will to explore more specific concerns about the use of AI in the legal profession and additional contexts in which it may be relevant.

See Endnotes on pages 27–28.

Judge Xavier Rodriguez was appointed to the United States District Court, Western District of Texas in 2003. He is the editor of Essentials of E-Discovery (TexasBarBooks 2d ed. 2021), as well as a member of The Sedona Conference Judicial Advisory Board, the Georgetown Advanced E-Discovery Institute Advisory Board, and the EDRM Global Advisory Council. He also serves as the Distinguished Visiting Jurist-in-Residence and adjunct professor of law at the St. Mary’s University School of Law.

By Justice Lori I. Valenzuela and Austin Reyna

Texas appellate courts have the duty and honor of reviewing family law decisions ranging from the parentchild relationship and the parental presumption to the classification of property in divorce proceedings. The importance of advocates continuing to be apprised of recent family law jurisprudence cannot be overstated. While we are unable to address every recent change and trend in this article, below are a few cases you may find applicable in your practice—or at least of general interest.

In re J.N.M., 672 S.W.3d 474 (Tex. App.— San Antonio 2023, pet. denied)

Mother and Stepfather began cohabitating when Mother was pregnant with a child from a previous relationship.1 Although he was not the child’s biological father, Stepfather treated the child as his own. Mother filed a Suit Affecting the Parent-Child Relationship (“SAPCR”) to prevent the child’s biological father from possession and access.2 Mother subsequently asked Stepfather to watch the child after she was admitted to the hospital.3 Mother died shortly thereafter due to COVID complications.4 Stepfather intervened in the previous SAPCR to be appointed the child’s sole managing conservator.5 The child’s maternal grandparents also intervened and filed a plea to the jurisdiction, arguing Stepfather did not have standing to intervene in the original SAPCR, and the trial court granted the plea.6 We reversed, holding Stepfather had maintained actual care, custody, and control of the child for the requisite statutory period to obtain standing.7 Because Stepfather was entitled to, but could not, participate in the merits, we determined his exclusion resulted in a due process violation and remanded for further proceedings in which Stepfather could participate.

In re Barrett, No. 04-23-00928-CV, 2023

WL 8793150 (Tex. App.—San Antonio Dec. 20, 2023, orig. proceeding)(mem. op.)

In this original proceeding arising out of a modification suit, Father argued the trial court erred by failing to enter judgment on the parties’ mediated settlement agreement (“MSA”).8 Mother asserted the trial court was not obligated to enter judgment because Father had either breached the MSA or had committed family violence against a party to the MSA—one of the parties’ children.9 We reversed the trial court, holding the MSA met all statutory requirements to be binding, and the exceptions to rendering judgment on an MSA did not apply.10

In re Muldoon, 679 S.W.3d 182 (Tex. App.— San Antonio 2023, orig. proceeding)

The issue in this original proceeding was whether the Uniform Child Custody Jurisdiction and Enforcement Act (“UCCJEA”) required the trial court to provide the parties with an opportunity to be heard before determining jurisdiction.11 In the underlying case, the Texas trial court held a conference with the Virginia trial court and made a jurisdictional determination without providing the parties an opportunity to present factual and legal arguments.12 Finding this to be a misapplication of the law, we conditionally granted mandamus relief.13

DeSpain v. DeSpain, 672 S.W.3d 486 (Tex. App.—San Antonio 2023, no pet.)

Husband’s Mother lived with Husband and Wife.14 Wife helped care for Mother “by taking her to doctor appointments, providing companionship, preparing meals, and providing other household assistance.”15 During their marriage, Husband and Mother were signatories on a bank account—funded only by Mother—that was used to buy land, build a house, and make other improvements that Husband, Wife, and Mother enjoyed.16 After Mother’s death, Husband and Wife

began divorce proceedings.17 The trial court found the funds used for the land and improvements were either a gift to Husband and Wife or a gift given one-half to each and not a part of the community estate.18 We affirmed, holding that the evidence did not support a presumption that Mother gifted the purchase funds solely to Husband.19 We held that Mother making Husband a signatory on the bank account was insufficient alone to prove donative intent.20 The trial court correctly determined that the land was properly characterized as a 50% undivided, separate property interest owned by Husband and a 50% undivided, separate property interest owned by Wife.21

In re J.N., 670 S.W.3d 614 (Tex. 2023). In this divorce proceeding, Mother withdrew her jury demand for the purpose of invoking the trial court’s statutory obligation to interview her thirteen-year-old daughter regarding the child’s preference for primary residency.22 The trial court denied Mother’s request because she did not file a written motion and proceeded to conduct a bench trial because Mother had withdrawn her jury demand.23 The Dallas Court of Appeals affirmed.24 The Supreme Court of Texas reversed in part, holding: (1) the trial court had a statutory obligation to conduct an interview with a child when properly invoked; (2) a written motion is not required by the statute; (3) such error was subject to harm analysis; and (4) the trial court’s error was harmful because it resulted in the Mother’s loss of a jury trial.25

Gardner v. McKenney, No. 03-21-00130CV, 2023 WL 1998902 (Tex. App.—Austin Feb. 15, 2023, no pet.)(mem. op.). When the children were in Mother’s possession, Father rented out their rooms on Airbnb. In this direct appeal from an order modifying the parent-child relationship, Fa-

ther asserted the trial court erred by enjoining him from renting out the children’s rooms during periods of Father’s non-possession.26 On appeal, the Third Court of Appeals held the trial court acted within its discretion and affirmed. The court reasoned that because there were no findings of fact or conclusions of law, it must defer to the trial court for demeanor and credibility determinations.27

Chintam v. Chintam, No. 05-22-00022-CV, 2023 WL 5345829 (Tex. App.—Dallas Aug. 21, 2023, no pet.)(mem. op.). Wife and Husband divided their community assets pursuant to an MSA that was finalized into a divorce decree.28 Subsequently, Wife initiated suit against Husband to divide property she alleged he did not disclose during the parties’ mediation.29 Affirming the trial court’s order on other grounds, the Fifth Court of Appeals held the trial court erred in allowing Husband’s counsel to testify regarding what transpired during the confidential mediation process. However, the court also held documents shared during mediation could be considered by the trial court if the documents were admissible independently of the mediation process.30

Justice Lori I. Valenzuela has been on the Fourth Court of Appeals since 2021. From 2009 to 2021, she presided over the 437th District Court. Prior to her tenure on the bench, Justice Valenzuela served as a Bexar County Assistant District Attorney, established a law practice concentrating on criminal defense, and worked as a county magistrate. Justice Valenzuela is an adjunct professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Justice Valenzuela received her Bachelor of Arts in Government from the University of Texas at Austin and her Juris Doctor degree from St. Mary’s University School of Law.

Austin Reyna has been a staff attorney at the Fourth Court of Appeals since March 2022. Prior to the Fourth Court of Appeals, Austin practiced complex civil litigation.

1In re J.N.M., 672 S.W.3d at 476.

2Id.

3Id.

4Id.

5Id.

6Id. at 476–78.

7Id. at 479–81; Tex. Fam. Code § 102.003(a)(9).

8In re Barrett, 2023 WL 8793150, at *1.

9Id. at *1–3.

10Id. at *4–7.

11In re Muldoon, 679 S.W.3d at 184.

12Id. at 186–87.

13Id.; Tex. Fam. Code § 152.110(c), (e), (f).

14DeSpain, 672 S.W.3d at 489.

15Id.

16Id. at 490.

17Id. at 490–92.

18Id.

19Id. at 494.

20Id. at 493–97.

21Id.

22In re J.N., 670 S.W.3d 614, 616 (Tex. 2023); Tex. Fam. Code § 153.009.

23In re J.N., 670 S.W.3d at 617.

24In re J.N., 663 S.W.3d 240 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2022), rev’d in part, 670 S.W.3d 614 (Tex. 2023).

25In re J.N., 670 S.W.3d 614 (Tex. 2023).

26Gardner, 2023 WL 1998902, at *1.

27Id. at *3.

28Chintam, 2023 WL 5345829, at *1.

29Id.

30Id. at *4–6; Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 154.073(c).

By Soledad Valenciano, Melanie Fry, and Jeffrie Lewis

If you are aware of a Western District of Texas order that you believe would be of interest to the local bar and should be summarized in this column, please contact Soledad Valenciano (svalenciano@svtxlaw.com, 210–787–4654) or Melanie Fry (mfry@dykema.com, 210–554–5500) with the style and cause number of the case, and the entry date and docket number of the order.

Remand; snap-removal

Cheyanne Adams, et al v. Zachry Industrial, Inc., No. SA-23-CV-01437-XR (Rodriguez, X., Jan. 16, 2024)

The plaintiffs (Louisiana residents) sued the defendant (a Texas corporation) in state court in Bexar County. Prior to being properly joined and served, the defendant “snap removed” the matter to federal court on diversity grounds. The plaintiff filed a motion to remand, arguing the defendant had improperly removed the case and the removal was contrary to the forum-defendant rule of 28 U.S.C. § 1441(b)(2). The plaintiffs contended that allowing a forum defendant to remove a state court case in this posture is improper; “would violate the purpose and congressional intent underpinning the forum defendant rule”; and would yield “an absurd result.” The court disagreed. The Fifth Circuit in Tex. Brine Co., L.L.C. v. Am. Arb. Ass’n, Inc., 955 F.3d 482, 487 (5th Cir. 2020), explained that the forum-defendant rule was a procedural rule, not a jurisdictional one. The court concluded that the plain language of § 1441(b)(2) permits snap removal by a forum defendant prior to service of the state petition and while there are district court decisions limiting snap remove to non-forum defendants, the great weight of authority holds that the reasoning of the Fifth Circuit in Tex. Brine Co., L.L.C. permits snap removal by forum defendants. The court denied the motion to remand.

Castilleja v. United of Omaha Life Ins. Co., No. SA-23-CV-01308-XR (Rodriguez, X, March 7, 2024)

The plaintiff, while her son was hospitalized, contacted the defendant, an insurance agent, to secure a life insurance policy for her son. The plaintiff alleged that the defendant filled out

the life insurance application and signed the application on behalf of the plaintiff’s son. When the plaintiff’s son passed away a few years later, the plaintiff filed a claim under her son’s policy, which the insurance company denied. The plaintiff sued the agent and insurance company in state court, and the insurance company removed the action based on diversity jurisdiction despite a lack of complete diversity, alleging the plaintiff improperly joined the agent to avoid removal. To establish improper joinder, a removing party must show an “inability of the plaintiff to establish a cause of action against the non-diverse party in state court.” The court conducted a Rule 12(b)(6) analysis, concluding that allegations that the agent forged the policy application signature did not allege a misrepresentation to the plaintiff; rather, it demonstrated a misrepresentation toward the insurance company. The court also noted that the petition failed to specify which section(s) of the Texas Insurance Code were at play, and thus the petition offers no reasonable basis for the court to predict that the plaintiff might recover against the agent/non-diverse defendant. The court thereafter dismissed the plaintiff’s claims against the agent without prejudice.

Thomison v. Meridian Sec. Ins. Co., No. SA-23CV-00411-JKP (Pulliam, J., April 9, 2024)

The plaintiff insureds sued the defendant insurer over a coverage dispute arising under a homeowner’s policy effective between July 27, 2020, and July 27, 2021. The policy included coverage for hail, but excluded cosmetic-only damage caused by hail. In May of 2021, the plaintiffs began experiencing a water leak through the ceiling after an alleged hail storm. One year after the plaintiffs unsuccessfully attempted to repair the leak themselves, the plaintiffs reported a claim with the defendant

insurer for the persisting leak, with a date of loss occurring within the 2020-2021 policy, despite reporting the loss during the 2021-2022 policy period. The defendant investigated and covered some of the damage, but the plaintiffs disagreed with the defendant’s coverage decision, and brought claims for breach of contract, Texas Insurance Code and Deceptive Trade Practices Act (DTPA) violations, and bad faith. The defendant filed a motion for summary judgment on all causes of action. The court denied summary judgment on the breach of contract claim because, in its motion, the defendant argued that the plaintiffs were unable to distinguish damages occurring within the 2021-2022 policy period from those occurring outside of the policy period in question. However, the plaintiffs clarified that they were not claiming damages under the 20212022 policy period as the defendant argued, but rather they brought their claims under the 20202021 policy. With regard to the bad faith claim, the court found that the plaintiffs’ undisputed one-year delay in reporting their claim “impliedly created…a reasonable need to inspect and determine the cause and timing of any alleged property damage.” Further, it was undisputed that, once notified, the defendant adjusted the claim within 3.5 months. Therefore, the court concluded that defendant promptly investigated the claim and had a reasonable basis for delaying payment, and granted summary judgment in favor of the defendant on the plaintiffs’ bad faith claim. The court also granted summary judgment in favor of the defendant on the plaintiffs’ Texas Insurance Code and DTPA claims, noting that they share the same predicate as a bad faith claim. Thus, because the plaintiffs’ bad faith claims failed, so too did their claims arising under the DTPA and the Texas Insurance Code, as a matter of law. Finally, despite moving for summary judgment on all causes of action asserted by the plaintiffs, the defendant failed to argue in support of summary judgment on the plaintiffs’

claim for violation of the Texas Prompt Payment Act. Therefore, summary judgment was denied on this cause of action.

Guilbeau v. Schlumberger Tech. Corp., No. SA-21-CV-0142-JKP-ESC (Pulliam, J., April 16, 2024)

Following an order accepting the recommendation of the magistrate judge to grant summary judgment in favor of the plaintiff, the defendant filed a Motion to Certify an Interlocutory Appeal. The court stayed and administratively closed the action pending the resolution of defendant’s motion. Under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b), the court must find (1) a controlling question of law is involved, (2) there is substantial ground for difference of opinion about the question of law, and (3) that immediate appeal will materially advance the ultimate termination of the litigation. The court held that the defendant failed to demonstrate the statutory requirements warrant certification, holding that the order sought to be certified does not concern a simple or pure question of law, but rather was a denial of summary judgment because the defendant had not carried its burden to show the plaintiffs were exempt as a matter of law. The court further noted each district in Texas has recognized that judges have unfettered discretion to deny certification, even when the statutory criteria are present. Under these circumstances, the court held it would still decline to exercise its discretion to certify the prior order for interlocutory appeal because many of the arguments asserted in the motion for certification simply questioned the court’s summary judgment rulings. The court further noted that the defendant had previously failed at two attempts to convince the court of the merits of its position in its summary judgment motion, which was ruled on by the magistrate judge and for which the district court reviewed the defendant’s objections de novo

Foreclosure; Wrongful Foreclosure; Breach of Contract

Alvarado v. PennyMac Loan Servs., LLC, No. SA-24-CV-00150-XR (Rodriguez, X., April 18, 2024)

The plaintiff homeowner sued the defendant mortgage servicer in state court to prevent foreclosure of his home after defaulting on his mortgage loan, alleging breach of contract, wrongful attempt to foreclose, and injunctive and declaratory relief. The state court granted an ex parte

temporary injunction preventing the foreclosure sale. The defendant timely removed to federal court and moved for summary judgment on all claims. Although the plaintiff failed to respond, the court evaluated the case on the merits, citing John v. State of La. (Bd. of Trs. for State Colls. &Univs.), 757 F.2d 698, 709 (5th Cir. 1985). The court noted that to assert a claim for breach of contract in a wrongful foreclosure case, the

claimant must specify which contract provision was breached. See Innova Hosp. San Antonio, L.P. v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Ga., Inc., 995 F. Supp. 2d 587, 602 (N.D. Tex. Feb. 3, 2014). Here, the plaintiff did not cite to a specific contract provision, but rather cited to improper notice, generally. The defendant argued that the plaintiff’s claim for breach of contract failed because the plaintiff, himself, was in breach of the

contract. The court rejected this argument, citing to an exception to this general rule recognized by the Fifth Circuit, which applies to terms governing a lender’s notice obligations in the context of a default on a deed of trust. The court explained that an interpretation to the contrary would render notice requirements meaningless, given that notice requirements only apply in the event of a breach. The plaintiff claimed that he did not receive notice from the defendant, which the court rejected because the defendant had proof that it sent appropriate notice, noting that notice requirements do not require that the borrower actually receive the notice. See Martins v. BAC Home Loans Servicing, 722 F.3d 249, 256 (5th Cir. 2013). The court went on to explain that even if the defendant failed to meet the notice requirements, the defendant did not foreclose on the plaintiff’s home, and Texas does not recognize a cause of action for attempted wrongful foreclosure. Finally, the court denied injunctive and declaratory relief due to no underlying cause of action. Therefore, the court granted summary judgment in favor of the defendant, and dismissed the plaintiff’s claims with prejudice.

Alamo Intermediate II Holdings, LLC v. Birmingham Alamo Movies, LLC, No. SA-23CV-01531-JKP (Pulliam, J, April 25, 2024).

The defendant moved to dismiss the action due to lack of personal jurisdiction. The court examined whether the defendant, a non-signatory individual, was bound by the terms of a franchise agreement containing a forum selection clause and a waiver of jurisdictional challenge. The defendant argued he is not a “party” to the franchise agreement, and he did not sign the franchise agreement in an individual capacity. The court examined Texas contract law, which holds that a defendant shall be interpreted as a “party” if he otherwise indicated his consent to be bound, which the defendant here did in paragraph 6.3 of the franchise agreement, among other others. The court held that even if cited excerpts are insufficient, the defendant would still be bound by the forum selection clause in the franchise agreement under the “closely related” doctrine. This doctrine provides that a non-signatory can be bound to a forum selection clause if the non-signatory is so closely related to the dispute such that it becomes foreseeable that the non-signatory would be bound. A “closely related signatory,” or one who is “allegedly engaged in the conduct ‘closely related to the contractual relationship,’” will be bound by the internal forum selection clause. A non-signatory who is “inextri-

Digital Forensics/Cell Tower Geolocation Mapping Cell Phone Records Analysis for MVAs

Licensed Texas Private Investigator (A15633) Retired Federal Agent (AFOSI)

Court Certified Expert Witness (Federal/State/Military) (210) 271-2999

Titan Building 2700 NE Loop 410, Ste. 301, San Antonio, TX 78217 www.WhatsOnThePhone.com