H amiinat

THE MAGAZINE OF THE SAN MANUEL BAND OF MISSION INDIANS

I am delighted to share the Winter 2025 issue of Hamiinat, the magazine of the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians. The magazine title translates to “hello” in the Maara’yam (Serrano Indian) language. This is also an extension of friendship, goodwill and Serrano hospitality, for which our people are well known.

Serrano Indians are indigenous to the San Bernardino Mountains and valleys, as well as the High Desert regions of Southern California. The people of San Manuel are the Yuhaaviatam Clan of Serrano Indians, whose rich culture and history are reflected throughout this wonderful magazine. We are most happy to offer you a glimpse into our Tribe and enterprises.

Our cover story is about the cultural and spiritual significance of the piñon harvest, a tradition the Serrano people have maintained for centuries. The trees, part of our creation story, sustained our people through displacement and challenging times. Now they sustain the Tribe’s connection to one another and their heritage.

We reflect on the events of the annual San Manuel Pow Wow and learn firsthand why the three-day gathering of people from the United States and Canada means so much to all who attend. And we see how events held on California Native American Day, as well as the week leading up to it, help people discover the beauty and truth about Indigenous cultures in the state.

We follow unfolding developments in the attempt to heal the damage done to generations of Native people by federal Indian boarding schools and track the efforts to eliminate human trafficking.

We meet new members of the San Manuel Youth Committee and learn their vision for giving back to their Tribe by serving in leadership roles; five Indigenous leaders who have been honored by the California Native American Legislative Caucus; and three generations of tribal leadership who share their hopes for the future.

We learn what the Tribe values by the causes it supports through philanthropy and see why sharing the Tribe’s history and culture can uplift all those involved with its ventures. We get insight into why the tribal court is so critical to tribal governments and how San Manuel is preparing the next generation of attorneys to be allies in tribal matters.

We look at the fun way San Manuel shows appreciation for its team members and get the play-by-play on an epic college football season from the team’s MVPs who shared the story with sports lovers at Yaamava’ Resort & Casino at San Manuel. Finally, we’ll focus on Native designers and look at how a few chefs are making their gorgeous desserts too hard to resist. We thank you for being our guest and can’t wait to share our many new and exciting offerings, as well as our Yuhaaviatam tribal culture, with you.

Chairwoman Lynn “Nay” Valbuena San Manuel Band of Mission Indians

BEST LAS VEGAS CASINO

GRAND LOFT SUITE

OLIVIA STEELE ART

THE LATEST SLOTS

CONTENTS

PÜMIA’ CAKIMIV

6 / COVER

This centuries-old tradition forges a spiritual connection to the Creator and one another.

12 / CULTURE

The San Manuel Pow Wow offers a glimpse into Indigenous strength and community.

16 / HERITAGE

Students learn about California’s First Peoples through an immersive educational experience.

18 / TRIBAL HIGHLIGHTS

Meet three generations of leadership who are working to secure the future of the Tribe.

20 / NEXT GENERAT ION

San Manuel youth are prepared for future tribal leadership.

22 / FIRESIDE C HATS

Create a culture of caring by sharing the Tribe’s journey of resilience and its vision for the future.

24 / G OVER NA NCE

Understanding the role and importance of tribal courts in providing fair and accessible justice.

28 / RECOGNIT ION

Celebrating Native forces for positive change.

PUYU’HOUPKCAV

30 / AWARE NESS

A trafficking victim shares her story– and how we can fight back against the pervasive crime.

36 / TEACHING TRADITI ONS

A celebration to understand the unique cultures of California’s First Peoples.

38 / HERITAGE

The impact of the federal Indian boarding schools on Native American communities continues to ripple out.

42 / PHILANTHR OPY

Honoring San Manuel’s long-term vision for community support and generational responsibility.

44 / FAMILY

San Manuel says thank you to each team member for their hard work with an annual celebration – filled with food, music and rides.

46 / GIVING BACK

The annual San Manuel Golf Tournament creates a profound impact on eight charities.

50 / EDUCATI ON

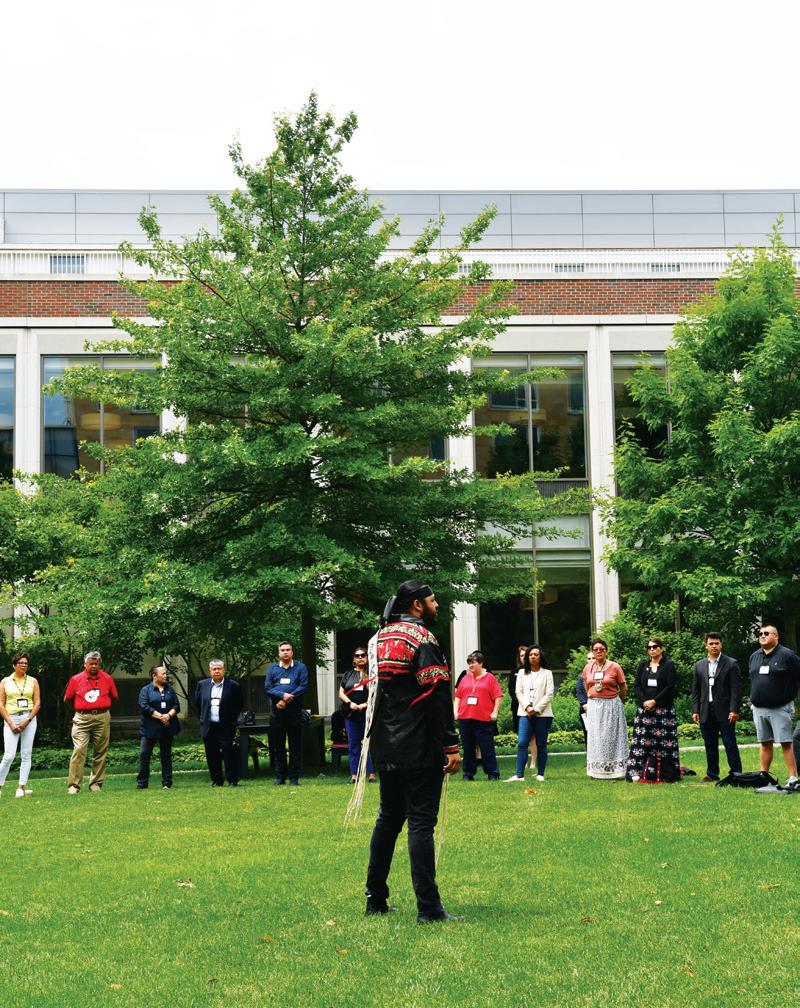

A week at Harvard empowers Native people to reclaim voices in media and government and increase economic standing.

52 / EXPERIE NCE

A unique summer experience at San Manuel prepares students for careers in tribal law.

54 / COLLABORATION

See how business owners spread love and connection to their community, and what their connection with Yaamava’ will bring.

59 / SUPP ORT

Connecting survivors of domestic violence to community resources.

60 / ACCO MP LI S HMENT

A San Manuel team member shares her achievements while working for the Tribe.

M Ü CI S CK

62 / STYLE

Indigenous motifs and sustainability in winter’s style.

70 / ON TRE ND

Bold contrast takes the look to the next level – all available at Yaamava’ Resort & Casino at San Manuel.

74 / SAVOR

Classic desserts are transformed with whimsical additions.

80 / SP OTLIGHT

One night with USC football stars Leinart and Bush.

84 / P ROFILE

One chef’s journey to bringing happiness through pastry.

H amiinat

TRIBAL COUNCIL

CHAIRWOMAN Lynn Valbuena

VICE CHAIRMAN Johnny Hernandez, Jr.

SECRETARY Audrey Martinez

TREASURER Latisha Prieto

CULTURE SEAT MEMBER Joseph Maarango

FIRST GOVERNING COUNCIL MEMBER Ed Duro

SECOND GOVERNING COUNCIL MEMBER Laurena Bolden

CONTRIBUTORS

Gina Alvarado

Yvette Ayala Henderson

Jacob Coin

Erin Copeland

Shoshawna Covington

LeeAna Espinoza Salas

Timothy Evans

Christopher Fava

Sonna Gonzales

Darcy Gray

Kristen Grimes

Anna Hohag

Alberto Jasso

Angelica Loera

Chelsea Marek

Laurie Marsden

Amanda Martin

Summer Massoud

Tiffany Melendez

Shawnna Nason

Marcus O’brien

Anthony Olivas

Stacia Olivas

Noel Olson

Tammy Purdy

Tina Ramos

Steven Robles

Cheyenne Sanders

Ken Shoji

Corey Silva

Gregory Vanstone

Oliver Wolf

A VERY SPECIAL THANK YOU TO THE FOLLOWING:

Raven Casas

Quoymee Chacon

Nicole Fields

Annabella Hernandez

Audrey Hernandez

Nekoli Hernandez

Roman Hernandez

Judiciary Board

Riley Murillo

Latisha Prieto

James Ramos

Tom Ramos, Sr.

Carla Rodriguez

Halani Zavala

Thank you to the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians and the entire tribal community for sharing their stories: past, present and future.

EDITORIAL

MANAGING EDITOR Laurena Bolden

MANAGING EDITOR Joseph Maarango

MANAGING EDITOR Jessica Stops

PRODUCTION MANAGER Julie Lopez

PUBLISHER Peter Gotfredson

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Lisa Thé

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Jessica Villano

PÜ MIA ’ C ˇ AKIMIV

(puh-mee-ah chah-kee-meev)

Our Heritage

Pümia' C�akimiv: What we came with. The phrase describes our heritage, traditions, culture and all the songs and dances our people have passed down over many generations

In this section we explore the cultural significance of the piñon harvest for the Serrano people. We reflect on the connections that were strengthened and traditions that were shared at the San Manuel Pow Wow. We meet tribal youth who have recently joined the Youth Committee and see what it is they hope to learn from the experience. We also learn about tribal citizens who are committed to leadership roles, others who seek to deliver equality and balance for the good of the community and how one tribal citizen shares the history of her people to create a familial culture within the company. Finally, we look at a newly formed caucus that bestowed recognition upon Native people who create positive change.

Photography by Tiffany Melendez

Nourishing

Body & Soul

Exploring the cultural and spiritual significance of the piñon.

BY RICHARD ARLIN WALKER / PHOTOGRAPHY BY

TIFFANY MELENDEZ

WHEN THE LANDS of the Yuhaaviatam were being encroached upon by settlers, when newcomers took more than their share of the deer and plants that had fed the people since creation, the Yuhaaviatam still had the trees.

The piñon pines and the Yuhaaviatam had adapted to the extremes of life: the trees, the extremes of weather, the people, the extremes of human behavior. And so, as Europeans and Americans arrived in the area –covetous of Yuhaaviatam land, resources and game – the people found sustenance in the piñon pines.

“High in the San Bernardino Mountains at Yuhaaviat, an area of pine trees near present-day Big Bear Lake, Küktac our Creator lay dying,” the story is told. “When Küktac died, the people began to mourn.”

In their grief, the mourners became pine trees, and those trees gave life to the Yuhaaviatam people and “enriched the land with vegetation and animals, allowing future generations to thrive.” Those ancestors helped ensure their descendants’ survival, providing nutrient-rich piñon nuts.

Nicole Fields, 20, is a citizen of San Manuel. She has participated in the harvest since she was a child.

“I think it’s pretty amazing how one could survive off of piñon nuts,” she said. “I’m sure the ancestors caught

rabbits and other animals, but when the animals were scarce, piñon nuts were a good form of protein.”

The Yuhaaviatam people survived. Their kiika, Santos Manuel – Fields’s ancestor – led them in the 1860s to the valley floor where, in 1891, the San Manuel Reservation was established.

The piñon pines at Yuhaaviat continue to contribute to the Yuhaaviatam people’s physical and spiritual well-being and represent a long-standing connection to the land. The piñon harvest is steeped in traditional knowledge, gratitude and love.

Fields said families watch the groves to see which are producing enough for harvesting. “There’s one window of opportunity – when the pinecones open up or when they’re at their peak size right before they open,” Fields said.

James Ramos, past Chairman and continued Cultural Awareness Coordinator, has been leading the Yuhaaviatam camp since 2005. As the piñon bloom mid-August to mid-September, Yuhaaviatam set up camp at the harvest site. This year there were about 25-30 tribal citizens.

“The night before, we thank our ancestors for passing down their knowledge and survival to us,” Fields said. “I reflect on that when I’m picking. I think

“THEY COLLECTED PIÑON AS A SOURCE OF SURVIVAL, AS A WAY OF LIFE.”

about how my parents taught me to gather when I was young, and I think of how their parents taught them and how I could teach younger generations.”

On the day of the harvest, Bird Singers sing songs and a blessing is given, “to thank the land for what it’s providing us and for bringing our family together,” explained Fields.

Then, the harvest begins.

“The biggest thing I have learned is how to use the fruit picker correctly – how to twist the cone and pull it the right way instead of pulling down and launching it off into the distance,” Fields said.

Cones are steamed in big pans over a fire until they soften and can be pulled apart to get the piñon nuts, or seeds, out. Then seeds are roasted for about 20 minutes. The nuts can be added to salad, pasta or seafood dishes or eaten alone. “We snack on them as is or I mix them into trail mix,” Fields said.

The piñon harvest is, like other cultural gatherings, an important time for families to enjoy each other’s company and pass down teachings.

“After we say the blessing and the prayer, we break off and find the tree we want to harvest at and then, as we’re harvesting, we talk,” Fields said. “Same thing with roasting and processing: you have a group of

people standing by the fire checking to see if the piñon nuts are soft. And you have people picking the nuts from the cones.”

Knowledge passed down since the time of the grandparents’ grandparents is shared here during the harvest. Those who know the language, like Fields, teach the Serrano names for animals and plants seen during the harvest.

Caring for the piñon groves and harvesting piñons the way their ancestors did is a form of land stewardship for the Yuhaaviatam people. They see these ancestral lands as cultural spaces to be cared for and protected.

PEER-REVIEWED MEDICAL sites note the health benefits of piñon nuts: antioxidants help lower the risk of cardiovascular disease; fiber, protein and

unsaturated fats help keep blood sugar levels stable; omega-3 fatty acids help build and repair brain cells; and manganese helps lower the risk of diabetes.

Kamran Zafar, field attorney for the Grand Canyon Trust, wrote in 2020 that Native peoples used piñon pitch in salves for open cuts and sunburns, and ground it into powder as an antiseptic for wounds. It was also used to fill cavities in aching teeth. Wood from piñon trees was valued as a construction material. Fields said piñon pitch is a good bonding agent.

Noted anthropologist Ruth Benedict (1887-1948) wrote in 1924 about the ceremonial and dietary importance of piñons and of their distribution among Serrano peoples.

“Piñon nuts were important in the diet of all these groups,” she wrote. “A trip was made over into the Bear Valley region every fall for these nuts. No group could go without its chief and the MaringaMühiatnim-Atü’aviatum group went together, under the leadership of the Maringa chief,” she wrote.

“The first two groups went first to Kupatcam, The Pipes, where the Atü’aviatum lived. From the time they left this place, the party began to witc-at. This term refers to communal, that is, ceremonial eating.

“When any ceremony was to be undertaken, the requisition for the feast upon the proper heads of families was the witc-at. So on this trip all provisions were turned into a common fund by the heads of the families, and distributed by the chief through the paha.

“The first piñon nuts were given to the chief by every family, and these were used for his witc-at at the annual feast which always followed this trip very shortly.”

According to Benedict, the Atü’aviatum leader “would invite as many other groups as could use the available yield in any particular year. The Serrano

“I FEEL A SPIRITUAL CONNECTION AS I HARVEST, FOLLOWING MY ANCESTORS FOOTSTEPS.”

clan extended the invitation to Cahuilla from the San Jacinto Mountains and Colorado Desert, and even to the Gabrielino groups on the coast. The harvest lasted from September through mid-October.”

Serrano culture bearer Dorothy Ramon (19092002) shared her recollections of piñon gathering in her story, “Gathering Pine Nuts.” She said the people went to tevayka (“the piñon pines”) every year and gathered and stored piñon nuts for later use and for eating during ceremonies.

Ernest Siva (Cahuilla/Serrano), Ramon’s nephew and President of the Dorothy Ramon Learning Center, said piñon harvests and deer hunts take place before the coming of the bighorn sheep constellation in the night sky, in order to provide food for the mourning ceremony honoring recently deceased loved ones.

“It was something my ancestors did before me,” Fields said. “They collected piñon as a source of survival, as a way of life. Today, I also harvest them – not as a form of survival, but as a form of cultural preservation. I like to think of it as a way that the culture is not forgotten. And for spiritual connection – I feel a spiritual connection as I harvest, following my ancestors’ footsteps.”

CLUB SERRANO MEMBERSHIP NOW GIVES YOU MORE!

Club Serrano members can now receive discounts of up to 35% off on tee times at Monarch Beach Golf Links. In addition, members can use earned rewards to play at this oceanfront golf course.

Featuring stunning views of the Pacific Ocean on nearly every hole, the Monarch Beach Golf Links is a one-of-a-kind golf course in Dana Point in Orange County, CA. The 18-hole, par-70 championship resort golf course was designed by master golf architect Robert Trent Jones, Jr., and offers unending variety of play. It is one of a few handful of oceanfront golf courses in California, featuring tight fairways and firm greens.

SAN MANUe L POW WOW 2024

Ancient Paths Bring Thousands to an Annual Gathering of Friends

By Ken Shoji

SAN BERNARDINO has long been celebrated as a destination along Route 66, the Mother Road linking America’s east with its west. This historic highway traces its path across plains, mountains and deserts following Native American trade routes established by these societies long before cars sporting “California or Bust” brought newcomers to Southern California. These ancient networks continue to thrive with Native culture, drawing people from all four directions for a unique annual celebration here in the ancestral Marra’yam (Serrano) territory of the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians. From Montana to Saskatchewan and Alaska to Canada, North America’s best powwow dancers, drummers and artisans have taken the long journey to San Manuel Pow Wow since 1996 to celebrate spiritual roots that tie Native people to all corners of the continent.

This year, the 28th annual pow wow took place the weekend of September 20-22 at California State University, San Bernardino. It drew 700 dancers, 28 drum groups and more than 140 vendors – a staggering crowd of 30,000 to 40,000 people – for what has been dubbed the ultimate pow wow due to its high level of competitive dancing and drumming. These thousands of spectators had the opportunity to immerse themselves in the best of cultural music, food, arts and dance, highlighting the richness and diversity of Native American life and tradition.

San Manuel Pow Wow stands as a symbol of Native resilience, reflecting the strength and fortitude of Indigenous communities. It offers a unique opportunity for competitors and participants to retrace the steps of their ancestors through their travels and in the motions and rhythms of their

Friends from all four directions are welcomed in the spirit of HOUPKCÜVA’ (togetherness) to our ancestral homelands of the Yuhaaviatam clan of the Maara’yam (Serrano) people in Southern California. In our Serrano language, the word HAMIINTAMC (Hello) has been voiced throughout the generations to greet groups of visitors who come to our Serrano ancestral homelands.

dances, continuing the path of the ancestors who established complex trade and ceremonial networks connecting all Indian Country through cultural sharing and trade.

“Our livelihood, cultures and traditions are based on sharing,” said drummer and pow wow host Glen Begay (Diné). “It’s a big part of our life to share, and that is a big reason we are here because San Manuel is

sharing with the Indian community, from throughout the U.S. and Canada, by giving back to others, enabling us to express what is most important this weekend.”

The gathering of friends at the San Manuel Pow Wow is a powerful symbol of unity and an opportunity for cultural preservation, giving people a cultural and spiritual home for the weekend, whether they traveled from Alaska or live locally.

HISTORY & HERITAGE

Traditional cultural educators from California tribes share music, arts and language.

THIS PAST NOVEMBER, the California Indian Cultural Education Day brought local third and fourth graders together to engage with California’s First Peoples through music, arts and language. Traditional cultural educators from the Yurok, Shingle Springs, Wilton Rancheria, Tuolumne and San Manuel Tribes also joined in the activities, creating an immersive, educational experience.

For the past 25 years, the event had been held at California State University, San Bernardino. But this year a new location was selected: the California State Capitol in Sacramento. Hosting the event here carried special significance for Indigenous participants, as the building was once associated with legislation that undermined Native Americans. San Manuel tribal citizen and Assemblymember James Ramos said, “This was very meaningful as I was able to share my culture and educate students in a place once associated with the loss of our rights.”

LL COOL J

Jan. 17

Tom Segura Jan. 23

Sebastian Maniscalco Jan. 30

HAUSER May 27

IN THEIR BLOOD

Three generations of leadership work to secure the future of the Tribe.

By Richard Arlin Walker / Photography by Cara Romero

SOME OF Latisha Prieto’s earliest memories are of accompanying her mother to General Assembly meetings of the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

“I didn’t really understand what was going on, but hearing all the things they talked about in the room, it started to make sense,” Latisha said. “It was like there are bigger things discussed here and I’m supposed to be learning from it.”

And learn she did. Today, Latisha is the Tribe’s elected Treasurer and Chairwoman of San Manuel Gaming and Hospitality Authority (SMGHA), the entity which owns Palms Casino Resort in Las Vegas.

She’s part of a lineage of leadership.

Her great-great-grandfather was Santos Manuel (1814-1919), the Yuhaaviatam kiika who led his displaced people from the mountains to soon-to-be reserved lands in the San Bernardino Valley. Her mother, Carla Rodriguez, a tribal elder, was the Tribe’s first Gaming Commissioner, former Chairwoman and currently the Secretary for SMGHA. Her daughter, Raven Casas, is a former Youth Committee member and MMIP advocate who wants to someday serve on Tribal Council and in the legislature. Her cousin, James Ramos, former San Manuel Chairman, is the only Native American in the state Assembly. Grandmother (Tutu), daughter and granddaughter have varied interests. Carla, 71, is a retired singer for the funk/soul/Latin cover band Full Circle. Latisha, 44, graduated from University of Redlands and earned a fiduciary specialty certificate from Harvard, with an educational background in business, financial management and specialized fiduciary training. Casas, 18, is a car buff who’s studying to be a mechanic.

But the wellbeing of the Tribe is their top priority –an inherent responsibility they feel every tribal citizen bears. The beauty, they say, is that anyone can make a difference and be part of a continuum of service that has made it possible for San Manuel to be one of the most philanthropic tribal nations in the United States.

“As Native American people, it is our responsibility to be involved in everything the Tribe does,” Carla said. “Some people can turn that off and I’m very outspoken when that happens, because Native people are born to do these things. Each and every one of us has a gift we were given. We have to discover what that is, nurture it and build it to make us who we are today.”

There is a lot at stake, Carla said.

“KNOW YOUR HISTORY and understand what it took to get us where we are today. Also, be humble.”

The federal government signed 18 treaties with tribal nations in California, but those treaties were never ratified. A treaty is a binding agreement between sovereigns and is called “the supreme law of the land” by the U.S. Constitution.

But because the treaty they signed was not ratified, the relationship between the United States and San Manuel – the trust obligation, the government-togovernment relationship – is one of good faith rather than legally binding. “We are fortunate to be in the position we’re in and to do the things we do,” Carla said. Indeed. It was not long ago – the time of the grandparents’ grandparents – that raids and bloodshed drove the Yuhaaviatam people from their homes in the mountains. But the people persevered. Santos Manuel’s generation passed the teachings on to the next generation. Young ones grew up to become culture bearers. There was cohesiveness in vision for the future.

Yuhaaviatam culture, language and values survived. The tribal nation is thriving. That doesn’t happen by sitting on the sidelines.

“I’m one of the older ones who saw us grow from poverty to where we are today,” Carla said. “And I teach my kids and grandkids that this can be taken away from us so prepare for anything in the future, because the government does encroach in various ways on tribes. We have to always protect it; it’s not a given thing.”

Latisha added, “That’s why it’s so important for us to mentor the next generation; we have that duty and obligation of upholding our sovereignty. If we don’t, it could be taken away from us.”

Like her mother, Raven found her voice in General Assembly meetings and inspiration in her forebears.

“I used to sit next to my Tutu at meetings and I had so many questions,” she said. “I had no idea what was going on, but I remember seeing all of them write in their notebooks, so I brought a notebook too. I wanted to be just like them.”

Raven is a part of the Serrano language revitalization program; her goal is to become fluent and teach the language to the next generation. She also testified before a State Assembly Committee regarding the low number of perpetrators prosecuted for crimes against Native women; the legislature approved a bill to clarify criminal jurisdiction on tribal lands and a nonprofit documented the number of MMIP cases in Central and Southern California.

“I remember my first time speaking in Sacramento,” Raven said. “I’m young, I’m Native, I’m female. Typically, when you’re younger, people don’t really listen to you. But I felt like my words were important, because I definitely had something to say and people needed to listen to me.”

Sitting in front of legislators, she remembered: “I’m not doing this for me, I’m doing it for my brothers and sisters who are missing and for their families. I’m doing it for my Tribe. I’m doing it for generations that will follow. And I know I can make a change with my voice.”

She added, “My grandmother and my mom always tell me this is our life, this is who we are. We are Native. We are strong Native women. We come from long lines of strong Native leadership.”

Seven generations have been born since Santos Manuel led the Yuhaaviatam people to the safety of the valley floor, and his descendants are guided by seven-generations thinking.

“The people I work alongside will often hear me say, ‘The decisions we’re making today are about honoring those who came before us and making sure we’re recognizing what they did to get us to where we are, and being mindful of our decisions and how they impact future generations’,” Latisha said. “It’s about honoring the past and securing the future.”

Latisha gave this advice to young people who are considering getting involved in tribal government:

“Start participating in your community. Build your understanding of what it means not only to be a leader but to be a tribal citizen who understands the work that goes into providing for the Tribe and

upholding self-sustainability,” Latisha said.

“Know your history and understand what it took to get us where we are today. Also, be humble,” she added. “You want to continue to grow and in order to do that you have to listen to others – tribal leaders, elders, people from your age group, youth. You have to take all of their concerns into consideration. You can’t have tunnel vision. You have to have a wide perspective to make sure you’re doing all you can to uphold tribal sovereignty.”

Raven expects she’ll run for Tribal Council someday and, later, the state legislature.

“My heart is fully set on taking a role in Tribal

Council, because I was born to be a leader in our Tribe,” Raven said. “I was born to take a seat there and make decisions for my generation and generations to come. Having a position in Sacramento would be great, but I know this is where my home is.

“There are big decisions that need to be made for my Tribe. I know I need to take a position here and that’s definitely what I plan on doing. This is the life I was born into,” she added. “Even if I didn’t want to, it’s something I have to do, and I’m more than happy to do it. If I and others in my generation don’t do it, our Tribe will die. And I will never let that happen as long as I live.”

NEXT GENERATION

NEW MEMBERS NEW HOPES

The San Manuel Youth Committee welcomes tribal citizens to prepare them for a life of service and leadership.

By Terria Smith / Photography by Tiffany Melendez

THIS PAST FALL, a new school year brought new members to the San Manuel Youth Committee, an opportunity that offers a chance to learn culture, build leadership and strengthen friendships among the younger tribal citizens.

While each new member was inspired to join for different reasons, there was a common thread: family. Audrey Hernandez, the committee’s new secretary, said that getting to work with her cousins was something that motivated her.

“I look up to my cousin, who is the Chair of the Youth Committee and how he ran the meetings,” she said. “I think, ‘What if I become Chair one day?’ I want to run them just like he did.”

As this year’s newly elected Youth Committee Chair, Annabella Hernandez explained that she wanted to join because, “My brother is a part of it and I was inspired by what they do for the community.”

Outside of what directed them toward leadership, they also have their own goals and aspirations for service on the committee.

“My goal is to make a positive difference in my community,” Annabella said. “I love getting the chance to fundraise and help people around me.”

“What we’ve achieved so far is beyond my expectations,” said newly elected Vice Chairman Nekoli Hernandez. “Meeting with high officials and holding events, such as the Tribal Youth Gathering, are things that I never would’ve thought we would have been doing, I’m glad to be a part of it.”

Committee members are elected each year. Serving one-year terms provides opportunity and experience for the youth to serve in different roles and gain a broad range of leadership skills.

During the year, the Youth Committee meets regularly to actively discuss interests that will directly benefit the tribal community. Their participation in

decision making is encouraged by tribal leadership, providing them with opportunities to contribute creatively with their skills and talents. The Youth Committee plans and hosts an annual Tribal Youth Gathering, manages a holiday donation drive and engages in advocacy opportunities to further the work of protecting tribal sovereignty and educating others about the Tribe. The members have said that being organized as well as being involved in tribal culture are responsibilities they have as committee members. But what some find is their most important responsibility is to one another.

“My biggest responsibility is to be there for our other members,” said Nekoli. “It helps us voice our concerns if we see something that we don’t think is the best for our community.”

Ultimately, the experience of serving on the Youth Committee is something they believe will help them in the future. Riley Murillo, the committee’s new Treasurer, said she hopes this experience will help her when she has a business or serves on the Tribal Council.

“I believe that my service on the Youth Committee will help me advance in skills leadership and communication. This is a very great opportunity to prepare to be a future tribal leader,” Annabella said. “And I’m grateful to my Tribe for the experience.

Left to right: Nekoli Hernandez (Vice Chairman) Halani Zavala (Youth Committee Member) Riley Murillo (Treasurer) Annabella Hernandez (Chairperson) Audrey Hernandez (Secretary) Roman Hernandez (Representative) Quoymee Chacon (Youth Committee Member)

SHARING HISTORY

Creating a familial culture at Palms Casino Resort by telling the story of the Yuhaaviatam.

By Richard Arlin Walker / Photography by Robert John Kley

THE HEARTBEAT OF the Yuhaaviatam people – the pulse of Yawa’ – can be felt in Palms Casino Resort in Las Vegas. Away from the music, dining and gaming, tribal elder Carla Rodriguez, former Chairwoman of the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians and current Secretary for the San Manuel Gaming and Hospitality Authority (SMGHA), shares the story of her people with Palms team members.

It’s a powerful story of resilience, of how a people survived incursions and bloodshed and displacement but never strayed from their culture of giving and, over time, became one of the most successful and philanthropic tribal nations in the U.S.

Palms, purchased by the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians in 2022 through the SMGHA, is the first and only Native American tribe to own and operate a casino resort in Las Vegas.

Rodriguez’s presentations – an introduction to Yuhaaviatam history, culture and values, particularly Yawa’, which means acting on one’s beliefs – are called “fireside chats.” The term conveys the informality and intimacy of the gatherings.

“We sit in a half circle and I go through photos and explain what each one means. It’s about our history and how we got to where we are today,” Rodriguez said. Rodriguez conducts fireside chats over two days

each quarter – two sessions a day, two to three hours each session. “I carry a lot of history and that’s what they want to learn: How did we get where we are today and what was it like before? What was it like growing up on the Reservation? What was it like at school? What does the Tribe’s future look like?”

Rodriguez added, “During the fireside chats last quarter, we showed a four episode documentary about our Tribe. Each episode tells the story of what our ancestors endured and had to sacrifice to get where we are today. It was not an easy life. But today, our young people can go to school anywhere in the world and we are able to give back to our community.”

“IF YOU TREAT TEAM MEMBERS WITH RESPECT, YOU’RE GOING TO GET RESPECT BACK. I LOVE SHARING EVERYTHING I CAN.”

SAN MANUEL’S philosophy of caring has expanded into Nevada, where the Tribe has donated more than $400 million to tribal governments, nonprofits and public service agencies over the last 20 years, and since opening Palms under SMGHA, has awarded $6 million to schools and nonprofits in Las Vegas.

San Manuel’s entry into Las Vegas, which is within the territory of the Paiute Tribe, has also boosted the Indigenous economy and brought awareness to Native sovereignty and protocol.

“Out of respect for the Paiute Tribe, we asked for their permission to be there,” Rodriguez said. “We did a land acknowledgment in front of Palms, saying thank you to the tribes that have ties to Las Vegas. We’re hoping more Native people will become involved in the gaming industry, and I believe we’re seeing that happening now.”

Rodriguez carries her fireside-chat approachability and her genuine desire to forge connections with everyone she meets throughout Palms, making it

abundantly clear to team members that they work for an ownership that is more focused on building a brighter future for all who work there than it is on profit margins.

“We’re not a corporation and it’s not unheard of for me to get out there on the floor and talk to team members,” she said. “That personal touch helps them work even better. If you treat team members with respect, you’re going to get respect back. I love sharing everything I can. If it helps somebody be more comfortable in their workplace, then that to me is everything.”

EQUALITY AND FAIRNESS

How San Manuel Tribal Court upholds fundamental principles of tribal culture.

By Margo Hill-Ferguson / Photography by Tiffany Melendez

ONE ASPECT OF tribal sovereignty is the ability for tribes to make their own laws and be governed by them. Tribes have inherent sovereignty, they retain the right and power to govern their jurisdiction. Tribes have utilized their sovereignty since time immemorial and maintained their governance even after European arrival in America; they conduct their own affairs and depend upon no outside source of power to legitimize their government.

As sovereign nations, tribal governments have the power to make laws governing the conduct of persons in their jurisdiction and establish bodies such as police departments and courts to administer justice. No two governments are the same. While the United States of America borders Canada, their government systems vary, as do tribal nations. Each tribe builds their governance from their peoplehood, embedding their cultures into the fabric of their governing documents.

While the Constitution of the United States was being crafted, the Founding Fathers made an explicit effort to create distinctive pathways to maintain relations with tribal nations. Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the Constitution – commonly referred to as the Indian Commerce Clause – calls out “Indian Tribes” as an entity that Congress may enter into commerce with. While tribal nations were treated as distinctive political entities in charge of their own people, challenges to that authority came in some of the earliest cases heard before the United States Supreme Court.

The Marshall Trilogy is a set of decisions handed down between 1823 and 1832 that are still referenced in cases heard today. In the case Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Supreme Court ruled that Indian tribes were regarded by the nations of Europe and by the United States “as distinct, independent political communities, retaining their original natural rights.” Chief Justice

John Marshall wrote this ruling in the landmark Supreme Court case. The legal and political relationship between tribes and the federal government has been augmented by Congress, the executive branch, the courts and the tribes themselves.

The San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, as a distinct sovereign that never relinquished its status as a Nation, has the right to determine how to exercise its tribal sovereignty. One expression of that sovereignty is the Tribal Court.

In 2003, the Governing Body of the Nation passed a law that called for the creation of a court system. The San Manuel Tribal Court opened its doors in 2009 and strives to offer a culturally sensitive and accessible forum for the resolutions of disputes before it.

The San Manuel Judicial Code was adopted in 2003 to protect and promote sovereignty, strengthen selfgovernment and provide for the Tribe’s judicial needs. The Judicial Code established the San Manuel Tribal Court and Judiciary Committee. The San Manuel Judiciary Committee was the designated group of tribal citizens delegated the authority to oversee court functions. At its inception, this group consisted of members of Tribal Council, as well as elected tribal citizens. As the Tribe has grown, a decision was made to shift this position to all elected citizens separate from other bodies of the tribal government, which is now known as the Judiciary Board. The Judiciary Board is still tasked with the same goal of overseeing the operation and administration of the court while weaving tribal culture, beliefs and common practices into its functions. This change was made through the legislative process utilized by the tribal government to protect the integrity of the court process and ensure public accountability for its performance.

According to the Vice Chair of the San Manuel Judiciary Board, “Having the ability to use a tribal court space to take back what the legal system means for an Indigenous community is why we have a tribal court.”

The Bureau of Justice Assistance, a component of the Office of Justice Programs of the U.S. Department of Justice, sets suggested tribal court performance

standards and states that “Integrity should characterize the nature and substance of [tribal] court procedures and decisions. The decision and actions of a [tribal] court should adhere to the duties and obligations imposed on the court by relevant law, as well as administrative rules, policies and ethical and professional standards.”

Accessibility of the Tribal Court

Tribal courts are entrusted with many duties that affect individuals and organizations involved with the judicial system – including litigants, attorneys, witnesses, social service agencies and members of the public. If a court is not managed properly, there can be serious consequences for the persons involved and community members.

Jurisdiction of the court extends beyond the citizenry of the nation, certain civil issues involving non-Native people come before the court. One of the important functions of Tribal Court is to provide effective participation to all who must appear without undue hardship or inconvenience. The San Manuel Band of Mission Indians adopted laws governing the rules of court necessary to support the functionality of the court to provide justice that aligned with the values of the San Manuel people and due process expected in a court of law. San Manuel Tribal Chief Judge Yvette Ayala Henderson and the Court Administrator work to ensure the court staff are courteous and responsive to the tribal citizens and public, meeting all requirements and responsibilities that affect individuals involved with the court system. As Judge Ayala Henderson stated, “Fairness is a guiding principle of the San Manuel Tribal Court.”

Ayala Henderson was a jurist in state court before serving as Chief Judge for another tribal community for more than four years, which means she’s familiar with the concepts that are predominant in tribal courts and communities.

“I am not a member of an Indigenous nation but the values of tribal communities align more with my personal values,” she said. While state court systems tend to be focused solely on the imposition of punitive accountability for harm, tribal nations begin from the premise that all persons have value and are entitled to an opportunity to regain the balance that makes them productive members of their community. If restoration of balance to individuals on either side of the legal dispute is the starting point, justice becomes about accountability and atonement for harm that allows for healing and repair to all persons involved. This is how communities are made whole.”

The San Manuel Tribal Court works to provide due process to tribal citizens and those who have business before them. The court is an important part of how the Tribe exercises its sovereignty and protects the health, safety and moral welfare of all who come under its jurisdiction. It is at the core of every governmental body of the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians to provide equality and fairness, fundamental principles that are at the center of their cultural beliefs.

FROM THEN TO NOW

A look at the resilience and determination of the Yuhaaviatam to remain self-sufficient and sovereign.

Since Time Immemorial

Maara’yam people inhabit the mountains, valleys and deserts of Southern California.

1700s-1820s

Spanish missionaries and military encounter the Yuhaaviatam (one clan of the Maara’yam), which they call “Serrano” or “highlander.” Many Maara’yam are forced into the mission system as slave labor for Spain.

1880s

Native American boarding schools are established in the U.S. with the primary objective of “civilizing” or assimilating Native American children and youth into EuroAmerican culture, while destroying and vilifying Native American culture.

Early to Mid-1900s Tribe adapts and adjusts to reservation life. U.S. government continues to dictate what the Tribe can and cannot do.

1966

Articles of Association are adopted by San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

President Ford signs the Indian SelfDetermination and Education Assistance Act, a federal policy of Indian selfdetermination, first declared by President Nixon. CREATION

1850s-1860s

American settlers invade Serrano territory. CA governor instructs militias to exterminate Native people. Yuhaaviatam are killed and chased out of their territory.

1866

Raids and bloodshed decimate the Tribe. Kiika’ Santos Manuel makes a decision to courageously bring the remnant of his people from the mountains to safety on the valley floor.

1879

Carlisle Indian Industrial School opens in Carlisle, PA. Thousands of Indian children are shipped from their homes and families to the school to “Kill the Indian, save the man,” to assimilate them into mainstream society.

December 29, 1891

U.S. President Benjamin Harrison signs Executive Order establishing the San Manuel Indian Reservation with 640 acres. Serrano ancestral territory encompassed 7.4 million acres in California.

1934

Indian Reorganization Act is enacted by U.S. Congress, aimed at decreasing federal control of American Indian affairs and increasing Indian self-government and responsibility.

1970

In address to Congress regarding the federal policy of terminating relationships with tribes, President Nixon states, “This policy of forced termination is wrong.” He then outlines a policy of selfdetermination rather than termination.

1975

Photo courtesy of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library

1980s

SMBMI seeks new business opportunities to strengthen sovereignty and journey towards self-sufficiency.

1978

Indian gaming movement begins with Seminole Tribe of Florida.

SELF-DETERMINATION

1986

San Manuel Indian Bingo opens.

1987

California v. Cabazon: U.S. Supreme Court landmark decision affirms right of tribal governments to conduct gaming on their lands.

1988

Indian Gaming Regulatory Act passes, creating statutory framework for Indian gaming.

1990s-2000s

Tribe takes an active role in passing Proposition 5 and Proposition 1A.

1994

San Manuel Indian Bingo adds gaming operations and advances goal of economic selfsufficiency.

1998

Proposition 5 is supported by 63 percent of voters in favor of gaming by Indian tribes in California. A lawsuit by a labor union causes the measure to be struck down by California Supreme Court.

2000

Proposition 1A, supported by 65 percent of California voters, changes the state constitution and provides exclusive right to Indian tribes to operate a limited scope of casino-style gaming on Indian lands, in accordance with federal law.

2006

San Manuel Band of Mission Indians breaks ground on San Manuel Village in Highland, CA, a mixed-use, offreservation, commercial development.

2007

Residence Inn by Marriott opens in Sacramento, CA. The project is from the Three Fires intertribal economic partnership, which includes San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

2008

Hampton Inn and Suites Hotel opens in Highland, CA, at San Manuel Village, a development of the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

2019

San Manuel Gaming and Hospitality Authority forms to explore economic growth opportunities.

2021

San Manuel Casino becomes Yaamava’ Resort & Casino at San Manuel.

Yaamava’ expansion project opens including gaming spaces, new restaurants, lounges and hotel tower, as well as retail, spa and pool amenities.

Hamiinat magazine launches.

2005

New San Manuel Indian Bingo and Casino opens.

Residence Inn by Marriott opens in Washington, D.C. The project is from the Four Fires intertribal economic partnership, which includes San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

2016

SMBMI acquires sacred lands in San Bernardino Mountains with purchase of Arrowhead Springs Hotel.

2018

Opening of the Autograph Collection, The Draftsman Hotel, in Charlottesville, VA, a joint venture that includes the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

U.S. Supreme Court overturns the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA); open door to state-authorized sports gambling.

2022

San Manuel Gaming and Hospitality Authority opens the Palms Casino Resort in Las Vegas.

San Manuel leads defeat of sports gambling ballot initiative in California; 83% of voters reject Prop 27.

2023

San Manuel Landing opens.

UNSUNG HEROES

The California Native American Caucus honors Native changemakers.

By Dalton Walker

A GROUP OF California state lawmakers, members of the California Native American Legislative Caucus (CNALC), made history this year when it celebrated five remarkable Native people known for their lasting impact and eye for significant change.

The CNALC was formed in March 2021 to increase awareness and inform state lawmakers about tribal nations that are native to California. The caucus has a 10-person executive committee made up from the Assembly Select Committee on Native American Affairs, 23 state Senate members and 33 state Assembly members.

Celebrating its inaugural class during a floor session in August, Assemblymember and Caucus Chair James C. Ramos said this year’s criteria were based on leadership, courage and positive change to tribal communities.

“I wanted to ensure that some of the honorees, who might not be as well-known as others, were recognized,” he said. “They have performed exemplary work in seeking equity and justice on issues such as missing and murdered Indigenous people, preserving Native American culture, pioneering school desegregation or leading a tribe. They are unsung heroes.”

Ramos explained that the inaugural class highlighted four strong Native American women who are giving back to their communities. “Culturally it makes sense as women are held in a high regard within our Native American communities. It was fitting to include San Manuel Chairwoman Lynn

“I WANTED TO ENSURE THAT SOME OF THE HONOREES WERE RECOGNIZED.”

Valbuena as part of the California Native American Legislative Caucus’ first honorees,” Ramos said.

Valbuena has served San Manuel for nearly five decades in a variety of roles and this year was elected to a 6th term as Chairwoman. As Chair, she served on the San Manuel Constitution Working Group and was a signer of the new constitution adopted in 2021.

This year also marks her 29th year as Chairwoman for the Tribal Alliance of Sovereign Indian Nations, an intergovernmental association of Southern California tribal governments. She received the 2024 Tribal Leadership Council Lifetime Leadership Award as well.

HERE’S A LOOK AT THE OTHER HONOREES:

In 1923, a young Paiute girl named Alice Piper initiated integration for Native students at a high school in Big Pine, California. She sued the district on the grounds that her 14th Amendment rights had been violated.

The California Supreme Court unanimously ruled in her favor in 1924. Chief Justice Earl Warren later cited their case as a precursor to the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education decision in 1954. In 2014, 19 years after her death, the Big Pine Paiute Tribe and Big Pine School District unveiled a statue of Piper. June 2 is known as Alice Piper Day.

Morning Star Gali, a Pit River Tribe citizen, is known as a tireless advocate for Native people. She is the founder and director of Indigenous Justice, a nonprofit that advocates for missing and murdered Indigenous people, climate and gender justice and sacred site protection. Her efforts reach across the state, and the impacts will span generations.

Taralyn Ipiña is Yurok and serves as her nation’s first Chief Operations Officer. She has advised tribal leadership for nearly two decades and helped lead the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples Day of Action at the capitol in 2022, along with other legislative advocacy efforts. She recently celebrated her lifetime efforts to restore salmon to the Klamath River when a series of dams were removed.

William Franklin’s legacy lives on in the form of a bronze statue outside the California Capitol, as a result of Ramos’ bill, AB 338. Franklin died in 2000. Last year, the likeness of the late Miwok tribal elder was chosen to represent the Miwok and Nisenan Tribes whose ancestral lands make up present-day Sacramento. This statue is the first and only Native American statue to ever sit on Capitol grounds.

PUYU’HOUPKC ˇ AV

(poo-yoo-hope-k-chahv)

Together

Puyu’houpkcav: together. When all are together as one, we accomplish more. We strive each day towards unity of purpose and spirit.

In this section we learn about the Tribe’s innovative – and involved – approach to philanthropy. We hear the harrowing story of a victim of human trafficking and learn how she and San Manuel are working to put an end to this practice. We see how education can strengthen tribes across the nation and create more understanding between non-Natives. We see how new efforts from the government could bring healing to Indigenous people and see how leadership at San Manuel says thank you to its team members and hear from one team member about her experience with the Tribe.

BY MARGO HILL-FERGUSON

ONE STORY SURVIVOR’S

January is human trafficking awareness month. The following is an account of how easy it is to be trafficked, how pervasive the problem is and what we can do to stop it.

HUMAN TRAFFICKING SURVIVOR RACHEL C. THOMAS, FROM PASADENA,CALIFORNIA, CAME FROM A STABLE, LOVING HOME.

Her mom, an attorney; her dad, a church deacon. And that is a message Thomas wants to get across: not all victims look like the victims in the movies. In fact, she played sports, was voted prom queen and had never experienced abuse.

Thomas was in her junior year at Emory University when she was approached at a college hangout by Mike, who said he was a modeling agent. He was nice, well-dressed and had what appeared to be other models Rachel’s age who sang his praises.

“And that’s how it starts,” Thomas said.

Thomas, who has operated her own education group for more than a decade, is an educator and advocate fighting human trafficking. She was also appointed to the White House Advisory Council on Human Trafficking in 2020 by President Trump and again in 2022 by President Biden.

IN THE UNITED STATES, on average there are an estimated one million human trafficking victims annually, which includes labor trafficking and sex trafficking. Approximately 300,000 of the one million domestic victims are child sex trafficking victims. The legal definition of sex trafficking is “causing a person to engage in commercial sexual exploitation by use of force, fraud or coercion.”

The average age of entry into sex trafficking is 1214 years of age. The average life expectancy for the victim is seven years from the day she or he is first trafficked. One in five sex-trafficked victims are boys. Human trafficking is the number-one growing crime

in America. In a few short years, it has surpassed weapon sales as America’s second most lucrative criminal activity.

Young people can be preyed upon, online or in person. Predators don’t come right out and say they are going to ruin your life for their gain. Thomas explained, “A relationship is formed, a trust is built, there’s flattery.” Whether a relationship is built through a believed romance or a so-called “business opportunity” like modeling, the trafficker knows how to manipulate young people’s emotions and vulnerabilities.

Rachel’s Story

Thomas’ trafficker (who presented himself as a modeling agent) offered to pay for a photo shoot so she could get a “comp card,” a model’s resume that includes a headshot and multiple photos, height and weight. All the things that matter in the industry.

“He wanted to invest in my career,” said Thomas. “And I didn’t want to miss out on anything, plus these other women were so confident in him and talked so great about him.”

Thomas called Mike and he invited her to tag along with Michelle, a girl Thomas had met with him the week before, to a photo shoot. Thomas did everything right: she brought a friend and told her parents where she was going.

“But at that first photoshoot, I let my guard down because everything was so professional. Everyone was so nice. There were photographers, hair and makeup artists and other models.”

“About two weeks later, he got me a paid modeling gig,” Thomas said. “Mike invited me to the set of a music video for a Grammy award-winning artist. I did the video. I got my hair and make-up done, they put me in a cute outfit and I danced. I love to dance anyway.”

At the end of the shoot, Mike congratulated her and said she earned $400. Thomas, a college student living on a modest monthly allowance from her

parents, was excited. Mike had her fill out a W-9 with her permanent address, her Social Security number and her current address, where she was living with her best friend near campus, to receive payment, something she had done for other employers.

TWO WEEKS LATER , Thomas witnessed Mike escalate into violence over something small, which ended up with him beating Michelle. “I didn’t know why this pretty, young girl was dating this older guy. I was scared and just wanted to get back home,” she said.

The next morning, Thomas called Mike to tell him she didn’t want to model anymore. “I heard him shuffle some papers, and then he said ‘You are going to do what I tell you, or someone is going to get hurt. I own you,’” Thomas recalled.

He read off her parent’s home address from the W-9 she had filled out for the modeling gig payment and then told her where to meet him that night. “He said if I didn’t go, he would come for me. Then he read off my address near campus and asked if I understood. I couldn’t respond because I couldn’t even process what was happening. And then he just hung up,” Thomas said.

“I had never called 911 and I had never been in an emergency situation. I didn’t know if the police responded to threats or if I could make a report on Michelle’s behalf because he had hit her, but he hadn’t hit me. I didn’t want to call my parents, get them worried and get a lecture. I decided to stay on his good side and see what he wanted me to do,” said Thomas. That night, Mike had a buyer waiting. He told her what was expected and then Thomas started crying and said, “Please don’t make me do this.” He then grabbed her arm and said, “I told you. I own you and you’re going to do this.”

“That was the first night I was forced into human trafficking,” Thomas said.

In just five weeks, Thomas had succumbed to a

As compared to Caucasian women, Indigenous women are 2X MORE likely to be raped and have a 3X HIGHER murder rate

Up to 50,000 women and children in the U.S. are trafficked for sex every year

1,091,000 1.7 MILLION CHILDREN IN SEX SLAVERY 40% of sex trafficking victims are Native women

27.6 MILLION people in modern slavery globally

PEOPLE IN SLAVERY IN THE USA

USA RANKED AS ONE OF THE WORST COUNTRIES FOR HUMAN TRAFFICKING

56.1% OF INDIGENOUS WOMEN HAVE EXPERIENCED SEXUAL VIOLENCE

RESOURCES

National Human Trafficking Hotline humantraffickinghotline.org

1-888-373-7888 TEXT 233733

Cyber Tipline report.cybertip.org

Magdalena’s Daughters magdalenasdaughters.org 909-906-0472

Million Kids millionkids.org

National Center For Missing & Exploited Children missingkids.org/home 1-800-843-5678

Rachel C Thomas (RCT) rachelcthomas.com/do-something rachelcthomas.com/parent-resources

Radiant Futures radiantfutures.org 877-531-5522

Rescue America rescueamerica.ngo 833-599-3733

Safe Family Justice Centers safefjc.org/contact 951-955-6100

Suicide Crisis Lifeline 988lifeline.org CALL OR TEXT 988

modeling agency scam, she was threatened with violence, the death of her parents and open lines of credit in her name. And this was only the beginning. Five months after that, she succumbed to coercion, believing she was a worthless piece of property and that there was no escape and no hope for redemption.

“Trafficking involves every type of abuse: sexual, physical, mental and spiritual,” Thomas said. “There were so many red flags; there were so many vulnerabilities that were exploited. But I was unaware of what human trafficking was and the tactics of a trafficker,” Thomas said.

Thomas shared that Mike was the scariest person she had ever met and with the constant threats to kill her and her parents if she went to the police, she was too scared and manipulated to defy him or go for help.

Thomas was forced to work in a strip club and she was trafficked at music festivals and sporting events.

“Anytime there are events and men with disposable income, you will find human trafficking,” she shared. “It happens all around us.”

A year later, another victim of Mike’s got the courage to go to the police and Thomas agreed to work with the FBI, testify to the grand jury and do some undercover work. Eventually it became too dangerous

to stay with her roommate so Thomas went home.

“While I was being trafficked, I talked to my parents, but only when I could sound happy and make up something fun I had done the weekend before,” Thomas shared. “But when they picked me up at LAX, I told them what had happened.”

Her dad said, “Rachel, no matter what, we love you, and God loves you.”

Risks for tribal communities…

Familial trafficking happens in all communities, including Indigenous. Other risks to Native communities include people who prey on 16- and 17-year-old tribal members with the sole intention of exploiting them, particularly young people who accrue certain benefits from the limited number of tribal nations that extend general welfare benefits to their citizens.

Why people stay in commercial sexual exploitation, and how others get out…

Thomas said, “We were lucky that the law enforcement officer took it seriously. He didn’t dismiss us as prostitutes.” Many survivors get out with the support of community organizations; some because their trafficker went to jail; other victims develop a drug

habit and are no longer as valuable to their trafficker. They need the support of the community and organizations who can step in with resources to help. Thomas said, “For me, it was police intervention, but for others, it’s community organizations and resources that help them get out.”

How is San Manuel Band of Mission Indians helping?

The San Manuel Band of Mission Indians has actively supported community organizations dedicated to combatting exploitation and abuse. This includes partnering with Magdalena’s Daughters, a therapeutic residential facility that equips individuals who have been sexually exploited with essential life skills. The Tribe has also contributed to the Million Kids mission, which collaborates with local law enforcement, corporations, civic groups and school personnel to protect children from predators by addressing sex trafficking, child abuse and online exploitation. Most recently, San Manuel supported Radiant Futures, an organization focused on creating safer communities through crisis support services for survivors and educational programs to prevent domestic violence and trafficking. As a new award recipient from the Tribe’s 2024 grant cycle, Radiant Futures now serves all local counties.

The Tribe has further implemented internal initiatives, including collaboration with the Riverside Sheriff’s Department to provide human trafficking training for tribal and corporate leaders, as well as team members. Additionally, San Manuel’s Human Resources Department developed a Family Internet Safety webinar with resources and tips for staying safe online and regularly publishes a team member newsletter focused on human trafficking awareness. How can parents and communities prevent human trafficking in their community?

People need to be educated on human trafficking that happens in their communities and trained to identify the signs of a predator.

Thomas suggests parents be a listening ear for their children on any topic. A lot of kids don’t talk to parents if they feel like they will be lectured or get in trouble.

Community members can call hotlines to help get someone out of a bad situation.

What Rachel Thomas is doing now….

Rachel runs a prevention program called “The Cool Aunt.” She believes youth need safe adults and that it takes all of us as community members to fight human trafficking. Thomas stated, “We also need to prosecute ‘Johns,’ the men buying sex, and make sure they don’t get off with a slap on the wrist.”

Visit rachelcthomas.com to find the eight critical things we can do to combat human trafficking. For free access to “The Cool Aunt Series,” visit TheCoolAuntSeries.com then click on “Purchase Now” and enter offer code “SanManuel”

Thank You!

Thank you Gaming America Magazine and Global Gaming Awards, for recognizing the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians as the 2024 Responsible Business of the Year.

We are proud to be honored among our peers for our commitment to set the standard for tribal governments, gaming operations, hospitality businesses and philanthropic organizations connected to global gaming.

California’s FIRST PEOPLES

An annual celebration to educate and enlighten.

By Angelica Loera / Photography by Jaquai Herrera

CALIFORNIA NATIVE American Day (CNAD), celebrated on the fourth Friday of September, is a powerful occasion to honor the distinctive cultures of the Indigenous peoples of California. Established in 1998, the day aims to dismantle misconceptions surrounding California Native Americans, who have historically been misrepresented in education and popular culture. This celebration not only highlights the triumphs and struggles that shape their rich history but also calls for greater awareness and understanding of ongoing contributions.

For too long, California history began with the arrival of European explorers, neglecting the deeprooted societies that thrived long before. Native populations were often stereotyped or reduced to simplistic images of teepees and drums. CNAD seeks to rectify this narrative, emphasizing the importance of recognizing the diverse tribal groups that have inhabited the region for thousands of years.

Attending local schools, tribal citizens like James C. Ramos noticed how the Native American histories were not reflective of his personal experience growing up on the San Manuel Indian Reservation.

“I attended Belvedere Elementary with my cousins and one day a teacher played a song using a drum, an instrument not local to Southern California tribes. This teacher asked us to share with the class what the meaning of the song meant. We replied we did not know, the teacher said, ‘Well you must not be Indian enough.’”

This experience had a deep impact on him and in 1998, he worked with the local school district to start a California Native American Day Indian Conference. Since that time the conference has educated more than 50,000 third and fourth graders by allowing them to experience the culture of California’s first peoples. The students participate in language, arts and music, all meeting the social science standards in an engaging and experiential manner.

To illuminate California’s vibrant Native tapestry, the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians and California State University, San Bernardino (CSUSB)

partner to host California Native American education, discussions and a celebration across several days in September. During a week-long field trip, 1,500 local students visit CSUSB to engage in workshops about the culture and traditions of Southern California’s Native American tribes. San Manuel Band of Mission Indians also collaborates with the university to host a gathering of local dignitaries, elected officials and education leaders, focusing on the impact of curriculum and legislation regarding the recognition of the unique identities and issues facing the state’s First Peoples.

To cap off the week, an evening celebration is held on campus on the fourth Friday of September. The event is free and open to the public, and attendees can experience culture and explore these themes for themselves. Bird Singers and dancers in traditional regalia bring to life the stories of their tribe’s history and cultural values. Native artisans also showcase their crafts, including traditional jewelry, basketry and textiles, while food vendors feature traditional foods like fry bread.

CNAD is not just a celebration, but also a call to action for all Californians to engage in learning about the music, art and culinary traditions of their state’s Native peoples. By bringing together students, community members and leaders, CNAD fosters a deeper understanding and appreciation of the diverse tribal cultures that have shaped California’s identity. Ultimately, it invites everyone to participate in the journey of recognition and revitalization of Native American voices, ensuring that their legacies continue to thrive for generations to come.

Another STEP TOWARD HEALING

A painful history of forced boarding schools – and a hope for amends.

BY RICHARD ARLIN WALKER ILLUSTRATION BY MER YOUNG

BBryan Newland visited Alcatraz island in 2023 and looked down into the underground prison cell where 19 Hopi leaders were held 130 years earlier for refusing to send children from their villages to boarding school.

The men were imprisoned there for two years, more than 1,000 miles from their families and homelands.

“As I stood there, I imagined their lives, their hopes for the children in their villages and their experience with the U.S. Government,” wrote Newland, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs.

“I also reflected on our work … to tell the truth about our nation’s history of operating federal Indian boarding schools. I thought of the hundreds of people we have met in communities across the country, who came to share their experiences, and their relatives’ experiences, at federal Indian boarding schools –many, for the first time.”

On July 30, the Interior Department released the second and final volume in its investigative report documenting the history and legacy of U.S. federal Indian boarding schools. Tens of thousands of Native children were forcibly removed from their families from 1871 to 1969; many died from sickness, neglect or abuse.

Newland (Ojibwe) and Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) hope the report will push the U.S. toward full accountability for the painful legacy of the federal Indian boarding school era and support healing and redress for Native communities.

Volume 2 expands on information contained in the first volume, released in 2022, regarding the number and location of boarding schools, student deaths, number and location of burial sites, names of religious institutions and organizations that operated the schools on behalf of the government and federal dollars spent on operating the schools – more than $23.3 billion in 2023 dollars, according to the report.

This volume also updates the official list of federal Indian boarding schools and maps to include 417 institutions across 37 states or then-territories. It provides profiles of each school and confirms that at least 973 Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children died while attending federally operated or supported schools. The report identifies at least 74 marked and unmarked burial sites at 65 school sites.

The volume recommends the Federal Government take steps to acknowledge its role and repair the generational damage caused, including establishing a national memorial to acknowledge and commemorate the experiences of Indian tribes; identify and repatriate remains of children who never returned home; return former federal Indian boarding school sites to tribal nations; and invest in further research regarding the present-day health and economic impacts of the federal Indian boarding school system.

“For the first time in the history of the country,” Newland wrote, “the U.S. Government is accounting for its role in operating Indian boarding schools to forcibly assimilate Indian children, and working to set us on a path to heal from the wounds inflicted by those schools.”

Haaland launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative in 2021 to document the troubled legacy of federal Indian boarding school policies and address its intergenerational impact.

In late 2023, Haaland and Newland conducted a 12-stop tour across the country – called the Road to Healing – that provided survivors the opportunity to share with federal officials their boarding school experiences. Many of those stories are included in an oral history collection that will be accessible to the public, according to the Interior Department.

In addition, the Indian Health Service and the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration began offering support services to boarding school survivors.

THE U.S. BOARDING school system was a model for Indigenous boarding school systems in other countries – countries that are ahead of the U.S. in confronting that troubled history.

Canada’s efforts began nearly 20 years ago. The government apologized and paid settlements to more than 79,000 former students; established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission and a National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation; and designated Sept. 30 as National Day for Truth and Reconciliation to recognize the survivors of residential schools, their families and the children who never returned home. The federal government also provides counseling and crisis support services for survivors and family members.

Australia announced in 2021 it would pay hundreds of millions in reparations to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who were rounded up by government officials and sent to boarding schools and churchrun missions. Australia estimates as many as one in three Aboriginal children were removed from their families and sent to schools and missions between 1910 and 1970.

“Comparable to Native American boarding schools in the United States and the Canadian residential schools for Indigenous children, Australia’s program aimed to eliminate all traces of Indigenous culture from their wards,” The Washington Post reported in 2021. “Their actions ended up scarring many of the children for life, according to Australia’s Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.”

Some reviewers of the report are grateful that the two-volume report acknowledges the tragedy of the forced boarding school era, but they say some important facts are missing. The two-volume report, while comprehensive and exhaustive in its study, does not include information about federally-run day schools, where children were subjected to abuse.

John Boone, a teacher at Polacca Day School on the Hopi reservation, was sentenced to life in prison in 1987 for sexually abusing students. The government paid $13 million to settle eight related lawsuits, but a number of boys committed suicide. “That’s not included in this report,” a reviewer said. “Who knows where else it’s happened?”

Native American students were subjected to harsh or demeaning treatment at day schools. A former student who attended another day school recalled getting swatted on the hand with a ruler for speaking in his language, and of being told to shower after a weekend home.

“The message was that they wanted to rid us of whatever we came into contact with for the two days

that we weren’t at school,” he said, “They largely viewed any association with our community, with our culture, with our Tribe, with our clan, to be unwanted and out of favor.”

In addition, tribal lands were lost. Phoenix Indian School was established on lands on which the Akimel O’odham, Havasupai, Piipaash and others had lived since time immemorial. But when the school closed in 1990 after 99 years of operation, the land was not returned.

Instead, the federal government deemed the land surplus and traded much of it to a Florida developer in exchange for 108,000 acres of land in the Everglades. The developer built 4.7 million square feet of commercial space and established a $34.9 million educational trust fund for Native Americans in Arizona, but the land was gone.

AMID TRAGEDY, STORIES OF RESILIENCE

Stephanie McMorris (Hidatsa/Ho Chunk/Potawatomi) is a counselor at Sherman Indian High School in Riverside. She said the forced boarding school era is part of the history of the United States and must be discussed in schools. There was tragedy, but there are also stories of strength and resilience.

“My parents went to boarding schools,” McMorris said. “They have their own experiences; everyone’s had their own experience. And I know for some people, there was tragedy. But there were some lifesaving parts of it too. Some of that era was during the Great Depression and some parents sent their kids to boarding schools so they could eat.

“I’m not dismissing how horrible it was but there’s a whole spectrum of experiences. Yes, it was horrible what the federal government did. But we survived. We never lost our Nativeness or Indianness. We discovered different tribes and we built a community out of that. Some people had painful experiences. But I’ve met respected elders who said they learned things they were able to use later in adapting to this new world economy, and they developed lifelong friends.”

AN AMERICAN APOLOGY TO NATIVE NATIONS

Two hundred years after the first federal Indian boarding school was authorized and funded by the Indian Civilization Act Fund of March 3, 1819, President Joe Biden’s apology for the tragic effects of the federal government’s assimilation policies on American Indians and Alaska Natives is a welcome gesture.

The apology offered before a small crowd of tribal leaders and representatives on the Gila River Indian Reservation in Arizona on October 25 was welcomed by tribal nations across America.

A two-volume report, “Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report,” prepared under the watchful eye of Secretary of Interior Debra Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) and issued in 2022 and 2024, is the incentive for the apology.