NOTICIAS

he chronology o/d cornmunity is marl(^cd by pivotal events, henchmarl{s to which one can point and say zvith a reasonable amount ofceitainty, "It all changed he>-e, it nev er really ivas the same again." With the recent celebration ofthe millennium,ive all had the oppoitunity to passjudgment on what these watershed events may have been in the last one hundredyears, whether on aglobal, natiotial, orlocal level.

What ivould one point to as Santa Barbara's defining moments'’Perhaps it zvas the foiniding of the Old Wlission, the tra^isition to American nde or the climatic events ofthe 1860s zuhich irrevocably changed the basis of the local ecoziomy. Or was it the consLmetion ofStearns Whaif the anival ofthe raibvad, or thefounding ofthe University of Calijoniia, Santa Barbara:’ Whatever may appear on your "top ten”list,few lists indeedzvould not include the earthquake ofJune 29,2925.

So it is on this y^th annivasary of the earthquake thatzve take another look at what zvas arguably the saninal event in Santa Barbara of the 20th century. What were the seismologicalfin-ces which tiiggaed andfueled the earthquakel’ Why did some buildings collapse,luhile others were spared?Hozv did the citizais respond to the crisis at hand? Hozv did the earthquake quicken certain impulses,accelerate the development of certain ideas already present in the body politic?

Chr-LStine Palmer examines these questions and more in this issue o/Noticias. She looks in detail at hozv the earthquake permanently changed the urban landscape and transformed citizens' paveptiorrs about that landscape. The city's unified ar-chitectural styling has madefor it anintcniational rep utation and has thus been a k^y elanent in the city's economicgrozvth.

Front cover photogr-aph shozvs ivori{men posing at the Flotel Califorziian at 35 State Street in the aftermath of the earthquake- Back cover photograph shozvs the recording device at the Southern Counties Cjos Company zvhich marked the ear-thqualte’s passing. All photographs are from the collec tion of the Santa Barbara Historical Society.

THE AUTHOR;Christine Savage Palmer received herWlA.in Public Flistorical Studiesfrom VC,Santa BarFara in 1990. Her iniblications include the book, New Deal Adobe; The Civilian Conscrvacion Corps and the Rcconscrucdon of Mission La Purisima, 1934-1942. as well as arti clesfor the National Forest Service, the Nevada Historical Society, and the City ofAlbucpterque. She is pr-esently the City Historianfor the City ofSanta Barbara.

INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS; Noticias is a quarterly journal devoted to the study of the history of Santa Barbara County. Contributions of articles arc welcome. Those authors whose articles arc accepted for publication will receive ten gratis copies of the is sue in which their article appears. Further copies arc available to the contributor at cost. The authority in matters of style is tiic University ofChicago ManualofStyle, iqth edition. The Pub lications Committee reserves the right to return submitted manuscripts for required changes. Scaccmcnts and opinions expressed in articles are the sole responsibility of the author.

Michael Redmon. Editor

Judy Sutcliffe, Designer

Michael Redmon. Editor

Judy Sutcliffe, Designer

© 2000 The Santa Barbara Historical Society

136 E. Dc ia Guerra Street, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ● Telephone: 805/966-1601

Single copies $5.00 ISSN 0581-5916

rhe 1925 Santa Barbara EARTHQUAKE

A 75t/i Anniversary Commemoration

Christine Palmer

blications on St seventy-five er

This story, like most, is in the details. It is the quota tions from the eyewitnesses that bring it to life. Although researchers and writers have ojfered substantialpu the occurrence and consequences of the quake during the iasi years,no one has assembled the disparate technological and anecdotaldata into a single story. This publication draws on seismological analysis aft the quake,local memory,andfolklore,as well as research into the built envi ronment standing at the time ofthe quake and the considerable alteration of those structures afterward. Only a smallportion ofthe photographic record ofthe quake can beprinted here and readers are encouraged to visit the pho tograph collections ofthe QledhillLibrary at the Santa Barbara Historical Society LAuseum to view moreimages.

Even though Santa Barbara was already moving in the direction of a Mediterranean architectural style, the 1925 earthquake literally cleared the way.

The quake is responsible for die creation of officials seized the opportunity provided the distinctive appearance chat has made by the destruction of the earthquake the community a fashionable residential force a and tourist destination for the last to enstricter building code. They worked to require that new and remodeled sevenstructures conform to a historic style of architecture. This meant that Santa Barbaty-five years. The quake allowed Santa Barbara to recreate itself away from the look of an average Victorian coastal town into a red-tile roofed fantasy village. By damaging most of the community’s com mercial district, the earthquake proved to be a boon to local architecture, culture, and economics. Community activists and city ra could celebrate its heritage in Spanish Colonial Revival architectural style.

Geologically, the city’s commercial core and the bulk of its older residential structures lies within a fault-bounded de pression between the Mesa on the south-

(2-5.000.000

west and Mission Ridge on the northeast. Between the Mesa and Foothill faults at the bases of the uplifts are unconsolidated sediments including marine sand, silt, and clay from the Pliocene era years ago), and the Pleistocene era (12,000-2,000,000 years ago). The epicen ter of the 1925 earthquake was under the ocean off the coast of Carpinteria. The two jolts felt by Santa Barbara residents during the quake were the Mesa and Mis sion Ridge fault lines bumping from the shockwave produced at the epicenter.

Structurally, much of the city below Ortega Street is built on low drainage are as, called esteros during the community’s Hispanic decades, old stream channels, and marshes. Both Laguna and Salsipuedes streets, as well as Olive Street’s original name. Canal Street, derive their names from the large estero that formed seasonal ly from the beach to Anapamu Street each year.i The structures built on these former estero sites suffered from liquefaction, or instability of the underlying soils.

In 1925, fifty percent or more of the structures in the business district were built of brick or concrete with wooden interiors.

Two percent were adobe and wood, and less than one percent was reinforced con crete, In the residential areas, more than ninety percent of the structures were wood frame construction. The number of resi dences damaged was small, and those that were harmed suffered mostly plaster dam age. chimney loss, and foundation move ment. The average cost of damage to resi dences was only one hundred dollars.2

Before the Quake

The initial tremors came on the morn ing of Monday, June 29. 1925. beginning at 3:37 a.m. The night before, residents had gone to bed on an uncomfortably warm, humid, and still night. Accustomed to a cooling breeze from the ocean, many people later reported that they had tossed and turned in their sleep. The first pre dawn movement jiggled the stylus of a pressure gauge at the City Water Depart ment. The instrument recorded more small vibrations for the next three hours, but they were so slight chat night shift employees did not notice. Tlie sun’s first rays appeared on the horizon around 4:00 a.m. Early-rising farmers noted a strange agitation among both wild and domestic animals. The sun rose at 4:40 a.m.

At 6:00 a.m.. Dr. James Angle drove to his dental office in the San Marcos Building at the southwest corner of State and Anapamu streets. Tlic San Marcos was a steel-reinforced concrete masonry structure, which had replaced the old Vic-

T^any ofSanta Barbara's Victorian-era buildings suffered grave damage in the 1925 earthquake. The Fithian Building in the 600 block,ofState Street, popularly called the "Lower Cloch Building,”lost its tower and thirdfloor. The remodel, which scaled back on building size and utilized elements ofthe Spanish Colonial Revival style, were themes typical ofthe city’s architectural makeover.

torian-era Santa Barbara College building in 1914. Dr. Angle had come to his ortho dontist office early to work in his labora tory in Room 228 before leaving on a business crip to Los Angeles. In the same building, the maintenance engineer, Sigismundo Mostiero, and the janitor, Marcaria Vilomar. were conducting their earlymorning custodial duties.

Also at 6:00 a.m., at the Santa Barbara railroad depot, architect Julia Morgan was disembarking from the train from a south bound train. A workaholic, she had ridden all night from her San Francisco office to meet with the city’s most noted preserva tionist. Pearl Chase, to review design plans for the proposed Margaret Baylor Inn at 924 Anacapa Street(now the Lobero Building). Morgan’s other client at the time was William Randolph Hearse, with whom she was collaborating on designs for his "castle" at San Simeon. She stood at the curb along State Street beside the depot, suitcase and drawings in hand, waiting for the electric streetcar to take her uptown to meet with Chase.

Out at 1101 Luneta Plaza off Cliff Drive on the sparsely populated Mesa. City Manager Herbert J. Nunn was sit ting on the edge of his bed. An engineer by profession, he had constructed his hollow-clay-cile Spanish hacienda-style home at this bluff-edge sice the year before. He had arisen in the darkness to investigate an overpowering odor of petroleum. Nunn assumed the sea breeze was wafting the smell from the oil refinery at Summerland, but he noted chat the air was com pletely still and remained awake wonder ing about the cause. The Reverend Augustin Hobrecht, O.F.M., Father Su perior of the resident Franciscan friars in the Santa Barbara Mission monastery, had just rung the morning bell to call the padres to prayer.

The Quake Strikes

Ac 6;44 a.m., the first shockwave struck the community at a magnitude lat er estimated as 6.3 on the Richter Scale. Residents who were already awake when the shock struck heard an underground roar which they later variously compared to the chump of a distant explosion, the approach of an express train, or the rum ble of distant thunder. An unidentified ear ly-morning golfer at the La Cumbre Golf and Country Club in Hope Ranch was quoted about the roaring noise in the San ta Barbara Daily News on June 30, 1925.

1was held spellbound by a roar, the lik^ of which I have never heard,cannot intelligently explain, or ever expect to hear again, and was then picked up and shaken violently as if some monster had me by the shoulders with the sole intent ofshaking my head from my shoulders. It was all that Icould do to stay on myfeet. The hills seemed to rise andfalL.the rolling ofthe landscape being plainly visible on all sides of me. It was not the little jerks once in a whilefelt in many parts ofthe state, but a long drawn out roll that I believe would put many ofour beach roller coasters into a class below it. The roar which seemed to precede the actual shock by two or three seconds seemed to be coming from a long distance away and came with the rapidity ofa bullet.^

From the west, a short jolting shock was triggered by a slip of the Mesa Fault. The shock was followed a second later by a strong concussion from the Santa Ynez Fault to the north. Thirteen people were killed instantly or died subsequently, many fewer than would have died had the quake occurred a few hours later. Sixtyfive people were injured. Property damage and loss totaled $15 million. Several his toric structures vanished forever, although most homes survived the earthquake in relatively good shape. Nevertheless, near-

ly every chimney, tower, and steeple in the city crumbled apart. Commercial buildings did not endure as well as the resi dences. The rubble was so thick along the fourteen blocks of the State Street com mercial corridor that it blocked vehicular traffic. Subsequent reports disclosed that twenty-five vehicles parked along the curbs of State Street were crushed, and an other two hundred garaged autos in the business district were damaged.

While waiting for the streetcar to pick her up at the train depot, architect Julia Morgan was suddenly knocked down onto her hands and knees. More vibrations moved her suitcase and plans away from her. Morgan wrote later;

1 ivorked my way through the blinding dust to a place infront ofan auto salesroom... [where] I could see those great plate glass windows quiver before every wave and shock,.... After the dust cleared it was a per ceptible time before anybody came out of the buildings. When they appeared from lower State Street hotels and rooming houses,fa thers and mothers were carrying children of eight, ten and twelve years. No children were walking. It was very touching. Evidently, in the great catastrophe the parents reverted to protecting them as little children.'^

City Manager Herbert Nunn, out on the Mesa, was thrown backward on his bed by the initial shockwave. He described his experience as follows:

[C]rude oil came up through the beach sands within zoo yards of my home, and this phenomenon was repeated along the beach at several points south. About one mile south there was a flow of several barrels of oil, which came directly through the beach sands. At the moment ofthe shock I sitting on the edge ofthe bed,facing northeast,and was thrown upon my back- Preceding the shock there was a heavy rumbling sound similar to that ofthunder, which apparently camefrom directly underneath. There was a barely per ceptible interval between the rumbling sound and the shock. - (first] violent shock wasfollowed instantaneously by a rapid ver tical vibration.... I immediately ran from my bedroom to the front lawn [overlooking the ocean]... As Isteppedfrom thefront porch to a slightly sloping grass plot,I was thrown vi olently. ... My wife and the gardener, who were on the opposite side ofthe house at the time, came through [the house]. In stepping from a tiled porch to the grass ... both were thrown violently down. ... The rooj was vi brating vjith sufficient force to break the tiles.5

In general, private homes fared better than public and com mercial buildings. This was not always the case, however, as this home at Victoria and Santa Barbara streets attests.

The tremor struck the buildings of State Street s business area and spilled ma sonry, wooden beams, and splinters, as well as window glass, onto the pavement and parked cars. Nunn's job became grie vously complex because of this disaster, and four days after the quake he fell down the stairs inside city hall after "suffering an attack of neuritis."6 He resigned one year later an exhausted man as a political transition away from the city manager form of government forced him out of a job. He sold his Mesa home and moved away from Santa Barbara.

At the mission. Father Hobrecht was deafened as the first shock swayed the stone and adobe walls of the church off perpendicular. Mass was being conducted inside the mission church by Father Ra phael Yonder Haar when the quake struck. Another priest kept the worship ers inside the building as both bell towers lost their domes. The second floor of the monastery was reduced to a rubble heap. Hobrecht's description of the quake was as follows;

[l] was in the choir loft of the church

A daring Fr. Augustine Hobrecht, O.FM.,stands precariously in the ruined east bell tower ofthe > OldAdission. Restoration of the mission would be com pleted by Au gust igzy.

1/001/S ^Vnbq7AV2 31/3 ‘U0lS0}dx2 UV2UVAU27 -qns V iuoaJ?iuod 03 p3iu??s 7Vip dwini/3 v ipim

■■■■ivms 1U31/3 3pmu puv spvm i7qSiiu 3sai/3

7Vi{mAoJSuip}sqn^ ‘Smu2jv3p svm 2Siou 2qj^

m2UV UvSsq SuppOA 31/3 j2lAq‘pU0D2S V p2Ul2?S

33? 03 p27D2dx2 I 7Vlp OS '2DU3JOin, A27V3A§ Xpim

A27jv ^]UQ '7U21UOUI iCuV 2}qiU7UD SuipfjlTiq 31/3

Suinvq A27jv puv p3SV2D pvif qooqs pUODdS Slip

31/3 wi UIV7U2A 03 mxypq 2}do2d 3i/3 03 pypvD

(G3 j pip p2sv2D pvq ?qvnbipAV2 31/3 //13 t/amt/3

SmuuiSdg '^doa 03 uv§3q quv3 2q7"'U2qm l3jvs svm puv ipATXVp 31/3 3/3/ (.pV3A

pvif ‘A2qumu ui ^U2np 77ioqv 'uo}7V^3aS 'U02 2ljg ■SA2m07 31/3 IUOaJp2ddoAp 3P1/3 S2U07S ^uipvj uloaJ U71X 03 pvq 2m puv )p0A 07 uvS '?q UlvSv p7AV2 31/3 U2qm 'aIV U2do 31/3 p2ipV2A 2m pvtf ^pDAVog 'LvmqoAV IiaoaJ31/3 A2pu7i §m 'Pjpiq 31/3Jo 3310 ^VmATlO 2pviu uoos puv Aooj 7SaJ 31/3 wo lilOOU S0U3O 31/3 W1 2A2m 301 3131/3 p2A2aoDSip 2m ‘sn 2aoqv pa2]-A0ujf 31/3 uivS -2A 07 7dui277V Uivn. V A27jy -diu 2A0f?q U2jjvj pvq A2ij70Aq 31/3 ipiqm 03WI 3/01/ ^Avp v ui p2 'purrj puv SupfuisJi3Siiui 7pfj ((/U3ppns W3i/m.

TAVd 31/3 wo S7dlU271V pdAlTlbsAATloJ 7J UOOp 31/3

'P22DD71S 2m 2A0j2qJpsiui pUV AVJaJSuTwi VJO

((q p2vnuvf svm qoyqm Uoop 31/3 ^upAoJ m p2

'I/30 31/3 sn 1/31/n Suiqvj^ 'pJTi}} 3U07S finv?q 3i/3

om3j 7J0J uvSuo 31/3 71} 3q 03 p2U2ddv7j oqm sa?

Jo Lc07S pUOD?S 31/3 p3A?7U3 201'(SA2lj70uq p2§V

3q] ‘S33333S nLUGdGUy pUG 33G3g

S03JGp\J UH5 psdGqS-g 3qi jO SU0p33S 0/A3

■JDLpo LpG3 3SUtgSg psqsGius 3J3M §uip|ing

7V SODUVJA^ UV£ 31/3 !U.

?iqjSUods2A.loj svm S722U7S 77UlvdvUY puv27Viq r—

■sq7V2p 22uq7

3Lp Aq U3q] puG '3}3oqs gs3[aJ 3q3 Aq 3SJij rX'lv-tj' , s..fc r’—-V

^/V\ "^0}SS}lU 31/3 Jo U017D2S Lo7SVU0m 31/3

'ijDou Jo s?pd ^3(70 Lvon AYLo SupjDjd sdapsuno uoospU770j puv 7Snp IfDUlAOJ UV ?3S 70U p/nOD

31/3 l{§nOU7f7 U2(7W7 31/3 UlO^ P^^^Pj

07 /Cvoi ijDjijoi Su}7vq?p ?u?m 2m. Joou

Jodifj 2U0 Ԥu-ipp7iq dip xaojJ ddvos? mo ?ijviu

pursif I uoos puv Josn pv3i(v joS s^?ipouq pjo

'pV I 'iiS?UJ^p Jo (Co puv UVOUl V lUUj uio^

'^juvp m lunf uvSsquoJSu}(^ou§ puv pdDUvn.

'U03 psDJojupj A|jCTSf) '>^Doqs [pq3oo>j

3nq ●s33^'cnbq:J'B3 03 |[3a^ dn spucis 333jd

'33S pJ3A3S Ul 3jinq SBM SODJ'BJAJ U^5 3q3

iSUpSc pDJ333T?q SUOpODS 3SDq_L J3q33§ -o: p3p Ajpjn33nj3s lou di3m reip suou

03S niu^d^uy 3L|J_ 3]do3d DDiip joj |uicj pDAOjd ipiqM 2y\mh 3q3 Suunp JDipo ipC3

suopoos DLJ3 3J3qM J3UJ0D DL|J_ ●pD>jDBaD AjsnoiJDS SBM 3nq ‘§mpuB3S psuiBuisj uoi:

joined collapsed with a roar, filling the air with dust and blocking the intersection with bricks and rubble. William Mathers, who was sitting in his car beside the build ing, was crushed to death by the falling debris. Inside. Dr. Angle and the two cus todians were crapped. Mrs. Vilomar suf fered a broken leg and was rescued with a steam shovel seven hours later. Dr. Angle perished, though he sur vived CO within half an

hour of being found.

Maintenance Mosciero was also killed.

Outside engineer walls fel'

CO the ground to expose the sleep' ing rooms like cells in a honey comb.

The outside walls of the Hotel Californian at 35 State Street fell co the ground co expose the sleeping rooms like cells in a honeycomb. The hotel had been opened for business for only four days. The four-story structure was con structed with long brick sidewalls on a sice that was formerly tidal marshland. The hotel had a shallow foundation and the brick walls were not securely attached co the rest of the structure. Damage to this building resulted in some of the most spec tacular and widely circulated postearthquake photos. While no one was se riously injured in the Hotel Californian, some occupants found themselves unable CO leave their rooms by the conventional route. These guests tied bed sheets togeth er and lowered themselves co the street be low. The hotel was repaired and remained in use through 1999.

Ac the Southern Counties Gas Compa ny. located at 16 East Canon Perdido Street, Chief Engineer Henry F, Ketz had just relieved the employee on night shift. Ketz closed a master valve co shut off the city gas mains as the building began co shudder. He could cell from the severity of the shock chat many gas mains would

have been severed. Before he could reach the emergency valve, he had co stumble through a large room filled with swaying machinery and falling plaster. His action spared Santa Barbara the firestorm that destroyed so many lives and so much property in San Francisco after its earth quake in 1906. Ketz continued to work with a gas company crew to check the safety of individual lines at residences, and was subsequently awarded a gold medal from the American Gas Associa tion. Similarly, at the Edi son electric power plane located at Nopal and Quaraneina streets, night shift operator W.N. Engle was about to go off duty. His quick thinking enabled him to throw a switch to stop the electrical current from flowing through the fallen wires all over the city.

During the rest of the day. only one se rious fire occurred. An Enterprise Dairy truck burned at its parking place in front of Parma’s Grocery score at 721 State Street, cause undetermined.

Pearl Chase remembered chat the 1925

earthquake also caused a tsunami co rise above the (pre-breakwater) West Beach seawall and ascend State and Chapala nearly as far as the railroad streets tracks.” Although this event went unre corded in the aftermath of the quake, modern seismologists confirm that it is a likely consequence of a quake which had 8 ICS epicenter at sea.

Northeast of the city, at an elevation of 650 feet, Sheffield Dam was severely shak en. The dam was built of earth fill in 1917, measuring 25 feet high and 720 feet long. It held thirty million gallons of water borne by Mission Tunnel from Gibraltar Reset-

voir. Constructed on sandy soil, the quake caused fluid pressure in the soil underlying the reservoir to jump dramaticaliy-a pro cess known as liquefaction. The earth quake’s violent wrenching split the concrete toe wall and five-inch veneer of concrete facing down the middle of the earthen dam. The whole structure seemed to sink and then sprawled outwards releasing a wall of water down Sycamore Canyon.

The water flowed between Voluntario and Alisos streets, carrying trees, automo biles and three houses with it. leaving be hind a muddy, debris-strewn mess. About three hundred feet in the center of the dam simply floated away on the liquefied soil, traveling about one hundred feet down stream. Sheffield Dam has the distinction of being the only dam in the United States to fail during an earthquake. The water spread out to form a lake two feet deep on

lower Milpas Street until it gradually drained away Into the sea. Eyewitness Ed ward S. Spaulding stated that the rush of water to the sea from Sheffield Reservoir also took with it the water from Andree Clark Bird Refuge.9 It may be that this rush of water distracted everyone's atten tion from the tsunami that Pearl Chase re membered at West Beach, Unbelievably, no one was injured or drowned by the dam failure and rush of water.

Santa Barbara’s electric streetcar sys tem’s rails snapped on West Cabrillo Boulevard, where the street paving had The railroad right-of-way through Santa Barbara also suffered from the quake, but not as much as the round house. At the Southern Pacific Railroad roundhouse, which stood near the intersec tion of Punta Gorda Street and Cabrillo Boulevard, the foreman on duty was buckled.

The city lost a number ofits Mission I{evwaL~style structures including the Santa Barbara Telephone Company building at 34 West De la Querra Street. Today the city has only a handful ofbuilding this style including, most notably, the train depot at aop State Street and the Crocker Ejyw homes in the 2.000 blockofCjorden Street. s in

W.H. Kirkbride who described two row escapes" by his employees.

nar-

...[a] boiUmia}ier...was at the east end of the roundhouse [where]the bricks were fallingfrom the east wall[. H]i^e pieces ofma sonry were thrown a distance of twelve feet [.T]hat portion of the roof over him crashed downward and came to rest on a locomotive.

This man...was so badly frightened that he lost the use ofhis legs; after a severe attack,of nausea he managed to crawl out unassisted and uninjured.[A]stationary engineer... was on duty at the east end ofthe hoi4se, and was struck, on the head by a flying brick. At the same instance the steam pipe broke offat the boiler[. T]he roar ofthe escaping steam add ed to the tumult offalling walls and general confusion. Half dazed, he crawled back through the debris and extinguished the fire in the boiler.

Ac the opulent Mission Revival-style Arlington Hotel, the damage was severe. The hotel was completed in 1911 on the block bounded by State, Victoria, Chapa la and Sola streets (where the Arlington Theatre now stands). A sixty thousandgallon water tank had been concealed in side the top of one of the bell towers. Iron ically, the tank had been placed at the cop of the building for safety reasons. The first Arlington Hotel at the same site was a wooden Viccorian-era structure chat burned in 1909. With the water tank at the cop of the replacement hotel, there would always be water pressure in case of a fire. The water began oscillating enough from the shockwave to send the tank crashing down through the hotel’s deluxe suites in the tower below.

Mrs. Edith Forbes Perkins. 82, the wealthy widow of Charles R. Perkins.

Pemarkably,no one was hurt when Shejfield T.eseruoirgave way,flooding the lower Eastside oftoum. It is the only V.S.dam to collapse due to an earthquake-

was crushed in the Arlington Hotel wreck' in the hotel, where the guest register for age. Charles Perkins had been a former June 28 listed 125 patrons. Damage at the president of the Chicago, Burlington, and Arlington Hotel was attributed to poor Quincy Railroad and owner of the Alisal materials and construction, rather than Ranch near Solvang. At the start of the faulty engineering design. The tragedy did shaking, Mrs. Perkins called out in a panic to her maid who was in an adjoining room. Just as the maid managed to open the door between the rooms, the water

One ofthe oldest casualties ofthe earthquake was the V.S. lighthouse on the Mesa, built in i8^6. It was replaced by a Ught powered by acetylene and placed on a wooden tower and then, ultimate ly, by an automated light.

tank came crashing down, leav ing the maid looking out into empty space with a pile of de bris below her. Rescue workers subsequently found $200,000 worth of jewels and an ermine cape in the ruins of Mrs. Per kins’ room.

lead to a city ordinance forbidding the placement of water tanks on roofs. A grieving Captain Hancock gave this firstperson account:

It all happened in a minute. The crash of

In another cower suite just above Mrs. Perkins, oil and real estate tycoon Captain G. Allan Hancock and his twenty-yearold son, Bertram, were sleeping when the quake struck Santa Barbara. Bertram had recently graduated from college, was an accomplished amateur actor, and was planning to cake over his father's business interests. Like Mrs. Perkins and her maid, father and son were staying in adjoining rooms on the third floor. Captain Hancock was pulled out of the wreckage grievously injured after fall ing thirty feet. He eventually recovered, but Bertram had been killed instantly by falling timbers and steel beams and the walls the falling water tank. Mrs. Perkins and ofthe hotel made an indescribable inferno of Bertram Hancock were the only fatalities sound which dazed me. From the time I

kapedfivni bed until1was crawlingfrom un der the collapsed building seemed but a mo ment. Trapped nearby was a dining room maid. She and 1 crawkd to the lawn and a bellboy helped us to the street. My son prob ably never awakenedfrom his sleep. His sk^ll was fractured and his neck broken. It was best ifhe had to go that he go without suffer11 mg.

Santa Barbara’s Junior High School built of sandstone blocks at the northeast ern corner of West Anapamu and De La Vina streets, was totally destroyed. A mile further east, at Anapamu and Nopal streets, the newly completed Santa Barba ra High School stood intact, because of quality work manship. design, and mate rials.

The Wilson Elementary School located at Anapamu and Rancheria streets. Lin coln Elementary School lo cated on Cota Street be tween Anacapa and Santa Barbara streets, and McKin ley Elementary School lo cated on the northeast cor¬ ner of Castillo and Haley streets, were all destroyed by the earthquake. The Roose velt and Franklin elementary schools, both completed one year before, escaped dam age.

remained standing. As was demonstrated at the San Marcos Building, it was dan gerous when buildings constructed in two sections were not soundly united.

Throughout the lower State Street commercial core, multi-story buildings had been erected on filled ground, result ing in severe damage. The Neal Hotel at 217 State Street, the Virginia Hotel at 1117 West Haley Street, and Barbara Hotel at 524 State Street, each lost portions of their roofs and walls due to the unstable soil. The five-story Carrillo Hotel at Cha pala and Carrillo Streets, was the largest in the city in 1925. It suffered less damage because its foundation rested on clayboulder formations.

arbara

Santa B High School stood intact because of quality workmanship, design, anc materials.

The Fithian Block office building built in 1895 at the southwest corner of State and Ortega streets lost its Victorian-era clock tower and chimes in the earth quake. Damage was so se vere at this building that the upper two stories were eventually removed. The lower two floors remain to day after being damaged by fires in 1964 and 1965 and substantially remodeled as the Park Building.

At the southwest corner of State and Montecito streets, the 1907 Potter Thea tre collapsed from the proscenium arch to the rear of the fly gallery. A popular loca tion for vaudeville stars, the theatre had been constructed near the railroad depot and the Potter Hotel (which had been de stroyed in a 1921 fire) to cater to both Santa Barbara’s tourists and residents. Tlie front part of the building and the auditori um had been constructed separately and

The four-story St. Francis Hospital, lo cated on a hillside at East Micheltorena Street sustained heavy damage. Floor slabs, columns, and girders all showed se rious cracking with many of the terra cot ta filler walls thrown down. The Central Library at Anapamu and Anacapa streets, built in 1917 with the help of Carnegie Foundation funds, lost both its west and east walls. The library also suffered con siderable interior structural damage, which was not completely repaired until the mid-1960s.

Santa Barbara’s only "skyscraper," the

cighc-srory Granada Building, was builc of steel and reinforced concrete in 1924. It suffered diagonal stress cracks above the third iloor. The theater por tion escaped with only minor damage. Workers applied gunitc (also known as shotcrcce) to the sides of the structure to strengthen it alter the earthquake; this repair job altered the original de sign for window placement on the building.

On the coastal bluff edge of the Mesa, the 1856 lighthouse was dam aged beyond repair. TTie stone cower containing the Fresnel lens light fell and broke in half. The building was not reconstructed and the Coast Guard chose CO place an automated station in its place.

Many other historic structures were destroyed. Among them was the 1865 J Our Lady of Sorrows Church at the northeast corner of State and Figueroa streets, where the western tower pinna cles crashed onto the streetcar tracks along State Street. The brick facing of the church was shaken off to reveal the underlying adobe construction. This church was subsequently reconstructed at the northwest corner of Anacapa and Sola streets. Portions of the Pres byterian Church at the northeast cor ner of Anapamu and Anacapa streets and Trinity Episcopal Church at 1500 State Street were also damaged. Mor timer Cook’s Upper Clock building at State and Carrillo streets suffered se vere damage.

The Victorian-era county court house, jail and annex at 1100 Anacapa Street, originally designed by former Santa Barbara mayor Peter J. Barber, were so severely damaged that they were torn down. The jail held twenty prisoners at the time ol the quake, all

of whom escaped severe injury with elev en released on parole during the disaster re covery period. Completely rebuilt by 1929 at the same site, the County Courthouse

instantly thereafter by one from the north, along the Santa Ynez South Fault.

The Cicy Recovers

ABOVE and OPPOSITE:For weeks, even months, after the quake, life in the city moved out doors.Johnston's Cafeteria openedfor business next to the Lobero Theatre on Anacapa Street.

became the local government's contribu tion to the community's stock of post earthquake Spanish Colonial Revival style architecture. Since then, it has come to be regarded as one of the most beautiful gov ernment buildings in the western world, massive wheeled cannon which stood on the terrace of the Santa Barbara post office at State and Anapamu streets (now the Museum of Art), normally had its tailpiece pointing north. The jarring of the earthquake swung the tailpiece sixteen inches to the south. It left a scratched record in the concrete paving to show that it had swayed back and forth several times. From this and other evidence, seis mologists could prove there had been a se vere longitudinal shock originating in the southwest, along the Mesa Fault, followed

AThe first shock, estimated to have last ed only eighteen seconds, was followed by four aftershocks of six to eight seconds’du ration during the next twenty minutes. Continuing temblors, measuring into the hundreds, but with diminishing force, shook Santa Barbara for months afterward.

Edward Spaulding and his family lived in Mission Canyon where they did not feel safe living inside their home. For four days after the quake, while aftershocks contin ued to frighten the populace,Spaulding and his family lived on the lawn of his home. They cooked on an improvised stone fire place on their driveway and spent the nights on mattresses on the grass. He said the continued small quakes shook down plaster and other debris that had been loos ened at 6:44 a.m. on Monday.

While the quake was centered offshore on the Mesa Fault, it caused severe dam age as far away as Ventura. The U.S. For est Service fire lookout stationed on top of La Cumbre Peak reported a high intensity vibration; a 75-liter can half full of water was shaken empty by the initial shock. Damage elsewhere in Santa Barbara County was minimal. The Daily News re ported that Goleta lost every chimney ex cept one, and several frame farmhouses were jarred off their foundations. Observ ers reported that the air was fuE of dust immediately after the first shock. Gaviota observers saw waterspouts at sea, and a storekeeper noted that everything on his shelves was hurled to the floor in an east ward direction. Springs near Gaviota Pass increased their flow temporarily.i'3 In San ta Barbara. City Manager Herbert Nunn reached State Street in his car at 7:20 a.m. He saw that vehicular traffic could not move through the fallen debris along State Street and several other streets. He made a circuit of the business district, by way of Chapala and Anacapa streets, to check the

damage and mortalicy. He arrived ac city hall, completed the year before, to find the structure in good shape. The nearby Santa Barbara Daily T^ews building in De la Guerra Plaza, the Lobero Theatre on East Canon Perdido Street, and El Paseo’s Street in Spain, all recently completed, were relatively undamaged.

All city department heads quickly re ported for duty. Water Department man ager Vic Trace shut off the main water valve to prevent flooding from broken mains, and an emergency water crew was already functioning with local plumbers. By 9:00 a.m., City Engineer George Mor rison had a fleet of shovels, trucks, and cranes moving debris from the Arlington Hotel and the San Marcos Building, where human casualties were suspected and later confirmed.

A former Navy radio operator, Archie Banks, reported for emergency communi cations duty at an early hour that Monday morning. He had just opened a new busi ness, Banks Stationery, in the portion of the San Marcos Building which remained

Naval personnel were sent in to perform emer^enc^ policing duties. Here a patrol makes its presence felt infront ofthe First National Bank,901 State Street.

standing. Upon learning telegraph and tele phone communications were cut off. Ar chie sent an SOS message with his ham ra dio. He improvised a crude wireless transmitter by taking a spark coil and stor age battery from a rubble-wrecked Model T Ford, a telegraph key borrowed from the sagging Western Union telegraph build ing, and a few odds and ends of copper wire, tin foil, and rubber insulators.

Attaching a ground wire to a streetcar rail in front of Diehl’s Grocery at 823 State Street, and using a random length of wire stretched across the street as an an tenna, Archie began tapping out SOS sig nals. His receiver was a simple crystal set; his transmitter was not tunable to any specific wavelength, but it put out a signal so broad that within minutes Archie raised an operator aboard the freighter Peacockin

the Santa Barbara Channel. Explaining that the city's business district lay in ruins due to a major earthquake, Archie asked the Peacock's radio operator to relay his SOS to the Los Angeles area.

Apprised of the Santa Barbara disaster by the freighter’s radio, the outside world responded quickly. President Calvin Coolidge was at the bedside of his ailing father in Plymouth. Vermont, when he got the word. He immediately ordered the govern ment to render all possible aid to the city.

The American Red Cross set up emer gency tents in city parks, the courthouse lawn, and De la Guerra Plaza. Officials declared the county hall of records, county jail and courthouse unsafe to enter and saw that those buildings were roped off. Assistant professor of French at the University of Chicago, Robert V. Merrill,

was visiting Santa Barbara and described the disaster relief effort as follows;

Within an hour [after the first shock], there was a little green tent standing in the Plazci on De la Querra Street, with the Red Cross flag flying above it and an energetic group at worhinside and out. ...[T)/ie women and girls worked on in a blazing sun,slicing bologna sausage by the yard and bread until their wrists ached, while an increasing line of "customers" passed before the improvised counter and werefed. The[two]coofis were a short, ruddy boyfrom the Naval Reserve and an older youth whose worldly goods were safe under six feet of masonry in the Californian Hotel tr]hey pulled and heaved, sweated and were scorched to keep the tin cupsfull. As the sun grew high, some considerate person from the Yacht Club sent up a huge sail, which carpenters stretched on a hasty scaffold to screen the crew at the tables and pro tect the perishable food. ...

menced in his official report dated No vember 25. 1925. "Our people were cool and anxious to serve. Volunteers orga nized into working crews or into the po lice force, continued at their tasks day and night, almost without rest or food, for the first 48 hours.... This good order and splendid morale continued throughout the reconstruction period.”

There was no difficulty in finding workers,for the so cial opportunities implied in the occupation appealed to girls and young men who might not have responded so strenuously to the call of mere duty. So the week, went on, with heavy work, during the days and during the nights little beyond the dispatch of rations to the Marines and other guards on post. Restau rants began to openfor longer hours,and men who were solvent tended to patronize them as well asfind rooms oftheir oum. Thefirst-aid tent became unnecessary and was closed; the Canteen drew into narrower quarters,limited its operations to night hours and finally tinguished its stoves on Tuesday,July iq..1

Distraug citizens

htThe weather, however, did not remain reliable as a typical summer "June gloom” set in. This fact is reflected in the coats and hats worn by Santa Barbarans on post-earthquake photos. On the day of the quake, as well as for three days pre ceding it, Santa Barbara had sunny weath er with temperatures of 80-82 degrees and little air movement. On July 3. 4 and 5, the temperature dropped, the air grew more humid and the temperature highs only reached 70 degrees.15 Distraught citi zens living in the out-of-doors began wearing garments more appropriate for January than July.

living in the out-of-doors

oegan wearing garments more appropriate for ^ anuary than July

ex-

"There was an almost complete ab sence of panic.” City Manager Nunn com-

The city banks set up to conduct business on the lawn in front of the Lobero Theatre, within the Recreation Center patio, and on De la Guer ra Plaza. Later on Mon day morning, news came that Gibraltar Dam had escaped damage. At that time, the dam was holding back a lake 174 feet deep. Mission Tunnel had suf fered no misalignment or cave-ins. In fact, water utility workmen inside Mission Tunnel were unaware of the quake. As one side effect of the 1925 earthquake, the water percolating into the tunnel at the rate of 1,114,000 gallons per day was in creased by the shock to an additional 760,000 gallons daily.

Ciry water mains suffered seven breaks, but all reservoirs held with the ex ception of Sheffield. Although water pres sure dropped to zero within ten minutes, the city’s water crews were able to by pass damaged sections of the lines. By 9:30 a.m., they had restored pressure to 125 psi. This was comforting news for city fire fighters and hospital staffs.

The city’s sewage system was not damaged north of Carrillo Boulevard where surface soils are clay or gravel. Near the waterfront, where building sites had been tidal marshland only a few years before the quake, damage to sewers was severe. Most pavements withstood the shocks in good shape. Curbs suffered more from falling cornices and brick walls than from any movement of the earth,

The city’s two newspapers, the Daily Nevjs and Morning Press were on the street before noon with small single-sheet extras. Daily News owner-publisher Thomas M. Storke borrowed a gasoline engine from Ott’s Hardware Store across the street from his office to provide power for the small press that issued his earth quake extra of the news. In the midst of terror and confusion, it was prophetic that Storke’s hastily written editorial had the theme "Santa Barbara will rise again more beautiful than ever." Later issues of Santa Barbara's newspapers were printed on the presses of the Ventura Daily Star and Free Press.

Postmaster James B. Rickard moved his staff into a garage near the Southern Pacific Railroad depot and kept the mail moving until the post office could be in spected for structural damage. Mayor Charles M. Andera maintained a vigil at city hall, assisting in the direction of emer gency work. He and some members of city council set up cables to conduct busi ness on the courthouse lawn. They swore

in several citizens as special officers to as sist police in patrolling the community and keeping vehicles off State Street. Lt. Harvey L. K.iler summoned the Naval Mi litia for duty and by 8:30 a.m. on the day of the quake had men patrolling the streets to keep traffic from the disaster area and prevent looting from stores which had lost walls and/or windows.

Western Union telegraph office man ager Frederick A, Pugh was the first per son to send telegrams to another office by airplane, when he hired local aviator Earle Ovington to fly messages to Los Angeles. A former telegrapher named Eddie Abbott volunteered his services on the morning of the quake and was given a load of tele grams to take over to the Southern Pacific Railroad telegraph office, where a line to Ventura was being repaired. At Montecito and Anacapa streets, Abbott drove his Dodge touring car over a puddle he as sumed came from a ruptured water main. Upon his return, a policeman waved Ab bott away, explaining that the puddle was high-test gasoline. (Abbott later became the mayor of Santa Barbara.)

Elmer Awl delivered telegrams in Montecito. Scoutmaster Ira C. Kramer or ganized the Boy Scouts for telegram deliv ery duty. The manager of the El Mirasol Hotel(which stood at the modern location of Alice Keck Park Memorial Garden), Charles D. Wilson, donated one of his ho tel's garden cottages for the use of tele graph employees. He drove them to and from work during the period of the emer gency. One of the Mirasol cottage tele graph operators was Edwin Matthews, whose son. Eddie, became a famous major league baseball star of the 1950s and 1960s.

The U.S. Navy battleship Arkansas. summoned by Archie Banks' relayed ham radio SOS, arrived off Stearns Wharf af-

ter dark on June 29. Marines were sent ashore to cake over the emergency policing of the city, while the ship's generators sup plied electric power. Bakery goods and other services also came from the Arf^ansas. The battalion of Marines set up camp on the grass of the stadium at Santa Bar bara High School located at Anapamu and Quarancina streets. The Marines also ex tinguished a fire chat quickly grew around the State Normal School's Riviera Cam

pus at 2020 Lasuen Street, The fire had been fanned by Santa Ana winds a few days after the earthquake. Tlie Navy headquarters cent in Dc la Guerra Plaza was surrounded chat first night by citizens who spread blankets and mattresses on the lawn. Throughout the city, people suffer ing from fear of aftershocks slept in their back yards and continued to do so for sev eral weeks.

Tlie majority of Santa Barbara’s pri vate homes were constructed of wood

frames vvich wood siding and suffered only minor damagC'Crackcd wallpaper, loose piaster, or toppled chimneys. Wooden construction is much more flexi ble than masonry in an earthquake. With light and power lacking, the seven broken scw'cr lines, and in some eases no water supply, a few families suffered considera ble hardship. Railroad communication had been cut off by rock slides, but main roads were open to San Francisco and Los An geles within a matter of hours.

The aftershocks of the early Monday morning quake gradually diminished, but the tension of Santa Barbarans increased cumulatively with each small shake. On Friday. July 2. a particularly strong after shock rumbled through town. Edward Spaulding described the reaction:

We heard it coming and at once a dead si lence jell on the throng as the three orfour hundred people gathered (on the courthouse

Some businesses had problems bouncing back- Such was the case ivith Walter Cargill’s dry goods shop at536 State Street.

lawn] fivze in their tracks. As the tremor passed under us, 1 felt a curious, prickling sensation creep up my legs. Then the quake was gone, but the silence still held. Suddenly and with extraordinary effect, a woman screamed. At that scream, pandemonium broke loose on the lawn.i'^

Several days elapsed before Santa Bar bara could issue any definite casualty fig ures. Considering that the city had a pop ulation of over twenty-five thousand on that fateful June morning, the total of thir teen deaths was miraculously small. Only twenty-nine persons were treated in local hospitals for serious injuries. Offers of as sistance. in the form of money, labor, medicines, building materials, food and clothing, began pouring in from all parts of the nation and the world. Property damage totaled approximately fifteen mil lion dollars.

By the morning of July 5, geologists had recorded 264 aftershocks in Santa Bar bara, and they continued until September. 1925. In 1934. the California Institute of Technology began seismographic moni toring of the Santa Barbara Channel. The Richter Scale of measuring earthquake magnitudes was developed in 1935 as seismological analysis of the Santa Barbara area continued. Geologists determined that the highest intensities of the 1925 earth quake occurred in the southeastern portion of the city and along the base of the Mesa in the lower Westside. The exact epicen ter below the sea remains undetermined.

In 1932, local amateur weather fore caster Gin Chow published his First An nual Almanac. In it, he stated that he posted a notice in the Santa Barbara post office on December 23, 1920, predicting that an earthquake would strike the area on June 29, 1925. Gin Chow was a suc cessful Chinese immigrant who was

known in the area for making weather predictions which were occasionally more accurate than the government’s weather forecasts. Gin Chow enjoyed the patron age of Daily T^ews publisher Tom Storke who helped to promote the amateur fore casts as "uncanny." Despite Storke's be lief. and despite the numerous times the prediction story has been repeated during the past decades, there is no evidence that Gin Chow’s claim is anything but an af ter-the-fact assertion. Modern seismolo gists find it baffling that so many people believe the story of Gin Chow’s earth quake prcdiction.19

Architectural Consequences

One of Mayor Andera’s and city coun cil's first post-earthquake official actions was to establish a Board of Public Safety and Reconstruction on July 1. This board’s chief responsibility was to provide a fast and orderly program for reconstruction of damaged structures to safely house all city residents and activities. Prominent com munity preservationists Bernhard Hoff mann and Pearl Chase used this opportuni ty to suggest that the Spanish Colonial Revival architectural style (already suc cessfully used at the Lobero Theatre. El Paseo, and city hall) become officially sanctioned in the reconstruction efforts. They and others provided inspiring and ef fective leadership to citizen-sponsored, but officially authorized, rebuilding activities. The Board of Public Safety and Re construction commissioned an Engineers' Report which by July 3 had inspected the condition of all structures along the four teen block commercial core of State, Anacapa and Chapala streets. The Engineers’ Report also covered all hotels and public buildings for a total of 411 structures. A total of seventy-four were condemned for demolition, and another seventy-two re-

Perhaps nothing demonstrates the transition in Santa Barbara’s architecture better than the change ::ight in the county courthouse—from the domed Qreek.Revival edifice ofi8yz,shoum above with the i8go Hall of Records, to the Spanish Colonial Revival courthouse, completed in igz^, shoum below.

quired further inspection before condemna tion. Sixty-four were found "safe as is," and eighty-two were found to be safe but repairs would be needed. Another 102 could be opened for use after more exten sive repairs.20

The engineers recommended to the Board of Public Safety and Reconstruction that, "No major program of reconstruc tion should be undertaken without first be ing considered by a group which should consist of;(a) architects of Santa Barbara, (b) City Planning Commission,(c) a group of representatives businessmen and proper ty owners.” The Board immediately car ried out this recommendation by appoint ing an Architectural Advisory Committee through which these three citizen groups could act. Bernhard Hoffmann was named chair, T. Mitchell Hastings was the com mittee's architect, and attorney John M. Curran represented the City Planning Commission.21

The Architectural Advisory Commit tee used private funds to supplement and expedite the work of the City Building Department and the pioneering work of the newly created Architectural Board of Review (ABR). No construction permit was to be issued by the City Building De partment until a review and approval of the design was conducted by the ABR. For the next eight months, the board ex amined and altered hundreds of plans in volving $5 million in construction permits and achieving a grand start for Santa Bar bara’s Spanish Colonial Revival uniform architectural style. Meeting inside the Lugo adobe at 118 E. De la Guerra Street, the board’s review services were free. The post-earthquake ABR members were;

J.E. White, City Planning Commis sion; Chair Bernhard Hoffmann. Plans and Planting Committee; Secretary William

A. Edwards; Architect George Washing ton Smith; Architect Carleton A. Win slow; Architect John Frederic Murphy, Advisory Architect.22

Meanwhile two joint committees of engineers concluded that most of the damage was the result of poor materials and workmanship. Surprisingly, adequacy of design was not questioned. The materi als which received the greatest criticism were brick, tile and unreinforced concrete. Even reinforced concrete failed where workmanship was poor.23

Santa Barbara Becomes "New Spain"

Pearl Chase called the Community Drafting Room "the most original inspi ration” in creating the desirable changes on architectural plans referred to it by the ABR. Staffed with an architect and four designers, it prepared suggestions for the harmonious treatment of whole block fronts, as well as individual structures, while not exceeding the property owners’ budgets. Chase stated that this free ser vice transformed numerous structures of all types into;

public and private assets. In several blod{s of narrow stores an appearance of unified architecture’was achieved.... Simple store signs were carefully designed and placed so that each would have itsfull value witlrout destroying the appearance of its neighbors. This effect of block, harmony, so important to the reputation ofSanta Barba ra, has been lost wherever even one,or a mul tiplicity ofstrong colored painted fronts and competing signs have been introduced.^^

By February, 1930. the ABR had viewed and approved hundreds of sets of plans involving $5,500,000 in construc tion permits. Although city governance altered dramatically at this time, releasing beleaguered City Manager Herbert Nunn re-

from employment among ocher changes, the community had been influenced strongly by the leadership of Bernhard Hoffmann, Pearl Chase, and others who were leading them in the direction of "uni fied architecture." Post-World War II

Santa Barbarans remembered the positive changes effected in the town’s appearance by the ABR in 1925 and 1926, and chose to reinstate the board's approval process in 1949. By the early 1980s, noted architec tural historian David Gebhard described Santa Barbara as "refreshingly different from the typical American small city.” Gebhard went on to say that the 1925 earthquake was a "god-sent event...the op portunity of a lifetime."25

Gebhard’s enthusiasm was not only for the architectural benefits of the earth quake;

2 Ibid.. 5.

3 Web site for Seismic History, Geological Sciences Dcparcmenc. University of Cali fornia, Santa Barbara. 1997

4 Pearl Chase Correspondence, Julia Morgan letters, July 1925. University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Special Collections: Community Development and Conservation Collection, Box 23.

5 Bulletin of the Seismological Society of Ameri' ca,v.l5, 1925, 308-319.

6 Daily Nezvs{Santa. Barbara)3 July 1925.

7 Bulletin ofthe Seismological Society ofAmeri ca, V. 15, 1925, 251-254,

8 Robert Easton,"The Santa Barbara Earth quake.” TVotidcis 36(Spring 1990): 3-

9 Edward S. Spaulding,"The Earthquake-A Personal Experience,’’ Noticias5(Summer 1959): 8.

10 Bulletin of the Seismological Society ofAmeri ca. V, 17. 1927, 254.

11 A^eivs(Santa Barbara) 2 July 1925.

...{T]he events which followed were also viewed as opportunities to tighten up the zpning requirements ofthe city and to place more stringent limitation on building heights. ... By the end of the 1930s, the city had adopted an ordinance which limited commercial and in¬ dustrial buildings tofourstories(60feet high) and multiple residential units could not ceed three stories(q^feet highJ.26

12 Phil G. Olson and Arthur G. Sylvester, "The Santa Barbara Earthquake,” CaliforniaQeobgy, 1975, no. 6:9.

13 Walker A. Tompkins,"The Great Earth quake of ’25,” Santa Barbara Magazine, vol. 3, no. 4, 1977, 50-58.

14 Official Jfeport ofI{eliefActivities, the Earth quake Disaster at Santa Barbara California (The American Red Cross, Washington, DC.June 1926), 16.

ex-

The architectural ideal underlying San ta Barbara’s rebirth after the 1925 earth quake was best expressed by William Mooser, Jr. When his design for the county courthouse was completed in 1929, architect Mooser implied that the court house is more Spanish than anything in Spain. The city remains much admired to day because of its worst disaster seventyfive years ago.

NOTES

1 Arthur G. Sylvester and Stanley H. Mcndcs. Field Quick to the Earthquake His tory ofSanta Barbara.(82nd Annual Meet ing of the Seismological Society of AmeriMarch 1987) 3, ca.

15 Daily AJews(Santa Barbara) 1-5 July 1925.

16 Spaulding, 6.

17 Ibid., 13.

18 Olson and Sylvester. 13.

19 Web site for Seismic History, Geological Sciences Department, UCSB, 1997

20 Pearl Chase, "Bernhard HoffmannCommunity Builder,” Noticias5(Summer 1959): 5,

21 Ibid, 19..

22 Ibid., 23.

23 Sylvester and Mendcs, 1-6; Winsor Soule. "Lessons of the Santa Barbara Earth quake,” 'The American Architect. Vol. 128. No. 2482. Architectural and Building Press, Inc.. October 5. 1925. p. 244.

24 Chase, 7.

25 David Gcbhard, Santa Barbara - The Crea tion ofa New Spain in America(Santa Bar bara: University of California, 1982) 20,

26 Ibid., It.

<l:i3toosf 'ivot^orisftc VllV^lWgc yCim^ aqoc

af^qa'lAvou^oV oa saqsim

^i^oddns sno^3U3t> aq:i

:fO

3^nOTAT

svtot:io\j :lo ansst siqa uoiavoi'i5incl aq:i sq^iVAvoa

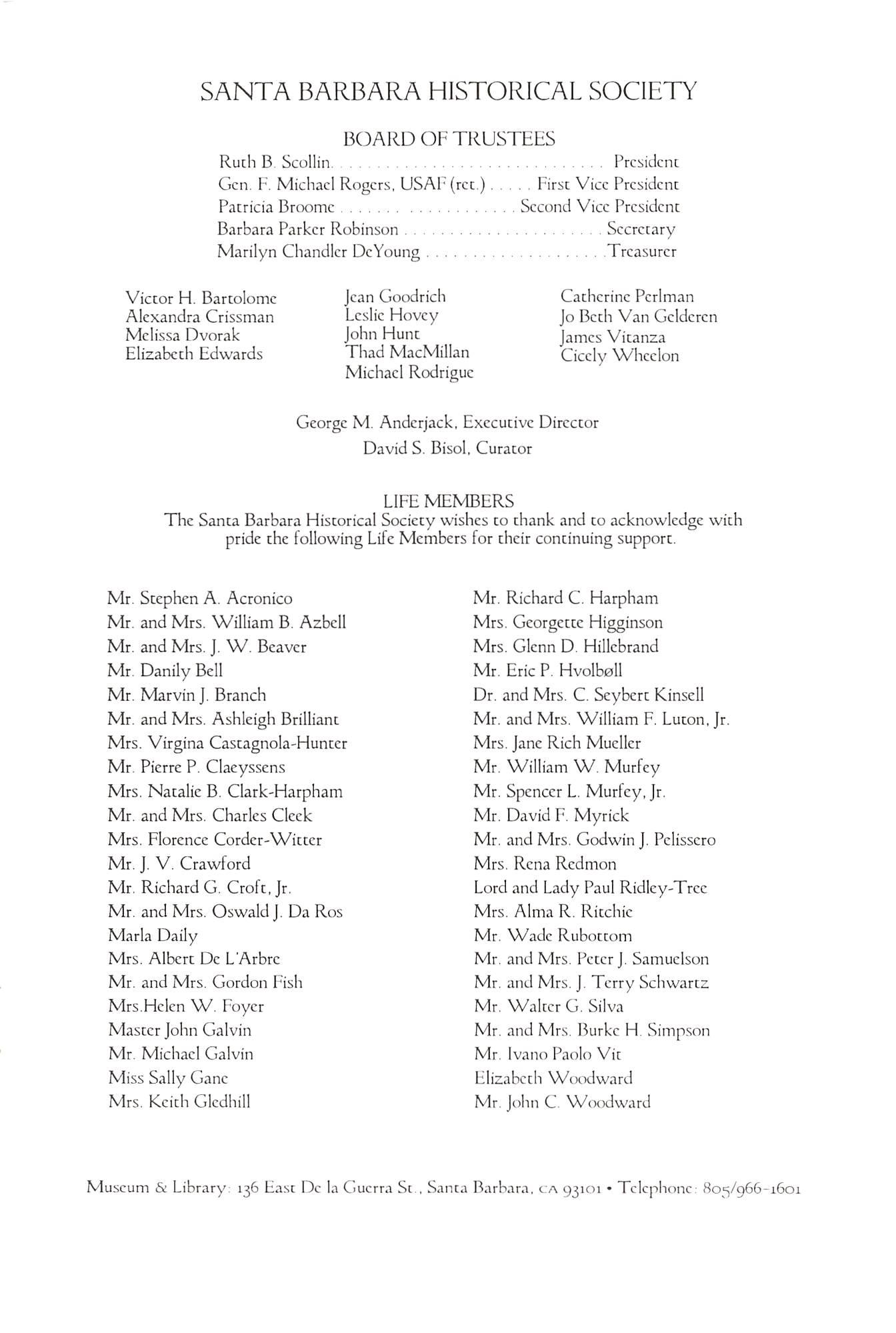

SANTA BARBARA HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Ruch B Scollin.

BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Gen, F. Michael Rogers, USAI'(rct)

Pacricia Brewme

Barbara Parker Robinson

Marilyn Chandler DeYoung

Victor H- Bartolomc

Alexandra Crissman

Melissa Dvorak

Elizabeth Edwards

Jean Goodrich

Leslie Hovey

John Hunt

Thad MacMillan

Michael Rodrigue

Prcsidcnc

First Vice President Second Vice President Secretary Treasurer

Catherine Perlman

Jo Beth Van Gcidcrcn

James Vitanza

Cicelv Wheelon

George M. Andcrjack, Executive Director

David S. Bisol, Curator

LIFE MEMBERS

Tlic Santa Barbara Historical Society wishes to thank and to acknowledge with pride the following Life Members for their continuing support.

Mr. Stephen A. Acronico

Mr, and Mrs. William B. Azbcll

Mr. and Mrs. J. W. Beaver

Mr. Danily Bell

Mr. Marvin J. Branch

Mr. and Mrs. Ashleigh Brilliant

Mrs. Virgina Castagnola-Huntcr

Mr. Pierre P. Claeyssens

Mrs. Natalie B. Clark-Harpham

Mr. and Mrs. Charles Clcek

Mrs. Florence Corder-Wittcr

Mr. J. V. Crawford

Mr. Richard G, Croft. Jr,

Mr. and Mrs. Oswald J. Da Ros

Marla Daily

Mrs. Albert De LArbre

Mr. and Mrs. Gordon F'ish

Mrs.Helen W.Foyer

Master John Galvin

Mr. Michael Galvin

Miss Sally Gane

Mrs. Keith Glcdhill

Mr. Richard C. Harpham

Mrs. Georgette Higginson

Mrs. Glenn D. Hillcbrand

Mr. Erie P. Hvolbol!

Dr. and Mrs. C. Seybert Kinsell

Mr. and Mrs. William F. Luton, Jr.

Mrs. Jane Rich Mueller

Mr, William W,Murfey

Mr. Spencer L. Murfey,Jr.

Mr. David F. Myrick

Mr. and Mrs. Godwin J. Pelisscro

Mrs. Rena Redmon

Lord and Lady Paul Ridley-Trec

Mrs. Alma R, Ritchie

Mr. Wade Rubottom

Mr. and Mrs. Peter J. Samuelson

Mr. and Mrs. J. Terry Schwartz

Mr. Walter G. Silva

Mr. and Mrs. Burke H. Simpson

Mr. Ivano Paolo Vir

Elizabeth Woodward

Mr. John C. Woodward Museum & Library: 136 Hast De la Guerra St , Santa Barbara, c:a 93101 ● Telephone- 80^/966-1601

Quarterly Magazine of the Santa Barbara Historical Society

P.O. Box 578

Santa Barbara. California 93102-0578 Address Service Requested

Pg21. Tile 1925 Earthquake: A 75th Anniversary Commemoration